Abstract

We present a rare case of cardiac malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH; undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma); to date, fewer than 100 cases of cardiac MFH have been reported. In this case, transthoracic echocardiography revealed cardiac tumors in the left atrium (LA) of a 53-year-old woman with a 3-month history of worsening dyspnea; the largest tumor was found to protrude through the mitral valve in diastole, causing stenosis. Three of the four tumors were resected during emergency surgery; however, the residual tumor extension into the left pulmonary vein could not be removed. Histological findings of the resected tumors, such as organized thrombus and myxomatous tissue changes, indicated that the tumors were benign. After 3 months, the patient underwent total resection for a small mass that developed on her right abdominal wall, which was revealed histologically to be MFH; additionally, the residual mass in the LA had enlarged progressively. After undergoing radiation therapy without further surgery, she died of cerebral bleeding 6 months after cardiac surgery. Postmortem examination revealed that the tumor in the LA was an MFH. Thus, cardiac MFH should be considered as a differential diagnosis for tumors on the posterior wall of the LA.

<Learning objective: Primary cardiac malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH), which is easily mistaken for atrial myxoma, is a rare type of cardiac sarcoma. MFH occurs most commonly on the posterior wall of the left atrium (LA), and total resection is currently the only effective therapy; however, the prognosis is poor. Therefore, a high level of suspicion is required to facilitate early diagnosis. Cardiac MFH should be considered as a differential diagnosis for tumors on the posterior wall of the LA.>

Keywords: Malignant fibrous histiocytoma, Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, Cardiac tumor

Introduction

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH; undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma) was initially described by O’Brien and Stout in 1964 [1] and is currently regarded as the most common type of soft-tissue sarcoma in adults. MFH arises commonly in the extremities and trunk, and the likelihood of local recurrence and metastasis is high. In contrast, primary cardiac MFH is rare. In 2001, Okamoto et al. reported 1 case of cardiac MFH and reviewed the 46 previously described cases [2]. Total tumor resection is the only effective therapy for this presentation of MFH, and the prognosis is poor. We present herein a case of acute heart failure consequent to cardiac MFH and discuss the features of this tumor.

Case report

A 53-year-old woman was hospitalized because of increasing dyspnea; she additionally reported a continuous dry cough of 3 months’ duration, with a history of cerebral hemorrhage 10 years earlier. On admission, her pulse rate was 100 regular beats/min and blood pressure was 129/91 mmHg. Abnormal chest auscultation findings and peripheral edema were not observed. Oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry was 94% in room air. Chest radiography revealed a ground glass-like shadow in both lower lung lobes. Electrocardiography indicated mild left atrial overload and mild QT elongation. Laboratory studies disclosed the following values: hemoglobin level, 13.6 g/dL; white blood cell count, 9600/mm3 with a left shift; C-reactive protein level, 2.39 mg/dL; and brain natriuretic peptide, 73 pg/mL (normal: <18 pg/mL). Her other common laboratory results indicated no particular abnormalities. She was hospitalized with a diagnosis of interstitial pneumonia, and antibiotic therapy was initiated.

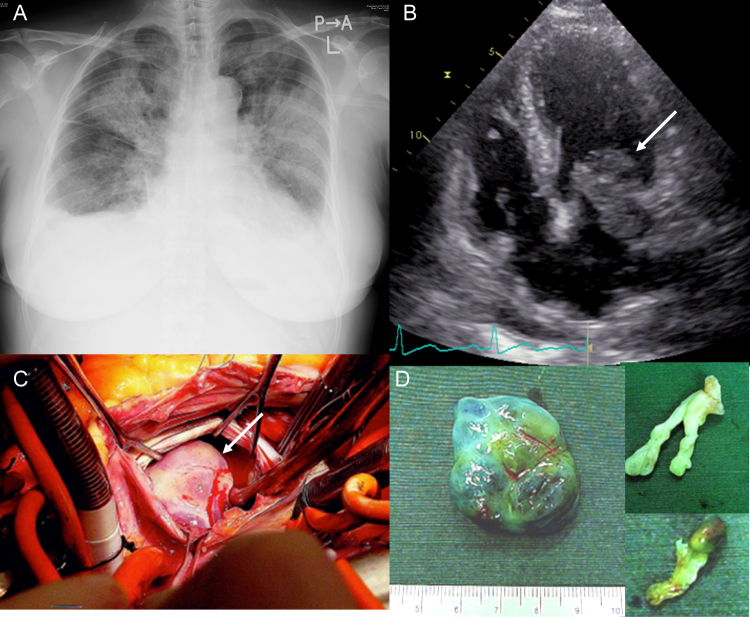

On the third hospital day, she experienced dyspnea while at rest. Chest radiography revealed pleural effusion and pulmonary edema (Fig. 1A). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed 2 cardiac tumors in the left atrium (LA): one tumor was a movable mass attached to the posterior wall that protruded through the mitral valve in diastole to cause mitral stenosis (Fig. 1B) and the other was strap-shaped and mobile within the LA. A provisional diagnosis of LA myxoma was made. The patient underwent emergency surgical resection (Fig. 1C), during which 4 tumors were observed and 3 were resected (Fig. 1D); however, one tumor had extended into the left pulmonary vein and could not be removed from the wall of the LA. Histological examination of the tumors revealed organized thrombus and myxomatous tissue with no malignant findings. Postoperative transesophageal echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a residual 20-mm × 30-mm tumor on the posterior wall of the LA that had obstructed the left pulmonary vein (Fig. 2A and B). Thus, these findings suggested a sarcoma.

Fig. 1.

(A) A chest radiograph showing pleural effusion and pulmonary edema. (B) A transthoracic echocardiogram showing a movable mass (28 mm × 26 mm) attached to the posterior wall (arrow). (C) The surgical view showing the movable mass during its excision from the wall of the left atrium (arrow). (D) Gross examination of the 3 resected tumors.

Fig. 2.

(A) A cardiac magnetic resonance imaging scan showing a residual mass on the wall of the left atrium (LA) (arrow). (B) A transesophageal echocardiogram also showing the mass in the LA (arrow). (C) Gross cut surface of the subcutaneous abdominal tumor. (D) A photomicrograph of the abdominal tumor (hematoxylin–eosin staining), showing the sarcomatous pattern of immature spindle cells. (E) An 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan showing the mass in the LA (arrow), but no additional metastases are observed.

The patient noted a small mass on her right abdominal wall at 3 months post-surgery; the mass rapidly increased to 6 cm × 7 cm in size within a 2-month period. This tumor was totally resected (Fig. 2C). Histological evaluation of the abdominal wall tumor revealed moderate cellular proliferation of oval- to spindle-shaped cells with highly nuclear atypia and intermittent mitosis (Fig. 2D). These cells were immunohistochemically positive for vimentin and negative for epithelial membrane antigen, cytokeratin (CAM5.2), α-smooth muscle actin, S-100, and CD34. The MIB-1 cell proliferation labeling index was 45%. The tumor diagnosis was confirmed as an MFH. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography detected the mass in the LA but did not find evidence of metastasis (Fig. 2E).

Gradually, the residual mass in the LA increased in size (Fig. 3A), and the unfixed portion extended into the mitral annulus (Fig. 3B). The patient complained of dizziness; cranial MRI revealed 3 new small infarctions, and we initiated warfarin therapy. We consulted with cancer specialists at 2 hospitals and both judged chemotherapy to not be indicated. Despite our recommendation for additional cardiac surgery, the patient selected radiation therapy. After receiving a total radiation therapy dose of 20 Gy, she was admitted to our hospital with cerebral bleeding and a prothrombin-international normalized ratio and a D-dimer value of 1.68 and 0.9 μg/mL (normal 0.0–1.0 μg/mL), respectively. She died of cerebral bleeding 7 days later at 6 months after the cardiac operation. Postmortem examination revealed deep invasion of the recurrent tumor into the left pulmonary vein (Fig. 3C). The pathological diagnosis of the cardiac tumor was MFH, the same as the abdominal tumor (Fig. 3D). One-third of the cardiac tumor had become necrotic, and the MIB-1 labeling index was 3%. We observed a micrometastasis of the right adrenal gland as well as infarctions in the spleen and right kidney. A brain examination was not permitted by patient's next-of-kin.

Fig. 3.

(A) A contrast non-gated computerized tomography scan of the chest showing a mass of increasing size in the left atrium (arrow). (B) A transthoracic echocardiogram showing a movable mass that had extended into the mitral annulus (arrow). (C) A cardiac tumor at autopsy (arrow) with invasion into the pulmonary vein (*). (D) A photomicrograph of the cardiac tumor (hematoxylin–eosin), demonstrating malignant fibrous histiocytoma.

Discussion

Primary cardiac tumors are rare, with a reported incidence of only 0.02% as determined by autopsy [3]. The majority of these tumors are benign myxomas, although a quarter of cases are malignant, most of which are sarcomas. Angiosarcoma is the most common type of cardiac sarcoma [4]. Although MFH is considered the most common type of soft-tissue sarcoma in adults, primary cardiac MFH is rare. Shah et al. reported the first case of cardiac MFH in 1978 [5]. Subsequently, Okamoto et al. reported a case of MFH that arose from the LA and reviewed an additional 46 previously reported cases [2]. An analysis of those 47 cases revealed that 29 patients (62%) were women and 18 were men (38%), with a mean overall age of 47.1 years. Cardiac MFH was found to occur most frequently in the LA and to usually attach to the posterior wall. The organs most often affected by metastasis include the brain, lung, bone, and adrenal glands.

The clinical characteristics of the present patient were similar to those in previous reports with respect to age, sex, tumor location, and metastasis. Because our first priority was emergency surgery, we were unable to perform a sufficient preoperative examination and failed to completely resect the tumor, leading to a local recurrence and remote metastasis. The rapid growth of the subcutaneous metastatic tumor in this case is noteworthy. As the subcutaneous tissue was originally a breakthrough area for the MFH, the tumor environment might have facilitated this growth. Furthermore, most tissues removed during the cardiac operation were organized clots, indicating that MFH might readily clot and embolize. As we confirmed brain infarction by MRI and infarction of the right kidney and the spleen by autopsy, the existence of cerebral embolism is possible. Although a brain examination was not permitted by the patient's next-of-kin, cerebral bleeding might have been partly related to MFH.

Multimodal therapy (e.g. surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy) is the standard treatment protocol for treatment of MFH in the extremities and trunk [6]. In contrast, the only currently effective therapy for cardiac MFH is total resection [7], [8]. However, a recent article reported an association between multimodality therapy for the treatment of primary cardiac sarcoma and improved survival [9]. Although multimodality therapy for cardiac MFH remains controversial [10], we provided radiation therapy at a total dose of 20 Gy to our patient after receiving informed consent. However, the effectiveness of this therapy was unclear. Irradiation might have exerted some effect on the tumor, as moderate necrosis and a decreased MIB-1 index were observed during the autopsy.

We experienced a rare case of cardiac MFH on the posterior wall of the LA, the most common presenting location. Total tumor resection remains the only effective treatment for such cases.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.O’Brien J.E., Stout A.P. Malignant fibrous xanthomas. Cancer. 1964;17:1445–1455. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196411)17:11<1445::aid-cncr2820171112>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okamoto K., Kato S., Katsuki S., Wada Y., Toyozumi Y., Morimatsu M., Aoyagi S., Imaizumi T. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the heart: case report and review of 46 cases in the literature. Intern Med. 2001;40:1222–1226. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.40.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynen K. Frequency of primary tumors of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:107. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simpson L., Kumar S.K., Okuno S.H., Schaff H.V., Porrata L.F., Buckner J.C., Moynihan T.J. Malignant primary cardiac tumors: review of a single institution experience. Cancer. 2008;112:2440–2446. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah A.A., Churg A., Sbarbaro J.A., Sheppard J.M., Lamberti J. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the heart presenting as an atrial myxoma. Cancer. 1978;42:2466–2471. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197811)42:5<2466::aid-cncr2820420549>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimer R., Judson I., Peake D., Seddon B. Guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Sarcoma. 2010;2010:506182. doi: 10.1155/2010/506182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toda R., Yotsumoto G., Masuda R., Umekita Y. Surgical treatment of malignant fibrous histiocytoma in the left atrium and pulmonary veins: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32:270–273. doi: 10.1007/s005950200034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoue H., Iguro Y., Matsumoto H., Ueno M., Higashi A., Sakata R. Right hemi-reconstruction of the left atrium using two equine pericardial patches for recurrent malignant fibrous histiocytoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 2009;39:710–712. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-3920-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Randhawa J.S., Budd G.T., Randhawa M., Ahluwalia M., Jia X., Daw H., Spiro T., Haddad A. Primary cardiac sarcoma: 25-year Cleveland Clinic experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014 doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000106. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llombart-Cussac A., Pivot X., Contesso G., Rhor-Alvarado A., Delord J.P., Spielmann M., Türsz T., Le Cesne A. Adjuvant chemotherapy for primary cardiac sarcomas: the IGR experience. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:1624–1628. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]