One common means to regulate protein activity is through phosphorylation. Protein phosphatases exist to reverse this process, returning the protein to the unphosphorylated form. The vast majority of protein phosphatases that have been identified target phosphoserine, phosphotheronine, and phosphotyrosine. A widely conserved phosphohistidine phosphatase was identified in Escherichia coli 20 years ago but remains relatively understudied. The present work shows that this phosphatase modulates the nitrogen-related phosphotransferase system, a pathway that is regulated by nitrogen and carbon metabolism and affects diverse aspects of bacterial physiology. Until now, there was no known mechanism for removing phosphoryl groups from this pathway.

KEYWORDS: CvrA, histidine phosphatase, histidine phosphorylation, PtsN, YcgO

ABSTRACT

SixA, a well-conserved protein found in proteobacteria, actinobacteria, and cyanobacteria, is the only reported example of a bacterial phosphohistidine phosphatase. A single protein target of SixA has been reported to date: the Escherichia coli histidine kinase ArcB. The present work analyzes an ArcB-independent growth defect of a sixA deletion in E. coli. A screen for suppressors, analysis of various mutants, and phosphorylation assays indicate that SixA modulates phosphorylation of the nitrogen-related phosphotransferase system (PTSNtr). The PTSNtr is a widely conserved bacterial pathway that regulates diverse metabolic processes through the phosphorylation states of its protein components, EINtr, NPr, and EIIANtr, which receive phosphoryl groups on histidine residues. However, a mechanism for dephosphorylating this system has not been reported. The results presented here suggest a model in which SixA removes phosphoryl groups from the PTSNtr by acting on NPr. This work uncovers a new role for the phosphohistidine phosphatase SixA and, through factors that affect SixA expression or activity, may point to additional inputs that regulate the PTSNtr.

INTRODUCTION

Phosphorylation is a common mechanism for modulating protein function. Much of its utility depends on the reversibility of the process, which is often mediated by protein phosphatases. Phosphorylation of histidine and aspartate residues is frequently encountered in bacterial regulatory systems, as well as in plants and some unicellular eukaryotes, and there is a growing appreciation for the importance of histidine phosphorylation in animal cells. However, the vast majority of phosphatases reported to date dephosphorylate serine, threonine, or tyrosine.

Escherichia coli SixA (signal inhibitory factor X) was one of the first phosphohistidine phosphatases to be discovered and, together with the eukaryotic PGAM5 and PHPT1 (1, 2), remains one of the best characterized. Amino acid sequence features and the crystal structure of SixA show that it is a member of the histidine phosphatase superfamily (3). The name for this superfamily is derived from the conserved histidine residue that is essential for catalysis and does not reflect the substrate specificity of the superfamily’s members (4). In fact, the substrate preferences for this family of phosphatases are diverse, ranging from small phosphorylated metabolites to large phosphoproteins containing phosphorylated tyrosine, serine, threonine, or histidine residues. As the smallest member to have been crystalized, SixA’s structure is representative of the minimal core fold of the superfamily’s catalytic domain.

As of this writing, all E. coli isolates with fully sequenced genomes contain sixA, making it a member of the E. coli core genome. In addition, homologs of sixA are widespread among proteobacteria, actinobacteria, and cyanobacteria (5). Thus, SixA likely plays an important role in the physiology of these organisms. Previous work suggested that E. coli SixA dephosphorylates the histidine-containing phosphotransfer (HPt) domain of ArcB (6, 7), a histidine kinase that, together with its partner response regulator ArcA, regulates the transition to anaerobiosis. Since those initial studies, however, no additional research has been published exploring the function of SixA.

Here, we reexamine the role of SixA in E. coli. We do not observe an effect of SixA on ArcB/ArcA-regulated transcription, and we find that SixA-null strains have a growth defect that is independent of ArcB. Suppressor screens and analysis of various mutants suggest that the growth defect is due to misregulation of the nitrogen-related phosphotransferase system (PTSNtr). We further show that the phosphorylation state of EIIANtr, one of the protein components of the PTSNtr, is affected by SixA, and we propose a model in which SixA dephosphorylates the PTSNtr protein NPr.

RESULTS

The absence of SixA causes a growth defect in minimal medium.

We noticed that a sixA deletion in Escherichia coli MG1655 grows poorly in glycerol minimal medium. In aerobic cultures at 37°C, the wild-type and ΔsixA strains reached similar optical densities (OD) at stationary phase, but the ΔsixA strain grew more slowly, with an exponential-phase-doubling time twice that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 1A). In contrast, when grown in LB Miller medium, the two strains showed no difference in growth (Fig. 1B).

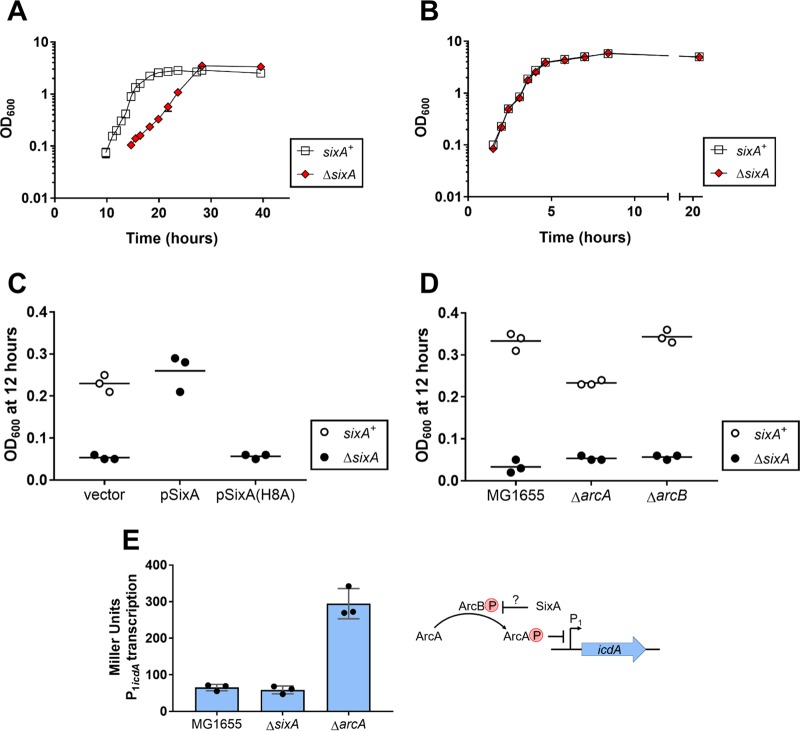

FIG 1.

Cells lacking SixA have a growth defect that is independent of ArcB/ArcA. (A and B) Growth curves were measured for the wild-type (MG1655) and ΔsixA (JES13) strains in (A) glycerol minimal medium and (B) LB Miller medium. Optical density at 600 nM (OD600) was monitored for two independent cultures of each strain. Symbols represent the average OD600; bars indicate ranges and are not visible where smaller than the symbol. (C) Cultures of the wild-type (MG1655) and ΔsixA (JES13) strains, transformed with empty vector pTrc99a, SixA-expressing plasmid pSixA, or SixA(H8A)-expressing plasmid pSixA(H8A) were grown in glycerol minimal medium with ampicillin for 12 h. Symbols represent the OD600 for individual cultures, and the horizontal black lines indicate the average OD600 from three biological replicates. (D) Strains were grown in glycerol minimal medium for 12 h. Symbols are as described for panel C. Strains are MG1655, JES13, JES47, JES48, JES49, and JES50. (E) β-Galactosidase activity was measured for strains containing a P1icdA-lacZ reporter following anaerobic growth in minimal medium with 40 mM KNO3. Symbols represent the activity (Miller units) measured for individual cultures, error bars report standard deviations, and the blue bars indicate the average levels of activity from the three biological replicates. Strains are JES252, JES253, and JES254. As shown in the illustration to the right of the graph, SixA was previously proposed to dephosphorylate ArcB.

To facilitate growth comparisons between strains, we used an endpoint assay in which OD was measured after 12 h, a time point that gave a large difference in OD between the wild-type and ΔsixA strains (Fig. 1A). With this assay, we verified that reintroducing the sixA gene on a plasmid restores wild-type growth (Fig. 1C). Moreover, a plasmid expressing a catalytically inactive SixA mutant, SixA(H8A) (4, 6), failed to complement the sixA deletion (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the growth defect is due to the absence of SixA and is likely due to the absence of SixA phosphatase activity.

We also found that the ΔsixA strain grows more slowly than the wild-type strain in minimal medium with acetate, maltose, or glucose as a carbon source. These observations for the ΔsixA mutant are consistent with the results of a chemical genomics screen that followed growth of E. coli mutants under various conditions (8). Data from that study also indicate that procaine has a more pronounced inhibitory effect on the ΔsixA mutant than on the wild-type strain, a result that we confirmed and also took advantage of for some genetic screens described below (see Materials and Methods).

The ΔsixA mutant growth defect is independent of ArcB and ArcA.

Since SixA was previously reported to be a phosphohistidine phosphatase for the histidine kinase ArcB (6, 7), we tested whether the growth defect of a ΔsixA strain depends on the ArcB/ArcA two-component system. To our surprise, deletion of sixA produced a growth defect in strains lacking either arcA or arcB (Fig. 1D), indicating that the slow growth does not depend on ArcB/ArcA activity.

To our knowledge, there is only one published report supporting a role for SixA as an ArcB phosphatase in vivo (7). We therefore wanted to verify that the absence of SixA affects ArcA-dependent expression under anaerobic respiratory conditions, as previously reported (7). We tested the effect of a sixA deletion on transcription from the icdA P1 promoter, which is repressed by phosphorylated ArcA and is not known to be regulated by other transcription factors (9) (Fig. 1E). For anaerobic growth with nitrate as an electron acceptor, deletion of sixA had no effect on transcription of a P1icdA-lacZ reporter (Fig. 1E). Importantly, β-galactosidase levels for anaerobic growth in the absence of nitrate were 2-fold lower than the corresponding levels with nitrate present (30 ± 5 Miller units and 60 ± 7 Miller units, respectively), indicating that the reporter is not fully repressed and is sensitive to changes in ArcA phosphorylation under conditions of nitrate respiration. Thus, for at least our strains and assay conditions, we have no evidence that SixA affects ArcB/ArcA signaling in vivo.

Suppressors of the ΔsixA growth defect indicate a connection between SixA and the PTSNtr.

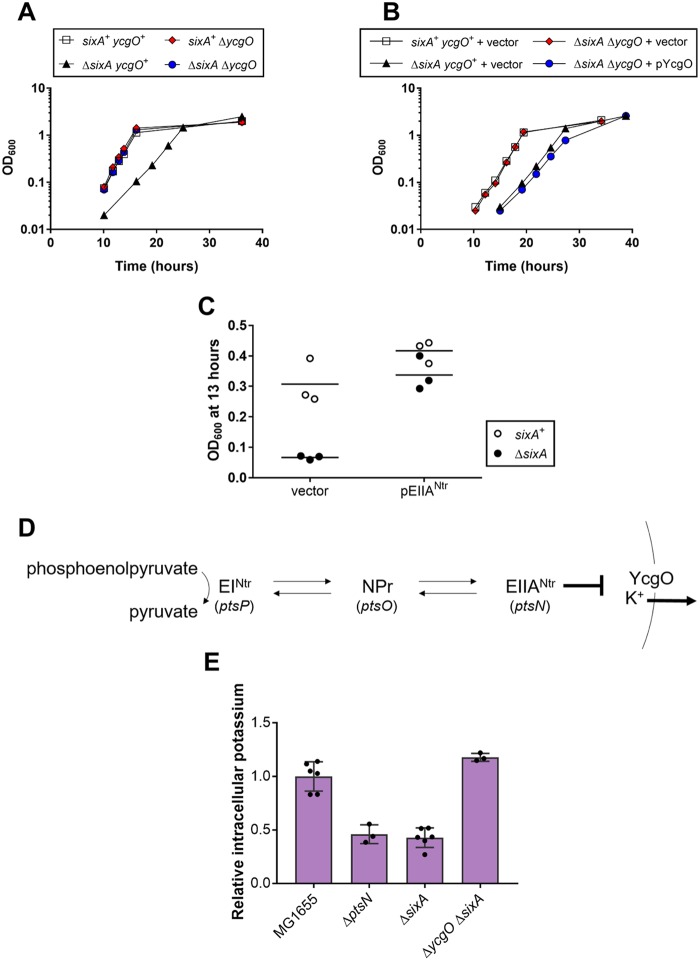

To identify genes that interact with sixA, we looked for mutants that suppress the slow-growth phenotype of a ΔsixA strain. From a pool of random transposon mutants, we identified insertions in ycgO, which encodes a protein sharing homology with cation/proton antiporters. We verified that a clean deletion of ycgO in the ΔsixA strain suppresses the slow-growth phenotype (Fig. 2A) and also that reintroduction of ycgO on a plasmid in the ΔycgO ΔsixA strain restores a growth defect (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

Suppressors of the ΔsixA growth defect. (A) Growth curves were measured for strains in glycerol minimal medium. Optical density at 600 nM (OD600) was measured for two independent cultures of each strain. Symbols represent the average OD600; bars indicate ranges and are not visible where smaller than the symbol. Samples for this growth curve were collected at the same time as the samples for the growth curve in Fig. 3B, so the data for the wild-type and ΔsixA strains are identical between figures. Strains are MG1655, JES13, JES30, and JES31. (B) Growth curves were measured for strains transformed with empty vector pMG91 or YcgO-expressing plasmid pYcgO in glycerol minimal medium with chloramphenicol. Symbols are as described for panel A. Strains are MG1655, JES13, and JES31. (C) Cultures of the wild-type (MG1655) and ΔsixA (JES13) strains, transformed with empty vector pTrc99a or ptsN-3×FLAG-expressing plasmid pEIIANtr, were grown in glycerol minimal medium with ampicillin for 13 h. Symbols represent the OD600 for individual cultures, and the horizontal black lines indicate the average OD600 from three biological replicates. (D) EIIANtr is part of the nitrogen-related phosphotransferase system (PTSNtr). Phosphoryl groups entering the system originate from phosphoenolpyruvate and are passed by successive phosphotransfers between the three PTSNtr proteins. According to a previously proposed model (13), unphosphorylated EIIANtr inhibits YcgO, decreasing potassium efflux. (E) Exponential-phase cultures, grown in glycerol minimal medium, were assayed for potassium by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Symbols represent the cellular potassium content for individual cultures, error bars report standard deviations, and the purple bars indicate the average cellular potassium content from all biological replicates. Strains are MG1655, JES208, JES13, and JES31. The average cellular potassium content for the wild-type strain is 243 nmol K+/OD600.

We also screened a plasmid library of E. coli genomic DNA to search for multicopy suppressors. As expected, the screen yielded plasmids containing sixA. In addition, we isolated three distinct plasmids that had only one intact gene in common: ptsN. Using a plasmid containing only the ptsN gene (modified to encode a 3×FLAG-tagged protein), we confirmed that ptsN overexpression suppresses the ΔsixA growth defect (Fig. 2C). The gene ptsN encodes EIIANtr, a protein of the nitrogen-related phosphotransferase system (PTSNtr) (reviewed in reference 10). The PTSNtr is composed of three proteins, EINtr, NPr, and EIIANtr, and it is regulated by a series of successive phosphoryl group transfers onto histidine residues: phosphoenolpyruvate to EINtr, EINtr-P to NPr, and NPr-P to EIIANtr (Fig. 2D). Several studies have found that inactivation of ptsN slows growth in minimal glucose medium (11, 12), and it was reported that deletion of ycgO suppresses this growth defect (13). Taken together, these observations suggest that the ΔptsN and ΔsixA growth defects may be due to the same mechanism.

ΔsixA cells have lower intracellular potassium levels than wild-type cells.

It was previously observed that cellular potassium content is lower in a ΔptsN strain and is restored by deleting ycgO (13) (Fig. 2D). We therefore reasoned that the ΔsixA mutation might have a similar effect on the cell. We measured cellular potassium levels of wild-type and mutant strains by ICP-MS (13). The potassium levels of ΔsixA and ΔptsN strains were 2-fold lower than the levels of the wild-type strain (Fig. 2E), and deletion of ycgO restored the potassium content of the ΔsixA strain to a level comparable to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 2E). These observations suggest that the absence of SixA, similarly to the absence of EIIANtr, may cause aberrant YcgO activity and misregulation of cellular potassium content.

Changes in SixA phosphatase activity alter EIIANtr phosphorylation levels.

The results described above suggest a model in which the SixA phosphatase modulates phosphorylation of the PTSNtr. To test this, we assayed the relative amounts of EIIANtr phosphorylation with native gel electrophoresis, which has previously been shown to resolve the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of the protein (11, 14). To detect EIIANtr and EIIANtr-P by Western blotting, we used strains that produce 3×FLAG-tagged EIIANtr from the native ptsN locus (15).

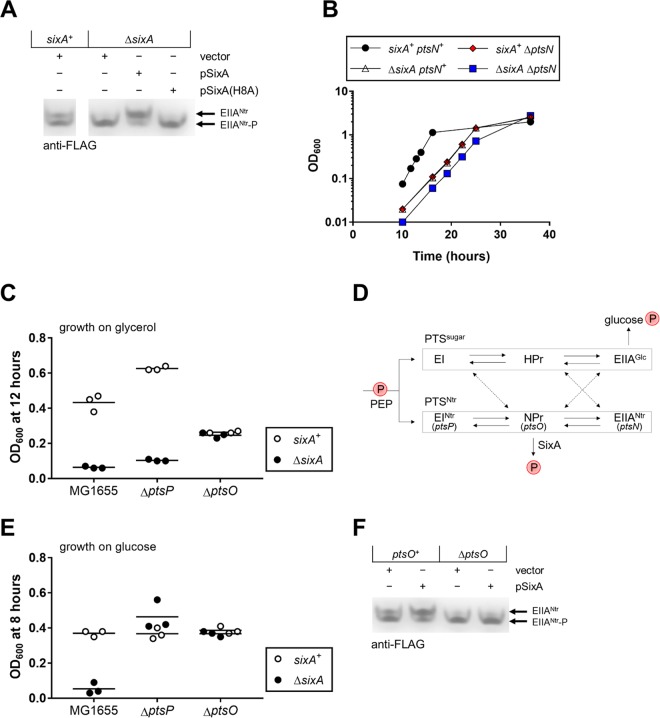

Comparing sixA+ and ΔsixA strains transformed with an empty vector and grown to stationary phase in LB medium, we found that the levels of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated EIIANtr were similar in the sixA+ strain whereas EIIANtr was predominantly phosphorylated in the ΔsixA strain (Fig. 3A, lanes 1 and 2). In addition, expression of wild-type SixA from a plasmid decreased EIIANtr-P levels and increased EIIANtr levels relative to the empty vector control (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 and 3). Finally, expression of the catalytic-site mutant SixA(H8A) did not change the relative abundances of EIIANtr and EIIANtr-P (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 and 4).

FIG 3.

Modulation of the PTSNtr by SixA. (A) Western blot of strains expressing a 3×FLAG-tagged EIIANtr from the native ptsN locus and containing empty vector pTrc99a, SixA-expressing plasmid pSixA, or SixA(H8A)-expressing plasmid pSixA(H8A). Cells were grown in LB Miller medium with ampicillin to stationary phase. Extraneous lanes from the blot are not shown. Strains are JES211 and JES212. The Western blot shown is representative of blots from three independent experiments. (B) Growth curves were measured for strains in glycerol minimal medium. Optical density at 600 nM (OD600) was monitored for two independent cultures of each strain. Symbols represent the average OD600; bars indicate ranges and are not visible where smaller than the symbol. Samples for this growth curve were collected at the same time as samples for the growth curve in Fig. 2A, so the data for the wild-type and ΔsixA strains are identical between figures. Strains are MG1655, JES13, JES208, and JES264. (C) Strains were grown in glycerol minimal medium for 12 h. Symbols represent the OD600 for individual cultures, and the horizontal black lines indicate the average OD600 from three biological replicates. Strains are MG1655, JES13, JES189, JES190, JES185, and JES186. (D) Schematic showing the phosphoryl group transfers within the PTSNtr, potential cross-phosphorylation from the PTSsugar, and proposed dephosphorylation by SixA. Phosphoryl groups from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) are passed by successive phosphotransfers between proteins in the PTSsugar and the PTSNtr. Dotted arrows show cross talk between the PTSsugar and the PTSNtr that has been reported to occur either in vitro or in vivo in some mutant backgrounds. Whereas the PTSsugar ultimately uses phosphoryl group transfer to facilitate uptake of carbohydrates such as glucose, there are no known phosphoryl group acceptors for the PTSNtr. We propose that SixA dephosphorylates NPr, providing a phosphoryl group sink for the PTSNtr. (E) Strains were grown in glucose minimal medium for 8 h. Symbols are as described for panel C. Strains are MG1655, JES13, JES189, JES190, JES185, and JES186. (F) Western blot of strains expressing a 3×FLAG-tagged EIIANtr from the native ptsN locus and containing empty vector pTrc99a or SixA-expressing plasmid pSixA. Cultures were grown in LB Miller medium with ampicillin to stationary phase. Strains are JES211 and JES271. The Western blot shown is representative of blots from three independent experiments.

Curiously, in testing LB and minimal medium cultures without a plasmid, we did not see a convincing difference in the levels of EIIANtr-P between sixA+ and ΔsixA strains. However, we note that for these cultures, EIIANtr was predominantly phosphorylated in the sixA+ strain, making it difficult to detect a further increase of EIIANtr phosphorylation in the ΔsixA strain. At present, we do not understand why the cells with and without a plasmid showed different effects. Nevertheless, the results described above show that SixA affects PTSNtr phosphorylation. In particular, the absence of SixA can lead to hyperphosphorylation of EIIANtr.

SixA modulates EIIANtr phosphorylation through NPr.

In our working model for the ΔsixA growth defect, SixA-null strains have increased phosphorylation of one or more PTSNtr proteins. This in turn causes the putative potassium-proton antiporter YcgO to become more active, and the ΔsixA cells suffer from the consequences of YcgO overactivity (Fig. 2D) (13). Consistent with this model, we found that the ΔsixA and ΔptsN strains have similar growth defects (Fig. 3B). The double deletion strain grew slightly more slowly than strains with either deletion alone, which accounts for the OD of the double deletion being slightly lower than the ODs of the single deletions.

According to a model proposed previously (13), unphosphorylated EIIANtr inhibits YcgO, and slow growth results from loss of this inhibition. We reasoned that the absence of EINtr or NPr, the first two components of the PTSNtr (Fig. 2D), would cause EIIANtr to be fully unphosphorylated. In this case, eliminating the SixA phosphatase would have no effect on growth. Indeed, deletion of sixA had no effect on the growth of an NPr-null strain, as anticipated (Fig. 3C). However, we found that deletion of sixA still produces a growth defect in a strain lacking EINtr.

We interpret this unexpected result in the context of our model in which the growth defect arises from increased phosphorylation of the PTSNtr. The fact that deleting sixA affected growth of an EINtr-null strain indicates that there is another source of phosphoryl groups for the PTSNtr, which we hypothesize is the sugar phosphotransferase system (PTSsugar) (Fig. 3D). The PTSsugar is a pathway homologous to the PTSNtr that facilitates carbohydrate uptake into the cell by phosphorylating transported carbohydrates (reviewed in references 16 and 17). Previous work has shown that EIIANtr can be phosphorylated by PTSsugar components (11, 18–21). This cross talk might be expected to occur during growth on non-PTS carbohydrates such as glycerol, which is characterized by high phosphorylation levels of PTSsugar proteins, but not for growth on a PTS sugar such as glucose, for which PTSsugar proteins are less phosphorylated (21, 22). We therefore hypothesized that growth on glucose would limit cross talk between the PTSsugar and PTSNtr. With this additional source of phosphorylation eliminated, we expected our original reasoning to apply, i.e., that deleting sixA should have no effect on growth in strains lacking either EINtr or NPr. In agreement with this hypothesis, deleting sixA had no effect on the growth of either EINtr-null or NPr-null strains in glucose minimal medium (Fig. 3E). These observations support our model suggesting that the ΔsixA slow-growth phenotype requires phosphoryl group transfer through the PTSNtr. Furthermore, the results presented in Fig. 3C and E imply that SixA modulates PTSNtr through NPr, since in the absence of NPr, the deletion of sixA has no effect.

To test whether SixA modulation of EIIANtr phosphorylation depends on NPr, we overexpressed SixA in the presence or absence of NPr and monitored levels of EIIANtr and EIIANtr-P. We observed significant EIIANtr phosphorylation in the absence of NPr for cells growing on LB (Fig. 3F, lanes 1 and 3), which is consistent with cross talk to EIIANtr. Furthermore, we found that SixA expression had no observable effect on EIIANtr-P in an NPr-null strain (Fig. 3F, lanes 3 and 4), supporting a model in which SixA acts on NPr.

DISCUSSION

Targets of SixA phosphatase activity.

Only one target of the SixA phosphohistidine phosphatase has been reported to date: E. coli ArcB. The interaction between these proteins was discovered through a screen for inhibitors of OmpR phosphorylation by the ArcB histidine phosphotransfer (HPt) domain (6). Further support was provided by in vitro data showing that SixA dephosphorylates ArcB and by in vivo results indicating that deleting sixA affects expression of an ArcA-dependent sdh transcriptional reporter under conditions of anaerobic respiration (6, 7). However, our experiments with a different ArcA-dependent reporter growing anaerobically on nitrate did not show any evidence that SixA modulates ArcA phosphorylation (Fig. 1E), and another study failed to see an effect of SixA on ArcA-regulated transcription under conditions of microaerobic growth (23). Thus, while the in vitro results reported in references 6 and 7 indicate that SixA can function as a phosphohistidine phosphatase, the role of SixA in modulating ArcB/ArcA signaling in vivo is unclear and requires further investigation.

The genetic and biochemical evidence presented here reveals a different—ArcB-independent—function for SixA: modulation of PTSNtr phosphorylation. As with other phosphotransferase systems, the activity of the PTSNtr depends on the phosphorylation states of its protein components. For example, many pathways are reportedly mediated by the unphosphorylated form of EIIANtr (12, 13, 24–29; reviewed in reference 17). The phosphorylation states of the PTSNtr proteins depend on a balance between the rate of phosphoryl transfer into the system from phosphoenolpyruvate and the rate of dephosphorylation. However, the mechanism by which PTSNtr proteins are dephosphorylated has not been established. Whereas the PTSsugar transfers phosphoryl groups to incoming sugars, providing a phosphoryl group sink for this system (Fig. 3D), no analogous sink for the PTSNtr has been reported. A recently proposed model for a global stress response pathway in Acinetobacter baumannii, a bacterium whose PTSNtr lacks an EIIANtr protein, suggests a dephosphorylation pathway for NPr via phosphotransfer to a serine on another protein, GigB, which is subsequently dephosphorylated by a phosphoserine phosphatase (30). However, E. coli and many other bacteria that have a PTSNtr do not have GigB.

One possible path for PTSNtr dephosphorylation is through cross talk with the PTSsugar (11, 18–21) (Fig. 3C), although the extent of this cross talk in wild-type bacteria is unknown. It is also possible that the PTSNtr can be dephosphorylated by spontaneous hydrolysis, due to the intrinsic instability of phosphohistidines of the phosphorylated PTSNtr proteins (31). Our work reveals a different mechanism that is mediated by the SixA phosphatase. On the basis of our observation that NPr is required for SixA to decrease EIIANtr phosphorylation (Fig. 3F), we propose that SixA removes phosphoryl groups from the PTSNtr via NPr. Furthermore, since phosphohistidine phosphatase activity has been demonstrated in vitro for SixA, we hypothesize that SixA directly dephosphorylates NPr-P.

We were led to the observation that SixA modulates the PTSNtr through our discovery of a growth defect for the ΔsixA mutant and through our suppressor analysis, which pointed to a connection with the growth defect associated with the ΔptsN mutant. We note, however, that we do not yet understand the mechanism underlying this growth defect or its suppression by ΔycgO.

Modulators of PTSNtr activation.

PTSNtr activation is influenced by both nitrogen and carbon metabolism. In particular, EINtr is inhibited by glutamine and may be stimulated by α-ketoglutarate (32–34). In addition, EIIANtr phosphorylation is influenced by PTS sugars through cross talk from the PTSsugar in at least some genetic backgrounds (19–21). Such cross talk could account for our observation that the severity of the ΔsixA growth defect depends on the carbon source. Non-PTS carbon substrates such as glycerol, maltose, and acetate produce pronounced ΔsixA growth defects that are easily observable as small colonies on solid media. Growth on the PTS sugar glucose, however, yields a subtle growth defect that we could detect only with optical density measurements. These phenotypes suggest a model in which, during growth of E. coli ΔsixA on non-PTS substrates, increased phosphorylation of the PTSsugar increases phosphorylation of the PTSNtr through cross talk, thereby exacerbating the ΔsixA slow-growth phenotype. In the context of this model, SixA is important for limiting cross talk from the PTSsugar in wild-type E. coli. However, it is also possible that the dependence of the ΔsixA slow-growth phenotype on carbon source reflects differences in phosphoenolpyruvate levels.

SixA may also provide an additional point of control for the PTSNtr, since factors affecting SixA expression or activity would modulate PTSNtr activation. For example, SixA protein levels may increase in response to cell envelope stress since sixA is a member of the σE regulon (35–38). Several examples of interactions between the PTSNtr and the cell envelope have been identified (39–41). Thus, increased dephosphorylation of the PTSNtr by SixA could play an important role in the cell envelope stress response.

Concluding remarks.

SixA is a well-conserved protein found in proteobacteria, actinobacteria, and cyanobacteria (5). Gene expression and proteome analyses have implicated SixA in biofilms of E. coli and Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (42–45), in nutrient limitation-induced phenotypes of Legionella and Salmonella (46–48), and macrophage infection with Salmonella (38). The roles of SixA in these contexts were interpreted to involve oxygen limitation, ArcB, or other two component systems but may instead involve SixA regulation of phosphotransferase systems. Does SixA function as a PTSNtr modulator in other bacterial species? Are there other targets of SixA? Our understanding of the roles of phosphatases in modulating histidine phosphorylation is in its early stages in bacterial and eukaryotic systems alike.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study are listed in Tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Reference, source, or construction |

|---|---|---|

| MG1655 | F− λ− ilvG rfb-50 rph-1 |

E. coli Genetic Stock Center (CGSC no. 7740) |

| JW2337 | ΔsixA::(FRT-kan-FRT) | 51 |

| JES12 | MG1655 ΔsixA::(FRT-kan-FRT) | P1vir(JW2337) × MG1655 |

| JES13 | MG1655 ΔsixA::(FRT) | JES12 treated with pCP20 |

| JW4364 | ΔarcA::(FRT-kan-FRT) | 51 |

| JW5536 | ΔarcB::(FRT-kan-FRT) | 51 |

| JES47 | MG1655 ΔarcA::(FRT-kan-FRT) | P1vir(JW4364) × MG1655 |

| JES48 | MG1655 ΔarcA::(FRT-kan-FRT) ΔsixA::(FRT) | P1vir(JW4364) × JES13 |

| JES49 | MG1655 ΔarcB::(FRT-kan-FRT) | P1vir(JW5536) × MG1655 |

| JES50 | MG1655 ΔarcB::(FRT-kan-FRT) ΔsixA::(FRT) | P1vir(JW5536) × JES13 |

| JES53 | MG1655 ΔarcA::(FRT) | JES47 treated with pCP20 |

| PK9483 | MG1655 lacZ::(kan PicdA(-58GGTGA-54)-lacZ) | 9 |

| JES252 | MG1655 lacZ::(kan PicdA(-58GGTGA-54)-lacZ) | P1vir(PK9483) × MG1655 |

| JES253 | MG1655 lacZ::(kan PicdA(-58GGTGA-54)-lacZ) ΔsixA::(FRT) | P1vir(PK9483) × JES13 |

| JES254 | MG1655 lacZ::(kan PicdA(-58GGTGA-54)-lacZ) ΔarcA::(FRT) | P1vir(PK9483) × JES53 |

| JW5184 | ΔycgO::(FRT-kan-FRT) | 51 |

| JES30 | MG1655 ΔycgO::(FRT-kan-FRT) | P1vir(JW5184) × MG1655 |

| JES31 | MG1655 ΔycgO::(FRT-kan-FRT) ΔsixA::(FRT) | P1vir(JW5184) × JES13 |

| JW3171 | ΔptsN::(FRT-kan-FRT) | 51 |

| JES208 | MG1655 ΔptsN::(FRT-kan-FRT) | P1vir(JW3171) × MG1655 |

| Z501 | ptsN::(ptsN-3×FLAG FRT-kan-FRT) | 15 |

| JES211 | MG1655 ptsN::(ptsN-3×FLAG FRT-kan-FRT) | P1vir(Z501) × MG1655 |

| JES212 | MG1655 ptsN::(ptsN-3×FLAG FRT-kan-FRT) ΔsixA::(FRT) | P1vir(Z501) × JES13 |

| JES264 | MG1655 ΔsixA::(FRT) ΔptsN::(FRT-kan-FRT) | P1vir(JW3171) × JES13 |

| JW2408 | ΔptsP::(FRT-kan-FRT) | 51 |

| JW3173 | ΔptsO::(FRT-kan-FRT) | 51 |

| JES189 | MG1655 ΔptsP::(FRT-kan-FRT) | P1vir(JW2408) × MG1655 |

| JES190 | MG1655 ΔptsP::(FRT-kan-FRT) ΔsixA::(FRT) | P1vir(JW2408) × JES13 |

| JES185 | MG1655 ΔptsO::(FRT-kan-FRT) | P1vir(JW3173) × MG1655 |

| JES186 | MG1655 ΔptsO::(FRT-kan-FRT) ΔsixA::(FRT) | P1vir(JW3173) × JES13 |

| JES270 | MG1655 ΔptsO::(FRT-cat-FRT) | See Materials and Methods |

| JES271 | MG1655 ptsN::(ptsN-3×FLAG FRT-kan-FRT) ΔptsO::(FRT-cat-FRT) | P1vir(JES270) × JES211 |

| E. cloni Replicator |

F−

mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) endA1 recA1 φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 araD139 Δ(ara, leu) 7697 galU galK rpsL nupG tonA (attL araC-PBAD-trfA250 bla attR) λ− |

Lucigen Corporation |

| PIR2 | F− Δlac169 rpoS(Am) robA1 creC510 hsdR514 endA recA1 uidA(ΔMluI)::pir | Invitrogen |

| TOP10 | F−

mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) endA1 recA1 φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 araD139 Δ(ara-leu) 7697 galU galK rpsL nupG |

Invitrogen |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Relevant genotype | Reference or construction |

|---|---|---|

| pTrc99a | lacIq Ptrc, MCS from pUC18, rrnB(Ter) bla ori pMB1 | 59 |

| pSixA (pJS17) | pTrc99a sixA | NcoI-sixA-F + HindIII-sixA-R |

| pSixA(H8A) (pJS21) | pTrc99a sixA(H8A) | sixA-dead-F + sixA-deadCRIM-R2 |

| pMG91 (pSMART) | pSMART VC BamHI oriV ori2 repE parABC cat | Lucigen Corporation |

| pYcgO (pJS15) | pSMART ycgO | EcoRI-PcvrA-F + HindIII-cvrA-R |

| pBR322 | rop, tet, bla, ori pMB1 | 60 |

| pEB52 | pTrc99a with NcoI restriction site removed | 61 |

| pEIIANtr (pJS37) | pEB52 ptsN-3×FLAG | EcoRI-ptsN-F + HindIII-ptsN-3×FLAG-R2 |

| pRL27 | oriR6Kγ aph oriT PtetA-tnp | 54 |

| pCP20 | λcI857(ts) λpR-FLP repA101(ts) oriR101 bla cat | 50 |

| pEL8 | pCP20 Δcat | 62 |

| pKD3 | oriR6Kγ bla FRT-cat-FRT | 63 |

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence | Resulting construct or purpose |

|---|---|---|

| NcoI-sixA-F | GCATGCCATGGGCGGTGCAATATGCAAG | pSixA |

| HindIII-sixA-R | GCATCGAAGCTTGGAACTCATCAGATAG | pSixA |

| sixA-dead-F | GGCGACGCAGCCCTCGATG | pSixA(H8A) |

| sixA-deadCrim-R2 | CGCACGCATGATAAAAACTTG | pSixA(H8A) |

| EcoRI-PcvrA-F | CGCTCGAATTCTGATCGGTACACCGTGGATG | pYcgO |

| HindIII-cvrA-R | CCAGTAAGCTTCAACCGGCGATAGATGCTTC | pYcgO |

| EcoRI-ptsN-F | GCATGGAATTCTGAGTGGGCAGGTTCTTAG | pEIIANtr |

| HindIII-ptsN-3×FLAG-R2 | CCAGTAAGCTTCAGCTCCAGCCTACATTAC | pEIIANtr |

| psyn-u1 | CCTGACGGATGGCCTTTTTG | PCR-amplify FRT-cat-FRT |

| oriR6Kseqprim1 | GACACAGGAACACTTAACGGC | PCR-amplify FRT-cat-FRT |

| pBR322-seq-For | CCTGCTCGCTTCGCTACTTG | Sequence insertions from plasmid library screen |

| pBR322-seq-Rev | GCGATATAGGCGCCAGCAAC | Sequence insertions from plasmid library screen |

Growth conditions.

Rich medium consisted of LB Miller medium (49) (containing [per liter] 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 10 g NaCl). Defined medium consisted of minimal A medium (49) (containing [per liter] 10.5 g K2HPO4, 4.5 g KH2PO4, 1 g (NH4)2SO4, and 0.5 g Na citrate dihydrate) with 0.2% of the indicated carbon source and 1 mM MgSO4 added after autoclaving. Minimal medium plates contained 1.5% agar. Bacteria were grown at 37°C, except during some steps of strain construction, when cultures were grown at 30°C to maintain temperature-sensitive plasmids. The final concentrations of the antibiotics ampicillin, kanamycin, and chloramphenicol were 50 to 100, 25 to 50, and 12 to 25 µg/ml, respectively. Plasmids containing sixA or ptsN were used without IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induction and thus expressed the corresponding proteins from the basal activity of the trc promoter.

For anaerobic growth, minimal medium containing 0.2% glucose and 0.1% Casamino Acids was inoculated with a single colony and transferred to an anaerobic chamber, and the culture was grown overnight to stationary phase. The medium for the following day's cultures, which was the same as that used for the overnight cultures but also contained 40 mM KNO3, was also put in the anaerobic chamber at that time. The overnight cultures were used to inoculate the medium containing KNO3 (1:500 dilution of the inoculum) and were grown for 7 to 8 doublings anaerobically.

Strain construction.

Phage transduction was performed with P1vir as described in reference 49. FLP recombination target (FRT)-flanked kanamycin resistance cassettes were excised from the genome with FLP recombinase expressed from pCP20 (50). Gene deletions from the Keio collection (51) were confirmed by PCR.

To construct JES270, a chloramphenicol-resistant and kanamycin-sensitive ΔptsO strain, a PCR fragment containing FRT-cat-FRT was amplified from pKD3 with primers psyn-u1 and oriR6kseqprim1. The resulting DNA segment was then electroporated into strain JES185/pEL8, and cells were selected on 12 μg/ml chloramphenicol to exchange FRT-kan-FRT with FRT-cat-FRT. The resulting strain was confirmed to be kanamycin and ampicillin sensitive, indicating loss of both the kanamycin resistance gene and plasmid pEL8.

Plasmid construction.

The insertions in all engineered plasmids were verified to be correct by DNA sequencing.

To construct sixA expression plasmid pSixA, primers NcoI-sixA-F and HindIII-sixA-R were used to amplify the sixA gene from MG1655 genomic DNA. The resulting DNA segment was digested with NcoI and HindIII and cloned into pTrc99a, which was digested with the same enzymes. A plasmid expressing the H8A sixA mutant was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis as follows: plasmid pSixA was amplified with primers sixA-dead-F and sixA-deadCRIM-R2, the ends were phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase, and the resulting DNA was circularized by blunt-end ligation with T4 DNA ligase, generating pSixA(H8A).

To construct the ycgO expression plasmid pYcgO, the ycgO gene and roughly 500 bp of upstream DNA were amplified from MG1655 genomic DNA with primers EcoRI-PcvrA-F and HindIII-cvrA-R. The resulting PCR product was digested with EcoRI and HindIII and ligated into EcoRI- and HindIII-digested pMG91, a derivative of the single-copy plasmid pSMART.

The plasmid for FLAG-tagged ptsN expression was constructed as follows. The ptsN-3×FLAG sequence from Z501 genomic DNA was amplified with primers EcoRI-ptsN-F and HindIII-ptsN-3×FLAG-R2. The resulting PCR product was cloned into EcoRI- and HindIII-digested pEB52, a derivative of pTrc99a, generating pEIIANtr.

Growth curves.

LB Miller medium was inoculated with a single colony and grown to stationary phase with aeration in a roller drum. The overnight culture was then used to inoculate 50 ml of medium with a 1:1,000 dilution, and the flasks were aerated on a shaker. For each time point, three aliquots were removed and the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of each was measured. For determination of the wild-type strain’s growth curve in glycerol minimal medium (Fig. 1A), the exponential-phase and stationary-phase measurements were obtained from two separate experiments. The data for the growth curves presented in Fig. 2A and Fig. 3B were collected in the same experiment, so the curves for MG1655 and JES13 are identical.

Optical density endpoint assay.

Our initial experiments with endpoint assays revealed that cells in some cultures were aggregating, which was manifested by the flocculation and sedimentation of standing cultures and was also visible by microscopy. We suspect that spontaneous activation of antigen 43, which is subject to random phase variation and causes autoaggregation when expressed (52, 53), was responsible, since deletion of flu eliminated this flocculation phenotype. The flocculating cultures were not used for endpoint assays because they produced lower optical densities than nonflocculating cultures.

LB Miller cultures were inoculated with single colonies and grown overnight to stationary phase with aeration in a roller drum. These cultures were then left standing on the benchtop at room temperature for at least 1 h to monitor for flocculation of the culture. Those tubes that did not show flocculation were then used to inoculate 2-ml cultures of minimal medium (1:1,000 dilution), which were grown with aeration in a roller drum. Incubation times were chosen to catch wild-type cultures in exponential phase.

β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase assays were performed essentially as described previously (49). To ensure that protein synthesis was stopped at the appropriate times, 100 µg/ml streptomycin was added to cultures after they were removed from the anaerobic chamber and placed on ice.

Genetic screens.

For transposon mutagenesis, electrocompetent ΔsixA JES13 was transformed with pRL27, which contains a hyperactive Tn5 transposase (54). After electroporation and recovery in SOC medium (containing [per liter] 20 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, 0.5 g NaCl, with 20 mM MgSO4 and 0.4% glucose added after autoclaving) for over 1 h, the cells were incubated in SOC medium with kanamycin for 6 h to select for mutants. Aliquots were then plated on maltose minimal medium agar, and >16,000 colonies were screened to identify suppressor mutants. Genomic DNA sequences flanking the sites of transposon insertions were identified as described previously (55, 56).

For the multicopy suppressor screen, JES13 was transformed with a plasmid library prepared from MG1655 genomic DNA fragments cloned into pBR322 (57) and was screened on minimal agar medium containing several different supplements: (i) glucose with 0.1% Casamino Acids and 15 to 30 mM procaine HCl, (ii) maltose, (iii) glycerol, and (iv) acetate. Over 11,000 colonies were screened to identify plasmids that suppress slow growth. Plasmids were isolated, retransformed into JES13, and tested on maltose minimal medium agar plates to confirm that the plasmid suppressed the slow-growth phenotype. Insert sequences were determined by sequencing with primers pBR322-seq-For/pBR322-seq-Rev.

Potassium measurements.

LB Miller overnight cultures inoculated from single colonies were used to inoculate 2-ml cultures of glycerol minimal medium, which were grown overnight in a roller drum to optical densities of approximately 0.2. Cultures were harvested by centrifugation through a layer of a 2:1 (vol/vol) mixture of dibutyl phthalate and dioctyl phthalate following the procedure described in reference 13. The cell pellet was suspended in 0.1 ml 1 N nitric acid and digested for 1 to 3 days. The samples were then diluted with 0.95 ml diluent (2% nitric acid, 0.5% HCl) and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min. One milliliter of supernatant was removed and mixed with 2 ml more diluent. 39K was measured in the samples and in standard reference controls using an Agilent 7900 inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS). The limit of quantification was determined to be 0.1 mg/liter. Potassium content was determined as nanomoles of potassium per OD600 of the culture prior to harvesting.

EIIANtr phosphorylation assay.

EIIANtr phosphorylation assays were performed similarly to those described previously (14, 15, 58). Native gels were prepared with 10% 37.5:1 acrylamide and 375 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.8) and cast using a Mini-Protean II system (Bio-Rad). Cultures were grown overnight in LB Miller medium containing ampicillin to stationary phase. Cell pellets from 0.5 ml or 1 ml of culture were suspended in 0.4 ml or 0.8 ml of loading dye (10% glycerol, 40 mM glycine, 5 mM Tris HCl, 0.005% bromophenol blue, pH 8.8) for the experiments whose results are presented in Fig. 3A or Fig. 3F, respectively. The cells were then sonicated on ice and centrifuged to pellet cell debris. Samples were run at 4°C with a running buffer consisting of 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine (pH 8.3) until the dye reached the end of the gel.

After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a 0.45-μm-pore-size Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore) using a semidry transfer apparatus and transfer buffer consisting of 20% methanol, 25 mM Tris, and 192 mM glycine (pH 8.3). The membrane was blocked with 5% milk–Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) (containing [per liter] 8 g NaCl, 0.38 g KCl, 3 g Tris base, 500 μl Tween 20, pH 7.4). Anti-FLAG mouse antibody (GeneTex; catalog no. GTX82562), digital anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP) antibody (Kindle Biosciences), and a KwikQuant Western blot detection kit and imager (Kindle Biosciences) were used to probe and image membranes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Manuela Roggiani and Annie Chen for preparing and sharing the genomic DNA plasmid library, Christopher Sikich for assistance in validating strains, Patricia Kiley and Boris Görke for providing strains, and Erica R. McKenzie for processing ICP-MS samples.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM080279) and by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under grant no. DGE-1321851.

J.E.S. and M.G. both contributed to the design, execution, analysis, and interpretation of experiments and both also drafted, revised, and approved the manuscript.

Footnotes

Citation Schulte JE, Goulian M. 2018. The phosphohistidine phosphatase SixA targets a phosphotransferase system. mBio 9:e01666-18. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01666-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Attwood PV, Muimo R. 2018. The actions of NME1/NDPK-A and NME2/NDPK-B as protein kinases. Lab Invest 98:283–290. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2017.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adam K, Hunter T. 2018. Histidine kinases and the missing phosphoproteome from prokaryotes to eukaryotes. Lab Invest 98:233–247. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2017.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamada K, Kato M, Shimizu T, Ihara K, Mizuno T, Hakoshima T. 2005. Crystal structure of the protein histidine phosphatase SixA in the multistep His-Asp phosphorelay. Genes Cells 10:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rigden DJ. 2008. The histidine phosphatase superfamily: structure and function. Biochem J 409:333–348. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hakoshima T, Ichihara H. 2007. Structure of SixA, a histidine protein phosphatase of the ArcB histidine-containing phosphotransfer domain in Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol 422:288–304. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)22014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogino T, Matsubara M, Kato N, Nakamura Y, Mizuno T. 1998. An Escherichia coli protein that exhibits phosphohistidine phosphatase activity towards the HPt domain of the ArcB sensor involved in the multistep His-Asp phosphorelay. Mol Microbiol 27:573–585. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsubara M, Mizuno T. 2000. The SixA phospho-histidine phosphatase modulates the ArcB phosphorelay signal transduction in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett 470:118–124. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01303-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nichols RJ, Sen S, Choo YJ, Beltrao P, Zietek M, Chaba R, Lee S, Kazmierczak KM, Lee KJ, Wong A, Shales M, Lovett S, Winkler ME, Krogan NJ, Typas A, Gross CA. 2011. Phenotypic landscape of a bacterial cell. Cell 144:143–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park DM, Kiley PJ. 2014. The influence of repressor DNA binding site architecture on transcriptional control. mBio 5:e01684-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01684-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pflüger-Grau K, Görke B. 2010. Regulatory roles of the bacterial nitrogen-related phosphotransferase system. Trends Microbiol 18:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powell BS, Court DL, Inada T, Nakamura Y, Michotey V, Cui X, Reizer A, Saier MH Jr, Reizer J. 1995. Novel proteins of the phosphotransferase system encoded within the rpoN operon of Escherichia coli. Enzyme IIANtr affects growth on organic nitrogen and the conditional lethality of an erats mutant. J Biol Chem 270:4822–4839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee CR, Cho SH, Yoon MJ, Peterkofsky A, Seok YJ. 2007. Escherichia coli enzyme IIANtr regulates the K+ transporter TrkA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:4124–4129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609897104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma R, Shimada T, Mishra VK, Upreti S, Sardesai AA. 2016. Growth inhibition by external potassium of Escherichia coli lacking PtsN (EIIANtr) is caused by potassium limitation mediated by YcgO. J Bacteriol 198:1868–1882. doi: 10.1128/JB.01029-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pflüger K, di Bartolo I, Velázquez F, de Lorenzo V. 2007. Non-disruptive release of Pseudomonas putida proteins by in situ electric breakdown of intact cells. J Microbiol Methods 71:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bahr T, Lüttmann D, März W, Rak B, Görke B. 2011. Insight into bacterial phosphotransferase system-mediated signaling by interspecies transplantation of a transcriptional regulator. J Bacteriol 193:2013–2026. doi: 10.1128/JB.01459-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deutscher J, Francke C, Postma PW. 2006. How phosphotransferase system-related protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70:939–1031. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00024-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galinier A, Deutscher J. 2017. Sophisticated regulation of transcriptional factors by the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate: sugar phosphotransferase system. J Mol Biol 429:773–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rabus R, Reizer J, Paulsen I, Saier MH Jr.. 1999. Enzyme INtr from Escherichia coli. A novel enzyme of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system exhibiting strict specificity for its phosphoryl acceptor, NPr. J Biol Chem 274:26185–26191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pflüger K, de Lorenzo V. 2008. Evidence of in vivo cross talk between the nitrogen-related and fructose-related branches of the carbohydrate phosphotransferase system of Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol 190:3374–3380. doi: 10.1128/JB.02002-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmer B, Hillmann A, Görke B. 2008. Requirements for the phosphorylation of the Escherichia coli EIIANtr protein in vivo. FEMS Microbiol Lett 286:96–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lüttmann D, Göpel Y, Görke B. 2015. Cross-talk between the canonical and the nitrogen-related phosphotransferase systems modulates synthesis of the KdpFABC potassium transporter in Escherichia coli. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 25:168–177. doi: 10.1159/000375497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bettenbrock K, Sauter T, Jahreis K, Kremling A, Lengeler JW, Gilles ED. 2007. Correlation between growth rates, EIIACrr phosphorylation, and intracellular cyclic AMP levels in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 189:6891–6900. doi: 10.1128/JB.00819-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bekker M, Alexeeva S, Laan W, Sawers G, Teixeira de Mattos J, Hellingwerf K. 2010. The ArcBA two-component system of Escherichia coli is regulated by the redox state of both the ubiquinone and the menaquinone pool. J Bacteriol 192:746–754. doi: 10.1128/JB.01156-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lüttmann D, Heermann R, Zimmer B, Hillmann A, Rampp IS, Jung K, Görke B. 2009. Stimulation of the potassium sensor KdpD kinase activity by interaction with the phosphotransferase protein IIANtr in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 72:978–994. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pflüger-Grau K, Chavarría M, de Lorenzo V. 2011. The interplay of the EIIANtr component of the nitrogen-related phosphotransferase system (PTSNtr) of Pseudomonas putida with pyruvate dehydrogenase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1810:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lüttmann D, Göpel Y, Görke B. 2012. The phosphotransferase protein EIIANtr modulates the phosphate starvation response through interaction with histidine kinase PhoR in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 86:96–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prell J, Mulley G, Haufe F, White JP, Williams A, Karunakaran R, Downie JA, Poole PS. 2012. The PTSNtr system globally regulates ATP-dependent transporters in Rhizobium leguminosarum. Mol Microbiol 84:117–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karstens K, Zschiedrich CP, Bowien B, Stülke J, Görke B. 2014. Phosphotransferase protein EIIANtr interacts with SpoT, a key enzyme of the stringent response, in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Microbiology 160:711–722. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.075226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muriel-Millán LF, Moreno S, Gallegos-Monterrosa R, Espín G. 2017. Unphosphorylated EIIANtr induces ClpAP-mediated degradation of RpoS in Azotobacter vinelandii. Mol Microbiol 104:197–211. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gebhardt MJ, Shuman HA. 2017. GigA and GigB are master regulators of antibiotic resistance, stress responses, and virulence in Acinetobacter baumannii. J Bacteriol 199:e00066-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodwin R. 2015. Influence of intracellular nitrogen status and dynamic control of central metabolism in the plant symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. PhD thesis. University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee CR, Park YH, Kim M, Kim YR, Park S, Peterkofsky A, Seok YJ. 2013. Reciprocal regulation of the autophosphorylation of enzyme INtr by glutamine and α-ketoglutarate in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 88:473–485. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodwin RA, Gage DJ. 2014. Biochemical characterization of a nitrogen-type phosphotransferase system reveals that enzyme EINtr integrates carbon and nitrogen signaling in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 196:1901–1907. doi: 10.1128/JB.01489-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ronneau S, Petit K, De Bolle X, Hallez R. 2016. Phosphotransferase-dependent accumulation of (p)ppGpp in response to glutamine deprivation in Caulobacter crescentus. Nat Commun 7:11423. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rezuchova B, Miticka H, Homerova D, Roberts M, Kormanec J. 2003. New members of the Escherichia coli σE regulon identified by a two-plasmid system. FEMS Microbiol Lett 225:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhodius VA, Suh WC, Nonaka G, West J, Gross CA. 2006. Conserved and variable functions of the σE stress response in related genomes. PLoS Biol 4:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mutalik VK, Nonaka G, Ades SE, Rhodius VA, Gross CA. 2009. Promoter strength properties of the complete sigma E regulon of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol 191:7279–7287. doi: 10.1128/JB.01047-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Overall CC, Johnson RC, Jones MB, McDermott JE, Heffron F, Adkins JN, Cambronne ED. 2015. ChIP-seq analysis of the σE regulon of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium reveals new genes implicated in heat shock and oxidative stress response. PLoS One 10:e0138466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayden JD, Ades SE. 2008. The extracytoplasmic stress factor, σE, is required to maintain cell envelope integrity in Escherichia coli. PLoS One 3:e1573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim HJ, Lee CR, Kim M, Peterkofsky A, Seok YJ. 2011. Dephosphorylated NPr of the nitrogen PTS regulates lipid A biosynthesis by direct interaction with LpxD. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 409:556–561. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee J, Park YH, Kim YR, Seok YJ, Lee CR. 2015. Dephosphorylated NPr is involved in an envelope stress response of Escherichia coli. Microbiology 161:1113–1123. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beloin C, Valle J, Latour-Lambert P, Faure P, Kzreminski M, Balestrino D, Haagensen JA, Molin S, Prensier G, Arbeille B, Ghigo JM. 2004. Global impact of mature biofilm lifestyle on Escherichia coli K-12 gene expression. Mol Microbiol 51:659–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hancock V, Klemm P. 2007. Global gene expression profiling of asymptomatic bacteriuria Escherichia coli during biofilm growth in human urine. Infect Immun 75:966–976. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01748-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang XS, García-Contreras R, Wood TK. 2008. Escherichia coli transcription factor YncC (McbR) regulates colanic acid and biofilm formation by repressing expression of periplasmic protein YbiM (McbA). ISME J 2:615–631. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vera M, Krok B, Bellenberg S, Sand W, Poetsch A. 2013. Shotgun proteomics study of early biofilm formation process of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 on pyrite. Proteomics 13:1133–1144. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jules M, Buchrieser C. 2007. Legionella pneumophila adaptation to intracellular life and the host response: clues from genomics and transcriptomics. FEBS Lett 581:2829–2838. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jordan RS. 2015. The roles of two-component and phosphorelay systems in the starvation-stress response of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Masters thesis. University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones TD. 2011. The role and regulation of the phosphohistidine phosphatase SixA in the starvation-stress response of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Masters thesis. University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller JH. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Plainview, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cherepanov PP, Wackernagel W. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00193-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol 2:2006.0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diderichsen B. 1980. flu, a metastable gene controlling surface properties of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 141:858–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van der Woude MW, Henderson IR. 2008. Regulation and function of Ag43 (Flu). Annu Rev Microbiol 62:153–169. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Larsen RA, Wilson MM, Guss AM, Metcalf WW. 2002. Genetic analysis of pigment biosynthesis in Xanthobacter autotrophicus Py2 using a new, highly efficient transposon mutagenesis system that is functional in a wide variety of bacteria. Arch Microbiol 178:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s00203-002-0442-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Batchelor E, Walthers D, Kenney LJ, Goulian M. 2005. The Escherichia coli CpxA-CpxR envelope stress response system regulates expression of the porins OmpF and OmpC. J Bacteriol 187:5723–5731. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.16.5723-5731.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yadavalli SS, Carey JN, Leibman RS, Chen AI, Stern AM, Roggiani M, Lippa AM, Goulian M. 2016. Antimicrobial peptides trigger a division block in Escherichia coli through stimulation of a signalling system. Nat Commun 7:12340. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen AI, Goulian M. 2018. A network of regulators promotes dehydration tolerance in Escherichia coli. Environ Microbiol 20:1283–1295. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jahn S, Haverkorn van Rijsewijk BR, Sauer U, Bettenbrock K. 2013. A role for EIIANtr in controlling fluxes in the central metabolism of E. coli K12. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833:2879–2889. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amann E, Ochs B, Abel K-J. 1988. Tightly regulated tac promoter vectors useful for the expression of unfused and fused proteins in Escherichia coli. Gene 69:301–315. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90440-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bolivar F, Rodriguez RL, Greene PJ, Betlach MC, Heyneker HL, Boyer HW, Crosa JH, Falkow S. 1977. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicle. II. A multipurpose cloning system. Gene 2:95–113. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(77)90000-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lippa AM, Goulian M. 2012. Perturbation of the oxidizing environment of the periplasm stimulates the PhoQ/PhoP system in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 194:1457–1463. doi: 10.1128/JB.06055-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Libby EA, Ekici S, Goulian M. 2010. Imaging OmpR binding to native chromosomal loci in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 192:4045–4053. doi: 10.1128/JB.00344-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]