ABSTRACT

Background: Mystery client methodology is a form of participatory research that provides a unique opportunity to monitor and evaluate the performance of health care providers or health facilities from the perspective of the service user. However, there are no systematic reviews that analyse the use of mystery clients in adolescent sexual and reproductive health (ASRH) research and monitoring and evaluation of programmes.

Objective: To assess the use of adolescent mystery clients in examining health care provider and facility performance in providing ASRH services in high, middle, and low-income countries.

Methods: We carried out a systematic review of published journal articles and reports from the grey literature on this topic from 2000 to 2017 (inclusive). Thirty research evaluations/studies were identified and included in the analysis. We identified common themes through thematic analysis.

Results: The findings reveal that researchers and evaluators used mystery client methodology to observe client-provider relationships, and to reduce observation bias, in government or private health facilities, NGOs, and pharmacies. The mystery clients in the evaluations/studies were young people who played varying roles; in most cases, they were trained for these roles. Most reported good experiences and friendly providers; however, some reported lack of privacy and confidentiality, lack of sufficient written/verbal information, and unfavourable experiences such as sexual harassment and judgmental comments. Female mystery clients were more likely than males to report unfavourable experiences. Generally, the methodology was considered useful in monitoring and evaluating the attitudes of health service providers and ASRH service provision.

Conclusions: The research evaluations/studies in this review highlight the usefulness of mystery clients as a method to gain insight, from an adolescent perspective, on the quality of ASRH services for research and monitoring and evaluation of programmes.

KEYWORDS: Youth friendly services, adolescent sexual and reproductive health, participatory research methods

Background

Mystery client (MC) methodology is a form of participatory research that provides a unique opportunity to monitor and evaluate the performance of health care providers or health facilities from the perspective of the service user [1]. MC methodology has been used in health research for more than 20 years [2,3], and Gonsalves and Hindin’s recent review on youth access to SRH care in pharmacies includes studies that involved mystery clients [4]. However, there are no systematic reviews published to our knowledge that analyse the uses, advantages, and disadvantages of MC methodology in adolescent sexual and reproductive health (ASRH) research and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of programmes. This review focuses on describing the use of adolescent MCs in examining adolescent health service provision.

While this methodology has been used among adults and adolescents alike [5–8], in this review we consider the use of adolescent MCs to assess the friendliness of adolescent health services across high-, middle-, and low-income countries. ASRH services vary by type of care provided, cadres of health care providers or healthcare facilities (i.e. hospitals, clinics and pharmacies), and thus this review includes evaluations/studies that cover a range of contexts, including but not limited to family planning services, services for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and pharmacy services in formal and informal settings.

In this review, we set out to answer the following questions:

Why was the MC methodology used in the evaluation/study of ASHR services?

What were the roles assigned, how were the MCs prepared, and what methods and tools were used to carry out the assessment?

What types of healthcare facilities and cadres of health care providers were examined with MCs?

What were the principal findings from the methodology in the evaluations/studies?

What were the overall perceptions of the use of MCs in assessing health care provider and facility performance?

Methods

Data collection

Though no formal protocol was developed for this research, we followed the PRISMA guidelines to perform a systematic review of the literature, including journal articles and grey literature, issued between the years of 2000 and 2017 (inclusive) that used adolescent MCs as part of their methodology to assess ASRH health care provider and health facility performance [9]. We sought evaluations/studies published in English and Spanish across low-, middle-, and high-income countries that used the MC methodology as part of their study to understand adolescents’ access to ASRH health care.

We conducted the literature search with Google, Google scholar, POPLINE, PubMed, GIFT, JSTOR, MEDLINE, and EMBASE. The original literature review was conducted in 2015, and in 2017 the paper was updated and expanded upon with an additional literature search. The review helped identify organizations that used the MC methodology, which included the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH), the USA Agency for International Development (USAID), Pathfinder International, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), and Advocates for Youth. Table 1 describes the complete search strategy for this review, including the keywords and hand searches used to find the relevant publications. An initial abstract screening, followed by a full text screening was conducted. The full text was screened in case that the information presented in the abstract was not sufficient to make a conclusive decision. Authors were only contacted in the cases that their studies/evaluations were inaccessible online. The search yielded over 1000 publications, and we screened the publications by title, abstract, and full paper in cases where the abstracts were unclear. We identified 51 total research evaluations/studies from this screening and the additional update in 2017.

Table 1.

Search protocols.

| Databases |

| Google, Google scholar, POPLINE, PubMed, GIFT, JSTOR, MEDLINE, EMBASE |

| Hand Searches |

| Use of mystery clients to assess adolescent health worker behaviour, mystery client used to evaluate ASRH, mystery client adolescent health, mystery shopper adolescent health, adolescent undercover patients, young people mystery clients, mystery client youth |

| Search Terms |

| Mystery clients terms |

| Mystery clients, mystery shoppers, mystery patients, simulated patients, undercover patients, dummy patients, undercover consumers |

| Adolescent terms |

| Adolescents, young people, youth, teenagers |

| Health service terms |

| Sexual and reproductive health service, sexual health, reproductive health, ASHR, contraceptive services, contraction, family planning, condoms, oral contraception, pharmacy services, accessibility, health worker behaviour, provider attitudes, provider behaviour, client satisfaction |

Data analysis

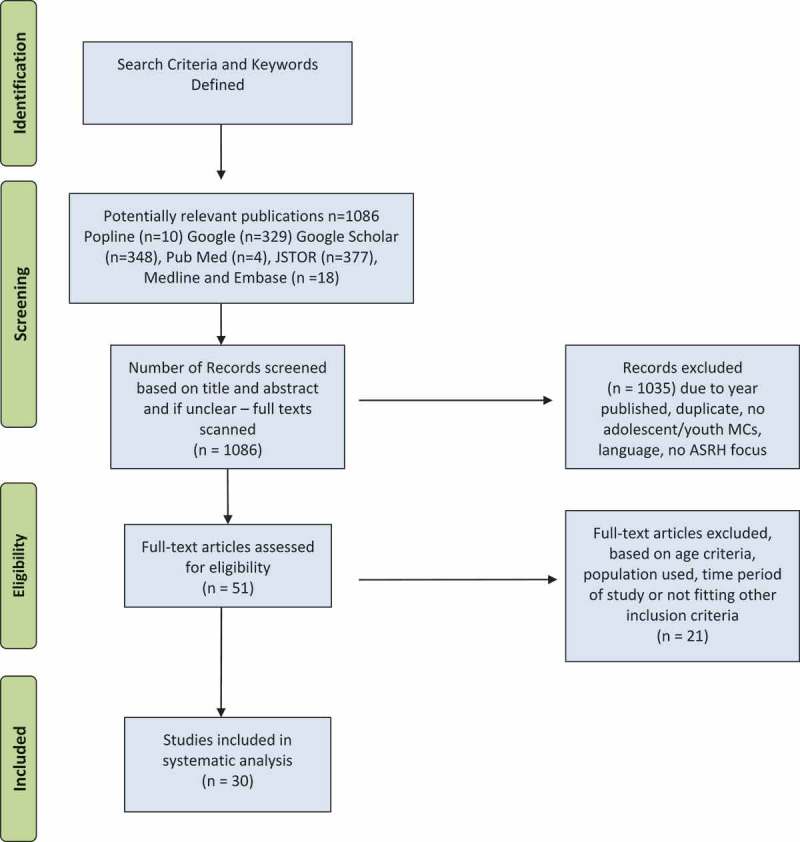

We used a list of inclusion criteria Table 2 to review identified publications for their validity. Of the 51 publications identified in the initial screening, 21 were excluded because they did not align with these criteria. Although the inclusion criteria initially included articles in Spanish and English, no articles in the Spanish language were finally included in this paper as they did not meet the other criteria or because documents reporting on the research could not be found. Two independent reviewers carried out the literature review, and consulted with a third party researcher regarding disagreements. The PRISMA flow diagram Figure 1 organizes the details of our search.

Table 2.

Inclusion criteria.

| Time frame | 2000–2017 |

|---|---|

| Study Population | Focused on service provision for young people (10–24), male or female |

| Study Design Methodology | Utilized quantitative and/or qualitative methods Included an evaluation portion using adolescent MCs (males or females, aged 10–24) MCs assessed health provider (nurse, doctor, pharmacists, technician, staff, receptionist) behaviour when delivering ASRH care |

| Geographic Scope |

Low and low-middle income countries – (African, South East-Asian, Latin and South American, Western-Pacific, Eastern-Mediterranean Regions) High-income countries – (USA, Western Europe) |

| ASRH care | Focusing on how adolescents perceived or observed health provider behaviour during mystery client visits to service providers of ASRH care |

| Language | Published in English or Spanish |

| Article type | Peer-reviewed journal articles (evaluations/studies), grey literature |

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

We analysed all evaluations/studies with a framework based on six principal criteria: i) overall objective and methodology; 2) justification of the use of MC methodology; 3) the role of MCs and the training/support they received; 4) the setting and type of health workers assessed; 5) principal findings; and 6) perceptions on the use of MCs. The 30 evaluations/studies were thereafter thematically analysed for shared methods used, justifications, and common findings. Thematic analysis consisted of intently sorting studies/evaluations based on shared characteristics including types and certain elements such as training MC in their methodologies, analytical methods, reasons for using MC, and outcomes of having used MCs.

An analysis of the quality of the evaluations/studies was beyond the scope of this paper as the methodology was used in different contexts. While some used the methodology as an evaluation method for particular programmes, others reported using it as a research method to help design and develop interventions. The intentional lack of incorporation of a quality assessment stemmed from the aim of the analysis focusing on the types of MC methodologies and outcomes recorded, which would not have accurately reflected the available information if studies were excluded based on quality. The small scale, lower quality status of some studies is recognised and further reflected upon in the limitations section.

Context

The involvement of young people in research processes is an important part of planning and implementation of programmes and interventions. Adolescents and young people have increasingly been involved in research at different stages; planning, implementation, and M&E [10]. Researchers no longer view adolescents as just subjects, but as equal partners and contributors in research planning and implementation [10,11]. There has beengrowing calls for the participation of young people in programme and policy development [12], and the MC method provides an excellent opportunity.

In the MC method, participants take on a role other than themselves when receiving health services. The health care providers are typically unaware of the undercover nature of the client and thereby allow the client to observe their natural behaviour [13]. MC methodology is considered a participatory research method as it fulfils the criteria set out by Cornwall and Jewkes [14] and it ‘emphasises participation and action’ [14] while encouraging the involvement of ‘people whose actions and worlds are under study’ [11]. It provides important insight from the user’s perspective of health services or other programmes. MCs are also referred to as simulated patients, undercover patients, or mystery shoppers [13].

Critiques of the methodology include difficulties in recruitment and training of MCs, recall bias, reliability of information provided by the MCs, and the limitations to the type of information that can be collected [1]. However, research has continued to affirm its effectiveness and value [15].

Results

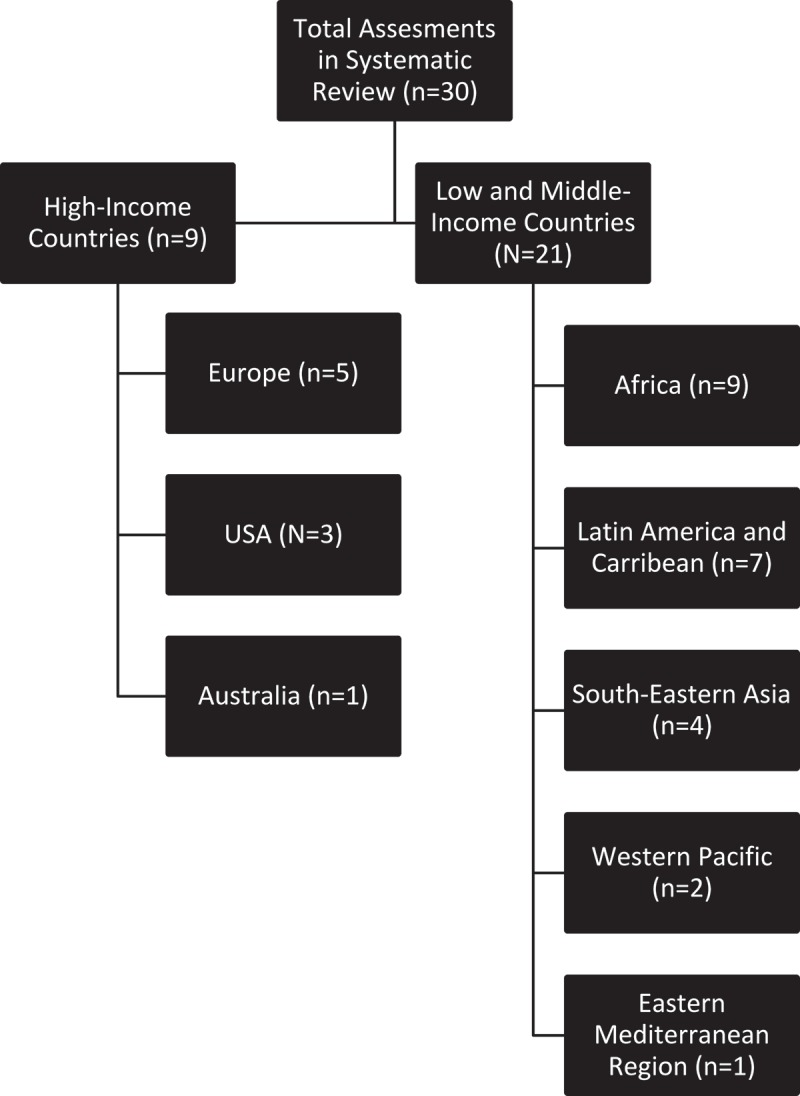

Our findings and conclusions are based on the final selection of 30 evaluations/studies. Nine of these (30%) were conducted in high-income countries and 21 (70%) in low- and middle-income countries. The geographical distribution of the evaluations/studies in this systematic review is displayed in Figure 2. Of the 30 evaluations/studies, 18 were journal publications and 12 were grey literature publications. Of the 18 published articles, 12 were from low- and middle-income countries and nine were from high-income countries

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of studies.

Use of MC methodology

Fourteen of the 30 evaluations/studies reviewed used the MC approach as the only methodology whereas 16 applied a mixed methodology approach. Of the mixed method evaluations/studies, 11 used interviews to elicit information from varying respondents that included health service providers, adolescents, and opinion leaders within the community such as senior staff, six used questionnaire-based surveys, and five used focused group discussion among adolescents, young people, health service providers and other stakeholders such as teachers and local residents. There were no observable differences in methodologies used by high-income and middle- or low-income countries.

The performance of health providers and health service provision facilities were reviewed in all cases, but the types of providers and services varied. MCs were used to assess staff and services at pharmacies in 10 evaluations/studies [16–25], and health service providers at reproductive health centre/clinics in two evaluations/studies [26,27]. Nine evaluations/studies assessed services and/or service providers in mixed settings including hospitals, local health facilities, dispensaries, and NGOs [28–36], while six looked at community health facilities or clinics [37–42] with one focusing on teaching hospitals [40].

Two evaluations targeted the youth friendliness of services for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans (LGBT) population [26,43], one in a high-income and one in a low-income country. Six of the evaluations/studies aimed to assess the youth friendliness of the services and providers in their study [16,26,29,35,40,44]. Nine evaluations/studies also examined the effects of the implementation of training for service providers or youth friendliness programmes [16–18,25,28,34,42,44,45].

Key findings

Why was the MC methodology used in the evaluation/study of ASHR services?

The justification for using MCs varied among the evaluations/studies; however they can be grouped with similar explanations. The most common reason for the use of MCs was to assess/observe the interaction between service providers and patients, with particular interest in the friendliness of services, from the perspective of adolescents [16,30,35,39,40]. Another reason was to reduce or eliminate bias [13,17,18,21–25,29,33,36]. By using trained MCs, the researchers and evaluators intended to avoid observation bias or bias from the Hawthorne effect, whereby the observer could observe the subjects without their knowledge of the observation to influence their behaviour. Training helped to ensure that the mystery clients already knew what to look for in health care providers/facilities. Therefore, the evaluations/studies could use the methodology to understand factors that motivated or discouraged adolescents and young people from accessing health services.

What were the roles assigned, how were the MCs prepared, and what methods and tools helped carry out the assessment?

Roles of MC

Our review found that while some methodologies reported specific roles to be played by the MCs during health care visits, others had less formal or undefined roles.

Six of the reviewed evaluations/studies did not provide formal roles for their MCs. In these cases, MCs were asked to assess ease of access to health facilities, the environment of health facilities, staff and health provider behaviour, and service provision or specific aspects of care, such as quality of advice received [7,17,18,31,38,44]. Twenty-one of the reviewed evaluations/studies provided their MCs with specific scenarios, with either a script or a specific question or concern to ask during the medical visit [17,19,21–25,27,29,32–35]. Two of the reviewed evaluations/studies provided MCs with scripted scenarios, but failed to include information on what the scenarios or roles entailed [16,26,36].

Thirteeen of the 30 reviewed evaluations/studies, recruited both male and female adolescents or young people as MCs to assess health provider behaviour and services [16,20,25–27,32,35–37,39,41,44]. One study recruited only male MCs [45], and only one study included non-binary gendered MCs in their study design [26]. Five evaluations/studies did not specify sex of the MCs in the description of the methods [28,31,38,40,43]. Eleven of the 30 evaluations/studies reviewed did not specify the ages of the MCs recruited for the study [17,19,20,30,32,33,35,38,40,41,43], while the rest recruited individuals who were 25 years old and under [16,18,21–29,31,34,36,37,39,44,45].

Adolescent MC roles in the reviewed evaluations/studies included: (I) young females seeking pregnancy prevention or contraception/emergency contraception services [13,15–18,21–26,29,30,32,34], (II) females seeking counselling on premarital sex [29,35], (III) males seeking condoms [27,29,32,36,37,44], (IV) males and females seeking information or treatment for STIs [29,35,39], (V) or HIV testing and information [20,37,42], (VI) females requesting information about menstrual and associated problems [30], and (VII) seeking counselling for unwanted pregnancy or abortion [33,35].

Three evaluations/studies did not clearly specify the scenarios the MCs were to play [3,14,41]. The first of these stated that the MCs were to have a reproductive health complaint [14], the second stated that the MCs were to enact scenarios and did not provide further context [3], and the last trained their MCs to present critical SRH scenarios to the health care providers [41].

Training/preparation of MC

Some evaluations/studies detailed more in-depth training and support sessions than others in preparing the MCs for their roles to assess healthcare provider behaviour and service quality. Twenty-three of the reviewed evaluations/studies described a training module to prepare the MCs for their roles prior to their healthcare centre visits. Some studies included methods that provided education on SRH in addition to information on the MC roles they were to play [11,16,20,26,28,30–34,37,40,42,45]. Seven indicated that their trainings also incorporated information related to specific or general evaluation techniques [16,20,26,28,31,37,45]. One of the reviewed studies adopted preparation methods from Mystery Shopping in Sexual Health: A Toolkit for Delivery [18]. In some of the reviewed evaluations/studies, training sessions involved learning the specific scenarios MCs were expected to role play [17,21–25,27,29,35,36,39,44].

MC assessment tools

The evaluations/studies described an array of methods for data collection from the MCs’ visits. After the undercover visits, six of the evaluations/studies used questionnaires to debrief the MCs [23,28,30,32–34] and six interviewed MCs [97, 28, 37, 41, 42, 44]. Two studies utilized both interviews and questionnaires as a debriefing technique [36,39] and one study used a checklist to gather information from the MC post visit [45]. Four of the reviewed evaluations/studies described that MCs filled out observation reports [17,27,31,35] and one study had them complete a survey [16]. Other data collection methods included reflection sessions [19,26] and a rating system completed by the MCs [43]. Seven of the reviewed studies did not elaborate on the method of debriefing used [18,21,22,24,25,38,40].

Three of the reviewed evaluations/studies recorded information for data collection; in one evaluation the MCs brought digital recorders into the visit with them [29] while in the other two studies the MCs’ debrief interviews were digitally recorded [30] and filmed [28].

The reviewed evaluations/studies described a variety of data analysis techniques based on the type of data collected and the collection method. The majority of the evaluations/studies had research staff and coordinators analyse the data, while only one study specified the involvement of youth in the data analysis [27]. Five of the reviewed evaluations/studies used thematic analysis or coding [17,27,29,31,32]. Twelve of the reviewed evaluations/studies statistically analysed their quantitative data with a range of methods, such as regression analysis on platforms including SASS and Stata [19,21,22,24,25,33,34,36,42,44,45]. Four of the reviewed evaluations/studies used both statistical and thematic analysis methods [23,37,39,41]. Two employed a rating or score based analysis [35,36], and one analysed their audio-recorded MCs’ debrief manually; however, the last did not provide additional information [30]. Six studies did not include information on data analysis methods [16,18,20,26,28,38,40].

What types of healthcare facilities and cadres of health care providers were examined with MCs?

MC methodology was used in diverse settings (Tables 3 and 4) including (I) Government or public facilities (including secondary and primary health care centres), (II) private health facilities, (III) adolescent health service delivery centres, (IV) facilities run by faith-based organizations, (V) NGO facilities, (VI) FP clinics/reproductive health clinics, and (VII) private and public pharmacies.

Table 3.

Evaluations and studies in high income countries.

| Country, Publication | Objective and Setting | Methods | Role, Training, and Support of MC’s | Findings and Impressions of MC use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scotland; MacGinty and Marriot, 2014 [26] |

|

|

|

|

| UK; Council NC, 2015 [28] |

|

|

|

|

| UK; NHS, 2012 [18] |

|

|

|

|

| UK; Sykes S. and O’Sullivan K., 2006 [28] |

|

|

|

|

| USA; Sampson O et al., 2009 [19] |

|

|

|

|

| USA; Wilkinson et al., 2017 [21] |

|

|

|

|

| Australia; Hussainy et al., 2015 [22] |

|

|

|

|

| France; Delotte et al.; 2008 [23] |

|

|

|

|

| US; Wilkinson et al.; 2012 [24] |

|

|

|

|

Table 4.

Evaluations and studies in low and middle income countries.

| Country, Publication | Objective and Setting | Methods | Role, Training, and Support of MC’s | Findings and Impressions of MC use (if stated) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Africa; Geary, R. S. et al 2015 [44] |

|

|

|

|

| Tanzania; Mchome, Z. et al., 2015 [29] |

|

|

|

|

| Nigeria; Ekong, I., 2016. [30] |

|

|

|

|

| Ghana; Pathfinder International, 2005 [31] |

|

|

|

|

| Uganda; Ndyanabangi, B., & Kipp, W., 2001 [32] |

|

|

|

|

| Uganda; U. Arshad and B. Busingye, 2014 [43] |

|

|

|

|

| Uganda; Nalwadda G et al., 2011 [36] |

|

|

|

|

| Benin; Ambegaokar, MA., 2003 [17] |

|

|

|

|

| Nicaragua; Henderson, B. USAID, 2003. [20] |

|

|

|

|

| Nicaragua; Meuwissen, L. E. et al., 2006. [34] |

|

|

|

|

| Mexico; Wolfe, K., 2005 [16] |

|

|

|

|

| Mexico; Clyde, J. et al., 2013 [33] |

|

|

|

|

|

Bolivia; Belmonte, L.R. et al., 2000 [38] |

|

|

|

|

| Egypt; D. Oraby et al., 2008. [40] |

|

|

|

|

| India; Santhya, K. G. et al., 2014. [37] |

|

|

|

|

| India; A. Barua and V. Chandra-Mouli, 2016 [41] |

|

|

|

|

| Bangladesh; Sarma, H. and Oliveras, E., 2011 [45] |

|

|

|

|

| Tonga; L. Havea, 2007 [39] |

|

|

|

|

| China; Institute for Planned Parenthood Research on behalf of the China Youth Reproductive Health Project, 2005 [35] |

|

|

|

|

| South Africa; Mathews et al, 2008 [42] |

|

|

|

|

| Thailand; Ratanajamit et al., 2008 [25] |

|

|

|

|

Within these settings the evaluations/studies studied health professionals (doctors, nurses etc.), reception workers, and pharmacists.

What were the principal findings from methodology reported in the evaluations/studies?

While the principal findings of the reviewed evaluations/studies varied, key themes emerged.

Friendliness of health care facility

The majority of MCs in the evaluations/studies reported overall good experiences with friendly staff. One particular study scored the friendliness of the services in the various facilities in their evaluation as 73% [27]. Some other good practices were reported by the MCs, such as the willingness of the facilities to provide services for young people, the provision of services for LGBTQ youth [26,43] and the provision of information (although not always adequate).

Importantly, MCs also reported inappropriate behaviour or inadequate service provision that lead to poor experiences. From the 30 evaluations/studies, eight found MCs to have had issues with the lack of privacy and/or confidentiality provided by the health care providers during their visit [18,27–30,34,37,42,44]. For example, one MC expressed that,

“It wasn’t great, it wasn’t private, and you had a discussion in the open. There were other people there and it could have been really awkward… Overall it wasn’t a good experience” (Mystery Client, Nottinghamshire, England) [28].

MCs also observed structural barriers including location, opening times, and staff shortages of health facilities in eight of the reviewed evaluations/studies (26.6%) [18,19,29,31,35,37,40,43]. Staff shortages and limitations in opening times were reported to impact accessibility to services in the reviewed assessments. In the following case, a 19-year-old MC acting as an unmarried young man in a relationship with a girl and seeking condoms reported the following;

“The doctor advised me to use condoms but he told me that he wouldn’t be able to give them to me that day because the store was locked and the designated staff member was on leave.” (AFHC C, Jharkhand) [37].

In four studies, MCs described sessions with health care providers to have been rushed, as the providers did not spend an adequate amount of time with them [24,30,34,37]. They reported health care providers to be hasty or preoccupied during their visits, which impacted the focus on the MC’s needs, provide enough information, or fully and adequately answer their questions or concerns. A study in Thailand indicated that because EC is a sensitive subject in the country, it is often quickly dispensed and pharmacists do not spend time asking the necessary questions related to sexual history (49). In addition, an evaluation in Nicaragua reported that;

“More than 10% of the SPs (simulated patients) in each round felt the doctor was in a hurry to end the consult. Some felt pressured to the extent that they did not ask their question on STIs” (Nicaragua) [34].

Provider behaviour

In 14 of the reviewed evaluations/studies (46.6%), MCs experienced inappropriate or disrespectful behaviour towards them during their consultation [18,20,26–31,37–39,43,44]. Inappropriate behaviour ranged from seductive behaviour to being laughed at and not taken seriously. In most cases, the disrespectful behaviour consisted of judgmental comments made by health care providers on the inappropriateness of young people to seek SRH services. In the following case, a MC experienced judgemental comments regarding her lack of marriage status.

“… When I started to explain my need of FP methods s/he asked me twice, Family planning? So, are you married?” (Mystery Client, urban-intervention ward, Mwanza) [18]

Some of the reviewed evaluations/studies described differences in provider behaviour and attitudes based on gender of MCs. Some reported that male MCs were more likely to report services as satisfactory compared to female MCs [32,38,44]. The female MCs in these evaluations/studies tended to report attitudes and behaviours that were inappropriate and affected their experience at the facilities they visited. For example;

“…in two cases, physicians tried to seduce the (female) mystery clients. Other inappropriate behaviour included aggressive tactics and inappropriate intimacy used by the providers” (Bolivia) [38].

One study reported findings that differed from this pattern, stating that young male clients face more difficulties when seeking contraceptive services in rural Uganda [36]. Ultimately, although most of the evaluations/studies did not clearly state differences between the male and female MCs’ satisfaction with services, it appears that female MCs reported more hostile attitudes from the service providers than males.

Additionally, two evaluations/studies mentioned lack of decision autonomy to be problematic during MC sessions [33,34]. In these cases, the health care provider made decisions for patients without consulting their opinion:

‘She said I should take the injection and that we shouldn’t go into the other methods. When I asked why she recommends the injection she asked how old I am and said that they don’t recommend pills for young people because they are careless…’ (Simulated Client 5 (female), Clinic 3 – YFS, Benin) [17].

In another study, when the MCs were accompanied, decision making autonomy was restricted because health care providers did not offer the adolescent an opportunity to talk without the accompanying person [33]. The authors of this study link this to the fact that a portion of the adolescents ‘ended up with a decision about abortion that they did not initially prefer’ [33].

Information availability

Availability of information and quality of available information was a concern in many of the evaluations/studies. This included information from verbal communication during sessions with health care providers and/or information in printed format, such as posters or pamphlets. Fourteen of the reviewed evaluations/studies (46.6%) indicated that MCs found the information provided by the health care providers to be insufficient [2,5,6,13,17,20,23,26–31,33,36,37] The following quotes, from studies in Uganda, Mexico, and Nicaragua, indicate examples of lack of quality information provided;

“…none of the organizations visited had tailor-made targeted information, education and communication (IEC) materials for YMSM and LGBTQ youth” (Uganda) [36].

“…there were cases in which professionals either gave incorrect information (stated that the procedure had to be surgical because the girl was an adolescent or said that the reason an accompanying adult was required was because the procedure was very risky) or made specific judgmental statements that appeared related to the adolescent’s age” (Mexico City) [33].

“Pharmacies tended not to display written or visual information, and few had fliers or other written materials to take away” (Nicaragua) [20].

What were the overall perceptions of the use of MCs in assessing health care provider and facility performance?

Generally, the MC methodology was perceived to be a useful method in evaluating service delivery and provider behaviour. Twelve of the 30 evaluations/studies explicitly stated perceptions or observations on the use of adolescent MCs in evaluating health provider behaviour and service provision [17,20,28,29,31–34,37,39,41,42] Of these, three regarded MCs as being a good method for providing insightful and unique feedback [28,32,39] and six indicated that the use of MCs was successful in assessing services and providers [20,29,31,34,37,42].

Additionally, one study discovered that MCs accompanied by adults received more information than those that were unaccompanied [33]. Similarly, in one study adult physicians received correct information and more attention from pharmacists when calling in regard to adolescents’ access to EC than the adolescents themselves [24]. Also, in instances when services were refused, MCs had reported at the facilities with SRH service needs, whereas the actual adolescent clients presented with general medical issues [41].

The reviewed evaluations/studies pointed to the need to invest effort in training and preparing the MC. This was seen as crucial to the success of the evaluation or research study [20,39] Other evaluations/studies found the MC method to be a quick way to receive feedback, critical for improving services, and that the conclusions from these evaluations/studies could be extrapolated to the general population because the MCs’ experiences represented actual treatment of adolescents within the healthcare delivery system.

Discussion

Overall, the reviewed evaluations/studies indicate that the MC methodology is widely used and valuable in the examination of health facilities and health care providers. First, we found that the reviewed evaluations/studies used the MC methodology, either alone or in combination with other methods, to obtain a youth observatory perspective of how the health facility or health care provider responded to providing SRH needs to adolescents. Secondly, in some evaluations/studies, the roles of the adolescent MCs were well defined, while others only provided limited detail. Also, some evaluations/studies described greater preparations such as training, carefully detailing scenarios, and role playing. Thirdly, the methodology was used to examine adolescent health service provision in public and private hospitals, NGO supported facilities, formal and informal settings, and pharmacies. The cadre of health care providers evaluated or studied with MCs varied and included health workers (doctors, nurses, etc.), pharmacists, and reception workers. Finally, MCs requested a variety of information on testing and treatment of HIV/STIs, menstruation issues, abortion services/options, unwanted pregnancies, contraceptive services, and other SRH issues. To conclude, this review confirms that while adolescents in high-, middle-, and low-income countries tend to have positive experiences in SRH services, they sometimes experience judgmental and disrespectful behaviour from health care providers or inaccurate/insufficient information from them and find that ASRH services may not be organized to their needs and preferences.

Despite concerns that the methodology limits the type of information collected, considering that MCs do not undergo any form of medical examination or procedure, researchers are still able to draw valuable information from MCs’ experiences regarding facility performance and provider behaviour. By using mixed methodology and properly trained MC participants, it is possible to increase reliability and address some of the pitfalls of the methodology and provide additional insight into areas of interest [1,35,39,46]. Most of the evaluations/studies reported debriefing the MCs immediately after their visits to avoid recall bias. Each report indicated different methods to debrief MCs, but all debriefs were carried out immediately after the visits. Although previous studies have regarded MCs as more effective in monitoring, compared to evaluation [1,39], the reports included in this review prove otherwise with insights into how the method can be used and adapted to suit the purpose of the evaluation. Although we cannot say that this methodology is better than other qualitative methods, as there was no comparison of methods, we can draw from the experiences of the researchers and evaluators who found it effective in providing a glimpse of information on health facilities and health care provider behaviour. Two key advantages of the MC methodology include its potential for quick feedback, and its association with reduced incidence of bias, such as observer bias and bias from Hawthorne’s effect.

The evaluations/studies in this review describe similar findings to other evaluations/studies that have reported on health care provider behaviour and SRH facilities and services with different methods. Gonsalves and Hindin’s review confirms that both pharmacists and young people are concerned about access to SRH services and recognise that regulations can increase barriers to this access [4]. Our review also aligns with a recent review addressing the barriers that adolescents face in accessing STI services; behaviour was found to be satisfactory for the most part, but included instances of inappropriate and disrespectful conduct towards adolescents [47]. Newton-Levinson et al.’s review also suggests that there might be differences in the attitudes of health care providers depending on gender of the patient/client and that female adolescents may perceive female health care providers as being friendlier than male health care providers [47]. Similarly, an article addressing adolescent SRH needs from an evaluation in Uganda reveals that SRH services sometimes do not provide a safe environment for adolescents to discuss sensitive issues and that this affects the patients’ ability to feel comfortable to fully disclose concerns and issues [48]. Our review of the MC methodology with adolescents provides more depth on SRH services from their unique perspective. The review indicates that in addition to the lack of assured privacy and confidentiality, the timing constraints of services, recurrent staff shortages, and unexpected costs of services or commodities are key barriers to adolescents’ access to SRH services. Further, the MC methodology is as good a method for M&E because it identifies both strengths and weaknesses of health service delivery and provides the unique perspective of the MCs, the people for whom the service is designed.

The results and experiences of the MC methodology with adults and in the business sector [5–8] are similar to the results of our review regarding adolescents in the health sector, and thus add support to the value of this method. For example, in an evaluation study by Friedman et al., MCs were trained to assess provider practices and evaluate the use of mobile phone messages to pharmacists to improve the treatment of childhood diarrhoea in Ghana [49]. The study found disparities between actual practices of the providers and their self-reported practices. Outside the field of health, the MC method has evaluated the quality and quantity of information provided by the staff of financial institutions in Ghana, Mexico, and Peru [8]. The study found that clients were not offered enough information to compare credit and savings products [8], similar to the result in which we found that adolescents were not offered enough information to compare contraception methods [17]. The efficacy of the MC method in ASRH service provision is supported by the success of these studies and the similarities in results and experiences.

The MCs in our reviewed evaluations/studies reported positive experiences, similar to the perceptions of adolescents involved in other participatory research methods. For example, in Nigeria, adolescents used the photovoice technique, which involves taking photos of issues within their communities to then critically discuss, and reported that they enjoyed the experience and would be willing to participate in future research evaluations/studies [50]. The MC methodology provides an opportunity for the clients to be engaged in their own care and services. In some cases, MCs also receive training in other areas such as evaluation techniques and receive education on SRH issues. Furthermore, we can draw from the reports and comments of the MCs and suggest that they would share their knowledge and experiences with their peers. The positive response to the MC methodology, from adolescents themselves, contributes to the merit of the methodology.

Despite the expansive search undertaken in the review, some evaluations/studies may have been missed. Our findings are limited by our criteria, that excluded reports not published in English or Spanish and our inability to find similar reviews in the Spanish language which impacted the geographical distribution of evaluations/studies. No quality assessment was undertaken, which limits our ability to assess and integrate those quality evaluations into our findings. Some of the evaluations/studies used very few MCs or examined a small array of healthcare providers and services, which could impact their findings. Furthermore, several evaluations/studies were unclear or did not include information on several components of their study, making it difficult to accurately synthesise findings. The evaluations/studies that used multiple evaluation techniques in evaluating provider behaviour and service provision did not directly compare MCs outcomes to those of other forms, which limits our ability to understand the extent to which the MC assessment was effective, compared to other methods. The review did, however, cover a breadth of research designs in a variety of settings, allowing for a comprehensive analysis.

Conclusion

The use of MC methodology with adolescents provides an opportunity for researchers and evaluators to understand how health care providers and health facilities perform when they do not know they are under review. It is a useful M&E method that allows for quick feedback to identify how to improve the quality of ASRH services. The use of adolescent MCs, in particular, aligns with the call for the participation of young people in programme and policy development [6] and the need to champion adolescents’ SRH rights. The findings of this review could help inform the decisions that policy makers and programme developers make by improving their understanding of the SRH needs of adolescents. The successful and effective participation of adolescents and young people as MCs demonstrates their ability to actively participate in information gathering and research analysis for work that will ultimately benefit them. When given the chance, young people can be more than just subjects in research or evaluations, and instead become meaningful participants.

Biography

VC conceived the paper. VC and SC did a preliminary scoping of the area. CL then built on this and prepared the first draft with support from VC. EA, IL, LG, and SC provided feedback on the first draft. CL and VC collated the feedback, performed additional literature reviews, and prepared revised drafts. All the authors read and approved the final draft.

Responsible Editor Jennifer Stewart Williams, Umeå University, Sweden

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the UNDP-UNFPA-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), a cosponsored programme executed by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Paper context

Mystery client (MC) methodology is a form of participatory research for evaluating the performance of health care providers or facilities from the perspective of service users. Until this review, there were no systematic reviews on the use of MCs in adolescent sexual and reproductive health (ASRH) research and monitoring and evaluation of programmes. This review highlights the usefulness of MC methodology to gain insight, from an adolescent perspective, on the quality of ASRH services.

References

- [1]. Marie Stopes International Monitoring quality of care through mystery client surveys: guidelines. Marie Stopes International. 2016. Available from: http://m4mgmt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/quality-Monitoring-Quality-of-Care-Through-Mystery-Client-Surveys_MSIGlobal.pdf

- [2]. Huntington D, Lettenmaier C, Obeng-Quaidoo I.. User’s perspective of counseling training in Ghana: the “mystery client” trial. TT - Stud Fam Plann. 1990;21:171–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Maynard-Tucker G. Indigenous perceptions and quality of care of family planning services in Haiti. Health Policy Plan. 1994;9:306–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Gonsalves L, Hindin MJ. Pharmacy provision of sexual and reproductive health commodities to young people: a systematic literature review and synthesis of the evidence. Contraception. 2017;95:339–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Bate R, Mooney L, Hess K. Medicine registration and medicine quality: a preliminary analysis of key cities in emerging markets. Res Rep Trop Med. 2010;1:89–93. Available from http://ssrn.com/abstract=2341961 [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Currie J, Lin W, Zhang W. Patient knowledge and antibiotic abuse: evidence from an audit study in China. J Health Econ. 2011;30:933–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Kwanya T, Stilwell C, Underwood PG. A competency index for research librarians in Kenya. African J Libr Arch Inf Sci. 2012;22:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Giné X, Mazer RK. Financial (Dis-) information evidence from an audit study in Mexico. Policy Res Work Pap WPS7750. 2014. June 27 Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/565401468123255247/pdf/WPS6902.pdf%5Cnhttp://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/869451468937960883/pdf/WPS7750.pdf

- [9]. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Ollner AA. Guide to the literature on participatory research with youth. The Assets Coming Together for Youth Project Strategies. 2010. Available from: http://www.yorku.ca/act/

- [11]. Bergold J, Stefan T. Participatory research methods: a methodological approach in motion. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2012;13:Art.1. [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Villa-Torres L, Svanemyr J. Ensuring youth’s right to participation and promotion of youth leadership in the development of sexual and reproductive health policies and programs. J Adolesc Heal. 2015;56:S51–7. Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Madden JM, Quick JD, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Undercover careseekers: simulated clients in the study of health provider behavior in developing countries. Soc Sci Md. 1997;45:1465–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Cornwall A, Jewkes R. What is participatory research? Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:1667–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Baraitser P, Pearce V, Walsh N, et al. Look who’s taking notes in your clinic: mystery shoppers as evaluators in sexual health services. Heal Expect. 2008;11:54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Wolfe K. Youth Friendly Pharmacies and Partnerships : the Cms-Celsam Experience. 2005.

- [17]. Ambegaokar M, Capo-Chichi V, Sebikali B, et al. Assessing the performance of pharmacy agents in counselling family planning users and providing the pill in Benin: an evaluation of Intrah/PRIME and PSI training assistance to the Benin social marketing program. 2003.

- [18]. NHS South East London Evaluation of Oral Contraception in Community Pharmacy Pilot in Southwark and Lambeth: Final Evaluation Report. 2012. Available from: http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/main-content/-/article_display_list/13820810/pharmacies-should-offer-under-16s-direct-access-to-contraceptive-pill-says-nhs-report

- [19]. Sampson O, Navarro SK, Khan A, et al. Barriers to adolescents’ getting emergency contraception through pharmacy access in California: differences by language and region. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;41:110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Henderson B. Adolescent-friendly pharmacies: mystery clients assess contraceptive services for youth. PRIME II Proj USAID. 2003. Available from: http://www.prime2.org/prime2/pdf/PP_NIC_1_hi_res.pdf

- [21]. Wilkinson TA, Clark P, Raffie S, et al. Access to emergency contraception after removal of age restrictions. Pediatrics. 2017;140:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Hussainy SY, Stewart K, Pham MP. A mystery caller evaluation of emergency contraception supply practices in community pharmacies in Victoria, Australia. Aust J Prim Health. 2015;21:310–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Delotte J, Molinard C, Trastour C, et al. Delivery of emergency contraception to minors in French pharmacies. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2008;36:63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Wilkinson TA, Fahey N, Shields C, et al. Pharmacy communication to adolescents and their physicians regarding access to emergency contraception. Pediatrics. 2012;29:624–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Ratanajamit C, Chongsuvivatwong GA, Geater AFA. randomized controlled educational intervention on emergency contraception among drugstore personnel in southern Thailand. Jamwa. 2002;57:196–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. MacGinty D, Marriott A. LGBT Youth Scotland: Mystery Shopper Project. 2014; Available from: https://www.lgbtyouth.org.uk/files/documents/3Mystery_Shopper_Project_Young_Persons_Report_2014.pdf

- [27]. Sykes S, O’Sullivan KA. “mystery shopper” project to evaluate sexual health and contraceptive services for young people in Croydon. J Fam Plan Reprod Heal Care. 2006;32:25–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Council NC How Young People Friendly are our Health Services? Nottinghamshire Mystery Shopper Report 2015.

- [29]. Mchome Z, Richards E, Nnko S, et al. A “mystery client” evaluation of adolescent sexual and reproductive health services in health facilities from two regions in Tanzania. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Ekong I. Adequacy of adolescent healthcare services available for adolescent girls in a Southern Nigerian environment. Int Res J Med Biomed Sci. 2016;1:23–28. Available from 10.15739/irjmbs.16.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Pathfinder International ; African youth alliance. Youth-friendly services: Ghana end of program evaluation report. Watertown, Massachusetts: Pathfinder International; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Ndyanabangi B, Kipp W. reproductive health and adolescent school students in Kabarole district, western Uganda: A qualitative study. World Heal Popul. 2001;3:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Clyde J, Bain J, Castagnaro K, et al. Evolving capacity and decision-making in practice: adolescents’ access to legal abortion services in Mexico city. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21:167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Meuwissen LE, Gorter AC, Kester ADM, et al. Does a competitive voucher program for adolescents improve the quality of reproductive health care? A simulated patient study in Nicaragua. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:204 Available from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med5&NEWS=N&AN=16893463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. PATH Evaluation of Youth Friendly Services in Shanghai. 2005.

- [36]. Nalwadda G, Tumwesigye NM, Faxelid E, et al. Quality of care in contraceptive services provided to young people in two Ugandan districts: A simulated client study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Santhya KG, Prakash R, Jejeebhoy SJ, et al. Accessing adolescent friendly health clinics in India: the perspectives of adolescents and youth. Reprod Health. 2014;7:12. [Google Scholar]

- [38]. de Belmonte LR, Gutierrez EZ, Magnani R, et al. Barriers to adolescents’ use of reproductive health services in three Bolivian cities. Washington: Focus on Young Adults/Pathfinder International; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Havea L. Exploring Factors to Strengthen Existing Reproductive Health Services for Young People in Tonga. 2007. Available from: http://countryoffice.unfpa.org/pacific/drive/RHforTonga.pdf

- [40]. Oraby D, Soliman C, Elkamhawi S, et al. Assessment of youth friendly clinics in teaching hospitals in Egypt. Fam Heal Int Assess Rep. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Barua A, Chandra-Mouli V. The tarunya project’s efforts to improve the quality of adolescent reproductive and sexual health services in Jharkhand state, India: a post-hoc evaluation. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016;29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Mathews C, Guttmacher S, Flisher J, et al. The quality of HIV testing services for adolescents in Cape Town, South Africa: do adolescent-friendly services make a difference? J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:188–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Arshad U, Busingye B. Findings: mystery client research on services available to young men who have sex with men (YMSM) and lesbian gay bisexual and transgender, questioning youth (LGBTQ) youth in Kampala district, Uganda. 20th Int AIDS Conf 2014. July 20-25, Melbourne: Australia; 2014:8960 [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Geary RS, Webb EL, Clarke L, et al. Evaluating youth-friendly health services: young people’s perspectives from a simulated client study in urban South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Sarma H, Oliveras E. Improving STI counselling services of non-formal providers in Bangladesh: testing an alternative strategy. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87:476–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Boyce C, Neale P. USING MYSTERY CLIENTS: a guide to using mystery clients. Pathfind Int Tool Ser. 2006;3:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- [47]. Newton-Levinson A, Leichliter JS, Chandra-Mouli V. Sexually transmitted infection services for adolescents and youth in low- and middle-income countries: perceived and experienced barriers to accessing care. J Adolesc Heal. 2016;59:7–16. Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Atuyambe LM, Kibira SPS, Bukenya J, et al. Understanding sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents: evidence from a formative evaluation in Wakiso district, Uganda. Reprod Health. 2015;12:35 Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25896066%5Cnhttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC4416389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49]. Friedman W, Woodman B, Chatterji M. Can mobile phone messages to drug sellers improve treatment of childhood diarrhoea?–A randomized controlled trial in Ghana. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30:i82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Olumide AO, Adebayo ES, Ojengbede OA. Using photovoice in adolescent health research: a case-study of the well-being of adolescents in vulnerable environments (WAVE) study in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016;30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]