Abstract

CONTEXT:

In recent years, the media have had very massive effects on individuals, especially children and adolescents. Hence, they should be able to use media rationally also be able to create digital, multimedia texts, and attain media literacy. Media literacy is a skill based on understanding and gives the audience the opportunity to use the media appropriately and critically.

AIMS:

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between media literacy and mental psychology of high school students in Semirom city.

SETTINGS AND DESIGN:

This correlational study was conducted with the participation of 139 adolescent girls selected using multi-stage random sampling, in Semirom city, Isfahan province, the Central of Iran, in 2017.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS:

Data were measured using researcher-made media literacy questionnaire, psychological well-being Scales of Ryff.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS USED:

Data were analyzed using SPSS software and descriptive statistics (Pearson correlations) were used. The statistical significant level was set as 0.05.

RESULTS:

There was no significant correlation between family economic situation, parental education, and media literacy score. Media literacy was significantly correlated with total psychological well-being (r = 0.165, P < 0.05), personal growth subscale (r = 0.216, P < 0.05), and self-acceptance subscale (r = 0.218, P < 0.05).

CONCLUSIONS:

Considering the importance of psychological well-being in adolescents' life, the design of educational interventions to increase media literacy is recommended.

Keywords: Adolescent, child, media literacy, psychological well-being, Semirom city

Introduction

Recently, there has been fast growth in the use of communication technology such as mobile phones and Internet, and the media has become a vital part of everyday life.[1] Various researches reveal that individuals spend a lot of time with the media. Hence, media deliver all types of messages that are designed by their own publishing policy and ideology to individuals with different characteristics.[2] In this situation, media have an immense effect on individuals, especially children and adolescents since they widely use the internet to explore their worlds, mobile phones, video games, etc.[3]

Previous studies about the impact of media on adolescents and children confirmed undesirable effects on their well-being and health such as risky sexual behavior, aggressive behavior, substance use, and eating disorder.[4] Media affect adolescents and children not only by relocating the time they spend doing schoolwork, studying or sleeping but also by manipulating attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.[5]

Furthermore, the importance and necessity of media literacy among children and adolescents is much higher because first, childhood is the pillar of socialization and identity in the human body. Second, children and adolescents who are the main media audience, have little power in choosing, selecting, processing, and analyzing information and news. Hence, the lack of media literacy training for children and adolescents will result in a lack of proper identity formation.[3]

In spite of the evidence of probable harmful effects, there is also evidence that media can be useful for children and adolescents, by raising their early literacy skills through educational programming.[6] Media can be used to connect with each other on schoolwork and group tasks, staying connected with family and friends, making new friends, exchanging ideas and sharing pictures, accessing health information.[5]

Therefore to effectively participate in the modern-day interconnected world, children and adolescents should attain media literacy; they should be capable of rational use of media and create digital, multimedia texts.[3]

Media literacy is a kind of skill-based understanding that can be used to distinguish between different types of media as well as media productions.[7] Media literacy components are as follows: ability to speak and listen, read and write, access new technologies, and produce their own messages with a critical point of view.[2] Media literacy gives children and adolescent a deep understanding of what is happening in the media space.[3] The main aim of media literacy is to make children and adolescents critically and appropriately literate in all types of media, and hence that the media does not control what they see and hear, rather they are the ones to control it. As mentioned media in addition to desirable effects, have adverse effects, such as highly aggressive behavior, the promotion of utopian ideals and groups, stereotyped thoughts, and inappropriate sexual behaviors[4] that have a direct impact on children and adolescents mental health.

According to the various studies, the issue of mental health or psychological well-being is regarded as an imperative facet of health, especially in children and adolescents.[8]

While numerous studies have been conducted on media literacy among children and adolescents in other counties,[9] only a few studies in this field has been conducted in Iran, and most of them focused on the necessity and importance of media literacy and its relationship in the importance of psychological well-being in adolescents. However, this study was conducted to evaluate the relationship between media literacy and psychological well-being in female adolescents in Semirom city.

Subjects and Methods

This correlational study was conducted on female adolescents in Semirom city, Isfahan province, the Central of Iran, in 2017. The sample was selected using multi-stage random sampling method.

The sample size was determined based on the confidence interval (95%) and test capability (80%) according to a similar study.[7] Initially, three female high schools in Semirom city were selected randomly. After coordinating with the principals of selected schools, 50 students were chosen by random table number from each school. They were invited to participate in the study and were evaluated for inclusion. They should (a) have Internet access and smartphone (b) be interested in participation. They were excluded if they had filled out the questionnaire incompletely.

Two students had no internet access. All participants gave their consent before taking part in this study. Then, questionnaires were distributed among the participants. A total of 139 participants were enrolled in the study and the return rate was 92.6% which was satisfactory.

Demographic and media literacy and psychological well-being data were measured through three self-report questionnaires:

Demographic questionnaire was a researcher-made questionnaire which consists of items about age, parent's education, parent's job, student perception of the economic situation of the family, and number of siblings

Media literacy questionnaire was a researcher-made questionnaire which consists of 67 items; all items have to be answered on the five-point Likert scale (1 = completely agree, 2 = agree, 3 = not agree not disagree, 4 = disagree, and 5 = totally disagree). Scores can range from 67 to 268, with higher scores demonstrating greater media literacy. For the sake of ease in comparison, scores were set of 100.

The content validity of the media literacy questionnaire was assessed using a panel of experts consisting 10 experts in health education and psychology, and their corrective comments were applied to the questionnaire. The reliability of the questionnaire was also measured using Alpha Cronbach's method. The alpha coefficient 0.936 was obtained.

-

3.

Psychological well-being scales of Ryff, is a standard and well-known scale which has 18 items and six subscales including: (a) self-acceptance, (b) positive relation with other, (c) autonomy, (d) environment mastery, (e) personal growth, and (f) purpose in life.[10]

All items have to be answered on six-point Likert scale. The higher scores in this scale point to higher psychological well-being and vice versa.

This scale was transformed into Persian by previous studies and its cultural adaptation, reliability, as well as its validity, were confirmed.[10] In the present study, the reliability of the scale was also measured using Alpha Cronbach's method. The alpha coefficient of self-acceptance, positive relation with others, purpose in life, environmental mastery, personal growth, autonomy, were 0.93,0.91,0.90,0.90,0.87, and 0.86, respectively, and for the whole scale, it was 0.89.

The Research Ethics Sub-committee of the Isfahan Medical University had approved this study. Consent was obtained from all participants.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 0.20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and by descriptive statistics. Pearson correlations were used to explore relationships between the psychological well-being and media literacy. The statistical significant level was set as 0.05.

Results

In this study, 139 adolescent girls had participated. Their age ranged from 13 to 15 with a mean of 14.01 ± 0.8 years and the average number of family members was 4.6 ± 1.04.

Forty-six girls were the only children in the family. Most fathers (32.4%) and mothers (33.1%) had a high school diploma. Most of the mothers (82%) were housewives.

Eighteen percent of students considered their family's economic situation as undesirable, 46.8% as medium, 33.8% as fine, and 1.4% as desirable.

Average media literacy score was 50.2 ± 13.2 from 100.

Eleven and a half percent of the participants had weak media literacy, 74.8% medium media literacy, and 13.7% had favorable media literacy level.

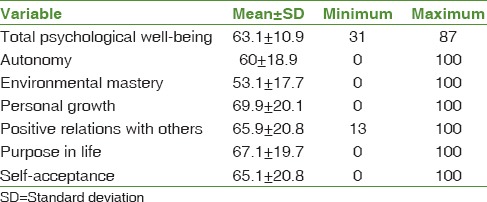

The psychological well-being scores are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Total score of student's psychological well-being and its subscales (equal to 100)

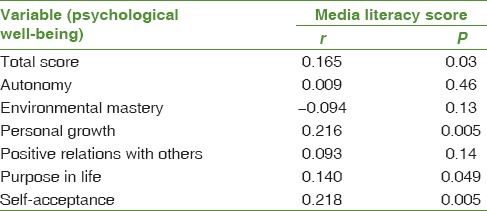

The correlation between media literacy and total psychological well-being and its subscales scores are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Statistical indexes of Pearson correlation between media literacy score and student's psychological well-being score and its subscales

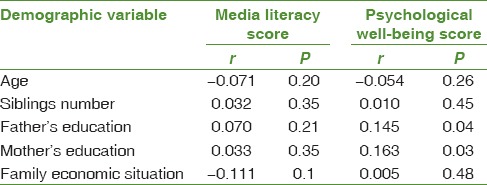

The correlation between the media literacy and the total psychological well-being scores with demographic variables is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The correlation between media literacy and total psychological well-being score with student's age, parent's education, student perception of the economic situation of the family, siblings number

One-way ANOVA showed that there was no significant relationship between media literacy and psychological well-being scores with students' parent job (P > 0.05).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the relationship between psychological well-being and media literacy among female high school students in Semirom city. A total of 139 students participated in the study, the mean score of media literacy was 50.2 ± 13.2 from 100, which was not desirable, and was consisted with previous studies.[11]

In contrast to this finding, in the study conducted by Ashrafi Rizi, the mean score of media literacy among university students was higher than moderate and relatively favorable.[12] Furthermore, results of Pounaki et al. study showed that media literacy of university students was appropriate.[7] This contradiction maybe due to different age and education of participants.

The results revealed that there was no significant correlation between family economic situation and media literacy score. Probably, the reason for this is that nowadays students in most families, even low-income families have access to different kind of media.

Contrary to the current study, in Pounaki et al. research those who were in wealthy families had higher media literacy score.[7] As well in the present study, contrary to the Pounaki study, there was no significant correlation between parental education and media literacy score.

The most likely reason is that in our study, most of the parents had the same education (diploma). To better investigate the relationship between parents' education and student's media literacy, samples with different levels of parent's education are needed.

The findings indicated that the mean of total psychological well-being score was 63.1 ± 10.9 from 100.

In Yasmin's study conducted with adolescents aged 12–18 years in Pakistan, the mean of total psychological well-being score was 69.6 ± 14.91.[13] The comparison psychological well-being subscales showed that the highest mean score was related to personal growth subscales, and the lowest was related to the environmental mastery subscales.

In the Emadpoor et al. research, the highest mean scores were in self-acceptance, positive relations with others subscales and the lowest was related to the autonomy subscale.[14] Considering the characteristics of adolescents, these findings were expected.

Consistent with previous studies,[4,6] the present study reveals that there exists a low level of positive relationship between media literacy score and total psychological well-being (r = 0.165). In other words, the efforts to improve adolescent's media literacy may ultimately increase the psychological well-being.

Previous research results confirmed that adolescents who have a poor mentality tend to rely on internet usage, thus, the higher the internet use, worse the mental health.[15] Furthermore, Walther's study shows that media literacy intervention can influence adolescents' media use behavior as well as computer gaming.[16]

In the present study of comparison in psychological well-being subscales showed that there was a medium level positive relationship between media literacy score and personal growth subscale (r = 0.216) and self-acceptance subscale (r = 0.218).

To explain the relationship between the field of personal growth and media literacy, it can be said that recently, continuous learning and the ability to analyze information and to identify the correct information from the wrong ones are needed for personal growth and progress, which is one of the most important components of media literacy skills.[2]

In case of self-acceptance and media, the greatest focus is on appearance concerns such as body-image, body dissatisfaction.

However, recent studies constantly reveals a relationship between media contact and body dissatisfaction,[9] a qualitative study of body image and influence of social media over adolescent female revealed that high media literacy is one of factors that can mitigate probable adverse relationship among body image and social media exposure.[17] Furthermore, media provides idealistic advertising in various fields with different channels; Individuals with higher levels of media literacy are able to understand these media tweaks and have more confidence and self-esteem.

This research was only conducted in in Semirom city adolescent girls, precaution should be taken for generalizing and interpreting the results to other group of adolescents.

It is better to examine the correlation between media literacy and psychological well-being in both sexes through diverse sample groups and different measurement tools and methods in future studies.

Conclusions

The purpose of media literacy is to help adolescents protect themselves from the potentially negative effects. Findings of this study indicate that there is a direct relationship between media literacy and psychological well-being. Considering the importance of mental health in adolescents' life, the design of educational interventions related to media literacy is suggested; therefore, the media literacy helps the adolescent audience to better interpret the surrounding environment.

Limitations

This research was confined to the adolescent girls in Semirom city only; therefore, precaution should be taken for generalizing and interpreting the results to other group of adolescents.

It is better to examine the correlation between media literacy and psychological well-being in both sexes through diverse sample groups and different measurement tools and methods in the future studies.

Financial support and sponsorship

The present study was sponsored by the research deputy of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The present study has been based on a Master's thesis in Health Education submitted to the School of Health at IUMS (code: 395646). The authors hereby express their gratitude to the Vice-Chancellor for Research at IUMS and the education authority in Semirom city and all students who participated are highly appreciated.

References

- 1.Mazaheri MA, Karbasi M. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of mobile phone addiction scale. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19:139–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasap F, Gürçınar P. Social exclusion of life in the written media of the disabilities: The importance of media literacy and education. Qual Quant. 2017;1:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner KH, Jolls T, Hagerman MS, O'Byrne W, Hicks T, Eisenstock B, et al. Developing digital and media literacies in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140:S122–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1758P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strasburger VC, Jordan AB, Donnerstein E. Health effects of media on children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;125:756–67. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K, Council on Communications and Media. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics. 2011;127:800–4. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linebarger DH, Walker D. Infants' and tod-dlers' television viewing and language out-comes. Am Behav Sci. 2005;48:624–45. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pounaki EE, Givi MR, Fahimnia F. Investigate the relation between the media literacy and information literacy of students of communication science and information science and knowledge. Iran J Inf Process Manag. 2017;32:581–604. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmedbookani S. Psychological well-being and parenting styles as predictors of mental health among students: Implication for health promotion. Inter J Pediatr. 2014;2:39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fardouly J, Pinkus RT, Vartanian LR. The impact of appearance comparisons made through social media, traditional media, and in person in women's everyday lives. Body Image. 2017;20:31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khanjani M, Shahidi S, Fath-Abadi J, Mazaheri M, Shokri O. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Ryff's scale of psychological well-being, short form (18-item) among male and female students. Thought Behav Clin Psychol. 2014;8:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLean SA, Wertheim EH, Masters J, Paxton SJ. A pilot evaluation of a social media literacy intervention to reduce risk factors for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50:847–51. doi: 10.1002/eat.22708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashrafi-Rizi H, Ramezani A, Koupaei HA, Kazempour Z. The amount of media and information literacy among Isfahan University of medical sciences' students using Iranian media and information literacy questionnaire (IMILQ) Acta Inform Med. 2014;22:393–7. doi: 10.5455/aim.2014.22.393-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan Y, Taghdisi MH, Nourijelyani K. Psychological well-being (PWB) of school adolescents aged 12-18 yr, its correlation with general levels of physical activity (PA) and socio-demographic factors in Gilgit, Pakistan. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:804–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emadpoor L, Lavasani MG, Shahcheraghi SM. Relationship between perceived social support and psychological well-being among students based on mediating role of academic motivation. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2016;14:284–90. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi M, Park S, Cha S. Relationships of mental health and internet use in Korean adolescents. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017;31:566–71. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walther B, Hanewinkel R, Morgenstern M. Effects of a brief school-based media literacy intervention on digital media use in adolescents: Cluster randomized controlled trial. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17:616–23. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burnette CB, Kwitowski MA, Mazzeo SE. “I don't need people to tell me I'm pretty on social media:” A qualitative study of social media and body image in early adolescent girls. Body Image. 2017;23:114–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]