Abstract

Background:

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of weight loss with hypocaloric diet and orlistat treatment in addition to hypocaloric diet on gut-derived hormones ghrelin and obestatin.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 52, euglycemic and euthyroid, obese female patients were involved in the study. The patients were assigned to two groups: Group 1 (n = 26) received hypocaloric diet alone and Group 2 (n = 26) received orlistat in addition to hypocaloric diet for 12 weeks. Anthropometric measurements, serum lipid, insulin levels, and obestatin and ghrelin values were assessed at the beginning of the study and after 12 weeks of therapy.

Results:

Baseline clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters including serum ghrelin and obestatin concentrations and ghrelin/obestatin ratio were similar between the two groups. After 12 weeks, mean change in BMI, fat mass, and fat-free mass (FFM) were −1.97 ± 1.56 kg/m2 (P = 0.003), −2.63% ±2.11% (P = 0.003), and −1.06 ± 0.82 kg (P = 0.003), respectively, in Group 1. In Group 2, mean change in BMI was −2.11 ± 1.24 kg/m2 (P = 0.001), fat mass was −3.09% ±2.28% (P = 0.002), and FFM was −1.26 ± 0.54 kg (P = 0.001). However, fasting glucose, lipid, and insulin levels did not change in Group 1. Furthermore, except serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglyceride levels, no significant change was observed in Group 2. Although serum ghrelin and obestatin concentrations increased significantly in both groups (Group 1: pGhrelin: 0.047, pobestatin: 0.001 and Group 2: pGhrelin: 0.028, pobestatin: 0.006), ghrelin/obestatin ratio did not change significantly. When the changes in anthropometric assessments and laboratory parameters were compared, no significant difference was observed between the two groups. Furthermore, no correlation was observed between ghrelin or obestatin and any other hormonal and metabolic parameters.

Conclusion:

Weight loss with diet and diet plus orlistat is both associated with increased ghrelin and obestatin concentrations.

Keywords: Obesity, obestatin/ghrelin ratio, orlistat

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a main health-care problem of the new century that is associated with coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease. The World Health Organization reported that more than 1 billion adults were overweight, and at least 300 million of them were obese.[1] Most importantly, obesity is associated with an increased risk of developing diabetes, hypertension, osteoarthritis, coronary artery disease, and cancer.[2,3,4,5] Calorie restriction and regular physical activity are still the mainstay of treatment in obesity; nevertheless, these methods solely generally do not provide successful outcomes.[6,7] Therefore, pharmacological treatment options are often used in weight reduction programs in addition to dietary restriction and lifestyle adjustment. Pharmacologic treatment options include orlistat, lorcaserin, combination phentermine-topiramate, phentermine, benzphetamine, phendimetrazine, diethylpropion, and liraglutide. In our country, only orlistat is approved by the ministry of health for the pharmacologic treatment of obesity. Orlistat is an inhibitor of the gastrointestinal lipase that decreases the absorption of fat by 30%, and it has a long-term safety record.[8,9] Previous reports have confirmed the potency of orlistat in weight reduction, along with amelioration in cardiovascular risk factors in obese patients.[10]

Gut-derived hormones ghrelin and obestatin have been described as an important physiologic regulator of appetite and energy homeostasis recently. Ghrelin is an endogenous ligand for the growth hormone (GH) secretagogue receptor, and it regulates energy homeostasis and appetite and consequently increases body weight.[11] Whereas exogenous ghrelin administration stimulated appetite and food intake, recent studies reported decreased ghrelin levels in obese patients and serum ghrelin levels are negatively correlated with body mass index (BMI) both in obese and lean participants.[11,12] Obestatin is encoded by the same gene with ghrelin and down-regulates the effects of ghrelin on food intake. Obestatin treatment of rats suppressed food intake, inhibited jejunal contraction, and decreased body weight gain.[13,14,15,16] However, recent studies were unable to confirm the role of obestatin on food intake, body weight, or GH secretion in humans.[17,18] The data about the effect of orlistat treatment on ghrelin levels are limited.[19,20] However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no study concerning the effect of orlistat – the only approved pharmacologic treatment of obesity in our country – on both ghrelin and obestatin levels and ghrelin/obestatin ratio in obese patients. Therefore, the aim of our study was to assess the effect of weight loss with orlistat and hypocaloric diet on gut-derived hormones ghrelin and obestatin and ghrelin/obestatin ratio.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

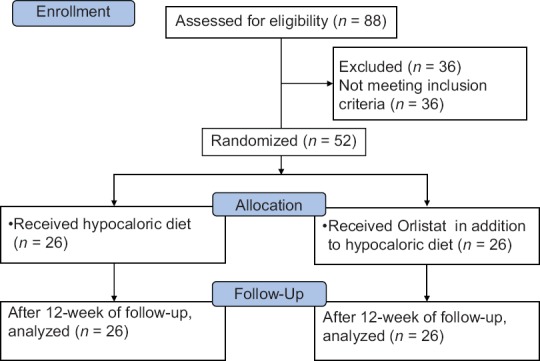

The study was a single-center, prospective, case–control study. A total of 88 sedentary obese women who were admitted to the Outpatient Endocrinology Clinic, for the treatment of obesity, were assessed for eligibility, and the flow of the study was described in Figure 1. The eligible individuals were between 18 and 60 years of age with a BMI >35 kg/m2. All the eligible individual were evaluated by serum thyroid-stimulating hormone, fT3, fT4, and morning serum cortisol after 1 mg overnight dexamethasone administration and 2 h oral glucose tolerance test with 75 g of glucose in fasting state. Patients with thyroid dysfunction or abnormal glucose metabolism or serum cortisol values >1.8 mg/dl after overnight dexamethasone suppression were excluded from the study. Furthermore, patients who had a history of cardiovascular or renal diseases and gastrointestinal disorders or who had been taking any medication known to affect body weight were excluded from the study. Finally, a total of 52 patients were enrolled in the study. The Local Ethics Committee of Tepecik Research and Training Hospital approved the study protocol, and the procedures followed were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed written consents were obtained from all participants at the beginning of the study. The patients were assigned to two groups: Group 1 (n = 26) received hypocaloric diet alone and Group 2 (n = 26) received orlistat (Thincal and Kocak) 120 mg, 3 times per day in addition to hypocaloric diet for 12 weeks. The percentages of carbohydrate, fat, and proteins were 50%, 25%, and 25%, respectively. The daily regular calorie intake was adjusted as 24 calories/kg of ideal body weight. Ideal body weight was calculated by method of Devine.[21] All the patients were followed up for 12 weeks.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of the two study groups

All the participants underwent a thorough physical examination and laboratory assessment. Anthropometric measurements were performed at the beginning and at the end of the study. Anthropometric measurements included measurement of body weight, height, and evaluation of body composition. Measurements of body weight and height were presented by the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.5 cm, respectively. Body composition was evaluated by applying leg-to-leg bioelectrical impedance (Tanita Body Fat Analyzer, TBF 300 M, Tanita, Tokyo, Japan). Assessments of body composition were standardized and performed on the morning of the study visits. The participants were questioned about their menstrual status and their fluid and food consumption, at that morning. Throughout a study period, all assessments were completed with the same material by the same investigator. The accuracy of bioelectrical impedance in the assessment of body composition in obese cases has already been reported.[22]

The blood samples were drawn – at the beginning of the study and after 12 weeks of therapy. Venous fasting blood samples were collected from an antecubital vein in 8 ml evacuated tubes without anticoagulant (Vacuette, Greiner Bio-One, Austria). Blood in the plain tubes was allowed to clot for 30 min and was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. After centrifugation, the serum samples were aliquoted, frozen, and stored at −80°C for ghrelin and obestatin analysis. Repeated freezing and thawing process was avoided. Serum total cholesterol, triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels were measured in an autoanalyzer with the manufacturer's commercially available kits (Cobas 8000, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Insulin levels were measured with chemiluminescence immunometric assay in UniCel DXI 800 analyzer (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA). Serum ghrelin (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., CA, USA) and obestatin (Alpco Diagnostics, NH, USA) levels were determined by ELISA method according to manufacturer's instructions. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variations were below 10%.

The mathematical method for homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-IR): (fasting insulin [μIU/ml] × fasting glucose [mmol/l]/22.5) was used to describe insulin resistance.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 11.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA) software was used for statistical comparisons of data. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. The hypocaloric diet group and hypocaloric diet plus orlistat group were compared using Student's-t-test. The data of basal and follow-up values after 12 weeks of therapy were compared using paired-sample t-tests and Wilcoxon signed-ranks test. Pearson correlation analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between ghrelin, obestatin, ghrelin/obestatin ratio, and various anthropometric and metabolic variables. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

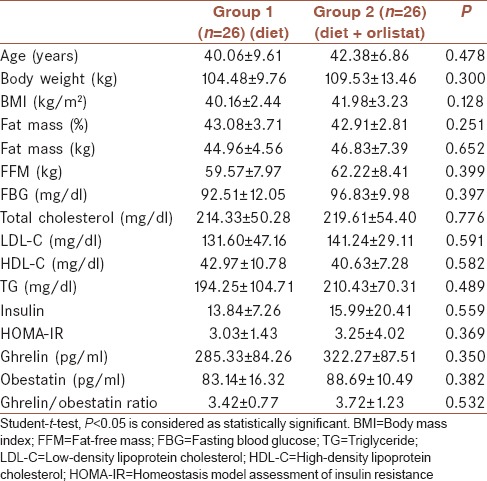

Baseline clinical characteristics, anthropometric assessments, and laboratory parameters of the two groups are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to age, body weight, BMI, fat mass, and fat-free mass (FFM). Furthermore, basal glucose, insulin and lipid levels, and HOMA values were similar between the two groups. In addition, serum ghrelin and obestatin concentrations and ghrelin/obestatin ratio were similar between the two groups.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics, anthropometric assessments, and laboratory parameters of the study population

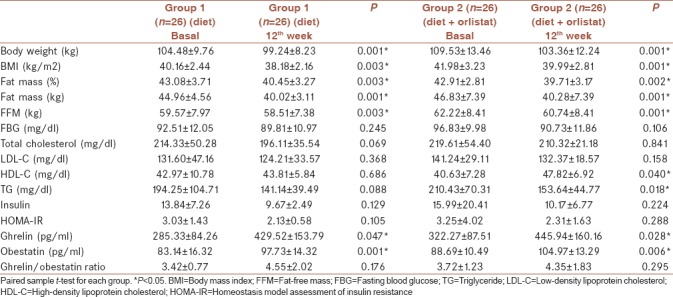

Twelve weeks of treatment resulted in a significant decrease in total body weight, BMI, fat mass, and FFM in both groups. Mean change in BMI, fat mass, and FFM were −1.97 ± 1.56 kg/m2 (P = 0.003), −2.63% ±2.11% (P = 0.003), and −1.06 ± 0.82 kg (P = 0.003), respectively, in Group 1. In Group 2, mean change in BMI was −2.11 ± 1.24 kg/m2 (P = 0.001), fat mass was −3.09% ±2.28% (P = 0.002), and FFM was −1.26 ± 0.54 kg (P = 0.001) [Tables 2 and 3]. However, fasting glucose, lipid and insulin levels, and HOMA values did not change significantly after 12 weeks in Group 1 (P > 0.05). Furthermore, except serum HDL-cholesterol and TG levels, no significant change was observed after 12 weeks of treatment in Group 2. While serum HDL-cholesterol was increased from 40.63 ± 7.28 to 47.82 ± 6.92 mg/dl (pHDL: 0.04), serum TG levels was decreased from 210.43 ± 70.31 to 153.64 ± 44.77 mg/dl (pTG: 0.018) after diet plus orlistat treatment. Although there were significant increases in serum ghrelin and obestatin concentrations, no significant change was observed in ghrelin/obestatin ratio in both groups after 12 weeks of treatment. Serum ghrelin concentration was increased from 285.33 ± 84.26 to 429.52 ± 153.79 pg/ml in Group 1 (P = 0.047) and 322.27 ± 87.51 to 445.94 ± 160.16 pg/ml in Group 2 (P = 0.028). Baseline serum obestatin concentrations were 83.14 ± 16.32 pg/ml and increased to 97.73 ± 14.32 pg/ml in Group 1 (P = 0.001), and it was increased from 88.69 ± 10.49 pg/ml to 104.97 ± 13.29 in Group 2 (P = 0.006).

Table 2.

Baseline and 12th week anthropometric assessments and laboratory parameters of both groups

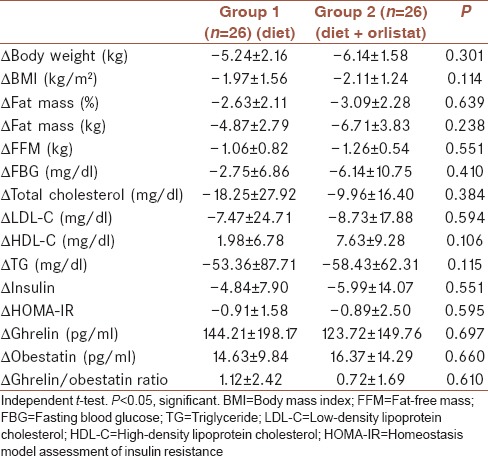

Table 3.

Changes in body composition and laboratory parameters in both groups

When the changes in anthropometric assessments and laboratory parameters were compared, no significant difference was observed between the two groups as shown in Table 3.

We found no correlation between change in BMI and ghrelin (r = −0.136, P = 0.567) or change in BMI and obestatin (r = −0.228, P = 0.335). Furthermore, there was no correlation between ghrelin or obestatin and any other anthropometric, hormonal, and metabolic parameters both at baseline and at the end of the study (P > 0.05).

No complication was observed followed by orlistat intake.

DISCUSSION

Our current research revealed that both hypocaloric diet and medical treatment with orlistat plus low-calorie diet increased serum ghrelin and obestatin concentrations in a reasonably short period of 12 weeks.

Ghrelin and obestatin (ghrelin-associated peptide) both are developed from the identical peptide precursor (preproghrelin). Ghrelin, a 28-amino acid peptide produced mainly by the stomach, was initially determined as the natural ligand of the GH Secretagogue Receptor type 1a (GHS-R1a). In addition to stimulating GH secretion, ghrelin stimulates prolactin and ACTH release, increases gastric motility and gastric acid secretion, and promotes pancreatic peptide synthesis.[23] After the elucidation of orexigenic behavior of ghrelin in rodents, it was speculated that raised levels of ghrelin could contribute to obesity in humans. Unexpectedly, it was reported that human fasting serum ghrelin levels were lower in obese patients with respect to lean participants.[24,25,26,27] This may be explained by the downregulation of ghrelin with a result of energy excess in obese patients.

Obestatin is purified from the rat stomach and binds to the orphan G protein-coupled receptor 39 that is expressed in the brain. Following peripheral administration of obestatin, significant decrease in food ingestion and body weight was observed in rodents.[17] This raises the possibility that obestatin might be involved in the regulation of energy balance and body weight. However, the data about obestatin levels in obesity are conflicting. While some studies report increased levels,[17] some reported decreased levels.[18]

Guo et al. demonstrated increased ghrelin/obestatin ratio in obesity, but Vicennati and Zamrazilova found the decreased ratio.[14,16,17] The difference in results might be explained by the difference in the study population. The study of Guo et al. included both male and female participants; however, the study of Vicenatti et al. and Zamrazilova et al. included only female participants. Furthermore, the mean baseline BMI in Guo's study was 30.1 ± 1.9 kg/m2 and in Vicennati's study was 35.3 ± 4.19 kg/m2. Since the obese group still had higher ghrelin to obestatin ratio even after adjustment for gender and age in the study of Guo et al., it is unlikely that the discrepancy in data resulted from the gender difference. Hence, larger researches are required to elucidate these controversial results.

Although obesity was associated with decreased serum ghrelin levels, after diet-induced weight loss plasma ghrelin levels were found to be increased.[24] This increase in ghrelin might be an adaptive response to prevent further weight loss by upregulating hunger levels and energy intake.[24,25] In accordance with these findings, in our study, we found increased ghrelin levels both after diet-induced weight loss or diet plus orlistat treatment-induced weight loss. However, weight loss after RYGP was reported to be associated with decreased serum ghrelin levels. Patients who underwent gastric by-pass felt less hungry and consumed fewer meals. Hence, the suppression of ghrelin was proposed as a potential mechanism by which this procedure caused weight reduction.[28] In contrast to these findings, Martins et al. reported increased plasma ghrelin and obestatin levels, but there is no difference in ghrelin/obestatin ratio after RYGB.[18]

Orlistat is a reversible inhibitor of gastrointestinal lipases that are extensively used in the pharmacotherapy of morbid obesity, and it blocks the fat absorption in the intestine, controls hypertension and dyslipidemia apart from weight loss, and decreases the risk of development of diabetes mellitus. It has been reported that orlistat had a favorable effect on insulin resistance, blood pressure, and TG levels in addition to weight loss. Previous trials demonstrated that orlistat reduced total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and TG levels.[29]

Similar to previous studies, our study revealed that orlistat treatment with a low-calorie diet regimen caused a significant decrease in TG and statistically significant increase in HDL-cholesterol levels in obese women after 12 weeks of treatment. There are only two studies which investigated the effect of orlistat therapy on serum ghrelin levels.[19,20] Ozkan et al. compared serum leptin and ghrelin levels in obese participants who take orlistat with those receiving only dietary treatment. They found lower ghrelin levels in obese participants with respect to controls and reported that ghrelin levels increased in both obese groups after 12 weeks of therapy, but the increase was similar.[19] In the other study, orlistat was found to have no effect on ghrelin levels.[20] In our study, we observed increased ghrelin levels after 12 weeks of orlistat treatment and similar to the study of Ozkan et al., we found that the increase was not different between the diet and orlistat groups.

There are no studies about the effect of orlistat on obestatin levels or ghrelin/obestatin ratio. Our study is the first study which evaluated the effect of orlistat on obestatin or ghrelin/obestatin ratio. We found increased obestatin levels both after diet-induced or diet plus orlistat therapy-induced weight loss. However, we observed no significant change in ghrelin/obestatin ratio in both groups after 12 weeks of treatment.

Ghrelin/obestatin ratio was negatively correlated with BMI and indices of abdominal fat distribution, fasting insulin, and HOMA-IR, but positively correlated with ISI composite in previous reports.[16] However, Guo et al. found a positive correlation between ghrelin/obestatin ratio and BMI.[14] In our study, we did not observe any correlation between BMI or antropometric data and ghrelin, or obestatin both at baseline and at the end of the study. This may be related to that previous studies included distinct ethnic groups of the younger age range. They showed that decreased obestatin concentrations were independently and significantly associated with impaired glucose regulation and type 2 diabetes.[30] However, in our study, we did not find any correlation between insulin or HOMA-IR and ghrelin or obestatin both at baseline and at the end of the study. This may be explained by that in our study; we excluded patients with type 2 diabetes.

Our study has a couple of limitations. First, it has a very small sample size. Second, we measured total ghrelin, not acylated ghrelin, which is thought to be principal for ghrelin biologic actions. Nevertheless, in a previous report, total ghrelin levels correlated well with the acylated ghrelin.[18,23] Third, ghrelin and obestatin concentrations merely measured in the fasting state in our study. However, ghrelin concentrations increase expeditiously after fasting in normal-weight individuals, but this rise is postponed in obese animals, suggesting that excess energy deposit adjusts short-term ghrelin secretion. On the other hand, a measuring of morning fasting ghrelin concentrations has been reported as a reliable approach to characterize ghrelin status even if ghrelin is released episodically.[31] Furthermore, our study sample included only female patients and we did not measure fasting plasma ghrelin and obestatin levels in lean control volunteers for comparison.

In summary, this is the first study that evaluated the effect of low-calorie diet and diet plus orlistat in obese premenopausal women on orexigenic hormone – ghrelin and anorexigenic hormone – obestatin ratio. Weight loss with diet and diet plus orlistat is associated with increased ghrelin and obestatin concentrations.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eckel RH, York DA, Rössner S, Hubbard V, Caterson I, St Jeor ST, et al. Prevention conference VII: Obesity, a worldwide epidemic related to heart disease and stroke: Executive summary. Circulation. 2004;110:2968–75. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140086.88453.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tavassoli A, Gharipour M, Toghianifar N, Sarrafzadegan N, Khosravi A, Zolfaghari B, et al. The impact of obesity on hypertension and diabetes control following healthy lifestyle intervention program in a developing country setting. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16(Suppl 1):S368–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahn SE, Leonetti DL, Prigeon RL, Boyko EJ, Bergstrom RW, Fujimoto WY, et al. Relationship of proinsulin and insulin with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease in japanese-american men: Impact of obesity – Clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:1399–406. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.4.7714116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stürmer T, Günther KP, Brenner H. Obesity, overweight and patterns of osteoarthritis: The ulm osteoarthritis study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:307–13. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeRoith D, Novosyadlyy R, Gallagher EJ, Lann D, Vijayakumar A, Yakar S, et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes are associated with an increased risk of developing cancer and a worse prognosis; epidemiological and mechanistic evidence. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2008;116(Suppl 1):S4–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1081488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson DF, Serdula MK, Anda RF, Levy A, Byers T. Weight loss attempts in adults: Goals, duration, and rate of weight loss. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1251–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.9.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller WC, Koceja DM, Hamilton EJ. A meta-analysis of the past 25 years of weight loss research using diet, exercise or diet plus exercise intervention. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21:941–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, Sjöström L. XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: A randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:155–61. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gokcel A, Gumurdulu Y, Karakose H, Melek Ertorer E, Tanaci N, BascilTutuncu N, et al. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of sibutramine, orlistat and metformin in the treatment of obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2002;4:49–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2002.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miles JM, Leiter L, Hollander P, Wadden T, Anderson JW, Doyle M, et al. Effect of orlistat in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1123–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosoda H, Kojima M, Kangawa K. Biological, physiological, and pharmacological aspects of ghrelin. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;100:398–410. doi: 10.1254/jphs.crj06002x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leite-Moreira AF, Soares JB. Physiological, pathological and potential therapeutic roles of ghrelin. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:276–88. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang JV, Ren PG, Avsian-Kretchmer O, Luo CW, Rauch R, Klein C, et al. Obestatin, a peptide encoded by the ghrelin gene, opposes ghrelin's effects on food intake. Science. 2005;310:996–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1117255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo ZF, Zheng X, Qin YW, Hu JQ, Chen SP, Zhang Z, et al. Circulating preprandial ghrelin to obestatin ratio is increased in human obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1875–80. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zizzari P, Longchamps R, Epelbaum J, Bluet-Pajot MT. Obestatin partially affects ghrelin stimulation of food intake and growth hormone secretion in rodents. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1648–53. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vicennati V, Genghini S, De Iasio R, Pasqui F, Pagotto U, Pasquali R, et al. Circulating obestatin levels and the ghrelin/obestatin ratio in obese women. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;157:295–301. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zamrazilová H, Hainer V, Sedlácková D, Papezová H, Kunesová M, Bellisle F, et al. Plasma obestatin levels in normal weight, obese and anorectic women. Physiol Res. 2008;57(Suppl 1):S49–55. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martins C, Kjelstrup L, Mostad IL, Kulseng B. Impact of sustained weight loss achieved through roux-en-Y gastric bypass or a lifestyle intervention on ghrelin, obestatin, and ghrelin/obestatin ratio in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2011;21:751–8. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0399-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozkan Y, Aydin S, Donder E, Koca SS, Aydin S, Ozkan B, et al. Effect of orlistat on the total ghrelin and leptin levels in obese patients. J Physiol Biochem. 2009;65:215–23. doi: 10.1007/BF03180574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellrichmann M, Kapelle M, Ritter PR, Holst JJ, Herzig KH, Schmidt WE, et al. Orlistat inhibition of intestinal lipase acutely increases appetite and attenuates postprandial glucagon-like peptide-1-(7-36)-amide-1, cholecystokinin, and peptide YY concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3995–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pai MP, Paloucek FP. The origin of the “ideal” body weight equations. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:1066–9. doi: 10.1345/aph.19381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deurenberg P. Limitations of the bioelectrical impedance method for the assessment of body fat in severe obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64:449S–452S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.3.449S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang N, Yuan C, Li Z, Li J, Li X, Li C, et al. Meta-analysis of the relationship between obestatin and ghrelin levels and the ghrelin/obestatin ratio with respect to obesity. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:48–55. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181ec41ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cummings DE, Weigle DS, Frayo RS, Breen PA, Ma MK, Dellinger EP, et al. Plasma ghrelin levels after diet-induced weight loss or gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1623–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reinehr T, de Sousa G, Roth CL. Obestatin and ghrelin levels in obese children and adolescents before and after reduction of overweight. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;68:304–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tschöp M, Weyer C, Tataranni PA, Devanarayan V, Ravussin E, Heiman ML, et al. Circulating ghrelin levels are decreased in human obesity. Diabetes. 2001;50:707–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.4.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eminler AT, Aygun C, Konduk T, Kocaman O, Senturk O, Celebi A, et al. The relationship between resistin and ghrelin levels with fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19:1058–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth CL, Reinehr T, Schernthaner GH, Kopp HP, Kriwanek S, Schernthaner G, et al. Ghrelin and obestatin levels in severely obese women before and after weight loss after roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2009;19:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9568-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rössner S, Sjöström L, Noack R, Meinders AE, Noseda G. Weight loss, weight maintenance, and improved cardiovascular risk factors after 2 years treatment with orlistat for obesity. European orlistat obesity study group. Obes Res. 2000;8:49–61. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qi X, Li L, Yang G, Liu J, Li K, Tang Y, et al. Circulating obestatin levels in normal subjects and in patients with impaired glucose regulation and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:593–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akamizu T, Shinomiya T, Irako T, Fukunaga M, Nakai Y, Nakai Y, et al. Separate measurement of plasma levels of acylated and desacyl ghrelin in healthy subjects using a new direct ELISA assay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]