Abstract

Purpose of the Study:

Financial fraud is estimated to cost consumers approximately $50 billion annually. To examine how new hires are trained to engage in fraud, this study analyzed a sales training transcript from Alliance for Mature Americans (Alliance). In 1996, Alliance was charged with using deception and misrepresentation to sell more than $200 million worth of living trusts and annuities to 10,000 older adults in California.

Design and Methods:

Transcribed recordings from a 2-day Alliance sales training seminar were analyzed using NVivo10, coded inductively, and examined to identify emergent themes.

Results:

Predominant themes were as follows: (a) indoctrination using incentives and neutralization techniques and (b) training on persuasion tactics targeted at older adults. Findings suggest that sales training focuses on establishing the company’s legitimacy, normalizing unethical sales practices, and refining trainees’ knowledge about how to influence older consumers.

Implications:

Predatory and fraudulent businesses peddling ill-suited products threaten the economic security of older Americans. Improved insights into sales manipulation strategies can guide the development of protective policies including educational approaches to help older adults detect scams and resist purchasing fraudulent products.

Keywords: Persuasion knowledge, Consumer fraud, Neutralization techniques, Persuasion tactics, Sales tactics, Indoctrination

Consumer financial fraud is defined as “deliberately deceiving the victim with the promise of goods, services, or other benefits that are nonexistent, unnecessary, never intended to be provided, or grossly misrepresented” (Titus, Heinzelmann, & Boyle, 1995). Businesses oriented to the “mature market,” both legitimate and fraudulent, have mushroomed in response to the increased buying power of today’s older adults who are generally wealthier and better educated than past cohorts (Butrica, Smith, & Iams, 2012).

In a national prevalence survey conducted by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), 7.3% of adults aged 65–74 and 6.5% of adults aged 75 and older reported fraud in the past year (Anderson, 2012). Conservative estimates suggest that, in addition to the social and emotional costs of victimization, fraud results in an annual loss of approximately $50 billion among all age groups in the United States (Deevy, Lucich, & Beals, 2012). Victims who are unable to replenish their losses may be left to rely on social welfare programs, such as Medicaid and Supplemental Security Income, for medical and financial support. Although it remains unclear whether older adults experience higher rates of victimization than younger age groups, it does appear that they are less likely to acknowledge and report losing money to fraud or to seek recourse after being swindled (Pak & Shadel, 2011).

A better understanding of how scams operate is one approach to improving policies that can safeguard the financial security of older adults and thereby reduce dependency on Federal programs (U.S. Government Accountability Office [GAO], 2012). Although some qualitative research has examined the perspectives and experiences of fraud victims (e.g., Kerley & Copes, 2002; Pak & Shadel, 2011), there has been very little inquiry into the world of those who perpetrate fraud. To better understand the process of how sales agents are trained to deceive older adults, this study uses qualitative methods to analyze a sales training transcript from a company that was charged with committing fraud against older adults.

Background and Significance

The Persuasion Knowledge Model

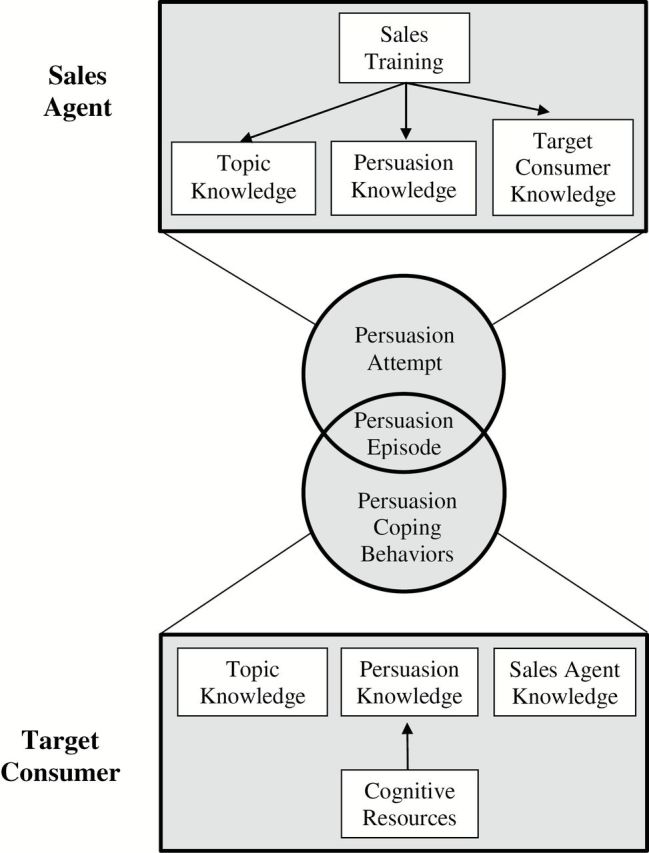

The Persuasion Knowledge Model (PKM), developed by Friestad and Wright (1994), suggests that consumers (targets) develop a broad schema about salespersons’ (agents) goals, behaviors, and tactics and use this knowledge to cope with persuasion attempts. Defined broadly, persuasion knowledge includes what consumers believe about how to persuade others and what they believe others know about how to persuade them (for full explanation of the PKM, see Friestad & Wright, 1994).

During the sales pitch (persuasion episode), consumers rely on three knowledge structures to guide their response: (a) topic knowledge (prior knowledge about the product), (b) persuasion knowledge (knowledge related to recognizing, remembering, and interpreting persuasion attempts), and (c) agent knowledge (beliefs about the salesperson’s traits, competencies, and goals). Likewise, agents rely on their own persuasion, topic, and target knowledge to choose effective influence strategies.

Campbell and Kirmani (2000) expanded the PKM to include the mediating effect of cognitive resources on consumers’ ability to access persuasion knowledge and cope with persuasion attempts. According to their model, consumers who are cognitively busy have less capacity to draw upon their existing persuasion knowledge to identify an agent’s ulterior motives. They, therefore, appraise the agent’s persuasion messages as more sincere. Cognitive resources can also be affected by age-related changes in cognition and decision-making capacity (Dong, Simon, Rajan, & Evans, 2011; Triebel & Marson, 2012) that may increase vulnerability to persuasion in several ways. Declines in financial decision making is an early manifestation of mild cognitive impairment (Triebel & Marson, 2012), and research indicates that compared with younger adults, older adults are less sensitive to “untrustworthy” facial characteristics (Castle et al., 2012), are less able to detect lying (Ruffman, Murray, Halberstadt, & Vater, 2012), and are less likely to recall information in advertisements but more prone to be persuaded by the information (Phillips & Stanton, 2004). Moreover, some elders who are considered cognitively healthy have subtle declines in judgment (Boyle et al., 2012), which may affect susceptibility.

We present an adapted version of the PKM (Figure 1) that includes the mediating effects of cognitive resources as suggested by Campbell and Kirmani (2000). Our framework depicts how age-related cognitive declines may interfere with some older adults’ ability to draw on their persuasion knowledge to identify salespersons’ ulterior motives, thus making them more vulnerable to fraud than those without impairment.

Figure 1.

Adaptation of Friestad and Wright’s (1994) Persuasion Knowledge Model (PKM). A persuasion episode consists of a dyadic interaction between a sales agent and a target consumer. Sales training reinforces and refines sales agents’ knowledge about the topic (the product or service), the target, and how to persuade the target. The target consumers’ cognitive resources affect their ability to draw on persuasion knowledge to make inferences about sales agents’ ulterior motives. This task requires higher-level attributional processing, which is affected by cognitive load (Campbell & Kirmani, 2000). Persuasion coping behaviors are consumers’ adaptable responses to contend with persuasion attempts to ensure that outcomes are in their best interests.

Friestad and Wright (1994) argue that persuasion knowledge develops through experience and observation. In the sales context, training offers a means through which new sales agents learn precise persuasion, topic, and target knowledge. Training is designed to introduce and/or reinforce perceptions about target consumers’ identities, beliefs, motives, and goals, and how targets can be persuaded to comply.

As shown in Figure 1, teaching sales agents how to influence older adults to target older adults may reinforce stereotypes that elders are senile, foolish, and miserly (e.g., Nuessel, 1982), along with perceptions that they yield greater financial returns (Marson & Sabatino, 2012). Thus, even if older adults are not inherently more vulnerable to fraud, it is possible that they are disproportionately targeted by agents who believe they are easier to deceive.

Masterminding the Scam

In contrast to elder financial abuse where the perpetrator is a family member, close friend, or someone in a formal fiduciary role that uses his or her position of trust to take advantage of the elder, perpetrators of fraud are generally unknown or unrelated to their victims (Conrad, Iris, Ridings, Langley, & Wilber, 2010). They include salespersons, contractors, accountants, real estate, or insurance agents (Kemp & Mosqueda, 2005).

Perpetrators may use persuasion tactics popular in everyday sales practices to influence their targets (Financial Industry Regulatory Authority [FINRA], 2006). Examples include establishing a trust relationship with the consumer, fear arousal, and claiming to be associated with a legitimate organization. They may also use phantom fixation (dangling promises of wealth), scarcity (stating product supply is limited), and social consensus (stating that everyone is buying the product) to elicit compliance (Cialdini, 2007; FINRA, 2006). Use of these common influence tactics make it difficult for consumers and federal regulators to distinguish fraud from legitimate offers.

Scams can be the work of an individual, a small group, or a corporation. They can also be orchestrated from different locations with a growing number now operating from abroad (FTC, 2010). Little is known about the practices used in perpetrating large, well-organized scams, and virtually no studies have used instructional materials to examine how salespersons are conditioned to commit unethical acts on behalf of their employer and the persuasion tools they are taught to deceive older targets.

This article focuses on a door-to-door trust/annuity sales scam perpetrated by Alliance for Mature Americans (Alliance), a defunct California-based corporation comprised of nearly 30 telemarketers and 155 contracted sales representatives. Alliance fronted as a senior citizens’ organization dedicated to assisting older adults by providing free living trust consultations and other “benefits.” Soliciting elders through telemarketing, direct mail, television, radio, and senior centers, the company used misleading high-pressure sales tactics to peddle an average of 350 trusts per week at $1,000–$2,000 or more each, depending on how much the client could be persuaded to pay.

The living trust sale was a guise to build rapport and obtain clients’ personal financial information; the ultimate goal was to sell these same clients long-term annuities. Salespersons were paid commissions on trust sales (30%) and received an additional 10%–12% for referrals and any subsequent annuity sales.

Alliance avoided hiring insurance agents and did not provide formal training in estate planning. Instead they required new sales agents to attend a 2-day sales training workshop for $250 to become “Certified Trust Advisors.” The focus of this study is a training workshop held in 1995 in Southern California. Approximately 30 trainees participated by watching advertising clips and listening to oral presentations led by Alliance’s legal council, marketing team, co-owner, and regional sales managers. Training featured an overview of the company, information on living trusts, employee benefits, sales incentives, rules and expectations, and advice on selling to older adults. Alliance recorded the workshop on six double-sided cassette tapes for future training purposes.

In 1996, the State of California and the State Bar of California brought civil charges against Alliance for scamming nearly 10,000 older adults out of more than $200 million through deceptive sales practices (Case No. BC153983). Executives were charged with committing acts of unfair competition, using untrue or misleading marketing tactics, unauthorized practice of law, professional misconduct, and violating insurance trade practices.

Alliance was required to submit the training workshop recordings to the court as authorized under the Civil Discovery Act of 1986 (Title 4; §2016–2036). Tapes were transcribed by a professional transcription service, yielding 792 quarter-pages of text, and filed in the public record. The last author served as a paid expert witness on the case; all other authors had no previous knowledge or affiliation with the case.

Research Questions

The purpose of this study is to identify the techniques used by Alliance executives and senior sales representatives to convince trainees to sell their products and the sales tactics they promoted. This study aimed to answer:

How does a company motivate representatives to engage in unethical sales practices?

What are the influence tactics used to persuade older consumers to buy products that may not serve their interests?

Methods

Coding and Analysis

The training workshop transcript was scanned and uploaded into QSR NVivo10, a computerized text analytic software program designed for content categorization. Two authors read the transcript several times to familiarize and immerse themselves in the data. Working independently, they identified phrases that expressed important attitudes, persuasion tactics, narratives, and values—a process called “open coding” (Saldaña, 2013). They discussed, refined, and collapsed codes with similar meanings into 21 distinct codes with definitions, then recoded the transcript independently using this final list.

To improve interrater reliability, the coding team randomly selected 35% of the coded transcript to review together. Differences in interpretation were reconciled by discussing the context and meaning behind ambiguous statements and reviewing the code definitions. Coding was finalized on a shared transcript file to calculate Kappa coefficients, a stringent measure of interrater reliability (Landis & Koch, 1977).

NVivo10 text analytic tools were used to determine word frequencies, construct code hierarchies, and build cross-code matrices to identify patterns and linkages between concepts to answer the research questions (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2013). These data synthesis tools assisted in grouping conceptually similar codes into broader thematic categories. For example, the codes “company buy-in” and “company values” were often used to label the same chunks of text. They were consolidated into an overarching subtheme labeled “establishing legitimacy.” Themes and subthemes (Table 1) are summarized in the results along with supporting quotes from the sales training.

Table 1.

Summary of Tricks of the Trade Themes and Subthemes

| Theme | Definition |

|---|---|

| Major Theme 1: Indoctrination of trainees using incentives and neutralization techniques | |

| Establish legitimacy | Attempts to establish the credibility of Alliance and its financial products by emphasizing the company’s growing size, prestige, and profits. Objective is to make the trainee a coconspirator in the scam by building a sense of ownership in Alliance and its products. |

| Instill a sense of moral authority | Instilling the belief that sales agents are doing clients a favor by using any means necessary to sell them living trusts as a tool to protect them from probate costs, thereby helping build a legacy for their heirs. |

| Reinforce ageist stereotypes | Statements that describe how the company depicts their typical older client—for example, unsophisticated, forgetful, lonely, patriotic, conservative, fearful of technology, loving, and proud of their children/grandchildren. |

| Offer incentives | Emphasizing the financial and travel benefits awarded for reaching sales quota or for new client referrals. Includes flexibility in work schedule, opportunities for promotion, all-expense paid vacations, and health coverage. |

| Encourage conformity | Pressure to adhere to the sales protocol and company policies. Expectations for dress, behavior, and for using Alliance’s scripted persuasion messages to optimize sales. |

| Major Theme 2: Persuasion tools and tactics for selling to older adults | |

| Scapegoating | Generating an “us versus them” mentality by scapegoating probate lawyers and estate taxes while presenting Alliance as a legitimate provider of estate planning products. |

| Emotional arousal | Manipulating the clients’ fears about losing control over financial assets and personal autonomy. Playing on their desire to pass on a legacy to their family members. Use of emotionally laden narratives to generate anxiety, build a sense of urgency, and convince clients to divulge private information. |

| Build rapport | Building rapport to earn clients’ trust and confidence—for example, empathizing with and flattering clients to convince them that Alliance and its sales agents have their best interests in mind. |

| Illusion of control | Giving clients a false sense of control over the sales negotiation by asking them leading questions and pretending that a living trust may not apply to their particular circumstances to put them falsely at ease. |

| Reciprocity | Creating a debt by offering small favors (like price reduction) to convince clients to agree to a larger request later on. Also, making small requests to get clients accustomed to saying yes to the sales agent (early commitment). |

| Persistence | Establishing a sense of urgency to close the deal without providing time for clients to think over the offer. Use of aggressive, high-pressure tactics to persuade clients to sign documents and disclose their financial information. |

| Diversion | Diverting clients’ attention away from the cost and consequences of buying a living trust by asking them unrelated or personal questions. |

Results

Interrater Reliability

Of the 21 codes, 12 Kappa values were acceptable (between 0.30 and 0.40) and seven Kappas ranged from 0.40 to 0.80, indicating moderate to excellent reliability (Landis & Koch, 1977). Poor resolution of the original scanned and uploaded transcript impeded NVivo10 software from correctly distinguishing text from background, resulting in random coding inconsistencies that were unrelated to differences in conceptual understanding between coders. This technical problem substantially decreased two Kappa estimates with the fewest references: “terminology” and “company values.” Although their Kappa coefficients were low—0.18 and 0.28—the coders discussed these codes in depth to ensure interrater reliability.

Themes

Thematic analysis revealed two predominant themes. The first, indoctrination of trainees using incentives and neutralization techniques, included strategies to condition new sales agents to “buy-in” to Alliance’s values and goals. This was accomplished by promising financial and travel incentives and affirming the legitimacy of the company and its products to normalize unethical selling practices. Neutralization techniques—verbal and symbolic rationalizations for unethical behavior (Sykes & Matza, 1957)—were used to instill a sense of moral authority, whereby sales agents were told they had an ethical obligation to “protect” older adults’ estates from probate.

The second major theme, persuasion tactics, included building rapport and emotional arousal to elicit compliance and scapegoating, whereby the salesperson claimed to offer financial protection from unscrupulous probate lawyers and high estate taxes. Messages were specifically crafted to convince clients to disclose personal and financial information and divert them from evaluating the risks of the transaction, reading the documents they signed, and consulting with financial planners or legal counsel.

Tricks of the Trade: A “How To” Guide to Scamming Older Adults

Within these two main themes, several subthemes emerged (Table 1). They are delineated subsequently in the order in which they were presented at the training.

Theme 1: Indoctrinate Sales Agents

Establish legitimacy.

“We fully guarantee our product completely. Completely. We stand behind it completely. We’ll make sure they’re happy” (Alliance co-owner).

Because Alliance relied on a sales team to enthusiastically market their business to consumers, establishing legitimacy was an important objective. In her welcome statement to the trainees, Alliance’s cofounder stated, “We have, ladies and gentlemen, the finest trust estate planning product on the market today, bar none. I am so proud of what we offer.” She also boasted about the company’s annual profit growth: “We did $100,000,000 in 1994, and we’ve already exceeded $110,000,000 so far this year in 1995. So it’s a very rapidly growing company. Tons of opportunity here.” The objective was to cultivate trainees’ confidence in Alliance and to make them feel proud to join a cutting-edge and growing business.

Instill a sense of moral authority.

“First of all let me congratulate you because it’s an absolutely wonderful, wonderful business. You have an opportunity here to really make a difference in somebody’s lives” (Alliance co-owner).

Another tactic was instilling a belief that sales agents had an ethical duty to help older consumers avoid probate. Older adults were portrayed as deserving sympathy and respect: “They’ve given their lives in the different wars…Those wars were fought by them to enable you the freedom to go wherever you wanted to go and work wherever you wanted” (Alliance Annuity Department Supervisor). Elders were also depicted as being vulnerable to exploitation by probate attorneys: “…so anytime we can sell a living trust to keep those claws from the probate attorneys off their money that’s supposed to go their family and their heirs, life is good. We have done a good job there” (Alliance co-owner). Sales agents were told they were protecting unsophisticated consumers who would lose significant portions of their estates without Alliance’s services: “They need these things. All right…I mean you’re helping them even if they don’t realize it.”

Trainees were also reassured that they were doing a service while helping themselves: “I mean it’s a great product. It’s a win-win… There’s no reason you can’t have integrity in what you’re doing and feel pretty good about it and make a lot of money” (Regional Sales Manager). Using the trainees’ families as justification, one workshop presenter normalized selling the trust at an inflated value: “…if you can get a few extra hundred bucks, I mean, you know, your family deserves it.”

Reinforce ageist stereotypes.

“…if you see them going [to sleep] don’t keep talking…Time for Flintstones vitamins” (Regional Sales Manager).

Another tactic was using stereotypes to depersonalize older clients and inoculate new recruits from the moral ambiguity of using deception. Elders were portrayed as unsophisticated, fiscally conservative, suspicious of technology, and devoted to their families: “They love America. They’re patriotic. They love this country. They love God. They love apple pie. They’re very family oriented” (Alliance co-owner). Stereotypes that depicted elders as “simple minded” affirmed that sales agents were morally obligated to protect them from “the agony of probate” while suggesting they are easy to dupe. A regional sales manager noted, “…we’re dealing with senior citizens. Some of them are getting a little forgetful.”

Offer incentives.

“You’re an independent contractor. You’ve all always wanted to work for yourselves and now you’re doing it. So you’re in control of your own destiny here” (Alliance co-owner).

Training instructors touted the many financial and travel benefits available to Alliance’s contracted sales representatives. Incentives included all-expense paid vacations to Banff and Jamaica, dinners at expensive restaurants, health care benefits, and promotion to “Trust Delivery Agent” to sell annuities and earn higher commissions.

Narratives about the potential for wealth and power were present throughout the training: “The people selling annuities are buying new houses…buying new cars, you know, doing the things that money allows you to do after you’ve just paid your bills” (Alliance co-owner). Speakers also promised freedom, control, and flexibility as an Alliance representative: “One of the nice things about this company is you can live where you want, just run where the leads are” (Regional Sales Manager).

Encourage conformity.

“But if you work the steps that we set down and do it that way and don’t try to put the cart before the horse and just work the system, you know, you’ll be successful” (Alliance co-owner).

Presenters suggested that salespeople should “Look like an attorney for a bank” and emphasized that Alliance’s highest earning representatives were those who adhered to the standardized sales protocol. New trust agents were given copies of the sales manual—the “pitch book”—that described how to structure interactions with clients. The sales pitch began with the warm-up (building rapport), followed by the smoke-out (extracting information), and finally the close (convincing the client to write a check). To bolster credibility, they were instructed to show clients articles from past Wall Street Journal periodicals that lamented the cost of probate and lauded the benefits of living trusts.

Trainees were told to avoid mentioning the goal of selling annuities because “…when we’re trying to sell the trust, we shouldn’t mention the annuity at all or they’d cancel the trust” (Regional Sales Manager). They were also discouraged from mentioning the price until they had fully described the trust’s advantages and had obtained the client’s personal and financial information.

Theme 2: Equip Sales Agents With Effective Persuasion Tactics Targeted at Older Adults

Scapegoating.

“Probate’s not fun…So I’m at least going to tell them as the educator, as the person that’s going to inform them. I’m going to tell them about probate” (Regional Sales Manager).

Presenters referred to probate attorneys as “scum suckers” and “lower down than whale manure.” They described probate as “costly, time consuming, and incredibly frustrating.” In contrast, Alliance was portrayed as serving the welfare of seniors. According to a speaker from Alliance’s Deeds Department, “We’re actually building a legacy for these individuals and it’s something that’s very important to them, meaningful while they’re here and while they’re gone.” By creating an “us versus them” mentality, sales agents and clients could share a common enemy and a common goal: to prevent probate attorneys and estate taxes from depleting the elder’s estate and leaving less inheritance for the family.

Emotional arousal.

“You need to get them to want the trust. And that means you’re going to need to get them to be emotionally involved in the purchase of a trust” (Regional Sales Manager).

Trainees were instructed to customize their sales pitch around clients’ emotional “hot buttons”—topics or issues that personally motivated clients to buy. Advice from one sales manager was to “…put fear in their mind that if they don’t do anything today it’s never going to get done and the family’s going to end up in probate.” Hot buttons often focused on age-related concerns, such as the desire for financial autonomy, anxiety about cognitive and physical decline, and fear of disappointing family members for poor financial planning. According to one presenter, “…you can get them on the family because that’s what they’re protecting. They don’t care about the money. They’re protecting the family.” Presenters suggested using phrases like, “What are you waiting for?” and, “Why haven’t you done anything?” to persuade elders to disclose personal information about their fears, annoyances, and concerns: “Bingo, another hot button right there. Ask them and they will tell you” (Regional Sales Manager).

Build rapport.

“If you got enough rapport built up with them and you got a free, easygoing banter between the two of you, they’ll tell you exactly why they didn’t buy the last time or they’ll apologize for not buying” (Regional Sales Manager).

To appear to serve the client’s best interests, trainees were coached to say they had come to provide a “free periodic trust review” and to treat elders like family members: “I talk to people just today just like they were my grandfather and my grandmother” (Alliance co-owner). They were encouraged to flatter the client and compliment the client’s house and memorabilia to build rapport while gathering personal details. Using this information, sales agents were advised to customize their sales pitch to the client’s psychological profile and personal values.

Illusion of control.

“And always let them think they’re winning. That’s what they want to do. They want to deal. They want to win.” (Alliance co-owner).

Trainees were instructed to make clients think they were setting the terms of the sale, when in fact the interaction was engineered to benefit the sales agent—a tactic called “landscaping” (FINRA, 2006). They were given examples of leading questions that appear to provide choice yet actually solicit agreement: “Doesn’t it, isn’t it, shouldn’t it, wouldn’t it, couldn’t it, don’t you agree? Things like that. Get them involved” (Regional Sales Manager). To lower the clients’ defensive shield, trainees were directed to mislead clients about their intentions to sell them a trust. A regional sales manager instructed them to say, “…believe me, the last thing I’m going to ask you to do today is agree to do business with us.”

Trainees were coached to use features of the living trust to give clients a sense of control. Living trusts were presented as the only mechanism for elders to govern how their assets would be distributed after death. A regional sales manager illustrated,

I can’t tell you what to do. My attorneys can’t tell you what to do. Your kids can’t tell you what to do. You can get advice from whomever you chose, but you’re the person that has the final say. You have complete control just as you do today.

Finally, trainees were told to make clients feel like they owned the product by labeling it with their names before they consented to buy it: “And you’ll notice that I keep referring to it as ‘her trust.’ Okay. I want her to own it,” and, “Give them two choices. ‘Do you like the Jones Living Trust or the Edith Jones Living Trust better?’” (Regional Sales Manager).

Reciprocity.

“Mrs. Jones, one of my last clients got this [coupon] in the mail and he gave it to me. If you’re interested in getting a trust, I can offer it to you today” (Regional Sales Manager).

To establish a culture of reciprocity, presenters suggested that trainees provide small benefits, such as offering a discount or pretending to negotiate the price with their managers over the phone. Trainees were also told to ask clients for favors early in the negotiation set the stage for larger requests later on. According to one presenter,

You know a lot of times I’ll ask people for a drink when I get in their house. That way they have to kind of get up and get me stuff…if they’re running around getting stuff for me, they’re going to be used to getting stuff for me later on and it makes me seem a little more like I’m an honored guest in their house rather than somebody who is big and pretentious.

Persistence.

“And I told clients…‘Put on the coffee pot because I’m not going to leave until you buy this.’ And I’m serious. I’m serious as a heart attack. …I will be there until they buy because I believe in it” (Alliance co-owner).

Trainees were told to close the deal on the first visit because clients would not purchase a trust the second time they were solicited. A presenter stated, “The secret to selling the trust: Do not get up from the table until you are done.” No matter how firmly clients resisted, trainees were instructed to persevere: “…hang on like a pit bull and don’t let go” (Alliance co-owner). They were given strategies to overcome nearly every possible objection including sharing testimonials of elders whose families were devastated by probate because they refused to buy a trust.

Instead of giving clients the trust application to fill-out after agreeing to the deal, trainees were instructed to fill-in clients’ personal and financial information during the sales pitch without their permission. According to a sales manager, this was a “tried and true” strategy to establish early commitment. It was also a scheme to collect information about the size of the elder’s estate to set the arbitrary price for the trust.

Diversion.

“I want them busy. Why do I want them busy? So they don’t sit there and, you know, come out and think about it. You don’t want them coming out of the ether” (Regional Sales Manager).

Alliance presenters suggested various distraction techniques to avoid possible objections. One regional sales manager described his favorite closing strategy: “‘While I’m here, let me get some information.’ That’s my close. I’ll never get them to agree to buy the trust… When they sign the check, I’ll get that as the agreement… They don’t even know what’s going on.” Another presenter stated, “She might not know what she’s doing, but she’s going to get her checkbook.”

Discussion

This study examined how new sales agents were trained to sell living trusts to older adults who would later be targeted to buy questionable investments that did not necessarily serve their interests. Motivation and sales approaches from the workshop include (a) indoctrination of trainees using incentives and neutralization techniques and (b) persuasion tools and tactics for selling to older consumers.

As depicted in the modified PKM (Figure 1), training is designed to educate sales representatives about the topic (what they are selling), the target (who they are selling to), and persuasion (how to sell effectively). Similar to legitimate businesses, Alliance’s profitability depended on convincing its agents, and ultimately its consumers, that the organization was credible, provided a necessary and important service to older adults, and offered opportunities for its workers to prosper. Ultimately, the trainees were misled about what they were selling and the characteristics and needs of the target consumer.

Neutralization Techniques

Perhaps the most remarkable finding was that while posing as a legitimate business, Alliance actively sanctioned the use of deception, distraction, and persuasion based on stereotypes about older adults. To indoctrinate trainees, Alliance presenters used neutralization techniques—verbal and symbolic rationalizations for engaging in immoral behavior to minimize self-blame and reduce feelings of moral dissonance (Sykes & Matza, 1957; Vitell & Grove, 1987). Rationalizations may include denying responsibility or harm to the consumer, blaming the victim, and appealing to higher loyalties (Vitell & Grove, 1987). Internalizing neutralization messages helps workers identify with the moral climate of their organization and to comply with unethical directives (Umphress & Bingham, 2011).

Alliance employed scapegoating devices, in which another party (i.e., probate lawyers) is singled out for disproportionately negative treatment to generate an “us versus them” mentality. Scapegoating redirected blame and reassured trainees that Alliance’s products were in the clients’ best interests and that deception was sometimes needed to protect unsophisticated elders from the “greedy claws” of probate lawyers.

Although Alliance’s indoctrination tactics were deceptive, they mimic strategies used by legitimate organizations to promote company loyalty and increase sales. First, financial and travel incentives were used to motivate trainees. Second, presenters portrayed themselves as personable, successful, and supportive while galvanizing trainees with promises of wealth, status, and professional autonomy. These tactics are supported by research showing that positive social exchange relationships foster loyalty and compliance in corporate environments (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Employees who perceive their leaders as fair and supportive are more likely to reciprocate even if the reciprocated behaviors they are asked to perform are unethical (Umphress & Bingham, 2011).

Although one explanation is that recruits were naive and impressionable, Schneider’s (1987)Attraction Selection Attrition model suggests that people seek to work for organizations compatible with their personality and professional experience. Thus, rather than Alliance indoctrinating employees to act immorally, it is possible that less ethical people were drawn to work for Alliance. Trainees may have suspected they were hired to sell questionable products and were not opposed to using deception in their sales pitch.

Persuasion Tactics

Los Angeles Superior Court ruled that Alliance engaged in “unfair, fraudulent, and deceptive business practices in the marketing of its trusts and annuities,” yet the persuasion devices themselves were not illegal. Although Alliance used hard-sell tactics to commit acts of fraud, similar influence tactics to those mentioned in the training, such as reciprocity and building rapport (liking), are prominent among legitimate companies and are well documented in marketing and consumer psychology literature (e.g., Cialdini, 2007).

Alliance’s sales training was designed to refine sales agents’ target and persuasion knowledge. Agents were instructed to exploit stereotypical assumptions about the goals, emotions, values, and cognitive abilities of older persons. Many of these tactics relied on ageist beliefs about older adults’ distractibility and their perceived inability to comprehend complex financial information. Agents were trained to divert clients’ attention away from processing the cost and consequences of buying Alliance’s products and were also instructed to repeat “the agony of probate,” “you need a living a trust,” and “we have the very best product” to solidify these messages into implicit truths. Repetition is a tactic based on the “truth effect” (Hasher, Goldstein, & Toppino, 1977)—when repeated information is perceived more valid and believable. Older adults with cognitive impairments are generally more susceptible to this illusion (Denburg et al., 2007). As depicted in Figure 1, cognitive resources affect the accessibility of persuasion knowledge, which is needed to infer agents’ true motives (Campbell & Kirmani, 2000).

Although older adults perform well when recalling familiar information (Craik & Jennings, 1992), they are also more prone to source misattribution and misremembering whether claims about a product are good or bad (Skurnik, Yoon, Park, & Schwarz, 2005). Fraudulent marketers can manipulate these tendencies by misleadingly adopting the name of a salient brand or organization to make consumers think that their business is legitimate. For example, Alliance sales agents were coached to confound the Alliance for Mature Americans with the more esteemed “AMA” (American Medical Association). Additionally, sales agents called themselves “Certified Trust Advisors” to appear as experts despite no formal training in estate planning. Conveying authority through title and professional dress is a common influence tactic (Cialdini, 2007).

Many of the sales tactics presented during the training are applicable to all age groups (e.g., emotional arousal, testimonial, flattery, reciprocity, and “landscaping”). Landscaping uses rhetorical questions to make consumers feel in control of the sales negotiation, when in fact the interaction is structured to benefit the sales representative at the consumers’ expense (FINRA, 2006). In addition to establishing a norm of reciprocity by offering favors, sales agents also requested small favors from clients. This “foot in the door” approach is effective because once targets agree to simple requests, they are subsequently more likely to comply with larger requests to appear consistent in their behavior (Freedman & Fraser, 1966).

The Consumer Fraud Research Group analyzed 600 undercover recordings of telemarketing calls to older fraud victims and found an average of 8.6 classic persuasion tactics per call (FINRA, 2006). This study found many of these tactics in Alliance’s sales training, including building rapport, establishing credibility, scapegoating, landscaping, and pressing the client’s emotional “hot buttons.” For Alliance, these tactics were designed to create a psychological ether where clients were unable to resist persuasion or suspect that they were being manipulated.

Implications

Educating consumers about fraud should move beyond improving financial literacy. Prevention materials should include identifying persuasion tactics and the signs that a business or product might be a sham (AARP Foundation, 2003; FINRA, 2006; Kerley & Copes, 2002). The Tricks of the Trade: A “How To” Guide to Scamming Older Adults section of this study could serve as a framework to help consumers enhance their persuasion knowledge to recognize high-pressure sales tactics and resist large purchases before verifying the credibility of the business or product. In fact, Alliance presenters told trainees to not bother soliciting the same person twice because clients who declined the first time around would not agree later on. Therefore, training older consumers to wait and evaluate before they agree to a purchase may reduce possible fraud.

Although there are no simple tools to differentiate the persuasion tactics used to market fraudulent products from the same tactics used to sell legitimate ones, providing information on where to report fraud is crucial. Studies show that individuals who are knowledgeable about reporting are less likely to be victimized and more likely to report if they are (Copes, Kerley, Mason, & Van Wyk, 2001). The United States Senate Special Committee on Aging recently launched a reporting hotline staffed by experienced fraud investigators to assist victims with complaints and refer them to the appropriate authorities (U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging, 2013). This universal hotline may help link incidents of fraud nationwide to identify where investigative and supportive resources should be allocated.

Recognizing that it is difficult to differentiate between legitimate transactions and cons, better screening tools for financial institutions should be developed. Bank staff should undergo mandated training to recognize uncharacteristic account activity and report suspicious transfers to law enforcement (Nerenberg, 2006). Like all adults, elders have the right to determine where and how to spend, invest, and save their money, so all fraud prevention mechanisms must balance elder autonomy with protection and supervision.

Combating fraud also requires a top-down prevention approach from government agencies. Increased oversight of the financial services and insurance industries is needed (AARP Foundation, 2003; GAO, 2012). Partnerships between law enforcement, financial institutions, adult protective services, and federal fraud agencies can improve efforts to track, apprehend, and prosecute individual scam artists and put large predatory organizations like Alliance out of business.

Finally, salespeople who actually believe in the products and services they market to consumers are far more effective than those who acknowledge using deception. Perhaps sales agents should have mandatory training in ethics and be informed of the liability in use of high-pressure sales tactics.

Conclusion

This study uses a unique source—a sales training transcript from a company that used deceptive sales practices to sell trusts and annuities—to shed light on how corporate scams are orchestrated. The thematic analysis shows how trainees were inoculated from the moral accountability of engaging in unethical sales practices using neutralization techniques and incentives. Although many of Alliance’s motivation and sales tactics were similar to those used to market legitimate products, their failure to disclose the risks, who benefits, and the normalization of deception ethically set them apart.

Alliance’s sales training workshop happened over a decade ago, yet these techniques are commonly practiced today (Daugherty, 2008). In some instances, after Alliance was put out of business, those who were trained as trust/annuity agents simply started their own organizations and continued to seek susceptible older adults through free lunch seminars, senior center presentations, and direct mail marketing. When applying the lessons learned here, it is important to recognize that fraud is a moving target that is becoming more sophisticated as the internet gradually replaces telephone and door-to-door solicitations (Anderson, 2012).

Future research is needed to identify the older consumers most vulnerable to high-pressure persuasion and how to enhance their persuasion coping skills (Friestad & Wright, 1994). Research on perpetrators that includes diverse perspectives on neutralization and indoctrination techniques can help identify areas where practitioners and policy makers can intercept and address scams at the operational level.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Harry R. Moody for his passion and encouragement to do this important qualitative work on consumer fraud.

References

- AARP Foundation. (2003). Off the hook: Reducing participation in telemarketing fraud. Conducted for the United States Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Washington, DC: Author; Retrieved from assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/consume/d17812_fraud.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K. (2012). Federal Trade Commission. Consumer fraud in the United States, 2011: The third FTC survey. Retrieved from http://www.ftc.gov/reports/consumer-fraud-united-states-2011-third-ftc-survey [Google Scholar]

- Boyle P. A. Yu L. Wilson R. S. Gamble K. Buchman A. S., & Bennet D. A. (2012). Poor decision-making is a consequence of cognitive decline among older persons without Alzheimer’s Disease or mild cognitive impairment. PLoS ONE, 7, e43647. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butrica B. A., Smith K. E., Iams H. M. (2012). This is not your parents’ retirement: Comparing retirement income across generations. Social Security Bulletin, 72, 37–58. Retrieved from http://libproxy.usc.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.libproxy.usc.edu/docview/929382401?accountid=14749 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. C., & Kirmani A (2000). Consumers’ use of persuasion knowledge: The effects of accessibility and cognitive capacity on perceptions of an influence agent. Journal of Consumer Research, 27, 69–83. doi:10.1086/314309 [Google Scholar]

- Castle E., Eisenberger N. I., Seeman T. E., Moons W. G., Boggero I. A., Grinblatt M. S., Taylor S. E. (2012). Neural and behavioral bases of age differences in perceptions of trust. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109, 20848–20852. doi:10.1073/pnas.1218518109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini R. B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Civil Discovery Act. (1986). Code of Civil Protection. Title 4: § 2016–2036.

- Conrad K. J. Iris M. Ridings J. W. Langley K., & Wilber K. H (2010). Self-report measure of financial exploitation of older adults. The Gerontologist, 50, 758–773. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copes H. Kerley K. R. Mason K., & Van Wyk J (2001). Reporting behavior of fraud victims and Black’s theory of law: An empirical assessment. Justice Quarterly, 18, 343–363. doi:10.1080/07418820100094931 [Google Scholar]

- Craik F. I. M., & Jennings J. M (1992). Human memory. In Craik F. I. M., Salthouse T. A. (Eds.), The handbook of aging and cognition (pp. 51–110). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano R., & Mitchell M. S (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31, 874–900. doi:10.1177/0149206305279602 [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty G. (2008). The latest schemes and scams. Consumer Reports Money Adviser, 5, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Deevy M. Lucich S., & Beals M (2012). Scams, schemes & swindles: A review of consumer financial fraud research. Stanford University: Financial Fraud Research Center at the Stanford Center on Longevity; Retrieved from http://longevity3.stanford.edu/blog/2012/11/19/scams-schemes-and-swindles-a-review-of-consumer-financial-fraud-research/ [Google Scholar]

- Denburg N. L. Cole C. A. Hernandez M. Yamada T. H. Tranel D. Bechara A., & Wallace R. B (2007). The orbitofrontal cortex, real-world decision making, and normal aging. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1121, 480–498. doi:10.1196/annals.1401.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X. Simon M. Rajan K., & Evans D. A (2011). Association of cognitive function and elder abuse in a community-dwelling population. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 32, 209–215. doi:10.1159/000334047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Trade Commission (FTC). (2010, May). Putting a lid on international scams: 10 tips for being a canny consumer (Publication No. FT 1.32:SCA 5/3). Retrieved from http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/gpo11282/gen22.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). (2006, May). Investor fraud study: Final report. NASD Investor Education Foundation and WISE Senior Services. The Consumer Fraud Research Group: Author; Retrieved from http://www.finrafoundation.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Freedman J. L., & Fraser S. C (1966). Compliance without pressure: The foot-in-the-door technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4, 195–202. doi:10.1037/h0023552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friestad M., & Wright P (1994). The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal of Consumer Research, 21, 1–31. doi:10.2307/2489738 [Google Scholar]

- Hasher L. Goldstein D., & Toppino T (1977). Frequency and the conference of referential validity. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 16, 107–112. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(77)80012-1 [Google Scholar]

- Kemp B. J., & Mosqueda L. A (2005). Elder financial abuse: An evaluation framework and supporting evidence. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53, 1123–1127. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53353.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerley K. R., & Copes H (2002). Personal fraud victims and their official responses to victimization. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 17, 19–35. doi:10.1007/BF02802859 [Google Scholar]

- Landis J. R., & Koch G. G (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159–174. doi:10.2307/2529310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marson D. C., & Sabatino C. P (2012). Financial capacity in an aging society. Generations, 36, 6–11. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1027217007?accountid=14749 [Google Scholar]

- Miles M. B. Huberman A. M., & Saldaña J (2013). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Nerenberg L. (2006). Communities respond to elder abuse. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 46, 5–33. doi:10.1300/J083v46n03_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuessel F. H. (1982). The language of ageism. The Gerontologist, 22, 273–276. doi:10.1093/geront/22.3.273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak K., & Shadel D (2011, March). AARP Foundation national fraud victim study. Washington, DC: AARP Foundation National; Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/money/scams-fraud/info-03-2011/fraud-victims-11.html [Google Scholar]

- Phillips D. M., & Stanton J. L (2004). Age-related differences in advertising: Recall and persuasion. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 13, 7–20. doi:10.1057/palgrave.it.5740128 [Google Scholar]

- Ruffman T. Murray J. Halberstadt J., & Vater T (2012). Age-related differences in deception. Psychology and Aging, 27, 543–549. doi:10.1037/a0023380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40, 437–453. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1987.tb00609.x [Google Scholar]

- Skurnik I. Yoon C. Park D. C., & Schwarz N (2005). How warnings about false claims become recommendations. Journal of Consumer Research, 31, 713–724. doi:10.1086/jcr.2005.31.issue-4 [Google Scholar]

- Sykes G., & Matza D (1957). Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. American Sociological Review, 22, 664–670. doi:10.2307/2089195 [Google Scholar]

- Titus R. M. Heinzelmann F., & Boyle J. M (1995). Victimization of persons by fraud. Crime & Delinquency, 41, 54–72. doi:10.1177/00111128795041001004 [Google Scholar]

- Triebel K. L., & Marson D. C (2012). The warning signs of diminished financial capacity in older adults. Generations, 36, 39–45. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1027217023?accountid=14749 [Google Scholar]

- Umphress E. E., & Bingham J. B (2011). When employees do bad things for good reasons: Examining unethical pro-organizational behaviors. Organization Science, 22, 621–640. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0559 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). (2012, November). Elder justice: National strategy needed to effectively combat elder financial exploitation (Publication No. GAO-13-110). Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-110 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging. (2013, November). Senate aging committee launches new anti-fraud hotline, enhanced website to assist seniors. (Press Release). Washington, DC: Author; Retrieved from http://www.aging.senate.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- Vitell S. J., & Grove S. J (1987). Marketing ethics and the techniques of neutralization. Journal of Business Ethics, 6, 433–438. doi:10.1007/BF00383285 [Google Scholar]