Abstract

Purpose of the Study:

Using an interpretive phenomenological approach, this study explored the meaning African American (AA) caregivers ascribed to the dementia-related changes in their care-recipients.

Design and Methods:

Data were gathered in this qualitative study with 22 in-depth interviews. Eleven AA caregivers for persons with dementia, living in the Pacific Northwestern United States, were interviewed twice. Four caregivers participated in an optional observation session.

Results:

Analysis based on the hermeneutic circle revealed that, for these caregivers, the dementia-related changes meant that they had to hang on to the care-recipients for as long as possible. Caregivers recognized that the valued care-recipients were changed, but still here and worthy of respect and compassion. Ancestral family values, shaped by historical oppression, appeared to influence these meanings.

Implications:

The results from this study suggest that AA caregivers tend to focus on the aspects of the care-recipients’ personalities that remain, rather than grieve the dementia-related losses. These findings have the potential to deepen gerontologists’ understanding of the AA caregiver experience. This, in turn, can facilitate effective caregiver decision making and coping.

Keywords: African American older adults, Caregiving—informal, Dementia, Qualitative research methods, Humanities

Over the last two decades, research in the United States with African American (AA) family caregivers for persons with dementia has found that these caregivers tend to fare well psychologically in the caregiver role. They tend to find more satisfaction in their role ( Sörensen & Pinquart, 2005 ) and feel less burdened ( Skarupski, McCann, Bienias, & Evans, 2009 ) and anxious ( Haley et al., 2004 ) than White caregivers. However, some studies also indicate that these caregivers may experience more grief prior to the death of their care-recipients ( Ross & Dagley, 2009 ) and tend to be less prepared for the death of their family member with dementia, placing them at higher risk for prolonged grief disorders ( Hebert, Dang, & Schulz, 2006 ; Owen, Goode, & Haley, 2001 ).

One aspect of the AA caregiver experience that is poorly understood is the meaning they ascribe to the dementia-related changes in their care-recipients. These changes (e.g., alterations in cognitive functioning and personality) can be perceived as losses. Boss (1988) terms this ambiguous loss because the loss of the personhood of care-recipients is asynchronous with physical death. We know from research with White care-recipients that a common response to ambiguous loss is grief prior to the death of the care-recipients, termed predeath grief ( Dupuis, 2002 ; Lindauer & Harvath, 2014 ). Predeath grief contributes to impaired caregiver physical health ( Walker & Pomeroy, 1997 ), depression ( Sanders & Adams, 2005 ), burden ( Holley & Mast, 2009 ), and prolonged grief after the death of a care-recipient ( Givens, Prigerson, Kiely, Shaffer, & Mitchell, 2011 ).

Our evolving knowledge of the loss experience for caregivers has, for the most part, lacked the voice of AA family caregivers. Only a few studies have assumed AA caregivers experience predeath grief and have included them in their investigations of this phenomenon ( Diwan, Hougham, & Sachs, 2009 ; Lindgren, Connelly, & Gaspar, 1999 ; Owen et al., 2001 ; Ross & Dagley, 2009 ). This work reveals conflicting evidence about the relevance of predeath grief to the AA caregiving experience. Therefore, in order to garner a broader perspective of their experience, we sought first to understand the meaning AA family caregivers ascribed to the dementia-related changes in their care-recipients and second, to explore their emotional responses to these changes.

Design and Methods

Interpretive phenomenology ( Benner, 1994 ; Crist & Tanner, 2003 ) was used to explore the meanings AA family caregivers gave to dementia-related changes in their care-recipients. This approach respects the hermeneutic orientation that the caregivers’ experiences are embedded in their everyday lives and shaped by their culture. Because they are situated in their own lives, the meanings caregivers ascribe to dementia-related changes and their reactions to these changes may in the background (taken for granted) and difficult to articulate ( Dreyfus & Wrathall, 2005 ). The goal of this study was to uncover the tacit meaning caregivers ascribed these changes.

This study was carried out by White researchers in the Pacific Northwestern part of the United States. Because the AA community is small in this region, there was concern that the research team lacked embodied knowledge of the community and family life of the participants. Thus, AA community members were asked to recommend to the lead investigator respected individuals who could act as study advisors. Two older AA women (one a businesswoman, the other, a nurse) were referred and agreed to function as a Community Advisory Committee (CAC). The CAC provided valuable background information and assisted with study design, recruitment, and analysis. They complied with Institutional Review Board (IRB) and privacy regulations.

Study Participants

The target population was AA family caregivers of persons with mild, moderate, or severe dementia in the Pacific Northwestern United States. Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants from the community. Because of the small number of AAs in the Pacific Northwest, inclusion criteria were purposely broad ( Table 1 ). Eleven caregiver contacts agreed to participate and three did not (one was ill, one was not a caregiver, and the third was White). Once enrolled, no caregivers dropped out of the study. A subsample of caregivers (4) agreed to take part in an optional observation session. Seven families agreed to take part in the observation sessions, but three canceled due to illnesses or busy schedules.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Study

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

|

• African American

• Family caregiver for person with dementia • Provides 4hr or more of care per month • Caregiver for at least 1 month • Over age 18 years • Speaks English • Lives within 50 miles of lead investigator |

• First-generation immigrant from outside United States |

| • Care-recipient is not an identified family member |

In order for the caregiver to be eligible, the care-recipient had to have dementia. The Alzheimer’s Association’s Criteria for all-cause dementia ( Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia Workgroup, 2010 ) were used to determine whether the care-recipient had dementia ( Table 2 ). Potential participants were interviewed over the phone by the lead investigator to see if they and their care-recipients met inclusion criteria. If there was diagnostic uncertainty, the lead investigator reviewed the case with the other investigators to determine eligibility; a team approach was used to make the final inclusion/exclusion decision.

Table 2.

Alzheimer’s Association’s Criteria for All-Cause Dementia a

| Cognitive and behavior changes which: |

| Interfere with work or social activities |

| Represent a decline from previous functioning |

| Are not explained by delirium or major psychotic disorder |

| Impaired ability to retain new information |

| Plus at least two of the following: |

| mpaired reasoning |

| mpaired visual–spatial skills |

| mpaired language skills |

| Personality change |

Note: a Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia Workgroup (2010).

At the first visit, the lead investigator reviewed the details of the study and caregivers signed the consent forms. If family chose to participate in the observation session, the care-recipients, or their authorized representatives, signed consent forms. This study received the university’s IRB approval.

Procedure

Two in-depth interviews were conducted with each study participant in a private location of their choosing, over a 6-week period. Four participants were observed once, between the interviews. Caregivers were reimbursed with $20 per interview to cover any caregiving costs incurred during the interviews.

Interviews

The lead investigator conducted all of the interviews and observation sessions. An interview guide was developed by the lead investigator with feedback from the research team and the CAC ( Table 3 ). During the interviews, caregivers were asked to tell stories about their experiences and to discuss how they understood and felt about the changes they witnessed. The emergent nature of the study design allowed for the evolution and alteration of questions throughout the data collection process ( Benner, 1994 ; Crist & Tanner, 2003 ). The interviews continued until thematic repetition was identified, indicating that data saturation was achieved. Saturation was apparent after the 10th participant was interviewed, but an 11th participant was enrolled to verify this. Interviews took between 35 and 90min, were digitally recorded, then professionally transcribed.

Table 3.

Examples of Interview Questions

| a. Please tell me about a typical day caring for your (care-recipient). |

| b. What’s life been like since you started caring for your (care-recipient)? |

| c. Please tell me a story about when you first noticed the changes in your (care-recipient). |

| d. What was it that made you wonder if your (care-recipient) had dementia? |

| e. Can you tell me what it means to you to see your (care-recipient) change? |

Observations

Building on Briggs and colleagues’ work (2003) , we used nonparticipant unstructured observations to deepen our understanding of the participants lived experiences. These sessions were conducted between the two interviews. The lead investigator met caregivers and care-recipients at a location of their choosing and asked them to engage in a familiar task (e.g., preparing a shopping list). Dimensions of the caregiver/care-recipient relationships not identified in interviews, such as the degree of care-recipient cognitive impairment, were revealed through observation. The interactions, tone, and nonverbal exchanges between caregivers and recipients were noted in field notes. No audio or video recordings were made during observation.

Analysis

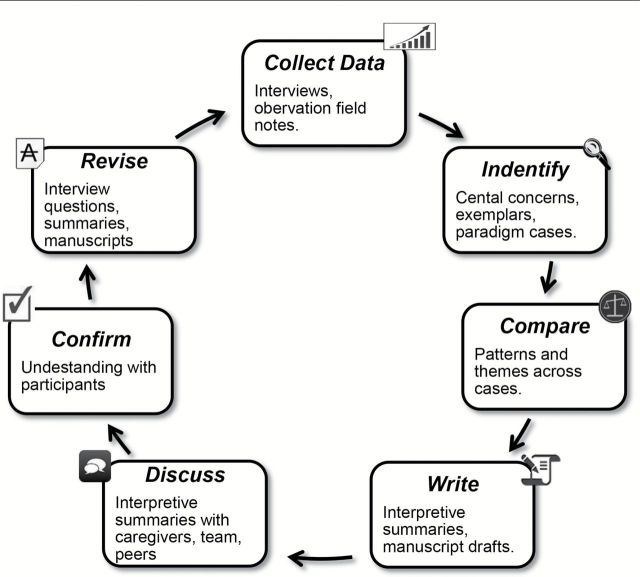

Analysis in interpretive phenomenology is based on the concept of the hermeneutic circle: an ongoing process of seeking understanding through interviewing, interpreting transcripts, and writing interpretive summaries from transcripts and field notes ( Figure 1 ). Through this process, paradigm cases and exemplars are identified. In this study, paradigm cases were compelling stories from individual caregivers which revealed the essence of dementia-related changes and reflected the meanings found in other cases. Exemplars were vivid sections of multiple interviews that highlighted the caregivers’ experiences ( Benner, 1994 ; Crist & Tanner, 2003 ).

Figure 1.

The interpretive phenomenological analysis approach. Adapted from Crist and Tanner (2003) and Benner (1994) .

Analysis of the interview transcripts and field notes began after the first interview and continued throughout data collection. Using the qualitative program Dedoose ( SocioCultural Research Consultants, 2014 ), themes from the transcripts and field notes were identified by the lead investigator, who then wrote interpretive summaries incorporating these themes. The transcripts and summaries were discussed amongst the research team members to identify paradigm and exemplar cases ( Crist & Tanner, 2003 ). During the second interviews with the caregivers, themes were reviewed to assess for authenticity. Themes were also discussed with peers and the CAC to clarify and validate the interpretations ( Lincoln & Guba, 1985 ).

Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) classic strategies for increasing trustworthiness of findings were used. First, the lead investigator volunteered in the community 2 years prior to study initiation (prolonged engagement). Second, interview data were triangulated with observation data, feedback from the CAC, and peer reviews. Third, participants were asked to review the themes identified in the first interviews to provide clarification.

Background

Key to an authentic understanding of this study’s findings is an appreciation for the historical legacy that influenced the caregivers’ experiences. In the early 1900s, despite exclusionary laws in the Pacific Northwestern Unites States, AAs gravitated to this region with the expansion of the railroad systems. Many of the first AAs in this region were “red caps,” gentleman who catered to the needs of White travelers on the trains ( Tuttle, 1990 ).

In the 1940s, the region’s population swelled when shipyards were built to produce ships for World War II. Due to the influx of workers, the AA population grew from 2,500 in 1940 to over 21,000 by 1945 in Oregon alone. Overcrowding was problematic and eased by the production of temporary housing, including the construction of Vanport, the largest wartime housing project in the United States. After the war, Vanport was devastated by a flood, forcing approximately 5,000 AA survivors into small metropolitan neighborhoods. The space available to these flood victims was constrained by the practice of forbidding purchase of housing by AAs anywhere outside tightly controlled neighborhood boundaries ( Taylor, 1981 ).

Caregivers in this study described the racial tensions of the time, noting that the local (White) citizens hoped the AA citizens would return to the South after the war. To this day, the caregivers in this study perceived this flood not as an act of nature, but as purposeful effort to “cleanse” the region of AAs.

The majority of the families in this study came from the South during the 1940s to work for (or near) the shipyards. The values of industriousness, primacy of family, and Christian faith ( Hill, 1999 ) were brought with these families and continue to be important to this day. Additionally, despite being far from the South, these families found racism in the Pacific Northwest. From an active Ku Klux Klan presence (25,000 members in Oregon in 1922; Chalmers, 1965 ) to the gentrification of today’s urban AA neighborhoods, these study participants and their families experienced both community acceptance and rejection in this “peculiar paradise” ( McLagen, 1980 , p. 2) in the Pacific Northwest.

Results

Demographics and Functional Status

The AA population in this region is small. In order to protect confidentiality, limited demographic information is provided ( Table 4 ). All the caregivers in this study were AA. All the care-recipients were AA with the exception of two White care-recipients. Nine of the care-recipients were biological family members (e.g., mothers) and two were fictive kin. All but two care-recipients lived with the caregivers.

Table 4.

Participant Demographics

| Average | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver age | 59 | 43–81 |

| Care-recipient age | 79 | 55–93 |

| Years caregiving | 6.5 | 2–13 |

| Hours caregiving/week | 30 | 4–84 |

Per caregiver report, most of the care-recipients had moderate to severe dementia. Behavioral symptoms included agitation, apathy, disinhibition, and wandering. Memory loss and impaired executive function were common. All of the care-recipients were dependent on others for meal preparation and needed help with bathing and toileting.

Overview

Broadly, we found that these AA caregivers perceived the dementia-related changes as relatively insignificant in the wider scheme of their lives and values. While themes of loss and burden were present, two more compelling themes stood out: hanging on and changed but still here . First, because the caregivers placed high value on their elder care-recipients, they worked to maintain their care-recipients’ current abilities and status in the family. Using the participants’ words, this theme was entitled hanging on . Second, the changes meant cognitive and functional decline and loss, but the caregivers appreciated the fact that the care-recipients were still present and respected members of the families. This theme was labeled changed, but still here .

A paradigm case was used to understand, interpret, and discuss key themes across the other cases ( Crist & Tanner, 2003 ). The paradigm case below illustrates the meaning one family gave to the dementia-related changes in their elder.

Paradigm Case

Two caregivers from the same family cared for their elder. To escape oppressive racial discrimination and economic hardship, the elder (as a young man) moved from the Southern United States to work in the Pacific Northwest shipyards. His family values from the South centered on putting the needs of family first and keeping families together. He maintained these values when raising his own family in the Pacific Northwest. When, as an older man, he began to lose his memory, his family directed its efforts to keeping him as “one of the team.” Everyone on the team had job, and the elder’s job was to “stay alive.” The dementia-related changes for this care-recipient (poor short-term memory, impaired executive function, word-finding difficulty, functional impairments) were of minor concern for this family. They saw him as “aging out” but they focused on keeping him healthy: “Even at his age, I think I could get his body toned a little better.” They felt that he “doesn’t seem to have health problems” and was “lucky” that he didn’t have cancer because cancer meant certain death, “…I don’t want to see him leave this earth at all.” They expressed worry and described feeling protective of him, yet they were grateful that he was still an active part of the family. What was important for them was that the elder could still spend time with the family and sustain his valuable role as “the Wise One,” telling family stories that kept the past connected with the present.

This paradigm case was identified as sharing common themes and experiences of others in this study. What was most meaningful for this family was not what had been lost, but rather, what had not been lost. Instead of focusing on the losses and decremental changes, the family in this paradigm case was hanging on to the elder they still had. They did not deny the fact that he had changed, but they were grateful for the fact that he was still here : “Yes, his memory is going. But I know he is still here…he still can talk to me.”

In the hermeneutic tradition, analysis and interpretation of the paradigm case provided insight to the meanings we identified in the other 10 cases. We found that most of the caregivers’ expressed thoughts, feelings and values similar to those in the paradigm case. Like the paradigm case, many of the caregivers felt some degree of challenge in their work. They seemed to live in the middle of a paradox: hanging on to what was still here , but grappling at the same time with burden and loss.

Hanging on

“Way back when…even in the struggles, and slavery, all we had is each other. So that’s why we hang on to each other.” This caregiver explained that the history of enslavement and oppression shaped these AA caregivers’ values. Specifically, the caregivers in our study placed high value on keeping the family together and hanging on to the elder with dementia for as long as possible. One caregiver explained this value: “…um, Black families tend to be more family oriented and closer in a lot of ways. So it might be harder for them to let go…”

Caregivers recognized that their care-recipients were losing function, and some even recognized that their care-recipients were close to the end of their lives, “I know that my mom may not live, be here forever.” For the most part, however, the caregivers worked to preserve the independence, dignity and personhood of their family member with dementia. Only one caregiver clearly did not express a need to hang on. This may have been because of the dyad’s tumultuous relationship, or the fact that they were fictive kin.

Like the paradigm case, caregivers used teamwork to hang on to their care-recipients. The teams listened to stories of the past, spent time in “fellowship” with the care-recipients, and dined out with them to keep them engaged and active. And while the caregivers were able to see that the dementia had caused decline, many of them did not seem particularly distressed by the changes. Instead, they expressed gratitude for what remained.

This is not to say the caregivers did not have a sense of burden, because many of them did. Caregivers spoke of feeling tired, “it just wears on you.” The emotional response to this burden was for most part, frustration. Caregivers reported feeling “flustrated,” [sic], “sad,” and “pissed.”

In interpretive phenomenology, important passages (exemplars) help explain a phenomenon ( Benner, 1994 ). The challenge of hanging on while at the same time feeling burdened is evident in the following exemplar in which the caregiver worked to maintain her care-recipient’s independence: “I give her night medicine…she sleeps through the night and then I’m back.” This caregiver felt that caregiving was her natural role: “…you’re taught this, you’re programmed for it. You just step into the role…yeah, it’s an easy thing to do.” She talked about her family member with affection, but when pressed, she discussed burden and loss of personal freedom, “Everything is lost to you… because you’re concentrating on that person and the only time you have some time off is when you just actually steal it, you have to take it.” This caregiver described managing her challenges with her faith: “We have faith that you will make it through this. You have faith that you can be healed….”

Other caregivers in this study also talked of this paradox—of feeling like they are fulfilling an important role for someone they cared deeply about, but also feeling burden and loss. Caregivers often turned to their faith to ameliorate their burden and help them maintain the vitality of their care-recipients, “I pray a lot and ask Him for guidance.” Like the caregivers in the paradigm case, they felt that God helped the caregivers hang on by protecting and blessing their care-recipients.

Despite the fact that many of the care-recipients were quite impaired, most caregivers didn’t focus on end-of-life concerns. They recognized that at some point the care-recipient would die (“Eventually something will happen…”), but for the most part, however, these caregivers directed their attention to the present “blessings.” They talked about “moments of joy,” “at least I have her,” and “I’m blessed because my mom is able to still talk.” For these caregivers, what was important was to keep the care-recipients healthy, safe, content, and, most importantly, to “keep your family together for as long as you can.”

Changed, but Still Here

The caregivers recognized the changes in their care-recipients, but they also emphasized that their care-recipients were still here and important members in family life. The majority of the caregivers pointed out the care-recipients were “still sharp,” “still ticking,” “still here,” and “still around.” Importantly, despite care-recipient decline, caregivers focused on the preserved capabilities (such as singing and story-telling) and personality traits (e.g., humor and compassion). The caregivers appeared to value the very presence of the care-recipients: “It’s a blessing to have her still here.”

Nonetheless, caregivers did acknowledge that their care-recipients were “slowing down,” “declining,” and “deteriorating,” that their personalities and functional abilities were changing with dementia progression. These changes often meant that the care-recipients were turning into children, that the caregivers were losing their care-recipients, or both.

Role change was not particularly evident in the paradigm case, but it was an important theme for other families, as one caregiver remarked: “it’s almost like they revert back to a kid.” The role changes meant that the caregivers adapted, but they were not overly distressed: “So now you gotta learn, need to do the things that she needs done now.” One caregiver explained their history prepared them to take care of each other:

…if you look back in slavery days…all we had was each other to keep each other going. From young to old, we took care of everyone. I think that’s what we had to do. We were there for the sick. We were there for the babies. We were there for the White people’s babies…I think it’s just the caring nature that’s just in us, that just passed from generation to generation.

Along with role change, several caregivers felt as though they were gradually losing the personhood of their care-recipients. As a consequence, they worried about their care-recipients and felt protective of them. In contrast with the paradigm case, some caregivers felt a deep sadness about the changes: “I sometimes sit here and I look at him in quiet moments…and I’m like, ‘What happened? Where are you?’”

Despite this sense of loss, these caregivers did not think of their care-recipients as gone (a term commonly used in the caregiver loss literature; e.g., Sanders & Corley, 2003 ). The following exemplar illustrates one daughter’s experience.

This daughter cared for her elder mother and recognized that she was losing function, but nonetheless felt her mother was “really blessed.” The daughter recognized that there were “some things she needs help with…” but did not feel as though she was gone: “…I talk to her every day and I’m going over there…every other day. I don’t feel like she is gone. But I do see her deteriorating.”

For this caregiver, and others in our study, the word gone was equated with death. These caregivers did not deny the fact that their care-recipients were changing, rather the word gone, in their eyes, did not apply to their situation. Because the caregivers did not think of their care-recipients as gone, the word grief wasn’t always relevant to them. Some caregivers stated clearly that they did not have a sense of grief about the changes in their care-recipients, but others were somewhat perplexed: “I don’t even know really what to call it. I don’t even know if it’s grief.”

As with the hanging on theme, these caregivers struggled with paradox. They felt as though they were losing someone that was, at the same time, still here . This paradox echoes Boss’s ambiguous loss theory, of feeling as though one is “there but not there” ( Boss et al., 1988 , p. 124). However, our caregivers seemed to put more emphasis on what was still here : “…she can still remember some things…she still has good days.” This emphasis on still here seemed to help caregivers appreciate what remained, despite the fact that the care-recipients were quite impaired.

Discussion

Our aim was to understand the meanings AA caregivers ascribed to dementia-related changes, and our findings revealed that, for these AA family caregivers, the changes resulted in a paradoxical experience. While theses caregivers tried to hang on to their care-recipients, they also realized that at some point, they would have to let go. And while they venerated what was still here , some were saddened by what was lost. This tension between hanging on and letting go, between recognizing what is still here but lost, may be explained by understanding the lens through which these caregivers viewed their lives and work.

Heidegger asserted that humans live within their own worlds that are made of entities such as culture, language and time. Often, the important influences and themes affecting daily life is taken-for-granted and not overt ( Dreyfus & Wrathall, 2005 ). Consistent with the interpretive phenomenological method, the caregivers and researchers unveiled the idea that their need to hang on to their care-recipients may have been influenced by ancestral African values of family cohesion and respect for the elders.

As the caregivers discussed their experiences, it became evident that many of them felt that ancestral slavery and oppression subtly shaped their present-day caregiving experiences. Caregivers commented on a range of historical factors which they felt affected their need to hang on to those that were still here . From slavery, Jim Crow laws, segregation, school integration, to subtle and not-so-subtle racism, the values of the primacy of the family, respect for elders ( Sudarkasa, 1997 ) were common and important themes for these caregivers.

The research team was interested in the theme of oppression in the context of the current time and thus the Community Advisory Committee 2014 (February 21) was consulted. These advisors noted that while the theme of separation is based in historical oppression, it is still important for many AA families. They explained:

You could have the best, tight-knit family…and the master could come and say, ‘I’m taking this person.’ You had nothing to say about it, there’s nothing you could do about it… And so if you could keep somebody for any length of time you kept them.

Our study findings are somewhat novel to the literature in that only a few papers could be found which address the meaning of dementia-related changes in relation to oppression in general and slavery specifically. Several authors maintained that that values of family primacy and cohesion were transported to the United States with the slave trade and helped AA families maintain kinship ties despite the trauma of separation during slavery ( Laurie & Neimeyer, 2010 ; Pollard, 1981 ; Sudarkasa, 1997 ), but the connection to caregiving in the literature is limited. Pollard (1981) , argued that African family values and slavery shaped AA’s “tenacious reverence for the aged” (p. 228). Dilworth-Anderson and Gibson (2002) noted that enduring hardships contributed to the strength of AA families, and more recently, DeGruy (2005) argued that “post-traumatic slave syndrome” (p. 13) continues to influence the fiber of AA life. The connection to oppression and caregiving may be specific to the caregivers in this study; however, the limited literature suggests that these issues continue to be relevant to the AA community in general.

Our study is one of few that addresses the meaning AA caregivers ascribe to dementia-related changes and links this meaning to oppression. Much of the literature addressing meaning focuses on White caregivers. This literature reveals that dementia-related changes can mean loss, stigma, and opportunity ( Lindauer & Harvath, 2015 ). While some papers touch on meaning and AA caregivers (e.g., Toth-Cohen, 2004 ), the relationship between caregiving and oppression is rarely explored.

We did find that our work aligned, to a degree, with Ikels’ (2002) who found that dementia in Chinese elders was of limited meaning to families. Instead, elders were highly valued because they had “abundant life force” (p. 236) that allowed them to live long lives. In both Ikels’ (2002) study and ours, it was apparent that the value of a person with dementia was determined not by his or her achievements in life, but by his status in the family—an elder worthy of respect ( Shweder & Bourne, 1982 ).

Ikels’s (2002) paper did not address loss, but loss was a subtle yet important theme in our study. In our study, only one caregiver’s experience was clearly defined by loss. For the others, while loss was recognized, it did not permeate their lives. Ambiguous loss, as discussed by Boss (1988) , did not fit with these caregivers’ experiences. For these caregivers, the unambiguous physical presence of the care-recipients ( still here ) protected the families from separation and seemed to ameliorate the psychic distress that Boss (1988) associates with psychological absence.

These findings vary somewhat from those discussed in the literature in which loss is a strong theme and caregivers reported feeling that the care-recipients were “gone” ( Sanders & Corley, 2003 , p. 46). However, as discussed above, our participants did not think of their care-recipients as gone , and did not think of themselves as grieving. This finding also contrasts with the literature that identifies predeath grief as an important caregiver reaction to dementia-related losses (e.g., Dupuis, 2002 ; Holley & Mast, 2009 ) and “an unavoidable component of caregiving” ( Ziemba & Lynch-Sauer, 2005 , p. 103).

Our study reveals that by focusing only on the losses associated with dementia and resulting predeath grief, we may be missing an important aspect of how AA caregivers make meaning of dementia in a family member. It was important to the caregivers in our study that we understood that they still held their elder care-recipients in high regard, worked to keep them present, and hoped that they would, “God willing…live to 100.” For them, dementia was not “a complex, unknowable world of doom, ageing, and a fate worse than death,” ( Zeilig, 2014 , p. 262) but a part of an elder’s journey. Through hanging on to the care-recipients who were still here , caregivers talked of “moments of joy,” and “blessings.” Losses were, in many cases, eclipsed by the caregivers’ ability to see what was still preserved of the care recipients’ valued personhood.

Implications

These findings have both clinical and research implications. From a clinical perspective, our study offers ample material which gerontologists can use to initiate sensitive conversations (e.g., end-of-life planning) with family caregivers about their experiences.

AA values about end-of-life care can vary from that of Whites ( Kwak & Haley, 2005 ). The caregivers in our study focused on hanging on to the care-recipient and this hints that they may have trouble letting go at the end of life. Owen et al. (2001) found that AA caregivers, in comparison to White caregivers, were less likely to accept a care-recipient’s death and more likely to perceive the death as a great loss. Hebert et al. (2006) found that the AA caregivers in their study were “not at all” (p. 687) prepared for the death of their care-recipients, resulting in higher complicated grief scores.

The caregivers in our study tended to speak of death as an event far in the future, “at some point she was will go…” Thus, it may be tempting to interpret their focus on what remains as a form of denial, but these caregivers seemed to have a realistic appreciation of the changes. However, their focus on what was still here might interfere with their ability to prepare for an inevitable death in the future.

Gerontologists can offer a valuable service to AA family caregivers by providing opportunities to talk about end-of-life concerns early in the dementia trajectory. Bass and Bowman (1991) found that these conversations prior to the death of a care-recipient are more helpful in assuaging postdeath distress than postdeath conversations.

The findings from this study also have implications for future research and suggest that scales commonly used to measure caregiver grief may not be valid for all AA caregivers. For example, the Marwit Meuser Caregiver Grief Index (MMCGI) ( Marwit & Meuser, 2002 ), has been used in studies to understand the predeath grief experience of caregivers for persons with dementia (e.g., Sanders & Adams, 2005 ). Of concern, some items on this measure may not be meaningful for AA caregivers. For example, “I have this empty, sick feeling knowing that my loved one is ‘gone’” ( Marwit & Meuser, 2002 , p. 726) may not be valid with these caregivers who recognized the word gone as applying to someone who is physically dead. “I feel I am losing my freedom” ( Marwit & Meuser, 2002 , p. 762) may not be an appropriate item for these descendants of enslavement. While McLennon et al. (2014) maintain the MMCGI has content and face validity for AA caregivers, they also noted that caregivers did not have any suggestions for changes to the MMCGI, indicating that more work is needed to validate these measures in the AA caregiver community ( DeVellis, 2012 ).

Strengths and Limitations

There were known cultural and racial differences between the investigators (White) and study participants (AA), which may have been a strength of this study. For example, the participants may have felt a need to educate the researchers about the AA experience ( Adamson & Donovan, 2002 ). Alternatively, the cultural divide could have been a limitation. The caregivers may not have felt comfortable talking about their feelings with a person of a different race ( Ochieng, 2010 ).

Another potential limitation is that many of the care-recipients did not have a formal diagnosis of dementia. We depended solely on caregiver report, and thus, there may have been inaccuracies.

Finally, even though the majority of the caregivers in this study were women, we did not explore their experiences through a feminist lens. It is possible they may have embodied the strong black woman schema, in which AA women a feel a need to suppress their own needs while they care for others ( Baker, Buchanan, Mingo, Roker, & Brown, 2015 ). Viewing the findings from this perspective may have revealed alternative themes, such as how these women understood their value and power within the family unit ( hooks, 1990 ).

Conclusion

This study offers a fresh, in-depth look into the AA caregiving experience by examining the meanings these caregivers in the Pacific Northwest ascribed to dementia-related changes. Through this work, we are able to more fully appreciate how the historical backdrop of slavery and oppression shaped their understanding of their care-recipients with dementia. This is not to say that this history directly informed their comprehension of, or reactions, to dementia-related changes. Rather, it seemed to subtly shape how they understood their experiences. The implications being that, in order to fully and effectively address the concerns of these caregivers (and any caregiver) one must consider the full complement of their “worlds”—the culture, language, history (and so forth) that defines who they—and we—are ( Dreyfus & Wrathall, 2005 , p. 46).

Funding

This work was supported by the OHSU Hartford Center for Geriatric Nursing Scholarship and the Hearst Foundation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Gertrude Rice and Ms. Carolyn Brown for their sage guidance and unfailing support. We also extend our heartfelt thanks to the caregivers who shared their time and wisdom with us. This study was conducted at the Oregon Health & Science University School of Nursing.

Acknowledgements to the Layton Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Center at Oregon Health & Science University for support of this study. Grant #AG008017.

References

- Adamson J., Donovan J. L . ( 2002. ). Research in black and white . Qualitative Health Research , 12 ( 6 ), 816 – 825 . doi: 10.1177/10432302012006008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia Workgroup . ( 2010. ). Criteria for dementia . Retrieved March 17, 2015 from http://www.alz.org/research/diagnostic_criteria/dementia_recommendations.pdf

- Baker T. A., Buchanan N. T., Mingo C. A., Roker R., Brown C. S . ( 2015. ). Reconceptualizing successful aging among Black women and the relevance of the strong Black woman archetype . The Gerontologist , 55 ( 1 ), 51 – 57 . doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass D. M. Bowman K. & Noelker L. S . ( 1991. ). The influence of caregiving and bereavement support on adjusting to an older relative’s death . The Gerontologist , 31 ( 1 ), 32 – 42 . doi: 10.1093/geront/31.1.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner P . ( 1994. ). The tradition and skill of interpretive phenomenology in studying health, illness, and caring practices . In Benner P. (Ed.), Interpretive Phenomenology: Embodiment, caring, and ethics in health and illness (pp. 99 – 127 ). Thousand Oaks, CA: : Sage; . doi: 10.4135/9781452204727.n6 [Google Scholar]

- Boss P., Caron W., Horbal J . ( 1988. ). Alzheimer’s disease and ambiguous loss . In Chilman C. S. Nunnally E. W. , & Cox F. M. (Eds.), Chronic illness and disability: Families in trouble series , volume2 (pp. 123 – 140 ). Thousand Oaks: : Sage; . doi: 10.1037/028583 [Google Scholar]

- Briggs K., Askham J., Norman I., Redfern S . ( 2003. ). Accomplishing care at home for people with dementia: using observational methodology . Qualitative Health Research , 13 , 268 – 280 . doi: 10.1177/1049732302239604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers D. M . ( 1965. ). Oregon: Puritanism replotted . Hooded Americanism: The first century of the Ku Klux Klan 1865–1965 (pp. 85 – 91 ). Garden City, New York: : Doubleday & Company, Inc; . doi: 10.2307/1908871 [Google Scholar]

- Community Advisory Committee . ( 2014. , February 21). An interview with C. Brown and G. Rice (Community Advisory Committee)/Interviewer Allison Lindauer. Oregon Health & Science University . Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Crist J. D., Tanner C. A . ( 2003. ). Interpretation/analysis methods in hermeneutic interpretive phenomenology . Nursing Research , 52 , 202 – 205 . doi: 10.1097/00006199-200305000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGruy J . ( 2005. ). Post traumatic slave syndrome: America’s legacy of enduring injury and healing . Portland, Oregon: : Joy DeGruy Publications, Inc; . [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis R. F . ( 2012. ). Validity . In DeVellis R. F. (Ed.), Scale development: Theory and applications ( 3 rd ed., pp. 59 – 72 ). Thousand Oaks, CA: : Sage; . doi: 10.2307/2075704 [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P., Gibson B. E . ( 2002. ). The cultural influence of values, norms, meanings, and perceptions in understanding dementia in ethnic minorities . Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders , 16 ( Suppl. 2 ), S56 – S63 . doi:10.1097/ 00002093-200200002-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diwan S., Hougham G. W., Sachs G. A . ( 2009. ). Chronological patterns and issues precipitating grieving over the course of caregiving among family caregivers of persons with dementia . Clinical Gerontologist , 32 , 358 – 370 . doi: 10.1080/07317110903110179 [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus H. L. , & Wrathall M. A . ( 2005. ). Martin Heidegger: An introduction to his thought, work, and life . In Dreyfus H. L. , & Wrathall M. A. (Eds.), A companion to Heidegger (pp. 1 – 15 ). Malden, MA: : Blackwell; . doi: 10.1111/b.9781405110921.2004.00001.x [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis S. L . ( 2002. ). Understanding ambiguous loss in the context of dementia care: Adult children’s perspectives . Journal of Gerontological Social Work , 37 , 93 – 115 . doi: 10.1300/J083v37n02_08 [Google Scholar]

- Givens J. L., Prigerson H. G., Kiely D. K., Shaffer M. L., Mitchell S. L . ( 2011. ). Grief among family members of nursing home residents with advanced dementia . The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry , 19 , 543 – 550 . doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31820dcbe0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley W. E., Gitlin L. N., Wisniewski S. R., Mahoney D. F., Coon D. W., Winter L., Ory M . ( 2004. ). Well-being, appraisal, and coping in African-American and Caucasian dementia caregivers: findings from the REACH study . Aging & Mental Health , 8 , 316 – 329 . doi: 10.1080/13607860410001728998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert R. S. Dang Q. , & Schulz R . ( 2006. ). Preparedness for the death of a loved one and mental health in bereaved caregivers of patients with dementia: Findings from the REACH study . Journal of Palliative Medicine , 9 , 683 – 693 . doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill R. B . ( 1999. ). The strengths of African American families: Twenty-five years later . Lanham, Maryland: : University Press of America, Inc; . [Google Scholar]

- Holley C. K., Mast B. T . ( 2009. ). The impact of anticipatory grief on caregiver burden in dementia caregivers . The Gerontologist , 49 , 388 – 396 . doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- hooks b . ( 1990. ). Homeplace: A site of resistance . In Hooks B. (Ed.), Yearning: Race, gender, and cultural politics (pp. 41 – 49 ). Boston, MA: : South End Press; . [Google Scholar]

- Ikels C . ( 2002. ). Constructing and deconstructing the self: dementia in China . Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology , 17 , 233 – 251 . doi: 10.1023/A:1021260611243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak J., Haley W. E . ( 2005. ). Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups . The Gerontologist , 45 , 634 – 641 . doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurie A., Neimeyer R. A . ( 2010. ). Of broken bonds and bondage: an analysis of loss in the Slave Narrative Collection . Death Studies , 34 , 221 – 256 . doi: 10.1080/07481180903559246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y. S. , & Guba E. G . ( 1985. ). Establishing trustworthiness . Naturalistic inquiry . (pp. 289 – 331 ). Beverly Hills: : Sage; . [Google Scholar]

- Lindauer A., Harvath T. A . ( 2015. ). The meanings caregivers ascribe to dementia-related changes in care recipients: a meta-ethnography . Research in Gerontological Nursing . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindauer A., Harvath T. A . ( 2014. ). Pre-death grief in the context of dementia caregiving: a concept analysis . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 70 , 2196 – 2207 . doi: 10.1111/jan.12411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren C. L., Connelly C. T., Gaspar H. L . ( 1999. ). Grief in spouse and children caregivers of dementia patients . Western Journal of Nursing Research , 21 , 521 – 537 . doi: 10.1177/01939459922044018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwit S. J., Meuser T. M . ( 2002. ). Development and initial validation of an inventory to assess grief in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease . The Gerontologist , 42 , 751 – 765 . doi: 10.1093/geront/42.6.751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLagen E . ( 1980. ). A peculiar paradise . Portland, OR: : The Georgian Press Company; . [Google Scholar]

- McLennon S. M., Bakas T., Habermann B., Meuser T. M . ( 2014. ). Content and face validity of the marwitmeuser caregiver grief inventory (short form) in African American caregivers . Death Studies , 38 , 365 – 373 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng B. M. N . ( 2010. ). “You know what I mean”: The ethical and methodological dilemmas and challenges for Black researchers interviewing Black families . Qualitative Health Research , 20 , 1725 – 1735 . doi: 10.1177/1049732310381085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J. E., Goode K. T., Haley W. E . ( 2001. ). End of life care and reactions to death in African-American and white family caregivers of relatives with Alzheimer’s disease . Omega , 43 , 349 – 361 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard L. J . ( 1981. ). Aging and slavery: gerontological perspective . The Journal of Negro History , 66 , 228 – 234 . doi: 10.2307/2716917 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A. , & Dagley J. C . ( 2009. ). An assessment of anticipatory grief as experienced by family caregivers of individuals with dementia . Alzheimer’s Care Today , 10 , 8 – 21 . doi: 10.1097/ACQ.0b013e318197427a [Google Scholar]

- Sanders S., Adams K. B . ( 2005. ). Grief reactions and depression in caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease: results from a pilot study in an urban setting . Health & Social Work , 30 , 287 – 295 . doi: 10.1093/hsw/30.4.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders S., Corley C. S . ( 2003. ). Are they grieving? A qualitative analysis examining grief in caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease . Social Work in Health Care , 37 , 35 – 53 . doi: 10.1300/J010v37n03_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shweder R. A. , & Bourne E. J . ( 1982. ). Does the concept of person vary cross-culturally? In White G. M. , & Marsella A. J. (Eds.), Cultural conceptions of mental health and therapy (pp. 97 – 136 ). Dordrecht, Holland: : D. Reidel Publishing Company; . doi: 10.1007/978-94-010-9220-3 [Google Scholar]

- Skarupski K. A., McCann J. J., Bienias J. L., Evans D. A . ( 2009. ). Race differences in emotional adaptation of family caregivers . Aging & Mental Health , 13 , 715 – 724 . doi: 10.1080/13607860902845582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SocioCultural Research Consultants . ( 2014. ). Dedoose Version 4.11, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data . Los Angeles, CA: . [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen S., Pinquart M . ( 2005. ). Racial and ethnic differences in the relationship of caregiving stressors, resources, and sociodemographic variables to caregiver depression and perceived physical health . Aging & Mental Health , 9 , 482 – 495 . doi: 10.1080/13607860500142796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarkasa N . ( 1997. ). African American families and family values . In McAdoo H. P. (Ed.), Black families ( 3rd ed., pp. 9 – 40 ). Thousand Oaks, CA: : Sage; . [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Q . ( 1981. ). The great migration: The Afro-American communities of Seattle and Portland during the 1940s . Arizona and the West: A Quarterly Journal of History , 23 , 116 – 126 . [Google Scholar]

- Toth-Cohen S . ( 2004. ). Factors influencing appraisal of upset in black caregivers of persons with Alzheimer disease and related dementias . Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders , 18 , 247 – 255 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle J . ( 1990. ). In Lindsay J. (Ed.), Local Color . Portland, Oregon: : Oregon Public Broadcasting; . [Google Scholar]

- Walker R. J., Pomeroy E. C . ( 1997. ). The impact of anticipatory grief on caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease . Home Health Care Services Quarterly , 16 , 55 – 76 . doi: 10.1300/J027v16n01_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilig H . ( 2014. ). Dementia as a cultural metaphor . The Gerontologist , 54 , 258 – 267 . doi: 10.1093/geront/gns203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemba R. A., Lynch-Sauer J. M . ( 2005. ). Preparedness for taking care of elderly parents:”first, you get ready to cry” . Journal of Women & Aging , 17 , 99 – 113 . doi: 10.1300/J074v17 n01_08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]