Abstract

Vandana Gurnani and colleagues report an analysis from the Intensified Mission Indradhanush strategy in India, showing that cross-sectoral participation can contribute to improved vaccination coverage of children at high risk

India’s immunisation programme is the largest in the world, with annual cohorts of around 26.7 million infants and 30 million pregnant women.1 Despite steady progress, routine childhood vaccination coverage has been slow to rise. An estimated 38% of children failed to receive all basic vaccines in the first year of life in 2016.2 3 4 The factors limiting vaccination coverage include large mobile and isolated populations that are difficult to reach, and low demand from underinformed and misinformed populations who fear side effects and are influenced by anti-vaccination messages.5 6 7

Owing to low childhood vaccination coverage, India’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare launched Mission Indradhanush (MI) in 2014, to target underserved, vulnerable, resistant, and inaccessible populations.8 The programme ran between April 2015 and July 2017, vaccinating around 25.5 million children and 6.9 million pregnant women. This contributed to an increase of 6.7% in full immunisation coverage (7.9% in rural areas and 3.1% in urban areas) after the first two phases.9 In October 2017, the prime minister of India launched Intensified Mission Indradhanush (IMI)—an ambitious plan to accelerate progress. It aimed to reach 90% full immunisation coverage in districts and urban areas with persistently low levels.10 IMI was built on MI, using additional strategies to reach populations at high risk, by involving sectors other than health (table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of the programme used by Mission Indradhanush (MI) and Intensified Mission Indradhanush (IMI)

| Mission Indradhanush (MI): April 2015 to July 2017 | Intensified Mission Indradhanush (IMI): October 2017 to January 2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Fully immunise 90% of infants by 2020 | Fully immunise 90% of infants by 2018 |

| Leadership | Central health minister and secretary of Health and Family Welfare, monitored under the proactive governance and timely implementation system | Prime minister, central health minister and cabinet secretary, monitored under the proactive governance and timely implementation system |

| Implementation | Ministry of Health and Ministry of Women and Child Development | Ministry of Health with support from 12 non-health ministries, including Ministry of Women and Child Development |

| Selection criteria | Districts with lowest coverage and state priority: lowest coverage (n=201), intermediate coverage (n=296), and other districts (n=31) | Districts and areas which continued to underperform after the first mission (<70% coverage) and >13 000 missed/partially immunised children |

| Target areas | 528 districts across 35 states | 173 districts (including 52 districts from northeastern states) and 17 urban areas across 24 states |

| Period | Four phases, each consisting of four monthly rounds, with each round lasting for 1 week | One phase with four monthly rounds, each round lasting for 1 week |

| Programme approach | • Improved microplanning, monitoring, social mobilisation and strengthened vaccination systems (especially in areas with inadequate staff numbers) • All vaccines under routine immunisation offered for children aged ≤2 years and pregnant women |

MI approach plus: • Rigorous head counts (validated by supervisors) for tracking and updating due lists to identify children aged ≤2 years and pregnant women for vaccination • More intensive planning and monitoring in hard to reach urban areas • Involving non-health sectors to deal with social barriers and gaps in knowledge in communities—and to create a vaccination “movement” • Additional financial support based on need, and flexibility in use of the fund |

This case study was led and coordinated by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The primary objective was to record the lessons learnt from IMI. Emphasis was put on understanding how cross-sectoral and multistakeholder engagement work to strengthen access to vaccine services and improve their quality. A modified multistakeholder review process was used, which included in-depth interviews of stakeholders at all levels and a synthesis meeting (see suppl 1 on bmj.com ).

Intensified Mission Indradhanush: programme description

Programme focus

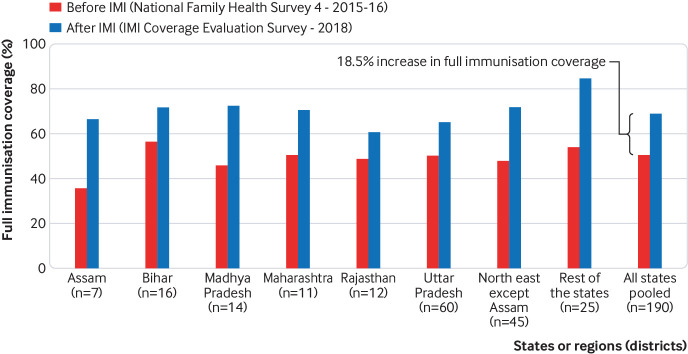

IMI targeted areas with higher rates of unimmunised children and immunisation dropouts. Updated data were used to select districts and urban areas in which at least 13 000 children were estimated to have missed diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis 3 (DPT3)/pentavalent 3 in the previous year, or DPT3/pentavalent 3 coverage was estimated to be <70%.11 These criteria were used to select the weakest 121 districts, 17 urban areas, and an additional 52 districts in the northeastern states (fig 1). All children aged up to 5 years and pregnant women were targeted, with a focus on ensuring full vaccination for children under 2 years. Vaccines included in the routine immunisation schedule were given—namely, tetanus toxoid for pregnant women based on their vaccination status; and for infants, Bacillus Calmette–Guerin, oral polio vaccine and hepatitis B at birth or first contact after birth, three doses of pentavalent, oral polio vaccine and injectable polio vaccine between 6 and 14 weeks, measles or combined measles and rubella vaccine at 9 and 18 months, and DPT and oral polio vaccine boosters at 18 months. Three doses of rotavirus, pneumococcal conjugate, and Japanese encephalitis vaccines were also given between 6 and 14 weeks in areas where these had been added to the routine schedule. A chain of support was established from the national level through states to districts. Senior staff provided regular reviews of progress and received updates on progress.10

Fig 1.

Map of the 121 districts, 52 northeastern districts, and 17 urban areas identified for Intensified Mission Indradhanush Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India 10

Implementation

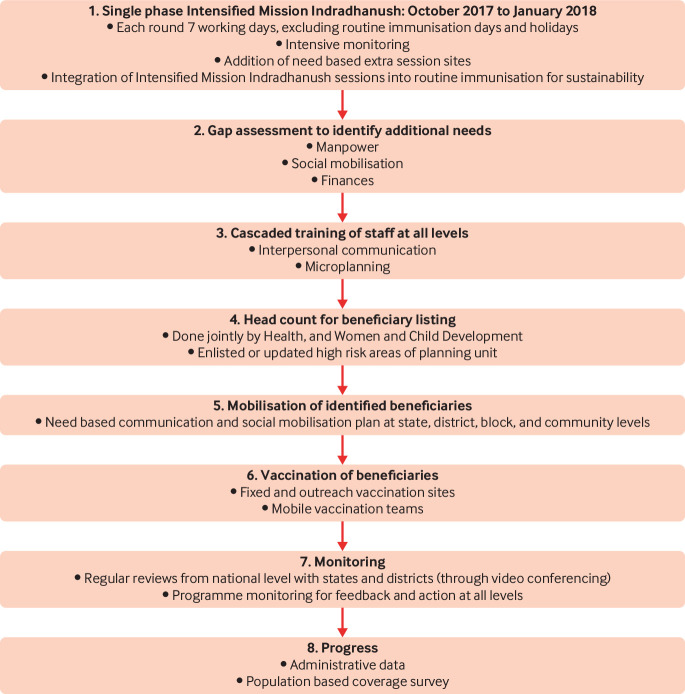

A seven step process was developed to support district and subdistrict planning and implementation of IMI, with staff at all levels receiving training (fig 2).10 Door-to-door headcount surveys and due listing of beneficiaries were conducted by facility staff (auxiliary nurse midwives), community based workers (accredited social health activists), and non-health workers (Anganwadi workers), and validated by supervisors for completeness and quality. Session micro-planning identified new sites for conducting vaccination sessions if needed, organised mobile teams for remote areas, and ensured that supplies were available. If too few staff were available at health subcentres, additional staff were hired or brought in from other areas. Vaccine supplies were tracked using the Electronic Vaccine Intelligence Network and cold chain tracking programme, and distributed using the alternate vaccine delivery mechanism.12 To facilitate local implementation, flexible vaccination funds were used for personnel costs, incentives for staff, transportation, social mobilisation, and production of communication materials. Guidelines for requesting additional resources and their allocation for specific activities were developed; additional funds were provided on demand to states.13 District task forces bought 12 non-health sectors together to devise and apply specific communication plans and materials. Cycles of immunisation were conducted each month between October 2017 and January 2018, each lasting 7 working days.

Fig 2.

Strategy for Intensified Mission Indradhanush Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India 10

Involvement of stakeholders in non-health sectors

IMI was an effort to shift routine immunisation into a Jan Andolan, meaning “peoples’ movement” in Hindi. It aimed to mobilise communities and simultaneously deal with barriers to seeking vaccines.

Nationally, coordination between health and 12 non-health ministries was facilitated by the prime minister’s office and cabinet secretariat. Non-health sectors included the Ministries of Women and Child Development; Panchayati Raj (a system of governance based at rural community level); Minority Affairs; Human Resource Development; and Information and Broadcasting. The Ministries of Urban Development, Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation were collaborators in urban areas. The Ministries of Defence, Home Affairs, Sports and Youth Affairs, Railways, and Labour and Employment supported specific activities, such as expanding service delivery points and transportation of supplies to the last mile. Youth organisations such as the National Cadet Corps and National Service Scheme were asked to provide support for social mobilisation by national and state administrators. Standard operating procedures for their involvement were developed for these organisations.14 In the districts, participation was coordinated by the district magistrate through a district task force team. In subdistricts, direct interaction between field workers from health and other departments was the rule.

Stakeholder mapping was conducted to identify available resources, which varied between districts and communities. In most communities, facility based staff, such as auxiliary nurse midwives, and community based staff, such as accredited social health activists and Anganwadi workers, were available for health education and coordination with other local participants. These included non-health government departments, non-governmental organisations, religious leaders, mothers’ groups, community and political leaders, private medical providers, and others. The support provided depended on local needs and the area covered by the stakeholders. It usually focused on education of women and families and mobilisation for vaccination sessions, and dispelling concerns about the adverse effects of vaccines.

Monitoring and evaluating progress

Vaccination sessions were monitored. Administrative data collected by auxiliary nurse midwives were transmitted through the routine health management information system. External monitoring was carried out by supervisors, and assessments of small samples of households were made to validate childhood vaccination coverage. E-dashboards on mobile phones were used to collect monitoring data, which allowed real time aggregation of vaccination data. Local monitoring was carried out by auxiliary nurse midwife supervisors, district supervisors, and medical officers, with support from WHO and Unicef monitors. During vaccination rounds, daily supervisor meetings reviewed the available data and discussed problems and solutions. External supervision was provided by national, state, and partner monitors, who met to review progress and provide feedback to all. Population based evaluation surveys of household coverage were conducted in April and June 2018 in IMI areas by WHO and the United Nations Development Programme.

Summary of progress

Administrative data on IMI remain provisional. We report here internal analyses that have not yet been published. Administrative data estimate that between October 2017 and January 2018, 97 628 vaccination sessions were conducted in IMI areas, delivering over 15 million antigens. During this period, an estimated 5.95 million children were vaccinated, with around 850 000 children being vaccinated for the first time and 1.4 million children aged ≥12 months being fully vaccinated. An estimated 1.18 million pregnant women were also vaccinated, with over 660 000 thought to have been fully vaccinated (internal communication, deputy commissioner (immunisation), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India). Vaccine monitoring internal data, show that vaccine and lack of stock were uncommon during the IMI period, with 98% of monitored sites having adequate supplies.15 Eleven states distributed additional funding for IMI rounds, estimated to be a total of $7.8 million (internal communication, deputy commissioner (immunisation), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India). All funds were provided by the National Health Mission of the government of India.

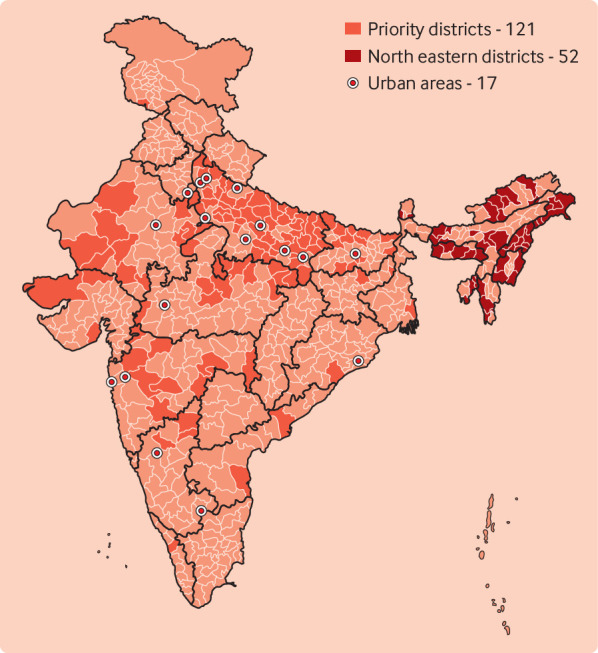

Population based coverage surveys were conducted in 190 IMI districts, 3–5 months after the last IMI cycle. The unit of analysis was the district. A total of 84 497 households were selected from 190 districts using probability proportionate to size cluster sampling. Estimates of coverage before IMI came from a national population based randomised cluster survey conducted in MI districts after the first two rounds in 2015-16, which included all IMI districts4 (see suppl 2 on bmj.com). The 2015-16 survey estimated full immunisation coverage for children aged 12-23 months to be 50.5% in IMI districts and 62% for India as a whole.

After IMI, the proportion of children with full immunisation coverage in IMI districts was estimated to be 69%, representing an increase of 18.5% from pre-IMI estimates (fig 3).4 16 Improvement in full immunisation coverage within IMI districts ranged from 12% in Rajasthan to 31% in Assam. Full coverage increased by >30% in 56 districts of the 190 districts surveyed (29.5%), by 10-30% in 83 districts (43.7%), and by <10% in 51 districts (26.8%)4 16 (see suppl 2 on bmj.com for data and confidence intervals by state and district). Since baseline survey data were collected in late 2015 and early 2016, new coverage estimates will be influenced by the last two phases of MI, which ended in July 2017. Changes in coverage cannot therefore be attributed solely to IMI. In addition, since there is no comparison population, the relative effect of IMI on immunisation coverage compared with the non-intervention population is unknown.

Fig 3.

Proportion of children aged 12-23 months fully immunised in 190 Intensified Mission Indradhanush (IMI) districts, by state or region before and after IMI

Routine monitoring was conducted for 98% of sessions, with headcount lists available in 92%, and updated due lists in 82% (internal communication, deputy commissioner (immunisation), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; see suppl 2 on bmj.com for process monitoring data by state). Due lists of eligible beneficiaries, comprising unimmunised and partially immunised children under 2 years and pregnant women, were created using door-to-door head counts in each targeted area—usually a village or urban unit. Of those on the due lists, an average of 57% (range 13-95%) received the needed vaccinations during sessions.

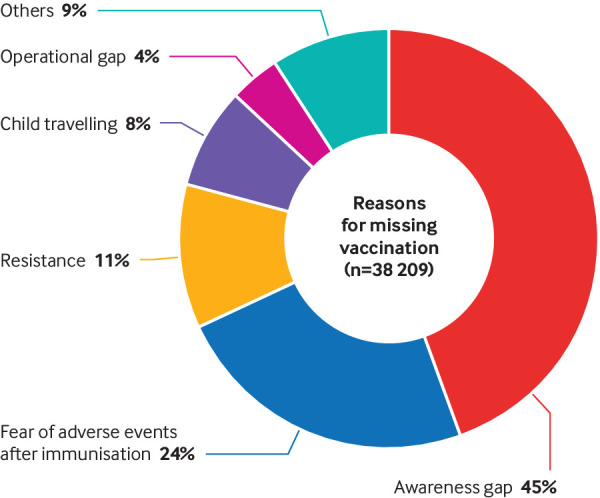

External monitors conducted household interviews of a sample of undervaccinated children in IMI districts as part of routine programme monitoring. Reasons for non-vaccination included lack of awareness (45%), apprehension about adverse events (24%), vaccine resistance (reluctance to receive the vaccine for reasons other than fear of adverse events) (11%), child travelling (8%), and programme related gaps (4%) (fig 4) (internal communication, deputy commissioner (immunisation), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India). Apprehension about adverse events and programme related gaps fell, from 31% and 12%, respectively, compared with routine monitoring data from the same districts before IMI.

Fig 4.

Reasons for missing vaccination sessions obtained by routine monitoring interviews with care givers of undervaccinated children between October 2017 and February 2018

These data show that more needs to be done to educate beneficiaries, dispel misinformation, and mobilise some households.

Systems factors associated with effective cross-sectoral involvement

Political support and data based targeting

Close involvement and supervision by the prime minister of India was important for generating and sustaining political will for IMI. It ensured the commitment of non-health government and non-government staff at all levels and promoted cross-sectoral involvement. Ministries of 12 other sectors were invited to participate and informed of IMI objectives and their roles. The prime minister sent letters to chief ministers stating the goal of 90% full immunisation coverage in their states, advised on engagement of non-health ministries, and participated in IMI review meetings. The use of data based criteria meant that all stakeholders understood the rationale for selection of focus areas. Intensive microplanning, using the “Reaching Every District” strategy helped to emphasise the need to reach all sections of communities and promoted participation of other sectors.17 No new structures or governance models were established; building on routine systems and mechanisms already in place allowed rapid uptake.

Decentralisation of management to district levels

To encourage the participation of non-health sectors and development partners, a lead partner was identified in every district. The responsibility for managing IMI was passed on to the districts and subdistricts, which developed plans tailored to local circumstances. District magistrates and immunisation officers took responsibility for mobilising health and non-health sector resources to fill staffing gaps, improve communication, and increase community mobilisation for vaccinations. This approach was effective when staff were motivated, and when additional funds or incentive payments were available. It was less effective in areas that were short staffed and when incentive payments were delayed. Key informants in two areas reported delays in staff payments due to district administrative and procedural weaknesses. This may also have slowed deployment of staff and other activities. In addition, the staff time commitment sometimes required temporary transfer to underserved areas, taking staff away from routine duties:

“There is no need of IMI if all ANM [auxiliary nurse midwife] posts are filled. Politics is spoiling routine immunisation because a few blocks have surplus ANMs whereas some do not have a single ANM. This is for political reasons” District stakeholder, Bihar; July 2018

Both states and districts were concerned about the long term sustainability of this approach.

“There will be no sustainability of these processes, because it is so intense. The focus should be on strengthening the routine immunisation including microplanning, monitoring and supervision” State stakeholder, Madhya Pradesh; July 2018

Household listing to improve reach

Detailed microplanning and listing of beneficiaries (creating due lists) was at the heart of the IMI approach, essential for reaching high-risk populations, and carried out for most sessions (see table 3 in suppl 2 on bmj.com ). Achieving household listing was central to the roles of auxiliary nurse midwives, accredited social health activists, and Anganwadi workers and where all were available and motivated this was feasible. However, household listing was difficult, particularly in districts with staff shortages and in urban areas. In these cases, staff from outside the district and locally available nursing students were used to support door-to-door household listing and other IMI activities using IMI funds. In addition to additional staffing needs, household listing in more remote areas required substantial time, innovation, and transportation. Field staff found that household beneficiary lists needed monthly updating because of frequent population shifts. In some areas, therefore, the household listing was probably incomplete, thus reducing coverage. To improve reach, all districts will need to provide adequate staffing to enable household listing and targeting to work.

Social mobilisation to improve access and equity

In subdistricts, local stakeholders were central to mobilising families and communities for vaccination sessions (table 2). They used a range of measures to provide information, mobilise communities for vaccination, and to discredit myths or rumours about vaccinations. In many areas, a wide range of partners were mobilised to contribute. Several mechanisms were used to involve families; social media platforms provided information about vaccination days, about the benefits of immunisation, and dispelled fears. Ration dealers, who provide government subsidised food and other supplies, were a source of information. Elected community leaders and religious leaders gave information during routine meetings or weekly religious gatherings.

Table 2.

Summary of effective strategies and the challenges of multisectoral collaboration for Intensified Mission Indradhanush (IMI)

| Strategies identified as important | Challenges | |

|---|---|---|

| Improved links between health and non-health sectors | • Joint meetings between field staff from various sectors to plan strategies, roles, and responsibilities • Household reminder slips about IMI sessions • Mobile immunisation teams; sessions held at convenient times and places • Providing prompt medical care for adverse events • Team home visits – auxiliary nurse midwives, workers from non-health sectors and community stakeholders to improve acceptance and reduce hostility |

• Inadequate infrastructure for new session sites • Inadequate manpower and lack of engagement of the community stakeholders to do household listing in their own areas • Suboptimal partner participation and cooperation when not involved in planning, consulted on their roles and availability • Limited recognition for non-health collaborators |

| Engagement of influencers | • Involvement of religious leaders to dispel fears and instil confidence in vaccination • Youth groups: awareness generation and mobilisation • Community political leaders: public endorsement • Prabhat pheri (morning rallies): school children and youth cadets • School promotion: teachers and students to mothers and families |

• Continued concerns about circulation of misinformation about vaccines and rumours about adverse events; conspiracy theories including vaccines causing sterilisation |

| Better use of local communities and institutions | • Peer counselling: mothers of fully immunised children counsel care givers of non-immunised children • Vikas Mitras and Tola Mitras–community level link workers—mobilised marginalised communities and helped to set up additional IMI sessions for Mahadalit (marginalised and extremely vulnerable caste groups) • Ration dealers used for mobilisation and to provide information |

• Requests by some community workers and groups for incentives/payments • Financial shortfalls for social mobilisation and information, education, and communication activities in some areas • Youth groups and Rotary participation limited to urban areas • Grievances about the food ration system led some families with distrust of government to resist vaccinations |

| Improved messaging | • Distribution of brochures, stickers, buttons, umbrellas, public announcements • Use of print and electronic media: joint media briefings by government and partners • Use of social media • Productions by the song and drama division (Ministry of Information and Broadcasting) • Street plays • Baby shows with prizes for healthy, fully immunised children |

• Limited competency of community health workers in communication and mobilisation (soft skills) so that concerns were nor always identified and dealt with • Accurate information not always provided about adverse events after immunisation; further work needed to dispel false perceptions about immunisation and improve vaccine seeking through social mobilisation campaigns |

However, process monitoring data showed that many eligible children on due lists were not brought to vaccination sessions. For those not attending, the key reason for almost half was lack of awareness, and for another quarter, concerns about the adverse effects of vaccines. This suggests that mobilisation activities were inadequate in changing the attitudes of some care givers. Gaps fall into four main areas. Firstly, inadequate communication plans, messages, and materials. False beliefs, such as rumours about adverse events or vaccines causing sterilisation, were often not targeted:

“There were rumours circulated on social media, especially on WhatsApp about immunisation and the Naturopaths played a big role in creating hurdles in implementation of IMI.” District stakeholder, Kerala; July 2018

Vaccine hesitancy was an important challenge during the previous measles rubella campaign and the polio eradication programme.18 19 20 Resistance to vaccination tends to occur in pockets of the population, reinforced by local social and community connections.21 Better understanding of the roots of false beliefs and how they are reinforced in communities will be essential to combating them:

“There are two types of refusal here: one group believes that vaccines are not important. They listen to us and then say that we understand what you say, but we don’t want [it]. The other group are in the anti-medication faith group: they believe disease is a result of sin and that vaccines are not needed by the faithful.” State stakeholder, Meghalaya; July 2018

Secondly, influential community personnel and partners did not always play an active part in community mobilisation. This was more likely in areas where they were not involved in early planning, not clear about their roles, or not provided with the means of communication. In some cases, this was reported to be due to a lack of recognition and financial incentives. Thirdly, community health workers in several areas reported that inadequate time and skills limited their ability to provide effective counselling. Fourthly, in some cases, sites chosen for additional IMI vaccination sessions (including private homes, businesses, and schools) had inadequate toilets, and other facilities, which might have discouraged attendance.

Building a sustainable system using experience from IMI

IMI has contributed to significant increases in fully immunised children (from 50.5% to 69.0%) in 190 of the lowest performing districts in India, a 37% increase in coverage over baseline. It was financed solely by the government, using existing staff and governance systems. IMI showed that cross-sectoral participation can be effective in vaccinating those children at highest risk. However, a number of system and practice changes, particularly in communication, are needed for this approach to be even more effective.

Four areas need strengthening. Firstly, sustained high level political support, advocacy, and supervision across sectors, and the flexibility to allocate finance and people where needed, is essential. Secondly, all districts must strengthen staff capacity to list household beneficiaries, add additional vaccination sites to improve access, and invest in the transportation required for both. Thirdly, better communication and counselling skills, tailored to local beliefs, are needed by community providers in health and partner sectors. Fourthly, districts and primary care facilities must work more effectively with non-health stakeholders across sectors by involving them early in planning and communication strategies. All sectors are willing to support immunisation programming, provided that their roles are clearly defined, predictable, and feasible with partner resources.

To meet sustainable development goals, there is strong political commitment to health in India, including the vaccination system. Investments in new vaccines and universal healthcare are imminent. IMI will play a role in reaching vulnerable populations in the short to medium term. Repeat IMI rounds in 75 lagging districts are planned from October 2018 onwards, incorporating experience from the early rounds. A campaign focused on village empowerment and development (Gram Swaraj Abhiyan and Extended Gram Swaraj Abhiyan), led by the Ministry of Rural Development, will also introduce IMI as one component of a multisectoral development effort.21 22

In the longer term, it is hoped that the lessons learnt from IMI will be incorporated into routine programming and overall development, with cross-sectoral participation leading to a people’s movement (Jan Andolan), for reducing vaccination inequities through social change.

Key messages.

The Intensified Mission Indradhanush strategy showed that cross-sectoral participation can increase vaccination rates in children at high risk

Strengthening of the system and practice changes could make it more effective

Sustained high level political support, advocacy, and supervision across sectors, together with flexibility to re-allocate financial resources and staff were essential for success

Districts must strengthen staff capacity to list household beneficiaries, add additional vaccination sites, and invest in the transportation required for both

Better communication and counselling skills tailored to local beliefs are needed to deal with barriers to seeking vaccinations

Districts and primary care facilities work must more effectively with non-health stakeholders by involving them early in logistics planning, communication, and messaging strategies

Acknowledgments

We thank the technical experts from development partners (WHO, Unicef, United Nations Development Programme) and the Immunisation Technical Support Unit; leadership and staff in health and partner ministries and departments at district and state levels; and the technical experts from various medical colleges: Rajib Dasgupta, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi; Anand Prakash Dubey, ESI-Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, New Delhi; Pragya Sharma and Raghavendra Singh, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi; Mubashir Angolkar, J N Medical College, Belagavi, Karnataka; Muneer Masssodi and S Muhammad Salim Khan, Government Medical College, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir; Harish Pemde, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi; Pankaj Jain, U.P. Rural Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Etawah, Uttar Pradesh; Satinder Aneja, School of Medical Sciences and Research, Sharda University, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh; Sanjay K Rai and Kiran Goswami, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi; Sanjay Chaturvedi, University College of Medical Sciences, New Delhi; Muzammil Khurshid and Swarna Rastogi, Muzaffarnagar Medical College, Muzaffarnagar, Uttar Pradesh; Ashok Kumar and Prabhat Kumar Lal, Darbhanga Medical College, Darbhanga, Bihar; A Althaf, Government Medical College, Malappuram and Sairu Philip, T.D. Medical College, Alappuzha, Kerala; Himesh Barman and Star Pala, North Eastern Indira Gandhi Regional Institute of Medical Sciences, Shillong, Meghalaya; Satish Saroshee and Suraj Sirohi, Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Medical College, Indore and Abhijit Pakhre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh.

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Supplement 1: Summary of the approach to conducting the Intensified Mission Indradhanush (IMI) case-study

Supplement 2: Summary of methods and findings from population-based household surveys

See www.bmj.com/multisectoral-collaboration for other articles in the series.

Contributors and sources:VG, PH, MKA, MJ, PS, and NKA conceptualised the case study and approach. PH, NKA, MKD, and JM developed the method. Group members PH, AC, MKD, and JM collected data and oversaw data collection. AC, MKD, and JM analysed the data. PH, AC, NKA, MKD, and JM conducted the data synthesis. NKA, MKD, and JM drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript before finalisation. NKA acts as guarantor. VG and PH are guarantors for unpublished administrative IMI data and concurrent monitoring data for the routine immunisation programme collected by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare: VG, PH, MKA, AC, MJ, and PS work for the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; PH, MKA, and AC work directly on MI and IMI in the Immunisation Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; support was received from the World Health Organization (Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health) for the submitted work. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of WHO or the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a series proposed by the WHO Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health (PMNCH) hosted by the World Health Organization and commissioned by The BMJ, which peer reviewed, edited, and made the decision to publish the article. Open access fees for the series are funded by PMNCH.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Immunization handbook for medical officers. WHO, 2016. http://www.searo.who.int/india/publications/immunization_handbook2017/en/

- 2. Lahariya C. A brief history of vaccines & vaccination in India. Indian J Med Res 2014;139:491-511. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vashishtha VM. Status of immunization and need for intensification of routine immunization in India. Indian Pediatr 2012;49:357-61. 10.1007/s13312-012-0081-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. National family health survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India. IIPS, 2017. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR339/FR339.pdf

- 5. Laxminarayan R, Ganguly NK. India’s vaccine deficit: why more than half of Indian children are not fully immunized, and what can—and should—be done. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:1096-103. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar C, Singh PK, Singh L, Rai RK. Socioeconomic disparities in coverage of full immunisation among children of adolescent mothers in India, 1990-2006: a repeated cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009768. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taneja G, Sagar KS, Mishra S. Routine immunization in India: a perspective. Indian J Community Health 2013;25:188-92. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Mission Indradhanush, operational guidelines. Delhi, India: MOHFW, 2014. http://164.100.158.44/showfile.php?lid=4258

- 9. Immunization Technical Support Unit Report of Integrated Child Health & Immunization Survey (INCHIS)-Round 1 and 2. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW). Intensified Mission Indradhanush, operational guidelines. MOHFW, 2017. https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/Mission%20Indradhanush%20Guidelines.pdf

- 11. Bhatnagar P, Gupta S, Kumar R, Haldar P, Sethi R, Bahl S. Estimation of child vaccination coverage at state and national levels in India. Bull World Health Organ 2016;94:728-34. 10.2471/BLT.15.167593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, United Nations Development Programme, Global Alliance for Vaccine Initiative. Improving efficiency of vaccination systems in multiple states: e-VIN factsheet. United Nations Development Programme, 2017. http://www.in.undp.org/content/india/en/home/operations/projects/health/evin.html

- 13.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW). Intensified Mission Indradhanush- financial guidelines. MOHFW, 2017: Annexure 6. https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/Mission%20Indradhanush%20Guidelines.pdf

- 14.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Standard operating procedures for engaging with youth institutions (NCC, NSS, NYKS) and Rotary for social mobilization for Intensified Mission Indradhanush (IMI) and routine immunization. MOHFW, 2018. https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/SOPs%20Engagement%20of%20Youth%20Organizations%20and%20Rotary%20for%20Immunization%20.pdf

- 15.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. United Nations Development Programme, Global alliance for vaccine initiative. E-VIN Tracking Database, October 2017 – April 2018. Delhi, India: MOHFW; 2018 http://www.in.undp.org/content/india/en/home/operations/projects/health/evin.html

- 16. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Coverage Evaluation Survey- Intensified Mission Indradhanush. MOHFW, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Microplanning for immunization service delivery using the Reaching Every District (RED) strategy. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/ 10665/70450/1/WHO_IVB_09.11_eng.pdf

- 18.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Certification for Polio Eradication (NCCPE). Minutes of 29th meeting of the NCCPE (13-14 November 2017), New Delhi, India: MOHFW, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Singh P, Das JK, Dutta PK. Misconceptions/rumors about oral polio vaccine in western UP: A case study. Indian J Prev Soc Med 2010;41:28-32. http://medind.nic.in/ibl/t10/i1/iblt10i1p28.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20. Onnela JP, Landon BE, Kahn AL, et al. Polio vaccine hesitancy in the networks and neighborhoods of Malegaon, India. Soc Sci Med 2016;153:99-106. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Rural Development and Ministry of Panchayati Raj. Extended Gram Swaraj Abhiyan. Government of India. 2018. http://egsa.nic.in/Download.aspx

- 22.Ministry of Rural Development. Gram Swaraj Abhiyan. Government of India. 2018. https://rural.nic.in/gram-swaraj-abhiyan

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement 1: Summary of the approach to conducting the Intensified Mission Indradhanush (IMI) case-study

Supplement 2: Summary of methods and findings from population-based household surveys