Abstract

Jai Das and colleagues present an innovative and evolutionary model of multistakeholder and multisectoral collaboration in scaling up coverage of health services in Afghanistan

Owing to the longstanding civil war after the Soviet invasion of 1979, neglect of the social sector, and subsequent political instability, Afghanistan faced economic collapse in 2001, with compromised infrastructure and extremely limited capacity for delivering health services.1 Compounded by complex geography and widespread poverty, Afghanistan’s health and survival indicators were among the worst globally. The average life expectancy was only 44.5 years, and the estimated maternal mortality ratio (1600 per 100 000 live births) and infant mortality rate (165 per 1000 live births) were alarmingly high.2 Recurrent illness and suboptimal infant and young child feeding and hygiene practices led to high rates of childhood undernutrition.3 Coverage of essential reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health interventions was abysmal, with skilled birth assistants at only 14% of births and safe drinking water being available to <40% of the population.4 Access to health services was also poor, with only 10% of the population living within one hour’s walking distance of a health facility.5 Economic and social indicators had waned after three decades of war—only 30% of Afghans were literate (only 5.7% of females) and annual gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was about $199 (£156; €176) (see section 1 of supplementary file).4 6

Afghanistan’s priorities in 2001 were to rapidly increase access to primary healthcare and to prioritise key interventions, such as basic civic services, education, food security, and childhood immunisations, particularly for rural and underserved populations. Meanwhile the government embarked on longer term, multisectoral planning. Afghanistan introduced the Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS) in 2003 through a process of innovative multisectoral collaboration that encompassed devising, implementing, scaling, and iteratively refining health service delivery in a poor, postwar crisis setting. This package is one of the first and longest running primary healthcare models of its kind, and has been cited as a success, despite reported limitations and ongoing challenges.7 8 9

In response to the World Health Organization’s Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health’s call for proposals on success factors for multisectoral collaboration, we report our case study of BPHS.10 We define multisectoral initiatives as deliberate collaboration between stakeholders (such as government, donors, non-governmental organisations, and academia) and key sectors (such as health, economy, and environment) to ensure rapid gains in health service coverage and outcomes.11 12 Limited documentation exists on the process of developing BPHS, and there was no formal evaluation; not surprising in a country rebuilding after decades of conflict.13 14 15 We evaluate and report the successes, challenges, and lessons from the multisectoral development of BPHS; our methods are described in box 1.

Box 1. Methodology.

We formed a country working group of stakeholders including representatives from government, donors, United Nations agencies, major non-governmental organisations and academia (see section 2 of supplementary file). Then we conducted a systematic review to identify existing literature; two reviewers searched EMBASE, Medline, Scopus, CINAHL, PubMed, and Google Scholar with relevant key words. Grey literature was also searched using Google and other indexes. Data from identified studies were abstracted on an extraction sheet, and conflicts were resolved by consensus or contacting a third reviewer. We reviewed the genesis and implementation of BPHS using the seven component conceptual framework, developed for the WHO Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health.16 The components are context, challenge, and stakeholders; programme description; framing and planning; implementation architecture and mechanisms; monitoring, accountability, and learning; results; and evolution, scale, and sustainability. We also conducted a search to identify large, national, household surveys (including Demographic Health Surveys, Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, National Risk and Vulnerability Assessments, Afghanistan Living Conditions Surveys, National Nutritional Surveys, and Afghanistan Health Surveys), and extracted data on relevant indicators including for poverty, GDP, WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene), and reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health. We performed a trend analysis over the years for which data was available. We prepared a preliminary report and shared it with key stakeholders and the country working group; a multistakeholder review meeting was held in July 2018 in Kabul to appraise and refine the report’s content, suggest additional sources of data, and provide feedback on the process of developing this case study. The multistakeholder review process drew on both the methods used in the first success factors study series17 and the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health’s guide for multistakeholder dialogues.18

Context, challenge, and stakeholders

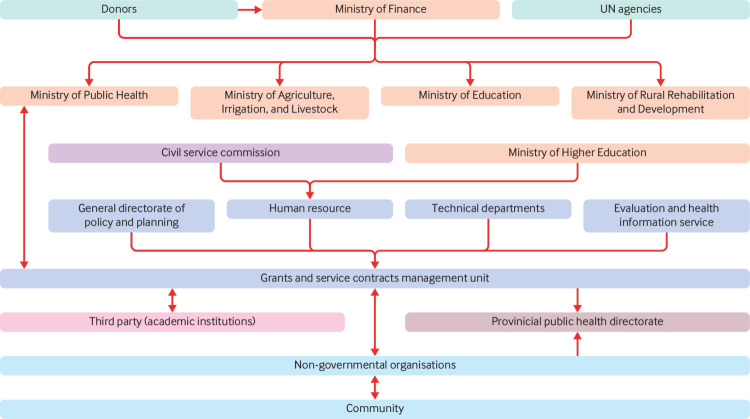

Afghanistan’s social, political, economic, environmental, and health context in 2001 required immediate and innovative actions. Faced with poorly distributed and dysfunctional health facilities, insufficient funding, and extreme shortage of healthcare professionals, the conception and implementation of BPHS was the first step in tackling Afghanistan’s complex health challenges (see section 1 of supplementary file).8 In 2002, a diverse group of stakeholders from government (line ministries), UN agencies, international and national non-governmental organisations, academia, and donors (including the World Bank, European Union (EU), and United States Agency for International Development (USAID)), agreed on a collaborative model to deliver essential health services through BPHS (fig 1).19

Fig 1.

Multisectoral model of engagement for Afghanistan’s BPHS

Programme description: what did BPHS encompass?

BPHS was designed to provide a standardised package of basic health services to the population (prioritising women’s and children’s health) and equitable access through targeted services to underserved areas.2 4 6 19 It comprises seven primary elements: maternal and newborn health; child health and immunisation; nutrition; communicable disease treatment and control; mental health; disability and physical rehabilitation services; and regular supply of essential drugs (see section 3 of supplementary file).19 After launching in 2003, it was revised in 2005 and 2010, expanding the package to respond to newly identified health priorities (table 1).4 19 A third revision is underway, with a focus on non-communicable diseases. In 2005, the essential package of hospital services was modelled to complement BPHS and to define the hospital referral system.

Table 1.

| Healthcare services | 2003 | 2005 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal and newborn health | Antenatal care Delivery care Postpartum care Family planning Care of the newborn |

Same as 2003 | Same as 2003 |

| Child health and immunisation | Expanded Programme on Immunisation services (routine and outreach) Integrated Management of Childhood Illness |

Same as 2003 | Same as 2003 |

| Public nutrition | Micronutrient supplementation Treatment of clinical malnutrition |

Prevention of malnutrition Assessment of malnutrition Treatment of malnutrition |

Prevention of malnutrition Assessment of malnutrition |

| Communicable disease treatment and control | Control of tuberculosis Control of malaria |

Control of HIV Control of tuberculosis Control of malaria |

Prevention of HIV and AIDS Control of tuberculosis Control of malaria |

| Mental health* | Community management of mental health problems Health facility based treatment of outpatients and inpatients |

Mental health education and awareness Case detection Identification and treatment of mental illness |

Mental health education and awareness Case identification, diagnosis, and treatment |

| Disability and physical rehabilitation services* | Physiotherapy integrated into primary healthcare services Orthopaedic services expanded to hospital level |

Disability awareness, prevention, and education Assessment Referrals |

Disability awareness, prevention, and education Provision of physical rehabilitation services Case identification, referral and follow-up |

| Regular supply of essential drugs | All essential drugs required for basic services | Listing of all essential drugs needed | Same as 2005 |

Though included in 2003, these were deprioritised from 2005 onwards

Planning, implementation architecture, and mechanisms

The developers of BPHS relied on data from household surveys, global experience from comparable circumstances, and the resources and capacity of the government to devise a strategy. Non-governmental organisations working in Afghanistan were given the responsibility of implementing BPHS based on their experience and capacity.

Non-governmental organisations delivered BPHS services in 31 of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces through a contracting-out mechanism. In three provinces (Panjshir, Kapisa, and Parwan), the Ministry of Public Health delivered BPHS through a contracting-in approach called the strengthening mechanism.22 The ministry provided overall stewardship and responsibility for the delivery of quality services throughout the country. A grants and services contract management unit was set up at the ministry to manage the wide range of implementers, to monitor grants compliance and service delivery, and to coordinate with other departments (including the Expanded Programme of Immunisation, nutrition, reproductive health, and others). A public health directorate was set up for each province to coordinate and monitor the non-governmental organisations. Consultative mechanisms were established at national, ministerial, provincial, and community levels to keep stakeholders engaged and informed (detailed in section 4 of the supplementary file).

The findings of our systematic review and multistakeholder consultations indicated that the Ministry of Publish Health and non-governmental organisations were the major drivers of BPHS, with important influence from donors (table 2). The Ministry of Finance and the Provincial Public Health Directorates also had notable involvement and influence. Other sectors (education, development, agriculture) had complementary roles in human resource and structural capacity. Local communities were the primary beneficiaries and were also involved in development.

Table 2.

BPHS stakeholder roles

| Organisation or group | Role | Phases in which engaged | Involvement, (in terms of time, resources) | Influence | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Public Health | Stewardship/ oversight | All phases | High | High | Stewardship/ oversight |

| Ministry of Finance | Fund holder | Finance Report | Medium | Medium | |

| Ministry of Higher Education | Training doctors | Implementation | Low | Medium | Trainings |

| Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Livestock | Lead development in agriculture and livestock | Implementation | Low | Medium | Support food security and nutrition related activities |

| Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development | Lead infrastructure and road development | Implementation | Low | Medium | Develop Infrastructure |

| Provincial Public Health Directorates | Coordinator | Implementation | Medium | Medium | Provincial level monitoring |

| Donors | Provide funds | Design and reporting | Medium | Medium | Influencing Policy |

| Non-governmental organisations | Implementation | Planning/reporting | High | High | Technical Support |

| UN | Support/technical assistance | All phases | Low | Low | Oversight |

| Political groups | Lobby | Implementation | Low | Low | Lobby |

| Community | Support services | Implementation, planning | Low | Medium | Voluntary work |

The Ministry of Finance set up multidonor trust funds to mobilise human and capital resources for the rebuilding of socioeconomic institutions. The Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF), the largest and longest running such trust in the world, was established in 2002.23 Donors averse to funding the Afghan government directly preferred ARTF owing to its relatively high accountability and transparency (box 2).24

Box 2. Funding mechanisms.

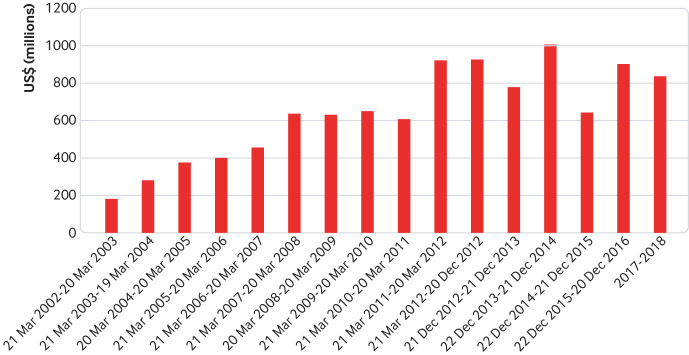

Among the 34 donors that have contributed to the ARTF since its inception, 17 continue to contribute regularly (fig 2).24 ARTF channels funding to all sectors, the mechanisms of which have changed over time, including improved monitoring and evaluation and various performance based approaches. BPHS’s three major donors are the EU, USAID, and the World Bank. USAID provided support in 13 provinces, the World Bank in 11, and the EU in 10.25 These donors, together with Ministry of Public Health, have also funded non-governmental organisations to deliver BPHS through various mechanisms. The majority of BPHS’s major donor funding has been disbursed through the Ministry of Finance for general BPHS budget spending, while other donors have pledged money for specific activities (vertical programs and innovations), generally made directly to service providers (Ministry of Public Health or non-governmental organisations). By the end of 2008, donors were fully funding BPHS service delivery through non-governmental organisations.

Fig 2.

Donor contribution to the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund since 2002

Staff training, recruitment, and deployment strategies were central to the success of BPHS. The Ministry of Higher Education provided training to doctors, and the Ministry of Public Health provided pre-service training to midwives and paramedics. A national standard salary policy was announced in 2006, which encouraged incentives for employment in underprivileged locations.26

BPHS’s vision was to get services to the poorest, most underserved and isolated regions, so community based outreach modalities were critical. Voluntary community health workers and community groups provided the major health workforce, attending to about two thirds of all family planning clients and managing nearly half of all sick children.27 The various tiers of community engagement and demand creation strategies are detailed in section 5 of the supplementary file.

Multisectoral planning and actions

Although direct multisectoral planning to support investments in education, promotion of food security, the built environment, and WASH services were uncoordinated, several parallel cross-sectoral initiatives in these sectors led to or enabled gains in health.

In 2003, the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Livestock—working closely with Public Nutrition Department in the Ministry of Public Health—developed the country’s first Public Nutrition Policy and Strategy to coordinate BPHS nutrition services. The Health and Nutrition Policy and Strategy 2012-20 and Food Security and Nutrition Strategy 2015-19 showed further commitment to the right to nutrition.

Various approaches were used to expand access to education in remote and rural communities, including community based education and accelerated learning centres.28 The 2004 Education Quality Improvement Programme aims to increase access to quality basic education, especially for girls, through school grants, teacher training, and strengthened institutional capacity, with the support of communities and private providers.

The National Solidarity Programme, established in mid-2003 by the ministers of finance and rural rehabilitation and development, is a flagship programme to reduce poverty through establishing and strengthening a national network of self governing community institutions and empowering rural communities to make decisions on their own lives. Its projects included construction of irrigation facilities, health facilities, roads, bridges, schools, water supply facilities, and clinics, income generation, and vocational training projects.29

Monitoring, accountability, and learning

Despite data gaps, particularly in severe conflict areas, BPHS’s unique, comprehensive, and rigorous evaluation mechanisms have been fundamental to evidence based decision making and policy formulation.25 The roles of stakeholders in the monitoring and evaluation of BPHS are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Stakeholders’ roles in monitoring and evaluation

| Partners | Expected input |

|---|---|

| Evaluation and health information system | Lead and coordinate all activities |

| Grants and services contract management unit | Coordinate to apply national monitoring and evaluation tools Demand data on performance required for contract and grant management |

| Ministry of Public Health technical departments | Assist in prioritisation, development, and revision of performance indicator Provide technical input to design assessment tools and for verification of values of performance indicators Coordinate to apply national monitoring and evaluation tools |

| EU, World Bank, USAID | Provide financial support for monitoring and evaluation process Promote integrated monitoring and evaluation system |

| Other partners (eg, UNICEF, WHO, and Global Fund) | Promote integrated monitoring and evaluation system Provide technical input in designing of monitoring and evaluation tools Provide logistic and financial support for monitoring and evaluation process |

| Academic partners (Johns Hopkins University, the Indian Institute of Health Management Research, and KIT Royal Tropical Institute) | Perform third party evaluations of health service activities and reach |

The Ministry of Public Health established the Evaluation and Health Information System department to manage, monitor, and provide timely progress data to all stakeholders,30 specifically on national health priority indicators, and to coordinate across ministry departments (see section 6 of supplementary file).30 Tools were developed to collect, monitor, and evaluate the performance of BPHS, such as the routine facility based health management information system, balanced score card, household and facility surveys, field supervision, monitoring checklists, periodic reports submitted by non-government organisations, and surveillance data. Finally, third party academic institutes, including Johns Hopkins University, the Indian Institute of Health Management Research, and KIT Royal Tropical Institute, conducted annual independent evaluations from 2004 onwards.31 32

Outcomes: trends across collaborating sectors

The multisectoral collaboration of BPHS implementation in Afghanistan has generally been positively received.7 8 33 Inequities are described in box 3.

Box 3. Inequities in health.

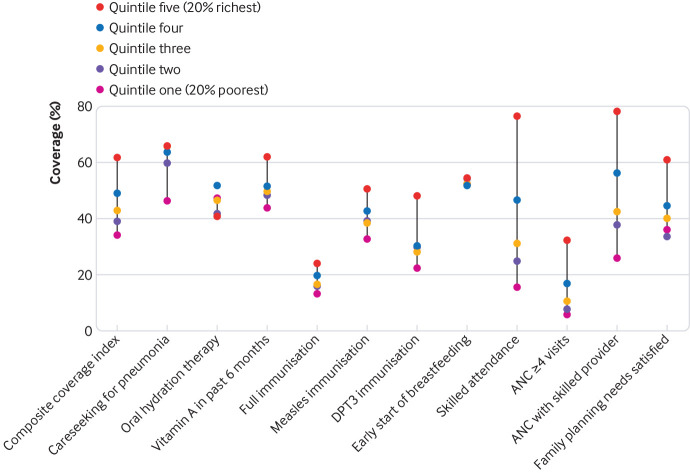

Coverage of interventions for all indicators (health and non-health) varies regionally, with stark inequities between underprivileged, rural, and conflict areas and regions that have more money or are unaffected by conflict.39 41 These regional and socioeconomic inequities jeopardise Afghanistan’s likelihood of meeting its goals of universal coverage of health services and interventions.41 Data from Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys 2010-11 show vast disparities in coverage of essential reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health interventions (fig 3). The interventions most inequitably distributed are antenatal care by skilled birth attendants and receipt of four or more antenatal care visits, whereby richer areas had between three and 5.6 times more coverage than poor areas. Breastfeeding interventions and treatment of sick children, however, were more equitably distributed.41 Inequities also existed across regions, with the highest coverage in urban east, west, and central regions of Afghanistan and lowest in south and southeast regions of the country.41

Fig 3.

Inequities in coverage of key interventions from MICS Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys 2010-11.41 ANC=antenatal care.

Trends in health status and outcomes

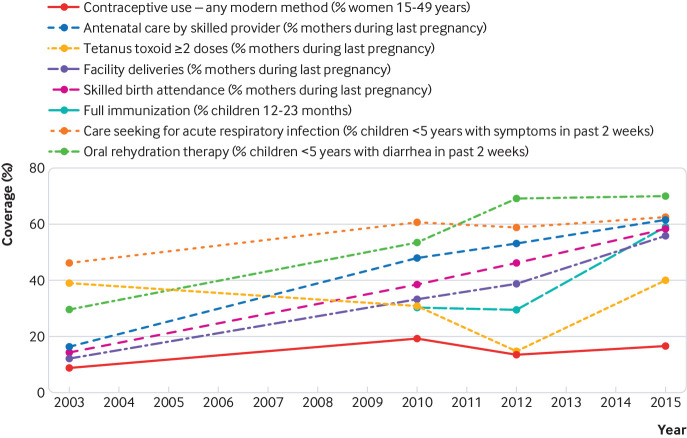

The UN’s best modelled estimates show that under 5 child mortality fell from 130 to 70 deaths per 1000 live births from 2000 to 2016.34 WHO estimates indicate that maternal deaths per 100 000 live births fell from 1100 in 2000 to 396 (uncertainty interval, 253 to 620) in 2015.35 But these estimates may not be reliable, as other data sources indicate that maternal deaths rose from 716 (441 to 1123) in 2003 to 885 (508 to 1445) in 2013.36 These uncertainty intervals are very wide and overlap, but they indicate continuing doubt and the need for better data sources and analytical methods. Nonetheless, progress and trends in many maternal and child health interventions corroborate that maternal mortality has improved in Afghanistan over the past decade and a half37; further analyses are needed to better understand these estimates.38 Since 2003, coverage of many essential maternal interventions (including antenatal care, skilled birth attendants, and facility births for pregnant women) has improved gradually, from around 15% to over 55% in 2015. Coverage of tetanus vaccination among pregnant women, however, has remained stagnant since 2003, and contraceptive use among women has been stagnant since 2012 (fig 4). Full immunisation coverage of children under 2 improved from 30% in 2010 to around 59% in 2015, whereas coverage of oral rehydration therapy for childhood diarrhoea and of care seeking for childhood acute respiratory tract infection has plateaued since 2012, after some initial gains (fig 4).39

Fig 4.

National trends in maternal, newborn, and child health interventions from 2003 to 2015. Sources: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (2003 and 2010); Afghanistan Health Survey (2012 and 2015).

Healthcare infrastructure and workforce have also improved. The total number of active healthcare facilities has risen from 1075 in 2004 to 2493 in 2017, and the absolute number of visits for healthcare rose from 2 million to 84 million over the same period.40 The number of health workers of all cadres has also improved41; the number of female community health workers rose from 729 to 14 016. Two midwifery schools were established in 2002; by 2014, there were 34 institutions, one in each province, which collectively trained several thousand midwives.7

Trends across non-health sectors

In 2001, only one million children were in school, and almost all of those were boys; by 2015, 8.8 million children were enrolled in schools, nearly 38% of which were girls.28 There was a concurrent increase in school educators, growing from 21 000 to 187 000.28 Adult literacy rates improved overall, but the proportion of primary school age children attending school is still low at 57% (64% for boys and 48% for girls); the gender parity index (ratio of girls to boys in primary education) also improved from 0.69 to 0.74 between 2007 and 2012.28

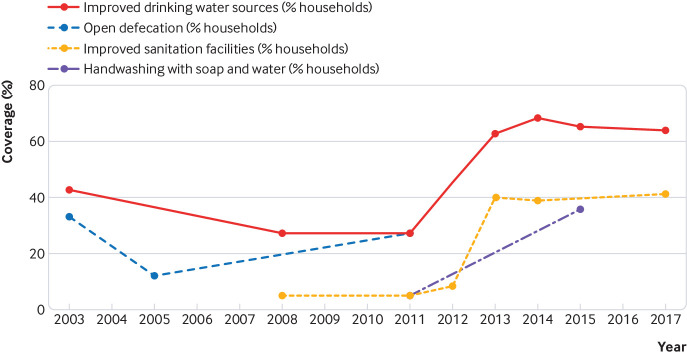

Rural water supply activities have accelerated and reached about 365 000 people, and community led total sanitation has also been scaled up. Between 2000 and 2017 population access to improved drinking water sources and to sanitation facilities rose from 42% to 64% and from 5% to 41%, respectively, but progress has plateaued since 2013. Handwashing with soap and water has improved from 5% in 2011 to 36% in 2015, whereas data on open defecation rates do not show any overall change since 2003; there are no data after 2011 (fig 5).42

Fig 5.

National trends in water and sanitation from 2003 to 2017. Sources: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (2003); National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment (2005, 2007-8, 2011-12, 2013-14, and 2016-17); Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey (2007-08, 2011-12, and 2016-17); National Nutritional Survey-Afghanistan (2013); Afghanistan Health Survey (2015)

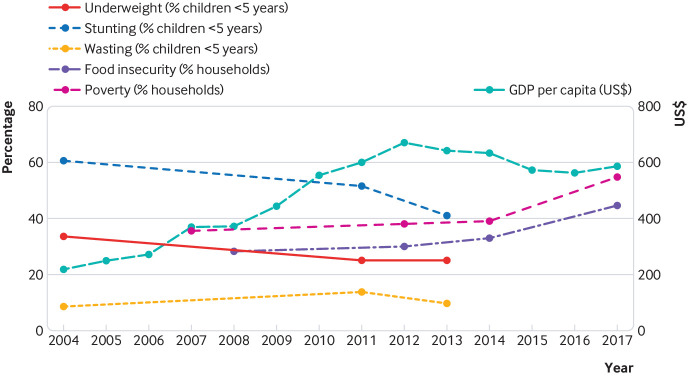

There have been concurrent gains in economic development (fig 6) and in promising regional trade partnerships, as well as substantial efforts by the government to increase domestic revenue.43 GDP per capita increased from $199 in 2002 to $669 in 2012, but thereafter declined to $586 in 2017. Poverty rates have risen from 36% in 2007 to 55% in 2017, and prevalence of food insecurity has increased from 28% in 2008 to 45% in 2017. Despite fluctuations in data, stunting prevalence has fallen from about 61% in 2004 to 41% in 2013, prevalence of underweight children has declined from 41% in 2003 to 25% in 2013, and wasting prevalence has remained constant since 2003 (fig 6).

Fig 6.

National trends in poverty, nutrition and food security from 2003 to 2017. Sources: National Nutritional Survey (2004 and 2013); Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (2010); Afghanistan Health Survey (2012 and 2015); Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey (2007-08, 2011-12 and 2016/17; Data of Gross Domestic Product (GDP): World Bank 1.

Evolution, scale, and sustainability

The funding mechanism of BPHS was modified after 2010 to reflect donor transitions and streamlining of funds (see section 7 of the supplementary file). The contracts awarded to non-government organisations for implementation became performance based, with 20% of total payment linked to proportional achievement of key indicators stipulated in the contract. The Community Midwifery Education programme was added to BPHS to tackle the shortage of midwives in rural and hard-to-reach areas.44 This programme engaged the community at all stages, including designing, priority setting, planning, and implementation. The Community Health Nursing Education programme builds on the successful experiences and lessons learnt from the midwifery programme. Various innovations have been pilot tested and implemented to improve the coverage of essential interventions (box 4).

Box 4. Innovations in health.

Core elements and delivery of BPHS have been modified over time, based on the evidence it generated. Innovations that have been tested as part of BPHS include those targeted to improving the reach of health services (mobile health teams), increasing access (family health houses and maternity waiting homes), improving quality of services (results based financing and conditional cash transfers), and increasing the use of technology (ehealth innovations) (see section 8 of the supplementary file). The current contracts of non-government organisations have a separate budget for innovations, which is equivalent to around 10% of the total budget.

Afghanistan’s BPHS continues to evolve, and many have questioned its sustainability.8 33 The Ministry of Public Health provides stewardship and oversight of funds, but prospective planning and coordination with diverse sectors, particularly education, agricultural, and rural development is needed for sustainability. The recent Citizens Charter (2016), for example, is a joint effort between the Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development, the Ministry of Public Health, and other ministries that entrusts accountability of the health system to communities themselves. Such prospectively planned cross sectoral initiatives are the next steps for healthcare sustainability in Afghanistan.

Discussion

Afghanistan’s BPHS is an example of how stakeholders and sectors collaborated to implement a basic health structure, achieving gains in a region affected by conflict. These gains were largely realised owing to the well defined roles of stakeholders, structured programme governance and implementation, monitoring and evaluation systems, committed external funding, and political will. After the initial response phase, with its focus on national immunisation campaigns, the subsequent development of BPHS reflected the government’s desire to expand provision of basic primary care services. Notwithstanding the multisectoral consultations in design, execution, and oversight, the programme was mainly stewarded and implemented by the Ministry of Public Health with contributions from other ministries. Multistakeholder planning was a formal process, but multisectoral implementation had few formal processes, one was Afghanistan’s nutrition policy and strategy, which was a formal collaboration between the Ministry of agriculture, irrigation and livestock and the Ministry of Public Health.

Evidence on the effect of BPHS on the coverage of essential reproductive, maternal, and child health interventions and on health outcomes is mixed. Antenatal care, skilled birth attendants, and facility based births have improved, but use of contraceptives has been stagnant, which has been linked to low education among women, insecurity, lack of access, and low socioeconomic status of the population.45 Among child interventions, there have been improvements in vaccination, care seeking behaviour, and management of childhood illnesses. Prevention of malnutrition has been challenging, because improvements in nutritional status require efforts and collaboration across sectors other than health, encompassing poverty alleviation, food security, agricultural and economic growth, education, and social safety nets46; progress on these has been suboptimal in Afghanistan, especially in populations with low access to healthcare in rural and conflict areas.

BPHS is adaptive, as evident in its changing modalities of funding, contracting process, interventions provided, and mechanisms for monitoring and evaluation. Community based approaches have also helped increase access to healthcare, generate demand, and improve equity. The Community Midwifery Education programme has been a major success in delivery of services, also providing marginalised women with work opportunities, which aided the economic uplift, but the high attrition rate of female health professionals is an ongoing obstacle.38 Mobile health teams and community groups have helped in increasing demand for healthcare.

There are several limitations and unaddressed challenges, including limitations in data collection linked with the inherent difficulties in obtaining robust information in a chronically fragile state, with limited access in areas affected by severe conflict. There are cultural barriers to women seeking care, and the female health workforce is below the required numbers, especially in rural and severe conflict areas. This, together with low education levels among women, further complicates existing challenges and hinders simple solutions. There are still a high percentage of out-of-pocket expenditures and these are largely due to lack of access to health facilities, inconsistent quality of BPHS, and an unregulated private sector.44 47

Although Afghanistan has improved some health indicators and service delivery and has vastly increased the number of health facilities and workers, the health system remains far weaker than needed to ensure universal coverage, equitable access, and uniform benefit. The proportion of the population living within an hour’s walking distance of a health facility has increased from 10% in 2002 to 57% in 2014.47 Much of the gain achieved through the contracting-out model needs to be supplemented with robust public sector programmes focusing on reducing inequities and reaching marginalised populations, as a majority of the population lives in rural areas (75.5%).41 48 49 There must be an enhanced focus on reducing gender disparities, promoting education and reducing school dropout rates among girls in rural populations. This requires strategies and progress in multiple other sectors, including economic growth, poverty reduction strategies, investments in education, and emphasis on improved transport and communication networks (see section 9 of supplementary file).

Afghanistan has experienced a debilitating conflict and civic unrest for almost four decades. An entire generation has experienced conflict and adversity, with consequences that may run across generations.37 50 With escalating conflict since 2010, limited capacity of the health system and the heavy dependence on donors, much of the development support has come from the coalition countries and is likely to diminish in future. There is now a need for sustainable plans with greater emphasis on multisectoral implementation and an earlier move towards multisectoral and intersectoral planning; this was not a key element during the era of the millennium development goals. This has changed in the context of the sustainable development goals,51 and investments could be accelerated.

As a signatory to the sustainable development goals, Afghanistan should explore a national dialogue on developing an integrated strategy for health and related determinants. Creation of a national think tank to oversee this process and to develop formal multisectoral plans for action is an important next step. The Ministry of Economy was designated as the lead ministry and focal point in this effort in 2015 under the guidance of the UN Development Programme,52 and, moving forward, additional ministries (notably those involved in public health and nutrition) must be closely engaged in this effort. Afghanistan has shown progress in an ongoing conflict, and there is no reason why the next decade should not see accelerated progress in human development.

Key messages.

Afghanistan’s BPHS programme has successfully scaled up health services in a poor, low capacity setting, using effective multisectoral collaboration among stakeholders and sectors

Key factors in its success include the interest and commitment of donors, coupled with coordination and stewardship from the Ministry of Public Health and implementation contracted out to non-government organisations

Community based outreach programmes have been critical and will be the platform for achieving universal health coverage, particularly for remote and isolated populations

Multisectoral planning, exploiting the interconnectedness of the sustainable development goals and deliberate engagement of multiple sectors will be critical to achieving Afghanistan’s development goals

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary file

See www.bmj.com/multisectoral-collaboration for other articles in the series.

We acknowledge the country working group who participated in the multistakeholder meeting and provided valuable feedback. This comprises Alim Atarud, Abdullah Fahim, Sayed Attaullah Sayedzai, Aziz Baig, Habibullah Ahmadzai, Khalil Mohmand, Khwaja Mir Islam Saeed, Mohammad Fareed Asmand, Nasir Hamid, Bahara Rasooly, Muzhgan Habibi.

Ethical approval: Ethical exemption was sought and approved by the Ethical Review Committee at Aga Khan University, Karachi, and the Institutional Review Board, Kabul.

Contributors and sources: NA, JKD, SM, and ZAB conceived the idea for this study and wrote the study proposal. JKD guided and worked on the systematic review with a technical team (ZP, KM) at Aga Khan University, Karachi. NA guided and worked with ON on the systematic review at SickKids Toronto. JKD and SM conducted the multistakeholder meeting with guidance from ZAB and AJN. CEA provided overall project coordination and oversight. All authors contributed to the synthesis and writing of the manuscript. ZAB is responsible and overall guarantor of the content.

Competing interests: The authorship team has read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: JKD, NA, ZP, ON, CEA, KM, ZAB declare no competing interests. SM was associated with the Aga Khan Health Service, Afghanistan from 2003 to 2005 and 2008-2018 and involved in implementing BPHS in three provinces of Afghanistan: Badakhshan, Baghlan, and Bamyan. AJN is the current Deputy Minister of Health, Afghanistan.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a series proposed by the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health, hosted by the World Health Organization (WHO PMNCH) and commissioned by The BMJ, which peer reviewed, edited, and made the decision to publish the article. Open access fees for the series are funded by WHO PMNCH.

References

- 1.Institutt M. Afghanistan country evaluation brief 2016. https://www.norad.no/en/toolspublications/publications/2016/country-evaluation-brief-afghanistan/.

- 2.Central Statistics Organization (Afghanistan), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Afghanistan Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey. 2003. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/afghanistan-multiple-indicator-cluster-survey-2003.

- 3. Johnecheck WA, Holland DE. Nutritional status in postconflict Afghanistan: evidence from the national surveillance system pilot and national risk and vulnerability assessment. Food Nutr Bull 2007;28:3-17. 10.1177/156482650702800101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2003. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/afghanistan-multiple-indicator-cluster-survey-2003

- 5.Ministry of Public Health. Ministry of Public Health: annual report 1387. 2008. http://moph.gov.af/en/documents/category/annual-report.

- 6.World Bank national accounts data, OECD National Accounts data files. GDP (current US$) 2000-2015 https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD.

- 7. Ahmadi Q, Danesh H, Makharashvili V, et al. SWOT analysis of program design and implementation: a case study on the reduction of maternal mortality in Afghanistan. Int J Health Plann Manage 2016;31:247-59. 10.1002/hpm.2288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Newbrander W, Ickx P, Feroz F, Stanekzai H. Afghanistan’s basic package of health services: its development and effects on rebuilding the health system. Glob Public Health 2014;9(Suppl 1):S6-28. 10.1080/17441692.2014.916735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frost A, Wilkinson M, Boyle P, Patel P, Sullivan R. An assessment of the barriers to accessing the Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS) in Afghanistan: was the BPHS a success? Global Health 2016;12:71. 10.1186/s12992-016-0212-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization (WHO). What works and why? Success Factors for collaborating across sectors for improved women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health. 2018. http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/case-studies/en/index3.html.

- 11. Salunke S, Lal DK. Multisectoral approach for promoting public health. Indian J Public Health 2017;61:163-8. 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_220_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Project HP. Capacity Development Resource Guide: Multisectoral Coordination Washington DC. 2014. https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/272_MultisectoralCoordinationResourceGuide.pdf.

- 13. Keim M. Managing disaster-related health risk: a process for prevention. Prehosp Disaster Med 2018;33:326-34. 10.1017/S1049023X18000419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Olu O, Usman A, Manga L, et al. Strengthening health disaster risk management in Africa: multi-sectoral and people-centred approaches are required in the post-Hyogo Framework of Action era. BMC Public Health 2016;16:691. 10.1186/s12889-016-3390-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization (WHO). UHC 2030 Multi-stakeholder Consultation. Geneva. 2016. https://www.uhc2030.org/fileadmin/uploads/ihp/Documents/About_IHP_/mgt_arrangemts___docs/UHC_Alliance/UHC2030ConsultationReportFinald.pdf.

- 16.World Health Organization (WHO). Methods guide for country case studies on successful collaboration across sectors for health and sustainable development. 2018. http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/case-study-methods-guide.pdf.

- 17. Frost L, Hinton R, Pratt BA, et al. Using multistakeholder dialogues to assess policies, programmes and progress for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health. Bull World Health Organ 2016;94:393-5. 10.2471/BLT.16.171710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization (WHO). Multistakeholder dialogues for women’s and children’s health: a guide for conveners and facilitators. 2014. http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/msd_guide.pdf.

- 19.Government of Afghanistan, Ministry of Health. A basic package of health services for Afghanistan—2010/1389. 2010. http://saluteinternazionale.info/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/Basic_Pack_Afghan_2010.pdf.

- 20.Government of Afghanistan Ministry of Health. A basic package of health services for Afghanistan. 2005. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21746en/s21746en.pdf.

- 21.Government of Afghanistan Ministry of Health. a basic package of health services for Afghanistan. 2003. http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/apcity/unpan018852.pdf.

- 22.USAID. Afghanistan basic package of health services (BPHS) study: cost-efficiency, quality, equity and stakeholder insights into contracting modalities. 2013. https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/245_ContractingModalitiesStudyFINALREPORT.pdf.

- 23.Disch A, Wardak M, Shah AH, et al. External review, Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund, ARTF. 2017. http://www.artf.af/images/uploads/ARTF_External_Review_Final_Report_2017.pdf.

- 24.Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund. End of year report. World Bank; 2016. http://www.artf.af/images/uploads/ARTF_2016_End-of-year-Report_final_web_version.pdf.

- 25.Belay TA. Building on early gains in Afghanistan's health, nutrition, and population sector: Challenges and options: World Bank; 2010: 1-288 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salary Policy Working Group. National salary policy 2005. https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/europeaid/online-services/index.cfm?ADSSChck=1375069165553&do=publi.getDoc&documentId=94460&pubID=128652.

- 27.USAID. Empowering communities: community-based health care in Afghanistan. 2014.

- 28.The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Afghanistan National Education for All (EFA) Review 2015. 2015. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002327/232702e.pdf.

- 29.World Bank. Implementation completion and results report, for the National Solidarity Program III 2017. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/984941514909801500/pdf/ICR00003688-12282017.pdf.

- 30.Ministry of Public Health. [Afghanistan] Health information system: review and assessment. 2007. http://www.paris21.org/sites/default/files/afghan-HMNassessment-2007.pdf.

- 31. Susan S, Parida I. Mobilizing NGOs through coordinated donor and ministry support for basic health care service delivery in Afghanistan, 2002-14. Global Delivery Initiative, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Royal Tropical Institute. Balance score card reports. 2016. http://moph.gov.af/en/documents/category/bsc-reports.

- 33. Edward A, Osei-Bonsu K, Branchini C, Yarghal TS, Arwal SH, Naeem AJ. Enhancing governance and health system accountability for people centered healthcare: an exploratory study of community scorecards in Afghanistan. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:299. 10.1186/s12913-015-0946-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN-IGME). Levels and trends in child mortality report 2017. 2017. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/mortality/child-mortality-report-2017.shtml.

- 35.World Health Organization (WHO). Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. 2015. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/maternal-mortality-2015/en/.

- 36. Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014;384:980-1004. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60696-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Akseer N, Salehi AS, Hossain SM, et al. Achieving maternal and child health gains in Afghanistan: a Countdown to 2015 country case study. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e395-413. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30002-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Michael M, Pavignani E, Hill PS. Too good to be true? An assessment of health system progress in Afghanistan, 2002-2012. Med Confl Surviv 2013;29:322-45. 10.1080/13623699.2013.840819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Bank. Progress in the Face of Insecurity: Improving Health Outcomes in Afghanistan. 2018. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/infographic/2018/03/06/progress-in-face-of-insecurity-improving-health-outcomes-in-afghanistan.

- 40.Ministry of Public Health. Afghanistan. Health information management system. 2012. http://moph.gov.af/Content/Media/Documents/Afghanistan-HMIS-Guideline30122010104756600.pdf.

- 41. Akseer N, Bhatti Z, Rizvi A, Salehi AS, Mashal T, Bhutta ZA. Coverage and inequalities in maternal and child health interventions in Afghanistan. BMC Public Health 2016;16(Suppl 2):797. 10.1186/s12889-016-3406-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund. ARTF scorecard 2016—integrated performance and management framework. World Bank; 2016. http://www.artf.af/images/uploads/home-slider/artf-scorecard-2016-final-web.pdf.

- 43.The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Annual report, Afghanistan 2017. https://www.unicef.org/about/annualreport/files/Afghanistan_2017_COAR.pdf.

- 44.Khalil A. Community midwifery education program in Afghanistan. 2013.http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/138781468185951486/Community-midwifery-education-program-in-Afghanistan.

- 45. Osmani AK, Reyer JA, Osmani AR, Hamajima N. Factors influencing contraceptive use among women in Afghanistan: secondary analysis of Afghanistan Health Survey 2012. Nagoya J Med Sci 2015;77:551-61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ruel MT, Alderman H, Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: how can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? Lancet 2013;382:536-51. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60843-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nic Carthaigh N, De Gryse B, Esmati AS, et al. Patients struggle to access effective health care due to ongoing violence, distance, costs and health service performance in Afghanistan. Int Health 2015;7:169-75. 10.1093/inthealth/ihu086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Carvalho N, Salehi AS, Goldie SJ. National and sub-national analysis of the health benefits and cost-effectiveness of strategies to reduce maternal mortality in Afghanistan. Health Policy Plan 2013;28:62-74. 10.1093/heapol/czs026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shahir I, Homayee S, Fitzwarryne C, et al. Planning and Reform of Human Resources for Health in Afghanistan. Afghanistan Journal of Public Health 2017;1:34-41. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bhutta ZA, Keenan WJ, Bennett S. Children of war: urgent action is needed to save a generation. Lancet 2016;388:1275-6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31577-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Blomstedt Y, Bhutta ZA, Dahlstrand J, et al. Partnerships for child health: capitalising on links between the sustainable development goals. BMJ 2018;360:k125. 10.1136/bmj.k125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Habib MA, Soofi S, Cousens S, et al. Community engagement and integrated health and polio immunisation campaigns in conflict-affected areas of Pakistan: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e593-603. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30184-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file