Abstract

Helia Molina Milman and colleagues describe how intersectoral collaboration between health, social protection, and education sectors enabled Chile Grows with You (Chile Crece Contigo) to help all children reach their full developmental potential

An estimated 250 million children aged under 5 (about 43%) in low and middle income countries are at risk of not reaching their developmental potential.1 Poverty, undernutrition, lack of effective medical care, and adverse childhood experiences can all have long term effects on brain development and cognition. Many of these adverse consequences can be avoided by interventions to prevent or manage developmental problems at an early age.1

Chile, a high income country with a population of 17.6 million, has made substantial progress in reducing infant, child, and maternal mortality in the past 40 years through considerable investments in public health, the development of a highly functional health system, and various social policies.2 3 4 5 However, these overall improvements mask high levels of inequality linked to socioeconomic status and education.6 7 The second national quality of life survey in 2005 found that 30% of Chilean children under 5 did not reach their expected development milestones, with the poorest quintile at highest risk of developmental delay (box 1).9 Drawing on these findings and recognising the increasing global evidence of the importance of childhood development to economic and social progress, Michelle Bachelet, a paediatrician and the first woman president of Chile, made child development a priority for her government in 2006.11

Box 1. Tracking early childhood development in Chile—the importance of equity.

National quality of life survey assesses early childhood development using standard measures on a sample of mothers and children aged 7 to 59 months

A validated development assessment tool is used to measure cognitive, motor, language, social, and emotional progress compared with expected milestones for the child’s age8

-

Chile uses the terms developmental lag and delay to describe the degree of developmental risk:

Developmental lag is defined as children who achieve a normal overall developmental test score based on expected milestones for their age but are behind in a developmental sub-area

Developmental delay is defined as children who do not achieve a normal overall developmental test score for their age and are therefore behind expected developmental milestones in more than one area (reflecting a more serious developmental gap)

In 2006, 16.4% of all children under 5 had a developmental lag and 13.5% had a developmental delay, with a total of 30% having either a lag or a delay. Children in the poorest quintile were 12.8% more likely to have a developmental lag or delay. Other disparities were found by sex and area of residence9

Longitudinal studies show that children from lower income families have poorer development of cognitive skills than those from wealthier groups, a disparity which emerges early in life and continues after the age of 610

The resulting initiative, Chile Grows with You (Chile Crece Contigo, ChCC), is a comprehensive protection system for children from the prenatal period to 4 years, taking advantage of every encounter between children and health services and providing coordinated services across different public sectors.12

Although existing evidence identifies interventions that can improve early childhood development, much less is known about how to translate this knowledge into sustainable large scale programmes requiring collaboration and coordination across sectors.13 We aimed to identify the factors that facilitated a national scale-up of ChCC, 10 years after implementation began. Evaluation was led and coordinated by a working group with representation from the Ministry of Social Development and the University of Santiago, Chile, using a modified multistakeholder dialogue approach (supplementary file 1 on bmj.com). Our primary objective was to summarise the progress towards implementation of ChCC, investigating how cross sectoral collaboration and coordination were managed to provide integrated child development care on a national scale.

ChCC: policy development

ChCC aims to help all children reach their full potential for development, regardless of their socioeconomic status. It seeks to support children and families throughout early development, from conception to entry into preschool at age 4, through universal and targeted support services.14 The programme is based on rights and sex equity approaches, building on the scientific evidence regarding the importance of the first years of life, including gestation, for comprehensive human development. It also recognises that inequities between the poorest and wealthiest quintiles of children influence development considerably and need to be tackled to improve developmental outcomes.10 15

In 2006, President Bachelet established the Presidential Advisory Council for Child Policy Reform. The council consisted of external experts from different fields and holding different political views. Experts reviewed international evidence and local data11 and conducted 46 hearings with national and international experts in the field, civil society, multilateral and bilateral organisations, academic institutions, and other relevant organisations, both public and private. Members of the council held hearings in the 13 regional capitals with local organisations and individuals to discuss child health, education, and development. Issues discussed included resources needed for childbirth, improving housing and social services, access to education, and services for indigenous groups. Over 7000 comments were solicited from children, using a website which encouraged expression of opinions about how to improve community resources for learning and development, such as the availability of green space and educational and health services. Its final recommendations were reviewed by an interagency technical team in June 2006 and developed into ChCC.11

ChCC was implemented in 159 municipalities in Chile in 2007; the next year it was extended to the remaining 186 municipalities. In September 2009, Law 20 379 was enacted, institutionalising ChCC and providing a permanent line for it in the national public budget.16 Development of the newborn support and parenting skills programmes began in 2008, with full implementation in 2009. The development, testing, and introduction of the electronic monitoring database began in 2009 and 2010 (box 2).

Box 2. Timeline of programme and policy inputs for the introduction and scale-up of ChCC.

2005-06

•Pre-investment studies

•Presidential Advisory Council for the Reform of Child Policies formed

•Recommendations for early childhood development programme developed after consultations

•Creation of Chile Grows with You (ChCC)

2007-08

ChCC implemented in 159 municipalities

•ChCC extended to all communes in 345 municipalities

•Development of training and communication materials begins

2009-10

•Law 20 379 institutionalising ChCC for the protection of children is approved, with a designated budget line

•Implementation of the newborn support programme parental skills workshops, Nobody is Perfect

•Implementation and refinement of the ChCC electronic database and tracking system

2011-13

•New postnatal parental leave (up to 6 months)

•Workshops for promotion of motor and language development started

2014-17

•Expansion of ChCC to children up to age 9 with the Integrated Learning Support Programme

•Pilot of the Children’s Mental Health Programme

Structure, management, and financing

The ministries of health, education, and social development are responsible for administration and management of ChCC (box 3). The Ministry of Social Development is responsible for coordinating and managing the system at national, regional, and communal levels; it is represented in each region through the regional secretaries of social development. Coordination takes place across ministries and services at the same level (horizontal coordination) and across different levels of government from national to commune level (vertical coordination).

Box 3. Ensuring that ChCC reaches children at highest risk in Chile: expanding coverage of health, education, and social services.

Guaranteed healthcare services for all

The public health system is used by around 80% of the population and is free for lower income groups. Services are provided by the National Health Service System (SNSS) through a national network of hospitals and primary care centres linked with family health community centres and rural health posts, based on a family and community health plan17

Free education

Early education from 0 to 4 years is financed by both public and private bodies. ChCC guarantees by law that children from the lowest two wealth quintiles can access education free of charge, beginning with nursery care. At age 5 years, children attend kindergarten, the first mandatory educational level, and have free access to public schools.

Social protection

The social household registry is used to assign vulnerability ratings to households and so determine whether they qualify for benefits under the social protection system. By July 2017, the registry had ratings data of about 73% of the national population18

The social protection system includes psychosocial support for extremely poor families through the Security and Opportunities programme, preferential access to existing social programmes, and guaranteed access to subsidies or cash transfers provided by the state.19 ChCC is part of the social protection system, therefore allowing all those in need to receive benefits

ChCC is financed entirely by the public sector, with agreements governing the transfer of funds to sectoral ministries, local governments (municipalities), and private stakeholders. A ChCC budget line was established for the Ministry of Social Development in the budget law of the Chilean public sector. Resources are allocated to the ministries of health and education through resource transfer agreements, and to municipalities through direct transfer agreements. Ministries implement services as part of the ChCC portfolio through existing networks and systems. Direct transfer agreements with municipalities support activities such as hiring and training staff and providing supplies for services. Transfer agreements also specify technical standards that must be met by institutions, which make fund transfer agreements an important mechanism for managing the quality of services.

Institutions receiving funds are required to report monthly expenditures and to specify how resources were allocated within the framework of the agreements signed. Hence a system of continuous accountability and feedback is established, linked with funding availability. Use of the electronic ChCC database allows the progress of children along the continuum of care to be tracked using key indicators; problem areas can then be identified and managed (see the monitoring and evaluation section below). Routine national and regional supervision to municipalities allows feedback in both directions. Strengths can be identified and built on; weaknesses can be identified and managed collaboratively.

The basic communal networks of ChCC, consisting of health and education teams and coordinated by the municipality, are responsible for routine provision of preventive and curative services. Expanded networks include stakeholders from other municipal departments or local services that target children and their families. Communal networks are therefore responsible for coordinating cross sectoral services based on local resources available, geography, and any cultural factors needed to ensure services meet the needs of children and families.

Implementation

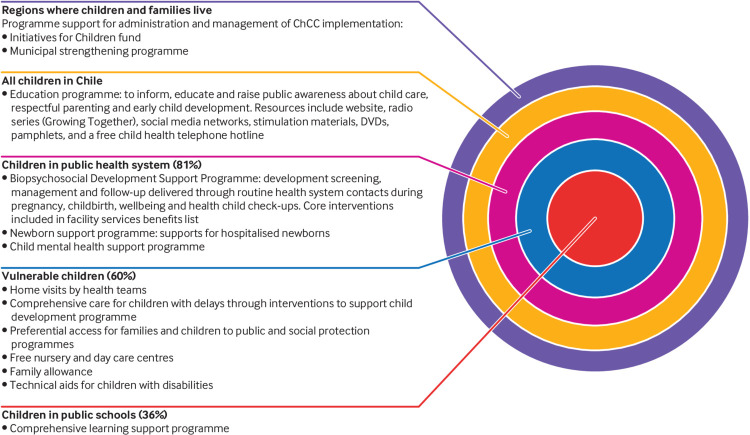

ChCC provides a public education programme on early child development for all families, caregivers, and providers using a website, social media platforms, a radio show, and print material (fig 1).

Fig 1.

Services provided by ChCC. Adapted from the Ministry of Social Development, Chile14

The targeted ChCC programme is provided for caregivers, families, and children entering the public health system, representing about 80% of the population. The remaining 20% of the population obtains health services from private providers through private insurance or occupational coverage. Other mechanisms are in place to ensure that those in lower income groups have access to care without high cost barriers to care (fig 1, box 3).20 21

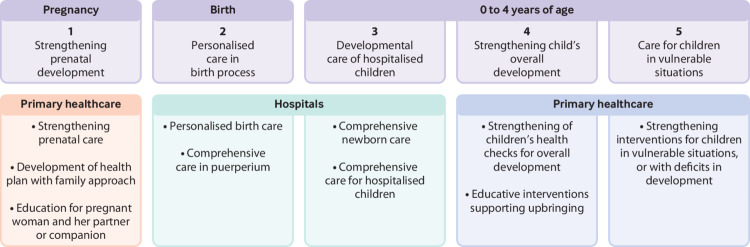

The core of the ChCC targeted approach is the Biopsychosocial Development Support Programme, which includes health checks during pregnancy, care during labour and birth, child health checks, screening for and timely treatment of developmental delays, care for hospitalised children, and child mental health using standardised tools (fig 2).22 For example, evidence based interventions at birth include provision of a birth companion of choice, immediate skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby, and early and exclusive breastfeeding—all associated with improved outcomes for both mother and baby.23 The ChCC programme updated facility policies, changed work environments, and supported staff training and supervision to move towards consistent adoption of key practices. Screening for developmental delay is done using a national test applied at each health check.22 Standardised screening also includes assessing maternal and family risk factors, such as low education, substance misuse, and depression. Targeted services are provided for children with developmental delays, including stimulation rooms, home visits, playgroups, and other services (box 4). Nobody is Perfect is a group education workshop for parents, mothers, and caregivers with children aged 0 to 5.25 It promotes positive parenting skills, mutual support by participants, prevention of child abuse and maltreatment, and co-responsibility in parenting using hands-on practice. Training of primary care staff for all screening and programme components of ChCC is done by national and municipal facilitators using materials and job aids based on national standards.

Fig 2.

Biopsychosocial support programme: services offered across the life cycle by ChCC Ministry of Social Development, Chile14

Box 4. Services provided for children assessed with psychomotor, cognitive, social, or communication delay.

•Primary services offered: stimulation rooms, home visiting, and a mobile stimulation service. Stimulation rooms can operate at health centres or community based spaces. One municipality can have one or more of each of the service modalities, depending on demand.

•Average duration of initial treatment: the average number of initial sessions is 6 with a mean duration of 45 minutes. At the end of the initial sessions, further treatment may be recommended or a referral made for further assessment and management

•Staffing: most of the staff working with children are nursery educators or teachers, phono audiologists, occupational therapists, kinesiologists, or other professionals with formal qualifications in child development

•Technical guidelines: guidelines for staff teams providing services to children been developed and are used nationally for staff orientation and training24

Equipment and materials: materials include a wall mirror, rubber mats, tulle or coloured gauze handkerchief mobiles, tunnels, balls of different sizes and textures, recorded music, books for children under 5, didactic toys with stimulation objectives (such as wooden blocks, rattles, musical instruments, dolls, food, animals), tables suitable for children, access ramps, and other relevant materials tailored to the culture or targeted area of delay

Additional services are provided for families with fewer resources or at greater risk: these include financial support, free nursery and preschool places, and preferential access to public programmes. Vulnerable families have access to free infant or toddler care for children under 2, and preschool places for children aged between 2 and 3. Such families represent around 60% of the population; vulnerability criteria include teen mothers and those with postpartum depression, substance misuse, lack of family support, and low levels of education.

The ChCC network should allow children and families with risk factors for vulnerability to be identified at any contact with health, education, and social services and referred across sectors. For example, the health sector may identify developmental delays requiring home visits; preschool nurseries may identify developmental problems requiring screening or a housing problem related to poverty that requires support by the municipality.

Monitoring, accountability, and learning

From the outset, the coordinating ministry developed a monitoring and evaluation plan for ChCC with two main components. The first is an electronic database of all pregnant women and all children entering the health system. This allows tracking of developmental assessments, core health interventions received, and progress across sectors. Clinic health workers enter data directly on to the database at each consultation. Data are managed centrally by the Ministry of Social Development. Key performance indicators are used to track completeness of reporting and outcomes for children classified with developmental delays. This system is used by staff in health, education, and social protection sectors to access and update information about the child’s development, activate the necessary services, and make intersectoral referrals. The second major component consists of periodic evaluations to assess the effectiveness of programme services or activities. To date, more than 30 studies have been undertaken on ChCC, with different methodologies and approaches, including both qualitative and quantitative user satisfaction, impact, and process studies.6 26

Summary of progress

Between 2007 and 2017, annual budgetary allocations for ChCC increased progressively, rising from $7.8m in 2007 to $13.9m in 2008, and reaching $81m in 2017.27 During this period, the number of pregnant women admitted to prenatal care under ChCC was 1 987 755, with the number of children under developmental observation in the public health system reaching 646 692 in 2017.28

By 2017, 94% of women registered in the public system received the newborn support package at birth and 94% received postnatal counselling, with significant increases in the number of comprehensive home visits for vulnerable pregnant women and children; improvements in prenatal, delivery, and postnatal practices; and increasing rates of preschool education attendance (table 1).29 30 In 2017, all registered children diagnosed with a deficit in psychomotor development were referred to stimulation rooms, with 75% of those completing treatment discharged without deficits.28

Table 1.

Key ChCC country indicators, 2007-18*

| Indicator | 2006-10 | 2011-14 | 2015-18 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total public expenditure—ChCC ($m, 2017) | 7.809 (2007) | 72.715 (2012) | 80.989 (2017) |

| Prenatal care | |||

| Home visits: pregnant women with psychosocial risk (total number) | 13 310 (2007) | 88 103 (2012) | 72 547 (2017) |

| Prenatal care with spouse, family member, or significant other (% of prenatal visits) | 18 (2008) | 30 (2014) | 34 (2017) |

| Delivery and early postpartum care | |||

| Birth companion (% deliveries) | — | 59 (2012) | 67 (2017) |

| Skin-to-skin contact for at least 30 minutes (% deliveries) | — | 52 (2010) | 76 (2017) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (% infants <6 months) | 49 (2008) | 43 (2012) | 57 (2017) |

| Early child home care and education | |||

| Home visits: children with psychomotor delay (total number) | 2 754 (2007) | 41 001 (2012) | 46 033 (2017) |

| Parents attending motor and language development workshops (% of parents of children <1 year) | 0 (2006) | — | 63 (2017) |

| Routine health visits for children 0-4 years attended by father (% of health visits) | 14 (2010) | 16 (2014) | 19 (2017) |

| Preschool education 0-3 years (% of children attending) | 12 (2006) | 26 (2011) | 29 (2015) |

| Preschool education 4-5 years (% of children attending) | 63 (2006) | 83 (2011) | 90 (2015) |

Source: Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Social Development, and Budget Directorate, Ministry of Finance, Chile. Year of data in brackets

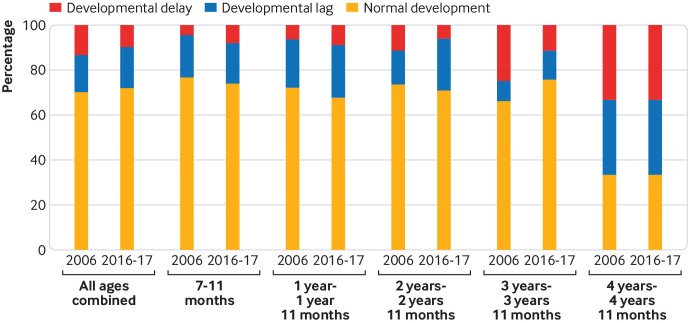

Between 2006 and 2016/17, the proportion of children under 5 with developmental delay declined nationally from 14% to 10%. Considerable variation was noted between age categories, with the most dramatic falls in developmental delay noted in children aged 2 (from 11.6% to 6.2%) and aged 3 (from 25.1% to 11.4%) (fig 3).31 In contrast, increasing proportions of children aged 7-11 months and 12-23 months were assessed with developmental delay. Data are not yet available by wealth quintile. These results are consistent with early intervention reducing developmental delay in older children. Evaluations of the biopsychosocial programme and the Nobody is Perfect parenting education programme have shown them to be effective at improving several measures of child development and parenting practice.32 33 Services targeting children with developmental delays have been shown to be cost effective.34 Of the beneficiaries, 73% describe ChCC as being fundamental to their personal experience of pregnancy and parenting, suggesting high levels of satisfaction.35

Fig 3.

Population based estimates of developmental status among children aged 6-59 months, Chile, 2006, and 2016-17 National Quality of Life and Health surveys, Ministry of Health, Chile, 2006 and 2016-179 31

Persistent developmental delays in younger age groups noted in the most recent population based survey raised questions about the coverage of interventions delivered around delivery and very early in life, especially for high risk groups. A review of these data by wealth quintile and for other higher risk categories is now required to determine whether these groups are being disproportionately missed by the system. In addition, the quality of early developmental screening and care for high risk children in younger age groups requires review to ensure that these services are effective in tackling family and environmental barriers to development, and that they are received in a timely fashion. Although most higher risk children in Chile enter the public health system, they may subsequently drop out of care or services may not deal with problems effectively.

Factors associated with implementation and scale-up

Introduction, adoption, acceptance

Three factors were essential for the introduction of ChCC. Firstly, political support at the highest levels of government, owing to active leadership by President Bachelet and other national authorities, allowed ChCC to be designated as one of Chile’s strategic objectives. Secondly, the evidence based design of the programme convinced both political and technical leaders of the importance and potential impact of interventions in this area. This included the use of data from disciplines such as neuroscience and developmental psychology to illustrate the high rate of return from investment in early childhood, aligning with the Convention on the Rights of the Child and focusing on the social determinants of health and the ecological model, Also, the needs of families were made central to the design of the programme.23 Thirdly, broad consensus was achieved, beginning with the work of the advisory council, which consulted experts with diverse political and technical perspectives. Consensus was reinforced by national and regional public hearings with stakeholders representing civil society, academia, the government, and children. Early consultation led to broad investment in the programme by all sectors and communities and a common understanding of its purpose.

Building on existing systems to allow expansion

Three factors have been identified as important for the successful expansion of ChCC. Firstly, ChCC built on existing systems which already promote collaboration between the health, social protection, and education sectors in Chile. Around 80% of babies in Chile are born in public hospitals and receive follow-up preventive and treatment care in the public health system. Existing systems therefore provided an entry point for most mothers and children and a gateway for ChCC activities. ChCC also built on the social protection programme established in all municipalities, which guarantees cross sectoral support for children and is managed at the local level (box 2). Secondly, the formation of a coordinating body in the Ministry of Social Development, which was experienced in managing social networks and promoting social development policies, promoted better coordination of activities in all sectors rather than focusing on the activities of one sector, which might have occurred if responsibility had been given to health or education agencies. The budget for ChCC implementation is also allocated to the Ministry of Social Development, which transfers funds to the ministries of health and education and directly to municipalities, based on performance standards and indicators. This has created a system of financial and technical accountability and has been important in setting and maintaining quality standards. Thirdly, an emphasis was placed on community driven programming through municipal networks. The programmes and services offered by ChCC require communal networks that are flexible, adapted to local needs, and coordinated with local actors. By giving financial and technical autonomy to municipalities, they can implement core services according to local systems and population differences.

Building sustainability and adapting to new challenges

ChCC has been operating for more than 10 years and has been implemented throughout the country. The sustainability of this public policy is due largely to the following factors: the institutionalisation of ChCC through Law 20 379; consistent budget allocations guaranteed by law (table 1); effective coordination both at national level by the Ministry of Social Development and at local level by motivated health and education teams with experience in implementing maternal and child health programmes, who have up-skilled to gain further developmental skills and competencies; collection and use of data for programme management and intersectoral coordination using the programme monitoring system; regular evaluation of programme components and use of data for improving services; and increasing focus on developing and implementing quality standards, which are used for both tracking progress and providing incentives. Quality standards led to the creation of a benefits list for the biopsychosocial support programme implemented by the Ministry of Health.

Limitations

ChCC must evolve in line with Chile’s changing health context and adapt to operational challenges to improve its efficiency and effectiveness. Several challenges have been identified for the next phase of implementation (table 2). ChCC systems need strengthening in some areas, including improving the efficiency and timeliness of fund transfers to municipalities and better integration of the monitoring system with other government data systems to allow data sharing. Some high risk groups do not always receive social services such as housing, employment assistance, or mental health services when required, and gaps need to be closed. Access to public services can be improved in some areas by changing the location and opening times of clinics and offices and by better promotion of care using social media platforms. Finally, new and emerging problems and demographic shifts in the country will require ChCC to adapt the range and type of services provided. These include management of childhood mental health problems, disabilities, and obesity, and the problems of new immigrants and indigenous populations. In the longer term there is a movement to expand ChCC services to older children aged 5-9.

Table 2.

Current strategies and emerging challenges for ChCC

| Aim | Current strategies under ChCC | Emerging challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Improving routine systems to support intersectoral services | • Use of existing public health system provides a gateway to services • Multisectoral coverage by the social protection system • Management by the Ministry of Social Development and fund transfer agreements for quality and accountability • Integrated electronic monitoring and evaluation system |

• Harmonise registration and monitoring system of ChCC with other government data systems to allow data sharing • Strengthen efficiency and timeliness of fund transfers for local activities, hiring staff, and meeting goals • Close gaps in the social protection system to ensure families receive housing, employment, mental health, or substance misuse treatment when required |

| Adapting to evolving problems | • Routine monitoring of biological and psychosocial risks of the family and child • Early intervention through the health system based on identified needs • Intersectoral links to foster appropriate care based on needs • Links with social protection services to ensure wider social problems, such as employment and housing, are tackled |

Recognise and adapt the developmental approach to demographic and social changes including: • Child mental health • Children with disabilities • Indigenous people • Obese and overweight children • Children and families of new immigrants • Children raised in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender families and transgender children |

| Improving parenting skills | • Nobody is Perfect parental education training offered to all mothers and families has been shown to improve general parenting skills | • Violence and maltreatment of children is believed to be widespread in Chile; more data are needed to allow better management • Better integrate interventions to promote caring and sensitive care across sectors |

| Reaching core populations better | • Access to care and education through routine prenatal, delivery, and postnatal contacts • Home visits to families and children identified as high risk, using intersectoral links • Many materials and web based links used for communication and education |

• Improve access to services (eg, by changing locations and opening times) • Better use of social media for follow-up and reinforcement of skills or education • Develop mechanisms to hear children’s views to improve services and communication |

| Expanding the target population | • ChCC is focused on the prenatal period and on children aged 0-4 years, the period of highest risk for development | • Local movement to expand ChCC to include children aged 5-9 through the education sector • Development of a formal policy promoting the rights of all children from birth to 18 years is under review |

Conclusions

ChCC has features of a complex adaptive system in which positive and negative feedback loops have a central role in the development and implementation of the programme.36 Features include communal networks with multiple formal and informal connections between sectors to foster coordination of services and adaptation to local needs. Local budgetary authority allows resources to be allocated in accordance with local priorities. Feedback loops are used in the research and evaluation system to monitor and improve operations. The intersectoral and participatory structure allows continuous feedback at local level to tackle gaps and problems. ChCC instituted a phased transition to a new model of practice and fostered emergent behaviour in this area through strong political will, evidence informed advocacy, consensus based policy development, and use of existing functional systems. Inter-connectedness within this network allowed progressive cultural change, which placed value on the principles of equity, coordination, and recognition that development needed attention. All of these features contributed to better uptake and effectiveness.

Key messages .

Chile Grows with You (Chile Crece Contigo, ChCC) introduced a new model of practice and fostered emergent behaviour in child development through political will, evidence informed advocacy, consensus based policy development, and use of existing functional systems

Health, social, and education teams coordinated by the municipality are responsible for monitoring the development of children and coordinating the provision of services targeted to each child and their family

Formation of a non-sectoral coordinating body—the Ministry of Social Development—improved management of social networks and promotion of social development policies, while direct transfer funding agreements promoted local accountability and quality

Institutionalisation of ChCC by Law 20 379 in 2009, guaranteed consistent and increasing budget allocations, systematic collection and use of data for programme management, and coordination of health, education, and social services

Acknowledgments

We thank the key informants who answered in-depth questions about child development programming, participants in the case study expert review meeting, and Jeanet Leguas and Vanesa Hernández of ChCC (Ministry of Social Development) for their support in collating key informant responses to questionnaires.

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Methods for case study

See www.bmj.com/multisectoral-collaboration for other articles in the series.

Contributors and sources:HM conceptualised the case study. CC, AT, and PV conducted field interviews and collected data and reports of the programme. CC, AT, and PV conducted the data synthesis. HM, JM, CC, AT, and PV drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript before finalisation. HM is the guarantor.

Competing interests: The authors have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare: AT was the national coordinator for ChCC during the period the case study was conducted; HM, CC, and PV have previously worked for the ChCC programme at national level. WHO Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health provided support for the work for this article. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of WHO.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a series proposed by the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH) hosted by the World Health Organization and commissioned by The BMJ, which peer reviewed, edited, and made the decision to publish the article with no involvement from PMNCH. Open access fees for the series are funded by WHO PMNCH.

References

- 1. Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LCH, et al. Lancet Early Childhood Development Series Steering Committee Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet 2017;389:77-90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Microdata Center, Department of Economics, University of Chile, Ministry of Social Development, National Institute of Statistics. Chile National Socioeconomic Characterization Survey 2015-2016. Ministry of Social Development, 2016.

- 3. National Institute of Statistics Chile: projections and estimations of the total country population, 1950-2050. National Institute of Statistics, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Gini estimates for Chile. 2018. https://data.oecd.org/chile.htm

- 5.Ministry of Health and National Institute of Statistics. Chile. Vital statistics system in Chile: summary and analysis. Yearbook of vital statistics for 2017. Ministry of Health and National Institute of Statistics, 2017. http://www.ine.cl/docs/default-source/publicaciones/2017/compendio-estadistico-2017.pdf?sfvrsn=6

- 6. Aguilera X, Castillo-Laborde C, Ferrari MND, Delgado I, Ibañez C. Monitoring and evaluating progress towards universal health coverage in Chile. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001676. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hertel-Fernandez AW, Giusti AE, Sotelo JM. The Chilean infant mortality decline: improvement for whom? Socioeconomic and geographic inequalities in infant mortality, 1990-2005. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:798-804. 10.2471/BLT.06.041848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bedregal P, Scharager J, Breinbahaur C, Solari J, Molina H. [A screening questionnaire to evaluate infant and toddler development]. Rev Med Chil 2007;135:403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ministry of Health Chile. Second quality of life and health survey. Ministry of Health, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behrman JR, Contreras D, Palma I, Puentes E. Wealth disparities for early childhood anthropometrics and skills: evidence from Chilean longitudinal data. University of Pennsylvania Population Center working paper (PSC/PARC):2015; WP2017-12. https://repofitory.upenn.edu/psc_publications/12

- 11.Presidential Advisory Council for the Reform of Childhood Policies in Chile. The future of children is always today. Proposals of the Presidential Advisory Council for the reform of childhood policies. Presidential Advisory Council, 2006. https://www.oei.es/historico/noticias/spip.php?article1793

- 12.Valenzuela P. Diagnosis of key elements of the design and installation of the subsystem of integral protection of Children Chile Grows with You. Considerations for the design of the universal system for the guarantee of the rights of children and adolescents. Working paper. National Council for Children, 2015.

- 13. Britto PR, Singh M, Dua T, Kaur R, Yousafzai AK. What implementation evidence matters: scaling-up nurturing interventions that promote early childhood development. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2018;1419:5-16. 10.1111/nyas.13720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ministry of Social Development Chile. Chile Grows with You, Unit of the Division of Promotion and Social Protection. What is Chile Grows with You? Ministry of Social Development, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Britto PR, Lye SJ, Proulx K, et al. Early Childhood Development Interventions Review Group, for the Lancet Early Childhood Development Series Steering Committee Nurturing care: promoting early childhood development. Lancet 2017;389:91-102. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31390-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Government of Chile Law No 20 379: creating the Intersectoral System of Social Protection and institutionalizes the Subsystem for the Integral Protection of Children “Chile Grows with You”. Government of Chile, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institute of Statistics. Chile. Statistical compendium. National Institute of Statistics, 2017 http://www.ine.cl/docs/default-source/publicaciones/2017/compendio-estadistico-2017.pdf?sfvrsn=6

- 18.Ministry of Social Development, Chile. Social development report 2017. Ministry of Social Development, 2017:123. http://www.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/pdf/upload/IDS2017.pdf

- 19.Ministry of Social Development. Chile. Social development report 2017, Santiago, Chile. Ministry of Social Development, 2017:93. http://www.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/pdf/upload/IDS2017.pdf

- 20.Executive Secretariat of Social Protection-MIDEPLAN, Executive Secretariat Component of Health-MINSAL. Four years growing together: history of the installation of the comprehensive child protection system Chile Grows with You 2006-2010. Ministry of Social Development and Ministry of Health, 2011. http://www.crececontigo.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/ChCC_MEMORIA.pdf

- 21. Torres A, Lopez Boo F, Parra V, et al. Chile Crece Contigo: Implementation, results, and scaling-up lessons. Child Care Health Dev 2018;44:4-11. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/cch.12519. 10.1111/cch.12519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministry of Social Development. Chile. ChCC’s portfolio of services 2018. Ministry of Social Development, 2018. http://www.crececontigo.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Catalogo-Prestaciones-ChCC-2018-Ok.pdf

- 23.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on newborn health: guidelines approved by the WHO Guidelines Review Committee (WHO/MCA/17.07). WHO, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Health. Chile. Technical guidelines for supporting child development: guidelines for local teams. Ministry of Health, 2012. http://www.crececontigo.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/ Orientaciones-tecnicas-para-las-modalidades-de-apoyo-al-desarrollo-infantil-Marzo-2013.pdf

- 25.Ministry of Health, Chile. Nobody’s Perfect parenting skills workshop for parents, mothers and caregivers of children 0-5 years. Ministry of Health, 2015. http://www.crececontigo.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/nep_padres-madres-cuidadores-2015.pdf

- 26.Ministry of Social Development. Chile. Materials for ChCC teams: Studies. Ministry of Social Development, 2018. http://www.crececontigo.gob.cl/material-de-apoyo/material-para-equipos-chile-crece-contigo/estudios/?filtroetapa=gestacion-y-nacimiento&filtrobeneficio

- 27.Ministry of Finance: budget directorate, Chile. Budget spent 2007-2017. Ministry of Finance, 2018. http://www.dipres.gob.cl/598/w3-propertyvalue-2129.html

- 28. Ministry of Social Development Chile. Routine ChCC monitoring data 2007-2017. Ministry of Social Development, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ministry of Health Chile. Routine public health information tracking data 2007-2017. Ministry of Health, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Education in Chile, Reviews of national policies for education. OECD Publishing, 2018. 10.1787/9789264284425-. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ministry of Health Chile. National quality of life and health survey, 2016/17. Ministry of Health, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Department of Public Health, Chile and Catholic University of Chile. Data collection and analysis of child development and its main social and economic determinants, on a group of children in the PADB within the context of the Chile Crece Contigo child protection subsystem. Department of Public Health and Catholic University of Chile, 2011. http://www.crececontigo.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/13-INFORME-FINAL_Evaluacion-PADB.pdf

- 33.Galasso E, Carneiro P, López García I, Cordero M, Bedregal P. Impact evaluation of program “Nobody is Perfect” results post-treatment. Final report. Ministry of Health, 2017.

- 34.Medwave studies. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of child development support modalities in the child protection system. Medwave Studies, 2013. http://www.crececontigo.gob.cl/wpcontent/uploads/2014/05/122013-Informe-Final-CE-CHCC-12-2013-OK.pdf

- 35.Datavoz Consulting. Evaluation of user satisfaction and establishment of a baseline for the Newborn Support Program. Santiago, Chile: Datavoz Consulting, July 2014. http://www.crececontigo.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/14Informe-Final-Satisfaccion-USUARIA-2014-Y-LINEA-BASE-sin-comentarios.pdf

- 36. Pérez-Escamilla R, Cavallera V, Tomlinson M, Dua T. Scaling up Integrated Early Childhood Development programs: lessons from four countries. Child Care Health Dev 2018;44:50-61. 10.1111/cch.12480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Methods for case study