Abstract

This study used data from 12 cultural groups in 9 countries (China, Colombia, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Philippines, Sweden, Thailand, and United States; N = 1,298) to understand the cross-cultural generalizability of how parental warmth and control are bidirectionally related to externalizing and internalizing behaviors from childhood to early adolescence. Mothers, fathers, and children completed measures when children were ages 8 to 13. Multiple-group autoregressive, cross-lagged structural equation models revealed that child effects rather than parent effects may better characterize how warmth and control are related to child externalizing and internalizing behaviors over time, and that parent effects may be more characteristic of relations between parental warmth and control and child externalizing and internalizing behavior during childhood than early adolescence.

A number of parenting theories emphasize that parenting involves behavioral aspects, such as control, restrictiveness, and permissiveness, as well as emotional aspects, such as warmth, acceptance, hostility, and rejection (see Bornstein, 2015; Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Early theories described parenting in relation to parental dominance versus submission and rejection versus acceptance (Symonds, 1939); detachment versus involvement and hostility versus warmth (Baldwin, 1955); strictness versus permissiveness and hostility versus warmth (Sears, Maccoby, & Levin, 1957); control versus autonomy and hostility versus love (Schaefer, 1959); and restrictiveness versus permissiveness and hostility versus warmth (Becker, 1964). Parenting typologies have used a two-by-two matrix depicting high versus low levels of warmth on one axis and high versus low levels of control on the other to differentiate authoritarian, permissive, neglecting, and authoritative parents on the basis of whether they are high or low on each dimension (Baumrind, 1967; Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Thus, dimensions broadly characterized as warmth and control have served as cornerstones in several major theories of parenting.

Parents’ warmth and control have been found to be related to several aspects of adolescents’ adjustment in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. For example, early research demonstrated that children of authoritative parents who are high in both warmth and control have higher levels of academic and social competence than children of authoritarian parents who are low in warmth or permissive parents who are low in control (Baumrind, 1971). More recent meta-analyses have demonstrated links between positive aspects of parenting (more warmth and less hostility) and more positive youth adjustment such as less relational aggression (Kawabata, Alink, Tseng, van IJzendoorn, & Crick, 2011) and fewer internalizing problems (Yap, Pilkington, Ryan, & Jorm, 2014). There has been more controversy in the literature about the role of control than the role of warmth in relation to adolescents’ adjustment. For example, differentiated perspectives on control have emerged to distinguish behavioral control (i.e., parents’ efforts to remain aware of, and potentially redirect, adolescents’ behavior) from psychological control (i.e., parents’ efforts to control adolescents’ thoughts and feelings), with somewhat controversial effects of behavioral control but detrimental effects of psychological control (Barber, Stolz, & Olsen, 2005). Meta-analyses have found robust links between psychological control and delinquency (Hoeve et al., 2009) and between monitoring (a form of behavioral control) and less risky adolescent sexual behavior (Dittus et al., 2015), although it can be difficult to distinguish between behavioral and psychological control in some measures.

Lack of appropriate behavioral control comes about because parents’ supervision and discipline are too lax, too harsh, or inconsistent, all of which are related to adolescents’ externalizing and internalizing problems (Davies & Cummings, 1994). In addition, parental rejection (lack of warmth) often involves negative emotions, intrusiveness, and withdrawal that predict adolescents’ own anger, dysphoria, withdrawal, and noncompliance, contributing to both externalizing and internalizing problems (Davies & Cummings, 1994). Adolescents are more willing to disclose information about their activities and whereabouts if they perceive their parents to be warm and supportive, which facilitates parents’ ability to exert appropriate behavioral control and decreases adolescents’ problem behaviors (Klevens & Hall, 2014). Parental warmth and support are also related to fewer depressive symptoms, perhaps in part because parental warmth boosts adolescents’ self-esteem and helps buffer them from life stress (Johnson & Greenberg, 2013).

Although the majority of theories and empirical studies focus on how parenting affects adolescents’ adjustment, transactional and reciprocal models emphasize that children and adolescents also elicit particular types of parenting (e.g., Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992; Sameroff, 1975). A large literature on child effects demonstrates that when children evince problems, their parents withdraw or become more authoritarian (e.g., Albrecht, Galambos, & Jansson, 2007; Reitz, Dekovic, & Meijer, 2006; Rueter & Conger, 1998; Stice & Barrera, 1995). For example, adolescent internalizing, externalizing, and academic achievement predict subsequent involvement from a nonresident father (Hawkins, Amato, & King, 2007). Over time, when adolescents engage in problem behavior, their parents become less warm and more hostile, whereas parents become warmer and less hostile over time when their adolescents are functioning more positively (Williams & Steinberg, 2011).

Several important theoretical perspectives now emphasize the importance of situating parenting within broader cultural contexts to be able better to understand the meaning imparted to children and adolescents by particular parenting behaviors (e.g., Bornstein, 2012; Harkness & Super, 2002; Rubin & Chung, 2006; see also Stein & Lippold, this issue). Empirical studies have investigated parental warmth and control in a number of countries and cultural groups. Focusing on different ethnic groups within the United States, Hill, Bromell, Tyson, and Flint (2007) argued that parental control and autonomy granting are shaped by cultural, neighborhood, and socioeconomic factors. For example, in five cultural groups (in Costa Rica, Thailand, and three racial groups in South Africa), traditional measures of psychological control were improved by the addition of items regarding adolescents’ perceptions of their parents’ disrespect (Barber, Xia, Olsen, McNeely, & Bose, 2012). Likewise, in a study of adolescents in 12 cultural groups from Africa, Asia, Australia, North and South America, Europe, and the Middle East, McNeely and Barber (2010) found that parents in all groups demonstrate love by providing rare and valued commodities, but the nature of these commodities (e.g., time, support for education) varied across groups. Associations between more parental warmth and fewer adolescent behavior problems have been demonstrated in many countries (see Khaleque & Rohner, 2002; Rohner & Lansford, in press).

In analyses using data from the same sample of participants as in the present study, when children were 8 years old, on average, warmth was found to correlate with control in different ways across nine countries (Deater-Deckard et al., 2011). For example, in Kenya, warmth and control were moderately to strongly positively correlated (r ranging from .44 to .85, depending on whether mothers, fathers, or children were reporting). By contrast, warmth and control were negatively correlated for European Americans in the United States (r ranging from −.35 to −.18). These different patterns of covariation between warmth and control in different cultural groups suggest that warmth and control may be related differently to youth adjustment depending on the broader context in which they are situated. Indeed, country or cultural context has been found to moderate links between parental warmth and control and child and adolescent outcomes (e.g., Louie, Oh, & Lau, 2013).

The Present Study

Although theories of parenting espouse the importance of situating parenting within broader cultural contexts (e.g., Bornstein, 2012), there have been few empirical tests of whether the tenets of major theories of parenting hold in diverse international contexts. In keeping with the theme of the Special Section, this study examines to what extent parenting theories that have been developed primarily with respect to relationships between parents and younger children extend into relationships between parents and adolescents—specifically to test central hypotheses related to how parental warmth and control are linked to youth outcomes based on theory. Further, this study tests whether bidirectional relations between parenting and youth outcomes vary based on the cultural context. We analyze data reported by mothers, fathers, and children in nine countries (China, Colombia, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Philippines, Sweden, Thailand, and the United States), annually for six years, beginning when children were 8 years old, on average. We test whether associations between parental warmth and control and subsequent child externalizing and internalizing behavior as well as associations between child externalizing and internalizing behavior and subsequent parental warmth and control are consistent across cultural groups. We also test whether parental warmth and control are consistently related to externalizing and internalizing behaviors from childhood to early adolescence or whether the relations vary with age.

Method

Participants

Participants included 1,298 children (M = 8.29 years, SD = .66, range = 7 to 10 years; 51% girls), their mothers (N = 1,275), and their fathers (n = 1,032) at wave 1 of 6 annual waves. Families were drawn from Shanghai, China (n = 121), Medellín, Colombia (n = 108), Naples, Italy (n = 100), Rome, Italy (n = 103), Zarqa, Jordan (n = 114), Kisumu, Kenya (n = 100), Manila, Philippines (n = 120), Trollhättan/Vänersborg, Sweden (n = 101), Chiang Mai, Thailand (n = 120), and Durham, North Carolina, United States (n = 111 European Americans, n = 103 African Americans, n = 97 Latin Americans). In total, participants represented 12 distinct ethnic/cultural groups across 9 countries. Participants were recruited through letters sent from schools. Initial response rates varied across countries (from 24% to nearly 100%), primarily because of differences in the schools’ roles in recruiting. Much higher participation rates were obtained in countries in which the schools were more involved in recruiting. For example, in the United States, we were allowed to bring recruiting letters to the schools, and classroom teachers were asked to send the letters home with children. Children whose parents were willing for us to contact them to explain the study were asked to return a form to school with their contact information. We were then able to contact those families to try to obtain their consent to participate, scheduling interviews to take place in participants’ homes (yielding a 24% participation rate). By contrast, in China, once the schools agreed to participate, the schools informed parents that the school would be participating in the study and allowed our researchers to use the school space to conduct the interviews. Nearly 100% of the parents in the Chinese sample agreed to participate once the schools informed them of the schools’ participation.

Most parents (82%) were married, and nonresidential parents were able to provide data. Nearly all were biological parents, with 3% being grandparents, stepparents, or other adult caregivers. Sampling focused on including families from the majority ethnic group in each country; the exception was in Kenya where we sampled Luo (3rd largest ethnic group, 13% of population), and in the United States, where we sampled equal proportions of European American, African American, and Latin American families. To ensure economic diversity, we included students from private and public schools and from high- to low-income families, sampled in proportions representative of each recruitment area. Child age and gender did not vary across countries. Data for the present study were drawn from interviews at the time of recruitment as well as one, two, four, and five years after recruitment (at waves 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 of the larger study because these were the times at which data relevant to the current questions were collected). Retention rates were very high: At the follow-up interview five years after the initial interviews, 93% of the original sample continued to provide data. Participants who provided follow-up data did not differ from the original sample with respect to child gender, parents’ marital status, or mothers’ education. Table 1 provides descriptive information about the demographics of the samples at the time of recruitment.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Demographics by Cultural Group

| Group | Mother’s Education | Father’s Education | Child Gender (% girls) | Child Age at Recruitment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shanghai, China | 13.55 (2.88) | 14.00 (3.07) | 52 | 8.51 (.34) |

| Medellín, Colombia | 10.64 (5.60) | 9.91 (5.32) | 56 | 8.22 (.49) |

| Naples, Italy | 10.14 (4.35) | 10.73 (4.16) | 52 | 8.31 (.49) |

| Rome, Italy | 14.14 (4.07) | 13.75 (4.09) | 50 | 8.34 (.77) |

| Zarqa, Jordan | 13.13 (2.18) | 13.24 (3.16) | 47 | 8.47 (.50) |

| Kisumu, Kenya | 10.69 (3.65) | 12.29 (3.60) | 60 | 8.45 (.65) |

| Manila, Philippines | 13.61 (4.07) | 13.90 (3.84) | 49 | 8.03 (.35) |

| Trollhättan, Sweden | 13.92 (2.48) | 13.73 (2.98) | 48 | 7.77 (.42) |

| Chiang Mai, Thailand | 12.30 (4.76) | 12.76 (4.22) | 49 | 7.71 (.63) |

| U.S. African American | 13.65 (2.36) | 13.45 (2.66) | 52 | 8.60 (.61) |

| U.S. European American | 16.95 (2.84) | 17.29 (3.04) | 41 | 8.63 (.57) |

| U.S. Latino | 9.83 (4.08) | 9.61 (3.90) | 54 | 8.58 (.74) |

Note. Mother’s and father’s education = mean number of years of education completed (SD).

Procedure and Measures

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics for all substantive measures. Measures were administered in the predominant language of each country, following forward- and back-translation and meetings to resolve any item-by-item ambiguities in linguistic or semantic content (Erkut, 2010). Translators were fluent in English and the target language. In addition to translating the measures, translators noted items that did not translate well, were inappropriate for the participants, were culturally insensitive, or elicited multiple meanings and suggested improvements (Maxwell, 1996; Peña, 2007). Country coordinators and the translators reviewed the discrepant items and made appropriate modifications. Measures were administered in Mandarin Chinese (China), Spanish (Colombia and the United States), Italian (Italy), Arabic (Jordan), Dholuo (Kenya), Filipino (the Philippines), Swedish (Sweden), Thai (Thailand), and American English (the United States and the Philippines).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Substantive Measures, Full Sample (N = 1,298).

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Parental Warmth | ||

| Age 8 | 3.57 | 0.36 |

| Age 9 | 3.59 | 0.35 |

| Age 10 | 3.58 | 0.37 |

| Age 12 | 3.56 | 0.38 |

| Age 13 | 3.61 | 0.39 |

| Parental Control | ||

| Age 8 | 2.98 | 0.41 |

| Age 9 | 2.94 | 0.42 |

| Age 10 | 2.88 | 0.41 |

| Age 12 | 2.85 | 0.44 |

| Age 13 | 2.83 | 0.51 |

| Child Externalizing | ||

| Age 8 | 10.19 | 5.28 |

| Age 9 | 9.52 | 5.46 |

| Age 10 | 9.01 | 5.54 |

| Age 12 | 9.21 | 5.98 |

| Age 13 | 8.03 | 7.03 |

| Child Internalizing | ||

| Age 8 | 11.48 | 5.44 |

| Age 9 | 10.37 | 5.63 |

| Age 10 | 9.62 | 5.34 |

| Age 12 | 10.39 | 6.00 |

| Age 13 | 9.02 | 6.90 |

Interviews lasted 1.5 to 2 hours at each wave and were conducted in participants’ homes, schools, or at other locations chosen by the participants. Procedures were approved by local Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at universities in each participating country. Mothers and fathers provided written informed consent, and children provided assent. Family members were interviewed separately to ensure privacy. At the first assessment point (when children were 8 years old), all interviews for parents as well as children were conducted orally. In subsequent years, parents were given the choice of completing the measures in writing or orally, with the interviewer reading the questions aloud and recording the participants’ responses (with a visual aid to help the participants understand the response scales). The measures were administered to children orally until the age of 10; after that point, children were given the option of completing the measures orally or in writing. Children were given small gifts or monetary compensation to thank them for their participation, and parents were given modest financial compensation, families were entered into drawings for prizes, or modest financial contributions were made to children’s schools.

Parental warmth and control

When children were ages 8, 9, 10, 12, and 13 (on average), mothers and fathers completed the Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire-Short Form (PARQ; Rohner, 2005). Children completed the child-report version of the measure when they were ages 8, 9, 10, and 12 (on average), providing separate ratings about their mothers and fathers. The measure includes 8 items capturing parental warmth (e.g., parents saying nice things to and taking a real interest in the child) and 5 items capturing behavioral control (e.g., parents insisting on complete obedience). Parents and children rated the frequency of each behavior on a modified 4-point scale (1 = never or almost never, 2 = once a month, 3 = once a week, or 4 = every day). In a meta-analysis of the reliability of the PARQ using data from 51 studies in 8 countries, Khaleque and Rohner (2002) concluded that internal consistency (α) reliabilities exceeded .70 in all groups, effect sizes were homogenous across groups, and convergent and discriminant validity were demonstrated (Rohner, 2005). We found strong internal consistency for this measure across reporters in the present sample (αs = .84 to .89; see Putnick et al., 2015, for additional information). For this study, we used the family mean of parental warmth and control, which was the average of child and parent reports of each construct at each wave.

Child externalizing and internalizing behaviors

Mothers and fathers completed Achenbach’s (1991) Child Behavior Checklist when children were ages 8-10 and 12-13. Children completed the Youth Self Report (Achenbach, 1991) at ages 8-10 and 12. Participants were asked to rate how true each item was of the child during the last six months (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very or often true). The Externalizing Behavior scale summed across 33 items (for parent reports) or 30 items (for youth reports) capturing behaviors such as lying, truancy, vandalism, bullying, drug and alcohol use, disobedience, tantrums, sudden mood change, and physical violence. The Internalizing Behavior scale summed across 31 items (for parent reports) or 29 items (for youth reports) measuring behaviors and emotions such as loneliness, self-consciousness, nervousness, sadness, and anxiety. The Achenbach measures are among the most widely used instruments in international research, with translations in over 100 languages and strong, well-documented psychometric properties (e.g., Achenbach & Rescorla, 2006). As reported by Putnick et al. (2015), both Internalizing Behavior (α = .84 to .87) and Externalizing Behavior (α = .84 to .88) scale scores demonstrated strong internal consistency in the present sample. For this study, we used the family mean of child externalizing and internalizing behavior, which was the average of child and parent reports of each construct at each wave.

Demographic control variables

Child gender and number of years of mother and father education at the first time point examined in the current study (i.e., when children were 8 years old) were included in study analyses as covariates.

Analysis Plan

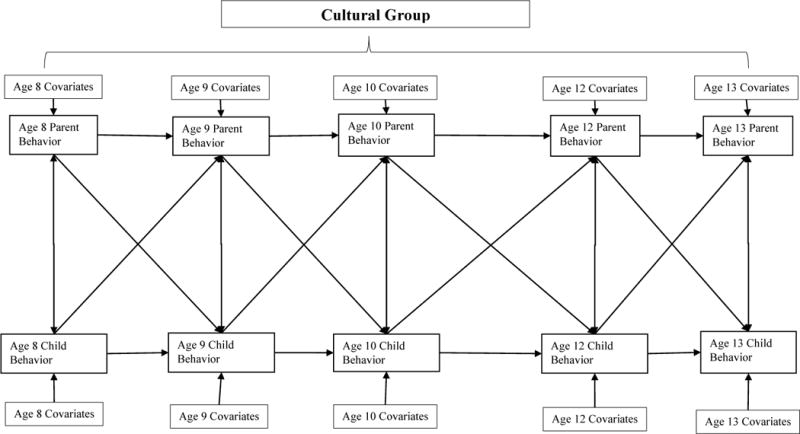

We utilized an autoregressive, cross-lagged structural equation modeling framework in Mplus Version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015) to evaluate study hypotheses (see Figure 1). These analyses proceeded in a series of steps. First, mean scores were computed from all available mother, father, and child reports on parental warmth, parental control, child externalizing, and child internalizing behaviors at each time point (e.g., mother self-report, father self-report, child-report on mother, and child-report on father responses were combined to create a wave 1 parental warmth variable). Using mean scores as observed indicators in the model dramatically helps with model estimation and power by bolstering the model’s sample-size-to-parameters ratio (Kline, 2011), which became especially important in subsequent steps of the analysis. Additionally, the decision to combine reports at each time point to compute mean scores was substantively supported by significant correlations among mother, father, and child reports of parental warmth (rs = .21-.70, p < .01), parental control (rs = .18-.62, p < .01), child externalizing (rs = .25-.60, p < .01), and child internalizing (rs = .19-.43, p < .01) across all time points. This decision was further supported by high levels of interrater consistency in each of these constructs across cultural groups, as only 2 of 48 measures of interrater consistency fell below .70 across mother, father, and child reports in each of the 12 cultural groups (see Table 3). These significant correlations and interrater consistencies across cultural group indicated that mother, father, and child reports were associated closely and suitable for mean-score estimation. Alternative models in which latent variables were estimated for warmth, control, externalizing, and internalizing behaviors at each wave were explored but ultimately abandoned due to difficulties with model convergence and fit, largely as a consequence of attempting to estimate 5 latent variables per construct (one for each time point) across 12 different cultural groups.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model depicting framework for study analyses. Each of the 4 final analytic models examined longitudinal associations between a parent behavior (either warmth or control) and a child behavior (either externalizing or internalizing) across 12 different cultural groups. Cross-lagged paths examined principal study hypotheses. However, to ensure the robustness of significant cross-lagged paths, other depicted paths were controlled for in all models. These include time-specific associations with study covariates (i.e., child gender, mother education, and father education), stability in parent and child behavior over time (as depicted by the autoregressive paths), and contemporaneous associations between parent and child behavior. Finally, associations between measures at non-adjacent time points (e.g., child behavior at age 8 and 10) were also controlled for but not depicted here for simplicity of presentation.

Table 3.

Interrater Consistency for Substantive Measures in Each Cultural Group (N = 1298).

| Substantive Measure

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Group | Parent Warmth (α) | Parent Control (α) | Child Externalizing Behavior (α) | Child Internalizing Behavior (α) |

| United States, European American | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.87 |

| United States, African American | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.91 | 0.87 |

| United States, Latin American | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.90 | 0.85 |

| China, Shanghai | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.84 |

| Italy, Naples | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.83 |

| Italy, Rome | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.88 |

| Kenya | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.79 | 0.73 |

| Philippines | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.91 | 0.84 |

| Thailand | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.88 | 0.80 |

| Sweden | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.86 |

| Colombia | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.85 |

| Jordan | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.91 | 0.87 |

After mean scores were created, separate linear regression models testing the unique associations of study covariates (i.e., mother education, father education, and child gender) with parental warmth, parental control, child internalizing, and child externalizing behaviors at each time point across waves were examined (e.g., in one such model, age 8 externalizing behavior was regressed on child gender, mother education, and father education). Covariates with associations significant at p < .10 with any of our outcome variables at a particular time point were retained in subsequent analyses; all others were trimmed from further hypothesis testing to ensure model parsimony (e.g., if child gender was significantly associated with child externalizing behavior at age 10, but not age 12, then the association between these two variables at age 10 was retained in further analyses, but the association at age 12 was trimmed).

Next, four separate structural models exploring longitudinal associations between (a) parental warmth and child externalizing behavior, (b) parental warmth and child internalizing behavior, (c) parental control and child externalizing behavior, and (d) parental control and child internalizing behavior were each estimated utilizing full information maximum likelihood estimation procedures to handle missing data (Enders, 2010). The general structure of each of these models is depicted in Figure 1. Each model was autoregressive (e.g., in the parental warmth models, age 13 warmth was regressed on age 12 warmth, which was regressed on age 10 warmth, etc.) and cross-lagged (e.g., in the parental warmth-child externalizing behavior model, parental warmth at age 8 predicted child externalizing behavior at age 9, and child externalizing behavior at age 8 also predicted parental warmth at age 9; see Figure 1). Thus, these models allowed us to test both parent- and child-driven effects—that is, how child behavior at one wave predicts parenting at the next wave and how parenting at one wave predicts child behavior at the next. Additionally, to account for contemporaneous shared-method variance, correlations between contemporaneous measures were specified in each model (e.g., parental warmth and child externalizing behavior at age 8 were correlated; see Figure 1). Furthermore, to improve stability and fit, paths between different measures of each construct at non-adjacent time points were added to each model (e.g., parental warmth at age 8 was associated with warmth at ages 10, 12, and 13 in addition to predicting age 9 parental warmth).

Once the four structural models were fit, multiple-group comparison analyses at the level of the cultural group (12 groups total) were conducted to examine differences in models across cultural groups. Following procedures established in our prior work (Coauthor et al., 2017), all paths in each of the four models were initially constrained to be equal across all cultural groups. Then, for each of the four models, paths were iteratively freed to vary across cultural groups. A path was allowed to vary freely across cultural groups if a χ2 difference test revealed that the model fit significantly better with the path freed than when it was constrained to be equal across cultural groups.

Paths were freed to vary across culture and tested using χ2 difference tests in the same order in every model. First, all paths associating covariates with parenting and child behavior constructs were freed at once and tested. Second, all correlations between contemporaneous measures, and correlations between different measures of each construct at non-adjacent time points were freed at once and tested. Third, each autoregressive stability path was freed one-at-a-time and tested across cultural group. Fourth and finally, each cross-lagged path was freed one-at-a-time and tested across cultural group. We iteratively freed paths in this way (i.e., waiting to free cross-lagged paths until last) to ensure we were conservative in the reporting of our significant findings. In other words, we wanted to be sure that, if there were any significant similarities or differences in our cross-lag paths across culture (which represented tests of our core study questions), that those significant differences were “real” and not just a misappropriation of variance that was better accounted for by freeing other paths across groups. Crucially, however, we also conducted sensitivity analyses wherein the cross-lagged paths were the first paths freed to vary across groups, and the results were identical. Therefore, we are fairly confident stability and differences in cross-lagged paths in this study are robust and valid.

Analyzing the data in this way was advantageous for answering our study questions, as it allowed us to identify with precision the age-specific paths that might vary (or not) across cultural groups. Results from the final autoregressive path models are depicted in Tables 4–7. Notably, all significant cross-lagged associations depicted in Tables 4–7 and discussed below remained after controlling for demographic, autoregressive, and contemporaneous correlates.

Table 4.

Autoregressive Cross-Lagged Associations Between Parental Warmth and Child Externalizing Across 12 Different Cultural Groups.

| Externalizing Regressed on Warmth (Parenting Effects)

|

Warmth Regressed on Externalizing (Child Effects)

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

a8 Warmth --> 9 Externalizing |

a9 Warmth --> 10 Externalizing |

a10 Warmth --> 12 Externalizing |

a12 Warmth --> 13 Externalizing |

a8 Externalizing--> 9 Warmth |

a9 Externalizing --> 10 Warmth |

a10 Externalizing --> 12 Warmth |

b12 Externalizing --> 13 Warmth |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Country/Culture | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |||||

| USEA | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 | ** | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.11 | 0.04 | ** | −0.23 | 0.05 | *** | −0.17 | 0.05 | *** | −0.06 | 0.11 | |

| USAA | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.01 | ** | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.12 | 0.04 | ** | −0.18 | 0.04 | *** | −0.13 | 0.04 | *** | −0.13 | 0.12 | |

| USLA | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.02 | ** | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.03 | ** | −0.10 | 0.02 | *** | −0.12 | 0.03 | *** | −0.19 | 0.14 | |

| China | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.03 | ** | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.02 | ** | −0.06 | 0.01 | *** | −0.07 | 0.02 | *** | −0.18 | 0.13 | |

| Italy, Naples | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.02 | ** | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.03 | ** | −0.12 | 0.02 | *** | −0.09 | 0.02 | *** | 0.10 | 0.09 | |

| Italy, Rome | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.02 | ** | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.02 | ** | −0.10 | 0.02 | *** | −0.09 | 0.02 | *** | 0.10 | 0.10 | |

| Kenya | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.04 | ** | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.02 | ** | −0.07 | 0.01 | *** | −0.10 | 0.03 | *** | −0.03 | 0.11 | |

| Philippines | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.02 | ** | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.02 | ** | −0.11 | 0.02 | *** | −0.12 | 0.03 | *** | 0.05 | 0.09 | |

| Thailand | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.03 | ** | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.02 | ** | −0.08 | 0.02 | *** | −0.07 | 0.02 | *** | 0.04 | 0.09 | |

| Sweden | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.02 | ** | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.03 | ** | −0.13 | 0.03 | *** | −0.09 | 0.03 | *** | −0.08 | 0.12 | |

| Colombia | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.02 | ** | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.03 | ** | −0.14 | 0.03 | *** | −0.08 | 0.02 | *** | −0.42 | 0.11 | *** |

| Jordan | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.02 | ** | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.02 | ** | −0.11 | 0.02 | *** | −0.11 | 0.03 | *** | −0.09 | 0.09 | |

Note:

p ≤ .001;

p ≤ .01. USEA = US European American sample. USAA = US African American sample. USLA = US Latin American sample. Coefficients are standardized.

Parameter was constrained to equality across cultural groups without significantly worsening model fit; slight variation in parameter estimates across cultural groups arises in the context of standardized coefficients.

Parameter was not constrained to equality across cultural groups to improve model fit.

Table 7.

Autoregressive Cross-Lagged Associations Between Parental Control and Child Internalizing Across 12 Different Cultural Groups.

| Internalizing Regressed on Control (Parenting Effects)

|

Control Regressed on Internalizing (Child Effects)

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

a8 Control --> 9 Internalizing |

a9 Control --> 10 Internalizing |

a10 Control --> 12 Internalizing |

a12 Control --> 13 Internalizing |

a8 Internalizing --> 9 Control |

a9 Internalizing --> 10 Control |

a10 Internalizing --> 12 Control |

a12 Internalizing --> 13 Control |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Country/Culture | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | ||||

| USEA | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | * | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.02 | ** | 0.05 | 0.02 | * | 0.07 | 0.02 | ** | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| USAA | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.03 | * | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.03 | ** | 0.06 | 0.03 | * | 0.06 | 0.02 | ** | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| USLA | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | * | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.03 | ** | 0.05 | 0.03 | * | 0.11 | 0.04 | ** | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| China | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | * | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.03 | ** | 0.07 | 0.03 | * | 0.11 | 0.04 | ** | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Italy, Naples | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.03 | ** | 0.06 | 0.03 | * | 0.08 | 0.03 | ** | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Italy, Rome | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.03 | ** | 0.05 | 0.02 | * | 0.09 | 0.03 | ** | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Kenya | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | * | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.03 | ** | 0.05 | 0.02 | * | 0.05 | 0.02 | ** | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Philippines | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | * | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.03 | ** | 0.06 | 0.03 | * | 0.09 | 0.03 | ** | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Thailand | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.03 | ** | 0.06 | 0.03 | * | 0.08 | 0.03 | ** | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Sweden | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.03 | * | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.02 | ** | 0.03 | 0.02 | * | 0.05 | 0.02 | ** | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Colombia | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.03 | ** | 0.07 | 0.04 | * | 0.08 | 0.03 | ** | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Jordan | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.03 | ** | 0.05 | 0.03 | * | 0.09 | 0.03 | ** | −0.02 | 0.03 |

Note:

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .05. USEA = US European American sample. USAA = US African American sample. USLA = US Latin American sample. Coefficients are standardized.

Parameter was constrained to equality across cultural groups without significantly worsening model fit; slight variation in parameter estimates across cultural groups arises in the context of standardized coefficients.

Results

Findings from each of the four final models will be discussed in turn. Skewness and kurtosis estimates for all mean scores fell in acceptable ranges (skew < 2.0, kurtosis < 7.0), suggesting no violation of the assumption of normally distributed indicators. Evaluation of model fit was based upon recommended fit index cut-off values that indicate excellent model fit (Comparative Fit Index (CFI)/Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) cut-off values > 0.95, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) cut-off value < 0.05, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) cut-off value < .08; Schreiber, Stage, King, Nora, & Barlow, 2006). Standardized parameter estimates and standard errors are provided in Tables 4–7. Therefore, notable results will be described below, but readers are referred to Tables 4–7 for greater detail. Effects of demographic covariates (i.e., child gender, mother and father education) are not presented individually in the text or tables because the vast majority of demographic covariates included in the final models were non-significant and numerous. For instance, in the Parent Warmth-Child Externalizing Model, 14 total covariate effects were found significant in initial regression analyses (as described in the Analysis Plan) and therefore estimated in each of 12 separate cultural groups in the final multi-group model, leading to a total of 168 covariate effects estimated. However, only 12 (7%) of those effects remained significant in the final multi-group model. Therefore, reporting each individual covariate effect in all four models seemed both inefficient (because most were non-significant in final models) and untenable (due to space limitations).

The few covariates that were significant in final models did not display any noticeable patterns of significance at particular time points or within particular cultural groups. When effects were significant, however, they were associated with study constructs in expected directions. Across the four final models, child gender was occasionally significantly associated with both externalizing and internalizing child behavior such that boys demonstrated greater externalizing symptoms and girls demonstrated greater internalizing symptoms. Child gender did not seem to be associated with differences in parental warmth or control. Similarly, mother and father education were only occasionally associated with child behavior and parenting behavior across the four final models. More years of mother and father education were associated with greater parental warmth, less parental control, and less child externalizing and internalizing behavior. Despite the fact that most covariate effects were non-significant in the final models, controlling for child gender and parent education in these analyses is necessary to demonstrate the robustness of significant findings. To that end, it is important to note that all significant effects reported in Tables 4–7 emerged from final models that controlled for such covariates.

Parental Warmth – Child Externalizing Behavior Model

The final model (Table 4) fit the data well (χ2 [413] = 505.55, p < .01, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.09) and substantially better than the initial model that was constrained to be equal across groups (χ2 [440] = 905.75, p < .01). In the final model, all paths were freed to vary across cultural groups except for several cross-lagged paths. Specifically, all four cross-lagged paths predicting child externalizing behavior from parental warmth, and three of the four cross-lagged paths predicting parental warmth from child externalizing behavior (with the lone exception being age 12 child externalizing behavior predicting age 13 parental warmth) were constrained to be equal across groups. Freeing these cross-lagged paths to vary across groups did not significantly improve model fit. Several notable results with regards to cross-lagged paths depicting child effects on subsequent parenting and cross-lagged paths depicting parenting effects on subsequent child behavior emerged.

With regard to child effects, in each cultural group, child externalizing behavior at ages 8, 9, and 10 was significantly negatively associated with subsequent parental warmth at ages 9, 10, and 12, respectively (Table 4). These results indicate that high child externalizing behavior at each of these ages predicts lower parental warmth at the next age. Additionally, for the Colombian cultural group, this negative association was also found between child externalizing behavior at age 12 and parental warmth at age 13.

With regard to parenting effects, in each cultural group, parental warmth at age 9 was negatively associated with child externalizing behavior at age 10, indicating that high parental warmth was associated with subsequent lower child externalizing behavior. No other significant effects of parental warmth on subsequent child externalizing behavior were found.

Parental Warmth – Child Internalizing Behavior Model

The final model (Table 5) fit the data significantly better than the initial model that was constrained to be equal across groups (χ2 [451] = 907.45, p < .01). This model fit the data well (χ2 [413] = 505.55, p < .01, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.08). In the final model, all paths were freed to vary across cultural groups except for several cross-lagged paths. Specifically, all four cross-lagged paths predicting child internalizing behavior from parental warmth, and paths from age 8 internalizing behavior to age 9 parental warmth and from age 10 internalizing behavior to age 12 parental warmth were constrained to be equal across groups. Freeing these cross-lagged paths to vary across group did not significantly improve model fit. Several noteworthy results with regards to cross-lagged paths depicting child effects on subsequent parenting and parenting effects on subsequent child behavior emerged.

Table 5.

Autoregressive Cross−Lagged Associations Between Parental Warmth and Child Internalizing Across 12 Different Cultural Groups.

| Internalizing Regressed on Warmth (Parenting Effects)

|

Warmth Regressed on Internalizing (Child Effects)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

a8 Warmth --> 9 Internalizing |

a9 Warmth --> 10 Internalizing |

a10 Warmth --> 12 Internalizing |

a12 Warmth --> 13 Internalizing |

a8 Internalizing --> 9 Warmth |

b9 Internalizing --> 10 Warmth |

a10 Internalizing --> 12 Warmth |

b12 Internalizing --> 13 Warmth |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Country/Culture | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | ||||||

| USEA | −0.03 | 0.01 | * | −0.03 | 0.02 | * | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.04 | * | −0.08 | 0.07 | −0.10 | 0.05 | * | −0.04 | 0.10 | ||

| USAA | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.04 | * | −0.34 | 0.11 | ** | −0.05 | 0.03 | * | −0.20 | 0.11 | |

| USLA | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.03 | 0.02 | * | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.03 | * | −0.35 | 0.09 | *** | −0.07 | 0.03 | * | 0.03 | 0.12 | |

| China | −0.05 | 0.02 | * | −0.05 | 0.02 | * | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.07 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.03 | * | −0.24 | 0.12 | * | |

| Italy, Naples | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.03 | * | −0.21 | 0.07 | ** | −0.06 | 0.03 | * | 0.17 | 0.09 | |

| Italy, Rome | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.03 | * | −0.01 | 0.09 | −0.06 | 0.03 | * | −0.06 | 0.09 | ||

| Kenya | −0.09 | 0.05 | * | −0.09 | 0.05 | * | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | 0.00 | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.03 | * | −0.03 | 0.11 | ||

| Philippines | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.05 | 0.02 | * | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.02 | * | −0.08 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.03 | * | −0.06 | 0.09 | ||

| Thailand | −0.06 | 0.03 | * | −0.06 | 0.03 | * | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.19 | 0.07 | * | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.07 | 0.10 | |

| Sweden | −0.06 | 0.03 | * | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.04 | * | −0.18 | 0.08 | * | −0.06 | 0.03 | * | −0.06 | 0.12 | |

| Colombia | −0.02 | 0.01 | * | −0.05 | 0.03 | * | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.03 | * | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.02 | * | −0.19 | 0.10 | ||

| Jordan | −0.05 | 0.03 | * | −0.05 | 0.03 | * | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.02 | * | −0.17 | 0.08 | * | −0.05 | 0.02 | * | −0.22 | 0.08 | ** |

Note:

p ≤ .001;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .05. USEA = US European American sample. USAA = US African American sample. USLA = US Latin American sample. Coefficients are standardized.

Parameter was constrained to equality across cultural groups without significantly worsening model fit; slight variation in parameter estimates across cultural groups arises in the context of standardized coefficients.

Parameter was not constrained to equality across cultural groups to improve model fit.

With regard to child effects, in each cultural group, child internalizing behavior at ages 8 and 10 was significantly negatively associated with subsequent parental warmth at ages 9 and 12, respectively (Table 5). These results indicate that high child internalizing behavior at each of these ages predicts lower parental warmth at the next age. Additionally, for several but not all cultural groups, this negative association was found between child internalizing behavior at ages 9 and 12 and parental warmth at ages 10 and 13, respectively.

With regards to parenting effects, in each cultural group, parental warmth at ages 8 and 9 was negatively associated with child internalizing behavior at ages 9 and 10, respectively, indicating that high parental warmth was associated with subsequent lower child internalizing behavior. No other significant effects of parental warmth on subsequent child internalizing behavior were found.

Parental Control – Child Externalizing Behavior Model

The final model (Table 6) fit the data significantly better than the initial model that was constrained to be equal across groups (χ2 [473] = 816.61, p < .01) and fit the data well (χ2 [376] = 425.59, p = .04, RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.07). In the final model, all paths were freed to vary across cultural groups except for the eight cross-lagged paths. Freeing these cross-lagged paths to vary across groups did not significantly improve model fit. Significant cross-lagged paths depicting child effects on subsequent parenting and parenting effects on subsequent child behavior are discussed below.

Table 6.

Autoregressive Cross-Lagged Associations Between Parental Control and Child Externalizing Across 12 Different Cultural Groups.

| Externalizing Regressed on Control (Parenting Effects)

|

Control Regressed on Externalizing (Child Effects)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

a8 Control --> 9 Externalizing |

a9 Control --> 10 Externalizing |

a10 Control --> 12 Externalizing |

a12 Control --> 13 Externalizing |

a8 Externalizing --> 9 Control |

a9 Externalizing --> 10 Control |

a10 Externalizing --> 12 Control |

a12 Externalizing --> T13Control |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Country/Culture | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |||

| USEA | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.03 | *** | 0.08 | 0.03 | *** | 0.11 | 0.03 | *** | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| USAA | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.04 | *** | 0.10 | 0.03 | *** | 0.14 | 0.04 | *** | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| USLA | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.03 | *** | 0.07 | 0.02 | *** | 0.16 | 0.04 | *** | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| China | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.03 | *** | 0.08 | 0.03 | *** | 0.13 | 0.03 | *** | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Italy, Naples | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.03 | *** | 0.09 | 0.03 | *** | 0.11 | 0.03 | *** | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Italy, Rome | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.02 | *** | 0.08 | 0.02 | *** | 0.11 | 0.03 | *** | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Kenya | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.03 | *** | 0.09 | 0.03 | *** | 0.09 | 0.02 | *** | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Philippines | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.03 | *** | 0.11 | 0.03 | *** | 0.15 | 0.04 | *** | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Thailand | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.03 | *** | 0.10 | 0.03 | *** | 0.12 | 0.03 | *** | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Sweden | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.02 | *** | 0.06 | 0.02 | *** | 0.07 | 0.02 | *** | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Colombia | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.03 | *** | 0.10 | 0.03 | *** | 0.12 | 0.03 | *** | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Jordan | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.03 | *** | 0.10 | 0.03 | *** | 0.17 | 0.04 | *** | 0.02 | 0.05 |

Note:

p < .001. USEA = US European American sample. USAA = US African American sample. USLA = US Latin American sample. Coefficients are standardized.

Parameter was constrained to equality across cultural groups without significantly worsening model fit; slight variation in parameter estimates across cultural groups arises in the context of standardized coefficients.

With regard to child effects, in each cultural group, child externalizing behavior at ages 8, 9, and 10 was significantly positively associated with subsequent parental control at ages 9, 10, and 12, respectively (Table 6). These results indicate that high child externalizing behavior at each of these ages predicts higher parental control at the next age. In terms of parenting effects, no significant effects of parental control on subsequent child externalizing behavior were found.

Parental Control – Child Internalizing Behavior Model

The final model (Table 7) fit the data significantly better than the initial model that was constrained to be equal across groups (χ2[495] = 851.69, p < .01). This model fit the data well (χ2 [352] = 448.34, p < .01, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.07). In the final model, all paths were freed to vary across cultural groups except for the eight cross-lagged paths. Freeing these cross-lagged paths to vary across groups did not significantly improve model fit. Notable results with regard to cross-lagged paths depicting child effects on subsequent parenting and parenting effects on subsequent child behavior are considered below.

Turning to the child effects, in each cultural group, child internalizing behavior at ages 8, 9, and 10 was significantly positively associated with subsequent parental control at ages 9, 10, and 12, respectively (Table 7). These results indicate that high child internalizing behavior at each of these waves predicts higher parental control at the next wave. With respect to parenting effects, in each cultural group, parental control at age 9 was significantly positively associated with child internalizing behavior at age 10. No other significant effects of parental control on subsequent child internalizing behavior were found.

Sensitivity Analyses By Parent Gender

Aligning with major parenting theories that stress the importance of situating parenting within broader family and cultural contexts (e.g., Bornstein, 2012), and which emphasize the transactional and reciprocal models of parenting that are applied across both mother and father parenting behaviors (e.g., Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992), the current study focused on the investigation of family-wide perceptions of parenting (i.e., combining mother, father, and child reports of parenting). However, as a sensitivity analysis, we investigated whether study results substantively changed if we ran separate models that included only mother- or father-reported warmth, control, child externalizing, and child internalizing behaviors. Therefore, we re-ran the final four study models outlined above separately for fathers and mothers. Two notable differences emerged in these sensitivity analyses. First, in the Parent Control-Child Internalizing model for fathers, no significant effects emerged. This result stands in contrast to results in the combined model, where child internalizing behavior at ages 8, 9, and 10 was significantly positively associated with subsequent parental control at ages 9, 10, and 12, respectively (Table 7). Second, in the Parent Control-Child Externalizing model, mother (β = 0.49, p = .03) and father (β = 0.49, p = .055) control at age 9 significantly predicted child externalizing behavior at age 10, whereas in the combined model parent control at age 9 predicted child externalizing behavior at age 10 at a marginally significant level (β = 0.43, p = .09). Other paths in these models, and the six other mother- and father-specific models, revealed no substantive differences in model results. Due to the relatively small number of differences seen, and the fact that examination of mother- and father-specific parenting differences is beyond the scope of the current manuscript, we do not report on these models further.

Discussion

Across cultural groups, our findings suggest that from ages 8 to 13, children had a large effect on subsequent parenting: more child externalizing and internalizing behavior problems at a given age generally predict less parental warmth and more parental control at the next age, controlling for stability in parenting and child behavior over time and contemporaneous correlations between parenting and child behavior. There was less evidence that parenting affected child behavior; parental warmth and control at a given age did not consistently predict child externalizing and internalizing behavior at the next age, but some effects were found in mid to late childhood rather than early adolescence. Parents appear to react to high child externalizing or internalizing behavior by decreasing subsequent warmth and increasing subsequent control. Child-driven effects on parents’ behavior appear to occur across the entirety of the transition from late childhood (i.e., ages 8-9) to early adolescence (i.e., ages 10-13). Together these findings suggest that parenting theories that hinge on parental warmth and control have broad applicability across cultural groups and that child-effects play an important role, as we found more evidence for similarities than differences across groups in the ways that parental warmth and control are related to child externalizing and internalizing behaviors.

Evidence-based interventions for both externalizing and internalizing behavior emphasize the ongoing importance of parent-demonstrated warmth in the face of behavior problems (e.g., Connell et al., 2008). Practitioners and parent training interventions sometimes include parental warmth and control as targets of change. Earlier intervention is generally more effective than later intervention (Brooks-Gunn, 2003; National Center for Parent, Family, and Community Engagement, 2015), so parent training interventions that target parents of children may be more effective than interventions that target parents of adolescents. During adolescence, involving adolescents themselves, and parent-adolescent dyads, in the intervention, is likely especially important if the goal is to effect change in adolescents’ behavior. In addition, our findings suggest that interventions should include components that address issues of parental reactivity and that help parents learn strategies for responding to adolescents’ externalizing and internalizing behaviors without decreasing warmth or increasing control.

It appears that there are fewer parent-driven effects (i.e., effects of warmth and control) on child externalizing and internalizing problems. Yet, those effects that do exist appear to be developmentally specific and consistent across cultures. Parental warmth when children are around age 9 is consistently negatively associated with subsequent child externalizing and internalizing problems at age 10. Higher parental warmth predicts lower externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Similarly, parental control when children are around age 9 is consistently positively associated with subsequent child externalizing behavior at age 10. The only other significant parent-driven effect emerged with regard to parental warmth when children were around age 8 being negatively associated with child externalizing behavior at age 9. Therefore, it may be that parenting during the transition from late childhood to early adolescence is especially influential in shaping subsequent adolescent behavior problems, but once children reach adolescence, other factors (such as peers, identity formation, and school environment) became more effective shapers of child behavior (e.g., Albert, Chein, & Steinberg, 2013; Marin & Brown, 2008; Van Ryzin, Fosco, & Dishion, 2012). Across cultural groups, parenting effects fade as children’s ability to make social comparisons (i.e., compare themselves to their peers) improve (around ages 8-10; see Siegler & Alibali, 2004). The shift from parent to peer influence on child behavior may be most pronounced across this transition (see Bornstein, Jager, & Steinberg, 2012).

It is also possible that measures that capture parental warmth and control well during childhood do so less well during adolescence as demonstrations of warmth and appropriate forms of control change. In addition, parenting dimensions other than warmth and control might become more relevant as children progress into adolescence. For example, parents may increasingly take on advisory roles about issues external to the family such as what classes to take in school or possible career paths, and part of parents’ important function may be to facilitate adolescents’ peer relationships and extracurricular interests by hosting adolescent gatherings or providing transportation.

Parents often find it more difficult and less rewarding to parent adolescents than children (e.g., Nomaguchi, 2012; Pickhardt, 2013). One reason that the process of parenting adolescents is perceived as being more challenging than the process of parenting children may involve the developmental shift from parent effects on children to child effects on parents that characterizes the transition to adolescence. If parents are less able to influence their adolescents than they were their children, this could make the process of being a parent of an adolescent frustrating and stressful and may account at least in part for the increase in mental health problems and decrease in life satisfaction that parents experience as their children enter adolescence (Steinberg, 2001).

Parent-driven effects on child behavior problems appear to be largely consistent across cultures. It may be that, just as corporal punishment and harsh discipline increase child externalizing and internalizing behavior cross-culturally (Lansford, Sharma et al., 2014), both parental warmth and control are broadly generalizable mechanisms for influencing behavior in late childhood. It is especially notable that all of these effects persist after controlling for inter-time correlations among contemporaneous parental warmth and control and child externalizing and internalizing behavior and persist after accounting for parental education and child gender. It is perhaps most impressive that these effects persist even after accounting for autoregressive parameters (i.e., parenting predicts subsequent child behavior problems, and vice versa, even after accounting for prior child behavior problems and parenting). These results align with extant developmental research that suggests that, as children age, child effects on parenting behavior increase relative to parenting effects on child behavior (Hawkins et al., 2007; Stice & Barrera, 1995; Vuchinich, Bank, & Patterson, 1992). We note, however, that correlations between parents’ warmth and control and children’s externalizing and internalizing problems may also be driven by genetic factors. For example, low parental warmth and high child internalizing problems may both result from a genetic predisposition toward depressive symptoms. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with child effects demonstrated in an experimental setting: When conduct-disordered boys were paired with mothers of other conduct-disordered boys and (separately) with mothers of non-conduct-disordered boys, conduct-disordered boys elicited negative parenting from both sets of mothers (Anderson, Lytton, & Romney 1986). Although our results replicate prior findings, they also notably expand them by capturing the phenomena across an unprecedented range of cultures.

Taken together, the findings suggest that parenting theories that emphasize the role of parents in influencing adolescents’ behavior and empirical findings that do not take into account child effects are missing important pieces of the developmental story. Bidirectional and transactional effects have long been incorporated in conceptual models of how parents influence children and children influence parents over time (e.g., Patterson et al., 1992; Sameroff, 1975), and empirical tests increasingly incorporate bidirectional relations (see Pettit & Arsiwalla, 2008, for a discussion of themes on this topic in a special section of Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology). The child effects that were found in the present study across the transition from childhood to adolescence and across 12 cultural groups in nine countries suggest the importance of a central role for child effects in future parenting theories and empirical research.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

These analyses examined parental warmth, parental control, and youth behavior problems in the context of late childhood and early adolescence. An important direction for future research will be to extend the analyses into later stages of adolescence. Although parental warmth appears to be an important feature of parent-child relationships throughout adolescence and into adulthood (e.g., Ramsey & Gentzler, 2015), the role of parental control in other studies appears to change developmentally and in ways that are dependent upon the broader cultural context. For example, parents are more controlling in China than in the United States (Ng, Pomerantz, & Deng, 2014). During early adolescence, American adolescents gain more autonomy in making decisions than Chinese adolescents, and decision-making autonomy is more strongly related to emotional well-being in the United States than in China (Qin, Pomerantz, & Wang, 2009). Similarly, in the Philippines even adult children continue to rely on their parents for guidance in a pattern better characterized as being interdependent than independent (Alampay, 2014). Thus, future research that tracks parental warmth and control in relation to externalizing and internalizing problems into later adolescence in different countries will be important for understanding the full extent of how these constructs, which are central to parenting theories, apply to adolescents in diverse cultures. In addition, as parents help their adolescents navigate an increasingly diverse world, it will be important to understand how immigrant families handle challenges that might stem from differences in the expected developmental trajectories of parental warmth and control in a country of origin compared to expectations in the country of destination, as discrepancies between the two may be particularly challenging for both parents and adolescents (Bornstein, 2017).

A strength of this study was the inclusion of data reported by mothers, fathers, and their children. The models were constructed using composite variables that took into account all of these perspectives; however, we did not explicitly attend to whether different reporters regarded parental warmth and control similarly. Indeed, robustness and sensitivity analyses in the present study did reveal minor differences in associations between parenting and child psychopathology in models that solely captured maternal and paternal reports of these constructs, compared to the combined reporter models used in the current study. However, it is important to note that the differences we did find resulted from models that included only single reporters (i.e., mothers or fathers) reporting on both parenting and child behavior, and that the majority of our mother- and father-specific models revealed few substantive differences in results when compared to our combined model. Therefore, we concluded that these mother- and father-specific differences, though notable enough to warrant future investigation of gender-specific cross-cultural differences in parenting, ultimately did not threaten the major substantive inferences drawn in the current study (i.e., that child behavior symptoms had a large effect on subsequent parenting behavior across the transition from late childhood to early adolescence, and that parent effects on subsequent child behavior emerged in late childhood). Additionally, extant research has found that in some families, parents and youth may have substantial agreement on parents’ warmth and control, whereas in other families, individual family members may not share these perceptions (Jager, Yuen, Bornstein, Putnick, & Hendricks, 2014). A direction for future research will be to further examine distinctions among, mother, father, and youth perceptions, as well as how well these perceptions align with observed parental warmth and control.

Finally, we caution that, although the full sample was more diverse than is typical in studies of parenting and adolescent adjustment, the national/cultural subsamples were not fully representative of the cultures or nations from which they derived. In addition to diversity in national origin, families also are diverse with respect to socioeconomic status and structure, which also affect relations between parenting and adolescents’ development (Jones et al., this issue; Murry & Lippold, this issue; Pearce, Hayward, Chassin, & Curran, this issue). Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to reflect country-wide effects and should not be overgeneralized to cultural groups that were not included in the study. Further investigation of within-country differences based on socioeconomic status and family structure is warranted. However, the robustness of the findings across the nine countries (and 12 cultural groups) that were included lends confidence in the replicability of the findings.

Conclusions

Taken together, the findings suggest three main conclusions. First, parenting theories that emphasize parental warmth and control are relevant across cultural groups. We found more evidence of similarities than differences across groups in how parental warmth and control were related to child externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Second, child effects rather than parent effects may better characterize how parental warmth and control are related to child externalizing and internalizing behaviors over the transition from preadolescence to adolescence. Child effects were found to be developmentally consistent across the age range of 8 to 13 years. Third, parent effects may be more characteristic of how parental warmth and control are related to externalizing and internalizing during childhood than early adolescence. Across cultures, as children transition to adolescence they appear to begin exerting greater influence over their parents’ behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This research has been funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant RO1-HD054805; predoctoral fellowships provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32-HD07376) through the Center for Developmental Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; and Fogarty International Center grant RO3-TW008141. This research also was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH/NICHD and the ERC (695300-HKADeC-ERC-2015-AdG). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NICHD. Preparation of the manuscript was supported by the Society for Research on Adolescence.

Contributor Information

Jennifer E. Lansford, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

W. Andrew Rothenberg, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Todd M. Jensen, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Melissa A. Lippold, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Dario Bacchini, University of Naples “Federico II,” Naples, Italy.

Marc H. Bornstein, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD, USA, and Institute for Fiscal Studies, UK

Lei Chang, University of Macau, China.

Kirby Deater-Deckard, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA.

Laura Di Giunta, Università di Roma “La Sapienza,” Rome, Italy.

Kenneth A. Dodge, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

Patrick S. Malone, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

Paul Oburu, Maseno University, Maseno, Kenya.

Concetta Pastorelli, Università di Roma “La Sapienza,” Rome, Italy.

Ann T. Skinner, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

Emma Sorbring, University West, Trollhättan, Sweden.

Laurence Steinberg, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA and King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Sombat Tapanya, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Liliana Maria Uribe Tirado, Universidad San Buenaventura, Medellín, Colombia.

Liane Peña Alampay, Ateneo de Manila University, Quezon City, Philippines.

Suha M. Al-Hassan, Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan, and Emirates College for Advanced Education, Abu Dhabi, UAE

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL 14-18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Multicultural understanding of child and adolescent psychopathology: Implications for mental health assessment. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alampay LP. Parenting in the Philippines. In: Selin H, editor. Parenting across cultures: Childrearing, motherhood and fatherhood in non-Western cultures. The Netherlands: Springer; 2014. pp. 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Albert D, Chein J, Steinberg L. Peer influences on adolescent decision making. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22:114–120. doi: 10.1177/0963721412471347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht AK, Galambos NL, Jansson SM. Adolescents’ internalizing and aggressive behaviors and perceptions of parents’ psychological control: A panel study examining direction of effects. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:673–684. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9191-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KE, Lytton H, Romney DM. Mothers’ interactions with normal and conduct-disordered boys: Who affects whom? Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:604–609. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin AL. Behavior and development in childhood. New York, NY: Dryden; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Stolz HE, Olsen JA. Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2005;70(4):1–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2005.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Xia M, Olsen JA, McNeely CA, Bose K. Feeling disrespected by parents: Refining the measurement and understanding of psychological control. Journal of Adolescence. 2012;35:273–287. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs. 1967;75:43–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monographs. 1971;4:1–102. doi: 10.1037/h0030372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker W. Consequences of different kinds of parental discipline. In: Hoffman M, Hoffman L, editors. Review of child development research. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1964. pp. 169–208. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Cultural approaches to parenting. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2012;12:212–221. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2012.683359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Children’s parents. In: Bornstein MH, Leventhal T, editors. Ecological settings and processes in developmental systems Vol. 4 of the Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. 7th. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2015. pp. 55–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. The specificity principle in acculturation science. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2017;12:3–45. doi: 10.1177/1745691616655997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Jager J, Steinberg LD. I. Weiner (Ed.), Handbook of psychology (2nd ed.), R. M. Lerner, M. A. Easterbrooks, & J. Mistry (Eds.), Volume 6. Developmental psychology. New York, NY: Wiley; 2012. Adolescents, parents, friends/peers: A relationships model (with commentary and illustrations) pp. 393–433. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J. Do you believe in magic?: What we can expect from early childhood intervention programs. Society for Research in Child Development Social Policy Report. 2003;17(1):3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Connell A, Bullock BM, Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Wilson M, Gardner F. Family intervention effects on co-occurring early childhood behavioral and emotional problems: A latent transition analysis approach. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:1211–1225. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9244-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:487–496. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Lansford JE, Malone PS, Alampay LP, Sorbring E, Bacchini D, Al-Hassan SM. The association between parental warmth and control in thirteen cultural groups. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:790–794. doi: 10.1037/a0025120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittus PJ, Michael SL, Becasen JS, Gloppen KM, McCarthy K, Guilamo-Ramos V. Parental monitoring and its associations with adolescent sexual risk behavior: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e1587–e1599. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guildford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Erkut S. Developing multiple language versions of instruments for intercultural research. Child Development Perspectives. 2010;4:19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness S, Super CM. Culture and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting Vol. 2. The biology and ecology of parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 253–280. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins DN, Amato PR, King V. Nonresident father involvement and adolescent well-being: Father effects or child effects? American Sociological Review. 2007;72:990–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Bromell L, Tyson F, Flint R. Developmental commentary: Ecological perspectives on parental influences during adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:367–377. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve M, Dubas JS, Eichelsheim VI, van der Laan PH, Smeenk W, Gerris JR. The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:749–775. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager J, Yuen CX, Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Hendricks C. The relations of family members’ unique and shared perspectives of family dysfunction to dyad adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28:407–414. doi: 10.1037/a0036809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LE, Greenberg MT. Parenting and early adolescent internalizing: The importance of teasing apart anxiety and depressive symptoms. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2013;33:201–226. doi: 10.1177/0272431611435261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata Y, Alink LRA, Tseng WL, van IJzendoorn MH, Crick NR. Maternal and paternal parenting styles associated with relational aggression in children and adolescents: A conceptual analysis and meta-analytic review. Developmental Review. 2011;31:240–278. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2011.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khaleque A, Rohner RP. Perceived parental acceptance-rejection and psychological adjustment: A meta-analysis of cross-cultural and intracultural studies. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002;64:54–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00054.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klevens J, Hall J. The importance of parental warmth, support, and control in preventing adolescent misbehavior. Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior. 2014;2:121. doi: 10.4172/2375-4494.1000121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practices of structural equation modeling. 3rd. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Laird RD, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Mothers’ and fathers’ autonomy-relevant parenting: Longitudinal links with adolescents’ externalizing and internalizing behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:1877–1889. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0079-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Sharma C, Malone PS, Woodlief D, Dodge KA, Oburu P, Di Giunta L. Corporal punishment, maternal warmth, and child adjustment: A longitudinal study in eight countries. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43:670–685. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.893518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie JY, Oh BJ, Lau AS. Cultural differences in the links between parental control and children’s emotional expressivity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2013;19:424–434. doi: 10.1037/a0032820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]