Summary

Obesity is a complex, chronic disease, frequently associated with multiple comorbidities. Its management is hampered by a lack of translation of evidence on chronicity and pathophysiology into clinical practice. Also, it is not well understood how to support effective provider–patient communication that adequately addresses patients’ personal root causes and barriers and helps them feel capable to take action for their health. This study examined interpersonal processes during clinical consultations, their impacts, and outcomes with the aim to develop an approach to personalized obesity assessment and care planning. We used a qualitative, explorative design with 20 participants with obesity, sampling for maximum variation, to examine video‐recorded consultations, patient interviews at three time points, provider interviews and patient journals. Analysis was grounded in a dialogic interactional perspective and found eight key processes that supported patients in making changes to improve health: compassion and listening; making sense of root causes and contextual factors in the patient's story; recognizing strengths; reframing misconceptions about obesity; focusing on whole‐person health; action planning; fostering reflection and experimenting. Patient outcomes include activation, improved physical and psychological health. The proposed approach fosters emphatic care relationships and sensible care plans that support patients in making manageable changes to improve health.

Keywords: obesity management, patient‐centred care, primary health care, qualitative research

What is already known about this subject

Primary care providers are hesitant to discuss obesity with patients; when they do clinical management inconsistently aligns with evidence of the complexity and chronicity of obesity.

Patients want care that addresses their personal set of root causes, drivers, and barriers.

Communication between patients and primary care providers can impact health, but how is not well understood.

What this study adds

Key processes of a personalized approach to obesity include: compassion and listening; making sense of root causes and contextual factors in the patient's story; recognizing strengths; reframing misconceptions about obesity; focusing on whole‐person health; action planning; fostering reflection and experimenting.

Cognitive and emotional shifts resulting from the consultation foster patient activation, supported manageable changes, improved function, and benefits for perceived mental, physical and social health.

Introduction

People living with obesity want and need care that is tailored to their specific context in order to make changes to improve health 1, 2, 3. Yet, clinical management of obesity is hampered by a lack of translation of evidence into practice and public discourse 4, 5. This results in misinformation about its complexity, harmful practices and unrealistic weight‐loss expectations by healthcare providers and patients 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. Obesity has been linked with a broad spectrum of root causes. In the development of obesity, biological factors including genetics, epigenetics and neurohormonal mechanisms interact with social determinants of health, socio‐cultural practices and beliefs, built environment and public policy, individual biography, and psychological factors such as mood, anxiety, self‐worth and identity 1, 10, 11, 12, 13. All these factors must be considered in effective clinical management. Over the course of the lifecycle, weight fluctuations, metabolic diseases, medical conditions with pain or mechanical impairment and medications may contribute to weight gain.

Primary care providers play an important role in caring for patients with complex, long‐term conditions like obesity 14. However, in contrast to other conditions like depression or cardiometabolic disease, there is little training for physicians on how to assess and manage obesity as a multifactorial disease. Scant attention has been paid to primary care physician–patient interaction and dialogue in this area. Communication studies with focus on interaction and dialogue are scarce. A comprehensive review found that most research examined clinician communication styles, rather than patient communication or dialogue 15. Many studies rely on participant reported perceptions of communication rather than direct observation. The authors identified a gap in research on the complex interactions in communication about obesity. This is paralleled by insufficient understanding of how interventions aimed at patient's impact outcomes over time 16, 17.

Fundamentally, there is a lack of understanding of what happens at an interpersonal level in a primary care consultation about obesity that has impact on patient‐important outcomes. To capture this, we conducted in‐depth qualitative research using direct observation of consultations to study provider–patient dialogue about obesity and its effects on patients’ everyday life efforts to improve health. We paid attention to the interpersonal dynamics during consultations to give a more comprehensive and accurate sense of how people arrive at and work to integrate new understandings of health in the context of their life. We partnered with frontline clinicians and patients to ensure the approach is pragmatic in interdisciplinary primary care teams and meets the needs of people with lived experience. We expanded on the theoretical implications for shared decision‐making in chronic disease elsewhere. Our aim here is to elucidate (i) Key processes of personalized obesity assessment and care planning and (ii) A better understanding of the impacts that link the consultation to change and outcomes in patients’ daily life.

Materials and methods

The 5As Team research program

This study is part of the 5As Team (5AsT) research program which partners with a primary care organization (Primary Care Network, PCN), healthcare providers, and patients to transform obesity prevention and management 18, 19, 20, 21. It builds on our previous research showing that providers want to improve care for patients with obesity, and that patients want personalized, evidence‐based discussions with their family doctors and teams 3, 22.

Approach to the conversation about obesity

We used a strategy of emergent design flexibility 23 to study and develop the 5AsT approach. Initially, the consultation was guided by the 5As of Obesity Management 24, 5As Team tools 25, Kushner's obesity‐focused life history 26, literature on aetiology and management 11, 26, 27, patient perceptions 3, 10, 28 and provider–patient communication 15, 29. Core principles of the 5AsT approach include obesity as a multifaceted, chronic disease and a focus on improving health rather than weight loss 11, 21, 30, 31. Goals aim at improving function (functional goals) and regaining the ability to do things that are of value and enhance quality of life (value goals) 32. To reduce variability in how providers delivered the 5AsT approach, two experienced PCN clinicians (family physician, dietician) volunteered to conduct the consultations. The approach was refined informed by iterative analysis of patient experience and team discussion.

Methodology

To capture interpersonal processes and their meanings for peoples’ efforts to improve health we used a qualitative, inductive approach. As an explorative study, no predefined outcomes measures were applied; instead, results inform theoretical frameworks and outcome measures for intervention development and testing. Design, data collection and analysis were shaped by both pragmatic clinical considerations and analytical attention to dialogic interaction 33. PCN clinicians, managers, and patient advisors provided input on research question, methods, interpretation and validated results.

Prior to team discussions, we held a workshop on reflexivity to examine the impact of our biography, socio‐cultural position and profession on the research process 34.

Participants

We recruited participants by phone from an existing cohort of adults with overweight and obesity who have engaged with the PCN for weight concerns. To understand how the approach can be tailored to diverse patients, we purposefully selected people to maximize variation in context and comorbidity (Table 1). We invited 28 people, 20 consented to participate. This research was approved by the ethics board of the University of Alberta Pro00062455_REN2 and participants provided written informed consent.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Age | Range: 32–75 |

| Gender | Female: 14 |

| Male: 6 | |

| Self‐reported ethnicity | 14 Caucasian |

| 1 Hispanic | |

| 1 Aboriginal | |

| 3 South Asian | |

| 1 other | |

| Marital status | Married: 10 |

| Widowed and separated: 7 | |

| Single: 3 | |

| Education | Post‐secondary: 13 |

| High school: 5 | |

| Other: 2 | |

| Household income | >80 000: 5 |

| 50 000–79 000: 4 | |

| 15 000–49 000: 4 | |

| <15 000: 1 | |

| No data: 6 | |

| Comorbidities* | 4 or more: 7 |

| 2 or 3: 9 | |

| None: 3 | |

| No data: 1 |

Examples: depression, anxiety, asthma, arthritis, chronic back pain, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, migraine, liver disease, Aspergers, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome.

Data collection

Twenty one‐on‐one clinical consultations were video‐recorded. TL conducted semi‐structured interviews after the consultation with the patient, then the provider. Patients were asked to journal using notebooks, computer or audio‐recorders, about their everyday experiences and outcomes until the end of the study. Patients were interviewed (TL) again at 2 and 4–8 weeks. All interviews were audio‐recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Data were managed and coded in NVIVO 11. Following quality principles for qualitative research 35, familiarization with data was followed by reduction into codes relevant for the research questions. To enhance trustworthiness three researchers (TL, DCS and research assistant) cross‐coded data sets of five participants using open coding. Instances in the data, code definitions and labels were discussed in weekly meeting to develop a code manual. One author (TL) then coded all data refining codes if needed after discussion with the team. Coded data were explored within and across participants to identify themes and disconfirming information. Analytical attention was guided by dialogic interactionism to understand how dialogue shapes peoples’ experience of obesity, views of self and health, and how people act in relation to what they communicate 33. Emergent themes were discussed in the team, critically reflecting on positionality and bias 34, and validated with providers and patient advisors.

Results

We recorded 20 consultations, 59 patient interviews (one second follow‐up missing) and 20 provider interviews. We collected 17 complete journals, two until the first follow‐up and one that shared results from a tracking application.

For this article we grouped themes into three types of results: key processes, impacts and outcomes. Key processes were identified when patients experienced interpersonal processes during the consultation as having positive impact on their ability to make everyday changes. Impacts are immediate cognitive, emotional or motivational effects of the conversation on the patient. In contrast, outcomes denote tangible changes in patients’ life and in perceived emotional, physical and social health resulting from the consultation.

Eight key processes emerged and are presented together with their impacts; outcomes follow in a separated section. Representative quotes (Tables 2, 3, 4) have been edited minimally for readability.

Table 2.

Representative quotes for key interpersonal processes during the consultation

| Theme | Example quotes (de‐identified participant number, data time point) |

|---|---|

| 1. Engendering compassion and ‘real’ listening | |

| Compassion | You, you know I would say the, that what had the most impact on me was, was the session itself and the approach she took because I'm now taking that approach in my, with myself so she showed me an approach that was about compassion, about being gentle with myself, about understanding that there's lots of different variables that are affecting things and about giving, not being afraid to and actually trying to ensure that on a daily basis I'm congratulating myself for you know seeing my strengths, looking at the positive things that I'm contributing to what I'm doing right now so it feels, I'd have to say overall that it just feels like a much gentler process. (240, follow‐up 1) |

| Real listening | Cause she was also as I mentioned doing a good job of not putting words in my mouth but just really trying to make sure that she was paraphrasing and she was always putting it back on me to make sure that I was okay with how she described it and then from there it's like well here's some resources and that kind of custom, that's real listening right. That's real, real listening and you don't get that in many places so that's a positive experience and with that came kind of not just a package but a custom, customized package so that's just a very positive experience ‘cause we just, there's such a shortage of that in the health care system so. (5 follow‐up 1) |

| 2. Making sense of the story | |

| Root cause assessment | I think what made the difference for me was when I met with the doctor like going back in time and talking about how things were then present and not just physical health but other things going on so kind of looking back and being like oh yea I used to do these things and this kind of happen, this and this and this and then just being reminded and working through that like that was a really big help because a lot of the times people don't like health practitioners don't go back that far, they're just kind of like in the present you know so you know actually sitting down and taking to do back from my past and now was a big help because it was like I used to do all that, I used to do this you know. (128 follow‐up 2) |

| Fostering insight | My overall impression was it was, it was very insightful especially the part about doing the history like the timeline was super helpful for me. It was (upset)…it's very, it was very emotional to do that part obviously. But very insightful at the same time because, because I have a clear pattern of doing okay with my weight and then having problems with my weight so…but it makes me, it just, I didn't, revisited all those things that were happening at that time so no I also found it really helpful. (255 post‐consultation) |

| 3. Recognizing strengths | |

| But when someone turnaround and tells you that that's a strength and that this is you know that you're getting through life no matter what's being throw at you and it's actually looking pretty good at this point and you know it's feeling good but to have someone say that back to you is, is huge. It, you know it's because it's one thing for us to see who we are and to know who we are. It's something completely different for another person to acknowledge that to us. That's huge. Huge. (240 post‐consultation) | |

| 4. Shifting beliefs about obesity: managing expectations and focusing on whole‐person health | |

| Managing expectations | Oh. You know what I think it was the part that we talked about this best weight…and because I don't feel as much pressure to lose the hun, like a hundred pounds ‘cause it's huge so it brings my goal more into a reasonable range so I, I feel like I'm more likely to, to be able to have some weight loss and, and have a lower best weight than I'm currently at and it's, so it's, it seems like it's more in, attainable. (108 follow‐up 1) |

| Focusing on whole‐person health | It felt like from like her perspective it was such a focus on being healthy and thinking healthy and like making healthy choices and really like drawing the distinction between like being so focused on weight loss versus being focused on your health. It was, it was like such a good shift. It was so good. (130 post‐consultation) |

| 5. Co‐constructing a new story: context integration and prioritizing | |

| Context integration | When she, when she did her kind of integrated summary, that was really emotional again because she, she kind of got it and I think it was at that point…I'm not sure was as emotional reliving the stuff as it was kind of having someone look at my life that way and kind of go like she got it. (@) Because I've looked at my life that way but to have someone else kind of affirm that…is sort of no wonder you have problems and you were dealing with all of this and you're really resilient and, and so that was, I mean that was nice to hear the strengths too. (255 post‐consultation) |

| Prioritizing | And coming to terms with the fact that how you feel, your moods and, and the way you deal with your emotional situations and the stress in your life and how these things impact everything else that, that you do and how they impact your health and your habits and, and your choices, I realize that I had a tendency to kind of push that aside and it doesn't work because it has, it has to be resolved or nothing fixes itself and it just doesn't work so that's the main thing and that I'm going to have start doing some things in order to try and address that. (6 post‐consultation) |

| 6. Orienting on value goals and planning actions | |

| Direction | […] the eating healthy here, those choices, that was probably motivated mostly by this project so being part of a plan and a program that had a very clear sort of direction and goals and steps to do what whatever was probably was the most influencing factor on that. (208, follow‐up 2) |

| Orientation on functional and value goals | Yeah, yeah there is and it's these, it's these two goals here that she talked to me about. When she wrote this down at the end, she said to improve your balance, your strength, your flexibility, to maintain your function so I can play with my grandkids and to improve my girth to so I could get on an airplane and just go click on my seatbelt, to go to a store to buy a bathing suit and actually try on okay this is this size, I think I can fit that one. Let me try it on, oh my gosh it actually fits. Yes that's, that, these, this is what stuck in my mind the most is right at the end of our conversation and that's what I keep going back to. (198 follow‐up 2) |

| 7. Fostering reflection | |

| Insight |

I: Yeah. How did you generally find that experience of journaling?

255:Oh I love it. I, I got so many ah‐has out of journaling. I'm just, I, I write down what I did and then I go why do I do this? I need to think more about why I do this, you know what was happening here? Why do I still need a cup of Smarties at night? You know why when I know that I shouldn't do it or then why do I have should and shouldn't about eating like every, everything. I also kind of summarized reviewed kind of stuff that I've done that were sort of beyond the appointment but what, the appointments spurred me on to kind of do. (255 follow‐up 2) |

| Motivation | Actually with that awareness too it also kinda helped me to kinda be more physical, more active with that as well yea, I started Wednesday I think last week, I started walking every night, I walk 30 min a day so I've been sticking to it, it doesn't matter what time you know and it's something that, it's not like ugh I have to go walk now you know, it's like something I just automatically do like it's something I look forward to now because it's to me when I write about it afterwards it kinda reinforces like how good I feel like how positive I feel about it because yea so it kinda helps to oh this is why I wanna walk right so but yea it was, I would say awareness, mostly awareness and just focusing more on what I was going like the negative versus the positive and kind of acting on it so. (128 follow‐up 1) |

| Accountability | Goals wise, I did not eat out lunch and I had a delicious healthy salad as an afternoon snack! Which is not my usual snack fare…not one of my goals, but I felt good making a healthier choice. BUT I wonder if I would have made the same choice if I didn't have to come and write in this journal. The journal is a layer of accountability that is affecting my choices. I hope I'll be able to keep writing in it…and I'd like to be able to think of a way to carry on this accountability after the study is over. (130 journal) |

| Internalizing core messages | Maybe that's it ‘cause I, I've noticed that reading my notes that I'm not working on myself as much as I should be. I'm more concentrating on other people's, other people. That's what I've been doing so it's kind of a good wakeup call actually to write a journal like this because then you say okay, I'm writing about this person or that person, I'm feeling this or this but I'm not talking about myself sometimes right so that was a good, a good thing to learn. (198 follow‐up 2) |

| Coping | Especially on the days where I have a bad day, it feels good to write it out if I can't run it out right so that'll be my motto, write it or run it. (235 follow‐up 1) |

| 8. Experimenting and re‐evaluating | |

| Experimenting | That's huge and, and look at all the levels we've come through just in a couple weeks right. I mean now you know mind me, mind you I was already charting before so that was a huge plus to go, to come into this with, you know so I definitely add that to your stuff really because this (tapping table) has been huge. For someone like, this has been so telling. Anyway it's told me a lot, given me a lot of information and when we add this to it was just like you know it's just, it's kind of blown apart like all of a sudden there's multi levels and I'm seeing all sorts of stuff I wasn't seeing before so it's good, it's good. I think, I, I also still though think that it's really important…like I don't necessarily believe this session but you know after doing this for a month, I would be feeling like I want to meet with that doctor again and, and tell her how I'm doing and what I've been doing and for us to kind of redo this whole thing right and, and to do that for about a year right ‘cause then I'd be, then I'd have, have this, I'd be on top of this stuff. I'd really know what I was doing right and that would be (whisper) so helpful, so helpful. That could possibly, I believe that that in truth could lead me back to work and could have led me back to work if it had been happening from the beginning right. (240 follow‐up 1) |

| Long‐term relationship | It made sense at the time talking to her because I felt very confident that I could do this on my own but now, no … I went into it feeling really good and then I was disappointed because I, you know that I didn't take with me (chuckle) the knowledge I know. It seemed as though this night issue became really magnified … There were a few good days in there…But now it's like, I don't feel as confident right now.(159 follow‐up 1) |

| Accountability |

I:Okay how is that helpful?

4:It was just really nice to be able to plan something that I can actually do as opposed to just do this and knowing that but being accountable kind of helps too, I know it's helped in the past saying okay I'll do this and then I'll do it, I'm more likely to do it as opposed to okay I'm gonna do something and I think about it in my head and then I just completely forget about it. (4 post‐consultation) |

… Pause; @ laughter; ( ) transcriptionist comment; […] ellipsis – quotes are slightly edited for readability; I interviewer.

Table 3.

Themes describing impacts of the consultation and example quotes

| Impact theme | Example quotes (de‐identified participant number, data time point) |

|---|---|

| Sense‐making | The biggest awareness I've had over and above that is just all around what I'm eating and how much emotions and my illness are like linked. Yeah. (240 follow‐up 2) |

| Focus on whole‐person health | I've just been taking instead of okay I want to lose this many pounds, end of story, it's today I choose to wake up and I'm going to work out and I'm going to try and eat as healthy as I can and then there's no disappointment right and I'll take whatever comes and I'll try and be as strong as possible right like I just. (235 follow‐up 1) |

| Recognizing strengths | The main takeaway for sure is to try and really like believe that I'm healthy (@) and that like and to really change my ongoing goals about my health like to just totally reframe them and think about them from that point of view ‘cause like I'm already healthy and then these decisions I'm going to be making will like be adding to that versus like feeling like I've started from such a deficit and feeling so overwhelmed that I can't even move forward ‘cause I'm so far behind. […] It's oh so empowering. (@) (130 post‐consultation) |

| Sense of direction for action | So I think this whole meeting with her has helped me with that dimension too so I'm going to learn more about that and again just having some hope that I can you know maybe these clinics will just help me with the pain and nudge my quality of life up and then get into a place where it'll just be probably natural for me just to drop a few pounds because you start knocking off some of these habits and little things that you know. (5 post‐consultation) |

| Hope, self‐compassion, and confidence | My main take home was…that I do have a lot of strengths and I'm very resilient and I got through some hard stuff and…I can, I can use those same strengths to keep myself as healthy as I can even if I am going to be overweight. (255 post‐consultation) |

… Pause; @ laughter; […] ellipsis – quotes are slightly edited for readability.

Table 4.

Themes describing patient outcomes and example quotes

| Outcomes theme | Example quotes (de‐identified participant number, data time point) |

|---|---|

| Positive change | Homemade breakfast and lunch! This is getting easier with more practice! No one is more surprised than me. I find Septembers to be such a difficult transition and this is hands down the most I have ever cooked during this month. (Well since owning the store I guess). (130 journal) |

| Now I kinda feel like I'm doing things with my life, more physical, more out there, last year I wouldn't even tell you even a few months ago I wouldn't even walk to the store just the thought of it ugh it's too far you know I would just drive there but now that you know I tell myself why wouldn't you just walk to the store, you walk 30 min a day you know that's gonna be nothing so now I'm more like I would never think to walk to Walmart at Northgate ‘cause it would probably be a 30 min walk my guess and it'll be like ugh it's so far you know but now when I think about it I'm like heh I walk that all the time you know so it wouldn't be a big deal. (128 journal) | |

| Linking with value goals | And that's why it's exhausting but it was a really good exhausting because I finally went swimming because I love swimming, I love being in the water. (4 follow‐up 2) |

| I've been well. I've been doing really well. I've had a huge focus on my health so kind of every week I've been developing different kind of tracking systems and different kind of journaling and so I journal every day. (255 follow‐up 2) | |

| Sustaining change | Oh we've checked out another gym because the gym we belong to doesn't have any showers and you're not allowed to have a personal trainer, you know they don't help you a lot so our membership stand on September 9 so we're gonna let it go and pay a little bit more and go to this other one. (121 follow‐up 2) |

| I actually did what I said I'd do at the last check‐in and talked to my wife about getting her help with my goals. As predicted, she was very supportive and cool about the whole thing, and agreed to kick me if I slack off on the days I committed to working out. I also told her about my food goals and even though she was careful not to officially commit herself to eating healthy and exercising along with me, she was quick to support that initiative as well. So I've started cutting back on my slurpees, upping my salads and healthy choices, and mapped out an exercise schedule that my wife will help me maintain. (208 journal) | |

| Whole‐person health outcomes | It was so cool and refreshing and towards the last few blocks my feet and legs and lower back started hurting. I felt like stopping and laying down. Even thought about calling and getting picked up ha ha. But I know I wouldn't do neither. I kept walking and told myself I can do this. and I did. It was important I did because my seven‐year‐old daughter was with me and I didn't want her to see me give up. I feel proud of myself and accomplished. I feel stronger not just outside but inside too. (128 journal) |

| Instead of like my perception of everyone is oh my God, she's so chunky, why would she try, like lose some weight before you come here and everyone else was really supportive actually right so it's crazy how you can think of the perception versus the reality right where you build everything into your head and then the reality is like wow, that really wasn't so bad. […] And no one can take that away from me. That's the best part right and if I, the next time that I was stressed out, I, I just was like oh my God I want my treadmill so bad and I was like what? Like does that make any sense and just leave, I need a treadmill. (235 follow‐up 1) | |

| I'm generally speaking I am, my activity level is increasing and that's huge, that's huge. Something I've noticed with that is that…generally speaking I'm better every day like I'm, I'm feeling better every day right so I'm not getting those great big swings where I'm in tons of pain and really fatigued and just can't even function or getting out of bed at all. (240 follow‐up 2) | |

| Well one was to find a physio and I've actually just differed that mostly because Water Works at this point is working and so I'm going to, I think these courses for me are more important right now and because Water Works is working, I will, I will keep going with that. (255 follow‐up 2) | |

| In other mental health news, I dealt with a conflict with my friend in a much healthier way than I normally do. I'm not sure it's related to my new healthful living goals, but I am at least certain that I am not under such mental strain trying to diet and berating myself when I fail that I don't have the mental strength to work on my other personal health goals. Ok that was a double negative? Basically, I feel free and unburdened mentally to tackle different types of healthy choices. (130 journal) |

… Pause; […] ellipsis – quotes are slightly edited for readability.

Key processes and impacts of the approach to the consultation

Engendering compassion and ‘real’ listening

All participants highlighted the importance of being listened to with compassion. People described feeling validated and ‘like a human’ (235 post‐consultation). Many reflected in later interviews on how this experience impacted their ability to cope with frustrations while implementing their plan.

Patients appreciated that providers repeatedly summarized what they understood and validated their interpretations with them. Patients experienced this as ‘real listening’ that resulted in an accurate understanding of their specific circumstances as basis for appropriate care plans.

Making sense of the story

Both patients and providers felt that beginning the conversation with the patient's story of their obesity was extremely important. For many, weight gain was linked to crisis events that put strain on coping resources. Sharing their perspective help people to feel valued and acknowledged. Most importantly, it allowed for collaborative identification of root causes, linkages between life and health, contextual factors and patients’ value goals. One provider began early in the study to draw a timeline of patient's weight throughout their life. This visualization of the intersecting patterns of life events and health emerged as impactful tool and was subsequently adopted as a standard part of the 5AsT approach. Acknowledging the impact of life context on weight in an empathic dialogue helped participants to adopt an attitude of self‐acceptance and increased insight into personal drivers of weight gain. Patients consistently asked to take the timeline home and reflected on the insights gained over time.

Recognizing strengths

Patients attributed great importance to the process of recognizing their own strength. Data bears witness to the powerful impact internalized stigma had on peoples’ view of self and their ability to be healthy. By listening for examples of resiliency in patients’ past and labelling them as strengths, providers fostered a shift in participants’ view of themselves, which improved their confidence in implementing changes. Patients noticed this as an unexpected impact of a conversation about obesity. Many shared that they had expected advice on diet and exercise, behaviours they felt they were failing at. Instead, recognizing strengths opened up a space of potential for identifying strategies that people could succeed at, enjoy and find meaningful for their life.

This strength‐based approach positively impacted participants’ confidence, self‐worth and hope.

Shifting beliefs about obesity: expectations and whole‐person health

Frequently, the conversation uncovered areas in patients’ understanding of obesity that were misaligned with current medical knowledge. In response, providers assessed and explained drivers of weight gain such as medications, sleep apnea, emotional issues and metabolic processes. Providers coached patients in focusing on functional outcomes instead of weight, adopting realistic expectations for weight loss and maintenance, and choosing sustainable goals. A number of participants shared how lowered weight‐loss expectations resulted in both relief but also a sense of grief.

For many, the information enhanced knowledge of obesity and provided explanation for their own experiences with weight gain and loss. Particularly when dealing with multiple comorbidities, patients appreciated exploring functional or value goals as direction and motivation for their efforts. The focus on improving whole‐person health was crucial as, in many cases, diet and exercise behaviour was intimately linked to comorbidities, life events, emotional trauma, workplace stress, finances, relationships or loss of meaningful occupation. In addition, it offered renewed motivation and courage for patients who were discouraged by repeated experiences of weight loss and regain.

Co‐constructing a new story: context integration and prioritizing

Participants experienced what we call context integration as particularly impactful. Providers summarized and integrated all relevant factors from the patient's story and assessment that led to their current health status, highlighting strengths, and offering a perspective on which challenges to address first. Providers validated their interpretation with the patient, asked for clarification, and agreed on a priority. This provided an alternative narrative of the patient's obesity: one that explained and acknowledged underlying root causes, offered an alternative, capable and resilient, patient identity, and set a direction for change that made sense in light of their life context. From the patients’ perspective this offered a tremendous shift in the way they thought about themselves and their ability to improve their health.

Orienting actions on value goals

Context integration and priority setting led into thinking about what actions, strategies and resources may be of interest for the patient. Providers and patients identified a functional or value goal that served as an overarching orientation for action planning. A majority of participants wanted to plan actions, some chose to first reflect on the new understandings gained from the conversation. Possible actions emerged from the conversation and differed widely between patients. They included addressing mental health, pain, sleep, seeking financial and social supports, considering anti‐obesity medication or bariatric surgery. While helping with accountability and motivation, action planning was described as less decisive than the cognitive and emotional work that led to context integration and priorities. However, this perception shifted over time, and many participants later reflected on the benefits of planning specific and achievable actions for outcomes.

Fostering reflection

For many participants, the insights and shifts in beliefs about self and health required time to reflect and integrate. People processed new understandings in different ways and internalized them to different degrees. About half of the patients found journaling about their experiences with trying out new ways of conceiving of themselves and health helpful. Others preferred to reflect in conversations with family, friends or the interviewer.

Some people wrote about what triggered their food choices; others documented how sleep, pain and activity levels intersected with how well they were able to implement strategies on a particular day. A number of patients explained how reading their journal entries helped them realize and acknowledge successes. This insight supported continued motivation and confidence. For some the journal provided accountability and, as a result, motivation to keep trying. Finally, for some participants journaling became a coping strategy in itself that helped to deal with negative emotional experiences.

Experimenting and re‐evaluating

Participants experimented with different actions, arranged appointments with interdisciplinary providers, or tried out community resources. Some changed their action plan and implemented different behaviours inspired through the consultation.

During follow‐up interviews, people reflected on what worked, what did not and what needed adjusting. Participants found that having someone ask how things are going was helpful for accountability and motivation. These conversations also helped them develop solutions for barriers. One woman realized at her first follow‐up why she hesitated making an appointment with a behavioural health consultant to address body image issues. Using this awareness she was able to find a way to feel supported enough to arrange the appointment and ultimately address her challenge. Another participant felt confident and optimistic immediately after the consultation, but during her follow‐up conversations she expressed discouragement about her continued night eating. These examples illustrate the need to embed obesity care planning in a long‐term care relationship in order to respond to emerging barriers, shifting experiences, illness and treatment burden.

Outcomes

Participants experienced outcomes as either resulting from the consultation directly or a combination of consultation, journaling, experimenting and succeeding with new strategies. Data also reflect the challenges impacting peoples’ capacity to change, including comorbidities, mental health, relationship or workplace crisis, family obligations, or the dominant culture of social activities involving rich foods.

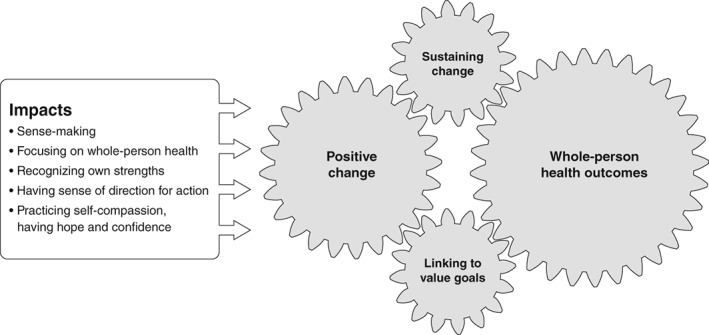

Four themes describe the changes in patients’ everyday life and health resulting from the consultation. These outcomes interact with and impact each other (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Patient reported impacts and outcomes of a personalized consultation. Five direct cognitive and emotional impacts of the consultation facilitated four interrelated areas of change in patients’ everyday life that include positive behaviour change, improvements in physical, mental and social health as well as the adoption of strategies that help maintain change.

Positive change: increased activity

In the weeks after the consultation, people felt activated to improve their health. Many made progress toward or achieved their action goals. They actively sought out and experimented with alternative activities, and some established new habits.

Examples include developing personal journaling and tracking systems, garden work, walking and other physical activities, increasing water intake, meal planning, preparing home cooked meals, mindful eating, joining community or primary care programmes, connecting to support groups, and obtaining referrals and appointments to address underlying health issues.

Linking activities with value goals

The orientation on value goals supported people in linking the change they initiated to purpose, pleasure and meaningful activities. This was particularly important in the face of setbacks or lack of weight results. People found activities that they enjoyed instead of experiencing them as a ‘chore’. For some it was a difficult process to accept that weight maintenance may be their best possible outcome. In these cases, linking activities to benefits other than weight loss was crucial for their continued motivation.

One person was inspired to walk in the evening as a way to improve her endurance. At first, walking in the face of emotional stress appeared absurd:

As I write this I feel sad, […] I'm tired of being told the same things over and over, ‘Oh if you drink more water you will feel full’ – my bladder maybe? All these tips and miracle drinks, ‘Go for a walk’ – it's 11:38 PM right now – should I get out of bed and go for a walk? Just feeling discouraged when it comes to controlling these cravings. (128 journal, May 24, 2016)

While the next day she did walk, she experienced both benefits and hurdles:

It was 10 PM and I thought why not? […] I've been wanting to start walking for a while now. So I went, my daughter and my kids’ dad went with me. Was good, except my right knee is now acting up. Anytime I try and do anything cardio something hurts or goes wrong. (128 journal, May 25, 2016)

Over the next days, she described how pain, weather or family obligations posed significant barriers. However, internalizing some of the messages of the consultation, she paid attention to benefits of walking other than weight loss and adopted a more self‐compassionate attitude. She experienced improved mood, better coping with stress, and new sense of being alive:

So I went and walked for 30 minutes. Sunset was beautiful after the rainfall, made my spirit pick up. I felt happy and invigorated. I felt proud of myself for doing this every night, but mostly, because I want to. Big difference then before. (128, journal May 29, 2016)

Maintaining this habit for a few weeks, she noticed improved strength and started seeking out other opportunities to walk in her everyday life when previously she would have avoided walking.

Sustaining change

Participants employed various strategies to help sustain their new habits. Some adjusted routines, such as choosing a more accessible gym, getting up earlier to journal, or optimizing sleep schedules to increase energy. Another strategy was securing social support to help integrate healthy changes into family and social life. For example, one participant enrolled his spouse to remind him of his workouts. Another motivated their children to join in their daily walks.

Whole‐person health outcomes

Increased internal resources and emotional well‐being

Almost all participants experienced a more positive mood during the study period, felt optimistic about their ability to improve health, had hope and felt inspired. Many explained how the consultation and care plan provided a sense of moving forward with increased confidence. Although these internal resources were enhanced through the consultation, they gained momentum over time through the experience of success in making change. A majority achieved their goals at least partially; some went on to set new goals of their own. These successes allowed people to feel accomplished, competent and encouraged to increase their efforts and take on new goals.

Many described how the consultation had fostered self‐compassion and self‐acceptance, which helped them to remain confident in their efforts. When people experienced setbacks, this attitude of self‐acceptance and compassion helped to regulate emotions and maintain motivation.

Patients emphasized that they had gained valuable insight into their own patterns, triggers, barriers and emotional aspect of behaviour and health. This self‐awareness helped people be mindful of habitual coping strategies and supported finding healthier ways to manage emotions.

However, we found that lowering expectations about weight loss is often accompanied by a sense of grief about potentially never achieving the desired body shape:

No, the effort is not the issue, it's the results there, the issue for me you know so yea, I mean I'm never gonna be happy (@), […] I do know it needs to happen but it's really hard. (126 follow‐up 2)

Physical health

Some participants perceived improvements in pain, function, stamina, strength, energy or sleep. A few felt reduced need for their treatment. For example, one participant felt significant improvements in pain after several weeks of walking and decided to postpone treatment. Another person felt that regular water exercises had improved her pain enough to no longer need physiotherapy.

Although we did not probe for weight results, participants volunteered changes in weight during the study. Five reported weight loss, one maintained their weight, one perceived their clothes fitting better; and one reported weight gain due to ongoing night eating.

Social health

Finally, some participants described benefits in other areas of their lives. Shifting attitudes about self and health affected how they approached social relationships and career planning.

Overall, we observed that the approach to talking about obesity helped people make changes that worked together to establish habits and facilitate sustainability despite the presence of barriers. Most participants felt that follow‐up visits were needed to reflect on progress and plan next steps. Many also described that, despite the shift toward self‐acceptance and realistic goals, they were still experiencing grief about their body shape and weight. These cases point to the importance of scheduling brief follow‐ups where such difficulties can be discussed, supported and unhelpful beliefs reframed.

Discussion

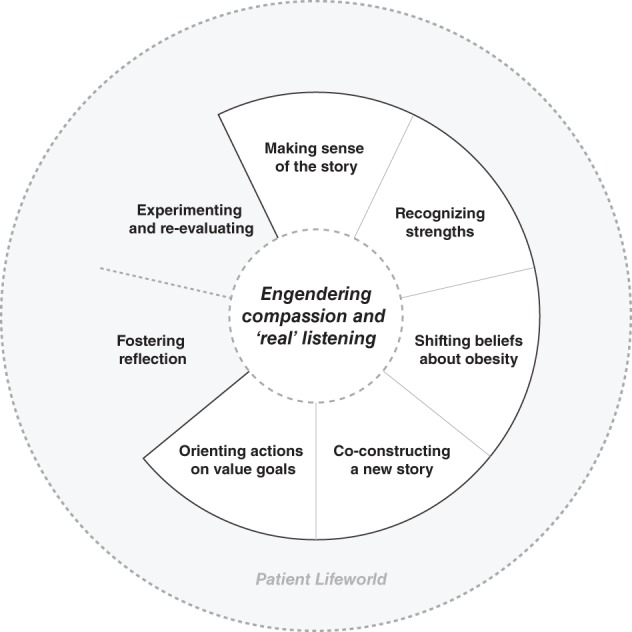

This study used rich empiric data of primary care consultations and their impact in patients’ everyday life to propose an approach to personalized clinical conversations about obesity. We identified and described eight elements that had impact from the patient perspective (Fig. 2). Immediate impacts of the 5AsT approach taken during the consultation can be summarized into five cognitive and emotional shifts (Fig. 1): (i) sense‐making of the linkages between life context, emotions and health; (ii) focus on whole person health rather than weight loss; (iii) recognition of own strengths in overcoming difficulties; (iv) sense of direction for action; and (v) self‐compassion, self‐acceptance, hope and confidence to make changes and improve health. Outcomes were generally positive and covered a range of improvements including activation, establishing healthy sustainable habits, improved function, and benefits for perceived mental, physical and social health.

Figure 2.

Key processes of personalized obesity assessment and care planning. Patients experienced eight interpersonal processes as having positive impact on their ability to make everyday changes. Engendering compassion is a central process that creates the space for the other processes to occur successfully. White space indicates processes that are initiated and take place during the encounter; grey space indicates patients’ lifeworld.

Findings shed light on the interpersonal work that lays the foundation for sharing decisions about a care plan that is responsive to the patient's individual root causes and achievable within their life context. Current clinical practice is grounded in guidelines 27 that are informed by a strong focus on weight, emphasizing diet and exercise, and behavioural, medical and surgical interventions 36. In our study, we found that there are important processes upstream from these recommendations that support accurate assessment and care planning that takes patients’ life context and value goals into account.

In obesity care, root causes cannot be presumed; rather we found that it is crucial for patient and provider together to make sense of drivers of obesity considering the context of personal lives and the larger socioeconomic environment. Ogden et al. 37 concluded that people's perception of life events and their relationship to food as coping are related to weight gain or loss. Becoming aware of personal patterns of life events, appraisal, and food as coping through the proposed approach, in concert with strengthening self‐acceptance, appeared to help people address emotional issues directly and find alternative coping strategies.

This is particularly important in a population that is impacted by stigma and stereotyping within their social environment, in personal, professional and healthcare context. Obesity management needs to address the effects of stigma on people living with obesity 38. Our data bears witness to how people living with obesity internalize socio‐cultural discourses of blame and shame 10 that need to be shifted to foster well‐being, confidence, self‐acceptance and intrinsic motivation 39. Furthermore, misconceptions about physiopathology and chronicity of obesity, including unrealistic expectations for weight loss, need to be reframed and shifted. Our findings confirm the need to expand medical training to include current obesity evidence and management options 6.

Using these insights as a foundation, primary care providers can then, in partnership with patients, plan and prioritize care that supports people to live at their best despite the presence of symptoms and challenges. As a result, patients experienced a greater sense of self‐compassion, agency, confidence, and motivation and initiated changes that made sense medically, emotionally and practically in their lives. There is emerging evidence that self‐compassion supports sustainable behaviour change 40.

The importance of an orientation on whole‐person health over weight that this study found resonates with findings on adverse health effects of weight cycling and emphasis on weight loss 41. Aiming at improving ‘Health at every size’ has been shown to have promising impacts on physical, behavioural and psychological health 42.

Integrating narrative with clinical practice enhances patient inner motivation, self‐reflection and self‐awareness, re‐construction of life stories, resulting in relief and distancing from sad feelings 43. Substantive research in health psychology demonstrates the positive effects of writing on physical and psychological health 44, 45. Journaling may constitute an important tool in obesity management by supporting emotional well‐being, coping with stressors and alignment of lifestyle changes with intrinsic value.

The goal of the proposed 5AsT personalized approach is to support patients in living life at the best possible function and well‐being despite the presence of symptoms. This is especially important in chronic diseases that limit function, and when root causes include trauma, stress and emotional difficulties. There is evidence that fostering psychological flexibility and acceptance of what cannot be changed helps people to maintain their health routines instead of giving up in frustration 46. To achieve this, focus on values instead of specific goals has been shown to result in greater sustained weight loss 47, 48. The proposed approach mirrors this principle by orienting people on value goals to maintain flexibility in the face of ever changing physical and contextual challenges.

Importantly, our findings contribute a better understanding of how primary care providers can impact health through communication. Street et al. 49 proposed seven pathways from care communication to health including access to appropriate care, knowledge and shared understanding, therapeutic alliance, patient ability to manage emotions, improving social support, patient empowerment and agency, as well as higher quality decisions. Our proposed 5AsT personalized approach integrates aspects of each of these.

A recent qualitative review on patient capacity in chronic disease found that capacity results from reshaping biographies to include chronic conditions, mobilizing resources, the experience of accomplishment and supportive social networks 50. This resonates with our study where collaborative, compassionate, and responsive care communication resulted in shifts in believes about self and health that strengthened patients’ sense of agency and activation and supported their efforts to improve and sustain health.

The proposed 5AsT approach for personalized obesity assessment and care planning has practical implications for interdisciplinary care. Comprehensive assessment and focus on whole‐person health allows provider and patient to negotiate personalized road maps for care that uses allied health professionals in an appropriate and timely manner. Findings also have implications for design and testing of interventions. A better understanding of how people come to new understandings of themselves and their health in communication with providers and integrate these in their everyday life context informs choice of theoretical frameworks and suitable outcomes measures.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is its in‐depth, qualitative approach, direct observation of consultations and exploration of everyday life impacts. Based on participant characteristics, our findings may be applicable to a primary care population with obesity and multi‐morbidity. Since a majority identified as Caucasian, our results need further investigation in diverse ethno‐cultural communities, rural and vulnerable populations. A limitation may be the time needed for the initial assessment. In this study, additional time was needed to gather medical history. Feedback from PCN clinicians suggested that not all processes have to occur in one consultation, follow‐ups can be brief and supported by allied health professionals. Future research should test the approach embedded in a long‐term primary care relationship leveraging interdisciplinary teams. There is a need to identify and test suitable outcome measures that can capture and quantify the impacts and outcomes we found. The proposed approach may require providers to obtain additional training. Ongoing work focuses on developing tools to guide providers through the conversation.

Conclusion

This research identified key processes of interpersonal work, their impacts and pathways to patient important outcomes to propose a practical approach to talking with patients about obesity in primary care. Outcomes include improved physical and psychological health and highlight the benefits of embracing the complexity of obesity to achieve sensible care plans. Findings suggest that for people who are willing to talk about weight with their provider, the proposed 5AsT personalized approach fosters emphatic care relationships, results in cognitive and emotional shifts that support patients in making sustainable changes to improve health and optimizes interdisciplinary team care to avoid misplaced efforts.

Conflict of Interest Statement

No conflict of interest was declared.

Author contributions

DLCS is the principle investigator and conceived of the study. DLCS obtained funding, supervised TL, contributed to data collection, analysis, interpretation of results and revision of the manuscript. TL was the postdoctoral fellow on the team and involved in study concept and design, recruitment, consultations with the partner organization, obtained funding, conducted interviews and analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RA contributed to study concept and design, data collection, interpretation and validation of results. AMS was instrumental in interpretation of results and revised it critically with important intellectual content. All authors have approved the final version of the article.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank our patient advisors as well as the receptionists, clinicians, and management of the PCN for their support and interest in the study, especially Robin Anderson and Jessica Schaub. We thank Patrick von Hauff for figure design. Melanie Heatherington for relentless support with recruitment, formatting and submission process. This work was supported by Mitacs through the Mitacs Accelerate program and through Alberta Innovates Health Solutions [grant number 201200852].

References

- 1. Janke EA, Ramirez ML, Haltzman B, Fritz M, Kozak AT. Patient's experience with comorbidity management in primary care: a qualitative study of comorbid pain and obesity. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2016; 17: 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heintze C, Metz U, Hahn D et al Counseling overweight in primary care: an analysis of patient–physician encounters. Patient Educ Couns 2010; 80: 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Torti J, Luig T, Borowitz M et al The 5As team patient study: patient perspectives on the role of primary care in obesity management. BMC Fam Pract 2017; 18: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramos Salas X, Forhan M, Caulfield T, Sharma AM, Raine K. A critical analysis of obesity prevention policies and strategies. Can J Public Health 2018; 108: 598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greener J, Douglas F, van Teijlingen E. More of the same? Conflicting perspectives of obesity causation and intervention amongst overweight people, health professionals and policy makers. Soc Sci Med 2010; 70: 1042–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dietz WH, Baur LA, Hall K et al Management of obesity: improvement of health‐care training and systems for prevention and care. Lancet 2015; 385: 2521–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rzehak P, Meisinger C, Woelke G et al Weight change, weight cycling and mortality in the ERFORT Male Cohort Study. Eur J Epidemiol 2007; 22: 665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaplan LM, Golden A, Jinnett K et al Perceptions of barriers to effective obesity care: results from the National ACTION Study. Obesity 2018; 26: 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Forhan M, Salas XR. Inequities in healthcare: a review of bias and discrimination in obesity treatment. Can J Diabetes 2013; 37: 205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kirk SFL, Price SL, Penney TL et al Blame, shame, and lack of support: a multilevel study on obesity management. Qual Health Res 2014; 24: 790–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sharma AM, Padwal R. Obesity is a sign – over‐eating is a symptom: an aetiological framework for the assessment and management of obesity. Obes Rev 2010; 11: 362–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garip G, Yardley L. A synthesis of qualitative research on overweight and obese people's views and experiences of weight management: overweight and obese people's views. Clin Obes 2011; 1: 110–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown I, Gould J. Decisions about weight management: a synthesis of qualitative studies of obesity. Clin Obes 2011; 1: 99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rose S, Poynter P, Anderson J, Noar S, Conigliaro J. Physician weight loss advice and patient weight loss behavior change: a literature review and meta‐analysis of survey data. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013; 37: 118–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McHale CT, Laidlaw AH, Cecil JE. Direct observation of weight‐related communication in primary care: a systematic review. Fam Pract 2016; 33: 327–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carvajal R, Wadden TA, Tsai AG, Peck K, Moran CH. Managing obesity in primary care practice: a narrative review. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2013; 1281: 191–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Burgess E, Hassmén P, Pumpa KL. Determinants of adherence to lifestyle intervention in adults with obesity: a systematic review. Clin Obes 2017; 7: 123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Campbell‐Scherer DL, Asselin J, Osunlana AM et al Implementation and evaluation of the 5As framework of obesity management in primary care: design of the 5As Team (5AsT) randomized control trial. Implement Sci 2014; 9: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Asselin J, Osunlana AM, Ogunleye AA, Sharma AM, Campbell‐Scherer D. Missing an opportunity: the embedded nature of weight management in primary care. Clin Obes 2015; 5: 325–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ogunleye A, Osunlana A, Asselin J et al The 5As team intervention: bridging the knowledge gap in obesity management among primary care practitioners. BMC Res Notes 2015; 8: 810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Obesity Canada 2018. 5As Team [WWW document]. URL https://obesitycanada.ca/5as‐team/ [2018, September 10]

- 22. Asselin J, Osunlana A, Ogunleye A, Sharma A, Campbell‐Scherer D. Challenges in interdisciplinary weight management in primary care: lessons learned from the 5As Team study. Clin Obes 2016; 6: 124–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patton MQ (ed) Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. 4th edn. SAGE Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sharma AM. The 5A model for the management of obesity. Can Med Assoc J 2012; 184: 1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Osunlana AM, Asselin J, Anderson R et al 5As Team obesity intervention in primary care: development and evaluation of shared decision‐making weight management tools. Clin Obes 2015; 5: 219–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kushner RF. Clinical assessment and management of adult obesity. Circulation 2012; 126: 2870–2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lau DCW, Douketis JD, Morrison KM et al 2006 for members of the Obesity Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Panel Canadian clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in adults and children [summary]. CMAJ 2007; 176: S1–S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Piana N, Battistini D, Urbani L et al Multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention in the obese: its impact on patients’ perception of the disease, food and physical exercise. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2013; 23: 337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elwyn G, Lloyd A, May C et al Collaborative deliberation: a model for patient care. Patient Educ Couns 2014; 97: 158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sharma A, Kushner R. A proposed clinical staging system for obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009; 33: 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Freedhoff Y, Sharma A. Best weight: a practical guide to office‐based obesity management. 2015. [WWW document]. URL https://obesitycanada.ca/publications/best-weight-book/ [2018, September 10]

- 32. Vermunt NP, Harmsen M, Elwyn G et al A three‐goal model for patients with multimorbidity: a qualitative approach. Health Expect 2018; 21: 528–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Frank AW. Practicing dialogical narrative analysis. In: Holstein JA, Gubrium JF (eds). Varieties of narrative analysis. SAGE Publications Ltd: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2012, pp 33–52. 10.4135/9781506335117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 2001; 358: 483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kitto SC, Chesters J, Grbich C. Quality in qualitative research. Med J Aust 2008; 188: 243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brauer P, Connor Gorber S, Shaw E et al Recommendations for prevention of weight gain and use of behavioural and pharmacologic interventions to manage overweight and obesity in adults in primary care. CMAJ 2015; 187: 184–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ogden J, Stavrinaki M, Stubbs J. Understanding the role of life events in weight loss and weight gain. Psychol Health Med 2009; 14: 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rand K, Vallis M, Aston M et al “It is not the diet; it is the mental part we need help with.” A multilevel analysis of psychological, emotional, and social well‐being in obesity. Int J Qual Stud Health Well‐Being 2017; 12: 1306421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vallis M. Quality of life and psychological well‐being in obesity management: improving the odds of success by managing distress. Int J Clin Pract 2016; 70: 196–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Palmeira L, Pinto‐Gouveia J, Cunha M. Exploring the efficacy of an acceptance, mindfulness & compassionate‐based group intervention for women struggling with their weight (kg‐free): a randomized controlled trial. Appetite 2017; 112: 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Matheson E, King D, Everett C. Healthy lifestyle habits and mortality in overweight and obese individuals. J Am Board Fam Med 2005; 25: 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bacon L, Aphramor L. Weight science: evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift. Nutr J 2011; 10: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Maldonato A, Piana N, Bloise D, Baldelli A. Optimizing patient education for people with obesity: possible use of the autobiographical approach. Patient Educ Couns 2010; 79: 287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Frattaroli J. Experimental disclosure and its moderators: a meta‐analysis. Psychol Bull 2006; 132: 823–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lepore S, Smyth J. The Writing Sure: How Expressive Writing Promotes Health and Emotional Well‐being. American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Harris R. ACT Made Simple: An Easy‐To‐Read Primer on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Forman EM, Butryn ML, Manasse SM et al Acceptance‐based versus standard behavioral treatment for obesity: results from the mind your health randomized controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016; 24: 2050–2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Butryn ML, Forman EM, Lowe MR et al Efficacy of environmental and acceptance‐based enhancements to behavioral weight loss treatment: the ENACT trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017; 25: 866–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns 2009; 74: 295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Boehmer KR, Gionfriddo MR, Rodriguez‐Gutierrez R et al Patient capacity and constraints in the experience of chronic disease: a qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMC Fam Pract 2016; 17: 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]