Abstract

Muscle degenerative diseases such as Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy are incurable and treatment options are still restrained. Understanding the mechanisms and factors responsible for muscle degeneration and regeneration will facilitate the development of novel therapeutics. Several recent studies have demonstrated that Galectin-1 (Gal-1), a carbohydrate-binding protein, induces myoblast differentiation and fusion in vitro, suggesting a potential role for this mammalian lectin in muscle regenerative processes in vivo. However, the expression and localization of Gal-1 in vivo during muscle injury and repair are unclear. We report the expression and localization of Gal-1 during degenerative–regenerative processes in vivo using two models of muscular dystrophy and muscle injury. Gal-1 expression increased significantly during muscle degeneration in the murine mdx and in the canine Golden Retriever Muscular Dystrophy animal models. Compulsory exercise of mdx mouse, which intensifies degeneration, also resulted in sustained Gal-1 levels. Furthermore, muscle injury of wild-type C57BL/6 mice, induced by BaCl2 treatment, also resulted in a marked increase in Gal-1 levels. Increased Gal-1 levels appeared to localize both inside and outside the muscle fibers with significant extracellular Gal-1 colocalized with infiltrating CD45+ leukocytes. By contrast, regenerating muscle tissue showed a marked decrease in Gal-1 to baseline levels. These results demonstrate significant regulation of Gal-1 expression in vivo and suggest a potential role for Gal-1 in muscle homeostasis and repair.

Keywords: Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, degeneration–regeneration, galectin-1, skeletal muscle, mdx mice

Introduction

Muscle degeneration, as found in genetic diseases such as Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), results in significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. Specifically, DMD results from mutations in dystrophin, a component of the sarcolemmal complex that connects the actin cytoskeleton to the extracellular matrix. Muscle pathology ultimately results in progressive skeletal muscle wasting, leading to death in the second decade of life due to cardiac or respiratory failure (Blake et al. 2002; Emery 2002). Current treatment options fail to significantly reduce pathology, largely due to an incomplete understanding of the muscle degenerative and regenerative processes (Deconinck and Dan 2007; Radley et al. 2007).

Several animal models are currently used in an effort to elucidate the mechanisms underlying DMD pathology. The murine mdx model, the most commonly studied animal model of DMD, exhibits many key features of human DMD, including sarcolemmal instability, Ca2+ influx, myofiber apoptosis and necrosis, fibrosis, inflammation, and elevated serum creatinine kinase (CK) levels (Bulfield et al. 1984; Watchko et al. 2002; Collins and Morgan 2003). These features are intensified when the animals are submitted to compulsory physical activity (Brussee et al. 1997; Fraysse et al. 2004; De Luca et al. 2005). Importantly, regeneration, characterized by centrally localized nuclei, follows degeneration in the mdx model, allowing studies of expression and localization of proteins putatively involved in degenerative and regenerative muscle processes (Blake et al. 2002; Watchko et al. 2002; Collins and Morgan 2003).

Several studies implicate galectin-1 (Gal-1) in the development of skeletal muscle (Watt et al. 2004; Kami and Senba 2005). Gal-1 is a carbohydrate-binding protein expressed by many cells including myoblasts (Goldring, Jones, Thiagarajah, et al. 2002; Stowell, Arthur, et al. 2008). Gal-1 expression exhibits unique regulation during development; it is predominately expressed in the cytosol during myoblast stages, followed by peak expression and extracellular secretion, prior to fusion of myoblast into multinucleated muscle cells (Nowak et al. 1976; Barondes and Haywood-Reid 1981; Cooper and Barondes 1990; Harrison and Wilson 1992; Poirier et al. 1992; Watt et al. 2004). Gal-1 induces myoblast proliferation and fusion in vitro (Den and Malinzak 1977; Gartner and Podleski 1975; Watt et al. 2004) and inhibits myoblast α7β1 integrin-mediated interactions with laminin (Cooper et al. 1991; Gu et al. 1994), suggesting that secretion of Gal-1 into the extracellular milieu may facilitate fusion in vivo. Consistent with a role for Gal-1 in initiating myoblast fusion, Gal-1-null mice show reduced myofiber formation in vivo (Watt et al. 2004; Georgiadis et al. 2007).

In addition to putative roles of Gal-1 in muscle development, several studies suggest that Gal-1 may also mediate several aspects of muscle regeneration. Gal-1 induces dermal fibroblasts to express muscle-specific markers such as desmin (Goldring, Jones, Sewry, et al. 2002). Gal-1-null mice also experience impaired capacity to regenerate muscle tissue following injury (Watt et al. 2004; Georgiadis et al. 2007). In addition, Gal-1 exhibits a protective effect on tissue during damage, possibly through reducing the deleterious sequelae associated with inflammation (Rabinovich et al. 2000). Indeed, Gal-1 induces the turnover of activated neutrophils, whose unchecked activity can damage viable tissue when not properly removed (Dias-Baruffi et al. 2003; Stowell et al. 2007; Stowell, Qian, et al. 2008). Clearly, Gal-1 exhibits significant biological effects on the development and maintenance of muscle tissue.

While in vitro and in vivo studies suggest a critical role for Gal-1 in regeneration, the expression and localization of Gal-1 following muscle injury and during regeneration remain unclear. Although potential mechanisms whereby Gal-1 could potentially induce regeneration exist, it is not known whether Gal-1 expression and localization during muscle damage and repair correlate with these putative functions. In this study, we have examined the expression and localization of Gal-1 during muscle degeneration and regeneration using two animal models of muscular dystrophy and in muscle injury. Gal-1 expression and extracellular localization increased following degeneration, while decreasing over time during regenerative stages. Gal-1 exists in highly organized patterns in healthy-striated tissue, which largely became less organized during degeneration. These results provide important insight into Gal-1 expression and localization in vivo during muscle degeneration and regeneration and suggest that Gal-1 is a key factor in promoting muscle healing following damage.

Results

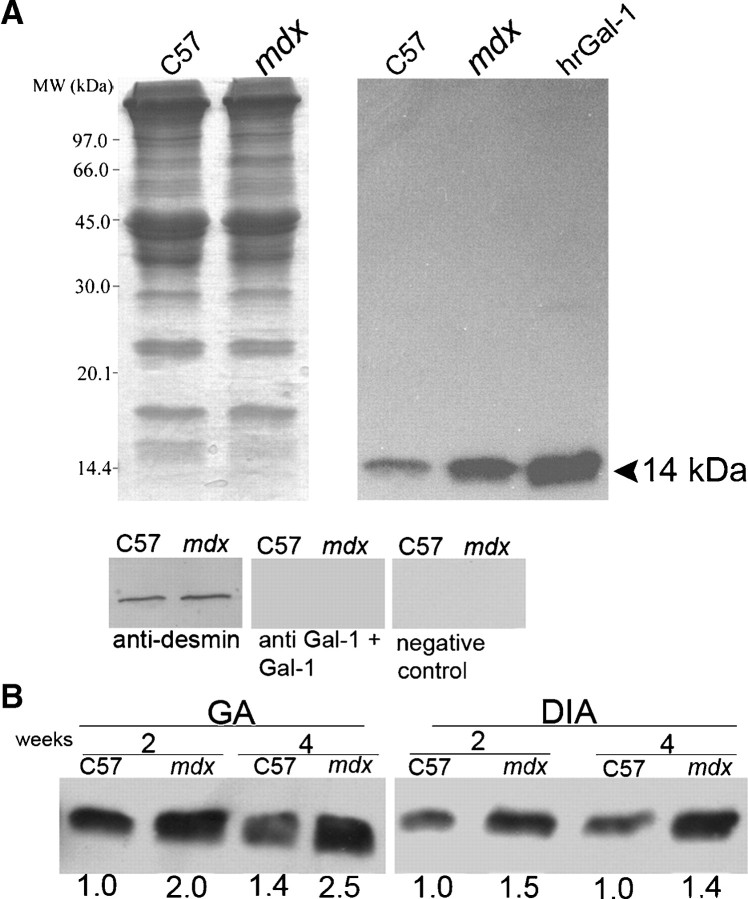

Galectin-1 level is increased in dystrophic skeletal muscles

To determine whether Gal-1 levels differ in mdx compared to wild-type (wt) C57BL/6 mice, we first examined the specificity of the anti-Gal-1 antibody preparation. Western blot analysis of C57BL/6, mdx, and the human recombinant Gal-1 (hrGal-1) revealed a single immunoreactive band at 14 kDa, indicating specific detection of Gal-1 (Figure 1A). Furthermore, incubation of the anti-Gal-1 antibody with recombinant Gal-1 prior to detection blocked Gal-1 recognition, further demonstrating specific detection of Gal-1 (Figure 1A). No staining was observed in the absence of the anti-Gal-1 antibody (Figure 1A, negative control).

Fig. 1.

Increased expression of Gal-1 in skeletal muscles of mdx mice. (A) Coomassie blue-stained gel of equal amounts of protein extracts from gastrocnemius (GA) of wild-type C57BL/6 (C57) and mdx mice. Right panel: An equivalent blot of muscle samples and purified human recombinant Gal-1 (hrGal-1, 1 μg positive control) probed with 0.25 μg/mL anti-Gal-1. Samples of C57 and mdx GA were probed with anti-desmin as constitutive control; anti-Gal-1 preincubated with purified hrGal-1, and only the secondary antibody (negative control). (B) Western blot analysis of Gal-1 expression in GA and diaphragm (DIA) muscles of 2-week- and 4-week-old C57 and mdx mice. A single band was detected in the region expected to Gal-1 (14 kDa) with higher intensity in the mdx samples. The numbers below the bands indicate the relative quantity of Gal-1 expression in the tissue extracts in relation to the 2-week-old C57 sample for each muscle and are representative of three independent experiments. The intensities of the bands were calculated using the 1.37v Image-J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Importantly, Gal-1 was expressed at higher levels in mdx compared to wt C57BL/6 mice (Figure 1A). To determine whether increased Gal-1 expression in mdx mice reflected differences associated with muscle pathology or underlying differences in constitutive expression, we examined Gal-1 expression in both gastrocnemius (GA) and diaphragm (DIA) muscles before (at 2 weeks) and after the onset of necrosis (4 weeks) in mdx mice compared to wt mice (Radley and Grounds 2006). In both muscles and in both ages tested, we observed a remarkably higher expression of Gal-1 (at least 40%) when compared with mdx and age-matched wild-type mice, indicating that mdx mice display higher constitutive levels of Gal-1 expression (Figure 1B). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the antibody specifically recognized Gal-1 in muscle tissue and that mdx mice exhibit increased Gal-1 expression when compared to C57BL/6 mice.

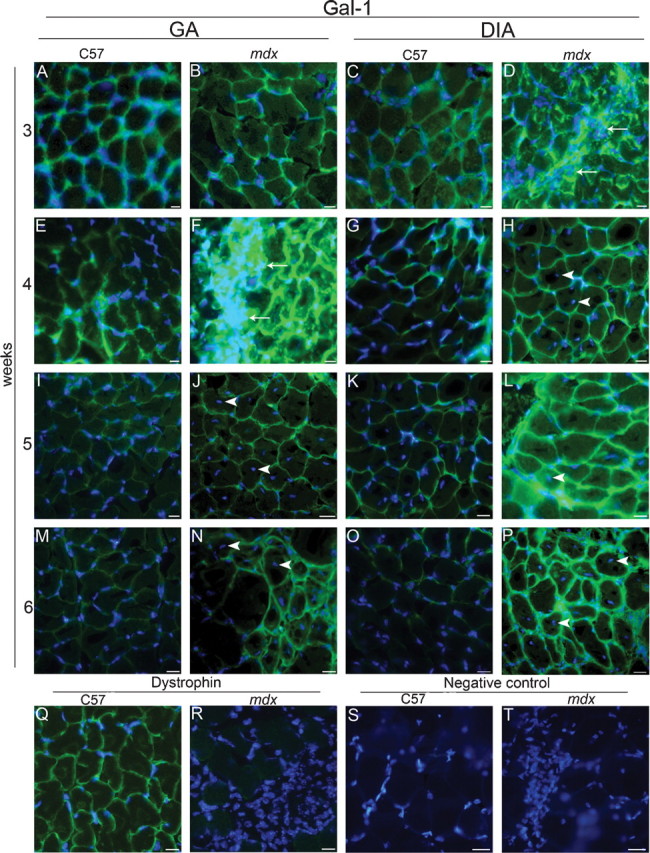

Galectin-1 is mainly located around myofibers and follows the muscle degeneration wave

Although mdx mice clearly express higher constitutive levels of Gal-1, we questioned whether levels of Gal-1 expression change during degenerative and regenerative processes, as might be expected from previous in vitro results (Goldring, Jones, Thiagarajah, et al. 2002; Watt et al. 2004). During muscle degeneration, which peaks at 3–4 weeks (Collins and Morgan 2003), Gal-1 expression increased and appeared to localize around myofibers in both GA and DIA (Figure 2). Gal-1 expression not only increased within muscle tissue, but also concentrated in areas with high cell density as indicated by DAPI staining (Figure 2D, F arrows). Importantly, following peak degeneration, Gal-1 levels decreased in the GA muscle during stages of active regeneration, indicated by the increased presence of mostly centrally nucleated myofibers, as opposed to peripherally, oriented nuclei (Figure 2J, N arrowheads), suggesting that Gal-1 specifically increases in response to muscle degeneration.

Fig. 2.

The mdx mice exhibit increased expression and extracellular localization of Gal-1 in the gastrocnemius (GA) and diaphragm (DIA) muscles during the degeneration wave. Analyzed muscles are indicated at the top: GA (A, B, E, F, I, J, M, N, Q to T) and DIA (C, D, G, H, K, L, O, P), from C57BL/6 (C57) and mdx, placed side by side. Ages are indicated at the left: 3 weeks (A–D), 4 weeks (E–H, Q–T), 5 weeks (I–L), and 6 weeks (M–P). Muscular sections were labeled using anti-Gal-1 (A–P), anti-dystrophin (Q and R), and a secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa-488. Areas containing high density of cells (DAPI staining) show more intense labeling of Gal-1 (arrows in D and F). Nonperipherally nucleated myofibers, detected only in mdx muscles and mainly in the GA, are indicated by arrowheads in the GA (J, N) and in the DIA (H, L, P). Sarcolemmal dystrophin immunostaining confirmed wt and mdx phenotype (representative images in Q and R). Negative control (absence of primary antibody) is showed in S and T. Nuclei are stained with DAPI. Bar = 10 μm.

In contrast to most skeletal muscle in mdx mice, the DIA muscle fails to regenerate following degeneration (La Porte et al. 1999). Gal-1 expression in the DIA seemed not to decrease in expression over time (Figure 2D, H, L, P), although some centrally nucleated myofibers could be detected (Figure 2H, L, P arrowheads). As expected, mdx mice failed to stain with dystrophin (Figure 2R) and isotype controls failed to exhibit similar staining, demonstrating that staining represented specific detection of Gal-1 (Figure 2S, T).

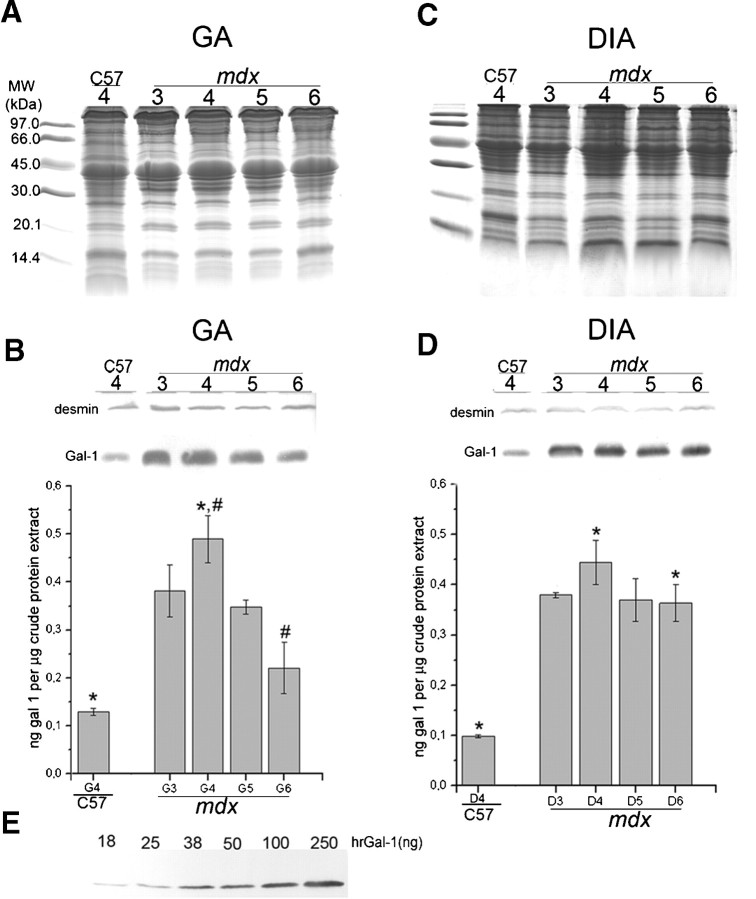

Since Gal-1 levels appeared to change during degeneration and regeneration in the GA muscle, we examined whether variation in Gal-1 expression represented age-related or regeneration-related changes (Figure 3). To quantitatively examine the increase of Gal-1 expression during degenerative stages of muscle pathology, we blotted equivalent amounts of GA and DIA muscles from 3- to 6-week-old mdx and 4-week-old C57BL/6 mice (Figure 3A, C); desmin was labeled as constitutive control (Figure 3B, D). Gal-1 expression in the GA mdx muscle significantly increased during degenerative stages, with a peak in the fourth week (*P = 0.0002 when compared to age-matched C57BL/6) (Figure 3B). This data corroborate expression levels observed by immunofluorescence analysis (Figure 2F). Importantly, Gal-1 levels also decreased during stages of muscle regeneration in the mdx mice (#P = 0.0025 when compared the fourth to the sixth weeks in the GA; Figure 3B). In addition, Western blot analysis of Gal-1 expression demonstrated sustained increased expression of Gal-1 in the DIA (Figure 3D), consistent with immunofluorescence analysis (Figure 2D, H, L, P). Gal-1 appeared to be expressed at levels in excess of approximately four times in relation to the C57BL/6 mice (*P = 0.0002 and P = 0.0003, for the fourth and sixth weeks, respectively), as determined by relative staining of known amounts of the human recombinant Gal-1 (Figure 3E). In contrast, in DIA we did not detect significant difference in the Gal-1 level between the fourth and sixth week (P = 0.0571). These results demonstrate that Gal-1 expression increases during degeneration in both muscles, while decreasing toward basal levels during regenerative phases in the GA, a muscle in which regeneration is prominent.

Fig. 3.

Quantitative analysis confirms the increase of Gal-1 expression in the gastrocnemius (GA) and diaphragm (DIA) muscles during degeneration. (A and C) Coomassie-blue stained gels containing samples of GA and DIA of C57BL/6 (C57: 4-week-old mice) and mdx (3- to 6-week-old mice). (B and D) Equivalent immunoblots probed with anti-Gal-1 (and anti-desmin as constitutive control) were quantified by band densitometry. (E) Immunoblot with crescent amounts of hrGal-1 (18–250 ng/lane) used to build a standard curve to estimate Gal-1 content. In mdx GA (B), the expression of Gal-1 reaches a peak at 4 weeks (*P = 0.0002 when compared to age-matched C57) and decreases in the fifth and the sixth weeks (#P = 0.0025), resembling the degeneration curve observed in this period. In mdx DIA, no statistical significance was observed in Gal-1 expression between weeks, only in relation to the C57 mice (*P = 0.0002 and P = 0.0003, for the fourth and sixth weeks, respectively).

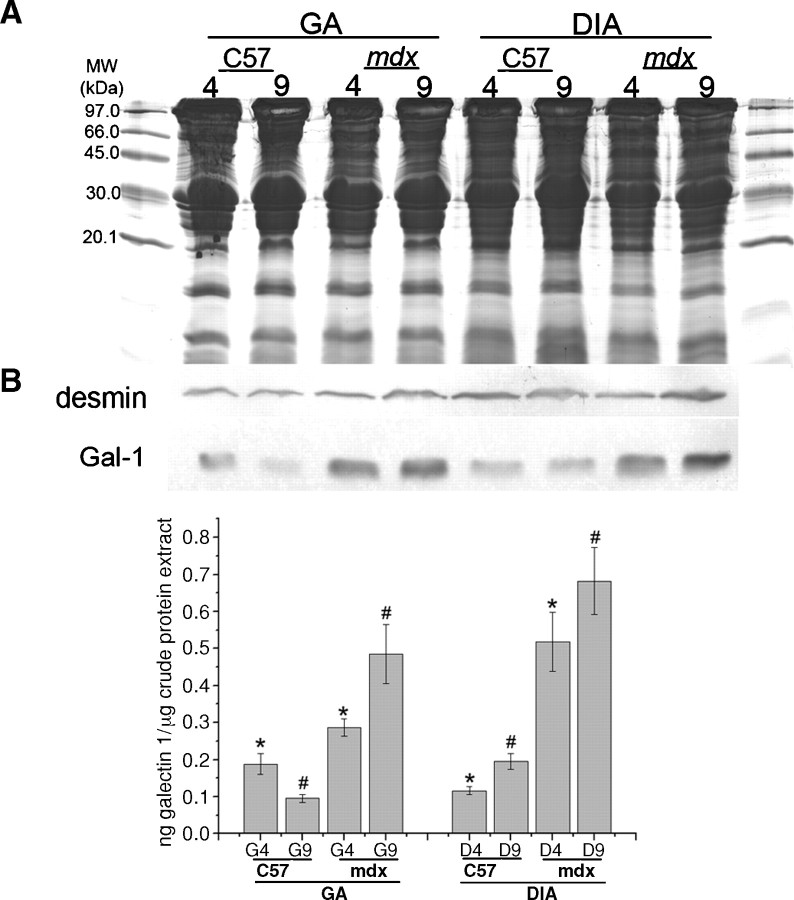

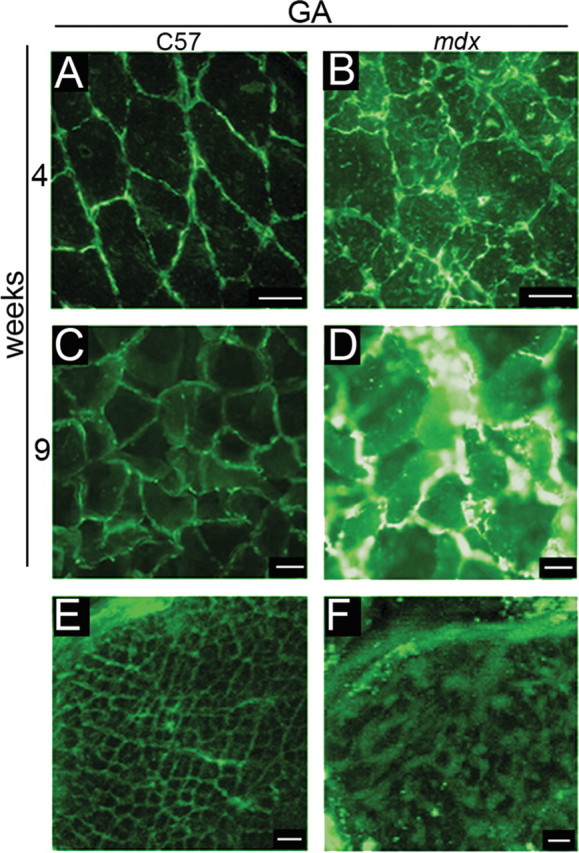

Compulsory physical activity sustains high levels of Gal-1 in dystrophic muscles

Compulsory exercise exacerbates muscle degeneration in mdx mice while reducing regenerative capacity (Tseng et al. 2002; De Luca et al. 2005). Because Gal-1 levels in the GA muscle decreased during regeneration, we determined whether exercise would result in sustained Gal-1 levels, as occurred in the DIA. Unlike sedentary mdx mice, Gal-1 levels in the GA muscle of mice subjected to 5 weeks of compulsory exercise beginning at the peak of degeneration, exhibited sustained levels of increased Gal-1 expression (Figure 4B, D, F). Gal-1 localization in degenerative muscle appeared less organized than in control mice, both surrounding the sarcolemma (Figure 4A, B, C, D) and within the sarcoplasm (Figure 4 E, F). Western blot analysis of equivalent amounts of both GA and DIA muscles obtained following subjection to the same regimen corroborated these results (Figure 5A, B). As shown in Figure 5B, we observed higher Gal-1 levels in mdx in comparison with C57BL/6 mice for both muscles in the two analyzed ages (*P = 0.0003 and #P < 0.0001 for GA, 4-week-old and 9-week-old mice, respectively and *P = 0.0031 and #P = 0.0021 for DIA, 4-week-old and 9-week-old mice). More detailed images can be seen in the 3D confocal microscopy movies 1 C57BL/6 (Supplemental Figure 1) and 2mdx (Supplemental Figure 2) in supplementary data. These results demonstrate that Gal-1 levels increase during degeneration and remain sustained until the onset of regeneration. Importantly, the localization of Gal-1 appears to also change in conjunction with pathological features of muscle degeneration (Figure 4E, F).

Fig. 4.

Compulsory physical activity results in the sustained increase of Gal-1 expression in the gastrocnemius (GA) muscle of mdx mice. Representative immunohistochemical analysis of Gal-1 in GA muscle of C57BL/6 (C57) (A, C, E) and mdx (B, D, F) mice using an anti-Gal-1 antibody and Alexa 488 conjugated secondary antibody. The mdx mouse presents a higher level of Gal-1 than its age matched C57 before (B versus A, 4 weeks) and after the period of physical activity (D versus C, 9 weeks). Gal-1 in the C57 (E) is apparently located in myofibrils in a quite organized pattern and in the mdx myofiber (F), this pattern is not observed. Bar: 10 μm for A–D and 2 μm for E and F.

Fig. 5.

Quantitative analysis confirms the sustained increase in Gal-1 expression in skeletal muscle of mdx mice after compulsory physical activity. (A) Coomassie blue-stained gel of equal quantities of GA and DIA samples of C57BL/6 (C57) and mdx mice before (4) and after (9) 5 weeks of physical activity. (B) Equivalent immunoblot probed with anti-Gal-1 (and anti-desmin as constitutive control) were quantified by band densitometry. Graphic shows statistical differences in Gal-1 levels in mdx in comparison with C57 mice for both muscles in the two analyzed ages (*P = 0.0003 and #P < 0.0001 for GA, 4-week-old and 9-week-old mice, respectively and *P = 0.0031 and #P = 0.0021 for DIA, 4-week-old and 9-week-old mice). Physical activity resulted in sustained levels of increased Gal-1 expression in the mdx mice.

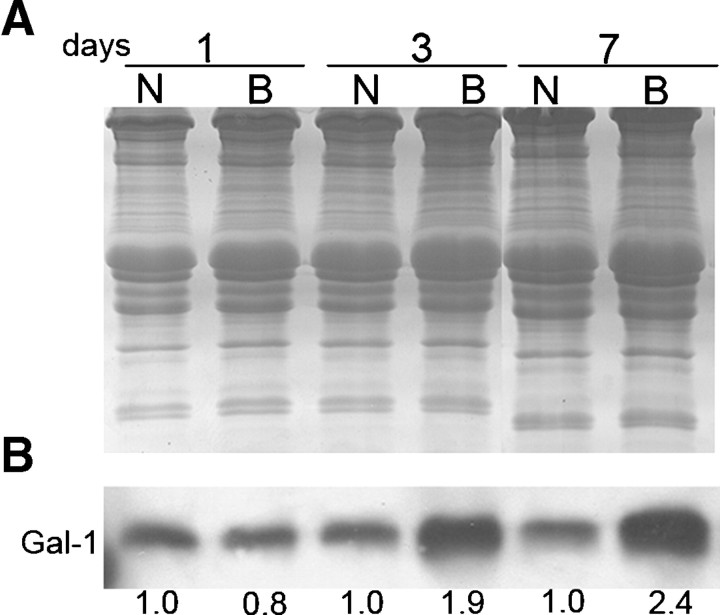

Increased levels of Gal-1 in GA of C57BL/6 mice after injury induced by BaCl2

To determine whether the expression of Gal-1 associated with degeneration and regeneration specifically reflected changes in mdx mice, or whether these alterations in expression occurred in other forms of muscle damage, we examined Gal-1 expression in C57BL/6 mice following muscle damage induced by BaCl2. As shown in Figure 6, similar to Gal-1 expression in mdx mice, Gal-1 levels peaked during degeneration starting from day 3, with the higher expression 7 days after the lesion (approximately 240% in relation to the control). Importantly, increased Gal-1 levels appeared to localize predominately around myofibers, with Gal-1 specifically localized both extracellularly and intracellularly (Supplemental Figure 3). Taken together, these results demonstrate that increased Gal-1 expression not only occurs as a result of muscle degeneration resulting from genetic aberrations, but also increases during general muscle injury.

Fig. 6.

BaCl2 injection induces muscle injury and increased Gal-1 expression in C57BL/6 mice. (A) Coomassie blue-stained gel of equal quantities of GA samples of C57BL/6 (C57) following injection with either NaCl (N) or BaCl2 (B) at the indicated times (1, 3, and 7 days after the injection). (B) Immunoblot analysis of Gal-1 expression in either NaCl-treated (N) or BaCl2-treated (B) animals. The numbers below the bands indicate the relative quantity of Gal-1 expression in the samples and are representative of three independent experiments. The intensities of the bands were calculated using the 1.37v Image-J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD). Gal-1 levels increased during degeneration starting from day 3, with the higher expression at day 7.

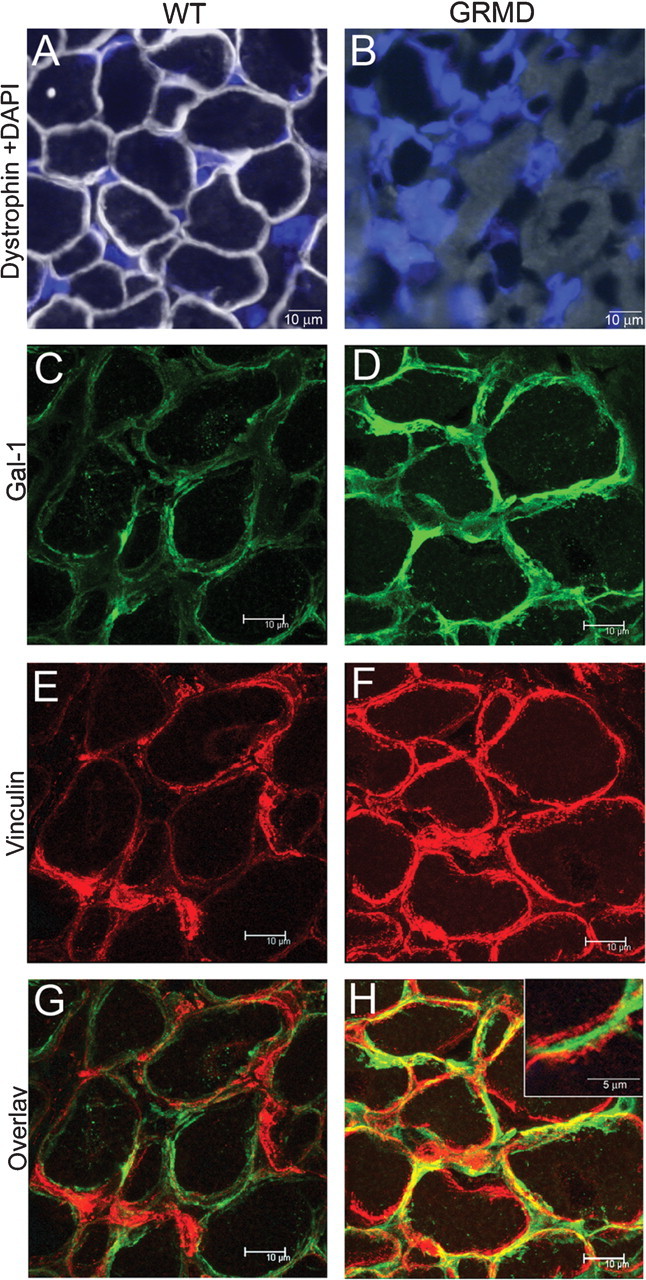

Gal-1 expression and localization in the Golden Retriever Muscular Dystrophy (GRMD) canine model for DMD

We further questioned whether alterations in Gal-1 expression associated with muscle pathology uniquely reflected murine muscle, or whether similar changes occurred in other animal models of muscular dystrophy. To this end, we examined Gal-1 expression in the canine dystrophy model, GRMD, which presents signs of muscle dystrophy from birth and close similarity to the DMD (Collins and Morgan 2003; Cooper et al. 1988). Like mdx mice, the GRMD canine muscle tissue failed to express dystrophin (Figure 7A, B). More importantly, GRMD muscle also exhibited higher expression of Gal-1 when compared to the wt (Figure 7C, D). Following injury, Gal-1 appeared to localize to both the extracellular and intracellular compartments, as vinculin, a focal adhesion protein associated with the inner leaflet of the sarcolemma, colocalized with Gal-1 in some areas of injury (Figure 7E, F, G, H and 3D confocal microscopy movies in Supplemental Figures 4 and 5). Furthermore, the staining intensity of vinculin also appeared to increase following injury, consistent with previous findings (Law et al. 1994; Hanft et al. 2006).

Fig. 7.

Localization of Gal-1 in GRMD femoral biceps. (A–B) Dystrophin staining in wt (A) or GRMD (B) femoral biceps. Nuclei are stained with DAPI. (C and D) Gal-1 staining of wt (C) or GRMD (D) femoral biceps sections. (E and F) Vinculin staining of wt (E) or GRMD (F) femoral biceps. (G and H) Overlay image of wt (G) or GRMD (H) for Gal-1 and vinculin. The region of tissue in which Gal-1 is localized mainly in the extracellular compartment (G, inset).

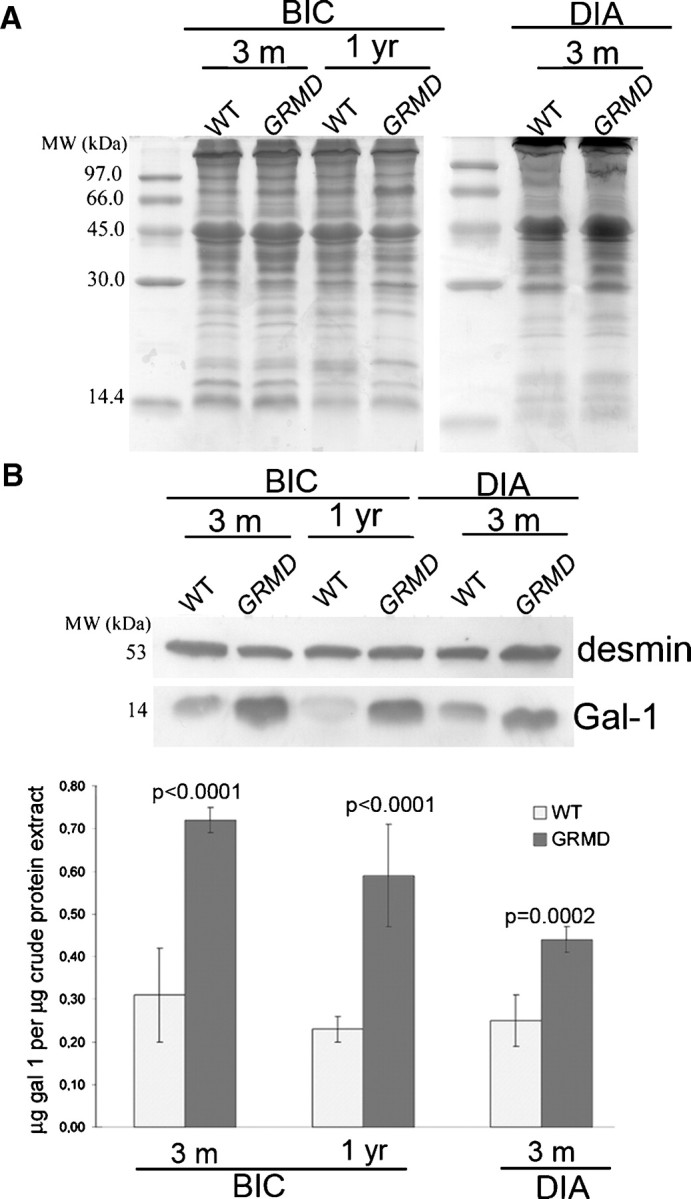

Western blot analysis using equivalent amounts of femoral biceps (from 3-month-old and 1-year-old dogs) and DIA (from 3-month-old dogs) also demonstrated increased expression of Gal-1 in GRMD muscle tissue (Figure 8A, B). We observed significantly higher expression of Gal-1 in femoral biceps of GRMD versus wt dogs, in both ages analyzed (P < 0.0001). The difference in Gal-1 expression in DIA, between 3-month-old normal and GRMD dogs, was also significant (P = 0.0002). Taken together, these results demonstrate that Gal-1 expression is increased in both murine models of dystrophy during degeneration and in dogs. Thus, these changes likely reflect alterations common to other mammals experiencing this type of muscle pathology.

Fig. 8.

Canine GRMD muscular dystrophy femoral biceps exhibits increased expression of Gal-1. (A) Coomassie blue-stained gel of equal quantities of femoral biceps (BIC) and DIA samples from 3-month-old and 1-year-old wild-type and GRMD dogs. (B) Equivalent immunoblots probed with anti-Gal-1 (and anti-desmin as constitutive control) were quantified by densitometry. In femoral biceps the differences comparing GRMD versus wild-type dogs were considered extremely significant (P < 0.0001) in both ages. The observed increase of Gal-1 level in DIA between wt and GRMD dog was also significant (P = 0.0002).

Extracellular Gal-1 colocalizes with CD45+ infiltrating leukocytes

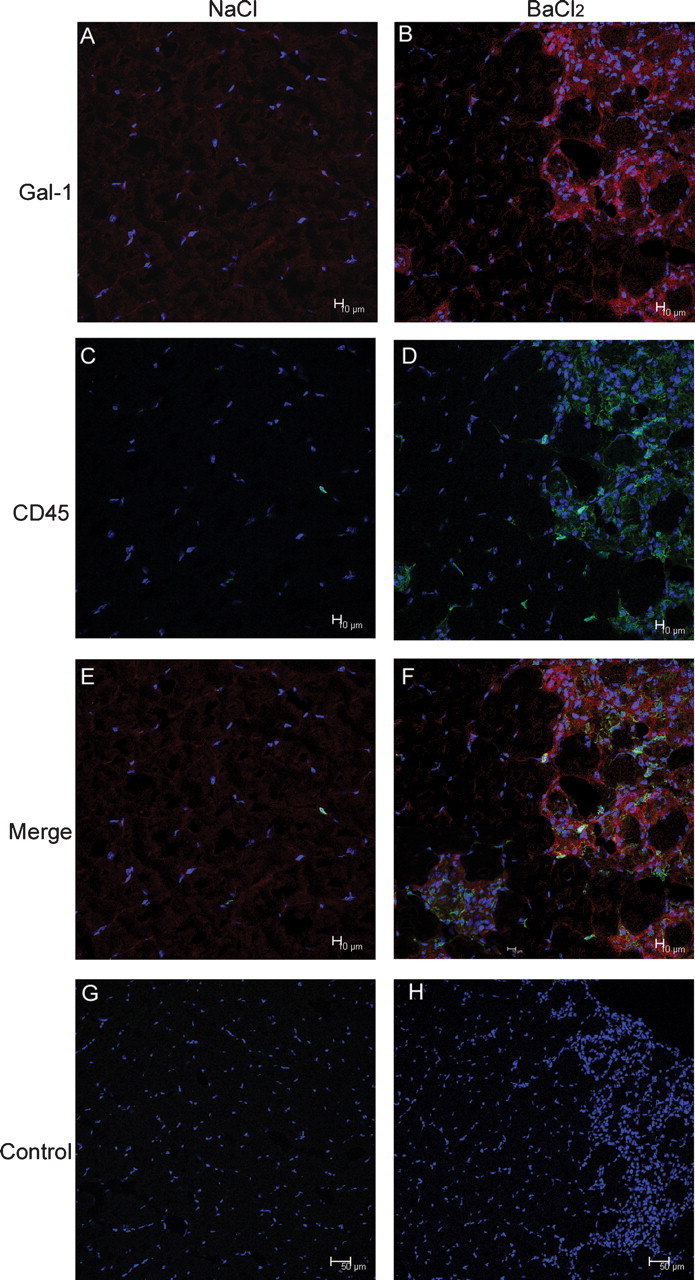

In addition to regulating muscle development and regeneration, several studies also suggest roles for Gal-1 in the modulation of leukocyte function and turnover (Dias-Baruffi et al. 2003; Stowell, Qian, et al. 2008). Consistent with this, Gal-1 appeared to localize around areas of significant cellular infiltrate which appeared to reflect leukocyte accumulations which commonly occur following many types of tissue injury (Figure 2F), suggesting the increased Gal-1 expression and release into the extracellular space may allow Gal-1 to interact with infiltrating leukocytes. However, whether this cellular accumulation (Figure 2F) represented leukocytes or some other cell type remained unknown. As a result, we examined Gal-1 localization and potential leukocyte infiltration following BaCl2-induced injury. Consistent with this, Gal-1 displayed increased expression following BaCl2-induced injury and localized around areas of cellular infiltrate (Figure 9A, B). To determine whether this cellular infiltrate represented leukocytes, we examined these cells for expression of the common leukocyte marker CD45+, previously suggested to be a ligand for Gal-1 (Nguyen et al. 2001). Importantly, Gal-1 significantly localized around CD45+ cells (Figure 9E and F), suggesting that endogenous Gal-1 may contact infiltrating leukocytes following injury. Taken together, these results suggest that in addition to directly regulating muscle differentiation and regeneration in vivo, Gal-1 may also facilitate muscle repair by favorably modulating leukocyte function, as suggested previously (Rabinovich et al. 2000).

Fig. 9.

Gal-1 colocalizes with infiltrating CD45+ leukocytes. GA samples of C57BL/6 following 3 days’ injection with either NaCl (A, C, E, and G) or BaCl2 (B, D, F, and H) were stained to Gal-1 and/or CD45. Nuclei are stained with DAPI. Negative control (absence of primary antibody) is showed in G and H. The increased muscle expression of Gal-1 is associated with tissue damage and the CD45+ cell localization. Bar = 10 μm. Gal-1

Discussion

Many studies demonstrate that Gal-1 has multiple effects on muscle cells in vitro (Nowak et al. 1976; Barondes and Haywood-Reid 1981; Cooper and Barondes 1990; Harrison and Wilson 1992; Poirier et al. 1992; Watt et al. 2004). However, Gal-1 expression and localization following muscle injury and during regeneration in vivo are unclear. Our results demonstrate that Gal-1 levels increased during muscle degeneration in vivo, along with changes in its cellular localization, followed by decreased expression during regenerative stages. These results are consistent with previous in vitro studies suggesting a role for Gal-1 in muscle disease (Watt et al. 2004) and provide important insight into Gal-1 expression in vivo during muscle injury and repair.

Previous studies demonstrated that Gal-1 induces skeletal muscle differentiation in human fetal mesenchymal stem cells (Chan et al. 2006) and transdifferentiation of fibroblasts into myoblasts (Goldring, Jones, Sewry, et al. 2002; Goldring, Jones, Thiagarajah, et al. 2002). Furthermore, Gal-1-null mice exhibit impaired muscle formation and reduced regenerative capacity (Watt et al. 2004), suggesting critical roles for Gal-1 in muscle development and repair. Earlier studies demonstrated that Gal-1 remains cytosolic until just prior to fusion, whereupon it is secreted (Nowak et al. 1976; Barondes and Haywood-Reid 1981; Cooper and Barondes 1990; Harrison and Wilson 1992; Poirier et al. 1992; Watt et al. 2004). Myoblasts harvested from Gal-1-null mice exhibit impaired fusion (Watt et al. 2004; Georgiadis et al. 2007). Although these earlier studies suggested that Gal-1 regulation and secretion may be important in muscle development and regeneration, the expression and localization of Gal-1 during degenerative and regenerative processes in vivo remained unknown.

To address whether Gal-1 expression correlated with its putative role in muscle regeneration, we examined Gal-1 localization and expression in two models of muscular dystrophy, the murine mdx and the canine GRMD model (Bulfield et al. 1984; Cooper et al. 1988; Collins and Morgan 2003; Watchko et al. 2002) and also during BaCl2-induced injury in C57BL/6 mice. Gal-1 protein expression increased significantly during degeneration in both animal models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and BaCl2-induced injury, followed by reduced expression during regeneration. These results are consistent with a role of Gal-1 in signaling the regenerative capacity of local cells, such as fibroblast and stem cells to differentiate into muscle tissue and induce myoblast fusion (Goldring, Jones, Sewry, et al. 2002; Goldring, Jones, Thiagarajah, et al. 2002). The increase in Gal-1 expression in C57BL/6 mice induced by BaCl2-induced injury also suggests that increased Gal-1 expression is not limited to degeneration associated solely with dystrophy, but likely represents a common signal that follows muscle injury in general. Importantly, we observed increased levels of Gal-1 appeared to predominately localize in areas adjacent to the cell surface, with specific localization both inside and outside the sarcolemma. Extracellular Gal-1 may directly contribute to muscle regeneration as previous studies demonstrating that the exogenous addition of Gal-1 mediates myoblast fusion and transdifferentiation of fibroblasts (Goldring, Jones, Sewry, et al. 2002; Goldring, Jones, Thiagarajah, et al. 2002). Furthermore, Gal-1 undergoes extracellular secretion just prior to myoblast fusion (Nowak et al. 1976; Barondes and Haywood-Reid 1981; Cooper and Barondes 1990; Harrison and Wilson 1992; Poirier et al. 1992; Watt et al. 2004). Such results suggest that impaired myoblast fusion in vivo in Gal-1 null mice and myoblasts harvested from Gal-1 null mice in vitro (Watt et al. 2004; Georgiadis et al. 2007) may represent compromised signaling events normally initiated by Gal-1 upon extracellular localization during injury. However, unknown functions for Gal-1 within myofibers may also be important during muscle regeneration. Taken together, the results of the present study corroborate previous in vitro studies, strongly suggesting a role for the involvement of Gal-1 in muscle regeneration in vivo.

Increased expression of Gal-1 following muscle injury may not only contribute to muscle regeneration, but might also serve to regulate immune responses generated during tissue injury. Consistent with this possibility, Gal-1 colocalized with infiltrating CD45+ leukocytes. Gal-1 may be important in leukocyte homeostasis and turnover, since Gal-1 induces phosphatidylserine exposure, a membrane phospholipid responsible for signaling the phagocytic removal of neutrophils, during inflammatory resolution (Dias-Baruffi et al. 2003; Karmakar et al. 2005; Stowell et al. 2007). As a result, increased Gal-1 levels may also serve to protect viable tissue surrounding the area of injury in addition to signaling appropriate differentiation signals to initiate muscle regeneration, consistent with previous results (Rabinovich et al. 2000).

Changes in Gal-1 expression following injury and regeneration suggest significant control of Gal-1 expression. Although many studies have examined the effect of Gal-1 on muscle cells and leukocytes, both in vitro and in vivo (Dias-Baruffi et al. 2003; Kami and Senba, 2005; Stowell et al. 2007; Watt et al. 2004), few studies have demonstrated factors or diseases which result in its altered expression or secretion (Watt et al. 2004). Gal-1 expression is thought to increase following inflammatory stimuli, such as induced by TNFα (Baum et al. 1995). Whether continued degeneration results in sustained levels of proinflammatory cytokines that retain elevated Gal-1 levels, or whether regenerating tissue signals tissue to resume normal Gal-1 expression, remains to be determined. Importantly, although many studies have implicated a role for Gal-1 in tissue regeneration and inflammatory resolution (Watt et al. 2004), these results provide one of the first examples of in vivo regulation of Gal-1 expression and localization in response to injury and regeneration.

Muscular dystrophy affects thousands of individuals with high rates of morbidity and mortality yet it is refractory to current treatment modalities (Blake et al. 2002; Emery 2002). Understanding muscle degeneration and regeneration at the molecular level will likely enable the development of new therapeutics aimed at altering the course of the disease. The results of the present study, together with past studies, strongly suggest a key role for Gal-1 in muscle tissue regeneration following injury. Future studies will be directed to identifying the signaling pathways and cognate receptors on cells responsible for mediating Gal-1 induced effects in muscle tissue.

Material and methods

Animals

C57BL/6 wt and mdx mice were obtained from animal facility of the Universidade Fluminense, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. All dogs came from the same colony that was founded from one carrier female donated by Professor Joe N. Kornegay, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA. The genotypes of the wt dog and affected dogs in pedigrees segregating GRMD were confirmed by exon 7-specific genomic polymerase chain reaction followed by Sau96 I digestion and analyzed by restriction fragments length polymorphism as described by other (Bartlett et al. 1996). The animals were housed and used at the Muscular Dystrophy Research Center (AADM/UNAERP) in accordance with the guidelines set by the Institutional Laboratory Animal Care Committee of the University of Ribeirão Preto (processes no. 063/05 and 119/04). We used male mice from 2 to 9 weeks old and dogs from 3 to 12 months old.

Antibodies

An affinity purified rabbit polyclonal anti-Gal-1 antibody was produced in our laboratory against human recombinant Gal-1 (hr-Gal-1). The hr-Gal-1 protein was prepared as described (Dias-Baruffi et al. 2003; Stowell et al. 2004). Anti-Gal-1 was purified by affinity chromatography using an hrGal-1-Sepharose column. Commercial antibodies anti-dystrophin, anti-desmin, and anti-utrophin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); anti-vinculin from Chemicon (Temecula, CA); anti-CD45 (Leukocyte Common Antigen) from Ly-5-BD-Pharmingen (San Jose, CA); goat anti-rabbit-Alexa 488, goat anti-mouse-Alexa 594, and goat anti-rat-Alexa 488 from Invitrogen/Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR); and goat IgG, donkey anti-rabbit-HRP, and donkey anti-goat-HRP from Jackson Immunoresearch (West Groove, PA).

BaCl2-induced lesion

Adult C57BL/6 male mice (7–10 weeks old) were injected with 50 μL of 1.2% barium chloride solution (BaCl2, Carlo Erba, Milan, Italy) in right GA to induce degeneration and subsequent regeneration. The same amount of isotonic saline solution was injected into left GA as control.

Exercise protocol and muscle sampling

Compulsory exercise was done as follows: eight 4-week-old male mice (four wt and four mdx) were submitted to a 20 min running program on treadmill (downhill, three times a week, at 20 cm/s) during 5 weeks (from 4 to 9 weeks old). The mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation. The entire GA and DIA from sedentary or exercised mdx mice were dissected, immediately frozen in liquid N2, and processed for western blot or immunohistochemical assays, as described below. All dogs were anaesthetized intramuscularly with a xylazine–ketamine combination at 1.0 and 10.0 mg/kg, respectively. Biopsies from femoral biceps and DIA sections were excised, immediately frozen in liquid N2 and submitted to each experimental procedure, as described below. Samples of DIA were obtained from dogs whose death was caused by the dystrophy itself (GRMD) or by unknown cause (GRMD or wt dogs).

Immunofluorescence

Briefly, frozen 5 μm tissue sections were blocked in TBS with 50 μg/mL goat IgG, 2% (w/v) BSA, and 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 for 45 min, and then incubated with 10 μg/ mL anti-Gal-1, 10 μg/mL anti-dystrophin or 10 μg/mL anti-vinculin or 10 μg/mL anti-utrophin or anti-CD45 (1:50 dilution) for 1 h. Slides were washed twice for 15 min in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 plus twice in PBS plus 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20. Subsequently, slides were incubated with 5.7 μg/mL goat anti-rabbit-Alexa 488/Alexa594 and/or goat anti-mouse-Alexa 594 or goat anti-rat-Alexa 594 plus 50 ng/mL DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride) for 1 h. Washing procedure was repeated using only PBS plus Tween 20. Slides were mounted in Fluoromount:TBS (2:1) and images were captured using a Nikon DMX 1200 digital camera connected to Nikon Eclipse 800 fluorescence microscopy. Alternatively, images were acquired in a Leica TCS-SP5 confocal microscopy (Mannheim, Germany).

Western blotting and protein quantification

Crude muscle protein extracts were obtained by homogenization of weighted frozen tissue with a sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 2% (w/v) SDS, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 0.10 mM SERVA blue, 0.25 mM EDTA, 30 μM phenol red and 0.9% β-mercaptoethanol) in liquid N2. The samples were incubated for 5 min at 100°C, centrifuged, and loaded in 15% polyacrylamide gels. Nitrocellulose electroblotted membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) were probed separately with 0.25 μg/mL rabbit polyclonal anti-Gal-1 and 1.5 μg/mL goat anti-desmin (used as a constitutive control) for all muscle samples and then incubated with 40 ng/mL of a specific HRP conjugate secondary antibody. As negative control, membranes were incubated for 1 h with anti-Gal-1, which was previously incubated with hr-Gal-1 (50 μg/mL) for 1 h. Bound antibodies were revealed by enhanced chemiluminescence using the ECL kit (Amersham Biosciences). Preparations were performed in parallel for mdx and C57BL/6 control mice and for BaCl2 and NaCl injected C57BL/6. Blots were repeated three times for each experiment and the bands were quantified by densitometric analysis using the ImageJ software. To estimate the levels of Gal-1 (in ng per μg crude protein extract), we generated a standard curve using purified human recombinant Gal-1 in several dilutions blotted to nitrocellulose membranes in triplicate and probed with the anti-Gal-1. Unique 14 kDa bands were quantified by densitometry analysis; standard curves for mouse and dog experiments were generated from these data and used to estimate Gal-1 levels in the respective muscle samples.

Statistical analyses

Significance was assessed by submitting triplicate blot data to the unpaired t-test using GraphPad Prism v.4 software. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Associação de Amigos dos Portadores de Distrofia Muscular, University of Ribeirão Preto and Petrobras. Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo provided fellowships to S.R.O. (05/02464-8) and M.C.C. (05/02452-0) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvime- nto Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) to M.D.B. (480775/04-4).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Maria Célia Jamur and Dr. Constance Oliver for the fluorescence microscope use; Dr. Roy E. Larson and Daniel Roberto Callejon for the confocal microscope use; Vani Maria Alves Corrêa for the excellent assistance with histological processing; Dr. Lucélio Bernardes Couto, Angélica de Souza, and Mildre Loraine Pinto for the great support in the animal facility. We especially thank Mrs. Edna Maria Soatto Pupin, President of Associação de Amigos dos Portadores de Distrofia Muscular (AADM) for support and Marlise Agostinho Bonetti Montes for preparing the anti-Gal-1 antibody.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Anti-Gal-1

rabbit polyclonal anti-galectin-1 antibody

- DIA

diaphragm

- DMD

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

- GA

gastrocnemius

- Gal-1

galectin-1

- GRMD

Golden Retriever Muscular Dystrophy

- hrGal-1

human recombinant Gal-1

- wt

wild type

Conflict of interest statement.

None declared.

References

- Barondes SH, Haywood-Reid PL. Externalization of an endogenous chicken muscle lectin with in vivo development. J Cell Biol. 1981;91:568–572. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.2.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett RJ, Winand NJ, Secore SL, Singer JT, Fletcher S, Wilton S, Bogan DJ, Metcalf-Bogan JR, Bartlett WT, Howell JM, Cooper BJ, Kornegay JN. Mutation segregation and rapid carrier detection of X-linked muscular dystrophy in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1996;57:650–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum LG, Pang M, Perillo NL, Wu T, Delegeane A, Uittenbogaart CH, Fukuda M, Seilhamer JJ. Human thymic epithelial cells express an endogenous lectin, galectin-1, which binds to core 2 O-glycans on thymocytes and T lymphoblastoid cells. J Exp Med. 1995;181:877–887. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DJ, Weir A, Newey SE, Davies KE. Function and genetics of dystrophin and dystrophin-related proteins in muscle. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:29–329. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulfield G, Siller WG, Wight PA, Moore KJ. X chromosome-linked muscular dystrophy (mdx) in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1189–1192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.4.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brussee V, Tardif F, Tremblay JP. Muscle fibers of mdx mice are more vulnerable to exercise than those of normal mice. Neuromuscul Disord. 1997;7:487–492. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(97)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, O’Donoghue K, Gavina M, Torrente Y, Kennea N, Mehmet H, Stewart H, Watt DJ, Morgan JE, Fisk NM. Galectin-1 induces skeletal muscle differentiation in human fetal mesenchymal stem cells and increases muscle regeneration. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1879–1891. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins CA, Morgan JE. Duchenne's muscular dystrophy: Animal models used to investigate pathogenesis and develop therapeutic strategies. Int J Exp Pathol. 2003;84:165–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2003.00354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BJ, Winand NJ, Stedman H, Valentine BA, Hoffman EP, Kunkel LM, Scott MO, Fischbeck KH, Kornegay JN, Avery RJ, et al. The homologue of the Duchenne locus is defective in X-linked muscular dystrophy of dogs. Nature. 1988;334:154–156. doi: 10.1038/334154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DN, Barondes SH. Evidence for export of a muscle lectin from cytosol to extracellular matrix and for a novel secretory mechanism. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:1681–1691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.5.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DN, Massa SM, Barondes SH. Endogenous muscle lectin inhibits myoblast adhesion to laminin. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1437–1448. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.5.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deconinck N, Dan B. Pathophysiology of duchenne muscular dystrophy: Current hypotheses. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Porte S, Morin S, Koenig J. Characteristics of skeletal muscle in mdx mutant mice. Int Rev Cytol. 1999;191:99–148. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca A, Nico B, Liantonio A, Didonna MP, Fraysse B, Pierno S, Burdi R, Mangieri D, Rolland JF, Camerino C, et al. A multidisciplinary evaluation of the effectiveness of cyclosporine A in dystrophic mdx mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:477–489. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62270-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den H, Malinzak DA. Isolation and properties of beta-d-galactoside-specific lectin from chick embryo thigh muscle. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:5444–5448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias-Baruffi M, Zhu H, Cho M, Karmakar S, McEver RP, Cummings RD. Dimeric galectin-1 induces surface exposure of phosphatidylserine and phagocytic recognition of leukocytes without inducing apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41282–41293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306624200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery AE. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet. 2002;359:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraysse B, Liantonio A, Cetrone M, Burdi R, Pierno S, Frigeri A, Pisoni M, Camerino C, De Luca A. The alteration of calcium homeostasis in adult dystrophic mdx muscle fibers is worsened by a chronic exercise in vivo. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;17(2):144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner TK, Podleski TR. Evidence that a membrane bound lectin mediates fusion of L6 myoblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;67:972–978. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(75)90770-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadis V, Stewart HJ, Pollard HJ, Tavsanoglu Y, Prasad R, Horwood J, Deltour L, Goldring K, Poirier F, Lawrence-Watt DJ. Lack of galectin-1 results in defects in myoblast fusion and muscle regeneration. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:1014–1024. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring K, Jones GE, Sewry CA, Watt DJ. The muscle-specific marker desmin is expressed in a proportion of human dermal fibroblasts after their exposure to galectin-1. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12:183–186. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(01)00280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring K, Jones GE, Thiagarajah R, Watt DJ. The effect of galectin-1 on the differentiation of fibroblasts and myoblasts in vitro. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:355–366. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu M, Wang W, Song WK, Cooper DN, Kaufman SJ. Selective modulation of the interaction of alpha 7 beta 1 integrin with fibronectin and laminin by L-14 lectin during skeletal muscle differentiation. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:175–181. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanft LM, Rybakova IN, Patel JR, Rafael-Fortney JA, Ervasti JM. Cytoplasmic gamma-actin contributes to a compensatory remodeling response in dystrophin-deficient muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5385–5390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600980103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison FL, Wilson TJ. The 14 kDa beta-galactoside binding lectin in myoblast and myotube cultures: Localization by confocal microscopy. J Cell Sci. 1992;101:635–646. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101.3.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kami K, Senba E. Galectin-1 is a novel factor that regulates myotube growth in regenerating skeletal muscles. Curr Drug Targets. 2005;6:395–405. doi: 10.2174/1389450054021918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar S, Cummings RD, McEver RP. Contributions of Ca2+ to galectin-1-induced exposure of phosphatidylserine on activated neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28623–28631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law DJ, Allen DL, Tidball JG. Talin, vinculin and DRP (utrophin) concentrations are increased at mdx myotendinous junctions following onset of necrosis. J Cell Sci. 1994;107(Pt 6):1477–1483. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.6.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen JT, Evans DP, Galvan M, Pace KE, Leitenberg D, Bui TN, Baum LG. CD45 modulates galectin-1-induced T cell death: Regulation by expression of core 2 O-glycans. J Immunol. 2001;167:5697–5707. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak TP, Haywood PL, Barondes SH. Developmentally regulated lectin in embryonic chick muscle and a myogenic cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;68:650–657. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)91195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier F, Timmons PM, Chan CT, Guénet JL, Rigby PW. Expression of the L14 lectin during mouse embryogenesis suggests multiple roles during pre- and post-implantation development. Development. 1992;115:143–155. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich GA, Sotomayor CE, Riera CM, Bianco I, Correa SG. Evidence of a role for galectin-1 in acute inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1331–1339. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(200005)30:5<1331::AID-IMMU1331>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley HG, Grounds MD. Cromolyn administration (to block mast cell degranulation) reduces necrosis of dystrophic muscle in mdx mouse. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley HG, De Luca A, Lynch GS, Grounds MD. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Focus on pharmaceutical and nutritional interventions. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:469–477. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell SR, Arthur CM, Mehta P, Slanina KA, Blixt O, Leffler H, Smith DF, Cummings RD. Galectin-1, -2, and -3 exhibit differential recognition of sialylated glycans and blood group antigens. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10109–10123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709545200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell SR, Dias-Baruffi M, Penttilä L, Renkonen O, Nyame AK, Cummings RD. Human galectin-1 recognition of poly-N-acetyllactosamine and chimeric polysaccharides. Glycobiology. 2004;14:157–167. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell SR, Karmakar S, Stowell CJ, Dias-Baruffi M, McEver RP, Cummings RD. Human galectin-1, -2, and -4 induce surface exposure of phosphatidylserine in activated human neutrophils but not in activated T cells. Blood. 2007;109:219–227. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-007153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell SR, Qian Y, Karmakar S, Koyama NS, Dias-Baruffi M, Leffler H, McEver RP, Cummings RD. Differential roles of galectin-1 and galectin-3 in regulating leukocyte viability and cytokine secretion. J Immunol. 2008;180:3091–3102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng BS, Zhao P, Pattison JS, Gordon SE, Granchelli JA, Madsen RW, Folk LC, Hoffman EP, Booth FW. Regenerated mdx mouse skeletal muscle shows differential mRNA expression. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:537–545. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00202.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watchko JF, O’Day TL, Hoffman EP. Functional characteristics of dystrophic skeletal muscle: Insights from animal models. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:407–417. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01242.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt DJ, Jones GE, Goldring K. The involvement of galectin-1 in skeletal muscle determination, differentiation and regeneration. Glycoconj J. 2004;19:615–619. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000014093.23509.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.