Abstract

Objective To develop and test an instrument for assessing a healthcare organization’s ability to mitigate malpractice risk through clinical decision support (CDS).

Materials and Methods Based on a previously collected malpractice data set, we identified common types of CDS and the number and cost of malpractice cases that might have been prevented through this CDS. We then designed clinical vignettes and questions that test an organization’s CDS capabilities through simulation. Seven healthcare organizations completed the simulation.

Results All seven organizations successfully completed the self-assessment. The proportion of potentially preventable indemnity loss for which CDS was available ranged from 16.5% to 73.2%.

Discussion There is a wide range in organizational ability to mitigate malpractice risk through CDS, with many organizations’ electronic health records only being able to prevent a small portion of malpractice events seen in a real-world dataset.

Conclusion The simulation approach to assessing malpractice risk mitigation through CDS was effective. Organizations should consider using malpractice claims experience to facilitate prioritizing CDS development.

Keywords: clinical decision support systems, health information technology, electronic health records

INTRODUCTION

Electronic health records (EHRs), particularly those with effective clinical decision support (CDS) systems, are potentially powerful tools for improving the quality and safety of healthcare.1–5 In addition, CDS systems can also be useful for reducing medical malpractice risk.6,7

To determine the potential role of CDS in preventing malpractice events, we previously analyzed closed malpractice claims from Partners HealthCare, finding that 123 of 477 claims might have been prevented by CDS.7 Although this was roughly one-fourth the number of claim events, in terms of indemnity, those 123 CDS-preventable claims represented nearly 60% of the dollars paid out during the study period, in excess of $40 million.7 Although the prior study yielded valuable information about the relationship between CDS and past malpractice claims at Partners, we did not have a detailed inventory of our own organizations’ CDS capabilities that would have allowed us to understand our current exposure to malpractice risk. Moreover, other organizations inquired about whether their CDS strategy would be sufficient to mitigate malpractice risk, but we were likewise limited in our ability to help these organizations understand their own malpractice risk, owing to the heterogeneity of CDS implementation8–10 and [the] lack of a systematic tool to for assessment.

Although several assessments on CDS adoption have been published previously,11–13 they focused exclusively on basic CDS types and relied on simple attestation (e.g., “Yes, diagnostic CDS is in place in our EHR”) rather than actual system testing. One exception is a Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE)-focused post-deployment safety testing tool developed with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the California Healthcare Foundation, and administered by the Leapfrog Group. This tool walks hospitals through a set of simulated medication orders to assess whether any CDS is provided. Although we consider this methodology strong, the assessment is focused specifically on medication orders for adult inpatients, and does not consider other types of CDS. To close this gap, we decided to develop and evaluate a robust instrument for self-assessment of information system risk and test it at several sites.

METHODS

General Approach

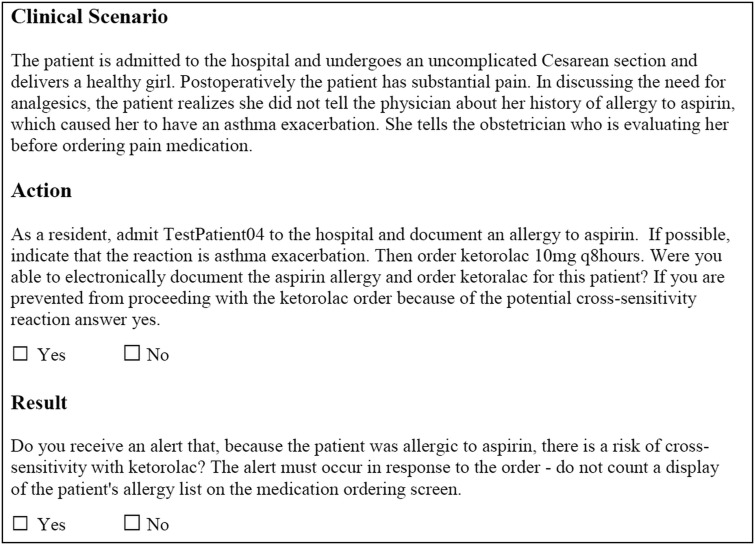

The simplest approach to assessing an organization’s CDS implementation is attestation: asking a user directly whether certain types of CDS are in place at his or her organization. However, we decided not to pursue this approach for two reasons. First, leaders of organizations have, at times, been surprised to find that a particular CDS system they thought was enabled is actually not working as intended.14 Second, in certain cases, a particular CDS system might not be sufficiently advanced to prevent a specific adverse event. For example, nearly all organizations have drug-allergy alerting, but not all have sophisticated checking for cross-sensitivities (e.g., administration of ketorolac to a patient with a documented aspirin allergy). Therefore, we took the approach of simulation rather than attestation whenever possible.

Malpractice Dataset

Partners HealthCare System is an integrated delivery system in Boston, Massachusetts comprising hospitals, a home-care system, and a network of community-based physicians. Most Partners hospitals are insured for professional liability by the Controlled Risk Insurance Company (CRICO). For more than 25 years, CRICO has maintained a database of all information related to each malpractice claim, which we define as a written demand for compensation for medical injury. Each claim file includes a variety of structured and unstructured elements such as a clinical summary, details of the location of the event (inpatient/outpatient), litigation-related documents (narrative statements from healthcare personnel, peer reviews, and depositions), clinical records deemed pertinent to the case’s defense, and information regarding the patient’s pre- and post-event status. Each claim record also contains data on two types of costs associated with the claim: legal expenses in defending the claim (which apply to all claims regardless of the outcome) and indemnity payments, which includes the total compensation paid out to resolve a claim, whether through settlement, trial, or arbitration. For outpatient claims, the allocation to a hospital is assigned based on the primary site of employment of the responsible physician. A claim is classified as closed when it has been dropped, dismissed, paid by settlement, or resolved by verdict.

We reviewed files for all closed malpractice claims (n = 477) from seven CRICO-insured Partners hospitals and their associated outpatient practices with incident dates between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2007 that were asserted by December 31, 2008 (see Table 2). Open claims were not used because the full abstraction of the claim completed by CRICO, including coding and clinical narrative, is not final until the claim is closed.

Table 2:

Test hospital characteristics

| Hospital | Type | EHR System | Bed Size | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barnes-Jewish Hospital | Academic | Vendor | 1315 | St Louis, MO, USA |

| Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital | Community | Self-developed and vendor | 150 | Boston, MA, USA |

| Brigham and Women’s Hospital | Academic | Self-developed | 793 | Boston, MA, USA |

| North Shore Medical Center | Community | Self-developed and vendor | 248 | Lynn, MA, USA |

| Newton Wellesley Hospital | Community | Self-developed and vendor | 313 | Newton, MA, USA |

| Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center | Academic | Vendor | 470 | New York, NY, USA |

| Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center | Academic | Vendor | 744 | Richmond, VA, USA |

CRICO provided secured, de-identified case abstracts for review by the research team. These included data on the disposition of the case, as well as indemnity loss paid (payment made to the claimant), and legal expenses incurred defending the claim. The study was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee.

Our prior study identified 41 types of CDS that might mitigate malpractice risk and the total amount of indemnity dollars paid for claims that might have been prevented by each type of CDS. For example, Partners experienced $4 387 804 indemnity associated with claims related to missed or incomplete referrals that might have been prevented by a referral management component of CDS.

Instrument Development

We developed a self-assessment tool comprised of clinical vignettes and questions to be completed by test-takers in different clinical roles. We considered the malpractice events associated with each CDS type in the malpractice dataset, and then wrote one or more questions to simulate the conditions at the time of the event. For example, to test an EHR’s ability to detect potential cross-sensitivity reactions, a test-taker in a nurse role might be asked to document an aspirin allergy for a test patient, then attempt to order ketorolac and document whether any CDS was presented. As users took the test, we asked them to be liberal in interpreting the types of alerts — we accepted any alert or warning, whether a hard stop or soft stop, interruptive or otherwise. The only guidance we provided was that the alert must be triggered in response to the order, and that they should not count simple display of information. So, for the ketorolac question, simply displaying the aspiring allergy on the medication ordering screen would not suffice; however, any alert or specific information in response to the ketorolac order would satisfy the item. We endeavored to keep the clinical questions in our self-assessment tool as close to the details of the actual event as possible; however, in some cases we modified the details or the time course for simplicity's sake. After developing the initial set of questions, we conducted several rounds of refinement. We also combined the questions into four clinically relevant scenarios, each of which follows a single imaginary patient (Table 1 and Supplementary Appendix 1) through a hospitalization. Grouping the vignettes into broader scenarios enabled the test taker to experience a more realistic assessment of the EHR while reducing the number of test patients that needed to be created.

Table 1:

Sample questions from IS Risk Assessment tool

| Action | Lag | Result | CDS Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Document plan for general anesthesia and/or preoperative evaluation/consent on TestPatient01. | None | During the consent process, are you prompted to document a discussion of the risk of dental damage with general anesthesia? | Template for procedures specific complications |

| As an inpatient nurse, document a high risk of falls for TestPatient01 (Morse score greater or equal to 50 or equivalent on local scale). Document the fall risk in whatever system it is typically documented in, such as a nursing documentation system, a flowsheet or a standalone fall prevention module. Do not enter orders for any protective anti-fall measures. | 1 day | Do you receive an alert that the patient is at high risk of falls and has no precautions ordered? If the system automatically suggests or orders fall precautions at or after the time of fall risk assessment, answer Yes. | Fall module |

| Electronically refer TestPatient01 to dermatology for evaluation of a suspicious lesion, indicating that the patient needs to be seen by dermatology within 7 days. Were you able to electronically refer this patient to dermatology? | 14 days | Did you receive an alert that the dermatology appointment was never made? Any alert – page, email, clinical message, flag or any type of unfulfilled referral queue – would all qualify. | Electronic referral/consult management |

CDS, clinical decision support

Figure 1 shows a sample question. Questions consisted of two parts: an action and a CDS result. For each question, test-takers were asked both whether they could complete the action within their EHR and whether they received the expected CDS result. However, in certain situations, users may not have been able to complete the action — for example, if the clinical vignette required users to enter an electronic referral, but the site does not have an electronic referral system. In this case, the user simply indicates that she was not able to complete the action, and she is not required to document whether a CDS result was received. Additional sample questions are shown in Table 1, and the entire instrument is presented as Supplementary Appendix 1.

Figure 1:

Sample question from the assessment tool.

The self-assessment tool contains two special item types. The first is the time-delayed item. For example, because Partners experienced several malpractice cases due to delayed referrals, we constructed a test item that asked the test taker to “Electronically refer TestPatient01 to dermatology for evaluation of the suspicious lesion. The surgeon indicates that the patient needs to be seen by dermatology within 7 days. Do not make any dermatology appointment.” We do not expect any immediate alert related to this scenario; however, a system with optimally designed referral tracking should alert someone (e.g., the ordering provider or a referral coordinator) that the referral had not been completed after some reasonable grace period. In this situation, we asked the test taker to perform the initial part of the action and then to report back on the result after a specific lag period (14 days).

The second type of special item was the attestation item, which was intended to examine certain EHR features that could not be practically assessed through simulation. For example, one case in the malpractice dataset involved a test result sent from an outside lab being inaccurately transcribed into the EHR. Rather than decision support, an EHR should have universal use of electronic interfaces with outside labs. Because this is difficult to test, we created an attestation question: “Are 100% of outside test results electronically entered (either as structured data or as an image)?” to which the user responds yes or no.

Software Development

In order to disseminate the self-assessment instrument, we created a web-based tool for implementation. Developed using Ruby on Rails, the tool is hosted internally on the Partners network on a secure server protected by Hypertext Transfer Protocol Transport Layer Security encryption. Users are restricted to viewing and updating only data associated with their account. The back end of the tool allows us to develop and track the instrument, including modifications to the CDS types, vignettes, and indemnity amounts, and the front end allows users to complete the assessment. The tool is publicly available at https://isrisk.partners.org.

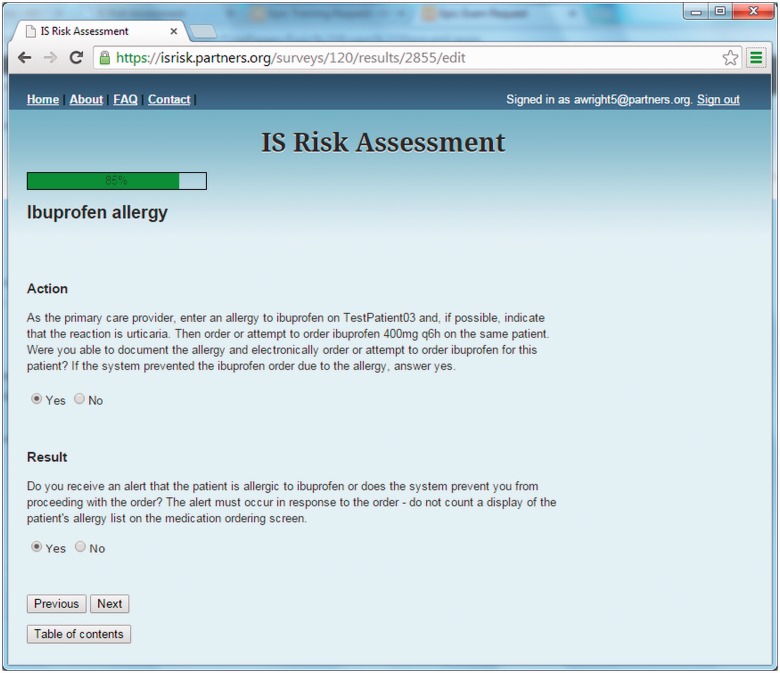

When a test taker accesses the site, she or he receives information about the tool, including frequently asked questions, a description of the four test patients that must be created before taking the test, and the ability to preview the instrument. To take the test, the user creates an account on the site, and is then able to take the assessment. Each user can take the assessment multiple times (e.g., if they want to test more than one EHR, or if they want to test an EHR serially). The test taker is then presented with the first clinical scenario and vignette (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Screenshot of IS risk assessment tool.

Although the questions are presented in order, at any time the user can view the table of contents, skip around the instrument or log out and return later to complete the assessment. Once the assessment is complete, the user receives a report card detailing the results.

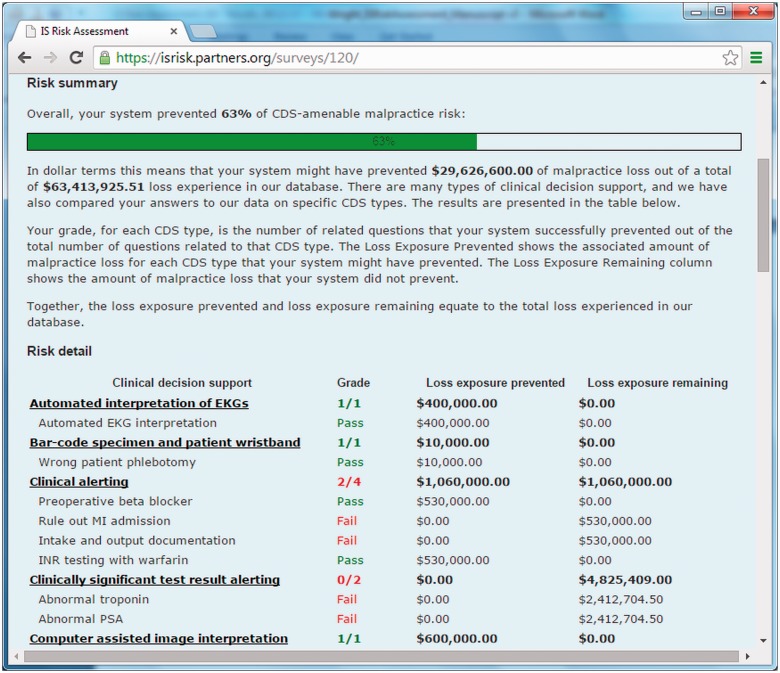

After completing the instrument, the system scores the assessment and a report card is automatically generated. The report card details each assessment item and whether or not the anticipated CDS was present. A sample report card is shown in Figure 3. Each item is grouped according to CDS type (i.e., the two drug-allergy items are presented together), and the associated indemnity amount is displayed for each item based on the amounts calculated in the prior paper.7 All responses are aggregated, and the user is presented with a total “potential indemnity loss prevented” score, which gives an overall idea of the coverage of their CDS relative to the malpractice experience in the malpractice dataset from which the vignettes were derived.

Figure 3.

Sample report card.

Multi-site Evaluation of Assessment Tool

We conducted a multi-site evaluation of the self-assessment instrument between May 2011 and June 2013. Four Partners hospitals (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Newton-Wellesley Hospital, Newton, MA, USA; North Shore Medical Center, Lynn, MA, USA; and Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital, Boston, MA, USA) took the assessment, as well as three non-Partners hospitals (Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, Richmond, VA, USA; Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; and Barnes-Jewish Medical Center, St Louis, MO, USA). The characteristics of each site are shown in Table 2.

The multi-site evaluation was reviewed and approved by the Partners HealthCare Human Subjects Committee. Each participating site received its own report card and agreed that its data could be used and analyzed in aggregate. Each site also agreed that its name could be listed, but not linked to its results.

RESULTS

All seven sites successfully completed the 57 question self-assessment. The number of questions answered affirmatively ranged from 19 to 40, and the proportion of potentially preventable indemnity loss for which CDS was available ranged from 16.5% to 73.2% (Table 3).

Table 3:

Test results by site

| Hospital | Total CDS Questions Answered “Yes” | Potential Malpractice Loss Prevented (% of indemnity dollars) |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital 1 | ██████ 19 | 16.5 |

| Hospital 2 | ██████▌ 21 | 38.0 |

| Hospital 3 | ███████ 23 | 34.1 |

| Hospital 4 | █████████ 27 | 36.1 |

| Hospital 5 | ███████████ 33 | 55.3 |

| Hospital 6 | ████████████ 37 | 44.6 |

| Hospital 7 | █████████████ 40 | 73.2 |

Sorted by number of questions answered “yes”

CDS, clinical decision support.

Certain types of CDS were universally available, and others were not implemented at any of the sites (Table 4). A number of CDS types were present at every site, including drug-allergy checking (both types), automated interpretation of electrocardiograms (EKGs), links between drug ordering and administration, and checks for timely administration of drugs. Some CDS types, such as preprocedure planning for pulmonary artery catheterization, or tracking of consents, were absent from all systems. However, the majority of CDS types were present in some, but not all, systems, highlighting the variability of CDS implementation across the country.

Table 4:

Aggregate results by CDS question

| CDS Type | |

|---|---|

| CDS Question | No. of sites with CDS |

| Automated interpretation of EKG | |

| Automated interpretation of EKG | ███████ 7 |

| Bar-code specimen and patient wristband | |

| Wrong patient phlebotomy | ███ 3 |

| Clinically Significant Test Result Alerting | |

| Abnormal troponin | █ 1 |

| Abnormal prostate specific antigen (PSA) | █ 1 |

| Clinical Alerting | |

| Preoperative beta blocker | ██ 2 |

| Rule out MI admission | ██████ 6 |

| Intake and output documentation | █ 1 |

| Computer assisted image interpretation | |

| Computer assisted image interpretation | ██████ 6 |

| CPOE – cumulative drug checking | |

| Hydromorphone overdose | 0 |

| CPOE – drug-allergy testing | |

| Ibuprofen allergy | ███████ 7 |

| Aspirin allergy | ███████ 7 |

| CPOE – legibility | |

| Electronic medication orders | ██████ 6 |

| CPOE – limit to approved routes | |

| Hydroxyzine route | ██████ 6 |

| CPOE to Electronic Medication Administration Record (eMAR) communication | |

| Cefepime ordering | ███████ 7 |

| Diagnostic decision support | |

| Headache diagnosis | ████ 4 |

| Drug information available for patients | |

| Bactrim information | █████ 5 |

| Drug information available for physicians | |

| Medication reference | ██████ 6 |

| Electronic instrument count documentation | |

| Instrument counts | ███ 3 |

| Electronic referral/consult management | |

| Incomplete referral – A | 0 |

| Preoperative evaluation | ███ 3 |

| CDS Type | |

|---|---|

| CDS Question | No. of sites with CDS |

| Incomplete referral – B | █ 1 |

| Incomplete referral – C | █ 1 |

| Electronic tracking of instruments | |

| Instrument tracking | █████ 5 |

| Electronic transmission of prescription | |

| Electronic prescription transmission | ██████ 6 |

| Electronic Medical Record – collaborative documentation/communication | |

| EHR access | █████ 5 |

| Fall module | |

| High falls risk without orders | ██ 2 |

| Falls nursing assessment | ███ 3 |

| Handoff tool | |

| Admission and provider | ██ 2 |

| Indication based ordering | |

| Mammogram ordering | ███ 3 |

| Knowledge based templates | |

| Peripherally inserted central catheter line length discrepancy | █ 1 |

| Lab interface | |

| Electronic lab result transmission | █████ 5 |

| Link orders with documentation | |

| Restraint documentation | ███████ 7 |

| Medication administration checking - Drug, dose, patient verification | |

| Heparin overdose | ██████ 6 |

| Verapamil administration | ██████ 6 |

| Medication administration checking: alert for overdue medications | |

| Cefepime administration | ███████ 7 |

| Medication reconciliation | |

| Patient transfer | ██ 2 |

| Outpatient medication fill history | ████ 4 |

| Multimedia/language informed consent | |

| Multimedia consent | ███ 3 |

| Online drug reference | |

| New gentamicin order | ██ 2 |

| Online lab reference | |

| Kappa light chains on Serum Protein Electrophoresis | ███ 3 |

| CDS Type | |

|---|---|

| CDS Question | No. of sites with CDS |

| Online procedure education | |

| Swan-Ganz education | ██ 2 |

| Picture archiving and communication system (PACS) – automatic orientation of image on screen | |

| PACS | ███████ 7 |

| Procedure checklist | |

| Central line | ███ 3 |

| Procedure modeling/planning | |

| Swann-Ganz procedure | 0 |

| Screening reminders | |

| PSA screening | 0 |

| Colonoscopy screening | █████ 5 |

| Standardize image reading (checklist/reminder) | |

| Reporting of abdominal computed tomography (CT) | ████ 4 |

| System to enforce pause (timeout) | |

| Anesthesia timeout | ███ 3 |

| System to enforce timely checks | |

| Vital sign documentation | ███ 3 |

| System to enforce timely documentation | |

| Discharge patient | ████ 4 |

| Template describing exact wishes | |

| Birth preference template | ██ 2 |

| Template for procedure specific complication | |

| - Operative consent | 0 |

| Caesarean section consent | 0 |

| Test reconciliation | |

| Unperformed CT | ███ 3 |

| Unperformed complete blood count (CBC) | ██ 2 |

CDS, clinical decision support; EHR, electronic health records.

DISCUSSION

We found that the use of CDS across entities was highly variable and that the most common CDS types did not necessarily correspond to the areas of greatest malpractice risk exposure. For example, while nearly all sites had drug-allergy checking, drug allergies were not a major driver of malpractice risk in the malpractice dataset. There are several potential explanations for this phenomenon. The first is that drug allergies were a major source of loss in the past, but that this had been corrected by widespread use of drug-allergy CDS. Another possible explanation is that drug allergies do not result in much harm, or at least not harm that rises to the level of malpractice claims. This may make sense both because many drug allergies are not severe and can often be reversed or treated, and because a variety of other protections (e.g., nurse and pharmacy checks, allergy bracelets, and patient self-advocacy) also guard against drug allergies. A third explanation is related to the relative ease of drug-allergy checking: most drug and allergy data is documented electronically in coded form, the logic for drug-allergy checks is basic, and the necessary knowledge content (e.g., drug classes and cross-sensitivities) is readily available from several commercial vendors and packaged with many commercial EHRs. We have conducted some informal reviews comparing our data to other Boston hospitals, to a national sample of hospitals which participate in the CRICO Comparative Benchmarking System and to National Practitioner Data Bank Public Use Data File. In general, we have found that the patterns are similar, although this is difficult to substantiate in a granular way since we only have limited data on external claims.

We paid special attention to areas in which malpractice losses were substantial but CDS was infrequently adopted. Management and alerting for clinically significant test abnormalities is one such area: only a single site had complete, closed-loop tracking for abnormal test results. Failure to follow up on abnormal test results, however, is one of the most important and costly issues in the malpractice dataset. Notably, most of the sites had a mechanism to deliver and request acknowledgement of abnormal test results, but did not provide further tracking of abnormal results. Nevertheless, the malpractice data set used includes many cases where an abnormal result was seen by at least one healthcare provider but not followed up due to an error, a miscommunication, or unclear lines of communication. A potential solution to this type of adverse event is closed-loop tracking, in which a test result is automatically followed until there is appropriate clinical follow-up — not just acknowledgement,15,16 although full closed-loop tracking was only present at a single site.

Two other notable “missing” CDS types were diagnostic decision support and tracking of consent. Although diagnosis error is a common cause of malpractice loss, only four of the sites had any form of diagnostic decision support, and most reported little use of it. A number of accurate diagnostic decision support tools have been available for several decades,17,18 but their use has been limited, often owing to challenges in integration with the diagnostic process and workflow.19 Given that diagnostic error is an enduring problem, further research in improving the palatability of diagnostic decision support should be conducted.

Another key area of malpractice loss relates to informed consent, specifically when the patient and the healthcare provider do not share an understanding of the possible results of a procedure or range of complications. Adequate documentation of informed consent — especially including a discussion of potential risks and benefits — is an important mitigating factor in such malpractice events; however, such documentation is often absent from the record. Decision support tools to facilitate the informed consent process, such as multimedia tools and templates for providers to facilitate discussion and documentation of procedure-specific risks and benefits, may be quite useful for facilitating such communication and documentation. They are, however, infrequently used according to our findings.

In addition to our core findings about the use of CDS, we also learned several important lessons during the administration of our assessments. First, because we anticipated that most sites would complete the assessment on their own, we designed the software accordingly. However, most sites actually asked us to facilitate their assessment, either in person or by phone. In addition, we originally assumed that sites would identify a single test taker, such as a Chief Medical Information Officer, who would take the entire self-assessment. We found that, at most sites, no single person was sufficiently knowledgeable to complete the entire assessment. Instead, most sites assembled an interdisciplinary team to take the test, often including a Chief Medical Information Officer, nurse, pharmacist, and someone from the information systems department. This interdisciplinary test-taking strategy was effective. Finally, though several sites initially said they were certain a particular vignette would trigger CDS, they were subsequently quite surprised when it did not, suggesting that even those responsible for CDS at a particular site may not fully know exactly what CDS is enabled and how it is functioning.

Our study has several key strengths, including our use of a simulation method rather than simple attestation; the inclusion of multiple, diverse sites; and the breadth of CDS types considered (most prior studies were surveys and focused only on medication-related CDS). Conversely, it also has important limitations. First, the instrument was derived from an analysis of one health system’s malpractice claim history. Although the Partners Healthcare system is large and diverse, it may not be representative of all care settings. Second, although we had seven test sites, most were fairly large and provided both inpatient and outpatient care, owing to the nature of the instrument. In future work, we plan to expand the instrument to cover settings that provide only inpatient or only outpatient care, and also to conduct a wider evaluation.

The assessment tool is currently available to take online for free. We are working with several hospitals to complete assessments using the tool, and any interested hospital may complete a self-service assessment, free of charge, and receive a complete report card.

CONCLUSION

We developed a novel simulation-based self-assessment tool of CDS capabilities and tested it by evaluating CDS implementation at seven hospitals. We found that a number of key CDS types are not widely used but are associated with significant malpractice loss. We also identified considerable variability among sites in the breadth and depth of CDS coverage.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AW had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. AW and DZ were responsible for study concept and design. SE, FLM, LS, and MW performed acquisition of data. Analysis and interpretation of data were done by AW, FLM, and GZ. AW wrote the manuscript. AW, FLM, MW, SE, LS, AND GZ performed critical revisions for important intellectual content. The study was supervised by AW and GZ.

FUNDING

This work is supported by funding from the Partners-Siemens Research Council.

ETHICS APPROVAL

Ethics approval was provided by the Partners HealthCare Research Committee.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following: David Artz at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; Nathan Kaufman, Janice Kurowski, and Martin Botticelli at North Shore Medical Center; Beth Downie, Theresa Glebus, Michael Zacks, Charles Von Dohrmann, Meghan Ferguson and Laura Einbinder at Newton Wellesley Hospital; Eric Poon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital; Eileen Fainer, Ali Bahadori, Kimberlee Frasso, Joanne Locke, and O’Neil Britton at Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital; Colin Banas at VCU Medical Center; Keith Woeljte, Sumita Markan-Aurora, Nicholas Hampton, Ashley Lanier, Beverly Neulist, Geoffrey Cislo, Pat Mueth, Richard Reichley, Stacey Larkin, Syma Waxman, Penny Candelario, Emily Fondahn, and Tina Herbstreit at Barnes-Jewish Hospital for their assistance is completing the IS Risk Assessment Tool. Medical editor Paul Guttry assisted with revision of the manuscript for clarity. Trang Hickman assisted with the revision of the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available online at http://jamia.oxfordjournals.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Int Med. 2006;144(10):742–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1223–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2005;330(7494):765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lobach D, Sanders GD, Bright TJ, et al. Enabling health care decisionmaking through clinical decision support and knowledge management. Evid Report/Technol Assess. 2012;(203):1–784. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jones SS, Rudin RS, Perry T, Shekelle PG. Health information technology: an updated systematic review with a focus on meaningful use. Ann Int Med. 2014;160(1):48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Quinn MA, Kats AM, Kleinman K, Bates DW, Simon SR. The relationship between electronic health records and malpractice claims. Arch Int Med. 2012;172(15):1187–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zuccotti G, Maloney FL, Feblowitz J, Samal L, Sato L, Wright A. Reducing risk with clinical decision support: a study of closed malpractice claims. Appl Clin Inform. 2014;5(3):746–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wright A, Sittig DF, Ash JS, Sharma S, Pang JE, Middleton B. Clinical decision support capabilities of commercially-available clinical information systems. JAMIA. 2009;16(5):637–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ash JS, Sittig DF, Wright A, et al. Clinical decision support in small community practice settings: a case study. JAMIA. 2011;18(6):879–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ash JS, Sittig DF, Dykstra R, et al. Identifying best practices for clinical decision support and knowledge management in the field. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2010;160(Pt 2):806–810. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Rao SR, et al. Electronic health records in ambulatory care–a national survey of physicians. The N Engl J Med. 2008;359(1):50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Poon EG, Wright A, Simon SR, et al. Relationship between use of electronic health record features and health care quality: results of a statewide survey. Med Care. 2010;48(3):203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hsiao CJ, Hing E. Use and characteristics of electronic health record systems among office-based physician practices: United States, 2001-2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2014(143):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wright A, Maloney FL, Ramoni R, et al. Identifying Clinical Decision Support Failures using Change-point Detection. In: AMIA Annual Symposium; 2014November; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laxmisan A, Sittig DF, Pietz K, Espadas D, Krishnan B, Singh H. Effectiveness of an electronic health record-based intervention to improve follow-up of abnormal pathology results: a retrospective record analysis. Med Care. 2012;50(10):898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maloney FL, Zuccotti G, Samal L, Fiskio J, Wright A. Decision support to ensure proper follow-up of PSA testing. In: AMIA Annual Symposium ; 2012; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berner ES, Webster GD, Shugerman AA, et al. Performance of four computer-based diagnostic systems. The N Engl J Med. 1994;330(25):1792–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller RA. Medical diagnostic decision support systems–past, present, and future: a threaded bibliography and brief commentary. JAMIA. 1994;1(1):8–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miller RA, Masarie FE., Jr The demise of the “Greek Oracle” model for medical diagnostic systems. Methods Inform Med. 1990;29(1):1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.