Abstract

Rationale:

Advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is an aggressive malignancy that generally leads to poor outcomes, with <5% long-term survival at 5 years; however, several researches have shown improvements in the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) on the maintenance therapy after the first-line chemotherapy. we report a case of metastatic NSCLC patient treated with maintenance therapy of gemcitabine with brilliant results.

Patient concerns:

Clinical data and treatment of a 68-year-old man with NSCLC are summarized. The Ethics Committee of People's hospital of Leshan, approved this study.

Diagnosis:

Lung adenocarcinoma metastasized to the mediastinal lymph node, cervical lymph node, and adrenal gland, without epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation.

Interventions:

Continued treatment with gemcitabine alone following the 6 cycles of cisplatin–gemcitabine chemotherapy, prolonging the interval of chemotherapy when he could not tolerate the toxicity of the drug.

Outcomes:

Partial response of the disease for 4.5 years and significant clinical benefit.

Lessons:

This case shows that patients will benefit from the maintenance therapy, and gemcitabine may be a good choice.

Keywords: advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), gemcitabine, long-term clinical response, maintenance treatment

1. Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of death worldwide and remains one of the most commonly diagnosed malignancies in men and the leading cause of death in men and women in China.[1,2] Even though the development of anticancer agents, especially molecular-targeted anti-tumor agents, has prolonged the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in some selected patients,[3] only 18.1% of all patients with lung cancer survived ≥5 years after the diagnosis.[4] In addition, >70% of the patients have advanced disease stages at diagnosis, with a dismal 5-year survival rate of <5%.[5]

Doublet platinum-based chemotherapy is still considered the standard first-line treatment in these patients[6]; however, no final conclusion has been achieved as regards the subsequent therapy for those who successfully responded to the first-line therapy, that is, either second-line treatment or maintenance therapy is administered after the disease progression. Several studies reported a significant improvement in PFS and OS and manageable toxicity with maintenance therapy after the first-line therapy, especially in patients who experienced better therapeutic effects.[7,8] Maintenance strategies for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are generally categorized as either “continuous” or “switch”. Continuous maintenance refers to the use of one or more drugs given as the first-line regimen until progressive disease or limited toxicity, whereas switch maintenance is defined as the administration of a totally different agent from the first-line chemotherapy. Because of its better effects on the quality of life and less toxicity, continuing the non-platinum component of a doublet regimen is referred to as the continuation maintenance in patients who do not have a targetable genetic abnormality such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene rearrangement. Agents that have been tested using this strategy included paclitaxel, gemcitabine, pemetrexed, and bevacizumab.[9,10]

Gemcitabine is an effective drug for the treatment of advanced NSCLC, which has been evaluated in several maintenance trials. The acceptable toxicity profile of gemcitabine makes it a good candidate for prolonged administration.[11–13] Herein, we reported a case of a 68-year-old man with negative EGFR gene who accepted the maintenance therapy of gemcitabine for 4.5 years, and his tumor has been achieved a partial response (PR) (the lung mass achieved an almost complete response [CR]).

2. Case report

A 68-year-old man was admitted to the people's hospital of Leshan (Leshan, Sichuan, China) due to progressive dyspnea for 2 days in August 2011. Upon admission, an enlarged cervical lymph node was found on the right side. An enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed a pulmonary mass in the inferior lobe of the right lung, with mediastinal and bilateral paratracheal enlarged lymph nodes and pericardial and bilateral pleural effusion (Fig. 1). Bronchoscopy was performed for biopsy, but failed. Then, cervical lymph node biopsy confirmed the presence of metastatic adenocarcinoma (Fig. 2). The PET (positron emission tomography)-CT scan demonstrated peripheral lung cancer that metastasized to the mediastinal lymph node, cervical lymph node, and adrenal gland, and results of gene detection confirmed that EGFR mutation did not occur. The patient was treated with gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2, days 1 and 8) and cisplatin (75 mg/m2, days 1) every 3 weeks, for 6 cycles since September 2011, re-examination with enhanced chest CT scan revealed that pulmonary mass and lymph node metastasis achieved a partial response and the adrenal gland achieved a stable disease in March 2012 (Fig. 3). Then, gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2, days 1 and 8) maintenance chemotherapy was administered alone every 28 days for 3 cycles, which resulted in the elimination of the mass in the lung and enlarged lymph nodes and the metastatic site remains the same after 9 months of maintenance until December 2012 (Fig. 4). Unfortunately, the patient developed severe bone marrow suppression (grade 3); therefore, the treatment was changed to gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2, days 1 and 8) alone every 56 days. Subsequently, stable disease was achieved and no myelosuppression was observed anymore; thus, this regimen was continued until the disease progression in Match 2016 (Fig. 5). Consequently, multiple line chemotherapy and targeted therapy were administered eventually, and the patient succumbed to cachexia on February 17, 2018.

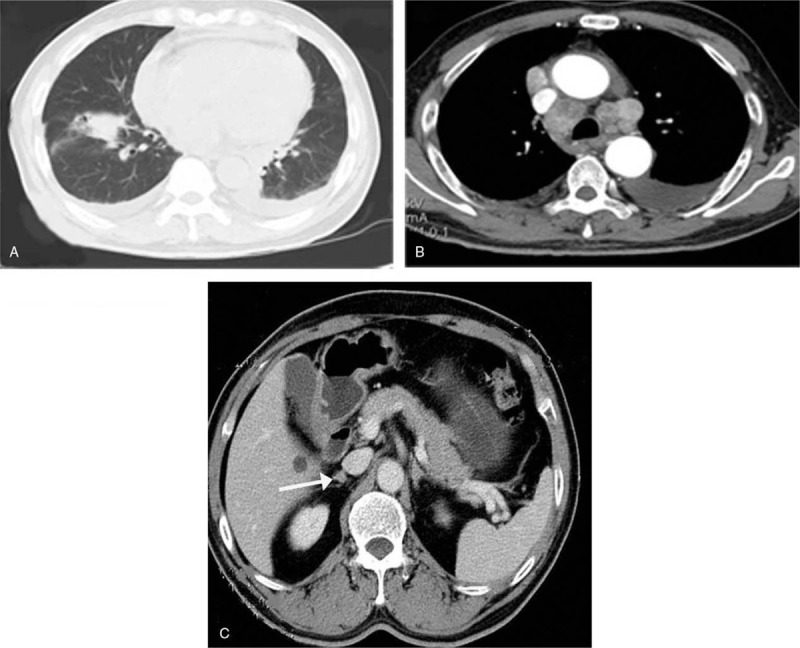

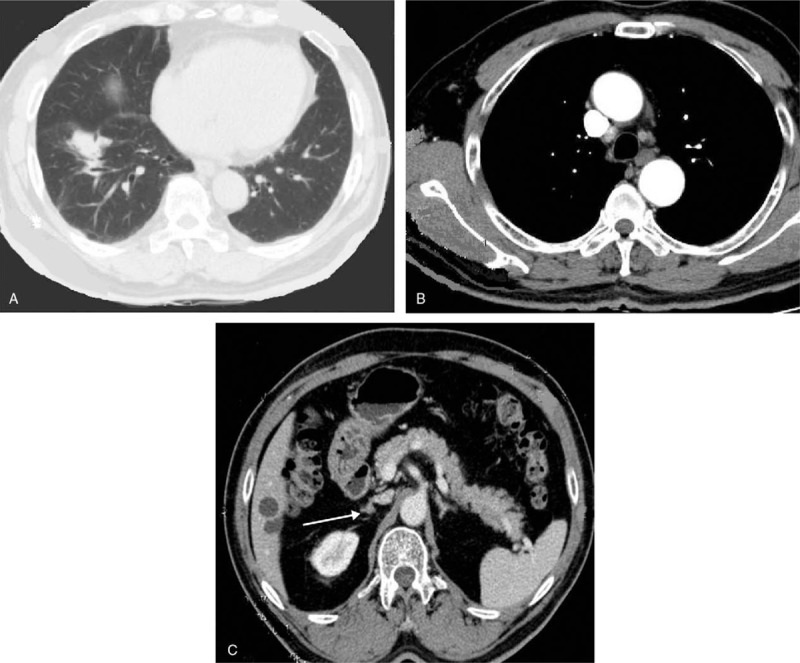

Figure 1.

Enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan evidenced a pulmonary mass in the inferior lobe of right lung (A), with mediastinal and bilateral paratracheal enlarged lymph nodes, pericardial and bilateral pleural effusion (B) and adrenal gland metastases (C) in August 2011.

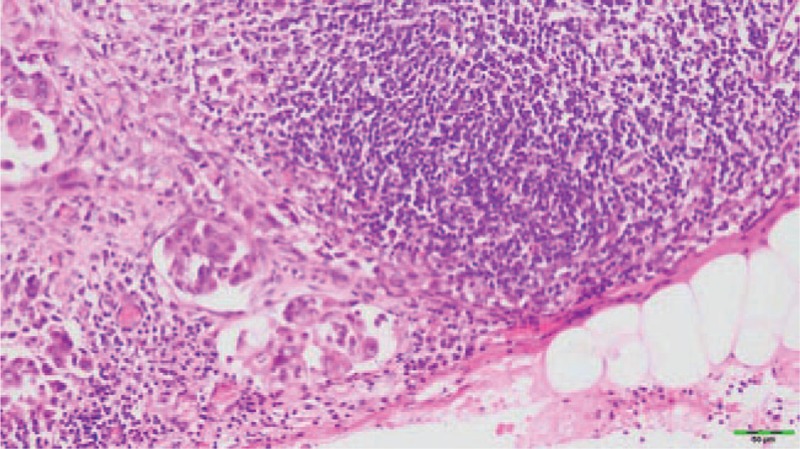

Figure 2.

Histopathology of the cervical lymph node in the right side by biopsy showing an adenocarcinoma (hematoxylin and eosinstain; magnification, x400).

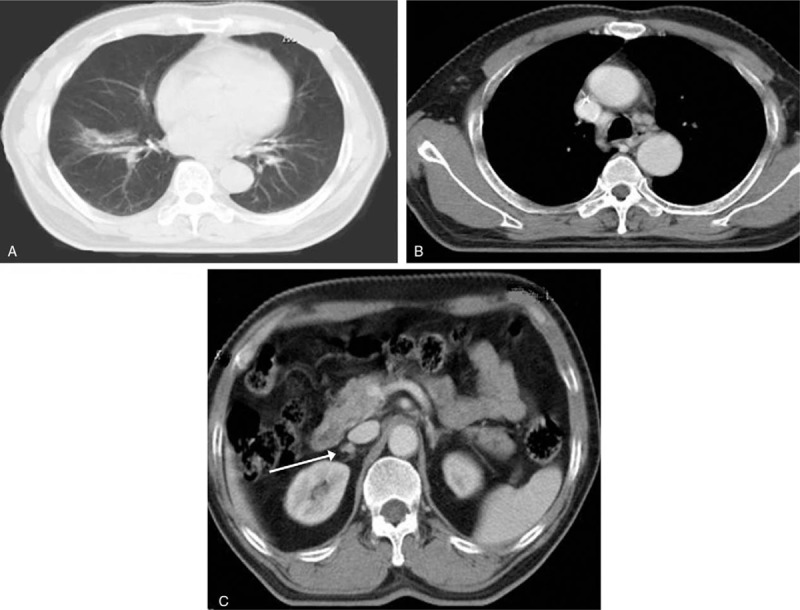

Figure 3.

Re-examination with chest CT scan revealed achieving partial response of pulmonary mass (A) and lymph nodes (B) and stable disease of adrenal gland (C) in March 2012. CT = computed tomography.

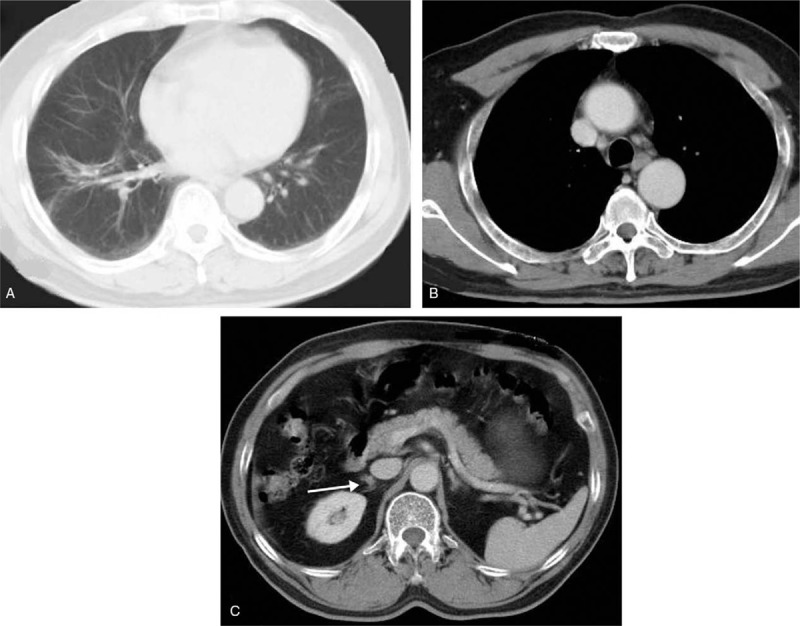

Figure 4.

Re-examination with enhanced CT scan showed the mass of lung (A) and the enlarged lymph nodes (B) was gone and the metastatic site (C) stays the same after 9 months of maintenance in December 2012. CT = computed tomography.

Figure 5.

In March 2016, the disease progress was evaluated by CT, which indicated lung lesions (A) and mediastinal and bilateral paratracheal lymph node (B) enlargement, and the metastatic site (C) stays the same all the time. CT = computed tomography.

3. Discussion

The treatment for advanced NSCLC evolved in the past decade because of the development of anticancer agents, especially the individual molecular-targeted drugs and immunotherapy agents; however, its overall outcome remains poor.[1,4] Maintenance therapy has been intensely investigated in the recent years in order to improve the outcomes in patients with NSCLC, and several studies have demonstrated that it can prolong PFS and OS and improve the quality of life.[7,9] Although many studies provided that maintenance therapy might improve the outcomes, the guidelines in choosing the most suitable regimens in patients with different characteristics in clinical practice remain to be established. In patients with non-squamous NSCLC and negative gene mutation, the main drug for maintenance therapy includes bevacizumab and the non-platinum chemotherapy drugs consist of pemetrexed, paclitaxel, docetaxel, or gemcitabine.

Gemcitabine is a commonly used counterpart for an induction regimen, combined with cisplatin or carboplatin, and its acceptable toxicity profile makes it a good candidate for maintenance therapy, which is a category 2B recommendation as continuation maintenance therapy regardless of the histology in patient without ALK or c-ros oncogene 1 receptor tyrosine kinase rearrangements or sensitizing EGFR mutations in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. A phase 3 randomized trial comparing gemcitabine and erlotinib after the first-line therapy with cisplatin–gemcitabine showed that gemcitabine more significantly improves the PFS than erlotinib (3.8 vs 2.9 months).[12] Both the Central European Cooperative Oncology Group (CECOG) and the Intergroupe Francophone de Cancérologie Thoracique studies have addressed the significant improvement of the PFS tolerated toxicity, and side effects of gemcitabine and compared with best supportive care (BSC) arm.[12,13] In this case, we chose cisplatin–gemcitabine as the first-line chemotherapy, and when he achieved PR, only gemcitabine was continued. Minimal toxicity was observed during the treatment, and finally, he reached 4.5 years of PFS, which was extremely rare and exceeded our expectations.

Although maintenance therapy could improve PFS, no significant differences were observed in OS in some studies.[8,14] Thus, maintenance therapy should be considered as an option in the NCCN guidelines for select patients but not for all patients, because it depends on several factors, such as histologic type, presence of mutations, or gene arrangements and performance status (PS). We suppose that the following 3 points are most important for prolonged administration. First is the PS. Patients with PS of ≥2 are likely too ill to benefit from maintenance therapy. The Brodowicz study (CECOG) showed a statistically significant improved survival with maintenance of gemcitabine in the group with better performance status (KPS of >80), with a trend toward worse survival in the poor performance group (KPS of 70–80).[13] Belani et al showed lower survival with maintenance chemotherapy in patients with poor performance status (PS of ≥2, hazard ratio (HR) of 1.5, P = .009).[14] The present case has a good PS (0–1) during the whole treatment; thus, the therapy could continue all the time. Second, patients’ quality of life and the cost-effectiveness of maintenance therapy should be considered when choosing the maintenance therapy (such as pemetrexed, gemcitabine, docetaxel, paclitaxel, and vinorelbine) because they were commonly associated with hematologic events such as neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia. In our case, he developed grade 3 myelosuppression after 6 months of maintenance chemotherapy every 28 days for days 1 and 8, and this situation was not observed again after changing the interval of treatment to days 1 and 8 for every 56 days. Therefore, prolonged interval of chemotherapy may be a wise policy in patients who cannot tolerate the toxicity and side effects. Last is the response to the initial therapy. In the JMEN study, patients who respond to the initial therapy (CR/PR) had a better survival compared with those who had stable disease.[15] Similarly, Cappuzzo et al demonstrated the same conclusion.[16] Our patient exhibited PR during the whole treatment. Therefore, we concluded that the response is an important factor to be considered because of its sensitivity to the therapy.

4. Conclusion

Patients with non-progressing advanced NSCLC after the first-line therapy may benefit from maintenance therapy, and the classic drug gemcitabine is a good choice. The response to first-line therapy, PS status, and cost-effectiveness of drugs should also be assessed carefully, and prolonging the interval of chemotherapy may be a wise policy for those who cannot tolerate its toxicity and side effects.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Xingxing Lv.

Data curation: Danfei Yu.

Formal analysis: Hong Lu and Hui Chen.

Investigation: Fusheng Gou, Juan Chen, and Danfei Yu

Methodology: Xingxing Lv.

Resources: Fusheng Gou and Juan Liu.

Software: Yuan Shen.

Supervision: Yuan Shen.

Validation: Xuan Zhang.

Writing – original draft: Xingxing Lv and Fusheng Gou.

Writing – review and editing: Xingxing Lv and Yuan Shen.

LV xing XING orcid: 0000-0001-6421-2481.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ALK = anaplastic lymphoma kinase, BSC = best supportive care, CT = computed tomography, EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor, NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer, OS = overall survival, PET = positron emission tomography, PFS = progression-free survival, PS = performance status.

LXX and GFS Contributed to the work equally.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest for this article. Patient's permission was also obtained to publish this article.

References

- [1].Torre LA, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Lung cancer statistics. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016;893:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zhi XY, Zou XN, Hu M, et al. Increased lung cancer mortality rates in the Chinese population from 1973-1975 to 2004-2005: An adverse health effect from exposure to smoking. Cancer 2015;121Suppl 17:3107–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cufer T, Ovcaricek T, O’Brien ME. Systemic therapy of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: major-developments of the last 5-years. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1216–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wang T, Nelson RA, Bogardus A, et al. Five-year lung cancer survival: which advanced stage nonsmall cell lung cancer patients attain long-term survival? Cancer 2010;116:1518–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Stewart LA, Pignon JP. Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. BMJ 1995;311:899–909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gridelli C, de Marinis F, Di Maio M, et al. Maintenance treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of an international expert panel meeting of the Italian association of thoracic oncology. Lung Cancer 2012;76:269–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hashemi-Sadraei N, Pennell NA. Advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): maintenance therapy for all? Curr Treat Options Oncol 2012;13:478–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Coate LE, Shepherd FA. Maintenance therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: evolution, tolerability and outcomes. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2011;3:139–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Patel JD, Socinski MA, Garon EB, et al. PointBreak: a randomized phase III study of pemetrexed plus carboplatin and bevacizumab followed by maintenance pemetrexed and bevacizumab versus paclitaxel plus carboplatin and bevacizumab followed by maintenance bevacizumab in patients with stage IIIB or IV nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 2013;31:4349–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2002;346:92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Perol M, Chouaid C, Perol D, et al. Randomized, phase III study of gemcitabine or erlotinib maintenance therapy versus observation, with predefined second-line treatment, after cisplatin-gemcitabine induction chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 2012;30:3516–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Brodowicz T, Krzakowski M, Zwitter M, et al. Cisplatin and gemcitabine first-line chemotherapy followed by maintenance gemcitabine or best supportive care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase III trial. Lung Cancer 2006;52:155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Belani CP, Waterhouse DM, Ghazal H, et al. Phase III study of maintenance gemcitabine (G) and best supportive care (BSC) versus BSC, following standard combination therapy with gemcitabine-carboplatin (G-Cb) for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Asco Meeting 1982;1043. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ciuleanu T, Brodowicz T, Zielinski C, et al. Maintenance pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care for non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet 2009;374:1432–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, et al. Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:500–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]