Abstract

Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (TEI) is the inheritance of epigenetic information for two or more generations. In most cases, TEI is limited to a small number of generations (two to three). The short-term nature of TEI could be set by innate biochemical limitations to TEI or by genetically encoded systems that actively limit TEI. In Caenorhabditis elegans, double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-mediated gene silencing [RNAi (RNA interference)] can be inherited (termed RNAi inheritance or RNA-directed TEI). To identify systems that might actively limit RNA-directed TEI, we conducted a forward genetic screen for factors whose mutation enhanced RNAi inheritance. This screen identified the gene heritable enhancer of RNAi (heri-1), whose mutation causes RNAi inheritance to last longer (> 20 generations) than normal. heri-1 encodes a protein with a chromodomain, and a kinase homology domain that is expressed in germ cells and localizes to nuclei. In C. elegans, a nuclear branch of the RNAi pathway [termed the nuclear RNAi or NRDE (nuclear RNA defective) pathway] promotes RNAi inheritance. We find that heri-1(−) animals have defects in spermatogenesis that are suppressible by mutations in the nuclear RNAi Argonaute (Ago) HRDE-1, suggesting that HERI-1 might normally act in sperm progenitor cells to limit nuclear RNAi and/or RNAi inheritance. Consistent with this idea, we find that the NRDE nuclear RNAi pathway is hyperresponsive to experimental RNAi treatments in heri-1 mutant animals. Interestingly, HERI-1 binds to genes targeted by RNAi, suggesting that HERI-1 may have a direct role in limiting nuclear RNAi and, therefore, RNAi inheritance. Finally, the recruitment of HERI-1 to chromatin depends upon the same factors that drive cotranscriptional gene silencing, suggesting that the generational perdurance of RNAi inheritance in C. elegans may be set by competing pro- and antisilencing outputs of the nuclear RNAi machinery.

Keywords: transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, RNAi, chromatin, small RNAs

THE inheritance of epigenetic information for two or more generations is referred to as transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (TEI) (Heard and Martienssen 2014). Many examples of TEI have now been documented including, but not limited to, paramutation in plants (Arteaga-Vazquez and Chandler 2010), protein-based inheritance in yeast (Shorter and Lindquist 2005), double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-mediated gene silencing [RNA interference (RNAi)] in Caenorhabditis elegans (Vastenhouw et al. 2006; Ashe et al. 2012; Buckley et al. 2012), and the inheritance of acquired traits in mice (Carone et al. 2010; Walker and Gore 2011; Radford et al. 2012; Castel and Martienssen 2013; Padmanabhan et al. 2013; Somer and Thummel 2014; Holoch and Moazed 2015; Martienssen and Moazed 2015; Rankin 2015). In many cases, TEI is limited to a small number of generations (e.g., two to three) (D’Urso and Brickner 2014; Heard and Martienssen 2014). In other cases, such as piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNA)-mediated gene silencing in C. elegans and paramutation in plants, TEI can be long-lasting (> 10 generations). Molecular mechanisms that set the generational duration of TEI are largely a mystery.

Recently, small noncoding RNAs have emerged as important mediators of epigenetic inheritance in eukaryotes. For example, in plants, the RNA-dependent RNA Polymerase (RdRP) mop1 produces small interfering (si)RNAs thought to mediate paramutation (Alleman et al. 2006). In the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, siRNAs help direct and maintain stable, and in some cases heritable, heterochromatic states at pericentromeres (Volpe et al. 2002; Martienssen et al. 2005; Ragunathan et al. 2015). In Drosophila, maternally inherited piRNAs direct heritable silencing of transposable elements (Le Thomas et al. 2014). Finally, in mice, the effects of stress and metabolic disease are reported to pass from parent to progeny, and microRNAs and short tRNA fragments have been implicated in mediating this inheritance (Carone et al. 2010; Gapp et al. 2014; Sharma et al. 2016). Thus, small regulatory RNAs are good candidates for being the informational vectors of TEI in eukaryotes (termed RNA-directed TEI). Small noncoding RNAs are also linked to TEI in C. elegans. For instance, piRNAs can trigger transgenerational gene silencing via a process termed RNA-induced epigenetic silencing (Ashe et al. 2012; Shirayama et al. 2012). Additionally, dsRNA-mediated gene silencing (RNAi) is heritable in C. elegans; the progeny of animals treated with dsRNAs retain the ability to silence RNAi-targeted genes for many generations, even after the removal of dsRNA triggers (termed RNAi inheritance) (Vastenhouw et al. 2006; Alcazar et al. 2008). During RNAi inheritance in C. elegans, dsRNAs are processed by Dicer into “primary” siRNAs, which are bound by Argonaute (AGO) proteins to regulate complementary cellular RNAs (Meister 2013). AGO-bound primary siRNAs recruit, by an unknown mechanism, RdRPs to homologous mRNA templates to produce amplified pools of “secondary siRNAs” (Sijen et al. 2001). Repeated RdRP-based siRNA amplification in germ cells each generation is likely responsible for driving RNAi inheritance in C. elegans (Ashe et al. 2012; Buckley et al. 2012; Sapetschnig et al. 2015).

Forward genetic screens have identified factors that are required for RNAi inheritance in C. elegans (Ashe et al. 2012; Buckley et al. 2012; Spracklin et al. 2017; Wan et al. 2018). The factors fall into two general categories. The first category includes factors that localize to cytoplasmic liquid-like condensates such as the P granule, the Z granule, or Mutator foci. These factors likely promote RNAi inheritance by acting with RdRPs to amplify siRNA populations each generation (Spracklin et al. 2017; Wan et al. 2018). The second category of factors are members of a nucleus-specific branch of the RNAi pathway [the nuclear RNAi or NRDE (nuclear RNA defective) pathway] (Ashe et al. 2012; Buckley et al. 2012; Shirayama et al. 2012; Spracklin et al. 2017; Wan et al. 2018). According to current models of nuclear RNAi, AGOs bind and escort siRNAs to nuclei, where these ribonucleoprotein complexes locate RNA Polymerase II (RNAP II)-dependent nascent transcripts based on complementarity to trigger cotranscriptional gene silencing (termed nuclear RNAi) (Guang et al. 2008, 2010; Buckley et al. 2012). HRDE-1 and NRDE-3 are two tissue-specific nuclear AGOs that drive nuclear RNAi in germ cells and somatic cells, respectively (Guang et al. 2008; Ashe et al. 2012; Buckley et al. 2012; Shirayama et al. 2012). The nuclear AGOs recruit downstream nuclear RNAi effectors (NRDE-1/2/4) to genomic sites of RNAi to direct histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) (e.g., H3K9me3 and H3K27me3), as well as inhibition of RNAP II during the elongation step of transcription via an unknown mechanism (Guang et al. 2008, 2010; Burkhart et al. 2011; Buckley et al. 2012; Mao et al. 2015). While it is not yet clear why nuclear RNAi is needed for RNAi inheritance, it is known that nuclear RNAi is needed for transgenerational siRNA expression, suggesting that cotranscriptional gene silencing and cytoplasmic siRNA amplification systems may be connected in some way.

If RdRP enzymes can amplify small RNA populations each generation during RNAi inheritance, then why does RNAi inheritance not last forever? There could be fundamental biochemical limitations that prevent RNAi inheritance from lasting forever, or C. elegans might possess systems that actively prevent long-term inheritance. Recently, loss-of-function mutations in met-2, which is one of two C. elegans H3K9 methyltransferases responsible for depositing the majority of H3K9me2 found in C. elegans, were shown to cause RNA-directed TEI to last longer than normal (Andersen and Horvitz 2007; Checchi and Engebrecht 2011; Towbin et al. 2012; Lev et al. 2017). The reasons why loss of MET-2 enhances RNAi inheritance are not known, but may involve global alterations in gene expression that indirectly promote RNAi inheritance (Lev et al. 2017). To further our understanding of why RNAi inheritance does not last forever, we conducted a forward genetic screen to identify additional factors that limit the duration of RNAi inheritance. Our screen identified the gene-heritable enhancer of RNAi 1 (heri-1). We find that HERI-1 inhibits nuclear RNAi-based cotranscriptional gene silencing and that this ability is likely the reason why loss of HERI-1 promotes RNAi inheritance. Interestingly, HERI-1 is physically recruited to genes undergoing nuclear RNAi, suggesting that HERI-1 may be a direct and dedicated regulator of nuclear RNAi, and therefore TEI. Surprisingly, the recruitment of this negative regulator of nuclear RNAi to genes is itself dependent upon nuclear RNAi. To explain these results, we propose that nuclear RNAi has both pro- and antisilencing functions, and that the generational perdurance of RNAi inheritance is set by the relative contributions of these two opposing outputs.

Materials and Methods

Strains

For a complete list of strains used in this study, see Supplemental Material, Table S1. All strains were maintained using standard laboratory conditions.

heri screen

Larval stage 4 (L4) worms carrying both the oma-1(zu405) allele and the pie-1::gfp::h2b transgene were mutagenized with ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) at a concentration of 47 mM for 4 hr at room temperature. Control worms were not exposed to EMS. Mutagenized and control worms were washed 3× with M9 buffer, and allowed to recover for 2 hr at 20° on NGM plates seeded with OP50. F2 progeny of mutagenized and control worms were isolated by hypochlorite treatment, and exposed to oma-1 and gfp RNAi simultaneously on 10-cm RNAi plates at 20°. In total, ∼90,000 mutagenized genomes were screened in 74 independent pools. In the following generation, embryos were isolated with hypochlorite treatment and fed OP50 at 20°. We repeated this process until the control worms failed to inherit oma-1 and gfp silencing (F7). In the F9, we isolated mutants that continued to silence gfp and oma-1. Five generations later, lines that continued to silence reporter genes were kept for further study. To identify candidate heri genes, we used whole-genome sequencing coupled with the bioinformatics tool CloudMap as described in Minevich et al. (2012). In short, genomic DNA was purified from control and mutant strains. Next-generation sequencing libraries were prepared and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq platform. Each genome was sequenced using paired-end sequencing at ∼20× coverage. CloudMap software was used to identify, map, and compare SNP’s between heri mutant strains. Genes that contained three (or greater) unique SNPs were kept as potential heri genes.

RNAi inheritance assays

For gfp inheritance assays: embryos were collected by hypochlorite treatment and placed on either control (HTT115) or gfp RNAi-expressing bacteria at 20°. The F1 embryos were collected again by hypochlorite treatment and fed OP50. When animals reached gravid adult stage, they were scored for germline gfp expression in groups of 50 worms per biological replicate. For Figure 2, C and D, this process was repeated for 10 and 23 generations, respectively. For oma-1 inheritance assays in Figure 1B, embryos were collected by hypochlorite treatment, and placed in either control (HT115) or oma-1 RNAi-expressing bacteria at 20°. The F1 embryos were collected again by hypochlorite treatment and fed OP50. For each biological replicate and for each generation, we singled out six individuals at the L4 stage of development, and 3 days later we counted the number of hatched embryos as well as arrested embryos. The percent viability (oma-1 RNAi inheritance) of each strain was calculated as the number of embryos that hatched within 24 hr over the total number of laid eggs.

Figure 2.

HERI-1 limits transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. (A) Diagram of HERI-1 domain structure. heri-1 alleles identified in our genetic screen and the heri-1(gk961392) deletion allele used in this study are indicated. Asterisk represents premature stop codon. (B) RNAi inheritance assay (see Materials and Methods) showing percent embryonic viability [oma-1(zu405ts) silencing] over generations after oma-1 RNAi feeding in our starting strain (control, YY565), and heri-1 mutants that were identified in the Heri screen and that had been “reset” for reporter gene expression (see Figure 1). Error bars represent SD of the mean. (C) gfp inheritance assay showing the percentage of animals of the indicated genotypes showing gfp silencing in control and reset heri-1 strains over generations after gfp RNAi exposure. (D) Representative images of oocytes in wild-type and heri-1(gk961392) animals that harbor the pie-1::h2b::gfp transgene during the gfp RNAi inheritance assay. Generations after gfp RNAi are indicated. RNAi, RNA interference.

Figure 1.

A genetic screen to identify heritable enhancers of RNAi (heri) genes. pie-1::h2b::gfp and oma-1(zu405ts) can be silenced heritably by RNAi (Vastenhouw et al. 2006; Alcazar et al. 2008). We treated pie-1::h2b::gfp;oma-1(zu405ts) animals with the mutagen EMS. Control animals were left untreated. After two generations, animals were fed bacteria expressing double-stranded RNA targeting gfp and oma-1 simultaneously. Embryos from these animals were isolated and shifted to a non-RNAi (OP50) food source and grown at 20°, which is the nonpermissive temperature for oma-1 (zu405ts). Embryos were isolated for an additional five generations until control animals stopped inheriting gfp and oma-1(zu405ts) silencing (gfp ON and embryonic arrest, ∼F7). Mutagenized pools were allowed to grow for two more generations and potential Heri strains (animals were gfp OFF and alive, indicating that pie-1::h2b::gfp and oma-1(zu405ts) were still being silenced) were singled. After five additional generations, those populations still inheriting gene silencing were kept for further study. heri genes were identified by a combination of whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis (see Materials and Methods and Figure S1). Rare animals within these populations had lost gene silencing at pie-1::h2b::gfp and oma-1(zu405ts). These animals were isolated to establish mutant lines that expressed reporter genes (termed “reset”). EMS, ethyl methanesulfate; RNAi, RNA interference; RT, room temperature.

Construction of HERI-1-tagged strains using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

For construction of the C-terminal heri-1::3xflag strain, we used the Co-CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) strategy described in Arribere et al. (2014). In short, candidate guide RNAs (gRNAs) were calculated using the CRIPSR design tool at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (crispr.mit.edu). We chose the gRNA sequence 5′-TCATGCGAAACGAGAGAAAG-3′ because its protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence of GTGG is located four nucleotides upstream of heri-1’s termination codon, and it had low off-target effect predictions. As a repair template, we used a single-stranded DNA oligo [4 nM ultramer HPLC purified from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT)], which contained 50 bp of homology on each side of heri-1’s termination codon, and it had the PAM sequence mutated to GTTG to prevent repeated Cas9 cutting. Germlines of gravid hermaphrodites were injected with the following injection mix: gRNA (20 ng/μl), repair template (20 ng/μl), and Co-CRISPR markers pDD162 (50 ng/μl) (#47549; Addgene), unc-58 gRNA (20 ng/μl), and AF-JA-76 (20 ng/μl) all in 1× taq buffer (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). Uncoordinated (Unc) progeny of injected worms were singled, allowed to self-fertilize, lay progeny, and then were genotyped for the presence of the 3xflag insertion at the 3′–end of heri-1. For the construction of the C-terminal heri-1::gfp::3xflag strain and the heri-1::chromomutant::gfp::3xflag, we followed the CRISPR/Cas9 homologous recombination protocol described in Dickinson et al. (2015). Details of this approach can be found at http://wormcas9hr.weebly.com/. Repair template had ∼500 bp of homology to heri-1 and contained a self-excising cassette (SEC) with three features: a hygromycin resistance gene, a Roller (Rol) marker gene, and a heat shock-inducible Cre recombinase gene. The SEC is flanked by LoxP sites. Gravid hermaphrodites were injected with an injection mix containing the following: 50 ng/μl of pDD162 plasmid containing the Cas9 and sgRNA (#47549; Addgene), 10 ng/μl of repair template, 10 ng/μl pGH8 (Prab-3::mCherry neuronal co-injection marker; #19359; Addgene), 5 ng/μl pCFJ104 (Pmyo-3::mCherry body wall muscle co-injection marker; #19328; Addgene), and 2.5 ng/μl pCFJ90 (Pmyo-2::mCherry pharyngeal co-injection marker; #19327; Addgene). Injected worms (three per plate) were incubated at 25° for 2–3 days. Then, hygromycin was added directly to the plates at a concentration of 250 μg/ml. Plates were incubated at 25° for 4 days. Animals that were Hygro-resistant, Rol, and lacked the red fluorescent markers were isolated. To excise SEC, larval stage one (L1) animals were heat-shocked at 34° for 4–5 hr and shifted to 20° for 3–5 days. Non-Rol animals were isolated and genotyped by PCR and Sanger sequencing for the gfp::3xflag insertion.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and qPCR

We isolated embryos by hypochlorite treatment and fed larval animals HT115 bacteria expressing oma-1 dsRNA. The following generation, embryos were again collected by hypochlorite treatment and were fed OP50 (non-RNAi bacteria). Gravid hermaphrodites were collected and ∼100 μl pellet of packed worms were washed 2× with 1 ml of M9 buffer, and then flash frozen on liquid nitrogen in a 1.5-ml tube. The pellet was cross-linked by incubation in 1 ml of M9 buffer with 2% formaldehyde, and allowed to rotate for 30 min. The cross-linking reaction was quenched by addition of 54 μl of 2.5 M glycine and samples were then rotated for an additional 5 min. Animals were then washed 2× with 3 ml of M9 buffer and resuspended in 0.5 ml of FA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, and 150 mM NaCl) supplemented with complete Mini protease inhibitors (Roche). Animals were sonicated in a Qsonica Q800R sonicator for 25 min with a cycle of 30 sec on, 30 sec off, and 70% output. Insoluble debris was cleared by a quick spin in a microcentrifuge for 2 min at 5000 rpm at 4°. Extracts were transferred to new tubes and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°. Protein concentrations were calculated by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of protein extracts were precleared using 15 μl of a 50:50 slurry of unblocked protein A or G agarose beads (Millipore, Bedford, MA) in FA lysis buffer for 15 min at 4°, while rotating. Extract/bead mixtures were centrifuged for 30 sec at 3000 rpm and supernatants were transferred to new tubes. For H3K9me3 chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), we used 2 μg of anti-H3K9me3 antibody (07-523; Millipore) and for HERI-1::3xFLAG ChIP we used 3 μg of M2 anti-flag antibody (F1804; Sigma [Sigma Chemical], St. Louis, MO). Antibodies were added and incubated overnight at 4°, while rotating. The following day, 20 μl of protein A (for H3K9me3) and protein G (for Flag) were added to the extracts and allowed to bind for 2 hr at 4°, while rotating. Beads were washed twice with FA lysis buffer, twice with FA lysis buffer + 500 mM NaCl (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, and 500 mM NaCl), once with LiCl buffer (0.25 M LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0), and twice with TE buffer (1 mM EDTA and 10 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0). All washes were performed in 1-ml volumes with 1 min rotation at room temperature, and beads were concentrated by centrifugation for 30 sec at 3000 rpm. Immunoprecipitated chromatin was eluted by incubating beads/ChIPs in 500 μl of 0.1 M sodium carbonate and 1% SDS for 30 min, while rotating at room temperature. Beads were concentrated by centrifugation for 30 sec at 3000 rpm, and the supernatant was collected and transferred to a new tube. To reverse cross-linking, each sample received 30 μl of 5 M NaCl and was incubated at 65° overnight. The following day, ChIP DNA was purified using a PCR cleanup kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and concentrated into 35 μl of water. Enrichment of immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified using the Bio-Rad 2× SYBR Green Master mix, with 2 μl of ChIP DNA per reaction and primers at a final concentration of 250 nM. For a list of primer sequences, see Table S2.

Stacked oocyte scoring and rescue

heri-1 mutant or control animals were crossed to N2 males, and maintained as heterozygous for one to two generations. Homozygous heri-1 mutant animals were isolated and stacked oocytes were quantified in multiple siblings the next generation. This strategy was adopted to minimize the chance that transgenerational epigenetic effects could accrue in heri-1 lines prior to analysis. To score stacked oocyte defects, L4 animals were placed in OP50 food at 20° for 24 hr, then placed in M9 buffer with 0.1% sodium azide and mounted onto 2% agarose pads. For each biological replicate, 50 worms were scored. To ask if mating with wild-type males could rescue stacked oocyte defects, we singled L4 stage heri-1(−); pie-1::gfp::h2b animals and allowed these animals grow at 20° for 24 hr. Animals with stacked oocytes in both gonad arms were identified with a dissecting microscope and split into two groups. Group #1 worms were not crossed to wild-type males (no cross). Group #2 worms were mated with three wild-type males (cross). Approximately 48-hr later, males were removed and animals were allowed to grow at 20° for another 24 hr. The number of progeny for each worm in each group was counted.

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

For HERI-1::3xFLAG imaging, gonads were dissected and fixed as follows: ∼20 gravid hermaphrodites where picked onto a 20 μl drop of M9 in a coverslip. Gonads were dissected using a 25G ⅝ needle by cutting worms in half near the vulva. The coverslip containing dissected gonads was placed on a Gold Color Frost Plus slide (9951GLPLUS; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and immediately placed on a block of dry ice for 10 min. Using a razor blade, the coverslip was popped off the sample then quickly placed in −20° methanol for 10 min. The slide was allowed to air dry for 1–2 min at room temperature. Excess methanol was removed with a kimwipe. Samples were blocked with 500 μl of 0.5% BSA in 1× PBS at room temperature. The M2 anti-flag antibody (F1804; Sigma) was diluted 1:100 in 0.5% BSA in 1× PBS and 50 μl was added to the sample. Primary incubation was overnight at 4° in a humidified chamber. Slides were then washed 4× with 150 μl of 0.5% BSA in 1× PBS with 6–7 min for each wash. An Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (A10667; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was diluted 1:250 in 0.5% BSA in 1× PBS and 50 μl were added to the sample. Secondary incubation was for 2 hr at room temperature. Slides were again washed 4× with 150 μl of 0.5% BSA in 1× PBS with 6–7 min each wash. After the final wash, 15 μl of Vectashield with DAPI (H-1200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was added to the slide and a new coverslip was carefully placed over the sample. Most images were taken using a wide-field Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1 microscope ([Carl Zeiss], Thornwood, NY) using a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.40 Oil DIC M27 objective and an ORCA-Flash 4.0 CMOS camera. Images in Figure 3 and Figure S5 were generated using a Nikon (Garden City, NY) Eclipse Ti microscope equipped with a W1 Yokogawa Spinning disk, with a 50 μm pinhole disk and an Andor Zyla 4.2 Plus sCMOS monochrome camera with a 60×/1.4 Plan Apo Oil objective.

Figure 3.

HERI-1 is expressed in germ cell nuclei. (A) Fluorescent micrographs of the mitotic and transition zones of an adult germline from an animal expressing HERI-1::GFP::3XFLAG and mCHERRY::H2B. Note that HERI-1::GFP::3XFLAG does not colocalize with chromatin in dividing cells (arrows). Distal tip cell is to the left of image. One nuclei (square box) is magnified in panels shown to the right. (B) Micrograph of a larval stage one (L1) and a larval stage two (L2) animal. HERI-1::GFP::3XFLAG is expressed in Z2 and Z3 (arrows) in L1, and in the developing germline of L2 animals (dotted line). In these animals, no HERI-1::GFP signal was observed in the soma. Note that the nongermline fluorescence signal is due to autofluorescence, which is also present in wild-type animals. HERI-1::GFP is expressed throughout the remainder of germline development and no GFP fluorescence could be observed in somatic cells during this time.

Data availability

Strains, plasmids, and whole-genome sequencing data are available upon request. The authors affirm that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions of the article are present within the article, figures, and tables. Supplemental data has been uploaded to Figshare, including WGS sequencing data for each of the four heri-1 alleles identified by WGS. Table S1 contains the strains used in this study. The Supplemental Figures document contains Figures S1–S10. Supplemental material available at Figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.7229294.

Results

A genetic screen identifies heritable enhancers of RNAi (heri) genes

We conducted a genetic screen to identify factors that limit the generational perdurance of RNAi inheritance in C. elegans (Figure 1). gfp RNAi silences a gfp::h2b reporter transgene for six to nine generations (Vastenhouw et al. 2006; Buckley et al. 2012). oma-1(zu405ts) is a temperature-sensitive (ts) gain-of-function (gf) lethal allele of oma-1 (Lin 2003). oma-1 RNAi silences oma-1(gf) and, therefore, OMA-1(GF)-mediated lethality for four to seven generations (Alcazar et al. 2008; Buckley et al. 2012). We EMS mutagenized gfp::h2b; oma-1(gf) animals and, two generations after mutagenesis, exposed animals to gfp and oma-1 dsRNAs. In parallel, we propagated nonmutagenized control gfp::h2b; oma-1(gf) animals similarly treated with gfp and oma-1 dsRNAs. Animals were propagated in the absence of further RNAi until nonmutagenized control animals failed to inherit oma-1 or gfp silencing (approximately equal to seven generations). Strains that exhibited silencing for an additional seven generations were isolated and kept for further study. From ∼90,000 mutagenized genomes, we isolated 20 strains fulfilling these criteria. We refer to the genes mutated in these strains as the heritable enhancer of RNAi (heri) genes.

heri-1 encodes a chromodomain protein with homology to Ser/Thr protein kinases

To assign identity to the heri genes, we used whole-genome sequencing coupled with custom scripts and the bioinformatic software CloudMap (Minevich et al. 2012; Spracklin et al. 2017) (Figure S1). This approach identified four independent mutations within the C. elegans gene cec-9/c29h12.5 (Figure 2A). For reasons outlined below, we refer to cec-9/c29h12.5 as heri-1. From strains harboring mutations in heri-1, we isolated rare individuals in which gfp and oma-1 silencing had been lost, and we used these “reset” strains to ask if these lines were indeed enhanced for RNAi inheritance. This analysis showed that RNAi inheritance after oma-1 or gfp RNAi was enhanced in all four heri-1 mutant strains (Figure 2, B and C). To confirm the molecular identity of heri-1, we tested an independently isolated allele of heri-1 (gk961392) for RNAi inheritance. Note that gk961392 likely represents a loss-of-function allele of heri-1, as gk961392 is a deletion that removes conserved domains of HERI-1 (see below) and alters the reading frame (Figure 2A). gk961392 animals exhibited an enhanced RNAi inheritance phenotype (Figure 2D and Figure S2). We conclude that cec-9/c29h12.5 is heri-1 and that one function of HERI-1 is to limit the generational perdurance of RNAi inheritance.

HERI-1 is expressed in germ cell nuclei

heri-1 encodes a protein with two conserved domains: a chromodomain and a serine/threonine kinase-like domain (Figure 2A). To understand more about HERI-1, we used CRISPR/Cas9 to introduce a C-terminal gfp::3xflag epitope to the 3′ terminus of the heri-1 locus (Arribere et al. 2014; Paix et al. 2014; Dickinson et al. 2015; Farboud and Meyer 2015). In heri-1::gfp::3xflag animals, we observed HERI-1::GFP expression in the nuclei of adult germ cells (Figure 3A). No HERI-1::GFP signal was observed in somatic tissues in adult animals (R. Perales, unpublished data). GFP fluorescence was expressed diffusely throughout nuclei and did not colocalize with mitotic chromosomes (Figure 3A and Figure S3). Similar results were seen when CRISPR was used to introduce a 3xflag epitope to heri-1 and anti-FLAG immunofluorescence was used to detect HERI-1::FLAG (Figure S3). RNAi inheritance assays indicated that the CRISPR-modified heri-1 locus produced functional HERI-1 protein (Figure S4). During embryogenesis in C. elegans, four asymmetric cell divisions partition germline determinants into the germline blastomeres termed the P0–P4 cells. During these early stages of embryogenesis, HERI-1::GFP was expressed in both germline and somatic blastomeres (Figure S5 and R. Perales, unpublished data). In the P1 blastomere, we detected a low level of GFP fluorescence in cytoplasmic puncta, whose subcellular distribution and morphology were reminiscent of P granules (Figure S5). By L1, HERI-1::GFP::3xFLAG was seen exclusively in the primordial germ cells Z2 and Z3, and was no longer seen in somatic tissues (Figure 3B). HERI-1::GFP was expressed in germ cell nuclei throughout the remainder of larval development and no GFP expression could be seen in the soma during larval development (Figure 3B and R. Perales, unpublished data). We conclude that HERI-1 is a germline-expressed protein that localizes predominantly to nuclei.

HERI-1 limits transgenerational siRNA and H3K9me3 expression

RNAi inheritance in C. elegans is correlated with the heritable expression of siRNAs, which are antisense to genes undergoing heritable silencing, as well as with the heritable deposition of repressive histone marks (e.g., H3K9me3) on genes that are undergoing heritable silencing (Burton et al. 2011; Ashe et al. 2012; Buckley et al. 2012; Gu et al. 2012; Shirayama et al. 2012). Therefore, inherited siRNAs and/or H3K9me3 may be the informational vectors that drive RNAi inheritance. We asked if the enhanced RNAi we see in heri-1 mutant animals was associated with an increase in the number of generations during which siRNAs and repressive chromatin marks were inherited. To do this, we used H3K9me3 ChIP and gfp siRNA Taqman probes to measure H3K9me3 deposited on the gfp gene and gfp siRNA levels, respectively, in wild-type and heri-1 mutant animals 20 generations after gfp RNAi had been initiated. Both H3K9me3 and siRNAs remained elevated in the F21 progeny of heri-1 mutant animals exposed to dsRNA (Figure 4, A and B), indicating that the Heri phenotype exhibited by heri-1 mutant animals is likely due to an increased generational perdurance of the gene silencing pathways mediating RNAi inheritance in wild-type animals.

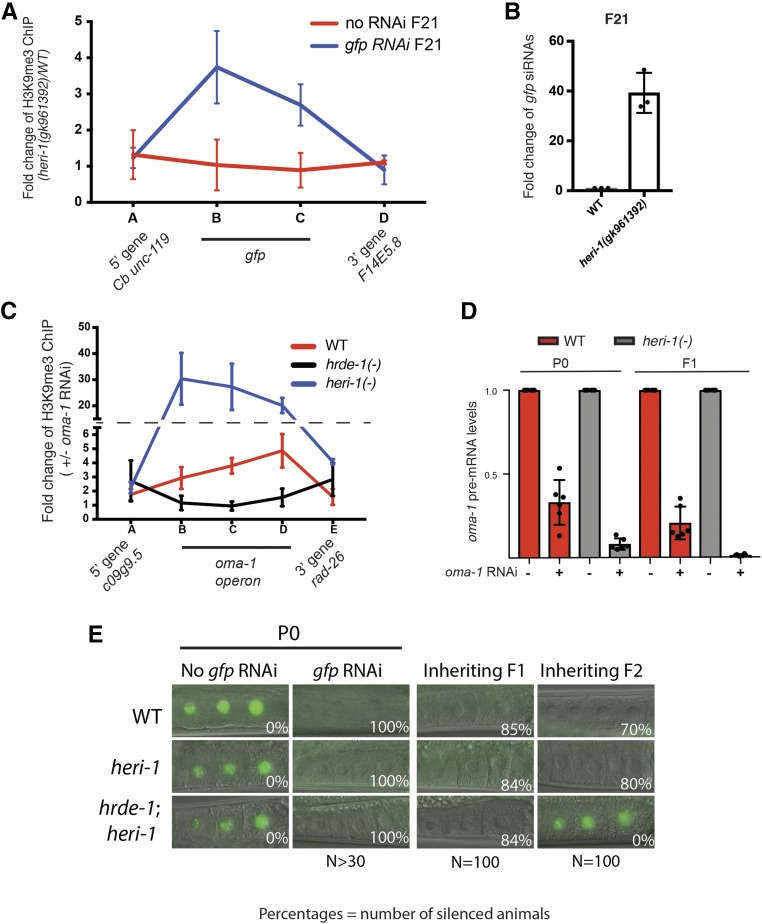

Figure 4.

HERI-1 inhibits nuclear RNAi. (A) H3K9me3 ChIP-qPCR on heri-1(+) heri-1(−) animals. Data are expressed as a ratio of H3K9me3 ChIP signals detected in heri-1(+) over heri-1(−) mutant animals before gfp RNAi (bottom panel) and 20 generations after gfp RNAi (bottom panel). Data are from three biological replicates and error bars are SD of the mean. (B) Total RNA isolated from animals of the indicated genotypes was used for Custom Taqman assays (Burton et al. 2011) to detect gfp siRNAs 20 generations after gfp RNAi treatment. Signal from WT (starting strain) animals is defined as one. Data are from three biological replicates and error bars are SD. (C) H3K9me3 ChIP was conducted on WT, heri-1 (gk961392), and hrde-1(tm1200) animals in the progeny of animals exposed +/− to oma-1 RNAi. Relative location of primers used for qPCR are indicated. Position along x-axis is not to scale with actual genomic loci (see Figure 5). Data are from three biological replicates and error bars are SD of the mean. Note, a value of one in this assay means that RNAi had no effect on the state of H3K9me3 at this locus. Data show that H3K9me3 is enriched within the oma-1 operon after oma-1 RNAi. oma-1 operon contains three genes; oma-1, spr-2, and c27b76.2. Primer set B and C are in oma-1. Primer set D is in spr-2. (D) qPCR data showing that the oma-1 pre-mRNA is more silenced in heri-1(gk961392) animals than in WT animals after oma-1 RNAi. Error bars are SD of the mean. Note, a value of one would indicate that RNAi had no effect on oma-1 pre-mRNA levels for this experiment. (E) Animals of the indicated genotypes [heri-1(gk961392) and hrde-1(tm1200)] and expressing pie-1::gfp::h2b were exposed to +/− gfp RNAi. Representative micrographs of −1, −2, and −3 oocytes are shown. Percentages of animals inheriting silencing in the indicated generations are shown. ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; qPCR, quantitative PCR; RNAi, RNA interference; siRNA, small interfering RNA; WT, wild-type.

HERI-1 inhibits nuclear RNAi

What pathway(s) might HERI-1 regulate to limit RNAi inheritance? The C. elegans nuclear RNAi pathway is required for RNAi inheritance; in animals lacking components of the nuclear RNAi machinery, H3K9me3 is not deposited on chromatin, siRNAs are not heritably expressed, and gene silencing is not maintained in inheriting generations (Burton et al. 2011; Ashe et al. 2012; Buckley et al. 2012; Gu et al. 2012; Shirayama et al. 2012). Note that the reason why nuclear RNAi is needed for RNAi inheritance is not yet known. Given that nuclear RNAi mediates RNAi inheritance and HERI-1 is a nuclear protein, we wondered if HERI-1 might limit RNAi inheritance by inhibiting nuclear RNAi. The following lines of evidence indicate that this is indeed the case. First, the nuclear RNAi machinery directs H3K9me3 deposition at genomic loci exhibiting sequence homology to RNAi triggers (Guang et al. 2010; Gu et al. 2012). Using H3K9me3 ChIP to quantify H3K9me3 levels before and after RNAi, we found that RNAi triggered the deposition of H3K9me3 (∼4–6×) in heri-1 mutant animals more than what is seen in wild-type animals after RNAi (which itself was ∼3–4× elevated over non-RNAi-treated animals) (Figure 4C). Second, exposure of C. elegans to dsRNA results in the nuclear RNAi-based silencing of unspliced nascent RNAs (pre-mRNA) exhibiting sequence homology to trigger dsRNAs (Guang et al. 2008, 2010; Burton et al. 2011). Using quantitative RT-PCR to quantify pre-mRNA levels before and after RNAi, we found that the degree to which RNAi silenced pre-mRNAs was greater in heri-1 mutant animals than in wild-type animals (Figure 4D). Finally, HRDE-1 is a germline Argonaute required for RNAi inheritance in wild-type animals. hrde-1 was epistatic to heri-1 for RNAi inheritance, suggesting that RNAi inheritance in heri-1 mutant animals depends upon nuclear RNAi (Figure 4E). We conclude that HERI-1 is a negative regulator of nuclear RNAi. We speculate that the inhibition of nuclear RNAi is the mechanism by which HERI-1 negatively regulates RNAi inheritance.

RNAi directs HERI-1 to chromatin

Chromodomains can interact with post-translationally modified histones such as H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 (Eissenberg 2012). Nuclear RNAi in C. elegans directs H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 (Guang et al. 2010; Buckley et al. 2012; Gu et al. 2012; Mao et al. 2015). These observations hint at the possibility that HERI-1, which possesses a chromodomain, might be physically recruited to genes undergoing nuclear RNAi and/or RNAi inheritance. To test this idea, we used HERI-1 ChIP to ask if RNAi would cause HERI-1 to associate with the chromatin of genes that we had targeted by RNAi. Indeed, we found that, after oma-1 RNAi, HERI-1::GFP::FLAG associated with the oma-1 locus, but not the genes flanking oma-1 (Figure 5). Similar results were seen when animals expressing HERI-1::FLAG were treated with oma-1 RNAi (Figure S6). We conclude that RNAi can direct HERI-1 to interact with chromatin of the gfp gene after exposing animals to gfp dsRNA triggers. The physical recruitment of HERI-1 to a gene targeted by RNAi suggests that HERI-1 may play a direct role in inhibiting nuclear RNAi and, therefore, RNAi inheritance.

Figure 5.

RNAi causes HERI-1 to associate with chromatin of genes undergoing heritable silencing. HERI-1::GFP::3xFlag animals were exposed to +/− oma-1 RNAi and HERI-1 ChIP was conducted on progeny. Fold enrichment of HERI-1 on the oma-1 locus, as well as neighboring loci, is shown and is expressed as a ratio of HERI-1 ChIP signals +/− oma-1 RNAi. Data are from three biological replicates and error bars are SD of the mean. Similar results were obtained when HERI-1::3xFLAG animals were subjected to a similar analysis (Figure S6). A value of one would indicate that RNAi had no effect on HERI-1 ChIP. Note that primer set D does not show RNAi-induced HERI-1 binding, but did show an increase in H3K9me3 in Figure 4C (see Discussion). ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; RNAi, RNA interference; WT, wild-type.

Recruitment of HERI-1 to chromatin requires nuclear RNAi

How is HERI-1 recruited to genes targeted by RNAi? heri-1 encodes a chromodomain. We wondered if nuclear RNAi-directed chromatin modifications (such as H3K9me3 or H3K27me3) might be responsible for recruiting HERI-1 (via chromatin PTM/chromodomain interactions) to genes after RNAi. Note that such a scenario would be somewhat surprising, as nuclear RNAi normally promotes gene silencing and HERI-1 limits this silencing. HRDE-1 is a nuclear AGO that drives nuclear RNAi in germ cells (Buckley et al. 2012). We exposed wild-type or hrde-1(−) animals to oma-1 RNAi and used HERI-1 ChIP to quantify HERI-1 chromatin interactions in these animals. The analysis showed that HRDE-1 was required for RNAi to direct HERI-1 to bind chromatin, suggesting that nuclear RNAi is, indeed, needed for RNAi to recruit HERI-1 to chromatin (Figure 5). The putative H3K9 methyltransferase SET-32/HRDE-3 is, at least in some cases, required for RNAi inheritance and contributes to RNAi-directed H3K9 methylation following RNAi (Ashe et al. 2012; Kalinava et al. 2017; Lev et al. 2017; Spracklin et al. 2017). We found that SET-32/HRDE-3 was required for oma-1 RNAi to recruit HERI-1 to the oma-1 gene, hinting that H3K9me3 may be a component of the chromatin signature that recruits HERI-1 to chromatin (Figure 5) [note that heri-1 chromodomain mutations destabilize HERI-1, making additional obvious tests of this model difficult (see Discussion)]. We conclude that HRDE-1 and SET-32/HRDE-3 are required for the recruitment of the negative regulator of nuclear RNAi HERI-1 to genomic sites of RNAi. Because HRDE-1 is required for nuclear RNAi (and SET-32/HRDE-3 contributes to nuclear RNAi), the data suggest that the nuclear RNAi machinery in C. elegans has both pro- and antisilencing outputs. First, the machinery links siRNAs to cotranscriptional gene silencing. Second, the machinery places limits on this silencing by recruiting the negative regulator HERI-1 to sites of nuclear RNAi, perhaps by altering chromatin landscapes in ways recognized by the HERI-1 chromodomain.

heri-1 mutant animals have defective sperm, which may be caused by hyperactive nuclear RNAi

While working with heri-1 mutant animals, we noticed that ≈20% of heri-1(gk961392) animals had a single or both gonad arms containing more oocytes than normal (termed a stacked oocyte phenotype) (Figure 6, A and B). Animals harboring any one of the four other heri-1 mutations also showed this stacked oocyte phenotype, albeit at a somewhat reduced rate (Figure S7). The data show that the loss of HERI-1 causes oocytes to accumulate within C. elegans germlines. Stacked oocytes are often seen in C. elegans lacking functional sperm (Schedl and Kimble 1988). Two additional lines of evidence support the idea that heri-1 mutant animals have dysfunctional sperm. First, heri-1(−) animals with stacked oocytes were sterile (Figure 6C). Second, wild-type sperm (introduced by mating) rescued the fertility defects of heri-1 animals, which had stacked oocytes (Figure 6C). We conclude that ≈20% of animals that lack HERI-1 produce dysfunctional sperm or have defects in spermatogenesis. To begin to differentiate these possibilities, we isolated and DAPI-stained animals in which one of two gonad arms contained stacked oocytes (Figure 6D). Spermatheca from “normal” germline arms possessed sperm; however, in spermatheca from defective germline arms (with stacked oocytes), no sperm could be seen (Figure 6D). The data suggest that heri-1 sperm are defective because either: (1) they never develop, or (2) develop but are dysfunctional and, consequently, are swept out of the spermatheca by ovulating oocytes. To distinguish these scenarios, we used Normarski microscopy to visualize spermatogenesis in wild-type and heri-1(−) mutant animals at mid-late fourth larval developmental stages. In total, 33% of heri-1(−) animals displayed defects in spermatogenesis, as early sperm precursor cells are present but did not develop into mature spermatids (Figure 6E). Wild-type animals did not exhibit such defects (Figure 6E). We conclude that some heri-1(−) mutant animals have defects in spermatogenesis. We wondered if heri-1(−) sperm defects were related to HERI-1’s role in limiting nuclear RNAi. If so, a hrde-1 mutation would be expected to suppress heri-1(−) sperm defects, as nuclear RNAi should no longer be hyperactive in animals that lack the AGO that directs nuclear RNAi. To test this idea, we quantified sperm defects in heri-1(−) and hrde-1(−) single-mutant animals as well as heri-1(−); hrde-1(−) double-mutant animals and found that, indeed, hrde-1 was epistatic to heri-1 with regard to spermatogenesis defects (Figure 6B). The data are consistent with the idea that HERI-1 limits nuclear RNAi (likely directed by endogenous nuclear siRNAs and HRDE-1) in sperm nuclei, and that this regulation is needed for normal sperm function and/or development.

Figure 6.

heri-1 mutant animals have defective sperm. (A) Fluorescent micrograph of WT or heri-1(gk961392) oocytes expressing pie-1p::h2b::gfp. Of the heri-1 mutant animals, 20% show a stacked oocytes in either one or both gonad arms. Asterisk indicates vulva. Thick arrows indicate stacked oocytes. Thin arrow indicates an unfertilized oocyte. (B) Quantification of the indicated oocyte defects in wild-type, heri-1(gk961392), hrde-1(tm1200), and double-mutant animals. Error bars are SD of the mean. (C) Number of progeny from heri-1(gk961392) animals that had stacked oocytes in both gonad arms that were selfed (self) or after crossing to WT (N2) males (cross). n = 13 for self and n = 14 for cross. (D) DAPI staining of a heri-1(gk961392);pie-1::h2b::gfp animals that had stacked oocytes in one gonad arm. A magnification of spermatheca from both gonad arms (indicated by box in “merge” panel) is shown below. Arrow indicates gonad arm with stacked oocytes. Asterisk indicates vulva. (E) Images of WT and heri-1(gk961392) animals undergoing spermatogenesis. Spermatogenesis steps are labeled for WT animals. heri-1(gk961392) fail to complete spermatogenesis. “%” refers to the percent of animals displaying spermatogenesis defects. RNAi, RNA interference; WT, wild-type.

Discussion

heri-1 encodes a chromo/kinase domain protein that negatively regulates nuclear RNAi and RNAi inheritance. We speculate that it is the ability of HERI-1 to limit nuclear RNAi that allows HERI-1 to limit RNAi inheritance. Interestingly, we find that HERI-1 is recruited to genes targeted by RNAi, suggesting that HERI-1 may be a direct regulator of RNAi inheritance and, therefore, that C. elegans possess genetically encoded systems dedicated to limiting RNA-directed TEI during normal reproduction. Finally, we find that the NRDE nuclear RNAi system, which is itself needed for nuclear RNAi, is needed to localize the negative regulator of nuclear RNAi HERI-1 to genes. These data suggest that the nuclear RNAi machinery has two outputs during RNAi inheritance: (1) to promote cotranscriptional gene silencing and (2) to recruit negative regulators of nuclear RNAi to limit the number of generations over which epigenetic information is inherited.

How does HERI-1 inhibit nuclear RNAi?

HERI-1 has homology to serine/threonine protein kinases, and one of the heri-1 alleles that we identified in our genetic screen (gg538) alters a conserved aspartate residue within the HERI-1 kinase-like domain (Figure 2A). Thus, the HERI-1 kinase-like domain is likely important for HERI-1 to inhibit nuclear RNAi and, therefore, RNAi inheritance; however, HERI-1 is unlikely to be an active protein kinase, as its kinase domain lacks active site residues required for kinase activity in related protein kinases (Nolen et al. 2004). For instance, the GxGxxG, VAIK, and DFG motifs, which contribute to Mg2+ and ATP binding in canonical protein kinases, are not conserved in HERI-1 (Figure S8). Additionally, we failed to detect kinase activity associated with recombinant HERI-1 protein in vitro (Figure S9). Thus, we predict that HERI-1 is a pseudokinase. Pseudokinases are fairly common in eukaryotes where they often play important roles in diverse aspects of cellular physiology, such as acting as scaffolds, anchors, or allosteric regulators of other proteins, including other protein kinases (Eyers and Murphy 2013). Given that HERI-1 is recruited to sites of nuclear RNAi, we speculate that HERI-1 negatively regulates nuclear RNAi by interacting with and allosterically regulating other prosilencing factors at sites of nuclear RNAi (Figure 7). Potential targets of such regulation include the nuclear RNAi factors HRDE-1 and NRDE-1/2/4, as well as the chromatin-modifying enzymes that impart repressive modifications to chromatin in response to nuclear RNAi (Guang et al. 2010; Burkhart et al. 2011; Buckley et al. 2012) (Figure 7). HERI-1 IP-MS might identify the regulatory targets of HERI-1.

Figure 7.

Model for the role of HERI-1 in limiting RNA inheritance. The AGO HRDE-1 uses siRNAs as guides to recognize and bind pre-mRNAs with sequence homology to siRNAs. HRDE-1 then recruits downstream silencing factors, such as the NRDEs (unlabeled teal ovals) and chromatin-modifying enzymes, to deposit H3K9me3 as well as another, currently unknown (X), signal on chromatin to mark genes undergoing nuclear RNAi. Note: X could be another chromatin PTM or a chromatin/DNA-binding protein. X and H3K9me3 cooperate to recruit HERI-1 to chromatin. HERI-1 is a pseudokinase that may limit RNAi inheritance by binding and regulating prosilencing proteins (such as HRDE-1 or NRDEs) that are present on genes undergoing nuclear RNAi/RNAi inheritance. The model predicts that nuclear RNAi drives cotranscriptional gene silencing by inhibiting RNA Polymerase II (RNAP II) while, at the same time, limiting this silencing by recruiting negative regulators of the process, such as HERI-1, to sites of nuclear RNAi/RNAi inheritance. NRDE, nuclear RNA defective; RNAi, RNA interference; siRNA, small interfering RNAs; WT, wild-type.

How is HERI-1 recruited to chromatin?

HERI-1 is recruited to chromatin in response to RNAi (Figure 5). Recruitment is dependent upon the nuclear RNAi AGO HRDE-1, suggesting that nuclear siRNAs direct HERI-1 recruitment to chromatin (Figure 5). How might nuclear siRNAs recruit HERI-1 to chromatin? The nuclear RNAi pathway directs the deposition of repressive chromatin marks such as H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 on the chromatin of genes undergoing nuclear RNAi (Guang et al. 2010; Burkhart et al. 2011; Gu et al. 2012; Mao et al. 2015). Additionally, HERI-1 has a chromodomain, and chromodomains are well known to bind post-translationally modified histones, such as H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 (Eissenberg 2012). Together, these observations suggest the following model. First, nuclear RNAi directs PTMs such as H3K9me3 on chromatin. Second, these PTMs interact with the chromodomain of HERI-1 to recruit HERI-1 to genes, so that HERI-1 can limit nuclear RNAi. Consistent with the model, we find that the putative H3K9 methyltransferase SET-32/HRDE-3 is required for oma-1 RNAi to direct HERI-1 to oma-1 chromatin (Figure 5). Note, however, that we detected an increase in H3K9me3, but not an increase of HERI-1 binding, on the spr-2 gene after oma-1 RNAi, indicating that H3K9me3 and HERI-1 binding are dissociable (Figure 4C and Figure 5, primer D). Therefore, although H3K9me3 may be necessary for recruiting HERI-1 to chromatin, it is unlikely to be sufficient. Indeed, recent studies show that the role of H3K9 methylation during RNAi inheritance is complex, involving multiple H3K9 methyltransferase enzymes, multiple nuclear RNAi-directed chromatin modifications, as well as a locus-specific dependence upon H3K9me3 for inheritance (Ashe et al. 2012; Kalinava et al. 2017; Lev et al. 2017; Spracklin et al. 2017). For instance, genetic screens, and candidate gene approaches, show that SET-32/HRDE-3 promotes RNAi-directed H3K9 methylation and RNAi inheritance when gfp reporter transgenes are targeted for silencing by dsRNA or piRNAs (Ashe et al. 2012; Spracklin et al. 2017). However, in other RNAi inheritance assays, (such as oma-1 RNAi inheritance), set-32/hrde-3(−) animals may lack most RNAi-directed H3K9me3 marks but these animals do not show obvious defects in inherited gene silencing (Kalinava et al. 2017). Additionally, C. elegans lacking two other H3K9 methyltransferase enzymes, MET-2 and SET-25, lack biochemically detectable levels of H3K9me2/3 in germ cells, and yet these animals do not show obvious defects in oma-1 RNAi inheritance (Towbin et al. 2012; Kalinava et al. 2017). Even more puzzling, animals lacking SET-25 (H3K9me3) alone show defects in RNAi inheritance when some gfp reporter transgenes and some endogenous loci are targeted by RNAi (L. Wong, unpublished data), while animals lacking MET-2 (H3K9me2) alone show a Heri phenotype when a gfp reporter gene is targeted by RNAi (Lev et al. 2017) [note that these later data hint at the tantalizing possibility that H3K9me2 (deposited by MET-2) might be the signal responsible for HERI-1 recruitment to chromatin]. Given the complex relationship that exists between nuclear RNAi, chromatin PTMs, and RNAi inheritance, it seems likely that biochemical studies seeking to identify the histone PTM code bound by the HERI-1 chromodomain will be needed to figure out how HERI-1 is recruited to chromatin to regulate nuclear RNAi. Identifying and characterizing additional heri genes (defined by our genetic screen) might also be helpful in this regard. Note that any in vivo studies exploring how the HERI-1 chromodomain recruits HERI-1 to chromatin by RNAi will be complicated by the fact that HERI-1 chromodomain mutations destabilize HERI-1 (Figure S10).

HERI-1 and sperm function

Why would C. elegans need factors that limit nuclear RNAi in germ cells? C. elegans expresses an abundant class of endogenous siRNAs that are thought to direct nuclear RNAi in nuclei during the normal course of growth and reproduction (Lee et al. 2006; Guang et al. 2008, 2010; Burkhart et al. 2011; Billi et al. 2014). Some of these endogenous siRNAs are thought to be present in sperm progenitors, where they regulate gene expression programs needed for sperm development and function (Sijen et al. 2001; Kennedy et al. 2004; Duchaine et al. 2006; Gent et al. 2009, 2010; Pavelec et al. 2009; Conine et al. 2010; Vasale et al. 2010). We find that heri-1 mutant animals exhibit spermatogenesis defects, which are suppressed by loss of the germline nuclear RNAi AGO HRDE-1. The data suggest that one function of TEI-regulating systems in C. elegans is to limit endogenous nuclear RNAi (directed by sperm 22G siRNAs) in sperm progenitors, and that this gene regulation is important for spermatogenesis. Such gene misregulation might occur in sperm progenitors at genes normally targeted by nuclear 22G endo siRNAs in wild-type animals or, alternatively, at genes that are not normally subjected to nuclear RNAi. Regarding this latter model, endogenous RNAi (like experimental RNAi) is driven by 22G siRNAs, which are maintained over generations by RdRP enzymes (Gent et al. 2009, 2010; Buckley et al. 2012). This self-amplifying feedforward mode of gene regulation could be dangerous if genes that are not normally silenced by endogenous siRNAs (or are only marginally silenced) were to inappropriately enter states of heritable silencing. Therefore, we speculate that HERI-1 might promote germ cell health by preventing and/or reversing such unwanted and runaway heritable gene silencing. The identification of HERI-1 regulated sperm genes (via HERI-1 ChIP), and/or loci regulated by nuclear RNAi in wild-type and heri-1 mutant animals (H3K9me3 ChIP or RNA-Seq), will allow this idea to be tested.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Kennedy laboratory for helpful discussions of the data and the manuscript; Judith Kimble for helpful discussions; Paula Montero Llopis of the Microscopy Resources On the North Quad imaging core at Harvard Medical School for microscope access, training, and helpful discussions; and Catherine Musselman at the University of Iowa for the purified recombinant histone H3. Some strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (P40 OD-010440). Some strains were provided by the Mitani laboratory through the National Bio-Resource Project of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. R.P. and D.P. were funded by F32 awards from the NIH. B.D.F. was funded by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. This work was supported by the NIH, RO1 GM-088289 (S.G.K.). The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material available at Figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.7229294.

Communicating editor: D. Greenstein

Literature Cited

- Alcazar R. M., Lin R., Fire A. Z., 2008. Transmission dynamics of heritable silencing induced by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 180: 1275–1288. 10.1534/genetics.108.089433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alleman M., Sidorenko L., McGinnis K., Seshadri V., Dorweiler J. E., et al. , 2006. An RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is required for paramutation in maize. Nature 442: 295–298. 10.1038/nature04884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen E. C., Horvitz H. R., 2007. Two C. elegans histone methyltransferases repress lin-3 EGF transcription to inhibit vulval development. Development 134: 2991–2999. 10.1242/dev.009373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribere J. A., Bell R. T., Fu B. X., Artiles K. L., Hartman P. S., et al. , 2014. Efficient marker-free recovery of custom genetic modifications with CRISPR/Cas9 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 198: 837–846. 10.1534/genetics.114.169730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga-Vazquez M. A., Chandler V. L., 2010. Paramutation in maize: RNA mediated trans-generational gene silencing. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 20: 156–163. 10.1016/j.gde.2010.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashe A., Sapetschnig A., Weick E.-M., Mitchell J., Bagijn M. P., et al. , 2012. piRNAs can trigger a multigenerational epigenetic memory in the germline of C. elegans. Cell 150: 88–99. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billi A. C., Fischer S. E. J., Kim J. K., 2014. Endogenous RNAi pathways in C. elegans (May 7, 2014), WormBook, ed. The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook, /10.1895/wormbook.1.170.1, http://www.wormbook.org. 10.1895/wormbook.1.170.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley B. A., Burkhart K. B., Gu S. G., Spracklin G., Kershner A., et al. , 2012. A nuclear Argonaute promotes multigenerational epigenetic inheritance and germline immortality. Nature 489: 447–451. 10.1038/nature11352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart K. B., Guang S., Buckley B. A., Wong L., Bochner A. F., et al. , 2011. A pre-mRNA-associating factor links endogenous siRNAs to chromatin regulation. PLoS Genet. 7: e1002249 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton N. O., Burkhart K. B., Kennedy S., 2011. Nuclear RNAi maintains heritable gene silencing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 19683–19688. 10.1073/pnas.1113310108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carone B. R., Fauquier L., Habib N., Shea J. M., Hart C. E., et al. , 2010. Paternally induced transgenerational environmental reprogramming of metabolic gene expression in mammals. Cell 143: 1084–1096. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel S. E., Martienssen R. A., 2013. RNA interference in the nucleus: roles for small RNAs in transcription, epigenetics and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14: 100–112. 10.1038/nrg3355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checchi P. M., Engebrecht J., 2011. Caenorhabditis elegans histone methyltransferase MET-2 shields the male X chromosome from checkpoint machinery and mediates meiotic sex chromosome inactivation. PLoS Genet. 7: e1002267 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conine C. C., Batista P. J., Gu W., Claycomb J. M., Chaves D. A., et al. , 2010. Argonautes ALG-3 and ALG-4 are required for spermatogenesis-specific 26G-RNAs and thermotolerant sperm in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 3588–3593. 10.1073/pnas.0911685107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D. J., Pani A. M., Heppert J. K., Higgins C. D., Goldstein B., 2015. Streamlined genome engineering with a self-excising drug selection cassette. Genetics 200: 1035–1049. 10.1534/genetics.115.178335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchaine T. F., Wohlschlegel J. A., Kennedy S., Bei Y., Conte D., Jr., et al. , 2006. Functional proteomics reveals the biochemical niche of C. elegans DCR-1 in multiple small-RNA-mediated pathways. Cell 124: 343–354. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Urso A., Brickner J. H., 2014. Mechanisms of epigenetic memory. Trends Genet. 30: 230–236. 10.1016/j.tig.2014.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg J. C., 2012. Structural biology of the chromodomain: form and function. Gene 496: 69–78. 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyers P. A., Murphy J. M., 2013. Dawn of the dead: protein pseudokinases signal new adventures in cell biology. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 41: 969–974. 10.1042/BST20130115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farboud B., Meyer B. J., 2015. Dramatic enhancement of genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 through improved guide RNA design. Genetics 199: 959–971. 10.1534/genetics.115.175166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gapp K., Jawaid A., Sarkies P., Bohacek J., Pelczar P., et al. , 2014. Implication of sperm RNAs in transgenerational inheritance of the effects of early trauma in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 17: 667–669. 10.1038/nn.3695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gent J. I., Schvarzstein M., Villeneuve A. M., Gu S. G., Jantsch V., et al. , 2009. A Caenorhabditis elegans RNA-directed RNA polymerase in sperm development and endogenous RNA interference. Genetics 183: 1297–1314. 10.1534/genetics.109.109686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gent J. I., Lamm A. T., Pavelec D. M., Maniar J. M., Parameswaran P., et al. , 2010. Distinct phases of siRNA synthesis in an endogenous RNAi pathway in C. elegans soma. Mol. Cell 37: 679–689. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S. G., Pak J., Guang S., Maniar J. M., Kennedy S., et al. , 2012. Amplification of siRNA in Caenorhabditis elegans generates a transgenerational sequence-targeted histone H3 lysine 9 methylation footprint. Nat. Genet. 44: 157–164. 10.1038/ng.1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guang S., Bochner A. F., Pavelec D. M., Burkhart K. B., Harding S., et al. , 2008. An Argonaute transports siRNAs from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Science 321: 537–541. 10.1126/science.1157647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guang S., Bochner A. F., Burkhart K. B., Burton N., Pavelec D. M., et al. , 2010. Small regulatory RNAs inhibit RNA polymerase II during the elongation phase of transcription. Nature 465: 1097–1101. 10.1038/nature09095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard E., Martienssen R. A., 2014. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: myths and mechanisms. Cell 157: 95–109. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holoch D., Moazed D., 2015. RNA-mediated epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16: 71–84. 10.1038/nrg3863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinava N., Ni J. Z., Peterman K., Chen E., Gu S. G., 2017. Decoupling the downstream effects of germline nuclear RNAi reveals that H3K9me3 is dispensable for heritable RNAi and the maintenance of endogenous siRNA-mediated transcriptional silencing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Epigenetics Chromatin 10: 6 10.1186/s13072-017-0114-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S., Wang D., Ruvkun G., 2004. A conserved siRNA-degrading RNase negatively regulates RNA interference in C. elegans. Nature 427: 645–649. 10.1038/nature02302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. C., Hammell C. M., Ambros V., 2006. Interacting endogenous and exogenous RNAi pathways in Caenorhabditis elegans. RNA 12: 589–597. 10.1261/rna.2231506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Thomas A., Stuwe E., Li S., Du J., Marinov G., et al. , 2014. Transgenerationally inherited piRNAs trigger piRNA biogenesis by changing the chromatin of piRNA clusters and inducing precursor processing. Genes Dev. 28: 1667–1680. 10.1101/gad.245514.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev I., Seroussi U., Gingold H., Bril R., Anava S., et al. , 2017. MET-2-dependent H3K9 methylation suppresses transgenerational small RNA inheritance. Curr. Biol. 27: 1138–1147. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R., 2003. A gain-of-function mutation in oma-1, a C. elegans gene required for oocyte maturation, results in delayed degradation of maternal proteins and embryonic lethality. Dev. Biol. 258: 226–239. 10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00119-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao H., Zhu C., Zong D., Weng C., Yang X., et al. , 2015. The Nrde pathway mediates small-RNA-directed histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 25: 2398–2403. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen R., Moazed D., 2015. RNAi and heterochromatin assembly. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7: a019323 10.1101/cshperspect.a019323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen R. A., Zaratiegui M., Goto D. B., 2005. RNA interference and heterochromatin in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Trends Genet. 21: 450–456. 10.1016/j.tig.2005.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister G., 2013. Argonaute proteins: functional insights and emerging roles. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14: 447–459. 10.1038/nrg3462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minevich G., Park D. S., Blankenberg D., Poole R. J., Hobert O., 2012. CloudMap: a cloud-based pipeline for analysis of mutant genome sequences. Genetics 192: 1249–1269. 10.1534/genetics.112.144204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen B., Taylor S., Ghosh G., 2004. Regulation of protein kinases; controlling activity through activation segment conformation. Mol. Cell 15: 661–675. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan N., Jia D., Geary-Joo C., Wu X., Ferguson-Smith A. C., et al. , 2013. Mutation in folate metabolism causes epigenetic instability and transgenerational effects on development. Cell 155: 81–93. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paix A., Wang Y., Smith H. E., Lee C. Y., Calidas D., et al. , 2014. Scalable and versatile genome editing using linear DNAs with microhomology to Cas9 Sites in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 198: 1347–1356. 10.1534/genetics.114.170423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavelec D. M., Lachowiec J., Duchaine T. F., Smith H. E., Kennedy S., 2009. Requirement for the ERI/DICER complex in endogenous RNA interference and sperm development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 183: 1283–1295. 10.1534/genetics.109.108134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford E. J., Isganaitis E., Jimenez-Chillaron J., Schroeder J., Molla M., et al. , 2012. An unbiased assessment of the role of imprinted genes in an intergenerational model of developmental programming. PLoS Genet. 8: e1002605 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragunathan K., Jih G., Moazed D., 2015. Epigenetics. Epigenetic inheritance uncoupled from sequence-specific recruitment. Science 348: 1258699 10.1126/science.1258699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin C. H., 2015. A review of transgenerational epigenetics for RNAi, longevity, germline maintenance and olfactory imprinting in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Exp. Biol. 218: 41–49. 10.1242/jeb.108340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapetschnig A., Sarkies P., Lehrbach N. J., Miska E. A., 2015. Tertiary siRNAs mediate paramutation in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 11: e1005078 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schedl T., Kimble J., 1988. fog-2, a germ-line-specific sex determination gene required for hermaphrodite spermatogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 119: 43–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma U., Conine C. C., Shea J. M., Boskovic A., Derr A. G., et al. , 2016. Biogenesis and function of tRNA fragments during sperm maturation and fertilization in mammals. Science 351: 391–396. 10.1126/science.aad6780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama M., Seth M., Lee H.-C., Gu W., Ishidate T., et al. , 2012. piRNAs initiate an epigenetic memory of nonself RNA in the C. elegans germline. Cell 150: 65–77. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorter J., Lindquist S., 2005. Prions as adaptive conduits of memory and inheritance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6: 435–450. 10.1038/nrg1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijen T., Fleenor J., Simmer F., Thijssen K. L., Parrish S., et al. , 2001. On the role of RNA amplification in dsRNA-triggered gene silencing. Cell 107: 465–476. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00576-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somer R. A., Thummel C. S., 2014. Epigenetic inheritance of metabolic state. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 27: 43–47. 10.1016/j.gde.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spracklin G., Fields B., Wan G., Vijayendran D., Wallig A., et al. , 2017. Identification and characterization of Caenorhabditis elegans RNAi inheritance machinery. Genetics. 2017 Jul;206(3):1403–1416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Towbin B. D., González-Aguilera C., Sack R., Gaidatzis D., Kalck V., et al. , 2012. Step-wise methylation of histone H3K9 positions heterochromatin at the nuclear periphery. Cell 150: 934–947. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasale J. J., Gu W., Thivierge C., Batista P. J., Claycomb J. M., et al. , 2010. Sequential rounds of RNA-dependent RNA transcription drive endogenous small-RNA biogenesis in the ERGO-1/Argonaute pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 3582–3587. 10.1073/pnas.0911908107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vastenhouw N. L., Brunschwig K., Okihara K. L., Müller F., Tijsterman M., et al. , 2006. Gene expression: long-term gene silencing by RNAi. Nature 442: 882 10.1038/442882a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe T. A., Kidner C., Hall I. M., Teng G., Grewal S. I. S., et al. , 2002. Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science 297: 1833–1837. 10.1126/science.1074973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D. M., Gore A. C., 2011. Transgenerational neuroendocrine disruption of reproduction. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 7: 197–207. 10.1038/nrendo.2010.215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan G., Fields B. D., Spracklin G., Shukla A., Phillips C. M., et al. , 2018. Spatiotemporal regulation of liquid-like condensates in epigenetic inheritance. Nature 557: 679–683. 10.1038/s41586-018-0132-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Strains, plasmids, and whole-genome sequencing data are available upon request. The authors affirm that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions of the article are present within the article, figures, and tables. Supplemental data has been uploaded to Figshare, including WGS sequencing data for each of the four heri-1 alleles identified by WGS. Table S1 contains the strains used in this study. The Supplemental Figures document contains Figures S1–S10. Supplemental material available at Figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.7229294.