Abstract

Objectives

Parental childhood maltreatment has a negative impact on psychological well-being in adulthood. However, little is known about whether and how contemporary relationships with an abusive parent might explain the long-term harmful effects. Thus, this study aims to examine the mediating effect of later-life relationships with an abusive parent on the association between parental childhood maltreatment and psychological well-being.

Methods

Using the 2004–2005 Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, this study analyzed a total of 1,696 adults aged 65 years. A series of ordinary least squares regression and mediational analyses were performed.

Results

Key findings showed that maternal childhood neglect and abuse were associated with decreased emotional closeness with mothers, which was, in turn, associated with diminished psychological well-being. In addition, childhood neglect was associated with less frequent exchanges of social support with mothers, which was, in turn, associated with diminished psychological well-being.

Discussion

This study suggests that, despite childhood maltreatment, parent–child relationships persist throughout life, and the continuing relationship with an abusive parent may undermine adult victims’ psychological well-being. When intervening with mental health issues of adults who have experienced childhood maltreatment, their unresolved issues with the parent should be properly addressed.

Keywords: Childhood abuse, Childhood neglect, Intergenerational solidarity, Psychological well-being

Lifelong sequelae of parental childhood maltreatment are well established. Particularly, pervasive evidence exists that a history of childhood maltreatment is linked with adult psychological health, such as depression, anxiety disorders, or diminished psychological well-being (Green et al., 2010; Greenfield & Marks, 2010). Along this line, researchers in diverse fields have identified several mechanisms to explain the long-term toxic effects of childhood maltreatment, which can include a disrupted biological regulation system or impaired social relationships (Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002; Sperry & Widom, 2013).

Yet, researchers have not considered the continuing relationship with an abusive parent as a possible mechanism, even though parent–child relationships are lifetime in nature and closely interwoven over the life course (Elder, 1994). According to scant but convincing clinical and empirical evidence, adults with a history of childhood maltreatment remain bound in the relationship with their abusive parent, and some even carry out filial roles by providing care to the latter (Kong & Moorman, 2015).

Therefore, this study aims to address this gap in the literature by examining a sample of 1,696 adults using data from the 2004–2005 Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS). A primary focus was to examine whether and how contemporary relationships with abusive mothers and fathers would mediate the association between childhood maltreatment and psychological well-being later in life. Based on the intergenerational solidarity theory, relationships with a parent were assessed by five dimensions: frequency of contact, residential proximity, emotional closeness, similarity in outlook/opinion, and exchange of social support. Normative solidarity (i.e., filial obligation) was excluded from this study because the measurement was not available in the WLS. By uncovering the evidence of the continuing parental influence on adults with a history of childhood neglect/abuse, the current study will enhance the understanding of later-life families with a history of adversity.

Intergenerational Solidarity Theory

Parent and adult–child relationships have been studied under the realm of intergenerational solidarity theory (Bengtson, 1996). Intergenerational solidarity, defined as a “higher order concept that encompasses the multiple, complex, and sometimes contradictory ways that parents and children are socially connected to each other” (Lawton, Silverstein, & Bengtson, 1994, p. 59), consists of six distinct elements, including associational solidarity (i.e., frequency of contact), structural solidarity (i.e., geographic proximity), affectual solidarity (i.e., emotional closeness), consensual solidarity (i.e., agreement on values, attitudes, and beliefs), functional solidarity (i.e., exchange of social support), and normative solidarity (i.e., commitment to filial obligations). Much of the theoretical discussion has evolved around the life course perspective, which concerns itself in part with how intergenerational relationships change or maintain over time, and what their impacts are on an individual’s well-being and functioning (Bengtson, Giarrusso, Mabry, & Silverstein, 2002).

Despite its reliance on the life-course perspective, however, the intergenerational solidarity theory has not been used to examine whether and how a history of parental maltreatment affects later-life relationships with an abusive parent. As the linked lives principle of the life course perspective suggests, family relationships are mutually interdependent and reciprocally influential over the life course (Elder, 1994; Setterstein, 2015). This theorizing may apply to adults with a history of childhood maltreatment in that, despite their past experience, they may maintain a relationship with their aging, once abusive, parent because the parent has long-term care needs and/or the adult child feels, for whatever reason, obligated. However, repercussions from the past abuse may continue to affect the relationship with an abusive parent once the child is an adult. In this sense, multiple dimensions of intergenerational solidarity might come into play, in a dynamic that could negatively impact psychological well-being of adult children.

Childhood Maltreatment and Psychological Well-Being in Late Adulthood

A great deal of empirical research has documented the negative effects of childhood maltreatment on psychological well-being in adulthood. For example, Herrenkohl and colleagues (2012) conducted a prospective study by analyzing child welfare reports on 357 children who were followed longitudinally over three decades. The results showed that adult victims showed negative psychological well-being in terms of anger proneness, self-esteem, acceptance, autonomy, sense of purpose in life, happiness, and life satisfaction. One thing to note, however, is that parent gender has gained little attention in terms of assessing long-term impact of childhood maltreatment (Sturge-Apple, Skibo, & Davies, 2012) although some available studies suggest distinct gender effects. Greenfield and Marks (2010) found that maternal psychological abuse was associated with more negative affect and diminished psychological well-being, but maternal physical abuse alone did not predict poor mental health. However, paternal psychological and physical abuse, regardless of frequency, were associated with poor mental health. Fergusson and Horwood (1998) also found that mother-perpetrated abuse was associated with alcohol abuse/dependence whereas father-perpetrated abuse was associated with conduct disorder, property offending, and anxiety disorder among a sample of older adolescents.

Contemporary Intergenerational Solidarity as a Potential Mediator

Only a paucity of empirical evidence exists regarding the continuing relationships between adult victims of childhood maltreatment and their abusive parents. According to Savla and colleagues (2013), childhood emotional abuse within family predicted lower family solidarity (i.e., emotional closeness to family) in mid- and later life. A history of childhood maltreatment was also associated with lower levels of family obligation in midlife (Parker, Maier, & Wojciak, 2016). Similarly, Kong and Moorman (2016) found that a history of maternal childhood abuse was associated with the adult child’s providing less frequent emotional support to the abusive mother, although his/her provision of instrumental support to the mother was not significantly affected. All of these findings affirm that childhood maltreatment could, indeed, hinder diverse aspects of contemporary relationships with the abusive parent(s).

In regards to the association between intergenerational solidarity and psychological well-being, much extant research has found that strong intergenerational solidarity enhances individual well-being in later life (Bengtson et al., 2002; Silverstein, Conroy, & Gans, 2012). The intergenerational solidarity literature consistently suggests that affectual solidarity is positively linked with individual well-being (Fingerman, Sechrist, & Birditt, 2013; Merz, Consedine, Schulze, & Schuengel, 2009). For example, Umberson (1992) found that frequent contacts with mothers and receipts of social support from them predicted less depressive symptoms for adult children whereas strained relationships with parents predicted more frequent depressive symptoms.

Theoretical considerations and the review of the relevant empirical work all suggest that parental childhood maltreatment may predict lower levels of contemporary solidarity in the relationship between the adult child and his/her abusive parent(s), and that this diminished solidarity could have deleterious impacts on psychological well-being of adult children. Thus, the following hypotheses were evaluated: (a) a history of childhood neglect and abuse will be negatively associated with psychological well-being among adult children, and (b) a history of childhood neglect and abuse will be associated with less frequent contact with an abusive parent as well as less residential proximity, lower emotional closeness, less similarity in opinion/outlook, and less frequent exchange of social support with that parent, which will ultimately undermine the psychological well-being of adult children.

Methods

Data Set

The WLS is a longitudinal study of 10,317 Wisconsin high school graduates in 1957. Survey data were collected from the graduates in the years of 1993–1994, 2004–2005, and 2010–2011, which provide extensive information on respondents’ lives, from late-adolescence through their early-/mid-70s. The present study used the 2004–2005 wave because most graduates still had one or more parents alive at that time. Additionally, at this specific wave, most graduates had turned 65-years-old, which allowed for examining later-life intergenerational relationships.

Measures

Psychological well-being

Psychological well-being was measured by 31 items derived from the well-validated measure of Ryff’s Psychological Well-being scales (Ryff PWB; Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Ryff PWB is one of the widely used instruments measuring the positive aspects of psychological functioning (Abbott, Ploubidis, Huppert, Kuh, & Croudace, 2010), which consists of six theoretically motivated dimensions: “a sense of self-determination” (autonomy); “the capacity to manage effectively one’s life and surrounding world” (environmental mastery); “a sense of continued growth and development as a person” (personal growth); “the possession of quality relations with others” (positive relations with others); “the belief that one’s life is purposeful and meaningful” (purpose in life); and “positive evaluations of oneself and one’s past life” (self-acceptance; Ryff & Keyes, 1995, p. 720). Five items asked about respondents’ feelings of autonomy (e.g., “I have confidence in my opinions even if they are contrary to the general consensus”), five items for environmental mastery (e.g., “In general, I feel I am in charge of the situation in which I live.”), five items for personal growth (e.g., “I have the sense that I have developed a lot as a person over time.”), five items for positive relations with others (e.g., “people would describe me as a giving person, willing to share my time with other.”), six items for purpose in life (e.g., “I am an active person in carrying out the plans I set for myself.”), and five items for self-acceptance (e.g., “In general, I feel confident and positive about myself.”). Response choices for each item were based on a six-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). The average score of the 31 items was used as the outcome variable to be consistent with prior studies on intergenerational solidarity that used the overall, comprehensive subjective well-being measures (e.g., Merz et al., 2009). The internal consistency of the measure was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92).

Childhood neglect

Childhood neglect was measured by an item: “Up until you were 18, how often did you know that there was someone to take care of you and protect you?” Response choices were based on a five-point Likert scale: never (1), rarely (2), sometimes (3), often (4), and very often (5). Respondents who answered never and rarely were coded as having been neglected.

Childhood abuse

A history of childhood abuse was assessed by a parent’s verbal abuse and physical abuse based on the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Gelles, & Steinmetz, 1980). Childhood verbal abuse was measured by an item: “Up until you were 18, to what extent did your mother/father insult or swear at you?” Response choices were based on a four-point Likert scale: not at all (1), a little (2), some (3), and a lot (4). Respondents who answered some and a lot were coded as having been verbally abused. Childhood physical abuse was measured by two items. One item asked: “Up until you were 18, to what extent did your mother/father treat you in a way that you would now consider physical abuse?” Response choices were based on a four-point Likert scale: not at all (1), a little (2), some (3), and a lot (4), and respondents who answered a little, some, or a lot were coded as having been physical abused. Also, the other item asked: “Up-until you were 18, to what extent did your mother/father slap, shove or throw things at you?”, and those who answered some and a lot were coded as having been physical abused.

Intergenerational solidarity

Each of five intergenerational solidarity constructs was assessed by single-item indicators of associational solidarity, structural solidarity, affectual solidarity, consensual solidarity, and functional solidarity (normative solidarity was not available in the WLS). Associational solidarity was measured by an item: “How frequently do you have contact with your mother/father?” It was a scale variable ranging from 0 to 950 times per year. The item was recoded to have four response choices to deal with skewness: (1) less than once a week, (2) once a week, (3) more than once a week, and (4) every day or more. Structural solidarity was measured by an item: “How many miles do you live from your mother/father’s place of residence?” This item was a scale variable ranging from 0 to 9,000 miles. As guided by previous studies (e.g., Campton & Pollak, 2009), this item was recoded to have four response choices to deal with skewness. After the recoding, the variable was reverse coded so that greater values indicate higher proximity: (1) 780 miles or more, (2) 30–780 miles (12 h drive), (3) less than 30 miles (1 h drive), and (4) living with the parent. Affectual solidarity was measured by an item: “How close are you to your mother/father?” Respondents rated the item using a four-point Likert scale (1 = not at all close, 2 = not very close, 3 = somewhat close, 4 = very close). Consensual solidarity was measured by an item, “How similar of an outlook on life do you and your mother/father have?” Respondents rate the item using a four-point Likert scale (1 = not at all similar, 2 = not very similar, 3 = somewhat similar, 4 = very similar). The affectual and consensual solidarity items were only asked of a randomly selected 50% of those with living parents. Functional solidarity was assessed by four different dimensions: instrumental support giving, instrumental support receiving, emotional support giving, and emotional support receiving. First, instrumental support giving was measured by aggregating the two items: “During the past month, did you give help to your parents with (a) transportation, errands or shopping?; (b) housework, yard work, repairs or other work around the house?” Second, instrumental support receiving was measured by aggregating the two items: “During the past month, did you receive help from your parents with (a) transportation, errands or shopping?; (b) housework, yard work, repairs or other work around the house?” Third, emotional support giving was measured by an item: “During the past month, did you give advice, encouragement, moral or emotional support to your parents?” Lastly, emotional support receiving was measured by an item: “During the past month, did you receive advice, encouragement, moral or emotional support from your parents?” Each item was coded as a binary variable (1 = yes; 0 = no), and the items were summed such that functional solidarity ranged from 0 to 6.

Covariates

Sociodemographic characteristics, including gender, marital status (married vs non-married), and self-reported health (excellent/very good/good vs fair/poor), educational attainment (years), and total household income ($, square rooted) were included as covariates since they are known predictors of intergenerational solidarity and psychological well-being (Merz et al., 2009). In addition, the number of childhood adversity and parent’s educational attainment (years) were included as covariates to control for other adverse childhood experiences that often co-occur with parental abuse (Felitti et al., 1998). Childhood adversity was assessed by three items: (a) “When you were growing up, that is during your first 18 years, did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic?”, (b) “did you live with both parents most of time up until 1957 (respondents at 18 years old)”, and (c) “up-until you were 18, how often did you see a parent or one of your brothers or sisters get beaten at home?” A sum score the three variables was created by counting the number of yes to the three items, which ranged from 0 to 3. The internal consistency of the measure was very poor (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.40).

Study Sample

The final study sample included respondents who reported having living parents because they responded to a series of items related to intergenerational solidarity. In order to properly assess the effects of childhood abuse caused by the offending parent, this study utilized two samples—one sample examined the relationship with mothers and the other sample examined the relationship with fathers. The relationship with mother sample consisted of 1,371 graduates who reported having living mothers. In this study sample, about half of the sample was male (45.2%, n = 620), and 80% (n = 1,098) were married or had a partner. On average, the respondents had completed 13.7 years of formal education (SD = 2.3), and 83.5% had good, very good, or excellent health status (See Table 1 for further details). The relationship with father sample consisted of 325 graduates who reported having living fathers. In this study sample, half of the sample was male (46.8%, n = 152), and 78.2% (n = 254) were married or had a partner. On average, the respondents had completed 13.9 years of formal education (SD = 2.3), and 81.5% had good, very good, or excellent health status (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, WLS Participants with Living Parents 2004–2005

| Relationship with mother

(N = 1,371) |

Relationship with father

(N = 325) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N/Mean (SD) | %/Min./Max. | N/Mean (SD) | %/Min./Max. |

| Childhood neglect | ||||

| Never neglected | 1,275 | 93.00 | 304 | 93.54 |

| Neglected | 74 | 5.40 | 14 | 4.31 |

| Childhood abuse | ||||

| Never abused | 1,164 | 84.90 | 252 | 77.54 |

| Verbally abused only | 22 | 1.60 | 10 | 3.08 |

| Physically abused only | 79 | 5.76 | 30 | 9.23 |

| Verbally/physically abused | 53 | 3.87 | 20 | 6.15 |

| Associational solidarity | 2.31 (1.03) | 1/4 | 2.05 (0.87) | 1/3 |

| Structural solidarity | 2.33 (0.81) | 1/4 | 2.19 (0.83) | 1/4 |

| Affectual solidarity | 3.51 (0.68) | 1/4 | 3.34 (0.92) | 1/4 |

| Consensual solidarity | 3.03 (0.74) | 1/4 | 3.03 (0.82) | 1/4 |

| Functional solidarity | 1.23 (1.24) | 0/6 | 1.19 (1.27) | 0/5 |

| Psychological well-being | 4.81 (0.63) | 1/6 | 4.75 (0.63) | 2.58/5.97 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 620 | 45.22 | 152 | 46.77 |

| Female | 751 | 54.78 | 173 | 53.23 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 1,098 | 80.09 | 254 | 78.15 |

| Non-married | 272 | 19.84 | 71 | 21.85 |

| Self-reported health | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 1,145 | 83.52 | 265 | 81.54 |

| Fair/poor | 191 | 13.93 | 54 | 16.62 |

| Education (years) | 13.69 (2.33) | 12/20 | 13.89 (2.29) | 12/20 |

| Total household income | 65,881.81 (82,722.68) | 0/710,000 | 73,905.21 (95795.72) | 0/710,000 |

| Childhood adversity | ||||

| 0 | 1,009 | 73.60 | 244 | 75.08 |

| 1 | 279 | 20.35 | 61 | 18.77 |

| 2 | 75 | 5.47 | 16 | 4.92 |

| 3 | 8 | 0.58 | 4 | 1.23 |

| Parent’s education (years) | 10.66 (2.56) | 2/18 | 10.57 (3.15) | 3/21 |

Note: Descriptive statistics are reported prior to multiple imputation. The average age was 65 years (range: 64–67). Associational solidarity was coded as (1) less than once a week, (2) once a week, (3) more than once a week, (4) every day or more. Structural solidarity was coded as (1) 780 miles or more, (2) 30–780 miles, (3) less than 30 miles, (4) living with the parent. Affectual solidarity and consensual solidarity was coded as (1) not at all close/similar, (2) not very close/similar, (3) somewhat close/similar, (4) very close/similar. Functional solidarity was coded as the number of receiving/giving support.

Analytic Strategy

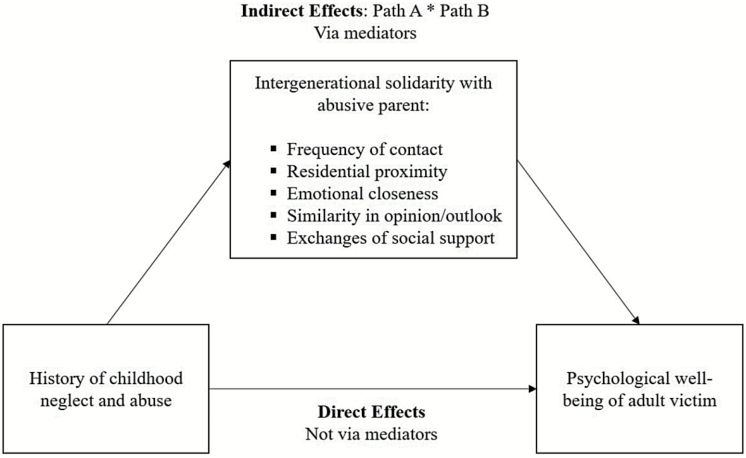

A series of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was performed to estimate the direct effects of childhood neglect and abuse on psychological well-being (Figure 1). In addition, single mediation analyses were performed to estimate the mediational role of five dimensions of intergenerational solidarity with an abusive parent. Mediating effects were computed using the product of the coefficients methods suggested by Preacher and Hayes (2008), which involved the following steps. First, path A coefficient was estimated by regressing intergenerational solidarity with an abusive parent on childhood neglect and abuse. Second, path B coefficient was estimated by regressing psychological well-being on intergenerational solidarity adjusted for childhood neglect and abuse. Lastly, path A and path B coefficients were multiplied to compute the mediational effects of intergenerational solidarity with an abusive parent in the association between childhood maltreatment and psychological well-being. The analyses were performed in Stata version 14 using the sureg and nlcom commands. The nlcom command calculates standard errors using the delta methods (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). All the regression assumptions were met (e.g., normality, linearity, and heteroscedasticity).

Figure 1.

Mediation model.

In terms of missingness, the affectual and consensual solidarity items were only asked to randomly selected 50% of respondents with living parent(s). Without considering these two items that are missing completely at random (MCAR), complete data were provided by 86% in both samples. Childhood abuse had the highest missing frequency in both samples (n = 53, 3.9% for the mother sample; n = 13, 4.0% for the father sample). To address these missing cases, multiple imputation was conducted using the Stata imputation by chained equations procedure by generating twenty imputed datasets (Royston, 2004).

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the key variables (see Supplementary Table 1 for bivariate correlations between all study variables). In the relationship with mother sample, 5.4% of the respondents (n = 74) reported a history of childhood neglect. Approximately 15% of the sample reported a history of parental childhood abuse: 1.6% (n = 22) experienced verbal abuse only, 5.8% (n = 79) experienced physical abuse only, and 3.9% (n = 53) experienced both verbal and physical abuse. In regards to the intergenerational solidarity with mothers, on average, respondents contacted their mothers more than once a week (associational solidarity; M = 2.31, SD = 1.03), and they lived 30–780 miles away from their mothers’ residence (structural solidarity; M = 2.33, SD = 0.81). On average, respondents reported being somewhat close to their mothers (affectual solidarity; M = 3.51, SD = 0.68) and having somewhat similar values or attitudes (consensual solidarity; M = 3.03, SD = 0.74). Also, respondents exchanged one type of social support (e.g., provided emotional support) with their mother (functional solidarity; M = 1.23, SD = 1.24). Descriptive statistics of the relationship with father sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 2 provides the results of OLS regression analyses to examine the direct effects of childhood neglect and abuse on psychological well-being. In the relationship with mother sample, a history of childhood neglect was associated with reduced psychological well-being (b = −0.16, p < .05) after controlling for socio-demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, marital status, educational attainment, self-reported health status, and total household income) and childhood family background (i.e., number of childhood adversity and mother’s educational attainment). However, a history of both verbal and physical abuse was associated with greater psychological well-being (b = 0.23, p < .05). In the relationship with father sample, a history of verbal abuse was associated with reduced psychological well-being (b = −0.53, p < .05). Also, a history of both verbal and physical abuse was associated with reduced psychological well-being (b = −0.34, p < .05).

Table 2.

Direct effects of Childhood Neglect/Abuse on Psychological Well-being

| Relationship with mother (N = 1,371) | Relationship with father (N = 325) | |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological well-being | Psychological well-being | |

| b (SE) | b (SE) | |

| Neglected | −0.16 (0.07)* | −0.23 (0.17) |

| Verbally abused only | −0.14 (0.13) | −0.53 (0.20)* |

| Physically abused only | 0.09 (0.07) | −0.03 (0.12) |

| Verbally and physically abused | 0.23 (0.09)* | −0.34 (0.15)* |

| Male | −0.09 (0.03)** | −0.12 (0.07) |

| Married | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.13 (0.08) |

| Education (years) | 0.03 (0.01)*** | 0.05 (0.02)** |

| Good/excellent health | 0.36 (0.05)*** | 0.39 (0.09)*** |

| Total household income | 0.0004 (0.00)** | −0.001 (0.00) |

| Childhood adversity | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.06) |

| Parent’s education (years) | 0.01 (0.01)* | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Constant | 3.84 (0.12)*** | 3.65 (0.23)*** |

Note: Significance levels are denoted as * p < .05, ** p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 3 provides summary results of the mediation analyses in the relationship with mother sample. Each analysis included socio-demographic characteristics and childhood family background as covariates. The results showed that affectual solidarity and functional solidarity served as significant mediators. First, a history of neglect was associated with lower affectual solidarity with mothers (b = −0.37, p < .001). Also, a history of verbal abuse and/or physical abuse were associated with lower levels of affectual solidarity with mothers (b = −0.41, p < .05; b = −0.65, p < .001, respectively). In turn, affectual solidarity was positively associated with psychological well-being (b = 0.13, p < .01). Based on the products of coefficient methods, affectual solidarity significantly mediated the associations between having been neglected, verbally abused only, and both verbally and physically abused and reduced psychological well-being. Additionally, a history of childhood neglect was associated with lower functional solidarity with mothers (b = −0.44, p < .001). In turn, functional solidarity was positively associated with psychological well-being (b = 0.05, p < .001). The mediational analysis showed that functional solidarity significantly mediated the association between having been neglected and reduced psychological well-being.

Table 3.

Relationship with Mothers: Indirect Effects of Childhood Neglect/Abuse on Psychological Well-Being (PWB) through Solidarity with Abusive Mother (N = 1,317)

| Path A: predicting solidarity | Path B: predicting PWB | Indirect effects: Path A * Path B |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | |

| Associational solidarity as a mediator | |||

| Neglected | −0.21 (0.13) | −0.01 (0.01) | |

| Verbally abused only | 0.11 (0.22) | 0.01 (0.01) | |

| Physically abused only | −0.06 (0.12) | −0.002 (0.01) | |

| Verbally and physical abused | −0.13 (0.15) | −0.01 (0.01) | |

| Associational solidarity | 0.05 (0.02)** | ||

| Structural solidarity as a mediator | |||

| Neglected | −0.11 (0.10) | −0.001 (0.003) | |

| Verbally abused only | 0.08 (0.17) | 0.001 (0.002) | |

| Physically abused only | −0.02 (0.09) | −0.000 (0.001) | |

| Verbally and physical abused | −0.03 (0.12) | 0.000 (0.001) | |

| Structural solidarity | 0.01 (0.02) | ||

| Affectual solidarity as a mediator | |||

| Neglected | −0.37 (0.10)*** | −0.05 (0.02)* | |

| Verbally abused only | −0.41 (0.17)* | −0.10 (0.04)* | |

| Physically abused only | −0.19 (0.11) | −0.003 (0.01) | |

| Verbally and physical abused | −0.65 (0.13)*** | −0.08 (0.03)** | |

| Affectual solidarity | 0.13 (0.04)** | ||

| Consensual solidarity as a mediator | |||

| Neglected | −0.35 (0.12)** | −0.01 (0.02) | |

| Verbally abused only | −0.25 (0.17) | −0.01 (0.02) | |

| Physically abused only | −0.35 (0.12)** | −0.01 (0.01) | |

| Verbally and physical abused | −0.71 (0.15)*** | −0.02 (0.02) | |

| Consensual solidarity | 0.02 (0.03) | ||

| Functional solidarity as a mediator | |||

| Neglected | −0.44 (0.15)** | −0.02 (0.01)* | |

| Verbally abused only | 0.09 (0.26) | 0.001 (0.01) | |

| Physically abused only | 0.028 (0.15) | 0.01 (0.01) | |

| Verbally and physical abused | −0.17 (0.18) | −0.01 (0.01) | |

| Functional solidarity | 0.05 (0.01)*** | ||

Note: Each analysis model controlled for socio-demographic characteristics (gender, marital status, years of education, self-reported health, total household income) and childhood family environment (number of childhood adversity and mother’s education). Significance levels are denoted as *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Bolded letters indicate significant indirect effects and their path coefficients.

In the relationship with father sample, no mediating effects of intergenerational solidarity were found and thus the specific results are not provided. Specifically, either having been neglected or abused was not significantly associated with any of the solidarity constructs with fathers. In the associations between the solidarity and psychological well-being, only the effect of structural solidarity was statistically significant that geographical proximity was associated with less psychological well-being of adult children (b = −0.11, p < .05).

Discussion

The current study emphasized the role of contemporary relationships with an abusive parent when examining the long-term negative influences of childhood maltreatment on psychological well-being in late-adulthood. The intergenerational solidarity literature has shown that even in late adulthood, having a good relationship with one’s parents is beneficial for individual well-being (Fingerman et al., 2013). The study findings suggest that this continued parental influence may apply to adults with a history of childhood maltreatment, and especially so in their relationship with an abusive mother.

Childhood Maltreatment and Psychological Well-being in Late-Adulthood

For the first hypothesis, that a history of childhood neglect and abuse was associated with diminished psychological well-being among adult children, there was partial support. Consistent with existing literature (Greenfield & Marks, 2010), a history of verbal abuse and/or physical abuse was associated with diminished psychological well-being in the relationship with father sample. In the relationship with mother sample, a history of neglect was associated with diminished psychological well-being. For an enhanced understanding, future research may examine the effect of parental childhood abuse on distinct subdimensions of psychological well-being, such as positive growth or self-acceptance, and its potential impact on important life domains, such as interpersonal relationships or work performance.

Unexpectedly, results indicated that verbally and physically abused from mothers was positively associated with psychological well-being. According to the bivariate correlational analysis between childhood abuse and each individual item of the psychological well-being measure, verbally and physically abused from mothers was positively correlated with some of the personal growth items, such as “to what extent do you agree that you think it is important to have new experiences that challenge how you think about yourself and the world?” This may reveal signs of resilience or post-traumatic growth that positive change can result from one’s struggle with a life challenge or even a traumatic event (Calhoun & Tedeschi, 2001). Alternatively, the physical abuse measure may have captured the experience of corporal punishment, such as spanking or grabbing. According to Lansford and colleagues (2010), some mothers who used corporal punishment believed that physical discipline was needed to bring up (educate) their child properly. Also, psychosocial impact of corporal punishment has mixed findings (Gershoff, 2002). Therefore, some adult children may have interpreted their mothers’ parenting behaviors as part of discipline, which could have led to the positive association between childhood abuse and psychological well-being. For a better interpretation of the result, future research should systematically investigate the effects of parent gender in regards to long-term mental health consequences.

Mediational Role of Affectual Solidarity and Functional Solidarity

There was also support for the second hypothesis, that affectual solidarity and functional solidarity significantly mediated the association between maternal childhood maltreatment and psychological well-being. Specifically, having been neglected, having been verbally abused, and having been both verbally and physically abused were all associated with diminished psychological well-being through affectual solidarity (i.e., emotional closeness). This result indicates that the residual impact of mothers’ neglectful and abusive treatment may inhibit their adult children’s emotional closeness to them, and this lack of cohesion was predictive of their negative psychological well-being. Savla and colleagues (2013) showed that parental childhood abuse diminished emotional closeness with family members when the victims reached mid- or late-adulthood. The current study extends this earlier finding by demonstrating that less-cohesive relationships with mothers, due to past abuse, could eventually undermine psychological well-being of adult children. Notably, this result is contrast with the direct positive association between maternal verbal and physical abuse and psychological well-being. This may indicate that some abused adults seem to function well in their adult lives as represented by higher levels of psychological well-being, but when it comes to the relationships with abusive mothers, they struggle. This phenomenon could stem from the persistence of unresolved issues from past abuse or even, perhaps, the continuity of abuse from the mother. Alternatively, adult children may continue to seek self-validation, even possibly attached relationships, from the abusive mother as a way to compensate for their unmet affective needs from childhood. Furthermore, functional solidarity was another significant mediator: Having been neglected was associated with less frequent exchanges of social support with aging mothers, which was ultimately associated with diminished psychological well-being. The benefits of mutual support across generations have been identified through extensive literature (Bengtson et al., 2002; Silverstein et al., 2012), and the current study shows that adults with a history of childhood neglect may be less prone to experiencing these benefits.

It is also important to note that, in the relationship with father sample, fathers’ neglect and abuse were directly associated with diminished psychological well-being, but none of the five dimensions of solidarity mediated this relationship. This result may imply that a contemporary relationship with fathers is not as crucial as the relationship with mothers in terms of its impact on psychological well-being. This finding could reflect the theory of attachment, which posits that the relationship with mothers, who are primary caregivers in most cases, matters more in terms of a child’s developmental outcomes (Parkes, Stevenson-Hinde, & Marris, 2006), and the current study suggests that this pattern might persist well into late adulthood.

Further investigation is need to better understand the relational dynamics between adults with a history of childhood maltreatment and their family of origin including their abusive parent. Relatedly, future research should scrutinize the caregiving experiences of these abused adults: the speculation is that providing care to an abusive mother could be particularly stressful considering current relational quality with the mother (Kong & Moorman, 2015, 2016).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, childhood maltreatment was measured by self-reported retrospective questions, which may involve recall errors or underreporting issues (Fallon et al., 2010). This self-reported retrospective nature of this measure may explain the discrepancy between the estimates of childhood maltreatment in this study and the general population (e.g., 9.2 victims per 1,000 children; NCANDS, 2016). In addition, although the neglect item was derived from the well-validated measure of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein et al., 1994), it was a single-item measure that only captured the emotional aspect of neglect. It should also be noted that the neglect item was not specific to each parent but rather indicative of both parents. However, the recollection of childhood abuse and neglect still suffices as a measure because it represents adult children’s perceptions and assessments of the past relationship quality between them and their parents. Future research should incorporate a prospective research design to better assess the long-term consequences of childhood maltreatment for later-life relationships. Second, normative solidarity was not involved in these analyses because of the unavailability of items that could measure it in the WLS. Future research may explore the effect of childhood maltreatment on this obligatory aspect of the parent–child relationship because normative solidarity plays an important role facilitating other solidarity dimensions (Parrott & Bengtson, 1999). Lastly, it should be noted that the majority of the WLS sample consists of non-Hispanic whites who completed at least a high school education. Therefore, the study findings may not be representative of ethnic or racial minorities, including African American, Hispanic, or Asian individuals, or those with less than a high school education.

Implications

Despite the limitations, this study makes significant contributions to the existing literature. First, much of the previous literature on childhood maltreatment within intergenerational relationships only focuses on the child victim until he/she reaches adolescence (Trickett, Negriff, Ji, & Peckins, 2011). In this regard, the current study extends the scope of the previous research by examining childhood maltreatment impacts on intergenerational relationships in the later stages of life. In addition, intergenerational solidarity research has focused on the issues related to parent–adult child relationships in general, most of which are presumably functional (Bengtson, 1996). The current study adds new knowledge to the intergenerational solidarity literature by examining how a history of childhood maltreatment might be linked to diverse aspects of later-life intergenerational relationships. Furthermore, the current study advances the existing knowledge base that a history of childhood maltreatment not only has a negative impact on social relationships, such as with peers or intimate partners (Paradis & Boucher, 2010), but can also undermine the relationship quality with the aging parent.

This study provides important implications for practice. When intervening in the lives of adults with a history of childhood maltreatment, practitioners should assess the quality of contemporary relationships with the abusive mother and create intervention plans based on those assessments. Interventions should focus on addressing unresolved emotional issues from past abuse in contemporary interactions with the abusive mother. Also, it is important for practitioners to be aware that providing care to older parents can be particularly challenging when there is a history of neglect/abuse. Therefore, practitioners should provide tailored support to adults with a history of such experiences by taking into account both this history and the contemporary dynamics with the abusive parent.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study is a part of the author’s doctoral dissertation at Boston College and the author would like to thank dissertation committee members: Drs James Lubben, Sara M. Moorman, and Scott D. Easton. The author is especially grateful for Dr Sara M. Moorman who provided wonderful guidance on developing and writing the earlier draft of this manuscript. The author also would like to thank Dr Lynn M. Martire for reviewing the current version of the manuscript. This study was partially supported by the National Institute on Aging Grant T32 AG049676 to The Pennsylvania State University.

References

- Abbott R. A., Ploubidis G. B., Huppert F. A., Kuh D., Croudace T. J. (2010). An evaluation of the precision of measurement of Ryff’s psychological well-being scales in a population sample. Social Indicators Research, 97, 357–373. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9506-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson V. L. (1996). Continuities and discontinuities in intergenerational relationships over time. In V., Bengtson (Eds.), Adulthood and aging: Research on continuities and discontinuities (pp. 271–307). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson V. L. Giarrusso R. Mabry J., & Silverstein M (2002). Solidarity, conflict, and ambivalence: Complementary or competing perspectives on intergenerational relationships?Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 568–576. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00568.x [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D. P. Fink L. Handelsman L. Foote J. Lovejoy M. Wenzel K., … Ruggiero J (1994). Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1132–1136. doi:10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun L. G., & Tedeschi R. G (2001). Posttraumatic growth: The positive lessons of loss. In R. A., Neimeyer (Ed.), Meaning reconstruction and the experience of loss. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Campton J., & Pollak R. A (2009). Proximity and coresidence of adult children and their parents: Description and correlates (Working Paper No. 2009–215). Retrieved from University of Michigan Retirement Research Center website: http://www.mrrc.isr.umich.edu/publications/papers/pdf/wp215.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Elder G. H. (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fallon B., Trocmé N., Fluke J., MacLaurin B., Tonmyr L., Yuan Y. Y. (2010). Methodological challenges in measuring child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34, 70–79. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V. J., Anda R. F., Nordenberg D., Williamson D. F., Spitz A. M., Edwards V.,…, Marks J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D. M., Horwood L. J. (1998). Exposure to interparental violence in childhood and psychosocial adjustment in young adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22, 339–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman K. L., Sechrist J., Birditt K. (2013). Changing views on intergenerational ties. Gerontology, 59, 64–70. doi:10.1159/000342211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 539–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J. G., McLaughlin K. A., Berglund P. A., Gruber M. J., Sampson N. A., Zaslavsky A. M., Kessler R. C. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67, 113–123. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield E. A., Marks N. F. (2010). Identifying experiences of physical and psychological violence in childhood that jeopardize mental health in adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34, 161–171. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl T. I. Klika J. B. Herrenkohl R. C. Russo M. J., & Dee T (2012). A prospective investigation of the relationship between child maltreatment and indicators of adult psychological well-being. Violence and Victims, 27, 764–776. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.27.5.764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J., & Moorman S. M (2016). History of childhood abuse and intergenerational support to mothers in adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 926–938, doi:10.1111/jomf.12285 [Google Scholar]

- Kong J., Moorman S. M. (2015). Caring for my abuser: childhood maltreatment and caregiver depression. The Gerontologist, 55, 656–666. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford J. E., Alampay L. P., Al-Hassan S., Bacchini D., Bombi A. S., Bornstein M. H.,…, Zelli A. (2010). Corporal punishment of children in nine countries as a function of child gender and parent gender. International journal of pediatrics, 2010, 672780. doi:10.1155/2010/672780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton L. Silverstein M., & Bengton V (1994). Affection, social contact, and geographic distance between adult children and their parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56, 57–68. doi:10.2307/352701 [Google Scholar]

- Merz E. Consedine N. Schulze H., & Schuengel C (2009). Wellbeing of adult children and ageing parents: associations with intergenerational support and relationship quality. Ageing and Society, 29, 783–802. doi:10.1017/S0144686X09008514 [Google Scholar]

- National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) (2016). Child maltreatment 2015. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Paradis A., & Boucher S (2010). Child maltreatment history and interpersonal problems in adult couple relationships. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 19, 138–158. doi:10.1080/10926770903539433 [Google Scholar]

- Parker E. O. Maier C., & Wojciak A (2016). Childhood abuse and family obligation in middle adulthood: Findings from the MIDUS II National Survey. Journal of Family Therapy. doi:10.1111/1467–6427.12114 [Google Scholar]

- Parkes C. M. Stevenson-Hinde J., & Marris P (2006). Attachment across the life cycle. New York, NY: Tavistock/Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott T., & Bengtson V. L (1999). The effects of earlier intergenerational affection, normative expectations, and family conflict on contemporary exchanges of help and support. Research on Aging, 21, 73–105. doi:10.1177/0164027599211004 [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K. J., Hayes A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti R. L., Taylor S. E., Seeman T. E. (2002). Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 330–366. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.128.2.330 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C. D., Keyes C. L. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719–727. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. (2004). Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata Journal, 4, 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Savla J. T., Roberto K. A., Jaramillo-Sierra A. L., Gambrel L. E., Karimi H., Butner L. M. (2013). Childhood abuse affects emotional closeness with family in mid- and later life. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37, 388–399. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setterstein R. A. (2015). Relationships in time and the life course: The significance of linked lives. Research in Human Development, 12, 217–223. doi:10.1080/15427609.2015.1071944 [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M. Conroy S. J., & Gans D (2012). Beyond solidarity, reciprocity and altruism: Moral capital as a unifying concept in intergenerational support for older people. Ageing and Society, 32, 1246–1262. doi:10.1017/S0144686X1200058X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperry D. M., Widom C. S. (2013). Child abuse and neglect, social support, and psychopathology in adulthood: A prospective investigation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37, 415–425. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus M. A. Gelles R. J., & Steinmetz S. K (1980). Behind closed doors: Violence in the American family. New York: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple M. L. Skibo M. A., & Davies P. T (2012). Impact of parental conflict and emotional abuse on children and families. Partner Abuse, 3, 379–400. doi:10.1891/1946-6560.3.3.379 [Google Scholar]

- Trickett P. K. Negriff S. Ji J., & Peckins M (2011). Child maltreatment and adolescent development. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 3–20. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00711.x [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. (1992). Relationships between adult children and their parents: Psychological consequences for both generations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54, 664–674. doi:10.2307/353252 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.