Abstract

Objective

To assess whether randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that were registered were less likely to report positive study findings compared with RCTs that were not registered and whether the association varied by funding source.

Design

Cross sectional study.

Study sample

All primary RCTs published in December 2012 and indexed in PubMed by November 2013. Trial registration was determined based on the report of a trial registration number in published RCTs or the identification of the trial in a search of trial registries. Trials were separated into prospectively and retrospectively registered studies.

Main outcome measure

Association between trial registration and positive study findings.

Results

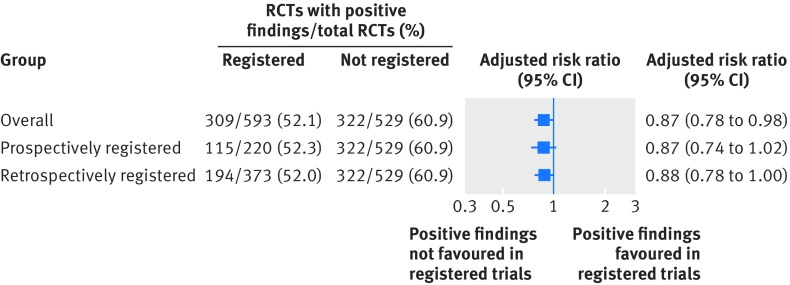

1122 eligible RCTs were identified, of which 593 (52.9%) were registered and 529 (47.1%) were not registered. Overall, registration was marginally associated with positive study findings (adjusted risk ratio 0.87, 95% confidence interval 0.78 to 0.98), even with stratification as prospectively and retrospectively registered trials (0.87, 0.74 to 1.03 and 0.88, 0.78 to 1.00, respectively). The interaction term between overall registration and funding source was marginally statistically significant and relative risk estimates were imprecise (0.75, 0.63 to 0.89 for non-industry funded and 1.03, 0.79 to 1.36 for industry funded, P interaction=0.046). Furthermore, a statistically significant interaction was not maintained in sensitivity analyses. Within each stratum of funding source, relative risk estimates were also imprecise for the association between positive study findings and prospective and retrospective registration.

Conclusion

Among published RCTs, there was little evidence of a difference in positive study findings between registered and non-registered clinical trials, even with stratification by timing of registration. Relative risk estimates were imprecise in subgroups of non-industry and industry funded trials.

Introduction

Clinical trial registration is a key method used to improve accountability in the conduct and reporting of research.1 The rationale is that transparency can be improved by registering the trial design in the public domain before reporting results. Researchers and the general public can then have access to a comprehensive list of completed and ongoing trials and can compare the prespecified details in the register with those in the published study.2 3

A small study of published reports of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in cardiology showed that trials that were reported as registered were less likely to report positive study findings.4 The study was limited by focusing on cardiology. A meta-epidemiological study also found a trend towards larger treatment effects in trials that were not registered or were retrospectively registered.5 Neither study examined its results based on the funding source of the trial.4 5

We conducted a detailed study of primary reports of RCTs published in December 2012 in PubMed indexed journals, without restriction by journal, disease, or specialty. We sought to examine the association between trial registration and positive study findings and whether this relation varied by funding source (industry versus non-industry funding).

Methods

Study sample and data extraction

This analysis was part of a larger study on the epidemiology and quality of reporting of RCTs4 6 7 We used a modified version of the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy (phase 1 with added terms: “cross-over studies” and “multicentre study”) to identify primary reports of RCTs published in December 2012 and indexed in PubMed by 17 November 2013.8 9 The web appendix shows the full search strategy. RCTs were defined as prospective studies that assessed healthcare interventions in human participants, or groups of participants, who were randomly allocated to study interventions. We excluded cost effectiveness analyses, interim analyses, diagnostic studies, pharmacokinetic studies, pharmacodynamic studies, and physiology studies.

We reviewed the titles and abstracts of retrieved records in duplicate. The full text of studies identified in the title and abstract screen were reviewed. Data extraction was done for general trial characteristics (number of study centres, study design, number of arms, and number of participants randomised in the trial). We also extracted details on funding source. Trials that were solely or partially funded by commercial sources, irrespective of the size of the contribution, were classified as industry funded. In addition, if commercial sponsors provided the trial with an investigational agent without charge, we classified the trial as industry funded. This classification was used even if the sponsor was not involved in other aspects of the study. Box 1 defines the methodological items. A pool of eight reviewers independently extracted data in duplicate. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by a reviewer who did not perform the original extraction. We applied no language restrictions when conducting the search. Full texts of studies published in languages other than English were reviewed and extracted once by the same person (AJH) where possible.

Box 1. Definitions used to assess methodological quality of publications of RCTs.

Primary outcome

Primary outcome defined explicitly or an outcome used in sample size calculation; or a main outcome described explicitly in primary study objectives: yes or no

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculation stated to have been undertaken: yes or no

Random sequence generation

Method used to allocate participants to study groups: computer, random number table, coin toss, not reported or inadequate, other

Allocation concealment

Method used to prevent the individual enrolling participants from knowing or predicting the allocation sequence in advance: envelope, central, pharmacy, not reported or inadequate, other

Blinding, how?

Method used to prevent participants, caregivers, investigators, or outcomes assessors from knowing the intervention a participant received. Trial is unblinded if explicitly stated as such or blinding not possible: blinded, details given, blinded, no details, unblinded, or not reported

Blinding, who?

Reported, details given (eg, patient, caregiver), reported, no details given (eg, double blinded), unblinded, or unclear

Attrition

Loss to follow-up reported for each group: yes, details given, yes, details not given, or no

Intention to treat

Reported as having been analysed in their assigned groups: intention to treat, or no intention to treat

Exposure and outcomes

Trials were coded as registered if this was stated in the published study and a trial registration number was provided. As recommended during peer review, we additionally searched trial registries for trials that were not reported as registered or did not provide a trial registration number in the published article. We searched the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP), the EU Clinical Trials Register, clinicaltrials.gov, and the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) Registry. The search was conducted using the following search strategy: the title of the trial; the name of the principal investigator or a combination of keywords (eg, the intervention name, health condition, trial identifier), or both.10 We matched results in trial registries with published articles based on the name of trial investigators, the sample size of the trial, the number of study arms, and the types of interventions used in the trial. Finally, we reviewed the trial registry entry to obtain details about the timing of registration and the timing of study commencement. RCTs that were registered before or within one month of study commencement were coded as prospectively registered to be consistent with the Food and Drug Administration requirement on trial registration. Where only the month and year of study commencement were provided in the trial registry without listing the specific day, we assumed it was the first day of the month. All remaining RCTs that were registered with a trial registration number were coded as retrospectively registered.

Trials were coded as having positive study findings if an investigator defined primary outcome in the trial publication was statistically significant (effect estimate with confidence interval that does not cross the line of no effect or a P<0.05) in favour of the experimental intervention. If studies were non-inferiority trials, they were coded as having positive study findings if there was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and control interventions. If studies had multiple primary outcomes, we assessed each outcome and if at least one was statistically significant, we coded the study as having positive study findings. If no primary outcome was reported, we assessed the main outcome that was emphasised in the abstract and results for statistical significance. Classification of trial registration status and study outcomes was performed separately in two independent phases of data extraction.

Our primary analysis was to assess an association between trial registration and positive study findings. We assessed trial registration as an overall exposure and stratified by prospective and retrospective registration. We additionally assessed whether the association between reporting of trial registration and positive study findings varied by funding source (industry versus non-industry funding) through a test for interaction.

Data analysis

We generated summary statistics for the general characteristics and methodological quality of RCTs included in our study. The χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables and the t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare continuous variables. Although we initially used logistic regression, the percentage of RCTs with positive study findings was more than 50%. It is therefore likely that the odds ratio will overestimate the risk ratio and overestimate the association between trial registration and positive study findings. We therefore used multivariable Poisson regression with robust standard errors to obtain risk ratios and to assess the association between reporting of trial registration and positive findings. The Poisson regression model was adjusted for variables that have been shown to affect study findings,11 12 including study sample size (continuous) and funding source (industry funded versus non-industry funded versus unclear), random sequence generation (yes versus not reported), allocation concealment (yes versus not reported), type of intervention (pharmacological versus non-pharmacological), and number of centres (single versus multiple versus unclear). To assess for consistency of the association by funding source, we tested for an interaction between trial registration and study funding (non-industry funded versus industry funded). If a statistically significant interaction was found, we examined the estimates for the association between reporting of trial registration and positive study findings within the relevant subgroups of funding.

In a sensitivity analysis, we included trials with unclear funding in the regression model to test for an interaction by funding source. We also excluded trials that were not registered in a WHO primary registry. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted with R Statistical Software (3.2.0) and Stata 14.

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

Results

General characteristics and reporting of methodological items in the overall cohort

The search yielded 4190 abstracts, of which 1676 were included in the full text review (fig 1). Of these, 1111 full text articles met the inclusion criteria. Eleven articles included two independent trials, thereby increasing the total number of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to 1122. Three hundred trials (26.7%) were single centre, 298 (26.6%) were multicentre, and 524 (46.7%) had an unclear number of centres (table 1). With respect to design characteristics, 953 trials (84.9%) were parallel group studies and 892 (79.5%) had two intervention arms (table 1). The median sample size was 86 (interquartile range 43-193) and 513 trials (45.7%) were non-industry funded, compared with 302 trials (26.9%) and 307 trials (27.4%) that were solely or partly industry funded or had unclear funding, respectively (table 1). The RCTs were published in 543 unique journals. The median impact factor was 3 (interquartile range 2-5) and only 34 of 1122 (3.0%) were published in general medical journals (New England Journal of Medicine, Lancet, Journal of the American Medical Association, The BMJ, Annals of Internal Medicine, and PloS Medicine). Two hundred and sixty eight RCTs (23.9%) were published in journals endorsed by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) (table 1).

Fig 1.

Identification of included studies

Table 1.

General characteristics of included studies

| Characteristics | Overall (n=1122) (No, col %) | Not registered (n=529) (No, row %) | Registered (n=593) (No, row %) | P value | Prospectively registered (n=220) (No, row %)* | Retrospectively registered (n=373) (No, row %)* | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study centres: | |||||||

| Single | 300 (26.7) | 157 (52.3) | 143 (47.7) | <0.001 | 43 (14.3) | 100 (33.3) | <0.001 |

| Multiple | 298 (26.6) | 65 (21.8) | 233 (78.2) | 111 (37.3) | 122 (40.9) | ||

| Unclear | 524 (46.7) | 307 (58.6) | 217 (41.4) | 66 (12.6) | 151 (28.8) | ||

| Design: | |||||||

| Parallel group | 953 (84.9) | 442 (46.4) | 511 (53.6) | 0.24 | 188 (19.7) | 323 (33.9) | 0.36 |

| Cluster | 31 (2.8) | 14 (45.2) | 17 (54.8) | 4 (12.9) | 13 (41.9) | ||

| Crossover | 98 (8.7) | 48 (49.0) | 50 (51.0) | 22 (22.5) | 28 (28.6) | ||

| Other | 40 (3.6) | 25 (62.5) | 15 (37.5) | 6 (15.0) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| No of arms: | |||||||

| 2 | 892 (79.5) | 424 (47.5) | 468 (52.5) | 0.03 | 170 (19.1) | 298 (33.4) | 0.08 |

| 3 | 146 (13.0) | 65 (44.5) | 81 (55.5) | 35 (24.0) | 46 (31.5) | ||

| 4 | 61 (5.4) | 35 (57.4) | 26 (42.6) | 10 (16.4) | 16 (26.2) | ||

| >4 | 23 (2.1) | 5 (21.7) | 18 (78.3) | 5 (21.7) | 13 (56.5) | ||

| Median (interquartile range) sample size (No of randomised participants) | 86 (43-193) | 66 (39-144) | 105 (51-254) | <0.001 | 117 (59-296) | 100 (48-232) | <0.001 |

| Funding: | |||||||

| Non-industry | 513 (45.7) | 249 (48.5) | 264 (51.5) | <0.001 | 79 (15.4) | 185 (36.1) | <0.001 |

| Solely or partly industry | 302 (26.9) | 65 (21.5) | 237 (78.5) | 117 (38.7) | 120 (39.7) | ||

| Unclear | 307 (27.4) | 215 (70.0) | 92 (30.0) | 24 (7.8) | 67 (22.2) | ||

| Journal specific variables | |||||||

| Median (interquartile range) impact factor | 3 (2-5) | 2 (1-3) | 4 (2-6) | <0.001 | 5 (3-8) | 3 (2-5) | <0.001 |

| General medical journals*: | |||||||

| Yes | 34 (3.0) | 1 (3.0) | 33 (97.1) | <0.001 | 21 (61.8) | 12 (35.3) | <0.001 |

| No | 1088 (97.0) | 528 (48.5) | 560 (51.5) | 199 (18.3) | 361 (33.2) | ||

| ICMJE endorsed: | |||||||

| Yes | 268 (23.9) | 84 (31.3) | 184 (68.7) | <0.001 | 81 (30.2) | 103 (38.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 854 (76.1) | 445 (52.1) | 409 (47.9) | 139 (16.3) | 270 (31.6) | ||

ICMJE=International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Percentages obtained from 3×2 table including trials prospectively registered, retrospectively registered, and not registered.

Generated from χ2 test comparing proportion of trials prospectively registered, retrospectively registered, and not registered.

Sample size calculations were reported in 622 trial publications (55.4%) and the primary outcome was defined in 779 trials (69.4%) (table 2). Only 567 trial publications (50.5%) and 391 (34.8%) trial publications reported the method for random sequence generation and allocation concealment, respectively (table 2). Eight hundred and sixty two trial publications (76.8%) and 858 trial publications (76.5%) reported the method used for blinding and who was blinded, respectively (table 2). Finally, loss to follow-up for each study group was reported in 745 trials publications (66.4%) and an intention to treat analysis was reported in 312 trial publications (27.8%, table 2).

Table 2.

Methodological items of included studies

| Items | Overall (n=1122) (No, col %) | Not registered (n=529) (No, row %) | Registered (n=593) (No, row %) | P value | Prospectively registered (n=220) (No, row %)* | Retrospectively r (n=373) (No, row %)* | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defined primary outcome reported: | |||||||

| Yes | 779 (69.4) | 256 (32.9) | 523 (67.1) | <0.001 | 200 (25.7) | 323 (41.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 343 (30.6) | 273 (79.6) | 70 (20.4) | 20 (5.8) | 50 (14.6) | ||

| Sample size calculation reported: | |||||||

| Yes | 622 (55.4) | 195 (31.4) | 427 (68.6) | <0.001 | 159 (25.6) | 268 (43.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 500 (44.6) | 334 (66.8) | 166 (33.2) | 61 (12.2) | 105 (21.0) | ||

| Random sequence generation: | |||||||

| Computer | 456 (40.6) | 169 (37.1) | 287 (62.9) | <0.001 | 109 (23.9) | 178 (39.0) | <0.001 |

| Random number table | 69 (6.2) | 44 (63.8) | 25 (36.2) | 3 (4.4) | 22 (31.9) | ||

| Not reported or inadequate | 555 (49.5) | 288 (51.9) | 267 (48.1) | 103 (18.6) | 162 (29.6) | ||

| Other | 42 (3.7) | 28 (66.7) | 14 (33.3) | 5 (11.9) | 9 (21.4) | ||

| Allocation concealment: | |||||||

| Envelope | 209 (18.6) | 91 (43.5) | 118 (56.5) | <0.001 | 24 (11.5) | 94 (45.0) | <0.001 |

| Central | 100 (8.9) | 12 (12.0) | 88 (88.0) | 48 (48.0) | 40 (40.0) | ||

| Pharmacy | 44 (3.9) | 9 (20.5) | 35 (79.5) | 18 (40.9) | 17 (38.6) | ||

| Not reported or inadequate | 731 (65.2) | 402 (55.0) | 329 (45.0) | 125 (17.1) | 204 (27.9) | ||

| Other | 38 (3.4) | 15 (39.5) | 23 (60.5) | 5 (13.2) | 18 (47.4) | ||

| Blinding, how?: | |||||||

| Blinded, details given | 265 (23.6) | 94 (35.5) | 171 (64.5) | <0.001 | 73 (27.6) | 98 (37.0) | <0.001 |

| Blinded, no details given | 416 (37.1) | 172 (41.5) | 244 (58.7) | 97 (23.3) | 147 (35.3) | ||

| Unblinded | 181 (16.1) | 94 (51.9) | 87 (48.1) | 20 (11.1) | 67 (37.0) | ||

| Not reported | 260 (23.2) | 169 (65.0) | 91 (35.0) | 30 (11.5) | 61 (23.5) | ||

| Blinding, who?: | |||||||

| Reported, details given | 507 (45.2) | 210 (41.4) | 297 (58.6) | <0.001 | 115 (22.7) | 182 (35.9) | <0.001 |

| Reported, no details given | 170 (15.2) | 52 (30.6) | 118 (69.4) | 55 (32.4) | 63 (37.1) | ||

| Unblinded | 181 (16.1) | 94 (51.9) | 87 (48.1) | 20 (11.1) | 67 (37.0) | ||

| Unclear | 264 (23.5) | 173 (65.5) | 91 (34.5) | 30 (11.4) | 61 (23.1) | ||

| Attrition: | |||||||

| Yes, details given | 625 (55.7) | 202 (32.3) | 423 (67.7) | <0.001 | 168 (26.9) | 255 (40.8) | <0.001 |

| Yes, details not given | 120 (10.7) | 57 (47.5) | 63 (52.5) | 18 (15.0) | 45 (37.5) | ||

| No | 377 (33.6) | 270 (71.6) | 107 (28.4) | 34 (9.0) | 73 (19.4) | ||

| Intention to treat: | |||||||

| Intention to treat | 312 (27.8) | 74 (23.7) | 238 (76.3) | <0.001 | 87 (27.9) | 151 (48.4) | <0.001 |

| No intention to treat | 810 (72.2) | 455 (56.2) | 355 (43.8) | 133 (16.4) | 222 (27.4) |

Percentages from 3×2 table including trials prospectively registered, retrospectively registered, and not registered.

Generated from χ2 test comparing proportion of trials prospectively registered, retrospectively registered, and not registered.

Characteristics of trials based on registration

Overall, 529 RCTs (47.1%) were not reported as registered in the publication and 593 RCTs (52.9%) were registered. Of the registered trials, 222 (37.4%) were registered prospectively and 373 (62.9%) retrospectively.

Trials that were registered were more likely to be multicentre, have a larger sample size, and be industry funded (table 1). They were also more likely to be published in general medical journals and in journals endorsed by the ICMJE (table 1). Trials that were registered were more likely to specify a primary outcome and provide details about sample size calculations, random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, and attrition (table 2). They were also more likely to report an intention to treat analysis (table 2).

Positive study findings

Among the 529 RCTs that were not registered, 322 (60.9%) reported a positive study finding compared with 309 of the 593 RCTs (52.1%) that were registered.

In an unadjusted analysis, trials that were registered were less likely to report a positive study finding (risk ratio 0.86, 95% confidence interval 0.77 to 0.95). The association was marginally statistically significant after multivariable adjustment (adjusted risk ratio 0.87, 0.78 to 0.98, fig 2 and table 1 in the web appendix). Similar findings were obtained when the RCTs that were registered were stratified into retrospectively and prospectively registered studies (fig 2 and table 1 in the web appendix).

Fig 2.

Association between reporting of trial registration and positive study findings. RCT=randomised controlled trial

The interaction between trial registration and funding source was marginally significant (P interaction=0.046 for non-industry versus solely or partly industry funded studies, table 3). Among non-industry funded studies, registered trials (overall) were less likely to report positive study findings compared with trials that were not registered (adjusted risk ratio 0.75, 0.63 to 0.89, table 1 in the web appendix). In contrast, an association between trial registration and positive study findings was not found among industry funded studies (adjusted risk ratio 1.03, 0.79 to 1.36 for overall registration, table 1 in the web appendix). The test for interaction was not statistically significant when studies were stratified by prospective and retrospective registration (table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis for association between reporting of trial registration and positive study findings

| Funding source | Any registration v not registered | Prospective registration v not registered | Retrospective registration v not registered | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs with positive findings/all RCTs (%) | Adjusted risk ratio (95% CI) | P value interaction | RCTs with positive findings/all RCTs (%) | Adjusted risk ratio (95% CI) | P value interaction | RCTs with positive findings/all RCTs (%) | Adjusted risk ratio (95% CI) | P value interaction | |||

| Non-industry funded | Registered: 122/264 (46.2) not registered§: 155/249 (62.2) | 0.75 (0.63 to 0.89) | 0.046 | Registered: 37/79 (46.8) not registered: 155/249 (62.2) | 0.75 (0.58 to 0.97) | 0.110 | Registered: 85/185 (45.9) not registered: 155/249 (62.2) | 0.75 (0.62 to 0.90) | 0.074 | ||

| Solely or partly industry funded | Registered: 127/237 (53.5) not registered: 35/65 (53.8) | 1.03 (0.79 to 1.36) | Registered: 63/117 (53.8) not registered: 35/65 (53.8) | 1.06 (0.78 to 1.45) | Registered: 64/120 (53.3) not registered: 35/65 (53.8) | 1.02 (0.76 to 1.35) | |||||

RCT=randomised controlled trial.

Sensitivity analysis

If trials with unclear funding were included in the regression model to test whether the association between trial registration and positive study findings varied between non-industry and industry funded trials, the P value for the test of interaction was 0.053 and strata specific relative risk estimates were unchanged. The interaction terms for trial registration and positive study findings were statistically significant for non-industry funded studies versus studies with unclear funding (P interaction=0.005). However, this was not a prespecified subgroup comparison and was not examined further. Five trials were registered but not in a WHO primary registry (eg, Hong Kong University Clinical Trial Registry). When these trials were excluded, our overall results were unchanged and the test for interaction comparing non-industry and industry funded trials was not significant (P interaction=0.05) and strata specific relative risk estimates were unchanged.

Discussion

In an analysis of 1122 published randomised controlled trials (RCTs), there was little evidence of a difference in positive study findings between registered and non-registered clinical trials, nor when trials were stratified as prospectively registered and retrospectively registered. Subgroup analyses were inconclusive as to whether the association between trial registration and positive study findings varied between non-industry funded and industry funded trials.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

The major strength of our study is its large sample size, which allowed us to examine trial registration in important subgroups. We also examined all trials published and indexed in PubMed within a one month period, which enhances the generalisability of our findings.

Our study also has limitations. Firstly, by sampling a one month period in PubMed, we inherently included trials across the spectrum of medical journals. Therefore, the quality of reporting in several trials was poor. However, we accounted for differences in the quality of reporting in registered and non-registered trials through the use of multivariable regression. Secondly, 25% of the studies included in our analysis had unclear funding sources. This limited the number of non-industry and industry funded trials we were able to identify in our analysis and contributed to imprecise relative risk estimates. None the less, the sample sizes of our subgroups were comparable to, if not larger than, the total number of trials in each of the previous methodological studies examining whether trial registration was associated with positive study findings.4 5 13 Thirdly, we analysed trials published in 2012 and it is likely that many of these studies were initiated well before then. Trial registration practices and patterns may have changed over the time that trials in our analysis were initiated and conducted. However, trial registration is now prevalent and it would be more difficult to assess the association between trial registration and positive study findings with a more contemporary cohort of clinical trials. Finally, our analysis relied on reported information in trial publications and it is unclear whether this is reflective of the prespecified trial design and conduct. We were also unable to account for unpublished studies, which may differ from the published literature. Future studies should focus on gaining access to clinical trial protocols and comparing the rate of positive primary outcomes in registered and non-registered clinical trials.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

Trial registration was introduced as a method to improve transparency and accountability in research, yet evidence as to whether trials that are registered are less likely to report positive study findings is limited. Existing studies on the association between trial registration and positive study findings are restricted to a small cross sectional study of cardiovascular trials and a meta-epidemiological study. In neither study was the analysis examined based on the funding source of the trial.

By examining a large unselected group of trials, irrespective of medical specialty, journal, intervention type, or disease type, we found little evidence of an association between trial registration and positive study findings in the overall analysis. Firstly, RCTs that were registered were less likely to report positive study findings compared with RCTs that were not registered, but the risk ratio estimates were modest and the 95% confidence intervals were close to the line of no effect. When stratified by the timing of trial registration, there was little evidence of a difference in positive study findings between prospectively registered trials and non-registered trials, but the association for retrospective registration was statistically significant. We noted that the association between trial registration and positive study findings may vary between non-industry and industry funded trials. Although the test for interaction was statistically significant, the relative risk estimates were imprecise therefore limiting any clear conclusions.

In addition to the limited evidence for an association between trial registration and study findings, the quality of reporting in the trials included in our analysis was poor. In particular, important methodological items such as the method for random sequence generation and allocation concealment were infrequently reported in published trials. This limits the utility of the RCTs for policy makers and systematic reviewers. Accordingly, there must be ongoing efforts to improve the quality of reporting in published trials and to increase the proportion of journals that adopt and adhere to reporting guidelines such as CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials).14 These efforts are needed alongside initiatives to increase trial registration.

Implications for clinicians, policy makers, and future research

Our findings show that among all trials, there was little evidence of a difference in the frequency of positive study findings between registered and non-registered trials. These findings are important given the efforts of the WHO and ICMJE and the financial investment of research regulatory authorities to provide a platform for trial registration and to promote policies that support trial registration. Our findings are also important for researchers and other consumers of the scientific literature who may assume that trial registration alone increases accountability for the accurate reporting of trial results.

There may be multiple reasons for our results. Firstly, it has yet to be determined whether the information reported in trial registries is an accurate reflection of the trial protocol that was approved by the research ethics committee.15 It may be that study outcomes are not fully specified in the trial registry and, for instance, important details about the time point for analysis or the method of analysis may be missing in the registry. Discrepancies between the trial registry and study protocol reduce the accountability to conduct and report the study in accordance with what was planned.

Secondly, it may be that trials are registered but the trial registration number is omitted from the published article during submission to the journal or after peer review. In our study, 15% of trials were not reported as registered but were identified in a search of trial registries. The omission of the trial registration number in the published article also reduces the accountability that is inherent in trial registration. Finally, it may be that comparisons between the trial registry and RCTs are not routinely performed by peer reviewers or journal editors. Without these comparisons the utility of trial registration may be easily diluted by outcome switching.16 Indeed, investigators recently found discrepancies between trial registries and published articles and these differences favour statistically significant results.17

Registration of clinical trials is only the first step in improving the accountability in the reporting of research. It is necessary for journal editors, reviewers of journal articles, and researchers to report the trial registration number in the published article and to compare the results in the published article to that of the trial registry entry. These efforts ensure the benefits of trial registration are not undermined.16

Conclusion

Taken together, in a large study of published RCTs, we did not observe an association between trial registration and positive study findings. Further efforts are needed to ensure that all trials are registered and the details given in the registry are reported in the published article.

What is already known on this topic

Trial registration may be associated with positive study findings and larger treatment effects in randomised controlled trials

Existing studies were, however, small and did not account for important confounders

What this study adds

Among published randomised controlled trials, there was little evidence of a difference in positive study findings between registered and non-registered clinical trials

Subgroup analyses comparing the association between trial registration and positive study findings in non-industry funded and industry funded clinical trials were inconclusive

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary information: details of search strategy and table showing full regression models for association between trial registration and positive study findings

Contributors: CAE and AO conceived and designed the study. AO performed the study analysis. All authors acquired data, analysed and interpreted data, drafted the manuscript, and performed a critical review of the manuscript for intellectual content. AO had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. AO is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was not funded. AO, CAE, AJH and MS were supported by the Rhodes Trust. AO was additionally supported by the Clarendon Fund.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: Data and code are available from the corresponding author on request.

Transparency: The lead author (AO) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

References

- 1. De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, et al. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Lancet 2004;364:911-2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17034-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hartung DM, Zarin DA, Guise J-M, McDonagh M, Paynter R, Helfand M. Reporting discrepancies between the ClinicalTrials.gov results database and peer-reviewed publications. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:477-83. 10.7326/M13-0480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Becker JE, Krumholz HM, Ben-Josef G, Ross JS. Reporting of results in ClinicalTrials.gov and high-impact journals. JAMA 2014;311:1063-5. 10.1001/jama.2013.285634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Emdin C, Odutayo A, Hsiao A, et al. Association of Cardiovascular Trial Registration With Positive Study Findings: Epidemiological Study of Randomized Trials (ESORT). JAMA Intern Med 2014;29. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dechartres A, Ravaud P, Atal I, Riveros C, Boutron I. Association between trial registration and treatment effect estimates: a meta-epidemiological study. BMC Med 2016;14:100. 10.1186/s12916-016-0639-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Emdin CA, Odutayo A, Hsiao AJ, et al. Association between randomised trial evidence and global burden of disease: cross sectional study (Epidemiological Study of Randomized Trials--ESORT). BMJ 2015;350:h117. 10.1136/bmj.h117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Odutayo A, Altman DG, Hopewell S, Shakir M, Hsiao AJ, Emdin CA. Reporting of a Publicly Accessible Protocol and Its Association With Positive Study Findings in Cardiovascular Trials (from the Epidemiological Study of Randomized Trials [ESORT]). Am J Cardiol 2015;116:1280-3. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.07.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robinson KA, Dickersin K. Development of a highly sensitive search strategy for the retrieval of reports of controlled trials using PubMed. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:150-3. 10.1093/ije/31.1.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chan AW, Altman DG. Identifying outcome reporting bias in randomised trials on PubMed: review of publications and survey of authors. BMJ 2005;330:753. 10.1136/bmj.38356.424606.8F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Glanville JM, Duffy S, McCool R, Varley D. Searching ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform to inform systematic reviews: what are the optimal search approaches? J Med Libr Assoc 2014;102:177-83. 10.3163/1536-5050.102.3.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Savović J, Jones HE, Altman DG, et al. Influence of reported study design characteristics on intervention effect estimates from randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:429-38. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-6-201209180-00537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lundh A, Sismondo S, Lexchin J, Busuioc OA, Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:MR000033. 10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rasmussen N, Lee K, Bero L. Association of trial registration with the results and conclusions of published trials of new oncology drugs. Trials 2009;10:116. 10.1186/1745-6215-10-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869. 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zarin DA, Ide NC, Tse T, Harlan WR, West JC, Lindberg DA. Issues in the registration of clinical trials. JAMA 2007;297:2112-20. 10.1001/jama.297.19.2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goldacre B. Make journals report clinical trials properly. Nature 2016;530:7. 10.1038/530007a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mathieu S, Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Ravaud P. Comparison of registered and published primary outcomes in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2009;302:977-84. 10.1001/jama.2009.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information: details of search strategy and table showing full regression models for association between trial registration and positive study findings