Abstract.

Visceral larva migrans (VLM) is one of the clinical syndromes of human toxocariasis. We report a case of hepatic VLM presenting preprandial malaise and epigastric discomfort in a 58-year-old woman drinking raw roe deer blood. The imaging studies of the abdomen showed a 74-mm hepatic mass featuring hepatic VLM. Anti–Toxocara canis immunoglobulin G (IgG) was observed in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and western blot. Despite anthelmintic treatment, the patient complained of newly developed cough and skin rash with severe eosinophilia. Hepatic lesion increased in size. The patient underwent an open left lobectomy of the liver. After the surgery, the patient was free of symptoms such as preprandial malaise, epigastric discomfort, cough, and skin rash. Laboratory test showed a normal eosinophilic count at postoperative 1 month, 6 months, 1 year, and 4 years. The initial optical density value of 2.55 of anti–T. canis IgG in ELISA was found to be negative (0.684) at postoperative 21 months. Our case report highlights that a high degree of clinical suspicion for hepatic VLM should be considered in a patient with a history of ingestion of raw food in the past, presenting severe eosinophilia and a variety of symptoms which reflect high worm burdens. Symptom remission, eosinophilia remission, and complete radiological resolution of lesions can be complete with surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Human toxocariasis is mainly an infection with the larvae of Toxocara canis or Toxocara cati which lives in their hosts, dogs, or cats, respectively. These larvae are nonhuman host species. Human infection occurs when humans ingest food contaminated with eggs found in soil or encapsulated larvae in the raw tissues of paratenic hosts, such as cows, sheep, or chickens.1 There are three clinical syndromes associated with human toxocariasis: visceral larva migrans (VLM), ocular larva migrans (OLM), and covert toxocariasis. Visceral larva migrans is a systemic disease presenting with fever, abdominal pain, headaches, pulmonary manifestations, and hepatomegaly.2 Patients with VLM may present with marked eosinophilia in the peripheral blood and eosinophilic inflammatory lesions in the liver and/or lungs.3 Herein, we report a patient who had hepatic VLM complaining of a variety of symptoms caused by infection with T. canis after drinking raw roe deer blood. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board on Human Subjects Research and Ethics Committees of the Hanyang University Hospital (2018-07-010), and the patient provided informed consent.

CASE REPORT

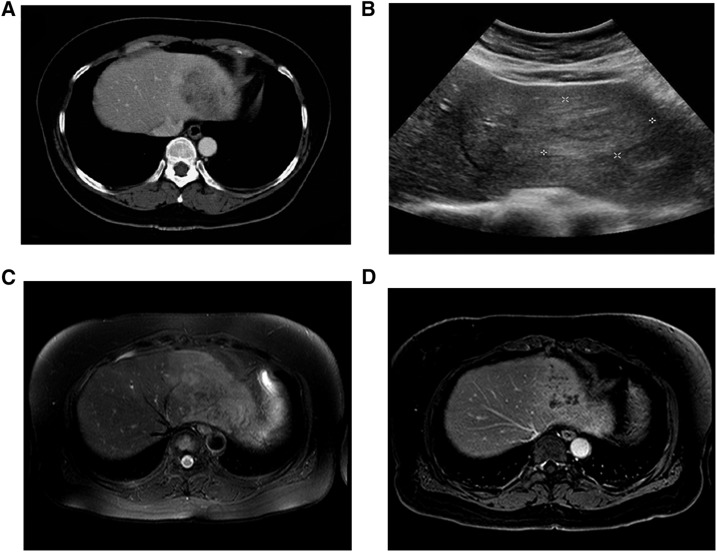

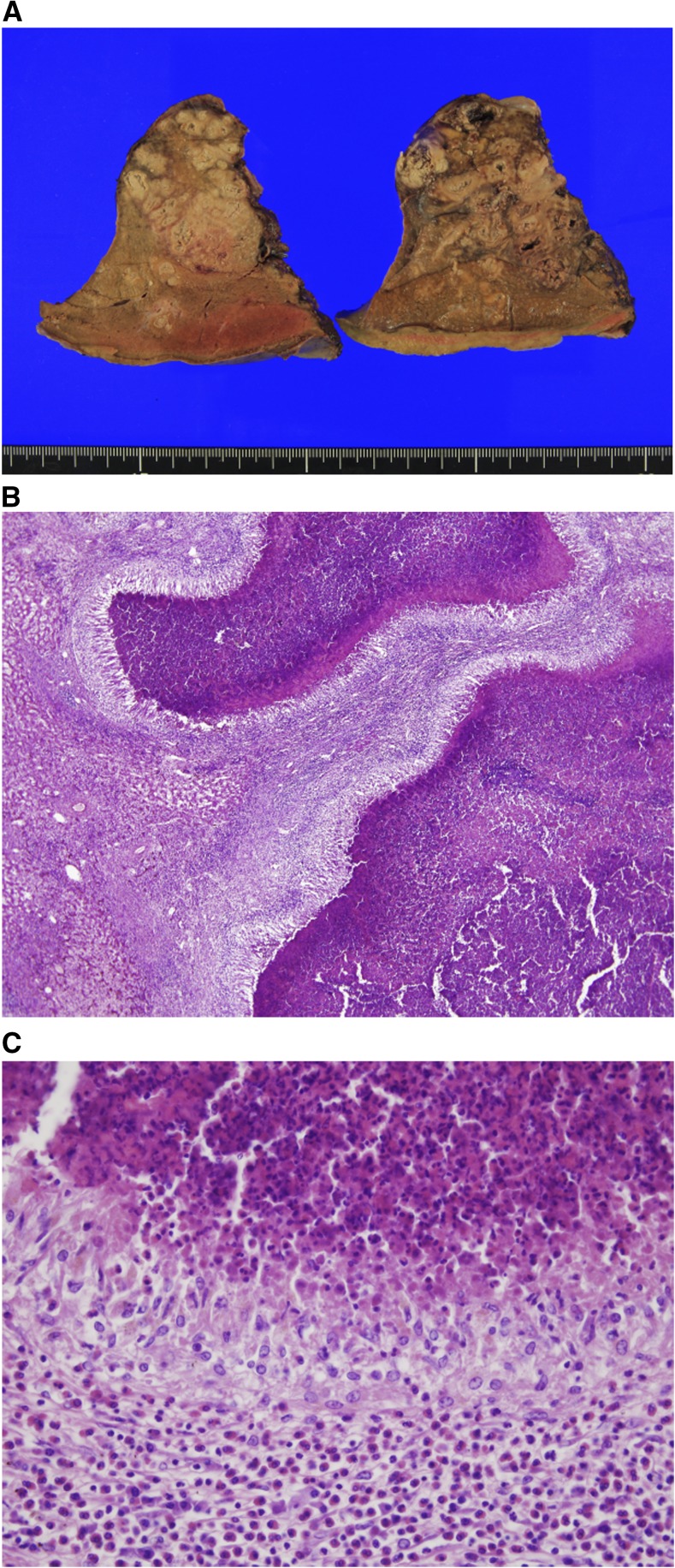

A 58-year-old woman presented to the department of family medicine in a single university hospital complaining of preprandial discomfort. The discomfort was accompanied by general weakness and trembling on hunger before meals which decreased rapidly after food ingestion. She was not taking any medications and had no relevant medical history such as diabetes. The patient lived in rural Paju of Northern Gyeonggi-do in Korea, where she worked as a farmer. On admission, her body temperature was 36.5°C and physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory evaluation disclosed a white blood cell count of 12,800 cells per mm3 with marked (28%) eosinophilia of 2,440 cells per mm3. Her C-reactive protein level was within the normal limit. Liver function tests, serum glucose, and electrolytes were normal. She did not have a similar discomfort event during hospital stay, even after 24 hours of fasting. Imaging study was performed. Abdominal computed tomography with contrast enhancement showed a 74-mm low-attenuated mass with internal hypodense conglomerations in the hepatic lateral segment mimicking cholangiocarcinoma. Abdominal ultrasound followed. It revealed an ill-defined hypoechoic mass with peripheral hyperechoic rim in the left lobe of the liver. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated an ill-defined high-signal intensity lesion on the left lobe of the liver, and this lesion showed internal hypointense conglomerations with subtle perilesional enhancement on a 10-minute delayed image using gadolinium contrast (Figure 1). She had been consuming a cup of raw roe deer blood as health food every year over the last 30 years. The last intake was 2 months ago. Under clinical suspicion of helminthic infection, ultrasound-guided liver biopsy of the lesion was conducted. Histological analysis showed an eosinophilic abscess with central fibrinoid necrosis, containing degenerating eosinophils. Tumoral process was absent. The optical density (OD) of anti–T. canis immunoglobulin G (IgG) was 2.55 (cutoff value < 1.0) on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Bordier Affinity Products, Crissier, Switzerland). The patient’s serum displayed a characteristic banding pattern of toxocariasis at 24–35 kDa in the confirmatory western blot (LDBIO, Lyon, France). Serological antibody testing for various invasive helminthic infections, such as Clonorchis sinensis, Paragonimus westermani, Cysticercus, and Sparganum, showed negative results. This resulted in the conclusive diagnosis of hepatic VLM of T. canis. She was managed with albendazole 400 mg two times a day for 2 weeks. During the follow-up period, the patient still complained of epigastric malaise on hunger along with newly developed cough and sputum. Chest X-ray showed normal findings and there was no peripheral pulmonary infiltrates in the chest computed tomography. The hepatic mass showed an increase in size in the imaging study. An increase in the blood eosinophil level of 6,610 cells per mm3 (58.8%) along with leukocytosis of 12,200 cells per mm3 was observed. She also complained of skin rashes on the central part of the face. For both confirmatory diagnosis and further treatment, she underwent an open left lobectomy of the liver and cholecystectomy. The outer surface of the liver specimen was grossly unremarkable. On serial sectioning, the cut surface showed multiple necrotic lesions, ranging from 0.5 cm to 4 cm in size. The pathologic findings of the mass were consistent with the eosinophilic abscess of the liver (Figure 2). The patient was discharged without any complications on the seventh postoperative day. The eosinophil level in the peripheral blood decreased to 181 cells per mm3 (2.2%), with no significant leukocytosis at postoperative 1 month. Serum eosinophil level and white blood cell count were found to be normal also at postoperative 6 months. She was free of symptoms such as preprandial discomfort, cough, sputum, and skin rashes. The initial OD value of 2.55 of anti–T. canis IgG in ELISA decreased to 1.811 at postoperative 1 month and 1.523 at postoperative 6 months, and appeared negative (0.684) at postoperative 21 months. She has been followed up for 2 years without peripheral eosinophilia or recurrence.

Figure 1.

(A) Abdominal computed tomography with contrast enhancement shows a 74-mm low-attenuated mass with internal hypodense conglomerations in hepatic lateral segment. (B) Abdominal ultrasound reveals an ill-defined hypoechoic mass with peripheral hyperechoic rim in the left liver. (C) T2-weighted magnetic resonance image demonstrates an ill-defined high-signal intensity lesion on the left liver. (D) This lesion showed internal hypointense conglomerations with subtle perilesional enhancement on 10-minute delayed image using gadolinium contrast.

Figure 2.

(A) The cut surface of the resected liver reveals multiple, ill-defined, irregularly shaped, grayish-white lesion with central necrosis. (B) The liver parenchyma shows multiple palisading granulomas with central necrosis, which is a typical pathologic finding of visceral larva migrans. (C) The palisading granuloma is surrounded by heavy infiltration of eosinophils and some lymphocytes. The central necrotic area consists of degenerated eosinophils and fibrinoid materials. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

DISCUSSION

Toxocara canis is the intestinal parasite of dogs in which it lives as adult within the lumen of the small intestine. Humans are the accidental host of T. canis. Human infection occurs by ingestion of embryonated eggs found in the soil, by eating encapsulated larvae in raw animal tissue, or via contaminated hands.1 Human infection is aberrant and usually asymptomatic, defined as covert toxocariasis. However, severe clinical manifestations, that is, VLM or OLM syndromes, are observed.2 The severity of clinical manifestation occasionally depends on the direct invasion of specific target organs, such as the liver, lungs, and eyes.4 The full-blown VLM can present with malaise, fever, pruritus, pulmonary symptoms, hepatomegaly, abdominal discomfort, and extreme eosinophilia (greater than 50% of white cells in the peripheral blood).4,5

Although toxocariasis is one of the most common zoonotic infections worldwide, seroprevalence of Toxocara infection is randomly distributed demographically.5–7 In Korea, seropositivity to T. canis antigen was reported to be as high as 5% in apparently healthy residents in Gangwon-do.8 The main risk factor for toxocariasis in adults is the ingestion of raw food. In persons with a history of ingestion of raw food, the prevalence of toxocariasis was 7.8 times higher than that in those with no history of ingestion of raw food.9 In our case, the patient had a history of ingestion of raw roe deer blood. In Korea, there is a report of cerebral infarction caused by toxocariasis in an adult with a history of ingestion of raw liver of deer.10 Similarly, in Japan, there is a report of fulminant eosinophilic myocarditis caused by VLM after eating raw deer meat.11

Definitive diagnosis of human toxocariasis is a histological examination of infected tissues. However, obtaining the suitable biopsy material is an invasive procedure and it is often difficult to identify the parasitic structure in the tissue. Presently, an ELISA test using excretory–secretory antigens of T. canis L3 is used for the diagnosis of human toxocariasis. In conjunction with a relevant clinical history of ingestion of raw food, clinical manifestations, and peripheral eosinophilia, serological diagnosis by enzyme immunoassay is regarded as a useful tool for diagnosis.12 In this case, we made the diagnosis of human toxocariasis with reference to the clinical history of raw food ingestion, marked peripheral eosinophilia, and positive result in the ELISA and western blot tests.

Albendazole is known as the treatment of choice for toxocariasis. A dose of 400 mg of albendazole twice a day for 5 days is the current recommended therapy.13 However, there is no agreement about the optimal duration of albendazole therapy.14 One study has reported that liver abscess caused by toxocariasis was usually accompanied by mild to moderate eosinophilia and the size of the lesion decreased in 3 months after 5 days of albendazole therapy.15 Interestingly, a recent report has on the usefulness of albendazole noted that only 6 (32%) of 19 patients were cured after a 5-day albendazole therapy.16 In this case, the patient showed an increase in eosinophil count despite antihelmintic treatment and developed new symptoms such as cough, sputum, and skin rash over more than 3 months. A series of symptoms may be related to the space-occupying lesion in the liver.17 Also, it may reflect the effects of the larvae on various organs in the body. There are some reports that hepatic VLM was surgically cured when medical treatment failed or when eosinophilic infiltration possibly caused damage to multiple organs.18–21 In our case, definitive diagnosis and complete remission of eosinophilia were established in the patient after surgery and histopathological studies.

In conclusion, the present case report demonstrates clinical manifestations of hepatic VLM in the patient who had been consuming raw roe deer blood for a long time. Given that Asians, including Koreans, have the habit of consuming raw liver, muscle, and blood of herbivores as health food, diagnostic management of Toxocara infection can be established without delay when physicians are aware of the high seroprevalence of VLM. Various clinical symptoms with severe eosinophilia can be present. Also, clinicians should consider the possibility of VLM with hepatic infiltration in patients who used to ingest raw food in the past. Surgery is often considered for patients with severe toxocariasis, although they are usually treated with systemic anthelmintics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rubinsky-Elefant G, Hirata CE, Yamamoto JH, Ferreira MU, 2010. Human toxocariasis: diagnosis, worldwide seroprevalences and clinical expression of the systemic and ocular forms. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 104: 3–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor MH, O’connor P, Keane C, Mulvihill E, Holland C, 1988. The expanded spectrum of toxocaral disease. Lancet 1: 692–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim JH, 2012. Foodborne eosinophilia due to visceral larva migrans: a disease abandoned. J Korean Med Sci 27: 1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pawlowski Z, 2001. Toxocariasis in humans: clinical expression and treatment dilemma. J Helminthol 75: 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith H, Holland C, Taylor M, Magnaval JF, Schantz P, Maizels R, 2009. How common is human toxocariasis? Towards standardizing our knowledge. Trends Parasitol 25: 182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akao N, Ohta N, 2007. Toxocariasis in Japan. Parasitol Int 56: 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodhall DM, Eberhard ML, Parise ME, 2014. Neglected parasitic infections in the United States: toxocariasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 90: 810–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park HY, Lee SU, Huh S, Kong Y, Magnaval JF, 2002. A seroepidemiological survey for toxocariasis in apparently healthy residents in Gangwon-do, Korea. Korean J Parasitol 40: 113–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon NH, Oh MJ, Lee SP, Lee BJ, Choi DC, 2006. The prevalence and diagnostic value of toxocariasis in unknown eosinophilia. Ann Hematol 85: 233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YB, Ko YC, Jeon SH, Park HM, Shin WC, Lee YB, Ha KS, Shin DJ, Lim YH, Ryu JS, 2003. Toxocariasis: an unusual cause of cerebral infarction. J Korean Neurol Assoc 21: 651–654. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enko K, et al. 2009. Fulminant eosinophilic myocarditis associated with visceral larva migrans caused by Toxocara canis infection. Circ J 73: 1344–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Savigny DH, Voller A, Woodruff AW, 1979. Toxocariasis: serological diagnosis by enzyme immunoassay. J Clin Pathol 32: 284–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kappagoda S, Singh U, Blackburn BG, 2011. Antiparasitic therapy. Mayo Clin Proc 86: 561–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshikawa M, 2009. Duration of treatment with albendazole for hepatic toxocariasis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 6: E1–E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ha KH, Song JE, Kim BS, Lee CH, 2016. Clinical characteristics and progression of liver abscess caused by toxocara. World J Hepatol 8: 757–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sturchler D, Schubarth P, Gualzata M, Gottstein B, Oettli A, 1989. Thiabendazole vs. albendazole in treatment of toxocariasis: a clinical trial. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 83: 473–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philips CA, Sharma CB, Pande A, Khan J, 2016. Space occupying lesion of the liver: the feline connection. Sch Acad J Biosci 4: 425–428 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laroia ST, Rastogi A, Bihari C, Bhadoria AS, Sarin SK, 2016. Hepatic visceral larva migrans, a resilient entity on imaging: experience from a tertiary liver center. Trop Parasitol 6: 56–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee KE, Suh KS, Lee NJ, Chang SH, Choi S, Kim SH, Lee KU, 2003. Laparoscopy-assisted hepatic resection in a patient with eosinophilic liver abscess by toxocaris cani involving liver. J Korean Surg Soc 64: 261–265. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukund A, Arora A, Patidar Y, Mangla V, Bihari C, Rastogi A, Sarin SK, 2013. Eosinophilic abscesses: a new facet of hepatic visceral larva migrans. Abdom Imaging 38: 774–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Treska V, Sutnar A, Mukensnabl P, Manakova T, Sedlacek D, Mirka H, Ferda J, 2011. Liver abscess in human toxocariasis. Bratisl Lek Listy 112: 644–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]