Abstract

Maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) is essential for the formation of a new individual, but is still poorly understood despite recent progress in analysis of gene expression and DNA methylation in early embryogenesis1–9. Dynamic histone modifications may have important roles in MZT10–13, but direct measurements of chromatin states have been hindered by technical difficulties in profiling histone modifications from small quantities of cells. Recent improvements allow for 500 cell-equivalents of chromatin per reaction, but require 10,000 cells for initial steps14 or require a highly specialized microfluidics device that is not readily available15. We developed a micro-scale chromatin immunoprecipitation and sequencing (μChlP-seq) method, which we used to profile genome-wide histone H3 lysine methylation (H3K4me3) and acetylation (H3K27ac) in mouse immature and metaphase II oocytes and in 2-cell and 8-cell embryos. Notably, we show that ~22% of the oocyte genome is associated with broad H3K4me3 domains that are anti-correlated with DNA methylation. The H3K4me3 signal becomes confined to transcriptional-start-site regions in 2-cell embryos, concomitant with the onset of major zygotic genome activation. Active removal of broad H3K4me3 domains by the lysine demethylases KDM5A and KDM5B is required for normal zygotic genome activation and is essential for early embryo development. Our results provide insight into the onset of the developmental program in mouse embryos and demonstrate a role for broad H3K4me3 domains in MZT.

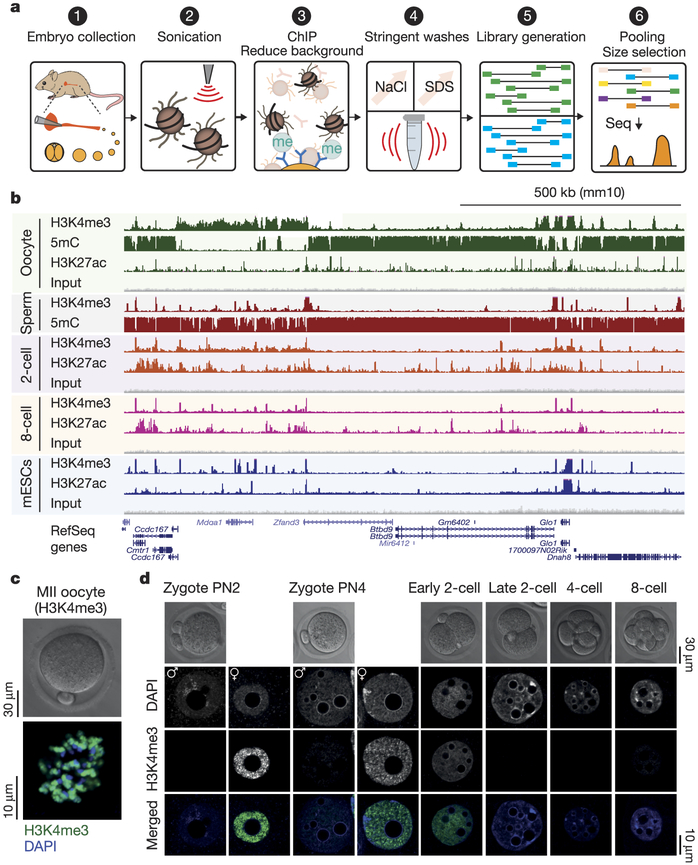

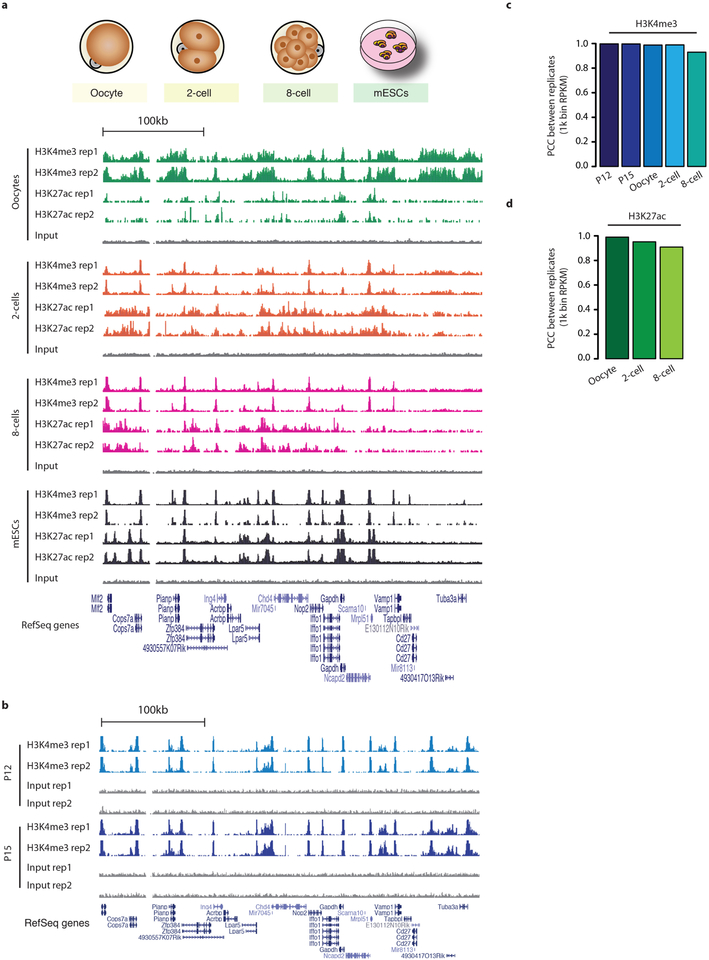

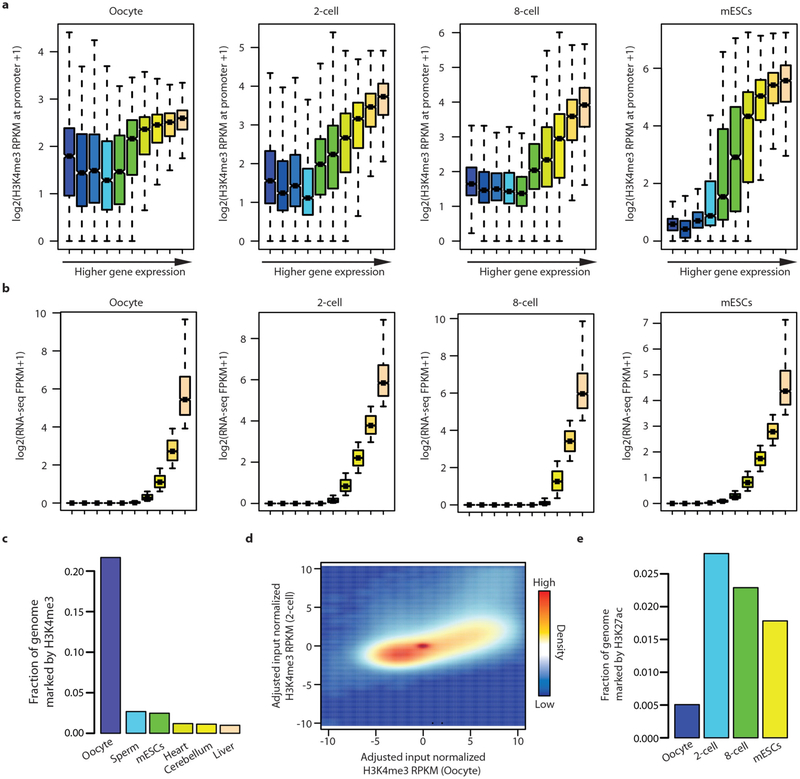

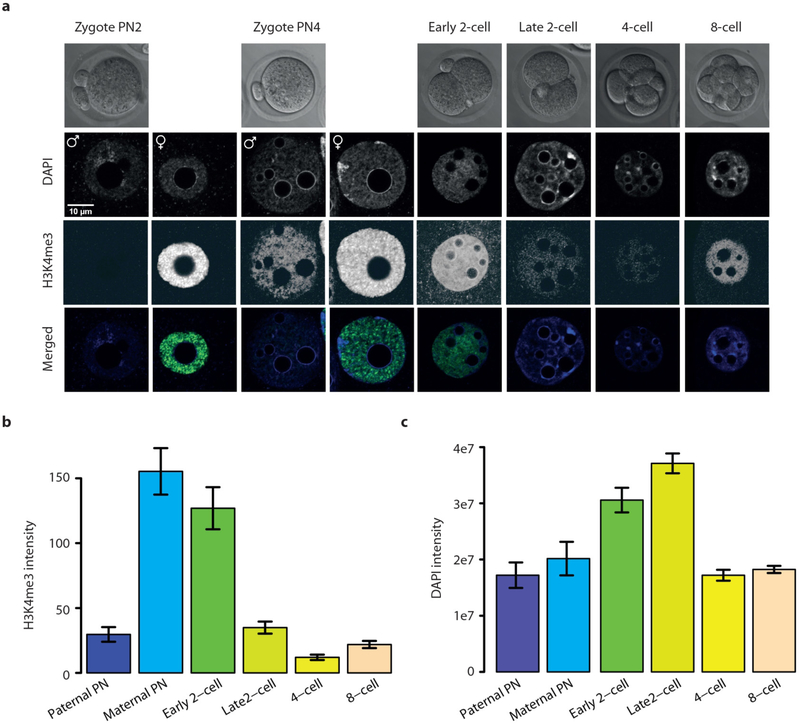

We developed a highly sensitive micro-scale μChlP-seq method (Fig. 1a, see Methods), and validated μChIP-seq for H3K4me3 and H3K27ac (Extended Data Fig. 1a–g). Notably, we can reliably detect 85% of ENCODE (ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements) H3K4me3 peaks from as few as 500 cells (Extended Data Fig. 1d). There was no GC bias between undetected and detected ENCODE H3K4me3 peaks (Extended Data Fig. 1h); rather, the undetected peaks were weak ENCODE peaks (Extended Data Fig. 1i). We used μChIP-seq to generate genome-wide H3K4me3 and H3K27ac histone-modification maps from mouse oocytes, 2-cell- and 8-cell-stage embryos (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Table 1), with high reproducibility between biological replicates (Extended Data Fig. 2a–d). Because in vitro culture is known to affect the transcriptome as well as the morphological and biochemical characteristics of mammalian embryos16, we used in vivo developed embryos. We noted a distinct architecture of H3K4me3 in oocytes when compared to other cell types (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 3a, b), with H3K4me3 covering very broad regions that make up ~22% of the genome (Extended Data Fig. 3c). Genomic coverage by strong H3K4me3 levels is rapidly reduced in 2-cell-stage embryos (Extended Data Fig. 3d). In line with μChIP-seq results, immunofluorescence staining of H3K4me3 shows high levels of H3K4me3 in the oocyte and that the H3K4me3 signals are rapidly lost from the early to the late 2-cell-stage embryo (Fig. 1c, d, Extended Data Fig. 4a–c, Supplementary Video 1), correlating with the time of major zygotic genome activation (ZGA). In contrast to H3K4me3, genomic coverage by H3K27ac increases markedly from oocytes to 2-cell-stage embryos (Extended Data Fig. 3e).

Figure 1 |. Development of μChIP-seq to investigate epigenomic landscapes of oocytes and embryos.

a, Schematic of μChIP-seq. Step 3 describes addition of histone octameres and IgG to outcompete unspecific binding. b, A UCSC genome browser snapshot of H3K4me3 and H3K27ac μChIP-seq, input and WGBS DNA methylation as indicated for MII oocytes, sperm, 2- and 8-cell embryos and mouse ES cells (mESCs). Sperm data are from ref. 23. c, d, Confocal laser scanning micrographs showing H3K4me3 levels in MII oocytes (c) and pronuclear (PN) stage PN2 and PN4 zygotes, 2-cell-, 4-cell- and 8-cell-stage embryos (d). Representative single plane micrographs are shown of H3K4me3 (green) and DNA (DAPI, blue).

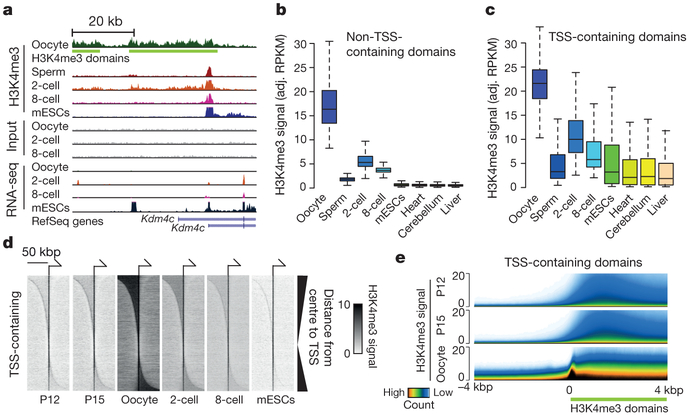

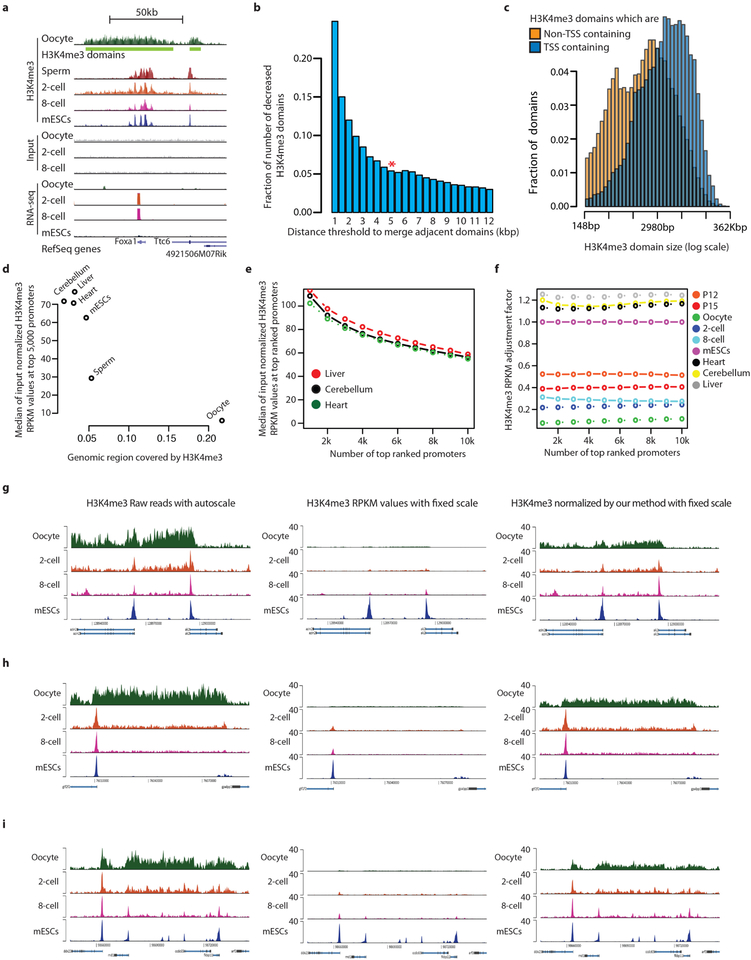

Chromatin from all cell types of the eukaryotic species investigated to date typically displays a relatively narrow and promoter-specific localization of H3K4me3, primarily at promoters of active genes17,18. Notably, we found highly prevalent, broad H3K4me3 domains that span more than 10 kb DNA in mouse metaphase II (MII) oocytes (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 5a). Systematically, we identified a total of 63,542 broad H3K4me3 domains in oocytes and classified them into transcription start site (TSS)-containing and non-TSS-containing domains (Extended Data Fig. 5b–i, Supplementary Table 2, see Methods). In contrast to somatic cells, the H3K4me3 signals in oocytes are generally (~75%) away from TSSs and these signals are rapidly lost in 2-cell and 8-cell embryos (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 6a). However, some of the H3K4me3 signal at TSS-containing domains is specifically maintained in the 2-cell and 8-cell embryo (Fig. 2c, Extended Data Fig. 6b, see Methods). Further investigation of TSS-containing domains revealed that a TSS is often present near only one end (41%) or both ends (39%) of TSS-containing broad H3K4me3 domains (oocyte panel in Fig. 2d, see Methods). In the early embryo, H3K4me3 signals are strongly maintained at TSSs compared to regions distal to TSSs (2-cell, 8-cell, and mouse embryonic stem cell (ES cell) panels in Fig. 2d). To assess the establishment of broad H3K4me3 domains, we performed H3K4me3 μChIP-seq on growing oocytes from 12-day-old (P12) and 15-day-old (P15) mice (Extended Data Fig. 2b, c and 6c). The relatively low levels of broad-domain-spanning H3K4me3 signals gradually increase from P12 oocytes onwards within both non-TSS- and TSS-containing domains and, generally, TSS-containing domains have earlier establishment of H3K4me3 when compared to non-TSS-containing domains (Fig. 2e, Extended Data Fig. 6d). In support of this, 91% and 94% of TSS-containing broad domains and 23% and 33% of non-TSS-containing broad domains have an overlapping H3K4me3 peak in P12 and P15 oocytes, respectively.

Figure 2 |. Characterization of broad H3K4me3 domains.

a, Genome browser snapshot of H3K4me3 μChIP-seq and RNA-seq signals at the Kdm4c locus (ZGA gene). Green bars indicate broad H3K4me3 domain call. b, c, Box plots of adjusted (adj.) input normalized H3K4me3 reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) values at non-TSS (n = 47,934) (b) and TSS-containing domains (n = 15,608) (c). Whiskers correspond to the highest and lowest points within the 1.5 × interquartile range. d, Heat maps of H3K4me3 signal for TSS-containing domains. Horizontal positions reflect spatial distribution relative to TSS. Vertical order reflects distance from centre of domain to TSS. e, Superimposed tracks of H3K4me3 signal at the boundaries of TSS-containing domains. Colouring reflects total count of domains with a given signal intensity (n = 15,608).

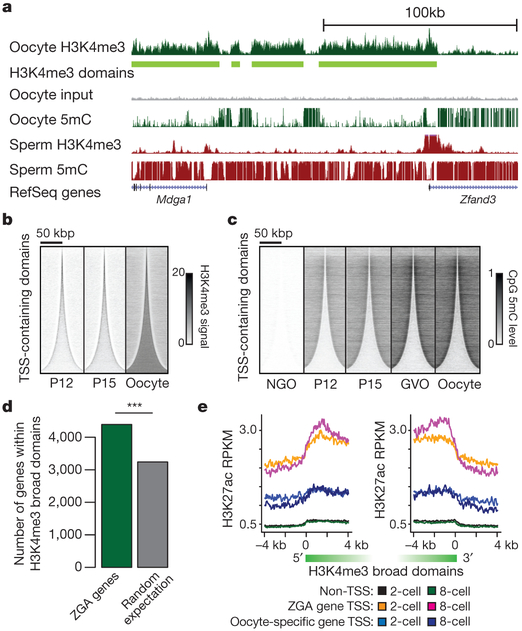

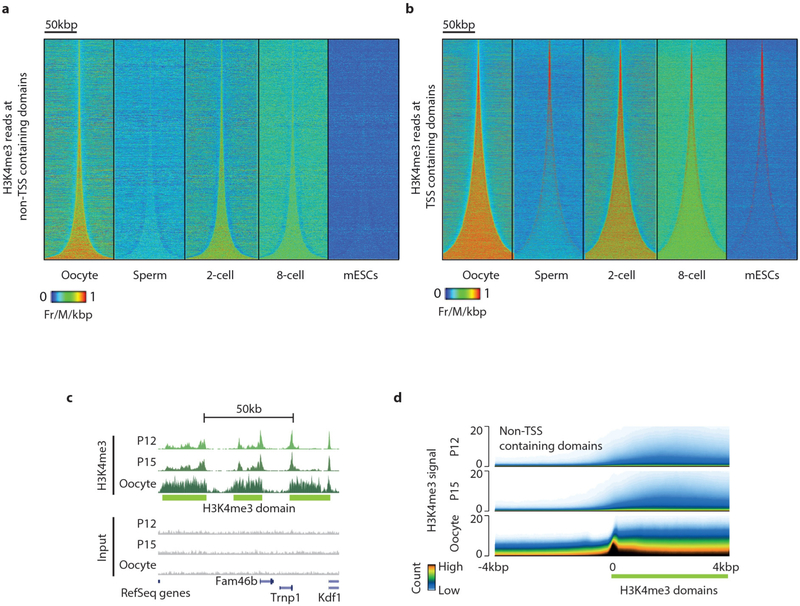

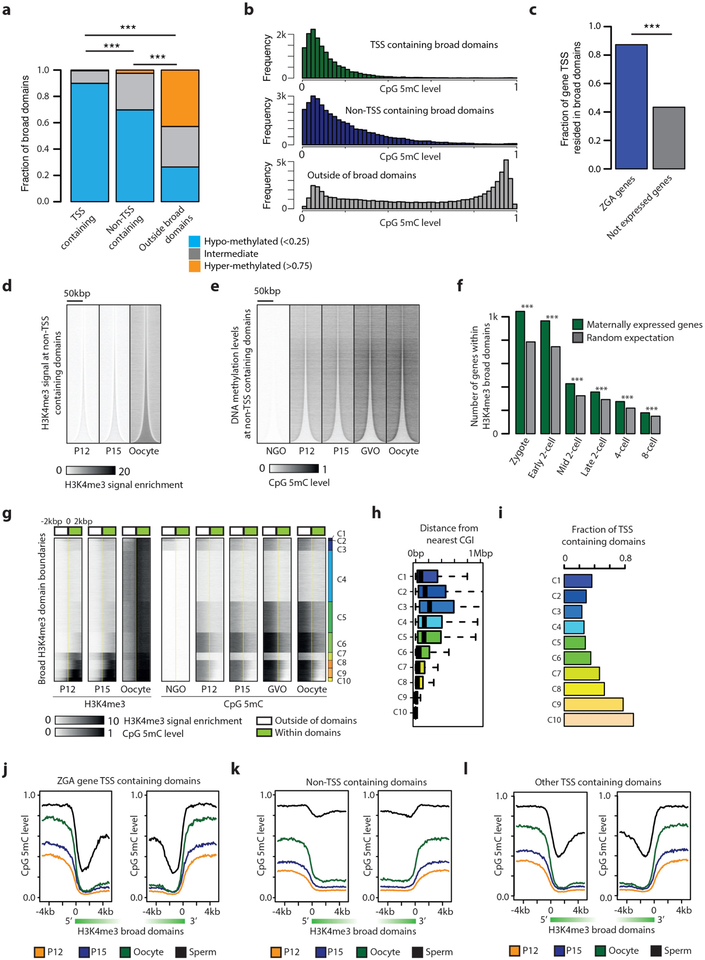

We hypothesized that the formation of broad H3K4me3 domains could interfere with the deposition of DNA methylation in the oocyte genome. To investigate this possibility, we examined recently published whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) data from mouse oocytes19. As expected, DNA methylation is anti-correlated with H3K4me3 in the oocyte (Fig. 1b, 3a, Extended Data Fig. 7a, b), evident as hypomethylation (average 18% CpG methylation) within broad H3K4me3 domains, compard with markedly higher DNA methylation levels (average 57% CpG methylation) in genomic regions lacking H3K4me3. These observations are in agreement with the reported role of H3K4me3 in blocking DNMT3L and de novo DNA methylation20,21. Furthermore, de novo methylation in the oocyte is largely dependent on DNMT3L22. Therefore it is plausible that H3K4me3 may have the ability to block DNMT3L-dependent de novo methylation in oocytes.

To investigate further the temporal relationship between H3K4me3 and DNA methylation in growing oocytes, we carried out WGBS of P12 and P15 oocytes and incorporated recently published WGBS data from non-growing oocytes (NGO) and germinal vesicle stage oocytes (GVO)22 (Supplementary Table 3, see Methods). We revealed a gradual genome-wide increase in both DNA methylation and H3K4me3, with H3K4me3 gradually increasing within broad domains and DNA methylation gradually increasing outside for both TSS- and non-TSS-containing domains (Fig. 3b, c, Extended Data Fig. 7d, e). k-means clustering for the combined DNA methylation and H3K4me3 patterns at broad domain boundaries identified 10 different clusters (Extended Data Fig. 7g). About 55% of the broad H3K4me3 domain boundaries (C4, C7, C8, C9, and C10) show establishment of high levels of H3K4me3 before establishment of high levels (C8, C9, C10), a less pronounced increase (C7) or hardly any increase (C4) in DNA methylation. The remaining 45% of the broad domain boundaries display a more pronounced early establishment of DNA methylation as compared to H3K4me3 (C1, C2, C3, C5 and C6). Domain boundaries that gain high levels of H3K4me3 inside the broad domain early on (C7, C8, C9, C10) have low levels of DNA methylation within the broad domain throughout oogenesis, although sequences adjacent to the broad domain gain high levels of DNA methylation. It is possible that early establishment of H3K4me3 can protect against DNA methylation, whereas the observed levels of DNA methylation within broad domains do not prevent later establishment of H3K4me3 (C1, C2, C3, C5, C6). It remains a possibility that higher levels of DNA methylation outside of these broad domains have a role in defining domain boundaries. For the majority of broad H3K4me3 domains, the full establishment takes place after P15 (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 7d). Broad domain boundaries with early establishment of H3K4me3 are associated with proximal CpG islands and TSS-containing domains (Extended Data Fig. 7h, i).

Figure 3 |. Relationships between broad H3K4me3 domains, DNA methylation and ZGA.

a, Genome browser snapshot of H3K4me3 signal and DNA methylation levels for oocyte and sperm19,23. b, c, Heat maps of H3K4me3 and DNA methylation for indicated oocyte stages at TSS-containing domains ordered according to increasing sizes (n = 15,608). Horizontal positions, spatial distribution relative to domain centre; Densities, H3K4me3 signal (b) or CpG methylation level (c). d, Bar plot showing number of ZGA genes embedded within broad H3K4me3 domains and the number expected by chance (***P < 10−3, Fisher’s exact test). e, Average H3K27ac RPKM values of 5’ and 3’ sides and flanking regions of broad H3K4me3 domains in 2- and 8-cell-stage embryos for ZGA gene TSS-containing domains (n = 2,104), oocyte-specific gene TSS-containing domains (n = 1,117) and non-TSS-containing domains (n = 12,691) broader than 10 kb. Domains containing both ZGA and oocyte-specific gene TSSs were excluded.

We next investigated whether oocyte-specific broad H3K4me3 domains have a role in zygotic genome activation. First, a majority of previously reported ZGA genes5 significantly overlaps with broad H3K4me3 domains (86%, Fig. 3d, Extended Data Fig. 7c), and a stringent assessment of genes expressed from the maternal allele in the early embryo but not in oocytes confirmed that ZGA genes are enriched within broad domains (Extended Data Fig. 7f). Furthermore, ZGA gene TSS-containing broad domains showed markedly reduced DNA methylation in sperm compared to other TSS- or non-TSS-containing broad domains (Extended Data Fig. 7j–l). Notably, non-TSS-containing broad domains presented the most differentially methylated regions between oocyte and sperm (Extended Data Fig. 7k). In accordance with observed DNA hypomethylation of ZGA gene promoters in both oocyte and sperm, we found that 79.4% of ZGA genes5 are pre-marked by H3K4me3 in both oocyte and sperm23 and specifically maintain H3K4me3 at their promoters during ZGA. In addition, ZGA gene TSS-containing domains gained activating H3K27ac in 2- and 8-cell stage embryos (Fig. 3e), supporting the relationship between H3K4me3 domains and specification of genome activation during MZT. Oocyte-specific gene TSSs embedded within broad H3K4me3 domains do not gain high levels of H3K27ac (Fig. 3e).

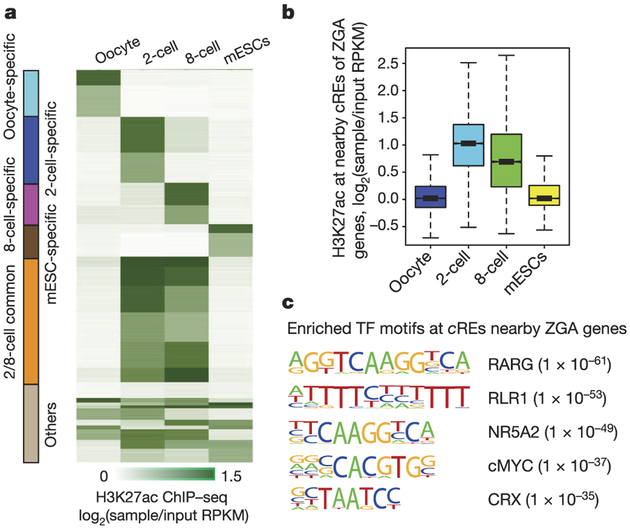

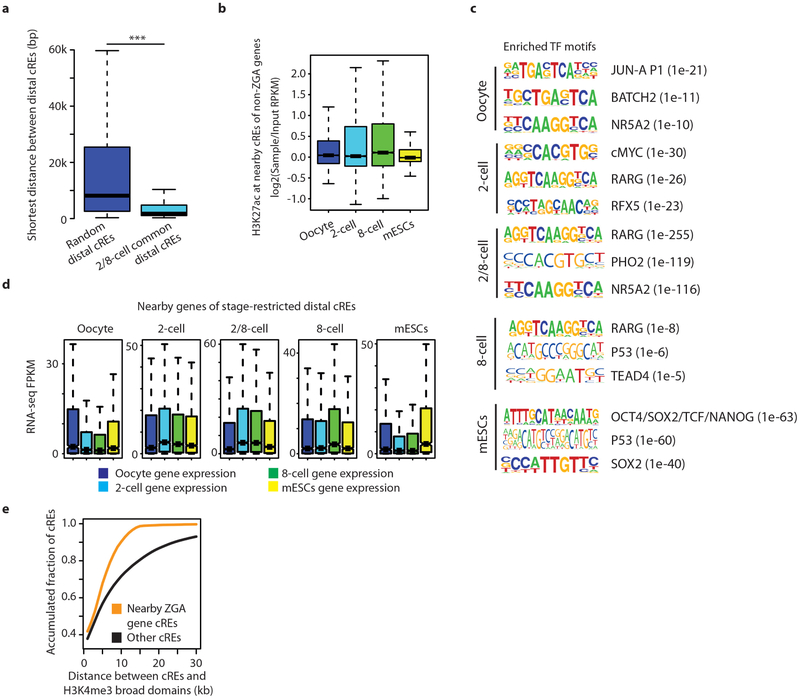

As H3K27ac is a mark of active ds-regulatory elements (cREs)24,25 reported to be highly cell- and tissue-specific26,27, we further investigated cREs that are probably involved in ZGA and establishment of totipotency in 2-cell and 8-cell embryos. To this end, we first predicted 105,100 candidate distal cREs that are marked by H3K27ac in oocytes, 2-cell embryos, 8-cell embryos or ES cells (see Methods). k-means clustering of these elements revealed several classes of stage-restricted distal cREs (Fig. 4a). We found that cREs common between 2-cell and 8-cell stages tend to cluster together (Extended Data Fig. 8a), and reside near ZGA genes (Fig. 4b, Extended Data Fig. 8b). Each class of stage-restricted cREs, and also nearby cREs of ZGA gene TSSs, are enriched for specific transcription-factor-binding motifs (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 8c, Supplementary Table 4), and are well-correlated with stage-specific gene expression levels (Extended Data Fig. 8d). GREAT (Genomic Regions Enrichment of Annotations Tool) analysis of each class of stage-restricted cREs and gene-set-enrichment analysis of genes with a certain transcription factor in nearby cREs revealed enrichment for multiple biological processes and phenotypic changes that are strongly associated with the corresponding stage (Supplementary Tables 5–7, see Methods). Moreover, cREs in the vicinity of a ZGA gene TSS are located within or close to broad H3K4me3 domains (Extended Data Fig. 8e). Our results are consistent with a model that activation of ZGA genes can be driven by cREs that are predominantly located within the oocyte-specific broad H3K4me3 domains.

Figure 4 |. Characterization of putative distal cREs.

a, k-means clustered heat map of input-normalized H3K27ac signals at putative promoter-distal cREs for oocyte, 2- and 8-cell embryos and mouse ES cells (n = 105,094). Each row indicates an individual distal cRE. b, Box plots for H3K27ac ChIP-seq RPKM values of putative cREs (n = 15,747) in the vicinity of ZGA genes5 present strong H3K27ac signals in 2- and 8-cell stage embryos compared to oocytes or mouse ES cells (P < 2.2−16, Kolmogorov-Smirnoff test). Whiskers correspond to the highest and lowest points within the 1.5 × interquartile range. c, Top 5 enriched transcription factor binding motifs found within putative cREs (n = 15,747) in the vicinity of ZGA genes. Rlrl is also known as Ddx58.

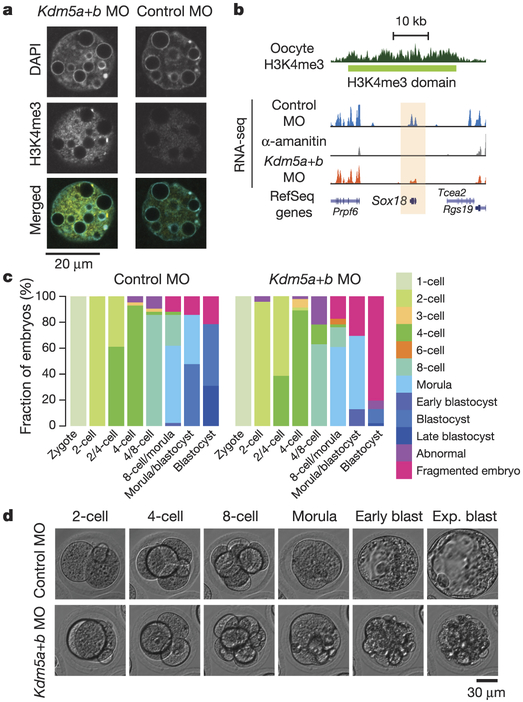

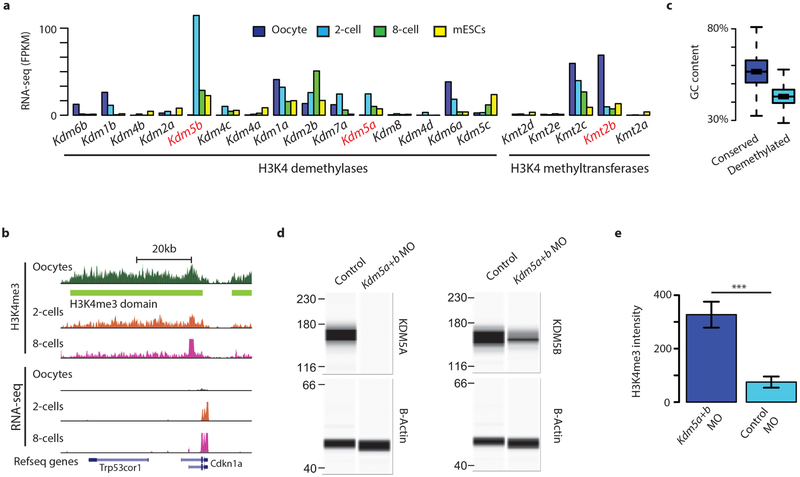

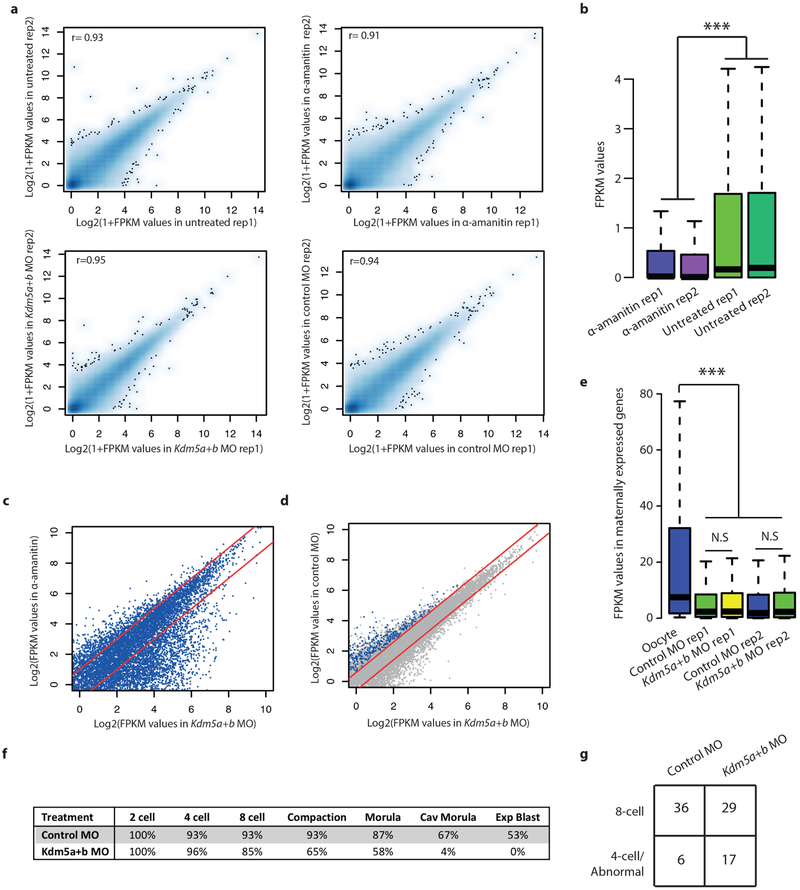

To further establish the regulatory mechanism of broad H3K4me3 domain dynamics in MZT, we assessed the expression patterns of candidate histone lysine methyltransferases and demethylases (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Previous work has shown that KMT2B (also known as MLL2) is responsible for establishing the majority of H3K4me3 in oocytes28. Taken together with our findings, we can directly infer that KMT2B is the major methyltransferase for broad H3K4me3 domains. Furthermore, KMT2B is required for normal ZGA28. Consistent with this, we found that all of the eight previously defined KMT2B-dependent genes28 are located within broad H3K4me3 domains and are upregulated in 2-cell and 8-cell embryos when broad H3K4me3 domains are lost (one example is shown in Extended Data Fig. 9b). The Kdm5b (also known as Jaridlb and Plu-1) and Kdm5a (also known as Jaridla and Rbp2) H3K4 demethylases show peak expression in 2-cell embryos (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Both demethylases contain an AT-rich interactive domain and, consistent with this, sequences specifically targeted for removal of H3K4me3 have low GC and high AT content (Extended Data Fig. 9c), suggesting a potential DNA-sequence-dependent mechanism involved in the precise removal and maintenance of H3K4me3 during ZGA. Embryos depleted for both demethylases retain high levels of H3K4me3 at the late 2-cell stage, demonstrating that KDM5A and KDM5B are responsible for actively removing broad H3K4me3 domains (Fig. 5a, Extended Data Fig. 9d, e, see Methods). We next investigated transcriptional changes induced by depletion of KDM5A and KDM5B (Extended Data Fig. 10a–c, Supplementary Table 8). We observed a significant number (1,303) of downregulated ZGA genes (5.5 odds ratio compared to other genes, P < 2.2−16, Fisher’s Exact test) in KDM5A- and KDM5B-depleted 2-cell embryos (Fig. 5b, Extended Data Fig. 10d), suggesting an effect of active H3K4me3 removal on the activation of these ZGA genes. The downregulated genes are enriched for ZGA-gene-related5 biological processes (Supplementary Table 9). Maternally expressed genes were not affected overall (Extended Data Fig. 10e). Notably, we observed that most (87%) (Fig. 5c, d) or all (Extended Data Fig. 10f) of the KDM5A- and KDM5B-depleted embryos fail to develop to the blastocyst stage. Developmental delay can already be observed at the 4-cell to 8-cell transition (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 10g). Severe phenotypes are also observed for Kmt2b deficiency, with conditional depletion during all follicular stages in oocytes resulting in sterility, and later induced (primary follicular stage) conditional depletion results in low ovulation rate and embryonic arrest at the 1-cell to 4-cell stage28. Therefore, both the establishment of broad H3K4me3 domains in the oocyte and the timely removal of H3K4me3 at the 2-cell stage are critical for embryo development.

Figure 5 |. KDM5A and KDM5B remove broad H3K4me3 domains.

a, Confocal laser scanning micrographs showing H3K4me3 levels in late 2-cell stage embryos after injection with morpholinos targeting Kdm5a and Kdm5b (Kdm5a+b MO), or 5-base mismatch control morpholinos (control MO). H3K4me3 (yellow) and DNA (DAPI, cyan). b, Genome browser snapshot is shown for Sox18 gene expression levels for Kdm5a+b MO, control morpholinos, and α-amanitin treated embryos. c, Stacked bar plots show fraction of embryos at different developmental stages after injection with morpholinos targeting Kdm5a and Kdm5b (right side, n = 46), or control morpholinos (left side, n = 42). d, Representative images of abnormal development in Kdm5a+b MO injected embryos, compared with normal development in control morpholino embryos. Blast, blastocyst; exp. blast, expanded blastocyst.

The broad nature of a large number of H3K4me3 domains in the oocyte and the widespread presence of H3K4me3 at genomic regions away from TSSs make the oocyte epigenome clearly distinctive from that of any other eukaryotic cell type assessed to date29,30. It also contrasts with the established model that H3K4me3 is localized to promoter regions, preferably of transcribed genes. Establishment, transgenerational inheritance and timely removal of this unique broad H3K4me3 domain structure are essential to the continuum of the haploid-diploid life cycle in mice.

METHODS

Data reporting.

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Mouse housing and handling.

All mouse experiments were approved by the Animal Research Committee, the Norwegian Food Safety Authority (NFDA), and conducted in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations (FELASA). C57BL6/CBA mice were housed in IVC SealSafe Plus Greenline cages in an Aero IVC Greenline system at SPF status. They were maintained on a 12 h light, 12 h dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water.

Collection of oocytes and preimplantation embryos.

Four- to eight-week-old donors were injected with 5 units of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (for oocytes and 2-cells at 14:00; for 8-cells at 15:00, 100 μl of 50 I.U. (international units) ml−1 solution) followed by 5 units of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (for oocytes and 2-cells at 11:00; for 8-cells, 15:00, 100 μl of 50 I.U. ml−1 solution) 45 h (for oocytes and 2-cells) or 48 h (for 8-cells) after injection of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin. For 2-cells and 8-cells collection, females were transferred to cages with males for breeding immediately after hCG injections.

Oocyte collection.

Donor mice were killed by cervical dislocation 18 h after hCG injection (no mating). Oviducts were transferred to a clean dish with M2 (Sigma) medium. The ampulla was identified under a stereomicroscope, and the oocytes released followed by removal of cumulus mass by room temperature incubation in M2 containing 0.3 mg ml−1 hyaluronidase. The oocytes were further washed in M2.

2-cell collection.

Donor mice were killed by cervical dislocation 45 h after hCG injection. Oviducts were transferred to a clean dish with M2 medium. Infundibulum was identified and the 2-cells were released by placing a syringe containing M2 inside the infundibulum opening, followed by flushing the M2 through the whole oviduct. The 2-cells were further washed in M2 medium.

8-cell collection.

Donor mice were killed by cervical dislocation 68 h after hCG injection/mating. Oviducts were transferred to a clean dish with M2 medium. Infundibulum was identified and the 8-cells were released by placing a syringe containing M2 inside the infundibulum opening, followed flushing the M2 through the whole oviduct. The 8-cells were further washed in M2 medium.

Zona removal.

The oocytes, 2-cells and 8-cells were transferred to a 150 μl drop of Acidic Tyrode’s solution (Sigma), and further transferred to a drop of M2 immediately after the zona had been removed. 5 steps of washing in M2 were carried out, and the oocytes, 2-cells and 8-cells were ready for fixation.

Collection of immature oocytes from prepubertal mice.

Immature oocytes were isolated from 12-day-old and 15-day-old prepubertal CD-1 mice (RjOrl:SWISS) as follows. Ovaries were removed with fine scissors and carefully freed from surrounding tissues with a 25G needle. Batches of five ovaries were placed in 800 μl DPBS in a 60 mm culture dish, 400 μl of Trypsin-EDTA (0.05%) (Gibco) was added immediately before fine mincing of the ovaries with a scalpel. After mincing, 5 μl of DNase I (10 U μl−1) (Sigma, 04716728001) was added and the minced ovaries were incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. Next, 20 μl of Collagenase Type II (100 mg ml−1) (Sigma, C9407), 800 μl of DBPS and 400 μl of Trypsin-EDTA (0.05%) was added and the dish was incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. Mechanical dissociation with a pipette then resulted in denuded oocytes. To remove any possible traces of somatic contaminants, and to remove the zona, oocytes were washed four times in M2 medium, incubated in two consecutive drops of M2 containing 0.3 mg ml−1 hyaluronidase, washed two times in M2 medium, then in two drops of Acidic Thyrode’s solution (Sigma) and again washed four times in M2 medium. Batches of oocytes to be analysed for DNA methylation were washed once in WGBS lysis solution (20 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA), transferred in a volume of maximum 5 μl to a 1.5 ml tube, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C before further processing. Batches of oocytes for ChIP-seq were treated as described below.

Immunofluorescence.

Mouse embryos were immunostained using an adapted protocol from ref. 31 in 96-well plates. Briefly, embryos were subjected to thinning of the zona pellucida using acidic DPBS (pH 2.5), and fixation in 2% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. Embryos were permeabilized in 0.3% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.02% NaN3 PBS solution. Blocking was carried out in 0.3% BSA, 0.01% Tween-20, and 0.02% NaN3 in PBS. Embryos were incubated in blocking solution with 1:200 H3K4me3 antibody (Merck Millipore, 04–745) for 60 min at room temperature. After further blocking, embryos were finally incubated with goat anti-rabbit Alex Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, A-11008) or Alexa Fluor 568 for morpholino injected embryos (Invitrogen, A-21069) at 1:200 dilution and placed on a slide in SlowFade Gold with DAPI (Invitrogen). Quantitative measurements of H3K4me3 were obtained using a Zeiss Axio Observer epi-fluorescence microscope with a Coolsnap HQ2 camera. Confocal images were obtained with a Zeiss Axio Observer LSM 710 confocal microscope. Images were processed and quantified in Axiovision and ImageJ software.

Morpholino targeting of Kdm5a and Kdm5b in the early embryo.

Isolated zygotes were injected at 0.5 dpc (days post coitum) with either fluorescein-tagged morpholino oligonucleotides (Gene-tools) targeted at Kdm5a (5’-TGACGGCCACCAAAGCCCTCTCA-3’) and Kdm5b (5’-AGCACAGGGCAGGCTCCGCAACC-3’) or five base mismatch control morpholinos for Kdm5a (5’-TGAaGGaCACaAAAcCCCTaTCA-3’) and Kdm5b (5’-AcCAaAGGGaAGGaTCCGaAACC-3’). Embryos were cultured in G1 plus media (Vitrolife) until late 2-cell (35 h after hCG) and fixed in 2% PFA. Embryos were further treated as described above.

Protein extracts from two-cell embryos.

Lysates from 132 two-cell embryos were prepared adding lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 20% glycerol, 0.5% NP40, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.150 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF, 1 × PIC, 1% SDS) to a final volume of 7 μl. Embryos were lysed on ice for 30 min with occasional vortexing and spinning. Embryos were vortexed and spun down at the end and were frozen on dry ice. Samples were subsequently thawed, sonicated on ultrasound bath for 1 min and centrifuged at 16,000g for 10 min followed by transfer of 5 μl supernatant to a new tube.

Automated western immunoblotting.

The simple western immunoblots were performed on a PeggySue (ProteinSimple) using the Size Separation Master Kit with Split Buffer (12–230 kDa) according to the manufacturer’s standard instruction, using the following abtibodies: anti-Kdm5A (CellSignalling, 3876), anti-Kdm5b (Abcam, 181089) and anti-β-actin (Abcam, ab8227). The Compass software (ProteinSimple, version 2.7.1) was used to program the PeggySue-robot and for presentation (and quantification) of the western Immunoblots. Output data was displayed from the software-calculated average of seven exposures (5–480 s).

Cell lines.

Human NCCIT pluripotent embryonal carcinoma cell line was obtained from ATCC (CRL-2073), and cultured according to ATCC specifications. Mouse E14 ES cells were obtained from a stock at passage P2 equal to what was used for the mouse ENCODE project, and cultured according to that specified by the mouse ENCODE project (https://www.encodeproject.org/biosamples/ENCBS171HGC/). Cell lines were validated by ChIP-seq confirming species and a highly conserved profile. Cell lines were never passaged passed passage 15 for the work described here. Mycoplasma testing was carried out on a regular basis and both of the cell lines were free for Mycoplasma.

ChlP-seq.

Cross-linking of oocytes, 2-cell or 8-cell embryos.

We added 50 μl M2 medium to a 0.6-ml tube. Embryos were then added and let settle to the bottom. Volume was controlled by eye by comparing to another 0.6-ml tube with 50 μl M2 medium and adjusted with mouth pipette to 50 μl. 50 μl of PBS with 2% formaldehyde was added to get a 1% final concentration and vortexed carefully, incubated at room temperature for 8 min, and vortexed once more. 12 μl of 1.25 M glycine stock (final concentration 125 mM) was added, mixed by gentle vortexing, incubated for 5 min at room temperature, and vortexed once during the incubation step. This was centrifuged at 700g for 10 min at 4 °C in a swinging-bucket rotor with soft deceleration settings and washed twice with 400 μl ice-cold PBS. A volume of 10 μl was left after the last wash, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Binding of antibodies to paramagnetic beads.

The stock of paramagnetic Dynabeads Protein A was vortexed thoroughly to ensure the suspension was homogenous before pipetting. 100 μl of Dynabeads stock solution was transferred into a 1.5-ml tube, which was placed in a magnetic rack and the beads captured on the tube wall. The buffer was discarded, and the beads washed twice in 500 μl of RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate) and resuspended in RIPA buffer to a final volume of 100 μl. 96 μl of RIPA buffer was aliquoted into 200-μl PCR tubes on ice, the washed beads were vortexed thoroughly, and 2 μl of bead suspension and 2 μl of either antibody against H3K4me3 (Merck Millipore, 04–745) or to H3K27ac (Active Motif, catalogue number AM39133) was added to each of the 200 μlPCR tubes. This was then incubated at 40 r.p.m. on a ‘head-over-tail’ tube rotator for at least 4 h at 4 °C.

Chromatin preparation.

The desired number of cross-linked and frozen pools of embryos was removed from −80 °C storage and placed on dry ice in an insulated box (for example, four tubes with a total number of 1,000 2-cell embryos). 10 minutes of cross-linking was carried out during thawing as follows: one tube was moved at the time from dry-ice to ice for 5 s, and any frozen droplets quick pelleted by a brief spin in a mini-centrifuge. 100 μl of 1.1% formaldehyde solution was added (PBS with 1 mM EDTA, 1.1% formaldehyde, 20 mM sodium butyrate, 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail). The tubes were incubated for 10 min at room temperature and vortexed gently twice. 7 μl was added of 2.5 M glycine, vortexed gently and incubated for 5 min before the tube was moved to ice. Tubes were centrifuged at 750g for 10 min at 4 °C in a swinging-bucket rotor with soft deceleration settings, then washed twice with 400 μl PBS with 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM sodium butyrate, 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail. A volume of 10 μl was kept after the last wash. For four tubes, a total of 120 μl of 0.8% SDS lysis buffer with 20 mM sodium butyrate, 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail was used. First 60 μl, then 2 × 30 μl was used for two consecutive rounds of washing through the four tubes by pipetting. The same tip was used and the entire volume (160 μl) left in the last of the four tubes. The sample was sonicated for 5 × 30 s using a UP100H Ultrasonic Processor (Hielscher) fitted with a 2-mm probe. We allowed 30 s pauses on ice between each 30 s session, using pulse settings with 0.5 s cycles and 27% power. 170 μl RIPA Dilution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 175 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.625 mM EGTA, 1.25% Triton X-100, 0.125% Na-deoxycholate, 20 mM sodium butyrate, 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail) was added. The sample was centrifuged at 12,000g in a swinging-bucket rotor for 10 min at 4 °C and the supernatant transferred to a 1.5-ml tube. 200 μl of RIPA Dilution buffer was added to the pellet and sonicated 3 × 30 s. The sample was centrifuged at 12,000g in a swinging-bucket rotor for 8 min, then the supernatant was removed and mixed well with the first supernatant, resulting in a total volume of about 530 μl of ChIP-ready chromatin.

Immunoprecipitation and washes.

Pre-incubated antibody-bead complexes were washed twice in 130 μl RIPA buffer by vortexing roughly. The tubes were centrifuged in a mini-centrifuge to bring down any solution trapped in the lid and antibody-bead complexes were captured in a magnetic rack cooled on ice. 250 μl of chromatin was added to each of anti H3K4me3 or H3K27ac reactions, and 25 μl kept for input control. 2 μl of cross-linked recombinant histone octameres and 1.25 μg of non-immunized rabbit IgG was immediately added to ChIP reactions, then incubated at 4 °C, 40 r.p.m. on a ‘head-over-tail’ rotator for 30 h. The chromatin-antibody-bead complexes were washed four times in 100 μl ice-cold RIPA buffer. The concentration of SDS and NaCl was titrated for each antibody to find optimal conditions for maximized signal-to-noise ratio. For H3K4me3, we washed 1 × RIPA buffer with 0.2% SDS and 300 mM NaCl, 1 × RIPA buffer with 0.23% SDS and 300 mM NaCl followed by 2× RIPA buffer with 0.2% SDS and 300 mM NaCl. For H3K27ac, we washed 4 × RIPA buffer with 0.1% SDS and 140 mM NaCl. Each wash involved rough vortexing on full speed, repeated twice with pauses on ice in between. Next, a wash in 1 × 100 μl TE and tube shift was carried out as previously described32,33.

DNA isolation and purification.

We removed TE and added 150 μl ChIP elution buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA. 1% SDS, 30 μg RNase A) and incubated at 37 °C, 1 h at 1,200 r.p.m. on a Thermomixer. 1 μl of Proteinase K (20 mg ml−1 stock) was added to each tube and incubated at 68 °C, 4 h at 1,250 r.p.m. Eluate was transferred to a 1.5-ml tube. A second elution with 150 μl was performed for 5 min and pooled with the first supernatant. ChIP DNA was purified by phenol-chloroform isoamylalcohol extraction, ethanol-precipitated with 10 μl acrylamide carrier as described previously32,33 and dissolved in 10 μl EB (10 mM Tris-HCl).

Library preparation and sequencing.

ChIP and input library preparations were carried out according to the ThruPLEX (Rubicon Genomics) procedure with some modifications, including increased incubation times for the library purification and size selection. 12 ChIP libraries were pooled before AMPure XP purification and allowed to bind for 10 min after extensive mixing. Increased elution time, thorough mixing and the use of a strong neodymium bar magnet allowed for high recovery in elution volumes of 25 μl buffer EB. Sequencing procedures were carried out as described previously according to Illumina protocols with minor modifications (Illumina,). We sequenced all P12, P15, oocyte, 2-cell, and 8-cell ChIP-seq libraries as paired-end and all NCCIT ChIP-seq libraries as single-end. Mouse ES cell ChIP-seq libraries were sequenced as paired-end and single-end and the results were combined after mapping for analysis. Single-end and paired-end library information for all samples have been deposited in the GEO database (GSE72784).

Sequence read alignment.

We aligned single- and paired-end μChIP-seq reads from H3K27ac and H3K4me3 experiments to the mm10 reference genome by using BWA-mem34. For human ChIP-seq samples performed with human NCCIT cells, we aligned reads to the hg19 reference genome using BWA-mem. Unmapped and non-uniquely mapped reads were removed. We also removed PCR duplicate reads with Picard. H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data for heart, liver, and cerebellum were downloaded from the mouse ENCODE project26. H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data for sperm was downloaded from GEO database under accession number GSE42629 (ref. 23).

Small-scale RNA-seq of 2-cell embryos and various controls injected with Kdm5a and Kdm5b morpholinos.

Culture and collection of embryos.

2-cell stage embryos (2 × 25 embryos) were transferred to 350 μl of Buffer RLT (QIAgen RNaseay) (including β-Me according to manufacturer’s description) in a 1.5 ml low-binding tube and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Zygotes were cultured in M16 medium. For α-amanitin treatment the medium contained 10 μg ml−1 α-amanitin (Sigma, A2263).

RNA extraction with QIAGENRNeasy Micro Kit.

RNAs were extracted by following QIAGEN RNeasy Micro handbook. Briefly, 25 embryos were disrupted by addition of buffer RLT followed by homogenization of the lysate. One volume of 70% EtOH was added to the lysate, transferred to an RNeasy MinElute spin column, and centrifuged for 15 s. Next, 350 μl of buffer RW1 from QIAGEN RNeasy Micro Kit was added to wash the RNeasy MinElute spin column by 15 s centrifugation. 10 μl DNase I mix was added to the RNeasy MinElute spin column membrane (10 μl DNase + 70 μl buffer RDD) and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The spin column membrane was washed twice with 500 μl buffer RPE from the QIAGEN RNeasy Micro Kit followed by 500 μl of 80% EtOH. 14 μl RNase-free water was added directly to the centre of the spin column membrane and centrifuged to elute RNA.

RNA amplification with NuGEN Ovation RNA-seq system V2.

Extracted RNA was amplified by following the NuGEN ovation RNA-seq handbook. Briefly, step 1 was first-strand cDNA synthesis. 2 μl of First Strand Primer Mix from NuGEN Ovation RNA-seq system V2 was added to a PCR tube followed by addition of 5 μl of total RNA sample, and the thermal cycler for primer annealing was run (65 °C for 2 min, held at 4 °C). 3 μl of the First Strand Master Mix from NuGEN Ovation RNA-seq system V2 was added to each tube and thermal cycler for first strand synthesis was run (4 °C for 1 min; 25 °C for 10 min; 42 °C for 10 min, 70 °C for 15 min, held at 4 °C). Step 2 was second-strand cDNA synthesis. 10 μl of the second-strand mix from NuGEN Ovation RNA-seq system V2 was added to each first-strand reaction tube and the thermal cycler was run (4 °C for 1 min; 25 °C for 10 min; 50 °C for 30 min; 80 °C for 20 min; hold at 4 °C). Step 3 was purification of cDNA with Agencourt RNAClean XP beads. Step 4 was SPIA amplification. 40 μl of the SPIA master Mix from NuGEN Ovation RNA-seq system V2 was added to each tube containing the double-stranded cDNA bound to the Agencourt RNAClean XP beads, and the thermal cycler was run to amplify double-stranded cDNA (4 °C for 1 min; 47 °C for 60 min; 80 °C for 20 min, held at 4 °C). The tubes were transferred to the magnet and 40 μl of the supernatant containing the SPIA cDNA was transferred to a new tube, followed by SPIA cDNA purification with QIAGEN MinElute reaction cleanup kit.

Library preparation and sequencing.

The volume and concentration of purified SPIA cDNA to 500 ng in 100 μl and sonicated SPIA cDNA with Covaris M220 ultrasonicator was adjusted to 400 bp DNA fragment size. Library preparation was carried out according to TruSeq library preparation. Sequencing procedures were carried out as described previously according to Illumina HiSeq2500 protocols with minor modifications (Illumina).

Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing of immature oocytes.

DNA methylation libraries of growing oocytes obtained from day 12 (P12) and day 15 (P15) mice were constructed with a modified library protocol from ref. 2. Briefly, 100–500 embryos were lysed in 5 μl lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM KCl, 1 mg ml−1 proteinase K (QIAGEN)) for 1.5 h at 56 °C. followed by heat-inactivation for 30 min at 75 °C. 45 μl nuclease-free water and 0.5% Lamda DNA (Promega) spike-in was added into the lysate. DNA was fragmented with Covaris M220 ultrasonicator and incubated at 37 °C to reduce volume to 30 μl. The fragmented DNA was end-repaired by incubating with 5 μl end-repair enzyme mixture (3.5μl T4 DNA ligase buffer (NEB), 0.35 μl 10 mM dNTP, 1.15 μl NEBNext End Repair Enzyme Mix (NEB)) for 30 min at 20 °C, followed by heat-inactivation for 30 min at 75 °C. Then, 5 μl of dA-tailing mixture (0.5 μl T4 DNA ligase buffer, 1 μl Klenow exo-(NEB), 0.5 μl 100 mM dATP and 3 μl nuclease free water) was added and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by heat-inactivation for 30 min at 75 °C. Finally, 10 μl ligation mixture (1 μl T4 DNA ligase buffer, 0.5 μl 100 mM ATP, 1.5 μl 50 mM cytosine methylated Illumina adaptor, 2 μl T4 DNA ligase (NEB) and 5 μl nuclease-free water) was added and incubated at 16 °C overnight. 100 ng Carrier RNA (Ambion) was added into the tube. Bisulfite conversion reaction was performed with the EZ DNA methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purified DNA was then amplified with 6 cycles PCR by using KAPA HiFi HotStart Uracil+ DNA polymerase (KAPA). Amplified DNA was purified with Ampure XP beads (Beckman) to discard the short fragments and adaptor-self ligations. Then, another round of 6–8 cycles of PCR was performed to obtain sufficient molecules for sequencing. Sequencing procedures were carried out as described previously according to Illumina HiSeq2500 protocols with minor modifications (Illumina).

Read filtering, alignment, quantification of methylation levels.

Reads were trimmed by Trimmomatic35 with default parameters to remove the reads containing adapters and showing low quality. Trimmed reads were aligned by using Bismark (V12.5)36 Bisulfite Mapper against the mouse reference genome mm10 with parameters: −N 1 −score_min L,0,−0.6. Duplicate reads were removed with Picard after splitting aligned reads into Watson and Crick strands. CpG methylation level was extracted with Samtools mpileup. Strands were merged to calculate the CpG methylation level per dinucleotide CpG site. Methylation level was calculated for each site spanned by at least 4 reads.

Gene annotation.

During RNA-seq data analysis we used GENCODE gene annotation v3. We considered all level 1 and 2 genes and included level 3 protein-coding genes.

RNA-seq analysis.

To define gene expression levels, mouse oocytes, 2-cell, and 8-cell stage embryos RNA-seq data sets were downloaded from the GEO database with accession number GSE44183 (ref. 8). Mouse ES cell RNA-seq data were downloaded from GEO database with accession number GSE39619. RNA-seq reads were aligned to the mm10 reference genome using BWA-mem. Unmapped and non-uniquely mapped reads were removed. Gene expression values were obtained based on GENCODE annotation v3 and normalized to fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped (FPKM) values using Cufflinks37.

DNA methylation analysis.

Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) data from sperm was obtained from GEO database with accession number GSE56697 (ref. 2). Oocyte DNA methylation data was obtained from GEO database under accession number GSE56879 (ref. 19). We combined all data from 12 individual MII oocytes and the bulk oocyte sample. Deeply sequenced results were used for MII oocyte with number 2 and 5. WGBS data for GVO and NGO stage oocytes were obtained through personal communication with the authors22.

Identification of broad H3K4me3 domains in oocyte.

We performed broad peak calling for H3Kme3 in oocytes based on MACS2 broad peak calling algorithm with default parameters (-format = BAM -g mm -m 5 50 -p 1e-5 -broad) followed by combining adjacent peaks within 5 kb. We determined the optimal distance to combine adjacent peaks on the basis of the number of broad H3K4me3 domains at varying distance thresholds. At 5 kb distance threshold, the number of broad domains became stable as shown in Extended Data Fig. 5b. On the basis of the location of transcription start sites (GENCODE v3), we classified broad H3K4me3 domains into two groups as TSS-containing and non-TSS-containing domains.

An adjustment of H3K4me3 RPKM values.

The basic idea of RPKM values is to calculate relative ChIP signal enrichment for a given genomic region compared to the entire genome to normalize different sequencing depth between samples. This approach is reasonable when the total amount of ChIP DNA is similar between samples, and in general the fraction of genomic regions covered by each histone modification mark is similar between samples such as that H3K4me3 marks around 1–3% of the human genome in cells/tissues assessed to date. Therefore by using RPKM values, one can simply avoid a potential bias caused by different sequencing depth. However, if a sample shows an extraordinary ChIP signal distribution, the sample with much larger genomic regions covered with, for example, H3K4me3 tends to show relatively lower RPKM values owing to the large amount of total ChIP signal. In oocytes, we observed such notably broadly distributed H3K4me3 signals, resulting in lower RPKM values than other samples when we consider the top-ranked promoter regions in terms of H3K4me3 signal (Extended Data Fig. 5d). In this regard, to compare H3K4me3 signals fairly between samples, we need to adjust H3K4me3 RPKM values in each cell type. In order to adjust H3K4me3 RPKM values between samples, we used the top-5,000 ranked promoters in terms of H3K4me3 level as internal control regions during H3K4me3 normalization. We calculated H3K4me3-adjustment scaling factors on the basis of the H3K4me3 ChIP signals at the top 5,000 ranked promoters, with the assumption that the promoters with the highest H3K4me3 levels in each cell type represent fully H3K4me3-modified promoters and have similar H3K4me3 signal levels. In support of this assumption, all oocyte and embryo samples represent highly homogenous cell populations, thus it is plausible that most or all cells carry the H3K4me3 mark at the cell-type-specific top-ranked promoters. Furthermore, ChIP conditions were kept the same for all samples. As expected, we observed very similar H3K4me3 signals between samples exhibiting only canonical H3K4me3 patterns when we consider the same number of top-ranked promoters (Extended Data Fig. 5e). On the basis of this observation, we calculated H3K4me3 RPKM adjustment scaling factors for different numbers of the top-ranked promoters (Extended Data Fig. 5f). The scaling factors were calculated by dividing median H3K4me3 RPKM values at the top-ranked promoters in each sample by median H3K4me3 RPKM value at the top-ranked promoters in mES cells. Importantly, the scaling factors are very robust regardless of the number of promoters analysed, indicating that there is a systematic bias caused by different genomic coverage of H3K4me3. Indeed, the adjustment scaling factors are supported by the qPCR-quantified amount of ChIP DNA that is precipitated in each experiment (Supplementary Table 2). Therefore, in this study, we defined the scaling factors based on the top 5,000 most highly ranked promoters.

Maternally expressed genes within broad H3K4me3 domains.

We downloaded a list of maternally expressed genes from GEO database under accession number GSE45719 (ref. 7). We excluded all genes expressed in oocytes to allow us to distinguish maternally expressed genes in the early embryo. We considered genes with less than 0.3 FPKM values as not expressed. On the basis of the extracted genes, we tested whether maternally expressed genes are enriched within broad H3K4me3 domains. The number of genes expected by chance was calculated on the basis of the fraction of all genes located within broad H3K4me3 domains. The significance of enrichment of maternally expressed genes was calculated by Fisher-exact tests. P values were 1.9−8, 2.9−9, 1.6−4, 8.2−6, 2.8−4, 8.0−4 for zygote, early 2-cell-, mid 2-cell-, late 2-cell-, 4-cell-, and 8-cell-stage embryos, respectively.

ZGA genes and oocyte-specific genes.

We used a predefined ZGA gene list obtained from a previous study5. The list of oocyte-specific genes (denoted as maternal RNA) was also obtained from the same study after excluding any genes showing less than 0.3 FPKM values in oocytes.

Visualization of heat maps and superimposed tracks.

Visualization and preceding analysis was done using EaSeq and its integrated tools38. Heat maps were generated using the ‘HeatMap tool, and superimposed tracks were generated using the ‘FillTrack’ tool. Data were imported using default settings and all values were normalized to FPKM and scaled as described above (see An adjustment of H3K4me3 RPKM values‘). Distances from and orientation of each TSS to the nearest domain centre were calculated using the ‘Colocalize’ tool, and the ‘Sort’ tool was used to order the TSS in the heat maps according to these distances or for ordering heat maps according to domain size.

Clustering analysis of H3K4me3 and DNA methylation during development.

We only considered broad H3K4me3 domains that span more than 5 kbp DNA to avoid any overlapping information at domain boundaries between 5; and 3;ends of domains. Clustering of domain boundaries was carried out by: (1) quantifying normalized and scaled H3K4me3 RPKM values for P12, P15, and oocyte samples at a set of regions corresponding to the most proximal 2 kbp within the boundary and average DNA methylation frequency for NGO, P12, P15, GVO and oocyte samples at a set of regions corresponding to the most proximal 2 kbp outside of the domain boundaries using the EaSeq (ref. 38) ‘Quantify’-tool (settings: ‘Start = Center, offset = −1000, Fixed width’, ‘End = Center, offset = 1000, Fixed width’, ‘Normalize to reads pr. million, checked’, ‘Normalize to signal size of, unchecked’, ‘Normalized counts to fragments, checked’, ‘Present values as Z-scores, unchecked’); then (2) clustering the boundaries based on this quantified signal using EaSeq’s ‘ClusterP’-tool (settings: ‘Log-Transform, unchecked’, ‘Normalize parameters to average signal’ ‘k-means clustering, checked’, ‘k = 10, ‘g = 0’). The order of the clusters was changed manually. Distances from each boundary to nearest CGI were calculated using a set of CGIs downloaded from the UCSC table browser and ‘Colocalize’-tool.

Distal cis-regulatory elements prediction.

We predicted distal cis-regulatory elements on the basis of H3K27ac μChIP-seq results. We combined two biological replicates for each cell type and called H3K27ac peaks using MACS2 with the following parameters (-format = BAM -g mm -m 5 50 -p 1e-5). To directly compare the activity of distal cis-regulatory elements between cell types, we defined putative distal cis-regulatory elements by combining all H3K27ac peaks from oocytes, 2-cell and 8-cell embryos and ES cells after excluding chrY, chrM, and any peaks within 2.5 kb from known transcription start sites (GENCODE v3). The activity for each distal cis-regulatory element in each cell type was defined by taking the log2 ratio between H3K27ac ChIP-seq and input RPKM values.

Identification of stage-restricted distal cis-regulatory elements.

On the basis of the activity of distal cis-regulatory elements, we performed k-means clustering. 20 clusters were defined with Euclidian distance metric followed by reordering clusters manually. On the basis of the clustered patterns, we identified stage-restricted distal cis-regulatory elements.

Identification of nearby genes of distal cREs.

We defined nearby genes of each cRE when the distance between gene TSS and each distal cRE is less than 15 kb. Similarly, in order to define nearby distal cREs for ZGA genes, we combined all distal cREs within 15 kb from each ZGA gene TSS.

Transcription factor motif enrichment and GREAT analysis for each developmental stage.

We used HOMER to find enriched transcription factor motif sequences in distal cREs for each developmental stage. We also performed GREAT39 analysis for each class of stage-restricted distal cREs using the settings ‘single nearest gene’, ‘within 300 kb’ of the enriched H3K27ac region, and no curated regions.

Identification of genes with a certain transcription factors in nearby cREs.

In order to identify genes with a certain transcription factors in nearby cREs, we carried out STORM40 motif search with −f −t 0.9 parameters for nearby cREs within 15 kb from each TSS. Each transcription factor motif position weight matrix was obtained from HOMER motif search41 results. The genes with a certain transcription factor in nearby cREs were called if any cREs within 15 kb from the TSS matched with the corresponding transcription factor motif sequence.

Analysis of gene expression changes resulting from Kdm5a and Kdm5b MO injection.

We called downregulated genes between Kdm5a and Kdm5b MO injected and control MO injected 2-cell embryos when gene FPKM values were 1.5-fold or more reduced in both of the two biological replicates. Additionally, we called experimental stage specific ZGA genes when gene FPKM values were twofold or more reduced in α-amanitin treated embryos as compared to control MO injected embryos. The rational for identifying the experimental stage-specific ZGA genes comes from the observation that the composition of the trans-criptome changes dramatically and rapidly during the 2-cell stage7. Although α-amanitin-treated embryos blocked polymerase II transcription from the early 1-cell stage onwards, de novo transcription-independent degradation of maternal RNA may still occur. Therefore, they provide a well-suited control for defining the experimental stage-specific ZGA genes when compared to the control morpholino-injected embryos. As a result, we identified 7,132 putative experimental stage-specific ZGA genes and these genes are significantly overlapped with the ZGA gene list obtained from a previous study5 (hypergeometric P value is 0). KDM5A- and KDM5B-depleted embryos showed that 1,303 ZGA genes are downregulated among 7,132 experimental stage-specific ZGA genes, whereas 980 non-ZGA genes are downregulated among 25,155 genes.

Visualization of genome browser tracks.

We visualized ChIP−seq and RNA-seq data on the basis of raw read depth after converting aligned bam files to wig files using genomeCoverageBed and wigTobigWig utilities.

Extended Data

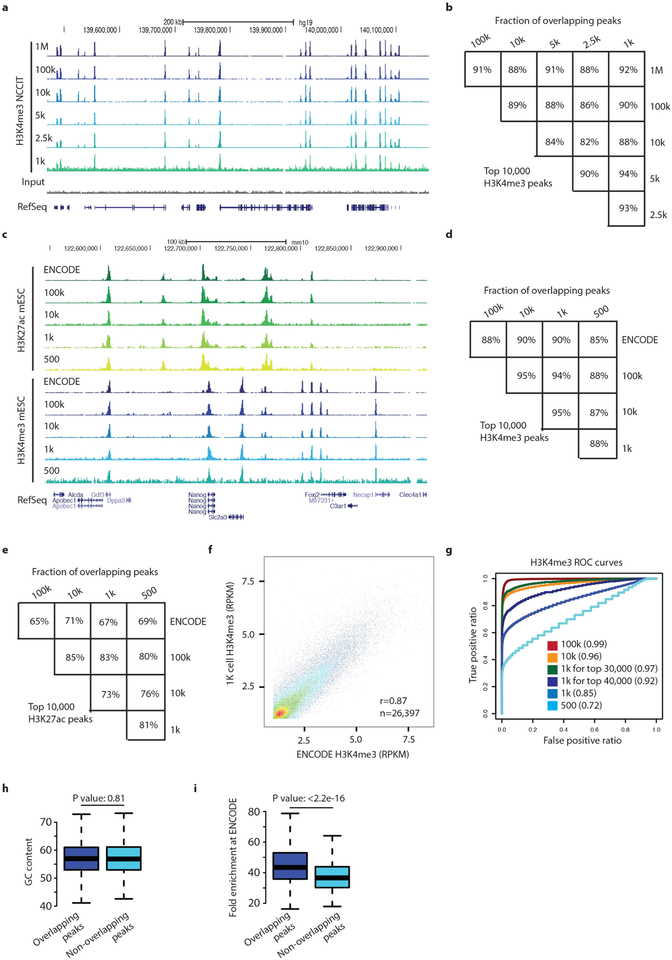

Extended Data Figure 1 |. Proof of principle for μChIP-seq in human NCCIT cells and mouse ES cell.

a, Genome browser snapshot for H3K4me3 μChIP-seq with different numbers of human NCCIT cells. The number of cells used is shown at the beginning of each genome browser track. Input ChIP-seq and RefSeq gene annotation are shown in the two last rows. b, The percentage of overlapping H3K4me3 peaks between the top-10,000 H3K4me3 peaks detected from multiple μChIP-seq experiments with different numbers of human NCCIT cells. c, A genome browser snapshot for H3K27ac and H3K4me3 μChIP-seq in mouse E14 ES cells. ENCODE ChIP-seq is also shown. Cell number in μChIP-seq experiments ranged from 100,000 to 500 cells. d, The percentage of overlapping H3K4me3 peaks between top 10,000 H3K4me3 peaks when comparing multiple μChIP-seq experiments performed with different numbers of mouse ES cells. Applying μChIP-seq to 1,000 cells allowed detection of 90% of ENCODE peaks and 94% of peaks from large scale ChIP-seq from the same ES-cell culture batch. e, The percentage of overlapping H3K27ac peaks between multiple experiments using different numbers of mouse ES cells. We considered the top 10,000 H3K27ac peaks in each sample. The sample named ENCODE are H3K27ac peaks from the ENCODE dataset. f, A scatter plot comparing RPKM values obtained from 1,000-cell μChIP-seq and ENCODE chlP-seq results using an H3K4me3 antibody in mouse ES cells. Each dot represents an H3K4me3 peak identified using the H3K4me3 μChIP-seq results (n = 26,397). Pearson correlation coefficient is also shown. g, Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve plots for H3K4me3 peaks identified from multiple μChIP-seq experiments. True H3K4me3 peaks were defined using ENCODE H3K4me3 ChIP-seq result and false H3K4me3 peaks were created by randomly selecting genomic regions. For the 1,000-cell μChIP-seq result we also calculated ROC scores for two additional subsets of true H3K4me3 peaks; the top 30,000 and 40,000 H3K4me3 ENCODE peaks. h, Box plots of GC content comparing 500-cell H3K4me3 ChIP-seq detected and undetected ENCODE H3K4me3 peaks (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test P = 0.81). i, Box plots ofENCODE H3K4me3 signal comparing 500-cell H3K4me3 ChIP-seq detected and undetected H3K4me3 peaks (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test P < 2.2−16). Whiskers correspond to the highest and lowest points within the 1.5 × interquartile range (h, i).

Extended Data Figure 2 |. Reproducibility of μChIP-seq experiments.

a, Genome browser snapshots of H3K4me3 and H3K27ac μChIP-seq results in MII oocytes, 2- and 8-cell embryos and ES cells. For each histone-modification mark, we generated two biological replicates. b, Genome browser snapshots of H3K4me3 μChIP-seq results from P12 and P15 oocytes. We generated two biological replicates. c, d, Bar plots show the Pearson correlation coefficient between two biological replicates for H3K4me3 (c) and H3K27ac (d). Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated using RPKM values for 1-kb-binned regions of the whole genome.

Extended Data Figure 3 |. Relationship between promoter H3K4me3 and expression.

a, Box plots for H3K4me3 RPKM values at promoter regions after grouping promoters into 10 equally sized groups according to gene expression levels. b, Box plots for gene expression levels for each group are shown. Whiskers correspond to the highest and lowest points within the 1.5 × interquartile range (a, b). c, Fraction of the mouse genome covered by H3K4me3 peaks at different developmental stages and in various adult tissues26. H3K4me3 peaks were defined using default MACS2 peak call settings except for oocyte. Oocyte H3K4me3 peaks were defined using MACS2 broad peak call settings. d, Scatter plot of H3K4me3 signals in 1kb bins between oocyte and 2-cell-stage embryos. Genomic regions marked with a strong H3K4m3 signal in the oocyte show reduced signal in 2-cell-stage embryos. e, Fraction of the mouse genome covered by H3K27ac peaks using default MACS2 peak call settings for different developmental stages.

Extended Data Figure 4 |. H3K4me3 and DNA staining in oocytes, zygotes and cleavage-stage embryos.

a, Panel from Fig. 1d with consistently adjusted brightness and contrast to allow visual observation of H3K4me3 signal following rapid loss at the late 2-cell stage. The signal of the strongly staining stages appears saturated due to this. b, c, Quantification of H3K4me3 and DNA staining by integrated H3K4me3-specific and DAPI-specific fluorescence intensity, respectively, over pronuclei and nuclei was determined using an epifluorescence microscope and the ImageJ software. The nuclear DNA content of ‘early’ and ‘late’ 2-cell embryos reveals that DNA synthesis is almost completed at the ‘early’ time point. Therefore suggesting an active mechanism of H3K4me3 removal rather than passive dilution over DNA replication (n = 18, 18, 20, 41, 18, 74 for respective time points; error bars show s.e.m.).

Extended Data Figure 5 |. Broad H3K4me3 domain calling.

a, Genome browser snapshot of H3K4me3 μChIP-seq and RNA-seq signals. The H3K4me3 μChIP-seq signal in oocytes shows enrichment over broader regions compared to sperm, 2- and 8-cell embryos and mouse ES cells (mESCs). The broad H3K4me3 domain call is shown as a green bar below the oocyte H3K4me3 track. The TSS of Foxa1 (ZGA gene) is located in a broad H3K4me3 domain. The Foxa1 gene becomes expressed in 2- and 8-cell embryos. b, Decreasing fraction of H3K4me3 domains in oocytes when increasing the distance threshold to merge adjacent H3K4me3 peaks. At 5 kb (asterisk), this fraction becomes stable, which is used as the threshold to call broad H3K4me3 domains in oocytes. c, Histogram showing fraction of H3K4me3 domains of various breadth for TSS-containing (n = 15,608) and non-TSS-containing (n = 47,934) domains. TSS-containing H3K4me3 domains tend to be broader (median, 12 kb) than non-TSS-containing domains (median, 3.7 kb) (P value < 2.2−16, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). d, An anti-correlated relationship between genomic regions covered by H3K4me3 (x axis) and median-input-normalized H3K4me3 ChIP-seq RPKM values at 5,000 top-ranked promoters (y axis). The samples more widely covered by H3K4me3 tend to show relatively lower H3K4me3 RPKM values. e, Line plots are shown for median input normalized H3K4me3 RPKM values (y axis) with corresponding number of top-ranked promoters (x axis). When the genomic coverage of H3K4me3 is similar between samples (liver, cerebellum, and heart) the median of input normalized H3K4me3 RPKM values are highly consistent between samples at a given number of top-ranked promoters. f, Robustness of H3K4me3 RPKM adjustment factor. y axis indicates H3K4me3 RPKM adjustment factor for each cell type. Mouse ES cell data are used as a reference (that is, adjustment factor = 1). x axis indicates number of top-ranked promoters that was used to calculate H3K4me3 RPKM adjustment factor. The adjustment factors are very robust regardless of number of top-ranked promoters considered. g-i, Genome browser tracks for several loci show H3K4me3 μChIP-seq for oocytes, 2-cell and 8-cell embryos and mouse ES cells. y axis indicates auto scale for H3K4me3 raw reads (g), fixed scale for H3K4me3 RPKM (h), and fixed scale for H3K4me3 signal after applying the adjustment factor (i).

Extended Data Figure 6 |. Establishment of broad H3K4me3 domains in oocytes and removal in the early embryo.

a, b, Heat maps of H3K4me3 raw read counts normalized by total read numbers in indicated stages for non-TSS (a) and TSS-containing H3K4me3 domains (b) ordered according to increasing size. Horizontal positions reflect spatial distribution relative to the domain centre, and densities correspond to H3K4me3 signal intensity. c, Genome browser snapshot of H3K4me3 μ ChIP-seq from P12, P15 and MII oocytes. d, Superimposed tracks of H3K4me3 signal in P12, P15 and MII oocytes at the boundaries of non-TSS-containing H3K4me3 domains. The y axes show H3K4me3 signal, colouring reflects the total count of domains with a given signal intensity, and horizontal positions reflect spatial distribution relative to the domain border.

Extended Data Figure 7 |. DNA methylation level within and outside broad H3K4me3 domains.

a, Percentage of broad domains displaying hypomethylated (<0.25), hypermethylated (>0.75) and intermediate (>0.25 and <0.75) levels within TSS-containing domains, non-TSS-containing domains, and outside broad domains. b, Histograms of average DNA methylation levels within TSS-containing (n = 15,135) and non-TSS-containing domains (n = 35,567), and outside of domains (n = 61,674). Domains containing at least 5 covered CpGs were included. c, Bar plots displaying the fraction of ZGA genes5 and genes not expressed that reside in broad H3K4me3 domains. (***P < 10−3, Fisher’s exact test). d, e, Heat maps of H3K4me3 and DNA methylation signal for indicated oocyte stages for non-TSS-containing H3K4me3 domains ordered according to increasing sizes. Horizontal positions reflect spatial distribution relative to the domain centre, and densities correspond to H3K4me3 signal intensity (d) or CpG methylation level (e). NGO, non-growing oocyte; GVO, germinal vesicle oocytes. f, Bar plots displaying the number of genes expressed from the maternal allele for genes that reside in broad H3K4me3 domains. The maternally expressed genes are significantly enriched within broad H3K4me3 domains compared to what would be expected by chance (***P < 10−3, Fisher’s exact test). g, k-means clustered heat maps of H3K4me3 and DNA methylation signal for P12, P15 and MII oocytes at H3K4me3 domain boundaries. Boundaries of domains larger than 5 kbp were clustered according to H3K4me3 and DNA methylation signals at the 2-kbp regions flanking the boundaries, and densities correspond to H3K4me3 signal or CpG methylation level. C1–C10, Cluster 1–10. h, i, Box plots for distance from domain boundary to the nearest CpG island (h) and bar plots for fraction of TSS-containing broad domains (i) in each cluster. Whiskers correspond to the highest and lowest points within the 1.5 × interquartile range. j-l, Line plots are shown for average DNA methylation profiles at both 5’ and 3’ end of ZGA gene TSS-containing broad domains (n = 2,313) (j) and non-TSS-containing broad domains (n = 12,691) (k) and other TSS-containing domains (remaining TSS-containing domains after excluding ZGA gene TSS-containing domains, n = 6,390) (l). Domains larger than 10 kb were included. y axis indicates DNA methylation levels and x axis indicates distance relative to the domain boundaries. Black, green, blue, and orange colour indicates sperm, oocyte, P15, and P12, respectively (P < 2.2−16, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of sperm DNA methylation within broad domains between ZGA gene- and non-TSS/other TSS-containing domains).

Extended Data Figure 8 |. Identification of stage-restricted cREs.

a, Box plots of the shortest distance between 2-/8-cell stage restricted cREs (n = 33,609) and between randomly selected cREs (n = 33,609). 2-/8-cell common cREs are significantly closer to each other than other cREs (P < 2.2−16, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). b, H3K27ac levels at putative cREs in the vicinity of non-ZGA genes (n = 13,334). c, Enriched motifs found in different groups of stage restricted cREs. d, Box plots of gene expression values (FPKM) for each developmental stage for genes in the vicinity of stage restricted cREs (n = 1,612 for oocyte, n = 4,166 for 2-cell, n = 2,005 for 8-cell, n = 6,236 for 2/8-cell common, and n = 1,357 for mouse ES cells). Whiskers correspond to the highest and lowest points within the 1.5 × interquartile range (a, b, d). e, Accumulated fraction curve of cREs according to distance between cREs and nearest broad H3K4me3 domains. Putative cREs in the vicinity of ZGA genes are positioned closer to broad H3K4me3 domains (P < 2.2−16, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test).

Extended Data Figure 9 |. Histone H3 lysine 4 methyltransferases and demethylases in relation to establishment and removal of broad H3K4me3 domains.

a, Gene expression levels for multiple H3K4 methyltransferases and demethylases in the oocyte, 2- and 8-cell-stage embryos and mouse ES cells. b, Genome browser snapshot of the KMT2B dependent Cdkn1a gene. The Cdkn1a gene is not expressed in oocytes, but highly expressed in 2- and 8-cell-stage embryos. c, Average GC content in oocyte H3K4me3 covered regions maintained or demethylated in the 8-cell-stage embryo. Regions where H3K4me3 is specifically maintained show higher GC content (P < 2.2−16, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) d, Simple western immunoblots show Kdm5a and Kdm5b morpholino knock-down of KDM5A and KDM5B proteins in 2-cell embryos. β-actin is shown as loading control. For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1. e, Quantification of H3K4me3 immunofluorescence signal in late 2-cell stage embryos after injection with morpholinos targeting Kdm5a and Kdm5b (n = 37), or 5-base mismatch-control morpholinos (n = 23). (H3K4me3 signal intensity, arbitrary units. P = 2.2−4, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.). Error bars show the s.d.

Extended Data Figure 10 |. RNA-seq analysis of KDM5A and KDM5B depleted 2-cell embryos.

a, Scatter plots show FPKM values of GENCODE annotated genes (each dot, n = 32,287) between two biological replicates for four different conditions. Pearson correlation coefficient values are also shown. b, Box plots show the effect of α-amanitin treatment on transcriptional inhibition (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test P < 2.2−16). c, Scatter plots show FPKM values of GENCODE annotated genes (each dot, n = 32,287) between Kdm5a and Kdm5b morpholino (Kdm5a+b MO)-injected embryos (x axis) and α-amanitin-treated embryos (y axis). We present log2-transformed average FPKM values from two biological replicates. Red lines indicate twofold up- or downregulation. d, Scatter plots show FPKM values of GENCODE annotated genes between Kdm5a+b MO injected embryos (x axis) and control MO injected embryos (y axis). We present log2-transformed average FPKM values from two biological replicates. Red lines indicate 1.5-fold up- or downregulation. Grey, all genes; blue, downregulated ZGA genes. e, Box plots are shown for FPKM values of maternally expressed genes in oocyte, Kdm5a and Kdm5b morpholino replicates, and control morpholino replicates. NS indicates non-significant P value from one-sided paired t-test. In 2-cell embryos maternally expressed genes are significantly down regulated in both Kdm5a and Kdm5b morpholino and control morpholino injected embryos (P values <2.2−16, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). Whiskers correspond to the highest and lowest points within the 1.5 × interquartile range (b, e). f, Rate of development to various embryonic stages for Kdm5a and Kdm5b morpholino injected and control morpholino injected embryos resulting from natural mating (control MO, n =15; Kdm5a+b MO, n = 26). g, Number of embryos at the 8-cell and 4-cell or abnormal stage in Kdm5a+b MO (n = 46) and control MO (n = 42) (Fisher’s exact test P = 0.028, odds ratio = 3.5), for in vitro fertilized embryos for the experiment shown in Fig. 5c.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Ren laboratory for support and critical suggestions throughout the course of this work. We are thankful to L. Ellevog, G. Flor Lien, T. Catterall, S. Khan, I. Johnson, the Norwegian Transgenic Center, the Animal Facility OUS and Genoway for help with embryo collection, animal care and morpholino injections. We are grateful to A. Local for the gift of recombinant histone octameres and to R. Ahmed, M. Indahl and E. Skarpen for assistance with staining and imaging of embryos. We are also thankful to K. Shirane (Kyushu University) for sharing data. I. Jung would like to give special thanks to Y. Lee. This work was funded by the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, U54HG006997 (to B.R.), American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (to I. Jung), the Oslo University Hospital Early Career Award (to J.A.D.), the Norwegian Cancer Society (to A.K., J.A.D.), the Anders Jahre Foundation (to J.A.D.) and the Norwegian Research council (to A.K.).

Footnotes

Online Content Methods, along with any additional Extended Data display items and Source Data, are available in the online version of the paper; references unique to these sections appear only in the online paper.

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

All data from this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under the accession number GSE72784.

The authors declare competing financial interests: details are available in the online version of the paper. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of the paper.

Reviewer Information Nature thanks R. Schultz and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

References

- 1.Smith ZD et al. A unique regulatory phase of DNA methylation in the early mammalian embryo. Nature 484, 339–344 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L et al. Programming and inheritance of parental DNA methylomes in mammals. Cell 157, 979–991 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen L et al. Tet3 and DNA replication mediate demethylation of both the maternal and paternal genomes in mouse zygotes. Cell Stem Cell 15, 459–470 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo F et al. Active and passive demethylation of male and female pronuclear DNA in the mammalian zygote. Cell Stem Cell 15, 447–458 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park S-J et al. Inferring the choreography of parental genomes during fertilization from ultralarge-scale whole-transcriptome analysis. Genes Dev 27, 2736–2748 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith ZD et al. DNA methylation dynamics of the human preimplantation embryo. Nature 511, 611–615 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng Q, Ramsköld D, Reinius B & Sandberg R Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic, random monoallelic gene expression in mammalian cells. Science 343, 193–196 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xue Z et al. Genetic programs in human and mouse early embryos revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature 500, 593–597 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo H et al. The DNA methylation landscape of human early embryos. Nature 511, 606–610 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoshima K, Inoue E, Sawa H & Okada Y Paternal H3K4 methylation is required for minor zygotic gene activation and early mouse embryonic development. EMBO Rep 16, 803–812 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgan HD, Santos F, Green K, Dean W & Reik W Epigenetic reprogramming in mammals. Hum. Mol. Genet 14, R47–R58 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santos F, Peters AH, Otte AP, Reik W & Dean W Dynamic chromatin modifications characterise the first cell cycle in mouse embryos. Dev. Biol 280, 225–236 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adenot PG, Mercier Y, Renard JP & Thompson EM Differential H4 acetylation of paternal and maternal chromatin precedes DNA replication and differential transcriptional activity in pronuclei of 1-cell mouse embryos. Development 124, 4615–4625 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lara-Astiaso D et al. Immunogenetics. Chromatin state dynamics during blood formation. Science 345, 943–949 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen J et al. H3K4me3 epigenomic landscape derived from ChlP-seq of 1,000 mouse early embryonic cells. Cell Res 25, 143–147 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kues WA et al. Genome-wide expression profiling reveals distinct clusters of transcriptional regulation during bovine preimplantation development in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 19768–19773 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD & Wysocka J Methylation of lysine 4 on histone H3: intricacy of writing and reading a single epigenetic mark. Mol. Cell 25, 15–30 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bannister AJ & Kouzarides T Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res 21, 381–395 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smallwood SA et al. Single-cell genome-wide bisulfite sequencing for assessing epigenetic heterogeneity. Nat. Methods 11, 817–820 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ooi SKT et al. DNMT3L connects unmethylated lysine 4 of histone H3 to de novo methylation of DNA. Nature 448, 714–717 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otani J et al. Structural basis for recognition of H3K4 methylation status by the DNA methyltransferase 3A ATRX-DNMT3-DNMT3L domain. EMBO Rep 10, 1235–1241 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shirane K et al. Mouse oocyte methylomes at base resolution reveal genome-wide accumulation of non-CpG methylation and role of DNA methyltransferases. PLoS Genet 9, e1003439 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erkek S et al. Molecular determinants of nucleosome retention at CpG-rich sequences in mouse spermatozoa. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 20, 868–875 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creyghton MP et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 21931–21936 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nord AS et al. Rapid and pervasive changes in genome-wide enhancer usage during mammalian development. Cell 155, 1521–1531 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen Y et al. A map of the c/s-regulatory sequences in the mouse genome. Nature 488, 116–120 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Visel A et al. ChlP-seq accurately predicts tissue-specific activity of enhancers. Nature 457, 854–858 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andreu-Vieyra CV et al. MLL2 is required in oocytes for bulk histone 3 lysine 4 trimethylation and transcriptional silencing. PLoS B/ol 8, e1000453 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leung D et al. Integrative analysis of haplotype-resolved epigenomes across human tissues. Nature 518, 350–354 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benayoun BA et al. H3K4me3 breadth is linked to cell identity and transcriptional consistency. Cell 158, 673–688 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiang T & Lampson MA Counting chromosomes in intact eggs. Methods Mol. Biol 957, 249–253 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahl JA & Collas P A rapid micro chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (microChIP). Nat. Protocols 3, 1032–1045 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dahl JA & Klungland A Micro chromatin immunoprecipitation (μChIP) from early mammalian embryos. Methods Mol. Biol 1222, 227–245 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H & Durbin R Fast and accurate short read alignment with BurrowsWheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bolger AM, Lohse M & Usadel B Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krueger F & Andrews SR Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for B¡sulf¡te-Seq applications. Bioinformatics 27, 1571–1572 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trapnell C et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol 28, 511–515 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lerdrup M, Johansen JV, Agrawal-Singh S & Hansen K An interactive environment for agile analysis and visualization of ChlP-sequencing data. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 23, 349–357 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLean CY et al. GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat. Biotechnol 28, 495–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schones DE, Smith AD & Zhang MQ Statistical significance of cis-regulatory modules. BMC Bioinformatics 8, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-8-19 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heinz S et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38, 576–589 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.