Abstract

Sexual violence (SV) represents a serious public health problem, with high rates (Smith et al., 2017) and numerous health consequences. Current primary prevention strategies to reduce SV perpetration have been shown to be largely ineffective – not surprisingly, since as others have pointed out (DeGue et al., 2014) current prevention largely fails to draw on existing knowledge about the characteristics of effective prevention (Nation et al., 2003). In this paper, we examine the potential of K-12 comprehensive sexuality education (CSE), guided by the National Sexuality Education Standards (NSES), to be an effective strategy. Our discussion uses socio-ecological and feminist theories as a guide, examines the extent to which NSES-guided CSE could both meet the qualities of effective prevention programs and mitigate the risk factors that are most implicated in perpetration behavior, and considers the potential limitations of this approach. We suggest that sequential, K-12 program has potential to prevent the emergence of risk factors associated with SV perpetration by starting prevention early on in the lifecourse. CSE has not yet been evaluated with SV perpetration behavior as an outcome, and this paper synthesizes what is known about drivers of SV perpetration and the potential impacts of CSE to argue for the importance of future research in this area. The primary recommendation is for longitudinal research to examine the impact of CSE on SV perpetration as well as on other sexual and reproductive health outcomes.

Introduction

There is growing awareness in the United States about the nation’s high rates of sexual violence (SV). SV is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a sexual act committed against someone without that person’s freely given consent—including completed forced penetration (rape), attempted forced penetration, coerced penetration, unwanted sexual contact, and non-contact sexual experiences such as harassment. A 2010–2012 nationally representative survey of adults found that approximately 1 in 3 (36.3%) women and 1 in 6 (17.1%) men reported experiencing some form of sexual violence during their lifetime, with 19.1% of women and 1.5% of men experiencing completed or attempted rape, and 13.2% of women and 5.8% of men experiencing sexual coercion at some time in their lives. Among women who have been raped, 41.3% first experienced that rape before the age of 18 and an additional 36.5% were first raped between ages 18–24 (Smith et al., 2017). There is strong evidence that SV affects individuals throughout the life course (Basile, Smith, Breiding, Black, & Mahendra, 2014).

These alarming statistics underline the dire need to implement, evaluate, and scale up primary prevention – that is, effective programming to prevent SV before it happens. In a public health framework, primary prevention entails “looking upstream” at the underlying risk factors and mitigating those risk factors before they come to fruition and result in violent behavior (Harvey, Garcia-Moreno, & Butchart, 2007). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended that research and programs to prevent SV be grounded in the socio-ecological approach to prevention (Basile et al., 2016), which addresses risk factors at the individual, interpersonal, community, and social-structural levels across the lifecourse that may lead someone to perpetrate SV. This ecological approach conceptualizes violence as an interplay among these multiple levels of influence (Casey & Lindhorst, 2009; Heise, 1998; Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, & Lozano, 2002).

Drawing on that ecological lifecourse perspective, this paper examines one promising strategy for the primary prevention of sexual violence perpetration that would operate by modifying the known risk factors associated with perpetration. A primary prevention of perpetration approach, instead of a focus on the risk factors that make someone likely to be victimized, places the onus for SV prevention on perpetrators. While victimization prevention approaches should be part of a larger sexual violence prevention strategy, the historical emphasis on preventing victimization neglects the role of the perpetrator in violence; this can fuel victim-blaming narratives, self-blame, and a focus on whether victims could have done something differently to prevent an attack (DeGue et al., 2012). Furthermore, a prevention focus on those at risk for being assaulted does not necessarily reduce attempts to perpetrate sexual violence nor does it address the social norms that lie on the outer level of the ecological model that allows sexual violence to continue. In order to achieve measurable reductions in violence, perpetration needs to be the focal point of intervention (DeGue et al., 2012).

There are few programs with demonstrated effectiveness at mitigating perpetration behavior (DeGue et al., 2014). A 2014 review found only three programs shown by rigorous, controlled evaluation to prevent perpetration behavior (DeGue et al., 2014). Furthermore, it found that the vast majority of programs target college-level students, but that none of the effective programs were in this age group. Instead, program effectiveness was found earlier on in the life course, during adolescence (DeGue et al., 2014). Given the substantial limitations of the literature on effective perpetration prevention, the current paper draws on Banyard’s 2013 commentary encouraging sexual violence researchers to “locate and use opportunities for bridging across areas of prevention … and across the life span (e.g., finding ways to connect skill building in childhood and adolescence with prevention education in early adulthood)” (Banyard, 2013, p. 115).

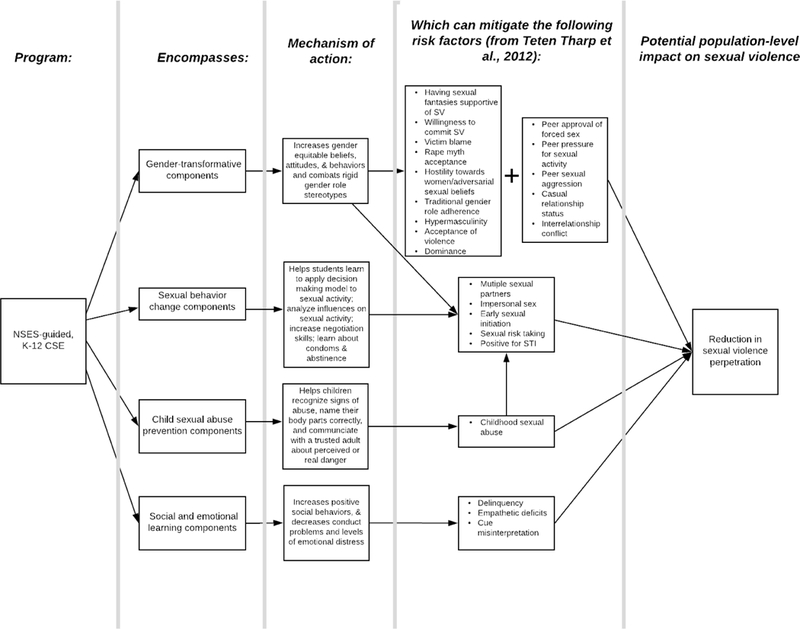

The specific step this paper takes to advance SV prevention is to examine the potential for K-12 comprehensive sex education (CSE), guided by the National Sexuality Education Standards (NSES)—and henceforth referred to as NSES-CSE—to effectively prevent perpetration behavior. Currently, most school-based SV programs are independent from any CSE program, and many CSE programs fall short of their potential to comprehensively address SV perpetration. An NSES-CSE program can effectively merge the two and address SV while simultaneously fulfilling its more traditional goals of preventing unplanned teen pregnancy, HIV/STI acquisition, and other adverse health outcomes. There are several reasons for this, all of which are discussed at greater length below, but in brief: (1) research across multiple areas of behavioral prevention highlights a number of criteria for effectiveness, all of which can be met by high-quality NSES-CSE; (2) a number of well-documented risk factors for SV perpetration are addressed in a NSES-CSE curriculum; (3) these risk factors have individually been shown to be amenable via small group or educational interventions, and sex education creates an opportunity to comprehensively address many of them in one intervention; and (4) a sequential, K-12 program begins early on in the life course when many risk factors are only just beginning to develop, and by reaching young children while they are still in development, it presents the best opportunity to address the problem before it occurs. The field of SV prevention is in desperate need of population-level solutions. The interventions currently being implemented in the field primarily target an age group in which intervention is past the point of being “primary” prevention. NSES-CSE may present one promising strategy to address this critical public health issue. Figure 1 visually depicts the mechanism through which NSES-CSE could be effective.

Figure 1:

Conceptual model of pathways through which Comprehensive Sexuality Education based on National Sexuality Education Standards (NSES-CSE) could prevent sexual violence perpetration

Methods

Because, as noted above, there is so little in the way of published literature on effective primary prevention for SV, we did not take a systematic literature review approach. Rather, cued by Banyard (2013) to mine other areas in which successful and relevant prevention programs have been developed, our literature search, conducted on EBSCOHost using all databases, sought relevant literature for each section in this paper. We first searched for current SV primary prevention literature to understand the current state of the field. We then searched for an existing systematic review of risk factors for SV perpetration. We clustered the risk factors found in this review into themes (see Figure 1) and conducted a search for all clusters to find existing reviews of each.

Because this article is not intended to be a systematic review, not every article yielded in the search is included. This article synthesizes evidence from review articles in several different areas to examine the potential of CSE as an effective population-level strategy for the prevention of SV perpetration. Search terms used for these different research areas are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1:

Search terms and key articles used

| Section of paper | Key review article used in section | Search terms used |

|---|---|---|

| Gaps in current primary prevention of SV | DeGue, S., Valle, L. A., Holt, M. K., Massetti, G. M., Matjasko, J. L., & Tharp, A. T. (2014). A systematic review of primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration. Aggression and Violent Behavior,19(4), 346–362. | • Systematic review OR meta-analysis |

| • Sexual violence | ||

| • Primary prevention | ||

| Risk factors for SV perpetration | Tharp, A. T., DeGue, S., Valle, L. A., Brookmeyer, K. A., Massetti, G. M., & Matjasko, J. L. (2012). A Systematic Qualitative Review of Risk and Protective Factors for Sexual Violence Perpetration. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse,14(2), 133–167. | • Systematic review OR meta-analysis |

| • Sexual violence | ||

| • Risk factors | ||

| • Perpetration | ||

| Interventions to address sex, gender, and violence related risk factors | Dworkin, S. L., Treves-Kagan, S., & Lippman, S. A. (2013). Gender-Transformative Interventions to Reduce HIV Risks and Violence with Heterosexually-Active Men: A Review of the Global Evidence. AIDS and Behavior,17(9), 2845–2863. | • Systematic review OR meta-analysis |

| • Education OR program OR intervention | ||

| • Gender-transformative | ||

| • Violence OR rape OR sexual assault | ||

| Interventions to address child abuse related risk factors | Walsh, K., Zwi, K., Woolfenden, S., & Shlonsky, A. (2015). School-based education programmes for the prevention of child sexual abuse (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4), CD004380. | • Systematic review OR meta-analysis |

| • Education OR program OR intervention | ||

| • Child sexual abuse | ||

| • Prevention | ||

| Interventions to address sexual behavior related risk factors | Chin, H.B., Sipe, T.A., Elder, R., Mercer, S.L., Chattopadhyay, S.K…Santelli, J. (2012). The effectiveness of group-based comprehensive risk-reduction and abstinence education interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus, and sexually transmitted infections: Two systematic reviews for the guide to community preventive services. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(3), 272–294. | • Systematic review OR meta-analysis |

| • Education | ||

| • Sexuality OR sexual OR sex | ||

| • Comprehensive | ||

| Haberland, N. (2015a). Sexuality education: Emerging trends in evidence and practice. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(1), S15-S21. | ||

| Interventions to address social and emotional learning based risk factors | Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Child Development,82(1), 405–432. | • Systematic review OR meta-analysis |

| • Education OR program OR intervention | ||

| • Social and emotional learning | ||

Sexual Violence as a Public Health Problem

Preventing SV is an important public health priority for a multitude of reasons. In addition to the obvious human rights violations described by the statistics above, experiencing SV also has both immediate and long-term health consequences. Physical consequences include pregnancy (over 32,000 of which occur every year as a result of rape) as well as STI/HIV acquisition, chronic pain, gastrointestinal disorders, gynecological complications, migraines, cervical cancer, and genital injuries (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Immediate psychological consequences of SV include shock, denial, fear, confusion, anxiety, withdrawal, guilt, shame, distrust of others, and post-traumatic stress disorder, and longer-term psychological consequences include depression, generalized anxiety, attempted or completed suicide, diminished interest or avoidance of sex, and low self-esteem (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017).

Research also shows a variety of subsequent health risk behaviors associated with having experienced SV, including earlier sexual debut, unprotected sex, having multiple sexual partners, cigarette use, drunk driving, and illicit drug use. These behaviors put victims at risk of unplanned pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, HIV, and cigarette, drug, and alcohol related injuries and illnesses (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Furthermore, the estimated lifetime cost of rape is $122,461 for the victim, with a population economic burden of $3.1 trillion over the victims’ lifetimes. These cost estimates include medical costs (39%), lost work productivity (52%), criminal justice related activities (8%), among other costs such as property loss and damage (1%) (Peterson, DeGue, Florence, & Lokey, 2017).

The Current State of the Sexual Violence Field

The state of the SV field is not adequate to successfully prevent perpetration. Instead, the field features a plethora of different programs, including one-off, on-line sessions intended to prevent perpetration and promote bystander behavior (DeGue et al., 2014) or secondary and tertiary prevention programs that work with survivors of violence to prevent re-victimization and help the criminal justice system successfully prosecute perpetrators (The White House Council on Women and Girls, 2014). For example, The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), which is the backbone of the nation’s sexual violence response (The White House Council on Women and Girls, 2014) and which was reauthorized in 2013 through Fiscal Year 2018 (Sacco, 2015), funds 28 grant programs, the vast majority of which are geared towards victim services and enhancing the criminal justice response to violence (Sacco, 2015). This re-authorization brought with it set-aside funding and new purpose areas for multidisciplinary sexual assault response teams, sexual assault nurse examiners, specialized law enforcement units, and training for criminal justice professionals (The White House Council on Women and Girls, 2014). It also includes new provisions to help previously overlooked survivors of SV, including immigrants and the LGBTQ community. The 2013 reauthorization doubled funding for the Sexual Assault Service Formula Grant Program, which exclusively funds initiatives that help survivors on various steps in their road to recovery (The White House Council on Women and Girls, 2014). Unquestionably these are all crucial aspects of a comprehensive approach to violence, yet these programs reflect a predominant focus on care and response, rather than on primary prevention.

DeGue et al. (2014) conducted a systematic review of 140 outcome evaluations to describe the current primary prevention interventions being employed in the field and to assess the effectiveness of these programs for SV perpetration. Two-thirds of the studies they reviewed consisted of brief, one-session interventions with college populations (n=84). Only 11 of those measured sexually violent behavioral outcomes, none of which were found to consistently affect those behaviors. Rather, the majority of these intervention evaluations measured knowledge or attitudinal change as program outcomes; these are certainly related to behavior but are not necessarily sufficient to change behavior and may not be sustained over time. The review found only three primary prevention strategies in total for which there was sufficient evidence that they reduced sexual violence perpetration behavior in a rigorous outcome evaluation, two of which were implemented among adolescent populations and one based on funding associated with the 1994 U.S. Violence Against Women Act (VAWA). Their review makes clear that the vast majority of efforts being made to curb perpetration are being implemented among college groups, and that none of these interventions have been found to be effective; together these two conclusions suggest that a paradigm shift is warranted to focus on younger groups and to emphasize primary prevention. The recent finding from a population-based survey of undergraduates in one campus context that more than one-quarter of women and nearly one-tenth of the men surveyed had experienced some form of pre-matriculation sexual assault (Mellins et al., 2017, p. 12) only underlines the importance of targeting primary prevention efforts at pre-college students.

Moving Towards Effectiveness: Prevention Science

The field of prevention science has identified nine characteristics of effective prevention: (1) comprehensiveness; (2) varied teaching methods; (3) sufficient dosage; (4) theory driven; (5) fosters positive relationships; (6) appropriately timed; (7) sociocultural relevance; (8) well-trained staff; and (9) outcome evaluations (Nation et al., 2003). DeGue et al. (2014) analyzed whether and to what extent the programs in their review met these criteria—and they by and large did not, which indicates why they may have collectively been so unsuccessful at reducing SV perpetration. Table 2 provides further detail about the ways in which the 140 outcome evaluations reviewed by DeGue et al. failed to meet the qualities of effective prevention. Table 2 also shows by comparison how a program that adheres to the National Sexuality Education Standards—which serves as the foundation for this paper’s argument on best-practices CSE— fulfills many of these same characteristics of effective prevention.

Table 2:

Qualities of Effective Prevention: Comparison of studies reviewed in DeGue et al. and of the National Sexuality Education Standards (NSES)

| Commonalities of effective prevention programs (Nation et al., 2003) | Did programs reviewed by DeGue meet these qualities? Source: DeGue, S., Valle, L. A., Holt, M. K., Massetti, G. M., Matjasko, J. L., & Tharp, A. T. (2014). A systematic review of primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration. Aggression and Violent Behavior,19(4), 346–362. |

Can programs that follow the NSES meet these qualities? Source: Future of Sex Education Initiative. (2016). Building a Foundation for Sexual Health Is a K–12 Endeavor: Evidence Underpinning the National Sexuality Education Standards. Retrieved from http://futureofsexed.org/documents/Building-a-foundation-for-Sexual-Health.pdf |

| 1. Compre-hensive | No: The vast majority of studies “utilized a narrow set of strategies to address individual attitudes and knowledge related to SV. Fewer than 10% included content to address factors beyond the individual level, such as peer attitudes, social norms, or organizational climate and policies” (p. 356). | Yes: Don’t focus solely on sexual violence. Rather, it teaches about positive sexual health in its entirety. This means that the entire spectrum of sexual health would be covered in an age appropriate manner. 7 key topic areas are included: Anatomy and Physiology; Puberty and Adolescent Development; Identity; Pregnancy and Reproduction; Sexually Transmitted Diseases and HIV; Healthy Relationships, and Personal Safety. |

| 2. Varied teaching methods | No: “Nearly 1/3 of interventions utilized a single mode of intervention delivery (or teaching method) and another 40% utilized two modes of instruction. The most common modes of intervention delivery involved interactive presentations, didactic-only lectures, and/or videos. Only about 1/3 involved active participation in the form of role-playing, skills practice, or other group activities” (p. 357). | Implied: States that “students need opportunities to engage in cooperative and active learning strategies.” |

| 3. Sufficient dosage | No: 75% of interventions “had only 1 session, and half of all studies involved a total exposure of 1 h or less. It is likely that behaviors as complex as SVP will require a higher dosage to change behavior and have lasting effects” (p. 357) | Implied: Don’t recommend a specific amount of time to be allotted to each topic, but do state that sufficient time should be given for students to master the topics and skills delineated in the curriculum. Furthermore, it spans K-12, implying that sufficient dosage will be given. |

| 4. Theory driven | No: DeGue et al. did not “systematically evaluate the theoretical underpinnings of the interventions…[However], the most common risk factors addressed were knowledge and attitudes about rape, women, and sex. There is limited empirical evidence linking legal or sexual knowledge to sexual violence perpetration and virtually no theoretical reason to believe that rape is caused by lack of awareness and laws prohibiting it” (p. 357). | Yes: Reflects the social learning theory, social cognitive theory, and the social ecological model. |

| 5. Positive relationships | No: “The short length and didactic nature of most interventions reviewed here do not lend themselves well to relationship-building” (p. 357). | Yes: Of the 7 key topics covered, “Healthy Relationships” is an entire topic area. |

| 6. Appropriate timing | No: “More than 2/3 of sexual violence prevention strategies…targeted college samples…However, because many college men have already engaged in sexual violence before arriving on campus or will shortly thereafter, prevention initiatives that address this age group may miss the window of opportunity to prevent SV before it starts” (p. 356). | Yes: The curriculum starts in Kindergarten and lasts through the end of high school, ensuring that developmentally appropriate health objectives are met in each grade. |

| 7. Socio-culturally relevant | No: Only three interventions included content designed for specific racial/ethnic groups. 14 studies evaluated programs for fraternity men, male athletes, and the military. Two-thirds of programs were implemented with majority-white samples (p.357). | Yes: States that sexuality education should “focus on health within the context of the world in which students live.” |

| 8. Outcome evaluations | Mixed: Most outcome evaluations did not include follow-up past 5 months and only 21 studies measured sexually violent behavior as an outcome. | Not Stated: In order to understand if a curriculum built in the NSES works in changing perpetration behavior, it is important to conduct an outcome evaluation. Part of our argument in this paper is that when an NSES-guided CSE curriculum is implemented, it should be evaluated with sexually violent behavior as an outcome. |

| 9. Well trained staff | No: “Only one-quarter of interventions were implemented by professionals with expertise related to sexual violence prevention and extensive knowledge of the program model. The majority of programs were implemented by peer facilitators, advanced students, or school/agency staff who may not have specific expertise in the topic” (p.357). | Yes: Part of the recommendations include pre-service teacher training, professional development, and ongoing support and mentoring for teachers to ensure that the staff delivering CSE are well trained. |

Experts in the field of sex education created the NSES in 2012 to serve as a guideline for the base minimum that all sex education programs should follow (Future of Sex Ed Initiative, 2012). The Standards’ aim is to “provide clear, consistent and straightforward guidance on the essential minimum, core content for sexuality education that is developmentally and age-appropriate for students in grades K–12” (Future of Sex Ed Initiative, 2012). The NSES were informed by the National Health Education Standards (Joint Committee on National Health Education Standards, 2007); the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007); existing state and international education standards that include sexual health content (Future of Sex Ed, 2012); and the Guidelines for Comprehensive Sexuality Education: Kindergarten – 12th Grade (Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States, 2004).

An NSES-guided CSE program meets the qualities of effective prevention in multiple ways. As the name implies, the standards are comprehensive, spanning a wide range of topics related to sexuality, sexual health, and overall well-being: anatomy and physiology; puberty and adolescent development; identity; pregnancy and reproduction; sexually transmitted diseases and HIV; healthy relationships; and personal safety (Future of Sex Ed Initiative, 2012). The standards are theory-driven, drawing on social learning theory, social cognitive theory, and the social ecological model (Future of Sex Ed Initiative, 2016). Positive relationships are stressed as a key component of the standards. They emphasize age-appropriateness of the topics covered, spanning kindergarten through 12th grade, with different learning objectives in each grade level, thereby ensuring that students are reached before the onset of any risk behaviors and at a developmental moment where the information provided is relevant and appropriate. The standards recommend pre-service teacher training, professional development, and ongoing support and mentoring to ensure that staff are well trained (Future of Sex Ed Initiative, 2016). The standards also recommend the use of varied teaching methods. Lastly, the Standards cover multiple topics, and thus intrinsically require a much higher ‘dosage’ than the typical SV prevention program, with the NSES outline of the entire curriculum spanning K-12 with a multitude of learning objectives and topics to be included (Future of Sex Ed Initiative, 2012). Table 2 maps out the NSES with the qualities of effective prevention in more detail.

Risk Factors for Sexual Violence Perpetration

The fact that an NSES-guided curriculum meets the qualities of effective prevention in general, however, is only one piece of conceptualizing why it makes sense to explore it as a strategy for primary prevention of sexual violence. Indeed, sex education traditionally aims to prevent health outcomes such as unplanned teenage pregnancy and HIV/STI acquisition, not sexual violence (Chin et al., 2012; Haberland, 2015a; Kirby, Laris, & Rolleri, 2007; Lindberg & Maddow-Zimmet, 2012). The authors were not able to identify any published work to date evaluating the impact of sexuality education on sexual violence behavior as a dependent variable. Healthy relationships are a component of sexuality education curricula that meet NSES standards, and yet the impact on unhealthy relationship behaviors such as sexual violence or teen dating violence have not been evaluated as outcome measures, or at least not evaluated in a way that has been disseminated through the searchable peer-reviewed scientific literature. The goal of this paper is to map out conceptually the potential of CSE, in order to encourage research that examines the hypothesis that sex education could be effective prevention for sexual violence perpetration behavior in addition to the more traditional health outcomes, and thus that it should be evaluated as a dependent variable of an NSES-guided K-12 CSE program. The other crucial elements in proposing evaluation of the impact of best-practices CSE on SV are 1) to examine whether known risk factors for SV perpetration have been shown to be amenable to modification through educational intervention in the past and 2) to assess the extent to which these risk factors would be addressed through NSES-CSE.

Teten Tharp et al.’s (2012) systematic review of risk and protective factors for SV perpetration summarized 191 published empirical studies that examined perpetration by and against adolescents and adults. Two societal and community factors, 23 relationship factors, and 42 individual level factors were identified (n=67). Out of these 67 factors, 35 of them displayed consistently significant association with SV. All 35 of these factors, which were at the individual, interpersonal, or relationship level of the social-ecological model, are presented in Table 3. That these factors exist across multiple levels of the ecological model underlines the need for a prevention approach that works across the models’ different levels. (Some of those risk factors, such as previous suicide attempt, sports and fraternity participation, or having experienced physical or emotional abuse as a child, fall substantively outside of the goals of NSES-CSE, underlining that even if it is found to be effective at reducing sexual violence by addressing some of the underlying risk factors, a truly comprehensive approach will be comprised of layered strategies across the ecological level over multiple points in the life course.) The risk factors can be grouped into four overarching categories: sex, gender, and violence-related risk factors, child abuse-related risk factors, sexual-behavior-related risk factors, and social and emotional intelligence-related risk factors.

Table 3:

Sexual violence perpetration risk factors found to be significant (Adapted from Teten Tharp et al. (2012)) and potential for CSE to mitigate those risk factors

| Category | Level of the ecological model |

Risk Factor | # of studies finding significance |

Component of NSES-CSE likely to mitigate risk factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, gender, and violence based risk factors | Individual | Having sexual fantasies supportive of SV | 4/7 studies | Gender-transformative programming |

| Willingness to commit SV | 7/11 studies | |||

| Victim blame | 4/4 studies | |||

| Rape myth acceptance | 31/36 studies | |||

| Hostility towards women/adversarial sexual beliefs | 32/42 studies | |||

| Traditional gender role adherence | 19/21 studies | |||

| Hypermasculinity | 12/18 studies | |||

| Acceptance of violence | 9/13 studies | |||

| Dominance | 4/6 studies | |||

| Competitiveness | 1/1 study | |||

| Relationship- romantic | Casual relationship status | 2/2 studies | ||

| Interrelationship conflict | 7/8 studies | |||

| Relationship- peers | Peer approval of forced sex | 4/4 studies | ||

| Peer pressure for sexual activity | 6/7 studies | |||

| Peer sexual aggression | 3/3 studies | |||

| Membership in fraternity* | 8/11 studies | |||

| Sports participation* | 8/12 studies | |||

| Child abuse based risk factors | Relationship- family | Previous childhood sexual abuse | 20/34 studies | Childhood sexual abuse prevention programming |

| Previous childhood physical abuse* | 15/21 studies | |||

| Previous childhood emotional abuse* | 4/5 studies | |||

| Exposure to parental violence/family conflict* | 18/22 studies | |||

| Sexual behavior based risk factors | Individual | Multiple sexual partners | 21/25 studies | Traditional aim of sex education is to reduce these factors, so they are likely to be reduced by NSES-CSE. Gender transformative programming and CSA prevention programming also likely to affect these factors. |

| Impersonal sex | 12/13 studies | |||

| Early initiation of sex | 7/7 studies | |||

| Sexual risk taking | 4/5 studies | |||

| Positive for STI | 3/3 studies | |||

| Exposure to sexually explicit media* | 6/9 studies | |||

| Motivation for sex/sex drive** | 4/5 studies | |||

| SV victimization during adolescence or adulthood+ | 2/3 studies | |||

| Past SV perpetration+ | 9/9 studies | |||

| Social and emotional learning based risk factors | Individual- psychosocial | Delinquency | 16/24 studies | Social-emotional learning programming |

| Previous suicide attempt* | 3/4 studies | |||

| Interpersonal | Empathetic deficits | 13/20 studies | Social-emotional learning programming | |

| Cue misinterpretation | 6/7 studies | |||

| Relationship-peers | Gang membership | 2/2 studies |

These risk factors are not likely to be successfully addressed in comprehensive sex education programs, either because they fall out of the purview of a CSE curriculum or because they occur primarily inside the home and out of the reach of CSE. This underlines the need for a multifaceted strategy to address perpetration.

Interest in and desire for sex is a normal part of adolescent development. Therefore, not relevant to SV perpetration prevention.

This paper focuses on CSE as a primary prevention strategy for SV perpetration. Therefore, discussion of previous victimization and perpetration recidivism are not discussed.

Sex, Gender, and Violence

The largest category of risk factors found to be significant in Teten Tharp et al.’s (2012) review fall under sex, gender, and violence (Table 3). At the individual level, these include: having sexual fantasies supportive of SV; willingness to commit SV; engaging in victim blaming; rape myth acceptance; hostility towards women/adversarial sexual beliefs; traditional gender role adherence; hypermasculinity; acceptance of violence; dominance; and competitiveness. At the peer-relationship level, these include: peer approval of forced sex; peer pressure for sexual activity; peer sexual aggression; membership in a fraternity; and sports participation. At the romantic-relationship level, these include: having a casual relationship status and having interrelationship conflict. These risk factors are fundamentally tied to gender and sexual norms and cognitions (Casey & Lindhorst, 2009; Heise, 1998).

Teten Tharp’s review failed to find the structural-level risk factor of gender as significant for SV perpetration, despite the intrinsic relationship between the broader social organization of gender and these relationship and individual-level manifestations of gendered practices and beliefs. This failure to find empirical evidence for the structural concept of gender as a risk factor may reflect the review’s exclusion of qualitative and ethnographic research and their focus on biomedical rather than social scientific research. Ethnographic and qualitative empirical work (e.g., Armstrong, Hamilton, & Sweeney, 2006; Sanday 1981, 1996) grounded in social scientific theory certainly demonstrates that the social organization of gendered power is a critical underlying social driver of the sexual assault of women, as does both foundational work in gender theory (Connell, 1987) and quantitative social scientific research that looks comparatively at social organization and gender power (Whaley, 2001). An extensive discussion of the range of research not included in the Teten Tharp et al. (2012) is beyond the scope of this article, but because our argument for NSES-CSE as a strategy to prevent sexual violence relies on the ecological model, this question about the role of broader community and social norms is critical because of their framing, in the ecological model, as shaping factors at the individual, family, peer, and relationship levels (Casey & Lindhorst, 2009; Fulu et al., 2013; Heise, 1998; Jewkes, Flood, & Lang, 2015). An understanding of inequitable gender relations as a foundational structural driver of sexual violence is thus necessary in any discussion of SV perpetration prevention (Fulu et al., 2013; Jewkes, Flood, & Lang, 2015).

There is without question evidence from other sources that unequal gendered access to power is an underlying cause of sexual violence (Breger, 2014; Casey & Lindhorst, 2009; Courtenay, 2000; Fulu et al., 2013; Heise, 1998; Jewkes, Flood, & Lang, 2015; Kagesten, 2016). These manifestations include many of the risk factors identified in this review clustered within the sex, gender, and violence risk factors category. Feminist theory offers at least two ways of thinking about the social processes through which gender, masculinity, and violence are related (Anderson, 2005). The first is that violence is a mechanism through which men can prove their masculinity, and thus performing acts of violence causes or leads to a societally accepted depiction of masculinity (Anderson, 2005). The second is that gender is a social structure which influences opportunities and rewards for violent behavior. Men who fit the acceptable ideal of masculinity—or hegemonic masculinity—are rewarded for their behavior by maintaining power and control within society (Anderson, 2005). Hegemonic masculinity in much of the world, and especially in the United States, encompasses heterosexual success, dominance and control over women, sexual entitlement, and strength and toughness (Jewkes, Flood, & Lang, 2015). When combined in a society that allows men to perpetrate with fairly little consequences, these qualities can contribute to a dangerous formula for sexual violence perpetration.

The ecological model is conceptualized as embedded levels of causality (Heise, 1998), and thus shifting the societal, inequitable gender norms that sit in the outer level of the model will in turn affect relationship, peer, and individual gendered relations, cognitions, and behaviors. “Gender-transformative” interventions are defined as those that aim to “reconfigure gender roles in the direction of more gender equitable relationships” (Dworkin, Treves-Kagan, & Lippman, 2013, p. 2846). Furthermore, they “view masculinities as a set of social norms that are modifiable in order to attain reduced rates of violence, decreased levels of unsafe sex, and improvements in inequitable gender relations” (p. 2846) These interventions acknowledge gender as the central component in the perpetration of SV, and thus place it at the epicenter of the theory of change.

Based on this definition, NSES-CSE would be defined as gender-transformative (Table 4). A mere glance at the standards delineate this clearly: by the end of 2nd grade, programs provide children with the critical thinking capacity to discuss the similarities and differences in how boys and girls may be expected to act; provide examples of how friends, family, media, and culture can influence the ways girls and boys think they should act; and learn about gender and gender roles. By the end of 5th grade students can define sexual orientation and demonstrate ways to show respect and treat others with dignity. By the end of 8th grade, students explore gender expression and analyze the potential impact of individual, family, and cultural expectations on gender, gender roles, and gender stereotypes; they begin to analyze the impact of gender inequities on relationships, including on power dynamics, communication, and decision-making; they can differentiate between sexual orientation and gender identity; and they can demonstrate respectful communication with people of all gender identities, gender expressions, and sexual orientations (Future of Sex Ed Initiative, 2012).

Table 4:

How NSES-CSE addresses the majority of risk factors for SV perpetration

| Selected risk factors for perpetration, grouped by category, that could be mitigated by NSES-CSE | Examples of how NSES-CSE addresses selected risk factors in this category |

| Gender, sex, violence | By the end of 2nd grade, children discuss the similarities and differences in how boys and girls may be expected to act; provide examples of how friends, family, media, and culture can influence the ways girls and boys think they should act; and learn about gender and gender roles. |

| • Having sexual fantasies supportive of SV | |

| • Willingness to commit SV | |

| • Victim blame | |

| • Rape myth acceptance | By the end of 5th grade students can define sexual orientation; demonstrate ways to show respect and treat others with dignity; and compare the positive and negative ways friends and peers can influence relationships. |

| • Hostility towards women/adversarial sexual beliefs | |

| • Traditional gender role adherence | By the end of 8th grade, students explore gender expression and analyze the potential impact of individual, family, and cultural expectations on gender, gender roles, and gender stereotypes; they begin to analyze the impact of gender inequities on relationships, including on power dynamics, communication, and decision-making; they can differentiate between sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression; and they can demonstrate respectful communication with people of all gender identities, gender expressions, and sexual orientations |

| • Hypermasculinity | |

| • Acceptance of violence | |

| • Dominance | |

| • Competitiveness | |

| • Peer approval of forced sex | |

| • Peer pressure for sexual activity | |

| • Peer sexual aggression | |

| • Casual relationship status | |

| • Interrelationship conflict | |

| Child sexual abuse | By the end of 2nd grade, children learn the correct names of their body parts and that they have the right to tell others not to touch their bodies when they do not want to be touched; students identify a parent or other trusted adults in whom they can confide if they are feeling uncomfortable about being touched; and they practice how to respond if someone touches them in a way that makes them uncomfortable. |

| • Previous childhood sexual abuse | |

|

Sexual behavior • Multiple sexual partners • Impersonal sex • Early initiation of sex • Sexual risk taking • Being positive for an STI |

By implementing the gender transformative components and child sexual abuse components above, there may be effects on sexual behavior based risk factors. Sex education programs that address gender and power are markedly more successful at results on pregnancy and STI reduction than programs that don’t. |

| Furthermore, in the NSES, young people learn about the health benefits of condoms and contraception. By the end of 8th grade, students learn: the meaning of sexual abstinence and delay, how to apply a decision making model to help them examine the benefits of delaying sexual initiation, to apply their communication and decision-making skills to sexual situations, and to assess the health benefits, risks and effectiveness rates of various methods of contraception. | |

| By the end of 12th grade, students analyze influences that impact people’s decisions regarding sexual activity, and demonstrate ways to show respect for the personal boundaries of others. | |

|

Social-emotional intelligence • Delinquency • Empathetic deficits • Cue misinterpretation • Gang membership |

By the end of 2nd grade, students should be able to identify healthy ways to express feelings, show respect, and control their behaviors. |

| By the end of 5th grade, students practice recognizing and managing their emotions, learn healthy ways to communicate differences of opinions, explore the differences between healthy and unhealthy relationships, and practice skills necessary to treat themselves and others with dignity and respect. | |

| By the end of 8th grade, students learn to communicate respectfully, negotiate conflict fairly, apply effective decision-making strategies, and demonstrate ways to show empathy and treat each other with dignity and respect. | |

To examine what is known about whether effective interventions exist to transform gender norms, Dworkin, Treves-Kagan, and Lippman (2013) conducted a systematic review of gender-transformative programming in relation to HIV. The review included 15 research articles. To be included, articles had to measure either a reduction in HIV/STI incidence; sexual risk behaviors; violence against women; or normative change in attitudes as outcomes. Of the 15 studies included, 9 evaluated a change in gender norms through small group educational interventions with adolescents and young adults. There was a high degree of variability in indicators measuring a change in gender norms, including: attitudes about gender and masculinity; discussing sex, HIV prevention, condom use, and HIV testing with a main or casual partner; recognition of abuse; and acceptance of violence towards women. Eight of these showed statistically significant results on at least one indicator of gender norms. This review delineates that gender-transformative interventions employed in small group educational settings can be successful at changing gender norms with adolescents and young adults, indicating that NSES-CSE could also successfully change gender norms, leading to a potential reduction in SV perpetration through mitigation of this risk factor. Furthermore, comprehensive sex education programs that address gender and power have had markedly better results on pregnancy and STI reduction than sex education programs that fail to do so (Haberland, 2015b). Different types of sexual and reproductive health programs, such as reproductive health interventions for married girls, men in maternity projects, and microcredit programs for marginalized women, have also found that programs that address gender and power yields much more significant results than programs that don’t, indicating that gender is a core component of sexual and reproductive health generally (Haberland, 2015b). As sexual violence is a component of sexual and reproductive health, this is likely to hold true in the SV prevention arena as well.

Child Abuse

The prevention of child abuse – which includes not just sexual abuse but also physical abuse more broadly as well as emotional abuse – is important for several reasons, the foremost being to stop the current abuse being faced by the child. Secondarily, child abuse prevention may halt the cycle of abuse that occurs when people who have been formerly abused become perpetrators as adults. Child abuse and witnessing family violence are both risk factors for perpetration later in life (Teten Tharp et al., 2012). Abuse can leave emotional, psychological, and developmental scars and children who are exposed to abuse in early childhood can become prone to aggression, impulsivity, and an absence of empathy or remorse (Heise, 1998; Jewkes, Flood, & Lang, 2015). Furthermore, Social Learning Theory adds that children may learn that violence can be used as a mechanism to get one’s way and adopt this behavior as an adult (Heise, 1998).

Both conceptual and empirical work suggests that NSES-CSE can help prevent child sexual abuse (CSA). Research shows that “the ability of a child to prevent or report child abuse is dependent, in part, on their understanding of their bodies, including the correct names of body parts, the recognition that they have bodily autonomy, and the skills to communicate with a caring adult regarding perceived or real danger” (Future of Sex Ed Initiative, 2016). The American Academy of Pediatrics (2011) recommends that children learn the names of genitals along with other body parts to understand that “the genitals, while private, are not so private that you can’t talk about them.” In the NSES (Table 4), by the end of 2nd grade, children learn the correct names of their body parts and that they have the right to tell others not to touch their bodies when they do not want to be touched; students identify a parent or other trusted adults in whom they can confide if they are feeling uncomfortable about being touched; and they practice how to respond if someone touches them in a way that makes them uncomfortable (Future of Sex Ed Initiative, 2012).

A recent systematic review (Walsh, Zwi, Woolfenden, & Shlonsky, 2015) compiled evidence of the effectiveness of a school-based program to prevent CSA. The review included 24 studies, with ten aimed at younger participants from kindergarten through third grade; eight aimed at 4th grade and older; and six studies had both younger and older participants. Programs ranged from a single 45-minute session to eight 20-minute sessions on consecutive days. This review was conducted to assess whether programs are effective in improving students’ protective behaviors and knowledge about sexual abuse prevention; if behaviors and skills are retained over time; and whether participation results in disclosures of sexual abuse, produces harms, or both. Protective behaviors were enhanced at immediate post-test; the intervention group had gains in factual and applied knowledge up to 2 weeks post-intervention with studies having a 1–6 month follow-up showing maintenance of knowledge; and odds of disclosure were as much as 3.5 times higher in the intervention participants.

These results suggest that schools can be an effective vehicle for CSA prevention and intervention, as well as underlining the need for complementary strategies that focus on the prevention of emotional and physical abuse. The studies included in the review all had the primary goal of reducing CSA, and were not significantly long in duration or fully comprehensive. Including CSA prevention within a larger CSE framework, as is done in the NSES, may produce better results because it would feature the qualities of effective prevention described at length above. Furthermore, it is important to note that education tailored to the child should be part of a larger strategy to prevent CSA and the onus of prevention should not be placed on the child. However, being able to recognize signs of abuse, name body parts, develop bodily autonomy, and tell a trusted adult can help a child get out of a sexually abusive situation.

Sexual Behavior

Teten Tharp et al. (2012) identify a number of sexual behavior-related factors that consistently demonstrate a strong association with perpetrating sexual violence: having multiple sexual partners; impersonal sex; early initiation of sex; sexual risk taking; and being positive for an STI. One factor that the literature has attributed this association to is that enacting these behaviors are mechanisms to negotiate power, demonstrate masculinity, and display an emphasized heterosexuality (Courtenay, 2000; Grazian, 2007; Jewkes, 2012; O’Sullivan, Hoffman, Harrison, & Dolezal, 2006; Ott, 2010; Pleck, Sonenstein, & Ku, 1993; Santana, Raj, Decker, Marche, & Silverman, 2006; Shearer, Hosterman, Gillen, & Lefkowitz, 2005), all of which fall under the domain of gender inequity across the social ecology and have already been discussed as risk factors for sexual violence perpetration above. Another factor that can help to explain this association is that early (consensual) initiation of sexual activity and increased high-risk sexual behaviors are associated with childhood sexual abuse (Jewkes, 2012), which has also already been discussed as a major risk factor in perpetration. Proposed pathways from childhood sexual abuse to high risk sexual activity include the development of: maladaptive sexual scripts; avoidant coping mechanisms such as alcohol and drug use which could lead to sexual risk behavior; difficulties with attachment and trust which can lead to a series of short or concurrent sexual relationships; and self-efficacy issues that inhibit formerly abused individuals from being able to control sexual situations as adolescents (Senn, Carey, & Vanable, 2008). The fact that these sexual behaviors and sexual violence perpetration share a host of risk factors may contribute to the strong association between the two.

Our discussion has already explained the ways in which NSES-CSE can potentially affect gender-related risk factors, as well as its potential to intervene in and prevent childhood sexual abuse. As these are two prominent explanations linking sexual risk behaviors to sexual violence perpetration, it is likely that the gender transformative components and childhood sexual abuse components of NSES-CSE can also have effects on the sexual behavior-related risk factors identified in Teten Tharp et al (2012). The traditional aim of comprehensive sex education is to impact sexual risk behaviors such as early sexual initiation, impersonal sex, and multiple sexual partners, as well as their associated outcomes such as pregnancy and HIV/STI acquisition, and there is substantial evidence that it is successful in doing so (Chin et al., 2012; Haberland, 2015a; Kirby, Laris, & Rolleri, 2007; Lindberg & Maddow-Zimmet, 2012). As has been previously noted, evidence also suggests that CSE programs that address gender and power are more successful at achieving its intended results than conventional sex education programs that do not address these risk factors (Haberland, 2015b). As the NSES takes a gender-transformative approach to comprehensive sex education, it is likely that it will be successful in reducing sexual risk behaviors as well as these shared risk factors.

Social-Emotional Skills

The last group of risk factors for SV perpetration fall under “social-emotional” skills that young children acquire and develop through adolescence, which include the ability to recognize and manage emotions, establish and maintain positive relationships, make responsible decisions, appreciate the perspective of others, and handle interpersonal situations constructively (Elias et al., 1997). Manifestations of poor social-emotional skills include several risk factors for SV perpetration, including a lack of empathy, cue misinterpretation, and delinquency. Social-emotional learning (SEL) programs aim to enhance the social-emotional skills of students, with the proximal goals being to foster “the development of five interrelated sets of cognitive, affective, and behavioral competencies: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making” (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011, p. 406)

The NSES include a core set of learning objectives explicitly aimed at enhancing the social-emotional skills of students (Table 4). By the end of 2nd grade, students should be able to identify healthy ways to express feelings, show respect, and control their behaviors. By the end of 5th grade, students practice recognizing and managing their emotions, learn healthy ways to communicate differences of opinions, explore the differences between healthy and unhealthy relationships, and practice skills necessary to treat themselves and others with dignity and respect. By the end of 8th grade, students learn to communicate respectfully, negotiate conflict fairly, apply effective decision-making strategies, and demonstrate ways to show empathy and treat each other with dignity and respect (Future of Sex Ed Initiative, 2012). This instruction falls directly under the purview of a SEL program.

A 2011 meta-analysis of SEL programs (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011) delineated the effects that SEL can have on a variety of skills, attitudes, and behaviors in children and adolescents relevant to SV perpetration risk factors. The meta-analysis combined findings from 213 studies. More than half of the programs were administered to elementary school students (56%) and about a third to middle school students (31%). Compared to control groups, students in the SEL intervention displayed enhanced SEL-related skills, attitudes, and positive social behaviors, demonstrated fewer conduct problems, had lower levels of emotional distress, and had improved academic performance. These programs thus show efficacy in affecting risk factors for SV perpetration, indicating that a school-based SEL program, like the NSES, can be successful.

K-12 Justification

One of the potentially most controversial dimensions of the prevention approach proposed here is that SV prevention begin in kindergarten. While some advocate strongly for this, others have argued just as strongly against the idea of providing “sex education” to kindergarteners (de Melker, 2015; Rohter, 2008), who will not begin engaging in perpetration behavior or sexual activity for some time. However, in line with the public health approach to prevention, it is crucial to look upstream at when in the developmental process the risk factors for perpetration begin to form (Harvey, Garcia-Moreno, & Butchart, 2007). As this paper has shown, a plethora of risk factors that can lead to perpetration do in fact begin to form early on in the life course, and thus engaging in prevention during this window is crucial. There are at least three important reasons for beginning prevention early.

The first and most obvious of the risk factors that need to be addressed early on is the prevention of child sexual abuse (CSA). The substantial burden of suffering associated with CSA underlines the importance of addressing sexual violence prevention early on. One in 9 girls and 1 in 53 boys under the age of 18 experience sexual abuse or assault at the hands of an adult (RAINN). From 2009–2013, Child Protective Services data show that 63,000 children a year were victims of sexual abuse—a statistic that is most likely an underestimate due to lack of reporting (RAINN). Of the 63,000 cases, 80% of perpetrators were parents and 6% were other relatives, and 88% of CSA cases involve a male perpetrator (RAINN). Taking a life course approach to prevention, and attending to the substantial evidence linking experiences of CSA to future perpetration of SV (Greathouse, Saunders, Matthews, Keller, & Miller, 2015) emphasizes the importance of integrating CSA prevention into a wider CSE curriculum as a strategy to reduce later perpetration.

The second and less obvious reason to begin early is that the formulation of gender roles and cognitions begins in childhood. While a comprehensive overview of feminist developmental psychology is beyond the scope of this paper, one key insight from that work is the idea that the gender inequities in power and status which exist in society influence children’s development (Leaper, 2000). A host of socialization practices exist that can conform children to gender roles and stereotypes very early on in the life course that go on to create their gender schemas in adolescence and adulthood. Children learn gender through their social interactions and daily activities, for example, when toys, sports, and activities are gender-typed, which can groom boys to compete for dominance. Children also learn gender by observing their own and the other genders and inferring patterns of appropriate behavior. From there, they begin socializing one another to conform to gender norms as part of peer group behavior. This can often manifest in “masculine protest,” the complete avoidance and devaluation of feminine-stereotyped qualities very early on (Leaper, 2000). These gender-shaping processes that often lead to male adherence to gender roles happen in early childhood development, and schools are often a vehicle through which this occurs (Adler, Kless, & Adler, 1992; Connell, 1996; Jordan, 1995; Messner, 2000; Renold, 2000, 2001; Swain, 2000). It is therefore critical to intervene in the gender-stereotyping process as early on as possible. Furthermore, teaching children about what it means to give and receive permission to do something and how to share and play with others can offer early, age-appropriate instruction about what it means to elicit or convey consent. Starting instruction as early as possible could help mitigate rigid and harsh gender stereotypes from forming, reducing potential perpetration behavior that stems from these risk factors later on in life. Intervening beginning in kindergarten, before children have engrained gender norms that guide their self-concepts, motivations, and expectations of others, could mitigate the potential harm that comes from rigid- and hyper-masculinity. Furthermore, early instruction to address gender-stereotyping might create safer climates for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and questioning (LGBTQ) and gender non-confirming (GNC) students as they grow up, who experience much higher rates of sexual harassment and violence than heterosexual and cisgender populations (Ford & Soto-Marquez, 2016; Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2012; Mitchell, Ybarra, & Korchmaros, 2014).

Lastly, as DeGue et al. (2014) delineated, most of the work in SV prevention thus far has focused on college students (70%), with the next highest number of interventions focusing on students in high school (14.3%). This may be in response to the legal requirements at the federal and state level (20 USCS § 1092; Lebioda, 2015; Morse, Sponsler, & Fulton, 2015; Office of Civil Rights, 2011) for institutions of higher education to offer or require some form of prevention education. However, the overwhelming focus on higher education as a site for SV prevention is intrinsically in tension with the underlying notion of primary prevention grounded in an understanding of the risk factors discussed throughout this paper. Even if college programs had been shown to be effective, many people experience sexual assault before entering college (Smith et al., 2017), and only roughly 59% of the adult population ever attends “some college” (Ryan & Bauman, 2016). Between half and three-quarters of the men who commit rape first do so as teenagers (Jewkes, Floor, & Lang, 2015). Therefore, while college-level interventions are most definitely part of the solution, there is a need to start primary prevention earlier in the lifecourse to reach individuals before they start perpetration behavior.

College-level interventions are most certainly necessary in an overarching SV prevention plan, but should not be the first interaction that individuals have with sexual violence prevention. The whole conceptualization of a life-course approach to primary prevention of SV presented in this paper, as well as the discussion of preventing the initial perpetration of SV by targeting the risk factors that are most implicated in the behavior, underlines the limits of having a first encounter with prevention concepts at the college level.

Limitations

Without question, while NSES-CSE holds the potential to successfully mitigate many of the risk factors implicated in sexual violence perpetration and—if implemented widely—subsequently curb the high rates of societal SV, it cannot do so alone. Child abuse provides a good example of both the promise and the limits of NSES-CSE as a prevention strategy; while evidence exists that it can have an impact on child sexual abuse, there are clearly a host of risk factors that CSE does not reach, such as events and interactions that happen in the home, and there is little evidence that NSES-CSE would be an appropriate or effective strategy for preventing the emotional or physical abuse of children. We have explored the role that NSES-CSE can play in preventing and stopping child sexual abuse, but there are other strategies that must also be employed to reach within the family where CSE cannot. Enhanced primary care and behavioral parent training programs are two such approaches (Fortson, Klevens, Merrick, Gilbert, & Alexander, 2016).

Furthermore, gender stereotypes that go on to create hypermasculinity complexes and entrench traditional gender roles often begin before a child is born—at “gender reveal” parties and via painting bedrooms pink or blue. NSES-CSE alone will not undo the inequitable societal gender norms that permeate every level of society. It cannot undo the gendered structure of the labor market, for example, or the gendered stereotypes disseminated through popular culture. It does, however, have the power to buffer and help students develop critical attitudes towards beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors about gender, and in that way mitigate the gender-related risk factors that can lead to perpetration.

A multipronged strategy is necessary to curb rampant sexual violence. Primary prevention of perpetration must be complemented by strategies that include secondary and tertiary prevention, such as initiatives that address perpetration recidivism, as well as strategies that help prevent victimization and work with survivors in the aftermath of their attack in a trauma-informed way, through the criminal justice system and elsewhere. For example, rape crisis centers and women’s shelters play a critical role in keeping women safe from violent household situations or in getting help after being attacked, and this paper does not aim to diminish those services in any way.

The work that we present here is not a systematic review, because there is very little in the way of evidence for effective prevention of sexual violence perpetration. Instead, we selected literature, including review articles that already synthesized various bodies of literature, to knit together knowledge across topic areas to suggest a new approach to prevention – one that is urgently in need of research and evaluation. This included summarizing the state of the field of SV perpetration, the risk factors for SV perpetration, interventions that have been shown to reduce these risk factors, and how NSES-CSE can effectively mitigate those risk factors. The authors conceptualized this endeavor as piecing together a puzzle: the pieces to the puzzle already exist (systematic reviews of perpetration risk factors, of the evidence regarding perpetration intervention effectiveness, and of how different risk factors can be mitigated by different types of interventions) but they needed to be assembled, so that future researchers could then take this as a charge to examine empirically the impact of NSES-CSE on SV perpetration (Figure 1). This paper’s aim is to stimulate research in sex education and sexual violence perpetration by connecting these previously separate bodies of research (Figure 1), all of which already had systematic reviews and analyses.

A further limitation is the focus here on cisgender, heterosexual men and women. Numerically, data suggest that the preponderance of assaults are perpetrated by cisgender heterosexual men and experienced by cisgender heterosexual women. However, the rates of sexual violence have been shown to be very high among LGBTQ populations (Ford & Soto-Marquez, 2016; Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2012; Mitchell, Ybarra, & Korchmaros, 2014). It is vital therefore for other work to fill the gap that we have left here, mapping the potential impact of CSE for those groups, and for subsequent evaluation research to explicitly examine the impact of CSE on rates of sexual assault among LGBTQ populations.

Another limitation is that K-12 CSE guided by the NSES has neither been widely implemented nor evaluated. The evidence chosen to support our argument was based on similar interventions—tailored to certain perpetration risk factors—in educational and small group settings that NSES-CSE would most likely resemble. It may be that the enormous recent popular media attention to sexual harassment and assault in the US (Baumgartner & McAdon, 2017; Beyond Harvey Weinstein, 2017; Fantz, 2016; Gabler, Twohey, & Kantor, 2017; Martin & Stolberg, 2017; Savransky, 2017; Zacharek, Dockterman, & Edwards, 2017) will provide an impetus to re-examine opportunities for population-level prevention, and CSE certainly offers one such opportunity.

Finally, it may seem politically unrealistic in the current federal environment to implement CSE, especially when funding streams are more closely tied to abstinence-only, or “sexual risk avoidance” programs than to comprehensive sexuality programs. However, despite federal funding having emphasized abstinence-only programs since the mid 1990s, states and municipalities have acted to increase access to comprehensive programs. California passed the Healthy Youth Act in 2015, which requires all public schools to teach CSE in grades 7–12 with the option to start earlier (California Department of Education, 2017), and New York City mandated in 2011 that public schools teach comprehensive sex education as well (NYC Department of Education, 2011). There are also other avenues outside of government to implement CSE, such as through private foundation funding. In 2009, The Grove Foundation, a private philanthropic foundation that strives to improve adolescent health, launched the Working to Institutionalize Sex Education (WISE) initiative (Butler, Sorace, & Beach, 2018). WISE’s mission is to provide support to school districts to advance comprehensive sex education programs and to document how implementation can be advanced and institutionalized. Rather than endorse a specific curriculum, WISE works with school districts to choose curricula that fit their needs. Implementation plans vary in scope from one grade level to K-12 programs, but at a minimum are all age-appropriate, evidence-informed, and compliant with state laws and standards. Since its launch, $7 million have been invested in 13 states; 88 school districts reached their implementation goals and institutionalized sex education and 788,865 unique students received new or improved sex education in school. The evaluation of WISE found that “resources and expertise help schools advance and meet their sex education institutionalization goals and that barriers that impede sex education can be mitigated, leading to increased quality and quantity of sex education in ready school districts” (Butler, Sorace & Beach, 2018).

Conclusion

Without question, a plethora of risk factors are implicated in sexual violence perpetration. Addressing one risk factor alone is unlikely to substantially reduce the incidence of sexual violence. A comprehensive strategy is needed to affect multiple risk factors across the social ecology. Individual, interpersonal, community, environmental, and societal level risk factors all contribute to health and social problems, including sexual violence. As noted in Table 5, NSES-CSE is potentially one powerful component of a multipronged strategy to lower the unacceptably high rates of sexual violence seen in the United States. Its unique value is implicit in the name itself: it is comprehensive (Figure 1). While sex education has been traditionally designed, implemented, and evaluated to reduce unplanned teenage pregnancies, HIV/STI acquisition, and the health risk behaviors that lead to these outcomes, it holds the potential to address sexual violence perpetration as well. As a high-dosage sequential program, it not only addresses these sexual risk behaviors, but it also embodies gender transformative programming, social and emotional learning, and child abuse prevention, which are four sets of risk factors associated with sexual violence perpetration, and it adheres to the commonalities of effective prevention programs, which have been widely cited in the literature. Most importantly, it begins to address the risk factors for perpetration behavior long before the onset of that behavior. Primary prevention is the most effective way of fully preventing poor health outcomes by mitigating risk factors from developing.

Table 5:

Critical findings

| Critical Findings |

| 1. Research shows that the majority of causal risk factors for SV perpetration fall into four categories: (1) sex, gender, & violence related risk factors; (2) child abuse related risk factors; (4) sexual behavior related risk factors & (4) social-emotional intelligence related risk factors. |

| 2. Current primary prevention strategies: (1) fail to address to majority of SV perpetration risk factors; and (2) do not use pedagogical approaches that characterize effective prevention programs. |

| 3. Evidence suggests that all four categories of risk factors can be modified through educational programming that employs characteristics of effective prevention. |

| 4. Comprehensive Sexuality Education, using the National Sexuality Education Standards (NSES), address the majority of SV perpetration risk factors, adhere to the qualities of effective prevention programs, and reach youth at a developmentally appropriate age, thus making it a potentially effective strategy at reducing SV perpetration. |

When implemented according to best practices and over a sustained period, NSES-CSE holds tremendous potential as an intervention approach; the implications of this argument for policy and practice are summarized in Table 6. No published peer-reviewed research to date evaluated the impact of NSES-CSE on sexually violent behavior, and this paper presents evidence for its potential to affect this outcome. The authors recommend that where NSES-CSE is implemented, it should be assessed for impact longitudinally by following students as they are exposed to CSE and looking at their behaviors over time. The social climate is certainly ripe for this work, with public figures being called out as sexual predators as a near-daily occurrence and a sustained public discussion about what, beyond holding the individuals accountable for their behavior, might produce a broader change in the climate. Remedial education on sexual violence in late adolescence and in college cannot by itself be the solution; comprehensive sex education that gets to the root of the problem before the problem begins may be one key component of a comprehensive strategy to end sexual violence.

Table 6:

Implications for policy, practice, and research

| Implications for Policy, Practice, and Research |

| • The unacceptably high rates of sexual violence (SV) in the United States underscore the need for effective primary prevention. |

| • K-12 Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE), following the National Sexuality Education Standards (NSES), shows promise as a solution to SV perpetration, but has not been rigorously evaluated with sexually violent behavior as an outcome. |

| • Researchers and practitioners should begin developing and testing CSE curricula that follow the NSES and adhere to the characteristics of effective prevention in order to reduce SV perpetration. |

| • States have considerable autonomy to implement these programs. |

| • Any comprehensive approach to stopping SV should include college-level programs, but rates of pre-college assault, the early emergence of risk factors for perpetration, life-course theory, and the proportion of the population that does not attend higher education all underline that higher education should not be the first interaction that adolescents and young adults have with SV prevention interventions. |

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the Department of Sociomedical Sciences, the Columbia Population Research Center (P2CHD058486), and the Sexual Health Initiative to Foster Transformation (SHIFT) for their support. They also thank Dr. John Santelli for his comprehensive review of this paper.

Contributor Information

Madeline Schneider, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University.

Jennifer S. Hirsch, Professor of Sociomedical SciencesMailman School of Public Health, Columbia University.

REFERENCES

- 20 USCS § 1092 (2013).

- Adler PA, Kless SJ, & Adler P (1992). Socialization to gender roles: Popularity among elementary school boys and girls. Sociology of Education,65(3), 169. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics.(2011). Parent Tips for Preventing and Identifying Child Sexual Abuse. Retrieved from http://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/news-features-and-safety-tips/Pages/Parent-Tips-for-Preventing-and-Identifying-Child-Sexual-Abuse.aspx

- Anderson KL (2005). Theorizing gender in intimate partner violence research. Sex Roles,52(11–12), 853–865. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong EA, Hamilton L, & Sweeney B (2006). Sexual assault on campus: A multilevel, integrative approach to party rape. Social Problems, 53(4), 483–499. [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL (2013). Go big or go home: Reaching for a more integrated view of violence prevention. Psychology of Violence, 3(2),115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, DeGue S, Jones K, Freire K, Dills J, Smith SG, Raiford JL (2016). STOP SV: A technical package to prevent sexual violence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, Smith SG, Breiding MJ, Black MC, & Mahendra R (2014). Sexual violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements, Version 2.0. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner FR, & McAdon S (2017, May 11). There’s been a big change in how the news media covers sexual assault. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/05/11/theres-been-a-big-change-in-how-the-news-media-cover-sexual-assault/?utm_term=.9d3ed1b3bf7d

- Breger ML (2014). Transforming cultural norms of sexual violence against women. Journal of Research in Gender Studies,4(2), 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Butler RS, Sorace D & Beach KH (2018). Institutionalizing sex education in diverse U.S. school districts. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(2), 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Education . (2017). Comprehensive sexual health & HIV/AIDS instruction. Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/ls/he/se/

- Casey EA, & Lindhorst TP (2009). Toward a multi-level, ecological approach to the primary prevention of sexual assault. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse,10(2), 91–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Sexual violence: Consequences. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/consequences.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2007). Health education curriculum analysis tool Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/hecat/

- Chin HB, Sipe TA, Elder R, Mercer SL, Chattopadhyay SK Santelli J (2012). The effectiveness of group-based comprehensive risk-reduction and abstinence education interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus, and sexually transmitted infections: Two systematic reviews for the guide to community preventive services. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(3), 272–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW (c1987). Gender and Power: Society, the Person and Sexual Politics. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW (1996). Teaching the boys: New research on masculinity, and gender strategies for schools. Teachers College Record, 98(2), 206–235. [Google Scholar]