Abstract

Most of the abnormal cardiac conduction system findings are atrial tachyarrhythmias in cardiac sarcoidosis. However, atrial standstill as a sick-sinus syndrome could be complicated in the case of diffuse atrial fibrosis. Herein, we present an interesting and valuable case of atrial standstill with suspected isolated cardiac sarcoidosis.

<Learning objective: The chronic inflammation caused by isolated cardiac sarcoidosis could impair the conduction system. With atrial standstill, we recommend a comprehensive effort to investigate the potential etiology including cardiac sarcoidosis, particularly in the case of enlarged atrium and ventricular dysfunction.>

Keywords: Isolated cardiac sarcoidosis, Atrial standstill, Arrhythmia

Introduction

The chronic inflammation caused by cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) could impair the cardiac conduction system which is usually associated with tachyarrhythmia or conduction block. With atrial standstill, we recommend a comprehensive effort to investigate the potential etiology including CS, particularly in the case of enlarged atrium and ventricular dysfunction.

Case report

A 54-year-old male was admitted for evaluation of dizziness. His vital signs, body temperature, and serological tests were within normal limits except for a high N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide level (27,550 pg/mL). The electrocardiogram revealed the absence of P-wave and ventricular escape rhythm with 36 beats per minute (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

The patient's electrocardiography shows the total absence of P-waves and ventricular escape beats (bradycardia of 36 bpm) (A). An action potential originating from the right atrium was not observed, and atrial stimulation with high output trigger failed to produce and maintain right atrial activation (B).

A chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly, and echocardiography revealed biatrial enlargement, decreased left ventricular (LV) contractility (ejection fraction; 38%), and myocardial thinning of the interventricular basal septum. Color Doppler imaging revealed severe mitral and tricuspid regurgitation due to annular dilation and LV dysfunction. Holter monitoring revealed the total absence of P-wave, ventricular escape beats, and ventricular pause (maximal duration: 6.72 s), as well as sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT).

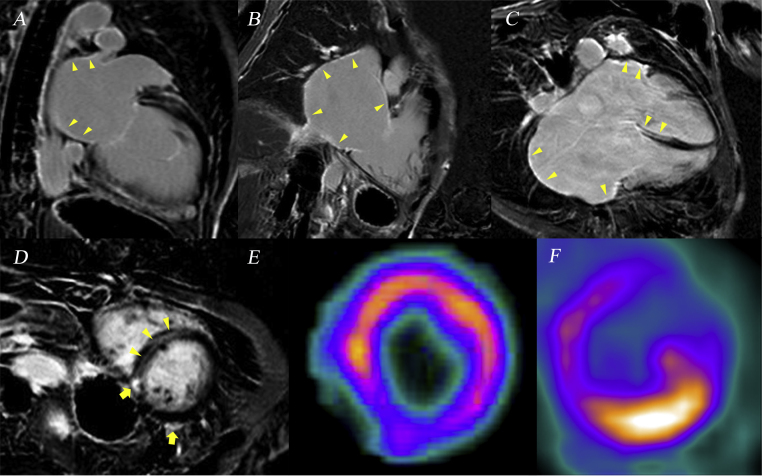

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging was performed with a 1.5 T scanner (Avanto, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with 6-channel phased array cardiac coil. Atrial late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) images were acquired about 15 min after gadolinium injection using 3D navigator and electrocardiographically gated inversion-recovery gradient-echo sequence: voxel size = 1.25 mm × 1.25 mm × 2.5 mm, slice size = 2 mm, inversion time = 300 ms, repetition time = 5.4 ms, echo time = 2.3 ms, flip angle = 20°. CMR revealed epicardial delayed enhancement of gadolinium in the basal inferior and inferoposterior wall at the mid-ventricular level (Fig. 2). Mid-wall linear delayed enhancement was also observed at the thinned interventricular basal septum in the apical 4-chamber view and at the mid-ventricular septum in the parasternal short-axis view. Both atria showed LGE in the apical 2-/4-chamber view. Cardiac perfusion and positron emission tomography (PET) studies indicated decreased perfusion with 13N-ammonia in the inferoposterior segment despite an increased uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose. However, PET did not show any evidence of systemic sarcoidosis and inflammatory response. An electrophysiological study (EPS) was performed to evaluate the electrical status of the atrium considering synchronized permanent pacemaker implantation. However, the atrium was not captured with the maximum output of current, and there were no electrical activities in the atria (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 2.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography for cardiac sarcoidosis. (A and B) Delayed enhancement of gadolinium is observed in both the left and right atria (arrow-head) in each apical 2-chamber view. (C) Those findings are also seen in the apical 4-chamber view with the basal septum thinned and enhanced (arrow-head). (D) Strong epicardial enhancement is noted at the basal inferoposterior wall (arrow), along with interventricular septum (arrow-head). (E) Cardiac perfusion with 13N-ammonia was decreased at the basal inferoposterior wall. (F) An increased uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose was observed in the same lesion.

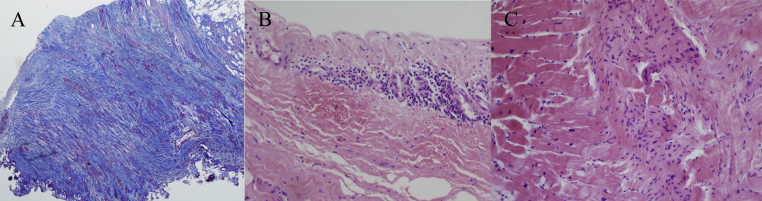

Surgical biopsies of both the atria and myocardium were performed during surgical correction of both valvular regurgitations. Severe fibrosis was noted in both atria, and inflammatory cells were infiltrated in the LV myocardium without granuloma compatible for sarcoidosis (Fig. 3). After correction of valvular regurgitation, a single-chamber implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) was implanted due to documented sustained VT. The patient was discharged and managed with beta-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and steroid. However, he has not shown a remarkable improvement in LV systolic function even though his clinical symptoms improved.

Fig. 3.

Based on surgical biopsy, massive fibrosis is observed in the left atrium (A). The inflammatory cells infiltrated the right atrium (B) and left ventricles (C).

Discussion

The prevalence of CS may vary from approximately 5% to 50% of cases of systemic sarcoidosis, and it is characterized by myocardial inflammation, impairment of the conduction system, arrhythmias, and decreased ventricular function [1]. Regarding atrial involvement, atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia that is associated with inflammation and/or fibrosis of the atria [2].

In particular, isolated CS is rare, and difficult to diagnose without high suspicion. Because of limitation of biopsy, two thirds of the suspected CS patients could not be identified and did not have appropriate medical concern despite typical cardiac features [3]. Recently, it has been suggested that isolated CS could exist without pathologic findings of granuloma and clinical diagnosis of isolated CS is characterized as follows [4]: clinical symptoms suggestive of heart disease, arrhythmia or conduction disturbances, LV systolic dysfunction, absence of coronary artery disease, abnormal cardiac imaging of CMR, or radionuclide scan such as PET.

Atrial standstill, which is not a common disorder, is characterized by the absence of atrial electrical impulse production, and the diagnosis usually requires an EPS for exclusion of similar disorders such as fine AF [5]. Among the suggested etiological mechanisms, chronic inflammation or infiltration may be involved, and it may be accompanied by resultant fibrosis of both atria. Although CS frequently involves the LV myocardium including the interventricular basal septum, it is not surprising that CS may cause atrial standstill in the long term because it is a systemic and inflammatory disorder.

Once the conduction system is affected by CS, atrial arrhythmias occur more frequently than ventricular arrhythmias [6]. The incidence was reported to reach 20–30%: atrial tachycardias such as AF are common, whereas bradycardia has been rarely reported [6]. It is unclear whether inflammatory involvement or fibrosis caused by chronic pressure loading to the atrium would be associated with atrial standstill. However, the fibrosis occurs predominantly at the late stage of CS: both decreased perfusion and inflammation are observed.

There has not been clear consensus about treatment of isolated CS, but valvular disorders such as severe regurgitation needed surgical correction considering patient's symptoms, chronic volume overloading, and ventricular dysfunction. Mitral or tricuspid regurgitation was secondary to annular dilation and LV dysfunction, not to primary valvular disorder such as prolapse. Huge atrial enlargement per se has been related with chronic volume overloading status, and diffuse LGE could indicate myocardial fibrosis, irreversible LV dysfunction, and unfavorable prognosis even with antiarrhythmic and steroid therapy [4], [7], [8].

It is necessary to unravel the causal relationship between inflammatory sarcoidosis and fibrotic changes in the atrium or lesion involvement. However, this is complicated by a long delay between CS activity and its diagnosis. Although there is a limitation of similar thickness between CMR image resolution and atrial wall, we determined to obtain both atrial specimens surgically to overcome those limitations. Considering atrial fibrosis, CMR would provide an incremental value in identifying atrial fibrosis over ventricular fibrosis.

Additionally, we did not perform electroanatomical bipolar voltage mapping which seems to have good correlation with atrial or ventricular scar or fibrosis distribution detected on CMR-LGE [9], [10]. However, there are limited data about translating this to the atrial fibrosis and thus, clear evidence may be required with regard to their relationship [10].

Conclusion

This case underlines the requirement of a comprehensive evaluation to detect the etiology of atrial standstill, particularly in cases of biatrial enlargement and ventricular dysfunction. The diagnostic confirmation could be based on cardiovascular imaging or tissue biopsy.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hulten E., Aslam S., Osborne M., Abbasi S., Bittencourt M.S., Blankstein R. Cardiac sarcoidosis—state of the art review. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2016;6:50–63. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2015.12.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zipse M.M., Sauer W.H. Electrophysiologic manifestations of cardiac sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:485–492. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283644c6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kandolin R., Lehtonen J., Graner M., Schildt J., Salmenkivi K., Kivistö S.M., Kupari M. Diagnosing isolated cardiac sarcoidosis. J Intern Med. 2011;270:461–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isobe M., Tezuka D. Isolated cardiac sarcoidosis: clinical characteristics, diagnosis and treatment. Int J Cardiol. 2015;182:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolliscroft J., Tuna N. Permanent atrial standstill: the clinical spectrum. Am J Cardiol. 1982;49:2037–2041. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(82)90226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cain M.A., Metzl M.D., Patel A.R., Addetia K., Spencer K.T., Sweiss N.J., Beshai J.F. Cardiac sarcoidosis detected by late gadolinium enhancement and prevalence of atrial arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:1556–1560. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.01.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shafee M.A., Fukuda K., Wakayama Y., Nakano M., Kondo M., Hasebe Y., Kawana A., Shimokawa H. Delayed enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is a poor prognostic factor in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. J Cardiol. 2012;60:448–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kron J., Sauer W., Mueller G., Schuller J., Bogun F., Sarsam S., Rosenfeld L., Mitiku T.Y., Cooper J.M., Mehta D., Greenspon A.J., Ortman M., Delurgio D.B., Valadri R., Narasimhan C. Outcomes of patients with definite and suspected isolated cardiac sarcoidosis treated with an implantable cardiac defibrillator. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2015;43:55–64. doi: 10.1007/s10840-015-9978-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison J.L., Jensen H.K., Peel S.A., Chiribiri A., Grøndal A.K., Bloch L.Ø., Pedersen S.F., Bentzon J.F., Kolbitsch C., Karim R., Williams S.E., Linton N.W., Rhode K.S., Gill J., Cooklin M. Cardiac magnetic resonance and electroanatomical mapping of acute and chronic atrial ablation injury: a histological validation study. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1486–1495. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim H.S., Yamashita S., Cochet H., Haïssaguerre M. Delineating atrial scar by electroanatomic voltage mapping versus cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: where to draw the line. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2014;25:1053–1056. doi: 10.1111/jce.12481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]