Abstract

Cold agglutinin disease (CAD) is a form of autoimmune hemolytic anemia caused by cold-reacting autoantibodies. The manifestations of CAD are commonly anemia, acrocyanosis, and fatigue caused by hemolysis and agglutination of red blood cells (RBCs) at a temperature lower than normal body temperature. We report a case of CAD presenting with pulmonary embolisms in an 86-year-old man.

The patient visited our emergency department complaining of acute chest pain and respiratory distress. Laboratory data showed decreased RBC and hematocrit and markedly elevated mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) and MCH concentration (MCHC). A contrast-enhanced computed tomographic scan demonstrated bilateral massive pulmonary embolisms. After admission, diagnosis of CAD was made on the basis of a high cold agglutinin titer without other factors of coagulation.

CAD can contribute to the onset of pulmonary embolisms. It is necessary to incubate blood samples at 37 °C when laboratory data show markedly elevated MCH and MCHC and to consider the presence of cold agglutinins as an underlying disorder for the formation of venous thrombosis.

<Learning objective: Cold agglutinin disease can contribute to the onset of pulmonary embolisms. It is necessary to incubate blood samples at 37 °C when laboratory data showed markedly elevated mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) and MCH concentration (MCHC) and to consider the presence of cold agglutinins as an underlying disorder for the formation of venous thrombosis. Complete blood count including MCH and MCHC is always ordered, but we may have overlooked the meaning of abnormal results. We must be aware of these parameters and carefully examine the underlying mechanisms of thrombosis.>

Keywords: Cold agglutinin disease, Pulmonary embolism, Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

Introduction

Cold agglutinin disease (CAD) is a form of autoimmune hemolytic anemia caused by cold-reacting autoantibodies. The manifestations of CAD are commonly anemia, acrocyanosis, and fatigue. We report a case of CAD presenting with pulmonary embolisms.

Case report

An 86-year-old man living independently visited our emergency department complaining of acute chest pain and respiratory distress. The symptoms had occurred when he got up to go to the toilet late at night on the coldest day that we had had in 40 years.

He had a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic anemia.

On arrival, he was alert and his initial vital signs were temperature of 35.0 °C, pulse of 83 beats per minute, blood pressure of 126/48 mmHg, respiratory rate of 12 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 88% while breathing ambient air. On physical examination, he had conjunctival icterus. A blood test showed decreased red blood cell (RBC) count and hematocrit and elevated mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) and MCH concentration (MCHC). After incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, MCH and MCHC showed almost normal values (Table 1). Echocardiography revealed right ventricular dilation and tricuspid regurgitation. Ejection fraction was 63%, and transpulmonary pressure gradient was 39 mmHg. Electrocardiography was within normal limits.

Table 1.

Complete blood count results before and after the incubation of blood sample at 37 °C for 30 min.

| Components | Reference rangea | Incubation at 37 °C for 30 min |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | ||

| RBC (×1012/L) | 4.00–5.52 | 1.06 | 2.57 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.2–17.2 | 9.9 | 10.0 |

| HCT (%) | 40.4–51.1 | 11.2 | 26.0 |

| MCV (fl) | 85.6–102.5 | 105.7 | 101.2 |

| MCH (pg) | 28.2–34.4 | 93.4 | 38.9 |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 31.8–34.8 | 88.4 | 38.5 |

| PLT (×109/L) | 148–339 | 252 | 221 |

| WBC (×109/L) | 3.6–9.6 | 5.8 | 6.2 |

RBC, red blood cell; HCT, hematocrit; MCV, mean cell volume; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; PLT, platelet; WBC, white blood cell.

The reference ranges used in our hospital are for adults who are not pregnant and do not have medical conditions that could affect the results.

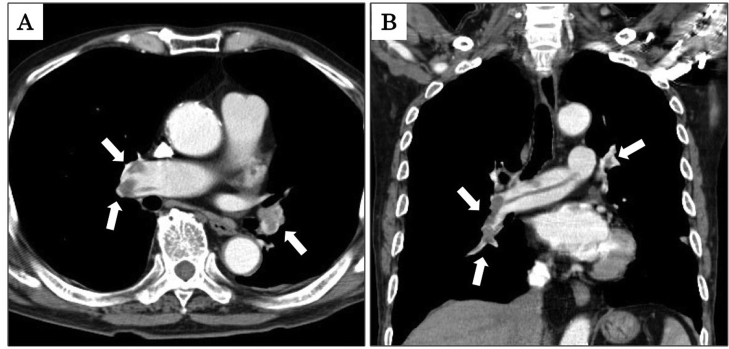

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated bilateral filling defects of pulmonary arteries (Fig. 1) and lower extremity deep vein thrombosis. There was no lymphadenopathy, no hepatosplenomegaly, and no opacity in his lungs. We made a diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism with lower extremity deep vein thrombosis.

Fig. 1.

Axial and coronal images of a contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showing bilateral pulmonary embolisms indicated by “(arrows)” (Panels A and B, respectively).

He was admitted to our hospital, and anticoagulation therapy was started with continuous heparin infusion 500 units per hour and apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily at the same time. Additional laboratory data showed hemolytic anemia with elevated levels of indirect bilirubin, lactic dehydrogenase (LDH), and reticulocytes and lowered level of haptoglobin. Complement levels were low. The result of a direct Coombs test was positive for the complement component 3 and negative for IgG. Anti-I antibody was detected in his serum. The titer of cold agglutinin was 1 in 8192, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM was negative. He did not have lupus anticoagulants, anticardiolipin antibodies, or antinuclear antibodies. Levels of prothrombin time and international normalized ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time, protein C and protein S were normal. Based on these results, we made a diagnosis of autoimmune hemolytic anemia and pulmonary embolisms caused by CAD. His body was kept warm and heparin was continued for 5 days. On the 10th day after admission, a contrast-enhanced CT scan showed notable reduction of the pulmonary embolism and residual lower extremity thrombosis. He was discharged from our hospital and apixaban is still continued at 5 months after the admission.

Discussion

The patient's clinical course provided two important clinical suggestions: (1) CAD can contribute to the onset of pulmonary embolisms and (2) it is necessary to incubate blood samples at 37 °C when laboratory data show markedly elevated MCH and MCHC.

First, CAD can contribute to the onset of pulmonary embolisms. CAD is rare, accounting for 15% of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) cases. And the incidence of CAD is 1 per million people per year [1]. Patients with CAD occasionally have symptoms related to agglutination of RBCs exposed to a low temperature, such as acrocyanosis and livedo reticulitis. Thromboembolism is a recognized complication of AIHA. Cytokine-induced expression of monocyte or endothelial tissue is considered as the factor of thrombotic tendency in patients with AIHA [2], [3]. It also might be a complication of autoimmune hemolytic anemia including CAD. Actually, only two cases of CAD with pulmonary embolism have been reported [4], [5]. And, superior mesenteric artery thrombosis and acute ischemic stroke were also reported in some patients with CAD [6], [7], [8].

Our patient, who had no prior infection or other underlying hypercoagulable state, visited our hospital late at night on the coldest day that we had had in 40 years. It was −3.9 °C that night. In that winter, a cold wave struck much of East Asia including Japan. During the winter, our patient often felt fatigue and a laboratory test ordered by his family doctor showed anemia. Agglutination and hemolysis may therefore have progressed gradually and consumed the complement over the cold season.

A low temperature is a trigger for agglutination of RBCs in patients with CAD [9]. Cold agglutinins are particular cold-reactive antibodies that react with RBCs when the blood temperature drops below normal body temperature causing increased blood viscosity and red blood cell clumping. When the patients with CAD were cooled during cardiopulmonary bypass, agglutinates in the right atrium or a white aggregate forming in the reservoir were reported [10], [11]. The blood viscosity and agglutination cause the reduced blood flow and stasis, which may have contributed to the gradual formation of venous thrombosis [12].

Second, it is necessary to incubate blood samples at 37 °C when laboratory data show markedly elevated MCH and MCHC. MCH and MCHC are calculated by dividing hemoglobin by RBC and hematocrit, respectively. In the presence of cold agglutinin, a low temperature induces RBC agglutination, and an automated complete blood count analyzer shows decreases in RBC and hematocrit. Hemoglobin concentration is not affected by cold agglutinins, and MCH and MCHC are therefore markedly increased [13], [14]. In our patient, extremely elevated MCH and MCHC guided us to recognize agglutination of RBC. After incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, the blood sample showed improvement of the complete blood count result, which was a clue for the diagnosis of CAD as an underlying disorder for the pulmonary embolism (Table 1).

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Swiecicki P.L., Hegerova L.T., Gertz M.A. Cold agglutinin disease. Blood. 2013;122:1114–1121. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-474437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendrick A.M. Auto-immune haemolytic anaemia – a high-risk disorder for thromboembolism? Hematology. 2003;8:53–56. doi: 10.1080/1024533021000059474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman P.C. Immune hemolytic anemia – selected topics. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009;2009:80–86. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murayama A., Ayabe T., Toyama K., Nakamura Y. Pulmonary embolism and hemolytic anemia in a patient with cold agglutinin disease. Jpn Circ J. 1981;45:1306–1308. doi: 10.1253/jcj.45.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su H.-Y., Jin W.-J., Zhang H.-L., Li C.-C. [Clinical analysis of pulmonary embolism in a child with Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia] Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2012;50:151–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson M.L., Menjivar E., Kalapatapu V., Hand A.P., Garber J., Ruiz M.A. Mycoplasma pneumoniae associated with hemolytic anemia, cold agglutinins, and recurrent arterial thrombosis. South Med J. 2007;100:215–217. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000254212.35432.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirono H., Kubota T., Funakoshi K., Watanabe T., Hasegawa K., Soga K., Shibasaki K. [A case of superior mesenteric artery occlusion associated with idiopathic chronic cold agglutinin disease] Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2011;108:791–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin H., Sun W., Sun Y., Huang Y., Sun Y. Report of cold agglutinins in a patient with acute ischemic stroke. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:1–3. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0482-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyckholm L.J., Edmond M.B. Images in clinical medicine. Seasonal hemolysis due to cold-agglutinin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:437. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602153340705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park J.V., Weiss C.I. Cardiopulmonary bypass and myocardial protection: management problems in cardiac surgical patients with cold autoimmune disease. Anesth Analg. 1988;67:75–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vizzini S., Kako H., McKee C., Hodge A., Tobias J.D. Intraoperative detection of cold agglutinins during cardiopulmonary bypass in a child. J Med Cases. 2015;6:109–112. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackman N. New insights into the mechanisms of venous thrombosis. J Clin Investig. 2012;122:2331–2336. doi: 10.1172/JCI60229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zandecki M., Genevieve F., Gerard J., Godon A. Spurious counts and spurious results on haematology analysers: a review. Part II: White blood cells, red blood cells, haemoglobin, red cell indices and reticulocytes. Clin Lab Haematol. 2007;29:21–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2257.2006.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ercan S., Caliskan M., Koptur E. 70-Year old female patient with mismatch between hematocrit and hemoglobin values: the effects of cold agglutinin on complete blood count. Biochem Med. 2014;24:391–395. doi: 10.11613/BM.2014.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]