Abstract

Introduction

Yokukansan is one of the traditional herbal medicines (Kampo medicine in Japan) commonly used in the treatment of the Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD). We performed an observational study using yokukansankachimpihange, which contains a nobiletin-rich Citrus reticulata, to determine whether it could improve BPSD as well as cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer disease (NINCDS-ADRDA).

Methods

Forty-six (23 vs. 23) patients were enrolled in the study sample (donepezil group vs. donepezil + yokukansankachimpihange group). The BPSD were assessed using the Frequency-Weighted Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD-FW). The Mini-Mental State Examination and the Digit Symbol test of WAIS-R were used to evaluate impairment of global cognitive function and executive function, respectively.

Results

No significant changes in the cognitive functions or the total BPSD scores were noted for either treatment group. Regarding the subscales of the BPSD, the subscale of Diurnal Rhythm showed a significant decrease after the treatment, and those of Affective Disturbance and Anxiety and Phobias tended to be decreased. The donepezil + yokukansankachimpihange group had a lower rate of use of anti-psychotics compared with the donepezil group, although this was not statistically significant.

Conclusion

These results suggest that combined treatment of yokukansankachimpihange with donepezil has a positive clinical effect on improving the behavioral abnormalities, despite the lack of any effect on cognitive functions. Improvements in the diurnal rhythm may improve affective disturbance and anxiety. Thus, yokukansankachimpihange is considered to have a mild stabilizing effect on emotion.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, BPSD, Kampo medicine, Yokukansankachimpihange

Introduction

Aging of the world’s population has led to an increase in the number of elderly people with dementia. In addition to cognitive impairment, these elderly frequently show abnormal behaviors, such as delusion, agitation, and wandering [1–3], defined as the Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD) [4]. Since patients manifesting BPSD can be a major burden for their families and caregivers [5], and since the quality of life of such patients deteriorates, due to earlier [6] and/or increased institutionalization [7], adequate treatment or care is necessary.

Although the prescription of anti-psychotic drugs for a limited period by dementia specialists is clinically useful [8], easy administration of such drugs by non-specialists might lead to adverse effects, such as drug-induced Parkinson syndrome [9]. Alternatively, traditional herbal medicines can be used clinically for treatment.

Yokukansan is one of the traditional herbal medicines (Kampo medicine in Japan) that is commonly used for the treatment of BPSD [10], and some neuropharmacological actions have been reported [11]. A recent systematic review [12] described five RCTs with 381 patients, versus controls, that reported that yokukansan significantly decreased BPSD total scores, as well as the BPSD subscale of “active symptoms”, i.e., delusions, hallucinations, and agitation/aggression. However, the review reported that yokukansan was not particularly beneficial for Alzheimer disease (AD) patients.

Among the compounds in herbal medicines, Kawahata et al. [13]. discovered nobiletin as a natural compound that exhibits anti-dementia actions in animals. Citrus reticulata or C.unshiu peels are employed as “chinpi” and include a nobiletin (Nchinpi, a nobiletin-rich Citrus reticulata). There is only one Kampo drug that contains Nchinpi, a nobiletin-rich Citrus reticulata, yokukansankachimpihange.

Yokukansankachimpihange contains yokukansan and chinpi, which have traditionally been used for the treatment of neurasthenia, hysteria, insomnia, menopausal neurosis, and pediatric epilepsy [14]. Three types of yokukansankachimpihange are available for clinical use; however, only one type, produced by Kotaro-Kampo Pharmaceutical, includes Nchinpi. Therefore, we have used the yokukansankachimpihange produced by Kotaro-Kampo Pharmaceutical.

Since cholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, are already established drugs for AD [15], a treatment only using Kampo medicine without a cholinesterase inhibitor would be ethically inappropriate. Thus, we designed the observational study with two groups, i.e., yokukansankachimpihange with donepezil versus donepezil alone (yokukansankachimpihange control).

The drug yokukansankachimpihange has been approved to be administered for dementia patients in Japan. Whether or not administered is completely the decieion of individual doctors, different from the situation of donepezil as recommended by the guideline of dementia medicine. Thus, the study is an observation study and not a clinical trial of a new drug.

The aim of this study is to prove the hypothesis that: since yokukansankachimpihange produced by Kotaro-Kampo Pharmaceutical contains yokukansan and Nchinpi, the BPSD would be improved specifically for the “active symptoms”, i.e., delusions, hallucinations, and agitation/aggression, through the yokukansan, and that cognitive function could also be improved by the Nchinpi.

Methods

This is not a clinical trial, but an observational study of drugs already used in a routine medical practice. Thus, this study was performed by routine health insurance in the Japanese system.

Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient and from their family members, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Osaki-Tajiri SKIP Center.

Patients

This study was performed at the memory clinic at the Osaki-Tajiri SKIP Center [16]. This is an observational study and not a critical trial using randomization.

From among 104 consecutive outpatients with dementia attending the clinic between October 2011 and August 2014, 114 patients with AD who met the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were selected. Secondly, patients who were treated with donepezil without yokukansankachimpihange, and the patients who were treated with donepezil followed by yokukansankachimpihange were selected. Thirdly, patients were selected from among both groups by matching the MMSE scores. Ultimately, 46 (23 vs. 23) patients were enrolled as the study sample (donepezil group vs. donepezil + yokukansankachimpihange group).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) probable AD according to the diagnostic criteria for the NINCDS-ADRDA (National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association) [2, 17] and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [18] scores of 10 or greater. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) anti-psychotic or antidepressant drug use; (2) any Kampo medicine use; (3) history of stroke, cerebral contusion, or other systematic disorders that could affect central nervous system function, i.e., hypothyroidism or decreases in vitamin B1, B6, B12; and (4) cerebrovascular diseases shown by MRI.

The patients in the donepezil group received donepezil 10 mg/day after breakfast, after confirmation that there were no side effects following a trial period in which they were treated with 3 mg/day for 2 weeks. The donepezil + yokukansankachimpihange group patients received the same dose of donepezil together with yokukansankachimpihange 3.0 three times after the meals.

Sources of Drugs

The donepezil and yokukansankachimpihange are officially recognized drugs for treatment. The donepezil is from Eisai, and the yokukansankachimpihange is from Kotaro-Kampo. The former is a tablet and the latter a powder.

Neurobehavioral Assessments

Behavioral Abnormalities

Behavioral abnormalities were assessed using the Frequency-Weighted Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD-FW) [19].

According to the scale, the BPSD are classified into 7 subcategories: A, Paranoid and Delusional Ideation; B, Hallucinations; C, Activity Disturbances; D, Aggressiveness; E, Diurnal Rhythm Disturbances; F, Affective Disturbance; and G, Anxiety and Phobias. Activity Disturbances (C) involves wandering or meaningless behavior, Aggressiveness (E) includes violent speech or behavior towards others, and Diurnal Rhythm Disturbance (E) includes disturbances in daily sleeping/waking rhythms. Categories A, B, F and G are defined as psychological symptoms and categories C, D and E as behavioral symptoms.

Cognitive Functions

From the routine neurobehavioral assessment tools available, the MMSE and the Digit Symbol test of WAIS-R were selected to evaluate global cognitive function and executive function, respectively.

The MMSE is an established test that assesses global intellectual function. For the Digit Symbol subtest, we have previously demonstrated that patients who were responsive to donepezil had higher baseline scores compared with non-responders, and that the scores correlated with the density of donepezil binding sites, as assessed using [11C]-donepezil positron emission tomography [20]. Thus, we considered that the two tests in combination were appropriate assessment tools for examining the efficacy of drug treatment for AD.

Analyses

Since the drug treatments were performed by one of the authors, an independent research technician, who was blinded to all clinical data, analyzed the data using the SPSS software. K.M. is a board-certified instructor for neurology and geriatric psychiatry.

Changes in Cognitive Functions

The datasets at two time points were analyzed blindly: at pre-treatment (i.e., the start of donepezil treatment with or without yokukansankachimpihange for each of the two groups), and at the assessment time (defined here as “post-treatment”), including the MMSE and digit symbol (DS) for general cognitive and executive functions, respectively.

Changes in the BPSD

The BEHAVE-AD-FW scores were similarly analyzed at the two time points (i.e., pre- and post-treatment).

Use of Anti-Psychotic Drugs in Each Group

Risperidone and levomepromazine are commonly used atypical anti-psychotics for the treatment of BPSD at the center [8]. The use of these drugs during the observation period was assessed between the two groups.

Results

Table 1 presents the clinical data for both groups.

Table 1.

Clinical data for both groups

| n | Men/women | Age | Dementia severity: mild/moderate | Interval between treatment and assessment (months) | MMSE | DS | BEHAVE-AD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donepezil + Yokukansanka chimpihange | 23 | 4/19 | 77.7 (5.6) | 15/8 | 10.5 (5.7) | 17.8 (4.6) | 21.8 (8.9) | 13.2 (21.0) |

| Donepezil | 23 | 5/18 | 78.0 (6.7) | 15/8 | 10.4 (7.3) | 17.7 (4.7) | 19.1 (10.5) | 10.3 (10.1) |

Values are the mean (SD)

MMSE mini mental state examination, DS digit symbol

Changes in Cognitive Functions

The mean (SD) post-treatment MMSE scores for the two groups (donepezil + yokukansankachimpihange vs. donepezil groups) were 16.3 (3.8) versus 18.3 (4.8), and those of Digit Symbol were 18.1 (9.7) versus 19.4 (7.6), respectively. None of the values were significantly different between the groups or over time (i.e., pre- vs. post-treatment).

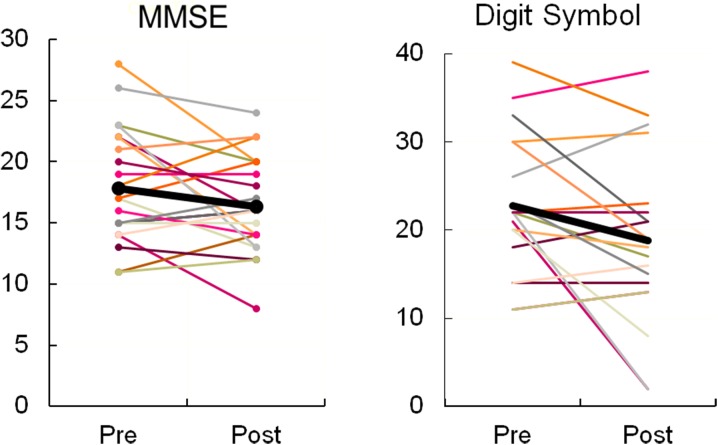

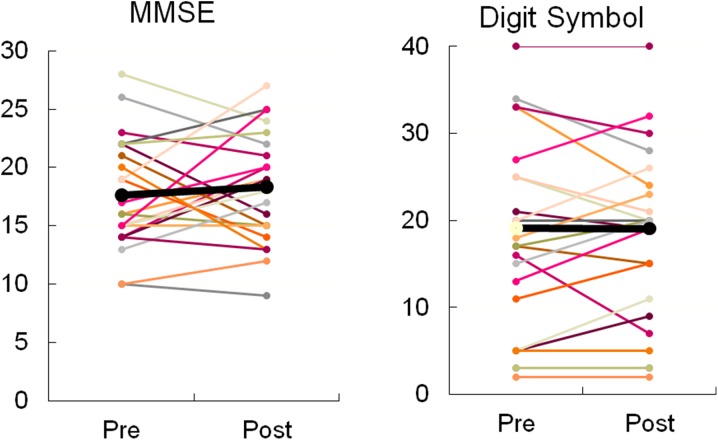

Figure 1 illustrates the individual changes for both tests in the donepezil + yokukansankachimpihange group. Similar changes are shown in Fig. 2 for the donepezil group. No significant changes were noted for either group.

Fig. 1.

Effects of donepezil and Yokukansankachimpihange on cognitive function. MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination. MMSE: Z = − 1.443, p = 0.149; Digit Symbol: Z = − 1.636, p = 0.102, by the Wilcoxon rank test. Thick black line indicates the mean

Fig. 2.

Effects of donepezil on cognitive function. MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination. MMSE: Z = 0.553, p = 0.580; Digit Symbol: Z = 0.380, p = 0.704, by the Wilcoxon rank test. Thick black line indicates the mean

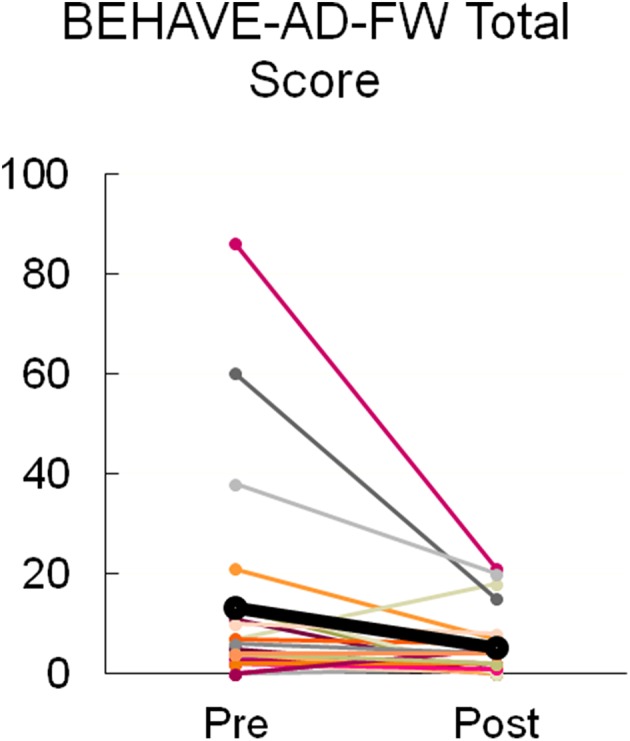

Changes in the BPSD

Figure 3 illustrates the changes in the BEHAVE-AD-FW total score for the donepezil + yokukansankachimpihange group. The score decreased significantly after treatment.

Fig. 3.

Effects of donepezil and Yokukansankachimpihange on BPSD. BEHAVE-AD-FW the Frequency-Weighted Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer Disease Rating Scale, BPSD behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Wilcoxon rank test: Z = − 2.979, p = 0.003. Thick black line indicates the mean

Regarding the subscales of BEHAVE-AD-FW, the statistical significances (Wilcoxon rank test) were as follows: For A, Paranoid and Delusional Ideation (Z = − 1.265, p = 0.206); B, Hallucinations (Z = − 1.069, p = 0.285); C, Activity Disturbances (Z = − 1.432, p = 0.152); D, Aggressiveness (Z = − 0.720, p = 0.471); E, Diurnal Rhythm Disturbances (Z = − 2.368, p = 0.018); F, Affective Disturbance (Z = − 1.703, p = 0.089); and G, Anxiety and Phobias (Z = − 1.879, p = 0.060). Only the subscale of F showed a significant decrease after the treatment, although those of F and G exhibited a tendency to be decreased.

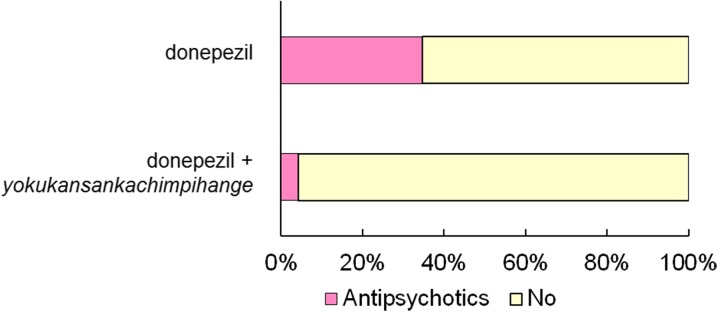

Use of Anti-Psychotic Drugs in both Groups

Figure 4 presents the proportion of subjects that were using atypical anti-psychotics (risperidone, levomepromazine). About 35% patients in the donepezil group required anti-psychotics for the treatment of BPSD, especially in the treatment of “active symptoms.” Although no significant difference was noted (Chi square test), the donepezil + yokukansankachimpihange group exhibited a lower rate of anti-psychotic use compared with the donepezil group.

Fig. 4.

Percent subjects using atypical anti-psychotics (risperidone, levomepromazine)

Discussion

Changes in Cognitive Functions

Surprisingly, neither donepezil alone nor donepezil and yokukansankachimpihange showed any effect on cognitive functions in this study. As shown in Figs. 1 and 2, there were three responders, as indicated by a MMSE increase of 3 + points [20] in the donepezil + yokukansankachimpihange group, compared with 10 in the donepezil group. The tendency for the donepezil group to include more responders compared with the donepezil + yokukansankachimpihange group could lead us to the hypothesis that the combined use might cancel out the effects of each of the drugs. However, the small sample size did not allow us to perform a secondary analysis.

Changes in the BPSD

A systematic review of RCTs related to the efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, in the treatment of BPSD of AD was recently published [15]. The evidence supporting the efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors in BPSD is limited. Thus, we should discuss the positive effect of the combined use of donepezil and yokukansankachimpihange.

In contrast to the hypothesis introduced by the previous finding of yokukansan [11], yokukansankachimpihange did not improve “active symptoms”, as shown by the non-significant effects revealed here on subscales A (Paranoid and Delusional Ideation), B (Hallucinations), C (Activity Disturbances), and D (Aggressiveness).

However, there was a positive effect on the subscale of E (Diurnal Rhythm), with a tendency on the subscales of F (Affective Disturbance) and G (Anxiety and Phobias). An improvement in the diurnal rhythm may improve affective disturbance and anxiety. Yokukansankachimpihange is considered to exhibit a mild stabilizing effect on emotion.

Use of Anti-Psychotic Drugs in both Groups

About 35% patients in the donepezil group required the use of anti-psychotics for the treatment of BPSD, especially for “active symptoms.” Taking into consideration the lack of any difference between groups for the pre-treatment subscores of BPSD, and that the donepezil + yokukansankachimpihange did not affect “active symptoms, but had positive effects on the disturbed diurnal rhythm, affective disturbance and anxiety, we consider that the “active symptoms”, which can easily lead physicians to prescribe anti-psychotics might be due to psychological symptoms and that it may not be necessary to undergo treatment with such drugs.

Actually, although the current findings are limited to delusion among the BPSD, we have previously reported that several types of delusion can be due to brain dysfunction as well as psychological symptoms [21], and that a type of delusion can be understood based on cognitive dysfunction [22]. However, in both cases, anti-psychotics were unnecessary.

Limitations

We should mention some methodological issues with the study. First, the design was an observational study, not a RCT. Indeed, it is difficult to prepare a placebo for this drug, since this is a usual drug already used by a routine clinical medicine. This is not a clinical trial. Although the group on drug plus Kampo used less anti-psychotics (Fig. 4), this group also appeared from BEHAVE-AD-FW measures (Table 1) to have more behavioral problems; both of these factors may influence group comparisons. Additionally, the lack of a placebo for the Kampo medicine meant that the patients all knew they were taking it. Second, a possible placebo effect of Kampo medicine was not excluded. Some older people in the community are convinced of the positive effect(s) of herbal medicines. Third, the efficacy of donepezil could not be controlled for in either group. Despite these limitations, we consider that the results can provide some evidence supporting the use of yokukansankachimpihange. A prospective, cross-over design study will be necessary to further clarify these points.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that a combined treatment of yokukansankachimpihange with donepezil has a positive clinical effect on improving behavioral abnormalities. Improvements in the diurnal rhythm may improve affective disturbance and anxiety. Thus, yokukansankachimpihange is considered to have a mild stabilizing effect on emotion. A future study separating Nchimpi from the yokukansankachimpihange is planned for clarifying its effect.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the participants of the study, as well as the staff at the Osaki-Tajiri SKIP Center, especially Dr Takashi Seki. The technical assistance of Ms Keiko Chida and Yuriko Kato are also appreciated.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The article processing charges were funded by the authors.

Authorship

The authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Kenichi Meguro and Satoshi Yamaguchi have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient and from their family members, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Osaki-Tajiri SKIP Center.

Data Availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced digital content

To view enhanced digital content for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.6949052.

References

- 1.Meguro K, Ueda M, Yamaguchi T, et al. Disturbance in daily sleep/wake patterns in patients with cognitive impairment and decreased daily activity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:1176–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meguro K, Ueda M, Kobayashi I, et al. Sleep disturbance in elderly patients with cognitive impairment, decreased daily activity and periventricular white matter lesions. Sleep. 1995;18:109–114. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meguro K, Yamaguchi S, Yamazaki H. Cortical glucose metabolism in psychiatric wandering patients with vascular dementia. Psychiatr Res. 1996;67:71–80. doi: 10.1016/0925-4927(96)02549-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkel SI. Behavioral and psychological signs and symptoms of dementia: a consensus statement on current knowledge and implications for research and treatment. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8(S3):497–500. doi: 10.1017/S1041610297003943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tery L. Behavior and caregiver burden: behavioral problems in patients with Alzheimer disease and its association with caregiver distress. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;4:35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reisberg B. Behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: phenomenology and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48(S5):9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monteiro IM, Boksay I, Auer SR, et al. Addition of a frequency-weighted score to the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer Disease Rating Scale: the BEHAVE-AD-FW: methodology and reliability. Eur Psychiatry. 2001;16(S1):5–24. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(00)00524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meguro K, Meguro M, Tanaka Y, et al. Risperidone is effective for wandering and disturbed sleep/wake patterns in Alzheimer’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatr Neurol. 2004;17:61–67. doi: 10.1177/0891988704264535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin HW, Chung SJ. Drug-induced parkinsonism. J Clin Neurol. 2012;8(1):15–21. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2012.8.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikarashi Y, Mizoguchi K. Neuropharmacological efficacy of the traditional Japanese Kampo medicine yokukansan and its active ingredients. Phramacol Therap. 2016;166:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeyoshi K, Kurita M, Nishino S, Teranishi M, Numata Y, Sato T, Okubo Y. Yokukansan improves behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia by suppressing dopaminergic function. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:641–649. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S99032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyde AJ, May BH, Dong L, et al. Herbal medicine for management of the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31:169–183. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawahata I, Yoshida M, Sun W, et al. Potent activity of nobiletin-rich Citrus reticulata peel extract to facilitate cAMP/PKA/ERK/CREB signaling associated with learning and memory in cultured hippocampal neurons: identification pf the substrates responsible for the pharmacological action. J Neural Transm. 2013;120(10):1397–1409. doi: 10.1007/s00702-013-1025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aizawa R, Kanbayashi T, Saito Y, et al. Effects of Yoku-kan-san-ka-chimpi-hange on the sleep of normal healthy adult subjects. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;56(3):303–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2002.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birks J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;1:5593. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meguro K, Ishii H, Yamaguchi S, et al. Prevalence of dementia and dementing diseases in Japan: the Tajiri Project. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1109–1114. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.7.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folstein FM, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental State” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monteiro IM, Boksay I, Auer SR, et al. Addition of a frequency-weighted score to the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale: the BEHAVE-AD-FW: methodology and reliability. Eur Psychiatr. 2001;16(S1):5–24. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(00)00524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasuya M, Meguro K, Okamura N, et al. Greater responsiveness to donepezil in Alzheimer patients with higher levels of acetylcholinesterase based on attention task scores and a donepezil PET study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26:113–118. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182222bc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakatsuka M, Meguro K, Tsuboi H, et al. Contents of delusional thoughts in Alzheimer’s disease and content-specific brain dysfunction assessed with BEHAVE-AD-FW and SPECT. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(6):939–948. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakatsuka M, Meguro K, Nakamura K, et al. “Residence is not home” is a particular type of delusion that associates with cognitive declines of Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;38:46–54. doi: 10.1159/000357837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.