Abstract

Introduction

Transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR amyloidosis), whether manifesting as familial amyloid polyneuropathy (ATTR-PN) or cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM), is a progressive, debilitating, and often fatal, rare disease requiring significant caregiver support. This study aims to better characterize the burden of disease for ATTR amyloidosis patients and caregivers.

Methods

Patients and caregivers in the USA and Spain were recruited through patient advocacy groups to complete a cross-sectional survey. Assessments included the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey, the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire, the Zarit Burden Interview, pain and symptom measures, health care resource use measures, and caregiving burden measures.

Results

Respondents included 60 ATTR amyloidosis patients and 32 caregivers. Patients registered scores up to two standard deviations below normal for physical health, impairment in quality of life, and reduced work productivity. Patients with liver transplant versus without liver transplant reported better overall outcomes, and those without liver transplant reported a greater impact on physical versus mental health. A high rate of health care utilization in the 3 months prior to the survey was reported by patients. Caregivers reported substantial burden, including poor mental health, work impairment, and much time spent providing care (mean 45.9 h/week). Work productivity was impacted for employed patients and caregivers.

Conclusion

ATTR amyloidosis was associated with high levels of impairment in many domains, including physical health, quality of life, and reduced productivity. Providing care for ATTR amyloidosis patients is associated with a negative impact on the mental health of caregivers. These results highlight the substantial burden of ATTR amyloidosis for patients and caregivers.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01604122.

Funding

Pfizer.

Keywords: Burden of disease, Caregivers, Familial amyloid polyneuropathy, Transthyretin amyloidosis, Transthyretin cardiomyopathy

Introduction

Transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR amyloidosis) is a progressive, debilitating, and often fatal, rare disease induced by amyloid fibril deposits of misfolded transthyretin (TTR) protein in the peripheral nerves and organs [1, 2]. Approximately 100 pathogenic TTR genotypes have been identified [3, 4]. The amino acid substitution of valine to methionine at position 30 (Val30Met) in the TTR protein chain is the most common disease-causing TTR variant [4–6]. This disease has at least two distinct phenotypic manifestations: transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy (ATTR-PN), which primarily affects peripheral nerves, and transthyretin cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM), which primarily affects the heart [1, 2].

In ATTR-PN, symptoms can present as early as the third decade of life, although this varies by region [1]. The main feature of ATTR-PN is progressive sensorimotor and autonomic neuropathy [1]. Typically, sensory neuropathy starts in the lower extremities followed by motor neuropathy within a few years. Autonomic neuropathy quite often accompanies the sensory and motor deficits [7]. ATTR-CM is generally a late-onset disease, with the first cardiac symptoms typically reported by patients over 60 years of age. Symptoms of ATTR-CM are not mutation-type dependent and are typical of heart failure, including exertional dyspnea, peripheral edema, and fatigue [8].

The age at onset, form, and rate of progression of disease vary between patients [1]. Patients with a younger age at onset of disease (< 50 years of age) typically emerge from endemic areas and can experience rapid deterioration with autonomic dysfunction and small-fiber neuropathy [9–12]. Patients with late-onset disease, typically from non-endemic areas, are more likely to have large-fiber neuropathy, fewer autonomic symptoms, and more severe motor and cardiac involvement than those with early-onset disease [9–12].

Liver transplant is a recognized treatment option for patients with ATTR-PN and has been widely used in some countries [13]. However, it is associated with significant risks [14]. Treatment for ATTR-CM is mainly directed at symptom management with the use of diuretics or pacemakers [2], although heart transplant is occasionally performed [15].

Treatments for the symptoms of ATTR amyloidosis include analgesics, antidiarrheal drugs, and drugs to manage orthostatic hypotension. Patients with cardiac involvement can be treated with diuretics for cardiac failure or receive prophylactic pacemaker implantation for severe cardiac conduction disorders [16].

Tafamidis, a small-molecule stabilizer of TTR, has been shown to delay neurologic progression in ATTR-PN [17–22] and has been approved for early-stage ATTR-PN in Europe (in 2011), Japan (2013), and several Latin American countries recently, including Brazil (2016). Other new medicines aimed at slowing ATTR-PN progression are in development, including TTR gene silencers and amyloid fibril disrupters [1, 23]. The non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) diflunisal is a non-specific TTR stabilizer and has shown some promise in slowing ATTR-PN progression [24]; however, it is not approved to treat ATTR-PN, and there are concerns about the long-term safety of NSAIDs.

Little information on the burden of ATTR amyloidosis on patients and caregivers is available. A small qualitative study found that patients with ATTR-PN perceive their disease negatively and experience feelings of fear, bitterness, insecurity, poor self-confidence, dependence on others, melancholy, and grief [25]. To date, no published studies have specifically examined the burden on caregivers of ATTR-PN and ATTR-CM patients. Studies in other neurologic conditions have found that caregivers play an important, often difficult, role in caring for patients and supporting their ability to live and function at home [26]. The objective of this study was to better characterize the burden of disease of ATTR amyloidosis on both patients and their caregivers.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a cross-sectional, non-interventional survey conducted from February to September 2013 in the USA and from November 2013 to May 2014 in Spain (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01604122). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Study Population

Study participants were recruited through patient advocacy groups in the USA and Spain (disease is not endemic in these countries). Eligible patients were between 18 and 85 years of age with diagnosed and symptomatic ATTR-PN and/or ATTR-CM; ATTR-CM was only included in the US population. Only nonpaid caregivers between 18 and 85 years of age were eligible to participate.

Assessments

Surveys were administered to patients and caregivers online in the USA and on paper in Spain either at patient advocacy group offices or at home. Caregivers who were also diagnosed with ATTR amyloidosis could choose to complete either the patient or the caregiver version of the survey. The specific questionnaires administered were chosen to capture important concepts and areas likely to be impacted by disease.

Assessments Completed by Patients and Caregivers

The 12-Item Short Form Health Survey, version 2 (SF-12), is a patient-reported questionnaire that assesses physical and mental health over the previous week. The SF-12 produces eight subscale scores (physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health) and two summary measures (the physical health component summary and the mental health component summary). Higher scores indicate better levels of health.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a 14-item questionnaire developed to assess levels of anxiety and depression of patients for the previous week and is directed towards patients with physical conditions. The HADS includes seven items each for anxiety and depression assessments. Responses range from 0 to 3, with scores summed separately for anxiety and depression items to produce two subscale scores. Lower scores indicate less anxiety or depression.

The EuroQol–5 Dimensions–3 Levels (EQ-5D-3L) questionnaire is a two-part, self-administered generic health status instrument. Patients and caregivers were asked to rate their current health on five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression. Each rating is on a scale of 3 (1 = no problem, 2 = some problem, and 3 = extreme problem). The scores from the five dimensions are used to calculate a single index utility score. Country-specific weights were used to calculate the index score for the USA [27] and Spain [28]. Patients and caregivers also rated their current health state on a visual analog scale for which 100 = best imaginable health and 0 = worst imaginable health.

The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Specific Health Problem (WPAI-SH) assessment is a six-item questionnaire regarding current employment status, hours worked, hours missed from work, degree to which a specified health problem affected work productivity, and regular activities in the past 7 days. Each subscale score is expressed as an impairment percentage; a higher percentage indicates greater impairment.

Health care resource utilization was assessed via questions on a variety of different types of treatment and resources, including outpatient visits to health care providers, hospitalizations, emergency/urgent care visits, symptomatic treatments, mobility aids (canes, wheelchairs), and use of non-traditional resources (acupuncture, nutritional aids).

Assessments Completed by Patients Only

Patients rated their pain (current pain, average pain in the last week, and worst pain in the last week) on an 11-point numeric rating scale wherein 0 = no pain and 10 = severe pain.

The Norfolk Quality of Life Questionnaire–Diabetic Neuropathy (Norfolk QOL-DN) is a 35-item questionnaire that assesses the impact of neuropathy on quality of life (QOL). Scoring yields a total score calculated from five subscale scores: activities of daily living, large fiber neuropathy/physical functioning, small fiber neuropathy, autonomic neuropathy, and symptoms. Lower scores indicate better QOL.

The Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) is a 23-item patient-completed questionnaire that assesses health status and health-related QOL in patients with heart failure [29]. The KCCQ was completed only by patients who reported having ATTR-CM (or caregivers who report having ATTR-CM). Patients are asked to assess their ability to perform activities of daily living, frequency and severity of symptoms, the impact of these symptoms, and health-related QOL. Scores are transformed to a 0–100 range; higher scores indicate better health status.

Assessments Completed by Caregivers Only

The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) is a 22-item questionnaire completed by caregivers to assess personal and role strain associated with caregiving. Lower scores indicate lower burden. Additional questions probed caregiver burdens, such as the number of hours spent caring for the ATTR amyloidosis patient, time lost from work due to caregiving, out-of-pocket costs, and overall satisfaction with life.

Statistical Analysis

Basic descriptive statistics (e.g., n, mean, standard deviation [SD], and range) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for means were calculated for continuous variables. Percentages, frequencies, and 95% CIs for proportions were calculated for categorical variables.

Analyses were performed to compare results by country (USA versus Spain). Patient data were also analyzed by type of ATTR amyloidosis and by liver transplant status. As some caregivers also had ATTR amyloidosis, results for caregivers were further summarized by disease status. No effort was made to link caregivers to individual patients.

Results

Patients

Demographics and Baseline Disease Characteristics

Respondents included 60 ATTR amyloidosis patients (n = 44 in the USA; n = 16 in Spain) with ATTR-PN and/or ATTR-CM and 32 caregivers (n = 24 in the USA; n = 8 in Spain). The majority of patients were male and patients in the USA tended to be older than those in Spain (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics by country

| USA n = 44 |

Spain n = 16 |

Total N = 60 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 61.7 (10.0) | 49.3 (12.5) | 58.4 (12.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 35 (79.5) | 12 (75.0) | 47 (78.3) |

| Not currently employed, n (%) | 28 (63.6) | 11 (68.8) | 39 (65.0) |

| Unemployed due to ATTR amyloidosis, n (%)a | 20 (71.4) | 5 (45.5) | 25 (64.1) |

| Disease characteristics | |||

| Disease duration, years, mean (SD) | 5.5 (3.4) | 8.2 (4.8) | 6.2 (4.0) |

| Age at onset, years, mean (SD)b | 56.3 (10) | 41.1 (14) | 52.2 (13) |

| Liver transplant, n (%) | 17 (38.6) | 14 (87.5) | 31 (51.7) |

| Family ATTR amyloidosis history, n (%) | 38 (86.4) | 13 (81.3) | 51 (85.0) |

| Family member with ATTR amyloidosis, n (%) | |||

| Mother | 13 (29.5) | 3 (18.8) | 16 (26.7) |

| Father | 17 (38.6) | 7 (43.8) | 24 (40.0) |

| Grandmother | 4 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (6.7) |

| Grandfather | 7 (15.9) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (11.7) |

| Brother | 14 (31.8) | 4 (25.0) | 18 (30.0) |

| Sister | 7 (15.9) | 2 (12.5) | 9 (15.0) |

| Cousin | 9 (20.5) | 3 (18.8) | 12 (20.0) |

| Aunt | 9 (20.5) | 4 (25.0) | 13 (21.7) |

| Uncle | 13 (29.5) | 3 (18.8) | 16 (26.7) |

| Otherc | 5 (11.4) | 1 (6.3) | 6 (10.0) |

| Mutation type, n (%) | |||

| Val30Met | 5 (11.4) | 13 (81.3) | 18 (30.0) |

| Wild-type ATTR | 1 (2.3) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (3.3) |

| Phe64Leu | 4 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (6.7) |

| Ser77Tyr | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.0) |

| Thr60Ala | 11 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (18.3) |

| Otherd | 5 (11.4) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (8.3) |

| Not sure/don’t know | 4 (9.1) | 2 (12.5) | 6 (10.0) |

| Missing | 11 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (18.3) |

SD standard deviation

aLimited to patients who responded that they were unemployed

bAge at disease onset equals age at time of survey minus the number of years experiencing symptoms

c“Other” family member category included 8 uncles and 2 aunts; daughter; multiple in each category except for father and grandmother; niece; son; 2 brothers

dOther genetic type: ARG 50, asp18Glu, TTR amyloidosis t49A; Ser84IL (IN-Swiss Kindred); V 32 A

Overall, patients were, on average, 52.2 ± 12.7 years old at disease onset (age at disease onset equals mean age at time of survey minus the mean number of years experiencing symptoms) and had mean disease duration of 6.2 ± 4.0 years. Disease onset occurred later in life in US patients than in Spanish patients. The majority of patients in each country had a family history of ATTR amyloidosis. While most patients in Spain had the Val30Met mutation, it was uncommon in the US patients. Spanish patients were also more likely to have undergone liver transplant than US patients (Table 1).

In both countries, disease severity varied among patients: 25.0% (n = 15) of patients reported that they were able to walk normally, 26.7% (n = 16) reported having some problems with their feet but being able to walk without difficulty, and 23.3% (n = 14) reported having some difficulty walking but being able to walk without assistance. Six (10%) patients reported that they required one cane or crutch to walk, while nine (15%) patients indicated they that needed two canes/crutches or a walker to help them walk; this latter group included eight (18.2%) patients in the USA and one (6.3%) patient from Spain.

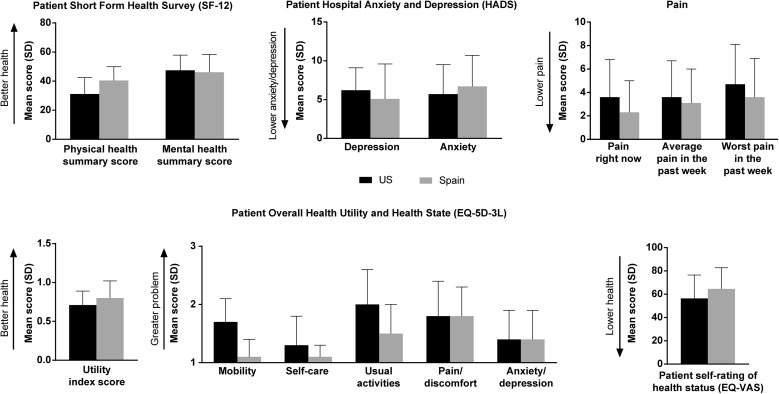

Physical and Mental Health

The mean (SD) SF-12 physical health component summary score for all ATTR amyloidosis patients was 33.6 ± 11.5, which was almost two standard deviations lower than the population norm of 50 [30]. Patients in Spain had better physical health summary scores compared with patients in the USA; mental health summary scores were similar in both countries (Fig. 1). The physical health summary score was lower for patients with both ATTR-PN and ATTR-CM than for patients with either disease alone (Table 2). There was no difference on either physical or mental health summary scores for patients with or without liver transplant (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Patient health. EQ-5D-3L EuroQol–5 Dimensions–3 Levels questionnaire, EQ-VAS EuroQol visual analog scale, SD standard deviation

Table 2.

Patient health in the USA by ATTR amyloidosis type

| Patients with ATTR-PN | Patients with ATTR-CM | Patients with both ATTR-PN and ATTR-CM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SF-12 Health Survey scorea, n | 27 | 6 | 11 |

| Physical Health Summary | 34.4 (11.7) | 32.0 (9.5) | 23.4 (7.3) |

| Mental Health Summary | 45.8 (10.1) | 54.2 (8.6) | 47.2 (11.2) |

| HADS score, n | 27 | 6 | 11 |

| Depression subscale | 6.2 (3.2) | 6.0 (3.5) | 6.1 (2.0) |

| Anxiety subscale | 6.1 (4.1) | 4.2 (4.1) | 5.5 (3.3) |

| Pain, n | 27 | 6 | 11 |

| Pain, right now | 3.6 (3.2) | 0.8 (2.0) | 2.6 (1.4) |

| Average pain, past week | 3.6 (3.1) | 0.8 (1.6) | 3.0 (1.6) |

| Worst pain, past week | 4.7 (3.4) | 1.2 (1.8) | 5.0 (2.8) |

| EQ-5D-3L health survey, n | 27 | 6 | 11 |

| Mobility | 1.7 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.3) |

| Self-care | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.0) (NA) | 1.5 (0.7) |

| Usual activities | 2.0 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.8) | 2.3 (0.6) |

| Pain/discomfort | 1.8 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.4) |

| Anxiety/depression | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.5) |

| Utility index score | 0.71 (0.2) | 0.83 (0.2) | 0.66 (0.2) |

| Overall health status rating | 59.6 (20.7) | 63.2 (12.7) | 46.2 (19.8) |

| Kansas City cardiomyopathy score, n | 6 | 11 | 17 |

| Physical limitation | 61.1 (26.1) | 31.1 (25.9) | 41.7 (29.2) |

| Symptom stability | 54.2 (10.2) | 45.5 (10.1) | 48.5 (10.7) |

| Symptom frequency | 65.6 (21.9) | 37.9 (21.6) | 47.7 (25.1) |

| Symptom burden | 68.1 (23.8) | 41.7 (20.1) | 51.0 (24.5) |

| Total symptom | 66.8 (22.5) | 39.8 (19.3) | 49.3 (23.8) |

| Self-efficacy | 81.3 (20.5) | 77.3 (22.2) | 78.7 (21.1) |

| Quality of life | 57.0 (23.8) | 46.2 (15.1) | 50.0 (18.6) |

| Social limitation | 44.8 (27.8) | 24.6 (21.4) | 31.8 (25.0) |

| Overall summary | 57.4 (18.9) | 35.4 (16.5) | 43.2 (20.0) |

| Clinical summary | 64.0 (23.8) | 35.4 (20.3) | 45.5 (25.2) |

All assessment scores are mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise indicated

EQ-5D-3L EuroQol–5 Dimensions–3 Levels questionnaire, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, NA not available, SF-12 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (version 2)

aThe 1-week recall version of the SF-12 form was used in Spain and the 4-week recall version was used in the USA

Table 3.

Patient health by liver transplant status

| Assessment | Patients with liver transplant | Patients without liver transplant |

|---|---|---|

| SF-12 (version 2) Health Survey score, n | 31 | 29 |

| Physical Health Summary | 34.5 (11.6) | 32.6 (11.6) |

| Mental Health Summary | 47.8 (11.5) | 46.2 (10.1) |

| Pain, n | 24 | 19 |

| Pain, right now, mean | 2.1 (2.6) | 4.5 (3.2) |

| Average pain, past week | 2.7 (2.8) | 4.4 (3.1) |

| Worst pain, past week | 3.6 (3.2) | 5.3 (3.5) |

| EQ-5D-3L health survey, n | 24 | 19 |

| Mobility | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.6 (0.5) |

| Self-care | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.5) |

| Usual activities | 1.6 (0.6) | 2.1 (0.4) |

| Pain/discomfort | 1.7 (0.6) | 2.1 (0.6) |

| Anxiety/depression | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.5) |

| Utility index score | 0.80 (0.2) | 0.66 (0.2) |

| Visual analog scale | 64.5 (19.5) | 57.6 (19.8) |

EQ-5D-3L EuroQol–5 Dimensions–3 Levels questionnaire, SF-12 12-Item Short Form Health Survey

On the HADS depression and anxiety scales, patients scored 6.1 ± 2.0 and 5.5 ± 3.3, respectively, which was within the normal range (0–7) [31]. Patients in the USA and Spain reported similar scores (Fig. 1), as did subgroups based on diagnosis (Table 2).

On the pain scales, mean scores were 3.1 ± 3.1 (range 0–10) for current pain, 3.4 ± 3.0 (range 0–10) for average pain in the past week, and 4.3 ± 3.4 (range 0–10) for worst pain in the past week. Scores were generally higher in US patients compared with Spanish patients (Fig. 1) and in patients with ATTR-PN, or both conditions, compared with ATTR-CM alone (Table 2). Pain ratings were higher in patients who did not have liver transplants than in patients who had undergone liver transplant (Table 3).

On the EQ-5D-3L, US patients compared with those in Spain, respectively, reported greater impairments in mobility (1.7 ± 0.4 versus 1.1 ± 0.3), self-care (1.3 ± 0.5 versus 1.1 ± 0.2), and usual activities (2.0 ± 0.6 versus 1.5 ± 0.5), where 1 = no problem and 2 = some problem. However, patients from both countries reported similar degrees of impairment in pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Scores on the self-rating of health status were comparable between the two countries. Spanish patients had slightly better scores on the utility index score compared with US patients (Fig. 1). When patients were analyzed by ATTR amyloidosis type, patients with both ATTR-PN and ATTR-CM had lower scores on the self-rating of health status visual analog scale than patients with either disease alone (Table 2). ATTR-PN patients who had undergone liver transplant had a higher (better) mean utility index score than ATTR-PN patients without liver transplant, but the scores were similar on the visual analog scale (Table 3).

The KCCQ was only administered to patients with cardiomyopathy, either ATTR-CM alone (n = 6) or both ATTR-CM and ATTR-PN (n = 11) in the USA only. Across both groups, the overall mean score was 43.2 ± 20.0, which roughly aligns with the New York Heart Association class IV criteria of “severe limitations; experiences symptoms even while at rest; mostly bedbound patients” [32]. Overall scores were lower (worse) for patients with ATTR-CM alone than for those with both types of ATTR amyloidosis (Table 2).

Health Care and Resource Utilization

Most patients (80%) reported outpatient visits to health care providers in the 3 months prior to taking the survey. During this time, patients also reported hospital emergency room visits (21.7%), hospitalizations (15.0%), and required the use of professional home health care services (6.7%). Health care utilization was similar between US and Spanish patients.

Almost half of all patients (48.3%) reported that they were unable to complete typical household chores in the months prior to taking the survey. These patients reported that they were unable to take care of typical chores at home for a mean of 33.7 ± 36.5 days out of the past 3 months. On average, patients in the USA reported being unable to do household chores on more days (mean 40.2 ± 37.5 days) compared with patients in Spain (mean 5.2 ± 5.6 days).

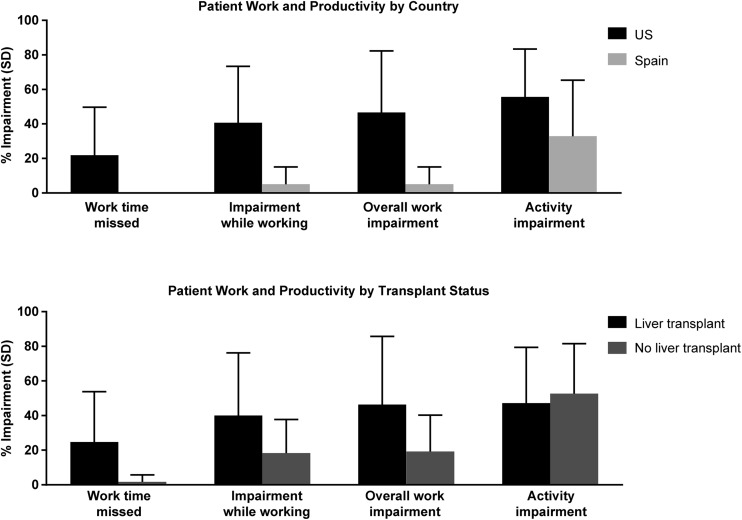

Work Productivity

The 33.3% of patients who were employed (36.4% in the USA and 25.0% in Spain) completed the WPAI-SH questionnaire. In general, US patients with ATTR amyloidosis reported greater impairment in work and productivity compared with patients in Spain (Fig. 2). US patients reported missing 21.9 ± 27.8% of work time due to ATTR amyloidosis, whereas Spanish patients reported that no work time was missed. The mean percentage of impairment while working due to ATTR amyloidosis was reported as 40.7 ± 32.7% for US patients compared with 5.0 ± 10.0% for Spanish patients. Similarly, the mean percentage overall work impairment due to ATTR amyloidosis was 46.6 ± 35.7 and 5.0 ± 10.0% for US patients and Spanish patients, respectively. Patients in the USA had a higher percentage of non-work-related activity impairment due to ATTR amyloidosis than patients in Spain (55.6 ± 27.8 and 32.9 ± 32.4%, respectively; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Patient work productivity by country and transplant status. SD standard deviation

Work and productivity impairment was also greater in US patients who had liver transplants compared with those who did not; all Spanish patients who reported working also reported having had liver transplants. Non-work-related activity impairment was similar between transplant and non-transplant patients overall (Fig. 2). Patients with both ATTR-PN and ATTR-CM missed a mean of 50.1 ± 35.6% of work as a result of their illness, compared with 10.6 ± 14.1% of patients with ATTR-PN alone. Overall work impairment was 76.3 ± 37.7% in patients with both ATTR-PN and ATTR-CM, and 34.7 ± 28.5% in ATTR-PN alone. Patients with both ATTR-PN and ATTR-CM had higher mean percentage activity impairment due to ATTR amyloidosis (73.6 ± 20.1%) compared with those with ATTR-PN alone (47.5 ± 27.7%) or ATTR-CM alone (55.0 ± 28.8%).

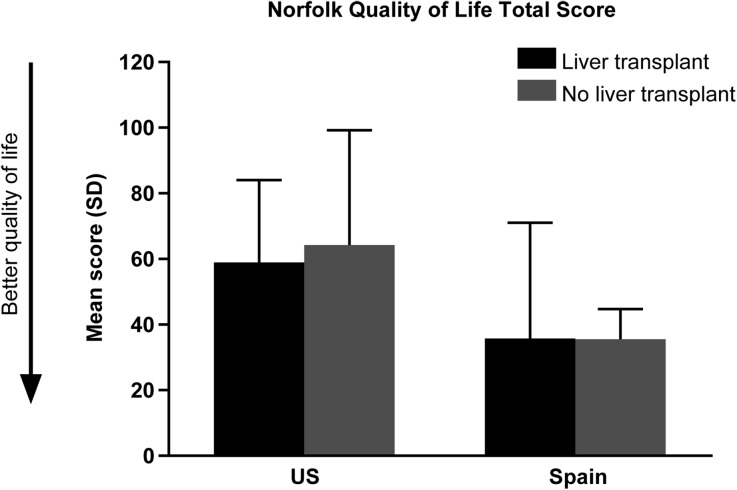

Quality of Life

Norfolk QOL-DN mean total score was 54.6 ± 32.8 for all patients. Patients in the USA reported a poorer QOL total (SD) score compared with patients in Spain: 61.8 ± 30.5 and 35.8 ± 32.3, respectively. There was little difference in Norfolk QOL-DN measures for patients with or without liver transplant in either country (Fig. 3). The scores reported for the majority of patients in the current study are consistent with ATTR-PN patients with stage 1 or 2 disease (stage 1 = independent ambulation, stage 2 = assistance required to walk, stage 3 = wheelchair bound or bedridden) [33].

Fig. 3.

Patient quality of life. SD standard deviation

Caregivers

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

Caregivers of ATTR amyloidosis patients were primarily female (68.8%) and of similar ages in both the USA (57.0 ± 13.1 years) and Spain (52.8 ± 12.1 years). Of those who provided data, the majority of caregivers in both countries were spouses/partners of the patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Caregiver demographics characteristics by country

| USA | Spain | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregivers with ATTR amyloidosis n = 13 |

Caregivers without ATTR amyloidosis n = 11 |

Caregivers without ATTR amyloidosis n = 8 |

N = 32 | |

| Caregiver characteristics | ||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 60.1 (12.9) | 52.9 (12.9) | 52.8 (12.1) | 55.9 (12.8) |

| Female, n (%) | 6 (46.2) | 9 (81.8) | 7 (87.5) | 22 (68.8) |

| Not currently employed, n (%) | 10 (76.9) | 4 (36.4) | 5 (62.5) | 19 (59.4) |

| Relationship to the ATTR amyloidosis patient, n (%) | ||||

| Spouse/partner | 9 (75.0) | 6 (66.7) | 6 (75.0) | 21 (72.4) |

| Mother | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (10.3) |

| Father | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) |

| Child | 1 (8.3) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.3) |

| Other | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) |

| Age at disease onset, years, mean (SD)a | 58.2 (11.3) | – | – | – |

| Disease duration, years, mean (SD) | 5.1 (2.7) | – | – | – |

SD standard deviation

aAge at disease onset = age at time of survey minus the number of years experiencing symptoms

Of the 32 caregivers, 13 (40.6%) in the USA reported also having ATTR amyloidosis (caregivers self-reported as symptomatic). None of the Spanish caregivers reported having ATTR amyloidosis (Table 4). Of the 13 US caregivers reported to also have symptomatic ATTR amyloidosis, 9 reported that they also had genetic testing done. Seven of the 13 caregivers reported that they were aware of a family history of ATTR amyloidosis. Caregivers with ATTR amyloidosis were older on average than those without ATTR amyloidosis and more likely to be unable to work as a result of disability (60% versus 25%).

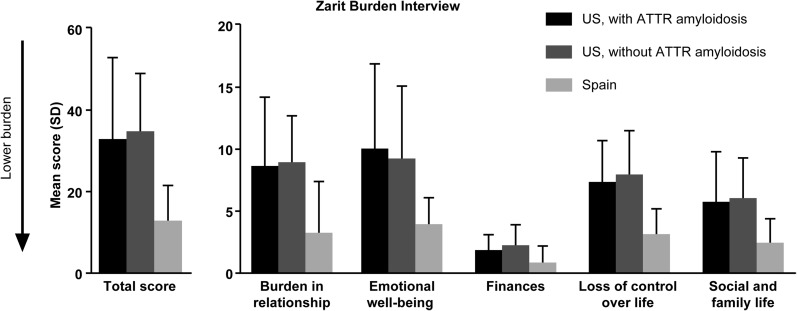

Burden

Caregivers spent a mean of 45.9 ± 50.4 h (USA 46.8 ± 49.8 h, Spain 40.8 ± 61.5 h) per week caring for ATTR amyloidosis patients. As reported on the ZBI, US caregivers had overall greater burden compared with Spanish caregivers (Fig. 4). Specifically, US versus Spanish caregivers, respectively, reported greater burden in the relationship with the patient (9.0 ± 4.6 versus 3.4 ± 4.0), lower emotional well-being (9.9 ± 6.1 versus 4.1 ± 2.0), worse social and family life (6.1 ± 3.5 versus 2.6 ± 1.8), and greater loss of control over life (7.8 ± 3.2 versus 3.3 ± 1.9). Scores on the ZBI were comparable between caregivers with and without ATTR amyloidosis. Financial burden due to caregiving was reported by caregivers in both countries.

Fig. 4.

Caregiver burden. SD standard deviation

Physical and Mental Health

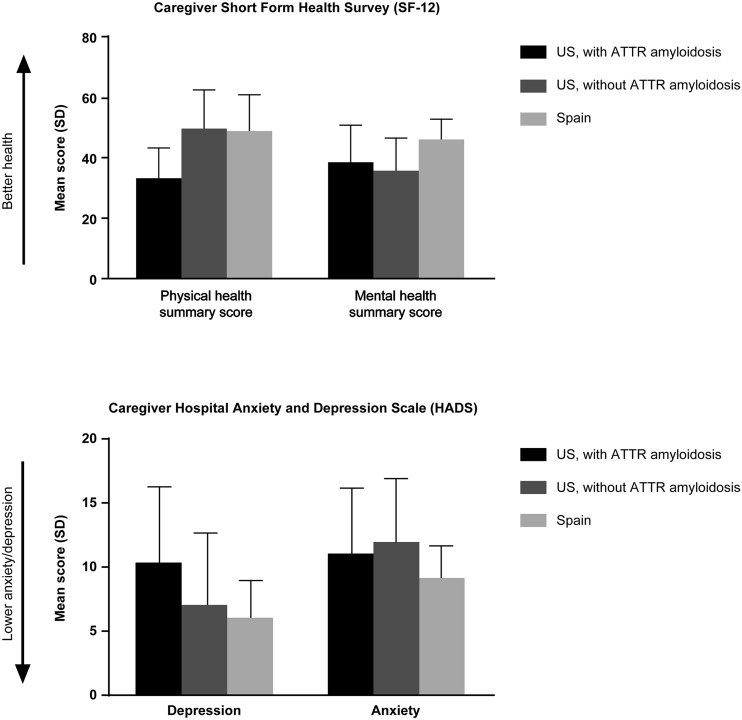

Caregivers in both the USA and Spain reported similar poor physical and mental health scores on the SF-12 questionnaire (Fig. 5). US caregivers with ATTR amyloidosis had worse physical health summary scores (33.0 ± 10.0) compared with US caregivers without ATTR amyloidosis (49.4 ± 12.8) or Spanish caregivers (48.6 ± 12.0). This score for US caregivers with ATTR amyloidosis was comparable to the score for all ATTR amyloidosis patients (33.6 ± 11.5).

Fig. 5.

Caregiver health. SD standard deviation

Scores on the HADS depression scale were worse for US caregivers (8.9 ± 5.9) compared with Spanish caregivers (6.0 ± 2.9; Fig. 5). Overall, the mean score for caregivers in Spain was within the normal range (0–7), whereas scores for US caregivers fell within the mild range (8–10). On average, US caregivers with ATTR amyloidosis reported moderate depression (10.3 ± 5.9), whereas US caregivers without ATTR amyloidosis were within the normal range (7.0 ± 5.6; Fig. 5).

On average, Spanish caregivers reported less anxiety on HADS (9.1 ± 2.5) compared with those in the USA (11.4 ± 5.0; Fig. 5). The mean anxiety scores for US caregivers, both those with and without ATTR amyloidosis, fell within the moderate range (11–14), whereas the score for caregivers in Spain (all without ATTR amyloidosis) was in the mild range (8–10).

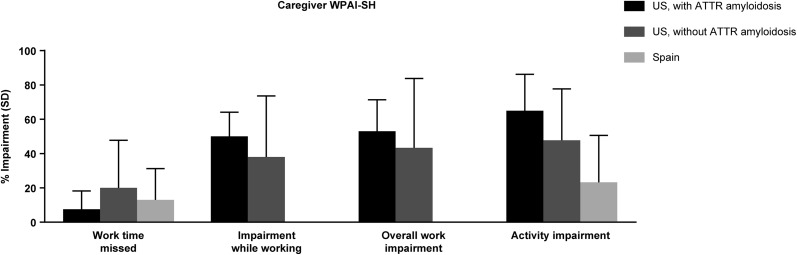

Work Productivity

The 11 caregivers who were employed (8 in the US, 3 in Spain) completed the WPAI-SH questionnaire. Overall, US caregivers reported lower productivity compared with Spanish caregivers (Fig. 6). US caregivers with ATTR amyloidosis reported the lowest percentage of work time missed due to caregiving (7.5 ± 10.7%) compared with those without ATTR amyloidosis (20.0 ± 27.8%) or caregivers from Spain (13.0 ± 18.3%). US caregivers with ATTR amyloidosis reported the highest mean percentage activity impairment (65.0 ± 21.2%) compared with US caregivers without ATTR amyloidosis (47.8 ± 29.9%) or Spanish caregivers (23.3 ± 27.3%; Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Caregiver work productivity. SD standard deviation, WPAI-SH Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Specific Health questionnaire

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive study of the disease burden associated with ATTR amyloidosis in both patients and their caregivers. Results in this sample point to negative impact across several domains, including health and work productivity, for both patients and their caregivers. For patients, ATTR amyloidosis impacts physical health more than mental health. Caregivers reported the greatest impacts in mental health, though physical health impacts were also observed.

Patient Disease Burden

This study showed a pervasive impact of ATTR amyloidosis on patients and their use of health care resources. In the 3 months prior to participation, 21.7% of patients surveyed visited an emergency room, 15% were hospitalized, and 80% visited an outpatient health care provider. Physical functioning was dramatically affected, with an average score on the SF-12 nearly two standard deviations below the US population norm. Many patients reported experiencing pain; on a 0–10 pain scale, worst pain in the past week was a 4.3 on average (range 0–10), and patients had a pain level of 3.4 on average (range 0–10). Despite these substantial physical impacts, patient-reported mental health functioning was close to normal levels. Substantial impact on work was reported by US patients, who missed an average of 21.9% of work the week before the survey as a result of ATTR amyloidosis (range 0–79%). While working, 40.7% of their activity was impaired. Overall work impairment and activity impairment were reported as 46.6% and 55.6%, respectively, for US patients. Spanish patients reported far less impact on work, but activities were impaired for this group at 32.9%. Overall, 48.3% reported being unable to complete typical household chores, and many patients reported impairments in mobility, self-care, and usual activities.

The overall burden of illness for patients with ATTR amyloidosis appears to be predominantly influenced by liver transplant status. On the basis of the EQ-5D-3L scores, patients who reported having undergone a liver transplant (i.e., the majority of this Spanish study population) had better health-related QOL. This is likely because the transplant is typically done early in the disease, before patients have lost a great deal of functioning. However, greater impairment in work productivity was also reported by those who had liver transplants. The demands of the transplant, including the need to take immunosuppressants, may have a lasting impact on work. Though liver transplant status appears to be a major differentiator for QOL between patients in the USA and Spain, it is also worth noting that US patients in this sample were also older than the Spain patients (61.7 versus 49.3 years).

There was a much lower proportion of patients in the USA (38.6%) who had liver transplants compared with patients in Spain (87.5%). This imbalance between the two countries may reflect sampling bias or real differences in populations or local clinical practice. In countries where the disease is not endemic, such as the USA, diagnosis may be delayed, and thus patients may tend to be more severely ill when first diagnosed and may not be suitable candidates for liver transplant.

As assessed by the Norfolk QOL-DN, QOL associated with neuropathy symptoms was worse for US patients compared with Spanish patients.

Caregiver Burden

Caregivers, many of whom had spent several years providing care, were on average spending more than the equivalent time of a full-time job providing care every week. Spanish caregivers had, on average, been providing care about twice as long as caregivers in the USA (6.8 ± 5.4 versus 3.3 ± 2.7 years, respectively). This may be due to Spanish patients being diagnosed at an earlier age, on average, and living with the disease longer.

US caregivers without ATTR amyloidosis reported poorer mental health than physical health (the reverse of the pattern seen in ATTR amyloidosis patients), whereas caregivers in Spain had more comparable mental and physical health scores. US caregivers reported symptom levels consistent with mild depression and moderate anxiety, and caregivers in Spain reported mild levels of anxiety. The level of burden reported by US caregivers of ATTR amyloidosis patients was similar to that reported by US caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (ZBI scores, 34.3 ± 16.7 and 30.6, respectively) [34]; Spanish caregivers reported less burden than US caregivers of ATTR amyloidosis patients (ZBI score, 13.3 ± 8.2).

Limitations

The survey sample was small, and all respondents were recruited through patient advocacy groups. The number of participants in the study is low primarily because of the rarity of ATTR amyloidosis, especially given that Spain and the USA are not countries where the disease is considered endemic. As a result, the generalizability of these findings may be limited. In anticipation of this limitation, this study used well-established instruments with norms where possible, which allowed inferences about our findings on those measures relative to the general population. The amount of missing data (< 10%) was consistent with surveys of this nature. As a result of the survey administration mode, participation was limited to patients who have maintained use of their upper limbs, were able to write or type, and, for Spanish patients, who could travel to the clinic. Though disease diagnosis was not verified by a physician, study participants had relationships with patient advocacy groups, so it is expected that they were patients diagnosed with the disease.

Conclusions

These results highlight the substantial burden of ATTR amyloidosis for patients and their caregivers. The impact of this disease is mainly on physical health, quality of life, and work productivity for patients, whereas mental health and productivity are more severely affected in caregivers. Treatment options that move beyond symptomatic management to modification of disease progression and maintenance of psychosocial functioning may reduce the impact on patients and their reliance on their caregivers, thus alleviating the substantial disease burden.

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients and caregivers who participated in this study.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Pfizer which also funded the journal’s article processing charges.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Mary Kunjappu, Ph.D., and Charles Cheng, MS, of Engage Scientific Solutions and was funded by Pfizer.

Authorship

All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article and have given their approval for this version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentation

This paper was presented in part at the International Society of Amyloidosis—XV International Symposium on Amyloidosis (ISA), July 3–7, 2016, Uppsala, Sweden.

Disclosures

Michelle Stewart is a full-time employees of Pfizer and hold stock and/or stock options. Jane Loftus is a full-time employees of Pfizer and hold stock and/or stock options. Jose Alvir is a full-time employee of Pfizer and hold stock and/or stock options. Michael Cicchetti is an employee of ExecuPharm, a PAREXEL company, and is a paid consultant to Pfizer in connection with the development of this manuscript. Shannon Shaffer is a full-time employees of Evidera who worked as paid contractors to Pfizer for study contributions and development of the manuscript. Brian Murphy is a full-time employee of Evidera who worked as a paid contractor to Pfizer for study contributions and development of the manuscript. William R. Lenderking is a full-time employee of Evidera who worked as paid contractor to Pfizer for study contributions and development of the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability

Pfizer provides secure access to anonymized patient-level data to qualified researchers in response to scientifically valid research proposals. Further details can be found at http://www.pfizer.com/research/clinical_trials/trial_data_and_results/data_requests.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced digital content

To view enhanced digital content for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.6815351.

References

- 1.Plante-Bordeneuve V. Update in the diagnosis and management of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Neurol. 2014;261:1227–1233. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7373-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruberg FL, Berk JL. Transthyretin (TTR) cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2012;126:1286–1300. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.078915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connors LH, Lim A, Prokaeva T, Roskens VA, Costello CE. Tabulation of human transthyretin (TTR) variants, 2003. Amyloid. 2003;10:160–184. doi: 10.3109/13506120308998998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson MD, Kincaid JC. The molecular biology and clinical features of amyloid neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36:411–423. doi: 10.1002/mus.20821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coelho T, Maurer MS, Suhr OB. THAOS—The Transthyretin Amyloidosis Outcomes Survey: initial report on clinical manifestations in patients with hereditary and wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:63–76. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.754348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowczenio DM, Noor I, Gillmore JD, et al. Online registry for mutations in hereditary amyloidosis including nomenclature recommendations. Hum Mutat. 2014;35:E2403–E2412. doi: 10.1002/humu.22619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sekijima Y, Yazaki M, Oguchi K, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in posttransplant patients with hereditary ATTR amyloidosis. Neurology. 2016;87:773–781. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rapezzi C, Quarta CC, Riva L, et al. Transthyretin-related amyloidoses and the heart: a clinical overview. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:398–408. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plante-Bordeneuve V, Said G. Familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:1086–1097. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koike H, Misu K, Ikeda S, et al. Type I (transthyretin Met30) familial amyloid polyneuropathy in Japan: early- vs late-onset form. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1771–1776. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koike H, Tanaka F, Hashimoto R, et al. Natural history of transthyretin Val30Met familial amyloid polyneuropathy: analysis of late-onset cases from non-endemic areas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:152–158. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conceicao I, De Carvalho M. Clinical variability in type I familial amyloid polyneuropathy (Val30Met): comparison between late- and early-onset cases in Portugal. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35:116–118. doi: 10.1002/mus.20644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Familial Amyloidotic Polyneuropathy World Transplant Registry. Reporting centers and number of transplants performed (Dec 31, 2017). 2017. http://www.fapwtr.org/ram_fap.htm. Accessed 20 June 2018.

- 14.Ericzon BG, Wilczek HE, Larsson M, et al. Liver transplantation for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis: after 20 years still the best therapeutic alternative? Transplantation. 2015;99:1847–1854. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banypersad SM, Moon JC, Whelan C, Hawkins PN, Wechalekar AD. Updates in cardiac amyloidosis: a review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e000364. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ando Y, Coelho T, Berk JL, et al. Guideline of transthyretin-related hereditary amyloidosis for clinicians. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:31. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ando Y, Sekijima Y, Obayashi K, et al. Effects of tafamidis treatment on transthyretin (TTR) stabilization, efficacy, and safety in Japanese patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy (TTR-FAP) with Val30Met and non-Val30Met: a phase III, open-label study. J Neurol Sci. 2016;362:266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barroso FA, Judge DP, Ebede B, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of tafamidis for the treatment of hereditary transthyretin amyloid polyneuropathy: results up to 6 years. Amyloid. 2017;24:194–204. doi: 10.1080/13506129.2017.1357545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coelho T, Maia LF, da Silva AM, et al. Long-term effects of tafamidis for the treatment of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Neurol. 2013;260:2802–2814. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7051-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coelho T, Maia LF, Martins da Silva A, et al. Tafamidis for transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology. 2012;79:785–792. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182661eb1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coelho T, Merlini G, Bulawa CE, et al. Mechanism of action and clinical application of tafamidis in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. Neurol Ther. 2016;5:1–25. doi: 10.1007/s40120-016-0040-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merlini G, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Judge DP, et al. Effects of tafamidis on transthyretin stabilization and clinical outcomes in patients with non-Val30Met transthyretin amyloidosis. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2013;6:1011–1020. doi: 10.1007/s12265-013-9512-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams D, Cauquil C, Labeyrie C, Beaudonnet G, Algalarrondo V, Theaudin M. TTR kinetic stabilizers and TTR gene silencing: a new era in therapy for familial amyloidotic polyneuropathies. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;17:791–802. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2016.1145664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berk JL, Suhr OB, Obici L, et al. Repurposing diflunisal for familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2658–2667. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.283815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jonsèn E, Athlin E, Suhr O. Familial amyloidotic patients’ experience of the disease and of liver transplantation. J Adv Nurs. 1998;27:52–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaskin J, Gomes J, Darshan S, Krewski D. Burden of neurological conditions in Canada. Neurotoxicology. 2017;61:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care. 2005;43:203–220. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szende AOM, Devlin N. EQ-5D value sets: inventory, comparative review and user guide. Dordrecht: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snaith RP, Zigmond AS. The hospital anxiety and depression scale, with the irritability-depression-anxiety scale and the Leeds situational anxiety scale: manual. London: GL Assessment; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spertus JA, Eagle KA, Krumholz HM, Mitchell KR, Normand SL. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association methodology for the selection and creation of performance measures for quantifying the quality of cardiovascular care. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1147–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vinik EJ, Vinik AI, Paulson JF, et al. Norfolk QOL-DN: validation of a patient reported outcome measure in transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2014;19:104–114. doi: 10.1111/jns5.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergvall N, Brinck P, Eek D, et al. Relative importance of patient disease indicators on informal care and caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23:73–85. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210000785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Pfizer provides secure access to anonymized patient-level data to qualified researchers in response to scientifically valid research proposals. Further details can be found at http://www.pfizer.com/research/clinical_trials/trial_data_and_results/data_requests.