Abstract

To date, gene-environment (GxE) interaction studies in depression have been limited to hypothesis-based candidate genes, since genome-wide (GWAS)-based GxE interaction studies would require enormous datasets with genetics, environmental, and clinical variables. We used a novel, cross-species and cross-tissues “omics” approach to identify genes predicting depression in response to stress in GxE interactions. We integrated the transcriptome and miRNome profiles from the hippocampus of adult rats exposed to prenatal stress (PNS) with transcriptome data obtained from blood mRNA of adult humans exposed to early life trauma, using a stringent statistical analyses pathway. Network analysis of the integrated gene lists identified the Forkhead box protein O1 (FoxO1), Alpha-2-Macroglobulin (A2M), and Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 (TGF-β1) as candidates to be tested for GxE interactions, in two GWAS samples of adults either with a range of childhood traumatic experiences (Grady Study Project, Atlanta, USA) or with separation from parents in childhood only (Helsinki Birth Cohort Study, Finland). After correction for multiple testing, a meta-analysis across both samples confirmed six FoxO1 SNPs showing significant GxE interactions with early life emotional stress in predicting depressive symptoms. Moreover, in vitro experiments in a human hippocampal progenitor cell line confirmed a functional role of FoxO1 in stress responsivity. In secondary analyses, A2M and TGF-β1 showed significant GxE interactions with emotional, physical, and sexual abuse in the Grady Study. We therefore provide a successful ‘hypothesis-free’ approach for the identification and prioritization of candidate genes for GxE interaction studies that can be investigated in GWAS datasets.

Introduction

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) has a well-established genetic contribution, although with a modest (30–40%) heritability [1]. However, we have so far failed to identify vulnerability genes for this disorder. Indeed, while genome wide association studies (GWAS) have identified main genetic effects for schizophrenia [2], autism [3], and bipolar disorder [4], even very large GWAS meta-analyses have failed to identify genome-wide significant associations in depression [5, 6]. Only recently, and using enormous datasets from more than 75 thousand individuals with depression and 200 thousand healthy subjects, 15 genome-wide significant loci for MDD have been identified [7]. One of the potential reasons behind this weak genetic effect is the fact that individual genotypic variations may increase the risk of depression only in the presence of exposure to life stressors and other adverse environmental circumstances, a phenomenon named as ‘gene-environment (GxE) interaction’ [8]. Indeed, environmental factors, and in particular exposure to adversities early in life, have been consistently implicated in the pathophysiology of depression [9]. For example, in a large study conducted by the Center of Disease Control with over 9000 participants, Chapman et al. [10] reported a dose-response relationship between the severity of experienced childhood adversities and the lifetime presence of depressive episodes or chronic depression. However, despite the epidemiological and clinical evidence confirming these effects, there is substantial variability in the outcomes of early life stress, since not all people exposed to early adversities develop depression later in life. GxE interactions may indeed also explain why adverse environmental factors do not increase the risk of depression in each and every individual.

Two of the most established examples of GxE interactions linking stress to depression result from the hypothesis-driven investigation of the serotonin transporter promoter short/long polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and of a functional single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) within the FK506-binding protein 51 (FKBP5) gene. Caspi and colleagues were the first to show that individuals with one or two copies of the short allele of the 5-HTTLPR exhibit more depressive symptoms and suicidality in the presence of stressful life events as compared with individuals homozygous for the long allele [11]. Although not all the studies have replicated these findings [12], this GxE interaction has been shown to predict depression in individuals exposed to childhood maltreatment [13, 14]. Similarly, many studies have shown that a functional SNP within FKBP5 (rs1360780) interacts with childhood abuse to predict a multitude of psychiatric phenotypes in adults, including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder [15–19]. For this latter gene, epigenetic mechanisms leading to different cortisol reactivity to stress seem to explain these effects [20, 21]. These two examples of GxE interactions are built on decades of hypothesis-driven research, and have been instrumental in order to identify not only genetic variants that increase the risk of depression, but also the potential biological and molecular mechanisms underlying this increased risk. However, as extensively discussed elsewhere [8], this hypothesis-driven approach can only discover a fraction of such potential existing genetic variants, and it is at odds with the current strategy of using a hypothesis-free approach to identify genes associated with disorders.

Of course, using GWAS data to test GxE interactions would be a theoretically viable option, but it would require enormous datasets with both exposure (such as life events) and outcome (depression) data. To date, only two genome-wide by environment interaction studies (GWEIS) have been performed in this regard. Dunn and colleagues (2016) [22], using data from the SHARe cohort of the Women’s Health Initiative comprising more than 10 thousand African Americans and Hispanics/Latinas, have examined genetic main effects and GxE interactions with stressful life events and social support in the development of depressive symptoms; however, only one interaction signal was genome-wide significant in African Americans (rs4652467 located 14 kb from CEP350), and it was not replicated. The second, subsequent whole genome pilot study, performed in only 320 subjects characterized for recent stressful life events, found no interaction that was genome-wide significant [23].

In the current paper, we propose a different ‘omics-based’ approach to identify candidate genes for GxE interactions studies in GWAS datasets, using cross-species and cross-tissue biological prioritization strategies that limits the number of investigated genes and thus enhances the statistical power to identify significant findings. In particular, we have first analyzed the transcriptome and miRNome data from the hippocampus of adult rats exposed to prenatal stress (PNS), a well-established model of early life stress leading to depressive behavior and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis hyperactivity in adulthood [24], in order to obtain a list of genes that are both modulated by PNS and targeted by the miRNAs that are modulated by PNS. We have then integrated the resulting genes list with transcriptome data obtained from blood mRNA of human adults who had suffered from childhood trauma, and analyzed the overlapping genes list using network analysis, which identifies genes and molecules that interact with each other because of physical interaction or co-expression, or because they are related in common signaling pathways. Finally, we have tested the top network cluster of genes for GxE interactions in order to examine the effects of early life stress on depressive symptoms in adulthood, in two different clinical samples from the Grady Trauma Project in Atlanta (USA) [25] and the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study (Finland) [26, 27]. In vitro experiments in a human hippocampal progenitor cell line were also conducted to confirm the role of the identified genes in stress responsivity.

Material and methods

Animal model and clinical samples

Prenatal stress model (for transcriptomics and miRNomics analyses)

PNS procedure was performed as already published [28–30]; briefly, pregnant dams in the last week of gestation were restrained in a transparent Plexiglas cylinder, under bright light, for 45 min, three times a day for 1 week. Control pregnant females were left undisturbed in their home cages. Male offspring from control and PNS groups were killed at postnatal day (PND) 62 (early adulthood) for whole hippocampal dissection (for further details see Supplementary Material). Rat handling and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the EC guidelines (EC Council Directive 86/609 1987) and with the Italian legislation on animal experimentation (D.L. 116/92), in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Subjects exposed to early life trauma (for transcriptomics analysis)

We recruited volunteer subjects from the local population living in the area served by the South London and Maudsley NHS Trust, in south-east London. Childhood traumatic events were assessed using the Childhood Experience of Care Abuse Questionnaire (CECA-Q; [31]). All the volunteers were screened using the Psychosis Screening Questionnaire (to exclude any psychotic and psychotic-like symptoms). We performed transcriptomic analyses in 20 subjects who reported at least two types of abuse (separation and physical abuse = 40%; separation and sexual abuse = 20%; physical and sexual abuse = 5%; physical and emotional abuse = 5%) or one type of severe abuse (physical abuse only = 20%; emotional abuse only = 5%; sexual abuse only = 5%); and in 20 subjects matched for age, gender and body mass index (BMI) with no history of early life trauma. Mean age ± SD was 27 ± 1.6 and 25 ± 0.9 (df = 15; ℵ2 = 0.222, p-value = 0.3), and percentage of females was 45% (7 F/13 M) and 35% (9 F/11 M) (ℵ2 = 0.417, p-value = 0.5), respectively, in the subjects with and without childhood trauma. We collected information about current medications (one subject was taking oral contraception and one was in treatment with mefenamic acid), general health (asthma, eczema, frequent headaches, recent infections), education, employment, nicotine, and cannabis smoking; the two groups were not different for any of these variables (data not showed).

Blood samples were collected by using PaxGene Blood Tubes. After collection, blood samples were kept at room temperature for 2 h, then at −20 °C for 2 days and then at −80 °C until their processing. The project was approved by the Local Ethical Committee and subjects signed a consent form (for further details see Supplementary Material).

Grady trauma project (for GxE analysis)

In the Grady Trauma Project, recruited in Atlanta (Georgia, USA), detailed trauma interviews were collected in a large sample of 4791 adults (mean age ± SD of 40.1 ± 13.9) with high rates of current and lifetime PTSD. For this study, we used the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), a 28-item, psychometrically validated inventory assessing self-reported levels of sexual, physical and emotional abuse [32]. The presence of moderate-severe sexual, physical and emotional abuse was coded as described before [33]. Emotional abuse was used for the main GxE analyses on early life emotional stress, across both this and the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Depressive symptoms were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [34]. The institutional review board at Emory University approved the study procedures. All participants provided written informed consent before participating.

Helsinki birth cohort study (for GxE analysis)

Between 2001 and 2004, 1620 individuals (mean age ± SD of 61.5 ± 2.9) who were born at Helsinki University Central Hospital between 1934 and 1944, and who were alive and living in Finland in 1971, participated into a clinical examination during which blood samples for DNA were used to obtain GWAS data for both directly genotyped and imputed SNPs. Depressive symptoms were measured using the BDI [34]. Early life emotional stress in this samples was defined as separation from biological parents in 1939–1946, during the second world war, when around 80,000 Finnish children were sent to Sweden and Denmark in order to escape the dangers of war; 384 subjects were identified as having been separated in childhood [26, 27, 35]. These children were separated by both parents and their siblings at the median age of 3.8 years (Range 0.6–10.1 years) for a mean duration of 1.4 years (Range 0.2–4.7 years), thus severely disrupting the attachment to significant caregivers. Previous studies in this cohort have clearly shown that these subjects show worse mental health in adulthood. For example, they report almost double the risk of experiencing depressive symptoms over time [36] and have higher risks of mental disorders, including substance abuse and personality disorders [37, 38]. Interestingly for the context of our paper, they also show higher cortisol levels and more pronounced cortisol reactivity [39]. The project was approved by the Local Ethical Committee (for further details see Supplementary Material).

Biological assessments

mRNA and miRNA isolation from hippocampus of animals and from the blood of subjects

Total RNA, including miRNAs, was isolated from rat brain tissues by using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Italy) and from human blood samples using PaxGene miRNA kit (Qiagen, Italy), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were also treated with DNase, and RNA quantity and quality was assessed by evaluation of the A260/280 and A260/230 ratios using a Nanodrop spectrometer (NanoDrop Technologies).

Whole Genome expression microarray analyses in the hippocampus of animals and in the blood of subjects

Gene expression microarray assays were performed using Rat Gene 2.1st Array Strips (which covers 27,147 coding transcripts) or Human Gene 2.1st Array Strips (which covers 31,650 coding transcripts) on GeneAtlas platform (Affymetrix), following the WT Expression Kit protocol described in the Affymetrix GeneChip Expression Analysis Technical Manual, and as we have done before [28, 40] (for further details see Supplementary Material). Of note, this is the first report of the rat hippocampal transcriptome following PNS using the novel Rat Gene 2.1st Array Strips, hence we have reported here all the relevant data and pathways analyses.

Real Time validation analyses of transcriptomic findings in the hippocampus of animals and in the blood of subjects

All the genes that were significantly modulated by stress both in the hippocampus of animals and in the blood of subjects (n = 22 genes, see Results Section) were validated using Real-Time PCR by using Biorad qPCR Mix (BioRad, Milan) and Taqman Assays on a 96 wells Real Time PCR System (One Step TaqMan Real Time PCR). Each sample was assayed in triplicate and each target gene was normalized to β-actin and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in rodents, and to β−2-microglobulin (B2M) and GAPDH in humans. The Pfaffl Method was used to determine relative target gene expression.

MiRNome expression analysis in the hippocampus of animals

Five hundred nanogram of total RNA (including miRNAs) were processed with the FlashTag Biotin HSR RNA Labeling kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and subsequently hybridized onto the GeneChip miRNA 4.1 Array Strip on a GeneAtlas platform (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The GeneChip miRNA 4.1 Array Strip shows a comprehensive coverage as they are designed to interrogate all mature miRNA sequences in miRBase Release 20. Washing/staining and scanning procedures were conducted on the Fluidics station following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Genotyping of polymorphisms within the Grady Trauma Study

DNA was extracted from saliva in Oragene collection vials (DNA Genotek, Ottawa, ON, Canada) using the DNAdvance kit (Beckman Coulter Genomics, Danvers, MA, USA), while DNA from blood was extracted using either the E.Z.N.A. Mag-Bind Blood DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA) or ArchivePure DNA Blood Kit (5 Prime, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). N = 4,791 subjects were genotyped on the HumanOmniExpress (6%) and the Omni1-Quad BeadChip (94%) (Illumina Inc), and genotypes were called with Illumina’s Genome Studio. The HumanOmniExpress interrogates 730,525 individual SNPs per sample, whereas the Omni1- Quad BeadChip interrogates 1,011,219 individual SNPs (for further details see Supplementary Material).

Genotyping of polymorphisms in the helsinki birth cohort study

DNA was extracted from blood samples using Gentra Kit. Participants were genotyped with the modified Illumina 610 k array, at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Cambridge, UK according to standard protocols [38] (for further details see Supplementary Material).

Statistical and bioinformatics analysis

Transcriptomic and miRNome statistical analysis

Raw data were imported and analyzed with the software Partek Genomic Suite 6.6 (Partek, St. Louis, MO, USA). We checked for quality control and batch effects using the Principal Component Analyses (PCA) in the Partek Genomic Suite Software, and we did not observe any outlier or any batch effect, thus we did not correct for this. After quality control of the data, Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was performed to assess the effects of PNS on genes expression or miRNAs expression in rats, and of history of early life adversities on gene expression in humans. A maximum filter of p < 0.05 (FDR corrected) and a minimum absolute fold change cut-off of 1.4 in animals and of 1.2 in humans was applied to select the lists of significant genes. The miRNAs-mRNAs combining analyses was performed using a specific sub-feature in Partek Genomic Suite 6.6. For blood transcriptome, possible differences in cell type between the two groups were evaluated by using CellMix package builds on R/BioConductor and available from http://web.cbio.uct.ac.za/~renaud/CRAN/web/CellMix, and as we have not detected differences in childhood trauma exposed subjects as compared to non-exposed individuals we did not use it as covariate.

Pathway analyses

List of significant genes were analyzed for pathway analyses by using Ingenuity Pathway Analyses Software (IPA) where, as a background, we used gene lists that we obtained applying the minimum absolute fold change cut-off of 1.4 in animals and of 1.2 in humans and q-value <0.05.

Animal and human integration data

The genes lists deriving from rats (following miRNAs-mRNAs combining analyses) and humans (mRNAs only) were cross-integrated, and the list of common genes was tested for random probability by Hyper-Geometric Distribution test [41] in R.

Network analyses

The list of common genes from animal and human data were used for network analyses using specific tools in IPA.

GXE interactions

Grady trauma project

We transformed imputed genotypes to best guessed genotypes using a probability threshold of 90%. To assess GxE interaction, we individually tested each SNP within the three genes of interest resulting from the final network analysis and also available in the Helsinki Birth cohort study, for interactions between emotional stress (emotional abuse) and BDI scores in adulthood, as a similar phenotype was also present in the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Age, gender, and the first two principal components of the identity-by-state (IBS) matrix were used as covariates in the linear regression analyses in R. We made further adjustments for SNP X covariate and child abuse X covariate interactions, as suggested by Keller [42]. In addition, secondary analyses were conducted testing GxE interaction between each type of childhood trauma (emotional, sexual and physical abuse) and BDI scores in adulthood, in this sample only.

Helsinki birth cohort study

We tested those SNPs within the three genes of interest resulting from the final network analysis that were also available in the Grady Trauma Project, for interactions between emotional stress (whether the individual was separated from parents during WWII, or not) and BDI scores in adulthood, using linear regression analysis. Each SNP was tested in a separate model; age at testing, gender, and the first three principal components of the IBS matrix, main effects of the gene and the environment were used as covariates. We made further adjustments for SNP × covariate and separation status × covariate interactions, as suggested by Keller [42].

Meta-analyses

We ran a fixed-effects meta-analysis combining the interaction results testing emotional stress in both cohorts, using the R-package Rmeta. Meta-analysis p-values were corrected for multiple testing using Bonferroni-correction over all tested SNPs.

Cell culture, gene expression and neurogenesis assay

The immortalized, multipotent human fetal hippocampal progenitor cell line, HPC0A07/03C (propriety of ReNeuron), was used for all cellular and molecular analyses (mRNA levels, neuronal proliferation). Details of this cell line, the proliferation protocol, gene expression and immunocytochemistry can be found in Supplementary Information Materials and Methods.

Results

Transcriptomic changes in the hippocampus of adult male rats following PNS

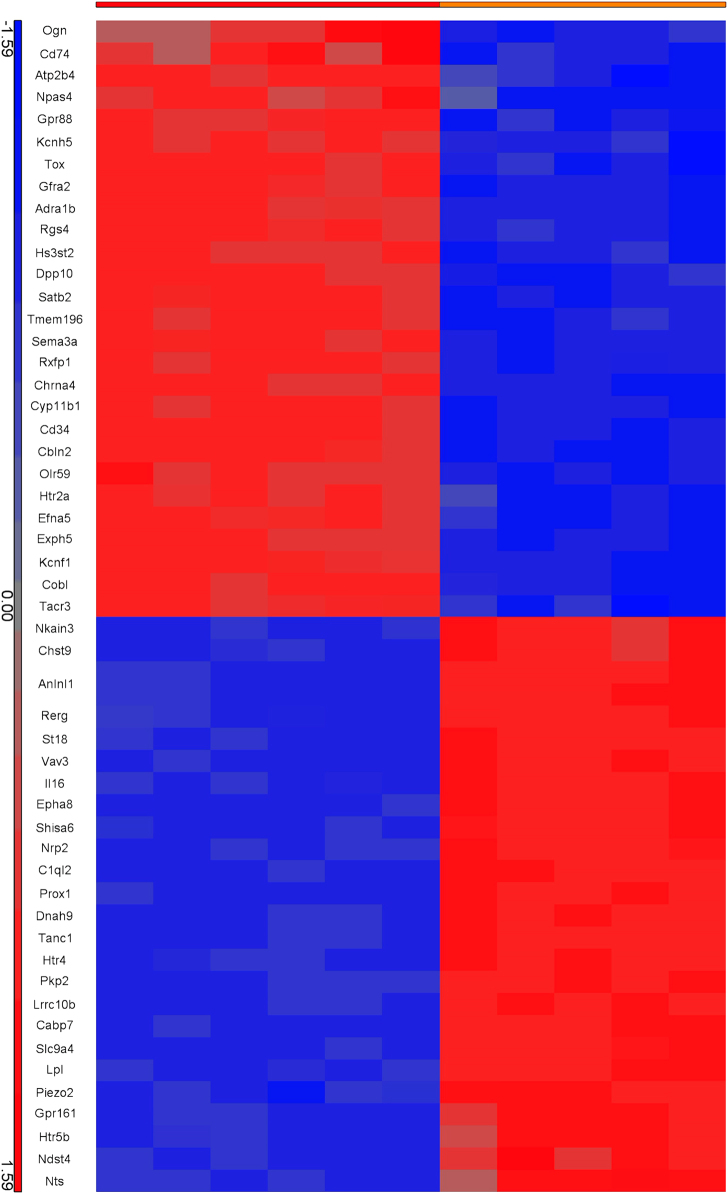

Our first aim was to identify gene expression changes in the hippocampus of male adult rats (at PND 62) that had been exposed to PNS. We analyzed the entire transcriptome and we found a significant modulation of 916 genes in the comparison with control animals (using 1.4 < FC < −1.4, q-value <0.05). We have visualized the most significant genes in a hierarchical clustering in Fig. 1, and listed the 916 significant genes in Supplementary Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Hierarchical Clustering of gene expression changes by prenatal stress (PNS) in the hippocampus of rats, in comparison with control animals. The red bar on the horizontal axis indicates control animals and the orange bar indicates PNS-exposed animals. The blue and the red squares in each group (CTRL or PNS) indicate the modulation of the gene expression, with red squares indicating genes that are up-regulated and blue squares gene that are down regulated

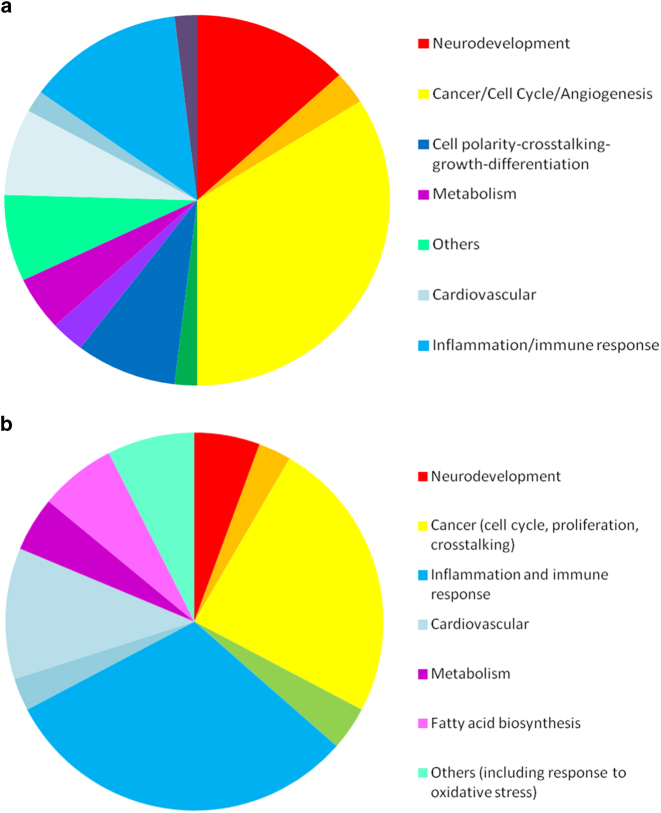

We then performed a pathway analysis on the significantly modulated genes, in order to identify the main biological processes involved. We identified 49 biological processes that were altered by the PNS exposure, including some involved in neurodevelopment (Axonal Guidance Signaling, Protein Kinase A Signaling, Glutamate Receptor Signaling, Wnt/β-catenin Signaling, CREB Signaling in Neurons, Synaptic Long Term Depression, Synaptic Long Term Potentiation, Glucocorticoid Receptor Signaling) and inflammation (IL-8 Signaling, STAT3 Pathway, CDK5 Signaling, IL-1 Signaling, IL-6 Signaling, BMP signaling pathway and TGF-β Signaling). All the significant pathways are summarized by the pie-chart detailing the relevant functional areas (Fig. 2a), while the entire list of significant pathways is presented in Supplementary Table 2. We conducted the subsequent target prioritization steps using the full list of 916 differentially regulated genes.

Fig. 2.

a Pathways pie chart in prenatally stressed animals. The pie chart represents the functional relevance of the significant pathways found modulated in the hippocampus of PNS-exposed adult rats. b Pathways pie chart in adults with a history of childhood trauma. The pie chart represents the functional relevance of the significant pathways found modulated in the blood of adult subjects exposed to childhood trauma

MiRNome changes in the hippocampus of PNS rats, and combined analyses with transcriptomic changes

We subsequently investigated whether exposure to PNS causes changes in miRNAs levels, and whether the identified miRNAs could target transcripts identified in the transcriptomics analysis. After the selection of the species (Rattus Norvegicus), we identified a total number of 1218 miRNAs (including pre-miRNAs and mature miRNAs); out of these, 68 miRNAs (47 of them were mature miRNAs) were significantly modulated (all with q-value <0.05) in animals exposed to prenatal stress, with sixty-five downregulated and only 3 up-regulated (see Table 1).

Table 1.

List of miRNAs (both mature and non-mature miRNAs) significantly modulated (all with q-value <0.05) in animals exposed to prenatal stress, compared with control animals

| miRNA name | Fold-change | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | rno-miR-3473 | –1,7 |

| 2 | rno-mir-3593 | –1,2 |

| 3 | rno-miR-339–5p | –1,4 |

| 4 | rno-mir-1839 | –1,2 |

| 5 | rno-mir-3556b | –1,2 |

| 6 | rno-miR-133b-5p | –1,3 |

| 7 | rno-miR-1839–5p | –1,2 |

| 8 | rno-mir-322 | –1,3 |

| 9 | rno-mir-425 | –1,2 |

| 10 | rno-mir-18a | –1,3 |

| 11 | rno-mir-3085 | –1,3 |

| 12 | rno-mir-329 | –1,2 |

| 13 | rno-miR-370–3p | –1,4 |

| 14 | rno-miR-181c-5p | –1,3 |

| 15 | rno-miR-872–3p | –1,5 |

| 16 | rno-miR-423–3p | –1,6 |

| 17 | rno-miR-93–3p | –1,6 |

| 18 | rno-mir-872 | –1,3 |

| 19 | rno-miR-152–3p | –1,4 |

| 20 | rno-mir-448 | –1,3 |

| 21 | rno-miR-3068–3p | –1,4 |

| 22 | rno-mir-532 | –1,3 |

| 23 | rno-mir-290 | –1,2 |

| 24 | rno-miR-106b-3p | –1,4 |

| 25 | rno-mir-27b | –1,2 |

| 26 | rno-mir-203a | 1,3 |

| 27 | rno-miR-362–5p | –1,5 |

| 28 | rno-miR-877 | –1,4 |

| 29 | rno-miR-7a-1–3p | –1,5 |

| 30 | rno-miR-135b-3p | –1,5 |

| 31 | rno-miR-6328 | –1,2 |

| 32 | rno-miR-540–3p | –1,4 |

| 33 | rno-mir-376a | –1,2 |

| 34 | rno-miR-10b-5p | –1,3 |

| 35 | rno-miR-425–3p | –1,5 |

| 36 | rno-miR-330–5p | –1,4 |

| 37 | rno-miR-6326 | –1,3 |

| 38 | rno-mir-764 | –1,3 |

| 39 | rno-miR-200a-5p | –1,2 |

| 40 | rno-mir-494 | –1,2 |

| 41 | rno-mir-379 | –1,3 |

| 42 | rno-miR-151–3p | –1,2 |

| 43 | rno-miR-28–3p | –1,5 |

| 44 | rno-miR-15b-5p | –1,4 |

| 45 | rno-miR-324–3p | –1,3 |

| 46 | rno-miR-871–3p | 1,2 |

| 47 | rno-miR-214–3p | –1,4 |

| 48 | rno-mir-101b | –1,3 |

| 49 | rno-miR-325–5p | –1,3 |

| 50 | rno-miR-339–3p | –1,4 |

| 51 | rno-mir-196c | –1,4 |

| 52 | rno-miR-6324 | –1,6 |

| 53 | rno-miR-19b-3p | –1,4 |

| 54 | rno-miR-20b-5p | –1,6 |

| 55 | rno-miR-666–3p | –1,5 |

| 56 | rno-miR-351–5p | –1,2 |

| 57 | rno-miR-99b-3p | –1,3 |

| 58 | rno-mir-135a | –1,3 |

| 59 | rno-miR-139–3p | –1,4 |

| 60 | rno-miR-342–5p | –1,3 |

| 61 | rno-miR-376b-3p | –1,3 |

| 62 | rno-miR-450a-5p | 1,3 |

| 63 | rno-miR-140–5p | –1,6 |

| 64 | rno-miR-493–3p | –1,5 |

| 65 | rno-miR-532–5p | –1,3 |

| 66 | rno-miR-124–5p | –1,3 |

| 67 | rno-miR-1843–5p | –1,3 |

| 68 | rno-miR-6215 | –1,3 |

As both transcriptomic and miRNome analyses were conducted in the hippocampus of the same animals, we then performed a mRNA-miRNAs combining analysis that allows the identification of a panel of top-hit genes that were both modulated by PNS exposure and targeted by the miRNAs that were modulated by PNS (see Methods). These analyses identified 528 significant genes, presented in Supplementary Table 3. The specific pathways analysis shows that these were genes involved in neurodevelopment (Axonal Guidance, Protein Kinase-A Signaling, Glucocorticoid Receptor Signaling, TGF-β Signaling) and inflammation (STAT3 Pathway, PTEN Signaling, ILK Signaling, IL-8 signaling); the full list of the 42 pathways is presented in Supplementary Table 4.

Blood mRNA transcriptomics of early life trauma in humans

Comparing subjects with and without exposure to early life trauma (see Methods for sociodemographic and clinical information), we identified 250 genes that were differentially modulated (FC > 1.2, FDR q-value <0.05) (see Supplementary Table 5), involved in the modulation of 41 significant pathways. Of note, these were, again, pathways involved in neurodevelopment (Wnt/Ca + pathway, cAMP signaling, CREB signaling) and inflammation (eNOS signaling, chemokine signaling, B cell activation), similar to what we found in the PNS model. All the significant pathways are summarized by the pie-chart detailing the relevant functional areas in Fig. 2b, and listed in Supplementary Table 6.

Integrating data from PNS in animals and from early life trauma in humans

In the next step, we integrated the 528 genes obtained by combined mRNA/miRNA analyses in the hippocampus of rats exposed to PNS with the 250 genes significantly modulated in the blood of adults exposed to early life trauma. We identified 22 common genes that were present in both lists; according to the hypergeometric distribution test, the probability that these genes were not overlapping due to random probability was p = 1.8 × 10–8.

Finally, we validated all of the 22 genes by Real–Time PCR, both in the hippocampus of animals and in the blood of adults exposed to childhood trauma. In line with the microarray results, 16 genes were modulated in the same direction both in the rat hippocampus and in the human blood, and 6 were modulated in the opposite direction. Specifically, 15 were up-regulated in both: Alpha-2-Macroglobulin (A2M), AT-Rich Interaction Domain 5B (ARID5B), Arrestin Domain Containing 4 (ARRDC4), EPH Receptor A4 (EPHA4), F-Box Protein 32 (FBXO32), Forkhead box protein O1 (FoxO1), Heat Shock Transcription Factor 2 (HSF2), Isochorismatase Domain Containing 1 (ISOC1), Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor Adapter Protein 1 (LDLRAP1), Leucine-rich repeat neuronal protein 3 (LRRN3), Myosin ID (MYO1D), Phosphatidylinositol-4-Phosphate 3-Kinase, Catalytic Subunit Type 2 Beta (PIK3C2B), Phosphatidic Acid Phosphatase Type 2A (PPAP2A), Sterile Alpha Motif Domain Containing 12 (SAMD12), and Serine Incorporator 5 (SERINC5); one was down-regulated in both: Transforming Growth Factor, Beta 1 (TGF-β1); one was up-regulated in rats and down-regulated in humans: Solute Carrier Family 24 (Sodium/Potassium/Calcium Exchanger) Member 3 (SLC24A3); and 5 were down-regulated in rats and up-regulated in humans: B-Cell CLL/Lymphoma 2 (BCL2), B-Cell CLL/Lymphoma 9 (BCL9), Lymphoid Enhancer-Binding Factor 1 (LEF1), Lin-54 DREAM MuvB Core Complex Component (LIN54), and Post-GPI Attachment to Proteins 1 (PGAP1). These genes are presented in Supplementary Table 7, where we also present the FCs obtained from the microarray studies and the FCs from Real Time PCR analyses. For all the above-mentioned molecular and biochemical analyses, all data met the assumptions of normal distribution and equality of variance.

Gene network analysis and selection of candidates for GxE interaction

We focused on the 16 genes (A2M, ARID5B, ARRDC4, EPHA4, FBXO32, FoxO1, HSF2, ISOC1, LDLRAP1, LRRN3, MYO1D, PIK3C2B, PPAP2A, SAMD12, SERINC5, and TGF-β1) that were modulated in the same direction both in animals and in humans, and we applied a gene network analysis to identify possible interactions among these genes. Indeed, our main theoretical framework was based on the notion that depression is a complex disorder, where multiple genes interact with each other as belonging to common or overlapping signaling systems. Therefore, also to minimize any chance findings, we decided a priori to select, for the subsequent GxE interaction analyses, only those genes that interacted with each other through physical interaction, co-expression or involvement in common pathways.

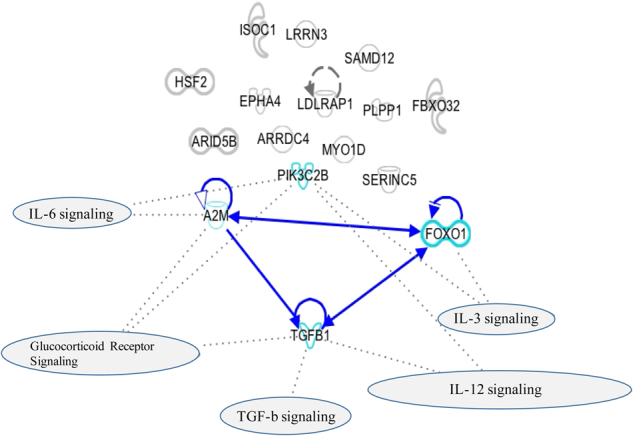

Using IPA Software, we observed only one cluster of interacting genes, represented by A2M, FoxO1 and TGF-β1 (Fig. 3). Using a gene enrichment/pathway analysis, we then confirmed that this cluster is involved in cytokines signaling, TGF- β1 signaling and glucocorticoid receptor signaling. As we found that A2M, FoxO1, and TGF-β1 form a single individual cluster of genes interacting with each other, we focused on these three genes for the subsequent GxE studies.

Fig. 3.

Network Analyses on the 16 common genes between rats and humans. Network Analyses of the 16 common genes modulated in the same direction both in the hippocampus of rats exposed to prenatal stress and in the blood of adults exposed to childhood trauma. The blue lines indicate direct interactions between molecules (A2M, FoxO1, and TGF-β1). The dot lines indicate the involvement of molecules within pathways

Gene X environment interaction studies

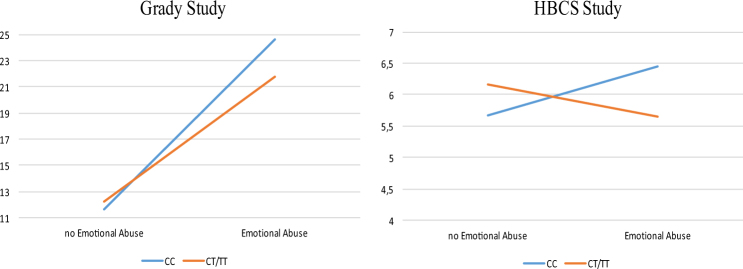

For our main analyses, we focused on all the SNPs located in these three genes and available in both the Grady Trauma Project and Helsinki Birth cohort (FoxO1, n = 132 SNPs; A2M, n = 91 SNPs; and TGF-β1, n = 14 SNPs), and we tested their interaction with emotional stress in childhood in predicting depressive symptoms in adulthood (BDI scores) for both cohorts (Table 2). Then, we assessed the combined effect over both cohorts and performed a meta-analysis (See Supplementary Table 8). The meta-analyses indicated that 6 SNPs, all located within the FoxO1 gene, were significantly associated with emotional stress in predicting depressive symptoms, and also survived multiple testing correction for GxE interactions, with the SNP rs17592371 showing the strongest significance (p = 0.003, Bonferroni correction). For all the 6 SNPs, p-values for heterogeneity of effects were not significant, indicating that fixed-effects meta-analysis was justified. The GxE interaction effect for the SNP rs17592371 in both cohorts is presented in Fig. 4, where we can see that individuals with “at risk” genotypes (CC) developed more depressive symptoms in the presence of early separation as compared to individuals with the “low risk” genotypes (CT and TT).

Table 2.

Gene X Environment interactions in the two clinical samples for the six genes identified to be associated with emotional stress in the Grady Trauma Project and in the Helsinki Birth Study Cohort

| GENE | SNPs FOXO1 | Grady Trauma Project | Helsinki Birth Study Cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β score | p-value | β score | p-value | ||

| FoxO1 | rs17592371 | –3,035 | <0,0001 | –1,780 | 0,033 |

| FoxO1 | rs2297626 | –2,601 | 0,0002 | –1,808 | 0,037 |

| FoxO1 | rs17592468 | –2,549 | 0,0003 | –1,763 | 0,034 |

| FoxO1 | rs28553411 | –2,549 | 0,0003 | –1,763 | 0,034 |

| FoxO1 | rs7319021 | –2,549 | 0,0003 | –1,763 | 0,034 |

| FoxO1 | rs12585452 | –2,416 | 0,0007 | –1,796 | 0,032 |

Fig. 4.

Interaction effect between rs17592371 and stress on BDI symptoms. Estimated marginal means of BDI scores for different genotypes of the FoxO1 single nucleotide polymorphism rs17592371 in subjects who were or were not exposed to emotional abuse in the Grady Trauma Project (on the left) and in the Helsinki Birth Study Cohort (on the right). Values are adjusted for gender and age

We also conducted additional, secondary analyses on these three genes, in the Grady Trauma Project sample, because it has a wider range of abuse phenotypes. Specifically, we tested the interaction between childhood sexual, physical or emotional abuse, and depressive symptoms in adulthood (BDI scores). Within FoxO1, 6 SNPs showed significant GxE interactions with sexual abuse, 40 SNPs with physical abuse and 40 SNPS with emotional abuse (although with a large overlap between SNPs); within A2M, 7 SNPs showed significant GxE interactions with emotional abuse; and within TGF-β1, 4 SNPs showed significant GxE interactions with sexual abuse and 1 SNP with emotional abuse (See Supplementary Table 9).

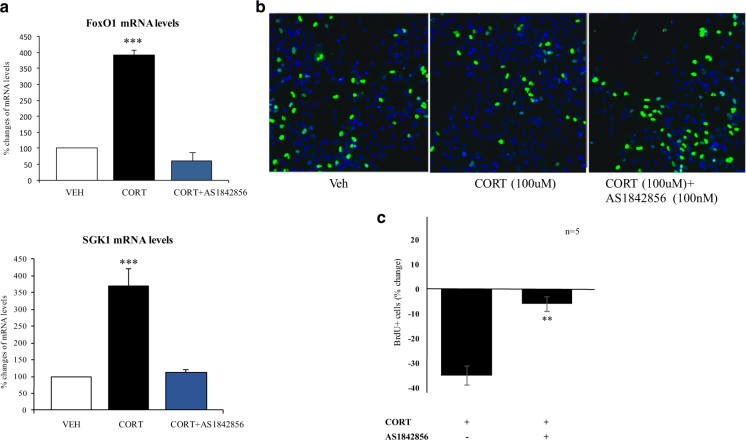

FoxO1 is activated in hippocampal progenitor stem cells following cortisol exposure, and it mediates the negative effect of stress on neurogenesis

As FoxO1 was up-regulated both in the hippocampus of animals exposed to PNS and in the blood of subjects exposed to childhood trauma, and it was also the most significant gene from our GxE analyses across the two clinical cohorts, we decided to test the functional relevance of this gene. Specifically, we wanted to test: 1) whether the stress-induced FoxO1 upregulation could be replicated in vitro upon treatment with the human stress hormone, cortisol, using our established model of ‘depression in a dish’, the immortalized, multipotent human fetal hippocampal progenitor cell line (HPC0A07/03C); and 2) whether FoxO1 is involved in the cortisol-induced reduction of neuronal proliferation that we had previously described in this model [28].

Consistent with our hypothesis, FoxO1 mRNA levels were significantly increased following 24 h of treatment with 100 μM cortisol (FC = + 3.9, p < 0.0001, Fig. 5a). Moreover, the cell-permeable inhibitor of FoxO1, AS1842856 (100 nM), was able to completely inhibit the cortisol-induced upregulation of FoxO1 (Fig. 5a) and the cortisol-induced reduction in neuronal proliferation (BrdU + cells; one-way ANOVA, p = 0.01 versus cortisol, Fig. 5b, c). AS1842856 alone did not exert any effects on proliferation (p = 0.9), indicating that FoxO1 mediates the effect of stress, but it is not active under baseline conditions.

Fig. 5.

Cortisol treatment (100 μM) increases FoxO1 and SGK1 mRNA levels and decreases neurogenesis via a FOXO1-dependent effect. a Gene expression levels of FoxO1 and of SGK1. b BrdU immunocytochemistry was used to assess proliferation. c The FOXO1 inhibitor, AS1842856 (100 nM) counteracted the CORT-induced reduction in proliferation (n = 5). Data are mean ± SEM **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Finally, in order to investigate the molecular pathways by which FoxO1 signaling regulates the effects of stress on neuronal proliferation, we measured also the mRNA levels of a stress- and cortisol-induced gene, the Serum Glucocorticoid Kinase 1 (SGK-1), again following cortisol with or without AS1842856. SGK1 is a stress responsive gene that mediates some of the glucocorticoid effects on brain function [43], including the negative effects of cortisol on neurogenesis [28], and we found that SGK1 is elevated in both the hippocampus of stressed rats and in the blood of depressed patients [44]. We found that 24 h of cortisol (100 uM) treatment up-regulates SGK1 mRNA levels (FC = + 3.7, p < 0.0001, Fig. 5a), replicating again our previous findings [44], and that AS1842856 was able to counteract such changes (Fig. 5a).

Discussion

We provide a novel ‘hypothesis-free’ approach for the identification and prioritization of candidate genes that can be investigated in GWAS datasets to test GxE interaction studies in depression. In particular, by employing “omics” approaches in animals (mRNAs and miRNAs) and in humans (mRNAs), and cross-species validation, we have identified one cluster of genes, comprising FoxO1, A2M, and TGF-β1, that show significant GxE interactions predicting adult depression in the context of early life trauma in our study, and have also been previously involved in the regulation of mechanisms relevant to stress and depression [45–49]. Our main findings, confirmed by a meta-analysis run on both cohorts, indicate that several SNPs within FoxO1 interact with emotional stress during childhood in predicting adult depression, both in the Grady Trauma Project, as well as in the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Importantly, we also describe a functional role of FoxO1 in stress responsivity in our in vitro model of human hippocampal progenitor cells. In addition, secondary analyses show that several SNPs within FoxO1, A2M, and TGF-β1 interact with emotional, physical and sexual abuse in predicting adult depression in the Grady Trauma Project.

A large body of evidence has rapidly accumulated over the past years describing interactive effects of genetic factors and early life stressors in determining the risk of depression [8]. These ‘hypothesis-driven’ studies have mostly focused on genetic variations in candidate genes acting in neurobiological systems that have been previously implicated in the pathophysiology of major depression. As mentioned in the Introduction, the most consistent examples of this approach are studies examining the 5-HTTLPR SNP in the serotonin transporter [13, 50–53] and several functional SNPs within FKBP5 [17, 18]. However, numerous studies, and some meta-analyses, have produced discrepant results [50, 54–56]. New gene-environment interactions continue to be reported in psychiatry, including in genes as biologically varied as BDNF [57, 58], CD38 [59], ADCYAP1R1 [60], DRD2 [61] and GRIN2B [62], but always from hypothesis-driven research, which has a high risk of non-replication. Indeed, considering the current emphasis on omics-based approach in genetic-research, and especially in the context of a paucity of significant genetic effects for depression in GWAS studies, other statistical and biological prioritization strategies need to be developed to facilitate a systematic discovery of novel gene-environment interactions in genome-wide analyses. To our knowledge, the present study is the first report of a hypothesis-free, omics-, cross-tissues and cross-species approach to identify candidate genes for GxE interaction analyses. Interestingly, Mamdani and colleagues (2015) [63] recently used a similar approach to detect genes of interest in the context of alcohol dependence, combining data from mRNA and miRNA expression patterns in the brain of 18 patients with alcohol dependence and 18 matched controls; although they did not test for GxE interactions, they identified a network of hub genes that was enriched for genes identified by the Alcohol Dependence Genome Wide Association Study.

Our strongest findings, replicated in both clinical cohorts, pertain to FoxO1. FoxO1 belongs to the forkhead family of transcription factors, which are characterized by a distinct forkhead domain; it is the main target of insulin signaling, it regulates metabolic homeostasis in response to oxidative stress, it is modulated by glucocorticoids and it enhances inflammation [64]. It is also an important regulator of cell death acting downstream of Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1), AKT Serine/Threonine Kinase 1 (AKT1) and macrophage stimulating 1 (MST1), and indeed several studies have suggested that activation of FoxO1 contributes to glucocorticoid-induced cell death [65]. Importantly, FoxO1 is also involved in the maintenance of human embryonic stem cells pluripotency, a function that is mediated through direct control by FoxO1 of OCT4 and SOX2 gene expression, through occupation and activation of their respective promoters.

The six FoxO1 SNPs that were found associated with emotional stress in both cohorts are intronic SNPs, and therefore the mechanisms of action remain unclear, although likely affecting gene expression and not the function of the gene product. It is also possible that these SNPs can influence the protein conformation or the accessibility to phosphorylation sites. Indeed, a number of kinases can phosphorylate and regulate FoxO1 proteins either positively or negatively [66–68], including AKT serine/threonine protein kinase downstream of the PI(3)K (phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase) signaling pathway [69, 70], as well as SGK1, a kinase that is specifically activated by stress, glucocorticoids and depression. In particular, SGK1 phosphorylates FoxO1 at different sites, leading to subcellular redistribution of FoxO1 from the nucleus to the cytosol [71, 72]. Of note, we have previously described that SGK1 mediates the inhibitory effect of glucocorticoids on neurogenesis, and that its blood mRNA expression levels are elevated in patients with major depression [28]. Moreover, in the present paper we show that the glucocorticoid, cortisol, induces the mRNA levels of both FoxO1 and SGK1, and that an inhibition of FoxO1 prevents the SGK1 upregulation, indicating that this could be dependent on FoxO1, and thus that SGK1 may represent a novel target gene for FoxO1. Interestingly, Kaiser et al., [65] had shown similar findings in mouse pancreatic islet cells, although their paper only identified FoxO1 as a target of SGK1, and not vice versa. Taking into account also this last study, it is possible to speculate that FoxO1 activation during stress stimulates SGK1 activation, which could then further enhance FoxO1 phosphorylation.

There is some limited evidence already for a role of FoxOs in psychiatric disorders. Indeed FoxOs, especially FoxO6, are mainly expressed in hippocampus, amygdala and nucleus accumbens, which are important brain areas involved in aversive and rewarding responses to emotional stimuli [73, 74], suggesting that FoxOs may be involved in the regulation of mood and emotion. Moreover, FoxOs are regulated by antidepressants, as well as serotonin and norepinephrine receptor signaling [75]. Indeed, FoxO3a has emerged as a candidate gene involved in bipolar and unipolar disorders [76]. Moreover, in a learned helplessness animal model, inescapable shocks significantly reduce the phosphorylation of FoxO3a and induces the nuclear location of FoxO3a in the cerebral cortex; moreover, learned helplessness behavior is markedly diminished in FoxO3a-deficient mice [77]. These results are consistent with the report that FoxO3a influences behavioral processes linked to anxiety and depression, and that FoxO3a- deficient mice show reduced depressive behavior [78] while FoxO1 KO mice displayed reduced anxiety [78] behavior. This is in line with our finding in the present paper, as we describe higher levels of FoxO1 in the brain of rats exposed to prenatal stress, in the blood of subjects exposed to childhood trauma, and in cells treated with the stress hormone, cortisol; moreover, in vitro FoxO1 mediates the cortisol-induced reduction of neuronal proliferation. Together, these data indicate that enhanced levels of FoxO1 due to stress exposure are associated with enhanced vulnerability to develop stress related disorders.

The findings that both A2M and TGF-β1 have SNPs with significant GxE interactions in the Grady Trauma Project, albeit limited by the secondary nature of the analyses and the lack of a replication sample, still are of some interest, as both genes have been implicated in biological processes relevant to depression. A2M has traditionally been viewed as an inflammatory fluid proteinase scavenger, and recent studies have demonstrated the ability of A2M to bind to a plethora of cytokines, including TGF-β1 [79]. TGF-β1, in turn, is a member of TGF-β superfamily, which regulates neuronal survival, neurogenesis, synaptogenesis and gliogenesis [80–83]. Similar to the present study, where we found increased A2M mRNA levels following stress both in the rodent hippocampus and in the human blood, A2M is elevated in clinical samples and in experimental models relevant to depression; for example, higher levels of blood A2M are present in patients with total gastrectomy that develop depression, indicating that A2M elevation may be implicated in depression pathogenesis in the context of a pro-inflammatory status [84]; and fishes subjected to the stress of repeated emersions show higher blood levels of A2M [85]. High levels of A2M have indeed been associated with systemic inflammation [86], and therefore it is possible to speculate that the high levels of A2M described in this and other studies may translate into an increased risk of depression by activating the inflammatory system [40, 87, 88]. TGF-β1, in contrast, is reduced in conditions related to stress and depression, in the present study, as well as in previous studies. For example, TGF-β1 levels are reduced in the blood of depressed patients [89–91], and we have previously shown that the TGF-β1-SMAD signaling is one of the pathways that is most significantly down-regulated in neurons by in vitro exposures to high concentrations of cortisol, which mimics depression in vitro and negatively affects neurogenesis [28]. Finally, is of note that several SNPs within A2M and TGF-β1, including those that we have identified through our GxE interaction analyses, are associated with the development of several Complex Diseases and Disorders (see genetic association database from complex diseases and disorders https://geneticassociationdb.nih.gov). Moreover, genetic variants in TGF-β1 have been associated with other brain disorders, such as multiple sclerosis [92] and Alzheimer disease [93, 94].

It is important to emphasize that GxE interactions, while based on the effects of specific changes in DNA sequence, are likely to involve epigenetic mechanisms [95–97]. For example, recent studies have shown that the above-mentioned functional polymorphism in the FKBP5 gene increases the risk of developing depression and PTSD in adulthood by allele-specific, childhood trauma–dependent DNA demethylation in functional glucocorticoid response elements of FKBP5, followed by a long-term dysregulation of the stress hormone system and a global effect on the function of immune cells and of brain areas associated with stress regulation [98]. Besides DNA methylation, miRNAs have also recently emerged as important in the long-term regulation of gene expression associated with stress early in life [99–103]. The ability of miRNAs to selectively and reversibly silence the mRNAs of their target genes [104, 105], together with their involvement in biological processes modulated by stressful life events [106], make miRNAs well-suited to serve as fine regulators of the complex and extensive molecular network involved in stress response; hence, our decision in this paper of merging transcriptomics and miRNomics data in the selection of top-hit genes.

There are two limitations in our study that should be mentioned. First, only interactions with emotional stress were tested in both samples, and six FoxO1 SNPs survived multiple-testing correction and were confirmed by meta-analysis; the other SNPs in FoxO1, A2M and TGF-β1 that were associated with multiple types of abuse were only tested in the Grady Trauma sample, in secondary analyses. We trust that the use of a different clinical population (the South-East London sample) to generate transcriptomics, together with the cross-species validation, support the relevance of all of our findings, including the evidence for A2M and TGF-β1, but clearly these secondary analyses are only exploratory at this stage. Second, the samples size of the cohort of adult subjects with a history of childhood trauma used for transcriptomic analyses is relatively small, with n = 20 subjects per group. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first gene expression microarray study comparing the transcriptome in subjects exposed to childhood trauma versus non-exposed individuals, and thus provides informative findings. Moreover, the validity of our transcriptomics results is strengthened by the fact that we compare subjects not exposed to early life trauma with subjects exposed to the most severe types of trauma or to more than one traumatic event, thus maximizing the biological differences between the two groups. Finally, only the genes regulated also in the animal brains were selected for the further genetic association analyses, again strengthening the validity of our findings. All together, these lines of evidence defend the appropriateness of our sample size for the transcriptomics analyses.

In conclusion, our data provide a novel approach for the selection of novel susceptibility genes for GxE interaction in depression, alternative to ‘hypothesis-driven research’ and resulting in the prioritization of candidate genes starting from a ‘hypothesis-free’ approach. The evidence that the three identified genes all interact with environmental stress in inducing depressive symptoms, and that the statistically strongest gene, FoxO1, has functional relevance in stress-induced reduction of neurogenesis, support our theoretical framework. We propose that our prioritization strategy will limit the number of investigated genes in GWAS-based GxE interaction studies and thus will enhance the statistical power to identify significant findings. Moreover, we propose that FoxO1 may represent a target for the development of novel pharmacological therapies to prevent or treat stress-induced mental disorders.

Electronic supplementary material

Funding

This work was supported by the grants “Immunopsychiatry: a consortium to test the opportunity for immunotherapeutics in psychiatry’ (MR/L014815/1) and ‘Persistent Fatigue Induced by Interferon-alpha: A New Immunological Model for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome’ (MR/J002739/1), from the Medical Research Council (UK). Additional support has been offered by the National Institute for Health Research Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre in Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. Dr. A.C. has been funded by the Eranet Neuron ‘Inflame-D’ and by the Ministry of Health (MoH). This work was also supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of University and Research (PRIN–grant number 2015SKN9YT) and from Fondazione CARIPLO (grant number 2012-0503) to MAR.; from from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH071538) to EBB; from the Finish Academy to Professor to K.R. (No 7631758, No 284859, 2848591, 312670) and to adjunct professor J.L. (No 269925 and 311617).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Professor C.M.P. has received research funding from Johnson & Johnson as part of a program of research on depression and inflammation. In addition, Professor C.M.P. has received research funding from the Medical Research Council (UK) and the Wellcome Trust for research on depression and inflammation as part of two large consortia that also include Johnson & Johnson, GSK, Pfizer and Lundbeck. Prof. M.A.R. has received compensation as speaker/consultant for Lundbeck, Otzuka, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma and Sunovion, and he has received research grants from Lundbeck, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma and Sunovion, although none of these had a role in the present study. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Marco A. Riva and Carmine M. Pariante SHARED senior authorship.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41380-017-0002-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1552–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–7. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaugler T, Klei L, Sanders SJ, Bodea CA, Goldberg AP, Lee AB, et al. Most genetic risk for autism resides with common variation. Nat Genet. 2014;46:881–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nurnberger JI, Jr., Koller DL, Jung J, Edenberg HJ, Foroud T, Guella I, et al. Identification of pathways for bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:657–64. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C. Lee SH, Ripke S, Neale BM, Faraone SV, Purcell SM, et al. Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs. Nat Genet. 2013;45:984–94. doi: 10.1038/ng.2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric GC. Ripke S, Wray NR, Lewis CM, Hamilton SP, Weissman MM, et al. A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:497–511. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyde CL, Nagle MW, Tian C, Chen X, Paciga SA, Wendland JR, et al. Identification of 15 genetic loci associated with risk of major depression in individuals of European descent. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1031–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.3623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heim C, Binder EB. Current research trends in early life stress and depression: review of human studies on sensitive periods, gene-environment interactions, and epigenetics. Exp Neurol. 2012;233:102–11. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szyf M. The early life social environment and DNA methylation: DNA methylation mediating the long-term impact of social environments early in life. Epigenetics. 2011;6:971–8. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.8.16793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munafo MR, Durrant C, Lewis G, Flint J. Gene X environment interactions at the serotonin transporter locus. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:211–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uher R, Caspi A, Houts R, Sugden K, Williams B, Poulton R, et al. Serotonin transporter gene moderates childhood maltreatment’s effects on persistent but not single-episode depression: replications and implications for resolving inconsistent results. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Culverhouse RC, Saccone NL, Horton AC, Ma Y, Anstey KJ, Banaschewski T et al. Collaborative meta-analysis finds no evidence of a strong interaction between stress and 5-HTTLPR genotype contributing to the development of depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2017; doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.44, Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Zannas AS, Wiechmann T, Gassen NC, Binder EB. Gene-Stress-Epigenetic Regulation of FKBP5: Clinical and Translational Implications. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;41:261–74. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Comasco E, Gustafsson PA, Sydsjo G, Agnafors S, Aho N, Svedin CG. Psychiatric symptoms in adolescents: FKBP5 genotype-early life adversity interaction effects. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24:1473–83. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0768-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohrt BA, Worthman CM, Ressler KJ, Mercer KB, Upadhaya N, Koirala S, et al. Cross-cultural gene- environment interactions in depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and the cortisol awakening response: FKBP5 polymorphisms and childhood trauma in South Asia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27:180–96. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1020052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tozzi L, Carballedo A, Wetterling F, McCarthy H, O’Keane V, Gill M, et al. Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism of the FKBP5 Gene and Childhood Maltreatment as Predictors of Structural Changes in Brain Areas Involved in Emotional Processing in Depression. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;41:487–97. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lahti J, Ala-Mikkula H, Kajantie E, Haljas K, Eriksson JG, Raikkonen K. Associations Between Self-Reported and Objectively Recorded Early Life Stress, FKBP5 Polymorphisms, and Depressive Symptoms in Midlife. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;80:869–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hohne N, Poidinger M, Merz F, Pfister H, Bruckl T, Zimmermann P, et al. FKBP5 genotype-dependent DNA methylation and mRNA regulation after psychosocial stress in remitted depression and healthy controls. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;18:pyu087. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klengel T, Pape J, Binder EB, Mehta D. The role of DNA methylation in stress-related psychiatric disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2014;80:115–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn EC, Wiste A, Radmanesh F, Almli LM, Gogarten SM, Sofer T, et al. Genome-Wide Association Study (Gwas) and Genome-Wide by Environment Interaction Study (Gweis) of Depressive Symptoms in African American and Hispanic/Latina Women. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:265–80. doi: 10.1002/da.22484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otowa T, Kawamura Y, Tsutsumi A, Kawakami N, Kan C, Shimada T, et al. The First Pilot Genome-Wide Gene-Environment Study of Depression in the Japanese Population. PloS One. 2016;11:e0160823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luoni A, Rocha FF, Riva MA. Anatomical specificity in the modulation of activity-regulated genes after acute or chronic lurasidone treatment. Progress neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;50:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almli LM, Srivastava A, Fani N, Kerley K, Mercer KB, Feng H, et al. Follow-up and extension of a prior genome-wide association study of posttraumatic stress disorder: gene x environment associations and structural magnetic resonance imaging in a highly traumatized African-American civilian population. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76:e3–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barker DJ, Osmond C, Forsen TJ, Kajantie E, Eriksson JG. Trajectories of growth among children who have coronary events as adults. New Engl J Med. 2005;353:1802–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eriksson JG, Osmond C, Kajantie E, Forsen TJ, Barker DJ. Patterns of growth among children who later develop type 2 diabetes or its risk factors. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2853–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0459-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anacker C, Cattaneo A, Luoni A, Musaelyan K, Zunszain PA, Milanesi E, et al. Glucocorticoid-related molecular signaling pathways regulating hippocampal neurogenesis. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;38:872–83. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anacker C, O’Donnell KJ, Meaney MJ. Early life adversity and the epigenetic programming of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function. Dialog- Clin Neurosci. 2014;16:321–33. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.3/canacker. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luoni A, Macchi F, Papp M, Molteni R, Riva MA. Lurasidone exerts antidepressant properties in the chronic mild stress model through the regulation of synaptic and neuroplastic mechanisms in the rat prefrontal cortex. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol/Off Sci J Coll Int Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;18:pyu061. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bifulco A, Bernazzani O, Moran PM, Jacobs C. The childhood experience of care and abuse questionnaire (CECA.Q): validation in a community series. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44(Pt 4):563–81. doi: 10.1348/014466505X35344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Handelsman L. Predicting personality pathology among adult patients with substance use disorders: effects of childhood maltreatment. Addict Behav. 1998;23:855–68. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradley RG, Binder EB, Epstein MP, Tang Y, Nair HP, Liu W, et al. Influence of child abuse on adult depression: moderation by the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene. Arch General Psychiatry. 2008;65:190–200. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rikkonen K, Pesonen AK, Heinonen K, Lahti J, Kajantie E, Forsen T, et al. Infant growth and hostility in adult life. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:306–13. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181651638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pesonen AK, Raikkonen K, Heinonen K, Kajantie E, Forsen T, Eriksson JG. Depressive symptoms in adults separated from their parents as children: a natural experiment during World War II. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:1126–33. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raikkonen K, Lahti M, Heinonen K, Pesonen AK, Wahlbeck K, Kajantie E, et al. Risk of severe mental disorders in adults separated temporarily from their parents in childhood: the Helsinki birth cohort study. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lahti J, Raikkonen K, Bruce S, Heinonen K, Pesonen AK, Rautanen A, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor gene haplotype predicts increased risk of hospital admission for depressive disorders in the Helsinki birth cohort study. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:1160–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pesonen AK, Raikkonen K, Feldt K, Heinonen K, Osmond C, Phillips DI, et al. Childhood separation experience predicts HPA axis hormonal responses in late adulthood: a natural experiment of World War II. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:758–67. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hepgul N, Cattaneo A, Agarwal K, Baraldi S, Borsini A, Bufalino C, et al. Transcriptomics in Interferon-alpha-Treated Patients Identifies Inflammation-, Neuroplasticity- and Oxidative Stress-Related Signatures as Predictors and Correlates of Depression. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;41:2502–11. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fury W, Batliwalla F, Gregersen PK, Li W. Overlapping probabilities of top ranking gene lists, hypergeometric distribution, and stringency of gene selection criterion. Conf Proc. 2006;1:5531–4. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2006.260828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keller MC. Gene x environment interaction studies have not properly controlled for potential confounders: the problem and the (simple) solution. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuen EY, Liu W, Karatsoreos IN, Ren Y, Feng J, McEwen BS, et al. Mechanisms for acute stress-induced enhancement of glutamatergic transmission and working memory. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:156–70. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anacker C, Cattaneo A, Musaelyan K, Zunszain PA, Horowitz M, Molteni R, et al. Role for the kinase SGK1 in stress, depression, and glucocorticoid effects on hippocampal neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:8708–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300886110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maes M, Anderson G, Kubera M, Berk M. Targeting classical IL-6 signalling or IL-6 trans-signalling in depression? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2014;18:495–512. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.888417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bersani FS, Wolkowitz OM, Lindqvist D, Yehuda R, Flory J, Bierer LM, et al. Global arginine bioavailability, a marker of nitric oxide synthetic capacity, is decreased in PTSD and correlated with symptom severity and markers of inflammation. Brain, Behav, Immun. 2016;52:153–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carpenter LL, Gawuga CE, Tyrka AR, Lee JK, Anderson GM, Price LH. Association between plasma IL-6 response to acute stress and early-life adversity in healthy adults. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;35:2617–23. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Becking K, Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, Haarman BC. Riemersma-van der Lek R, Penninx BW et al. The association between immune activation and manic symptoms in patients with a depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e314. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rotter A, Biermann T, Stark C, Decker A, Demling J, Zimmermann R, et al. Changes of cytokine profiles during electroconvulsive therapy in patients with major depression. J ECT. 2013;29:162–9. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3182843942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K, Sen S. The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited: evidence of genetic moderation. Arch General Psychiatry. 2011;68:444–54. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown GW, Ban M, Craig TK, Harris TO, Herbert J, Uher R. Serotonin transporter length polymorphism, childhood maltreatment, and chronic depression: a specific gene-environment interaction. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:5–13. doi: 10.1002/da.21982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fisher HL, Cohen-Woods S, Hosang GM, Korszun A, Owen M, Craddock N, et al. Interaction between specific forms of childhood maltreatment and the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT) in recurrent depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;145:136–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grabe HJ, Lange M, Wolff B, Volzke H, Lucht M, Freyberger HJ, et al. Mental and physical distress is modulated by a polymorphism in the 5-HT transporter gene interacting with social stressors and chronic disease burden. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:220–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T, Liang KY, Eaves L, Hoh J, et al. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. Jama. 2009;301:2462–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duncan LE, Keller MC. A critical review of the first 10 years of candidate gene-by-environment interaction research in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1041–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uher R. Gene-environment interactions in severe mental illness. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:48. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Webb C, Gunn JM, Potiriadis M, Everall IP, Bousman CA. The Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Val66Met Polymorphism Moderates the Effects of Childhood Abuse on Severity of Depressive Symptoms in a Time-Dependent Manner. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:151. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gatt JM, Nemeroff CB, Dobson-Stone C, Paul RH, Bryant RA, Schofield PR, et al. Interactions between BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and early life stress predict brain and arousal pathways to syndromal depression and anxiety. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:681–95. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tabak BA, Vrshek-Schallhorn S, Zinbarg RE, Prenoveau JM, Mineka S, Redei EE, et al. Interaction of CD38 Variant and Chronic Interpersonal Stress Prospectively Predicts Social Anxiety and Depression Symptoms Over Six Years. Clin Psychol Sci. 2016;4:17–27. doi: 10.1177/2167702615577470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lowe SR, Pothen J, Quinn JW, Rundle A, Bradley B, Galea S, et al. Gene-by-social-environment interaction (GxSE) between ADCYAP1R1 genotype and neighborhood crime predicts major depression symptoms in trauma-exposed women. J Affect Disord. 2015;187:147–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang JP, Robinson DG, Gallego JA, John M, Yu J, Addington J, et al. Association of a Schizophrenia Risk Variant at the DRD2 Locus With Antipsychotic Treatment Response in First-Episode Psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:1248–55. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sokolowski M, Ben-Efraim YJ, Wasserman J, Wasserman D. Glutamatergic GRIN2B and polyaminergic ODC1 genes in suicide attempts: associations and gene-environment interactions with childhood/adolescent physical assault. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:985–92. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mamdani M, Williamson V, McMichael GO, Blevins T, Aliev F, Adkins A, et al. Integrating mRNA and miRNA Weighted Gene Co-Expression Networks with eQTLs in the Nucleus Accumbens of Subjects with Alcohol Dependence. PloS One. 2015;10:e0137671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang XW, Yu Y, Gu L. Dehydroabietic acid reverses TNF-alpha-induced the activation of FOXO1 and suppression of TGF-beta1/Smad signaling in human adult dermal fibroblasts. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:8616–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaiser G, Gerst F, Michael D, Berchtold S, Friedrich B, Strutz-Seebohm N, et al. Regulation of forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) by protein kinase B and glucocorticoids: different mechanisms of induction of beta cell death in vitro. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1587–95. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2863-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu MC, Lee DF, Xia W, Golfman LS, Ou-Yang F, Yang JY, et al. IkappaB kinase promotes tumorigenesis through inhibition of forkhead FOXO3a. Cell. 2004;117:225–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mahmud DL, M GA, Deb DK, Platanias LC, Uddin S, Wickrema A. Phosphorylation of forkhead transcription factors by erythropoietin and stem cell factor prevents acetylation and their interaction with coactivator p300 in erythroid progenitor cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:1556–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Essers MA, Weijzen S, de Vries-Smits AM, Saarloos I, de Ruiter ND, Bos JL, et al. FOXO transcription factor activation by oxidative stress mediated by the small GTPase Ral and JNK. EMBO J. 2004;23:4802–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, et al. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–68. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kops GJ, Burgering BM. Forkhead transcription factors: new insights into protein kinase B (c-akt) signaling. J Mol Med. 1999;77:656–65. doi: 10.1007/s001099900050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Feroze-Zaidi F, Fusi L, Takano M, Higham J, Salker MS, Goto T, et al. Role and regulation of the serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 in fertile and infertile human endometrium. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5020–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Di Pietro N, Panel V, Hayes S, Bagattin A, Meruvu S, Pandolfi A, et al. Serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 (SGK1) regulates adipocyte differentiation via forkhead box O1. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:370–80. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Accili D, Arden KC. FoxOs at the crossroads of cellular metabolism, differentiation, and transformation. Cell. 2004;117:421–6. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hoekman MF, Jacobs FM, Smidt MP, Burbach JP. Spatial and temporal expression of FoxO transcription factors in the developing and adult murine brain. Gene Expr Pattern. 2006;6:134–40. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang H, Quirion R, Little PJ, Cheng Y, Feng ZP, Sun HS, et al. Forkhead box O transcription factors as possible mediators in the development of major depression. Neuropharmacology. 2015;99:527–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Magno LA, Santana CV, Sacramento EK, Rezende VB, Cardoso MV, Mauricio-da-Silva L, et al. Genetic variations in FOXO3A are associated with Bipolar Disorder without confering vulnerability for suicidal behavior. J Affect Disord. 2011;133:633–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou J, Liao W, Yang J, Ma K, Li X, Wang Y, et al. FOXO3 induces FOXO1-dependent autophagy by activating the AKT1 signaling pathway. Autophagy. 2012;8:1712–23. doi: 10.4161/auto.21830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Polter A, Yang S, Zmijewska AA, van Groen T, Paik JH, Depinho RA, et al. Forkhead box, class O transcription factors in brain: regulation and behavioral manifestation. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:150–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hope C, Mettenburg J, Gonias SL, DeKosky ST, Kamboh MI, Chu CT. Functional analysis of plasma alpha(2)-macroglobulin from Alzheimer’s disease patients with the A2M intronic deletion. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;14:504–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bottner M, Krieglstein K, Unsicker K. The transforming growth factor-betas: structure, signaling, and roles in nervous system development and functions. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2227–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gomes FC, Sousa Vde O, Romao L. Emerging roles for TGF-beta1 in nervous system development. Int J Dev Neurosci: Off J Int Soc Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:413–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stipursky J, Francis D, Dezonne RS, Bergamo de Araujo AP, Souza L, Moraes CA, et al. TGF-beta1 promotes cerebral cortex radial glia-astrocyte differentiation in vivo. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:393. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stipursky J, Francis D, Gomes FC. Activation of MAPK/PI3K/SMAD pathways by TGF-beta(1) controls differentiation of radial glia into astrocytes in vitro. Dev Neurosci. 2012;34:68–81. doi: 10.1159/000338108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fujita T, Nagayama A, Anazawa S. Circulating alpha-2-macroglobulin levels and depression scores in patients who underwent abdominal cancer surgery. J Surg Res. 2003;114:90–94. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Douxfils J, Lambert S, Mathieu C, Milla S, Mandiki SN, Henrotte E, et al. Influence of domestication process on immune response to repeated emersion stressors in Eurasian perch (Perca fluviatilis, L.) Comp Biochem Physiol Part A. 2014;173C:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kodavanti UP, Andrews D, Schladweiler MC, Gavett SH, Dodd DE, Cyphert JM. Early and delayed effects of naturally occurring asbestos on serum biomarkers of inflammation and metabolism. J Toxicol Environ Health Part A. 2014;77:1024–39. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2014.899171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]