Abstract

Selection arising from social competition over non-mating resources, i.e. resources that do not directly and immediately affect mating success, offers a powerful alternative to sexual selection to explain the evolution of conspicuous ornaments, particularly in females. Here, we address the hypothesis that competition associated with the territoriality exhibited by both males and females in the cichlid fish Tropheus selects for the display of a conspicuous colour pattern in both sexes. The investigated pattern consists of a vertical carotenoid-coloured bar on a black body. Bar width affected the probability of winning in size-matched female–female, but not male–male, contests for territory possession. Our results support the idea that the emergence of female territoriality contributed to the evolution of sexual monomorphism from a dimorphic ancestor, in that females acquired the same conspicuous coloration as males to communicate in contest competition.

Keywords: female competition, social selection, colour pattern, sexual monomorphism, Cichlidae, Tropheus

1. Introduction

The evolution of sexually monomorphic ornaments and armaments is often explained by mutual mate choice or competition for mating opportunities in both sexes [1]. Alternatively, it has been argued that in comparison to sexual selection, competition over non-sexual resources (i.e. other than mates) is more likely to affect both sexes similarly and hence underlie monomorphism in competitive traits [2,3]. While sexually monomorphic traits do not necessarily serve the same functions in males and females [4], several studies have indeed demonstrated correlations between body coloration and dominance in both sexes [5–9]. Yet, competition in non-sexual situations, such as during dominance interactions, can still directly influence mating success [7,8,10,11]. One solution to reduce the ambiguity over the types of benefits gained from competitive success is to study competition outside the breeding season [12]. Or, if no discrete breeding seasons exist for a given taxon, as in the current study, another solution is to examine female competition over resources that do not confer reproductive benefits immediately or over the short-term.

In the cichlid fish genus Tropheus, endemic to Lake Tanganyika, both males and females compete for individual feeding territories and use body colour signals to communicate social status and motivation in competitive and courtship interactions [13]. Spawning takes place in the males' territories; a female will join the male on his territory for several days to weeks, over which time she feeds intensely and then spawns. The female then leaves the male's territory to provide sole maternal mouthbrooding, after which she establishes her own feeding territory, where she remains for the duration of her interbrood interval (several months) [13]. Females compete (with males and females) to establish their own feeding territories, whereas the male-biased sex ratio [14] keeps female competition over mates low. While the quality, i.e. the structure, of a male's territory influences female mate choice [15], the quality of a female's feeding territory does not immediately influence her mating success.

Cichlid lineages basal to Tropheus [16] are sexually dimorphic, with inconspicuous, small and non-territorial females. We hypothesize that the evolution of the male-like phenotypes in female Tropheus is linked to competition for feeding territories. In particular, the trophic specialization on epilithic algae [13] could have promoted territoriality in both sexes [17] and exposed females to selection on traits associated with resource holding potential such as body size [18] or coloration. Here, we test the prediction that the geographically variable, but sexually monomorphic colour patterns of Tropheus influence both female–female and male–male contest competition. The tested colour pattern is the width of the carotenoid-coloured yellow bar on a black body (figure 1), displayed by Tropheus sp. ‘black’ from Ikola, Tanzania. We predicted that bar width could be either negatively or positively correlated with dominance, depending on whether dominance is related to the black, melanin-coloration of the body, or to the yellow, carotenoid-coloration of the bar [19].

Figure 1.

Tropheus sp. ‘black’, population Ikola. Bar width was measured along the lower lateral line (black bar). (Online version in colour.)

2. Material and methods

Territorial contests, in which two fish competed for a territory furnished with a brick structure (electronic supplementary material, figure S1), were staged between approximately size-matched, same-sex opponents (17 male–male and 18 female–female contests; each fish used only once) and videotaped. Winners were identified by continuous occupation of the bricks and the display of dominant coloration (intense black and yellow; electronic supplementary material, figure S2). We scored contest duration (first interaction until establishment of unchallenged dominance) and identity of the winner. Using photographs, the width of the yellow bar (figure 1) was quantified in relation to standard length (SL), both measured to the nearest 1 mm. Relative differences in body size (RSD) between contestants were expressed as (SLfocal fish – SLopponent fish)/(SLfocal fish + SLopponent fish). Relative differences in bar width (RBD) were calculated similarly. Body condition factor (CF) was measured as the residuals from a log(weight) against log(SL) regression and condition factor differences (CFD) between contestants were calculated as CFD = CFfocal fish − CFopponent fish. Body size and bar width were measured from all available fish (n = 77), 70 of which were used in the contest experiment. Additionally, we measured 44 of these fish multiple times over a period of up to approximately 600 days to monitor changes in bar width over time.

Detailed descriptions of experimental procedures and statistical analyses are provided in the electronic supplementary material. Generalized and general linear models were used to test for effects of RBD, RSD and CFD on contest outcome and duration. Analyses were run in R v. 3.1.2.

3. Results

Bar width (scaled by dividing by SL) was not correlated with SL (Pearson's r = −0.05, p = 0.65, N = 77) and slightly bigger in females (36.0% of SL) than in males (34.6% of SL; t = 1.9, p = 0.05, N = 77). Intra-individual variation in bar width over periods of up to approximately 600 days was small compared to among-individual variation (proportion of variance among individuals: ω2 = 0.91; F = 23.77, p < 0.001, N = 44 fish; electronic supplementary material, figure S3).

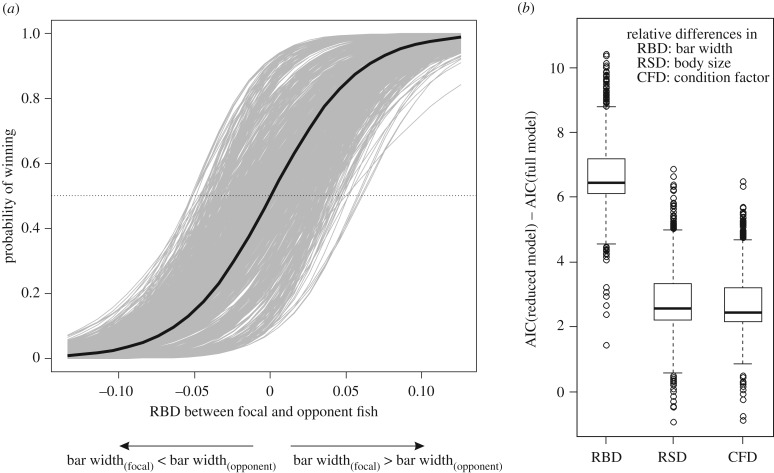

In female–female contests, but not in male–male contests, winners had wider bars than their opponents on average (table 1). Wider bars (i.e. larger RBD) increased the likelihood of winning in female–female contests when controlling for RSD and CFD (figure 2). Body size and condition did not differ significantly between winners and losers in both sexes (table 1).

Table 1.

Differences in bar width (RBD), body size (RSD) and condition (CFD) between winners and losers in female and male contests. β0: intercepts in general linear models with one of the three factors (RBD, RSD or CFD; all mean-centred and scaled) as dependent variable, sex of contestants as predictor and the other two factors as covariates in interaction with sex. *, p < 0.05.

| dependent variable | female contests | male contests | sex difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBD | β0 = 0.039, p = 0.014* | β0 = −0.010, p = 0.517 | p = 0.029* |

| RSD | β0 = 0.004, p = 0.182 | β0 = 0.005, p = 0.126 | p = 0.871 |

| CFD | β0 = 0.002, p = 0.906 | β0 = 0.007, p = 0.683 | p = 0.835 |

Figure 2.

Effect of bar width differences on the probability of winning in female–female contests. (a) The arbitrary designations of contestants as ‘focal’ and ‘opponent’ were randomized to produce 731 permuted datasets. Logistic regression models estimated the effect of RBD on the probability of winning, while accounting for RSD and CFD, for each permuted dataset (grey lines). Black line: mean across the permutated datasets; dotted line: equal probability of winning and losing. (b) Comparison of model AIC values. One factor at a time was dropped from the full model (contest outcome ∼ RBD + RSD + CFD), and boxplots show the variation of ΔAIC in the permuted datasets.

Contest duration (median: 50 s, mean: 106 s, maximum: 927 s) did not differ significantly between the sexes, but was negatively correlated with asymmetries in bar width (i.e. absolute values of RBD) in female–female contests (table 2).

Table 2.

Contest duration in male and female contests. Absolute values of RBD, RSD and CFD represent the extent of asymmetry between contestants in a trial. Non-significant interactions were dropped from the general linear model. Contest duration was square-root-transformed. **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05.

| model: √duration ∼ |RBD| : sex + |RSD| + |CFD| |

estimate (β) | s.e. | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |RBD| : sex | 64.0 | 27.65 | 0.030* |

| |RBD| in female–female contests | −51.0 | 17.97 | 0.009** |

| |RBD| in male–male contests | 13.0 | 19.72 | 0.515 |

| |RSD| | −24.8 | 51.32 | 0.633 |

| |CFD| | 3.0 | 11.73 | 0.798 |

4. Discussion

The contest experiment revealed a competitive advantage for females with wide yellow bars, in terms of both contest outcome and duration, which is consistent with the hypothesis that females acquired their conspicuous coloration for communication in competitive contexts. Given that melanin, i.e. dark, patch size is associated with dominance in some taxa [19,20], a reverse effect of bar width might actually have been expected, as more black is displayed by fish with narrower yellow bars. In several bird species, dominance is predicted by the size of carotenoid-coloured plumage patches and bare parts [5,6,9,21]. Whereas most plumage traits reflect past condition during feather growth, the size of avian bare parts such as shields can dynamically respond to changes in body condition and social environment [21]. In the adult Tropheus ‘Ikola’, the width of the yellow bar, which is associated with variation in melanophore density (electronic supplementary material, figure S4), remained constant over long time intervals and may be determined during maturation and formation of the adult colour pattern [22]. Rather than exposing current condition, both adult colour pattern and physiological performance may be influenced by early-life conditions, as has already been demonstrated in other animals [23,24]. Any link between colour pattern and physiological condition allows contestants to assess each other's fighting ability in order to avoid or curtail dangerous fights [19]. The observed correlations between RBD and both contest outcome and duration, in female–female contests, suggest covariation between bar width and fighting ability. But whether bar width functions as a status signal remains unclear based on current data. Importantly, while bar width is a fixed trait in Tropheus ‘Ikola’, physiological colour changes allow these fish to adjust their colour contrasts quickly, i.e. within seconds, to variation in the social environment. For instance, the yellow bar appears less pronounced and less expansive when a fish is subordinate as opposed to when it is dominant (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). Given communication via physiological modifications of the colour pattern, a signalling function of the morphological variation in bar width is not unlikely.

The phylogenetic background of Tropheus implies an ancestral condition of sexual dimorphism with colourful, territorial males and drab-coloured, non-territorial females [16]. In a previous experiment, body size affected contest outcome equally in both sexes, supporting a role of territorial competition in the evolution of sexual size monomorphism [18]. Although the present study detected no connection between bar width and contest outcome in males, the conspicuous colour pattern might still mediate male competition through variation in intensity and contrast. By identifying a competitive function of the female colour pattern, our study supports the hypothesis that following the transition to female territoriality, competition over a non-mating resource entailed a need for colour-based communication and promoted the expression of male-like colour patterns in female Tropheus. Our empirical data contribute to the longstanding interest in the evolution of female ornamentation and sexual monomorphism in visual showiness [2,3,11,25].

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Bose for valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Ethics

Fish husbandry and behavioural experiments were conducted under permit no. BMWF-66.007/0004-WF/V/3b/2016 issued by the Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy of Austria.

Data accessibility

The datasets supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

K.M.S. conceived the study; A.Z. conducted the experiment; A.Z., K.M.S. and F.R. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved of the final version and agree to be held accountable for the content therein.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

Austrian Science Fund, grant no. P28505-B25 to K.M.S.

References

- 1.Clutton-Brock T. 2009. Sexual selection in females. Anim. Behav. 77, 3–11. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.08.026) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West-Eberhard MJ. 1983. Sexual selection, social competition, and speciation. Q. Rev. Biol. 58, 155–183. ( 10.1086/413215) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarvin KA, Murphy TG. 2014. It isn't always sexy when both are bright and shiny: considering alternatives to sexual selection in elaborate monomorphic species. Ibis 154, 439–443. ( 10.1111/j.1474-919X.2012.01251.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy TG, West JA, Pham TT, Cevallos LM, Simpson RK, Tarvin KA. 2014. Same trait, different receiver response: unlike females, male American goldfinches do not signal status with bill colour. Anim. Behav. 93, 121–127. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.04.034) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crowley CE, Magrath RD. 2004. Shields of offence: signalling competitive ability in the dusky moorhen, Gallinula tenebrosa. Aust. J. Zool. 52, 463–474. ( 10.1071/ZO04013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griggio M, Zanollo V, Hoi H. 2010. Female ornamentation, parental quality, and competitive ability in the rock sparrow. J. Ethol. 28, 455–462. ( 10.1007/s10164-010-0205-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viera VM, Nolan PM, Côte SD, Jouventin P, Groscolas R. 2008. Is territory defence related to plumage ornaments in the king penguin Aptenodytes patagonicus? Ethology 114, 146–153. ( 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2007.01454.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morales J, et al. 2014. Female–female competition is influenced by forehead patch expression in pied flycatcher females. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 68, 1195–1204. ( 10.1007/s00265-014-1730-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaine AS, Tjernell KA, Shizuka D, Lyon BE. 2011. Sparrows use multiple status signals in winter social flocks. Anim. Behav. 81, 447–453. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.11.016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubenstein DR, Lovette IJ. 2009. Reproductive skew and selection on female ornamentation in social species. Nature 462, 786–790. ( 10.1038/nature08614) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clutton-Brock TH, Huchard E. 2013. Social competition and selection in males and females. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 368, 20130074 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0074) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tibbetts EA, Safran RJ. 2009. Co-evolution of plumage characteristics and winter sociality in New and Old World sparrows. J. Evol. Biol. 22, 2376–2386. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01861.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yanagisawa Y, Nishida M. 1991. The social and mating system of the maternal mouthbrooder Tropheus moorii (Cichlidae) in Lake Tanganyika. Jpn. J. Ichthyol. 38, 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sefc KM. 2008. Variance in reproductive success and the opportunity for selection in a serially monogamous species. Hydrobiologia 615, 21–35. ( 10.1007/s10750-008-9563-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermann CM, Brudermann V, Zimmermann H, Vollmann J, Sefc KM. 2015. Female preferences for male traits and territory characteristics in the cichlid fish Tropheus moorii. Hydrobiologia 748, 61–74. ( 10.1007/s10750-014-1892-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer BS, Matschiner M, Salzburger W. 2015. A tribal level phylogeny of Lake Tanganyika cichlid fishes based on a genomic multi-marker approach. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 83, 56–71. ( 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.10.009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant JW. 1993. Whether or not to defend? The influence of resource distribution. Mar. Freshw. Behav. Physiol. 23, 137–153. ( 10.1080/10236249309378862) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Odreitz U, Sefc KM. 2015. Territorial competition and the evolutionary loss of sexual size dimorphism. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 69, 593–601. ( 10.1007/s00265-014-1870-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santos ES, Scheck D, Nakagawa S. 2011. Dominance and plumage traits: meta-analysis and metaregression analysis. Anim. Behav. 82, 3–19. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.03.022) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson AM, Fuller RC. 2014. The meaning of melanin, carotenoid, and pterin pigments in the bluefin killifish, Lucania goodei. Behav. Ecol. 26, 158–167. ( 10.1093/beheco/aru164) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dey CJ, Dale J, Quinn JS. 2013. Manipulating the appearance of a badge of status causes changes in true badge expression. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20132680 ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.2680) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh AP, Nüsslein-Volhard C. 2015. Zebrafish stripes as a model for vertebrate colour pattern formation. Curr. Biol. 25, R81–R92. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2014.11.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Royle NJ, Lindstrom J, Metcalfe NB. 2005. A poor start in life negatively affects dominance status in adulthood independent of body size in green swordtails Xiphophorus helleri. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 1917–1922. ( 10.1098/rspb.2005.3190) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker LK, Stevens M, Karadas F, Kilner RM, Ewen JG. 2013. A window on the past: male ornamental plumage reveals the quality of their early-life environment. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20122852 ( 10.1098/rspb.2012.2852) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amundsen T. 2000. Why are female birds ornamented? Trends Ecol. Evol. 15, 149–155. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01800-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the supplementary material.