Abstract

Aims

In the CHAMPION PHOENIX trial, the potent, rapidly acting, intravenous platelet adenosine diphosphate receptor antagonist cangrelor reduced the 48-h incidence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE; death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, or ischaemia-driven revascularization) compared with a loading dose of clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). We sought to determine whether the efficacy of cangrelor during PCI varies in patients with simple vs. complex target lesion coronary anatomy.

Methods and results

Blinded angiographic core laboratory analysis was completed in 10 854 of 10 942 (99.2%) randomized patients in CHAMPION PHOENIX (13 418 target lesions). Outcomes were analysed according to the number of angiographic PCI target lesion high-risk features (HRF) present (bifurcation, left main, thrombus, angulated, tortuous, eccentric, calcified, long, or multi-lesion treatment). The number of patients with 0, 1, 2, and ≥3 HRFs was 1817 (16.7%), 3442 (31.7%), 2901 (26.7%), and 2694 (24.8%), respectively. The 48-h MACE rate in clopidogrel-treated patients increased progressively with lesion complexity (from 3.3% to 4.4% to 6.9% to 8.7%, respectively, P < 0.0001). Cangrelor reduced the 48-h rate of MACE by 21% {4.7% vs. 5.9%, odds ratio (OR) [95% confidence interval (95% CI)] 0.79 (0.67, 0.93), P = 0.006} compared with clopidogrel, an effect which was consistent regardless of PCI lesion complexity (Pinteraction = 0.66) and presentation with stable ischaemic heart disease (SIHD) or an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). By multivariable analysis, the number of high-risk PCI characteristics [OR (95% CI) 1.68 (1.20, 2.36), 2.78 (2.00, 3.87), and 3.23 (2.33, 4.48) for 1, 2, and 3 HRFs compared with 0 HRFs, all P < 0.0001] and treatment with cangrelor vs. clopidogrel [OR (95% CI) 0.78 (0.66, 0.92), P = 0.004] were independent predictors of the primary 48-h MACE endpoint. Major bleeding rates were unrelated to lesion complexity and were not increased by cangrelor.

Conclusion

Peri-procedural MACE after PCI is strongly dependent on the number of treated high-risk target lesion features. Compared with a loading dose of clopidogrel, cangrelor reduced MACE occurring within 48 h after PCI in patients with SIHD and ACS regardless of baseline lesion complexity. The absolute benefit:risk profile for cangrelor will therefore be greatest during PCI in patients with complex coronary anatomy.

Clinicaltrials.gov identifier:

Keywords: Stent, Complex lesion, Prognosis, Adenosine diphosphate receptor antagonist, Cangrelor, Clopidogrel

Introduction

Peri-procedural complications in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) may be predicted by clinical and angiographic factors, and are associated with a poor short-term and late prognosis.1–7 Pre-procedural inhibition of the platelet adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor with oral ADP receptor antagonists has not been shown to reduce peri-procedural major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in randomized trials.8–10 In contrast, in the double-blind Cangrelor vs. Standard Therapy to Achieve Optimal Management of Platelet Inhibition (CHAMPION) PHOENIX randomized trial, immediate pre-treatment with the potent, rapid-acting intravenous ADP antagonist cangrelor reduced the 48-h incidence of MACE compared with a loading dose of clopidogrel across a broad cross-section of patients undergoing PCI.11 However, few studies have comprehensively examined the relationship between high-risk lesion characteristics and peri-procedural adverse events after PCI, and whether the efficacy of cangrelor during PCI varies according to coronary lesion complexity is unknown. To address these issues, we performed a large-scale, blinded angiographic core laboratory-based analysis examining the relationship between high-risk PCI target lesion features and clinical outcomes from the CHAMPION PHOENIX trial.

Methods

CHAMPION PHOENIX

The design and principal results of the CHAMPION PHOENIX trial have been previously described.11,12 In brief, 11 145 ADP receptor inhibitor-naïve patients with stable ischaemic heart disease (SIHD) or an acute coronary syndrome [ACS; non-ST-segment elevation ACS (NSTEACS); unstable angina or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)] undergoing PCI at 153 international sites were enrolled between September 2010 and October 2012. Major exclusion criteria included treatment with an ADP receptor antagonist or abciximab within 7 days, treatment with eptifibatide, tirofiban, or fibrinolytic therapy within 12 h, uncontrolled hypertension, and impaired haemostasis. Following angiographic confirmation of eligibility, patients were randomized in a double-blind, double-dummy, active-controlled 1:1 ratio to receive a 30 µg/kg bolus of cangrelor followed by a 4 µg/kg/min infusion or a loading dose of 600 mg or 300 mg of clopidogrel prior to or immediately after PCI. Randomization was stratified by clinical syndrome acuity, intended loading dose of clopidogrel (600 mg vs. 300 mg), and site. Study drug infusion (cangrelor or matching placebo) was continued for at least 2 h and up to 4 h post-procedure, after which patients received a loading dose of clopidogrel or matching placebo and were transitioned to maintenance clopidogrel therapy (75 mg po qd). All patients received daily aspirin (75–325 mg) and other guideline-directed medical therapies. Percutaneous coronary intervention was performed using standard techniques and anticoagulation. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were allowed only as rescue therapy during PCI to treat thrombotic complications. The primary efficacy endpoint was the occurrence of MACE within 48 h after PCI, defined as the composite rate of death, myocardial infarction (MI), stent thrombosis, or ischaemia-driven revascularization, as adjudicated by an independent events committee blinded to randomization. The components of the MACE endpoint have been previously defined.11,12 The primary efficacy analysis population was the modified intention-to-treat cohort, defined as all patients undergoing PCI in whom study drug was administered (n = 10 942). The primary safety endpoint was the 48-h rate of severe bleeding not related to coronary artery bypass grafting, according to the Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries (GUSTO) criteria, assessed in the cohort of randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug (n = 11 056). Follow-up continued for 30 days in all patients. The trial was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee at all participating hospitals, and all patients signed informed consent prior to study enrolment.

Angiographic core laboratory analysis

As part of the CHAMPION PHOENIX trial, quantitative and qualitative coronary angiographic analysis (QCA) of all baseline and procedural angiograms was performed at an independent core laboratory (Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York, NY, USA), blinded to treatment assignment and clinical outcomes.13 The following nine target lesion characteristics were pre-specified prior to any data analysis as angiographic high-risk features (HRF): long lesions, left main lesions, bifurcation lesions, thrombotic lesions, tortuous lesions (moderate or severe), angulated lesions (moderate or severe), eccentric lesions, calcified lesions (moderate or severe), and multi-lesion treatment. High-risk features were defined according to the standard definitions of the angiographic core laboratory. Long lesions were defined as length >20 mm by QCA. A qualifying bifurcation lesion had a side branch lesion diameter stenosis ≥50% with reference diameter >1.5 mm within 3 mm of the main branch. Thrombus was defined as a discrete, mobile intraluminal filling defect, with defined borders with or without associated contrast staining, or a total occlusion with convex edges and staining. Tortuosity (proximal to the target lesion) was defined as moderate if one bend >90° or two bends >75°, and severe if two bends >90° or three bends >75°. Lesion angulation was defined as moderate if 45–90° and severe if >90°. An eccentric lesion had only one of its luminal edges compromised by a diameter stenosis >25%. Finally, calcification was defined as moderate if radiopaque densities were noted only during the cardiac cycle and typically involving only one side of the vascular wall, and severe if radiopaque densities were noted without cardiac motion prior to contrast injection and generally involving both sides of the arterial wall.

Statistical methods

Outcomes were analysed according to the number of angiographic HRFs treated (0, 1, 2, or ≥3) in all patients and separately in those with SIHD and ACS. For patients with multiple lesions, the number of HRFs per lesion was summed. Categorical variables were compared by the χ2 test. Continuous variables are summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were compared using ANOVA. Logistic regression was performed to identify the independent predictors of the 48-h MACE primary endpoint. The following variables were entered into the model which in prior studies have been frequently associated with peri-procedural and 30-day adverse events: age, sex, weight, US vs. non-US site, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, current smoker, prior stroke or transient ischaemic attack, prior MI, prior PCI, prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery, history of heart failure, peripheral artery disease, presentation with SIHD vs. ACS, femoral vs. non-femoral access site, planned 300 mg vs. 600 mg clopidogrel loading dose, use of bivalirudin, use of any drug-eluting stent (DES), number of HRFs, and cangrelor vs. clopidogrel randomization. Interaction between the number of HRFs per patient and randomization treatment for the 48-h MACE endpoint was tested using the Breslow–Day method. A two-sided P-value <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients and high-risk features

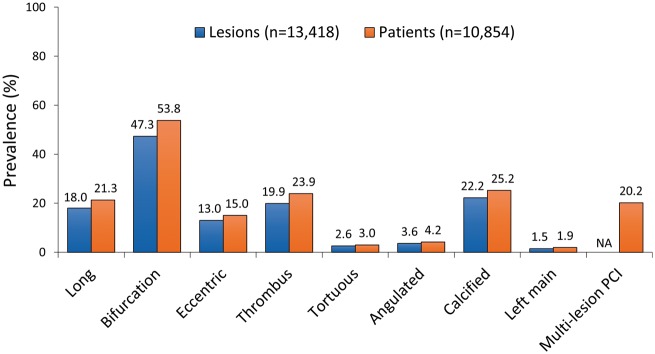

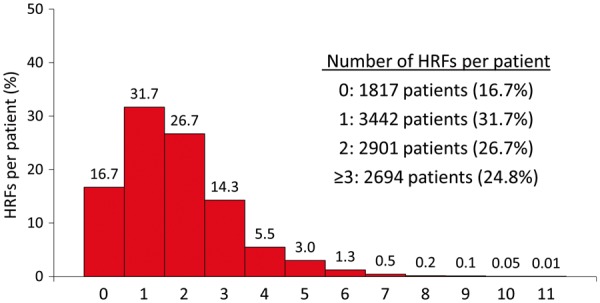

QCA of 13 418 target lesions was performed in 10 854 of 10 942 (99.2%) randomized patients undergoing PCI in CHAMPION PHOENIX. The mean number of HRFs per patient was 1.8 ± 1.4 (range 0–6 per lesion and 0–11 per patient); 1817 (16.7%), 3442 (31.7%), 2901 (26.7%), and 2694 (24.8%) patients had 0, 1, 2, and ≥3 HRFs treated, respectively (Figure 1). The most common high-risk lesion types were bifurcation lesions, calcified lesions, thrombotic lesions, and long lesions (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Histogram of the number of high-risk target lesion features treated per patient. The mean number of high-risk features per patient was 1.8 ± 1.4 [median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) = 2 (1, 2); range 0–11 per patient]. Note: Each treated lesion has no more than nine high-risk features. For patients with more than one treated lesion, the total number of high-risk features is summed for each lesion. Thus, an individual patient with multiple treated lesions may have >9 high-risk features. HRF, high-risk feature.

Figure 2.

Presence (proportion) of qualifying high-risk features in 10 854 patients and in 13 418 lesions. Note: Each lesion has no more than nine high-risk features. For patients with more than one treated lesion, the total number of high-risk features is summed for each lesion. Thus, an individual patient with multiple treated lesions may have >9 high-risk features. Analysis by quantitative and qualitative coronary angiography performed at an independent blinded core laboratory. NA, not applicable.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, medications, and procedural performance according to the number of HRFs treated are shown in Table 1. Patients with greater treated lesion complexity were older, were more frequently male and hyperlipidaemic, were less likely to have prior cardiac procedures and be treated in the USA, more frequently presented with an ACS, and were less likely to be treated with a 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel (or matching placebo) and bivalirudin anticoagulation. Drug-elunting stents use was more common, bailout glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor administration was required more frequently, and procedural duration was longer in procedures with greater HRFs. Randomization to cangrelor vs. clopidogrel was balanced across the HRF groups.

Table 1.

Baseline features according to the number of treated high-risk lesion characteristics

| 0 HRF (Group a) (n = 1817) | 1 HRF (Group b) (n = 3442) | 2 HRF (Group c) (n = 2901) | ≥3 HRF (Group d) (n = 2694) | P-value* | Pairwise comparisons** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.9 ± 11.0 | 62.9 ± 11.1 | 64.2 ± 11.0 | 65.0 ± 10.7 | <0.0001 | b < a,c < d |

| Male | 1274 (70.1%) | 2431 (70.6%) | 2130 (73.4%) | 1990 (73.9%) | 0.0004 | a,b < c,d |

| Weight (kg) | 86.1 ± 18.2 | 85.6 ± 18.0 | 84.9 ± 17.6 | 85.1 ± 17.7 | 0.10 | c < a |

| Treated in USA | 585 (47.2%) | 1270 (36.9%) | 995 (34.3%) | 965 (35.8%) | <0.0001 | c,d < b < a |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Hypertension | 1462/1813 (80.6%) | 2773/3435 (80.7%) | 2257/2892 (78.0%) | 2147/2689 (79.8%) | 0.15 | c,d < a,b |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 1195/1649 (72.5%) | 2106/3046 (69.1%) | 1738/2555 (68.0%) | 1641/2406 (68.2%) | 0.005 | b,c,d < a |

| Diabetes mellitus | 532/1815 (29.3%) | 909/3439 (26.4%) | 788/2896 (27.2%) | 801/2689 (29.8%) | 0.28 | b < c < a,d |

| Current smoker | 466/1773 (26.3%) | 988/3376 (29.3%) | 840/2822 (29.8%) | 721/2620 (27.5%) | 0.59 | a,d < b,c |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 397/1799 (22.1%) | 697/3421 (20.4%) | 578/2880 (20.1%) | 578/2685 (21.5%) | 0.84 | — |

| Prior PCI | 530/1813 (29.2%) | 794/3437 (23.1%) | 614/2896 (21.2%) | 652/2689 (24.2%) | 0.0007 | b,c,d < a |

| Prior CABG | 242/1815 (13.3%) | 338/3437 (9.8%) | 233/2898 (8.0%) | 262/2692 (9.7%) | <0.0001 | c < b,d < a |

| Prior stroke or TIA | 84/1807 (4.6%) | 164/3430 (4.8%) | 138/2896 (4.8%) | 126/2687 (4.7%) | 0.99 | — |

| History of heart failure | 198/1809 (10.9%) | 361/3438 (10.5%) | 303/2893 (10.5%) | 273/2688 (10.2%) | 0.43 | — |

| Peripheral artery disease | 154/1788 (8.6%) | 243/3412 (7.1%) | 217/2880 (7.5%) | 217/2675 (8.1%) | 0.98 | — |

| Presentation | ||||||

| Stable ischaemic heart disease | 1220 (67.1%) | 1999 (58.1%) | 1590 (54.8%) | 1527 (56.7%) | <0.0001 | b,c,d < a |

| NSTEACS | 459 (25.3%) | 944 (27.4%) | 743 (25.6%) | 721 (26.8%) | 0.24 | — |

| STEMI | 138 (7.6%) | 499 (14.5%) | 568 (19.6%) | 446 (16.6%) | <0.0001 | a < b,c < d |

| Randomization | ||||||

| Cangrelor | 899 (49.5%) | 1726 (50.1%) | 1411 (48.6%) | 1390 (51.6%) | 0.29 | c < d |

| Clopidogrel | 918 (50.5%) | 1716 (49.9%) | 1490 (51.4%) | 1304 (48.4%) | 0.29 | d < c |

| Clopidogrel loading dose | ||||||

| 300 mg | 388 (21.4%) | 871 (25.3%) | 770 (26.5%) | 745 (27.7%) | <0.0001 | a < b,c < d |

| 600 mg | 1429 (78.6%) | 2571 (74.7%) | 2131 (73.5%) | 1949 (72.3%) | <0.0001 | d < b,c < a |

| Medications pre/during PCI | ||||||

| Aspirin | 1691/1816 (93.1%) | 3248/3440 (94.4%) | 2745/2898 (94.7%) | 2541/2692 (94.4%) | 0.11 | — |

| Low molecular weight heparin | 252 (13.9%) | 455 (13.2%) | 376/2899 (13.0%) | 398 (14.8%) | 0.32 | — |

| Unfractionated heparin | 1338 (73.6%) | 2704/3441 (78.6%) | 2318 (79.9%) | 2107 (78.2%) | 0.001 | a < b,d < c |

| Bivalirudin | 498/1816 (27.4%) | 769 (22.3%) | 623/2900 (21.5%) | 623 (23.1%) | 0.005 | b,c,d < a |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 16 (0.9%) | 90 (2.6%) | 125 (4.3%) | 149 (5.5%) | <0.0001 | a < b < c < d |

| Access site | ||||||

| Femoral | 1366 (75.2%) | 2515 (73.1%) | 2078 (71.6%) | 2027 (75.2%) | 0.006 | b,c < a,d |

| Radial | 448 (24.7%) | 921 (26.8%) | 816 (28.1%) | 660 (24.5%) | 0.006 | a,d < b,c |

| Brachial | 3 (0.2%) | 6 (0.2%) | 7 (0.2%) | 7 (0.3%) | 0.84 | — |

| PCI device | ||||||

| Drug-eluting stent | 967 (53.2%) | 1868 (54.3%) | 1602 (55.2%) | 1627 (60.4%) | <0.0001 | a, b, c < d |

| Bare metal stent | 749 (41.2%) | 1469 (42.7%) | 1213 (41.8%) | 1154 (42.8%) | 0.47 | — |

| Balloon angioplasty | 103 (5.7%) | 171 (5.0%) | 160 (5.5%) | 129 (4.8%) | 0.39 | — |

| PCI duration (min) | 15.5 ± 14.2 | 19.1 ± 16.1 | 23.4 ± 19.0 | 31.0 ± 23.6 | <0.0001 | a < b<c < d |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; HRF, high-risk feature; NSTEACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

P-value for trend for categorical data, F-test for continuous data.

Denotes statistically significant differences between each pair (P < 0.05 by χ2 test for categorical data, by F-test for continuous data).

Clinical outcomes according to anatomic lesion complexity and randomization

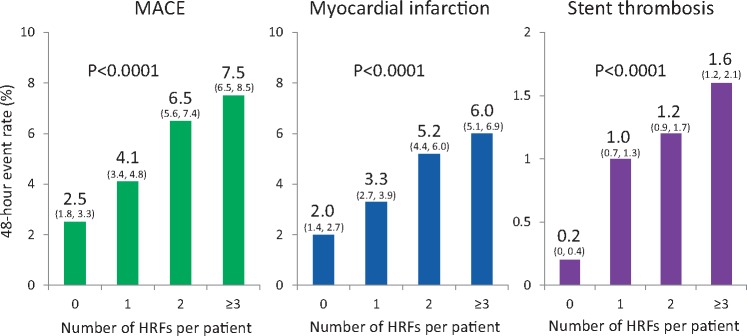

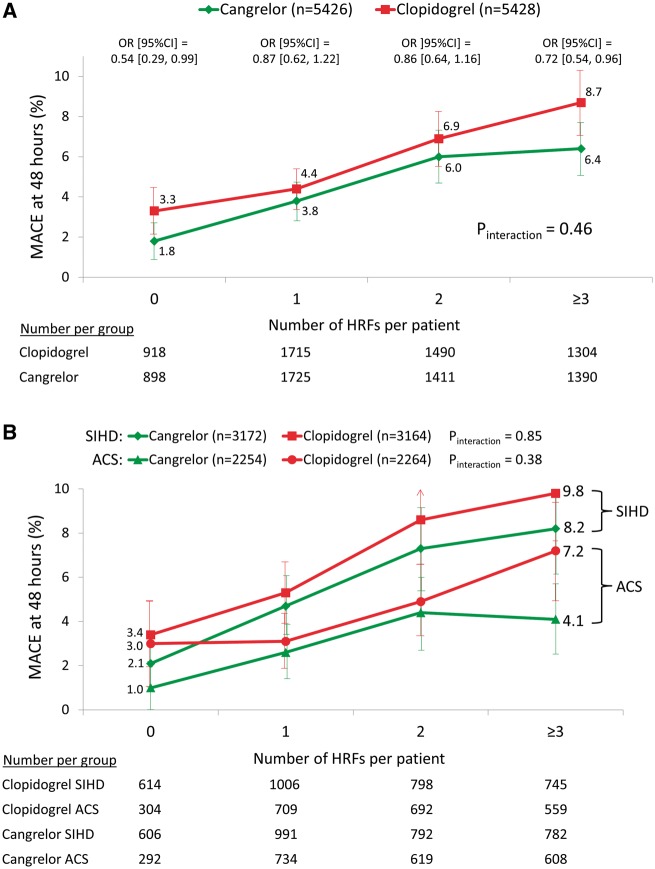

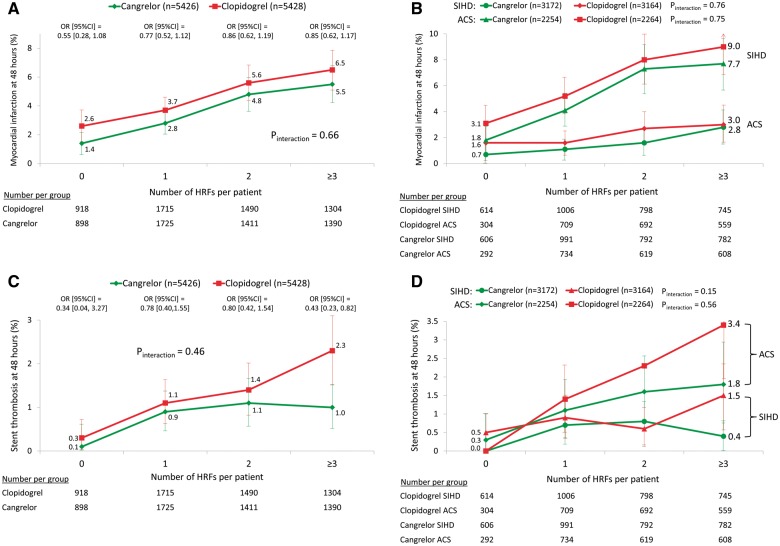

The primary 48-h MACE endpoint increased progressively with PCI target lesion complexity, from 2.5% with 0 HRFs to 7.5% with ≥3 HRFs (P < 0.0001), driven by increases in MI, stent thrombosis and ischaemia-driven revascularization (Table 2 and Figure 3). A similar pattern was observed at 30 days. In the entire patient population, cangrelor reduced the 48-h rate of MACE by 21% [4.7% vs. 5.9%, odds ratio (OR) (95% CI) 0.79 (0.67, 0.93), P = 0.006] compared with clopidogrel. The reduction in 48-h MACE with cangrelor compared with clopidogrel was consistent regardless of PCI lesion complexity and presentation with SIHD or ACS (Figure 4). Cangrelor individually reduced the 48-h rates of MI [3.8% vs. 4.7%, OR (95% CI) 0.80 (0.67–0.97), P = 0.02] and stent thrombosis [1.1% vs. 1.6%, OR (95% CI) 0.67 (0.48–0.94), P = 0.02]. The reductions in MI and stent thrombosis with cangrelor compared with clopidogrel were independent of the number of treated HRFs and clinical syndrome acuity (Figure 5). In post hoc analyses, the results were consistent when analysed according to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) classification,14 baseline reference vessel diameter, number of implanted stents, and total stent length (Supplementary material online, Tables S1–S8).

Table 2.

Major adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events according to the number of treated high-risk lesion characteristics

| 0 HRF | 1 HRF | 2 HRF | ≥3 HRF | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48-h event rates | |||||

| MACE | 46/1816 (2.5%) | 141/3440 (4.1%) | 188/2901 (6.5%) | 202/2694 (7.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Death | 6/1816 (0.3%) | 6/3440 (0.2%) | 15/2901 (0.5%) | 9/2694 (0.3%) | 0.13 |

| Myocardial infarction | 37/1816 (2.0%) | 112/3440 (3.3%) | 151/2901 (5.2%) | 161/2694 (6.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Ischaemia-driven revascularization | 2/1816 (0.1%) | 19/3440 (0.6%) | 27/2901 (0.9%) | 16/2694 (0.6%) | 0.005 |

| Stent thrombosis | 4/1816 (0.2%) | 34/3440 (1.0%) | 37/2901 (1.3%) | 44/2694 (1.6%) | <0.0001 |

| GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding | 7/1849 (0.4%) | 14/3482 (0.4%) | 11/2922 (0.4%) | 718/2712 (0.7%) | 0.33 |

| TIMI major or moderate bleeding | 3/1849 (0.2%) | 6/3482 (0.2%) | 5/2922 (0.2%) | 7/2712 (0.3%) | 0.84 |

| 30-day event rates | |||||

| MACE | 68/1815 (3.7%) | 174/3431 (5.1%) | 231/2894 (8.0%) | 228/2691 (8.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Death | 17/1815 (0.9%) | 30/3431 (0.9%) | 38/2894 (1.3%) | 29/2691 (1.1%) | 0.36 |

| Myocardial infarction | 43/1815 (2.4%) | 119/3431 (3.5%) | 166/2894 (5.7%) | 167/2691 (6.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Ischaemia-driven revascularization | 15/1815 (0.8%) | 31/3431 (0.9%) | 45/2894 (1.6%) | 27/2691 (1.0%) | 0.04 |

| Stent thrombosis | 12/1815 (0.7%) | 47/3431 (1.4%) | 59/2894 (2.0%) | 54/2691 (2.0%) | 0.0005 |

GUSTO, Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries; HRF, high-risk feature; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Figure 3.

Major adverse cardiovascular event rates at 48 h according to the number of high risk features. The 95% confidence intervals for each rate estimate appear in parentheses. HRF, high-risk features; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events.

Figure 4.

Major adverse cardiovascular events at 48 h following randomization to cangrelor vs. clopidogrel according to the number of treated high-risk target lesion features. (A) All patients. The P-value for the trend relating the number of treated high-risk lesion features to the 48-h rate of major adverse cardiovascular events was <0.0001 for both the clopidogrel-treated and cangrelor-treated groups, and the reduction with cangrelor was consistent regardless of target lesion complexity. (B) Further stratified by clinical syndrome acuity at the time of presentation. The reduction in peri-procedural adverse events with cangrelor compared with clopidogrel was consistent regardless of target lesion complexity and clinical presentation. Limit lines for each rate estimate represent 95% confidence intervals. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; HRF, high-risk features; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; SIHD, stable ischaemic heart disease.

Figure 5.

Myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis at 48 h following randomization to cangrelor vs. clopidogrel according to the number of treated high-risk target lesion features. (A) Myocardial infarction, all patients; (B) Myocardial infarction, further stratified by clinical syndrome acuity at the time of presentation. (C) Stent thrombosis, all patients; (D) stent thrombosis, further stratified by clinical syndrome acuity at the time of presentation. Limit lines for each rate estimate represent 95% confidence intervals. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; HRF, high-risk features; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; SIHD, stable ischaemic heart disease.

There were no significant differences after treatment with cangrelor vs. clopidogrel in the entire safety population in the 48-h rates of GUSTO severe or moderate bleeding [0.6% vs. 0.3% respectively, OR (95% CI) 1.63 (0.92–2.90), P = 0.09] or Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) major or minor bleeding [0.3% vs. 0.1% respectively, OR (95% CI) 1.75 (0.73–4.18), P = 0.20], and bleeding complications were unrelated to the number of HRFs (Table 2).

By multivariable analysis, the number of high-risk PCI characteristics, presentation with SIHD vs. ACS, use of a 300 mg vs. a 600 mg clopidogrel loading dose, peripheral artery disease, and treatment with clopidogrel rather than cangrelor were independent predictors of 48-h MACE (Table 3).

Table 3.

Independent predictors of the primary composite endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events at 48 h

| Variable | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Number of HRFs per patient | ||

| 0 (reference) | — | — |

| 1 | 1.68 (1.20, 2.36) | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 2.78 (2.00, 3.87) | <0.0001 |

| ≥3 | 3.23 (2.33, 4.48) | <0.0001 |

| Stratified clopidogrel loading dose (300 mg vs. 600 mg) | 1.47 (1.22, 1.78) | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral artery disease (yes vs. no) | 1.49 (1.13, 1.96) | 0.004 |

| Presentation (SIHD vs. ACS) | 1.84 (1.52, 2.22) | <0.0001 |

| Treatment (cangrelor vs. clopidogrel) | 0.78 (0.66, 0.92) | 0.004 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; HRF, high-risk feature; SIHD, stable ischaemic heart disease.

Discussion

The principal findings from the present study from the CHAMPION PHOENIX trial, to our knowledge the largest blinded angiographic core laboratory analysis to date examining the impact of target lesion characteristics on peri-procedural outcomes after PCI, are: (i) The 48-h rates of MI, stent thrombosis, ischaemia-driven revascularization, and composite MACE increased progressively with the number of target lesion HRFs; (ii) Compared with an oral clopidogrel loading dose at the time of PCI, the rapid-acting, potent intravenous ADP receptor antagonist cangrelor reduced the 48-h rate of MACE by 21%, an effect that was consistent regardless of PCI lesion complexity and presentation with SIHD or ACS; (iii) By multivariable analysis, the number of high-risk PCI lesion characteristics and treatment with cangrelor vs. clopidogrel were independent predictors of the primary 48-h MACE endpoint; and (iv) Peri-procedural major bleeding rates were not related to PCI anatomic complexity, and were not significantly increased by treatment with cangrelor compared with clopidogrel.

Despite the major prognostic implications of peri-procedural complications,1–7 few studies have broadly examined the relationship between the extent of PCI lesion anatomic complexity and peri-procedural MACE, and no prior large-scale studies have employed a blinded angiographic core laboratory analysis to eliminate the potential biases inherent in assigning such correlations. In the present large-scale, international study in which there were few patient and lesion-specific exclusion criteria, DES use was more common, bailout glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor administration was required more frequently, and procedural duration was longer with PCI treatment of lesions with greater HRFs. Anatomic PCI lesion complexity was progressively and strongly associated with the 48-h risk of MACE, including MI, stent thrombosis, and ischaemia-driven revascularization (but not death). This relationship was independent of clinical syndrome acuity, ADP antagonist potency (use of 300 mg vs. 600 mg of clopidogrel or cangrelor), anticoagulation type and DES use, and numerous other baseline risk factors. In clopidogrel-treated patients the 48-h MACE rate ranged from 3.3% after PCI of lesions with no HRFs to 8.7% after PCI of lesions with ≥3 HRFs, a substantial short-term risk emphasizing the ongoing need for improved pharmacologic and device-based approaches to enhance the safety of complex PCI.

Compared with oral clopidogrel loading at the time of PCI, the potent, rapidly acting intravenous agent cangrelor (bolus plus 2-h to 4-h infusion) significantly reduced the 48-h rates of MACE, including MI, stent thrombosis and ischaemia-driven revascularization, independent of presentation with SIHD vs. ACS and the number of PCI lesion HRFs. No significant interaction was present between the relative treatment benefit of cangrelor in reducing these endpoints and the number of PCI lesion HRFs, in all patients and separately in those with SIHD and ACS. Thus, the absolute benefit of cangrelor will be greater as the baseline clinical and anatomic risk of PCI increases. Major adverse cardiac event rates in CHAMPION PHOENIX were higher after PCI in SIHD compared with ACS due to greater rates of peri-procedural MI in SIHD, a finding explainable by challenges in adjudicating PCI-induced myonecrosis in ACS patients in whom baseline biomarker levels are already elevated.15 However, stent thrombosis rates were greater in patients with ACS (as expected),16,17 and steadily increased with the number of PCI target lesion HRFs. The absolute reduction in the 48-h rate of stent thrombosis following treatment with cangrelor compared with clopidogrel was particularly notable after PCI of lesions with ≥3 HRFs [1.0% vs. 2.3%, OR (95% CI) 0.43 (0.23, 0.82)], with 1.6% and 1.1% absolute stent thrombosis reductions in ACS and SIHD respectively. Thus, cangrelor may be of particular benefit during PCI of high-risk lesions in both patients with ACS and SIHD, compared with a clopidogrel loading dose at the time of the procedure. Withholding oral ADP receptor antagonist administration and administering intravenous cangrelor just prior to PCI to ensure complete inhibition of the platelet P2Y12 receptor in patients with unknown coronary anatomy is also consistent with the 2017 focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Task Force.18 Finally, in the present study cangrelor did not increase major bleeding, the risk of which was independent of coronary lesion complexity.

Limitations

Although angiographic core laboratory analysis was pre-specified in the CHAMPION PHOENIX design, the present study was post hoc, and as such its results should be considered hypothesis-generating. Some high-risk lesion types were relatively infrequent; the study was not powered to examine the interaction between individual lesion types, treatments, and outcomes. The angiographic core laboratory definitions were pre-specified, and we did not study every type of high-risk lesion, PCI of some of which may not be affected by potent platelet inhibition (e.g. saphenous vein grafts).19 The proportion of PCI procedures performed by radial vs. femoral access and stent types used in practice may have changed since the performance of CHAMPION PHOENIX. However, by multivariable analysis the number of HRFs and use of clopidogrel rather than cangrelor were independent predictors of MACE after adjusting for these and other factors. The present study did not assess the relationship between the number of HRFs, ADP receptor inhibition, and the specific angiographic complications that may occur (e.g. side branch loss, no reflow, etc.). Such analyses are complicated by the fact that operators do not reliably film all complications. However, we have previously demonstrated that angiographic intraprocedural stent thrombosis is correlated with long and thrombotic lesions and clinical syndrome acuity (frequency greatest with STEMI, intermediate with NSTEACS and least with SIHD); is strongly correlated with subsequent death, MI, ischaemia-driven revascularization and out-of-cath lab stent thrombosis; and is reduced by cangrelor.13 The present study was performed before the SYNTAX score was in wide use; as such, the SYNTAX score was not determined. Finally, the CHAMPION PHOENIX trial compared cangrelor to a clopidogrel loading dose given at the time of PCI and excluded patients pre-loaded earlier or treated with ticagrelor or prasugrel. Such therapies would not likely have reduced the relationship between the number of HRFs and peri-procedural MACE, since this association was independent of cangrelor use. However, pre-loading with more potent ADP receptor antagonists may have attenuated the magnitude of the cangrelor effect observed.

Conclusions

The number of high-risk target lesion features is strongly predictive of peri-procedural MACE in patients undergoing PCI, regardless of clinical syndrome acuity. Compared with a loading dose of clopidogrel in ADP receptor inhibitor-naïve patients, cangrelor reduced MACE occurring within 48 h after PCI, with a greater absolute effect as the number of treated HRFs increased in both SIHD and ACS. Major bleeding occurred infrequently regardless of lesion complexity and was not increased by cangrelor. The absolute benefit:risk profile for cangrelor will therefore be greatest during PCI in patients with complex coronary anatomy.

Funding

The CHAMPION PHOENIX Trial was funded by The Medicines Company, Parsippany, NJ, USA.

Conflict of interest: Dr Stone has served as a consultant to Claret, Ablative Solutions, Matrizyme, Miracor, Neovasc, V-wave, Shockwave, Valfix, TherOx, Reva, Vascular Dynamics, Robocath, HeartFlow and Gore, and holds equity in Aria, the Biostar and Medfocus family of funds, Ancora, Cagent, Qool Therapeutics and Caliber, and is a director of and holds equity in SpectraWave. Dr Généreux has received speaker fees from Abbott Vascular, Cardinal Health, Cardiovascular System Inc., Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Tryton Medical; serves on advisory boards for Boston Scientific, Cardinal Health, Cardiovascular System Inc., Saranas, Sig.num and Soundbites Medical Inc.; is a consultant for Cardiovascular System Inc., Edwards Lifesciences, Pi-Cardia, Medtronic and Soundbites Medical Inc.; is a proctor for Edwards Lifesciences; and owns equity in Pi-Cardia, Soundbites Medical Inc. Saranas and Sig.num. Dr Harrington reports serving as a consultant to or receiving honoraria from Adverse Events, Amgen, Bayer Health Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences, Merck, The Medicines Company, Vida Health, WebMD; serving on data safety and monitoring boards for AstraZeneca, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Janssen; receiving research grants from CSL Behring, Glaxo Smith Kline, Merck, Novartis, Portola, Sanofi-Aventis, The Medicines Company; having equity in Element Science, MyoKardia; being an officer or director for Signal Path, the American heart Association, College of the Holy Cross and Stanford Healthcare. Dr White has received research grants and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, research grants from Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly, National Institute of Health, George Institute, Omthera Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer New Zealand, Intarcia Therapeutics Inc., Elsai Inc., Dal-GenE and research grants and advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Honoraria and lecture fees from Sirtex and Acetilion. Dr Gibson declares serving as the Chief Executive Officer of the Baim Institute for Clinical Research; receiving research/grant funding from Angel Medical Corporation, Bayer Corp., CSL Behring, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson Corporation, and Portola Pharmaceuticals; peer to peer communications with The Medicines Company; serving as a paid consultant to Amarin Pharama, Amgen, Bayer Corporation, Boston Clinical Research Institute, Cardiovascular Research Foundation, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead Sciences, Inc., Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson Corporation, The Medicines Company, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Pharma Mar, Roche Diagnostics, St. Francis Hospital, St. Jude Medical, Web MD; serving as an unpaid consultant to Bayer Corporation, Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Johnson & Johnson Corporation, and Ortho McNeil; and receiving royalties from UpToDate in Cardiovascular Medicine. Dr Steg discloses research grants from Bayer, Merck, Sanofi, and Servier; and speaking or consulting fees from Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer/Janssen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Servier. Dr Hamm has served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim, and has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Lilly, MSD, SanofiAventis, Pfizer, Roche, Novartis, and The Medicines Company. Dr Mahaffey’s financial disclosures can be viewed at http://med.stanford.edu/profiles/kenneth-mahaffey. Dr Price reports consulting honoraria from AstraZeneca, ACIST Medical, Boston Scientific, Terumo, Baylis Medical, Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, W.L. Gore and Associates and The Medicines Company; Proctoring honoraria from Boston Scientific and St Jude Medical; and Speaker’s fees from AstraZeneca, Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, St. Jude Medical and Chiesi USA. Dr Prats was an employee of The Medicines Company at the time of the analysis and reports consulting fees from Chiesi. Dr Deliargyris was an employee of The Medicines Company at the time of the analysis and remains a shareholder. Dr Bhatt discloses the following relationships - Advisory Board: Cardax, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, Medscape Cardiology, Regado Biosciences; Board of Directors: Boston VA Research Institute, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care; Chair: American Heart Association Quality Oversight Committee; Data Monitoring Committees: Cleveland Clinic, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Harvard Clinical Research Institute, Mayo Clinic, Population Health Research Institute; Honoraria: American College of Cardiology (Senior Associate Editor, Clinical Trials and News, ACC.org), Belvoir Publications (Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter), Duke Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committees), Harvard Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committee), HMP Communications (Editor in Chief, Journal of Invasive Cardiology), Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Guest Editor; Associate Editor), Population Health Research Institute (clinical trial steering committee), Slack Publications (Chief Medical Editor, Cardiology Today’s Intervention), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care (Secretary/Treasurer), WebMD (CME steering committees); Other: Clinical Cardiology (Deputy Editor), NCDR-ACTION Registry Steering Committee (Chair), VA CART Research and Publications Committee (Chair); Research Funding: Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chiesi (including for his role as Co-Chair of the CHAMPION trials), Eisai, Ethicon, Forest Laboratories, Ironwood, Ischemix, Lilly, Medtronic, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi Aventis, The Medicines Company (including for his role as Co-Chair of the CHAMPION trials); Royalties: Elsevier (Editor, Cardiovascular Intervention: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease); Site Co-Investigator: Biotronik, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical; Trustee: American College of Cardiology; Unfunded Research: FlowCo, Merck, PLx Pharma, Takeda. The other authors have no relevant disclosures.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

See page 4122 for the editorial comment on this article (doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy506)

References

- 1. Cohen M, Ferguson JJ.. Re-evaluating risk factors for periprocedural complications during percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: who may benefit from more intensive antiplatelet therapy? Curr Opin Cardiol 2009;24:88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lindsey JB, Marso SP, Pencina M, Stolker JM, Kennedy KF, Rihal C, Barsness G, Piana RN, Goldberg SL, Cutlip DE, Kleiman NS, Cohen DJ;. EVENT Registry Investigators. Prognostic impact of periprocedural bleeding and myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention in unselected patients: results from the EVENT (evaluation of drug-eluting stents and ischemic events) registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2009;2:1074–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park D-W, Kim Y-H, Yun S-C, Ahn J-M, Lee J-Y, Kim W-J, Kang S-J, Lee S-W, Lee CW, Park S-W, Park S-J.. Impact of the angiographic mechanisms underlying periprocedural myocardial infarction after drug-eluting stent implantation. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:1105–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Porto I, Di Vito L, Burzotta F, Niccoli G, Trani C, Leone AM, Biasucci LM, Vergallo R, Limbruno U, Crea F.. Predictors of periprocedural (type IVa) myocardial infarction, as assessed by frequency-domain optical coherence tomography. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Babu GG, Walker JM, Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ.. Peri-procedural myocardial injury during percutaneous coronary intervention: an important target for cardioprotection. Eur Heart J 2011;32:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moussa ID, Klein LW, Shah B, Mehran R, Mack MJ, Brilakis ES, Reilly JP, Zoghbi G, Holper E, Stone GW.. Consideration of a new definition of clinically relevant myocardial infarction after coronary revascularization: an expert consensus document from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1563–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McEntegart MB, Kirtane AJ, Cristea E, Brener S, Mehran R, Fahy M, Moses JW, Stone GW.. Intraprocedural thrombotic events during percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes are associated with adverse outcomes. Analysis from the ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:1745–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT, Fry ETA, DeLago A, Wilmer C, Topol EJ.. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:2411–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Widimsky P, Motovská Z, Simek S, Kala P, Pudil R, Holm F, Petr R, Bílková D, Skalická H, Kuchynka P, Poloczek M, Miklík R, Maly M, Aschermann M; PRAGUE-8 Trial Investigators. Clopidogrel pre-treatment in stable angina: for all patients >6 h before elective coronary angiography or only for angiographically selected patients a few minutes before PCI? A randomized multicentre trial PRAGUE-8. Eur Heart J 2008;29:1495–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Montalescot G, Bolognese L, Dudek D, Goldstein P, Hamm C, Tanguay JF, ten Berg JM, Miller DL, Costigan TM, Goedicke J, Silvain J, Angioli P, Legutko J, Niethammer M, Motovska Z, Jakubowski JA, Cayla G, Visconti LO, Vicaut E, Widimsky P; ACCOAST Investigators. Pretreatment with prasugrel in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2013;369:999–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bhatt DL, Stone GW, Mahaffey KW, Gibson CM, Steg PG, Hamm CW, Price MJ, Leonardi S, Gallup D, Bramucci E, Radke PW, Widimský P, Tousek F, Tauth J, Spriggs D, McLaurin BT, Angiolillo DJ, Généreux P, Liu T, Prats J, Todd M, Skerjanec S, White HD, Harrington RA; CHAMPION PHOENIX Investigators. Effect of platelet inhibition with cangrelor during PCI on ischemic events. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1303–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leonardi S, Mahaffey KW, White HD, Gibson CM, Stone GW, Steg GW, Hamm CW, Price MJ, Todd M, Dietrich M, Gallup D, Liu T, Skerjanec S, Harrington RA, Bhatt DL.. Rationale and design of the Cangrelor versus standard therapy to acHieve optimal Management of Platelet InhibitiON PHOENIX trial. Am Heart J 2012;163:768–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Généreux P, Stone GW, Harrington RA, Gibson CM, Steg PG, Brener SJ, Angiolillo DJ, Price MJ, Prats J, Lasalle L, Liu T, Todd M, Skerjanec S, Hamm CW, Mahaffey KW, White HD, Bhatt DL; CHAMPION PHOENIX Investigators. Impact of intraprocedural stent thrombosis during percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the CHAMPION PHOENIX Trial (Clinical Trial Comparing Cangrelor to Clopidogrel Standard of Care Therapy in Subjects Who Require Percutaneous Coronary Intervention). J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ellis SG, Guetta V, Miller D, Whitlow PL, Topol EJ.. Relation between lesion characteristics and risk with percutaneous intervention in the stent and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa era: an analysis of results from 10,907 lesions and proposal for new classification scheme. Circulation 1999;100:1971–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abtan J, Steg PG, Stone GW, Mahaffey KW, Gibson CM, Hamm CW, Price MJ, Abnousi F, Prats J, Deliargyris EN, White HD, Harrington RA, Bhatt DL; CHAMPION PHOENIX Investigators. Efficacy and safety of cangrelor in preventing periprocedural complications in patients with stable angina and acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the CHAMPION PHOENIX Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2016;9:1905–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brodie BR, Garg A, Stuckey TD, Kirtane AJ, Witzenbichler B, Maehara A, Weisz G, Rinaldi MJ, Neumann FJ, Metzger DC, Mehran R, Parvataneni R, Stone GW.. Fixed and modifiable correlates of drug-eluting stent thrombosis from a large all-comers registry: insights from ADAPT-DES. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2015;8:e002568.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fokkema ML, James SK, Albertsson P, Aasa M, Åkerblom A, Calais F, Eriksson P, Jensen J, Schersten F, de Smet BJ, Sjögren I, Tornvall P, Lagerqvist B.. Outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention for different indications: long-term results from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). EuroIntervention 2016;12:303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, Collet J-P, Costa F, Jeppsson A, Jüni P, Kastrati A, Kolh P, Mauri L, Montalescot G, Neumann F-J, Petricevic M, Roffi M, Steg PG, Windecker S, Zamorano JL, Levine GN, Badimon L, Vranckx P, Agewall S, Andreotti F, Antman E, Barbato E, Bassand J-P, Bugiardini R, Cikirikcioglu M, Cuisset T, De Bonis M, Delgado V, Fitzsimons D, Gaemperli O, Galiè N, Gilard M, Hamm CW, Ibanez B, Iung B, James S, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Leclercq C, Lettino M, Lip G, Piepoli MF, Pierard L, Schwerzmann M, Sechtem U, Simpson IA, Uva MS, Stabile E, Storey RF, Tendera M, Van de Werf F, Verheugt F, Aboyans V, Windecker S, Aboyans V, Agewall S, Barbato E, Bueno H, Coca A, Collet J-P, Coman IM, Dean V, Delgado V, Fitzsimons D, Gaemperli O, Hindricks G, Iung B, Jüni P, Katus HA, Knuuti J, Lancellotti P, Leclercq C, McDonagh T, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Richter DJ, Roffi M, Shlyakhto E, Simpson IA, Zamorano JL, Windecker S, Aboyans V, Agewall S, Barbato E, Bueno H, Coca A, Collet J-P, Coman IM, Dean V, Delgado V, Fitzsimons D, Gaemperli O, Hindricks G, Iung B, Jüni P, Katus HA, Knuuti J, Lancellotti P, Leclercq C, McDonagh T, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Richter DJ, Roffi M, Shlyakhto E, Simpson IA, Zamorano JL, Roithinger FX, Aliyev F, Stelmashok V, Desmet W, Postadzhiyan A, Georghiou GP, Motovska Z, Grove EL, Marandi T, Kiviniemi T, Kedev S, Gilard M, Massberg S, Alexopoulos D, Kiss RG, Gudmundsdottir IJ, McFadden EP, Lev E, De Luca L, Sugraliyev A, Haliti E, Mirrakhimov E, Latkovskis G, Petrauskiene B, Huijnen S, Magri CJ, Cherradi R, Ten Berg JM, Eritsland J, Budaj A, Aguiar CT, Duplyakov D, Zavatta M, Antonijevic NM, Motovska Z, Fras Z, Montoliu AT, Varenhorst C, Tsakiris D, Addad F, Aydogdu S, Parkhomenko A, Kinnaird T;. ESC Scientific Document Group; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG); ESC National Cardiac Societies . 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: the Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2018;39:213–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harskamp RE, Hoedemaker N, Newby LK, Woudstra P, Grundeken MJ, Beijk MA, Piek JJ, Tijssen JG, Mehta RH, de Winter RJ.. Procedural and clinical outcomes after use of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor abciximab for saphenous vein graft interventions. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2016;17:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.