Abstract

The Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) are popular both as an alternative protein source and as a model of choice for scientific research in several disciplines. There is limited published information on the histological features of the intestinal tract of Japanese quail. The only comprehensive reference is a book published in 1969. This study aims to fill that niche by providing a reference of general histological features of the Japanese quail, covering all the main sections of the intestinal tract. Both light and scanning electron microscope (SEM) images are presented. Results showed that the Japanese quail intestinal tract is very similar to that of the chicken with the exception of the luminal koilin membrane of the gizzard. Scanning electron microscopic photomicrographs show that in the Japanese quail koilin vertical rods are tightly packed together in a uniform manner making a carpet-like appearance. This differs in chicken where the conformations of vertical rods are arranged in clusters.

Keywords: Japanese quail, Coturnix japonica, Histology, Microscopy, Scanning electron microscopy, Gastrointestinal tract

1. Introduction

The Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) is native to the Indo-China continental region including Japan. Domestication of the species was first documented in the 11th century in China. Japanese quail was originally acquired as songbirds and the consumption of the bird and their eggs arose in the early 19th century (Howes, 1964). By 1940, a thriving industry was established in Japan where linages were selected for egg and meat production. This industry was almost destroyed during the Second World War which resulted in the loss of almost all song-line birds. However, the industry was revived from remaining survivors in the post-war period (Howes, 1964, Wetherbee, 1961).

At present Japanese quail farming is expanding on a global scale providing an alternative protein source that is inexpensive, requires simple husbandry practises, and delivers rapidly maturing progeny capable of breeding at 6 weeks of age and producing up to 10 generations per year. These qualities have also made Japanese quail a popular model species for scientific studies (Kocamis et al., 2013, Rundfeldt et al., 2013, Waligora-Duprieta et al., 2009, Young and Jefferies, 2013). Being of small size they require little space and can be reared in common or non-specialised laboratory equipment such as mouse/rat isolators. They are independent from hatch due to their ability to seek food sources themselves and are quite adaptable to coping in a wide range of husbandry conditions. Newly hatched birds are considered sterile and are ideal models for germ-free, gnotobiotic experiments (Sacksteder, 1960) and epigenetic studies.

Japanese quail are considered a migratory game bird belonging to the order Galliformes, family Phasianidae and are a subspecies of the European or common quail (Coturnix coturnix). A wild Japanese quail weighs between 90 and 100 g, domesticated birds weighs between 150 and 200 g (Raji et al., 2014), and commercially bred meat birds can weigh up to 350 g.

Females are slightly larger than males and plumage of both sexes is typically a cinnamon brown in colour. Females have dark coloured spots on pale feathers on the breast, while males have even-toned dark breast feathers with the same colouring present on the cheeks.

Although the intestinal histology of Japanese quail has been used as an investigation method in numerous experiments (Berg et al., 2001, Grote et al., 2008, He et al., 2014, Rodler and Sinowatz, 2013, Sinclair et al., 2012, Simova-Curd et al., 2013), there are very few references pertaining to the general histological features of the healthy Japanese quail intestinal tract. The only comprehensive information can be found in a book by Theodore C. Fitzgerald which contains comprehensively illustrated hand drawn histological images with explanation of features. The book titled The Coturnix quail – Anatomy and Histology was published in 1969 to supplement the rising popularity of the use of Japanese quail within research fields.

We aim to compliment and expand on the information available in the above book by presenting a selection of histological images of palate, tongue, oesophagus, proventriculus, gizzard, duodenum, jejunum, ileum and caecum of the healthy Japanese quail intestinal tract from both light and scanning electron microscopy. This study aims to assist researchers by providing a visual reference for the ultrastructure of the normal quail gastrointestinal tract.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal ethics statement

All samples were from birds used in experiments approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Central Queensland University (approval number: A14/03-309).

2.2. Animal trial

Fertilised Japanese quail eggs were donated by a commercial supplier, Banyard Game Birds farm, Toowoomba, Queensland. The birds were hatched and grown as previously described (Wilkinson et al., 2016). Briefly, 22 hatchlings were placed together in a brooding pen until 3 weeks of age and then were rehoused individually in cages in a temperature controlled room (25 °C). Birds were exposed to natural lighting conditions and food and water were supplied ad libitum. At hatch, feed supplied was a commercial turkey starter (Barastoc, Ridley, Melbourne, Australia) and at 4 weeks of age, this feed was replaced with a turkey grower (Barastoc, Ridley, Melbourne, Australia) (Table 1). The birds were culled at 8 weeks old at which stage they exceeded expected adult quail weight and performed within the industry standard for quail (Raji et al., 2014) and female birds achieved average weight of 345 g and male 294 g (Wilkinson et al. 2016).

Table 1.

Barastock diet composition (Ridley Melbourne, Australia).

| Item | Starter | Grower |

|---|---|---|

| Protein, % | 22 | 20 |

| Fat, % | 2.5 | 2 |

| Fibre, % | 5 | 6 |

| Salt, % | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Calcium, % | 1 | 0.95 |

| Copper, mg/kg | 8 | 8 |

| Selenium, mg/kg | 0.3 | 0.3 |

2.3. Sample collection and microscopy

All birds were euthanized by intravenous injection of pentobarbitone sodium. Samples were collected from the mouth (palate), tongue, oesophagus, proventriculus, gizzard, duodenum, jejunum, ileum and caecum.

All samples were obtained within 1 h of sacrifice and washed in phosphate-buffered saline and stored in 10% buffered neutral formalin until processed at 20 °C. For light microscopy, stored tissues were cut to appropriate dimensions, placed in plastic cassettes and processed in an automated processing device overnight (Tissue-Tek V.I.P. Tissue processor).

For light microscopy, sections of 5 μm were prepared on a Leica (RM 2125 RTS) microtome. The sections were stained using Haematoxylin-Eosin. Slides were imaged at the TRI Microscopy core facility (Brisbane) using a Nikon Brightfield, Olympus VS120 slide scanner and analysed using Olympus microscopy software named Olivia.

For SEM micrographs, a scanning electron microscope (JEOL SEM JSM6360LA) using a 5 mm working distance, and accelerating voltage of 5 to 10 kV in secondary electron detection mode, was used to view the samples of interest. All scanning electron microscope (SEM) images were prepared as previously detailed (Skrzypek et al., 2005). Samples stored in 10% buffered formalin were sectioned in approximately 5 mm squares and dehydrated using increasing concentrations of ethanol 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90% and 100% for 1 min each as per the method described by Chapman and Regan (2011). Specimens were then mounted on aluminium stubs using carbon glue tabs. Caecal samples were coated with gold–palladium electroplating (60 s, 1.8 mA, 2.4 kV) using a Polaron SEM Coating System sputter coater (Polaron, SC5-15).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Palate

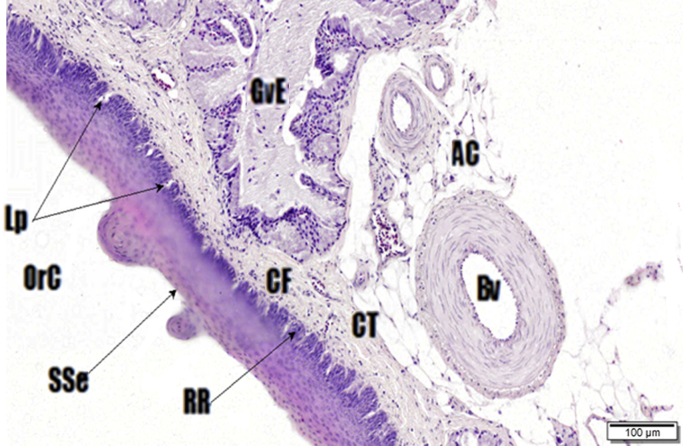

The lamina epithelia mucosa of the roof of the mouth is composed of a stratified squamous epithelium and has numerous caudally pointing papillae (Fig. 1) that can be seen with the naked eye. Microscopic protrusions are also present in places of high abrasion zones along the palatine. The papillae are composed of a keratinized material that has undergone cornification, similar to the nails of mammals (Fig. 2). The papillae are also present on the tongue and function as an aid to swallowing food. The palatine glands are numerous throughout the palatine and are concentrated both medially and laterally. The longitudinal rows consist of numerous small lobules that crowd the palatine epithelium in some areas where they replace the parenchyma with a lobular capsule (Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph of papillae within the palatine ridge.

Fig. 2.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph of an individual keratinized papillae found on the palatine ridge of the palate.

Fig. 3.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph of the palatine glands structurally consisting of longitudinal rows of 12 to 15 small lobules.

Fig. 4.

Oral cross-sectional view of the palate. Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain. The oral (OrC) surface of the palate, stratified squamous epithelia (SSe), Rete ridges (RR), collagen fibre bundles (CF), connective (CT) and adipose tissue (AC), Von Ebners glands (GvE), blood vessel (Bv) and lamina propria (Lp).

3.2. Tongue

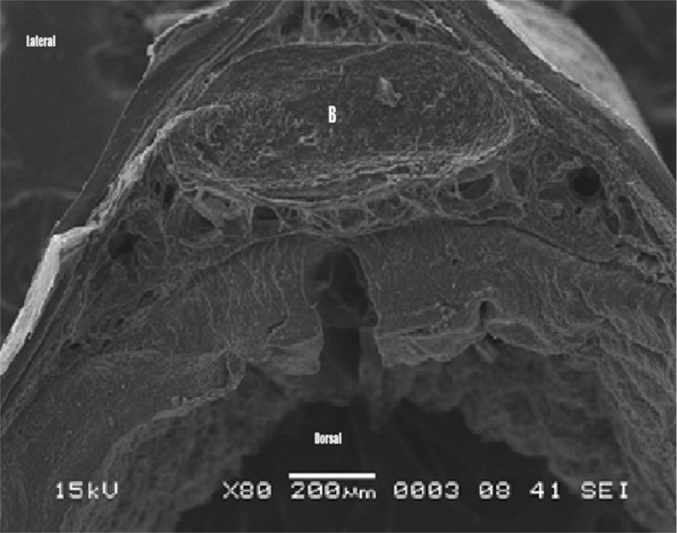

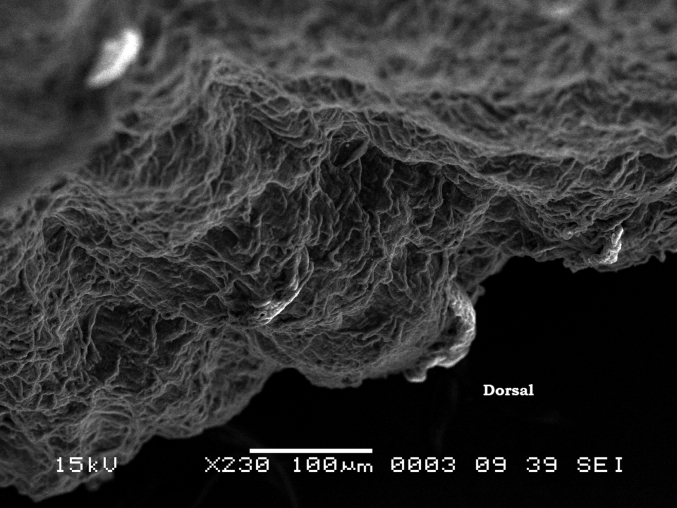

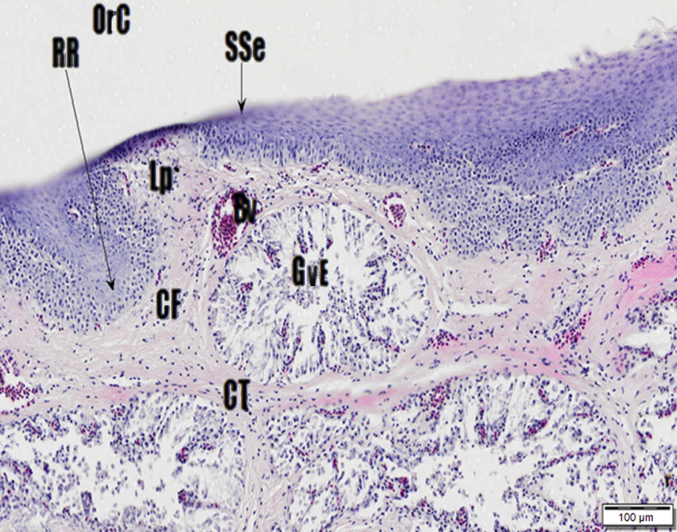

The tongue of the Japanese quail is about 1 cm long and is a triangular shape being widest at the root and tapering to the tip (Fig. 4). The tongue contains very little muscle and is supported by the entoglossum bone that runs in the ventral midline along the length of the tongue (Fig. 5). The lingual surface slants into a “v” shape consisting of 2 lateral surfaces that are ventromedial. The entoglossum is surrounded in layers of a firm connective tissue within the entire surface of tongue with cornification prevalent at the apex and the presence of caudally directed papillae evident at the root. Fig. 6 shows the carpet-like ridges of the middle area of the quail tongue with mucous glands incorporated within the epithelium. The dorsal surface of the tongue consists of a keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The mucosa is comprised of firm connective tissue, collagen fibres embedded with numerous salivary glands called Von Ebner glands (Fig. 7) supported by cartilage and the entoglossum bone. No taste buds were seen and none have been reported on the Japanese quail tongue (Fitzgerald, 1969).

Fig. 5.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph of a mid-sectional view of the tongue showing the entoglossum bone (B) that runs in the ventral midline along the length of the tongue.

Fig. 6.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph of the dorsal surface of tongue.

Fig. 7.

Cross section of dorsal surface of the tongue. Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain. Connective tissue (CT) and collagen fibres (CF), Von Ebner glands (GvE), stratified squamous epithelium (SSe), oral cavity (OrC), blood vessels (Bv), lamina propria (Lp) and Rete ridges (RR).

3.3. Oesophagus

The oesophagus is an approximately 7.5 cm long muscular-membranous tube that has the capacity to distend to allow the passage of a large bolus of food. The structure of the oesophagus consists of numerous longitudinal mucosal folds (Fig. 8) which allow abundant flexibility and elasticity. The luminal surface of the lamina is composed of a thick stratified squamous epithelium that is keratinized on the surface layer. The characteristic longitudinal folds are formed by the muscularis mucosa consisting of a continuous sheet of longitudinal fibres (Fig. 9). The muscularis externa is very thin and is intertwined with embedded elastic connective tissue.

Fig. 8.

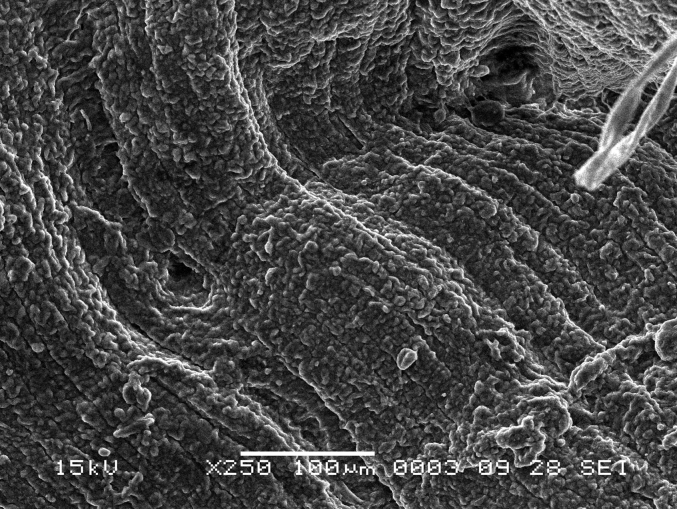

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph of oesophagus showing the longitudinal mucosal folds, composed of a thick layer of stratified squamous epithelium.

Fig. 9.

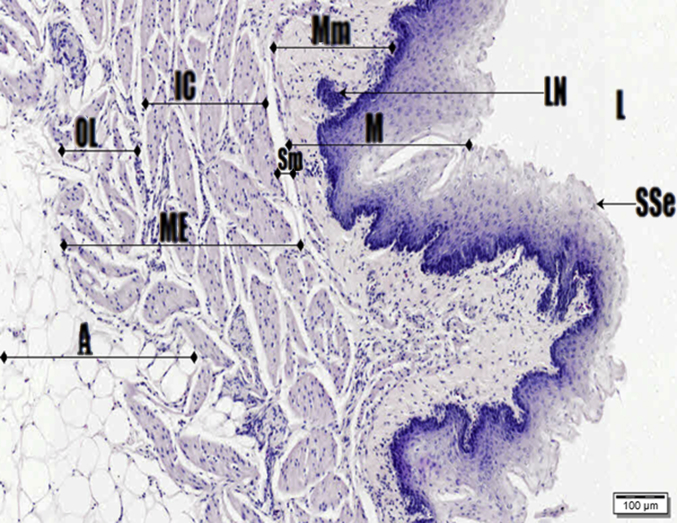

Photomicrograph of oesophagus. Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain. Stratified squamous epithelium (SSe), muscularis mucosa (Mm), mucosa (M), lymph nodules (LN), muscularis externa (ME), inner circular (IC) and outer longitudinal (OL) muscle tissue, lumen (L), submucosa (Sm) and adventitia with adipose cells.

The oesophagus is classified into 3 main sections: cervical, crop and thoracic. The crop is a flexible out-pocket that is present in birds as a means of providing food storage and allows for continuous digestion. The structure of the crop is similar to oesophagus, mucosal folds are not as high and the lamina epithelium is thicker and contains some superficial cornification (Fitzgerald, 1969).

3.4. Proventriculus

The avian stomach includes 2 distinct sections. The proventriculus is the glandular portion of the avian equivalent of the mammalian stomach and is the site where digestion begins. This organ secretes hydrochloric acid, enzymes and mucus in order to begin the process of digestion of food particles. The introduction of the gastric juices rapidly lowers the pH of the ingested food particles and doubles as a defence against pathogenic invasion (Samar et al., 2002). Fig. 10 shows the carpet-like appearance of luminal epithelium that is saturated with secretory glands. The bulk of the proventriculus is made up of a longitudinal muscular glandular wall with the outer surface of the organ covered with a visceral peritoneum (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph showing the luminal surface of proventriculus.

Fig. 11.

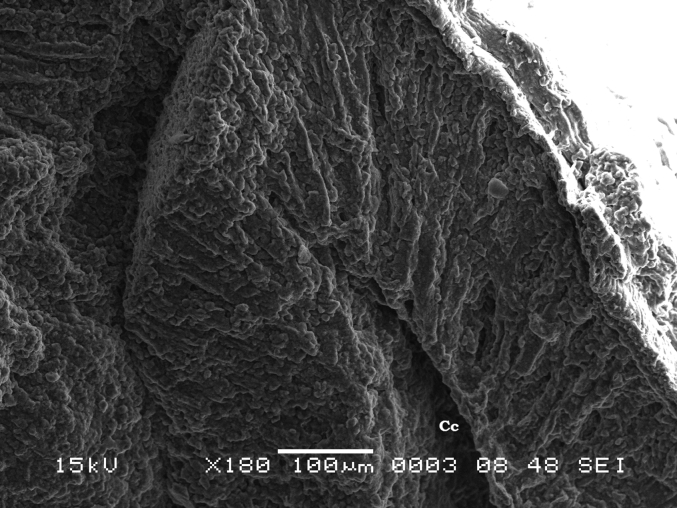

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph showing cross-sectional view of the proventriculus showing the proventricular gland with the central cavity (Cc).

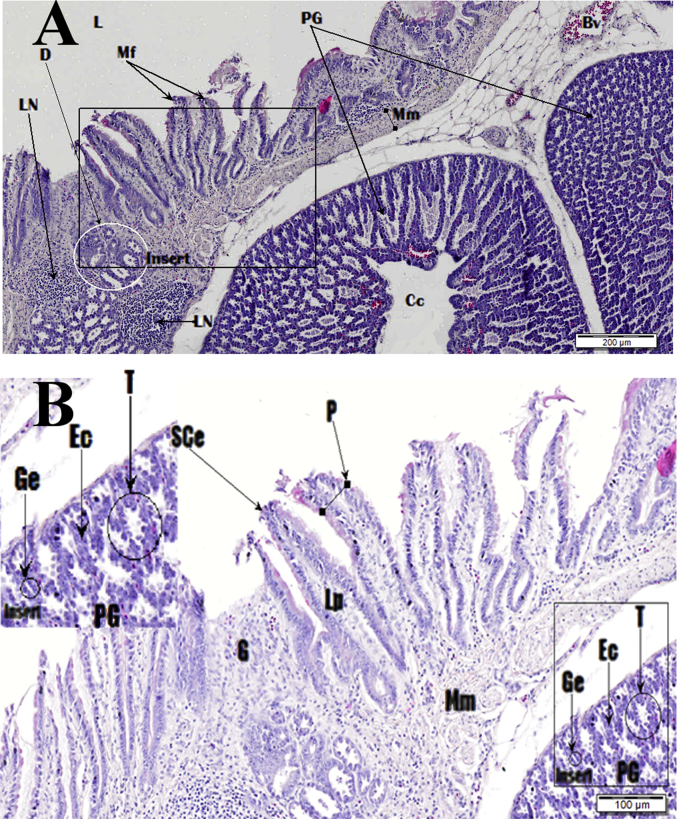

The star shaped lumen has a diameter only slightly larger than that of the thoracic oesophagus. The luminal surface is comprised of simple columnar epithelium. The muscularis mucosa is quite thin and embedded with lymph nodes, connective tissue and numerous mucous ducts with the epithelial surface forming mucosal folds or papillae that project into the lumen (Fig. 12). The bulk of this organ is its thick muscular glandular wall. The proventricular glands are in a circular arrangement around the lumen in 2 to 3 layers and are individually separated by a connective tissue. The proventricular gland consists of a central cavity (Fig. 11, Fig. 12) with numerous secretory tubules lined with endocrine and glandular epithelium. Both enzymes and hydrochloric acid are produced in these secretory vesicles while mucus is generated within glands in the muscularis mucosa.

Fig. 12.

Photomicrograph of proventriculus. Image B is zoomed in insert section shown in image A. Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain. Lumen (L), muscularis mucosa (Mm), lymph nodes (LN) and mucous ducts (D), mucosal folds (Mf), proventricular glands (PG), central cavity (Cc), blood vessel (Bv), simple columnar epithelium (SCe), papillae (P), secretory tubules (T), endocrine cells (Ec), glandular epithelium (Ge), lamina propria (LP).

3.5. Gizzard

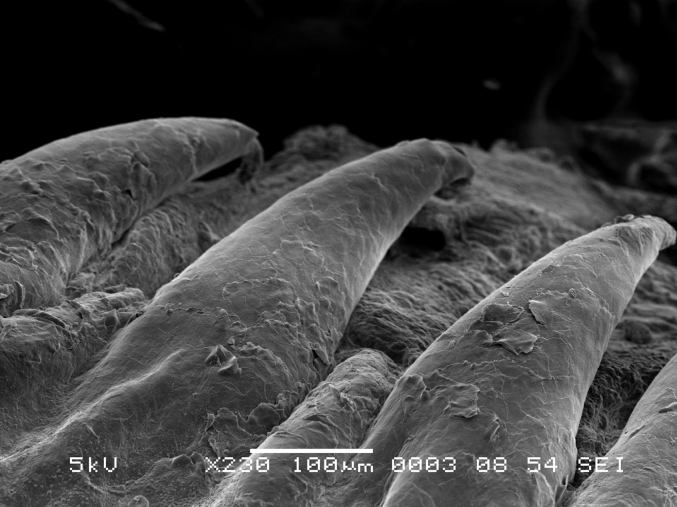

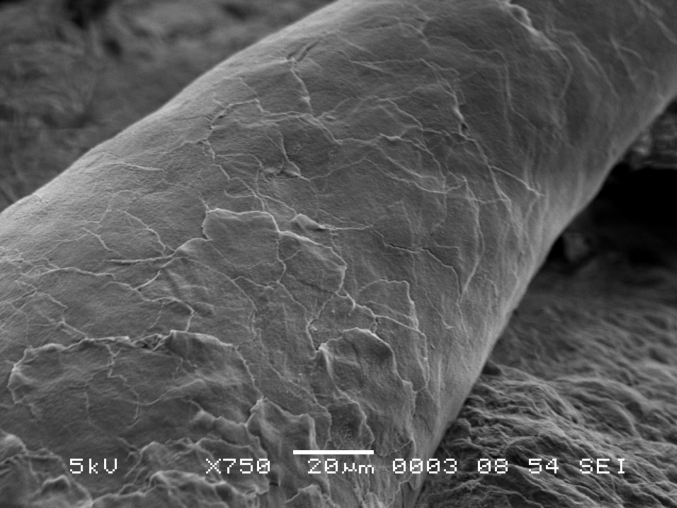

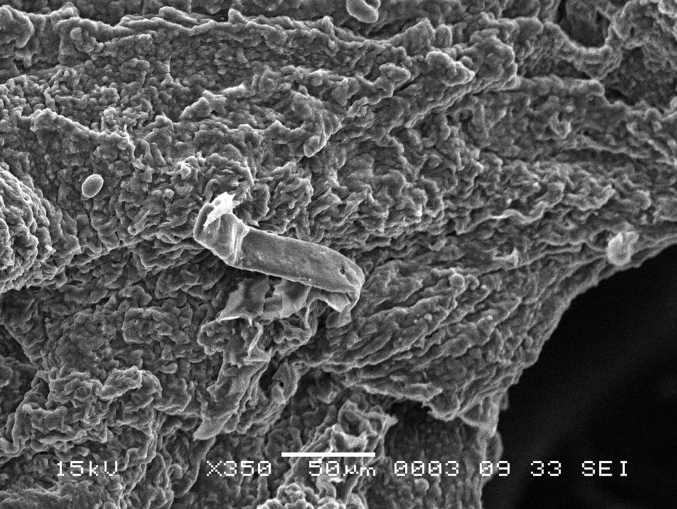

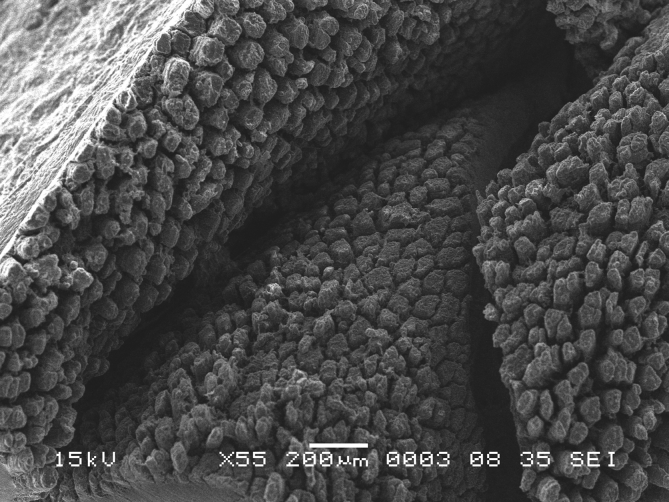

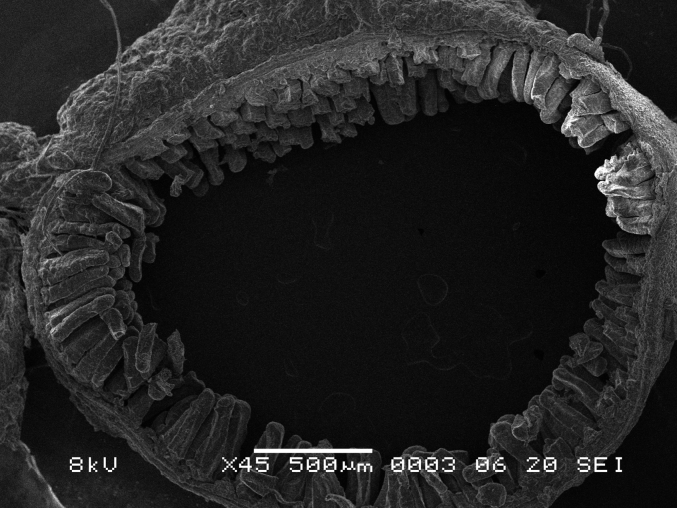

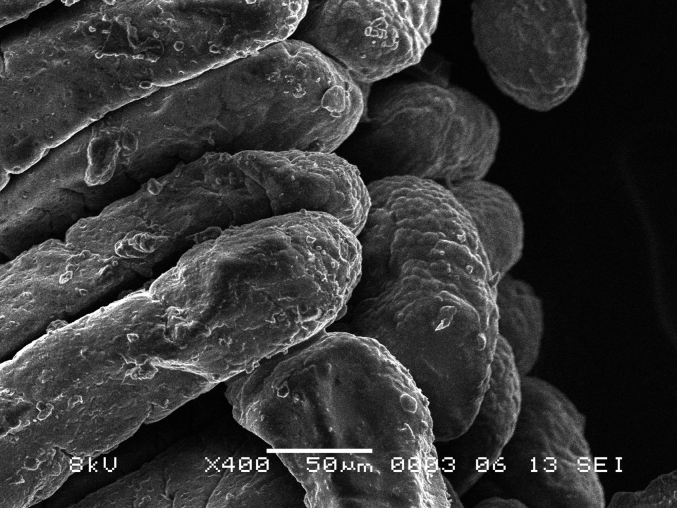

The gizzard is a muscular pouch that runs caudally to the proventriculus and is considered the second part of the avian stomach. This is where the mechanical process of grinding of food particles to a refined composition takes place which allows for superior nutrient extraction. The luminal surface of the gizzard is coated with a hard layer called the koilin membrane or pellicle. The koilin membrane is the secretory product of numerous mucosal glands that are classified as a simple branched tubular type and form clusters of secretions forming a uniform pattern on the gizzard luminal surface (Fig. 13, Fig. 14).

Fig. 13.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph showing the luminal surface of the gizzard.

Fig. 14.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph showing magnified view of koilin rods of found on the luminal surface of the gizzard.

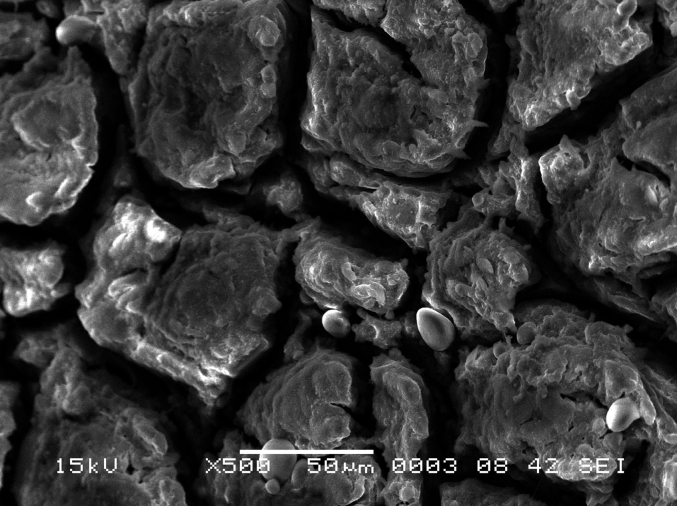

The luminal glandular epithelium of the mucous membrane is composed of simple columnar cells that continue to become thick tubular glands (Fig. 15). There is an absence of the muscularis mucosa which results in the lamina propria becoming inseparable from the submucosa. The bulk of the gizzard is composed of a thick smooth muscular circular layer that is intertwined heavily with collagen fibre bundles and connective tissue.

Fig. 15.

Photomicrograph of the gizzard. Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain. Lumen (L) thick smooth muscular circular layer (MT), connective tissue (CT), lamina propria (Lp), submucosa (Sm), cuticle (K), mucosal glands (Mg), glandular epithelium (Ge) and tunica propria (Tp).

3.6. Small intestine

Ground food particles progress from the gizzard into the intestinal tract where further digestion and nutrient extraction occurs. The complete intestine, from the gizzard to the cloaca, is approximately 50 to 52 cm in length (Fitzgerald, 1969). The small intestine is classified into 3 sections: duodenum, jejunum and ileum (Fig. 16, Fig. 17, Fig. 18, Fig. 19, Fig. 20, Fig. 21, Fig. 22).

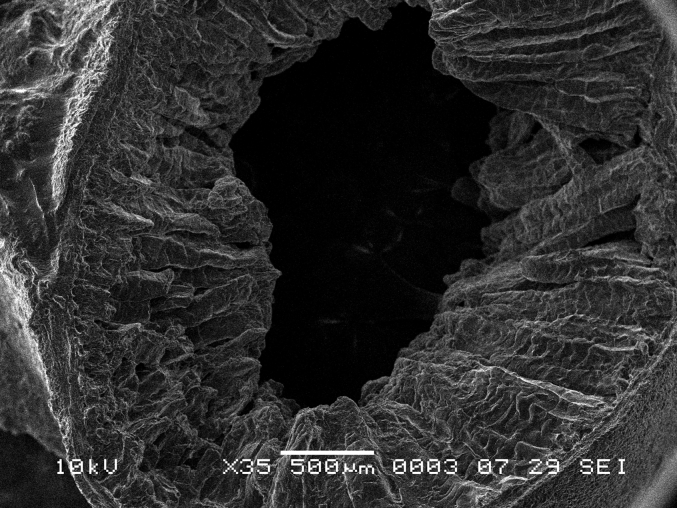

Fig. 16.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph showing a cross sectional view of the duodenum.

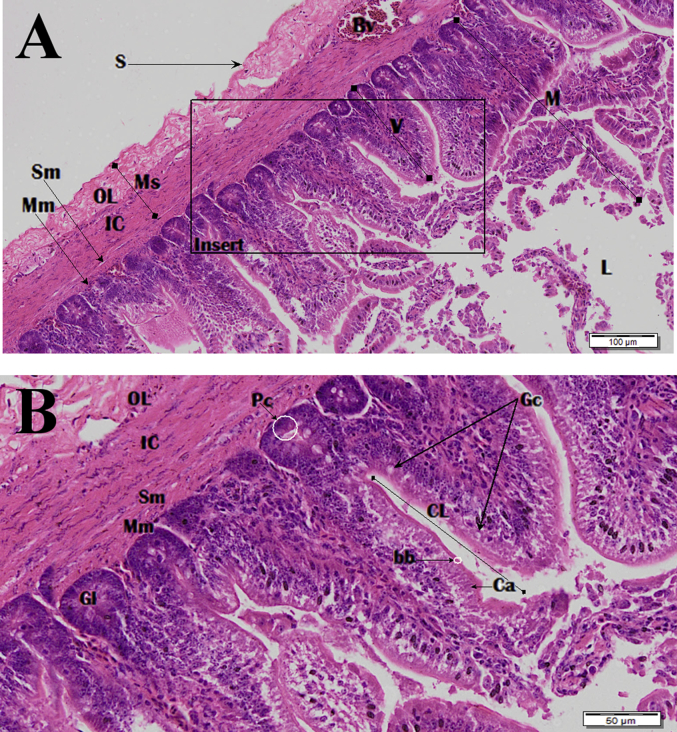

Fig. 17.

Photomicrograph of the duodenum. Image B is zoomed insert section shown in image A. Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain. Lumen (L), villi (V), mucosa (M), submucosa (Sm), muscularis mucosa (Mm), muscularis externa, serosa (S) and blood vessel (Bv), inner circular (IC) and the outer longitudinal (OL) muscularis externa, simple columnar epithelial cells (Ca), goblet cells (Gc), brush border (bb), crypts of Lieberkuhn (CL), glands of Lieberkuhn (GL) paneth cells (Pc).

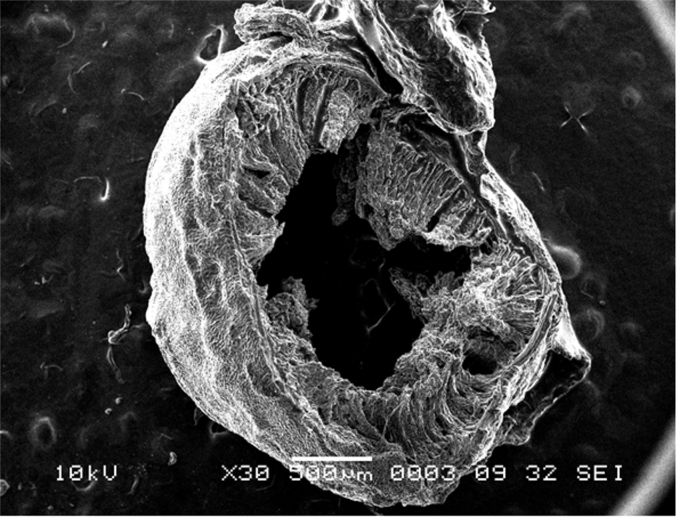

Fig. 18.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph showing a cross sectional view of the jejunum.

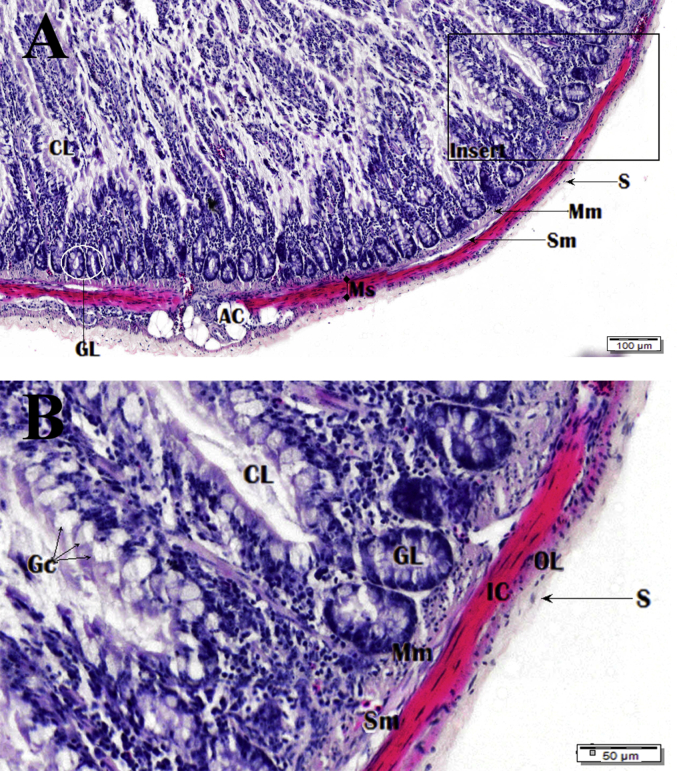

Fig. 19.

Photomicrograph of jejunum. Image B is zoomed insert section shown in image A. Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain. Goblet cells (Gc), crypts of Lieberkuhn (CL), glands of Lieberkuhn (GL), muscularis mucosa (Mm), submucosa (Sm), muscularis externa (Ms), inner circular muscle (IC), outer longitudinal muscle (OL), serosa (S) and adipose cells (AC).

Fig. 20.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph showing a cross sectional view of the ileum.

Fig. 21.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph showing magnified view of individual villi of the ileum.

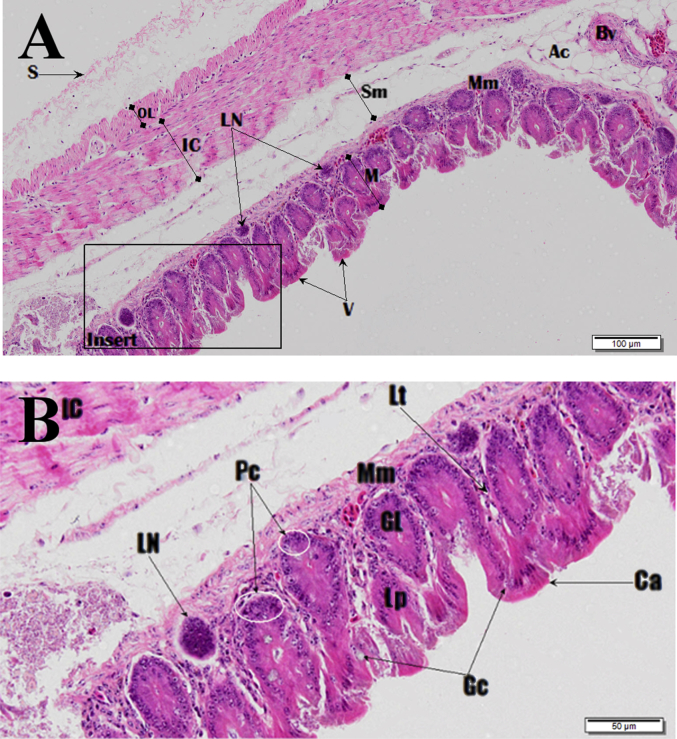

Fig. 22.

Photomicrograph of the ileum. Image B is zoomed insert section shown in image. Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain. Villi(V), simple columnar epithelia (Ca), Goblet cells (Gc), the crypts of Lieberkuhn (CL), Glands of Lieberkuhn (GL), lamina propria (Lp) and muscularis mucosa layer (Mm), Peyer's patches (Pp), Paneth cells (Pc), muscularis externa (Ms), the inner circular (IC) and the outer longitudinal muscle tissue (OL). Also shown are the lumen (L), serosa (S), lacteal (Lt) and blood vessel (Bv).

The histological structure of the small intestine is composed of a serosa, muscularis externa, submucosa, and a mucosa which forms villi that project into the lumen. The muscularis externa contains 2 muscle coats, the thickest being the inner circular muscular coat with a much thinner outer longitudinal muscle coat. The mucosa consists of numerous glands of Lieberkuhn with the presence of Paneth cells and Peyer's patches intermittingly scattered within the lamina propria (Fig. 17, Fig. 19, Fig. 22). Mucosa incorporates the villi which are lined with a simple columnar epithelium with goblets cells dispersed throughout the epithelial lining. The lamina propria of villi is quite vascular with a centrally located lacteal.

The duodenum is the site where most chemical digestion takes place. Villi height and crypt depth are at the highest and steadily decrease in length and depth caudally in the jejunum and at the lowest in ileum. The muscularis externa has a thick inner circular muscular coat with the outer longitudinal muscle coat been well defined (Fig. 17).

The jejunum is the site where a significant level of nutrient absorption first begins (Fig. 18). The muscularis externa is decreased in thickness compared with the duodenum and the outer longitudinal muscle coat is barely distinguishable in some parts (Fig. 19). The density of goblet cells dispersed throughout the epithelial lining of villi is increased in comparison to the duodenum (Fig. 17).

The ileum (Fig. 20, Fig. 21) is the final site of nutrient absorption and shares similar characteristics with jejunum. In comparison to duodenum and jejunum, there is an increase of the villi thickness with a more defined crypt (Fig. 22). Like the jejunum, the muscularis externa has decreased in thickness in comparison to the duodenum (Fig. 17) with the outer circular and longitudinal muscle well defined (Fig. 19).

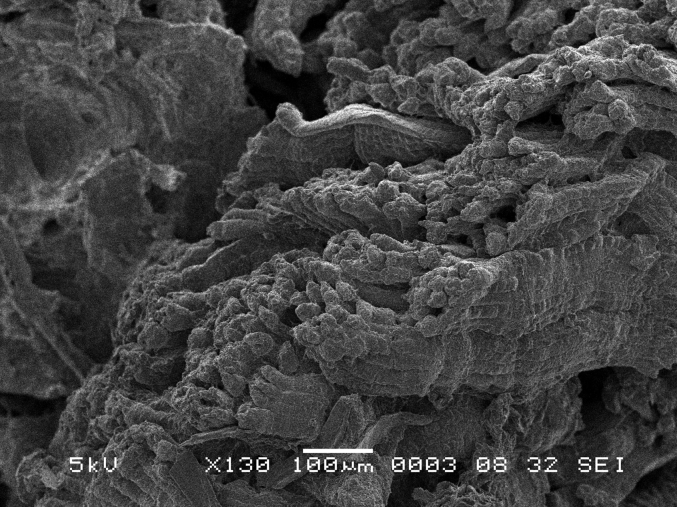

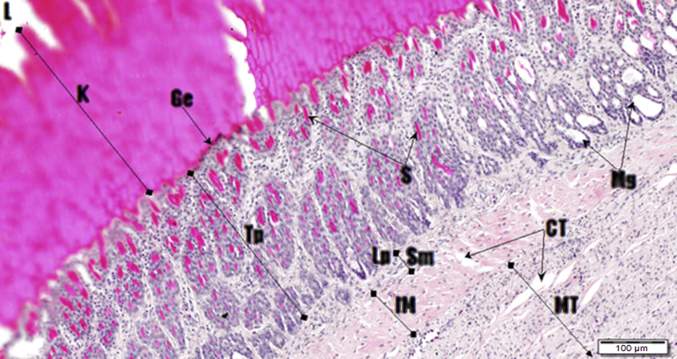

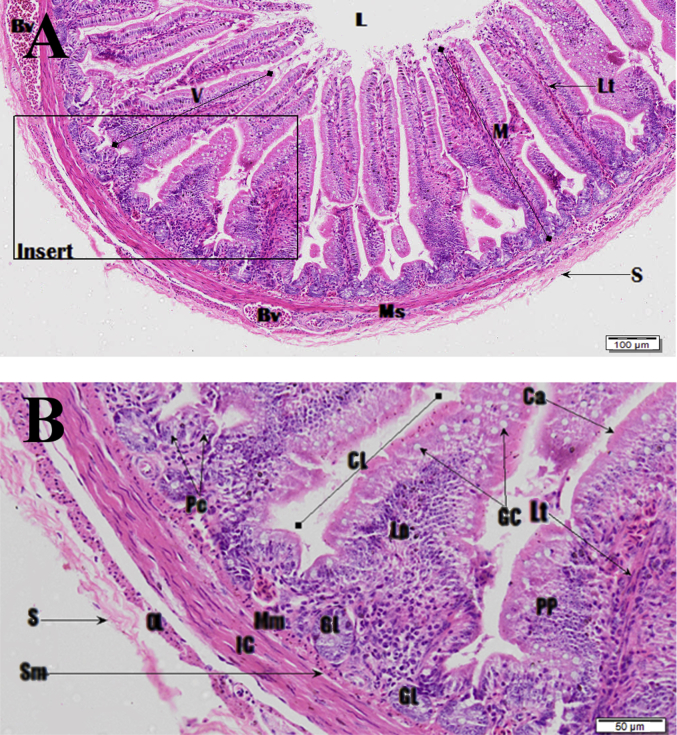

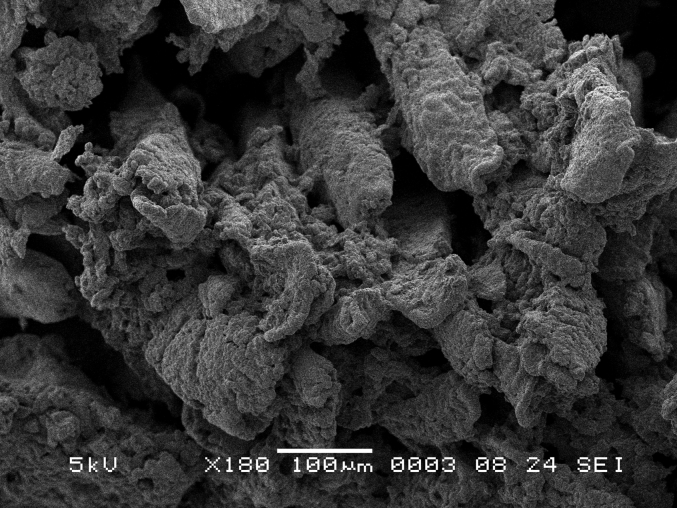

3.7. Caecum

The caecum (Fig. 23) consists of 2 blind pouches that lie caudally to the ileum. This organ is not essential for digestion; instead it is the major site of fermentation. The caecum lamina epithelial mucosal lining contains simple columnar cells with striated borders that are dispersed with goblet cells (Fig. 24). It is documented that villi length varies throughout the caecum and gradually becomes decreased in length towards the terminal area of the caecum. Lymph nodes can be found throughout the mucosal lining and are dispersed regularly, which was also mentioned by Fitzgerald (1969), but not described in this study, are gatherings of lymphatic tissue called caecal tonsils. Nowadays, intestinal associated lymphoid tissue is of particular importance in relation to local immunity in industrial poultry farming. Any future research on these lymphoid structures using this bird species as an experimental model, given its biological features, could have important pragmatic significance in this area.

Fig. 23.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph showing the luminal surface of the caecum.

Fig. 24.

Photomicrograph of the caecum. Image B is zoomed insert section shown in image A. Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain. Columnar cells (Ca), goblet cells (Gc), paneth cells (Pc), glands of Lieberkuhn (GL), muscularis mucosa (Mm), lumen (L), villi (V), lamina propria (LP), lacteal (Lt), mucosa (M), muscularis mucosa (Mm), submucosa (Sm), inner circular muscle (IC), outer longitudinal muscle (OL), serosa (S), lymph node (LN), blood vessel (Bv) and adipose cells (Ac).

These images have shown that, microscopically, the Japanese quail shares typical characteristics pertaining to birds in general (Fitzgerald, 1969, Hodges, 1974, Susi, 1969). The domestic chicken and the Japanese quail share an evolutionary lineage and have been classified as belonging to the same family, Phasianidae. This study has found that structurally the Japanese quail's gastrointestinal tract shares typical characteristics when compared to the chicken, but also some differences are evident.

The salivary glands of birds are generally not well developed when compared to mammals, although they are more developed in birds that consume grains and insects than in birds whose diet consists of soft foods such as meat, fruit and nectar (Iwasaki, 2002).

Investigations that examine the morphology of the avian tongue have shown that the diet, food intake and habitat are relevant to the shape of the tongue (Emura et al., 2008, Rodrigues, 2012, Susi, 1969). The Japanese quail tongue shares many similar features with chicken in that the majority epithelium consists of a hard keratinized layer with a carpet like body equipped with numerous mucosal glands (Susi, 1969).

Both the palatine and lingual surfaces are equipped with numerous salivary glands that not only moisten and lubricate food, but also protect the epithelial surfaces of the oral cavity, digestive and respiratory tract from pathogenic invasion by inhibiting the proliferation of microbes (Samar et al., 2002).

A feature that is unique to avian species is that the equivalent of the mammalian stomach is divided up into 2 distinct areas. The first section (proventriculus) is a glandular organ that secretes gastric juices and enzymes to start the digestion process. The gizzard or ventriculus is the second part and is responsible for the grinding of food particles for ease of digestion. This muscular pouch is known to be well developed in birds whose diet consists of rough, fibrous ingredients such as insects or grains while species whose diet consists of softer ingredients such as meat, fruit or nectar have less developed gizzard muscles and koilin membrane (Hodges, 1974). The gizzard has also been shown to change in size in response to dietary composition. A study by Starck and Rahmaan (2003) showed that the gizzard increases in size when diet contains more fibre. They also concluded that the increase in mechanical grinding needed to refine the higher fibre diet resulted in hypertrophy of the smooth muscle cells of the organ rather than increased cell proliferation (Starck and Rahmaan, 2003). In broiler chickens poor development of the gizzard can be result of finely ground diet lacking in fibre and secondary dilation of the proventriculus (Riddell, 1976). The koilin membrane in the line of Japanese quail observed in this study was an olive green colour. This is in contrast to what was reported in The Coturnix quail book by Theodore C. Fitzgerald, who described the koilin as having a yellow hue (Fitzgerald, 1969) which is the colour that is reported by several sources within the domestic chicken gizzard (Akester, 1986, Hodges, 1974). It is interesting to note that green koilin has been observed in the macaw and was attributed to diet composition (Rodrigues, 2012). The Japanese quail used in this investigation consumed feed that was comparable with chicken food in texture and composition. It may be possible that the differences in colour may be attributed to differences in the actual production mechanism of koilin rather than diet.

In chicken, the structure of the koilin membrane consists of vertical rod like projections consisting of hard koilin that forms clusters. In Japanese quail, koilin rods are arranged in a uniform manner presenting as a carpet-like appearance as shown in Fig. 13, Fig. 14. In comparison, chicken photomicrographs show that the conformation of the vertical rods clusters are arranged in groups of 12 to 15 with a clear separation zone between groups (Akester, 1986) which is very different to the Japanese quail samples in this study.

The small intestine shares a similar structure to that seen in the chicken (Hodges, 1974). As seen with chicken, the size and density of villi throughout the length of the intestinal mucosa decreased caudally as did the muscular mucosa and lumen size (Hodges, 1974). Studies in chicken have shown that absorption of nutrients is associated with villus height to crypt depth ratio.

Several studies have shown that diet can alter the structure of the small intestine. A high fibre diet has been shown to increase not only the villi height/depth ratio, but also increases the length of the small and large intestine (Starck and Rahmaan, 2003). This was found to involve cell proliferation in the intestinal crypts and mucosal epithelium (Starck and Rahmaan, 2003). Nutrients have also been shown to affect intestinal structure. A study by Laudadio et al. (2012) involving chickens showed that different levels of protein within feed had an effect on the villus/crypt depth ratio. This study found that the birds performed their best when protein was at medium levels. Chickens fed low or high levels of protein were found to have a decreased villus height/depth ratio (Laudadio et al., 2012). These characteristics are important for the barrier function of the mucous membrane against various pathogens and are directly related to intestinal health and digestion.

A major factor that affects the intestinal structure is microbial ecology within the intestinal tract. Intestinal bacteria also supplement the digestive capabilities of the intestine by promoting further food digestion, hormone and metabolite production, extracting nutrients, immune system development and providing resistance to pathogenic bacteria (Stanley et al., 2014). We have shown (Wilkinson et al., 2016) that quail intestinal microbiota is harbouring distinct microbial community, showing profound sex differences significantly different between males and females in both abundance (P = 0.00008) and structure (P = 0.00027), where dominance of Lactobacillus exists in female birds, and male birds present significantly higher richness and diversity than female birds. Although very similar to chicken intestinal microbiota, Japanese quail intestinal microbiota is unique and distinguishable (Wilkinson et al., 2016) despite containing many shared beneficial and pathogenic species. An extreme example is the Clostridium colinum infection, also known as ulcerative enteritis or quail disease, where the agent is a common intestinal resident. The high sensitivity of this species to the pathogen leads to 100% mortality. This demonstrates marked differences in the action of microbial toxins in different bird species (chickens, turkeys) where mortality usually varies between 2% and 10% (Dinev, 2010).

Although the intestinal tract can function without the intestinal microbiota, its capacity and structural integrity are severely compromised (Thompson and Trexler, 1971). The effect on the intestinal tract is evident in Germ-free animal models. Malnutrition is prevalent due to an increased content of undigested food matter in faeces despite ingesting adequate food sources (Backhed et al., 2007). Motility and gastric emptying of the intestinal system is reduced due to underdevelopment. The structure of the epithelium of the intestinal wall of Germ-free animals has been found less cellular and less hydrated with reduced lamina propria and mucosal surface area (Guarner and Malagelada, 2003).

4. Conclusions

This study describes in detail the gastrointestinal tract of Japanese quail through use of scanning electron microscopy and light microscopy. Although Japanese quail share typical characteristics pertaining to birds in general, differences were observed including the gizzard koilin membrane. This study provides a valuable source of information on intestinal histology of Japanese quail.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted within the Poultry CRC, established and supported under the Australian Government's Cooperative Research Centres Program. Poultry CRC provided PhD scholarship for Ngare Wilkinson. The authors thank Giselle Weegenaar for the assistance in histology techniques and guidance. We thank Gavin Wilkinson for his assistance in the digital preparation of scanned micrographs presented in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Akester A.R. Structure of the glandular layer and koilin membrane in the gizzard of the adult domestic fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus) J Anat. 1986;147:1–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed F., Manchester J.K., Semenkovich C.F., Gordon J.I. Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:979–984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605374104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg C., Holm L., Brandt I., Brunstrom B. Anatomical and histological changes in the oviducts of Japanese quail, Coturnix japonica, after embryonic exposure to ethynyloestradiol. Reproduction. 2001;121:155–165. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1210155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman J., Regan F. Sebacic and succinic acid derived plasticised PVC for the inhibition of biofouling in its initial stages. J Appl Biomater Biomech. 2011;9:176–184. doi: 10.5301/JABB.2011.8787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinev I. 2010. Diseases of poultry. A colour atlas, 2nd ed. Imprimerie BM, France for B2B Consulting; pp. 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Emura S., Okumura T., Chen H. Scanning electron microscopic study of the tongue in the peregrine falcon and common kestrel. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 2008;85:11–15. doi: 10.2535/ofaj.85.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald T.C. The Iowa State University Press; Iowa: 1969. The Corurnix quail. [Google Scholar]

- Grote K., Niemann L., Selzsam B., Haider W., Gericke C., Herzler M. Epoxiconazole causes changes in testicular histology and sperm production in the Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) Environ Toxicol Chem. 2008;27:2368–2374. doi: 10.1897/08-048.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarner F., Malagelada J.R. Role of bacteria in experimental colitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17:793–804. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6918(03)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M., Liang X., Wang K., Fang J., Geng Y., Chen Z. Morphology and tissue distribution of four kinds of endocrine cells in the digestive tract of the Chinese yellow quail (Coturnix japonica) Anal Quant Cytopathol Histpathol. 2014;36:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges R.D. Academic Press; London: 1974. The histology of the fowl. [Google Scholar]

- Howes J.R. Japanese quail as found in Japan. Quail Q. 1964;1:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki S. Evolution of the structure and function of the vertebrate tongue. J Anat. 2002;201:1–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocamis H., Hossain M., Cinar M.U., Salilew-Wondim D., Mohammadi-Sangcheshmeh A., Tesfaye D. Expression of microRNA and microRNA processing machinery genes during early quail (Coturnix japonica) embryo development. Poult Sci. 2013;92:787–797. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudadio V., Passantino L., Perillo A., Lopresti G., Passantino A., Khan R.U. Productive performance and histological features of intestinal mucosa of broiler chickens fed different dietary protein levels. Poult Sci. 2012;91:265–270. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raji A.O., Alade N.K., Duwa H. Estimation of model parameters of the Japanese quail growth curve using Gompertz model. Archivos de Zootecnia. 2014;63 [Google Scholar]

- Riddell C. The influence of fiber in the diet on dilation (hypertrophy) of the proventriculus in chickens. Avian Dis. 1976;20:442–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodler D., Sinowatz F. Expression of intermediate filaments in the Balbiani body and ovarian follicular wall of the Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) Cells Tissues Organs. 2013;197:298–311. doi: 10.1159/000346048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M.N. Microscopical study of the digestive tract of blue and yellow macaws. In: Mendez-Vilas A., editor. Current microscophy contributions to sdvances in science and technology. Formatex; Spain: 2012. pp. 414–421. [Google Scholar]

- Rundfeldt C., Wyska E., Steckel H., Witkowski A., Jezewska-Witkowska G., Wlaz P. A model for treating avian aspergillosis: serum and lung tissue kinetics for Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) following single and multiple aerosol exposures of a nanoparticulate itraconazole suspension. Med Mycol. 2013;51:800–810. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2013.803166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacksteder J.R.M. Raising Japanese quail under germfree and conventional conditions and their use in cancer research. J Nat Cancer Inst. 1960;24:1405–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Samar M.E., Avila R.E., Esteban F.J., Olmedo L., Dettin L., Massone A. Histochemical and ultrastructural study of the chicken salivary palatine glands. Acta Histochem. 2002;104:199–207. doi: 10.1078/0065-1281-00627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simova-Curd S., Foldenauer U., Guerrero T., Hatt J.M., Hoop R. Comparison of ventriculotomy closure with and without a coelomic fat patch in Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) J Avian Med Surg. 2013;27:7–13. doi: 10.1647/2009-040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair K.M., Church M.E., Farver T.B., Lowenstine L.J., Owens S.D., Paul-Murphy J. Effects of meloxicam on hematologic and plasma biochemical analysis variables and results of histologic examination of tissue specimens of Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) Am J Vet Res. 2012;73:1720–1727. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.73.11.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrzypek T., Valverde Piedra J.L., Skrzypek H., Wolinski J., Kazimierczak W., Szymanczyk S. Light and scanning electron microscopy evaluation of the postnatal small intestinal mucosa development in pigs. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;56(Suppl. 3):71–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley D., Highes R.J., Moore R.J. Microbiota of the chicken gastrointestinal tract: influence on health, productivity and disease. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:4301–4310. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5646-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starck J.M., Rahmaan G.H. Phenotypic flexibility of structure and function of the digestive system of Japanese quail. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:1887–1897. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susi F.R. Keratinization in the mucosa of the ventral surface of the chicken tongue. J Anat. 1969;105:477–486. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson G.R., Trexler P.C. Gastrointestinal structure and function in germ-free or gnotobiotic animals. Gut. 1971;12:230–235. doi: 10.1136/gut.12.3.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waligora-Duprieta, Dugayb A., Auzeilb N., Nicolisc I., Rabotd S., Huerree M.R. Short-chain fatty acids and polyamines in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis: kinetics aspects in gnotobiotic quails. Anaerobe. 2009;15:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherbee D.K. Investigations in the life history of the common Coturnix. Am Midl Nat. 1961;65:168–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson N., Hughes R.J., Aspden W.J., Chapman J., Moore R.J., Stanley D. The gastrointestinal tract microbiota of the Japanese quail, Coturnix japonica. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;9:4201–4209. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-7280-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J.A., Jefferies W. Towards the conservation of endangered avian species: a recombinant West Nile Virus vaccine results in increased humoral and cellular immune responses in Japanese Quail (Coturnix japonica) PLoS One. 2013;8:e67137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]