Abstract

HER2 receptors are surface proteins belonging to the epidermal growth factor family of receptors (EGFR). Their numbers are elevated in breast, lung, and ovarian cancers. HER2-positive cancers are aggressive, higher mortality rate and have a poor prognosis. We have designed peptidomimetics that bind to HER2 and block the HER2-mediated dimerization of EGFR receptors. Among these, one symmetrical cyclic peptidomimetic (compound 18) exhibited antiproliferative activity in HER2-overexpressing lung cancer cell lines with an IC50 values in the nanomolar concentration range. To improve the stability of the peptidomimetic, D-amino acids were introduced into the peptidomimetic, and several analogs of compound 18 were designed. Among the analogs of compound 18, compound 32, a cyclic, D-amino acid-containing peptidomimetic, was found to have an IC50 value in the nanomolar range in HER2-overexpressing cancer cell lines. The anti-proliferative activity of compound 32 was also measured using a 3D cell culture model that mimics the in vivo conditions. The binding of compound 32 to the HER2 protein was studied by surface plasmon resonance (SPR). In vitro stability studies indicated that compound 32 was stable in serum for 48 h and intact peptide was detectable in vivo for 12 h. Results from our studies indicated that one of the D-amino acid analog of 18, compound 32 binds to the HER2 extracellular domain, inhibiting the phosphorylation of kinase of HER2.

Keywords: Lung cancer, HER2, Protein-protein interaction, peptidomimetic, structural activity relationships

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common types of cancer that occurs in both men and women. Among the lung cancers, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type (70–80%) [1]. Nearly 18–30% of NSCLC patients have shown HER2 overexpression. Furthermore, if both EGFR and HER2 are overexpressed, the survival rate of patients is significantly reduced. HER2 is known to dimerize with other family members of EGFR and EGFR:HER2 and HER2:HER3 dimers are important in the development of NSCLC [2, 3]. Thus, inhibition of dimerization of HER2 with other receptors is important in NSCLC therapy. Standard therapies for lung cancer include chemotherapeutic agents (cisplatin, paclitaxel, and docetaxel) that show clinical response in only 30–40% of patients [4].

The EGFR family of receptors is made up of tyrosine kinase receptors, namely, EGFR (ErbB1/HER-1), ErbB2 (HER-2/Neu), ErbB3 (HER-3), and ERbB4 (HER-4). Each receptor has a cytoplasmic kinase domain, a single membrane-spanning region, and an extracellular domain [5–7], which is sub-divided into four domains (I-IV)[8]. Except for HER2, the extracellular domains of these receptors will receive signals from an epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α), and neuregulins, which activate the intracellular signaling pathway by dimerizing (homo- or hetero-) the extracellular domains. This results in cell proliferation, cell growth, and repair [9, 10] [6]. There are no known ligands for HER2 because its extracellular domain II always exists in ‘open’ conformation and is projected in a way that is ready for dimerization [11]. This fixed ‘open’ conformation is the reason for its being the most preferred partner for other EGFR family receptors [12]. Because the dysregulated HER2 receptor pathway was identified as the cause of aggressive disease, many HER2-targeted therapies have been developed or are in development [13, 14].

Antibodies that bind to an extracellular domain of HER2 have been developed for the treatment of HER2 positive breast cancer [15, 16]. Biologics that are approved for non-small cell lung cancer include antibodies such as cetuximab, bevacizumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab [17, 18]. However, antibodies have limitations in terms of stability, delivery, immunogenicity, and toxicity [19, 20]; hence, there is a need to develop novel therapeutic agents that promise disease-free survival. Our idea is to inhibit the protein-protein interactions of EGFR extracellular domains using peptidomimetics to modulate EGFR signaling for cell growth in cancer cells. In our previous work, we have described the synthesis and structure-activity relationship of several peptidomimetics that were developed on the basis of the crystal structure of HER2 and the structure of HER2 complexed with trastuzumab [11]. Among several of these peptidomimetics synthesized (Figure 1), compound 18, a cyclic peptidomimetic, exhibited antiproliferative activity in the nanomolar range on an HER2-overexpressing cell line (SKBR-3, BT-474) and a higher micromolar range activity on a MCF-7 cell line (which does not overexpress HER2 receptors), indicating that it has selectivity towards HER2 receptors [21]. The most potent activity of compound 18 was observed in Calu-3 cell lines (IC50 18 nM), which are NSCLC and overexpress HER2 receptors. Although compound 18 has effective antiproliferative activity, because of the L-amino acids in the sequence, it may have limitations in terms of in vivo stability.

Figure 1.

Structure of compounds A) 5, B) 9 and C) 18 and design of analogs.

In this project, our objective was to synthesize the compound 18 (Figure 1C) analogs by incorporating D amino acids in the peptidomimetic sequence and study the structure-activity relationship. These analogs were designed based on compounds 5, 9, and 18 [22] [23] (Table 1, Figure 1), which exhibited antiproliferative effects on HER2-overexpressing cell lines. Analogs of compound 18 were synthesized by replacing L-amino acids in the peptidomimetic sequence with D-amino acids. Substitution with D-amino acids improves enzymatic resistance against degradation as D-amino acids are not recognized by the enzymes of the body. Replacement of L-amino acids with D-amino acids will alter the overall conformation of the peptidomimetic compared to that of the parent compounds 5, 9, and 18, hence we changed the direction of the peptidomimetic sequence in some of these peptidomimetics. All of the analogs described in this report are cyclic. The synthesized analogs were evaluated for antiproliferative activity on various HER2 overexpressing cell lines, and the peptidomimetic with the lowest observed IC50 value was chosen for further analysis. Among the analogs of compound 18, compound 32 exhibited antiproliferative activity on HER2 overexpressed breast and lung cancer cell lines with IC50 values in the nanomolar concentration. Compound 32, a D-amino acid-containing peptidomimetic, was engineered by joining two reversed sequences of compound 9. An analog of compound 32 with Lys was designed and synthesized (compound 40). Compound 40 was attached with a fluorescent label (6-FAM) resulting in compound 44. The binding ability of these potent compounds was evaluated using surface plasmon resonance and cellular assays. Furthermore, compound 32 was evaluated for its ability to inhibit the growth of cancer cells in a 3D cell culture model. Results from Western blot analysis showed that compound 32 was able to inhibit the phosphorylation of the kinase domain.

Table 1:

Antiproliferative activity of compounds in HER2 overexpressing cancer cells (BT-474, SKBR-3, Calu-3), cancer cells which do not overexpress HER2 receptors (MCF-7) and non-cancerous breast cells (MCF-10A). Activity is represented as IC50 values in μM

| Code | Peptide Sequence | BT-474 | MCF-7 | SKBR-3 | Calu-3 | MCF10A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5* | H2N-R((S)Anapa)F-OH | 0.895±0.029 | 16.9±1.0 | 0.601±0.02 | ||

| 9* | H2N-R((S)Anapa)FD-OH | 0.785±0.011 | 45 | 0.847±0.071 | ||

| 18* | Cyclo(PpR-((R) Anapa)FDDF-((R) Anapa)R | 0.197±0.055 | >50 | 0.018±0.013 | ||

| 30 | Cyclo(Ppr-(R)Anapa-fddf-(R)Anapa-r | 0.86±0.08 | 13.5±0.7 | 0.85±0.07 | 0.55±0.2 | |

| 31 | Cyclo(Ppdf-(R)Anapa-rr-(R)Anapa-fd | 2±0.07 | ||||

| 32 | Cyclo(Ppdf-(R)Anapa-rdf-(R)Anapa-r | 0.29±0.1 | 8.8±1.8 | 0.4±0.3 | 0.5±0.3 | >50 |

| 33 | Cyclo(Ppr-(R)Anapa-fdr-(R)Anapa-fd | 0.85±0.07 | 16.6±4.5 | 0.34±0.2 | 0.68±0.02 | |

| 34 | Cyclo(PpR-(R)Anapa-FF-(R)Anapa-R | 7.9±2.5 | ||||

| 35 | Cyclo(pPr-(S)Anapa-fddf(S)Anapa-r) | 20.6±1.8 | ||||

| 36 | Cyclo(pPr-(S)Anapa-fdr-(R)Anapa-fd) | 16.4±1.5 | ||||

| 37 | Cyclo(PpR-(R)Anapa-FDDFK-(R)Anapa-R | >100 | ||||

| 38 | Cyclo(PpR-(R)Anapa-FDDFK-(S)Anapa-R | >100 | ||||

| 39 | Cyclo(PpR-(S)Anapa-FDDFK-(S)Anapa-R | 33.5±0.7 | ||||

| 40 | Cyclo(PpR-(R)Anapa-FDDF-(R)Anapa-K | 0.4±0.1 | >100 | 0.5±0.2 | 0.65±0.07 | |

| 41 | Cyclo(PpR-(R)Anapa-FDKF-(R)Anapa-R | >100 | ||||

| 42 | Cyclo(PpR-(R)Anapa-FF-(R)Anapa-K | >100 | ||||

| 43 | Cyclo(PpR-(R)Anapa-FF-(R)Anapa-RK | 35.5±0.7 | ||||

| 44 | Cyclo(PpR-(R)Anapa-FDDF-(R)Anapa-K-(6-FAM) |

reported earlier in studies (Satyanarayana Jois et al., 2009; Banappagari et al., 2011, Kanthala et al., 2014, 2017)

Anapa, [3-amino-3(napthyl)]-propionic acid. In the peptide sequence, small letters denotes D-amino acids and capital letters denotes L-amino acids

Materials and Methods

General Information

All chemicals, reagents, resins, and cell lines were obtained from commercial sources. Fmoc-protected amino acids, 2-(6-chloro-1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethylaminium hexafluorophosphate (HCTU) and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) were purchased from Advanced ChemTech, Louisville, KY. Chlorotrityl chloride resin (CTC) was purchased from ChemImpex, Wood Dale, IL. Diisopropylethylamine (DIEA), methanol (MeOH), chloroform, acetic acid, trifluoroethanol (TFE), tetrakis (triphenylphosphine) palladium, N-methyl morpholine (NMM), and 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. Dimethylformamide (DMF), dichloromethane (DCM) and triisopropyl silane (TIPS) were purchased from Protein Technologies, Tucson, AZ. (7-Azabenzotriazol-1-yloxy) tripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyAOP), (benzotriazol-1-yloxy) tripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBOP), and N-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBT) were purchased from EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA. Cell lines and their respective media were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). CellTiter-Glo® reagent was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI).

Cell Lines

All of the cell lines were maintained at 37°C in the incubator. The breast cancer cell lines BT-474 and MCF-7 were maintained in RPMI basal medium. SKBR-3, a breast cancer cell line, was cultured in McCoy’s basal medium. Lung cancer cell line Calu-3 was grown in a basal medium, Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM). MCF-10A, the non-tumorigenic epithelial cell line, was grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM). All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% insulin; however, MCF-10A was additionally supplemented with cholera toxin, hydrocortisone, EGF, and horse serum.

Synthesis of Cyclic Compounds

Peptidomimetics were synthesized by the solid-phase peptide synthesis procedure described in the literature and reported in our earlier studies [24, 25]. CTC resin was loaded with Fmoc-Pro-OH. Unreacted sites on the resin were capped with DCM/MeOH/DIEA (80:15:5). After the substitution level was determined (usually about 0.5 mmol/g), the Fmoc-Pro-CTC resin was deprotected using 20% piperidine in DMF (2 × 5 min) and washed with DMF (5 × 30 s) followed by DCM (5 × 30 s). The H-Pro-CTC resin was dried under vacuum and then stored at 4°C.

Cyclic compounds were synthesized on a Tribute peptide synthesizer (Protein Technologies, Tucson, AZ) utilizing a standard Fmoc peptide chemistry protocol on a 50 μmol scale using the previously loaded H-Pro-CTC resin. Side-chain functionalities were protected with tert-butyl (Asp), NG-2,2,4,6,7-pentamethyldihydrobenzofuran-5-sulfonyl (Arg) and tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Lys). A fivefold excess of Fmoc-L-amino acids, Fmoc-dPro-OH, and HCTU, in the presence of 10 equivalents of DIEA, used for each of the coupling steps (10 min) with DMF as the solvent. After the synthesis of each sequence was complete, the final Fmoc groups were removed using 20% piperidine in DMF (1 × 5 min; 1 × 10 min). The resin from each synthesis was washed with DMF (5 × 30 s) and DCM (5 × 30 s). The side chain-protected peptides were cleaved from the resin with three mL of TFE/DCM (1:1) twice for 2 h each. The cleavage solutions for each respective peptide were combined and concentrated in vacuo. Water was added to the peptide solutions to facilitate precipitation after which the peptide solutions were frozen and lyophilized to yield a white powder.

The peptides were dissolved in THF/DMF (80:20, 200 mL), after which PyAOP (177.3 mg, 4 equivalents) and DIEA (119 μL, 8 equivalents) were added. The cyclization reactions were allowed to proceed for 2 h, after which time the peptides were frozen and lyophilized to yield a white solid. Protecting groups were removed from the peptides using TFA/water/TIPS (4 mL, 95:2.5:2.5) for 2 h. Cold diethyl ether was then added to the peptide solutions to precipitate the crude cyclized peptides. The peptides were centrifuged for 10 min (10,000 rpm), and the ether layers decanted. Fresh cold diethyl ether was added, and the pelleted peptides were resuspended. The peptides were centrifuged again, and the procedure was repeated a total of 5 times for each peptide. After the final ether wash, the peptide pellets were dissolved in a minimal amount of water containing 0.1% TFA, frozen, and lyophilized.

Synthesis of Fluorescently Labeled Compound 44

Fluorescently labeled compound 44 was synthesized on a Tribute peptide synthesizer (Protein Technologies, Tucson, AZ) utilizing a standard Fmoc peptide chemistry protocol on a 50 μmol scale and using the previously loaded H-Pro-CTC resin. Side chain functionalities were protected with tert-butyl (Asp), NG-2,2,4,6,7-pentamethyldihydrobenzofuran-5-sulfonyl (Arg) and allyloxycarbonyl (Lys). A fivefold excess of Fmoc-L-amino acids, Fmoc-dPro-OH, and HCTU, in the presence of 10 equivalents of DIEA, was used for each of the coupling steps (10 min) with DMF as the solvent. The resin was washed with DMF (5 × 30 s) and DCM (5 × 30 s). Tetrakis (triphenylphosphine) palladium (173 mg, 3 eq.) dissolved in 2 mL of chloroform: acetic acid:NMM (37:2:1) was added to the reaction vessel containing the peptidyl resin. The flask was purged thoroughly with N2, sealed, and shaken for 2 h to remove the alloc group protecting the epsilon nitrogen of the lysine residue. The resin was then drained and washed with DCM (5 × 30 s) and DMF (5 × 30 s).

A solution of 4 equivalents each of HOBT (31 mg), 6-FAM (75 mg), and PyBOP (104 mg) and 35 μL of DIEA in 2 mL of DMF was shaken for 2 min and then added to the reaction vessel containing the peptidyl resin. The vessel was sealed and shaken overnight. This procedure was repeated once more. The resin was washed with DMF (5 × 30 s). The N-terminal Fmoc group was removed using 20% piperidine in DMF (1 × 5 min; 1 × 10 min). The side chain-protected fluorescently labeled peptide was cleaved from the resin with 3 mL of TFE/DCM (1:1) twice for 2 h. The cleavage solutions were combined and concentrated in vacuo. Water was added to the peptide solution to facilitate precipitation after which the peptide solution was frozen and lyophilized to yield a yellow powder. The peptide was dissolved in THF/DMF (4:1, 200 mL), after which PyAOP (177.3 mg, 4 equivalents) and DIEA (119 μL, 8 equivalents) were added. The cyclization reaction was allowed to proceed for 2 h; following this, the peptide was frozen and lyophilized to yield a yellow solid. Protecting groups were removed from the peptide using TFA/water/TIPS (4 mL, 95:2.5:2.5) for 2 h. Cold diethyl ether was then added to the peptide solutions to precipitate the crude fluorescently labeled cyclized peptide. The peptide was centrifuged for 10 min (10,000 rpm), and the ether layer was decanted. Fresh cold diethyl ether was added, and the pelleted peptide was resuspended. The peptide was centrifuged again, and this procedure was repeated 5 times in total. After the final ether wash, the peptide pellet was dissolved in a minimal amount of water containing 0.1% TFA, frozen, and lyophilized.

Analysis and Purification

HPLC analysis was performed with a Waters 616 pump, Waters 2707 autosampler, and 996 photodiode assay detector controlled by Waters Empower 2 software. The separation was performed on an Agilent Zorbax 300 SB-C18 (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm) with an Agilent guard column Zorbax 300 SB-C18 (5 μm, 4.6 × 12.5 mm). Elution was done with a linear 5% to 55% gradient of solvent B (0.1% TFA in acetonitrile) into A (0.1% TFA in water) over 50 min at a 1 mL/min flow rate with UV detection at 215 nm. Preparative HPLC runs were performed with a Waters prep LC controller, Waters sample injector, and 2489 UV/Visible detector, which are controlled by Waters Empower 2 software. The separation was performed on an Agilent Zorbax 300SB-C18 PrepHT column (7 μm, 21.2× 250 mm) with a Zorbax 300SB-C18 PrepHT guard column (7 μm 21.2 × 10 mm) using a linear 5% to 55% gradient of solvent B (0.1% TFA in acetonitrile) into A (0.1% TFA in water) over 50 min at a 20 mL/min flow rate with UV detection at 215 nm. Fractions having high (>95%) HPLC purity and the expected mass were combined and lyophilized. Analytical data for the peptides are provided in supporting information (Table S2).

Circular Dichroism (CD)

The CD experiments were performed using a Jasco-J815 spectropolarimeter (JASCO Inc., Easton, MD) flushed with nitrogen. All experiments were performed at room temperature. Peptidomimetics (5 mM) were dissolved using methanol and then transferred into 1-mm path length rectangular quartz cells. The spectra were collected from 190–380 nm. An average of 4 scans for each spectrum was used, with an average scan rate of 50 nm/min. The baseline was subtracted from the spectrum for the final representation.

Antiproliferative Assay

The CellTiter-Glo assay kit [26, 27] was purchased from Promega Corporation (Madison, WI). When the cells reached 90% confluency, they were trypsinized, and cell suspensions were obtained. Each well in the 96 well-plate was coated with about 104 cells, which were then incubated overnight at 37°C. The stock solutions of the test compounds were prepared in DMSO and diluted according to the required concentrations (0.001 μM to 200 μM) using the respective serum-free media. 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was used as a positive control. The controls included wells containing serum-free medium without any test compounds and cells treated with 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). After overnight incubation, the medium was removed; test compounds (various concentrations) were added to the wells in triplicate, and they were incubated for about 72 h. After washing with PBS, 100 μL of CellTiter-Glo® reagent was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for about 20 min. The luminescence reading was obtained using a plate reader. The IC50 values were derived from the dose response plots using GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA). All the experiments were repeated three times, and the standard deviations were calculated.

3D Cell Culture

The spheroids for the 3D cell cultures were grown in 96-well Perfecta3D® hanging drop plates (3D Biomatrix). To prevent evaporation of spheroids, these plates were equipped with a peripheral water reservoir that was filled with PBS. Also, the plate was sandwiched between a top lid and a bottom lid, which can also be filled with PBS. 40 μL of BT-474 cell suspension containing 200 cells/μL was dispensed into the access hole at each cell culture site in the 96-well Perfecta3D® hanging drop plate to form a hanging drop. After 4 days of incubation at 37°C, the spheroids were formed. They were later transferred to a flat-bottomed 96-well plate. Similar to a regular 2D cell culture, the spheroids were treated with different concentrations (0.001 μM to 100 μM) of test compounds and incubated for 3 days in the incubator at 37°C. Later, 100 μL of 3D CellTiter-Glo® reagent was added to each well, and the luminescence reading was obtained using a plate reader. The IC50 values were obtained from a dose-response curve generated using GraphPad Prism. All the experiments were repeated three times, and the standard deviation was calculated.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

The HER2 D IV protein (obtained from Leinco Technologies, St. Louis, MO) was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip (GE Healthcare Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) at a rate of 10 μL/min using standard amine coupling procedure on a Biacore X100 (GE Healthcare Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) instrument. A solution of 0.2 M N-ethyl N-(dimethyl aminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) and 0.05 M N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (35 μL solution, flow rate 5 μL/min) was used to activate the carboxyl groups on the chip. The immobilization was performed by injection of HER2 D IV, which was continued onto the chip surface until 10,018 response units were reached, after which unreacted activated groups were blocked with 1 M ethanolamine for 7 min. After immobilization, different concentrations (0 to 100 μM) of compound 32 were tested for binding to HER2 D IV protein. A reference surface was generated under the same conditions without compound 32 or HER2 protein D IV injection. Binding of compounds 32 and fluorescently labeled compound 44 to HER2 ECD (domains I-IV 620 amino acids) was also analyzed using Reichert Technologies SPR instrument (SR700DC, Buffalo, NY). A peptidomimetic (compound 37), which has an IC50 value >50 μM in antiproliferative activity on BT-474 cell line, was used as a negative control. Experiments were repeated three times.

Competitive Binding Assay

In a 96-well tissue culture plate, about 104 BT-474 cells were coated and incubated overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2. The following day, the medium was removed, and different concentrations (0.5 to 50 μM) of compound 32 with a constant concentration (50 μM) of 6-FAM-labeled compound 44 were added to the wells in triplicate. All the dilutions were made in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The plate was then wrapped in aluminum foil and incubated for 1 h. Later, each well was washed twice with 100 μL of PBS, and fluorescence was determined with a microplate reader using 485 nm and 528 nm, respectively, as excitation and emission wavelengths. Treatment with only PBS was used as a negative control. The florescence values of the triplicates were averaged, and a plot of concentration vs. fluorescence was drawn. Similar studies were carried out using MCF-7 cell lines as control.

Confocal Microscopy

This assay was performed by coating about 104 BT-474 cells onto 8-well labtek chamber slides and incubating overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2. The next day the medium was removed, and the cells were treated with 0.5 μM 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM)-labeled compound 44 in PBS for 30 min. Later, the cells were washed with 100 μL of PBS and then fixed by incubating each well with 500 μL of methanol for 5 min at −20°C. Methanol was removed followed by washing twice with 100 μL of PBS. Finally, images were taken using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus Fluoview) with 40 × at λex = 490 nm and λem = 520 nm. Similar studies were conducted using MCF-7 cells line.

Inhibition of Protein-Protein Interaction

Breast cancer cells BT-474 and lung cancer cells Calu-3 were coated onto a 8-well labtek chamber slides and incubating overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 24 h medium was removed and cells were treated with compound 32 at 1 and 4 μM concentrations or controls. Cells without any treatments and cells without primary antibodies but with PLA probes were used as controls. Medium containing peptide was removed after 48 h and cells were fixed in cold methanol. Fixed cells were used for proximity ligation assay (PLA). Primary antibodies for EGFR, HER2, and HER3 were added and incubated the cells for overnight at 4 °C. After washing, secondary antibodies with PLA probes was added for each of the protein pairs (EGFR:HER2; HER2:HER3), and cells were incubated. After washing, PLA fluorescent probe was added, and cells were covered with cover slip with mounting medium. Slides were visualized under the microscope (Olympus BX63 fitted with deconvolution optics), and images were taken at 10 × and 40 × using CellSens Dimension software. As control cells without treatment and control peptide were used.

Western Blot

The BT-474 cells were treated with either compound 32 (1.5 μM) or Lapatinib (0.07 μM) or left untreated. Western blot experiments were conducted as described previously [25]. After 36 h treatment with compounds and controls, the cells were trypsinized, and cell lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor was added. The cells were centrifuged, the supernatant was collected, and Bradford assay was performed to determine the protein concentration. Novex 4–20% tris-glycine mini gels were loaded with 30 μg of protein to run the gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). Later, the membranes were blocked using 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in tris-buffered saline (TBS) and Tween 20 (TBST) and probed with t-HER2 and p-HER2 protein antibodies. The membranes were visualized using the Super Signal enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Images were taken using a Kodak Gel Logic-1500 imaging system (Carestream Molecular Imaging, New Haven, CT). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) assay was used to confirm the equal sample loading in each lane. The experiments were repeated three times. A representative Western blot image was used for the final representation.

Stability

For in vitro stability studies compound 32 was dissolved in PBS, and diluted sample at a concentration of 2 mM was added to human serum purchased from Innovative Research (Novi, MI) (100 μL of peptide sample to 900 μL of human serum). At different time points (0, 15, 30 min, 1, 2, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h), 100 μL of the sample was aliquoted and 500 μL of cold acetonitrile was added. After vortexing, the mixture was centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was taken out and passed through SEP-PAK C18 column (Waters, Milford MA) to remove the remaining protein contents. The peptide was eluted from the SEP-PAK column by acetonitrile, and the sample was freeze-dried and stored at −20 °C for analysis. Analysis of the peptide from stored samples was carried out by a Shimadzu HPLC system containing Shimadzu LC-20AB pump, automatic injector Shimadzu SIL-20A HT, and UV/Vis detector Shimadzu SPD-20A which are controlled by Lab Solutions software. The separation was performed on Restek Ultra C18 (5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm) column by isocratic flow resulting from mixing eluents A (0.1% TFA in Water) and B (0.1% TFA in Methanol). The isocratic flow maintained at 5% A and 95% B for 15 min. The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min and detected wavelength was 215 nm. A plot of AUC of the peaks was plotted against time by scaling 0 time point data as 100%. Relative intensity (AUC) is plotted with respect to time, and data are from triplicate experiments. Lyophilized samples were also analyzed by MALDI-TOF-MS at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge LA. α-cyano-4 hydroxy-cinnamic acid (Sigma) was used to prepare the matrix gel. Matrix gel mixture and the lyophilized sample solution were mixed in 1:1 ratio and 1 μl from this mixture were used for analysis.

Stability studies for compound 32 was also carried out in vivo. All animals were handled according to the approved protocol from IACUC at the University of Louisiana at Monroe. Athymic nude mice (Foxn1nu/Foxn1+, female, 4–5 weeks) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) and maintained in the ULM School of Pharmacy vivarium. After acclimatization of animals to the local environment mice were injected with 6 mg/kg of compound 32 in PBS (100 μL) via the tail vein. Mice were divided into two groups of three mice in each group. After 15 min and 12 h mice were sacrificed and blood samples were collected and centrifuged. Compound 32 from the blood samples were extracted as described above. Analysis of the samples was carried out using HPLC (as described above for in vitro studies) and mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS). A plot of relative AUC vs time was obtained as a histogram.

Results and Discussion

Design of Peptides and Structure-activity Relation

We have described the design of compounds 5, 9 and 18 in our previous reports[21, 25, 28]. These compounds were designed based on the crystal structure of HER2:trastuzumab complex as well as EGFR homodimer [11, 29]. Our aim was to design a compound that targets HER2 protein extracellular domain, in particular domain IV and inhibit the protein-protein interactions of EGFR. The binding region of antibody trastuzumab on HER2 protein is relatively small but dominated by hydrophobic interaction as well as hydrogen bonding [11]. Based on the PPI at the binding site and amino acid functional groups involved, a template peptide structure was designed. To make the peptide stable and provide hydrophobic interaction with a pocket on HER2 protein, a β-napthyl group was chosen. The details of the design are provided in our previous publications. Furthermore, domain IV of EGFR are involved in protein-protein interaction and in the crystal structure of EGFR dimer, and the PPI region of EGFR dimer has hydrophobic residues such as Phe, Leu and Trp [29]. Based on these structural aspects compounds 5, 9 and 18 were designed [21, 23, 28]. Compounds 5, 9, and 18 (Figures 1 A, B &C) were shown to bind to the HER2 protein, inhibit HER2 positive cancer cell growth with IC50 values in the lower micromolar concentration range, and inhibit protein-protein interactions of EGFR. Compound 5, 9 and 18 contain an unnatural amino acid Anapa (amino napthyl propionic acid). Compounds 5 and 9 are linear peptidomimetics. Compound 18 is a cyclic peptidomimetic that is a symmetric cyclic version of compound 9. Although, in vitro, compound 18 exhibited stability in serum for more than 48 h [21], the in vivo stability of compound 18 is not known. Usually, peptides with L-amino acids are susceptible to enzymatic degradation in circulation [30]. Even cyclic peptides can undergo degradation in vivo under certain conditions, depending on the sequence of amino acids in the peptide [31, 32]. The peptidomimetics were synthesized with the objective of inhibiting the HER2-based signaling pathway while improving enzymatic resistance by introducing the D-amino acids into the parent compound 18. A change in the chirality of amino acids in a peptide will have an impact on the conformational properties. With the change in chirality, the orientation of side chains with respect to the backbone of the peptide might be different. Therefore, when we change the chirality of amino acids, the activity of the compounds must be evaluated, and the peptides have to be optimized for biological activity. Reversal of sequence is a common method to optimize the peptide when the chirality of the amino acids is changed [33]. However, compound 18 is a symmetric cyclic peptidomimetic with two β-amino acids (Anapa); hence, we modified compound 18 with a change in chirality and reversal of sequence as well as a reversal of sequence on one side of the symmetric peptidomimetic. In addition to this, compound 18 has Pro-Pro sequence, and the chirality of the Pro-Pro sequence is important for the conformation of the peptide. The effects of L-Pro-D-Pro and D-Pro-L-Pro have been studied in detail. L-Pro-D-Pro is known to induce a right-handed helical turn in a peptide, whereas D-Pro-L-Pro is known to induce a left-handed helical turn [34, 35]. In compounds 30 to 33 (Table 1), the chirality of amino acids was changed to D. Compound 30 was obtained by replacing most of the L-amino acids in compound 18 with D-amino acids (except L-Pro-D-Pro). All of these peptidomimetics were initially evaluated for their antiproliferative activity on BT-474 cells. The most potent peptidomimetic was then chosen for further antiproliferative assays on different cell lines. Antiproliferative activity of compound 30 was decreased slightly compared to compound 18, but was comparable to that of compounds 5 and 9. The design of compound 31 was based on the structure of compounds 9 and 18 with L-amino acids replaced by D-amino acids; however, the direction of the chain is reversed compared to compound 9. Compound 31 showed a further decrease in activity compared to compound 30. Compounds 32 and 33 were designed based on the structure of compound 9. Compound 32 with L-Pro-D-Pro sequence and (R) Anapa and D-amino acids had its chain direction on one side of the symmetric molecule sequence reversed. Compound 32 exhibited an IC50 value in the lower micromolar range in BT-474 cell lines. Since there is a reversal in the sequence of compound 9, the binding of the side chain groups to the target site might not have changed compared to the parent compound 9; hence, its activity was retained. It had selectivity toward HER2-ovexpressing cell lines as shown by its low IC50 values compared to its IC50 value of >50 μM in non-cancerous breast cell line MCF-10A.

Compound 33 was synthesized by joining a compound 9 sequence to the reversed compound 9 sequence. Compounds 32 and 33 differ in their chain reversal on only one side of the sequence of compound 9. The antiproliferative activity of compound 33 was decreased significantly compared to that of compound 9. A truncated form of peptidomimetic compound 18 was designed by joining compound 5 symmetrically, resulting in compound 34 (without Asp residues). The antiproliferative activity of compound 34 was 7.9 μM, suggesting that truncation of compound 18 resulted in significant loss of activity. To evaluate the effect of chirality of the Pro-Pro sequence and reversal of chain direction, compounds 35 and 36 were designed. In compound 35, D-Pro-L-Pro sequence was used with (S) Anapa, and the chirality of other amino acids was D. In compound 36, D-Pro-L-Pro with (R) and (S) Anapa was introduced, the Arg-Anapa-Phe-Asp sequence was reversed, and all other amino acids had D-chirality. The antiproliferative activities of 35 and 36 were decreased with IC50 values of >10 μM.

Additionally, we wanted to study the binding of compound 18 to the cell surface using fluorescently labeled compound 18. However, compound 18 does not have any inherent fluorophore with high quantum yield emission. To fluorescently label compound 18, a free amino-terminal is needed. Since compound 18 is cyclic and does not have any free amino group in the side chain, we wanted to introduce a Lys amino acid in the sequence. The introduction of additional amino acids could change the binding ability of compound 18 to HER2 protein. To investigate this, we introduced Lys amino acid at crucial positions and evaluated the antiproliferative activity of compound 18 analogs. In compound 37, we introduced the Lys next to the Phe-Asp-Asp-Phe sequence; in compound 38, a similar position was used, but the chirality of beta-amino acid Anapa was changed to S, and so on to generate compounds 37 to 43. Compound 40 was synthesized by joining a compound 9 sequence to a reversed sequence of compound 9 while replacing one of the arginines with lysine. The replacement of arginine with lysine resulted in antiproliferative activity of the compound 40 similar to that of compounds 5 and 9. This may be because of the positively charged basic amino acid nature of Lys in place of Arg amino acid. Compound 40 had antiproliferative activity in the lower micromolar range on the BT-474 cell line while on MCF-7 it was >100, indicating that it had selectivity. Replacement of Asp with Lys and peptide truncation strategy resulted in the loss of activity of the peptides as shown in compounds 41–43. Among the compounds that included Lys amino acid, compound 40 had the optimum IC50 value in BT-474 cell lines and, hence, the 6-FAM group was attached to compound 40 via lysine amino acid resulting in compound 44. The formation of the 6-FAM-labeled compound 44 was confirmed using mass spectrometry (Supporting Information, Figure S3).

The compounds 30, 32, and 33, 40 which had higher potency toward BT-474 cells, were selected for further antiproliferative activity assays on HER2-overexpressing SKBR-3 and Calu-3 cell lines. From Table 1, it is clear that, among all the analogs of compound 18 studied, compound 32 is the most potent in terms of antiproliferative activity against HER2-positive cancer cell lines. Compound 32 was evaluated for its selectivity using the MCF-7 cell line, which does not overexpress HER2 receptors. Results showed that compound 32 has an IC50 value of about 8.8 μM on MCF-7 cell line, indicating that it selectively targets HER2-overexpressing cells. Additionally, the results showed that compound 32 has IC50 values >50 μM on MCF-10A (non-cancerous cell line), which also indicates its selective nature between cancerous and non-cancerous cell lines. Further experiments were performed to study the effect of compound 32 on the HER2-based dimerization. Overall, the structure-activity relationship studies suggested that the minimum length required for activity of the peptide was 10 amino acids, and truncation of the peptide by removal of Asp residues resulted in the loss of activity. Similarly, for a positive charge, one of the Arg in the peptide could be replaced with Lys to retain the activity seen in compound 40. Lys amino acid residue is known to participate in protein-protein interaction from the analysis of protein-protein interaction surfaces (so-called hot-spot residues such as Arg, Leu, Ile, and Phe as well as Lys) as reported in the literature [36, 37].

CD spectroscopy was used to analyze the overall conformation of the peptide analogs and the effect of a change in the conformation of the peptide upon introduction of D-amino acids in the peptides. The CD spectra of compounds 30 and 32 that exhibited potent antiproliferative activity were compared with that of compound 18 by monitoring the CD bands in the range of 190–380 nm in solvent methanol. The CD spectra of compound 32 exhibited two positive bands one around 290 nm and other around 240 nm (Supporting information, Figure S4). Compound 30 which contains D-amino acids, showed a positive peak at 240 nm, confirming the presence of D-amino acids, and a peak in the range of 260–290 nm, suggesting the presence of a naphthalene ring. Compound 18, which was used as a control, contains L-amino acids; it showed a negative peak around 240 nm (Supporting information, Figure S4), suggesting the presence of L-amino acids.

3D Cell Culture

The antiproliferative activity of a compound is usually evaluated using 2D cell culture, which provides useful preliminary information; however, existing conditions in the tissues such as cellular functions and responses were absent in the regular 2D cell culture [38, 39]. This limits the predictive capability of the assays, whereas 3D-based cell assays will provide more in vivo-like conditions [40, 41]. 3D spheroids are very similar to tumors with inherent metabolic (oxygen) and proliferative (nutrient) gradients. We performed the 3D spheroid assay using BT-474 cells, which overexpress the HER2 receptors. In this assay, after formation of spheroids, they were treated with different concentrations (0.001 μM to 100 μM) of compound 32 for 96 h, then 3D CellTiter-Glo® reagent was added, and luminescence was recorded. The IC50 value obtained from the dose-response curve was 0.5 μM. The IC50 value in 3D cell antiproliferative activity is relatively high compared to that in 2D cell culture (0.29 μM in BT-474, Table 1), indicating that the results were in agreement with previously reported studies in which lower apparent cytotoxicity of drugs such as tamoxifen, doxorubicin, and docetaxel was observed in 3D culture assays than in 2D cell culture assays [42–44].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Analysis

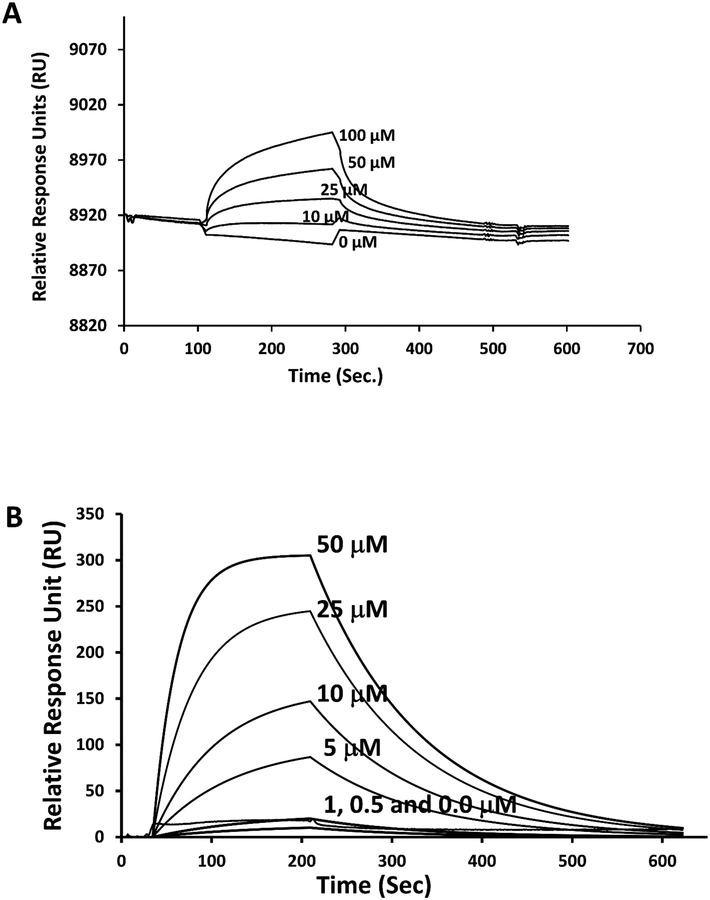

Compound 18 and its analogs were designed to bind to the HER2 protein extracellular domain. To show that compound 32 binds to the HER2 extracellular domain, surface plasmon resonance analysis was carried out [45, 46]. HER2 protein domain IV was immobilized on the CM5 chip using 10 mM acetate buffer at pH 4.5. Various concentrations of compound 32 (0 to 100 μM) were injected into the flow channel of the CM5 sensor chip in which HER2 DIV was immobilized. Relatively slow kinetics of association of compound 32 with HER2 protein was seen (Figure 2A), and after 200 s, dissociation of the ligand was observed. A concentration-dependent kinetics were observed, indicating that compound 32 binds to the HER2 protein. Kd value was obtained by analyzing the data with 1:1 langmuir binding model and Kd was calculated to be 1 μM for compound 32 to bind to domain IV of HER2. Binding studies of compound 32 also conducted using full ECD of HER2 protein (domains I-IV, 620 amino acids). For the complete extracellular domain of HER2 Kd calculated to be 3.48±0.93 μM (Figure 2B). As a control, different concentrations of compound 37 with IC50 values >100 μM on HER2-overexpressing cells were used (Supporting Information, Figure S5). Compound 37 did not show any association phase, indicating that it does not bind to the HER2 protein. Fluorescently labeled compound 44 was also analyzed for its binding ability to HER2 ECD using SPR. SPR sensorgram indicated that compound 44 binds to HER2 ECD in a concentration dependent manner with a Kd of 6.13 ± 0.64 μM (Supporting information, Figure S8).

Figure 2.

Binding of compound 32 to HER2 extracellular domain using SPR. The protein HER2 ECD or Domain IV was immobilized on a CM5 chip using the standard amine coupling procedure. Different concentrations of compound 32 was used as analytes. Kinetics of association and dissociation were measured. The sensor chip surface with only protein was used as a reference, and sensorgrams were represented after subtracting the values from the reference surface. Experiments were repeated 3 times and a representative sensorgrams were presented. A) binding of compound 32 to Domain IV of HER2 ECD. B) binding of compound 32 to HER2 ECD consisting of domains I to IV.

Competitive Binding Assay

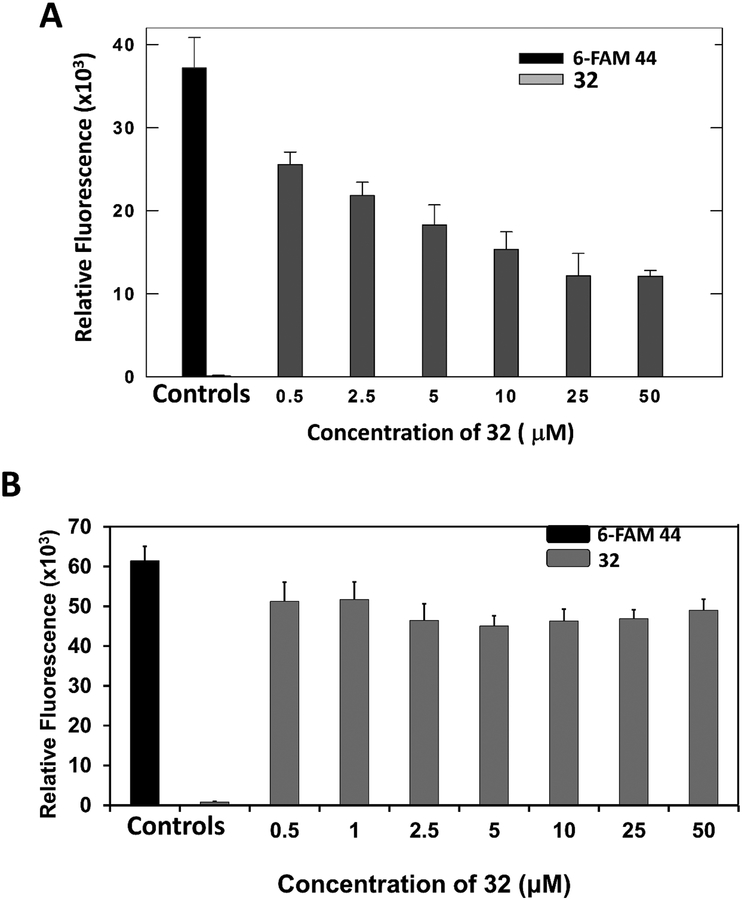

The aim of this experiment was to show that compound 32 binds to the HER2 receptors on the BT-474 cell line. Since compounds 32 and 44 are analogs of 18, it was assumed that compounds 18, 32, and 44 binds to the same site on HER2 protein on BT-474 cells. To show that compound 44 binds to the same site as 32 on HER2 protein, a competitive binding experiment was carried out. In a 96-well plate, different concentrations of compound 32 (0.5 to 50 μM) along with a constant concentration (50 μM) of 6-FAM-labeled compound 44 were added; the plate was incubated for 1 h, after which a florescence reading was taken. A plot of concentration of 32 versus relative fluorescence intensity indicated that, as the concentration of compound 32 (unlabeled) was increased, fluorescence intensity decreased, suggesting that compounds 32 and 44 compete to bind to a HER2 protein on BT-474 cells (Figure 3A). Similar studies were carried out using MCF-7 cell lines that do not overexpress HER2 protein. When compound 32 was added in the presence of 6-FAM-labeled 44, there was no significance between relative fluorescence when different amounts of 32 were added to MCF-7 cells (Figure 3B). These results indicated that compound 32 and 44 specifically binds to cells that overexpress HER2 protein.

Figure 3.

Competitive binding of compound 32 at different concentrations with 6-FAM labeled compound 44 with A) BT-474 cells, B) MCF-7 cells.

Confocal Microscopy

Fluorescently labeled peptides are useful to study the binding of a designed compound to a target protein on the cell surface as well as to study the pharmacodynamics action of designed ligands in vivo. To evaluate whether a compound binds to a specific tissue in vivo, fluorescently labeled compounds of the ligands are used. Compound 18 is a cyclic peptide with head-to-tail cyclization and, hence, there is no free amide group for fluorescent tagging. An analog of compound 18 with Lys in the sequence was designed by structure-activity relationship. Compound 40 with Lys in the sequence exhibited antiproliferative activity with an IC50 of 0.4 μM in BT-474 cell lines and >100 μM in MCF-7 cell lines. An assay was performed to investigate the direct binding of 6-FAM-labeled compound 44 to HER2 receptors on BT-474 cells. Cells were incubated with fluorescently labeled compound 44 and washed. Cells were viewed under a microscope with Ex λ 485 nm and Em λ 528 nm. The nuclei were stained using 4’,6-Diamidine-2’-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI). In the overlay image of 6-FAM-labeled compound 44, green fluorescence is shown around the cells (Figure 4A) whereas this green fluorescence is absent around the cells of the negative control; hence, we can infer that the 6-FAM-labeled compound binds to the receptors on BT-474 cells. Similar studies were carried out on MCF-7 cell lines. Results indicate that there was no green fluorescence in the image suggesting that 6-FAM-labeled 44 does not bind significantly to cells that do not overexpress HER2 protein (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Binding of 6-FAM-labeled compound 44 to HER2 receptors on BT-474 and MCF-7 cells. In an 8-well plate, BT-474/MCF-7 cells were coated and with 0.5 μM 6-FAM-labeled compound 44 in PBS and then incubated for 30 min. A negative control is used in which cells were treated with PBS only. The nucleus is stained with DAPI and compound 44 can be visualized by green fluorescence. In the overlay image, green fluorescence is present in the 6-FAM-labeled compound 44-treated cells, but is absent in the control. A) HER2 overexpressing BT-474 cells. B) MCF-7 cells that do not overexpress HER2.

Protein-Protein Interaction Inhibition

Competitive binding experiments and SPR analysis of compound 32 provide the results indicating that compound 32 binds to the HER2 protein. Our ultimate aim is to inhibit the protein-protein interaction of EGFR and cell signaling. To provide the direct evidence of inhibition of PPI of EGFR in HER2 overexpressing cancer cells, we carried out proximity ligation assay (PLA) [47] on BT-474 (HER2 overexpressing breast cancer cells) and Calu-3 (HER2 overexpressing lung cancer cell lines). In PLA assay, if the two proteins are in proximity (~16 nm) then those two proteins can be labeled with primary and secondary antibodies, and proximity can be detected by a fluorescence probe [47]. When the interaction of the two proteins is disrupted by a compound, the change fluorescence is indicative of PPI inhibition. When PLA assay was carried out on BT-474 cells in the absence of compound 32 for EGFR:HER2 dimerization, red fluorescence was seen (Figure 5A) indicating EGFR:HER2 PPI. In the absence of the compound, a negative control (Figure 5B) (secondary antibodies and PLA probe) and in the presence of compound 32 at 1 and 4 μM (Figures 5CD) there was a significant decrease in red fluorescence indicating that compound 32 inhibited PPI of EGFR:HER2 proteins. Similar inhibition was observed for HER2:HER3 dimerization by compound 32 in PLA assay (Figures 6ABCD). When a control compound was incubated with cells, there was no decrease in fluorescence (data not shown). These results provide direct evidence that compound 32 is a dual inhibitor of PPI of EGFR:HER2 and HER2:HER3. PLA assay was also carried out on lung cancer cell lines Calu-3, in the presence of compound 32. Results indicated that compound 32 inhibits HER2:HER3 dimerization in non-small cell lung cancers that overexpress HER2 protein (Supporting Information, Figure S9). These results clearly indicate that compound 32 binds specifically to HER2 protein and inhibits protein-protein interaction of EGFR and hence exhibits antiproliferative activity in HER2 positive cancer cells,

Figure 5.

EGFR:HER2 dimerization and its inhibition by compound 32 using PLA. A) BT-474 cells without treatment and with PLA probes. Note the red fluorescence due to dimerization of EGFR and HER2. B) Control without any primary antibodies but with PLA probe. C) and D) 1 and 4 μM of compound 32. Note the decrease in red fluorescence due to PPI inhibition.

Figure 6.

HER2:HER3 dimerization and its inhibition by compound 32 using PLA. A) BT-474 cells without treatment and with PLA probes. Note the red fluorescence due to dimerization of HER2 and HER3. B) Control without any primary antibodies but with PLA probe. C) and D) 1 and 4 μM of compound 32. Note the decrease in red fluorescence due to PPI inhibition.

Western Blot

To evaluate whether binding of compound 32 to HER2 protein extracellular domain inhibits phosphorylation of the kinase domain in the cytoplasm, Western blot was performed on HER2 proteins extracted from HER2-overexpressing cancer cell lines BT-474 in the presence and absence of compound 32. The phosphorylation of HER2 was detected by the p-HER2 monoclonal antibody. Western blot assay results indicated that compound 32 decreased the level of p-HER2 in the BT-474 cell line, but did not show any significant effect on the total-HER2 protein levels. Lapatinib (0.07 μM), a HER2 kinase inhibitor, was used as a positive control, and untreated cell lysate was a negative control. When we compared the bands of compound 32 (Figure 7A &B) with those of lapatinib and negative control it could be inferred that compound 32 effectively inhibited the phosphorylation of the HER2 protein. As phosphorylation is inhibited, downstream signaling proteins will not be activated, leading to inhibition of cell proliferation.

Figure 7.

Western blot analysis of total and phosphorylated HER2 protein with treatment of compound 32. A) There was a decrease in the phosphorylated HER2 protein, and no effect on the T-HER2 protein when BT-474 cells were treated with compound 32 (1.5 μM). Lapatanib (0.07 μM), a HER2 kinase inhibitor was used as a positive control and untreated cell lysate as a negative control. GAPDH is also visualized to confirm equal loading in each well of the gel. B) Quantification of phosphorylation by western blot.

In the dimerization process, HER2 extracellular domains II and IV are involved. The role of domain II in the dimerization is clearly understood; however, the role of HER2 D IV in the dimerization is not clearly elucidated. Pertuzumab, a monoclonal antibody, inhibits the dimerization by binding to domain II of HER2 protein [48, 49]. Trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody, binds to the D IV of HER2 and inhibits the dimerization; however, the mechanism of action of trastuzumab is not clear [11, 49]. Based on our previous studies [23] and competitive binding studies using fluorescently labeled peptides, we believe that compounds 32 and 40 binds near the C-terminal part of domain IV of HER2 and inhibit PPI of EGFR:HER2 and HER2:HER3, thus inhibiting the HER2 kinase domain phosphorylation and downstream signaling for cell growth.

Stability

Our idea was to synthesize a peptidomimetic that is stable in serum and in vivo by introducing D amino acids in compound 18. To evaluate the stability of compound 32, it was incubated in serum and stability was analyzed by HPLC and mass spectrometry [50, 51]. A graph of AUC vs time indicated that compound 32 was stable for 48 h with only less than 20% of the peptide lost during incubation (Figure 8A). At present we are not sure that the 20% corresponds to the degradation of the peptide during incubation or the peptide was lost due to protein binding [52]. The AUC values from 15 min to 48 h constant suggesting that the peptide did not undergo proteolytic degradation. Thus, compound 32 was stable in serum for 48 h. This data was also supported by analysis of the same sample using mass spectrometry for the intact compound (Supporting Information, Figure S10). To further evaluate whether the compound is stable in vivo we carried out preliminary in vivo studies. Data from 15 min and 12 h indicated that intact compound 32 could be detected in serum in circulation for 12 h in mice (Figure 8B). From our previous in vitro studies, it is clear that compound 18 was relatively stable in vitro in mice serum [21]. Here we extended the study further to evaluate the compound 32 in vivo and have shown that the D-amino acid peptide is stable in vivo in mice model for at least 12 h.

Figure 8.

In vitro and in vivo stability of compound 32. A) Compound 32 was incubated in human serum and samples were analyzed at different time points using HPLC. A graph of relative AUC Vs time indicates the presence of nearly 80% of the intact compound 32 up to 48 h. B) Compound 32 was injected to mice (N=3) at 6 mg/kg in 100 μL PBS via tail vein. Blood samples were collected at 15 min and 12 h and samples were analyzed by HPLC. Note that after 12 h nearly 70% (compared to the 15 min) of compound 12 could be detected indicating that compound was stable in serum up to 12 h.

Conclusions

We successfully synthesized the analogs of compound 18 by replacing the L-amino acids with D-amino acids. Among these peptidomimetics, compound 32 was found to have higher potency as evidenced in antiproliferative assays. SPR results showed that compound 32 binds to the ECD of HER2 protein and in particular domain IV of HER2 protein. Fluorescently labeled analog of compound 32 was shown to bind to specifically to HER2 positive cancer cells. Furthermore, compound 32 was shown to inhibit both EGFR:HER2 and HER2:HER3 dimerization by using PLA. Western blot results showed that there was a decrease in the p-HER2 levels, which was due to the inhibition of HER2-based dimerization. Results from in vitro and in vivo stability studies of compound 32 indicated that compound 32 was detectable in vivo for 12 h. Overall, compound 32 binds to the HER2 D IV and inhibits the HER2-based dimerization as hypothesized. Thus, compound 32 may serve as a template for a new class of peptidomimetics for inhibiting HER2-based dimerization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from NCI/NIH under grant number 1R15CA188225-01A1.

The authors would also like to thank the confocal microscopy facility at the core facility, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article.

References

- [1].Siegel R,Naishadham D,Jemal A, Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013; 63(1): 11–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Brabender J,Danenberg KD,Metzger R,Schneider PM,Park J,Salonga D,Holscher AH,Danenberg PV, Epidermal growth factor receptor and HER2-neu mRNA expression in non-small cell lung cancer Is correlated with survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2001; 7(7): 1850–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hirsch FR,Varella-Garcia M,Cappuzzo F, Predictive value of EGFR and HER2 overexpression in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2009; 28 Suppl 1 S32–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Calikusu Z,Yildirim Y,Akcali Z,Sakalli H,Bal N,Unal I,Ozyilkan O, The effect of HER2 expression on cisplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009; 28 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Riese DJ,Stern DF, Specificity within the EGF family/ErbB receptor family signaling network. BioEssays. 1998; 20(1): 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yarden Y,Sliwkowski MX, Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001; 2(2): 127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Olayioye MA,Neve RM,Lane HA,Hynes NE, The ErbB signaling network: receptor heterodimerization in development and cancer. The EMBO Journal. 2000; 19(13): 3159–3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Burgess AW,Cho H-S,Eigenbrot C,Ferguson KM,Garrett TPJ,Leahy DJ,Lemmon MA,Sliwkowski MX,Ward CW,Yokoyama S, An Open-and-Shut Case? Recent Insights into the Activation of EGF/ErbB Receptors. Molecular Cell. 2003; 12(3): 541–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hynes NE,Lane HA, ERBB receptors and cancer: the complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005; 5(5): 341–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mendelsohn J,Baselga J, Status of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Antagonists in the Biology and Treatment of Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003; 21(14): 2787–2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cho H-S,Mason K,Ramyar KX,Stanley AM,Gabelli SB,Denney DW,Leahy DJ, Structure of the extracellular region of HER2 alone and in complex with the Herceptin Fab. Nature. 2003; 421(6924): 756–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Graus-Porta D,Beerli RR,Daly JM,Hynes NE, ErbB-2, the preferred heterodimerization partner of all ErbB receptors, is a mediator of lateral signaling. The EMBO journal. 1997; 16(7): 1647–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yardley DA, Combining mTOR inhibitors with chemotherapy and other targeted therapies in advanced breast cancer: rationale, clinical experience, and future directions. Breast cancer: basic and clinical research. 2013; 7(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Valabrega G,Montemurro F,Aglietta M, Trastuzumab: mechanism of action, resistance and future perspectives in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Annals of oncology. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Carter P,Presta L,Gorman CM,Ridgway J,Henner D,Wong W,Rowland AM,Kotts C,Carver ME,Shepard HM, Humanization of an anti-p185HER2 antibody for human cancer therapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1992; 89(10): 4285–4289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kute T,Lack CM,Willingham M,Bishwokama B,Williams H,Barrett K,Mitchell T,Vaughn JP, Development of Herceptin resistance in breast cancer cells. Cytometry Part A. 2004; 57(2): 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pirker R, EGFR-directed monoclonal antibodies in non-small cell lung cancer. Target Oncol. 2013; 8(1): 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Silva AP,Coelho PV,Anazetti M,Simioni PU, Targeted therapies for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: Monoclonal antibodies and biological inhibitors. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017; 13(4): 843–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nahta R,Esteva FJ, Herceptin: mechanisms of action and resistance. Cancer letters. 2006; 232(2): 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hansel TT,Kropshofer H,Singer T,Mitchell JA,George AJ, The safety and side effects of monoclonal antibodies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010; 9(4): 325–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kanthala S,Liu Y,Singh S,Sable R,Pallerla S,Jois S, A peptidomimetic with a chiral switch is an inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor heterodimerization. Oncotarget. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Banappagari S,Corti M,Pincus S,Satyanarayanajois S, Inhibition of protein-protein interaction of HER2-EGFR and HER2-HER3 by a rationally designed peptidomimetic. Journal of biomolecular structure & dynamics. 2012; 30(5): 594–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Banappagari S,Ronald S,Satyanarayanajois SD, Structure–activity relationship of conformationally constrained peptidomimetics for antiproliferative activity in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cell lines. MedChemComm. 2011; 2(8): 752–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chan WC,White PD. Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis. Oxford University Press: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kanthala S,Gauthier T,Satyanarayanajois S, Structure-activity relationships of peptidomimetics that inhibit PPI of HER2-HER3. Biopolymers. 2014; 101(6): 693–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Crouch S,Kozlowski R,Slater K,Fletcher J, The use of ATP bioluminescence as a measure of cell proliferation and cytotoxicity. Journal of immunological methods. 1993; 160(1): 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Niles AL,Moravec RA,Riss TL, Update on in vitro cytotoxicity assays for drug development. Expert opinion on drug discovery. 2008; 3(6): 655–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Satyanarayanajois S,Villalba S,Jianchao L,Lin GM, Design, synthesis, and docking studies of peptidomimetics based on HER2-herceptin binding site with potential antiproliferative activity against breast cancer cell lines. Chemical biology & drug design. 2009; 74(3): 246–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lu C,Mi LZ,Grey MJ,Zhu J,Graef E,Yokoyama S,Springer TA, Structural evidence for loose linkage between ligand binding and kinase activation in the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2010; 30(22): 5432–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Vlieghe P,Lisowski V,Martinez J,Khrestchatisky M, Synthetic therapeutic peptides: science and market. Drug Discov Today. 2010; 15(1–2): 40–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Furman JL,Chiu M,Hunter MJ, Early engineering approaches to improve peptide developability and manufacturability. AAPS J. 2015; 17(1): 111–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rotival R,Bernard M,Henriet T,Fourgeaud M,Fabreguettes JR,Surget E,Guyon F,Do B, Comprehensive determination of the cyclic FEE peptide chemical stability in solution. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2014; 89 50–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nitsche C,Behnam MA,Steuer C,Klein CD, Retro peptide-hybrids as selective inhibitors of the Dengue virus NS2B-NS3 protease. Antiviral Res. 2012; 94(1): 72–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Saha I,Chatterjee B,Shamala N,Balaram P, Crystal structures of peptide enantiomers and racemates: probing conformational diversity in heterochiral Pro-Pro sequences. Biopolymers. 2008; 90(4): 537–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chatterjee B,Saha I,Raghothama S,Aravinda S,Rai R,Shamala N,Balaram P, Designed peptides with homochiral and heterochiral diproline templates as conformational constraints. Chemistry. 2008; 14(20): 6192–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bogan AA,Thorn KS, Anatomy of hot spots in protein interfaces. J Mol Biol. 1998; 280(1): 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Moreira IS,Fernandes PA,Ramos MJ, Hot spots--a review of the protein-protein interface determinant amino-acid residues. Proteins. 2007; 68(4): 803–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Pampaloni F,Reynaud EG,Stelzer EH, The third dimension bridges the gap between cell culture and live tissue. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2007; 8(10): 839–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lu X,Howard MD,Mazik M,Eldridge J,Rinehart JJ,Jay M,Leggas M, Nanoparticles containing anti-inflammatory agents as chemotherapy adjuvants: optimization and in vitro characterization. The AAPS journal. 2008; 10(1): 133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Schutte M,Fox B,Baradez M-O,Devonshire A,Minguez J,Bokhari M,Przyborski S,Marshall D, Rat primary hepatocytes show enhanced performance and sensitivity to acetaminophen during three-dimensional culture on a polystyrene scaffold designed for routine use. Assay and drug development technologies. 2011; 9(5): 475–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].dit Faute MA,Laurent L,Ploton D,Poupon M-F,Jardillier J-C,Bobichon H, Distinctive alterations of invasiveness, drug resistance and cell–cell organization in 3D-cultures of MCF-7, a human breast cancer cell line, and its multidrug resistant variant. Clinical & experimental metastasis. 2002; 19(2): 161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nirmalanandhan VS,Duren A,Hendricks P,Vielhauer G,Sittampalam GS, Activity of anticancer agents in a three-dimensional cell culture model. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2010; 8(5): 581–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Morin PJ, Drug resistance and the microenvironment: nature and nurture. Drug Resist Updat. 2003; 6(4): 169–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Weigelt B,Lo AT,Park CC,Gray JW,Bissell MJ, HER2 signaling pathway activation and response of breast cancer cells to HER2-targeting agents is dependent strongly on the 3D microenvironment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010; 122(1): 35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wilson WD, Tech. Sight. Analyzing biomolecular interactions. Science. 2002; 295(5562): 2103–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Komolov KE,Koch KW, Application of surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy to study G-protein coupled receptor signalling. Methods Mol Biol. 2010; 627 249–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Fredriksson S,Gullberg M,Jarvius J,Olsson C,Pietras K,Gustafsdottir SM,Ostman A,Landegren U, Protein detection using proximity-dependent DNA ligation assays. Nat Biotechnol. 2002; 20(5): 473–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Franklin MC,Carey KD,Vajdos FF,Leahy DJ,de Vos AM,Sliwkowski MX, Insights into ErbB signaling from the structure of the ErbB2-pertuzumab complex. Cancer cell. 2004; 5(4): 317–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lee-Hoeflich ST,Crocker L,Yao E,Pham T,Munroe X,Hoeflich KP,Sliwkowski MX,Stern HM, A central role for HER3 in HER2-amplified breast cancer: implications for targeted therapy. Cancer research. 2008; 68(14): 5878–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Jenssen H,Aspmo SI, Serum stability of peptides. Methods Mol Biol. 2008; 494 177–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Majumdar S,Anderson ME,Xu CR,Yakovleva TV,Gu LC,Malefyt TR,Siahaan TJ, Methotrexate (MTX)-cIBR conjugate for targeting MTX to leukocytes: conjugate stability and in vivo efficacy in suppressing rheumatoid arthritis. J Pharm Sci. 2012; 101(9): 3275–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Bohnert T,Gan LS, Plasma protein binding: from discovery to development. J Pharm Sci. 2013; 102(9): 2953–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.