Abstract

Backgroud

Leptospira interrogans is the major causative agent of leptospirosis, a worldwide zoonotic disease. Hemorrhage is a typical pathological feature of leptospirosis. Binding of von Willebrand factor (vWF) to platelet glycoprotein-Ibα (GPIbα) is a crucial step in initiation of platelet aggregation. The products of L. interrogans vwa-I and vwa-II genes contain vWF-A domains, but their ability to induce hemorrhage has not been determined.

Methods

Human (Hu)-platelet- and Hu-GPIbα-binding abilities of the recombinant proteins expressed by L. interrogans strain Lai vwa-I and vwa-II genes (rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II) were detected by flowcytometry, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Hu-platelet aggregation and its signaling kinases and active components were detected by lumiaggregometry, Western analysis, spectrophotometry and confocal microscopy. Hu-GPIbα-binding sites in rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II were identified by SPR/ITC measurements.

Findings

Both rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II were able to bind to Hu-platelets and inhibit rHu-vWF/ristocetin-induced Hu-platelet aggregation, but Hu-GPIbα-IgG, rLep-vWA-I-IgG and rLep-vWA-II-IgG blocked this binding or inhibition. SPR and ITC revealed a tight interaction between Hu-GPIbα and rLep-vWA-I/rLep-vWA-II with KD values of 3.87 × 10−7-8.65 × 10−8 M. Hu-GPIbα-binding of rL-vWA-I/rL-vWA-II neither activated the PI3K/AKT-ERK and PLC/PKC kinases nor affected the NO, cGMP, ADP, Ca2+ and TXA2 levels in Hu-platelets. G13/R36/G47 in Lep-vWA-I and G76/Q126 in Lep-vWA-II were confirmed as the Hu-GPIbα-binding sites. Injection of rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II in mice resulted in diffuse pulmonary and focal renal hemorrhage but this hemorrhage was blocked by rLep-vWA-I-IgG or rLep-vWA-II-IgG.

Interpretation

The products of L. interrogans vwa-I and vwa-II genes induce hemorrhage by competitive inhibition of vWF-mediated Hu-platelet aggregation.

Keywords: Leptospirosis, Hemorrhage, Leptospira interrogans, vwa-I and vwa-II genes, von Willebrand factor, Platelet aggregation, Competitive inhibition

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Leptospira interrogans is the most common causative agent of leptospirosis, a worldwide zoonotic infectious disease. Hemorrhage is a typical pathological feature and common lethal cause of leptospirosis, but its pathogenesis remains unknown. von Willebrand factor (vWF) triggers the platelet-mediated blood coagulation in humans and mammalian animals by binding platelets with its region A (vWF-A). The LB054 (vwa-I) and LB055 (vwa-II) genes of L. interrogans strain Lai contain vWF-A superfamily domains, but no reports have addressed their possible role in hemorrhage of leptospirosis.

Added value of this study

Our study demonstrated that the recombinant products of the vwa-I and vwa-II genes (rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II) are able to bind human or mouse platelets but block the vWF/ristocetin-mediated human platelet aggregation in vitro in which the platelet aggregation-associated PI3K/AKT-ERK and PLCγ2/PKC signaling pathways are not activated. Moreover, rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II presented a high-affinity binding ability with glycoprotein-Ibα, the vWF receptor on platelets to initiate platelet aggregation and the G13/R36/G47 in Lep-vWA-I and G76/Q126 in Lep-vWA-II acted as the Hu-GPIbα-binding sites. rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II caused the diffuse pulmonary and focal renal hemorrhage in mice as well as the dysfunction of animal peripheral blood coagulation.

Implications of all the available evidence

The products of the L. interrogans vwa-I and vwa-II genes are the inducers of hemorrhage by competitive inhibition of vWF-mediated platelet aggregation in blood coagulation.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. Introduction

Leptospirosis caused by Leptospira is a common global zoonotic infectious disease [1,2]. The disease is endemic in Asia, Oceania and South America, but in recent years it has been considered as an emerging infectious disease in Europe, North America and Africa, due to frequent case reports and several outbreaks [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]].

Many animals such as rats and livestock serve as the natural hosts of pathogenic Leptospira genospecies and can persistently shed the spirochetes from their urine for a long period of time [11]. Human individuals are infected by contact with the animal urine-contaminated water or wet soil. After invading into the human body through the skin and mucosa, pathogenic Leptospira genospecies can promptly enter the bloodstream to cause toxic septicemia and then spread into internal organs and tissues such as lungs, liver and kidneys to cause tissue injury [11,12].

Except for non-specific common symptoms such as high fever, headache and myalgia, severe leptospirosis patients are characterized by hemorrhage and jaundice and can die of septic shock, pulmonary diffuse hemorrhage (PDH) and acute renal failure [13,14]. In particular, PDH has a high mortality that usually causes rapid death of leptospirosis patients following frank hemoptysis and mouth-nose bleeding due to extensive intra-alveolar and interstitial hemorrhage [[13], [14], [15]]. Histopathological examination has confirmed that the hemorrhage in leptospirosis is diapedetic through small blood vessels, which occurs in nearly all tissues of the patients [15]. However, the molecular basis and mechanism of hemorrhage during leptospirosis remain unknown.

The blood coagulation system has an important physiological function to prevent hemorrhage [16]. In the blood coagulation process, platelet aggregation plays a crucial role by providing a platform for interaction and activation of blood coagulation factors and von Willebrand factor (vWF) initiates the platelet aggregation by binding to glycoprotein-Ib-α in the GPIb-IX-V complex in platelet membrane [17]. vWF contains twelve regions designated D'-D3-A1/2/3-D4-B1/2/3-C1/2-CK, of which the A1-A3 regions contain GPIbα-binding domains [18]. After ligation of vWF with GPIb-IX-V, the PI3K/AKT-ERK and PLC/PKC signaling pathways in platelets are activated by phosphorylation to cause an increase in NO, cGMP and free Ca2+ levels, which promote synthesis of thromboxane A2 (TXA2) and release of ADP from granules in platelets. High levels of TXA2 and ADP induce talin and αIIbβ3 integrin polymerization to cause platelet aggregation [[17], [18], [19]]. Therefore, vWF is a key factor in human blood coagulation.

Among pathogenic Leptospira genospecies, Leptospira interrogans is the most predominant global genospecies [1,13]. L. interrogans has many serogroups and serovars but L. interrogans serogroup Icterohaemorrhagiae serovar Lai is responsible for disease in over 60% of leptospirosis patients in China [3,14,20]. In the genomic DNA of L. interrogans serovar Lai strain Lai, we found that LB054 and LB055 genes contain several vWF type-A (vWF-A) superfamily domains and the two genes were named as vwa-I and vwa-II [21]. Previous studies reported that the vWF-A peptide segment from human vWF can bind to the GPIbα of human platelets, but it does not evoke platelet functional responses and result in blockage of vWF-induced platelet aggregation [22,23]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the products of L. interrogans vwa-I and vwa-II genes may induce hemorrhage in leptospirosis by competitive inhibition of vWF binding to GPIbα which blocks platelet aggregation.

In the present study, we therefore investigated the distribution of vwa-I and vwa-II genes in different pathogenic or saprophytic Leptospira strains. Subsequently, the platelet GPIbα-binding and aggregation-inhibiting ability of L. interrogans serovar Lai strain Lai recombinant vwa-I and vwa-II gene products containing vWF-A superfamily domains (rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II), as well as the expression and secretion of Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II of the spirochete during infection of human vascular endothelial cells were determined. Moreover, rLep-vWA-I- and rLep-vWA-II-induced hemorrhage in mice was also demonstrated. The results of this study identify the products of L. interrogans vwa-I and vwa-II as hemorrhage inducers in leptospirosis by competitive inhibition of vWF-mediated platelet aggregation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethics statement

All subjects (peripheral blood samples from three volunteers in our laboratory) gave written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the National Regulations for the Administration of Experimental Animals of China (1988–002) and the National Guidelines for Experimental Animal Welfare of China (2006–398). All the animal experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experiment of Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

2.2. Leptospiral strains and culture

Thirteen strains of pathogenic Leptospira belonging to three genospecies for the serological diagnosis of human leptospirosis in China and two strains of non-pathogenic saprophytic L. biflexa were shown in Supplementary Data [3]. All the leptospiral strains were cultured in EMJH liquid medium at 28 °C [20].

2.3. Cell line and culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) line was provided by the Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences. The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Sigma, USA) at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

2.4. Animals

Female C3H/HeJ mice (15 ± 1 g, three-weeks old), female C57BL/6 mice (18 ± 2 g, four weeks old) for generating Leptospira-infected animal model [24], and New Zealand rabbits (3.0–3.5 kg) for preparing rLep-vWA-I-IgG and rLep-vWA-II-IgG were provided by the Laboratory Animal Center of Zhejiang University.

2.5. Detection of vwa-I and vwa-II genes in leptospiral strains

Genomic DNAs from the fifteen leptospiral strains were extracted using a Bacterial Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Axygen, USA). The entire LB054 (vwa—I) or LB055 (vwa-II) gene was amplified from the DNA templates by PCR with the primers vwa-I-1F/vwa-I-1R or vwa-II-1F/vwa-II-1R (Table 1) using a High-Fidelity PCR Kit (TaKaRa, China). All the PCR products were examined by 1.5% ethidium bromide pre-stained agarose gel electrophoresis and then cloned into pMD19-T plasmid using a PCR Product T-A Cloning Kit (TaKaRa) for sequencing by Invitrogen Co. at Shanghai in China. The sequence identities were analyzed and compared with those in GenBank using BLAST software.

Table 1.

Information of primers used in this study.

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Purpose | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| vwa-I-1 | F: ATGAATTTTCAATATCCTTAC | Detection of emtire vwa-I gene | 939 |

| R: TCATACATAATATCTCAGAAA | |||

| vwa-II-1 | F: TTGATTTCTAAAATAAGGGAA | Detection of entire vwa-II gene | 957 |

| R: TCATATTACAGAAACGCATTTC | |||

| vwa-I-2 | F: GCGCATATG(Nde I)GAAGGAGTAGATATATTA | Expression of vwa-I528 segment | 528 |

| R: GCGCTCGAG(Xho I)CATTTCCTCCGGATCTTC | |||

| vwa-II-2 | F: GCGCATATG(Nde I)GATATACTCTTTTTAGTG | Expression of vwa-II603 segment | 603 |

| R: GCGCTCGAG(Xho I)TTGTAGAATTGTAGAATC | |||

| vwa-I-3 | F: TTGCAGGTGCGGCTTATT | Detection of vwa-I-mRNA | 111 |

| R: CGATTGCGGTCCCTTGTT | |||

| vwa-II-3 | F: TTCGTGGATTGGATGTGG | Detection of vwa-II-mRNA | 161 |

| R: GGAAATCGCTTGTGGATC | |||

| 16S-RNA | F: CTTTCGTGCCTCAGCGTCAGT | Inner reference used in qRT-PCRs | 145 |

| R: CGCAGCCTGCACTTGAAACTA |

F: forward primer. R: reverse primer. Underlined areas indicate the sites of endonucleases.

2.6. Bioinformatic analysis of vwa-I and vwa-II genes

The structures and functional domains in the vwa-I and vwa-II genes of L. interrogans serogroup Icterohaemorrhagiae serovar Lai strain Lai were analyzed using TMHMM, PsortB, Octopus, SignalP-4.1 and NCBI-Batch CD-Search softwares.

2.7. Expression of vwa-I and vwa-II gene segments

Expression of the vwa-I and vwa-II gene segments containing the entire vWF-A superfamily domains (vwa-I528 and vwa-II603) from L. interrogans serogroup Icterohaemorrhagiae serovar Lai strain Lai in Escherichia coli and extraction of the expressed recombinant proteins (rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II) were shown in Supplementary Information.

2.8. Removal of lipopolysaccharide in rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II

Possible contaminated E. coli LPS in the rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II extracts were removed with a Detoxi-gel endotoxin removing column chromatography (Thermo Scientific, USA) using pyrogen-free water for elution and then detected using a Limulus Amebocyte Lysate Test Kit (Lonza, Switzerland) as previously described [24,25].

2.9. Preparation of rLep-vWA-I-IgG and rLep-vWA-II-IgG

The preparation of rabbit anti-rLep-vWA-I-IgG or rLep-vWA-II-IgG was shown in Supplementary Data.

2.10. Preparation of human and mouse platelets

Peripheral blood samples from healthy volunteers and C3H/HeJ or C57BL/6 mice were mixed with 0.1 volume of ACD buffer (75 mM sodium citrate, 39 mM citric acid, and 135 mM dextrose, pH 6.5) to prevent pellet self-aggregation, and then diluted with 2 volumes of MTH buffer (20 mM HEPES, 137 mM NaCl, 13.8 mM NaHCO3, 2.5 mM KCl, 0.36 mM NaH2PO4, 5.5 mM glucose, pH 7.4). The diluted blood samples were centrifuged at 180 ×g for 10 min at room temperature. The human (Hu) or mouse (Ms) platelet rich plasmas were suspended in ACD buffer and then centrifuged at 750 ×g for 15 min at room temperature. The Hu-platelets and Ms-platelets were suspended in MTH buffer for immediate use with no self-aggregation using a lumiaggregometer (type Model-700, Chrono-Log, USA) [26].

2.11. Determination of Hu/Ms-platelet-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II

Hu/Ms-platelet-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II was determined by flow cytometry [27]. Briefly, the Hu/Ms-platelets (107) were incubated with 2 μg rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II at 22 °C for 0.5, 1, 2 or 4 h, and then thoroughly washed with 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). Using 1:200 diluted rabbit anti-rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-IgG as the primary antibody and FITC-labeled goat anti-rabbit-IgG (Abcam, USA) as the secondary antibody, the Hu/Ms-platelet-binding percentages of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II were detected using a flow cytometer (type FC-500MCL, Beckman Coulter, USA) with 485/538 nm excitation/emission wavelengths. In the detection, 10 μg rHu/rMs-vWF (Abcam) plus 150 μM ristocetin (Sigma), a common cofactor of vWF for binding GPIbα to induce platelet aggregation in vitro [26,28], and rHlpA, a recombinant hemolysin of L. interrrogans [24], were used as the controls.

2.12. Antibody blockage tests

Hu-platelets were incubated with rabbit rHu-GPIbα-IgG (Abcam) at 22 °C for 3 h while rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II was incubated with rLep-vWA-I-IgG or rLep-vWA-II-IgG at 37 °C for 1 h. The percentages of rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II binding to the GPIbα-blocked Hu-platelets and the IgG-combined rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II binding to Hu-platelets were detected by flow cytometry as above.

2.13. Determination of Hu-GPIbα-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II

Hu-GPIbα-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II was determined by SPR and ITC [29,30]. For SPR detection, 1 nM rHu-GPIbα (R&D, USA) was cross-linked on the activated CM5 sensing array (GE, USA) and then 0.05–0.8 nM rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II in PBS flowed through the surface of rHu-GPIbα-binding array. The combination of rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II with rHu-GPIbα was detected using a SPR-based detector (Type-T200, GE) and quantified by the values of equilibrium association constant (KD). For ITC detection, 1 μM rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II in PBS was added in the titration pool while 0.1 μM rHu-GPIbα in PBS was added in the sample pool. The KD values reflecting the combination of rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II with the rHu-GPIbα in titrating process were detected using a type VP-ITC microcalorimeter (MicroCal, USA) and then analyzed using Origin software. In the detection, rHlpA, a recombinant hemolysin of L. interrrogans [24], was used as the negative array-linking fixed and mobile phase controls in SPR and the negative titration control in ITC.

2.14. Co-precipitation assay

The products of vwa-I and vwa-II genes in total leptospiral proteins were pulled down with rHu-GPIbα (R&D) by co-precipitation assay. Briefly, freshly-cultured L. interrogans strain Lai was precipitated by a 10,000 ×g centrifugation at 4 °C for 30 min. After washing twice with PBS and centrifugation again, the leptospiral pellet was suspended in distilled water and then ultrasonically broken on ice. The lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 ×g for 10 min (4 °C) to remove leptospiral debris and the supernatant containing total leptospiral proteins was collected to detect protein concentration using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). 20 μg mouse anti-rHu-GPIbα-IgG (Abcam) in 500 μL PBS was mixed with 100 μL of 6 mg/mL protein-A-coated agarose beads (Millipore, USA) for incubation in a 90 rpm rotator (4 °C) overnight to form protein-A-GPIbα-IgG beads. After a 10-min centrifugation at 14,000 ×g (4 °C) and washing with PBS, the beads were suspended in 500 μL PBS and then incubated with 20 μg rHu-GPIbα (R&D) as above to form protein-A-GPIbα-IgG-GPIbα beads. After centrifugation and washing with PBS as above, the beads were suspended in 500 μL PBS and then incubated with 200 μg total leptospiral proteins in a 90 rpm rotator (4 °C) for 2 h. After centrifugation and washing thoroughly with PBS, the beads were suspended in Laemmili SDS-PAGE sample buffer for a 5-min water-bath at 100 °C to release protein-A-GPIbα-IgG-binding proteins. After a 10-min centrifugation at 14,000 ×g (4 °C), the supernatant was subjected to SDS-PAGE to examine the released proteins.

2.15. Identification of rHu-GPIbα-binding leptospiral proteins

The released proteins from protein-A-GPIbα-IgG beads in co-precipitation assay were identified by liquid chromatography plus a type LC1000-LTQ tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS, Thermo Scientific). The obtained data were automatically searched against the genomic database of L. interrogans strain Lai in GenBank (accession No.: NC_004342.2) using Proteome Discoverer 1.4 software.

2.16. Platelet aggregation and inhibition tests

In the platelet aggregation test, 10 μg rHu-vWF plus 150 μM ristocetin (rHu-vWF/ristocetin) were used as the inducers of Hu-platelet aggregation in vitro [18,26]. Hu-platelets (108) were incubated with 5 μg rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II in MTB at 37 °C for 1 h and then the rHu-vWF/ristocetin-mediated rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-treated Hu-platelet aggregation was detected using a lumiaggregometer (type Model-700, Chrono-Log, USA). On the other hand, rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II was pretreated with rLep-vWA-I-IgG or rLep-vWA-II-IgG at 37 °C for 1 h and then the rLep-vWA-I-IgG or rLep-vWA-II-IgG to reverse the role of rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II on inhibition of rHu-vWF/ristocetin-mediated Hu-platelet aggregation was detected as above.

2.17. Detection of signal kinase phosphorylation in platelet aggregation

Hu-platelets (108) were incubated with 5 μg rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II in MTB at 37 °C for 1 h. The Hu-platelets were precipitated by a 750 ×g centrifugation for 15 min at room temperature. After washing thoroughly with PBS and centrifugation, the Hu-platelet pellets were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime BioTech, China). The lysates were centrifuged at 3000 ×g for 10 min to remove Hu-platelet debris. The supernatants were collected to detect protein concentration using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific) and then were submitted to SDS-PAGE and electro-transferring onto PVDF membrane (Millipore). The phosphorylation levels of PI3K/AKT, ERK, PLC and PKC were detected by Western Blot assay using AKT, ERK1/2, PLC and PKC Phosphorylation Detection Kits (Cell Signaling, USA). In the assays, 10 μg rHu-vWF plus 150 μM ristocetin (rHu-vWF/ristocetin) were used as the control [26,28].

2.18. Measurement of nitric oxide, cGMP, TXA2 and ADP in platelets

Hu-platelets (108) were incubated with 5 μg rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II in MTB at 37 °C for 1 h. The Hu-platelets were lysed and then centrifuged as above. The OD540 or OD450 values reflecting the nitric oxide (NO) or cGMP levels in the supernatants were measured using a Griess's Diazotization NO Assay Kit (Promega, USA) or a cGMP Assay Kit (R&D) by spectrophotometry. The supernatants were diluted at 1:50 with the assay buffer and then the OD450 values reflecting TXB2 levels were measured using a TXB2 Assay Kit (R&D) by spectrophotometry. Besides, the Hu-platelets were precipitated as above for homogenization in the assay buffer and then centrifuged at 10,000 ×g for 10 min. The supernatants were diluted with 50-fold volumes of the assay buffer for detecting the released ADP at the OD570 using an ADP Assay Kit (Abcam) by spectrophotometry. In the detection, 10 μg rHu-vWF plus 150 μM ristocetin (rHu-vWF/ristocetin) were used as the control [26,28].

2.19. Measurement of free Ca2+ in platelets

Hu-platelets (108) were incubated with 5 μg rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II in MTB at 37 °C for 1 h. The Hu-platelets were precipitated and washed as above. The Hu-platelet pellets were suspended in the assay buffer and then incubated with free Ca2+ Fluo-4 AM fluorescence probe at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by an additional incubation at room temperature for 30 min. The fluorescence intensity (FI) values reflecting free Ca2+ levels in the Hu-platelets using a Fluo-4 AM Calcium Assay Kit (Molecular Probes, USA) by laser confocal microscopy (type LSM510, Zeiss, Germany) with 494/516 nm excitation/emission wavelength. In the detection, 10 μg rHu-vWF plus 150 μM ristocetin (rHu-vWF/ristocetin) were used as the control [26,28].

2.20. Functional determination of products of vwa-I528 and vwa-II603 mutants

Previous studies confirmed that the point-mutation of some certain amino acid residues at the GPIb-binding sites in vWF-A domains of vWF caused the decrease of vWF-platelet combination and vWF-induced platelet aggregation [31,32]. The generation of point-mutated vwa-I and vwa-II gene segments containing entire vWF-A superfamily domains (vwa-I528 and vwa-II603), the expression of vwa-I528 and vwa-II603 segments in E. coli and the extraction of target recombinant products were shown in Supplemental Information. The Hu-GPIbα-binding and Hu-platelet aggregation-inhibiting abilities of point-mutated rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II proteins were determined by flow cytometry, SPR and ITC detection, and Hu-platelet aggregation inhibition test as described above.

2.21. Measurement of vwa-I and vwa-II mRNAs during infection of HUVEC

HUVEC (106 per well) was seeded in 6-well culture plates (Corning, USA) for a pre-incubation in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C overnight. Freshly-cultured L. interrogans strain Lai was centrifuged at 13,800 ×g for 15 min at 15 °C and then washed twice with PBS. The harvested leptospires were counted under a dark-field microscope with a Petroff-Hausser counting chamber (Fisher Scientific) [33]. The cells were infected with the spirochete at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 (100 leptospires per host cell) for 1, 2, 4, 8 or 12 h [33,34], and then lysed with 0.05% NaTDC-PBS. The lysates were centrifuged at 350 ×g for 5 min (4 °C) to remove cell debris, and the supernatants were centrifuged at a 10,000 ×g for 30 min (4 °C) to precipitate leptospires. Using rabbit anti-L. interrogans strain Lai-IgG as the primary antibody and Alexa-Fluor488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit-IgG (Abcam), the integrity of leptospires were observed under a laser confocal microscope (LSM510-Meta, Zeiss, Germany) (495/519 nm excitation/emission wavelengths for Alexa-Fluor488 detection) [25], in which the leptospires from culture in EMJH medium was used as the control. Total leptospiral RNAs were extracted using a TRIzol® Max™ Bacterial RNA Isolation kit (Invitrogen, USA) plus a gDNA Eraser Kit (TaKaRa) and then quantified by ultraviolet spectrophotometry. cDNAs from the RNAs were synthesized using a RTase cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa). Using the cDNAs as templates, the vwa-I-mRNA and vwa-II-mRNA levels were assessed by real-time fluorescence quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) using a SYBR® Premix Ex-Taq™ Kit (TaKaRa) in an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (ABI, USA). The primers used are listed in Table 1. In the qRT-PCR, 16S rRNA gene of the spirochete was used as the internal reference while the spirochetes from EMJH medium (28 °C) and incubated in 2.5% FCS RPMI-1640 medium (37 °C) were used as the controls. The qRT-PCR data were analyzed using the ΔΔCt model and randomization test in REST 2005 software [20,34].

2.22. Detection of Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II expression and secretion of L. interrogans during infection of HUVEC

HUVEC was infected with L. interrogans strain Lai as described above. The co-cultures were lysed and then centrifuged as above to separate supernatants and leptospires. Subsequently, the integrity of leptospires from the co-cultures after lysis were detected by confocal microscopy as described above. The total proteins in the supernatants were extracted by trichloroacetic acid-acetone precipitation method [24], while the total leptospiral proteins were extracted by ultrasonical breakage and centrifugation as above, followed by detection of protein concentration as above. Using rabbit rLep-vWA-I-IgG or rLep-vWA-II-IgG as the primary antibody and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit-IgG (Abcam) as the secondary antibody, Western Blot assay was used to detect Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II in the two protein specimens. The immunoblotting signals were quantified for analysis by densitometry (gray scale determination) using an image analyzer (Bio-Rad, USA) [33]. In the assays, LipL41 or Sph2 and FliY, a stable transmembrane lipoprotein or a secreted hemolysin and cytosolic protein of L. interrogans, were used as the expression or secretion controls [20].

2.23. Secretion inhibition test

L. interrogans strain Lai was pre-treated with 0.1 mM PAβN, a T1SS inhibitor, 2.5 mM NaN3 and 30 mM NaSCN, the T2SS inhibitors, or 10 mM Aurodox (Sigma), a T3SS inhibitor, for 6 h at 37 °C [35]. The secretion of Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II of the spirochete during infection of HUVEC cells was detected by Western Blot assay as above.

2.24. Detection of rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-induced hemorrhage in mice

Each of C3H/HeJ or C57BL/6 mice was intravenously injected with 100 μg rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II in 0.1 mL autoclaved PBS and eight animals were used per group. The animal lung, liver and kidney tissues as well as the peripheral blood plasma samples were collected on days 3 and 7 after injection for histopathological examination after HE-staining as well as for detection of prothrombin time (PT), thrombin time (TT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), thrombin generation time (TGT), fibrinogen (F—I) and fibrin degradation product (D-dimer) concentrations using an Auto-Blood Coagulation Analyzer (Sysmex, Japan) [16,36]. In addition, the coagulation time (CT) using Lee-White method, prothrombin (F-II) and prothrombin fragments 1 + 2 (F1 + 2) concentrations using ELISA, and thrombin generation time (TGT) using a Hemostasis System Analyzer (Haemoscope, USA) of the blood plasma samples were also detected as previously described [16]. On the other hand, the same concentration of rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II were pre-incubated with rLep-vWA-I-IgG or rLep-vWA-II-IgG at 37 for 1 h and then intravenously injected into the mice for histopathological examination as above. In the detection, the mice injected with the same volume of autoclaved PBS were used as the control.

2.25. Statistical analysis

Data from a minimum of three independent experiments were averaged and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test were used to determine significant differences. Statistical significance was defined as p < .05.

3. Results

3.1. Extensive distribution of vwa-I and vwa-II genes in pathogenic Leptospira genospecies

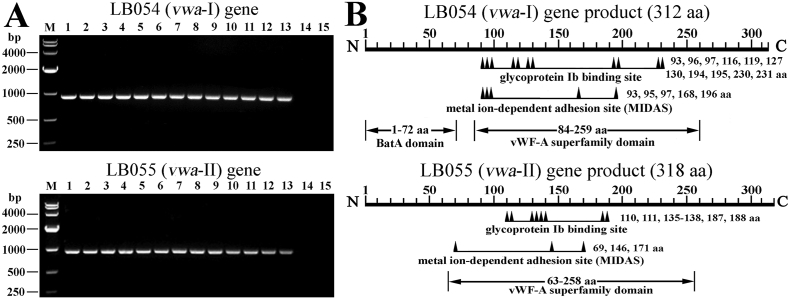

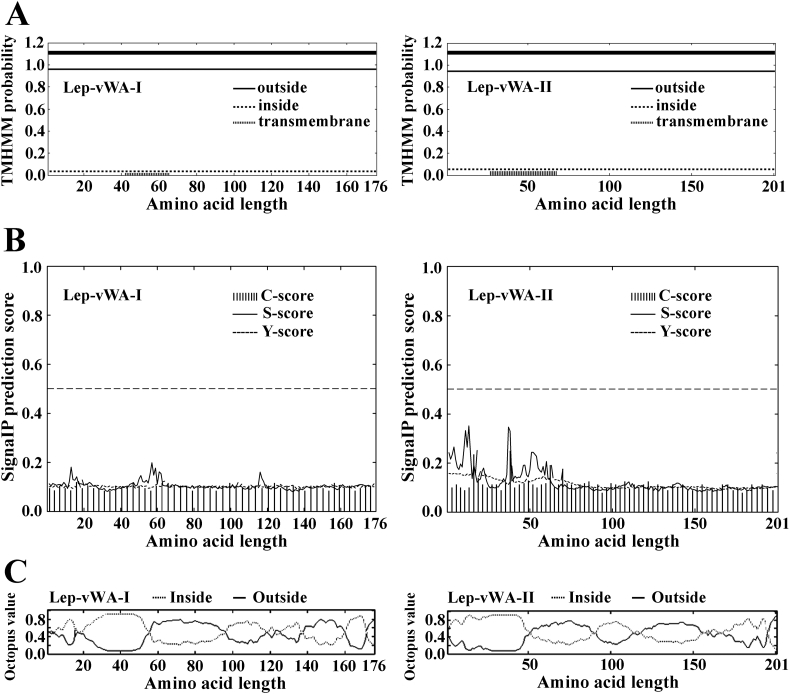

The PCR and sequencing data revealed that all the 13 tested strains of pathogenic of L. interrogans, L. borgpetersenii or L. weilii but not the 2 tested strains of saprophytic L. biflexa, possess both the LB054 (vwa—I) and LB055 (vwa-II) genes (Fig. 1A) with the nucleotide or amino acid sequence identities of 98.9%–99.8% or 98.9%–100% and 98.7%–99.9% or 98.0%–100% (GenBank accession No.: MG744315-MG744327 and MG744328-MG744340) compared to the reported same genes (GenBank accession No.: NC_004342.2). Moreover, the vwa-I or vwa-II genes of L. interrogans strain Lai had higher amino acid sequence identities (85.6%–100% or 74.4%–100%) compared to those from all the 13 strains belonging to 9 serogropus and 10 serovars of 5 pathogenic Leptospira genospecies in GenBank (Table 2). Bioinformatic analysis indicated that the vwa-I and vwa-II genes contain vWF-A superfamily domains (Fig. 1B). Although PsortB software predicted that the product of vwa-I gene was located in cytoplasmic membrane and the position of vwa-II gene product was unknown, TMHMM software predicted the two products as exoproteins without signal peptide sequences and transmembrane regions while Octopus software presented the similar possibility of the two products located the inside or outside of leptospiral cells (Supplementary Fig. S1). The data suggested that vwa-I and vwa-II genes are required by pathogenic but not non-pathogenic saprophytic Leptospira strains.

Fig. 1.

Distribution and domains of LB054 and LB055 genes in leptospiral strains.

(A). The PCR products of leptospiral LB054 (vwa-I) and LB055 (vwa-II) genes, determined by PCR. Lane M: DNA marker. Lanes 1–13: amplicoms of the vwa-I or vwa-II genes from thirteen pathogenic strains belonging to L. interrogans, L. borgpetersenii or L. weilii. Lanes 14–15: no amplicoms of vwa-I or vwa-II genes from two saprophytic strains of L. biflexa.

(B). Predicted functional domains in LB054 (vwa—I) and LB055 (vwa-II) genes of L. interrogans strain Lai.

Table 2.

Identity of the amino acid sequences of leptospiral vwa-I/II-like genes.

| Genospecies | Serogroup | Serovar | Strain | Genes | GenBank No. | Sequence Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. interrogans⁎ | Icterohaemorrhagiae | Lai | Lai | vwa-I/vwa-II | MG744315/744328 | 100/100⁎⁎⁎ |

| Canicola | Canicola | Lin | vwa-I/vwa-II | MG744316/744329 | 99.7/99.0 | |

| Pyrogenes | Pyrogenes | Tian | vwa-I/vwa-II | MG744317/744330 | 100/99.0 | |

| Autumnalis | Autumnalis | Lin4 | vwa-I/vwa-II | MG744318/744331 | 99.7/99.7 | |

| Australis | Australis | 65–9 | vwa-I/vwa-II | MG744319/744332 | 100/99.7 | |

| Pomona | Pomona | Luo | vwa-I/vwa-II | MG744320/744333 | 99.7/98.0 | |

| Grippotyphosa | Grippotyphosa | Lin6 | vwa-I/vwa-II | MG744321/744334 | 99.0/98.7 | |

| Hebdomadis | Hebdomadis | 56,069 | vwa-I/vwa-II | MG744322/744335 | 99.7/99.0 | |

| L. interrogans⁎⁎ | Icterohaemorrhagiae | Lai | IPAV | RS18585/18590 | NC_017552.1 | 100/100 |

| Icterohaemorrhagiae | Copenhageni | Fiocruz L1–130 | RS18185/18190 | NC_005824.1 | 100/99.4 | |

| Icterohaemorrhagiae | Copenhageni | Piscina | RS19075/19080 | NZ_CP018147.1 | 99.0/99.4 | |

| Canicola | Canicola | 114 | 19,360/19365 | CP022884.1 | 99.7/98.4 | |

| Pyrogenes | Manilae | UP-MMC-NIID | RS17985/17990 | NZ_CP011932.1 | 99.7/99.7 | |

| Australis | Bratislava | PigK151 | RS18650/18655 | NZ_CP011411.1 | 100/99.4 | |

| Grippotyphosa | Linhai | 56,609 | RS18625/18630 | NZ_CP006724.1 | 99.7/98.4 | |

| Sejroe | Hardjo-prajitno | Hardjoprajitno | RS18285/18290 | NZ_CP013148.1 | 100/99.7 | |

| L. borgpetersenii⁎ | Javanica | Javanica | M10 | vwa-I/vwa-II | MG744323/744336 | 99.3/100 |

| Ballum | Ballum | Pishu | vwa-I/vwa-II | MG744324/744337 | 99.7/100 | |

| Tarassovi | Tarassovi | 55–52 | vwa-I/vwa-II | MG744325/744338 | 99.7/99.7 | |

| Mini | Mini | Nan10 | vwa-I/vwa-II | MG744326/744339 | 99.7/100 | |

| L. borgpetersenii⁎⁎ | Ballum | Ballum | 56,604 | RS16395/16400 | NZ_CP012030.1 | 86.2/76.7 |

| Sejroe | Hardjo | BK-6 | RS16740/16745 | NZ_CP015045.1 | 85.6/74.4 | |

| L. weilii⁎ | Manhao | Manhao 2 | L105 | vwa-I/vwa-II | MG744327/744340 | 100/99.3 |

| L. santarosai⁎⁎ | / | Shermani | LT 821 | RS17415/17420 | NZ_CP006695.1 | 87.8/73.5 |

| L. alstonii⁎⁎ | / | / | GWTS #1 | RS19530/19535 | NZ_CP015218.1 | 83.0/66.9 |

| L. mayottensis⁎⁎ | / | / | MDI272 | 19,315/19320 | CP030148.1 | 87.5/75.8 |

The sequences from the present study by PCR and sequencing.

The sequences from GenBank.

The amino acid sequence identity from LB_054 (vwa—I) and LB_055 (vwa-II) genes in GenBank (NC_004343.2).

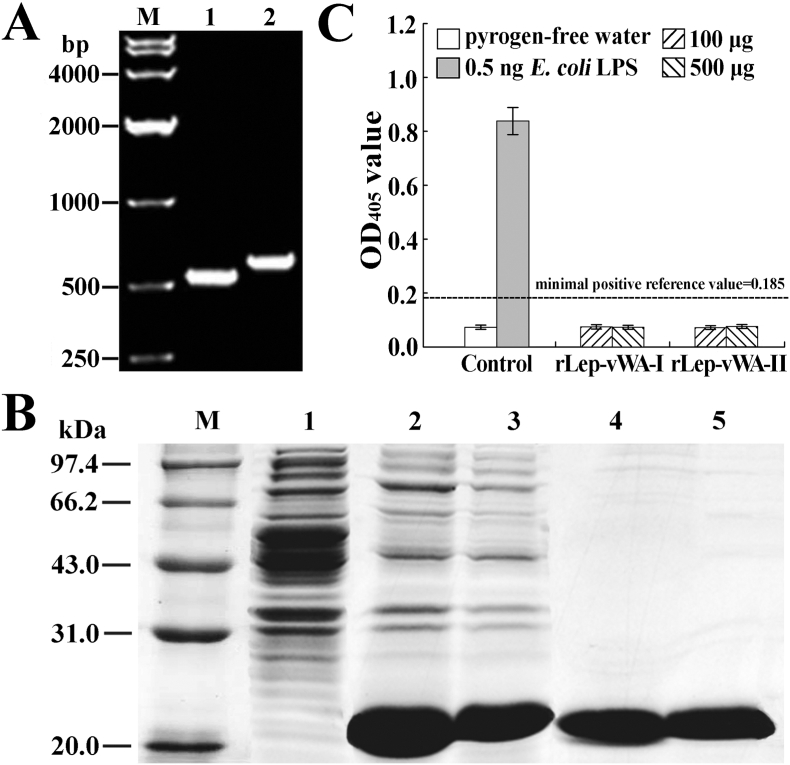

3.2. Characterization of recombinant expression products of vwa-I and vwa-II genes

The generated prokaryotic expression systems could express the target recombinant proteins (rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II) encoded by the wild-type or point-mutated vwa-I and vwa-II genes of L. interrogans strain Lai (Supplementary Fig. S2A and S4B). The spectrophotometric limulus amebocyte lysate test showed that no lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was detectable in all the rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II extracts after endotoxin-removing treatment (Supplementary Fig. S2C and S4D).

3.3. Hu-Platelet- and GPIbα-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II

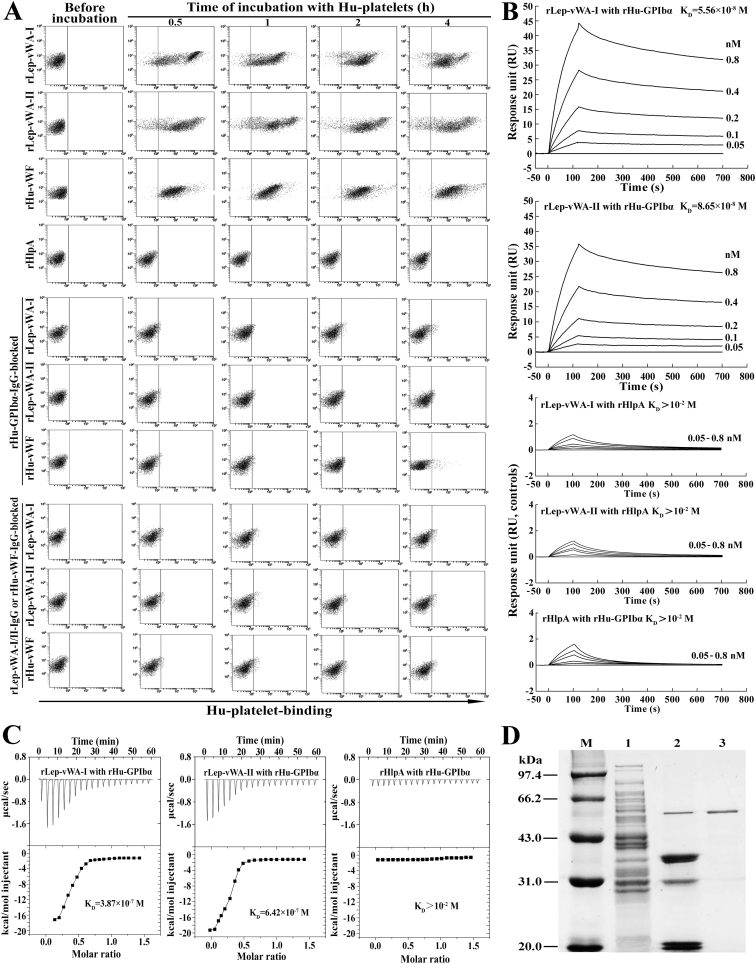

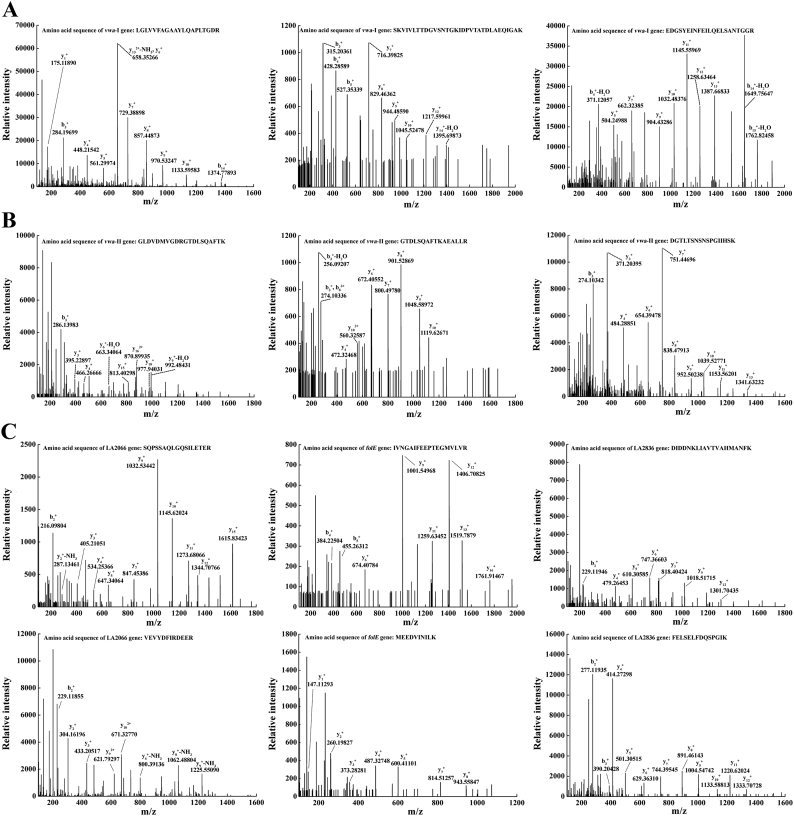

The flow cytometric examination confirmed that both the rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II rapidly combined with Hu-platelets with the 94.7% and 92.4% maximal human (Hu)-platelet-binding percentages (Fig. 2A and Table 3). When the Hu-platelets were blocked with rHu-GPIbα-IgG, as well as the rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II was blocked with rLep-vWA-I-IgG or rLep-vWA-II-IgG, the Hu-platelet-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II was absent (Fig. 2A and Table 3). The surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and isothermal titration calorimetric (ITC) detection, the two sensitive and reliable methods to determine protein-protein binding [29,30], revealed that the equilibrium association constant (KD) values reflecting the binding ability of rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II with rHu-GPIbα were 5.56 × 10−8 and 3.87 × 10−7 M or 8.65 × 10−8 and 6.42 × 10−7 M (Fig. 2B and C). In particular, the co-precipitation test showed that the rHu-GPIbα captured five protein bands from total proteins of L. interrogans strain Lai (Fig. 2D), and the LC-MS/MS identified two of the captured proteins (~36 kDa) as the products of vwa-I and vwa-II genes according to their cleaved peptide sequences (LGLVVFAGAAYLQAPLTGDR, SKVIVLITDGVSNTGK IDPVTATDLAEQIGAK and EDGSYEINFEILQELSANTGGR for vWA-I, and GLDVDM VGDRGTDLSQAFTK, GTDLSQAFTKAEALLR and DGTLTSNSNSPGIIHSK for vWA-II) (Supplementary Fig. S3A and 3B). The other three captured proteins were identified as the products of LA2066 (~32 kDa, hypothetical protein), LA4255 (~21 kDa, FolE) and LA2836 (~19 kDa, hypothetical protein) (Supplementary Fig. S3C). The data suggested that the products of L. interrogans vwa-I and vwa-II genes have a specific Hu-platelet- or Hu-GPIbα-binding ability.

Fig. 2.

Platelet- and GPIbα-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II.

(A). Hu-platelet-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II, determined by flow cytometry. rHu-vWF and rHlpA, a commercial recombinant human vWF and a recombinant hemolysin of L. interrrogans, were used as the controls.

(B). rHu-GPIbα-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II, determined by SPR. rHlpA, a recombinant hemolysin of L. interrrogans, was used as the control.

(C). rHu-GPIbα-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II, determined by ITC. The legend is the same as shown in C.

(D). rHu-GPIbα-captured leptospiral proteins, determined by co-precipitation test. Lane M: protein marker. Lane 1: total proteins from L. interrogans strain Lai. Lane 2: proteins released from protein-A-GPIbα-IgG beads. Lane 3: rHu-GPIbα control.

Table 3.

Hu-platelet-binding percentages of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-IIΔ.

| Group (n = 3) | Platelet-binding percentage (%, 104 platelets) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 h | 1 h | 2 h | 4 h | |

| rLep-vWA-I | 89.9 ± 3.6 | 90.7 ± 3.8 | 94.7 ± 4.2 | 93.3 ± 5.6 |

| rLep-vWA-II | 88.2 ± 3.1 | 90.2 ± 2.9 | 92.4 ± 3.5 | 90.7 ± 2.8 |

| rHu-vWF | 93.7 ± 3.5 | 94.4 ± 2.5 | 95.2 ± 2.1 | 93.5 ± 2.9 |

| rHu-GP1bα-IgG-blocked rLep-vWA-I | 3.5 ± 0.5⁎ | 3.7 ± 0.4⁎ | 4.2 ± 0.4⁎ | 5.4 ± 0.5⁎ |

| rHu-GP1bα-IgG-blocked rLep-vWA-II | 3.9 ± 0.5⁎ | 4.2 ± 0.6⁎ | 4.4 ± 0.6⁎ | 5.5 ± 0.5⁎ |

| rHu-GP1bα-IgG-blocked rHu-vWF | 2.5 ± 0.1⁎ | 2.7 ± 0.1⁎ | 3.0 ± 0.2⁎ | 3.1 ± 0.2⁎ |

| rLep-vWA-I-IgG-blocked rLep-vWA-I | 1.5 ± 0.1⁎ | 1.7 ± 0.1⁎ | 1.9 ± 0.1⁎ | 2.0 ± 0.2⁎ |

| rLep-vWA-II-IgG-blocked rLep-vWA-II | 1.7 ± 0.1⁎ | 1.8 ± 0.1⁎ | 2.0 ± 0.1⁎ | 2.1 ± 0.2⁎ |

| rHu-vWFIgG-blocked rHu-vWF | 1.4 ± 0.1⁎ | 1.7 ± 0.1⁎ | 2.1 ± 0.2⁎ | 3.9 ± 0.2⁎ |

The data from experiments such as shown in the Fig. 2A.

p < .05 vs the Hu-platelet-binding percentages of specific IgG-unclocked rLep-vWA-I, rLep-vWA-II or rHu-vWF.

3.4. Inhibition of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II on vWF-mediated platelet aggregation

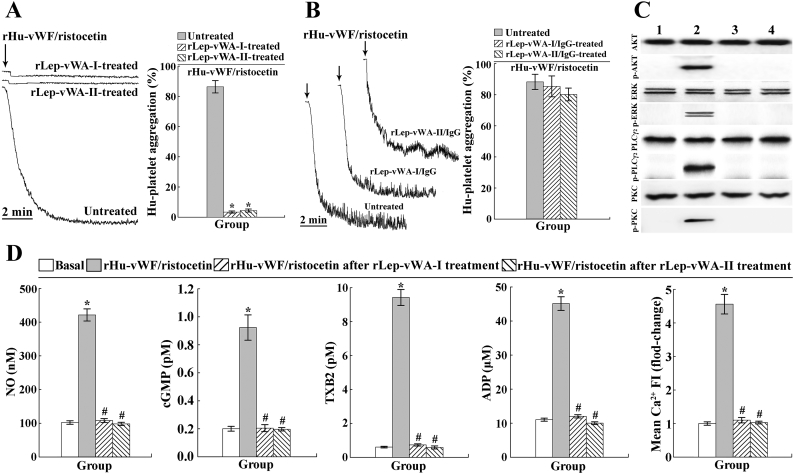

Lumiaggregometer is commonly used to detect platelet aggregation in vitro [26]. Ristocetin, a co-coagulation factor, is necessary for vWF to induce platelet aggregation in vitro [37]. The platelet aggregation test showed that rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II did not cause Hu-platelet aggregation, but could inhibit the rHu-vWF/ristocetin-induced Hu-platelet aggregation (Fig. 3A). However, the inhibition of rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II could be removed by rLep-vWA-I-IgG or rLep-vWA-II-IgG pre-blockage (Fig. 3B). Moreover, no phosphorylation of the AKT, ERK, PLC and PKC as well as no increase of the NO, cGMP, TXA2, free Ca2+ and ADP levels in the rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-binding Hu-platelets could be found (Fig. 3C and D). The data suggested that the products of L. interrogans vwa-I and vwa-II genes can not induce human platelet aggregation but block the vWF-mediated platelet aggregation.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II on vWF-mediated Hu-platelet aggregation.

(A). Inhibition of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II on vWF/ristocetin-induced Hu-platelet aggregation, determined by platelet aggregation test.

(B). Reversed inhibition of rLep-vWA-I-IgG and rLep-vWA-II-IgG on rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II blockage of vWF/ristocetin-induced Hu-platelet aggregation, determined by platelet aggregation test.

(C). No phosphorylation of the AKT, ERK, PLC and PKC in rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-treated Hu-platelets, determined by Western Blot assay. Lane 1: normal Hu-platelets. Lane 2: vWF/ristocetin-treated Hu-platelets. Lanes 3 and 4: rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-treated Hu-platelets.

(D). No increase of the NO, cGMP, TXA2, free ADP and Ca2+ levels in rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-treated Hu-platelets, determined by spectrophotometry and confocal microscopy.

3.5. GPIbα-binding sites in Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II

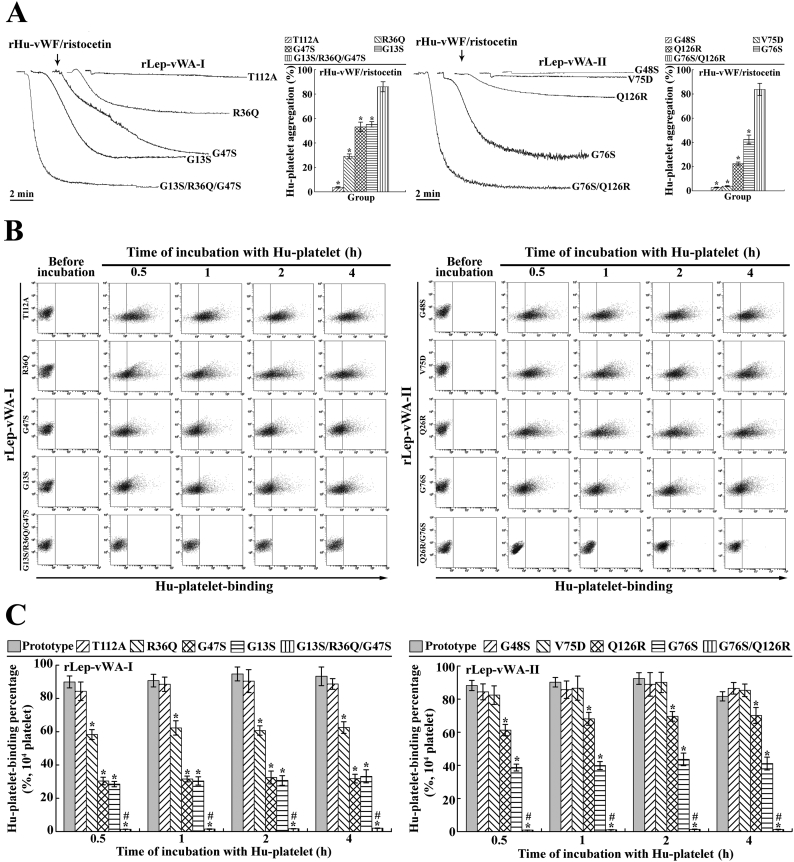

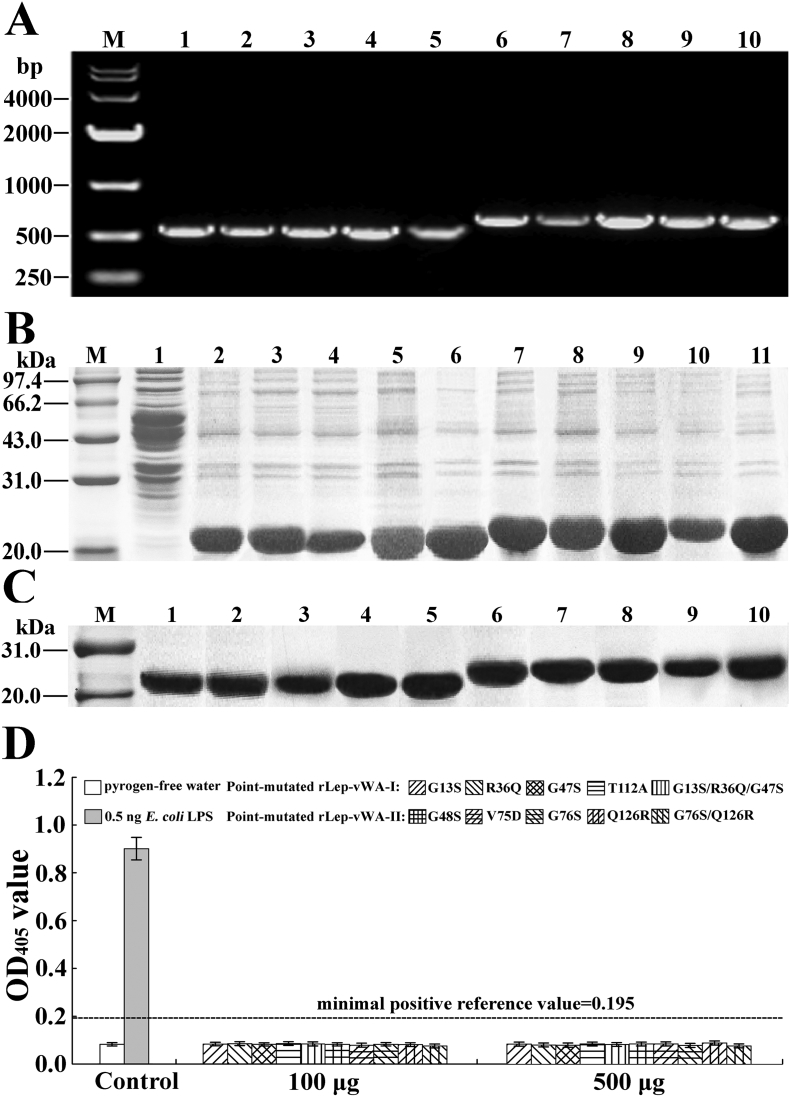

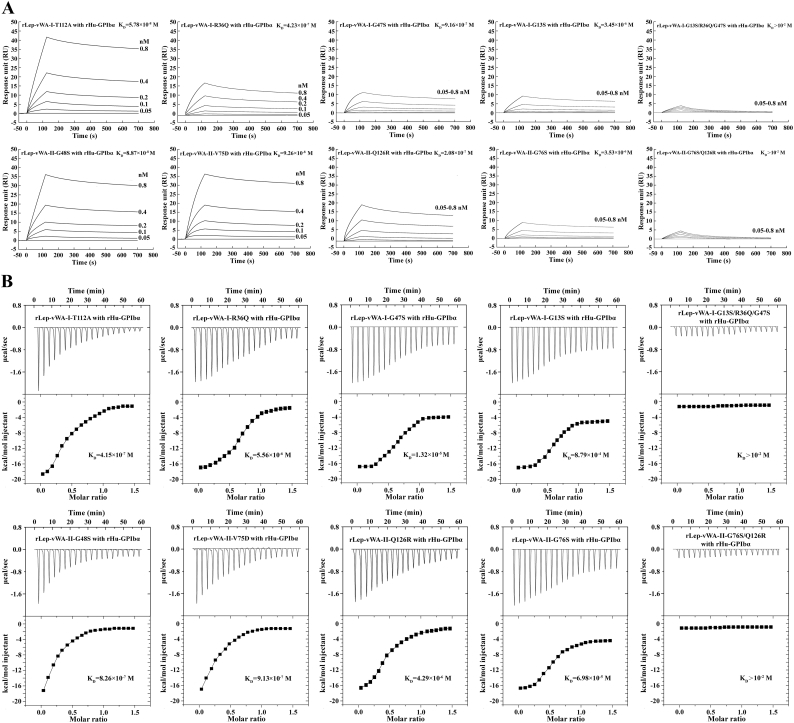

Previous studies reported that the point-mutation of some certain amino acid residuals in the region-A of human vWF caused the decrease of vWF-platelet binding and attenuation of vWF-mediated platelet aggregation [31,32]. The flow cytometric examination revealed that the recombinant single point-mutated products of L. interrogans vwa-I and vwa-II genes, rLep-vWA-I-G13S, rLep-vWA-I-R36Q, rLep-vWA-I-G47S, rLep-vWA-II-G76S and rLep-vWA-II-Q126R but not rLep-vWA-I-T112A, rLep-vWA-II-G48S and rLep-vWA-II-V75D, presented a significant decrease of Hu-platelet-binding and rHu-vWF/ristocetin-induced Hu-platelet aggregation-inhibiting abilities, compared to the prototypes of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II (Fig. 4). In addition, the multiple point-mutated rLep-vWA-I-G13S/R36Q/G47S and rLep-vWA-II-G76S/Q126R could not bind to Hu-platelets and inhibit rHu-vWF/ristocetin-induced Hu-platelet aggregation (Fig. 4). The SPR and ITC detection also confirmed the significant attenuation of rHu-GPIbα-binding ability of the five single point-mutated rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II proteins and absence of rHu-GPIbα-binding ability of the two multiple point-mutated rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II protein (Supplementary Fig. S5). The data suggested that the G13/R36/G47 in Lep-vWA-I and G76/126R in Lep-vWA-II act as human platelet GPIbα-binding sites.

Fig. 4.

GPIbα-binding sites in products of vwa-I528 and vwa-II603 mutants.

(A). Decreased inhibition of point-mutated rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II on vWF/ristocetin-induced Hu-platelet aggregation, determined by platelet aggregation test.

(B). Decreased Hu-platelet-binding ability of point-mutated rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II, determined by flow cytometry.

(C). Statistical summary of the Hu-platelet-binding percentages of point-mutated rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II. Statistical data from experiments such as shown in B. Bars show the means ± SD of three independent experiments. *: p < .05 vs the Hu-platelet-binding percentages of prototypic rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II. #: p < .05 vs the Hu-platelet-binding percentages of single point-mutated rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II.

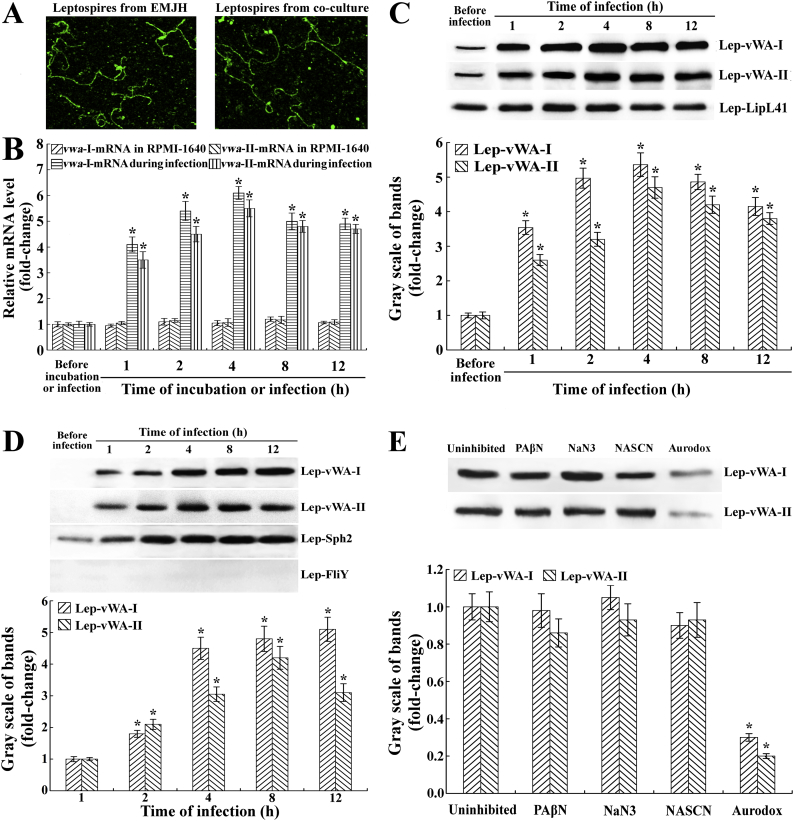

3.6. Increase of expression and secretion of Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II during infection

The cofocal microscopic examination confirmed the integrity of leptospires from the lysates of Leptospira-cell co-cultures (Fig. 5A). The qRT-PCR and Western Blot assay showed that the Lep-vWA-I or Lep-vWA-II mRNA level and protein expression of L. interrogans strain Lai were significantly increased during infection of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) (Fig. 5B and C). In particular, the secretion of Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II was also observed during infection (Fig. 5D). The Aurodox, a type 3 secretion system (T3SS) inhibitor, but not the T1SS and T2SS inhibitors (PAβN, NaN3 and NASCN) [38], caused a significant decrease in Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II secretion (Fig. 5E). The data suggested that vwa-I and vwa-II genes are required by L. interrogans during infection and the vwa-I and vwa-II gene products can be secreted through leptospiral T3SS.

Fig. 5.

Increase of vwa-I and vwa-II gene expression and secretion during infection.

(A) The integrity of leptospires from the lysates of Leptospira-cell co-cultures, examined by cofocal microscopy.

(B) Increase of vwa-I- or vwa-II-mRNA levels in L. interrogans strain Lai during infection of HUVEC, determined by qRT-PCR. Bars show the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. The vwa-I- or vwa-II-mRNA levels in the spirochete from EMJH medium (before infection) were set as 1.0. *: p < .05 vs the vwa-I- or vwa-II-mRNA levels in the spirochete before infection or in incubation with RPMI-1640 medium at 37 °C.

(C). Increase of Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II expression in L. interrogans strain Lai during infection of HUVEC, determined by Western Blot assay. LipL41, a leptospiral outer membrane lipoprotein, was used as the control. The immunoblotting bands reflecting Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II expression levels during infection were quantified by gray scales. Bars show the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. The gray scale values of immunoblotting bands from the spirochete in EMJH medium (before infection) were set as 1.0. *: p < .05 vs the gray scale values reflecting the expression levels of Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II of the spirochete before infection.

(D). Secretion of Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II of L. interrogans strain Lai during infection of HUVEC, determined by Western Blot assay. Sph2, a secreted leptospiral hemolysin, and FliY, a leptospiral cytosolic protein, were used as the controls. The rest of legend is the same as in B but for detection of Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II secretion. *: p < .05 vs the gray scale values reflecting the secreted Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II levels of the spirochete before infection.

(E). Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II secretion through T3SS during infection of HUVEC, determined by Western Blot assay. PAβN or Aurodox is the T1SS or T3SS inhibitor while NaN3 and NaSCN are T2SS inhibitors. The rest of legend is the same as in B but for determination of Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II secretion pathways. *: p < .05 vs the gray scale values reflecting the secreted Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II levels of the spirochete before infection.

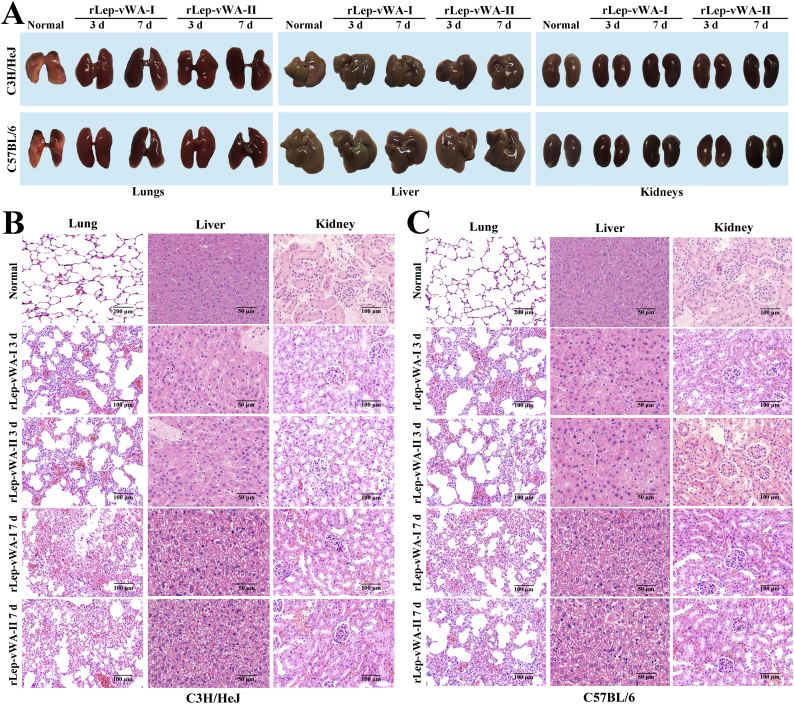

3.7. Hemorrhage induced by rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II in mice

The gross pathological examination showed that all the lungs of rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-injected mice presented visible hyperemia and swelling but the livers and kidneys had no visible changes compared to those of normal mice (Fig. 6A). The pathological examination showed that both rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II caused the pulmonary diffuse hemorrhage with interstitial pneumonia and extensive renal focal hemorrhage (Fig. 6B and C). When rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II was pre-blocked by rLep-vWA-I-IgG or rLep-vWA-II-IgG, the hemorrhagic phenomenons in the lung and kidney tissues of mice were absent (Supplementary Fig. S6). The data suggested that the products of L. interrogans vwa-I and vwa-II genes act as hemorrhage inducers in mice.

Fig. 6.

rLep-vWA-I- and rLep-vWA-II-induced hemorrhage in mice.

(A). The gross pathological changes of lungs, livers and kidneys of rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-injected C3H/HeJ or C57BL/6 mice.

(B). rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-induced hemorrhage in C3H/HeJ mice, observed by microscopy after HE-staining.

(C). rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-induced hemorrhage in C57BL/6 mice, observed by microscopy after HE-staining.

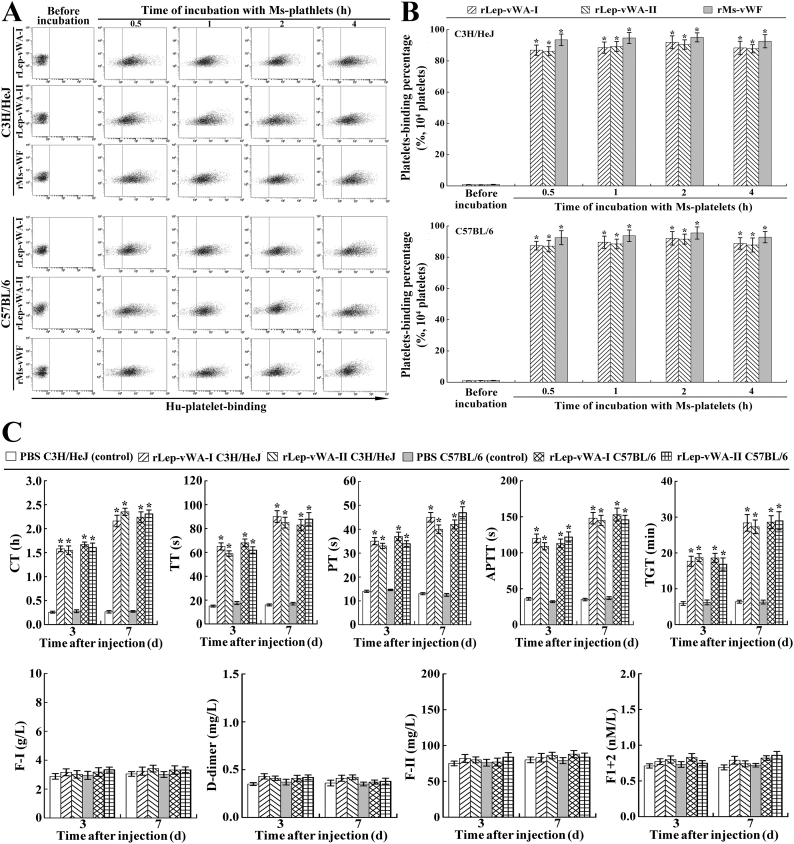

3.8. Ms-platelet-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I and blood coagulation dysfunction

The flow cytometric examination confirmed that rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II could rapidly bind to Ms-platelets form C3H/HeJ or C57BL/6 mice with the 91.9% and 90.5% or 92.1% and 91.6% maximal human (Hu)-platelet-binding percentages (Fig. 7A and B). On the other hand, the coagulation time (CT), prothrombin time (PT), thrombin time (TT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) and thrombin generation time (TGT) of peripheral blood specimens from the two rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-injected mice presented a 2.36–8.81 fold extension but the fibrinogen (coagulation factor I, F—I), prothrombin (coagulation factor II, F-II), prothrombin degradation fragments (F1 + 2) and fibrin degradation product (D-dimer) levels had no significant changes, compared to the normal mice (Fig. 7C). The data suggested that the products of L. interrogans vwa-I and vwa-II induce hemorrhage in mice due to attenuation or dysfunction of platelet aggregation.

Fig. 7.

Ms-platelet-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I and blood coagulation dysfunction.

(A). Ms-platelet-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II, determined by flow cytometry. rHu-vWF, a commercial recombinant mouse vWF, was used as the control.

(B). Statistical summary of the Ms-platelet-binding percentages of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II. Statistical data from experiments such as shown in A. Bars show the means ± SD of three independent experiments. *: p < .05 vs the normal Ms-platelets.

(C). Extension of the CT, PT, TT, APTT and TGT as well as no change of the F—I, D-dimer, F-II and F1 + 2 levels of peripheral blood specimens from rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-injected mice, determined by using an Auto-Blood Coagulation Analyzer and ELISA. *: p < .05 vs the CT, PT, TT, APTT and TGT of peripheral blood specimens from normal mice.

4. Discussion

Leptospira is a large group of Gram-negative helical prokaryotic microbes that can be classified into pathogenic and non-pathogenic saprophytic Leptospira genospecies [1,2,11]. Both the pathogenic and saprophytic Leptospira genospecies express surface LPS (i.e. endotoxin) [39], but only the former is pathogenic due to expression of many invasive and virulence factors such as the ColA collagenase, the LigB adhensin, the Mce invasive protein and the OMP047 apoptotic inducer [20,25,34,40]. Unlike saprophytic Leptospira, which live in the natural environment, pathogenic Leptospira need to invade into animal hosts for propagation. This requires certain genetic diversity between the saprophytic and pathogenic Leptospira genospecies. In the present study, we found that only the strains from pathogenic Leptospira, but not from saprophytic Leptospira genospecies, possess sequence-conserved vwa-I and vwa-II genes. In particular, the expression of L. interrogans vwa-I and vwa-II genes as well as the secretion of their products (Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II) were observed during infection of human vascular endothelial cells. However, the T3SS inhibitor (Aurodox) but not the T1SS and T2SS inhibitors could inhibit the secretion of Lep-vWA-I and Lep-vWA-II. Earlier studies reported that L. interrogans may possess an incomplete type III secretion system (T3SS) because no genes could be predicted to encode a transmembrane channel in the T3SS for transport of proteins [41,42]. However, a recent study showed that the product of the gspD gene in L. interrogans strain Lai was predicted as a YscC-like protein, a porin for protein secretion in T3SS of Yersinia pestis [43]. Our data indicate that the pathogenic but not saprophytic Leptospira genospecies possess vwa-I and vwa-II genes and the products of vwa-I and vwa-II genes can secrete through T3SS during infection.

Many prokaryotic pathogens, such as Escherichia coli, Shigella dysenteriae, Helicobacter pylori, Clostridium difficile and Rickettsia species, can cause hemorrhagic injury of infected hosts [[44], [45], [46], [47], [48]]. LPS has been confirmed as a strong causative agent of hemorrhage due to the inflammation-mediated increase of vascular permeability, damage of vascular endothelial cells and basement membrane, and inhibition of platelet adhesion and aggregation [[49], [50], [51]]. However, the biological activity of leptospiral LPS is much lower than that of E. coli LPS, while hemorrhage in leptospirosis is much more severe [6,13,25,39]. Therefore, pathogenic Leptospira genospecies must produce some factors other than leptospiral LPS in order to induce hemorrhage during infection.

GPIb is a platelet transmembrane protein composed of two α-subunits and two β-subunits [52]. During the process of vWF-induced platelet aggregation in vivo, vWF first binds to platelets through its vWF-A domain with the leucine-rich repeat N-terminal (LRRNT) domain of GPIbα to form a vWF-GPIb-IX-V complex that further initiates PI3K/AKT-PLC/PKC signaling to cause talin/integrin-dependent platelet aggregation [19,28]. Therefore, the GPIbα-binding ability of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II, the products of L. interrogans vwa-I and vwa-II containing vWF-A superfamily domains, is the key feature of these two proteins for their ability to induce hemorrhage by competitive blockage of vWF. In the present study, both rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II were able to interact with Hu-platelets but also bind to rHu-GPIbα with KD values of 3.87 × 10−7-8.65 × 10−8 M. KD values lower than 10−6 M generally indicate high-affinity protein-protein interactions [29,30]. In particular, latelet aggregation and aggregation inhibition tests confirmed that rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II blocked rHu-vWF/ristocetin-induced Hu-platelet aggregation in vitro. Moreover, this study also identified G13, G47 and R36 in Lep-vWA-I and G76 and Q126 in Lep-vWA-II as the rHu-GPIbα-binding residues. All the data demonstrate that the L. interrogan vwa-I and vwa-II gene products exhibit human platelet GPIbα-biding ability and can cause hemorrhage during leptospirosis by competitive inhibition of vWF-mediated platelet aggregation.

Hemorrhage can be classified as disruptive hemorrhage due to vessel wall injury and diapedetic hemorrhage due to thrombocytopenia and platelet dysfunction and is usually caused by heredopathia, malnutrition, leukemia or microbial infections [16,53]. Younger guinea pigs and Syrian hamsters are more suitable for leptospirosis animal models [54,55], but C3H/HeJ and C57BL/6 mice are also commonly used as the experimental hosts of L. interrogans [56,57]. In particular, commercial experimental reagents for mice but not for guinea pigs and Syrian hamsters are readily available. Animal experiments in our study showed that 100 μg rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II was able to cause severe diffuse diapedetic hemorrhage in lung tissues and extensive focal diapedetic hemorrhage in kidney tissues of mice, while hemorrhage could be blocked by rLep-vWA-I or rLep-vWA-II-IgG. CT, TT, PT, APTT and TGT are common assays to assess coagulation function of blood as well as the prothrombin degradation fragments (F1 + 2) and fibrin degradation product (D-dimer) levels reflect the generation of thrombin from activated prothrombin and formation of fibrin from cleaved fibrinogen [16,36]. Compared to the normal mice, all the coagulation times of peripheral blood specimens from rLep-vWA-I- and rLep-vWA-II-injected mice were extended, but no changes of the fibrinogen (F—I), prothrombin (F-II), F1 + 2 and D-dimer levels were found. In the process of blood coagulation, the aggregated platelets induced by vWF can produce coagulation factor V and combine with coagulation factor X to form a complex that cleaves prothrombin into thrombin to cause the conversion of fibrinogen into fibrin [17,58,59]. Moreover, the rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-injected mice also presented interstitial pneumonia. Previous studies revealed that heme, heat shock protein-60 (HSP60) and adenosine 5′ triphosphate released from erythrocytes can induce inflammation through NLRP3 inflammasome, NF-κB and Ca2+/PKC signaling pathways of macrophages and vascular endothelial cells [[60], [61], [62]]. Therefore, the interstitial pneumonia observed in the mice may be caused by the released components of erythrocytes. All the data indicate that the products of L. interrogan vwa-I and vwa-II genes can cause hemorrhage in mice probably due to dysfunction and disorder of platelet aggregation.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Supplementary material

Fig. S1.

Predicted characteristics of vwa-I and vwa-II gene products.

(A). Structure and location of vwa-I and vwa-II gene products, predicted using TMHMM software.

(B). No signal peptide sequence in vwa-I or vwa-II gene product, predicted using SignalP-4.1 software.

(C). Position of vwa-I or vwa-II gene product, predicted using Octopus software.

Fig. S2.

Expression and extraction of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II.

(A). Amplification fragments of vwa-I and vwa-II gene segments (vwa-I528 and vwa-II603) from L. interrogans strain Lai, detected by PCR. Lane M: DNA marker. Lanes 2 and 3: amplicons of vwa-I and vwa-II gene segments (528 and 603 bp).

(B). Expression and extraction effects of rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II, detected by SDS-PAGE. Lane M: protein marker. Lane 1: wild-type E. coli BL21DE3. Lanes 2 and 3 or 4 and 5: the expressed or extracted rLep-vWA-I (~20.2 kDa) and rLep-vWA-II (~23.1 kDa).

(C). No LPS in rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II extracts, determined by spectrophotometeric limulus test.

Fig. S3.

GPIbα-captured proteins as the products of vwa-I and vwa-II genes.

(A).The cleaved peptide sequences from GPIbα-captured proteins matching to the vwa-I gene product, determined by LC-MS/MS.

(B).The cleaved peptide sequences from GPIbα-captured proteins matching to the vwa-II gene product, determined by LC-MS/MS.

(C).The cleaved peptide sequences from GPIbα-captured proteins matching to the product of LA2066, folE or LA2836 genes, determined by LC-MS/MS.

Fig. S4.

Expression and product extraction of point-mutated vwa-I528 and vwa-II603 segments.

(A). Amplification fragments of point-mutated vwa-I528 and vwa-II603 segments, detected by PCR. Lane M: DNA marker. Lanes 1-5: amplicons of vwa-I-G13S, vwa-I-R36Q, vwa-I-G47S, vwa-I-T112A and vwa-I-G13S/R36Q/G47S segments (528 bp). Lanes 6-10: amplicons of vwa-II-G48S, vwa-II-G76S, vwa-II-V75D, vwa-II-Q126R and vwa-II-G76S/Q126R segments (603 bp).

(B). Expression of point-mutated vwa-I528 and vwa-II603 segments, detected by SDS-PAGE. Lane M: protein marker. Lane 1: wild-type E. coli BL21DE3. Lanes 2-6: the expressed rLep-vWA-I-G13S, rLep-vWA-I-R36Q, rLep-vWA-I-G47S, rLep-vWA-I-T112A and rLep-vWA-I-G13S/R36Q/G47S (~20.2 kDa). Lanes 7-11: the expressed rLep-vWA-II-G48S, rLep-vWA-II-G76S, rLep-vWA-II-V75D, rLep-vWA-II-Q126R and rLep-vWA-II-G76S/Q126R (~23.1 kDa).

(C). Extraction of point-mutated vwa-I528 and vwa-II603 segment products, detected by SDS-PAGE. The legend is the same as shown in B but for detection of the product extraction by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography.

(D). No LPS in the point-mutated rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II extracts, determined by spectrophotometric limulus test.

Fig. S5.

Decreased GPIbα-binding ability of the point-mutated rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II.

(A). Decreased Hu-platelet-binding ability of point-mutated rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II proteins, determined by SPR.

(B). Decreased Hu-platelet-binding ability of point-mutated rLep-vWA-I and rLep-vWA-II proteins, determined by ITC.

Fig. S6.

Blockage of hemorrhage by rLep-vWA-I-IgG and rLep-vWA-II-IgG in mice. The histopathological examination showed no visible hemorrhage in the IgG-blocked rLep-vWA-I- or rLep-vWA-II-injected mice.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to professor Stijn van der Veen, a native English speaker working at our university, to modify the English of our manuscript.

Funding sources

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81671974, 81471907, 81501713, 81760366 and 81802021), a grant from the National Key Lab for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases of China (J20111845/2013-032) and a grant from Program of High Level Creative Talents Cultivation in Guizhou Province (Qian-Ke-He 2016-4021).

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Contributors

J.Q.F, X.A.L. and J.Y. contributed to the design of this study. J.Q.F., M.I. and W.L.H. performed the experiments. J.Q.F., Y.L., Y.M.G. and K.X.L. analyzed the experimental data. J.Q.F., D.M.O. and J.Y. wrote and modify the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Potential conflicts of interest.

No reported conflicts.

Contributor Information

Muhammad Imran, Email: 11218010@zju.edu.cn.

David M. Ojcius, Email: dojcius@pacific.edu.

Yang Li, Email: 11418092@zju.edu.cn.

Xu'ai Lin, Email: lxai122@zju.edu.cn.

Jie Yan, Email: Med_bp@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bharti A.R., Nally J.E., Ricaldi J.N. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3(12):757–771. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ko A.I., Goarant C., Picardeau M. Leptospira: the dawn of the molecular genetics era for an emerging zoonotic pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(10):736–747. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang C.L., Wang H., Yan J. Leptospirosis prevalence in Chinese populations in the last two decades. Microbes Infect. 2012;14(4):317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith J.K., Young M.M., Wilson K.L., Craig S.B. Leptospirosis following a major flood in Central Queensland, Australia. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141(3):585–590. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812001021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miraglia F., Matsuo M., Morais Z.M. Molecular characterization, serotyping, and antibiotic susceptibility profile of Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni isolates from Brazil. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;77(3):195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forbes A.E., Zochowski W.J., Dubrey S.W., Sivaprakasam V. Leptospirosis and Weil's disease in the UK. Q J Med. 2012;105(12):1151–1162. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcs145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goris M.G., Boer K.R., Duarte T.A., Kliffen S.J., Hartskeerl R.A. Human leptospirosis trends, the Netherlands, 1925–2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(3):371–378. doi: 10.3201/eid1903.111260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Traxler R.M., Callinan L.S., Holman R.C., Steiner C., Guerra M.A. Leptospirosis-associated hospitalizations, United States, 1998–2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(8):1273–1279. doi: 10.3201/eid2008.130450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vries SG, Visser BJ, Nagel IM, Goris MG, Hartskeerl RA, Grobusch MP. Leptospirosis in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis 2014; 28(C):47–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Hartskeerl R.A., Collares-Pereira M., Ellis W.A. Emergence, control and re-emerging leptospirosis: dynamics of infection in the changing world. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(4):494–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adler B., Moctezuma A. Leptospira and leptospirosis. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140(3–4):287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McBride A.J., Athanazio D.A., Reis M.G., Ko A.I. Leptospirosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18(5):376–386. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000178824.05715.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haake D.A., Levett P.N. Leptospirosis in humans. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;387(387):65–97. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-45059-8_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu W.L., Lin X.A., Yan J. Leptospira and leptospirosis in China. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014;27(5):432–436. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palaniappan R.U., Ramanujam S., Chang Y.F. Leptospirosis: pathogenesis, immunity, and diagnosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20(3):284–292. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32814a5729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahlbäck B. Blood coagulation. Lancet. 2000;355(9215):1627–1632. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02225-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenting P.J., Christophe O.D., Denis C.V. von Willebrand factor biosynthesis, secretion, and clearance: connecting the far ends. Blood. 2015;125(13):2019–2028. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-528406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huizinga E.G., Tsuji S., Romijn R.A. Structures of glycoprotein ibalpha and its complex with von willebrand factor a1 domain. Science. 2002;297(5584):1176–1179. doi: 10.1126/science.107355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Z., Delaney M.K., O'Brien K.A., Du X. Signaling during platelet adhesion and activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(12):2341–2349. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kassegne K., Hu W.L., Ojcius D.M. Identification of collagenase as a critical virulence factor for invasiveness and transmission of pathogenic Leptospira species. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(7):1105–1115. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren S.X., Fu G., Jiang X.G. Unique physiological and pathogenic features of Leptospira interrogans revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 2003;422(6934):888–893. doi: 10.1038/nature01597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyata S., Goto S., Federici A.B., Ware J., Ruggeri Z.M. Conformational changes in the A1 domain of von Willebrand factor modulating the interaction with platelet glycoprotein Ib alpha. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(15):9046–9053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.9046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satoh K., Asazuma N., Yatomi Y. Activation of protein-tyrosine kinase pathways in human platelets stimulated with the A1 domain of von Willebrand factor. Platelets. 2000;11(3):171–176. doi: 10.1080/095371000403116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H., Wu Y.F., Ojcius D.M. Leptospiral hemolysins induce proinflammatory cytokines through Toll-like receptor 2- and 4-mediated JNK and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42266–e42280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng D., Li S.J., Ojcius D.M. A novel Fas-binding outer membrane protein and lipopolysaccharide of Leptospira interrogans induce macrophage apoptosis through Fas/FasL-caspase-8/−3 pathway. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018;7:135–151. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0135-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 26.Yue M., Luo D., Yu S. Misshapen/NIK-related Kinase (MINK1) is involved in platelet function, hemostasis and thrombus formation. Blood. 2016;127(7):927–937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-659185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin H., Stojanovic A., Hay N., Du X. The role of Akt in the signaling pathway of the glycoprotein Ib-IX induced platelet activation. Blood. 2008;111(2):658–665. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-085514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z., Zhang G., Feil R., Han J., Du X. Sequential activation of p38 and ERK pathways by cGMP-dependent protein kinase leading to activation of the platelet integrin alphaIIb beta3. Blood. 2006;107(3):965–972. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chu R., Reczek D., Brondyk W. Capture-stabilize approach for membrane protein SPR assays. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7360–7368. doi: 10.1038/srep07360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kantonen S.A., Henriksen N.M., Gilson M.K. Evaluation and minimization of uncertainty in ITC binding measurements: heat error, concentration error, saturation, and stoichiometry. Biochem Biophy Acta. 2017;1861(2):485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emsley J., Cruz M.A., Handin R., Liddington R. Crystal structure of the von Willebrand factor A1 domain and implications for the binding of platelet glycoprotein Ib. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(17):10396–10401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cruz M.A., Diacovo T.G., Emsley J., Liddington R., Handin R.I. Mapping the glycoprotein Ib-binding site in the von willebrand factor A1 domain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(25):19098–19105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu W.L., Ge Y.M., Ojcius D.M. p53 signalling controls cell cycle arrest and caspase-independent apoptosis in macrophages infected with pathogenic Leptospira species. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15(10):1642–1659. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang L., Zhang C.L., Ojcius D.M. The mammalian cell entry (Mce) protein of pathogenic species is responsible for RGD motif-dependent infection of cells and animals. Mol Microbiol. 2012;83(5):1006–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.07985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall N.C., Finlay B.B. Targeting the type III secretion system to treat bacterial infections. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 2014;18(2):137–152. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.855199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brophy D.F., Martin E.J., Gehr T.W. Best AM, Paul K, Carr ME. Thrombin generation time is a novel parameter for monitoring enoxaparin therapy in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;4(8 Pt 2):372–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Luca M., Facey D.A., Favaloro E.J. Structure and function of the von willebrand factor a1 domain: Analysis with monoclonal antibodies reveals distinct binding sites involved in recognition of the platelet membrane glycoprotein ib-ix-v complex and ristocetin-dependent activation. Blood. 2000;95(1):164–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Korotkov K.V., Sandkvist M., Hol G.J. The type II secretion system: biogenesis, molecular architecture and mechanism. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10(5):336–351. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Werts C., Tapping R.I., Mathison J.C. Leptospiral lipopolysaccharide activates cells through a TLR2-dependent mechanism. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(4):346–352. doi: 10.1038/86354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choy H.A., Kelley M.M., Chen T.L., Møller A.K., Matsunaga J., Haake D.A. Physiological osmotic induction of Leptospira interrogans adhesion: LigA and LigB bind extracellular matrix proteins and fibrinogen. Infect Immun. 2007;75(5):2441–2450. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01635-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fouts D.E., Matthias M.A., Adhikarla H. What makes a bacterial species pathogenic?: comparative genomic analysis of the genus Leptospira. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(2):e0004403–e0004409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eshghi A., Pappalardo E., Hester S. Pathogenic Leptospira interrogans exoproteins are primarily involved in heterotrophic processes. Infect Immun. 2015;83(8):3061–3073. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00427-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeng L., Zhang Y., Zhu Y. Extracellular proteome analysis of Leptospira interrogans serovar Lai. OMICS. 2013;17(10):527–535. doi: 10.1089/omi.2013.0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whyte C.A., Velmahos V. Escherichia coli meningitis following primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Eur J Intern Med. 2008;19(7):559–560. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lemichez E., Lecuit M., Nassif X., Bourdoulous S. Breaking the wall: targeting of the endothelium by pathogenic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8(2):93–104. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulman S., Rehnberg A.S., Hein M., Hegedus O., Lindmarker P., Hellstrom P.M. Helicobacter pylori causes gastrointestinal hemorrhage in patients with congenital bleeding disorders. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89(4):741–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dasenbrock H.H., Bartolozzi A.R., Gormley W.B., Frerichs K.U., Aziz-Sultan M.A., Du R. Clostridium difficile infection after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a nationwide analysis. Neurosurgery. 2016;78(3):412–420. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walker D.H., Valbuena G.A., Olano J.P. Pathogenic mechanisms of diseases caused by Rickettsia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;990(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raetz C.R., Whitfield C. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71(71):635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dellinger R.P. Inflammation and coagulation: implications for the septic patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(10):1259–1265. doi: 10.1086/374835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morganti R.P., Cardoso M.H., Pereira F.G. Mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effects of lipopolysaccharide on human platelet adhesion. Platelets. 2010;21:260–269. doi: 10.3109/09537101003637240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coller B.S., Shattil S.J. The gpiib/iiia (integrin alphaiibbeta3) odyssey: a technology-driven saga of a receptor with twists, turns, and even a bend. Blood. 2008;112(8):3011–3025. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-077891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Triplett D.A. Coagulation and bleeding disorders: review and update. Clin Chem. 2000;46(8 Pt 2):1260–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nally J.E., Chantranuwat C., Wu X.Y. Alveolar septal deposition of immunoglobulin and complement parallels pulmonary hemorrhage in a Guinea pig model of severe pulmonary leptospirosis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164(3):1115–1127. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63198-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bandeira M., Santos C.S., de Azevedo E.C. Attenuated nephritis in inducible nitric oxide synthase knockout C57BL/6 mice and pulmonary hemorrhage in CB17 SCID and recombination activating gene 1 knockout C57BL/6 mice infected with Leptospira interrogans. Infect Immun. 2011;79(7):2936–2940. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05099-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nally J.E., Fishbein M.C., Blanco D.R., Lovett M.A. Lethal infection of C3H/HeJ and C3H/SCID mice with an isolate of Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7014–7017. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.7014-7017.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ratet G., Santecchia I., D'Andon M.F. LipL21 lipoprotein binding to peptidoglycan enables Leptospira interrogans to escape NOD1 and NOD2 recognition. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(12):e1006725–e1006751. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lindhout T. Platelet activation and blood coagulation. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88(2):186–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bouchard B.A., Chapin J., Brummel-Ziedins K.E., Durda P., Key N.S., Tracy P.B. Platelets and platelet-derived factor Va confer hemostatic competence in complete factor V deficiency. Blood. 2015;125(23):3647–3650. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-589580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mendonça R., Silveira A.A., Conran N. Red cell DAMPs and inflammation. Inflamm Res. 2016;65(9):665–678. doi: 10.1007/s00011-016-0955-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Latz E., Xiao T.S., Stutz A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(6):397–411. doi: 10.1038/nri3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dutra F.F., Alves L.S., Rodrigues D. Hemolysis-induced lethality involves inflammasome activation by heme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(39):4110–4118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405023111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material