ABSTRACT

The study determined the prevalence of acute respiratory infections and diarrhoea among sub-Saharan African children. It also examined if there was any significant morbidity benefit conferred by three doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis containing vaccines (DTP3) with respect to maternal HIV status. Data were obtained from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) program, United Nations Development Programs, World Bank and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Pooled odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for the countries. Test of heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses and meta-regression were also conducted. The prevalence of acute respiratory infections and diarrhoea were similar between the children that were vaccinated and those who were not vaccinated with DTP3. The pooled result shows that children who did not receive DTP3 were more likely to have symptoms of acute respiratory infections than children who had DTP3 (OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.17); with low heterogeneity across the countries. The combined result for diarrhoea shows that children who did not receive DTP3 were less likely to have episodes of diarrhoea than children who received DTP3 (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.92); with substantial heterogeneity across the countries. There was no difference between the estimates of DTP3 vaccinated and unvaccinated children of HIV seropositive mothers with respect to symptoms of acute respiratory infections or episodes of diarrhoea. Tackling various causes and risk factors for respiratory tract infections and diarrhoeal diseases should be a priority for various stakeholders in sub-Saharan Africa.

Keywords: Acute respiratory infections, diarrhoea, HIV, sub-Saharan Africa, demographic and health surveys

Background

There were 5.9 million deaths in children under-five worldwide in 2015 with half of them caused by vaccine-preventable diseases.1,2 Medical conditions such as pneumonia and diarrhoea were leading cause of death among children under-five in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Acute respiratory infections (such as pneumonia) and diarrhoeal diseases put considerable burden on health services, including multiple hospital visits and admissions.3 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is a leading cause of disease burden and years of life lost in sub-Saharan Africa.4,5 The region is home to 75% of global burden of HIV.6–8 Globally, in 2016, it was estimated that 2.1 million children aged under 15 years were living with HIV with about 90% of these children residing in sub-Saharan Africa.7 HIV infection is a major contributor to under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa.7 It is also estimated that about 80% of people living with HIV will develop a respiratory infection at some time in the course of their disease.9,10 HIV-infected individuals also have an increased risk of diarrhoeal diseases.11,12

The Integrated Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Pneumonia and Diarrhoea (GAPPD) proposed vaccination as one of the key interventions against pneumonia and diarrhoea.13 Vaccine use in Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI) supported countries led to drop in child mortality rate from 76 to 63 deaths per 1,000 live births between 2010 and 2015.14,15 In spite of the progress made in terms of vaccination coverage in many African countries, there are still numerous unvaccinated and under-vaccinated children with the high possibility of the children, especially HIV-exposed children, dying from various vaccine-preventable diseases.16,17

Most studies on acute respiratory infections and diarrheal diseases among HIV-exposed children did not take immunisation status into account.16,17 There is also lack of information concerning morbidity differential and benefits of immunisation among children with respect to HIV status. There is evidence that children of HIV-infected mothers are more susceptible to acute respiratory infections and diarrhoeal diseases in comparison to the HIV non-exposed children.15,16 However, this finding is from few observational studies mainly conducted in Africa. There is need for a large study to resolve these competing conclusions, and the demographic and health survey (DHS) is a good source of data to meet this need. This research determined the prevalence of symptoms of acute respiratory infections and episodes of diarrhoea, and assessed if there was any significant morbidity benefit conferred by diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP3) vaccination among children in sub-Saharan Africa. This study also examined if maternal HIV status affects morbidity benefits of DTP3 uptake among sub-Saharan African children. Uptake of three doses of vaccines containing DTP3 by one year of age is considered to be a proxy for the immunisation status of children.18

Results

Description of included surveys

This study used nationally-representative DHS conducted in 27 different sub-Saharan African countries. These countries were included because their individual DHS has datasets on HIV status and vaccination.

The included surveys were conducted between 2003 and 2016. Table 1 shows the year of survey, use of antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, human development index (HDI), adult literacy rate, percentage of households using an improved water source, percentage of households with improved non-shared toilet facilities, and percentage of households in which there is daily smoking. The GDP per capita ranged from $285.7 in Burundi to $7,179.3 in Gabon. Adult literacy rate ranged from 15.5% in Niger to 88.7% in Zimbabwe. The HIV prevalence among women aged 15–49 years old ranged from 0.5% in Niger to 34.7% in Swaziland. The percentage of HIV positive women who were pregnant and received anti-retroviral drugs during pregnancy varied from 35% in Mali to 96% in Namibia. The percentage of households using an improved water source varied from 5.8% in Sao Tome and Principe to 45.9% in Angola while households with improved and non-shared toilet facilities varied from 6.6% in Chad to 54.1% in Rwanda.

Table 1.

Year of DHS survey and socio-economic characteristics of 27 study countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

| Country | Year of survey | GDP per capita | HDI | Adult literacy rate | Health expenditure | Antiretroviral drug coverage during PMTCT | HIV prevalence (adult female) | Households using an improved water source | Households with improved, non-shared toilet facilities | Households with smoking in the household daily |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | 2016 | 3110.8 | 0.533 | 66 | 179.4 | 44 | 2.2 | 45.9 | 32.2 | 13.1 |

| Burkina Faso | 2010 | 649.7 | 0.402 | 34.6 | 35.2 | 83 | 1.1 | 23 | 15.2 | n/a |

| Burundi | 2011 | 285.7 | 0.404 | 61.6 | 21.6 | 84 | 1.3 | 23.4 | 31.4 | 27.3 |

| Cameroon | 2011 | 1032.6 | 0.518 | 71.3 | 58.7 | 74 | 5.1 | 28.4 | 35.9 | n/a |

| Chad | 2015 | 664.3 | 0.396 | 22.3 | 37.1 | 63 | 1.6 | 44.5 | 6.6 | 12.8 |

| Congo DR | 2014 | 444.5 | 0.435 | 77 | 19.1 | 70 | 1 | 51 | 18.4 | 23 |

| Cote d’Ivoire | 2012 | 1526.2 | 0.474 | 43.9 | 88.4 | 73 | 3.5 | 20.9 | 18 | 21.8 |

| Ethiopia | 2003 | 706.8 | 0.448 | 39 | 26.6 | 69 | 1.3 | 38.4 | 6.8 | 7.1 |

| Gabon | 2012 | 7179.3 | 0.697 | 82.3 | 321.3 | 76 | 5.3 | 6.2 | 33.7 | 20.2 |

| Gambia | 2013 | 473.2 | 0.452 | 42 | 30.7 | 69 | 2 | 8.1 | 37 | 24 |

| Ghana | 2014 | 1513.5 | 0.579 | 71.5 | 57.9 | 56 | 2.1 | 10.2 | 13.6 | 9.3 |

| Guinea | 2012 | 508.1 | 0.414 | 32 | 37.3 | 43 | 1.9 | 25.1 | 19 | 22.8 |

| Kenya | 2009 | 1455.4 | 0.555 | 78.7 | 77.7 | 80 | 6.9 | 35.5 | 22.7 | n/a |

| Lesotho | 2014 | 998.1 | 0.497 | 76.6 | 105.1 | 66 | 29.8 | 16.4 | 47.1 | 16.3 |

| Liberia | 2013 | 455.4 | 0.427 | 42.9 | 46.3 | 70 | 2 | 27.3 | 14.2 | 12.7 |

| Malawi | 2016 | 300.8 | 0.476 | 62.1 | 29 | 84 | 11.2 | 12.7 | 51.8 | 12.1 |

| Mali | 2013 | 780.5 | 0.442 | 33.1 | 47.8 | 35 | 1.2 | 34 | 22 | 17.1 |

| Namibia | 2012 | 4140.5 | 0.64 | 88.3 | 499 | 96 | 16.6 | 10.4 | 33.5 | n/a |

| Niger | 2013 | 363.2 | 0.353 | 15.5 | 24.4 | 52 | 0.5 | 32.9 | 9.3 | n/a |

| Rwanda | 2015 | 702.8 | 0.498 | 68.3 | 52.5 | 82 | 3.8 | 27 | 54.1 | 14.6 |

| Sao T&P | 2009 | 1756.1 | 0.574 | 90.1 | 165.6 | n/a | n/a | 5.8 | 30.4 | n/a |

| Senegal | 2011 | 958.1 | 0.494 | 42.8 | 49.5 | 55 | 0.6 | 19.5 | 41.1 | 28.6 |

| Sierra Leone | 2013 | 496 | 0.42 | 32.4 | 85.9 | 87 | 2 | 39.1 | 9.6 | 37.6 |

| Swaziland | 2007 | 2775.2 | 0.541 | 83.1 | 247.9 | 95 | 34.7 | 29.9 | 9.3 | n/a |

| Togo | 2014 | 578.5 | 0.487 | 63.8 | 33.9 | 86 | 2.7 | 35.8 | 12.2 | 13.5 |

| Zambia | 2014 | 1178.4 | 0.579 | 83 | 85.9 | 83 | 14.5 | 34.5 | 25.4 | n/a |

| Zimbabwe | 2015 | 1008.6 | 0.516 | 88.7 | 57.7 | 93 | 16.1 | 21.8 | 37 | 10.8 |

GDP: gross domestic product, HDI: human development index, n/a: not available).

GDP – Low-income economies are defined as those with a GDP per capita of $1,025 or less; lower middle-income economies: $1,026 – $4,035; upper middle-income economies: $4,036 – $12,475;

high-income economies: ≥ $12,476. HDI – low: < 0.549; medium: 0.550 – 0.770.

(Source: Demographic and Health Surveys, World Bank, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, United Nations Development Programme.

Table 2 shows the number of children who developed symptoms of acute respiratory infections and episodes of diarrhoea by DTP3 status in each country. The prevalence of acute respiratory infections among children who did not receive DTP3 varied between 6% in Angola and 79% in Burundi; and among children who received DTP3, it varied from 8% in Angola to 79% in Burundi. The combined prevalence of symptoms of acute respiratory infections in the 27 countries was 37.2% (4,523/12,158) among children who did not receive DTP3, and 37.4% (8,153/21,801) among children who received DTP3. The prevalence of episodes of diarrhoea ranged from 5% in Rwanda to 26% in Liberia among children who did not receive DTP3, and from 9% in Mali to 29% in Malawi among children who received DTP3. The combined prevalence of diarrhoea was 16.0% (6,808/42,592) among children who did not receive DTP3 and 17.3% (12,845/74,188) among children who received DTP3.

Table 2.

No of cases and percentages of symptoms of acute respiratory infections and episodes of diarrhoea among the children with respect to DTP3 vaccination in 27 countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

| Symptoms of acute respiratory infections |

Episodes of diarrhea |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTP3 non-uptake |

DTP3 uptake |

DTP3 non-uptake |

DTP3 uptake |

|||||

| Country | No of cases | Percent (%) | No of cases | Percent (%) | No of cases | Percent (%) | No of cases | Percent (%) |

| Angola | 164 | 6 | 92 | 8 | 417 | 16 | 264 | 23 |

| Burkina Faso | 60 | 47 | 231 | 40 | 175 | 13 | 865 | 16 |

| Burundi | 133 | 79 | 908 | 79 | 85 | 20 | 812 | 26 |

| Cameroon | 267 | 56 | 470 | 45 | 329 | 20 | 559 | 18 |

| Chad | 381 | 58 | 154 | 57 | 759 | 19 | 274 | 19 |

| Congo DR | 566 | 42 | 513 | 37 | 765 | 18 | 685 | 16 |

| Cote d’Ivoire | 132 | 49 | 163 | 41 | 260 | 19 | 361 | 19 |

| Ethiopia | 786 | 60 | 417 | 59 | 1069 | 16 | 492 | 14 |

| Gabon | 344 | 42 | 206 | 40 | 431 | 19 | 202 | 16 |

| Gambia | 65 | 71 | 236 | 62 | 133 | 17 | 513 | 19 |

| Ghana | 32 | 49 | 149 | 47 | 40 | 6 | 293 | 14 |

| Guinea | 259 | 68 | 168 | 61 | 314 | 17 | 229 | 16 |

| Kenya | 88 | 49 | 258 | 50 | 123 | 18 | 323 | 17 |

| Lesotho | 16 | 27 | 117 | 36 | 25 | 9 | 137 | 12 |

| Liberia | 205 | 48 | 256 | 49 | 374 | 26 | 427 | 23 |

| Malawi | 60 | 11 | 354 | 14 | 80 | 15 | 762 | 29 |

| Mali | 57 | 45 | 92 | 41 | 153 | 7 | 249 | 9 |

| Namibia | 153 | 51 | 198 | 44 | 281 | 13 | 478 | 15 |

| Niger | 46 | 39 | 210 | 43 | 63 | 15 | 328 | 20 |

| Rwanda | 20 | 38 | 382 | 42 | 14 | 5 | 424 | 12 |

| Sao T&P | 30 | 57 | 175 | 53 | 40 | 13 | 184 | 13 |

| Senegal | 115 | 65 | 366 | 60 | 213 | 21 | 603 | 20 |

| Sierra Leone | 176 | 66 | 437 | 62 | 137 | 10 | 410 | 12 |

| Swaziland | 45 | 54 | 308 | 54 | 41 | 12 | 287 | 15 |

| Togo | 103 | 54 | 373 | 53 | 102 | 14 | 431 | 17 |

| Zambia | 151 | 33 | 680 | 30 | 272 | 12 | 1679 | 18 |

| Zimbabwe | 69 | 9 | 240 | 10 | 113 | 15 | 574 | 24 |

Table 3 shows the number of cases of acute respiratory infections and episodes of diarrhoea among children who received DTP3, grouped by the HIV status of their mothers. Among the children who received DTP3, the prevalence of symptoms of acute respiratory infections varied between 9% in Mali and 24% in Zimbabwe for children of HIV negative mothers; and between 4% in Ethiopia and 30% in Chad for children of HIV positive mothers. The combined prevalence of acute respiratory infections among children who received DTP3 was 38.0% (7,726/20,320) for children born of HIV negative mothers and 28.8% (427/ 1481) for children of women living with HIV. Regarding episodes of diarrhoea among children who received DTP3, the prevalence varied between 8% in Angola and 79% in Burundi in children of HIV negative mothers; and between 0% in Namibia and 73% in Sierra Leone among the children of HIV positive mothers. The combined prevalence of diarrhoea among children who received DTP3 was 17.4% (12,184/70,161) for children born of HIV negative mothers and 16.4% (661/4,027) for children of mothers living with HIV.

Table 3.

No of cases and percentages of symptoms of acute respiratory infections and episodes of diarrhoea among the children with uptake of DTP3 and maternal HIV status in 27 countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

| Symptoms of acute respiratory infections |

Episodes of diarrhea |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV seronegative |

HIV seropositive |

HIV seronegative |

HIV seropositive |

|||||

| Country | No of cases | Percent (%) | No of cases | Percent (%) | No of cases | Percent (%) | No of cases | Percent (%) |

| Angola | 258 | 23 | 6 | 29 | 91 | 8 | 1 | 5 |

| Burkina Faso | 857 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 228 | 40 | 3 | 50 |

| Burundi | 789 | 26 | 23 | 30 | 887 | 79 | 21 | 70 |

| Cameroon | 536 | 18 | 23 | 16 | 451 | 45 | 19 | 46 |

| Chad | 266 | 19 | 8 | 30 | 150 | 58 | 4 | 50 |

| Congo DR | 681 | 16 | 4 | 11 | 507 | 37 | 6 | 33 |

| Cote d’Ivoire | 355 | 19 | 6 | 10 | 160 | 42 | 3 | 30 |

| Ethiopia | 489 | 14 | 3 | 4 | 413 | 59 | 4 | 33 |

| Gabon | 198 | 16 | 4 | 8 | 198 | 40 | 8 | 36 |

| Gambia | 505 | 19 | 8 | 20 | 233 | 63 | 3 | 60 |

| Ghana | 290 | 14 | 3 | 7 | 144 | 47 | 5 | 50 |

| Guinea | 222 | 16 | 7 | 29 | 164 | 61 | 4 | 57 |

| Kenya | 291 | 17 | 32 | 22 | 237 | 50 | 21 | 51 |

| Lesotho | 105 | 13 | 32 | 11 | 92 | 36 | 25 | 36 |

| Liberia | 425 | 23 | 2 | 10 | 254 | 49 | 2 | 33 |

| Malawi | 712 | 30 | 50 | 25 | 330 | 14 | 24 | 12 |

| Mali | 246 | 9 | 3 | 11 | 90 | 41 | 2 | 40 |

| Namibia | 476 | 15 | 2 | 12 | 198 | 44 | 0 | 0 |

| Niger | 271 | 20 | 57 | 21 | 172 | 43 | 38 | 44 |

| Rwanda | 412 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 370 | 42 | 12 | 48 |

| Sao T&P | 183 | 13 | 1 | 8 | 175 | 53 | n/a | n/a |

| Senegal | 602 | 20 | 1 | 5 | 365 | 60 | 1 | 33 |

| Sierra Leone | 407 | 12 | 3 | 7 | 429 | 62 | 8 | 73 |

| Swaziland | 200 | 16 | 87 | 14 | 205 | 54 | 103 | 55 |

| Togo | 421 | 17 | 10 | 17 | 363 | 54 | 10 | 44 |

| Zambia | 1,485 | 18 | 194 | 17 | 608 | 30 | 72 | 27 |

| Zimbabwe | 502 | 24 | 72 | 20 | 212 | 10 | 28 | 8 |

Association between DTP3 status and acute respiratory infections or diarrhoea

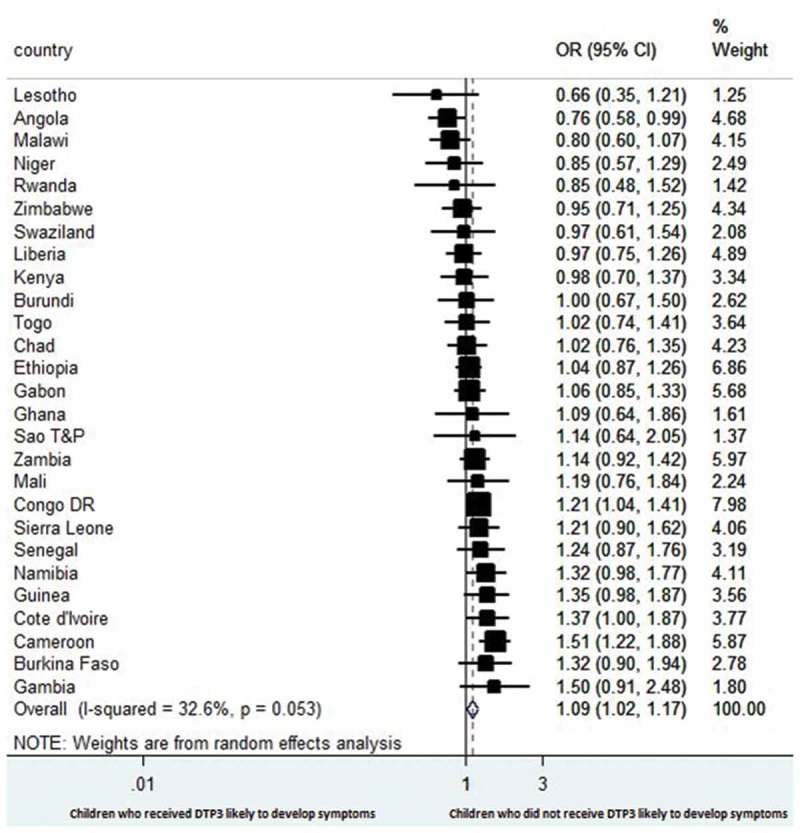

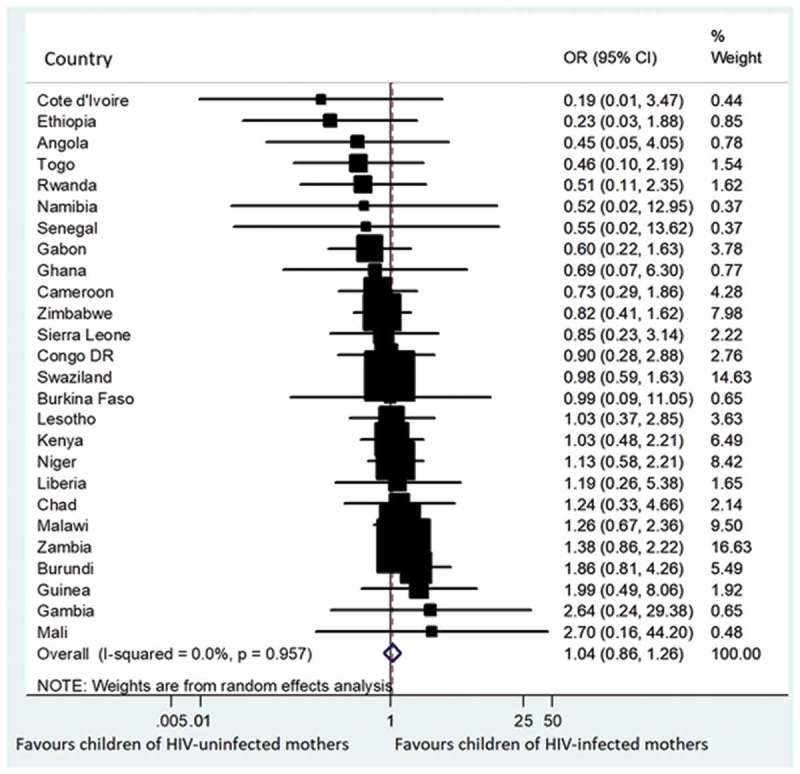

Figures 1 and 2 are forest plots of meta-analyses of the association between DTP3 status and acute respiratory infections or diarrhoea in each country at the time of the surveys. The combined result shows that children who did not receive DTP3 were more likely to have symptoms of acute respiratory infections than children who had DTP3: odds ratio (OR) 1.09, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.02 to 1.17). There was low heterogeneity in results across countries (I2 = 32.6%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Forest plot showing the prevalence of estimates of symptoms of acute respiratory infections among the children with respect to DTP3 vaccination in 27 sub-Saharan Africa countries.

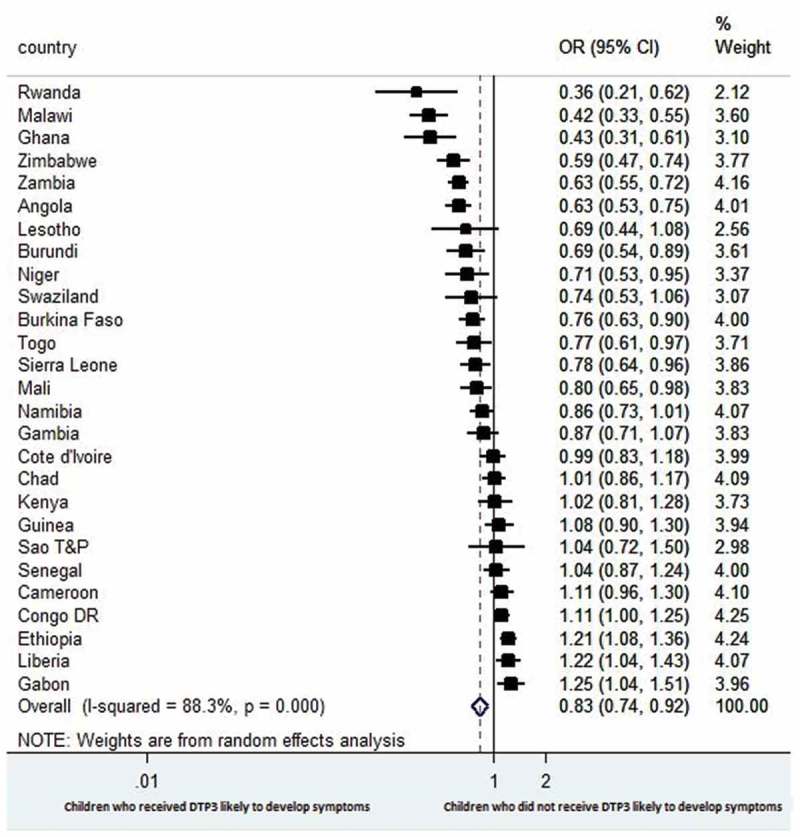

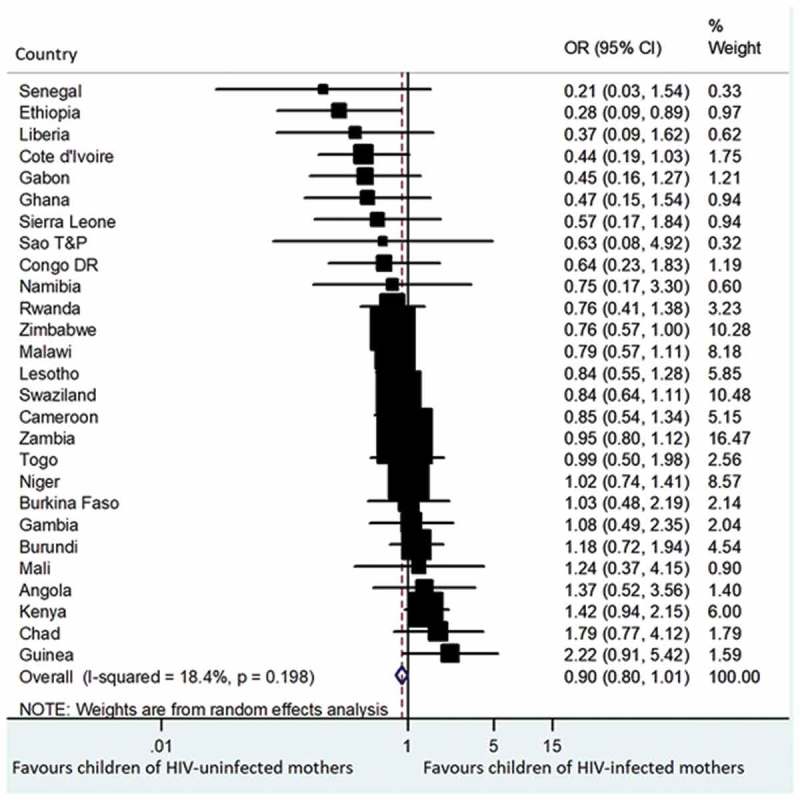

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the prevalence of estimates of episodes of diarrhoea among the children with respect to DTP3 vaccination in 27 sub-Saharan Africa countries.

The combined result for diarrhoea shows that children who did not receive DTP3 were less likely to have episodes of diarrhoea at the time of the survey than children who received DTP3 (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.92); with substantial heterogeneity in results across countries (I2 = 88.3%) (Figure 2).

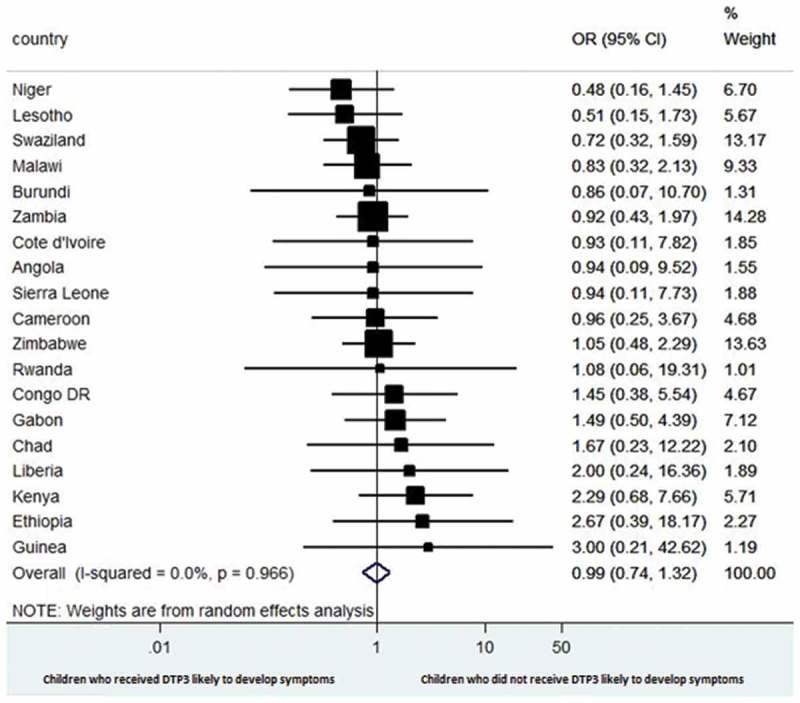

Figure 3 shows estimates of the association between receipt of DTP3 and presence of symptoms of acute respiratory infections among the children of HIV-infected mothers in each country at the time of the survey. The pooled result shows no significant difference in the odds of having symptoms of acute respiratory infections between children who did not receive and those who received DTP3 (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.32), with low heterogeneity across countries (I2 = 0.0%).

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing the prevalence of estimates of symptoms of acute respiratory infections among the children of HIV-infected mothers with respect to DTP3 vaccination in selected sub-Saharan Africa countries.

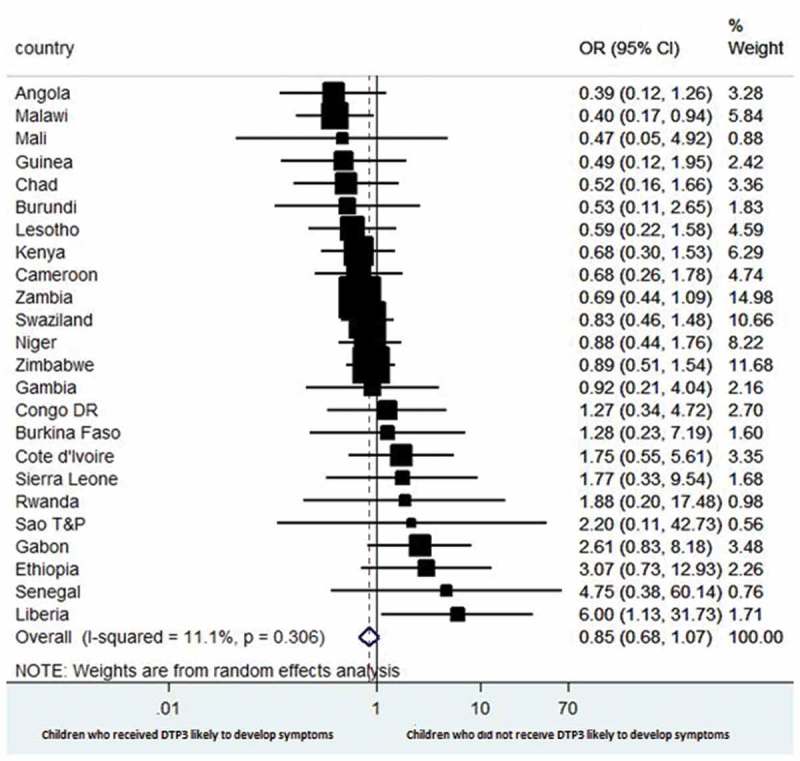

Figure 4 shows estimates of the association between receipt of DTP3 and episodes of diarrhoea among the children of HIV-infected mothers at the time of the survey in each country. The combined result shows no difference in the occurrence of episodes of diarrhoea between children who did not receive DTP3 and those who received DTP3 (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.07), with low heterogeneity across countries (I2 = 11.1%).

Figure 4.

Forest plot showing the prevalence of estimates of episodes of diarrhoea among the children of HIV-infected mothers with respect to DTP3 vaccination in selected sub-Saharan Africa countries.

When we combined the data for the prevalence of symptoms of acute respiratory infections across the study countries, there was no significant difference between the children of HIV negative mothers who were vaccinated with DTP3 and those of mothers living with HIV (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.26); with low heterogeneity across countries (I2 = 0.0%) (Figure 5). Similarly, there was no difference in the combined prevalence of episodes of diarrhoea between the children of HIV negative mothers who were vaccinated with DTP3 and those of mothers living with HIV (OR 0.90; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.01); with low heterogeneity in results among countries (I2 = 18.4%) (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Forest plot showing theprevalence of estimates of symptoms of acute respiratory infections among the children who were vaccinated with DTP3 with respect to the maternal HIV status in 27 sub-Saharan Africa countries.

Figure 6.

Forest plot showing the prevalence of estimates of episodes of diarrhoea among the children who were vaccinated with DTP3 with respect to the maternal HIV status in 26 sub-Saharan Africa countries.

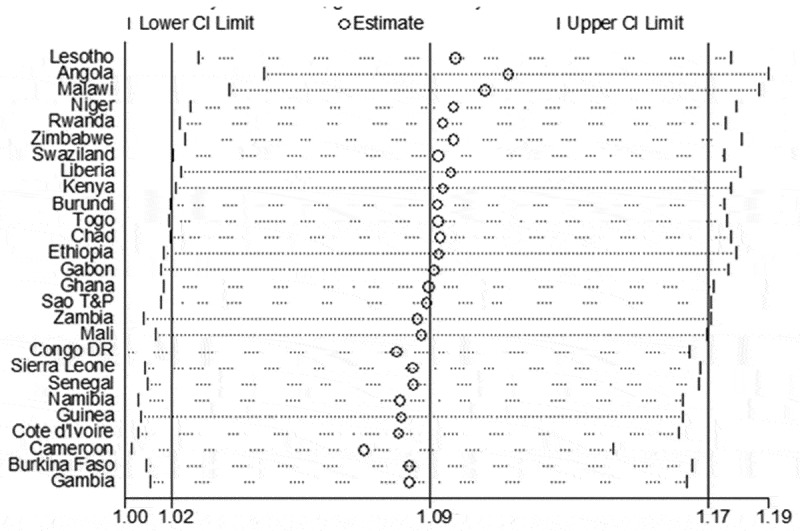

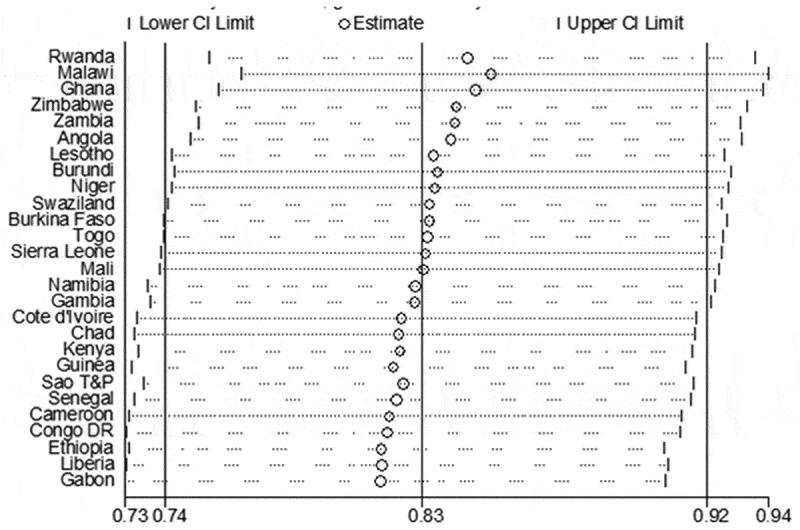

Leave-one-country out sensitivity analyses show that no country had an undue influence on the pooled estimate of episodes of acute respiratory infections and diarrhoea (Figures 7 and 8). The variations in the CIs with the exclusion of each country remains within the 95% confidence interval for the overall estimates. The stability of the overall results for both episodes of acute respiratory infections and diarrhoea was justified by the outcome of the sensitivity analyses.

Figure 7.

A plot showing the influence of each country on the overall pooled result for estimates of acute respiratory infections using “leave-one-country-out” sensitivity analysis.

Figure 8.

A plot showing the influence of each country on the overall pooled result for estimates of diarrhoea using “leave-one-country-out” sensitivity analysis.

Sub-group analyses

In order to assess the effect of various country-level characteristics on the pooled estimates, subgroup analyses were conducted using DerSimonian-Laird method. Results from the subgroup analyses show that the differences between countries in HDI, GDP, adult literacy rate, years of survey, sub-regions (West Africa, Central/East Africa, Southern Africa), households using an improved water source, and households with improved non-shared toilet facilities did not explain the heterogeneity of estimates of episodes of diarrhoea among the children (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis and univariate meta-regression analysis results (for diarrhoea).

| Univariate meta-regression |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | No of studies | Subgroup odds ratio | 95% CI | I-squared | P-value* | #β (p-value)* | 95% CI |

| Year of survey | 0.95 (0.009) | 0.91,0.99 | |||||

| 2003–2007 | 2 | 0.98 | 0.61, 1.57 | 85.2 | 0.000 | ||

| 2008–2012 | 10 | 0.97 | 0.87, 1.09 | 70.0 | 0.000 | ||

| 2013–2016 | 15 | 0.72 | 0.61, 0.85 | 90.1 | 0.000 | ||

| Gross domestic product per capita (US$) | 0.98 (0.862) | 0.75, 1.28 | |||||

| Low | 18 | 0.84 | 0.73, 0.95 | 87.8 | 0.000 | ||

| Middle | 9 | 0.83 | 0.67, 0.99 | 88.1 | 0.000 | ||

| Human development index | 1.01 (0.950) | 0.74, 1.37 | |||||

| Low | 21 | 0.83 | 0.73, 0.93 | 87.6 | 0.000 | ||

| Medium | 6 | 0.83 | 0.62, 1.09 | 90.7 | 0.000 | ||

| Adult literacy rate | 1.00 (0.273) | 0.99, 1.00 | |||||

| Low | 11 | 0.95 | 0.85, 1.06 | 77.4 | 0.000 | ||

| Average | 9 | 0.70 | 0.54, 0.90 | 86.8 | 0.000 | ||

| High | 7 | 0.80 | 0.64, 1.02 | 92.4 | 0.000 | ||

| Households using an improved water source | 1.12 (0.356) | 0.87, 1.44 | |||||

| Low | 12 | 0.77 | 0.65, 0.92 | 87.1 | 0.000 | ||

| Medium | 15 | 0.87 | 0.76, 1.00 | 88.8 | 0.000 | ||

| Households with improved, non-shared toilet facilities | 0.85 (0.195) | 0.67, 1.09 | |||||

| Low | 14 | 0.90 | 0.80, 1.02 | 82.9 | 0.000 | ||

| Medium | 13 | 0.76 | 0.63, 0.91 | 89.5 | 0.000 | ||

| Regions | 0.88 (0.073) | 0.76, 1.01 | |||||

| Western Africa | 13 | 0.88 | 0.78, 0.99 | 76.9 | 0.000 | ||

| Central/Eastern Africa | 7 | 1.00 | 0.85, 1.17 | 82.5 | 0.000 | ||

| Southern Africa | 7 | 0.64 | 0.54, 0.75 | 75.5 | 0.000 | ||

* p < 0.05 #β- Beta coefficient.

Meta-regression analysis

Meta-regression analyses were conducted to investigate which country-level characteristics might account for the heterogeneity in the association between receipt of DTP3 and prevalence of diarrhoea (Figure 2). Table 4 shows that year of survey was a significant predictor of the association between DTP3 uptake and diarrhoea. HDI, GDP, adult literacy rate, sub-regions, households using an improved water source, and households with improved non-shared toilet facilities were not significantly associated with the episodes of diarrhoea in children vaccinated with DTP3 (Table 4).

Discussion

This research illustrates that DTP vaccination had some benefit in terms of reduced odds of developing acute respiratory infections but not for diarrheal episodes among children in sub-Saharan Africa. We found no significant difference in the estimates of having symptoms of acute respiratory infections and episodes of diarrhoea among the DTP3 vaccinated children of HIV-infected mothers and HIV-uninfected mothers. Morbidity benefit in terms of acute respiratory infections and diarrhoea varied across sub-Saharan African countries. The prevalence of acute respiratory infections was higher among the vaccinated children of HIV seronegative mothers than the children of HIV seropositive mothers. The children of HIV uninfected women also had more episodes of diarrhoea than the vaccinated children of women living with HIV.

This research contrasts the findings of a Malawian study among HIV-infected, HIV-exposed uninfected and HIV-unexposed children which showed morbidity benefit for both diarrhoea and respiratory infection among the children of HIV uninfected mothers.17 A cohort study of Congolese birth cohort of 429 infants born to HIV positive and HIV negative mothers shows that two-third of the infant had at least one episode of acute diarrhoea within the study period of 16 months.19 The study showed that HIV-infected children had diarrhoea incidence of 170 episodes per 100 child-years while the uninfected infants had 100 per 100 child-years.19 However, both HIV-exposed uninfected children and the infants of HIV seronegative mothers had similar overall diarrhoeal incidence rates.19 Findings from a South African study among breastfed infants revealed that there were more cases of severe infectious morbidity among HIV-exposed infants than the HIV-uninfected infants who were breastfed.20 However, there was no significant difference between the HIV-exposed and HIV-uninfected infants with respect to infectious causes leading to hospitalisation or mortality at six months of life.20 It should be noted that unlike the respondents of this particular study who were all vaccinated with DTP3, the participants of the Congolese and South African studies had varying coverage of vaccination.19,20

Meta-regression analyses were conducted to assess the relationship between various covariates and the dependent variables. The meta-regression analytic findings for episodes of diarrhoea were not significant for the country-level characteristics except for the year of survey. The included surveys were conducted over a decade and the long span of time between the surveys could explain the significant heterogeneity finding of the meta-analysis for the estimates of episodes of diarrhoea among sub-Sahara African children. The meta-regression findings show that the year of survey is an important predictor of episodes of diarrhoea as it relates to uptake of DTP3. There has been progressive changes in terms of healthcare coverage, introduction of newer vaccines etc. in different countries over the years and this could well explain the widely varying changes in episodes of diarrhoea over the years.

Vaccination against vaccine-preventable diseases is not the only factor linked to the occurrence of diarrhoea and respiratory infections. Improved water supply is one of the factors linked to reduction in episodes of diarrhoea. 21 It has been proven that households with improved water supply could reduce incidence of diarrhoea among under-five children in sub-Saharan Africa.21 The use of pipe-borne water supply within a private household or yard is a major source of improved water supply. Other improved drinking water sources are public water taps, protected deep well, boreholes, collected rainwater and protected springs.22. Diarrhoeal diseases could be reduced by 11% if the users of unimproved water sources switched to other sources of improved water sources and by 23% if switched to private household piped water.23 The use of water treatment such as boiling, filtration and proper storage could reduce diarrhoea by 45%.23 Consistent handwashing with soap could reduce the risk of diarrhoeal disease by at least 48%.24 Moderate-severe diarrhoea is also reduced by the use of private household toilet in comparison to sharing with other households .25

Smoking is a major risk factor for respiratory tract infections secondary to bacterial and fungal agents. There is an increased risk of respiratory tract infections due to both active and passive smoke exposures. There are strong links between smoking and serious respiratory infections such as invasive pneumococcal disease, influenza and tuberculosis.26 Indoor air pollution particularly from the use of household biomass fuels are linked to respiratory tract infections and are contributory factor to these infections in children.27

Policy implication

Implementation of GAPPD is essential in ending preventable childhood deaths due to pneumonia and diarrhoea by 2025.13 Tackling various causes and risk factors for respiratory tract infections and diarrhoeal diseases should be a priority for various stakeholders in sub-Saharan Africa. There is need for introduction and scaling up the use of newer vaccines such as Haemophilus influenzae type B, pneumococcus, and rotavirus vaccines especially in African countries that are yet to include them in their national immunisation programme. Rotavirus is the most common cause of severe and fatal diarrhoea in children while Streptococcus pneumonia and Haemophilus influenzae cause pneumonia, meningitis, otitis media, sinusitis etc. in children.28,29 The inclusion of these newer vaccines will further reduce the incidence of diarrhoea and pneumonia. African government officials, policy makers, developmental agencies and healthcare workers should ensure the availability and easy access to routine licensed vaccines. The health systems in some of the African countries are very weak and needed to be strengthened with efforts channelled towards improving the low vaccination coverage.14,30 In addition to ensuring an optimal immunisation programming, there is also need to promote other strategies such as vitamin A supplementation, use of zinc supplements, the prevention of low birth weight, breastfeeding, personal hygiene and weaning education.31

Investing in various methods of effective household water treatment in combination with proper safe water storage can lead to substantial reduction in cases of diarrhoeal diseases. The provision and use of improved toilet facilities in household can also lead to further reduction in diarrhoea among African children. Prevalence of handwashing is very low in most of the low and middle income countries which are also the countries with high level of pneumonia and diarrhoea. There is also need to reduce household air pollution with the provision and use of improved stoves which has been shown to reduce severe pneumonia.13

Strengths and limitations

This study used DHS data which are countrywide survey and therefore has advantages over primary studies which are limited to just one or few communities. The meta-analyses permitted the synthesis of different findings across countries and gave room for assessment across various surveys.32 DHS provides a good source for large maternal HIV and child immunisation datasets and ability to merge mother and child data.

The use of rotavirus and pneumococcal vaccination data would have provided some additional information with respect to incidence of diarrhoea and pneumonia, however, majority of the DHS did not include these newer vaccines as at the time of the survey because most countries had not adopted the vaccines as part of the national immunisation programme. The use of DTP3 is expected to reflect the national vaccination coverage since it is the benchmark for the national programme. However, one of the reasons for lack of significant association of DTP3 with reduced acute respiratory infections and diarrhoea could be that the immunisation programmes has expanded, and DTP3 may not be an accurate indicator for protection against vaccine-preventable diseases e.g. diarrhoea, respiratory infections, measles, etc. thus the need for more indicators for childhood immunisation.

This study being an ecological study with cross-sectional design and with the likeness of ecological fallacy, care must be taken in crediting detected causal relationship directly to this study. This study was limited by non-availability of data on children HIV status from DHS datasets and had to use maternal HIV as a reference for the children HIV status. The surveys were conducted over a decade and this may likely have some influence on the study findings. Three of the meta-analyses did not include all the 27 study countries due to non-availability of datasets on episodes of diarrhoea and symptoms of acute respiratory infections especially in children of women living with HIV.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the prevalence of acute respiratory infections and diarrhoea were similar between the children that were vaccinated and those who were not vaccinated with DTP3. Both the symptoms of acute respiratory infections and episodes of diarrhoea among DTP3 vaccinated and unvaccinated children shows significant difference in the overall estimates between the two groups of children. The data for symptoms of acute respiratory infections were pooled together with no statistical difference in the overall estimates between the children of HIV-infected mothers that were vaccinated with DTP3 and the ones that were not vaccinated. The data for episodes of diarrhoea were pooled together with resultant nil significant difference in the overall estimates between the children of HIV-infected mothers that were vaccinated with DTP3 and the ones that were not vaccinated. There was no significant difference in the overall estimates between the children of HIV negative mothers who were vaccinated with DTP3 and those of mothers living with HIV with respect to the prevalence of symptoms of acute respiratory infections and episodes of diarrhoea across the study countries. Many African countries recorded high rates of respiratory infections and diarrhoeal diseases. Extra efforts should be targeted at tackling various causes and risk factors for respiratory tract infections and diarrhoeal diseases especially among HIV-exposed children in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

Data sources

Data sets were obtained from the DHS program,33 United Nations Development Programs,34 World Bank 35 and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.4 The study countries were selected based on the availability of DHS data on childhood immunisation coverage; HIV testing; recent symptoms of acute respiratory infection and episodes of acute diarrhoea two weeks prior to the conduct of the surveys. The included countries were as follows: Angola, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroun, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Malawi, Mali, Namibia, Niger, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Swaziland, Togo, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Variables

Main outcomes

The main outcomes for this study were recent symptoms of acute respiratory infections or episodes of diarrhoea in DTP3 vaccinated children aged 12–23 months.

Country level factors

The following country-level characteristics were included in this study: GDP per capita, adult literacy rate, HDI, health expenditure, coverage of pregnant women who received antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy, households using an improved water source, households with improved, non-shared toilet facilities and households with daily smoking in the household.34,36 The country-level variables were divided into low and high categories for better interpretation in relation to the policy formulation.

Data analysis

The distribution of respondents were expressed as percentages. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used for analysing the contingency tables and multiple logistic regressions to examine variations across socioeconomic factors. DerSimonian-Laird method 37 was used for random-effects model and for the calculation of the pooled prevalence estimates. Higgin’s I2 statistics was used to describe the percentage of variation across studies.38,39 Leave-one-country out sensitivity analysis was used to assess the stability of the meta-analysis.40 The level of statistical significance for the analyses was p < 0.05 with two-tailed comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata 14.0.41

Funding Statement

Olatunji O. Adetokunboh and Charles S. Wiysonge are supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant numbers: 106035 and 108571) and the South African Medical Research Council. Olalekan A. Uthman is supported by the National Institute of Health Research using Official Development Assistance funding. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, National Institute for Health Research; National Research Foundation of South Africa; National Institute of Health Research; South African Medical Research Council; South African Medical Research Council.

Ethical consideration

This study was conducted as a secondary data analysis. Ethical approval was given for the primary data by the Ethics Committee of the ICF International, Calverton, USA and National Ethics Committee of the included countries. The study participants gave consent before participation. The participant’s confidentiality was also protected and all the identifiers information were removed.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- ARV:

antiretroviral drugs

- CI:

Confidence intervals

- DHS:

Demographic and health survey

- DTP:

Diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis

- GAPPD:

Integrated Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Pneumonia and Diarrhoea

- GAVI:

Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation

- GDP:

Gross domestic product per capita

- HDI:

Human development index

- HIV:

Human immunodeficiency virus

- OR:

Odds ratio

- PMTCT:

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the MEASURE DHS for releasing the data for this study.

Authors’ contribution

OOA and OAU conceived the study. OOA did the data analysis, interpreted the results and wrote the initial manuscript. OAU and CSW reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.United Nations Children’s Fund. The state of the world children 2016. A fair chance for every child. 2016. New York (United States): UNICEF; 2017. accessed 2018 January 15 http://www.un-ilibrary.org/children-and-youth/the-state-of-the-world-s-children-2016_4fb40cfa-en

- 2.Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, Casey DC, Charlson FJ, Chen AZ, Coates MM, et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980???2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet. 2016;388:1459–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zwi K, Pettifor J, Soderlund N, Meyers T.. HIV infection and in-hospital mortality at an academic hospital in South Africa. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83(3):227–230. PMID: 10952640. doi: 10.1136/adc.83.3.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ortblad KF, Lozano R, Murray CJL.. The burden of HIV : insights from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. AIDS. 2013;27(13):2003–2017. PMID: 23660576. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328362ba67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abajobir AA, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Aboyans V, Adetokunboh O, Afshin A, Agrawal A, Ahmadi A, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151–1210. PMID: 28919116. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS How AIDS changed everything—MDG6: 15 years, 15 lessons of hope from the AIDS response. Geneva (Switzerland): UNAIDS; 2015. accessed 2017 December 16 http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/MDG6Report_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS AIDSInfo. 2017. [url http://aidsinfo.unaids.org/] (accessed 2017 December 16

- 8.Wang H, Wolock TM, Carter A, Nguyen G, Kyu HH, Gakidou E, Hay SI, Mills EJ, Trickey A, Msemburi W, et al. Estimates of global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and mortality of HIV, 1980???2015: the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet HIV. 2016;3:e361–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pérez MS, Van Dyke RB. Pulmonary infections in children with HIV infection. Semin Respir Infect. 2002;17(1):33–46. PMID:11891517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham SM, Coulter JB, Gilks CF. Pulmonary disease in HIV-infected African children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5(1):12–23. PMID: 11263511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madhi SA, Petersen K, Madhi A, Khoosal M, Klugman KP. Increased disease burden and antibiotic resistance of bacteria causing severe community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 – infected children. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilcox CM. Etiology and evaluation of diarrhea in AIDS: A global perspective at the millennium. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6(2):177–186. PMID: 11819553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization The United Nations Children’s Fund. Ending preventable child deaths from pneumonia and diarrhoea by 2025: the integrated Global Action Plan for Pneumonia and Diarrhoea (GAPPD). Geneva (Switzerland): WHO/UNICEF; 2013. accessed 2018 January 20 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/79200/1/9789241505239_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation GAVI Annual Report. 2016. 2017; http://www.gavi.org/progress-report/ (accessed 2017 December 27)

- 15.Szucs TD. Cost-Effectiveness of Vaccinations In: Kaufmann SHE, editor. Novel Vaccination Strategies. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, Germany; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brahmbhatt H, Kigozi G, Wabwire-Mangen F, Serwadda D, Lutalo T, Nalugoda F, Sewankambo N, Kiduggavu M, Wawer M, Gray R. Mortality in HIV-lnfected and Uninfected Children of HIV-lnfected and Uninfected Mothers in Rural Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(4):504–508. PMID: 16652060. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000188122.15493.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taha TE, Kumwenda NI, Broadhead RL, Hoover DR, Graham SM, Van Der Hoven L, Markakis D, Liomba GN, Chiphangwi JD, Miotti PG. Mortality after the first year of life among human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected and uninfected children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18(8):689–694. PMID: 10462337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machingaidze S, Wiysonge CS, Hussey GD. Strengthening the Expanded Programme on Immunization in Africa: looking beyond 2015. PLoS Med. 2013;10:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thea DM, St. Louis ME, Atido U, Kanjinga K, Kembo B, Matondo M, Tshiamala T, Kamenga C, Davachi F, Brown C, et al. A prospective study of diarrhea and HIV-1 infection among 429 Zairian infants. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(23):1696–1702. PMID: 8232458. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312023292304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slogrove AL, Esser MM, Cotton MF, Speert DP, Kollmann TR, Singer J, Bettinger JA. A Prospective cohort study of common childhood infections in South African HIV-exposed uninfected and HIV-unexposed infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(2):e38–e44. PMID: 28081048. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cha S, Kang D, Tuffuor B, Lee G, Cho J. The effect of improved water supply on diarrhea prevalence of children under five in the volta region of ghana : a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(10):12127–12143. PMID: 26404337. doi: 10.3390/ijerph121012127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization Preventing diarrhoea through better water, sanitation and hygiene: exposures and impacts in low- and middle-income countries. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2014. accessed 2017 December 27 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/150112/9789241564823_eng.pdf;jsessionid=EA9D0F97FDA20F509605478A16C9FEB3?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf J, Prüss-Ustün A, Cumming O, Bartram J, Bonjour S, Cairncross S, Clasen T, Colford JM, Curtis V, De France J, et al. Assessing the impact of drinking water and sanitation on diarrhoeal disease in low- and middle-income settings: systematic review and meta-regression. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(8):928–942. PMID: 24811732. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cairncross S, Hunt C, Boisson S, Bostoen K, Curtis V, Fung ICH, Schmidt WP. Water, sanitation and hygiene for the prevention of diarrhoea. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;Suppl 1:i193–205. PMID: 20348121. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker KK, O’Reilly CE, Levine MM, Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Ayers TL, Farag TH, Nasrin D, Blackwelder WC, Wu Y, et al. Sanitation and hygiene-specific risk factors for moderate-to-severe diarrhea in young children in the global enteric multicenter study, 2007–2011:case-controlstudy. PLoS Med. 2016;13(5):e1002010 PMID: 27138888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arcavi L, Benowitz NL. Cigarette Smoking and Infection. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(20):2206–2216. PMID: 15534156. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.20.2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith KR, Samet JM, Romieu I, Bruce N. Indoor air pollution in developing countries and acute lower respiratory infections in children. Thorax. 2000;55(6):518–532. PMID: 10817802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer Walker CL, Rudan I, Liu L, Nair H, Theodoratou E, Bhutta ZA, O’Brien KL, Campbell H, Black RE. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. The Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1405–1416. PMID: 23582727. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu J, Sun X, Huang Z, Wagner AL, Carlson B, Yang J, Tang S, Li Y, Boulton ML, Yuan Z. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b carriage in Chinese children aged 12-18 months in Shanghai, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:149 PMID: 27080523. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1485-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keugoung B, Ymele FF, Fotsing R, Macq J, Meli J, Criel B. A systematic review of missed opportunities for improving tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS control in sub-Saharan Africa: what is still missed by health experts? Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18:320 PMID: 25478041. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.320.4066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huttly SR, Morris SS, Pisani V. Prevention of diarrhoea in young children in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 1997;75(2):163–174. PMID: 9185369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arriola KR, Louden T, Doldren MA, Fortenberry RM. A meta-analysis of the relationship of child sexual abuse to HIV risk behavior among women. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29(6):725–746. PMID:15979712. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Measure DHS Publications by country. [url http://dhsprogram.com/Publications/Publications-by-Country.cfm] 2017. (accessed 2017 December 21

- 34.United Nations Development Programme The Human Development Index (HDI). [url http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/indices/hdi/] 2017. (accessed 2017 December 20

- 35.World Bank The World Bank Data. [url http://data.worldbank.org/] 2017. (accessed 2017 December 22

- 36.United Nations Development Programme Technical note 1: calculating the human development indices. [url http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2015_technical_notes.pdf]2015 (accessed December 22, 2017)

- 37.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-Analysis in Clinical Trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. PMID: 3802833. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. PMID:12111919. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. PMID: 12958120. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Normand S. Meta-analysis: formulating, evaluating, combining, and reporting. Statist. Med. 1999;18:321–359. PMID: 10070677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.StataCorp Stata Statistical Software: release 14. College Station (TX): StataCorp LP; 2015doi: 10.1086/313925PMID: 10913417 [Google Scholar]