ABSTRACT

Secreted Wnt ligands play a major role in the development and progression of many cancers by modulating signaling through cell-surface Frizzled receptors (FZDs). In order to achieve maximal effect on Wnt signaling by targeting the cell surface, we developed a synthetic antibody targeting six of the 10 human FZDs. We first identified an anti-FZD antagonist antibody (F2) with a specificity profile matching that of OMP-18R5, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits growth of many cancers by targeting FZD7, FZD1, FZD2, FZD5 and FZD8. We then used combinatorial antibody engineering by phage display to develop a variant antibody F2.A with specificity broadened to include FZD4. We confirmed that F2.A blocked binding of Wnt ligands, but not binding of Norrin, a ligand that also activates FZD4. Importantly, F2.A proved to be much more efficacious than either OMP-18R5 or F2 in inhibiting the growth of multiple RNF43-mutant pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell lines, including patient-derived cells.

Keywords: Wnt signaling, phage display, anti-Frizzled synthetic antibodies, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Introduction

The Wnt family of secreted glycoproteins plays important roles in embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis of multicellular animals. In humans, 19 Wnt proteins initiate signal transduction through 10 cell-surface Frizzled receptors (FZDs).1,2 The signaling output of the pathway is also regulated through engagement of various Wnt co-receptors, including LRP5, LRP6, RYK, ROR1 and ROR2,3 which are thought to enable the specific and context-dependent engagement of different intracellular signaling pathways. The Wnt-β-catenin pathway revolves around the post-translational control of β-catenin levels. Wnt engaging a FZD receptor and an LRP5 or LRP6 co-receptor leads to inhibition of the destruction complex, a group of proteins that includes the scaffolding proteins APC and Axin, as well as the kinases GSK3α/β and CK1α, and that is responsible for promoting the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of β-catenin. Upon pathway activation, accumulation of β-catenin leads to its translocation to the nucleus, where it interacts with the LEF/TCF family transcription factors to regulate context-specific transcriptional programs that govern modulation of cell proliferation, cell differentiation or stem cell self-renewal.3-7

Hyperactivation of Wnt-β-catenin signaling has been linked to the initiation and progression of many cancers, including colorectal, ovarian, gastric and endometrial cancers, as well as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC).8,9 Hyperactivation of this pathway most commonly occurs as a result of mutations within intracellular negative regulators such as APC,8,9 and AXIN2.10,11However, recent studies have identified mutations within RNF4312 and ZNFR3,13 which are also tumor suppressors but function to negatively regulate cell surface expression of FZD receptors.14,15 Similarly, gene fusions with R-spondins, ligands that amplify Wnt signaling, have been identified recently in cancers that are thought to depend on Wnt ligands for growth.16 These new findings have rejuvenated efforts to target the Wnt pathway at the receptor complex level and have revealed opportunities to focus on different components of the pathway.8,9,17

A potential approach to target cancers that depend on Wnt-β-catenin signaling is through anti-FZD antibodies (Abs) that antagonize signaling, either directly by blocking the interaction with Wnt ligands or indirectly through allosteric effects.18 An anti-FZD antagonistic Ab, known as OMP-18R5 or vantictumab, entered clinical trials after showing efficacy and safety in the treatment of multiple cancer types in mouse xenograft models.18 OMP-18R5 was derived from a phage-displayed Ab library screened against the Wnt-binding ectodomain of FZD7, but it also binds to FZD1, FZD2, FZD5 and FZD8. OMP-18R5 has been evaluated in clinical trials as a single-agent therapeutic for the treatment of solid tumors, as well as in combination with standard-of-care therapeutics for metastatic breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer and pancreatic cancer. Clinical data in patients with solid tumors demonstrated efficacy and safety for OMP-18R5, with manageable side effects on bone turnover.19 These results indicate that targeting multiple FZDs is a promising therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment.

OMP-18R5 only targets five of the 10 FZD receptors encoded by the human genome, and this could be limiting depending on tumor context. For example, FZD4 is not inhibited by OMP-18R5, and its aberrant over-expression is associated with aggressive traits in multiple cancers, including acute and chronic myeloid leukemia,20,21 glioblastoma,22 breast,23 prostate,24 and pancreatic cancers.25 Moreover, in endothelial cells the transcription factor ERG promotes junctional integrity by inducing expression of VE-Cadherin and Wnt-β-catenin signaling through regulation of FZD4 expression, suggesting a role for FZD4 in angiogenesis and vascular stability.26 Similarly, FZD4 is known to regulate retinal vascular development27,28 when it is activated by Norrin, a cystine-knot like growth factor that selectively binds to FZD4 despite its lack of homology with Wnt proteins.29 Thus, it may be beneficial to engineer an Ab with specificity for FZD family members broadened beyond that of OMP-18R5.

We hypothesized that broadening the specificity profile of a pan-FZD Ab to also target FZD4 would provide added anti-tumor properties, perhaps in part by inhibiting tumor angiogenesis. Here, we present the development and characterization of a Wnt-blocking anti-FZD Ab with the broadest specificity and highest efficacy reported to date. We employed a two-step phage display strategy in which selections for binding to the FZD7 ectodomain first yielded an Ab (F2) with a specificity profile matching that of OMP-18R5, and subsequent engineering yielded a variant (F2.A) with specificity expanded to include FZD4. Compared with F2 and OMP-18R5, F2.A further affects endothelial cell growth and displays enhanced anti-tumor properties.

Results

Selection and characterization of ABs binding to FZD4 and FZD7

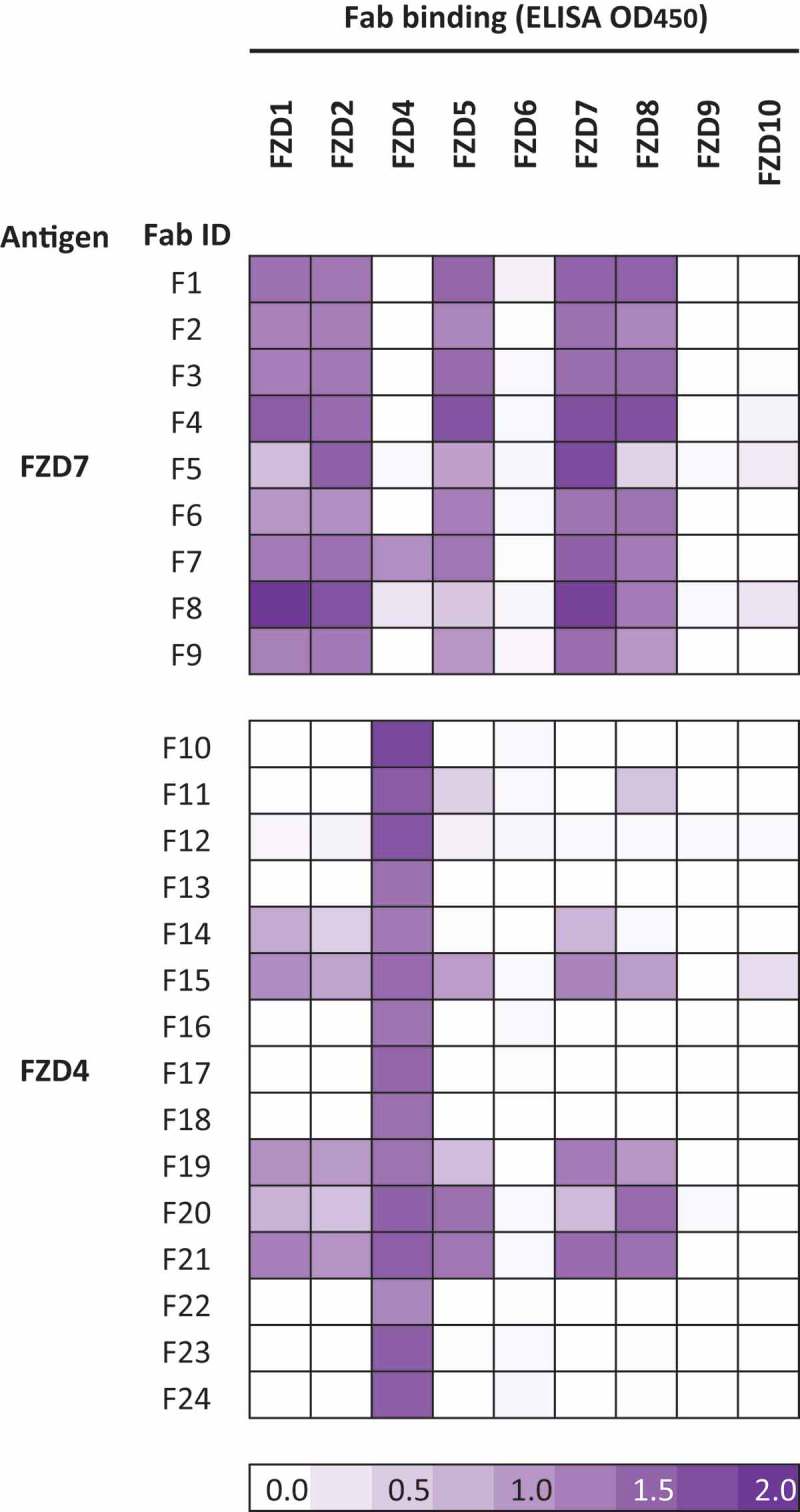

Using a highly functional naïve synthetic antigen-binding fragment (Fab) library,30 we performed separate phage display binding selections with the extracellular cysteine-rich domains (CRDs) of FZD4 and FZD7. Sequencing of individual binding clones from enriched phage pools identified 44 and 61 unique Fabs from the FZD4 and FZD7 selections, respectively, and a subset of these were purified as Fab proteins for further characterization (Figure 1). Due to the high sequence identity between FZD CRDs,31,32 we anticipated that the Fabs may display various patterns of binding specificity across the family, and thus we used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) to assess binding of each Fab to all human FZD CRDs (Figure 1), except for FZD3 CRD, which could not be purified. Similar to OMP-18R5, the nine Fabs selected with FZD7 bound to FZD1, 2, 5, 7, and 8, and one (F7) also bound to FZD4 (Figure1 and Fig. S1A). Amongst the Fabs selected with FZD4, we observed predominantly exclusive specificity for FZD4, although some did exhibit broader specificity (Figure 1). Thus, the selections yielded a series of Fabs with varying binding profiles for FZD receptors, the most inclusive of which bound to 6 of the 10 human FZD receptors.

Figure 1.

Specificities of naïve anti-FZD Fabs. Specificities of Fabs selected for binding to the CRD of FZD7 or FZD4 was assessed by ELISA with each immobilized FZD CRD, and the signals are shown in a purple gradient.

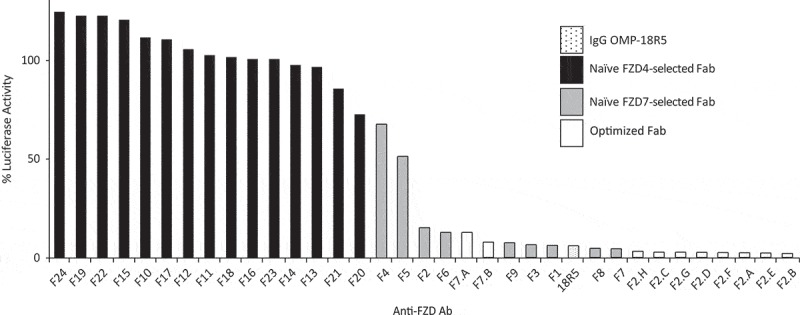

We assessed the ability of the Fabs to block signaling mediated by exogenous WNT3A in HEK293 cells using the pBAR luciferase reporter that faithfully reports on β-catenin-mediated transcriptional activity (Figure 2).33 None of the Fabs selected with FZD4 exhibited significant inhibition of signaling. In contrast, most of the Fabs selected with FZD7 exhibited strong inhibition of signaling that was comparable to the effect of IgG OMP-18R5, suggesting that these Fabs block WNT3A binding. Based on these data, we chose a subset of the Fabs selected with FZD7 as starting points for the design of second-generation phage-displayed libraries to further optimize specificity and efficacy.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of WNT3A signaling by anti-FZD Abs. HEK293T cells were transfected with a TCF reporter gene and stimulated with WNT3A conditioned media in the presence of indicated Fabs or IgG OMP-18R5 (x-axis). Luciferase activities, normalized to the activity in the presence of a negative control Fab, are shown (y-axis), and inhibition of WNT3A signaling is evidenced by reduced signals.

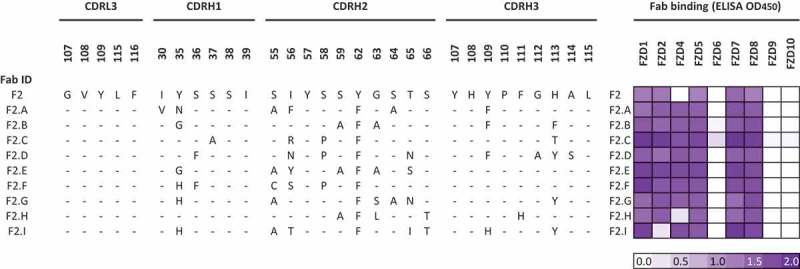

Optimization of Fab specificity and efficacy. Based on broad specificity for FZDs targeted by OMP-18R5, the absence of cross-reactivity with other FZDs except FZD4 in the case of F7 (Figure 1), and high efficacy (Figure 2), we chose six inhibitory Fabs (F1, F2, F3, F6, F7, F9) for further optimization to include FZD4 recognition. For each lead Fab, we constructed a second-generation phage-displayed library in which the three heavy chain complementarity-determining regions were diversified using a “soft randomization” strategy whereby each codon was designed to encode ~ 50% of the wild-type sequence and ~ 50% mutations.34-38 Following selection for binding to the FZD4 CRD, DNA sequencing and phage ELISAs revealed multiple unique clones with diverse binding specificities (data not shown). Fabs derived from F2 and F7 (Figure 3 and S1B) exhibited the desired specificity for FZD4 and the five FZDs targeted by OMP-18R5 (FZD1, 2, 5, 7 and 8). From the set of Fabs derived from F2, we identified seven that bound especially tightly to these six FZD receptors (Figure 3). Notably, these Fabs inhibited WNT3A-mediated signaling more efficaciously than IgG OMP-18R5, the first-generation Fabs or Fabs derived from F7 (Figure 2). Based on these data, we chose F2.A for further characterization.

Figure 3.

Sequences and specificities of optimized anti-FZD Fabs. The sequences of the complementarity-determining regions diversified in the Fab library are shown for Fab F2 and its derivatives. Residues are numbered according to IMGT standards,39 and dashes indicate identity with the F2 sequence. Fab binding was assessed by ELISA with each immobilized FZD CRD, and the signals are shown in a purple gradient.

F2.A and F2 were produced in the human IgG1 format and the size exclusion chromatography (SEC) profile of IgG F2.A was similar to that of OMP-18R5, as both eluted predominantly as single peaks with similar retention times (Fig. S1C). As expected, analysis of binding kinetics for FZD CRDs by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) showed that IgGs F2.A, F2 and OMP-18R5 bound to FZDs 1, 2, 5, 7 and 8, but did not bind to FZDs 6, 9 or 10 (data not shown), and only F2.A bound to FZD4 (Table 1). Notably, IgG F2.A bound to each of the six receptors with sub-nanomolar affinities, and thus exhibited enhanced affinity for five of six receptors compared with IgG F2 and all receptors compared with OMP-18R5, which generally exhibited only low nanomolar affinities. Specific binding of IgG F2.A to FZDs 1, 2, 4, 5, 7 and 8 was also confirmed by BioLayer interferometry (BLI, Fig. S1D). Moreover, we characterized the binding specificities on cells by flow cytometry, using a panel of ten Chinese hamster ovary cell lines,32 with each expressing a different myc-tagged FZD CRD anchored on the outside of the plasma membrane with a GPI anchor, and found the same specificity patterns for IgGs F2 and F2.A (Fig. S2A) as observed by ELISA (Figure 3) and SPR (Table 1).

Table 1.

Kinetic constants for IgGs binding to FZD CRDs determined by surface plasmon resonance.

|

ka (105 M−1s−1) |

kd (10−4 s−1) |

KD (nM) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen | F2 | F2.A | OMP-18R5 | F2 | F2.A | OMP-18R5 | F2 | F2.A | OMP-18R5 |

| FZD1 | 2.99 ± 0.02 | 2.82 ± 0.02 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 4.74 ± 0.05 | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 58 ± 2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 9 ± 3 |

| FZD2 | 4.33 ± 0.02 | 3.35 ± 0.02 | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 2.32 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.03 | 27.2 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 3 ± 1 |

| FZD4 | x | 12.5 ± 0.1 | x | x | 6.88 ± 0.06 | x | x | 0.4 ± 0.1 | x |

| FZD5 | 11.9 ± 0.1 | 8.93 ± 0.04 | 13.5 ± 0.3 | 8.19 ± 0.07 | 1.68 ± 0.03 | 36.7 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.4 |

| FZD7 | 5.98 ± 0.03 | 3.95 ± 0.02 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 2.08 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 5.7 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.3 ± 0.2 |

| FZD8 | 13.5 ± 0.2 | 9.220 ± 0.003 | 10.5 ± 0.2 | 8.53 ± 0.09 | 4.75 ± 0.04 | 20.5 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.5 |

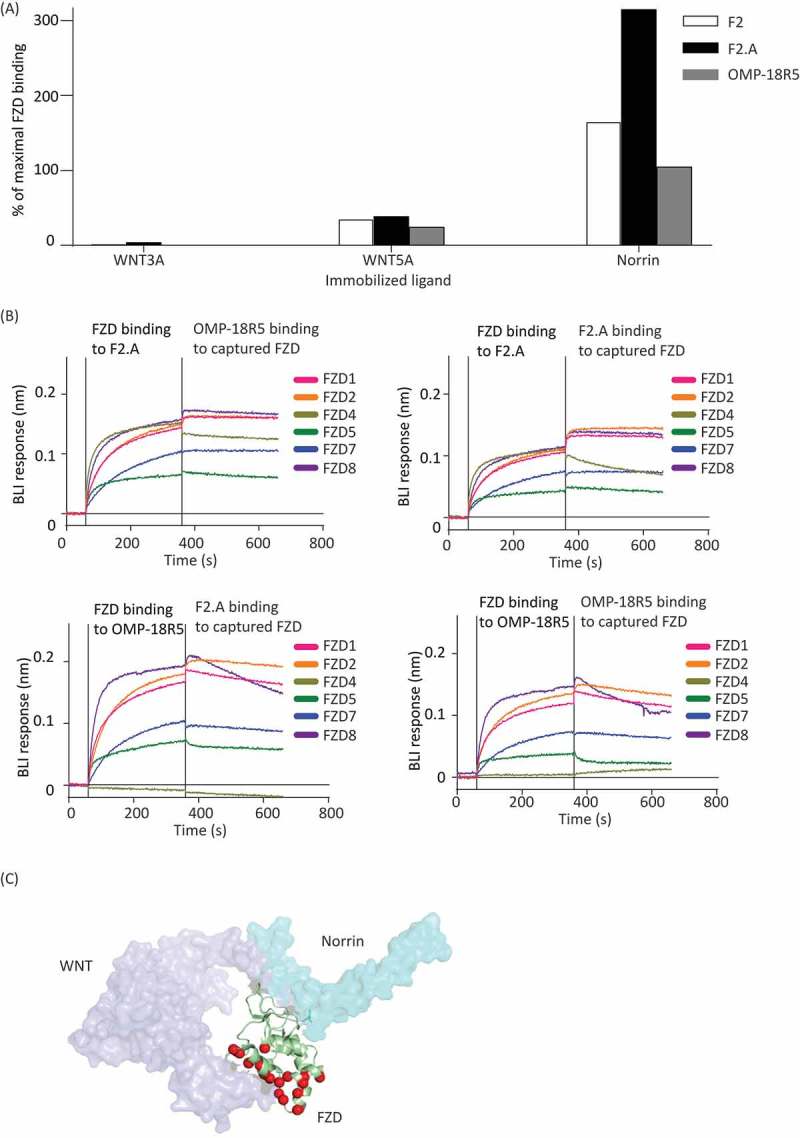

Competition ELISAs were then performed to assess the binding of OMP-18R5, F2 and F2.A in the presence of various Abs or FZD ligands. Binding of the FZD5 CRD to immobilized WNT3A or WNT5A was blocked by IgG OMP-18R5 and by Fabs F2 and F2.A, but none of the Abs were able to block binding of the FZD4 CRD to immobilized Norrin (Figure 4A). In fact, Fab F2.A actually enhanced binding of FZD4 CRD to Norrin, suggesting that F2.A stabilizes a conformation of FZD4 CRD that is better able to bind Norrin. We also tested the ability of IgGs F2.A and OMP-18R5 to simultaneously bind to FZDs by BLI (Figure 4B). An immobilized IgG was first allowed to bind to solution-phase FZD CRD, and then the ability of a second IgG to bind to the captured FZD CRD was assessed. As expected, neither IgG F2.A nor OMP-18R5 could bind to FZD CRD captured by itself, but, in addition, neither IgG could bind to FZD CRD captured by the other. Taken together, these results suggest that IgGs F2.A and OMP-18R5 bind to overlapping epitopes on FZD CRDs, and they block Wnt, but not Norrin, binding. Given that Wnt proteins contact two non-contiguous regions of FZDs,40 we speculate that the IgGs bind to a FZD region that interacts with Wnt but not with Norrin (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Comparison of anti-FZD Ab epitopes. (A) ELISA for detection of solution-phase FZD5 (left and center) or FZD4 (right) binding (y-axis) to immobilized WNT3A, WNT5A or Norrin (x-axis) in the presence of Fab F2 (white bars), Fab F2.A (black bars) or IgG OMP-18R5 (grey bars). Binding was normalized to FZD binding signal in the absence of solution-phase competitor (maximal binding). (B) Sensorgrams for BLI responses (y-axis) monitored in real-time (x-axis). Each sensorgram shows binding of analytes to a tip with immobilized IgG F2.A (top panels) or OMP-18R5 (bottom panels). The vertical line (360 seconds) indicates a switch from solution containing the indicated FZD CRD analyte to a solution containing the indicated analyte IgG. The absence of an increase in BLI response upon switching analytes indicates that the analyte IgG cannot bind to FZD CRD captured by the immobilized IgG. (C) Superposition of the crystal structures of mouse FZD8 (green ribbon) bound to xenopus WNT8 (purple surface, PDB accession 4F0A) and human FZD4 (not shown) bound to human Norrin (cyan surface, PDB accession 5BQC). FZD residues that contact WNT8 but not Norrin are shown as red spheres, and we speculate that the epitopes for Abs F2.A and OMP-18R5 overlap with this region.

Effects of anti-FZD IgGs on the proliferation of RNF43mutant human PDAC cells

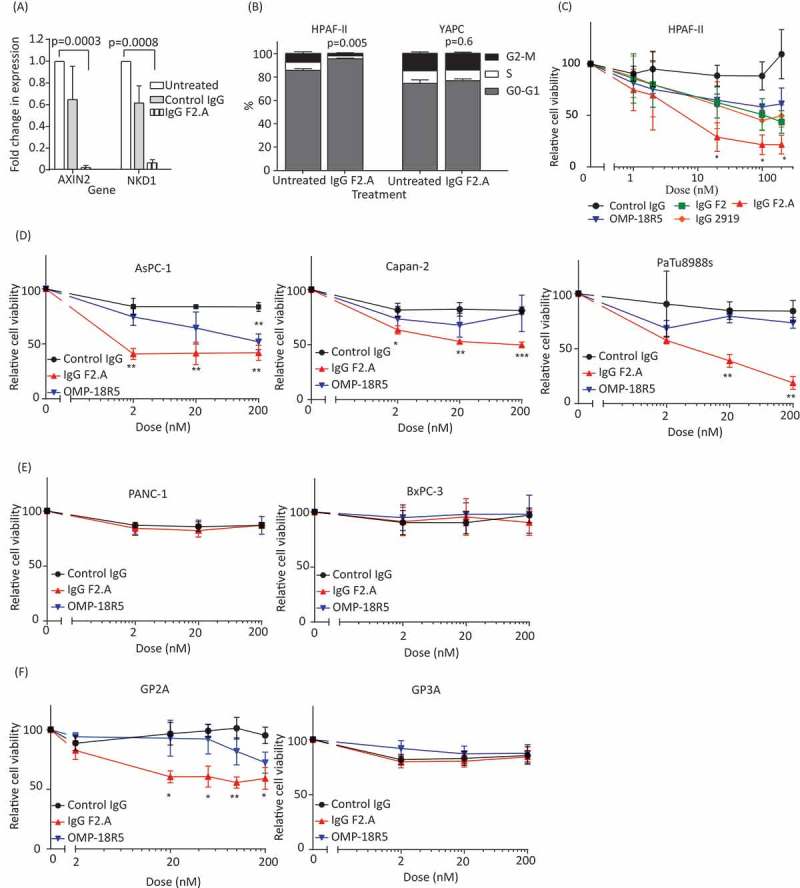

Previous reports have shown that RNF43 mutations are predictive of sensitivity to inhibition of upstream Wnt/FZD signaling in PDAC and other cancer types.41 We confirmed binding of Fab F2.A to PDAC cell lines by flow cytometry (Fig. S2B) and immunofluorescence staining (Fig. S2C-J). Treatment of the Wnt-dependent RNF43-mutant PDAC cell line HPAF-II with IgG F2.A robustly inhibited the expression of the Wnt-β-catenin target genes AXIN2 and NKD1 (Figure 5A). Moreover, consistent with our previous findings that the anti-proliferative properties of anti-FZD5 Abs in RNF43-mutant PDAC cells were due to cell cycle arrest and cytostasis,32 IgG F2.A induced G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in HPAF-II cells, but not in RNF43-wildtype YAPC cells (Figure 5B). We conclude that IgG F2.A is an efficacious inhibitor of Wnt-β-catenin signaling that induces cell cycle arrest in RNF43-mutant PDAC cells.

Figure 5.

Effects of anti-FZD Abs on PDAC cell signaling and growth. (A) Effects of anti-FZD Abs on expression of the Wnt target genes AXIN2 and NKD1. Gene expression in HPAF-II cells was assessed by RT-qPCR after six days of treatment with 200 nM IgG F2.A or a negative control IgG. Unpaired t-tests, bars represent mean ± s.d. normalized to β-actin expression, n = 2 independent experiments each performed in triplicate. (B) Effects of IgG F2.A on cell cycle phase in HPAF-II and YAPC cells, assessed by DNA content. Cells were treated for six days with 200 nM IgG F2.A or phosphate-buffered saline (untreated) control and percentages of cell populations in G0/G1, S and G2/M phase were determined. Bars represent mean ± s.d., n = 2 independent experiments, with a two-tailed unpaired t-test on proportion of cells in G0/G1, compared to control. (C-F) Cell viability assays with the RNF43-mutant PDAC cell lines (C) HPAF-II, (D) AsPC-1, Capan-2 and PaTu8988s, (E) the RNF43 wild-type PDAC cell lines PANC-1 and BxPC-3, and (F) patient-derived RNF43-mutant (GP2A) and RNF43-wildtype (GP3A) PDAC cell lines. Cells were treated with the indicated IgG for 6 days, and viability was determined by Beckman cell counts (GP2A) or Alamar blue assays (all others). Points represent means ± s.d., n = 3 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, and *P < 0.05, two-tailed unpaired t-tests using Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparisons without assuming consistent s.d.

We previously used genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 genetic screens to identify FZD5 as the top context-dependent fitness gene in RNF43-mutant PDAC cells, and we showed that an antagonistic Ab targeting FZD5 and FZD8 (IgG 2919) inhibited growth of these cancers in vitro and in vivo.32 We therefore tested various anti-FZD IgGs for their effects on the growth of RNF43-mutant PDAC cells. IgG F2.A inhibited the proliferation of HPAF-II cells more effectively than IgGs 2919, F2 and OMP-18R5 (Figure 5C). IgG F2.A was also more effective than IgG OMP-18R5 for inhibiting proliferation of other RNF43-mutant PDAC cell lines, including AsPC-1, Capan-2 and PaTu8988s (Figure 5D), and neither Ab affected the growth of the RNF43-wildtype PDAC cell lines PANC-1 and BxPC-3 (Figure 5E). Similarly, IgG F2.A inhibited growth of patient-derived PDAC GP2A cells that harbour an RNF43 mutation, but did not affect RNF43-wildtype GP3A cells (Figure 5F), despite strong binding of IgG F2.A to the surfaces of both cell types (Fig. S2I-J). Together, these results indicate that IgG F2.A can effectively inhibit the proliferation of RNF43-mutant PDAC cells.

Effects of anti-FZD IgGs on angiogenesis

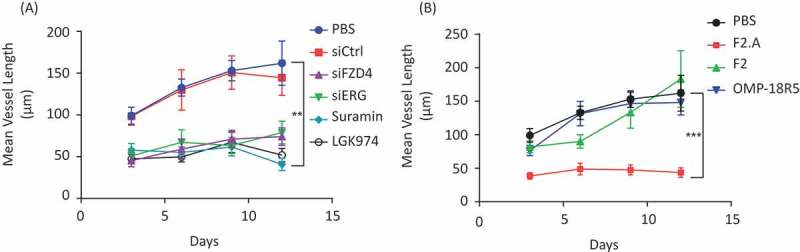

Tumor angiogenesis represents a cancer hallmark, and is targeted by cancer therapies such as anti- vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) bevacizumab.42,43 The endothelial transcription factor ERG promotes growth and vascular stability by regulating the Wnt-β-catenin pathway through FZD4 expression.26 Therefore, expanding the specificity of anti-FZD Abs to target FZD4 may provide added anti-tumor properties by inhibiting angiogenesis. We first demonstrated that Wnt ligands and FZD4 were required for endothelial tube formation using a human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC)-coated fibrin gel bead assay. Knockdown of FZD4 and the Porcupine inhibitor LGK974, which inhibits all Wnt protein production, each inhibited HUVEC tube elongation to a similar extent as knockdown of ERG or the VEGF kinase inhibitor suramin (Figure 6A).44 We compared the ability of different anti-FZD Abs to inhibit HUVEC tube elongation and showed that IgG F2.A could robustly inhibit tube elongation, whereas IgGs F2 and OMP-18R5 were ineffective (Figure 6B and Fig. S3). Thus, we conclude that expanding the specificity of anti-FZD Abs to target FZD4 confers the ability to interfere with endothelial cell tubule formation, which could translate into beneficial anti-angiogenic properties for cancer treatment.

Figure 6.

Effects of IgGs on angiogenesis. (A) Time-course of mean endothelial vessel length for HUVECs treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), siCtrl, siFZD4, siERG, 30 µM Suramin or 1 µM LGK974. Bars represent mean ± s.e.m., n = 4 independent experiments. **P < 0.01, two-tailed, unpaired t-test. (B) Time-course of mean endothelial vessel length for HUVECs treated with PBS or 300 nM IgG F2.A, F2 or OMP-18R5. Bars represent mean ± s.e.m., n = 4 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001, two-tailed, unpaired t-test.

Discussion

The dysregulation of Wnt-β-catenin signaling in cancer and other diseases has generated strong interest in developing therapeutic inhibitors of this pathway. Given that most mutations leading to activation of the Wnt-β-catenin pathway in cancers occur within intracellular components of the pathway, the rationale for targeting FZD or other cell surface receptors for these indications has been questioned. However, considering the cancer stem cell hypothesis45 and the pervasive role of Wnt-β-catenin signaling in stem cell self-renewal, one intriguing possibility is that anti-FZD Abs could broadly target the cells that fuel tumor growth and are usually resistant to conventional therapy. Similarly, the realization that activation of Wnt-β-catenin signaling in tumor cells is associated with the absence of T cell infiltration46,47 suggests important roles for this pathway in tumor immune evasion and the attractive possibility that targeting Wnt-FZD circuits within tumor cells could represent an immune potentiation strategy that restores sensitivity to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Consequently, anti-FZD Abs could be effective against various tumor types independent of their genotypes. Additionally, the recent identification of mutations within the E3 ubiquitin ligases RNF43 and ZNFR3, which regulate FZD receptor levels, and the finding of R-spondin fusions in other cancers, serve as examples of biomarkers that could enable selection of patients, based on their tumor genotypes, who would benefit from agents interfering with the constitutive activation of cell surface receptors involved in Wnt-β-catenin signaling.12,13,16,48

In addition to being overactivated in multiple cancers, the Wnt-β-catenin signaling axis is involved in embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis.1,2 Hence, the question of toxicity associated with targeting the Wnt pathway has been raised, and the importance of Wnt signaling for stem cell development in the intestine and skin,49 has prompted caution for the development of inhibitors of global Wnt signaling.19 One strategy to target the Wnt pathway has been the development of inhibitors for the acyltransferase Porcupine, which catalyzes the palmitoylation of Wnt ligands, a modification required for their secretion and activity.50,51 One such inhibitor (LGK974) caused intestinal toxicity in mice at high concentrations, but was safe and efficacious for tumor growth inhibition at lower concentrations, suggesting that a therapeutic window exists for safely targeting WNT-dependent cancers.50 Clinical trials have been performed and are underway to evaluate the efficacy of these agents for cancer treatment (e.g., NCT02278133, NCT03447470).

Abs targeting specific FZDs or other cell surface receptors of the pathway implicated in specific diseases could represent a safer strategy. However, in vivo studies are needed for evaluation of potential toxicity and for fine-tuning the safety and the efficacy of Abs targeting FZD receptors. Pre-clinical and clinical studies of OMP-18R5 revealed anti-tumor efficacy against various tumor types and manageable toxicity.18 Here, we developed a novel anti-FZD Ab that recognized FZD4 in addition to the five FZDs targeted by OMP-18R5, illustrating that rational engineering37,38,52 can be applied to develop anti-FZD Abs with broadened specificities and improved therapeutic properties. Indeed, although FZD4 has not been shown to be involved directly in tumor angiogenesis, evidence suggests that it is important in regulating endothelial cell growth in various contexts, a property that could result in added therapeutic benefits beyond those gained by targeting FZD4 in the tumor itself. Importantly, severe disease phenotypes resulting from impaired Norrin-FZD4 signaling, such as in Norrie disease53 or familial exudative vitreoretinopathy,54 are prompting caution for development of drugs targeting FZD4. Consistent with different modes for Wnt and Norrin binding to FZD4,29 F2.A blocked Wnt binding to FZD5 but did not compete with Norrin for binding to the FZD4 CRD (Figure 4A and C), suggesting that F2.A may inhibit only Wnt-FZD4-dependent processes.

IgG F2.A displayed greater efficacy for inhibition of FZD5-dependent growth of RNF43-mutant pancreatic cancer cells than did either OMP-18R5 or IgG 2919, which targets only FZD5 and FZD8.32 In part, this could be explained by the higher affinity of IgG F2.A for FZD5 compared to OMP-18R5 (Table 1), but, considering that the affinities of IgGs F2.A and 2919 for FZD5 are similar, the increased efficacy likely derives from different properties of F2.A, such as variations within the epitopes targeted by the different Abs. In summary, with broad binding preference to six of the 10 human FZD receptors, F2.A is the most efficacious anti-FZD Ab developed to date as a potential cancer therapeutic.

Materials and methods

Materials and methods are described in detail in Supplemental Information (SI), Materials and methods. In brief, combinatorial mutagenesis was applied for phage-displayed Fab library construction36-38 and selections for FZD-binding Fab-phage were performed with naïve library F55 or libraries designed for Fab optimization. Fabs were produced as previously described,38,56 with modifications detailed in the SI, and IgGs were expressed in HEK293F cells.

Biophysical characterizations of the Abs were performed using ELISAs, SPR, BLI and SEC. ELISAs were used to asses direct binding of Abs to immobilized FZD CRDs and to asses the competition between FZD and Abs for binding to immobilized WNT3A, WNT5A or Norrin. Binding kinetics were measured by SPR and the ability of Abs to simultaneously bind to FZD CRDs was assessed by BLI. SEC was used to assess the aggregation status of Abs. TopFlash reporter assays in HEK293T cells were used to assess inhibition of β-catenin-mediated transcriptional activity induced by exogenous WNT3A. Binding of Abs to cells was tested by immunofluorescence microscopy (Opera QEHS, PerkinElmer) and flow cytometry (FACSCanto II, BD Biosciences), and data were analysed using Columbus software (Donnelly Centre, University of Toronto) or FlowJo Software (FlowJo, LLC), respectively. Reverse transcription and quantitative real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems) were performed to measure relative gene expression with quantification relative to untreated control as described.57 Cell proliferation assays included Alamar Blue assays (Invitrogen) and automated cell counting (Beckman Coulter). siRNA cell transfections were used to asses the role of FZD4 in HUVEC tube elongation and the in vitro fibrin gel bead assay for angiogenesis was performed as described,58 with minor modifications detailed in the SI.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (364969) and the Canadian Cancer Society (705045) to SA; and grants from Genome Canada (OGI-052), the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation (RE05-011), and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-93725, renewal MOP-136944) to SS and JM.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lia Cardarelli, Lynda Ploder, Kirsten Krastel and Sherry Lamb for Fab production, Lori Moffat for IgG production, Patricia Mero for help with imaging, and Isabelle Pot for reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Authors have filed a patent.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Abbreviations

- Ab

antibody

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli

- AXIN

axis inhibition protein

- BLI

biolayer interferometry

- CK1α,

casein kinase 1 alpha

- CRD

cysteine-rich domain

- CRISPR

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ERG

erythroblast transformation specific-related gene

- Fab

antigen-binding fragment

- FZD

frizzled receptor

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- GSK3α/β

glycogen synthase kinase-3 alpha/beta

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IMGT

the international immunogenetics database

- LEF

lymphoid enhancer factor

- LRP6

low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6

- NKD1

naked cuticle homolog 1

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- RNF43

E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RNF43

- ROR1

receptor tyrosine kinase like orphan receptor 1

- ROR2

receptor tyrosine kinase like orphan receptor 2

- RYK

receptor-like tyrosine kinase

- SEC

size exclusion chromatography

- siCtrl

small interfering control RNA

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- TCF

T-cell factor

- VE-cadherin

vascular endothelial cadherin

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- ZNFR3

E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase ZNFR3

References

- 1.Chien AJ, Conrad WH, Moon RT.. A Wnt survival guide: from flies to human disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1614–1627. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoppler S, Moon RT. Wnt signaling in development and disease molecular mechanisms and biological functions. Hoboken (New Jersey): Wiley Blackwell; 2014. 1 online resource. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angers S, Moon RT. Proximal events in Wnt signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:468–477. doi: 10.1038/nrm2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart MJ, De Los Santos R, Albert IN, Rubinfeld B, Polakis P. Downregulation of beta-catenin by human Axin and its association with the APC tumor suppressor, beta-catenin and GSK3 beta. Curr Biol. 8;1998:573–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munemitsu S, Albert I, Souza B, Rubinfeld B, Polakis P. Regulation of intracellular beta-catenin levels by the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor-suppressor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 92;1995:3046–3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nusse R, Varmus HE. Many tumors induced by the mouse mammary tumor virus contain a provirus integrated in the same region of the host genome. Cell. 31;1982:99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polakis P. The many ways of Wnt in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anastas JN, Moon RT. WNT signalling pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:11–26. doi: 10.1038/nrc3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nusse R, Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell. 2017;169:985–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu W, Dong X, Mai M, Seelan RS, Taniguchi K, Krishnadath KK, Halling KC, Cunningham JM, Boardman LA, Qian C, et al. Mutations in AXIN2 cause colorectal cancer with defective mismatch repair by activating beta-catenin/TCF signalling. Nat Genet. 2000;26:146–147. doi: 10.1038/79859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satoh S, Daigo Y, Furukawa Y, Kato T, Miwa N, Nishiwaki T, Kawasoe T, Ishiguro H, Fujita M, Tokino T, et al. AXIN1 mutations in hepatocellular carcinomas, and growth suppression in cancer cells by virus-mediated transfer of AXIN1. Nat Genet. 2000;24:245–250. doi: 10.1038/73448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giannakis M, Hodis E, Jasmine Mu X, Yamauchi M, Rosenbluh J, Cibulskis K, Saksena G, Lawrence MS, Qian ZR, Nishihara R, et al. RNF43 is frequently mutated in colorectal and endometrial cancers. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1264–1266. doi: 10.1038/ng.3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assié G, Letouzé E, Fassnacht M, Jouinot A, Luscap W, Barreau O, Omeiri H, Rodriguez S, Perlemoine K, René-Corail F, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of adrenocortical carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:607–612. doi: 10.1038/ng.2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hao H-X, Xie Y, Zhang Y, Charlat O, Oster E, Avello M, Lei H, Mickanin C, Liu D, Ruffner H, et al. ZNRF3 promotes Wnt receptor turnover in an R-spondin-sensitive manner. Nature. 2012;485:195–200. doi: 10.1038/nature11019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koo B-K, Spit M, Jordens I, Low TY, Stange DE, Van De Wetering M, Van Es JH, Mohammed S, Heck AJR, Maurice MM, et al. Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature. 2012;488:665–669. doi: 10.1038/nature11308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seshagiri S, Stawiski EW, Durinck S, Modrusan Z, Storm EE, Conboy CB, Chaudhuri S, Guan Y, Janakiraman V, Jaiswal BS, et al. Recurrent R-spondin fusions in colon cancer. Nature. 2012;488:660–664. doi: 10.1038/nature11282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishnamurthy N, Kurzrock R. Targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in cancer: update on effectors and inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;62:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurney A, Axelrod F, Bond CJ, Cain J, Chartier C, Donigan L, Fischer M, Chaudhari A, Ji M, Kapoun AM, et al. Wnt pathway inhibition via the targeting of Frizzled receptors results in decreased growth and tumorigenicity of human tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:11717–11722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120068109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahn M. Can we safely target the WNT pathway? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:513–532. doi: 10.1038/nrd4233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agarwal P, Zhang B, Ho Y, Cook A, Li L, Mikhail FM, Wang Y, McLaughlin ME, Bhatia R. Enhanced targeting of CML stem and progenitor cells by inhibition of porcupine acyltransferase in combination with TKI. Blood. 2017;129(8):1008–1020. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-714089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tickenbrock L, Hehn S, Sargin B, Choudhary C, Bäumer N, Buerger H, Schulte B, Müller O, Berdel WE, Müller-Tidow C, et al. Activation of Wnt signalling in acute myeloid leukemia by induction of Frizzled-4. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:1215–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin X, Jeon H-Y, Joo KM, Kim J-K, Jin J, Kim SH, Kang BG, Beck S, Lee SJ, Kim JK, et al. Frizzled 4 regulates stemness and invasiveness of migrating glioma cells established by serial intracranial transplantation. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3066–3075. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pardo OE, Castellano L, Munro CE, Hu Y, Mauri F, Krell J, Lara R, Pinho FG, Choudhury T, Frampton AE, et al. miR-515-5p controls cancer cell migration through MARK4 regulation. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:570–584. doi: 10.15252/embr.201540970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta S, Iljin K, Sara H, Mpindi JP, Mirtti T, Vainio P, Rantala J, Alanen K, Nees M, Kallioniemi O. FZD4 as a mediator of ERG oncogene-induced WNT signaling and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6735–6745. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang J, Yu C, Chen M, Zhang H, Tian S, Sun C. Reduction of miR-29c enhances pancreatic cancer cell migration and stem cell-like phenotype. Oncotarget. 2015;6:2767–2778. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birdsey GM, Shah AV, Dufton N, Reynolds LE, Osuna Almagro L, Yang Y, Aspalter IM, Khan ST, Mason JC, Dejana E, et al. The endothelial transcription factor ERG promotes vascular stability and growth through Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Dev Cell. 2015;32:82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Junge HJ, Yang S, Burton JB, Paes K, Shu X, French DM, Costa M, Rice DS, Ye W. TSPAN12 regulates retinal vascular development by promoting Norrin- but not Wnt-induced FZD4/beta-catenin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Rattner A, Zhou Y, Williams J, Smallwood PM, Nathans J. Norrin/Frizzled4 signaling in retinal vascular development and blood brain barrier plasticity. Cell. 2012;151:1332–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang TH, Hsieh FL, Zebisch M, Harlos K, Elegheert J, Jones EY. Structure and functional properties of Norrin mimic Wnt for signalling with Frizzled4, Lrp5/6, and proteoglycan. Elife. 2015;4:06554. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang H, Economopoulos NO, Liu BA, Uetrecht A, Gu J, Jarvik N, Nadeem V, Pawson T, Moffat J, Miersch S, et al. Selection of recombinant anti-SH3 domain antibodies by high-throughput phage display. Protein Sci. 2015;24:1890–1900. doi: 10.1002/pro.2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fredriksson R, Lagerstrom MC, Lundin LG, Schioth HB. The G-protein-coupled receptors in the human genome form five main families. Phylogenetic analysis, paralogon groups, and fingerprints. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1256–1272. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.6.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinhart Z, Pavlovic Z, Chandrashekhar M, Hart T, Wang X, Zhang X, Robitaille M, Brown KR, Jaksani S, Overmeer R, et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screens reveal a Wnt-FZD5 signaling circuit as a druggable vulnerability of RNF43-mutant pancreatic tumors. Nat Med. 2017;23:60–68. doi: 10.1038/nm.4219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biechele TL, Moon RT. Assaying beta-catenin/TCF transcription with beta-catenin/TCF transcription-based reporter constructs. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;468:99–110. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-249-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunkel TA, Roberts JD, Zakour RA. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sidhu SS, Feld BK, Weiss GA. M13 bacteriophage coat proteins engineered for improved phage display. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;352:205–219. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-187-8:205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nilvebrant J, Sidhu SS. Construction of synthetic antibody phage-display libraries. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1701:45–60. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7447-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajan S, Sidhu SS. Simplified synthetic antibody libraries. Methods Enzymol. 2012;502:3–23. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416039-2.00001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tonikian R, Zhang Y, Boone C, Sidhu SS. Identifying specificity profiles for peptide recognition modules from phage-displayed peptide libraries. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1368–1386. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lefranc MP, Pommie C, Ruiz M, Giudicelli V, Foulquier E, Truong L, Thouvenin-Contet V, Lefranc G. IMGT unique numbering for immunoglobulin and T cell receptor variable domains and Ig superfamily V-like domains. Dev Comp Immunol. 2003;27:55–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janda CY, Waghray D, Levin AM, Thomas C, Garcia KC. Structural basis of Wnt recognition by Frizzled. Science. 2012;337:59–64. doi: 10.1126/science.1222879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang X, Hao H-X, Growney JD, Woolfenden S, Bottiglio C, Ng N, Lu B, Hsieh MH, Bagdasarian L, Meyer R, et al. Inactivating mutations of RNF43 confer Wnt dependency in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:12649–12654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307218110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zondor SD, Medina PJ. Bevacizumab: an angiogenesis inhibitor with efficacy in colorectal and other malignancies. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1258–1264. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shih T, Lindley C. Bevacizumab: an angiogenesis inhibitor for the treatment of solid malignancies. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1779–1802. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waltenberger J, Mayr U, Frank H, Hombach V. Suramin is a potent inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor. A contribution to the molecular basis of its antiangiogenic action. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:1523–1529. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kreso A, Dick JE. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:275–291. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grasso CS, Giannakis M, Wells DK, Hamada T, Mu XJ, Quist M, Nowak JA, Nishihara R, Qian ZR, Inamura K, et al. Genetic mechanisms of immune evasion in colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:730–749. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015;523:231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature14404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang K, Yuen ST, Xu J, Lee SP, Yan HH, Shi ST, Siu HC, Deng S, Chu KM, Law S, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and comprehensive molecular profiling identify new driver mutations in gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2014;46:573–582. doi: 10.1038/ng.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haegebarth A, Clevers H. Wnt signaling, lgr5, and stem cells in the intestine and skin. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:715–721. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu J, Pan S, Hsieh MH, Ng N, Sun F, Wang T, Kasibhatla S, Schuller AG, Li AG, Cheng D, et al. Targeting Wnt-driven cancer through the inhibition of Porcupine by LGK974. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20224–20229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314239110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Madan B, Virshup DM. Targeting Wnts at the source–new mechanisms, new biomarkers, new drugs. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:1087–1094. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fellouse FA, Esaki K, Birtalan S, Raptis D, Cancasci VJ, Koide A, Jhurani P, Vasser M, Wiesmann C, Kossiakoff AA, et al. High-throughput generation of synthetic antibodies from highly functional minimalist phage-displayed libraries. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:924–940. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nikopoulos K, Venselaar H, Collin RW, Riveiro-Alvarez R, Boonstra FN, Hooymans JM, Mukhopadhyay A, Shears D, Van Bers M, De Wijs IJ, et al. Overview of the mutation spectrum in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and Norrie disease with identification of 21 novel variants in FZD4, LRP5, and NDP. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:656–666. doi: 10.1002/humu.21250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robitaille J, MacDonald ML, Kaykas A, Sheldahl LC, Zeisler J, Dube MP, Zhang L-H, Singaraja RR, Guernsey DL, Zheng B, et al. Mutant frizzled-4 disrupts retinal angiogenesis in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Nat Genet. 2002;32:326–330. doi: 10.1038/ng957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Persson H, Ye W, Wernimont A, Adams JJ, Koide A, Koide S, Lam R, Sidhu SS. CDR-H3 diversity is not required for antigen recognition by synthetic antibodies. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:803–811. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gakhal AK, Jensen TJ, Bozoky Z, Roldan A, Lukacs GL, Forman-Kay J, Riordan JR, Sidhu SS. Development and characterization of synthetic antibodies binding to the cystic fibrosis conductance regulator. MAbs. 2016;8:1167–1176. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2016.1186320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakatsu MN, Davis J, Hughes CC. Optimized fibrin gel bead assay for the study of angiogenesis. J Vis Exp. 2007;3:186. doi: 10.3791/186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.