Abstract

Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms constitute a diagnostic spectrum ranging from adenoma to mucinous adenocarcinoma. To date, many classification systems have been proposed to reflect the histomorphological diversity of neoplasms in this range and their clinical correspondence, and also to form a common terminology between the pathologist and clinicians. The aim of this review is to provide an updated perspective on the pathological features of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Using the 2016 Modified Delphi Consensus Protocol (Delphi) and the Eighth Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual, 19 cases presented from June 2011 to December 2016 were evaluated and diagnosed with appendiceal mucinous neoplasia. According to the Delphi, non-carcinoid epithelial tumours of the appendix were categorized in eight histomorphological architectural groups. These groups are adenoma, serrated polyp, low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm, high-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm, mucinous adenocarcinoma, poorly-differentiated adenocarcinoma with signet-ring, signet-ring cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. The most common symptom was right lower quadrant pain. The median age of these cases was 60±15 years. There was a preponderance of females (F/M: 15/4). In our re-evaluation, six cases were diagnosed as serrated polyp. There were 11 cases in the LAMN group and two cases in the mucinous adenocarcinoma group. Using the Delphi and the AJCC manual, there were many changes in the classification, evaluation and treatment of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. These classification systems have facilitated the compatibility and communication of clinicians and pathologists and have guided clinicians on treatment methods.

Keywords: Mucinous neoplasms, appendix vermiformis, gastrointestinal tract

INTRODUCTION

Appendiceal tumors are rare neoplasms that are detected in approximately 1% of appendectomy specimens (1). Major categorization of the primary appendiceal neoplasms includes epithelial tumors, mesenchymal tumors, and lymphomas (2). Primary epithelial tumors of the appendix are classified as mucinous tumors, neuroendocrine tumors, and mixed glandular and endocrine tumors (3). The most common non-carcinoid tumors of the appendix are mucinous adenocarcinoma (4). Mucinous neoplasms of the appendix constitute a heterogeneous group of neoplasms ranging from adenoma to mucinous adenocarcinoma (2).

Various classification systems have been proposed by McDonald and Woodruff (5), Pai et al. (6), Misdraji et al. (7), Carr et al. (8,10), and the World Health Organization (WHO) 2010 (9) guidelines (Table 1). In addition, the Eighth Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual was published in 2017 with important changes in the staging of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (LAMNs) (11).

Table 1.

Various classification systems have been proposed by McDonald and Woodruff (5), Pai et al. (6), Misdraji et al. (7), Carr et al. (8,10), and the WHO 2010 (9) guideline

| McDonald and Woodruff (5) (1940) | Carr et al. (10) (1995) | Misdraji et al. (7) (2003) | Pai et al. (6) (2009) | World Health Organization (2010) | Carr et al. (8) Modified Delphi Consensus (2016) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -Benign mucocele -Cystadenocarcinoma |

-Mucocele -Hyperplastic polyp -Adenoma -Cystadenoma -Carcinoma -Cystadenocarcinoma -Mucinous tumors of uncertain malignant potential |

-Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm -Mucinous adenocarcinoma -Discordant |

-Mucinous adenoma -Low-grade mucinous neoplasm, low risk of recurrence -Low-grade mucinous neoplasm, high risk of recurrence -Mucinous adenocarcinoma |

-Adenoma -Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm -Mucinous adenocarcinoma mucinous neoplasm |

-Adenoma -Serrated polyp -Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm -High-grade appendiceal -Mucinous adenocarcinoma -Poorly differentiated (mucinous) adenocarcinoma with signet ring -(Mucinous) Signet ring cell carcinoma -Adenocarcinoma |

Carr et al. (8) reviewed appendiceal neoplasm cases in order to apply the changes in the classification system in accordance to the 2012 meeting of the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International and using the 2016 Modified Delphi Consensus Protocol (Delphi). They categorized non-carcinoid epithelial tumors of the appendix into eight histomorphological architectural groups: adenoma, serrated polyp, LAMN, high-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (HAMN), mucinous adenocarcinoma (well/moderately/poorly differentiated), signet ring cell low-differentiated (mucinous) adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell (mucinous) adenocarcinoma, and adenocarcinoma (Table 2) (8).

Table 2.

Using the 2016 Modified Delphi Consensus Protocol, Carr et al. (8) categorized non-carcinoid epithelial tumors of the appendix in eight histomorphological architectural groups

| Lesion | Terminology | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adenoma (traditional colorectal type) | Tubular, tubulovillous, villous adenoma |

| 2 | Tumor with serrated features | Serrated polyp |

| 3 | Low-grade cytologic atypia and loss of the muscularis mucosa layer, pushing invasion, acellular mucin in the wall, mucin outside the appendix, submucosal fibrosis | Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm |

| 4 | High-grade cytologic atypia without infiltrative invasion | High-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm |

| 5 | Infiltrative invasion (single cells), desmoplasia | Mucinous adenocarcinoma |

| 6 | Signet ring cells (≤50%) | Mucinous adenocarcinoma with signet cells |

| 7 | Signet ring cells (>50%) | Signet cell carcinoma |

| 8 | Adenocarcinoma (non-mucinous) | Adenocarcinoma |

The aim of the present study was to utilize a small case series and a detailed review of the literature to provide an updated perspective on the pathological features of the appendiceal mucinous neoplasms using the Delphi and the AJCC manual.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Using the Delphi and the AJCC manual, 19 cases from June 2011 to December 2016 were evaluated and diagnosed with appendiceal mucinous neoplasm using the WHO 2010 guidelines. These cases were evaluated considering the histomorphological and architectural findings and the literature.

Clinical data included patient age, sex, serum levels of tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cancer antigen (CA) 19-9, CA 125, and CA 15-3), and recurrence status. On macroscopic examination, the presence of dilatation and perforation, maximum diameter of the specimen, surgical border, and presence of mucin and on microscopic examination, the level of architectural and cytologic atypia, intactness of the muscularis mucosa, submucosal fibrosis, hyalinization, presence of atrophy in the lymphoid tissue, presence of invasion pushing toward the appendiceal wall, desmoplasia, and presence of single cell invasion were examined by the same pathological experts, who then reached a consensus (Tables 3A, 3B). All macroscopic specimens of the cases were sampled and evaluated. Paraffin blocks containing formalin-fixated tissues were sliced into a thickness of 4 μm. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections were available for review in 19 cases. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms were categorized into eight groups according to the Delphi based on architectural and histomorphological findings and the degree of cytologic atypia (8) (Table 2).

Table 3a.

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data and architectural and histomorphological findings of 19 cases who were diagnosed with appendiceal mucinous neoplasm

| Case | Age (years) | Gender | First DX | Last DX | Diameter of the lumen (CM) | Epithelial serration | Epithelial atypia | Loss of muscularis mucosa layer | Submucosal fibrosis | Pushing invasion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40 | M | Mucocele | LAMN | 0.5 | − | + | − | + | − |

| 2 | 30 | F | SA, focal HGD | SP, focal HGD | 0.5 | + | + | − | − | − |

| 3 | 47 | M | Mucocele | LAMN | 2.5 | − | − | − | + | − |

| 4 | 35 | F | LGMN | LAMN | 6.5 | − | + | + | + | − |

| 5 | 65 | F | Mucocele | LAMN | 3 | − | + | + | + | − |

| 6 | 79 | F | SP | SP | 1.5 | + | − | − | − | − |

| 7 | 68 | F | LGMN | LAMN | 1.5 | − | + | + | + | − |

| 8 | 74 | M | MC | LAMN | 4 | − | + | + | + | − |

| 9 | 80 | F | HC | SP | 1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| 10 | 78 | F | MAC | MAC, SRC | 1 | − | + | + | + | + |

| 11 | 64 | F | LAMN | LAMN | 2.5 | + | + | + | + | − |

| 12 | 65 | F | LAMN | LAMN | 0.8 | + | + | + | + | − |

| 13 | 55 | F | LAMN | LAMN | 1.3 | − | + | + | + | − |

| 14 | 84 | F | LAMN | LAMN | 4 | − | + | + | + | − |

| 15 | 46 | M | SSA | SP | 1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| 16 | 68 | F | SSA | LAMN | 1.5 | − | + | + | + | + |

| 17 | 57 | F | MAC | MAC | 4.5 | − | + | + | + | + |

| 18 | 54 | F | SSA | SP | 0.5 | + | − | − | − | − |

| 19 | 61 | F | SSA | SP | 1.3 | + | − | 0 | − | − |

F: female; M: male; SA: serrated adenoma; SP: serrated polyp; SSA: sessile serrated adenoma; HP: hyperplastic polyp; LGD: low-grade dysplasia; HGD: high-grade dysplasia; MC: mucinous cystadenoma; SRC: signet ring cell; LGMN: low-grade mucinous neoplasm; EAC: endometrioid adenocarcinoma; LAMN: low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm; RCC: renal cell carcinoma; MAC: mucinous adenocarcinoma; OSC: ovarian serous carcinoma; NET: neuroendocrine tumor; AC: adenocarcinoma

Table 3b.

Histomorphological findings of 19 cases who were diagnosed with appendiceal mucinous neoplasm

| Case | Infiltrative invasion | Acellular mucin on the wall | Epithelial growth | Loss of lymphoid aggregates | Extra-appendiceal mucin | Rupture | Surgical margin involvement | Other findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 2 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 3 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 4 | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | NET (WHO Grade I) |

| 5 | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | EAC (FIGO Grade I) |

| 6 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | RCC+AC in the colon |

| 7 | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | |

| 8 | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | |

| 9 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 10 | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | |

| 11 | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | AC in the rectum |

| 12 | − | + | + | + | − | − | Not evaluated | |

| 13 | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | |

| 14 | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | |

| 15 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 16 | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| 17 | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| 18 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | OSC |

| 19 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

F: female; M: male; SA: serrated adenoma; SP: serrated polyp; SSA: sessile serrated adenoma; HP: hyperplastic polyp; LGD: low-grade dysplasia; HGD: high-grade dysplasia; MC: mucinous cystadenoma; SRC: signet ring cell; LGMN: low-grade mucinous neoplasm; EAC: endometrioid adenocarcinoma; LAMN: low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm; RCC: renal cell carcinoma; MAC: mucinous adenocarcinoma; OSC: ovarian serous carcinoma; NET: neuroendocrine tumor; AC: adenocarcinoma

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient age, histomorphological findings, and first and last diagnoses. These were reported as mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, percent, and frequency. Statistical analyses were performed using the NCSS 10 (2015) (NCSS LLC, Kaysville, UT, USA).

RESULTS

In the present study, 19 cases were diagnosed with appendiceal mucinous neoplasms by histomorphological and architectural findings. The incidence of appendiceal mucinous neoplasm was 1.4% in appendiceal tumors diagnosed from June 2011 to December 2016 at our hospital. The patients were re-examined using the updated counterparts of the previous diagnoses according to the Delphi and the AJCC manual. There were fewer groups in the previous classification systems, and the categories were not defined. After the WHO 2010 classification, there were no classification systems to identify appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. The modified Delphi recognized a persistent lack of uniform diagnostic terminology for appendiceal mucinous neoplasm.

The most common symptom was right lower quadrant pain. The median age of the cases was 60±15 (30–84) years. There was a preponderance of females (female-to-male (F/M) ratio: 15/4). On macroscopic examination, 14 (73%) out of the 19 cases had dilated appendiceal lumen, with a mean diameter of 2 cm. None of these cases had appendiceal rupture. Five cases had a history of accompanying extra-appendiceal tumors (serous ovarian carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, carcinoid tumor, or rectal adenocarcinoma) because these appendiceal tumors were found incidentally. Of the five cases, three had been diagnosed with LAMN, and two were diagnosed with serrated polyp. The mean follow-up time was 32 months, and none of the cases were reported to have recurrence. Only one patient died due to additional diseases.

Microscopic examinations of these cases were conducted according to the Delphi and the AJCC manual.

On re-evaluation, six cases were diagnosed with serrated polyp. While five of these cases did not require a change in classification, one previously diagnosed with hyperplastic mucosal was changed to the serrated polyp group according to the new classifications. One case showed high-grade dysplasia focally. The muscularis mucosa layer was intact (Figure 1–3). Three cases initially diagnosed with mucocele were evaluated and re-diagnosed with LAMN. Cytologic atypia, loss of the muscularis mucosa layer, submucosal fibrosis, hyalinization, presence of atrophy in the lymphoid tissue, and presence of acellular mucin inside the appendiceal wall were the histological findings leading to a correct diagnosis. While 6 (21%) cases did not show a change in classification, 1 (5%) case initially diagnosed with sessile serrated adenoma and 1 (5%) case initially diagnosed with mucinous cystadenoma were re-evaluated and diagnosed with LAMNs. The reason is that these cases were diagnosed in recent years using the Delphi, and the diagnostic criteria were clearly identified with this classification system. There were 11 cases in the LAMN group. Findings included low-grade atypia in the epithelium (11 cases), loss of the muscularis mucosa layer (9 cases), submucosal fibrosis (11 cases), presence of acellular mucin inside the appendiceal wall (11 cases) (Figures 4, 5), appendiceal rupture (0 case), undulating or stratified epithelial growth (5 cases), lymphoid tissue atrophy (8 cases), and pushing invasion (1 case) (Figure 6, 7). In addition, the muscular layer was usually fibrotic and hyalinated (12 cases). Ten cases were diagnosed with Tis (in situ) with the AJCC manual because of muscularis propria layer intactness. Only one case was diagnosed with T4a with the AJCC manual because of acellular mucinous deposits on the visceral peritoneal surface. Two cases who showed infiltrative invasion and architectural complexity with desmoplasia were diagnosed with well-differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma (Figure 8–10). In the first evaluation, these two cases were diagnosed with mucinous adenocarcinoma. One case with LAMN and two cases with mucinous adenocarcinoma showed mucin on the serosal surface, and none of the 19 cases showed surgical border positivity (Table 3a, 3b).

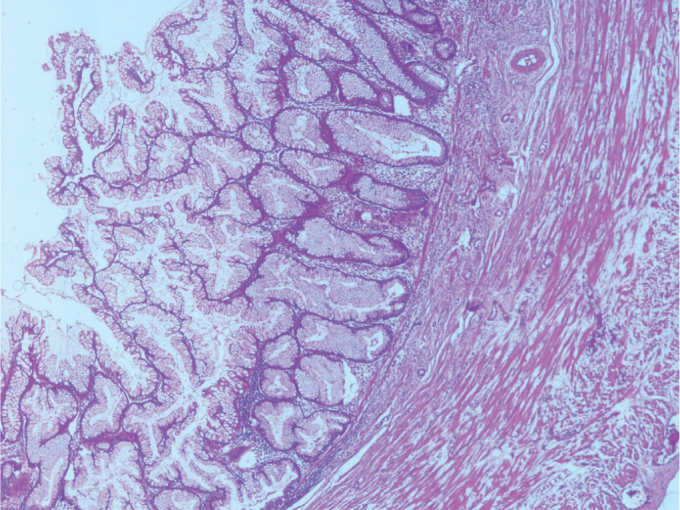

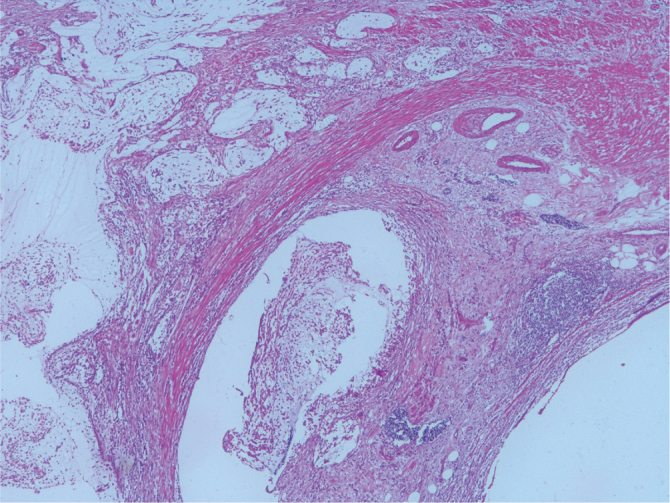

Figure 1.

Serrated polyp without dysplasia resembling colorectal sessile serrated polyp that showing prominent serration at the top of the crypts. Muscularis mucosa is intact (H&E, ×40 magnification)

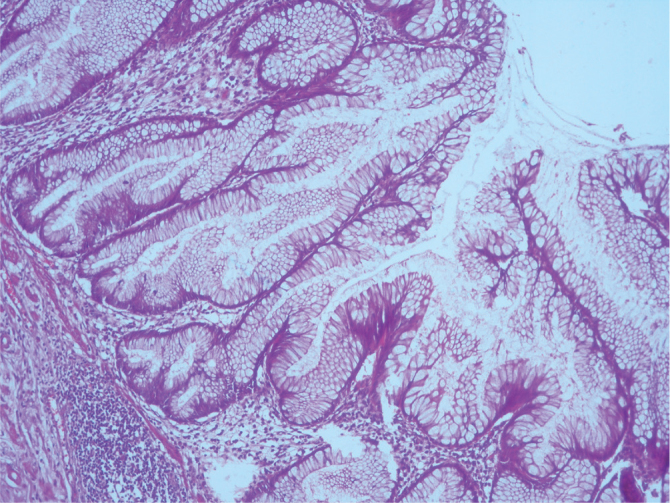

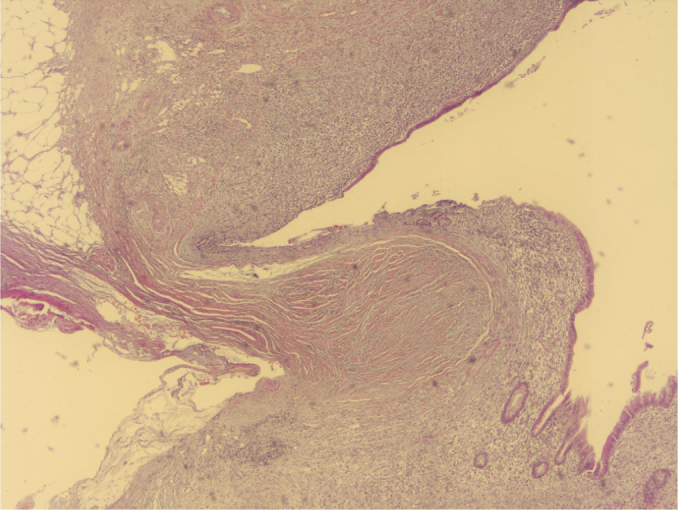

Figure 2.

Serrated polyp showing crypt dilatation and horizontal shaped crypts. (H&E, ×100 magnification)

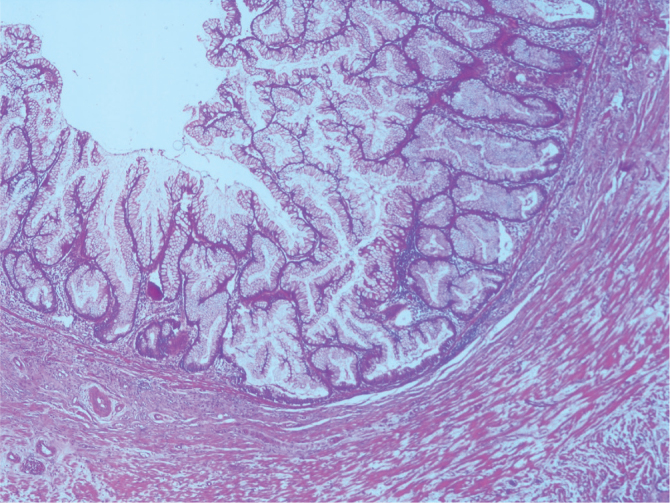

Figure 3.

Mucosa with serrated features. The basal portion of the crypts are branched and appear flask or boot-shaped. Note that the muscularis mucosa is intact (H&E, ×40 magnification)

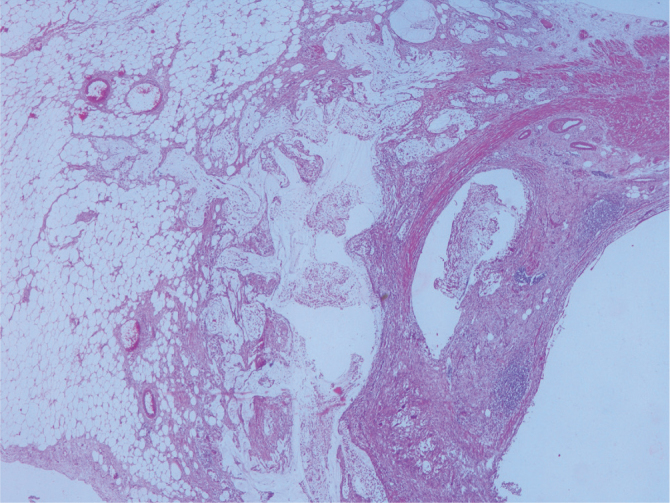

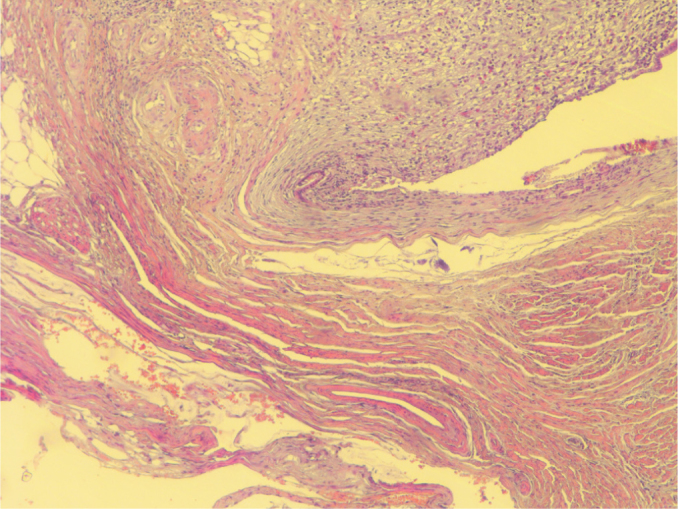

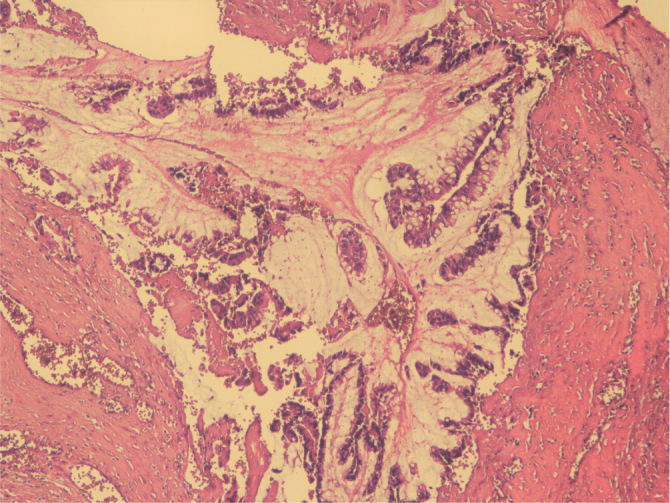

Figure 4.

Some LAMNs are associated with dissecting mucin within the wall and appendiceal subserosa or mesoappendix (H&E, ×20 magnification)

Figure 5.

Presence of acellular mucin inside the appendiceal wall in LAMN (H&E, ×40 magnification)

Figure 6.

LAMNs frequently demonstrate a “pushing” pattern of growth into the wall of the appendix (H&E, ×40 magnification)

Figure 7.

Pushing invasion in LAMN (H&E, ×40 magnification)

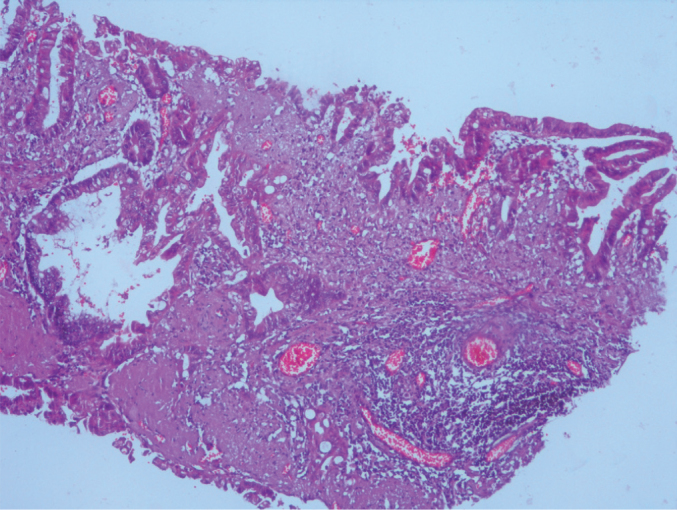

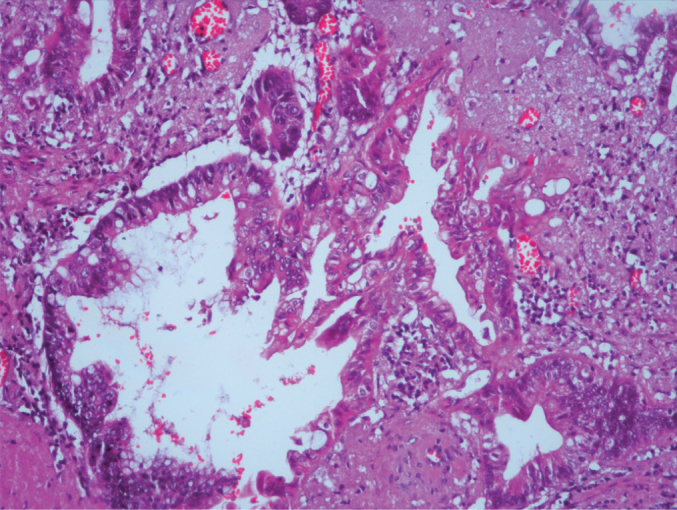

Figure 8.

Infiltrative invasion. Architectural complexity in mucinous adenocarcinoma (H&E, ×100 magnification)

Figure 9.

Architectural complexity in mucinous adenocarcinoma (H&E, ×200 magnification)

Figure 10.

Small dissecting pools of mucin containing nests, glands, or single neoplastic cells (H&E, ×100 magnification)

DISCUSSION

Appendiceal mucocele was first described in 1842 by Rokitansky (12). The classification of appendiceal mucinous neoplasm constitutes a very broad diagnostic spectrum ranging from adenoma to mucinous adenocarcinoma (2). For this reason, there has been a need for the classifications regarding appendiceal mucinous neoplasms to be re-examined. Thus, in the present study, considering the literature, historical scientific advances, and changes in the classifications, 19 cases previously diagnosed with appendiceal mucinous neoplasm were re-evaluated.

The incidence of appendiceal tumors was 0.5%-2%. These tumors did not have typical clinical presentations, were often asymptomatic, and could be diagnosed incidentally during imaging studies (12). The most common symptoms were right lower quadrant pain (27%), palpable abdominal mass (16%), weight loss (10%), and change in bowel habits (5%). A majority (61%) of our cases presented with abdominal pain, whereas others were detected incidentally. The mean age of these cases was 60±15 (30–84) years. There was a preponderance of females, which is consistent with the literature (F/M: 7/2) (7,13). On macroscopic examination, 14 (73%) out of the 19 cases had dilated appendiceal lumen with a mean diameter of 2 cm. Macroscopic findings were consistent with the literature. None of these cases exhibited appendiceal rupture.

On re-evaluation, six cases were diagnosed with serrated polyp. While five of these cases did not require a change in classification, one previously diagnosed with hyperplastic mucosal was changed to the serrated polyp group according to the new classification. Four cases initially diagnosed with mucocele, mucinous cystadenoma, and sessile serrated adenoma were re-evaluated and diagnosed with LAMNs. This is because the cases were diagnosed prior to 2016; they were re-evaluated using the Delphi, and the identifying diagnostic criteria were correctly and clearly identified with this classification system. There were 11 cases in the LAMN group. Findings included low-grade atypia in the epithelium (11 cases), loss of the muscularis mucosa layer (9 cases), submucosal fibrosis (11 cases), presence of acellular mucin inside the appendiceal wall (11 cases), appendiceal rupture (0 case), undulating or stratified epithelial growth (5 cases), lymphoid tissue atrophy (8 cases), and pushing invasion (1 case). In addition, the muscular layer was usually fibrotic and hyalinated (12 cases). The most important consideration in the diagnosis of LAMN is the evaluation of the presence of acellular mucin inside the wall and pushing invasion. Pushing invasion is where the tissue is pushed and expanded without causing destruction. These cases do not show desmoplasia, single cell invasion, or tumor budding. Two cases who presented with infiltrative invasion, architectural complexity with desmoplasia, and mucinous epithelium were diagnosed with well-differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma. In the initial evaluation, these two cases had been diagnosed with mucinous adenocarcinoma, and there was no diagnosis change in these cases.

Prognostic parameters include the presence of symptoms, perforation, operation type, increased tumor marker levels, and presence of a tumor at surgical borders for appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (1,14).

Visualization of the appendix and an increase of >15 mm in its size suggested specific appendiceal mucocele with 83% sensitivity and 92% specificity. Preoperative imaging studies were performed in eight of our cases, and these had similar findings. The major criterion for discrimination between appendicitis and appendiceal mucinous neoplasms is a wall thickness >6 mm. The clinical signs of appendicitis and the clinical picture of mucin leakage following mucinous neoplasm rupture often cannot be distinguished from each other. Since appendiceal mucinous neoplasms and pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) are often diagnosed after the age of 50 years, computed tomography/magnetic resonance imagining studies are recommended for patients over this age presenting with signs of appendicitis (12).

Several tumor markers, including CEA, CA 19-9, and CA 125, have been reported to have diagnostic and prognostic significance in cases with mucinous neoplasms. A previous study stated that these markers can also be used in postoperative follow-up (12). Elevated CEA and CA 19-9 levels may indicate recurrence (15). In 2013, McFarlane et al. (16) described two rare cases of elevated CEA levels in mucinous cystadenoma. Only eight of our cases were tested for serum levels of the tumor markers CA 125, CEA, CA 19-9, and CA 15-3. However, they were not significant in terms of follow-up, treatment, prognosis, and recurrence.

There is no standard treatment protocol for cases with surgical border positivity. Arnason et al. (13) examined proximal surgical border in their LAMN cases. They treated 10 cases with surgical border positivity with only appendectomy and followed up their cases. They did not report recurrence during follow-up. For four cases in which a surgical border positivity hemicolectomy was performed, the surgical specimens did not show residual neoplastic epithelium (13). Our cases were followed up, and no recurrence was detected during the follow-up period. Only one case had surgical border positivity.

Even if LAMNs are spread across the peritoneum, the lymph nodes are generally not affected. Therefore, the role of right hemicolectomy in patients with widespread peritoneal disease is unclear (13). Recent studies have shown that appendectomy alone is curative for benign and grossly intact mucinous neoplasms. Right hemicolectomy is only recommended when there is a risk of ileocecal valve injury due to traumatic manipulation or protrusion of the tumor toward the cecal lumen. In order to determine whether right hemicolectomy is necessary, Gonzalez-Moreno and Sugarbaker recommended the sentinel lymph node approach, consisting of frozen examination of the lymph nodes found along the appendiceal artery inside the appendiceal mesentery. If there is no metastatic lymph node, right hemicolectomy is not indicated (17). Owing to these uncertainties regarding treatment approaches, one of our cases underwent right hemicolectomy due to a high risk of malignancy. Appendectomy alone was considered sufficient in 18 of our 19 cases, and they did not show recurrence during the follow-up period.

The most significant complication in appendiceal tumors is the development of PMP, which is an important factor affecting treatment and survival. PMP is the detection of neoplastic epithelium and mucin on the visceral and parietal peritoneum. It is not a histological term and is not used in the staging of appendiceal neoplasms. It represents the clinical syndrome of an appendiceal neoplasm with diffuse mucinous peritoneal involvement (11). It has been reported to cause death in 40% of patients 10 years after the initial diagnosis. Cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy have been recommended for treatment (18). PMP was not reported in our cases.

Appendiceal mucinous tumors have shown different epithelial atypia, and the architectural structure and presence of extra-appendiceal mucin and neoplastic epithelium lead to changes in survival rate. For these reasons, this tumor classification had to be examined as a spectrum. In recent years, several researchers interested in this topic have used various classifications and examined their molecular patterns. We aimed to conduct a compendious evaluation of these classifications used throughout history. The literature was searched from 1940 to 2018 for published cases of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms.

In 1940, McDonald and Woodruff divided mucinous appendiceal tumors into two groups: benign mucocele and cystadenocarcinoma (5). Carr et al. (10) retrospectively examined 184 cases of mucocele, hyperplastic polyp, adenoma, cystadenoma, carcinoma, cystadenocarcinoma, and mucinous tumors with indeterminate malignancy potential. The study is important as it includes large series and clinicopathological examinations.

Misdraji et al. (7) examined 107 cases diagnosed between 1950 and 2000. Their findings indicated that 88 cases have LAMNs, 16 cases have mucinous adenocarcinoma, and 3 are categorized in the indeterminate class.

In 2009, Pai et al. (6) examined 106 cases with appendiceal mucinous neoplasm. The four groups included mucinous adenoma, low recurrence risk low-grade mucinous neoplasm, high recurrence risk low-grade mucinous neoplasm, and mucinous adenocarcinoma. In this classification, there was a difference between high-risk low-grade appendiceal tumors and mucinous adenocarcinoma in terms of survival. The most important information that should be given to the clinician is whether there are extra-appendiceal mucin and neoplastic epithelium and the degree of cytologic atypia in the epithelium (6,19).

In 2016, Carr et al. (8) used the modified Delphi during re-evaluation of appendiceal neoplasms. They were categorized into eight groups: serrated polyp, LAMN, HAMN, mucinous adenocarcinoma, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell, signet ring cell adenocarcinoma, and adenocarcinoma. According to the modified Delphi protocol, the term cystadenoma is no longer used. This is because mucinous adenoma implies that there is no potential for peritoneal dissemination, which is not true of LAMN (20). Instead, adenoma with low- or high-grade dysplasia or serrated polyp displaying serrated features, as in colonic sessile serrated adenoma, is the new term. The presence of low-grade cytologic atypia, together with one of the following, is defined as LAMN: loss of the muscularis mucosa layer, submucosal fibrosis, pushing invasion, dissection with acellular mucin in the wall, undulating or stratified epithelial growth, appendiceal rupture, and presence of extra-appendiceal mucin and/or cells. Mucinous neoplasms that display similar structural features to LAMN, lack of infiltrative invasion, but high-grade atypia cytologically are also determined as HAMN. The term mucinous adenocarcinoma, however, is used for mucinous tumors displaying infiltrative invasion. Neoplasms that include signet ring cells with a ratio of <50% are determined as signet ring cell poorly differentiated (mucinous) adenocarcinoma; those with signet ring cells with a ratio of >50% are categorized as signet ring cell (mucinous) carcinoma. Non-mucinous adenocarcinomas that are similar to the traditional colorectal type are classified as adenocarcinoma (8). When diagnosing adenocarcinoma, the presence of tumor budding, discohesive cells and small glandular structures, and desmoplasia were taken into consideration. Desmoplastic response is characterized by proteoglycan-rich extracellular matrix and vesicular nuclei intertwined with active fibroblast/myoblasts. This classification system is less effective than the previous classification systems. This system, which separates neoplasms into detailed groups, enables appendiceal mucinous neoplasms for the pathologist.

Eze et al. (21) classified appendiceal mucinous neoplasms as mucinous adenoma low-risk LAMN, high-risk LAMN, and mucinous adenocarcinoma. Their study classified LAMN into two groups for risk assessment for PMP. This category is different from the modified Delphi categories.

A staging system specifically for LAMN, which shows the biologic behavior of these tumors and gives prognostic information, has been developed by the AJCC (22). Umetsu et al. (21) examined appendiceal neoplasms, and in 15% of these cases, acellular mucin was present beyond the muscularis propria, but the neoplastic epithelium was confined to the muscularis propria. None of these patients had recurrent disease at follow-up.

The AJCC has made significant changes to the staging of LAMN. LAMNs that invade the lamina propria, with or without muscularis mucosa, but not through the muscularis propria, are assigned to the newly created Tis LAMN category. Tumors (including acellular mucin) can involve the muscularis propria. The categories T1 and T2 are not used for LAMN classification.

Involvement of the subserosa is assigned to the T3 category. Tumors (including acellular mucin) that involve the serosal surface or directly invade organs are assigned to the T4 category. T4a tumors are characterized by localized involvement of the serosal surface by acellular mucin or cellular tumor. Category T4b tumors directly invade other organs (11) (Table 4).

Table 4.

AJCC 8th edition (11) staging of LAMN

| AJCC 8th edition stage of LAMN | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition of primary tumor (T) | pTis | LAMN that invades or pushes into the muscularis propria |

| T3 | LAMN with acellular mucin or neoplastic mucinous epithelium extending into the subserosa | |

| T4a | LAMN that invades the serosal surface by acellular mucin or cellular tumor | |

| T4b | Tumor invades other organs or invades other colorectal segments directly | |

| Definition of regional lymph node (N) | N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis, presence of acellular mucin within the lymph node or tumor deposit |

| N1 | 1–3 lymph node positive | |

| N2 | ≥4 lymph node positive | |

| Distal metastasis (M) | M1a | Intraperitoneal acellular mucin |

| M1b | Intraperitoneal metastasis containing tumor cells | |

| M1c | Non-peritoneal metastasis |

For LAMNs, the depth of the appendiceal wall involvement is not a significant risk factor for recurrence (9).

CONCLUSION

The aim of the present study was to establish a common consensus and common terminology for clinicians and pathologists. Considering the 2016 Modified Delphi Consensus Protocol and the Eighth Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, there are many changes and innovations in the classification, evaluation, and treatment of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. These classification systems have facilitated the compatibility and communication between clinicians and pathologists and have guided clinicians on treatment methods.

The present study was evaluated according to certain histological and architectural features in this group. Although clinical findings were consistent with the literature, owing to the small sample size and the retrospective study design, larger-scale studies, including comparative survival analysis and long-term follow-up, are necessary. Prospective studies will be helpful for the improvement of appendiceal mucinous neoplasm treatment and survival rates.

Footnotes

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - E.K., Ö.G.; Design - N.K., Ö.G., A.S.İ.; Supervision - N.E., M.C., S.B.; Resources - S.B., N.K.; Materials - E.K., M.C.; Data Collection and/or Processing - N.K., D.G., S.B., Ö.G.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - E.K., M.C., A.S.İ.; Literature Search - N.E., M.C., D.G.; Writing Manuscript - N.K., Ö.G.; Critical Review - N.E., D.G., S.B., A.S.İ.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fournier K, Rafeeq S, Taggart M, et al. Low Grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm of Uncertain Malignant Potential (LAMN-UMP): Prognostic Factors and Implications for Treatment and Follow-up. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;1:187–93. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5588-2. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5588-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tirumani SH, Fraser-Hill, Auer R, et al. Mucinous Neoplasms of the Appendix: A Current Comprehensive Clinicopathologic and Imaging Review. Cancer Imaging. 2013;13:14–25. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2013.0003. https://doi.org/10.1102/1470-7330.2013.0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Odze RD, Goldblum JR. Surgical Pathology of the GI Tract, Liver, Biliary Tractand Pancreas. 3th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2015. pp. 779–802. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connor SJ, Hanna GB, Frizella FA. Appendicial Tumors: Retrospective Clinicopathologic Analysis of Appendicial Tumors from 7970 Appendectomies. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:75–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02236899. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02236899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodruff R, McDonald JR. Benign and malignant cystic tumors of the appendix. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1940;71:750–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pai RK, Beck AH, Norton JA, Longacre TA. Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasms Clinicopathologic Study of 116 Cases With Analysis of Factors Predicting Recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1425–39. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181af6067. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181af6067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misdraji J, Yantiss RK, Graeme-Cook FM, et al. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a clinicopathologic analysis of 107 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1089–103. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200308000-00006. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-200308000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carr NJ, Cecil TD, Mohamed F, et al. Peritoneal Surface OncologyGroup International A Consensus for Classification and Pathologic Reporting of Pseudomyxoma Peritonei and Associated Appendiceal Neoplasia: The Results of the Peritoneal Surface OncologyGroup International (PSOGI) Modified Delphi Process. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:14–26. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr NJ, Sobin LH. Adenocarcinoma of the appendix. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, et al., editors. World Health Organisation Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2010. pp. 122–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr NJ, McCarthy WF, Sobin LH, et al. Epithelial Noncarcinoid Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions of the Appendix. Cancer. 1995;75:757–68. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950201)75:3<757::aid-cncr2820750303>3.0.co;2-f. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19950201)75:3<757::AID-CNCR2820750303>3.0.CO;2-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Overman MJ, Asare EA, Compton CC, et al. Appendix-Carcinoma. In: Amin MB, editor. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th edition. Chicago: 2017. pp. 237–81. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asenov Y, Korukov B, Penkov N, et al. Appendiceal mucocele -Case Report and Review of the Literature. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2015;110:565–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnason T, Kamionek M, Yang M, et al. Significance of proximalmargin involvement in low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:518–21. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2014-0246-OA. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2014-0246-OA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin R, Chai YJ, Park JW, et al. Ultimate Clinical Outcomes of Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm of Uncertain Malignant Potential. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:974–82. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5657-6. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5657-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Padmanaban V, Morano WF, Gleeson E, et al. Incidentally discovered low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm: a precursor to pseudomyxoma peritonei. Clin Case Rep. 2016;4:1112–6. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.694. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McFarlane ME, Plummer JM, Bonadie K. Mucinous cystadenoma of the appendix presenting with an elevated carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA): Report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Report. 2013;4:886–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.07.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Moreno S, Sugarbaker PH. Radical appendectomy as an alternative to right colon resection in patients with epithelial appendiceal neoplasms. Surg Oncol. 2017;26:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2017.01.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chua TC, Moran BJ, Sugarbaker PH, et al. Early and long-term outcome data of patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from appendiceal origin treated by a strategy of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2449–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7166. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2012.30.4_suppl.532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rouzbahman M, Chetty R. Mucinous tumours of appendix and ovary: an overview and evaluation of current practice. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:193–7. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2013-202023. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2013-202023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valasek MA, Pai RK. An update on the diagnosis, grading and staging of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Adv Anat Pathol. 2018;25:38–60. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eze O, Jones R, Montgomery E. A practical approach for diagnosis of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Diagnostic Histopathology. 2017;23:530–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpdhp.2017.11.004 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Umetsu SE, Shafizadeh N, Kakar S. Grading and staging mucinous neoplasms of the appendix: a case series and review of the literature. Human Pathol. 2017;69:81–9. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.09.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2017.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]