Abstract

China launched a new rural pension scheme (hereafter NRPS) for rural residents in 2009, now covering almost all counties with over 400 million people enrolled. This implementation of the largest social pension program in the world offers a unique setting for studying the economics of intergenerational relationships during development, given the rapidity of China’s population aging, traditions of filial piety and co-residence, decreasing number of children, and dearth of formal social security, at a relatively low income level. We draw on rich household surveys from two provinces at distinct development stages – impoverished Guizhou and relatively well-off Shandong – to better understand heterogeneity in the impact of pension benefits. Employing a fuzzy regression discontinuity design, we find that around the pension eligibility age cut-off, the NRPS significantly reduces intergenerational co-residence, especially between elderly parents and their adults sons; promotes pensioners’ healthcare service consumption; and weakens (but does not supplant) non-pecuniary and pecuniary transfers across three generations. These effects are much larger in less developed Guizhou province.

Keywords: Social pensions, intergenerational relationships, regional comparisons, co-residence, old-age care, service consumption, transfers

JEL: H55, I18, J14, R28

1. Introduction

The implementation of social pensions has far-reaching implications for the well-being of residents in developing countries2 in which families have been the primary informal institution for life-cycle savings and support. Raising elderly persons’ own income, social pensions have the potential to bring considerable benefits to the elderly and their extended families.3 For example, data across multiple countries highlights that conclusions about optimal policies to support living standards depend to a large extent on whether the analyst takes account of private transfers and the burdens of caregiving placed on the family in developing countries, not only public finances (Lee, Mason, and members of the NTA Network 2014). Establishing sustainable social pension systems in less developed countries is urgent as the growth rate of the senior population in these countries substantially exceeds that of developed countries (Edmonds et al. 2005).

Similar to many other developing countries, China’s population is ageing rapidly. By 2050, over 25.6 percent of China’s population is expected to be over age 65.4 Moreover, the implementation of stringent family planning policies during the last three decades has contributed to a dramatic increase in the elderly dependency ratio at a relatively low income level, which further intensifies the pressure on China’s now shrinking working-age population to take care of their elderly parents.

This paper aims to contribute to the growing literature on the impact of social pensions in developing countries, especially for households in poor rural areas compared to their more affluent counterparts. We ask whether more income for elderly parents facilitates more independent living and less co-residence with adult children; whether parents report better access to crucial services such as medical care, substituting this service consumption in part for children’s time involved in instrumental support to them; and to what extent the introduction of pension income changes pecuniary and non-pecuniary transfers between elderly parents, their adult children, and grandchildren. We answer these questions by examining the impact of pension payments from a relatively new rural pension program as implemented in two contrasting rural areas in China.

There has been mixed evidence on changes in family composition as a result of pension receipt in developing country contexts. Edmonds et al. (2005) and Hamoudi and Thomas (2005) provide evidence on the selection of adults who co-reside with older adults when they become eligible for the pension. However, both Edmonds et al. (2005) and Jensen (2004) find no evidence that pension income leads to a significant increase in propensity to live independently or that the average size of the household responds to pension income.

Meanwhile, there has also been some evidence on pension crowding out private transfers (Jensen 2004; Maitra and Ray 2003) but little evidence on consumption of medical and other services as a result of pension receipt (see Chen and Park 2016; and Cheng, Liu, Zhang and Zhao 2016).

The new rural pension scheme (NRPS) in China provides an opportunity to examine these questions in the setting of a modest pension payment, compared to the generous pension program in South Africa that pays twice the average income (Lund 2007). Moreover, considering the large disparities between rural and urban areas, across regions, and across age cohorts in China, the NRPS provides a distinctive analytic opportunity to study heterogeneous impacts of pension income. The elderly rural residents living in China’s less developed regions are particularly disadvantaged. In 2010, the poverty rate for rural people aged 60 and above was as high as 22.3 percent, compared to 7.8 percent for the rural population in China as a whole (Cai et al. 2012).

This paper has two main advantages over the large literature that identifies the impact of pensions on households and intergenerational relationships, and the smaller but growing literature on NRPS. First, we draw on two detailed household surveys, including onefrom one of the poorest areas of rural China (Guizhou province); an overwhelmingly high proportion of rural residents in Guizhou are below the USD 1.25 international poverty line. We apply to the Guizhou survey data the same analytic strategy as applied to survey data from Shandong province (Eggleston, Sun, and Zhan 2016, hereafter ESZ), focusing on comparing results to those we estimated for Shandong and those estimated by others using alternative datasets such as the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey, CHARLS (Chen and Park 2016) and the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey, CLHLS (Cheng, Liu, Zhang and Zhao 2016). The Guizhou data allows a stronger empirical test than previously possible of our hypothesis that an increase in the income of elderly parents will relax the credit constraint for households, with the effects most apparent among the most credit-constrained households. This relaxation of credit constraints makes services more affordable and enables pensioners to substitute purchased services for instrumental support provided by their adult children.

Second, we use these two rich household surveys to track each adult child’s living arrangements and demographic information regardless of whether that adult child is counted as a household member (or is currently living under the same roof with the parents). Thus, we can generate datasets of pensioners’ and non-pensioners’ adult children without introducing complications of endogenous household formation. This is important, especially for studying impacts in poor rural areas, since living space may be considered a normal good and additional income may be allocated toward independent living with more privacy for each generation when baseline living arrangements are more crowded.

However, since the co-residence decision of household members is largely affected by life-cycle patterns and cohort heterogeneity, empirical identification strategies using pension receipt alone may confound the effect of pensions with that of cohort heterogeneity. We apply a Fuzzy RD design in this paper to overcome this issue. Residents are eligible for the old-age pension starting from age 60. This age is not tightly linked to labor force participation in rural China, since older adults usually remain active in agricultural production well into their 60s in rural areas (Cai et al. 2012). Indeed, in a recent analysis using CHARLS data, Ning et al. (2016) found no evidence that pension receipt from the NRPS program induces withdrawal from labor force participation.

Our fuzzy RD design has several advantages over other methods of identification and has been applied to multiple different settings (Edmonds et al. 2005; Card et al. 2009; Miller et al. 2013). For example, evidence suggests households eligible for pension payment are systematically different from ineligible households. Therefore, the estimations on pension impact using survey data likely suffer from omitted variable bias. Controlling for time-invariant individual factors through fixed effect models requires very specific assumptions about the nature of unobserved factors and their persistence over time (Ardington et al. 2009). Moreover, individual fixed effect models cannot eliminate biases when individuals who dropped out between waves of a survey are different from others.

Assuming that household structure is continuous with respect to the age of the elderly, our research design disentangles the effect of pensions from other age-related factors shaping intergenerational relationships. In addition to the intent to treat (ITT) type of analyses that make use of discontinuity in age eligibility, such as the reduced form RD estimations in Edmonds et al. (2005), we take advantage of a discontinuity in actual pension receipt induced by age eligibility. Our Fuzzy RD approach adjusts the attenuated measure of the true impact when take-up of the pension is incomplete or does not coincide exactly with age eligibility (Edmonds et al. 2005). Compared to studies using age eligibility as the instrumental variable, such as Hamoudi and Thomas (2005) and Posel et al. (2006), our RD design is more flexible for choosing functional forms, optimal bandwidths, and a set of narrow age cohorts around the age eligibility cut-off, which gives some reassurance that the results are robust. Compared to the diff-in-diff-in-diff (DDD) approach in Jensen (2004), our RD design does not assume that living arrangements between the groups receiving pensions or not have to follow the same trend in the absence of the pension.

We focus on families with living adult children, because adult children represent the primary source of support for middle-aged and elderly individuals in rural China and therefore are the other family members most likely to be impacted by their parents’ pension benefits. When studying living arrangements, we focus on the subsample of adult sons in both surveys, since the traditional system of co-residence with adult sons (and relatively high baseline rate of co-residence with sons) implies that household decisions about co-residence will be most evident when studying this subset of rural elderly.

Our results utilizing two longitudinal household surveys from Guizhou and Shandong provide several key findings. First, RD reveals a perceptible reduction in adult sons’ co-residence with parents around the cut-off age for pension receipt, with a larger and more significant effect for Guizhou than for Shandong. Similarly, there is a more salient decline in co-residence between grandchildren and grandparents for Guizhou than for Shandong. Thus, pension income does appear to relax credit constraints most significantly for the poorer rural area, and is associated with purchase of greater living space (and privacy) across three generations. Second, we reinforce the earlier finding that the elderly parents themselves do benefit from the pension income, as proxied here by greater confidence in consumption of medical services. Even though health insurance coverage shows no significant changes after the pension eligibility threshold, pension receipt is associated with greater healthcare consumption among pensioners, or greater perceived confidence in consuming medical services when needed, in both provinces. Third, non-pecuniary transfers between elderly parents and adult children, such as being assisted by children when ill, appear to be significantly reduced by NRPS, whereas pecuniary intergenerational transfers are only slightly weakened.

The RD design survives a series of key placebo tests and robustness checks, including verifying no jumps of outcomes at age cut-offs other than 60, no discrete changes in baseline characteristics and predetermined outcomes at the age 60 cut-off, no discontinuities in the density of the running variable, and no evidence of confounding policy discontinuities at age 60. Furthermore, results are robust to various bandwidths, bandwidth selection procedures, and polynomial specifications.

Though our surveys in Guizhou and Shandong are not nationally representative, we believe the results are of broad interest because the two surveyed regions in distinct development stages yield something akin to the lower and upper bounds of the NRPS pension impact on intergenerational relationships in rural China. The unusually detailed household information in the surveys enables us to link parents with adult children who have left home and thus shed light on multiple aspects of intergenerational living arrangements and transfers. In addition to our two regional surveys, we follow ESZ in using the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) national baseline sample to test the impact of age eligibility on pension receipt.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the new rural pension program in China, its implementation in Guizhou and Shandong, and some key hypotheses about the potential impact of NRPS on the intergenerational relationships we study. Section 3 describes the two surveys and our identification strategy. Section 4 presents results, discusses interpretations, and conducts a series of robust checks. Section 5 offers concluding remarks.

2. Institutional Background and Mechanisms

2.1 The New Rural Pension Reform and its implementation in Guizhou and Shandong Provinces

The rural elderly represent one of the lowest income groups in China. According to the CHARLS baseline national survey in 2011–12, the poverty rate based only on the income of the rural elderly and their spouses (including pensions) reaches 65.1 percent (CHARLS Team 2013). Traditionally, support from children and other family members plays a key role in reducing consumption poverty.

In September 2009, China launched a pension program for rural residents, the New Rural Pension Scheme (NRPS). Beginning with 320 pilot counties, the NRPS covered 838 counties by 2010 and reached almost all 2853 counties by 2012. The NRPS aims at universal coverage of rural residents in China. The number of pension contributors, beneficiaries, fund expenses and the balance have been rising sharply. By the end of 2014, more than 400 million Chinese have contributed to the NRPS, while more than 100 million have become pension beneficiaries. The pension fund balance and fund expenses have reached 385 billion CNY and 159 billion CNY, respectively (Figure A1).

The pension fund consists of three parts: an individual premium, a local government subsidy, and a central government subsidy. According to the guidance released by the State Council of China, individuals are free to choose from a menu of options that includes five basic categories of individual premium: 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 CNY per year per person. Local governments may introduce more categories to adjust for higher or increasing costs of living. Among those who voluntarily enroll, 100 CNY has proven to be the most popular premium choice (Lei et al. 2013). The local government subsidy must be no less than 30 CNY per person per year. The higher the individual premium one chooses to pay, the greater the subsidy match embodied in the local government premium contribution. The individual premium and the local government subsidy form the NRPS individual account. In addition, a basic pension benefit – 55 CNY per month per person in Guizhou, 60 CNY per month per person in Shandong, but as much as 310 CNY per month per person in a few rich provinces and municipalities – is available to all residents, financed by the central government. Pensioners receive payment from both the individual account and the basic pension benefit.

All rural residents aged 16 or older who are not enrolled in urban basic pension programs can enroll in NRPS voluntarily. Participants below age 45 are required to contribute at least 15 years to become eligible for pension benefits upon reaching age 60. However, according to the State Council, there is no required minimum number of years of contribution for those between 45 and 60 years old; these individuals are simply encouraged to contribute more to meet the shortfall in contributions to their own account over their remaining years before reaching age 60. According to several sources (including our Guizhou survey and two nationally representative samples – the China Center for Agricultural Policy survey and the China Family Panel Study), most people aged 55–60 choose one of two paths: either they wait until age 60 to receive the free basic pension benefit offered by the central government, without any contributions to an individual account; alternatively, they often follow the path preferred by the younger cohorts noted above, choosing to pay the lowest individual premium (100 CNY) (Chen and Wang 2016).

For any rural residents already aged 60 or older at the time of NRPS implementation in their locality, pension benefits are non-contributory. In other words, they are not required to make any contributions to the NRPS system to become eligible for the basic pension benefit; nor are they required to have cumulative work histories, or to show that members of their extended family have paid voluntary premiums.5 However, these beneficiaries aged 60 or older do not have individual accounts, as the NRPS was only rolled out recently.

Considering that the elderly earn less than the young generation and that the pension payment is targeted on the elderly, the pension payment should exert a larger impact on older persons than other family members.6 Moreover, these NRPS impacts may differ substantially across China’s vastly differing regions, such as between impoverished Guizhou province and comparatively rich Shandong province. We expect heterogeneous impacts for several reasons. First, the NRPS “windfall income” represents a larger relative relaxation of the household budget constraint for the poor with little formal old-age support. While the benefit accounts for a small proportion of income in developed regions (e.g. Shandong province, where pension payments are equivalent to 10 percent of average income per capita), it represents a much larger relative increase in resources in less developed regions such as Guizhou province (where pension payments are equivalent to 30 percent of average income per capita). Second, the lower fertility rate in more developed regions may restrict observation of elderly parents’ propensity to substitute away from reliance on adult children through co-residence, instrumental support, and other non-pecuniary transfers. For example, consider the older adults aged 55–65 in our two surveys. In the Guizhou sample, they have on average more than 3.5 children, whereas in the Shandong sample 23.4 percent of these parents only have a single child. Social norms still dictate that sons are more responsible to help parents than daughters are, but over 50 percent of parents in the Shandong survey only have one son, compared to on average 2 sons in the Guizhou survey.

Both the surveyed areas in Guizhou and Shandong have income per capita close to the average of their own provinces. Like most of the rural areas in China, elderly persons in Guizhou and Shandong have very limited options for formal old-age care services or financial support, outside of reliance on family members. In the Guizhou sample, all elderly respondents reside in their own homes, with or without co-residence of adult children. In the Shandong sample, a few villages started to set up community care centers from village collective funds, providing no-rent dormitory-like housing and meals to elderly village residents (see discussion in Liu, Eggleston and Min 2016). However, the institutional care in the form of these rural community care centers is not well accepted due to the traditional norms of co-residence. Over half of the elderly persons in the Shandong sample believe living with children is the most ideal arrangement. Moreover, most people around the pension eligibility threshold of age 60, i.e. the group of people we rely on in our research design, still work in the fields and do not need institutional settings for long-term care.

2.2 Income and Intergenerational relationships: Potential Pathways

Pension payments directly raise pensioners’ incomes, potentially spurring substitution out of labor force participation in response to pension receipt. Moreover, as people age, their work activities and income gradually decline, and these effects may be difficult to disentangle. An overall positive income shock is necessary to be able to observe the impact of income while controlling for confounding factors. Consistent with the fact that receiving pension payment from the NRPS is not tied to individual employment decisions, we find that tests using our Guizhou survey and Shandong survey, available upon request, reassure that personal income of the elderly (excluding pension benefits) is continuous around the pension eligibility cut-off but discontinuously increases when defined to encompass pension income.

Throughout the developing world, adult children often provide the most important form of old age support for elderly parents, both through pooling of household public goods in co-resident living arrangements and other non-pecuniary support. Pension payments increase elderly parents economic resources, which may promote their economic independence and enable adult children to choose to live in a separate home in the same village or to move further away in pursuit of education or work. The enlarged gap between demand and supply of old-age care services may be filled by emergence of markets for such services (Hoerger et al. 1996).

If we consider living arrangements as a form of consumption (Costa 1997 and 1999), more economic resources to extended families may also explain a falling household public goods consumption (such as companionship) and decisions to live apart. With scarce economic resources, economies of scale may dictate that larger extended families live together to share household public goods, and privacy is less attractive or affordable (Salcedo et al., 2012). More than 80 percent of parents in the Guizhou sample and 50 percent of parents in the Shandong sample co-reside with adult children, respectively. However, the consumption of household public goods at lower cost is linked with the optimal number of family members under one roof. The relaxation of the household credit constraint, through additional income that could have been anticipated but could not be used as collateral for loans, enables family members to choose to live separately and therefore family size to fall (Zimmer and Kwong 2003), rendering public goods sharing less economical. Meanwhile, if the utility function displays more curvature in public than private goods, the increasing purchasing power as a result of pension payment may lead to a higher expenditure share on private goods. In both cases, the benefit from living together is reduced, which promotes our hypothesized effect of changes in co-residence patterns.

Due to the patriarchal residency tradition in rural China, adult sons are more likely than adult daughters to be the children who live with parents and share household public goods; sons and daughters-in-law therefore have traditionally played a more important role in taking care of elderly parents than daughters have. Therefore, we hypothesize that the increase in income of pensioners may reduce co-residence with adult sons by enabling them to substitute service consumption for care directly provided by adult sons (and daughters-in-law), thereby freeing up them to live separately.

While it is possible that adult children may reduce their financial support for elderly parents because of the roll-out of the pension program, a one-to-one crowd out of pecuniary support seems unlikely given the tradition of filial piety and close ties between parents and children. Evidence to date suggests that intra-household transfers have alleviated poverty in old age to a large extent, and that the modest pension benefits in rural China may be unlikely to crowd out the intra-household motives of poverty alleviation. Ultimately the extent of crowd out is an empirical question which we test.

Since the current pension payment is still modest and a large proportion of China’s rural elderly population remain comparatively impoverished, even with anticipation of pension income they face constraints in ability to borrow by saving less or borrowing from others. These hypotheses also will be indirectly tested in the following empirical analysis.

3. Empirical Strategy

3.1 The Guizhou Survey Data

This paper makes use of a rich panel survey of households in Guizhou province. With the help of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and China Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS), we attempted to keep track of all residents in 26 randomly selected villages in a county in Guizhou, one of the poorest provinces in China. With a total population of 402,000, per capita income in the county is above the provincial median but below the provincial mean, suggesting that its income profile is representative of Guizhou province as a whole. Despite double-digit income growth, half of the residents in the 26 villages still live below the international poverty line, and the communities are experiencing worsening income inequality.

Each wave of the Guizhou survey was conducted a few days before the Lunar New Year (January or February) when most migrants return to celebrate the holiday with family members. We also managed to visit each household several times to make sure all family members at home were interviewed individually. In the latest 2011 wave 5189 individuals from 963 households were interviewed. Three waves of the survey (i.e. 2004, 2006 and 2011) are utilized in this analysis.7 Since the NRPS was introduced in Guizhou in 2010, the 2004 and 2006 data are used in placebo tests.8

Subsamples critical to our analysis include the sample of adult sons (N=1016), the sample of parents with adult sons (N=1226), the sample of adult children (N=1741), and the sample of parents with adult children (N=1669). The survey collected rich information on demographics, income and consumption for all household members (including returning migrants and other non-coresident members), their relationships with the household head and living arrangements. At the beginning of each interview, every household was asked by the survey enumerators to show its official household registration record (a.k.a. the Hukou book), which displays accurate official records for all members in the household, whether migrants or not. Besides filling in the family roster based on information from the household registration book, the survey asked each household to recall previous members who permanently moved out and therefore were removed from the household registration book.

Living arrangements were identified from the family roster questionnaire, which records all co-resident and non-coresident members. Co-residence is defined as those living under the same roof and who dine together most of the time. Non-coresident family members include others living in the same village, same town, same county, same province or other provinces. Measures of intergenerational living arrangements were constructed from the perspectives of both adult children and their parents. For adult children, we measure whether they co-reside with parents. For parents, we measure the number of adult sons with whom they co-reside.

3.2 The Shandong Survey Data

This study also makes use of a survey of senior citizens in a county in Shandong, China in July 2012. This survey was conducted under ‘the Health and Health Support of Rural Elderly’ collaborative research project sponsored by the Asia Health Policy Program of the Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center at Stanford University and the Institute for Population and Development Studies at Xi’an Jiaotong University, China (ESZ). We first categorized all villages into three strati according to GDP per capita in 2010. In the first stage, within each stratus, 4 villages and 1 community care center were randomly selected and the village heads were interviewed to assess basic village characteristics and the roll-out of the pension program.9 Village heads also provided a residents’ roster with basic demographic information of each individual. In the second stage, from each village or community care center a random sample of residents who fall in the age range from 55 to 70 are interviewed with detailed questions about household composition, living arrangements, work-related migration of adult children, attitudes and plans for support in old age (such as anticipated sources of long-term care), and the health and health care utilization of the elderly. In particular, the correspondents report the demographic information for each of their children above age 16, regardless of whether the child was counted as a household member or was living under the same roof with the respondent at the time of the survey. Our stratified random sample of 12 villages and 3 community care centers in rural Shandong includes data on 676 older adults with 1,441 children and 1,553 grandchildren.

3.3 The Fuzzy RD Design

To facilitate direct comparisons between ESZ and our Guizhou study, we utilize a similar age discontinuity in the benefit structure of the social pension program to overcome the empirical challenge of endogenous pension receipt. This discontinuity produces an abrupt shift in eligibility among otherwise similar individuals and households. Assuming other household and individual characteristics are smoothly distributed according to age, i.e., the individuals very close to pension eligibility (in their late 50s) and those who just became eligible (in their early 60s) are comparable, the abrupt shift in eligibility utilized by this research design allows us to isolate the causal link between pension receipt and any shifts in outcomes of interest. These assumptions hold in both Shandong and Guizhou surveys. First, people do not seem to respond to the pension policies by altering age profiles (i.e., lying about their real age; see Figure A2). Second, key observable characteristics demonstrate smooth effects on the outcomes around the age 60 cut-off (Figure A3).

Since a few people below age 60 report receiving pensions because of variations in local policies and implementation, we adopt a Fuzzy RD design, which allows the jump in the probability of assignment to the treatment at the threshold to be smaller than 1. We interpret the ratio of the jump in the regression of the outcome on age to the jump in the regression of the treatment indicator on age as an average causal effect of the treatment (Imbens and Lemieux, 2008), which is analogous to an “intent to treat” parameter of a randomized controlled trial where the treatment is receiving pension income (pensioni), but because of “lack of compliance” a few people assigned to receive pension by passing the eligible age (1[agei ≥ 60]) do not actually end up receiving a pension. Formally, the Fuzzy RD estimand is

| (1) |

In other words, we evaluate how pension income impacts subsequent household outcomes (y) for compliers. Compliers are individuals who do not receive a pension if not eligible (below age 60) and receive a pension if eligible (above age 60). Formally,

| (2) |

Following ESZ, we present both reduced-form RD results and Fuzzy RD estimates of the treatment effect τFRD.10 Standard errors are clustered at the village level. All Fuzzy RD estimates are bias-corrected with robust standard errors. The results of this paper use a uniform kernel with the bandwidth selection proposed by Imbens and Lemieux (2008).

As placebo tests, we use data about the relevant factors prior to the NRPS (from earlier waves of the Guizhou survey, and from reported retrospective information in the 2012 Shandong survey) to rule out the possibility that predetermined factors confound the discontinuous changes we observe in outcome variables. Moreover, we report the results using the counter-factual age 59 as the pension eligibility age. Though households may anticipate pension receipt, our finding of little abrupt change in the main outcomes around the pseudo cut-off below age 60 suggests that credit constraints are likely a factor preventing individuals from borrowing against future income (Table A1).

4. Empirical Results

Table 1 presents summary statistics for the outcome measures used in this study, including living arrangements, transfers and service consumption for parents with adult children and grandchildren. Column (1) reports the mean and standard deviations for the full sample, i.e., households with respondents age 55 to 70. Columns (2) and (3) report means and standard deviations when confining the sample to households with a member between 55 and 65 years old (5 years around the age cutoff). Column (4) reports the result of a t-test comparing the difference between the mean of those below and above the pension eligibility threshold. Note that these descriptive statistics differ from the true causal effect of pension receipt, because the means and t-tests capture not only the pension effect, but also any trends regarding aging and cohort heterogeneity. The potential difference underscores the importance of using a rigorous study design such as regression discontinuity to distinguish the effect of pension income from the life cycle pattern of extended household formation and other outcomes.

Table 1.

Sample summary statistics of the outcome variables

| Dependent variable | All | [55,60yrs] | [60,65yrs] | Diff (3)-(2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Panel A. Co-residence (adult children) | ||||

| N (Guizhou/Shandong) | 1,741/1,441 | 324/396 | 325/355 | |

| Whether co-reside w. the elderly (Guizhou) | .303 (.460) |

.298 (.458) |

.114 (.318) |

−.184*** (.031) |

| Whether co-reside w. the elderly (Shandong) | .060 (.238) |

.141 (.349) |

.031 (.174) |

−.110*** (.020) |

|

Panel B. Service consumption (parents with adult children) | ||||

| N (Guizhou/Shandong) | 1,669/676 | 290/254 | 213/172 | |

| Being assisted in daily life by adult children when ill (Guizhou) | .052 (.222) |

.060 (.238) |

.027 (.161) |

−.033 (.028) |

| Whether expect to be admitted to hospital when recommended (Shandong) | .893 (.309) |

.925 (.264) |

.924 (.265) |

−.001 (.026) |

| Whether expect to use family care when ill (Shandong) | .700 (.459) |

.642 (.480) |

.686 (.465) |

.044 (.047) |

|

Panel C. Transfers in the past 12 months | ||||

| Ln(money Trans from the elderly) (Guizhou) | .493 (1.608) |

.109 (.787) |

.172 (.841) |

.063 (.092) |

| Ln(money Trans to the elderly) (Guizhou) | 1.030 (2.583) |

1.489 (2.933) |

.864 (2.327) |

−.626*** (.207) |

| Help w. tuition from the elderly (Guizhou) | .300 (.459) |

.209 (.408) |

.191 (.395) |

−.018 (.050) |

| Ln(tuition exp from the elderly) (Guizhou) | 1.590 (2.584) |

1.097 (2.248) |

.986 (2.109) |

−.111 (.272) |

| Range of money transfers from the elderly to all adult children (Shandong) | 1.627 (2.332) |

2.172 (2.626) |

1.563 (2.308) |

−.608** (.244) |

| Range of money transfers to the elderly from all adult children (Shandong) | 4.016 (2.383) |

4.088 (2.745) |

4.167 (2.381) |

.079 (.254) |

| Whether grandchildren receive presents or money from the elderly (Shandong) | .739 (.439) |

.812 (.391) |

.781 (.414) |

−.031 (.043) |

| Help w. tuition from the elderly (Shandong) | .146 (.354) |

.208 (.407) |

.149 (.357) |

−.058 (.041) |

Source: The fourth wave (2011) Guizhou survey and the 2012 Shandong survey.

Notes: [−5yrs,0) and [0,5yrs] mean parents’ age relative to the 60yrs cutoff. N denotes sample size.

A. The first stage: Pension receipt

Figure 1 plots the average rate of pension receipt against the cut-off age 60 for the Guizhou sample (corresponding to Figure 1 in ESZ). The fitted probability curves of receiving pension suggest almost a 70 percentage point jump (for Guizhou) and a 50 percentage point jump (for Shandong) in pension receipt immediately above the cut-off age. In Table 2, we regress the dummy indicator of receiving pension (1 if receiving pension, 0 otherwise), allowing a change in pension eligibility beginning from age 60. Both the nonparametric local linear regressions and the parametric RD estimations with the 2nd-order polynomials suggest that the probability of receiving a pension increases by 56.7 percentage points (Guizhou sample), 58.9 percentage points (Shandong sample), and 44.4 percentage points (national sample), respectively, after reaching the pension eligibility cut-off age 60.

Figure 1. Pension receipt according to normalized age (Guizhou Sample).

Source: The fourth wave (2011) Guizhou survey.

Notes: This figure shows the relationship between pension take-up rate and respondents’ normalized age. Age is normalized based on the day, month, and year information from date of birth.

General graphing notes: 0=eligibility threshold at age 60. The lines are nonlinear fit using rectangular weights on either side using the micro data. The dots represent averages of bins centered at .5 year bins (approximately 180 days). Graphs with different window and bin widths are available upon request.

Table 2.

First Stage: Estimands of Pension Receipt

| Dependent variable | N | Local Linear Regression | RD Estimate with 2nd-order polynomials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample of parents with adult children | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| Panel A. Guizhou survey | |||

| Indicator of Pension Receipt (1=yes; 0=no) | 1669 | .650*** (.137) Bw=3.612 |

.567*** (.177) |

| Panel B. Shandong survey | |||

| Indicator of Pension Receipt (1=yes; 0=no) | 670 | 594*** (.080) Bw=7.508 |

.589*** (.084) |

| Panel C. CHARLS national sample | |||

| Indicator of Pension Receipt (1=yes; 0=no) | 3,671 | .252*** (.036) Bw=4.180 |

.444*** (.032) |

Note: Panel A uses the Guizhou survey (2011). Panel B uses the Shandong survey; and Panel C uses the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) sample. In each panel, Column (1) is the number of observations; Column (2) reports the nonparametric RD estimand. We use local linear regression with the uniform kernel and choose the bandwidth by the method proposed by Imbens and Lemieux (2008); the results in Column (3) report the parametric RD estimand with the 2nd-order polynomials of the running variables.

Significant at the 1 percent level;

Significant at the 5 percent level;

Significant at the 10 percent level.

B. Consumption

In rural China, financial difficulties often prevent patients from receiving medical treatment recommended by doctors or otherwise defined as necessary. Evidence from both Shandong and Guizhou in Panel A Table 3 suggests that pension benefits may help to alleviate this problem by promoting confidence in ability to pay for necessary medical services. Specifically, both provinces show that pension income increases the confidence of elderly rural residents that they will be able to receive formal medical treatment (including outpatient services or hospitalization) when needed or recommended.

Table 3.

Service consumption by elderly parents

| Dependent Variable | N | Reduced Form RD | FRD Estimate | N | Reduced Form RD | FRD Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Elderly parents | Elderly parents with adult son | |||||

|

| ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|

Panel A. Evidence on service consumption

| ||||||

| Being assisted in daily life by adult children when ill (Guizhou) | 1,669 | −.316** (.158) Bw=2.726 |

−.439** (.222) Bw=2.844 |

1,220 | −.301** (.138) Bw=2.931 |

−.357** (.176) Bw=3.052 |

| Not getting formal medical treatment in the past 12 months when recommended (Guizhou) | 1,669 | −.429** (.205) Bw=2.912 |

−.463** (.219) Bw=2.964 |

1,220 | −.418** (.202) Bw=3.159 |

−.457** (.223) Bw=3.293 |

| Receiving in-family medical services (Guizhou) | 1,669 | .179 (.153) Bw=3.029 |

.236 (.198) Bw=3.174 |

1,220 | .183 (.150) Bw=3.352 |

.242 (.192) Bw=3.540 |

| Whether expect to be admitted to hospital when recommended (Shandong) | 676 | .130** (.059) Bw=3.696 |

.232** (.107) Bw=3.682 |

533 | .156*** (.050) Bw=4.126 |

.171*** (.052) Bw=4.787 |

| Whether expect to use family care provided by adult children when ill (Shandong) | 676 | −.066 (.082) Bw=3.993 |

−.125 (.143) Bw=3.978 |

533 | −.152 (.112) Bw=3.851 |

−.254 (.175) Bw=3.933 |

|

Panel B. Test continuity of take-up rate of health insurance | ||||||

| New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) enrollment (1=yes; 0=no) (Guizhou survey) | 1,669 | .122 (.074) Bw=3.102 |

.162 (.100) Bw=3.287 |

1,220 | .118 (.082) Bw=3.310 |

.142 (.117) Bw=3.559 |

| New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) enrollment (1=yes; 0=no) (Shandong survey) | 676 | .013 (.019) Bw=4.980 |

.009 (.019) Bw=4.611 |

533 | .014 (.026) Bw=7.333 |

.025 (.023) Bw=7.611 |

Note: The results use the Guizhou Survey and the Shandong survey. Columns (1)&(4) are the number of observations; using the nonparametric method, Columns (2)&(5) and columns (3)&(6) report the reduced form RD estimands and the FRD estimands, respectively. We use local linear regression with the uniform kernel and choose the bandwidth by the method proposed by Imbens and Lemieux (2008). Panel B checks the continuity of respondents’ taking up of the New Cooperative Medical System, which is the subsidized voluntary health insurance program for rural residents in China. Other notes follow Table 2.

In China, elderly parents who are seriously ill or experiencing difficulties because of a chronic disease often receive assistance from adult children. Pension income may enable the elderly to purchase some of these support services rather than rely exclusively on their children. Moreover, in-home care services by adult children (and daughters-in-law) almost inevitably decline when the two generations no longer co-reside. Our empirical analyses reveal that, compared to Shandong, elderly in Guizhou report a larger reduction in family care provided by adult children when the elderly parents are ill. The chance of being assisted by adult children on a daily basis when ill is reduced by 43.9 percentage points. All these patterns are consistent with pension income enabling the pensioner to consume more services to replace the care provided by children.

To establish the causal link, we need to rule out potential mechanisms behind the increase in the perceived access to needed medical services. For example, it is possible that the coverage by the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) might be higher among individuals above 60. In Panel B of Table 3 we test the continuity of NCMS take-up using the information collected in the survey. As shown in Table 3, we do not find any discontinuity of take-up rate of NCMS for the elderly at age 60. Therefore, none of the effects in confidence about medical service utilization appear to be driven by new purchases of health insurance coverage as a result of pension benefits.

C. Living arrangements

As daughters’ living arrangements are mainly dependent on marital status under the patriarchal residency tradition in China, only a tiny proportion of adult daughters co-reside with parents and they often play a secondary role in caring for parents compared to adult sons and daughters-in-law. Therefore, pension income is expected to mainly affect co-residency decisions of families with adult sons. Therefore, our analysis of living arrangements is restricted to parents with adult sons.

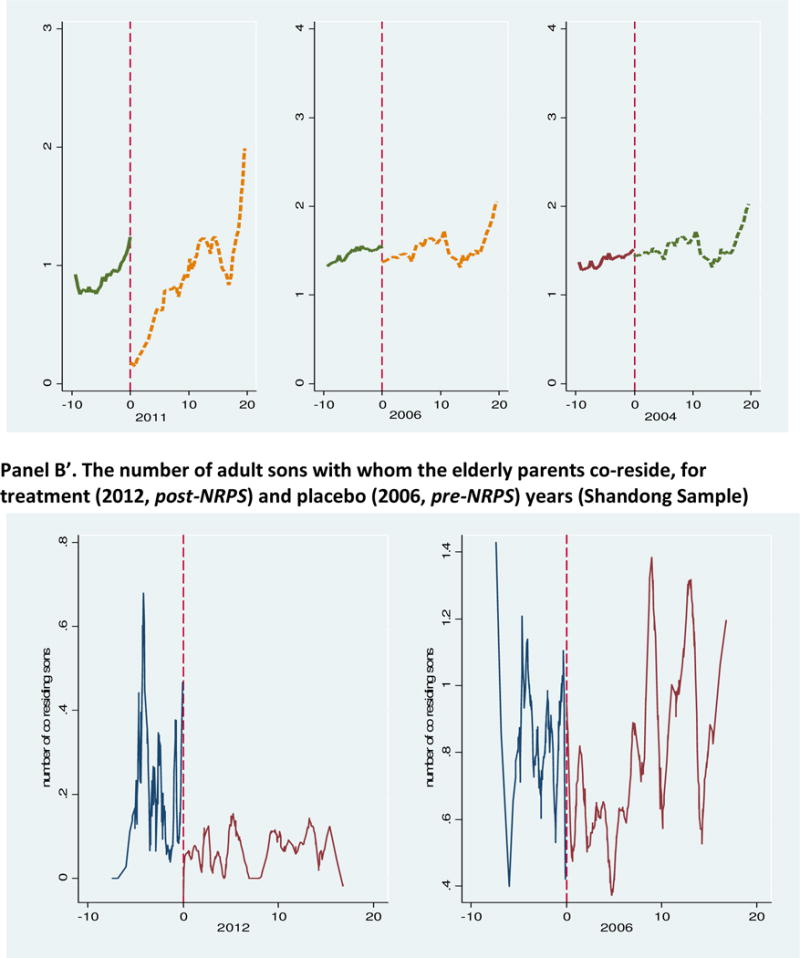

Living arrangements between adult sons and their parents in post-NRPS years and pre-NRPS years (placebo tests) are plotted in Figure 2. We plot the likelihood of co-residence (Panel A for the Guizhou sample, Panel A’ for the Shandong sample) and the number of co-residing sons for parents with at least one son (Panel B for the Guizhou sample, Panel B’ for the Shandong sample). We compare living arrangements around age 60 in 2011 (for Guizhou) and in 2012 (for Shandong) to living arrangements around age 60 in 2004 and 2006 (for Guizhou) and in 2006 (for Shandong). Since there is no discrete change at the age 60 cut-off in 2011/2012 using the 2004 and 2006 waves (the pre-NRPS period), the discontinuity in 2011 using the 2011 Guizhou sample (the post-NRPS period) suggests that our results should not be driven by any pre-existing discrete change at age 60. For the Shandong sample, however, we find insignificantly declining co-residence around age 60 in 2012.11

Figure 2. Living arrangements between adult sons and elderly parent.

Panel A. The proportion of adult sons co-residing with an elderly parent, for treatment (2011, post-NRPS) and placebo (2004 and 2006, pre-NRPS) years (Guizhou Sample)

Panel A′. The proportion of adult sons co-residing with an elderly parent, for treatment (2012, post-NRPS) and placebo (2006, pre-NRPS) years (Shandong Sample)

Panel B. The number of adult sons with whom elderly parents co-reside, for treatment (2011, post-NRPS) and placebo (2004 and 2006, pre-NRPS) years (Guizhou Sample)

Panel B′. The number of adult sons with whom the elderly parents co-reside, for treatment (2012, post-NRPS) and placebo (2006, pre-NRPS) years (Shandong Sample)

Source: Three waves Guizhou survey (2004, 2006, 2011) and two waves Shandong survey (2006) (2012).

Notes: These figures show relationships between rates of adult sons and number of adult sons co-residing with elderly parents and normalized age of the parents respectively for Guizhou and Shandong. We compare the likelihood and the number of adult sons with whom parents co-reside around age 60 in 2011 & 2012 to that in 2004 & 2006 around age 60 in 2011 (Guizhou) and in 2012 (Shandong).

Table 4 reports the results for reduced form RD and FRD estimations. In Panel A (the post-program period), adult sons are 26.6 percent point less likely to co-reside with parents once a parent receives pension. We reexamine the same idea using the sample of parents with at least one adult son. Panel C shows that at the pension-eligible age, the number of sons with whom the elderly parents co-reside decreases by 0.500 in Guizhou and 0.206 in Shandong, which is consistent with Panel A that adult sons are less likely to co-reside with parents. In the right part of Table 4, none of the co-residence indicators in the pre-NRPS period show a significant jump at the placebo age threshold, supporting our conjecture that the effects for 2011 (Guizhou) and 2012 (Shandong) identify the true pension impact rather than any pre-existing pattern of change at age 60.

Table 4.

Living arrangement of extended household members

| Post implementation (Guizhou, 2011; Shandong, 2012) | Before implementation (Guizhou, 2004&2006; Shandong, 2006) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Dependent variable | N | Reduced Form RD | FRD Estimate | N | Reduced Form RD | |

|

| ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | ||

|

Panel A. Sample of adult sons

| ||||||

| Co-residing with parent(s) (Guizhou) | 1016 | −.389*** (.081) Bw=2.756 |

−.266* (.140) Bw=2.771 |

1208 | −.033 (.127) Bw=2.816 |

|

| Co-residing with parent(s) (Shandong) | 768 | −.058 (.088) Bw=4.551 |

−.088 (.148) Bw=4.542 |

768 | .164 (.154) Bw=4.224 |

|

|

Panel B. Sample of the grandchildren from the sons’ families | ||||||

| Co-residing with grandparent(s) (Guizhou) | 682 | −.137*** (.051) Bw=2.754 |

−.138*** (.052) Bw=2.938 |

682 | .061 (.255) Bw=3.141 |

|

| Co-residing with grandparent(s) (Shandong) | 849 | −.114 (.090) Bw=4.351 |

−.168 (.166) Bw=4.333 |

|||

|

Panel C. Sample of parents with adult son | ||||||

| # of co-residing adult sons (Guizhou) | 1226 | −.374* (.205) Bw=2.969 |

−.500* (.279) Bw=2.751 |

2357 | −.054 (.112) Bw=2.860 |

|

| # of co-residing adult sons (Shandong) | 533 | −.123 (.108) Bw=5.680 |

−.206 (.185) Bw=5.675 |

533 | .299 (.251) Bw=6.852 |

|

Source: Three waves of Guizhou survey (2004, 2006, 2011) and Shandong survey (2006 (2012).

Notes: We compare living arrangement indicators around age 60 in 2011 (left table) to those in 2004 and 2006 around age 60 in 2011 (right table). The observations for the right placebo test table are from 2004 and 2006 for Guizhou sample and 2006 for Shandong sample. Panel A uses the data of adult sons; Panel B uses the sample of grandchildren from the sons’ families; Panel C uses the sample of elderly parents with at least one adult son. In each panel, Columns (1) and (4) are the number of observations; using the non-parametric method, Column (2) and Column (3) report the reduced form RD estimands and the FRD estimands, respectively. We use local linear regression with the uniform kernel and choose the bandwidth by the method proposed by Imbens and Lemieux (2008). Column (5) reports the reduced form RD estimand using non-parametric method in this placebo test when the pension program was not rolled out.

Significant at the 1 percent level;

Significant at the 5 percent level;

Significant at the 10 percent level.

Panel B of Table 4 presents findings on grandchildren co-residence decisions with grandparents. Again, we restrict the analysis to grandchildren from the sons’ families due to the patriarchal residency tradition in China. Results suggest that the probability of co-residence between the two generations decreases significantly by 13.8 percentage points in Guizhou, but insignificantly (16.8 percentage points) in Shandong.

Overall, consistent with a large flow of migration in the 2000s and the declining trend of co-residence in rural China (Peng 2011), the rate of co-residence for sons decreases from 2004–2006 to 2011. As we expected, the decline in intergenerational co-residence is larger and more salient in impoverished Guizhou in western China than in relatively developed Shandong in eastern China, given more children per parent and the relatively larger relaxation of household budget constraints that pensions represent in Guizhou.

D. Intergenerational transfers

It is interesting to test how transfers across generations respond to pension benefits. In Table 5, we report the results of RD exercises regarding the transfers between adult children and their parents, as well as the transfers between grandchildren and grandparents. The survey asks parents to recall the value of all cash and in-kind transfers between them and their adult children in the past 12 months. The information collected in Guizhou was in CNY, while a set of ranges denoted as a categorical variable was collected in Shandong. The data are consistent with the life cycle pattern of inter-generational transfers from children to elderly parents which often increases as parents age, but adult children in Guizhou with a parent eligible for pension transfer slightly less money to their parents.

Table 5.

Transfers between elderly parents and adult children in the past 12 months

| Dependent Variable | N | RD Reduced Form | FRD Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Panel A. Adult children | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| Ln(money Transfers from all adult children to the elderly) (Guizhou) | 1,741 | −.187 (.826) Bw=3.153 |

−.290 (1.173) Bw=3.148 |

| Ln(money transfers from the elderly to all adult children) (Guizhou) | 1,664 | −.065 (.064) Bw=3.015 |

−.105 (.106) Bw=3.260 |

| Range of money transfers from all adult children to the elderly (Shandong) | 1,437 | .343 (.365) Bw=6.431 |

.329 (.767) Bw=6.689 |

| Range of money transfers from the elderly to all adult children(Shandong) | 1,437 | .050 (.385) Bw=6.431 |

.139 (.665) Bw=6.689 |

|

Panel B. Grandchildren from adult sons’ families

| |||

| Help with tuition from the elderly (Guizhou) | 502 | − 298*** (.055) Bw=2.984 |

− 299*** (.055) Bw=2.746 |

| Ln(tuition expenses from the elderly) (Guizhou) | 502 | −1.697*** (.319) Bw=2.698 |

−1.704*** (.319) Bw=2.709 |

| Receive presents or money from the elderly (1=yes; 0=no) (Shandong) | 594 | −.088 (.150) Bw=3.898 |

−.091 (.260) Bw=3.950 |

| Care by the elderly (1=yes; 0=no) (Shandong) | 594 | −.007 (.129) Bw=4.844 |

−.032 (.241) Bw=4.868 |

Notes: Panel A uses the adult children sample from the Shandong survey and the Guizhou survey. We collect the data of intergenerational transfers by asking about such transfers during the past 12 months. We aim to investigate the transfers during the 12 months following pension receipt. Therefore, we define the cutoff age as 61 when running the RD modules. For the Shandong survey, the money transfers received from each child are aggregated to a range: 0 for no transfer, 1 for below 50 CNY yuan, 2 for 50~99CNY yuan, 3 for 100~199CNY yuan, 4 for 200~499CNY yuan, 5 for 500~999CNY yuan, 6 for 1000~2999CNY yuan, 7 for 3000~4999CNY yuan, 8 for 5000~9999CNY yuan, 9 for more than 10000CNY yuan. For the Guizhou survey, we directly model transfers in CNY. Panel B uses the sample of grandchildren from adult sons’ families in the Shandong survey and the Guizhou survey. In each panel, Column (1) is the number of observations; using the non-parametric method, Column (2) and Column (3) report the reduced form RD estimands and the FRD estimands, respectively. We use local linear regression with the uniform kernel and choose the bandwidth by the method proposed by Imbens and Lemieux (2008).

Significant at the 1 percent level;

Significant at the 5 percent level;

Significant at the 10 percent level.

Transfers between grandparents and grandchildren are declining in both Shandong and Guizhou (Panel B of Table 5). Compared to money transfers in general, tuition payment more explicitly gauges transfers across generations and may suffer less from measurement error and improper evaluation of monetary transfers. We show that grandparents are less likely to help with tuition payments. This is consistent with the finding that grandchildren are less likely to co-reside with grandparents, which also suggests that grandparents may be providing less daycare for grandchildren (Table 4 Panel B). The companionship between the two generations is changing. Pension payments seem not to be used to help their grandchildren. This finding is different from South Africa, where it was found that social pensions to grandmothers improve the nutrition status of grandchildren (Duflo, 2003).

Overall, these impacts of pension receipt on transfers between generations may suggest their weakening financial ties. One interpretation for the finding that pensioners transfer less money to adult children and grandchildren after household division, especially in Guizhou, is that they spend the money on hired services that were provided by adult children before separation. Another potential interpretation is that if pension income causes household division, grandparents derive less utility from companionship with grandchildren and as a result have lower incentive to invest in them. A third interpretation might be that adult children’s rising migration rate and off-farm employment (as a result of their parents’ pension benefits) bring more economic resources to their own children and therefore crowd out the demand for transfers from grandparents, with greater economic autonomy for each generation.

One might be concerned that if children pay pension premiums for their parents, this could substitute part of their regular transfers to parents via, for example, gifts and remittances. Therefore, the observed decline in transfers may not be genuine. Summary statistics show that elderly parents on average receive 921.05 CNY transfer from their adult children annually, and the transfers from adult children to their parents decrease by 29 percent as a result of pension receipt. The decrease in transfers to their parents (29%*921.05 CNY) tends to be larger than their pension premium payment for their parents (100 CNY in most cases). Therefore, even if we take into consideration that adult children may pay pension premiums for elderly parents, the overall transfers between the two generations appears to weaken when the pensions are introduced, suggesting that elderly parents may become more independent economically as a result of pension receipt.

5. Conclusions

Employing a fuzzy regression discontinuity design, we find three main impacts of the NRPS, all of which exhibit far greater magnitudes in the locality with lower income, Guizhou, than the locality with higher income, Shandong. First, the NRPS significantly reduces intergenerational co-residence around the pension eligibility age cut-off, especially between elderly parents and their adult sons. Second, our analysis suggests that the NRPS income promotes pensioners’ healthcare service consumption. Third, introduction of social pensions appears to weaken, albeit not eliminate, the intricate web of non-pecuniary and pecuniary transfers across three generations in rural China. In both provinces, family transfers to the elderly have only changed modestly compared to pension benefits the elderly receive, therefore there has been no salient crowd out effect on family transfers. Older persons in both provinces consume more health care and can afford to live more independently.

These results complement those of other recent studies using alternative datasets (see Chen and Park 2016; and Cheng, Liu, Zhang and Zhao 2016) to provide an increasingly detailed and consistent picture of the important impact of pension payments on the well-being of rural elderly and their families.

Huge differences in economic development across rural China, such as measured by poverty rate and per capita income, call for further adjustment in the pension benefit structure to reflect very different levels of economic development and corresponding costs of living. For example, the current basic pension benefits are essentially the same between Shandong and Guizhou, which reflect a pro-poor design in proportional terms but may need further adjustment to take account of costs of living. This and other efforts to strengthen the NRPS program can help improve the well-being of the elderly and their families across regions in China.

Figure A1. Statistics on the Rural Pension System in China (2002–2014).

Source: China Labor Statistical Yearbooks (2004–2015), Statistical Bulletin on the Social Development of Human Resources and Social Security (2002–2015).

Notes: The NRPS initiated at the end of 2009. The non-zero figures before 2009 represent the old unsubsidized social pension that covered a tiny proportion of rural residents, mainly in developed regions in China.

Figure A2. Testing Continuity of the Density of Normalized Age (Guizhou Sample).

Note: This figure for the Guizhou sample results from the implementation of McCrary (2008)’s test for continuity of the density of the normalized age at the cutoff age 60. The same figure for the Shandong sample were presented as Figure A1 in ESZ. The tests do not reject the null of continuity, and t-statistic equals .934 (for the Guizhou sample) and −1.42 (for the Shandong sample). The density of the normalized age is estimated by all elderly in years 2011 (Guizhou) and 2012 (Shandong), when the pension policy was implemented.

Figure A3. Testing Continuity of the Predetermined Respondents’ Characteristics at the Cutoff Age (Guizhou Sample).

Source: The second wave (2006) Guizhou survey.

Notes: This figure for the Guizhou sample shows main baseline demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of parents and normalized age of them. All these characteristics are dummy variables, indicating whether a parent is from the main ethnic group, holds a village leader position or communist party membership, finishes nine-year mandatory education, gets married, has religious beliefs, respectively. To save space, figures for other covariates, i.e., different types of family assets, controlled in the analysis are available upon request. General notes from Figure 2 apply. The figure for the Shandong sample were presented as Figure A2 in ESZ.

Table A1.

Effect on main outcomes allowing changes at age 59

| Dependent variables | N | RD Reduced Form/first stage | FRD Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Panel A. Sample of parents with adult son | |||

| Pension receipt (Guizhou) | 1,226 | −.152 (.126) Bw=3.203 |

|

| Pension receipt (Shandong) | 670 | −.022 (.060) Bw=4.905 |

|

| Number of co-residing sons (Guizhou) | 1,226 | .353 (.250) Bw=2.976 |

−.679 (.559) |

| Number of co-residing sons (Shandong) | 533 | .176 (.113) Bw=2.893 |

−.176 (.552) |

| Panel B. Sample of adult children | |||

| Co-residing with adult parent(s) (Guizhou) | 1,741 | .141 (.101) Bw=2.691 |

−.286 (.250) |

| Co-residing with adult parent(s) (Shandong) | 768 | .056 (.108) Bw=2.781 |

−.230 (.594) |

Notes: This table reports the results of using the counter-factual age 59 as the pension eligibility cutoff. Panel A uses elderly parents with at least one adult son, and Panel B uses the sample of adult children. In each panel, Column (1) is the number of observations; using the non-parametric method, Column (2) and Column (3) report the reduced form RD estimands and the FRD estimands, respectively. We use local linear regression with the uniform kernel and choose the bandwidth by the method proposed by Imbens and Lemieux (2008).

Significant at the 1 percent level;

Significant at the 5 percent level;

Significant at the 10 percent level.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial support from the NIH/NIA (Grant Number: 1 R03 AG048920), the U.S. PEPPER Center Career Development Award (P30AG021342), James Tobin Summer Research Fund at Yale Department of Economics, and the Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Approval numbers 70525003 and 70828002) are acknowledged. We appreciate data collection funding support provided by IFPRI (for the Guizhou survey) and Stanford University Asia Health Policy Program (for the Shandong survey with Xi’an Jiaotong University). Conference audiences at the AEA 2014 annual meetings and the 2nd Economics of Ageing Workshop on “The Economics of Ageing & Health” at Fudan University in May 2016 are acknowledged. The views expressed herein and any remaining errors are the authors’ and do not represent any official agency.

There are clusters of developing countries with large-scale social pensions: countries in the Southern Cone of Latin America; countries in southern Africa, including Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, and Swaziland; countries in south Asia, including Bangladesh, India, and Nepal. Outside these clusters, social pensions are scarce (Pallares-Miralles et al. 2012).

For example, social pensions improve mental health of the elderly (Chen and Wang 2016). Pensions reach prime-aged adults through promoting prime-aged labor migration (Bertrand et al. 2003; Posel et al. 2006; Ardington et al. 2009) and crowding out private transfers (Jensen 2004; Maitra and Ray 2003). Moreover, pensions affect children by discouraging child labor, promoting school enrollment (Edmonds 2006), improving nutrition and health status (Duflo 2000 and 2003; Case 2004), and pensioners’ care of grandchildren (Case and Deaton 1998).

Source: Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision, http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/index.htm.

Some regions in China stipulate that those aged 60 or above when the NRPS rolled out in the local county are eligible for the basic pension benefit only when their children eligible for the NRPS also enroll. However, this is not the case in our surveyed region in Guizhou.

Though the pension benefit only accounts for a small proportion of household income, it means a 7–8 times higher income for the elderly population in rural China who sometimes had no income before the NRPS (Zhang et al. 2013).

Among all 4536 individuals surveyed in the 2004 wave, 4339 were resurveyed in the 2006 wave (attrition rate=4.4%), 4221 were resurveyed in the 2009 wave (attrition rate=7.0%), and 3954 were resurveyed in the 2011 wave (attrition rate=12.8%).

The survey has four waves, i.e. 2004, 2006, 2009 and 2011. Each wave was implemented in January and/or February of the following year, i.e. 2005, 2007, 2010 and 2012. Since Guizhou province started the pilot NRPS in early 2010, the 2011 wave is in the post-NRPS period and the first two waves of 2004 and 2006 are in the pre-NRPS period. We do not use the 2009 wave data in placebo tests mainly due to two concerns. First, people may already know future implementation of the NRPS then. The resulting anticipation effect may confound the identification of the pension effect. Second, the 2009 wave overlaps with the recent world financial crisis, which possibly affects our main outcomes of interest, i.e. co-residence decisions, through unknown discontinuous changes around the age cut-off that contaminate the RD design.

We over-sampled elderly living in these dormitory-style community care centers (“yanglao yuan”, rarely providing comprehensive nursing services). According to the 2005 National Aged Population Survey only 1.2% of China’s rural elderly lived in a nursing home (Chen, Eggleston and Li 2011).

The fuzzy RD estimates in this paper adopt the second order polynomial specification around the age 60 cut-off. A model selection algorithm using the Schwarz (1978) criterion suggests qualitatively similar results for most outcome variables we study when using linear or third order polynomial specifications.

For discussion of village-level senior centers and their emerging role in living arrangements for some rural residents in China, see Liu, Eggleston and Min (2016).

Contributor Information

Xi Chen, Yale University and IZA.

Karen Eggleston, Stanford University and NBER.

Ang Sun, Central University of Finance and Economics.

References

- Ardington C, Case A, Hosegood V. Labor Supply Responses to Large Social Transfers: Longitudinal Evidence from South Africa. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2009;1(1):22–48. doi: 10.1257/app.1.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai F, et al., editors. The elderly and old-age support in rural China: challenges and prospects. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Card David, Carlos Dobkin, Nicole Maestas. Does Medicare Save Lives? The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2009;124(2):597–636. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2009.124.2.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A. Does Money Protect Health Status? Evidence from South African Pensions, Chapter 7 in NBER book. In: Wise David A., editor. Perspectives on the Economics of Aging. 2004. pp. 287–312. [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Deaton A. Large cash transfers to the elderly in South Africa. Economic Journal. 1998;108(450):1330–61. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wang T. Does Money Relieve Depression? Regression Discontinuity Evidence from the Pension Eligibility Age. 2016. (IZA Discussion Paper No 10037). [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zeng Y. Who benefits more from the new rural society endowment insurance program in China: Elderly or their adult children? Economics Research. 2013;8:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Zhang Y, Liu Z. Does the new rural pension scheme remold the elder care patterns in rural China? Economics Research. 2013;8:42–54. [Google Scholar]

- China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey (CHARLS) Team. Challenges of Population Aging in China. 2013 http://charls.ccer.edu.cn/uploads/document/public_documents/application/Challenges-of-Population-Aging-in-China-final.pdf.

- Cheng LG, Liu H, Zhang Y, Zhao Z. The Health Implications of Social Pensions: Evidence from China’s New Rural Pension Scheme. Presented at the 2nd Economics of Ageing Workshop on “The Economics of Ageing & Health”; Fudan University, Shanghai, PRC. May 2016.2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Eggleston K, Ling L. Demographic change, intergenerational transfers and the challenges for social protection in the People’s Republic of China. Manila: Asian Development Bank; 2011. p. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZY, Park A. Rural Pensions, Intra-household Bargaining, and Elderly Medical Expenditure in China. Presented at the 2nd Economics of Ageing Workshop on The Economics of Ageing & Health; Fudan University, Shanghai, PRC. May 2016; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa Dora L. Displacing the family: union army pensions and elderly living arrangements. Journal of Political Economy. 1997;105(6):1269–1292. [Google Scholar]

- Costa Dora L. A house of her own: old age assistance and the living arrangements of older nonmarried women. Journal of Public Economics. 1999;72:39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo Esther. Child Health and Household Resources in South Africa: Evidence from the Old Age Pension Program. American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings. 2000;90(2):393–398. doi: 10.1257/aer.90.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duflo Esther. Grandmothers and Granddaughters: Old-age pensions and intra-household allocation in South Africa. World Bank Economic Review. 2003;17(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds Eric, Kristin Mammen, Miller Douglas L. Rearranging the family? Income support and elderly living arrangements in a low income country. Journal of Human Resources. 2005;40(1):186–207. [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston Karen, Sun Ang, Zhan Zhaoguo. The Impact of Rural Pensions in China on Labor Migration. World Bank Economic Review 2016 Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Hamoudi A, Duncan T. Pension Income and the Well-Being of Children and Grandchildren: New Evidence from South Africa. California Center for Population Research Working Paper Series 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Hoerger T, Picone G, Sloan F. Public Subsidies, Private Provisions of Care and Living Arrangements of the Elderly. Review of Economics and Statistics. 1996;78(3):428–40. [Google Scholar]

- Imbens Guido, Lemieux Thomas. Regression discontinuity designs: A guide to practice. Journal of Econometrics. 2008;142(2):615–635. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen Robert T. Do private transfers ‘displace’ the benefits of public transfers? Evidence from South Africa. Journal of Public Economics. 2004;88(1–2):89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Ronald, Mason Andrew, members of the NTA Network Is low fertility really a problem? Population aging, dependency, and consumption. Science. 2014;346:6206. 229–234. doi: 10.1126/science.1250542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Xiaoyan, Zhang Chuanchuan, Zhao Yaohui. Incentive Problems in China’s New Rural Pension Program. In: Giulietti Corrado, Tatsiramos Konstantinos, Zimmermann Klaus F., editors. Labor Market Issues in China. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2013. pp. 181–201. (Research in Labor Economics, Volume 37). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Huijun, Eggleston Karen N, Min Yan. Village senior centres and the living arrangements of older people in rural China: considerations of health, land, migration and intergenerational support. Ageing and Society. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X16000714. Available on CJO 2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lund F. State Social Benefits in Social Africa. International Social Security Review. 2007;46(1):5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Maitra Pushkar, Ray Ranjan. The Effect of Transfers on Household Expenditure Patterns and Poverty in South Africa. Journal of Development Economics. 2003;71(1):23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Pinto D, Vera-Hernandez M. Risk protection, service use, and health outcomes under Colombia’s health insurance program for the Poor. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2013;5(4):61–91. doi: 10.1257/app.5.4.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Mangxiu, Gong Jinquan, Zheng Xuhui, Zhuang Jun. Does new rural pension scheme decrease elderly labor supply? Evidence from CHARLS. China Economic Review. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Pallares-Miralles Montserrat, Romero Carolina, Whitehouse Edward. International Patterns of Pension Provision II: A Worldwide Overview of Facts and Figures. The World Bank; 2012. (Social Protection & Labor Discussion Paper No. 1211). [Google Scholar]

- Peng Xizhe. China’s Demographic History and Future Challenges. Science. 2011;333(6042):581–587. doi: 10.1126/science.1209396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posel D, Fairburn J, Lund F. Labor Migration and Households: A Reconsideration of the Impact of Social Pension on Labor Supply in South Africa. Economic Modelling. 2006;23(5):836–853. [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo A, Schoellman T, Tertilt M. Families as roommates: changes in U.S. household size from 1850 to 2000. Quantitative Economics. 2012;3(1):133–175. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:497–511. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Giles J, Zhao Y. (CCER Working Paper).Evaluation of China’s New Rural Pension Program: Income, Poverty, Expenditure, Subjective Wellbeing and Labor Supply (in Chinese) 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer Z, Kwong J. Family size and support of older adults in urban and rural China: current effects and future implications. Demography. 2003;40(1):23–44. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]