Abstract

Programmed cell death–1 (PD-1) is a coinhibitory receptor that suppresses T cell activation and is an important cancer immunotherapy target. Upon activation by its ligand PD-L1, PD-1 is thought to suppress signaling through the T cell receptor (TCR). By titrating PD-1 signaling in a biochemical reconstitution system, we demonstrate that the co-receptor CD28 is strongly preferred over the TCR as a target for dephosphorylation by PD-1–recruited Shp2 phosphatase. We also show that CD28, but not the TCR, is preferentially dephosphorylated in response to PD-1 activation by PD-L1 in an intact cell system. These results reveal that PD-1 suppresses T cell function primarily by inactivating CD28 signaling, suggesting that costimulatory pathways play key roles in regulating effector T cell function and responses to anti–PD-L1/PD-1 therapy.

Tcells become activated through a combination of antigen-specific signals from the T cell receptor (TCR) and antigen-independent signals from cosignaling receptors. Two sets of cosignaling receptors are expressed on the T cell surface: costimulatory receptors, which deliver positive signals that are essential for full activation of naïve T cells, and coinhibitory receptors, which decrease the strength of T cell signaling (1). The coinhibitory receptors serve as checkpoints against unrestrained T cell activation and play an important role in maintaining peripheral tolerance and immune homeostasis during infection (2). One such receptor is programmed cell death–1 (PD-1), which binds to two ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, expressed by a variety of immune and nonimmune cells (3–5). The expression of PD-L1 is often induced by interferon-γ (IFNγ) and thus is indirectly controlled by T cells that secrete this cytokine upon activation (4, 6). In addition, T cell activation increases the expression of PD-1 on the T cells themselves (3). Thus, during chronic viral infection, T cells become progressively “exhausted,” in part reflecting a homeostatic negative feedback loop due to increased expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 (7–9). The interaction between PD-1 and its ligands also has been shown to restrain effector T cell activity against human cancers (10–14). Antibodies that block the PD-L1–PD-1 axis have exhibited durable clinical benefit in a variety of cancer indications, especially in patients exhibiting evidence of preexisting anticancer immunity by expression of PD-L1 (15–19). Interestingly, benefit often correlates with PD-L1 expression by tumor-infiltrating immune cells rather than by the tumor cells themselves.

Despite its demonstrated importance in the treatment of human cancer, the mechanism of PD-1–mediated inhibition of T cell function remains poorly understood. Early work demonstrated that binding of PD-1 to PD-L1 causes the phosphorylation of two tyrosines in the PD-1 cytoplasmic domain. Coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) and colocalization studies in transfected cells suggested that phosphorylated PD-1 then recruits, directly or indirectly, the cytosolic tyrosine phosphatases Shp2 and Shp1, the TCR-phosphorylating kinase Lck, and the inhibitory tyrosine kinase Csk (20, 21). Defining the direct targets of inhibitory effectors will be critical for understanding the mechanism of anti–PD-L1/PD-1 immunotherapy. However, the downstream targets of PD-1–bound effectors remain poorly understood. Recent studies have suggested that PD-1 activation suppresses TCR signaling (21–23), CD28 costimulatory signaling (24), ICOS costimulatory signaling (25), or a combination of pathways. Decreased phosphorylation of various signaling molecules, such as ERK, Vav, PLCγ, and PI3 kinase (PI3K), has been reported (21, 24), but these molecules are common effectors shared by both the TCR and costimulatory pathways and also may not be direct targets of PD-1. We sought to identify the immediate targets of PD-1–bound phosphatase(s) through a combination of in vitro biochemical reconstitution and cell-based experiments.

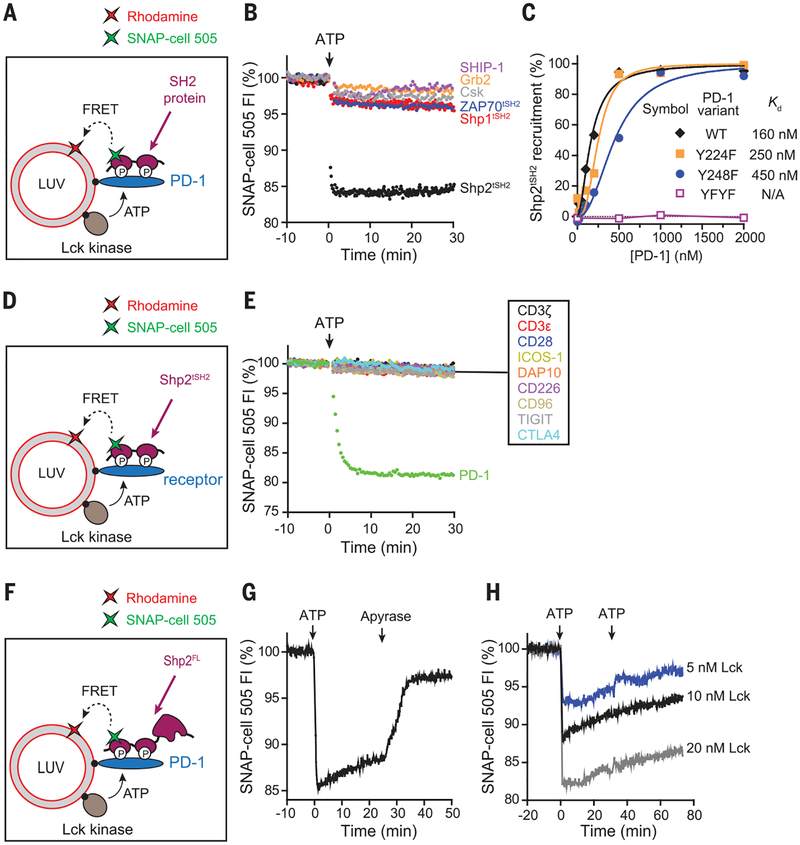

To gain insight into potential signaling pathways affected by activation of PD-1, we turned to a cell-free reconstitution system in which the cytoplasmic domain of PD-1 was bound to the surface of large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) that mimic the plasma membrane of T cells (Fig. 1A). We first determined which kinase(s) phosphorylate PD-1 by comparing the catalytic activities of Lck and Csk, the two kinases that were found to co-IP with PD-1 in cell ly-sates (20). Using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)–based assay (Fig. 1A), we found that Lck, but not Csk, efficiently phosphorylated PD-1 in vitro. Although Csk can weakly phosphorylate PD-1 on its own, it slowed down PD-1 phosphorylation in the presence of Lck (fig. S1), likely because of its ability to inhibit Lck. This finding, together with previous co-IP results (20), suggests that Lck is the major PD-1 kinase. We then asked which SH2 domain–containing proteins bind directly to phosphorylated PD-1. In addition to Lck and Csk, PD-1 also has been shown to co-IP with tyrosine phosphatases Shp2 and Shp1 (20) and contains a structural motif that might recruit the lipid phosphatase SHIP-1 (26). The biochemical FRET-based assay (Fig. 1A) demonstrated that phosphorylated PD-1 directly bound Shp2, but not Shp1, Csk, SHIP-1, or other SH2 proteins tested (Fig. 1B). A full titration experiment revealed a 29-fold selectivity of PD-1 toward full-length Shp2 over Shp1 (fig. S2A), in agreement with qualitative cellular studies (21). Unexpectedly, however, the tandem SH2 domains of Shp1 and Shp2 bound phosphorylated PD-1 with indistinguishable affinities (fig. S2B). Taken together, these data are consistent with a tighter autoinhibited conformation for Shp1 than for Shp2 (27), which may decrease Shp1’s affinity for PD-1. Mutation of either tyrosine (Y224 and Y248) in the cytosolic tail of PD-1 led to a partial defect in Shp2 binding, and mutation of both tyrosines eliminated binding (Fig. 1C and fig. S3). Although Y224 has been reported to be dispensable for the ability of PD-1 to co-IP with Shp2 (28, 29), our quantitative, direct binding assay shows that both tyrosines in the PD-1 cytosolic domain contribute to Shp2 binding. Collectively, these data suggest that Shp2 is the major effector of PD-1 and that Lck-mediated dual phosphorylation of PD-1 is needed for optimal Shp2 recruitment.

Fig. 1. Lck sustains the formation of a highly specific PD-1–Shp2 complex.

(A) Cartoon depicting a FRET assay for measuring the interaction between a SH2 domain–containing protein and membrane-bound PD-1. LUVs bearing Rhodamine-PE (energy acceptor) were reconstituted with purified Lck kinase and the cytosolic domain of PD-1, as described in the methods (supplementary materials). The SNAP-Tag–fused SH2 protein of interest was labeled with SNAP-Cell 505 (energy donor) and presented in the extravasicular solution. Addition of ATP triggered Lck-catalyzed phosphorylation of PD-1 and caused the recruitment of certain SH2 proteins to the LUV surface, leading to FRET. (B) A comparison of the PD-1–binding activities of a panel of SH2 domain–containing proteins, using the FRET assay as described in (A). Shown are representative time courses of SNAP-Cell 505 fluorescence before and after the addition of 1 mM ATP. Concentrations of components were 300 nM PD-1, 7.2 nM Lck, and 100 nM labeled SH2 protein. tSH2, tandem SH2 domains; FI, fluorescence intensity. (C) A comparison of the relative contribution of the two tyrosines of PD-1 in recruiting Shp2. Shown is the degree of Shp2 recruitment against the concentration of LUV-bound PD-1 wild type (WT) or tyrosine mutant, measured by the FRET assay described in (A). Raw data are shown in fig. S3. Kd, dissociation constant; F, phenylalanine. (D) Cartoon depicting a FRET assay for measuring the ability of a membrane-bound receptor to recruit Shp2. The experimental setup was the same as in (A), except that PD-1 was replaced with another receptor of interest, using the tandem SH2 domains of Shp2 as a fixed donor bearer. (E) A comparison of the Shp2-binding activities of the designated LUV-bound receptors, using the FRET assay shown in (D). Concentrations were 300 nM receptor, 7.2 nM Lck, and 100 nM labeled Shp2tSH2. (F) Cartoon showing a FRET assay for measuring the localization dynamics of full-length Shp2 (Shp2FL). LUVs bearing Rhodamine-PE (energy acceptor) were reconstituted with purified Lck kinase and the cytosolic domain of PD-1, as described in the methods. SNAP-Tag–fused Shp2FL was labeled with SNAP-Cell 505 (energy donor) and presented in the extravesicular solution. (G) Time course of the fluorescence of Shp2FL in response to sequential addition of ATP (2 mM) and the ATP scavenger apyrase (80 mg/ml) to the reaction shown in (F). Concentrations of components were 300 nM PD-1, 10 nM Lck, and 50 nM Shp2FL. (H) Time course of the Shp2FL fluorescence, showing the dynamics of Shp2 at indicated Lck concentrations. The assay was set up as in (F), and 2 mM ATP was added twice, at 0 and 30 min.

Using this reconstituted system, we next asked whether signaling receptors other than PD-1 (CD3ζ, CD3ε, CD28, ICOS, DAP10, CD226, CD96, TIGIT, and CTLA4) could recruit Shp2 (Fig. 1D). Notably, recruitment of Shp2 was not observed for any of these receptors, including for the two other coinhibitory molecules, TIGIT and CTLA4 (Fig. 1E). CTLA4 has been reported to co-IP with Shp2 (30) and is widely believed to suppress T cell signaling, at least partly through Shp2 (31). Our data suggest that Shp2 does not directly bind CTLA4 and that other proteins are likely required to bridge these two proteins. Overall, our results reveal an unexpected binding specificity of Shp2 for phosphorylated PD-1.

Recruitment of Shp2 to PD-1 raises the question of whether Shp2 might directly dephosphorylate PD-1 and cause the disassembly of the PD-1–Shp2 complex. To test this idea, we determined the stability of the PD-1–Shp2 complex by using a full-length Shp2 in the FRET assay (Fig. 1F). Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)–triggered phosphorylation of PD-1 caused the rapid recruitment of Shp2 (Fig. 1G) and activation of its phosphatase activity (fig. S4). Termination of the Lck activity by rapid ATP depletion caused a complete dissociation of Shp2 (Fig. 1G). This result indicates that Shp2 dephosphorylates PD-1 to destabilize the PD-1–Shp2 complex and that continuous Lck kinase activity is required to activate and sustain inhibitory signaling mediated by PD-1–Shp2. Interestingly, a slow spontaneous disassembly of the PD-1–Shp2 complex was observed even before the termination of Lck activity (Fig. 1G) and was not due to depletion of ATP because the dissociation continued even after further ATP addition (Fig. 1H). This result suggests that the activation of Shp2 upon binding to PD-1 allows Shp2 to override Lck, causing a gradual net dephosphorylation of PD-1. This positive-negative feedback loop of the Lck, PD-1, and Shp2 network would allow the system to quickly reset in the absence of PD-1 ligation or Lck activation.

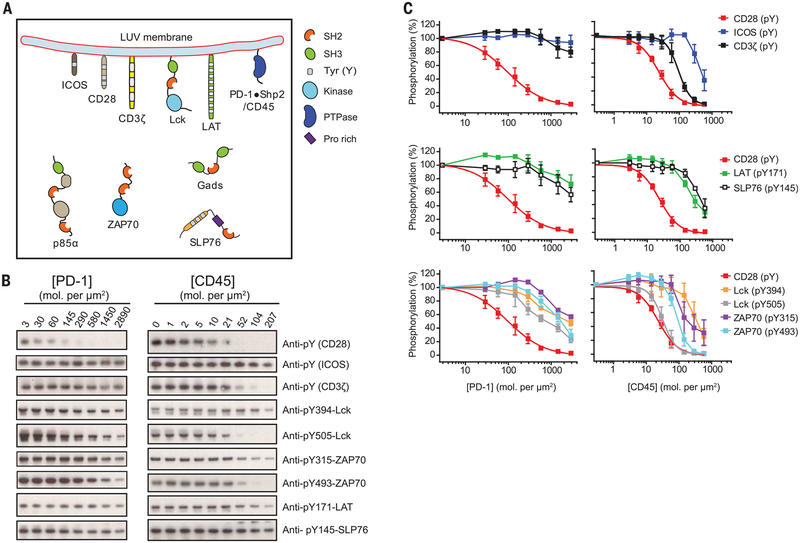

Having established a highly specific recruitment of Shp2 by PD-1, we aimed to identify substrates for dephosphorylation by the PD-1–Shp2 complex. We used a titration system that can provide insight into how the T cell network re sponds to gradual up-regulation of PD-1 during T cell development (32), activation (33), and exhaustion (e.g., in tumors or chronic viral infection) (7). To this end, we reconstituted a diverse set of components involved in the T cell signaling network (Fig. 2A), including (i) the cytosolic domains of various receptors [PD-1, TCR, CD28, and ICOS, another costimulatory receptor (34)]; (ii) the tyrosine kinases Lck, ZAP70 [a key cytosolic tyrosine kinase that binds to phosphorylated CD3 subunits to propagate the TCR signal (35)], and, in some experiments, the inhibitory kinase Csk (36); and (iii) the downstream adapter proteins LAT, Gads, and SLP76 (37), as well as the regulatory subunit of type I PI3K (p85α), which is known to be recruited by phosphorylated costimulatory receptors (fig. S5) (38, 39). All protein components were reconstituted at close to their physiological levels (fig. S6 and table S1), either onto LUVs or added in solution to mimic the geometry in T cells. A reaction cascade consisting of phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, and protein-protein interactions at the membrane surface was triggered by ATP addition. To test the sensitivity of components in this biochemical network to PD-1, we systematically titrated the levels of PD-1 on the LUVs and measured the susceptibility to dephosphorylation of each component by phosphotyrosine Western blots (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. CD28 is distinctively sensitive to PD-1–bound Shp2.

(A) Cartoon depicting a LUV reconstitution system for assaying the sensitivities of different targets to PD-1–Shp2. Purified cytosolic domains of plasma membrane–bound receptors (CD3z, CD28, and PD-1), the adaptor LAT, and the kinase Lck were reconstituted onto LUVs at their physiological molecular densities (table S1). Cytosolic factors (ZAP70, p85a, Gads, SLP76, and Shp2) were presented in the extravesicular solution at their physiological concentrations (table S1). In a parallel experiment, PD-1 and Shp2 were replaced with the liposome-attached cytoplasmic por tion of CD45. Addition of ATP triggered a cascade of enzymatic reactions and protein-protein interactions. PTPase, protein tyrosine phosphatase; Pro, proline. (B) Shp2-containing reactions with increasing concentrations of PD-1 and CD45-containing reactions with increasing concentrations of CD45, terminated at 30 min and subjected to SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and phosphotyrosine Western blots, as described in the methods. (C) The optical density of each band in (B) was quantified by ImageJ. The 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of PD-1 and CD45 on different targets were determined by using Graphpad Prism 5.0 to fit the dose response data in (B), or estimated from the dose response plots if the inhibition was incomplete even at the highest PD-1 or CD45 concentration (summarized in table S2). Error bars, SD from three independent experiments.

Notably, CD28—not the TCR or its associated components—was found to be the most sensitive target of PD-1–Shp2. As shown in Fig. 2, B and C (left panels), CD28 was very efficiently dephosphorylated, with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of ~96 PD-1 molecules/μm2 (table S2). In contrast, PD-1–Shp2 dephosphorylated the TCR signaling components only to a minor extent, including the TCR intrinsic signaling subunit CD3ζ, the associated kinase ZAP70, and its downstream adaptors LAT and SLP76, whose 50% dephosphorylation occurred at substantially higher PD-1 concentrations (>1000 molecules/μm2; table S2). Lck, the kinase that phosphorylates TCR, CD28, and PD-1, was the second-best target for PD-1–bound Shp2 in the reconstitution system. Both the activating (Y394) and inhibitory (Y505) tyrosines were ~50% dephosphorylated at similar levels of PD-1 (400 to 600 molecules/μm2). This result, however, suggests a net positive effect of PD-1 on Lck activity, owing to the stronger regulatory effect of the inhibitory tyrosine (40). The addition of the Lck-inhibiting kinase Csk rendered CD28 and TCR signaling components more sensitive to PD-1–Shp2, although CD28 remained the most sensitive PD-1 target (fig. S7 and table S2). The strong preferential dephosphorylation of CD28 was also observed at later time points in the in vitro reaction (fig. S8). In contrast to the strong CD28 preference of PD-1–Shp2, the transmembrane phosphatase CD45 efficiently dephosphorylated all of the signaling components tested (Fig. 2, B and C, right panels), with only three- to fourfold selectivity for CD28 over CD3ζ and ZAP70 (table S2).

To better understand the basis of the PD-1–Shp2 sensitivity to CD28, we deconstructed the reconstitution system into its individual modules (fig. S9). These experiments revealed that Shp2 alone dephosphorylates CD3ζ and CD28 with similar activities (fig. S9C), but that Lck has a sixfold higher catalytic rate (kcat) for CD3ζ over CD28 for phosphorylation (fig. S9, D and E). Thus, CD28 is a weaker kinase substrate, which in effect renders it more sensitive to PD-1–Shp2 inhibition in a kinase-phosphatase network. Based on our reconstitution of components at physiological concentrations, CD28 and, to a lesser extent, Lck are the major substrates for dephosphorylation mediated by PD-1–Shp2.

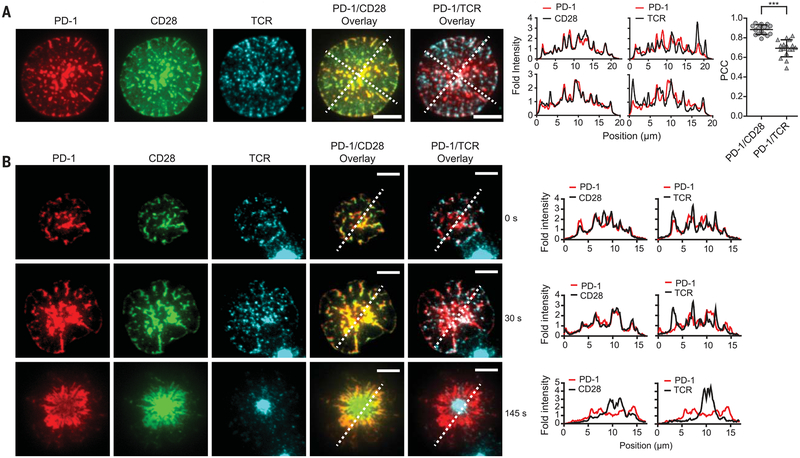

Having established that CD28 is highly sensitive to dephosphorylation by PD-1–Shp2 in vitro, we next sought to examine whether these two co-receptors colocalize in living cells and whether CD28 is indeed dephosphorylated in a PD-L1–dependent manner. Using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy and a supported lipid bilayer functionalized with an ovalbumin peptide–MHC class I complex (pMHC; TCR ligand) and B7.1 (CD28 ligand), we found that PD-1 strongly colocalized with the costimula-tory receptor CD28 in plasma membrane micro-clusters (Fig. 3 and movie S1). Previous work reported the colocalization of TCR and CD28 into submicron-size clusters after binding their ligands (41); however, we found significantly less (P < 0.0001) overlap between PD-1 and TCR [Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), 0.69 ± 0.09] than between PD-1 and CD28 (PCC, 0.89 ± 0.05) (means ± SD; n = 17 cells) (Fig. 3). Interestingly, although not itself a PD-1 substrate (Fig. 2, B and C), the ICOS co-receptor also more strongly colocalized with PD-1 than the TCR did (fig. S10). Strong colocalization of PD-1 and CD28 began from the time of initial cell-bilayer contact (0 s; Fig. 3B) and was sustained until the T cells fully spread (30 s; Fig. 3B). The molecules moved centripetally and eventually became segregated into a canonical bull’s eye pattern with a center TCR island surrounded by CD28 and PD-1, with the latter partially excluded from the TCR-rich zone (145 s; Fig. 3B). Because of their rapid colocalization and actin-driven flow, the clusters of PD-1 and CD28 most likely form on the plasma membrane and are not extracellular micro-vesicles secreted by T cells (42). Some degree of CD28 and PD-1 coclustering also was detected in the absence of pMHC, though the two co receptors remained largely diffusive without TCR activation (fig. S11). As shown previously (21), PD-1 clusters represented sites of Shp2 recruitment to the membrane (fig. S12). In the absence of PD-L1 on the bilayer, but with pMHC and B7.1 ligands, PD-1 remained diffusely localized (fig. S13 and movie S2), indicating that PD-L1 is required to bring PD-1 and costimulatory receptors into close proximity. Overall, these findings indicate that CD28 and PD-1 strongly cocluster with PD-1 in the same plasma membrane micro-domains in stimulated CD8+ T cells.

Fig. 3. PD-1 coclusters with costimulatory receptor CD28 but partially segregates with TCR.

(A) On the left are representative TIRF images of PD-1, CD28, and TCR of an OT-I CD8+ Tcell 10 s after landing on a supported lipid bilayer functionalized with recombinant ligands (100 to 250 molecules/μm2), which included pMHC (H2Kb;TCR ligand), B7.1 (CD28 ligand), and ICAM-1 (integrin LFA1 ligand). Cells were retrovirally transduced with PD-1‒mCherry and CD28‒ mGFP (monomeric green fluorescent protein), and the TCR was labeled with an Alexa Fluor647–conjugated antibody against TCR (see the methods). Scale bars, 5 μm. The experiment shown is representative of five independent experiments. In the plots to the right, intensities were calculated from the raw fluorescence intensities along the two diagonal lines in the overlaid images (see the methods). On the far right is a column scattered plot summarizing the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) values for the PD-1/CD28 overlay(0.89 ± 0.05, mean ± SD) and PD-1/TCR overlay (0.69 ± 0.09) of 17 fully spread cells, with each symbol representing a different cell. Statistical significance was evaluated by a two-tailed Student’s t test; P < 0.0001. (B) On the left are TIRF images showing the time course of the development of a PD-1–CD28–TCR immunological synapse, starting from initial contact with the supported lipid bilayer (0 s) and continuing to full spreading (30 s) and a bull’s eye pattern (145 s). Scale bars, 5 μm. The experiment is representative of four independent experiments. At right are histograms from the respective line scan quantifications.

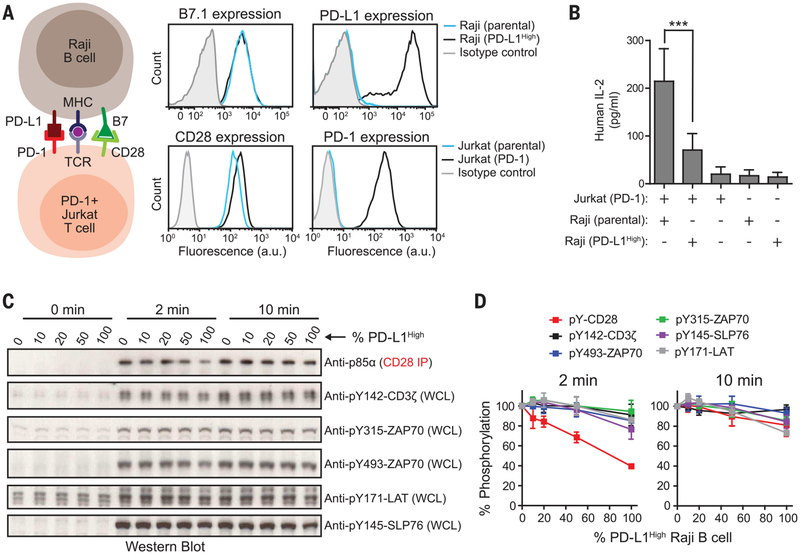

We next tested whether CD28 is the preferential target of PD-1 in intact T cells. For these studies, we used Jurkat T cells together with the Raji B cell line as an antigen-presenting cell (APC), because this system has been widely used for studying TCR and CD28 signaling (43). Because these cells lack PD-1 and PD-L1, we lentivirally transduced PD-1 and PD-L1 into Jurkat and Raji, respectively, obtaining PD-1+ Jurkat T cells that express ~40 PD-1 molecules/μm2 (table S1) and Raji B cells that express ~86 PD-L1 molecules/μm2 (designated as PD-L1High; Fig. 4A). PD-1+ Jurkat cells stimulated by antigen-loaded PD-L1High Raji B cells secreted significantly less interleukin-2 (IL-2) than those stimulated with antigen-loaded PD-L1– parental Raji B cells (63% decrease measured at 24 hours; Fig. 4B), indicating an inhibitory activity of PD-1 signaling in this cell system. We next tested how PD-L1 binding to PD-1 affects phosphorylation at the receptor level. To titrate the strength of PD-L1–PD-1 signaling, the PD-1–expressing Jurkat T cells were incubated with different ratios of PD-L1High to PD-L1– Raji B cells; because a T cell can interact with multiple APCs, this mixture of APCs might be expected to modulate the PD-1 response. Two minutes after APC and T cell contact, CD28 phosphorylation decreased as a function of the percentage of PD-L1High cells (Fig. 4, C and D). In contrast, no and substantially less dephosphorylation was observed for ZAP70 and CD3ζ, respectively. Notably, the PD-L1–PD-1 inhibitory effect on phosphorylation was transient, with far less dephosphorylation detected at 10 min (Fig. 4, C and D), perhaps reflecting the feedback loop described for the in vitro system (Fig. 1, G and H) that enables recruited Shp2 to dephosphorylate PD-1 and thereby repress the inhibitory signal. We next tested these results by using a Raji B cell line that expresses lower levels of PD-L1 (~16 molecules/μm2, designated PD-L1Low; fig. S14A), a density similar to that found in tumor-infiltrating macrophages and tumor cells (table S3). Using this lower-expressing APC line alone, we still detected a transient dephosphorylation of CD28 with little to no effect on TCR signaling components (fig. S14, B and C, t = 2 min).

Fig. 4. Intact cell assays confirm CD28 as the preferential target of PD-1–mediated inhibition.

(A) The cartoon on the left illustrates an intact cell assay in which CD28+, PD-1–transduced Jurkat T cells were stimulated with B7.1+, PD-L1–transduced (PD-L1High) Raji B cells pre-loaded with antigen. On the right are FACS (fluorescence-activated cell sorting) histograms showing the expression of B7.1 and PD-L1 in parental or PD-L1High Raji B cells and the expression of CD28 and PD-1 in parental or PD-1–transduced Jurkat T cells. a.u., arbitrary units. (B) Bar graph summarizing IL-2 release from a 24-hour Jurkat-Raji coculture with or without PDL1–PD-1 signaling and from each type of cell alone (see the methods). Data are presented as means ± SD from four independent measurements, with each run in triplicates. ***P < 0.0001; two-way ANOVA (analysis of variance). (C) A representative Western blot experiment showing the phosphorylation of CD28 and TCR signaling components in Jurkat Tcells in response to PD-L1 titration on antigen-presenting Raji B cells; the time after the initial contact of the two cell populations is indicated (see the methods). Different ratios of PD-L1High to PD-L1– Raji B cells (both containing pMHC and B7.1) were used to vary the PD-L1 stimulation to the Jurkat cells. Each condition con tained an identical number of Raji B cells (Raji to Jurkat ratio, 0.75). The phosphorylation states of CD3ζ, ZAP70, and LAT were immunoblotted with phosphospecific antibodies. Because of the lack of CD28-specific phosphotyrosine antibodies, CD28 was coprecipitated with p85α (see the methods), which is dependent on CD28 phosphorylation. WCL, whole cell lysate. (D) Quantification of phosphorylation data, incorporating results from three independent experiments (means ± SD).

Taken together, results obtained from both membrane reconstitution and intact cell assays demonstrate that PD-1–Shp2 strongly favors dephosphorylation of the costimulatory receptor CD28 over dephosphorylation of TCR (fig. S15). At high PD-L1 levels, we also observed some dephosphorylation of TCR components, such as SLP76 and ZAP70, in agreement with previous reports (20–22). However, by performing direct and quantitative comparisons, we found that the degree of TCR dephosphorylation was consistently much weaker than for CD28. The unexpected preference for inhibition of costimulatory receptor signaling, together with the recent work of Kamphorst et al. (44), may have implications for cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Although costimulation via CD28 is most often associated with the priming of naïve T cells, there is increasing evidence that it may play a role at later stages of T cell immunity in cancer and in chronic viral infection. Recent studies have demonstrated that the ability of anti–PD-L1/PD-1 therapy to restore antiviral (lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, LCMV) and antitumor T cell responses depends on CD28 expression by T cells (44). Blockade of B7.1 and/or B7.2 binding to CD28 has also been shown to completely eliminate the ability of anti–PD-L1/PD-1 therapy to prevent T cell exhaustion (44). These in vivo observations are consistent with expectations from our results, namely, that PD-1 exerts its primary effect by regulating CD28 signaling.

In at least a subset of human cancer patients, inhibition of T cell immunity is associated with the up-regulation of PD-L1 in the tumor bed in response to the release of IFNγ (2, 6, 15, 16). However, expression of PD-L1 by tumor-infiltrating immune cells can be independently predictive of clinical response and, in some types of cancer, even more predictive than PD-L1 expression by tumor cells (45). Infiltrating cells including lymphocytes, monocytic cells, and dendritic cells all express CD28 ligands, whereas tumor cells gen erally do not. If the primary target of PD-1 signaling regulation is through CD28 or another costimulatory molecule, then the therapeutic effect is likely to reflect reactivation of costimulatory molecule signaling on T effector cells, rather than (or at least in addition to) TCR signaling. Conceivably, costimulation is required to expand tumor antigen–specific early memory T cells, a process controlled intratumorally by B7.1+ APCs. Indeed, recent LCMV experiments have implicated an early memory population as the targets for expansion of anti–PD-L1/PD-1 therapy (46, 47). These findings strongly suggest the need for broadly considering the roles of costimulatory molecules in addition to CD28 in antitumor immunity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. Wang (Shanghai-Tech University) and F. Kai (University of California, San Francisco) for help with retrovirus transduction of primary T cells; N. Stuurman for training in TIRF microscopy; J. James (now at University of Cambridge) for providing the lentiviral transfer plasmid pHR-PD-L1-mCherry;A. Weiss (University of California, San Francisco) for providing the retrovirus vectors pMSCV, pCL-Eco, and anti-Lck antibody; andJ. Ditlev (M. Rosen’s laboratory, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) for providing His8-LAT. The data presented are tabulated in the main paper and the supplementary materials. We acknowledge R. Ahmed, A. Kamphorst, and membersof the Vale laboratory for comments and discussions. R.D.V.is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. D.K.S. was supported by NIH grant R21AI120010 and the Chicago Biomedical Consortium. J.H. was supported by NIH grants R00AI106941 and R21AI120010.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Chen L, Flies DB, Nat. Rev. Immunol 13, 227–242 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen DS, Mellman I, Immunity 39, 1–10 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH, Annu. Rev. Immunol 26, 677–704 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman GJ et al. , J. Exp. Med 192, 1027–1034 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong H et al. , Nat. Med 8, 793–800 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taube JM et al. , Sci. Transl. Med 4, 127ra37 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wherry EJ, Kurachi M, Nat. Rev. Immunol 15, 486–499 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Day CL et al. , Nature 443, 350–354 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butte MJ, Keir ME, Phamduy TB, Sharpe AH,Freeman GJ, Immunity 27, 111–122 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baitsch L et al. , J. Clin. Invest 121, 2350–2360 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma P, Allison JP, Science 348, 56–61 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pardoll DM, Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 252–264 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mellman I, Coukos G, Dranoff G, Nature 480, 480–489 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pauken KE, Wherry EJ, Trends Immunol 36, 265–276 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbst RS et al. , Nature 515, 563–567 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powles T et al. , Nature 515, 558–562 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rizvi NA et al. , Lancet Oncol 16, 257–265 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamid O et al. , N. Engl. J. Med 369, 134–144 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Topalian SL et al. , N. Engl. J. Med 366, 2443–2454 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheppard KA et al. , FEBS Lett 574, 37–41 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yokosuka T et al. , J. Exp. Med 209, 1201–1217 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zikherman J et al. , Immunity 32, 342–354 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zinselmeyer BH et al. , J. Exp. Med 210, 757–774 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parry RV et al. , Mol. Cell. Biol 25, 9543–9553 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett F et al. , J. Immunol 170, 711–718 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riley JL, Immunol. Rev 229, 114–125 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J et al. , J. Biol. Chem 278, 6516–6520 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chemnitz JM, Parry RV, Nichols KE, June CH, Riley JL,Immunol J. 173, 945–954 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okazaki T, Maeda A, Nishimura H, Kurosaki T, Honjo T, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 98, 13866–13871 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marengère LE et al. , Science 272, 1170–1173 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudd CE, Nat. Rev. Immunol 8, 153–160 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH, Annu. Rev. Immunol 23, 515–548 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oestreich KJ, Yoon H, Ahmed R, Boss JM, J. Immunol 181, 4832–4839 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hutloff A et al. , Nature 397, 263–266 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H et al. , Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 2, a002279 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bergman M et al. , EMBO J 11, 2919–2924 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang W, Sloan-Lancaster J, Kitchen J, Trible RP,Samelson LE, Cell 92, 83–92 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pagès F et al. , Nature 369, 327–329 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zang X et al. , Genomics 88, 841–845 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hui E, Vale RD, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 21, 133–142 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yokosuka T et al. , Immunity 29, 589–601 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choudhuri K et al. , Nature 507, 118–123 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian R et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 112, E1594–E1603 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamphorst AO et al. , Science 355, 1423 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fehrenbacher L et al. , Lancet 387, 1837–1846 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Im SJ et al. , Nature 537, 417–421 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.He R et al. , Nature 537, 412–428 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.