Abstract

Acculturation strategy, a varying combination of heritage and mainstream cultural orientations and one of the significant determinants of youth development, has been understudied with Asian American youth and particularly at a subgroup-specific level. This study used person-oriented latent profile analysis (LPA) to identify acculturation strategy subtypes among Filipino American and Korean American adolescents living in the Midwest. Associations between the subtypes and numerous correlates including demographics, family process and youth outcomes were also examined. Using large scale survey data (N=1,580; 379 Filipino American youth and 377 parents, and 410 Korean American youth and 414 parents; MAGE of youth=15.01), the study found three acculturation subtypes for Filipino American youth: High Assimilation with Ethnic Identity, Integrated Bicultural with Strongest Ethnic Identity, and Modest Bicultural with Strong Ethnic Identity; and three acculturation subtypes for Korean American youth: Separation, Integrated Bicultural, and Modest Bicultural with Strong Ethnic Identity. Both Filipino American and Korean American youth exhibited immersion in the host culture while retaining a strong heritage identity. Although bicultural strategies appear most favorable, the results varied by gender and ethnicity, e.g., integrated bicultural Filipino Americans, comprised of more girls, might do well at school but were at risk of poor mental health. Korean American separation, comprised of more boys, demonstrated a small but significant risk in family process and substance use behaviors that merits in-depth examination. The findings deepen the understanding of heterogeneous acculturation strategies among Asian American youth and provide implications for future research.

Keywords: Acculturation strategy, Filipino American, Korean American, Asian American, family process, race/ethnicity, youth development

Introduction

Adolescence is a life stage marked by the challenge of identity development (Erikson, 1968). Identity development unfolds as the adolescent differentiates the self from traditional constraints associated with family and institutional expectations (Bukobza, 2009). Biologically, adolescents are primed to engage in risk-taking as they test the boundaries of self (Steinberg, 2010). Decisions made in the impulsivity of adolescence can have long-reaching physical, social, and legal ramifications, and understanding the risks and protective factors of adolescent outcomes are a strong public health concern (Patton et al., 2016). Adolescence may be especially fraught for young Asian Americans, the overwhelming majority of whom have foreign-born parents (Pew Research Center, 2017). Asian American adolescents form identities and make decisions under the dual pressures of acculturation (the adoption of the mainstream culture) and enculturation (the retention of the heritage culture) (Choi, Tan, Yasui & Hahm, 2016; Castillo et al., 2012; Garcia Coll et al., 1996). Acculturation and enculturation are further complicated by family process, defined by parenting styles, values, behaviors and parent-child relationships. Family process is influential on youth acculturation and enculturation (Choi et al., 2016; Kim & Hou, 2016; Umana-Taylor et al., 2013; Knight et al., 2011). Youth acculturation strategy, in turn, may determine how youth perceive and thereby interact with family process (Choi, Kim, Pekelnicky, Kim & Kim, 2017; Choi, He, & Harachi, 2008). There is evidence that this interplay of acculturation and family process is among the most influential factors in developmental outcomes among cultural minority youth (Lui, 2015; Lim et al., 2009; Kim & Cain, 2008; Garcia Coll & Pachter, 2002).

Despite the consequential impact of acculturation and family process on Asian American adolescent development, few studies have examined how acculturation strategies correlate with family process and youth outcomes among Asian Americans. In particular, there is a scarcity of scholarship at the subgroup level. Though Asian Americans broadly may share aspects of family process, specific variables such as the gendered treatment of children and boundaries of family obligations are likely to differ across subgroups (Choi, Kim, Noh, Lee, & Takeuchi, 2017; Paik et al., 2017; Choi et al., 2008). Contemporary scholarship on Asian Americans, spurred by unprecedented levels of Asian immigration to the U.S., has only recently begun to differentiate among the over twenty Asian American subgroups, each with their distinct culture and sociopolitical context (Trinh-Shevrin, Islam, & Rey, 2009). To address these gaps in the literature, the present study uses latent profile analysis (LPA) to uncover latent subtypes of acculturation strategy among Filipino American and Korean American adolescents. These two groups share the pan-ethnic label of “Asian American,” but are notably dissimilar in acculturation patterns, family characteristics and youth outcomes (Choi, 2008; Choi et al., 2017). Identifying associations between the subtypes and a wide range of correlates including family process variables and youth outcomes will illuminate constructive acculturation strategies among Asian American subgroups, as well as bolster effective intervention among the rapidly growing population of Asian American adolescents.

Berry’s Model of Acculturation and Asian American Adolescents

In describing acculturation, we follow Kim and Abreu’s (2001) convention using linearity to refer to the number of cultures the model references, and dimensionality to the multiple domains on which acculturation can take place. The concomitant processes of acculturation and enculturation have been examined under Berry’s (1997) four-cell rubric of assimilation, integration, separation and marginalization. Berry’s bilinear model contravenes earlier unilinear models of acculturation to propose that acculturation represents coetaneous orientations to both the heritage and mainstream culture, albeit at variable levels (Berry, 1980). Assimilation denotes a maximum level of engagement with mainstream culture; integration, frequently referred to as biculturalism (Schwartz & Zamboanga, 2008), simultaneously engages both mainstream and heritage culture; separation is an exclusion of the mainstream culture and complete allegiance to the heritage culture; and marginalization indicates alienation from both mainstream and heritage culture.

Associations between these acculturation strategies and health and psychosocial outcomes are mixed and highly dependent on the characteristics of the sample population, as well as statistical method employed and specific operationalization of dimensions measured (Schwartz et al., 2010). Research concurs that acculturation happens at variable rates on multiple dimensions, such as mainstream language acquisition, ethnic pride, and cultural knowledge (Schwartz et al., 2010; Miller, 2007; Szapocznik et al., 1978). Nevertheless, a number of important studies have found that integration leads to the most adaptive functioning and those who are marginalized as experiencing the worst outcomes (Berry, 2005). Assimilation and separation, both of which entail individuals inhabiting either host or heritage culture to the relative exclusion of the other, are often thought to be maladaptive, but both strategies have differential impact among different immigrant groups. For example, assimilation has been associated with feelings of betrayal and distress as Asian American young adults experience racial/ethnic discrimination and structural inequality despite their assimilation into the host culture (Park, Schwartz, Lee, Kim, & Rodriguez, 2013). At the same time, assimilation has been found to be beneficial in certain domains, such as help-seeking behaviors (Miller et al., 2013). Similarly, separation strategy is largely found to be less adaptive than integration (Berry, 2005), as it isolates individuals from the majority culture. Yet, it has been found to be beneficial in certain circumstances; e.g., Korean immigrants have employed a separation strategy to build successful economic and social communities counter to the social exclusion and segregation practiced by their host culture (Min, 2006). Finally, while marginalization is uniformly found to be the most maladaptive (Fox, Merz, Solorzano, & Roesch, 2013), its prevalence in community samples has been challenged (del Pilar & Udasco, 2004; Schwartz & Zamboanga, 2008).

Among Asian American adolescents, acculturative variables have been associated with a variety of physical, psychological, and social outcomes including school performance (Fuligni, Witkow, & Garcia Coll, 2005), suicide attempts (Wong & Maffini, 2011), psychological functioning (Kim & Omizo, 2010), intergenerational conflict and depression (Ying & Han, 2007), smoking attitudes and behaviors (Weiss & Garbanati, 2004), binge drinking and alcohol use (Hahm, Lahiff, & Guterman, 2004), sexual behavior (Tong, 2013), and weight change (Diep, Baranowski, & Kimbro, 2017). With notable exceptions, the literature suggests that heritage retention, such as ethnic identity and heritage language competence, is associated with positive development among Asian American adolescents. A handful of studies have found that Asian American youth who retain, at least partially, heritage language competency or ethnic identity had positive associations with their family processes, demonstrating that family process may mediate the impact of acculturation strategies on youth outcomes (Choi, Kim, Pekelnicky, et al., 2017; Dinh & Nguyen, 2006; Tseng & Fuligni, 2000). Other studies uphold the immigrant paradox, whereby positive adolescent outcomes diminish as assimilation into the host country increases (Takeuchi, Hong, Gile, & Alegria, 2007). Though rapid assimilation of immigrants may be seen as desirable by the mainstream culture (Vigor, 2008), the actual impact of assimilation on family process should not be presumed, particularly as studies show that correlates in adolescent outcomes may differ across disparate domains of acculturation and enculturation (Choi, Kim, Pekelnicky, et al., 2017; Choi et al., 2016). This study, although not testing the interplay of acculturation, family process and youth outcomes in mediational models, aims to enhance a general understanding by investigating bivariate associations among the variables, which can lay the foundation for future and more complex analyses.

Identifying Acculturation Strategies

Investigating acculturation, family process, and youth outcomes among Asian American youth at a subgroup level faces several methodological challenges. First, notwithstanding scholarship cited above, acculturation at the adolescent level of development remains relatively sparse. A 22-year review found that more than half of the studies on acculturation were conducted with college students, who are by definition marked by a specific academic and social environment as well as unique transition into adulthood (Yang, Langehr, & Ong, 2011). Further, measures of family process validated across Asian American subgroups are rare (for an exception, see Choi, Kim, Noh, et al., 2017), as are models of acculturation that account for subgroup differences. Berry’s model, while still influential, has been criticized for insensitivity to group saliency (Schwartz & Zamboanga, 2008). A more nuanced approach to acculturation that takes into account specific characteristics of individuals, such as country of origin, socioeconomic status (SES), and heritage language, may have greater explanatory power and applicability to Asian American subjects (Chung, Kim, & Abreu, 2004; Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010).

The mixed findings on associations between acculturation strategies and developmental outcomes may be attributed in part to a priori classification rules, such as those used in the mean-split method, that assume all groups will fit into one of Berry’s four typology (Schwartz et al., 2010). In fact, when more statistically robust approaches, such as LPA, are used, multiple variants of Berry’s typology are uncovered. One such example is Choi et al. (2016)’s study finding that Korean American middle schoolers mostly utilized an integrated bicultural strategy with a strong sense of ethnic identity, some adopted separation or “modestly bicultural” strategy but none used assimilation or marginalization, with no participants altogether disavowing heritage culture and ethnicity. Another example is Chia and Costigan (2006)’s finding that Chinese Canadian college students are identified with, in addition to Berry’s four typology, two additional subtypes of acculturation strategy the authors labeled as “integrated group with Chinese practices” and “marginalized group with Chinese practices.” These variations are not unexpected, given the subgroup variability such as in sociopolitical and historical context of immigration, and traditional values and behaviors of heritage culture espoused by different Asian American subgroups.

In the present study, LPA allows us to derive sample-specific and person-centered subgroups that reflect the heterogeneity of acculturation strategies among Asian American subgroups (e.g., Fox et al., 2013; Chia and Costigan, 2006). The present study utilizes measures that are bilinear (i.e., acculturation and enculturation) and multidimensional (i.e., language, identity and cultural behavioral participation) to generate subtypes of acculturation strategy, which together allow for differential rates of acculturation across dimensions. For example, minority groups have been found to be more likely to adopt the behavioral norms of the dominant culture more readily than the values of the dominant culture (Rosenthal & Feldman, 1992). This finding was later affirmed with Asian American populations (Choi et al., 2018). In the present study, three distinct dimensions of cultural orientation are used in generating acculturation strategies: language competency, strength of identity, and behavioral cultural participation within host culture versus heritage culture (Choi et al., 2016; Ward, 2001). These dimensions are especially salient to Asian Americans, who often exhibit limited heritage language proficiency while varying in their espousal of strong ethnic identity or behavioral cultural participation (Tsai, Chentsova-Dutton, & Wong, 2002).

This study further examines how these measures are associated with various contextual variables, such as demographics, parental acculturation, family process and core cultural values. The examination of these associations examines and facilitates a comprehensive understanding of how Filipino American and Korean American adolescents vary across dimensions of acculturation strategies; how demographics and parental characteristics may contribute to the formation of those strategies; and the ways in which different acculturation strategies may shape youth perception of family process and race/ethnicity and, most importantly, may predict youth outcomes.

Filipino and Korean Americans

Filipino Americans and Korean Americans are the third and fifth most populous groups of Asian Americans, respectively, and as subjects of this study offer important points of overlap and divergence. These two Asian American subgroups share global indicators of SES, but differ in family process and acculturation (Russell, Crockett, & Chao, 2010) as well as academic and psychosocial outcomes among their progeny. U.S.-born Filipino Americans lag behind Korean Americans in college graduation, and in general Filipino Americans trail most of other Asian Americans in developmental outcomes (Choi, 2008; Ong & Viernes, 2013). Filipino Americans share a unique affinity with Latino culture (Ocampo, 2014) and are least likely, among all Asian American subgroups, to have limited English proficiency (Ramakrishnan & Ahmad, 2014). Filipino Americans, along with Japanese Americans, are least likely among all Asian American subgroups to live in a homogenous ethnic enclave (Ling & Austin, 2015).

Family processes among Filipino Americans are also distinct. Family dynamics are more egalitarian in Filipino culture as compared to other Asian subgroups (Paik, Witenstein, & Choe, 2016), but are more hierarchical and gendered than in White families, with Filipina youth experiencing particular expectations of filial loyalty (Espiritu, 2003). Immigrants from the Philippines are often thought to be the most assimilated of all Asian American subgroups (Vigor, 2008). In comparison, Korean Americans are a culturally and ethnically separated subgroup, with relatively low rates of English proficiency among Korean immigrant adults and higher tendency to self-segregate in ethnic enclaves (Min, 2006). Where Filipino culture emphasizes the girl’s responsibility to uphold filial loyalty, in traditional Korean culture, it is the eldest son that is expected to care for aging parents (Duk, 2013). These significant differences can be instructive in our understanding of acculturative strategies and their associated developmental outcomes among second-generation Filipino American and Korean American adolescents.

Correlates of Acculturation Strategy

There is a plethora of variables that are intertwined with acculturation/enculturation process and the resulting acculturation strategy. Some variables may be determinants of acculturation strategy (e.g., demographics). Other variables may be influenced by the specified acculturation strategy (e.g., family process), or the relationships may be reciprocal (e.g. Umana-Taylor et al., 2013). This study focuses on correlates from demographics, family process, race-ethnicity related and youth outcomes that are particularly pertinent to Asian American youth development. The list of correlates is intentionally extensive to provide as comprehensive a picture of relations as possible to serve as a springboard for future research. There are few, if any, studies that look at associations among these correlates and acculturation strategies across Asian American subgroups. Below is an explication of the correlates that are used in this study.

Demographics

Gender and age are differentially associated with the rates and patterns of acculturation and enculturation. For example, female gender predicts higher endorsement of host culture and its values, perhaps because of mainstream Western culture’s relatively egalitarian attitude toward women (Berry, 1997). Younger age at time of immigration predicts rapid acculturation and, in particular, language proficiency which is itself an oft-used proxy for acculturation (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001). In contrast, older age at immigration often predicts acculturation struggles and resistance to host culture (Cheung, Chudek, & Heine, 2010). Similarly, nativity and length of years in the U.S. predict higher host culture orientation. Parent’s demographics (e.g., age, years living in U.S., and immigrant and citizenship status) can also be significant predictors of youth acculturation strategies, in that longer years of residence in the U.S. and citizenship among parents predict more integrated acculturation strategies among youth (Choi et al., 2016).

Family Process

Family process includes parenting values, parenting behaviors and parent-child relationships. Asian American family process uniquely blends traditional Asian culture, the experiences of immigration and racial/ethnic minority status, and universal family process that is common across race/ethnicity (Choi, Kim, Noh, et al., 2017). In short, culture, race/ethnicity and immigration fundamentally shape Asian American family process, which may shape (or be shaped by) acculturation strategy. This paper organizes and reviews Asian American family process in the domains of (1) traditional core familism values, (2) indigenous family process that reflects heritage culture, (3) immigrant family process, (4) conventional family process, and (5) racial/ethnic socialization in the family.

Traditional core familism values

Among Filipino American and Korean American families, traditional core familism values include reinforcing respect for adults, family hierarchy and age veneration in family and social relations, making sacrifices to uphold harmony within the family, and remaining loyal to family obligations (Choi, Kim, Noh, et al., 2017). Family obligation may have a far greater ramification on Filipino American individuals than on Korean Americans, as Filipino Americans include extended family and close non-family members within their boundary of family (Espiritu, 2003).

Indigenous family process

Core familism values among Asian Americans are transmitted, inter alia, via parenting behaviors. Filipino American and Korean American parents, for example, reinforce heritage values by enforcing traditional manners and etiquettes that symbolize respect for adults and family hierarchy (Choi, Kim, Noh, et al., 2017). Asian parent behaviors are often viewed as more controlling and gendered than their Western counterparts (Garcia Coll & Pachter, 2002). However, Asian parental control (coined as order-keeping control) is different from Western parental control (i.e., coercive control) (Kagitçibasi, 2007) and likely expressed in terms of close monitoring (Chao, 1994), academically orientated control, and family obligation (Fuligni, 2007). Meanwhile, parental warmth and affection are often expressed indirectly in Asian American families. Wu and Chao (2011) operationalized the concept of qin as Asian American parental warmth characterized by implicit parental affection via instrumental support, devotion, and support for education rather than physical, verbal, and emotional expressions. Asian American adolescents’ acculturation strategies influence how they perceive their family process (Choi, Kim, Pekelnicky, et al., 2017). In addition, indigenous parenting may facilitate youth enculturation. Youth growing up in families practicing more traditional parenting may understand the intentions of parental behaviors and possibly internalize them. Conversely, culturally assimilated Asian American youth may adopt the mainstream stereotypes of their parents and view them as gendered, controlling, or emotionally distant (Choi, Kim, Pekelnicky, et al., 2017).

Conventional family process

Certain aspects of Asian American family process are culturally invariant and can be assessed by conventional, predominantly Western measures, for example, parenting style (authoritative and authoritarian), parent-child bonding and conflict, parental acceptance and rejection, parent-child communication, autonomy, and parental rules and restrictions (e.g. Sorkhabi, 2005). When bilinear and multidimensional cultural orientations were examined in relation to youth perception of family process, identity and behavioral enculturation positively predicted parent-child bonding, which was a notable protective factor for youth (Choi, Kim, Pekelnicky, et al., 2017). It may be that youth’s enculturation diminishes the acculturation gap and helps parent-child relations. It is also plausible that parent’s positive behaviors toward their child and expressive affection may help youth better understand parental culture, thus increase enculturation.

Immigrant family process

Culturally unique aspects of Asian American parenting may be further solidified by an immigrant ethos, i.e., shared traits among immigrants, including vigorous emphasis on education and a drive to succeed that is often accompanied by parental sacrifice to promote those values (Lee & Bean, 2010). Assimilation to the host culture often is associated with a weakened immigrant ethos (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001). Asian American adolescents can feel embarrassed by their parents, often because of their parents’ culturally inept behaviors or poor English (Choi & Kim, 2010), which may lead to conflict; indeed, intergenerational cultural conflict between parent and child is normative among immigrant families (Choi, He, & Harachi, 2008).

Racial/ethnic socialization

Racial/ethnic socialization by parents (i.e., cultural socialization, promotion of mistrust and preparation for bias) is a crucial aspect of both family process and acculturation strategies among racial/ethnic minority families (Hughes et al., 2008). Parental messages about race and ethnicity are generally meant to instill pride, prepare their children for bias, and/or promote mistrust of the mainstream. Active racial/ethnic socialization in the family, in particular that which promotes pride, is often identified as a protective factor for minority youth. However, the extent to which it interacts with acculturation strategy remains unclear.

Race/Ethnicity Related

Race/ethnicity related variables, such as an experience of racial discrimination, have notable associations with acculturation strategies. There is some evidence that immigrant children may idealize White families (Chung & Shibusawa, 2013); their perception of mainstream culture, especially if idealized, may encourage youth to prefer assimilation to host culture. Notably, a strong racial/ethnic identity, generally regarded as a protective factor, is correlated with greater reports of discrimination, while experiences of racial discrimination have a detrimental effect (Huynh & Fuligni, 2010; Operario & Fiske, 2001). How race/ethnicity variables interact with acculturation strategies remains to be examined.

Youth outcomes

Several studies establish that youth outcomes can vary dramatically among Asian American subgroups (Choi, 2008). As described above, varying acculturation strategies may confer differential risks on adolescent outcomes, and it is crucial to understand the interactional contexts in which acculturation occurs to accurately understand these risks (Schwartz et al., 2010). However, few studies look at this relationship across Asian American subgroups. Additionally, while Asian Americans in the aggregate may exhibit low rates of externalized problems, they endorse higher rates of internalized problems, including depression and suicidal ideation (Duldulao, Takeuchi, & Hong, 2009). In this study, the youth outcome correlates include both internal and externalized indicators, such as depressive symptoms, school grades, antisocial behaviors and substance use. A granular understanding of how internal and external problems are related to acculturation can help inform culturally competent interventions at the subgroup level.

Present Study

Using LPA, the present study develops the most parsimonious number of meaningful latent subtypes that best describes acculturation strategies in Korean American and Filipino American adolescents, without forcing fit onto any subtype. This study further expands prior studies by examining how different dimensions of acculturation collectively form variant strategies and how each strategy is associated with a detailed list of correlates, which are designed to accurately capture the nuanced experiences of growing up Asian Americans. Family process variables are specified to reflect cultural distinctions of Filipino American and Korean American families.

Explicating Acculturation Strategies

A total of 6 indicators used to generate acculturation strategies reflect bilinearity (acculturation and enculturation) and multidimensionality. Specifically, the dimensions of heritage language, ethnic identity, heritage cultural participation, English, American identity and host cultural participation were deliberately chosen to reflect the most relevant domains of acculturation among Asian American youth (Choi, Kim, Pekelnicky, et al., 2017; Choi et al., 2016).

Filipino and Korean American parents significantly differ in acculturation. Filipino American parents showed greater assimilation while Korean American parents endorsed more separation, placing the two subgroups of parents almost at opposing ends of the acculturation spectrum (Choi, Kim, Noh, et al., 2017). In contrast, based on prior limited studies, as well as the demographic data of our present sample, we expect Korean American and Filipino American adolescents to share a similarly high degree of linguistic assimilation, simply by the function of their nativity. The majority of Asian American youth are U.S.-born children of immigrants or children who immigrated at a young age. The rates of heritage language retention and linguistic enculturation are quite low, ranging from 1% to 10%, among U.S.-born Asian Americans (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001). Filipino American and Korean American adolescents may vary in other dimensions, such as identity and cultural practices. Similar to linguistic acculturation, we would expect a high degree of identity and behavioral acculturation across groups in our sample (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001). Enculturation is not straightforward. A handful of studies has found that children can concurrently exhibit a high level of linguistic and behavioral acculturation while also endorsing a strong racial/ethnic identity and frequently practicing certain aspects of their heritage culture (Atzaba-Poria & Pike, 2007; Costigan & Dokis, 2006; Telzer, 2010). Such a pattern has been found among the children of African or Caribbean immigrants (Waters, Ueba, & Marrow, 2007) and speaks to the differential experiences of immigrant parents and their progeny. We hypothesize that we will find a similar pattern across both our samples. We do not expect to find marginalization in this group of community samples.

We further hypothesize that, relative to Korean American youth, Filipino American youth would be acculturation leaning: self-reporting high fluency in English but limited heritage language and endorsing more host cultural behaviors than heritage ones. The notion of colonial mentality complicates our hypothesis vis-à-vis ethnic versus American identity. Some scholars argue that colonial mentality among Filipino American parents has been passed on to their children (David & Okazaki, 2006), while others point to lack of empirical data to support the claim. For example, in an in-depth study of over 100 Filipino American second-generation young adults, the participants demonstrated a solid and positive sense of ethnic identity, despite their perception of colonial mentality prominent among their parents (Ferrera, 2011). The sparse and conflicting research leaves us without a firm hypothesis regarding Filipino American youths’ sense of identities.

Conversely, in line with recent findings on middle school youth (Choi et al., 2016), Korean American youth are expected to show a largely integrated strategy with a strong sense of ethnic identity, with a small group of separation and modest bicultural youth but no assimilation group. Korean immigrant parents are known to adhere to their heritage culture and strong identity, residing mostly within ethnic enclaves and remaining monolingual (Min, 2006). In contrast, Korean American youth are predominantly English speaking with a low to modest heritage language retention but a strong sense of ethnic identity and varying degrees of heritage cultural participation (Choi et al., 2016). Relative to Filipino American youth, we expect Korean American youth to exhibit greater competency in their heritage language, mainly because of Korean parents’ lack of English proficiency (Choi et al., 2013).

Comparisons of Correlates

This study uses data from the Midwest Longitudinal Study of Asian American Families (ML-SAAF), a longitudinal study of Filipino and Korean American youth and their parents. ML-SAAF presents a rare opportunity to examine and compare two large Asian American subgroups of adolescents across a comprehensive list of correlates and their associations with acculturation strategies. Accurately measuring Asian American family process is challenging. The majority of existing measures were developed using White families (Chao, 1994) and they alone cannot provide a complete picture. ML-SAAF has significantly expanded the conventional repertoire of family process variables to include subgroup specific measures of core traditional values, and indigenous family process (for details, see Choi, Kim, Noh, et al., 2017; Choi, Park, et al., 2017). The latent subgroups were compared across the following sets of important correlates: demographics, family process including core cultural values, indigenous, conventional and immigrant family process, and racial/ethnic socialization, race/ethnicity related, and youth outcomes.

First, demographic correlates include age, gender, nativity, and the years of living in U.S. for youth and age, years living in the U.S., citizenship and permanent residence status for parents. We hypothesize that female gender, younger age, nativity, longer years of residence among youth, and parental acculturation indicators would be positively related with more acculturation than enculturation leaning strategies.

For family process, we examined core familism values including respect for adults, harmony and sacrifice, family obligation and boundary of the family. Indigenous Asian American family process correlates include parental emphasis on traditional manners and etiquettes that symbolize the core familism values, age veneration, gendered expectation, and academically oriented control. Addressing the nature of implicit parental affection among Asian parents, the parental affection construct includes both direct and indirect parental expression as well as the concept of qin which assesses instrumental support as a surrogate for expressions of affection. Additionally, several correlates include aspects of the immigrant ethos, such as parental emphasis on education, pressure to succeed, intergenerational cultural conflict between parent and child, and feeling embarrassed about immigrant parents. We also examined conventional family process correlates, including parenting styles (authoritarian and authoritative), parent-child bonding and conflict, parental acceptance and rejection, parent-child communication, autonomy, parental rules and regulations.

While the general pattern found in existing literature is that those youth who maintain aspects of their heritage culture are more likely to appreciate parental cultural behaviors and values, we lack a density of studies to guide us in forming specific hypotheses for each correlate. Therefore, we make general and directional hypotheses in regard to the associations between acculturation strategies and family process correlates. We expect that acculturation leaning strategies such as assimilation would correlate with lower core family values, indigenous family process, and immigrant family process, while enculturation leaning strategies such as separation would show reversed relationships. In addition, acculturation leaning strategies would be related to higher authoritarian style, parent-child conflict, parental rejection, and more rules and regulations, but lower authoritative style, parent-child bonding, parental acceptance, parent-child communication, and granting autonomy. Enculturation leaning strategies would show reversed relationships. Bicultural integration strategy, high both on acculturation and enculturation, is expected to show a pattern similar to that of enculturation leaning strategies in family process.

We examined three aspects of racial/ethnic socialization: cultural socialization, promotion of mistrust and preparation for bias. In addition, we included two race/ethnicity related constructs – experience of racial discrimination and youth idealized perception of White family. Although findings are mixed in the literature, enculturation is in general enhanced by active racial/ethnic socialization in the family, and increases an awareness of racial discrimination and protects youth from envying mainstream culture and mainstream families. We expect that separation and integration, which are high on enculturation, would report higher racial/ethnic socialization, higher racial discrimination but lower idealized perception of White family than assimilation. We expect assimilation to show an opposite pattern.

Finally, we included youth developmental outcomes as correlates, including depressive symptoms, school grade, antisocial behaviors and substance use. Biculturalism, also referred to as integration, has been hailed as the most protective for youth development (Berry, 1997; Nguyen & Benet-Martinez, 2013) and we hypothesize it will show most favorable adolescent outcomes in both external and internal behaviors. Assimilation and separation require alienation from either host or heritage culture, and are expected to show less favorable outcomes than integration.

The present study will shed light on how an integrated strategy of biculturalism may be related to multifaceted family process among Asian Americans. The numerous correlates presented in this study build a solid empirical foundation upon which future studies may examine multivariate relationships between acculturation strategies and family process, cultural value retention, racial/ethnic socialization, and youth outcomes.

Methods

Overview of the Project

Wave 1 of ML-SAAF surveyed a total of 1,580 individuals, comprised of 379 Filipino American youth and 377 parents (365 families were parent-child dyads) and 410 Korean American youth and 414 parents (407 families were parent-child dyads). All participants resided in Chicago and surrounding Midwest areas and were recruited from multiple sources, including phonebooks, public and private schools, ethnic churches/temples, ethnic grocery stores and ethnic community organizations. A proactive campaign and outreach about the survey continued to respective communities and organizations until the project reached its target numbers (at least 350 families for each subgroup).

The sampling unit was the family. Only families with an adolescent child ages between 12 and 17 (or in middle or high school) whose mother is of Filipino or Korean heritage were eligible. A single youth and his/her primary caretaker in each family were asked to participate. Although the majority of participating families were parent-child dyads, a small number of families included only the youth or the parent. Parents were approached first and, with their consent, youth were asked to participate. The study and its goal of better understanding Asian American family process and its impact on youth development were explained at initial contact as well as during the process of informed consent and assent. Participants received incentives ($40 for adults and $20 for youth). Parent and youth were separately surveyed to protect privacy. On average, the parent survey took about 1 hour and the youth survey 40 minutes. The study procedures were approved by the University’s IRB.

The participants were asked to be in-person interviewed but some preferred self-administration. Eighty-four percent of the survey was conducted by trained bilingual interviewers and the rest was self-administered. A slightly modified version of the interviewer-assisted survey was used for the self-administrated survey (e.g., changing “you” to “I”). The only significant demographic difference between self-administered and interviewer-assisted survey youth participants was their age. Self-administered participants were slightly older (15.33 vs. 14.95, p<.01). The ML-SAAF questionnaires, available both in paper-pencil and web-survey formats, were distributed to eligible participants and collected in person, by mail, or via web. The majority of self-administered surveys were done online and survey formats did not produce any significant differences in the key demographic variables. The questionnaires were available in English, Korean and Tagalog. The English version of survey was translated respectively into Korean and Tagalog using a committee translation process in which multiple translators made independent translations of the same questionnaire and, at a consensus meeting, the committee reconciled discrepancies and agreed on a final version. About 8% of youth participants used a heritage language version of the survey (61 Korean youth and 3 Filipino youth). The rest used an English version. The initial version of the survey was pilot-tested with 341 dyads (186 Korean American child-parent dyads, 155 Filipino American child-parent dyads) for psychometric properties and further revised for clarity before administered to participants in the main study.

Sample Characteristics

The average age was 15.28 (SD=1.89) for Filipino American youth and 14.76 (SD=1.91) for Korean American youth, with a larger proportion of high school students (78.69% Filipino American and 75.25% Korean American) than middle school students. Gender distribution among youth was about equal (56.20% Filipino American and 47.56% Korean American were girls). About 71% Filipino American and 58.29% Korean American youth were U.S.-born, and the average years of living in the U.S. among foreign-born were 8.47 years (SD= 4.24) for Filipino Americans and 8.13 years (SD= 4.28) for Korean Americans. The average age of parents was 46.21 years (SD=5.79) for Filipino Americans and 45.32 years (SD=3.76) for Korean Americans.

The participating parents were predominantly biological mothers (95.65% of Korean Americans and 92.02% of Filipino Americans), foreign-born (98.55% Korean Americans and 90.43% Filipino Americans) with an average of 16.04 years (SD=8.53) of living in the U.S. for Korean Americans and 21.38 years (SD=11.01) for Filipino Americans, highly educated (83.09% of Korean American mothers and 88.56% of Filipino American mothers having at least some college education either in Korea, Philippines or in the U.S.), currently married (92.03% Korean Americans and 88.56% Filipino Americans), and employed (64.69% of Korean American mothers and 87.23% of Filipino American mothers). Less than a quarter of Korean American and about 20% Filipino American families have received free/reduced-price school lunch. These demographic characteristics indicate highly educated middle income families and are consistent with those of Filipino American and Korean American families in Census or national-level data such as Add Health.

Measures

Unless noted otherwise, response options for all measures were an ordinal Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 5, e.g., never or not at all (1) to always or strongly (5). A higher score indicates a higher level of the constructs.

Indicators of subtypes

Language competency

Adopted from the Language, Identity, and Behavior (LIB) (Birman & Trickett, 2002), two sets of two parallel items (four total) measured youth language competency in speaking and understanding both heritage language (Filipino or Korean) and host language (English). Examples of Filipino languages include Tagalog, Bisayan (or Visaya), Ilocano, Kapampangan, and several others. [r=.84 (Filipino American) and .89 (Korean American) for heritage language; r=.75 (Filipino American) and .84 (Korean American) for English].

Behavioral cultural participation

Also adopted from the LIB (Birman & Trickett, 2002), 10 items asked about participation in either heritage or American cultural activities such as social gatherings, media use, and peer composition [α=.79 (Filipino American) and .74 (Korean American) for heritage cultural participation; α=.75 (Filipino American) and .75(Korean American) for host cultural participation].

Identity

Ethnic and American identity were assessed respectively using 10 questions from LIB (Birman & Trickett, 2002), asking the extent to which youth identified themselves as Filipino/Korean or American [α=.76 (Filipino American) and .77 (Korean American) for ethnic identity; α=.81(Filipino American) and .77 (Korean American) for American identity].

Correlates

Demographics

We included several youth-reported and parent-reported demographic variables such as age, gender (0 girls, 1 boys), place of birth (0 foreign born, 1 U.S.-born), years of living in the United States and immigrant legal status including U.S. citizen (0 no, 1 yes) and permanent resident (0 no, 1 yes).

Family process

Traditional core cultural values

Several scales were used to examine youth’s endorsement of traditional core cultural values. They include (1) Respect for Adults: 3 items, e.g., “Even if I am very angry at an older person, I shouldn’t fight or talk back, out of respect,” “Parents and grandparents should be treated with great respect regardless of their differences in views.” [α=.74 (Filipino American) and .72 (Korean American)]; (2) Harmony and Sacrifice: 3 questions to ask about the importance of maintaining harmony and sacrificing individual needs for greater units like family and community, e.g., “It is important to ensure harmonious relations with family members, even at the expense of my own desires,” “It is important to sacrifice individual(s) for the greater good (e.g., family, friends, or community)” [α=.71 (Filipino American) and .60 (Korean American)]; (3) Family Obligations: 7 items adopted from two sources (Choi, 2007; Fuligni & Zhang, 2004), assessing the extent to which youth help out with their family, e.g., “How often do you translate or interpret for your parent?” “How often do you help take care of your family members (for example, younger brothers or sisters, grandparents, sick parents, etc.)?” [α=.63 (Filipino American) and .61 (Korean American)]; (4) Boundary of the Family asked participants who they regard as family, from 8 categories [e.g., “my parents and siblings”, extended family members (“my grandparents of father side” “cousins”) to godparents or close family friends]. A total number of chosen categories were counted as an index to measure the boundary of the family.

Indigenous family process

Five scales were used tap into youth perception of their parent’s traditional values and behaviors that conventional measures of parenting may not capture. The constructs were (1) Traditional Manners and Etiquettes: a 4-item scale, asking youth how much their parents emphasize ethnic behaviors that symbolize respect of the elders, e.g., “To greet adults/elders properly (e.g., [for Koreans] bowing to adults and saying “an-nyung-ha-se-yo” or [for Filipinos] gently placing the back of one’s hand on elders’ forehead and saying “monopo” “To use proper addressing terms (e.g., calling family members with addressing terms instead of first names [for Koreans] unni/nuna, oppa/hyung, harabugi/halmony and [for Filipinos] ate, kuya, lola/lolo, ninang/ninong)” [α=.83 (Filipino American) and .80 (Korean American)]; (2) Gendered Expectation: 7 items adopted from multiple sources (de Guzman, 2011; Espiritu, 2003; Nadal, 2011; Wolf, 1997) to measure youth perception of parental restrictive norms towards girls (e.g., “My parents think that girls should not date while in high school” “My parents think that girls should not stay out late” or “My parents think that boys should avoid anything girlish or feminine” [α=.81 (Filipino American) and .79 (Korean American)]; (3) Academically Orientated Parental Control: 8 items from Chao and Wu (2001) to assess parental control specific to academic related child’s behaviors (e.g., How often do your parents “make sure you do homework,” “limit your social activities (e.g., hanging out with your friends or partying) so that you can work (e.g., studying or practicing musical instruments” or “punish if your grades are down” [α=.67 (Filipino American) and .73 (Korean American)]; (4) Qin (Wu & Chao, 2011): 9-item scale that assesses Asian parent-child bonding through instrumental support (e.g., My parents “invest all what they have for my education” “know all my possible needs before I am aware of them” and “understand my difficulties even though they don’t say anything” [α= .85 (Filipino American) and .84 (Korean American)]; and (5) Parental Affection: 5 questions from the Korean American Families (KAF) Project (Choi, 2007) assessing the extent to which youth perceive parental affection when expressed directly or indirectly (e.g., You feel loved when your parents “tell you that they love you” “when they are strict about bad things like smoking and violence” or “even if they don’t say, when they do things for you, like making your favorite food, putting your needs before theirs, being there for you when you have hard times”) [α= .83 (Filipino American) and .78 (Korean American)].

Conventional family process

Eleven existing conventional family process measures were used to assess youth perception of parenting styles, behaviors and parent-child relations. They were (1) Authoritarian Parenting Style: 4 questions from Parenting Authority Questionnaire (PAQ) (Buri, 1991) that assess stern and strict parenting (e.g., not allowing to question any decision parent makes, getting very upset if child tries to disagree with parent). [α=.80 (Filipino American) and .78 (Korean American)]; (2) Authoritative Parenting Style: 2 questions also adopted from PAQ (Buri, 1991) (e.g., my parent directs my activities and decisions through reasoning and disciplines or consistently gives me direction and guidance in rational and objective ways) [r=.63 (Filipino American) and .60 (Korean American)]; (3) Parent-Child Bonding: 5 questions from the Add Health, asking the extent to which the child feels close to his/her mom and wants to be the kind of person she is [α=.88 (Filipino American) and .85 (Korean American)]; (4) Parent-Child Conflict : 4 questions from Prinz (1977) about getting angry at each other or the parent not listening to child’s side of the story [α=.83 (Filipino American) and .79 (Korean American)]; (5) Parental Acceptance: 9 questions from Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ) (Rohner, 2004), e.g., “My mom makes me feel wanted and needed.”(α=.90 for both); (6) Parental Rejection: 15 PARQ items (Rohner, 2004), e.g., “My mom is too busy to answer my questions.”[α=.89 (Filipino American) and .84 (Korean American)]; (7) Parent-Child Communication: 4 questions from the LIFT project (Eddy, Reid, & Fetrow, 2000), e.g., “I talk with my parents about what is going on in my life.” [α=.93 (Filipino American) and .92 (Korean American)]; (8) Granting Autonomy: 8 items from Silk, Morris, Kanaya, and Steinberg (2003) and Grolnick, Ryan, and Deci (1991), e.g., “My mom keeps pushing me to think independently.” [α=.77 (Filipino American) and .72 (Korean American)]; (9) Parental Rules and (10) Parental Restrictions were a compilation of rules and disciplines that parents may use such as curfew, homework rules, grounding and corporal punishment and the response options were binary (Yes and No).

Immigrant family process

Four additional constructs pertinent to the immigrant family were included: (1) Emphasis on Child’s Education: 2-item measure from Wu and Chao (2011) examining parental willingness to support and sacrifice for their child’s education (e.g., “My parents work very hard to provide the best for my education” “My parents do everything for my education and make any sacrifices” [(r=.62 (Filipino American) and .69 (Korean American)]; (2) Intergenerational Cultural Conflict was from Lee and his colleagues (2000), assessing discrepancy of values across immigrant parents and their children (e.g., “Your parents tell you what to do with your life, but you want to make your own decisions.”) [α=.89 (Filipino American) and .85 (Korean American)]; (3) Pressured to Succeed: 10-item scale from multiple sources (Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate, 1990; Silk et al., 2003; Soenens, Vansteenkiste, & Luyten, 2010), e.g., “My mother shows she loves me less if I perform poor.” “When I get a good grade, my mother says my other grades should be as good” [α=.85 (Filipino American) and .87 (Korean American)]; (4) Feeling Embarrassed by Parents: 5 questions from KAF (Choi, 2007), assessing the degrees to which the child feels embarrassed about their parent’s poor English or culturally awkward behaviors (e.g., “There are times when I feel embarrassed about my parents’ poor English” “about my parents being awkward with other Americans” [α=.75 (Filipino American) and .81 (Korean American)].

Racial/ethnic socialization

Three racial/ethnic socialization correlates were: (1) Cultural Socialization: 3 questions (Choi, 2007), asking youth how much their parents emphasize “feeling proud of being Korean/Filipino” and “maintaining Korean/Filipino traditions and values” [α=.72 (Filipino American) and .74 (Korean American)]; (2) Promotion of Mistrust: 3-item scale was from Tran and Lee (2010), asking youth how their parents told them to avoid or keep distance from other racial/ethnic groups [α=.83 (Filipino American) and .86 (Korean American)]; (3) Preparation for Bias: 5-item scale also from Tran and Lee (2010) asks youth how often their parents to prepare them against racial/ethnic stereotypes, prejudice, and/or discrimination (α=.81 for both).

Race/ethnicity related

Two correlates were included that are related to race/ethnicity. (1) Perceived Racial Discrimination: 5-item scale developed for the ML-SAAF study based on several focus groups conducted prior to the survey, assessed how often youth felt discriminated by, e.g., whites, nonwhites, racial/ethnic minorities, peers and teachers (α=.74 for both); (5) Youth Perception of White Family: 11-item scale, developed for this study and measuring youth perception of White parents being more lenient than Asian parents (e.g., “Filipino/Korean parents are stricter than White parents”; “White kids can decide things for themselves more so than Filipino/Korean kids can”). [α=.91 (Filipino American) and .87 (Korean American)].

Youth outcomes

Youth outcomes included (1) Depressive Symptoms: 14 depressive symptom items from the Children’s Depressive Inventory (Angold, Costello, Messer, & Pickles, 1995) and the Seattle Personality Questionnaire for Children (Kusche, Greenberg, & Beilke, 1988) [α=.94 (Filipino American) and .93 (Korean American)]; (2) School Grade was computed based on grades in English, math, social studies, and science; (3) Antisocial Behaviors:19-item list adopted from DSM-IV conduct disorder criteria (Gelhorn et al., 2009) and Add Health, including bullying, physical fights, hurting others, and stealing. The variable was constructed to 0 for none and 1 for any antisocial behavior, (4) Substance Use was constructed based on five substance uses (past and current smoking, unsupervised drinking, illegal substances and unauthorized prescription drugs). Similar to antisocial behaviors, a binary variable was created to indicate 0 for no substance use and 1 for any substance use.

Analysis

Using Mplus v.7.4 (L. K. Muthén & Muthén, 2013), we conducted LPA to generate the most parsimonious number of subtypes describing youth acculturation strategy patterns. LPA is a person-oriented approach that categorizes individuals who share common characteristics that are derived from continuous observed variables (B. O. Muthén & Muthén, 2000). In the LPA framework, individuals are assigned probabilities according to their likelihood of membership in each group and then allocated into the group with the highest probability (Magnusson, 1998). Six variables were used to derive the subtypes: heritage and English language competency, heritage and American cultural participation, ethnic and American identity.

To identify the ideal number of subtypes in the samples, several fit statistics were examined, for example, the Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criteria (BIC), sample-size adjusted BIC, entropy, Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR-LRT), and the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (L. K. Muthén & Muthén, 2013). Specifically, AIC, BIC, and the sample-size adjusted BIC serve as a measure of the goodness of fit. Smaller values indicate a better fit. The entropy concerns the accuracy of assignment of respondents to the subtypes, with a value closer to 1 suggesting a more accurate classification. The LMR-LRT and the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test are direct tests of significance between models (e.g., 1 vs. 2 subtypes; 2 vs. 3 subtypes). Once a model reaches nonsignificance (p > 0.05), the model prior to the nonsignificant model is preferred (L. K. Muthén & Muthén, 2013). In addition to the statistical fit indices, substantive theory guided the identification of the most appropriate number and pattern of subtypes. At each step of analysis, the total number and pattern of subtypes were evaluated against Berry’s (1997) model and others whenever necessary.

After finalizing the subtypes, we used the Auxiliary (e) command in Mplus to describe the subgroups by the correlates. The Auxiliary (e) command uses posterior probability-based multiple imputations to determine differences in a given variable across latent classes without using that outcome to define latent classes (L. K. Muthén & Muthén, 2013). Owing to its probabilistic nature of class classification and determination in latent profile analysis, the observed class assignment is likely to introduce error into the analysis. Thus, to maintain the inherent probabilistic uncertainties associated with latent profile analysis, significant pairwise t- tests on the equality of means across classes (df =1), using posterior probability-based multiple imputations, were used to compare differences across the subgroups. Lastly, missing data were handled using maximum likelihood in Mplus. The rates of missing data were very low. The average missing rate was less than 1% and none of the variables had more than 5% missing rates. To compare associations between acculturation strategies and correlates, we used independent t-test or χ2 tests to examine statistical mean or proportion differences across the latent subtype groups.

Results

Explicating Subtypes

The fit indices are summarized in Table 1, which provide fit statistics for 1 to 6 subtype solutions by each group. For Filipino American youth, the 4-subtype solution showed the highest entropy (.999), suggesting high classification accuracy. AIC, BIC, and the sample-size adjusted BIC suggested a solution of 5 subtypes. The bootstrapped likelihood ratio test suggested more than 6 subtypes (p <.0001). However, LMR-LRT indicated that the 3-subtype solution (p = 0.0004) is significantly better than any other models. For Korean youth, the 3-subtype solution showed the highest entropy (.965), except the 6-subtype that included a subtype with n=4. AIC, BIC, and the sample-size adjusted BIC suggested a solution of more than 6 subtypes. The bootstrapped likelihood ratio test also suggested more than 6 subtypes (p <.0001). LMR-LRT suggested that the 5-subtype solution (p = 0.0018) is significantly better than any other subtype solutions.

Table 1.

Fit Indices of Latent Profile Analysis

| Filipino Americans | AIC | BIC | Sample-size adjusted BIC | Entropy | Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin Test | Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test | Sample Size of Smallest Subtype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Subtype | 4873.122 | 4920.372 | 4882.299 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 Subtypes | 4479.458 | 4554.271 | 4493.988 | 0.994 | 0.0460 | 0.0000 | 39 |

| 3 Subtypes | 4287.058 | 4389.434 | 4306.942 | 0.816 | 0.0004 | 0.0000 | 39 |

| 4 Subtypes | 3791.589 | 3921.528 | 3816.826 | 0.999 | 0.8624 | 0.0000 | 8 |

| 5 Subtypes | 3619.683 | 3777.184 | 3650.273 | 0.880 | 0.1224 | 0.0000 | 8 |

| 6 Subtypes | 4907.730 | 5092.794 | 4943.673 | 0.785 | 0.5018 | 0.0000 | 6 |

|

| |||||||

| Korean Americans | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| 1 Subtype | 5762.442 | 5810.635 | 5772.557 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 Subtypes | 5433.325 | 5509.631 | 5449.341 | 0.906 | 0.1121 | 0.0000 | 98 |

| 3 Subtypes | 5233.384 | 5337.804 | 5255.301 | 0.965 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 31 |

| 4 Subtypes | 5172.014 | 5304.547 | 5199.832 | 0.790 | 0.0441 | 0.0000 | 31 |

| 5 Subtypes | 5090.831 | 5251.478 | 5124.550 | 0.833 | 0.0018 | 0.0000 | 6 |

| 6 Subtypes | 3818.752 | 4007.512 | 3858.372 | 1.000 | 0.8358 | 0.0000 | 4 |

Note: The bold indicates fit indices for the chosen subtype for each group.

In addition to these fit indices, the nature of each group (i.e., of 3 vs. 4 vs. 5 vs. 6 subtype solutions) was evaluated in regard to six indicators that were used to generate the subtypes and against the theoretical models. We also considered the number of samples in each group to see whether each subgroup had reasonable sample sizes for post hoc comparisons on various correlates. For example, from the four-subtype solution, sample size of smallest subtype became less than eight for Filipino American youth. Thus, based on various considerations, we ultimately chose the three-subtype solution for both groups, as it seemed to best fit with substantive theory as well as the empirical fit indices. The three subtypes are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Latent Subtypes by Indicators

| Filipino Americans | Korean Americans | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Class 1 High Assimilation w/Ethnic Identity |

Class 2 Integrated Bicultural w/Strongest Ethnic Identity |

Class 3 Modest Bicultural w/Strong Ethnic Identity |

Significant Differences at p<0.05 | Class 1 Separation |

Class 2 Integrated Bicultural |

Class 3 Modest Bicultural w/Strong Ethnic Identity |

Significant Differences at p<0.05 | Ethnic Group Diff p<0.05 | |||

| Proportion (%) Sample size (n) |

100% n=379 |

45.4% n=172 |

44.3% n=168 |

10.3% n=39 |

100% n=410 |

7.6% n=31 |

74.4% n=305 |

18.0% n=74 |

|||

|

| |||||||||||

| Heritage Language | 2.55 | 1.73 | 3.27 | 3.14 | 1<2, 1<3 | 3.35 | 4.10 | 3.24 | 3.52 | 1>2, 1>3, 2<3 | FA<KA1 |

| English | 4.84 | 4.97 | 4.94 | 3.85 | 1>3, 2>3 | 4.59 | 3.02 | 4.92 | 3.93 | 1<2, 1<3, 2>3 | FA>KA |

| Heritage Culture | 2.68 | 2.13 | 3.17 | 3.01 | 1<2, 1<3 | 2.94 | 3.64 | 2.85 | 3.03 | 1>2, 1>3 | FA<KA |

| Host Culture | 4.27 | 4.46 | 4.16 | 3.89 | 1>2, 1>3, 2>3 | 3.9 | 2.93 | 4.05 | 3.72 | 1<2, 1<3, 2>3 | FA>KA |

| Ethnic Identity | 4.35 | 4.02 | 4.69 | 4.42 | 1<2, 1<3, 2>3 | 4.15 | 4.07 | 4.16 | 4.15 | FA>KA | |

| American Identity | 3.86 | 4.15 | 3.71 | 3.23 | 1>2, 1>3, 2>3 | 3.53 | 2.46 | 3.76 | 3.10 | 1<2, 1<3, 2>3 | FA>KA |

Note:

FA means Filipino Americans, KA means Korean Americans

Characteristics of the Subtypes by Indicators

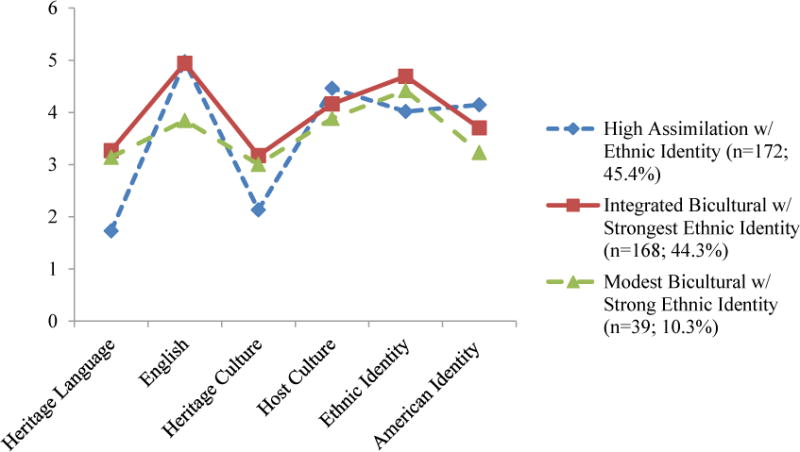

Based on their characteristics, we named the three Filipino American subtypes as (1) High Assimilation with Ethnic Identity (2) Integrated Bicultural with Strongest Ethnic Identity, and (3) Modest Bicultural with Strong Ethnic Identity. The high assimilation with ethnic identity was one of the two largest groups (45.4%, n = 172), reporting the highest host orientation and lowest heritage orientation compared to other two groups (summarized in Table 2 and Figure 1). Specifically, high assimilation with ethnic identity youth reported the highest English language competency, host cultural participation, and American identity but the lowest heritage language competency (1.73) and heritage cultural participation (2.13). Ethnic identity (4.02), although lower than among the other two groups, was still high in this group, comparable to their American identity (4.15). With this strong bicultural identity, this group did not squarely fit the traditional assimilation model, thus we added “ethnic identity” as a part of the name.

Figure 1.

Filipino American Youth Acculturation Strategy Profiles

The integrated bicultural with strongest ethnic identity (44.3%, n = 168) showed a high host cultural orientation that was fairly comparable to the high assimilation with ethnic identity group but a conspicuously strong heritage orientation that is higher than the high assimilation with ethnic identity but similar to the modest bicultural with strong ethnic identity (see below). Although host language and cultural participation were higher than those of heritage culture, ethnic identity among the integrated bicultural with strongest ethnic identity was noticeably higher (4.69) than American identity (3.71) and the highest among the three groups.

The third group, the modest bicultural with strong ethnic identity (10.3%, n = 39) reported modest bilingual competency and bicultural orientation with a strong ethnic identity. Specifically, this group reported lower host orientation in all three dimensions of language, cultural participation and identity, compared to the other two groups. Heritage orientation among this group was higher than in the high assimilation with ethnic identity group but lower than among the integrated bicultural with strongest ethnic identity. However, this group’s ethnic identity (4.42) was much stronger than its American identity (3.23). In all three groups, host orientation was stronger than heritage orientation with an exception of identity dimension. The prominence of strong ethnic identity among Filipino American youth led us to include ethnic identity in the name all three subtypes to highlight the vivid presence of identity enculturation even among highly assimilated youth. The mean of ethnic identity was in fact higher among Filipino American youth than Korean American youth (Table 2).

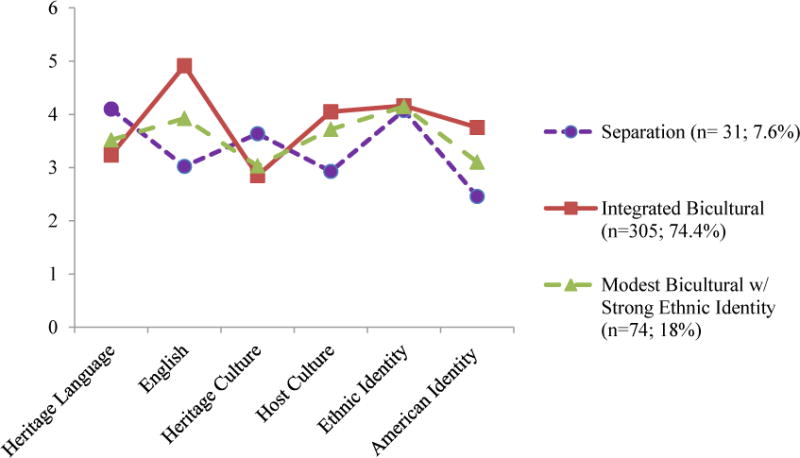

Among Korean American youth, we also identified three groups: (1) Separation (2) Integrated Bicultural and (3) Modest Bicultural with Strong Ethnic Identity, summarized in Table 2 and Figure 2. The separation group (7.6%, n = 31) was characterized by the lowest host culture orientation in all dimensions of language, cultural participation and identity, and reported the highest heritage culture orientation in language and cultural participation. Their ethnic identity (4.07), although not the highest among the groups, was quite strong, and showed the largest deviation from American identity (2.46), indicating a solid separation pattern.

Figure 2.

Korean American Youth Acculturation Strategy Profiles

The integrated bicultural group was the largest group in size (74.4%; n = 350), reporting the highest bilingual competence but also a stronger ethnic identity than American identity. Specifically, this group reported the highest English competency, host cultural participation, and American identity. Although heritage language competency (3.24) and heritage cultural participation (2.85) were lowest among the three groups, the means of these dimensions of heritage cultural orientation were around three out of a one to five scale. In addition, their ethnic identity was the strongest among the three groups. These characteristics when considered together seemed to fit integrated biculturalism.

Lastly, the modest bicultural with strong ethnic identity (18%; n = 74) was largely similar to the integrated bicultural in reporting stronger host cultural orientation than heritage cultural orientation, as well as a very strong Korean identity (4.15) that is much higher than American identity (3.10). While the pattern was similar (higher acculturation than enculturation) in the two groups, the overall means of acculturation among the modest bicultural with strong ethnic identity youth were lower than those of the integrated bicultural group.

Characteristics of the Subtypes by Correlates

Demographics

Summarized in Table 3, the modest bicultural with strong ethnic identity for Filipino American youth consisted of more boys (66.3%) than girls, the integrated bicultural with strongest ethnic identity consisted of more girls (67%) than boys, and the high assimilation with ethnic identity group was predominantly U.S.-born (88%) and had lived in the U.S. the longest. Parents of the high assimilation with ethnic identity had also lived in the U.S. the longest and were mostly U.S citizens (90%).

Table 3.

Comparisons of Correlates by Acculturation Strategies

| Filipino Americans | Korean Americans | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Names | Full Sample | Class 1 High Assimilation w/1 Ethnic Identity |

Class 2 Integrated Bicultural w/ Strongest Ethnic Identity |

Class 3 Modest Bicultural w/ Strong Ethnic Identity |

Significant Differences at p<0.05 | Full Sample | Class 1 Separation |

Class 2 Integrated Bicultural |

Class 3 Modest Bicultural w/ Strong Ethnic Identity |

Significant Differences at p<0.05 | Ethnic Group Diff p<0.05 |

| Proportion (%) Sample Size (n) |

100% n=379 |

45.4% n=172 |

44.3% n=168 |

10.3% n=39 |

100% n=410 |

7.6% n=31 |

74.4% n=305 |

18.0% n=74 |

|||

| Youth Demographics | |||||||||||

| Age | 15.28 | 15.19 | 15.36 | 15.41 | 14.76 | 15.42 | 14.79 | 14.41 | 1>3 | FA>KA3 | |

| % Boys | 44% | 49% | 33% | 66% | 1>2, 1<3, 2<3 | 52% | 71% | 50% | 55% | 1>2 | FA<KA |

| % US born | 71% | 88% | 61% | 41% | 1>2, 1>3, 2>3 | 58% | 20% | 67% | 40% | 1<2, 1<3, 2>3 | FA>KA |

| Years living in US2 | 13.29 | 14.57 | 12.69 | 10.09 | 1>2, 1>3, 2>3 | 11.78 | 5.93 | 13.03 | 9.22 | 1<2, 1<3, 2>3 | FA>KA |

| Parent Demographics | |||||||||||

| Age | 46.13 | 46.67 | 45.55 | 46.2 | 45.29 | 44.44 | 45.38 | 45.26 | FA>KA | ||

| Years living in US | 23.2 | 28.86 | 18.62 | 16.17 | 1>2, 1>3 | 16.03 | 7.41 | 17.90 | 11.84 | 1<2, 1<3, 2>3 | FA>KA |

| % US citizen | 80% | 90% | 74% | 51% | 1>3, 1>2, 2>3 | 49% | 27% | 57% | 27% | 1<2, 2>3 | FA>KA |

| % Permanent resident | 15% | 9% | 18% | 34% | 1<2, 1<3 | 34% | 27% | 32% | 45% | FA<KA | |

| Family Process | |||||||||||

| Core cultural values | |||||||||||

| Respect for adults | 4.09 | 3.96 | 4.23 | 4.13 | 1<2 | 3.85 | 3.52 | 3.88 | 3.86 | 1<2, 1<3 | FA>KA |

| Harmony & sacrifice | 3.81 | 3.70 | 3.95 | 3.74 | 1<2 | 3.81 | 3.54 | 3.84 | 3.76 | 1<2 | |

| Family obligation | 3.65 | 3.53 | 3.75 | 3.79 | 1<2, 1<3 | 3.62 | 3.24 | 3.64 | 3.69 | 1<2, 1<3 | |

| Boundary of the family | 6.32 | 6.18 | 6.64 | 5.58 | 1<2, 2>3 | 4.6 | 4.80 | 4.52 | 4.80 | FA>KA | |

| Indigenous family process | |||||||||||

| Traditional etiquettes | 3.77 | 3.13 | 4.34 | 4.23 | 1<2, 1<3 | 4.31 | 4.23 | 4.33 | 4.29 | FA<KA | |

| Gendered expectation | 2.85 | 2.53 | 3.11 | 3.16 | 1<2, 1<3 | 2.66 | 2.58 | 2.65 | 2.72 | FA>KA | |

| Academic parental control | 3.02 | 2.92 | 3.09 | 3.13 | 2.91 | 2.61 | 2.96 | 2.83 | 1<2 | FA>KA | |

| Qin | 4.13 | 4.05 | 4.24 | 4.00 | 1<2, 2>3 | 3.88 | 3.48 | 3.96 | 3.76 | 1<2, 2>3 | FA>KA |

| Parental affection | 4.24 | 4.19 | 4.34 | 4.06 | 2>3 | 3.94 | 3.47 | 4.01 | 3.86 | 1<2, 1<3 | FA>KA |

| Conventional family process | |||||||||||

| Authoritarian style | 3.36 | 3.19 | 3.50 | 3.47 | 1<2 | 2.95 | 2.59 | 2.99 | 2.93 | 1<2 | FA>KA |

| Authoritative style | 3.54 | 3.33 | 3.74 | 3.62 | 1<2 | 3.28 | 3.33 | 3.28 | 3.28 | FA>KA | |

| Parent-child bonding | 3.97 | 3.93 | 4.04 | 3.84 | 4 | 3.90 | 4.03 | 3.96 | |||

| Parent-child conflict | 2.44 | 2.48 | 2.44 | 2.27 | 2.22 | 2.25 | 2.23 | 2.17 | FA>KA | ||

| Parental acceptance | 3.8 | 3.79 | 3.86 | 3.60 | 3.75 | 3.56 | 3.80 | 3.63 | |||

| Parental rejection | 1.61 | 1.58 | 1.61 | 1.70 | 1.58 | 1.77 | 1.55 | 1.63 | 1>2 | ||

| Parent-child communication | 2.97 | 2.95 | 2.99 | 2.96 | 2.94 | 2.82 | 2.95 | 2.94 | 1<2 | ||

| Granting autonomy | 3.55 | 3.55 | 3.57 | 3.47 | 3.67 | 3.52 | 3.72 | 3.52 | 2>3 | FA<KA | |

| Parental rules | 3.77 | 3.56 | 3.89 | 4.23 | 1<3 | 2.81 | 1.87 | 2.94 | 2.68 | 1<2, 1<3 | FA>KA |

| Parental restrictions | 4.81 | 4.75 | 4.84 | 4.97 | 4.39 | 3.59 | 4.48 | 4.36 | 1<2 | FA>KA | |

| Immigrant family process | |||||||||||

| Emphasis on education | 4.7 | 4.64 | 4.78 | 4.57 | 1<2, 2>3 | 4.55 | 4.09 | 4.62 | 4.49 | 1<2, 1<3 | FA>KA |

| Cultural conflict | 2.6 | 2.37 | 2.79 | 2.84 | 1<2, 1<3 | 2.37 | 2.47 | 2.35 | 2.43 | FA>KA | |

| Pressure to succeed | 2.72 | 2.58 | 2.79 | 3.05 | 1<2, 1<3 | 2.45 | 2.19 | 2.47 | 2.45 | 1<2 | FA>KA |

| Embarrassed by parents | 1.78 | 1.62 | 1.91 | 1.93 | 1<2, 1<3 | 2.11 | 1.77 | 2.15 | 2.11 | 1<2, 1<3 | FA<KA |

| Racial/ethnic socialization | |||||||||||

| Cultural socialization | 3.64 | 3.11 | 4.12 | 4.02 | 1<2, 1<3 | 3.73 | 3.44 | 3.74 | 3.80 | 1<3 | |

| Promotion of mistrust | 1.51 | 1.37 | 1.63 | 1.64 | 1<2 | 1.5 | 1.56 | 1.49 | 1.51 | ||

| Preparation for bias | 2.14 | 1.97 | 2.33 | 2.08 | 1<2 | 2.13 | 2.07 | 2.18 | 1.98 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity Related | |||||||||||

| Racial discrimination | 1.36 | 1.28 | 1.43 | 1.37 | 1<2 | 1.5 | 1.55 | 1.49 | 1.53 | FA<KA | |

| Perception of white family | 3.18 | 2.92 | 3.42 | 3.30 | 1<2, 1<3 | 3.15 | 3.14 | 3.16 | 3.15 | ||

| Youth Outcomes | |||||||||||

| Depressive symptoms | 1.81 | 1.69 | 1.90 | 1.98 | 1<2 | 1.81 | 2.02 | 1.79 | 1.83 | ||

| School grade | 3.48 | 3.49 | 3.54 | 3.18 | 1>3, 2>3 | 3.54 | 3.42 | 3.57 | 3.48 | ||

| Antisocial behaviors | 44% | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 36% | 0.53 | 0.34 | 0.38 | FA>KA | ||

| Substance use | 25% | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 20% | 0.36 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 1>2 | ||

Note:

“W/” is an abbreviation of “with.”

The number of years living in the U.S. equals to one’s age among U.S.-born youth.

FA means Filipino Americans, KA means Korean Americans

For Korean American youth, the separation group primarily consisted of older youth (15.42 years old on average) and more boys (71.4% male), and the integrated bicultural group was predominantly U.S.-born (66.8%) and had lived in the U.S. the longest. Parents of integrated bicultural youth had also lived in the U.S. the longest. Parents of the separation group had more temporary visa holders (41.9%) than the other groups.

Family Process

Traditional core values

Among Filipino American youth, the high assimilation with ethnic identity group reported significantly lower rates in all variables of traditional core cultural values than the integrated bicultural with strongest ethnic identity group of youth (e.g., lower respect for adults, harmony and sacrifice, family obligation, and least expansive boundary of the family). Their family obligation was lower than the modest bicultural with strong ethnic identity. The integrated bicultural with strongest ethnic identity group reported the most expansive definition of family. Among Korean American youth, contrary to the expectation, the separation group reported lower rates in traditional cultural values; respect for adults, harmony and sacrifice, and family obligation were lower than the integrated bicultural group, and respect for adults and family obligation were lower than the modest bicultural with strong ethnic identity group. The boundary of the family did not differ among the Korean American subtypes.

Indigenous family process

The high assimilation with ethnic identity Filipino American youth group reported the lowest rates of traditional manners and etiquettes and gendered expectations among the three groups, and the integrated bicultural with strongest ethnic identity group reported the highest rates of qin among the three groups and stronger parental affection than the modest bicultural with strong ethnic identity group. These three Filipino American youth groups differed significantly only on the measure of academically oriented parental control. For Korean American youth, the integrated bicultural group reported the highest rate of qin, and higher academically oriented parental control than the separation group. The latter group actually reported lowest parental affection.

Conventional family process

The three Filipino American youth subtypes did not differ significantly on conventional measures of parent-child bonding and conflict, parental acceptance and rejection, parent-child communication, granting autonomy, and parental restrictions. However, the integrated bicultural with strongest ethnic identity group reported higher authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles than the high assimilation with ethnic identity. It is also noted that the modest bicultural with strong ethnic identity group reported higher numbers of parental rules than the high assimilation with ethnic identity group. The three Korean American youth groups were not statistically different in authoritative parenting style, parent-child bonding and conflict, and parental acceptance. However, the separation group reported the lowest number of parental rules and lower authoritarian style parent-child communication and parental restrictions, but higher parental rejection than the integrated bicultural group. The integrated bicultural group also had a higher rate of granting autonomy than the modest bicultural with strong ethnic identity group.

Immigrant family process

For Filipino American youth, the high assimilation with ethnic identity group showed marked differences in the immigrant family process variables. Specifically, they reported the lowest rates of cultural conflict with parents, pressure to succeed, and feeling embarrassed by parents among the three groups, while the integrated bicultural with strongest ethnic identity group scored the highest on emphasis on education. Among Korean American youth, the separation group reported the lowest rates of emphasis on education and feeling embarrassed by parents, and lower pressure to succeed than the integrated bicultural group. Cultural conflict was not significantly different across the Korean American subtypes.

Racial/ethnic socialization

The high assimilation with ethnic identity Filipino American youth reported the lowest level of cultural socialization. They also reported a lower level of promotion of mistrust and preparation for bias than the integrated bicultural with strongest ethnic identity. Conversely, the difference among the Korean American subtypes was found only in one variable, namely, the separation group reported a lower cultural socialization than the modest bicultural with strong ethnic identity

Race/Ethnicity Related

The high assimilation with ethnic identity Filipino American youth reported the lowest level of idealized perception of the White family. They also reported a lower level of perceived racial discrimination than the integrated bicultural with strongest ethnic identity. The Korean American subtypes did not differ in the levels of racial discrimination and idealized perception of the White family.

Youth Outcomes