Abstract

South Asia accounts for the majority of the world’s suicide deaths, but typical psychiatric or surveillance-based research approaches are limited due to incomplete vital surveillance. Despite rich anthropological scholarship in the region, such work has not been used to address public health gaps in surveillance and nor inform prevention programs designed based on surveillance data. Our goal was to leverage useful strategies from both public health and anthropological approaches to provide rich narrative reconstructions of suicide events, told by family members or loved ones of the deceased, to further contextualize the circumstances of suicide. Specifically, we sought to untangle socio-cultural and structural patterns in suicide cases to better inform systems-level surveillance strategies and salient community-level suicide prevention opportunities. Using a mixed-methods Psychological Autopsy approach for cross-cultural research (MPAC) in both urban and rural Nepal, 39 suicide deaths were examined. MPAC was used to document antecedent events, characteristics of persons completing suicide, and perceived drivers of each suicide. Patterns across suicide cases include (1) lack of education (72% of cases); (2) life stressors such as poverty (54%), violence (61.1%), migrant labor (33% of men), and family disputes often resulting in isolation or shame (56.4%); (3) family histories of suicidal behavior (62%), with the majority involving an immediate family member; (4) gender differences: female suicides were attributed to hopeless situations, such as spousal abuse, with high degrees of social stigma. In contrast, male suicides were most commonly associated with drinking and resulted from internalized stigma, such as financial failure or an inability to provide for their family; (5) justifications for suicide were attributions to ‘fate’ and personality characteristics such as ‘stubbornness’ and ‘egoism’; (5) power dynamics and available agency precluded some families from disputing the death as a suicide and also had implications for the condemnation or justification of particular suicides. Importantly, only 1 out of 3 men and 1 out of 6 women had any communication to family members about suicidal ideation prior to completion. Findings illustrate the importance of MPAC methods for capturing cultural narratives evoked after completed suicides, recognizing culturally salient warning signs, and identifying potential barriers to disclosure and justice seeking by families. These findings elucidate how suicide narratives are structured by family members and reveal public health opportunities for creating or supplementing mortality surveillance, intervening in higher risk populations such as survivors of suicide, and encouraging disclosure.

Keywords: suicide, low-income, psychological autopsy, depression, Nepal

Introduction

Globally, suicide kills more people than war, natural disasters, and homicides, accounting for more than 800,000 annual deaths (World Health Organization 2014). In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), however, accurate estimation of the burden is hampered by incomplete or non-existent vital surveillance systems (Nsubuga, et al., 2010; Setel, et al., 2007). South-East Asian countries are estimated to account for 39% of all global suicides, however none have a comprehensive vital registration system (Vijayakumar and Phillips 2016; World Health Organization 2014). This limits abilities to draw conclusions about patterns and risk in some of the world’s highest burdened countries (Mahapatra, et al., 2007; Rockett 2015). Nepal in particular has a complicated and unclear purported suicide burden (Hagaman, Maharjan, and Kohrt 2016). Although most prevalence studies have prioritized identifying relevant psychological correlates for suicide, LMIC scholars have argued that socio-political, environmental, and cultural factors may be just as important in the identification and prevention of suicide (Vijayakumar and Phillips 2016; Vijayakumar 2016). Therefore, combining both public health and anthropology elicitation strategies may be an important approach to understand the suicide burden in resource-strained settings, where such research is relatively rare and urgently needed. In settings such as these that have had limited surveillance compounded by potentially inconsistent and incomplete reporting, anthropologically-informed research is crucial to understand the cultural framing of suicide and factors influence reporting and responded. In this article, we (1) describe a novel mixed-method research approach for investigations into suicide (MPAC), (2) analyze thematically significant contextualized findings, and (3) outline their broad applications for the development of state and community level approaches to suicide prevention.

Cross Cultural Psychological Autopsy Approaches

Psychological Autopsy (PA) approaches have added valuable knowledge to the suicidology field (Clark and Horton-Deutsch 1992; Cavanagh, et al., 2003). PA are interviews conducted after a completed suicide with relatives of the deceased and other informants that are used to determine mental health status and exposure to risk factors contributing to the suicide. PA methods and implementation strategies have varied greatly both in content and study design (case-control vs. case-series). Typical PA approaches in high and upper-middle income settings use diagnostic instruments delivered by clinical professionals to proxy informants and determine psychopathology of the deceased and associated risk factors (González-Castro, et al., 2016; Bhise and Behere 2016; Chachamovich, Ding, and Turecki 2012; Portzky, Audenaert, and van Heeringen 2009; Cavanagh, et al., 2003; Phillips, et al., 2002; Isometsä 2001). Despite these important contributions, the dominant focus on mental illness, with its Western cultural models, limits broader theoretical development and more comprehensive understandings of suicidal behavior and death. Furthermore, obtaining reliable information from informants (typically family members) on psychological disorders and pathological history can be quite difficult in settings where explanatory models of mental health are diverse and heterogeneous including religious, moral, interpersonal and biomedical epistemologies. Recent theories attempting to better explain and predict suicidal behaviors reach beyond those rooted in psychopathology and depression. The Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide posits that feelings of burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and an acquired capability to inflict lethal self-harm must all be present in order for an individual to be at imminent risk of suicide (Van Orden, et al., 2010). There is also substantial literature linking emotion dysregulation and impulsivity to suicidal behavior (Horesh, et al., 1997; Anestis, et al., 2011; Rajappa, et al., 2012). Given emerging evidence on the importance of social and economic factors in suicide (Li, et al., 2011), research is needed to better understand the viability of these new theories across cultures and contexts. Therefore, in settings with limited engagement with mental health services, unknown validity and reliability of proxy assessment tools, and interest in domains outside of psychopathology, other methods are necessary.

Qualitative PAs conducted in Uganda revealed nuanced roles of female disempowerment, neglect, and lack of control in female suicides (Kizza, et al., 2012). Combining classic and qualitative approaches and expanding the focus beyond the individual into social-ecological domains has the potential to reveal important aspects of suicide risk and its aftermath. Additionally, providing opportunities for informants to discuss how suicide impacted them and their community in moral, political, and social realms allows insights into ways in which suicide shapes life among the living. We propose a mixed-methods Psychological Autopsy approach for cross-cultural research, which we describe below as a method to advance elicitation of such domains. Additionally, as recommended by PA scholars, increasing the domains of typical PA inquiry to include psychosocial factors, suicide disclosure and interpretation, and family history and social exposure to suicide allows the generation of new evidence for improved screening and prevention strategies.

This study aims to bridge public health and anthropological perspectives using the MPAC approach to better understand the socio-cultural context of suicidal deaths in Nepal and make salient recommendations for suicide surveillance, prevention approaches, and future research.

Anthropological contributions to suicidology

Straying from dominant psychological and sociological fields of suicide inquiry, anthropological works have offered rich insights into the local complexities and dimensionalities of such deaths. Anthropologists and other South Asian suicide experts have argued that suicide is inherently a social act, one that is inextricable from the local sociocultural and political milieu (Colucci and Lester 2012; Kleinman 2008; Eckersley and Dear 2002). Studies from low-income settings reveal how interpersonal conflict (Bourke 2003; Widger 2012b), female disempowerment (Canetto and Sakinofsky 1998; Canetto 2008; Widger 2012a; Marecek 1998), family and cultural histories of suicidal behavior (Widger 2015; Vijayakumar and Rajkumar 1999; Colucci and Lester 2012), and political injustices (Billaud 2012; Parry 2012; Chua 2009; Munster 2015) can deeply influence suicidality in the context of rapid global development (Chua 2014; Halliburton 1998). These works have emphasized the social meaning of suicide, where such acts are performative and respond to abuse, shame, revenge, or abandonment (Broz and Münster 2015). Furthermore, anthropologists have provided important critical perspectives on mortality ‘numbers,’ particularly in settings where systematic identification, classification, and documentation are not feasible (Nations and Amaral 1991; Scheper-Hughes 1997). For example, the WHO, the Global Burden of Disease studies, and Nepal’s Police System report very different suicide mortality estimates for the same year (World Health Organization 2014; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2016; Pradhan, et al., 2011). In 2014, agencies estimated 2012 overall national rates to be 24.9, 10.5 and 14.5 respectively. These numbers continue to shift dramatically as estimating procedures are updated (World Health Organization 2015).

Anthropological insights and interpretations are also well situated to make sense of how suicides involve, impact, and have lasting effects on families, friends, and communities of the deceased.

The need for a better understanding of suicide in Nepal

Nepal is situated between India and China, two countries with high suicide rates and atypical risk profiles vis-à-vis Western models (Phillips 2010; Vijayakumar, et al., 2008; Vijayakumar 2016; Bhise and Behere 2016).

However, Nepal has several distinguishing characteristics from its neighbors. First, over 500,000 Nepalis engage in migrant labor for employment (over 95% male), predominately in Malaysia and the Middle East (International Labour Organization 2016; Seddon, Adhikari, and Gurung 2002). Migrant labor carries opportunities for increased income, social mobility, and political agency. However, migrant work also carries significant risk to these aspects, as promised employment often fails and recruitment agencies cheat prospective employees. Second, cultural practices and beliefs (‘fate,’ ‘karma,’ and ‘social standing’) continue to dominate social expectations and interpretations of negative life events as well as certain types of mental illnesses (Desjarlais 1992; Kohrt and Hruschka 2010; Kohrt and Harper 2008). Women typically follow patrilocal tradition and arranged marriages, and young wives bear a large burden of expectations (Paudel 2007; Bennett 1983). Past research on suicide in Nepal indicates that suicide precipitants include lack of education, being married, poverty, and gender-based violence (Pradhan, et al., 2011; Singh and Aacharya 2007; Marahatta, et al.,). However, these findings are limited to women or to clinical-care settings so that little is known about male suicides as well as those that fail to emerge in the health system. Additionally, a recent five-country study found that Nepal community and clinical populations had high rates of suicide ideation, but the lowest amounts of ideation disclosure and help-seeking following an attempt (Jordans, et al., 2017). This underscores the importance of further research on why suicidal thoughts are not disclosed, as well as a better understanding of perceived drivers and meanings of suicidal deaths in Nepal (Jordans, et al., 2017; Jordans, et al., 2014; Pyakurel, et al., 2015; Marahatta, et al., 2016; Pradhan, et al., 2011).

Finally, according to a 2014 WHO report, Nepal ranked 3rd highest in the world for female suicide mortality and 8th highest for combined sexes – higher than both India and China. Recent data, however, illustrate a very different picture, reporting much smaller population rates (World Health Organization 2015). Nepal currently does not have an official vital registration system, and the Ministry of Health and Population does not reliably report on any suicide-related indicators (Hagaman, et al., 2016). As a result, numeric estimates remain uncertain and little is known about the political, sociocultural, and environmental factors related to suicidal behavior.

Anthropologically-informed findings are important for developing a better understanding of the sociocultural factors surrounding how suicide is framed and reported. In this article, using Nepal as a pilot example, we bridge public health and anthropological approaches in research design, data interpretation, and application in an effort to improve inquiries into suicide in LMICs.

Methods

This research was situated within a larger study aimed at understanding the cultural, institutional, and social factors contributing to suicide and implications for public health practice in Nepal [Blinded for review]. Our goal was to provide rich narrative reconstructions of suicide events, told by family members or loved ones of the deceased, to further contextualize the circumstances of suicide. Specifically, we sought to untangle socio-cultural and structural patterns in suicide cases to better inform systems-level surveillance strategies and salient community-level suicide prevention opportunities. We used a novel mixed methods psychological autopsy case-series method (Kral, Links, and Bergmans 2012; Arieli, Gilat, and Aycheh 1996; Conner, et al., 2005; Chavan, et al., 2008; Zhang, et al., 2009; Apter, et al., 1993) tailored for cross-cultural research, henceforth referred to as MPAC. This allows the informants (typically relatives) to share detailed accounts and interpretations of suicide circumstances including perceived warning signs, contributing factors, help-seeking phenomena, and the various impacts on the family and surrounding community (Shneidman 2004; Conner, et al., 2011). The analyses presented here focus on events and circumstances that preceded the suicide death.

Informant identification and selection

Following Zhang, et al’s cultural adaptations for the implementation and triangulation of the PA method in China (Zhang, Conner, and Phillips 2012), case identification and informant selection processes were designed to be sensitive to the Nepali context. As Nepal does not have systematic death reporting, we developed a census of all deaths reported to the police in the previous two years (2013 – 2015). We aggregated and extracted relevant information from identified suicide cases, as has been done in other PA studies (Kizza, Hjelmeland, et al., 2012; Kizza, Knizek, et al., 2012; Hjelmeland and Knizek 2016). We then created a list of all suicide cases in each sub-district location. From the total 302 suicide cases, we randomly selected cases to contact from one rural and one urban district, stratified by gender and for suicides occurring between 6 months and two years prior. Identifying information for case reporters (individual who reported the case to police) was used to contact the family, with help from local community leaders and Transcultural Psychosocial Organization-Nepal.

We selected informants who were 18 years or older, knew the decedent well (a family member or close friend that interacted with the decedent on a regular basis), and were comfortable discussing the events surrounding the suicide. If the initial case reporter preferred, they could suggest another family member to participate. To the extent possible, we interviewed more than one family member in order to triangulate narratives with multiple informants. MPAC interviews were conducted for 39 cases, aiming to meet saturation criteria (the point at which new interviews produce little or no change to existing themes) to stratify both by gender and urban/rural groups (Guest, Bunce, and Johnson 2006). A more detailed description of our sampling methodology for this Nepali study has been published elsewhere [Blinded for Review]

Instruments and Procedures

Data were collected between December 2015 and March 2016 in one rural district (Jumla) and one urban district (Kathmandu) in Nepal. In addition to the quantitative PA survey outlined by Shneidman and Appleby (Appleby, et al., 1999), we included a semi-structured qualitative section to explore locally salient contextual factors and lay theories regarding suicide in Nepal. The qualitative portion elicited detailed narratives surrounding the circumstances of the death, perceived causes, notable warning signs and suicidal communication, help-seeking behaviors, geographic movement, social networks, potential prevention strategies, and family coping and needs following the death.

Following informed consent, the MPAC protocol was conducted in-person by the lead author and one Nepali research assistant. These assistants were trained by the study team in project aims and methods, interviewing and active listening techniques, procedures for maintaining confidentiality, identifying need and initiating referral pathways, and other ethical aspects of the study. All interviews were conducted in Nepali, audio-recorded, and transcribed into English by the second author who received intensive training in transcription procedures and qualitative analysis. One of the two interviewers served as a note-taker, documenting notable aspects related to tone, context, emotion, and body-language. All linguistically and culturally significant Nepali words and phrases were preserved, particularly when English translation cannot adequately portray the appropriate meaning.

Analytic Methods

Our analysis focused on the qualitative data and sought to unravel familial perceptions, rationalizations, and explanations of suicide deaths from informant narrative reconstructions. Our quantitative MPAC findings are reported elsewhere [Blinded for review]. Qualitative textual data were analyzed in MaxQDA 12.0. A codebook was developed through an iterative process of reviewing the data and consulting local psychological experts. Deductive codes included topics from the survey such as alcohol use, stigma, and economic stress. Inductive codes included topics such as ijjat (social status), perceived shame, and relevant personality characteristics, such as ghamandi (egotistical). The first and second authors coded all interviews after establishing high inter-rater reliability (Kappa >= 0.70). When a particular code did not have high inter-rater reliability in initial checks, the code definition was revisited, revised, and recoded until agreement was high.

For this analysis, narratives were considered as both reflections of individual and cultural constructions of the suicidal event and as products of larger general trends and social discourse related to suicide in Nepal. Local narratives and experiences shape public health discourse, which then reshapes what is captured by health and legal institutions and, subsequently, how suicide is reported, ignored, and treated by the media (Chua 2014; Vijayakumar 2016). We recognize that these complicated processes mutually inform and reinforce how narratives are perceived, interpreted, and then retold or reframed for those that inquire. While it is not possible to clearly disentangle ‘facts’ from ‘scripts’(Canetto 2008; Stevenson 2012; Widger 2015), findings are meaningful because they reflect both individual and social perceptions and can provide important context to prevention efforts targeted for communities. Coded data were analyzed using techniques from content analysis (Bernard, Wutich, and Ryan 2016), identifying frequent and infrequently endorsed themes and developing thick descriptions. To assess the frequency of specific risk factors across all cases, we identified all named risk factors, warning signs, and perceived causes for suicide, and the presence or absence of each risk factor was determined for each suicide case and calculated as proportions. Interpretation of the data was checked and confirmed with all study members, authors, and TPO-Nepal staff in both field sites to ensure conclusions appropriately reflected local perceptions. All methods and results are reported according to the criteria for reporting qualitative studies–COREQ guidelines (Tong, Sainsbury, and Craig 2007) (see supplemental file).

Ethical Considerations

This project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of [Blinded for Review] and the Nepal Health Research Council. Additional permissions were granted by the National Nepal Police Headquarters and all relevant lower units. Researchers sought informed consent in Nepali from each participant before the interview. The participants were asked if they would like to read the consent form, or if they preferred the interviewer to read it to them. Participants were aware that they could refuse to answer any questions and stop the interview at any time. Literate participants provided written consent. Verbal consent was obtained when the respondent was not literate. Participants received no compensation for their participation. The study team and partner organization had a robust referral system established for survey participants endorsing distress. In these cases, participants were offered counseling and follow-up care.

Results

Suicide case sociodemographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and informant characteristics in Table 2.

Table 1.

Case sociodemographic characteristics.

| Characteristic | Suicide Cases n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Total (n=39) | Female (n=18) | Male (n=21) | |

| Age | 33.1 (Range: 14-79) |

26.8 (Range: 14-64) |

38.6 (Range: 14-79) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 26 (66.7) | 9 (50) | 17 (81.0) |

| Single | 9 (23.1) | 6 (33.3) | 3 (14.3) |

| Divorced/Separated | 2 (5.1) | 2 (11.1) | 0 |

| Widower | 2 (5.1) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (4.8) |

| Caste/Ethnicity | |||

| Brahman/Chhetri | 23 (59) | 9 (50) | 14 (66.7) |

| Dalit | 8 (20.5) | 5 (27.8) | 3 (14.3) |

| Janajati | 8 (20.5) | 4 (22.2) | 4 (19) |

| Religion | |||

| Hindu | 34 (87.2) | 15 (83.3) | 19 (90.5) |

| Buddhist | 3 (7.7) | 2 (11.1) | 1 (4.8) |

| Other | 2 (5.1) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (4.8) |

| District | |||

| Jumla | 20 (51.3) | 10 (55.6) | 10 (47.6) |

| Kathmandu | 19 (48.7) | 8 (44.4) | 11 (52.4) |

Table 2.

Informant characteristics

| Informants | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Female (n=11) | Male (n=28) | |

| District | ||

| Jumla | 9 | 11 |

| Kathmandu | 2 | 17 |

| Relationship | ||

| Spouse | 2 | 0 |

| Parent | 3 | 4 |

| Sibling | 2 | 12 |

| Uncle/Aunt | 2 | 9 |

| Close Friend | 2 | 3 |

| Age Group | ||

| 18 – 35 | 3 | 8 |

| 36-50 | 3 | 9 |

| 51-65 | 5 | 11 |

| Contact Frequency | ||

| Lived With | 10 | 8 |

| Multiple times /week | 1 | 11 |

| Multiple times /month | 0 | 9 |

The religion and caste/ethnicity of the deceased matched that of the informant. The majority of informants were male (71.8%), as they are often the public gatekeepers for the family. Additionally, 76.9% of the informants either lived with the deceased or met with them multiple times a week prior to the suicide. To illustrate common suicide narratives and the tendency for perceived suicide causes to be rooted in social issues, five stories are summarized in Textbox 1.

Textbox 1. Suicide Case Studies.

Maya (PA418)

Female, 14, Dalit, Rat Poison, Jumla

Maya was a student and worked as a domestic helper. She lived in a small house with nearly 20 other family members. She was Dalit, a discriminated ‘untouchable’ caste. Her father was physically disabled, leaving her mother in charge of both field work and housework. Maya had an affair with a married man. Her brother discovered this and beat the man. The police were called and Maya did not speak one word throughout the discussion. She was menstruating at that time and had to stay in a separate room. After returning home, she took her younger sister to a shop, bought rat poison, and consumed it. She was taken to hospital for treatment but after a few days, she died. Maya’s elder sister also had died by consuming rat poison six years before. Her mother explained that it was in her fate that both her daughters died, and says, “my youngest daughter, my only remaining daughter, she knows everything. Maybe it’s in her fate to die that way as well. I’m so scared of it.”

Min (PA403)

Male, 23, Janajati, Hanging, Kathmandu

Min and his family were very poor. In a desperate effort to make money, his family took a large loan to send Min to Malaysia for migrant labor. He was promised a comfortable job, but found himself working in extreme conditions without breaks. His employers abused him. He became seriously ill with a heart condition while in Malaysia, and his family scrambled to find the money to break his contract and return him home. After returning to Nepal, he drank alcohol frequently. He often fought with and beat his wife, and she soon left him. His neighbors blamed him for wasting his family’s money, for failing to find work, and for being unable to provide for his wife and son. He attempted suicide by hanging. His maternal uncle then stayed with him and watched him around the clock to prevent it from happening again. However, one week after his suicide attempt, he hanged himself. He wrote on the wall with a thin stick, “You left me. My life is meaningless. I won’t able to live in this place, so I am leaving”. His mother had died by poisoning herself about three years prior to Min’s suicide. Shortly after Min’s death, his father attempted suicide.

Pragya (PA412)

Female, 35, Brahmin, Hanging, Kathmandu

Pragya was married and had one son who lived in a boarding school. Early in Pragya’s marriage, she was worked tirelessly to support her husband to complete his schooling. When her husband started earning lots of money, he started to torture her, both physically and emotionally. He had affair with another woman – he never tried to hide it from Pragya. He demanded a divorce so that he could marry his mistress. Pragya’s in-laws tormented her as well, chastising her and blaming her for her failing marriage. One week before Pragya’s death, she was taken to the hospital and diagnosed with depression and given medications. She was forbidden from seeing her son, which tortured her the most. She died by hanging in her house. She left a suicide note that explained her husband’s affair, the abuse she endured, and her inability to see her son. “For these reasons, I choose to die,” she wrote. Her brother, our informant, cried that, “If she had instead written that she is not the type of person to do suicide, and that she did it because of her torture and abuse, I could have done something. But the police have a rule, if the suicide note states her own will to die, then they cannot pursue any criminal charges.”

Ram (PA425)

Male, 78, Brahmin, Drowning, Jumla

Ram grew up in a wealthy family in Jumla. He never had to work or worry about money and spent most of his time gambling. Following his father’s death, he felt a calling to be a priest (a typical profession in his family). He became the best priest in his district and was well respected. After his wife died, he floated between different sons’ houses, but was constantly bothered by their habits of drinking and laziness. He was persistently distraught and upset. “He wanted everyone to follow everything he said, he was really jiddi (stubborn),” his nephew (our informant) explained, “but his sons didn’t listen to him. He felt disappointed and unsatisfied with his sons and grandsons… He told others in our town that sacrificing one’s own body can earn us punya**. He started telling us, ‘death cannot take me, I’ve won death, so I will die.’ His nephew explained that after hearing these remarks, his family followed him everywhere and never left him alone. Ram killed himself in the large river downhill. He neatly folded his clothes, leaving his money and watch in a nearby tree.

Shanti (PA408)

Female, 56, Janajati, Hanging, Kathmandu

Shanti’s husband left her when their son was just 7 days old and married next woman. Her son had gone abroad for work and, during that time, she believed her daughter-in-law had an affair. After her Son returned to Nepal, Shanti endured physical abuse from both her son and daughter-in-law. They began to beat her so severely (often with the stone tool that was used to grind chili peppers), she started staying with her maiti (the house of her parents and eldest brother). She confided in her brother multiple times that she was terrified her son will kill her one day. “They won’t stop beating me,” she would cry. She was declared to have died by hanging in the verandah of her son’s house. Her brother, however, said it was murder, claiming that, “He (deceased’s son) used to threaten to kill my sister. I know he did that, both him and his wife. They paid the doctor to declare it a murder. They bribed the police. There is no way my sister would kill herself.” Her brother said that even now, his sister’s neighbors and some family members will not come into his home because they are nervous his family will involve them in a murder investigation. No one wants to get involved with the police, so they stay away from his home.

*All names are pseudonyms.

**A Hindu term with no English equivalent, generally it refers to notions of religious virtue, holiness, and righteousness. Doing good deeds will bring more material comforts in life, and can bring one closer to the gods.

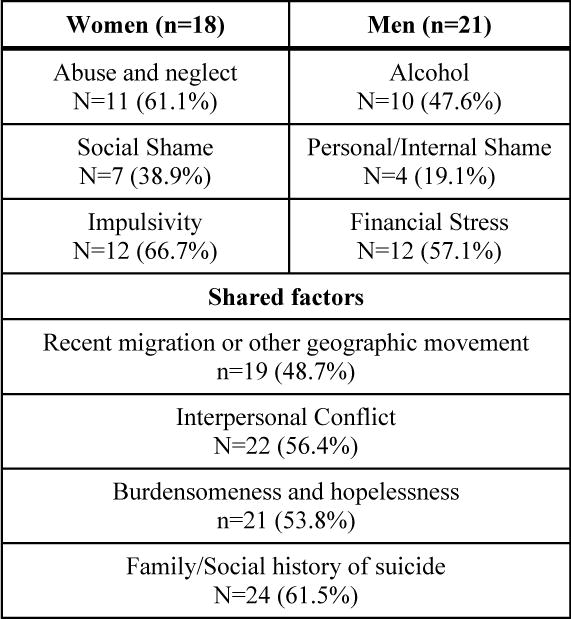

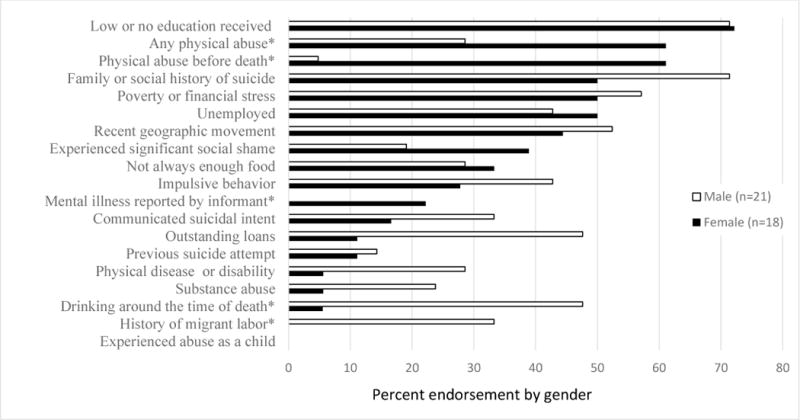

Several major themes emerged from textual analysis, providing contextualization to each suicide death. We identified four broad themes that were perceived to have significant effects on suicide events: significant life stressors, family histories of suicidal behavior, gendered drivers of suicide, and justifications for suicidal acts. We also highlight bureaucratic challenges and sociopolitical circumstances that affected how suicides were validated or challenged by families. See Figure 1 for an illustrative summary of the themes and Figure 2 for a summary of family-reported risk factors by gender. Almost three-quarters of the sample had low or no education and 53.8% had significant financial stress. Nearly 61.5% of suicides had a close relative or friend that died of suicide prior to the subject’s death. Family members reported that women were significantly more likely to have experienced physical abuse (61.1%) and have had a mental illness (22.2%) compared to men (4.8% and 0% respectively). Respondents were more likely to report men with outstanding loans (47.6%), excessive drinking around the time of death (47.6%) and a history of migrant labor (33.3%) compared to women.

Figure 1. Inductive Qualitative Findings.

Figure 2. Summary of endorsed risk factors by gender.

*Chi-squared tests were used to evaluate if there were group differences between men and women. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference between males and females.

Significant Life Stressors

Abuse, migration and other moves, interpersonal conflict, family histories of suicidal behavior, and prior suicide attempts or disclosures were common precursors to suicidal behavior. These events are further compounded with poverty and pressure to uphold familial and social obligations.

Abuse

Varying aspects of abuse were described in 43.6% of the cases. For men, abuse came from an employer, drunken fights, or working conditions. For women, abuse resulted from many different sources including a husband or partner, in-laws or paternal family, or her general community. Several family members blamed the abuse to be the direct cause of female suicide and found it difficult to classify either as indirect murder or suicide. However, male abuse was not described to be a direct motivator for suicide, but it did contribute to overall shame – damaging the ijjat (social status) – and often lead to desperation to escape social judgement and subsequent family shame. Female narratives contained many variations of abusive circumstances that ranged depending on marital status and age.

A few narratives mentioned emotional or physical abuse from in-laws; however, much more common was physical abuse from the husband. Domestic abuse was often described as something common and usually only affected the wife, not the children. A friend and neighbor of a woman that died by suicide described, “She told us [her neighbors] that her husband didn’t let her live happily, eat happily…that he tortured her, he beat her every day. After she drank the poison and she was in the hospital she told us that she couldn’t take his abuse, so it’s better to choose death. She didn’t tell the police that. Only her neighbors” (PA420, 28, Female, Jumla). Domestic abuse towards women often co-occurred with the husband’s excessive alcohol intake. In another case in Kathmandu, the deceased’s brother described her marital problems:

“My sister had only one ‘tension’, she struggled so much in life for one person (her husband), and she had so much dukha (sadness). It was an arranged marriage. There was a big gap in finances between her parents and her in-laws. She had to sell tea on the roadside. Her husband made good money, but he forced her to struggle alone, isolated. He was ashamed to have her as a wife, so he started drinking alcohol and tortured her. He told her he wanted to marry a better woman. He took her son away from her, she was so sad and so isolated and always beaten…what could we do? If someone is in that situation, there is nothing else they can do. She had no hope, it was best for her to choose to die.” (PA412, 35, Female, Kathmandu)

Migration and other geographic movement

Recent household moves emerged as an important warning sign across many cases. For women, moving away from a maternal household often preceded the suicide. Following a divorce from an abusive and adultering husband, one informant explained her sister’s frequent movements leading up to her suicide:

“After her divorce, she lived with our grandparents. Then she shifted to our brother’s house in the east. She came to Kathmandu to study, she insisted on it, but she really struggled to get high marks. She lived with me and my husband. We wanted her to stay, but she demanded on living alone and rented a room. She had such a big ghamanda (ego), she was so jiddi (stubborn). I think she feared what others would think after her divorce. She freed herself from his torture, but she still had torture in her mind. Our mom stayed with her for the first 10 days when she moved into the single room to give her comfort, but soon after mom left, my sister killed herself. I should have known…because she wanted to be alone so much.” (PA406, 21, Female, Kathmandu).

In Jumla, many of the young cases involved early ‘love marriages’ (marriages that were not initiated or arranged by the family). In one case, the young woman was about 17 when she married and was still in school. Her in-laws explained that, “she had only been in our home for three days. She would go back to her maiti (maternal home). She was there for three months after their marriage. When she came to live here, she was really quiet. She didn’t do anything. Didn’t talk to anyone. She went back to her maiti again and killed herself there.” (PA428, 18, Female, Jumla)

For men, migrant labor or moving for school were two important events that often occurred shortly before death. Geographic movement was required for migrant labor, a sought-after economic option for many families. After returning home, men struggled to find work or properly reintegrate with their family, experiencing haunting notions of failure, shame, and often turning to drugs and alcohol to cope. A young man’s father described his son’s trouble to find consistent and bearable work:

“He had a love marriage and his wife sold her gold necklace to get the money to send him to India. He went to Bombay and phoned her often, complaining about the miserable heat. So, he came home. Then, he went to work in Dubai, but his salary was not enough. He was unhappy, so we told him to come home and he can try going to a different country. We paid a middle man to get him a visa for Jordan, but that man was a crook. He was so restless, so unsatisfied, and so worried. He felt like a burden, even though we [father, mother, brother] told him he should not worry about that. While we were waiting for another visa, he hung himself.” (PA421, 30, Male, Kathmandu)

Young men were also sent away to study, in hopes of attaining high marks and getting a good job. The aunt of a 22-year old boy described his school failure:

“His father sent him to Kathmandu hoping to could receive a better education. After he got there, he made bad friends. He became mischievous. They drank and did drugs. Nobody could control him, we thought Kathmandu turned him bad. His aatmaa (soul) turned weak. We spent a lot of money on that school, but we had to bring him back to Jumla. Soon after he returned here, he got in trouble with the police. The day before his court date, he did suicide.” (PA441, 22, Male, Jumla)

Although movement was not described to explicitly contribute to the suicide, its occurrence was consistent, common, and close to the time of the suicide, emerging in about half of the interviews. Moreover, moving away from the individual’s own house and family was often discussed as something dangerous and stressful to the deceased.

Interpersonal Conflict

Individuals were often defined by their relationships with others. Negative conflict was particularly salient and figured prominently in perceptions of suicide causality. Family and spousal conflict preceded many suicides and were typically related to either (1) financial issues or (2) alcohol. A young widow described her husband’s suicide and the constant bickering with his mother: “His mom had a bad habit of fighting with him. She always nagged him, she had a very hot head. So her son was like that too. The day he died, she had been fighting with him about how his schooling had finished all the money. It wasn’t very different from other fights. But that day, he drank poison.” (PA439, 23, Male, Jumla).

Chronic family disputes outside marriage were also cited as contributing to the choice of suicide. Often, in younger male suicides, fights, frustrations and arguments with parents were said to cause anger that resulted in suicide. Disputes resulted from arguments over money, poor performance in school, or prohibited love relationships. Some were constantly distraught by a seeming unacceptance from their parents. A brother described his sister’s suicide resulting from her mother’s disproval of her marriage to a Dalit man: “There was a lot of gossip about that. A lot. And my mother gossiped about it…she never forgave my sister for that. And that devastated her. And she tried everything to show my mother how much she loved her. She tried many ways. But my mother never accepted her because she married a low caste. That devastated her.” (PA414, 39, Female, Kathmandu).

Daughters-in-laws were often subject to harsh blame and criticism from their in-laws. In two female cases, the in-laws blamed her personality and poor decisions for the suicide (see shame section below for additional examples). Spousal conflict was commonly described, particularly when one or both individuals drank. Both men and women fought over accusations of love affairs and unpaid loans, until the bickering became unbearable for one. One father-in-law explained his daughter-in-law’s role in fights, “She had gotten so uncontrollably angry, so I tried to unite them once after a big fight they had. But the deceased said she will not live together with her husband anymore, she wanted to live alone. She used to say this straightforward to her husband, she never respected him.” (PA410, 25, Female, Kathmandu). This example demonstrates both spousal issues, as well as the types of judgements placed on the daughter-in-law.

Family History of Suicidal Behavior

In the majority of cases, repeated suicides within the family or close social network were described (61.5%). Multiple family suicides were often within one or two generations, occurring among members of the same household. The aunt and uncle of a 16-year-old girl had assumed guardianship over her and her sister after their mother died by hanging. Her uncle explained, “We assumed that she might had thought that her mother also died by hanging so why should she live. Just after her mom died, she tried to kill herself. We took her to the hospital, and she took medicine for depression. The doctor told us not to scold her… we didn’t do anything to her, we loved her so much. But she tried again and died.” (PA434, 16, Female, Jumla). The case studies in Textbox 1 elaborate two examples of the contagion pattern (Maya and Min). Multiple family suicides were perceived to be ‘fated’ or learned and rarely linked to mental disorders. This is further outlined in the section below.

Prior Suicide Attempts and Disclosure

Suicide narratives did not commonly endorse previous suicide attempts among the deceased. In the four (13%) who did, attempts were followed with some family-based preventative measures (e.g., never leaving an individual alone). The uncle and permanent guardian of a 16-year-old girl explained, “She used to live with her father and sister. Her mother died by hanging in that house. So, we cleaned that house and I don’t know what had happened, but she tried to hang herself there. That was also seen by her sister, so we brought her to our house to stay with us. We thought that was better, so we sent her father to an alcohol rehabilitation center and brought his two daughters with us in our house” (PA434, 16, Female, Jumla). This family had taken the deceased to the doctor following her first hanging attempt and she was treated for depression. In only one case was an attempt mentioned as a performative threat meant to attract attention from family members, but this was also in the context of several failed attempts for the deceased to earn money, leaving him feeling hopeless: “He felt like a burden on his family, I think. Before going abroad, he tried (suicide) once and again after returning from abroad, three times total...He took sleeping pills. He would say, ‘I can’t read, I can’t do any work, why should I live being a burden?’… I think, the time he died, he thought he would tie the rope and mom would see him and she would give him money. All those times, he was trying to threaten her.” (PA415, 25, Male, Kathmandu).

Gendered Drivers of Suicide

Shame and social status

Shame (laaj) played a complex role in explanations for suicide deaths and was typically discussed indirectly through narratives and passive comments. Shame was agentive in different ways for men and women. Shameful situations for women typically placed individual blame or fault directly on her. For women, shame was often inflicted by the community and attributed to a ‘mistake’ made by the deceased. For example, several women were described as being involved in forbidden love relationships, for marrying at a very young age, or not studying enough for school. One young girl died of suicide at 19. Her mother described that she had wanted to marry a neighbor’s son, but the boy’s mother had publicly decried the relationship, yelling that she would kill herself if her son married her. The deceased’s mother explained that her daughter could not endure the personal shame and subsequent family shame from this woman, despite her attempts to persuade her otherwise. Situations like this usually damaged the ijjat (social status) of the woman in the community, devaluing her worth and purity. Subsequently, the iijat of the family might also be threatened and push her further towards suicide to escape bearing the burden of the community’s stigma. An uncle explains his niece’s intense feelings of burdensomeness, “There was a note which we found after her death. When I talk about it, tears come from my eyes now also. The note said, ‘My mother already died and why should I trouble to many people, my dimaag (brain-mind) had stopped working, how much should I trouble to aunt and uncle also’. I found that note later.” (PA434, 16, Female, Jumla)

Male suicides were rarely directly connected to one particular shameful event. Circumstances that brought shame for men were typically related to broad situations that were characterized as being out of the man’s immediate control (e.g., crops failing, general situations of poverty). Such situations were described as something men had little direct control over, but that perhaps contributed to larger feelings of failure, inadequacy, and burdensomeness. While these situations contributed to internal notions of failure and shame, respondents found it very difficult to point to one reason for a male’s suicide (female explanations, however, came with comparative ease). Men were described as feeling like a failure because of financial burdens or an inability to succeed economically. Compared to older decedents, younger individuals – usually sons that families relied on economically – were more often described as being stressed about finances. This sort of failure in males often led to alcohol abuse, perpetuating feelings of shame and damage of one’s ijjat, particularly amongst Brahman men where social standing and purity are highly regarded. One son explained how confused they were following his father’s suicide: “He had loans, it was stressful, but it didn’t cause fights. He drank alcohol all the time, but he never made fights with anyone. After he died, everybody was surprised, ‘how could such a nice and good person do suicide? Why did he do that? he shouldn’t have.’ That’s what all the neighbors said.” (PA29, 57, Male, Jumla). Despite descriptions of men enduring difficult working conditions, failed attempts at monetary gain, and interpersonal struggles, respondents did not directly attribute the loss of ijjat or specific shameful circumstances to male suicides.

Alcohol

A common factor involved in both male and female suicides was alcohol consumption and its sequelae, including financial loss, increased stress, shame, violence, and disability. Nearly half of the deceased men were reported to have alcohol problems that greatly contributed to their suicide. The uncle of a deceased Jumli man explained his death:

“He drank every day. He would go to work in the morning and then drink in the bazaar. He didn’t drink in front of us, but sometimes he would fall down and we would get called to carry him home. When he was drunk, he beat his wife and children. He used to shout at us too. Eventually, to avoid the violence, his wife and kids slept in a neighbor’s house. There was so much tension in the evenings, but come morning, it would be fine. That day he died, he was drunk as usual, and tried to beat his family, so they went to the neighbor’s house. He went inside his house, closed the door, and did suicide. We didn’t know anything. Was it because he was paagal (crazy) or was it because of the alcohol? All the neighbors say that if he hadn’t drunk alcohol, he wouldn’t have done suicide. They said it was his bhaagya (fate).” (PA431, 46, Male, Jumla)

In many male cases, the deceased was drunk at the time of death, and this was perceived as accounting for the ability to perform suicide, something that a sober man was not able to do. Alcohol was commonly blamed for negative family relationships, poverty, and abusive behavior: “When he didn’t drink, he was like a God. But after drinking, he would shout, he would fight, he would beat his family” (PA405, 53, Male, Kathmandu). Alcohol then, deflected blame from the individual.

Not only was alcohol endorsed as a precursor to suicidal behavior of the one drinking, but it was also blamed for causing the suicide of another family member. In three female cases, the husband’s alcohol consumption was reported to be a main cause of her suicide. While the amount consumed was often unknown, Jumla informants explained that men spent any available cash on alcohol, causing domestic fights, perpetuating poverty, and sustaining a sense of hopelessness for the whole family. The wife of a deceased Jumli emotionally explained, “There was no limit for him. Here it is not measure in mL, it is measured in gallon, however much he can drink, is how much he will buy. Sometimes he spent 1000 rupees, sometimes 2000, 3000. However much he had, he would spend. He wasted all our money.” (PA437, 48, Male, Jumla). Several young men (five under 30 years) were described as addicted to alcohol, perpetuating their emotional despair.

Justifications for and Contestations against Suicidal Acts

While many family members endeavored to explain why the suicide happened, most were surprised when they discovered the deceased’s body. A common reaction was fainting or not remembering any events from the day of death. Particularly if there was no identifiable preceding event – such as a family fight or a break up – families were unable to rationalize suicidal behavior and were left with intense distress. Particularly in these cases, suicidal actions were ascribed to the concept of bhaagya (fate) – something that no individual could prevent. Common idioms used to describe fate’s role in suicide are outlined in Table 3. Personality types and specific characteristics frequently emerged in explanations and descriptions of the deceased. Inflexible personality types, including overwhelming pride, stubbornness, and uncontrollable or impulsive anger, became typical descriptors and often ways of justifying suicidal behavior. A sister explained, “If she [deceased] could have controlled herself (afulai niyentran gareko), her death would not have happened.” Finally, in two cases, informants believed the death to be a homicide (all cases had police investigations confirming the death as suicide). Families, however, were unable to formally contest these cases. Challenging homicide accusations with the police required monetary capital and a certain amount of ‘power’ in order to publicly disagree with the police. Other suicide deaths were attributed to underlying chronic abuse, and informants expressed distress about labeling it ‘aatmahatya’ (suicide), considering ‘hatya’ (murder) to be more fitting. One brother explains his skepticism over his younger brother’s death, “I think the doctors didn’t want to make it an issue – if they say it was not suicide, it might bring them trouble. So, they said it was a suicide…but how could they do that? They didn’t listen to what I said, nothing I said mattered. With the police, I thought I might contend the death, but then I thought that my nephew no longer has a father – so how I can accuse my sister-in-law of murder? They had so little money, so I left it. I never did anything.” (PA423, 39, Male, Kathmandu). See Shanti’s case in Textbox 1 for another detailed example.

Table 3.

Personality and fatality terms used to describe the deceased.

| Personality Characteristics | Descriptions of Fate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Nepali | English Translation | Nepali Devanagari | English Translation |

| घमंडी Ghamandi |

Proud, egotistical | भाग्यमा जाती लिएर आएको छ, त्यति नै हुन्छ Bhaagya ma jati liyera ayeko chha, teti nai hunchha |

They will have only as much as their fate gives them, no more. |

| छिटो रीस उठयो Chhito ris uthyo |

Becoming angry fast, unable to control emotions | भाग्यमा लेखेको कुरा बदल्न सकिदैन Bhaagya ma lekheko kura badalna sakidaina |

One cannot change what was written in their fate |

| जिद्धी Jiddi |

Stubborn | भाग्य मै त्यति लेखेको रहेछ Bhaagya ma teti nai lekheko rahechha |

It was written in fate. |

| मुर्ख Murkha |

Foolish | त्यस्तै भाग्य लिएर जन्मेको रहेछ Testai bhaagya liyera janmeko rahechha |

They were born with such fate |

| जड्याहा/रक्स्याहा Jadyaaha/raksyahaa |

Drunkard | ||

| रीसाहा; कडा रीस Risaaha; kadaa ris |

Bad tempered | ||

| आफ्नो भबिस्य अंधकार देख्यो Afno bhabisya andhakaar dekhyo |

Pessimistic (seeing future as dark) | ||

| आवेगशील Aabegsheel |

Impulsive | ||

Discussion

Through use of culturally adapted mixed-methods psychological autopsy, we were able to elicit important and nuanced perceived drivers of suicide in a systematic way. This study revealed important patterns across suicide cases in the Nepali context, many of which may be useful in building suicide detection and prevention efforts. Specifically, family histories of suicidal behavior emerged in 61.5% of the cases, with the majority involving an immediate family member’s suicide. Female suicides were often attributed to hopeless situations such as spousal abuse or shame due to failed relationships and ensuing community blame. In contrast, male suicides were commonly associated with drinking, an action driven by failures to meet social expectations, such as financial failure or an inability to provide for their family. Significant life stressors such as poverty, violence, migrant labor, and family disputes often resulted in isolation and a weakened aatma (spirit). These aspects contributed in complex ways to suicide deaths. Inductive data analysis revealed potentially important warning signs that may better inform screening and prevention efforts (see Applications section below). These included recent geographic movement, alcohol use in the home, and family histories of suicide. Our results can be further contextualized within the larger suicide literature from LMICs, applicable suicide theory, and pragmatic implications for the prevention of suicide in resource constrained settings.

Gender implications and moral attributions in LMICs

Our findings that, for women in particular, a sense of hopelessness and despair related to domestic violence and social shame seemed to leave no other perceived option except suicide has been similarly documented in India (Gururaj, et al., 2004; Vijaykumar 2007) and is in line with the previous suicide research in Nepal (Pradhan, et al., 2011). In Uganda, female suicides were framed as a response to family-based stressors combined with a lack of social support and immediate availability of means (Kizza, Knizek, et al., 2012). Other studies from Asia have shown that female suicides are less planned and are a response to an acute stressor (Zhang, et al., 2009). While other literature has indicated that female suicides were driven by a desire for revenge, particularly in India (Marecek and Senadheera 2012; Marecek 1998; Meng 2002), the 19 cases we studied rarely indicated women using suicide as a performative action. However, this was the case for several of the male cases in our sample. The female narratives can be more broadly situated within issues related to strict social expectations, particularly of immediate family members. Abuse, family conflict and subsequent shame that women faced, combined with their lack of agency, was perceived to be a fatal combination. In Nepal, an individual and family’s iijat (social status) is important to maintain. For women, if her iijjat is stained, she may endure significant blame from her family and community, leading to isolation and desperation. Similar findings regarding female suicide and aspects of moral judgements from society have emerged from Sri Lanka and elsewhere (Marecek and Senadheera 2012; Canetto 2008; Honkasalo and Tuominen 2014). These findings highlight the importance of considering how stigma and shame, coupled with a lack of other coping options, have meaningful effects on suicidal behavior and should be considered in the development of prevention programs. Importantly, recent literature has highlighted gendered aspects of suicidality that confront previous Durkheimian claims. In India, Chua argues that common female performances of suicide (colloquial discourse, threats, and attempts) suggest that increased suicide rates in Kerala are not due to increased individualism as a byproduct of globalization (Chua 2014). Instead, female suicide narratives support that suicide results often from an obligation to others in so far as suicidal performances seek to pull families closer together. The current study found many parallels to this in Nepal, however, many of our findings suggest that male narratives, more often than female, supported the idea that an act of suicide was in some aspect an effort to fulfill obligations or ease burdens on family members.

The geographic movement patterns and stresses related to migrant labor that we uncovered for male suicides have not been discussed much in the literature, but may serve as an important indicator deserving further exploration. A study from India found that a large proportion of male suicides were migrant workers, many Nepalis (Chavan, et al., 2008). As a high period of vulnerability, migration factors has played an important role in veteran, refugee, and other migrant suicides (Otsu, et al., 2004; Hagaman, et al., 2016; Schinina, et al., 2011), and may also be the case particularly for populations that have large amounts of migrant labor, such as Nepal. In our results, returned migrant workers had a difficult time reintegrating, often facing conflict with their spouse or experiencing shame due to failure to make money abroad. This is another example supporting the saliency of notions of thwarted belongingness and burdensomeness and the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. A PA investigation in India found that 60% of the suicides were migrants from other states or outside countries. Of international migrants, the largest proportion were from Nepal (Chavan, et al., 2008). Further investigation into the effects of migrant labor and (dis)integration on suicide is warranted in LMICs.

Emotions and avenues for application within suicide theory and intervention

Within the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide, feelings of burdensomeness on one’s family and community (as discussed above) is believed to be an integral component of suicidality (Van Orden, et al., 2010). Our findings provide some initial support for the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide in the Nepali context, particularly the concepts of burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. In settings where mental health services are limited, pulling on concepts outside of psychopathology to predict suicidality holds much promise.

Informants regularly discussed that most of the deceased were unable to control their emotions, often letting anger and impulsive responses overwhelm their actions. Descriptions of deceased’s patterns of anger and inability to control one’s emotions is supported by previous literature theorizing that suicide is anger turned inwards (Widger 2012a; Rudd, et al., 2006; Conner, et al., 2003). Emotion dysregulation and a lack of effective coping strategies has also been linked to an increased risk in suicidal behavior (Rajappa, Gallagher, and Miranda 2012). Recent suicide theories assert that acquiring the capability to inflict lethal self-harm, often gained by engaging in risky behavior, is one important component for severe suicidality (Joiner Jr, et al., 2009; Van Orden, et al., 2010). Demonstrations of anger, risky behaviors (such as alcohol consumption), and experiences of fear and abuse that emerged through our study may fill this criterion and be important factors to consider in treatment. Studies from other low-income settings have found similar patterns of risky behavior (Kizza, Hjelmeland, et al., 2012; Mugisha, et al., 2011; Kizza, Knizek, et al., 2012; Hjelmeland, et al., 2008). In our sample, suicides were overwhelmingly stated as unplanned, even when there was a previous attempt or discussion of death. This might suggest that, in Nepal, suicides are perceived as singular events that are not connected to previous behavior or actions beyond events close to the time of death. This further supports perspectives that impulsivity is seen to be more closely connected to suicidality than previous attempts or mental illness. Such findings can help inform the adaptation of education and prevention programs, particularly those targeting emotion regulation, which have been culturally adapted for Nepali and Bhutanese populations (Kohrt, et al., 2012; Ramaiya, et al., 2017).

Familial responses, death relationality, and the interplay with suicide scripts

As one aim for this study was to better link suicide research within local cultural frameworks and provide richer pragmatic recommendations for suicide prevention, we were particularly interested in how families understood, described, responded, and made particular claims related to the death of their family member. In our findings, families often described the suicidal death in relation to broader social and spiritual forces. Many suicides, particularly cases where a rational explanation could not be easily determined, were seen as fate or destiny. This limited the deceased’s personal agency in the action. Similar patterns have been found in explanations for suicide in Russia (Broz and Münster 2015) and Haiti (Hagaman, et al., 2013). In Sri Lanka, fate was also used to relieve notions of agency among suicide attempt survivors in order to preserve their karma and social status (Broz and Münster 2015). In cases where multiple suicides happened within one family, fate was also used as an explanation. While the suicide literature has evidence of genetic and social contagion components (Brent and Mann 2005), this study found few such endorsements. Importantly, eliciting perceived causes for suicide is complex and somewhat problematic. Hawton, et al (1998) suggest eliciting ‘life problems’ by first determining if the problem existed (e.g. relationship problems, divorce, unemployment) and secondly, whether it was judged to have contributed directly to the suicide (Hawton, et al., 1998).

In our study, family members endorsed that many problems existed, but rarely judged them to contribute directly to the suicide. This could be due in part to tropes or ‘suicide scripts’ that exist in particular cultures (Canetto 2008). For example, in our data, trouble with money and unemployment were often cited as problems, but not to be directly connected to the cause of the suicide. However, things like bad relationships or fights between family members often were believed to have caused the suicide. Such findings speak to the mutuality of death interpretations with larger social tropes attributed to suicide. Livingston highlights how suicides in Botswana are deeply intertwined with larger economic trends and individual aspirations, particularly in the context of love and social expectation. Similarly, Chua (2014) describes youth suicides and female suicide threats as reflections of promised, but failed, aspirations in a rapidly developing Indian State. These findings point to the importance of not only eliciting individual or local experiences of distress, but considering multi-level analyses and contextualization that can better capture broader social and state-driven risk factors for suicidal behaviors. Moreover, higher levels of ethnopsychology are equally important to consider. Straight, et al., (2015), working alongside multiple pastoral communities in East Africa, found that community orientations towards suicide must be considered among other forms of death. They argue that deep ethnographic community engagement is essential for both useful inquiries into suicide and the production of effective interventions (Straight, et al., 2015). This highlights the importance of using qualitative components to better bridge cultural models with suicide inquiry and analysis and, ultimately, to better interpret informant responses and form appropriate prevention suggestions.

Finally, the bureaucratic processes and categorization of suicide adds complexity to both perceived causes of suicide, as well as the ability to dispute the legal declaration of a suicide death (Hagaman, Maharjan, and Kohrt 2016). In cases where a death was believed to be caused by a spouse or family member (e.g., an abusive husband drove a wife’s escape through self-killing); claiming the death a suicide was fraught. Such deaths were considered a product of other illegal activity that abetted the suicide. This obfuscates the categorization of death, blurring lines between murder and self-inflicted death. Indeed, to assuage distraught families, the Nepali government is seeking to implement a new law to make prosecution possible in such situations. Additionally, some families wished to dispute the declaration of a suicide, but lacked the resources, time, and agency to fight police conclusions. This underscores the difficulty of (1) untangling risk factors in situations of severe social distress, female disempowerment, and abuse and (2) helping families and social networks of the deceased process their grief and find justice. More work is needed to further disentangle the legal complexities of sensitive and violent deaths, particularly in low-income and inequitable settings.

Applications

Although other larger PA case-control studies have been able to make population-level generalizations, our richer qualitative data on cultural understandings of suicide have unique potential to inform a host of prevention activities that quantitative studies cannot. PA case-series studies in Asia have demonstrated important patterns in suicides that are helpful in informing prevention efforts such as associations between planning and gender, the role of acute stress, and the limited role of mental illness (Apter, et al., 1993; Arieli, Gilat, and Aycheh 1996; Conner, et al., 2005; Chavan, et al., 2008; Zhang, et al., 2009). The MPAC method moves beyond the traditional method by expanding inquiries into social, cultural, and economic domains while embedding the methodological strategy within the broader health and legal system. This study has several implications for prevention and intervention in both the Nepali context and low-income settings (outlined in Textbox 2) (Brent, et al., 1996; Brent and Mann 2005; World Health Organization 2010). A notable example is the rarity of decedents disclosing their thoughts of suicide to their family members. In fact, only 23% mentioned that their loved one had shared their suicide ideation. In many other low-income settings, suicide ideation disclosure is rare, often due to fear and stigma (Hagaman, et al., 2013; Jordans, et al., 2017). Determining opportunities and appropriate strategies to encourage disclosure will be important for community prevention.

Textbox 2. Study Implications and Recommendations for Suicide Detection, Prevention, and Intervention.

Surveillance: In settings with limited surveillance, Modified Psychological Autopsy for Cross-cultural Research (MPAC) demonstrates great potential to generate important information related to mortality or to complement traditional surveillance. Training police officers and/or low-level health workers to gather data and feed information into surveillance components can inform whom and what to screen for in relation to suicide risk as well as inform useful interventions. Integrating community workers into suicide mortality inquiry can also boost awareness and subsequent prevention. Finally, using MPAC may help to produce mortality numbers that are more culturally grounded and move beyond a narrow mental illness model of suicide.

Targeting interventions: Based on key risk factors among a sample of suicide deaths in Nepal, the priority populations for preventive interventions should be family members of those that have died by suicide, migrants, and survivors of domestic abuse.

Screening and suicide disclosure encouragement: Integrating screening into existing healthcare facilities, particularly government hospitals as many of the primary care physicians have been trained using WHO’s Mental Health Gap Action Programme intervention guide (mhGAP), shows great potential for effective prevention. Clinical screening should first address if a family/social history of suicide exists. Positive cases should receive suicide prevention support. Negative cases should be further assessed for recent abuse, migration, alcohol use (or excessive alcohol use of household members), feelings of shamefulness, burdensomeness and other symptoms of depression. As suicide disclosure was uncommon, encouraging disclosure with healthcare personnel or other trained gatekeepers is an important component for detection and risk assessment and, ultimately, prevention.

Adapt and implement interventions for suicide survivors: Our findings that 3 out of 5 suicide deaths had a family member that died by suicide underscores the importance of implementing programs for suicide survivors and their communities. Previous research found that a first-degree relative of someone that died by suicide is 4-6 times more likely to attempt or complete suicide [96, 98]. Further research and subsequent adaptation and development of prevention programs for families and communities of survivors (e.g. support groups, education initiatives, school-based prevention, help-lines, among many others) should be prioritized.

Additionally, other applications given our findings can be made to broader LMIC contexts including some of the following. Identification of at-risk persons: Screening patients for aforementioned warning signs such as recent geographic migration and family history may be beneficial, particular for clinicians and community members as they remain external to the family unit and may increase disclosure. Screening in primary care in LMICs has demonstrated feasibility and has the potential to reduce suicide deaths (Zalsman, et al., 2016; Mann, et al., 2005). Clinical screening, paired with community education and surveillance is currently one of the most successful prevention strategies (Cwik, et al., 2014; Jordans, et al., 2015). Implementing regular surveillance and reporting of suicidal behavior in multiple settings can help provide timely knowledge in the absence of a systematic vital registration system. Risk-reduction strategies: Prevention strategies that engage the media and community in safe reporting are crucially important, particularly because of the family and social contagion patterns that emerged in our study (Etzersdorfer and Sonneck 1998; World Health Organization 2000; Cheng, et al., 2013). Furthermore, because of the low frequency of help-seeking expressed by family member, particularly to clinical settings, community-based prevention strategies may be critically important. Such approaches have some demonstrated success elsewhere (Fleischmann, et al., 2016; Rutz, 2001; Mohanraj, et al., 2014; Calear, et al., 2016; Kohrt, et al., 2015; Vijayakumar, et al., 2013; Mann, et al., 2005). Regarding emotion regulation and enabling individuals to better negotiate relationships and conflict, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) has recently been culturally adapted for use in Nepal and has shown high feasibility and acceptability (Ramaiya, et al., 2017). However, given limited mental health resources, targeting the social situation and how illness experiences are understood by those who are suffering might be more helpful than psychotherapeutic treatment (Marrow and Luhrmann 2012). Research exploring the effectiveness of low-cost approaches for suicide prevention in LMICs should be prioritized in future suicide related explorations.

Limitations

This study gains crucial insights into suicide in Nepal, however, there are important limitations to consider. The retrospective psychological autopsy method and necessary use of a proxy informant may bias results due to memory loss and the shame and stigma around suicide deaths and other aspects discussed (domestic violence, abuse, alcohol consumption, etc). As is typical in qualitative research, our results cannot be generalized beyond our sample population. Moreover, given that, in Nepal, men serve as formal gatekeepers to the family, our sample and the perceptions of family members may be biased towards these perspectives. As the purpose of this study was to elicit recalled narratives and perceived causes of suicide, the patterns we identify above should be interpreted as such. Although these patterns may not reflect ‘factual’ representation of suicide trends, they do speak to collective beliefs of suicide etiologies and consequences, and are, therefore, important to consider in the design and deployment of suicide prevention efforts. Additionally, in Nepal, disclosing worries and problems within the dimaag (brain-mind) which is associated with cultural models of mental illness, is taboo (Kohrt and Harper 2008) and potentially limits both respondent knowledge of the deceased’s emotions and perceptions around the time of death as well as the family’s reactions and experiences following their loved one’s death. However, our approach sought to minimize this through rapport building with families, the use of local community gatekeepers, and emphasizing the project’s aim to prevent future suicide deaths. Finally, a few deaths were believed to be acts of homicide, however these families did not have the necessary agency or social position to dispute the determination of suicide. Our results should be considered and interpretation with caution given these limitations.

Conclusion

This study combined public health and ethnographic methods to improve techniques used to elicit details and context surrounding suicidal events in urban and rural Nepal. The MPAC method may be particularly useful in areas where purported suicide burdens are high, but limited surveillance, research, and prevention efforts slow appropriate response strategies. Our findings revealed several potential warning signs, including geographic migration, family history of suicide, and alcohol use, that can quickly be screened for in both clinical and community settings. Results also demonstrate that suicide prevention programming may be most effective if it targets groups strategically to account for disparate drivers based on gender, geography, and age. Stigma reduction and empowerment efforts are needed in order to improve both female and male psychosocial well-being and have the potential to serve as a tertiary prevention strategy. As suicides continue to increase around the world, research prioritizing areas where incidence is highest is urgently needed. Given that Asia holds the largest burden, disentangling the complex cultural, psychosocial, political, and economic factors is vitally important. Future research initiatives that can account for local complexities and quickly link to pragmatic suicide prevention strategies hold great promise for LMIC settings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Anestis Michael D, Bagge Courtney L, Tull Matthew T, Joiner Thomas E. Clarifying the role of emotion dysregulation in the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior in an undergraduate sample. Journal of psychiatric research. 2011;45:603–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleby Louis, Cooper Jayne, Amos Tim, Faragher Brian. Psychological autopsy study of suicides by people aged under 35. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;175:168–74. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apter Alan, Bleich Avi, King Robert A, Kron Shmuel, Fluch Avi, Kotler Moshe, Cohen Donald J. Death without warning?: a clinical postmortem study of suicide in 43 Israeli adolescent males. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:138–42. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140064007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arieli Ariel, Gilat Itzhak, Aycheh Seffefe. Suicide among Ethiopian Jews: a survey conducted by means of a psychological autopsy. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 1996;184:317–18. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199605000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett Lynn. Dangerous Wives and Sacred Sisters. Social and Symbolic Roles of High-Caste Women in Nepal 1983 [Google Scholar]

- Bernard H Russell, Wutich Amber, Ryan Gery W. Analyzing qualitative data: systematic approaches. SAGE Publications; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bhise Manik Changoji, Behere Prakash Balkrushna. Risk factors for farmers’ suicides in central rural India: Matched case–control psychological autopsy study. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2016;38:560. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.194905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billaud Julie. Suicidal Performances: Voicing Discontent in a Girls’ Dormitory in Kabul. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2012;36:264–85. doi: 10.1007/s11013-012-9262-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke Lisa. Toward understanding youth suicide in an Australian rural community. Social science and medicine. 2003;57:2355–65. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent David A, Bridge Jeff, Johnson Barbara A, Connolly John. Suicidal behavior runs in families: a controlled family study of adolescent suicide victims. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1145–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120085015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent David A, Mann J John. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics. Wiley Online Library; 2005. Family genetic studies, suicide, and suicidal behavior; pp. 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]