Abstract

Purpose

We hypothesized that whole-body metabolic tumor volume (MTVwb) could be used to supplement non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) staging due to its independent prognostic value. The goal of this study was to develop and validate a novel MTVwb risk stratification system to supplement NSCLC staging.

Methods

We performed an IRB-approved retrospective review of 935 patients with NSCLC and FDG avid tumor divided into modeling and validation cohorts based on the PET/CT scanner type used for imaging. In addition, sensitivity analysis was conducted by dividing the patient population into two randomized cohorts. Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were performed to determine the prognostic value of the MTVwb risk stratification system.

Results

The cutoff values (10.0, 53.4 and 155.0 mL) between the MTVwb quartiles of the modeling cohort were applied to both modeling and validation cohorts to determine each patient’s MTVwb risk stratum. The survival analyses showed that a lower MTVwb risk stratum was associated with better overall survival (all p<0.01), independent of the TNM stage together with other clinical prognostic factors, and the discriminatory power of the MTVwb risk stratification system, as measured by Gonen and Heller’s concordance index, was not significantly different from that of TNM stage in both cohorts. Also, the prognostic value of the MTVwb risk stratum was robust in the two randomized cohorts. The discordance rate between the MTVwb risk stratum and TNM stage or substage was 45.1% in the modeling and 50.3% in the validation cohorts.

Conclusion

This study developed and validated a novel MTVwb risk stratification system, which has prognostic value independent of the TNM stage and other clinical prognostic factors in NSCLC, suggesting it can be used for further NSCLC pretreatment assessment and for refining patient’s treatment decisions.

Introduction

Current standard-of-care treatment and prognostic assessment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) depend primarily on TNM staging[1]. The TNM staging system lacks quantitative volumetric assessment of overall tumor burden[1], and there are substantial variations in patient survival even within the same TNM stage following the standard treatment[1], suggesting that further NSCLC pre-treatment assessment to reduce heterogeneity of tumor burden within the TNM stage group may allow better treatment selection and improved clinical outcome. Whole-body metabolic tumor volume (MTVwb) measured on baseline FDG PET/CT has been shown to be of prognostic value independent of TNM stage, tumor standardized uptake value (SUV), and other clinical prognostic indicators[2–13]. However, it cannot be easily used clinically as an interval measurement. Although MTVwb has been used for risk stratification within TNM stages[3, 6, 7, 13–16], the MTVwb cutoff points in various studies were different for the same TNM stages due to heterogeneity of the tumor burden[6, 7, 16]. Based on the independent prognostic value of the MTVwb and the variation of the patient survival within the same TNM stage, we hypothesized that the MTVwb could be used clinically to supplement NSCLC staging through risk stratification, and so developed and validated a novel MTVwb risk stratification system for use in conjunction with the TNM staging system and other prognostic variables. We used total of 935 consecutive NSCLC patients with FDG avid tumor, divided into modeling and validation cohorts.

Methods

Patients

We performed an Institutional Review Board-approved retrospective review, with a waiver of informed consent of NSCLC patients who underwent baseline FDG PET/CT scans. From the database of our institutional Cancer Center Cancer Registry, we found 2,510 patients with NSCLC who were diagnosed with pathological confirmation and treated at our institution from January 2004 to December 2014. Part of this patient population was previously analyzed for different purposes and reported [2–5, 15, 16]. The patients were enrolled based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) had undergone a baseline FDG PET/CT with PET positive tumor, 2) had no evidence of brain metastasis, and 3) did not have concurrent diagnosis or a history of other primary cancer[17]. A total of 935 patients were identified and divided into modeling and validation groups based in the type of PET/CT scanner used to acquire images (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram outlining criteria used for patient inclusion and exclusion.

The study patients were followed semiannually through our Cancer Registry and through clinical services. The Cancer Registry collected data on demographics, tumor histology, treatment course, patient’s last contact date and survival status. The patient’s Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance score was determined by their treating physicians. The patients’ survival status was determined through clinical follow-up and the Social Security Death Index[18]. Overall survival (OS) was the primary endpoint of the study and was defined as the interval from the date of the baseline FDG PET/CT to the date the patient died of any cause. Patients who were last known to be alive were censored at the date of last contact. The clinical TNM stage (stage I, II, III and IV) and clinical TNM substage (IA, IB, IIA, IIB, IIIA, IIIB, IIIC, IVA and IVB) were determined based on patient’s history, FDG PET/CT and diagnostic CT findings, using the current 8th edition of the TNM staging system[1].

FDG PET/CT Data Acquisition and Analysis

FDG PET/CT techniques

In our medical center, whole-body FDG PET/CT scans were performed from the thigh to the mid-head in accordance with the National Cancer Institute guidelines [19]. For an early group of 599 patients used to model the MTVwb risk stratification system (64.1%, January 2004 to March 2012), the FDG PET/CT scans were performed with a scanner (Reveal HD, CTI, Knoxville, TN, USA) as described in a prior study[2]. In a later group of 132 (14.1%) patients, FDG PET/CT studies were acquired after March, 2012, on a Siemens mCT scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA)[20]. An additional 204 patients (21.8%) with technically adequate PET/CT scans obtained from scanners at external imaging centers were also used. The latter two groups of patients were used for the validation of the MTVwb risk stratification system. The patient population was also divided into two randomized cohorts to test the robustness of the novel MTVwb risk stratification system.

Measurements from FDG PET/CT scans

The metabolic tumor volumes (MTV, mL) of FDG-avid tumors throughout the whole body (MTVwb) and the maximum SUV of the whole-body tumor (SUVmaxwb) were measured by two radiologists using the gradient-based, PETedge tool of the MIM software (MIM Software Inc., Cleveland, Ohio, USA) as reported elsewhere[2, 21]. The tumor contours were determined using the attenuation-corrected PET images.

Statistical analyses

The differences between the two cohorts were determined with the Pearson Chi-Square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test for the interval variables.

The MTVwb risk strata and the cut-off values between them were defined based on the quartiles of the MTVwb (mL) of the modeling cohort of 599 NSCLC patients. MTVwb risk strata were then tested in both the modeling and the validation cohort with univariate and multivariate Cox regression models including clinically proven prognostic variables. The prognostic value of the MTVwb risk stratum was also tested for its robustness by randomly assigning the patients into two samples for further validation (see the supplemental material). Gonen and Heller’s concordance indices (GHCIs) were calculated for the models to evaluate the discriminatory power and prognostic accuracy of these models [22]. To compare the GHCIs of the variables in the univariate and multivariate models, a z-test was calculated based on 500 bootstrap replications[23]. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated based on MTVwb risk strata with the Log-Rank test.

The prognostic values of MTVwb tertiles, quartiles and quintiles of the modeling cohort were compared using univariate Cox regression analyses in both modeling and validation cohorts.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata Version 14.0 (StataCorp., College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of the modeling and validation cohorts

The patients’ characteristics of both the modeling and the validation cohorts are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The characteristics of patients.

| Variables | Modeling Cohort N (%) |

Validation cohort N (%) |

Cohort difference P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 599 (100) | 336(100) | |

| 8th TNM stage | 0.10 | ||

| I | 145 (24.2) | 82 (24.4) | |

| II | 92 (15.4) | 33 (9.8) | |

| III | 175 (29.2) | 115 (34.2) | |

| IV | 187 (31.2) | 106 (31.6) | |

| 8th TNM substage | 0.29 | ||

| IA | 100 (16.7) | 60 (17.9) | |

| IB | 45 (7.5) | 22 (6.6) | |

| IIA | 30 (5.0) | 14 (4.2) | |

| IIB | 61 (10.2) | 19 (5.7) | |

| IIIA | 78 (13.0) | 57 (17.0) | |

| IIIB | 65 (10.9) | 39 (11.6) | |

| IIIC | 33 (5.5) | 19 (5.7) | |

| IVA | 92 (15.4) | 45 (13.4) | |

| IVB | 95 (15.9) | 61 (18.2) | |

| MTVwb (median/IQR in mL) | 53.4/9.9–154.5 | 33.2/9.5–118.9 | 0.014 |

| MTVwb risk stratum (MTVwb range) | 0.031 | ||

| I (<10.0 mL) | 150 (25.0) | 91 (27.1) | |

| II (10.0 to 53.4 mL) | 150 (25.0) | 109 (32.4) | |

| III(53.4 to 155.0 mL) | 150 (25.0) | 71 (21.1) | |

| IV (>155.0 mL) | 149 (24.9) | 65 (19.4) | |

| SUVmaxwb (median/IQR) | 9.3/5.5–13.6 | 12.1/7.8–18.1 | <0.001 |

| Age (median/IQR, years) | 68.1/60.3–75.0 | 67.1/58.9–74.9 | 0.28 |

| Gender | 0.15 | ||

| FEMALE | 336 (56.1) | 172 (51.2) | |

| MALE | 263 (43.9) | 164 (48.8) | |

| Race* | <0.001 | ||

| White | 245 (40.9) | 213 (63.4) | |

| Black | 343 (57.3) | 101 (30.1) | |

| Other | 11 (1.8) | 22 (6.6) | |

| Smoking history | <0.001 | ||

| Never | 39 (6.5) | 46 (13.7) | |

| Current | 233 (38.9) | 90 (26.8) | |

| Prior | 327 (54.6) | 200 (59.5) | |

| Histology$ | <0.001 | ||

| Adeno | 257 (42.9) | 190 (56.6) | |

| Squamous | 165 (27.6) | 96 (28.6) | |

| Large cell | 31 (5.2) | 12 (3.6) | |

| NSCLC (NOS) | 132 (22.0) | 25 (7.4) | |

| Other | 14 (2.3) | 13 (3.9) | |

| Treatment*$ | |||

| Surg TX | 221 (36.9) | 128 (38.1) | 0.81 |

| Non-surg TX | 317 (52.9) | 178 (53.0) | |

| No TX | 61 (10.2) | 30 (8.9) | |

| ECOG PS | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 141 (23.5) | 93 (27.7) | |

| 1 | 273 (45.6) | 168 (50.0) | |

| 2 | 44 (7.4) | 40 (11.9) | |

| 3 | 25 (4.2) | 14 (4.2) | |

| 4 | 3 (0.5) | 4 (1.2) | |

| N/A | 113 (18.9) | 17 (5.1) |

Except where indicated, data are represented as N (%). Adeno = adenocarcinoma, ECOG PS =Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score, IQR= interquartile range, Large cell = large cell carcinoma, MTVwb = metabolic tumor volume of all tumors in the whole body in mL, N= number of patients unless otherwise specified, N/A = not available, NSCLC (NOS) = non-small cell lung cancer not otherwise specified, Other = other types of non-small cell lung cancer, Squamous = squamous cell carcinoma, Surg = Surgery, TX = treatment.

Note for the modeling cohort

*Other race group including 8 Asian patients, and 3 unknown race patients.

$Other histology type including 9 patients with carcinoid, 3 patients with neuroendocrine tumor, 1 patient with adenosquamous carcinoma, 1 patient with sarcomatoid carcinoma.

*$221 patients with surgery (119 patients treated with surgery alone, 51 patients treated with both surgery and chemotherapy, 13 patients treated with both surgery and radiation, and 38 patients treated with surgery, chemotherapy and radiation), 317 patients treated non-surgically (123 patients treated with chemotherapy, 59 patients treated with radiation, 135 patients treated with both chemotherapy and radiation therapy), and 61 patients had no treatment.

Note for validation cohort

*Other race group including 16 Asian patients, 3 Hawalian and Pacific Island patients and 3 unknown race patients.

$Other histology types including 10 patients with carcinoid, 2 patients with neuroendocrine tumor, 1 patient with sarcomatoid carcinoma.

*$128 patients with surgery (58 patients treated with surgery alone, 26 patients treated with both surgery and chemotherapy, 1 patients treated with both surgery and radiation, and 43 patients treated with surgery, chemotherapy and radiation), 178 patients treated non-surgically (74 patients treated with chemotherapy, 35 patients treated with radiation, and 69 patients treated with both chemotherapy and radiation therapy), 30 patients had no treatment.

For the modeling cohort containing 599 patients with a median age of 68.1 years and 56.1% women, the median overall survival was 20.5 months with 1-year, 2-year and 5-year overall survival rates of 64.8%, 46.9% and 27.8%. The median survival of TNM stages I, II, III and IV were 71.8, 44.8, 15.2, and 9.5 months, respectively. A total of 485 of the 599 patients (81.0%) died during the follow-up. Median follow-up of the 114 surviving patients was 90 months (25th percentile: 71.6 months, 75th percentile: 112.4 months).

For the validation cohort containing 336 patients with a median age of 67.1 years and 51.2% women, the median overall survival was 30.5 months with 1-year, 2-year and 5-year overall survival rates of 73.4%, 55.9% and 32.2%, respectively. The median survival in TNM stages II, III and IV were 51.2, 23.6, and 13.5 months, respectively; and that of TNM stage I was not reached. A total of 211 of the 336 patients (62.8%) died during the follow-up. Median follow-up of the 125 surviving patients was 51.3 months (25th percentile: 36.9 months, 75th percentile: 62.8 months).

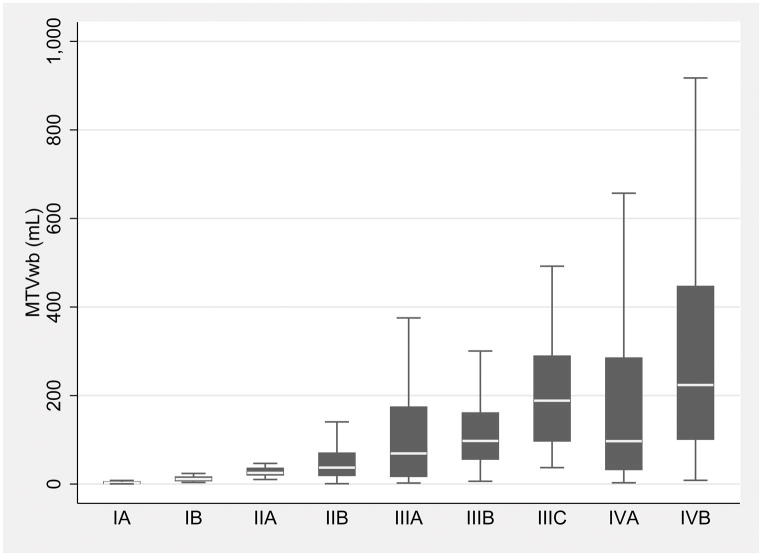

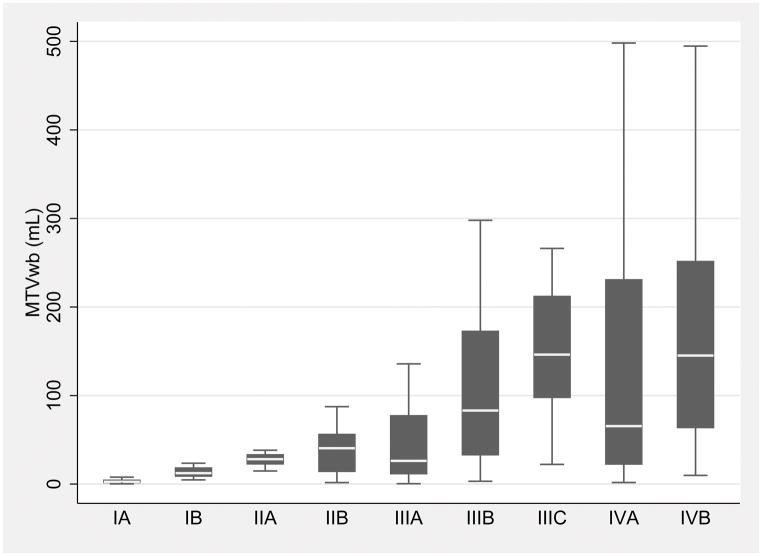

The box plots of the MTVwb in the TNM substages of both modeling and validation cohorts were depicted in Figure 2, by TNM substages (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Box plots of the whole-body metabolic tumor volume (MTVwb) in the individual TNM substages shows the MTVwb variation within individual TNM substages and overlaps among the substages in both modeling (A) and validation cohorts (B). The MTVwb median is shown by the line (short white line) that divides middle two quartiles (black box) into two parts in each TNM substage. The lower and upper whiskers represent 1st and 4th MTVwb quartiles. Note that outliers were excluded in the box plot.

MTVwb, MTVwb risk stratum, SUVmaxwb, race, smoking, tumor histology and ECOG performance score were significantly different between two cohorts (all p<0.05, respectively). TNM stage, TNM substage, age, gender and treatment were not significantly different between the two cohorts (all p>0.05, respectively)(Table 1).

All the above patient characteristics were not statistically significant different between the two randomized cohorts (all p>0.05) (Table S1 of the supplemental material).

MTVwb risk stratum definition

MTVwb risk strata (I to IV) were defined as the quartiles of the MTVwb from the modeling cohort. Three cutoff points of MTVwb at 10.0, 53.4 and 155.0 mL were derived based on the quartiles. The MTVwb values in MTVwb risk stratum I were less than 10.0 mL. The MTVwb values in MTVwb risk stratum II ranged from 10.0 to 53.4 mL. The MTVwb values in MTVwb risk stratum III ranged from 53.4 to 155.0 mL. The MTVwb values in MTVwb risk stratum IV were greater than155.0 mL.

Concordance and discordance rate between the TNM stage and MTVwb risk stratum

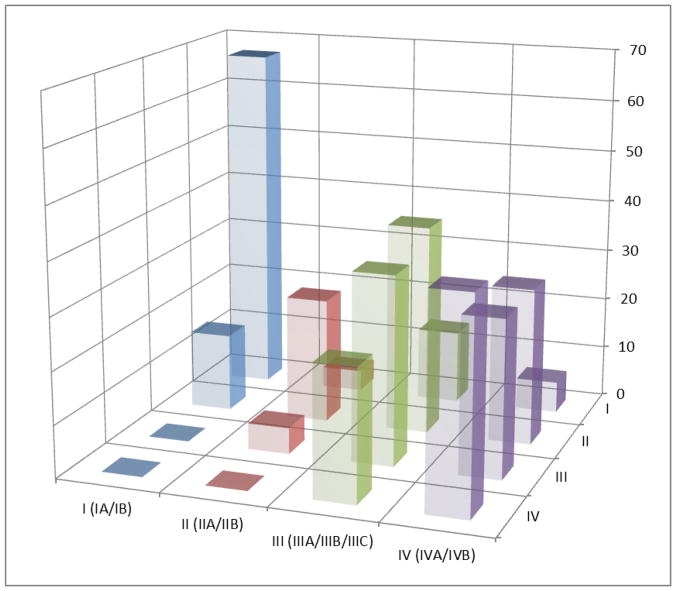

The overall discordance of the MTVwb risk strata and TNM stages in the modeling cohort was 45.1% and 50.3% in the validation cohort (Table 2). The discordance in the advanced TNM stages (III and IV) was higher than that in the early TNM stages (I and II). For example, in the modeling cohort the discordance in TNM stage I was 20 % (29/145), while that in TNM stage IV was 50.3%(94/187). Similar trends of the discordance were present in the validation cohort (18.3% in the TNM stage I and 62.3% in TNM stage IV). Furthermore, the discordance rate between the TNM stage and the MTVwb risk stratum was equal to the combined rates between the TNM substages of the respective TNM stage and the MTVwb risk stratum. Graphical demonstration of the concordance and discordance between the TNM stage and MTVwb risk stratum are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Table 2.

The concordance and discordance rates between the TNM stage and MTVwb risk stratum in both the modeling and validation cohorts.

| Modeling cohort | MTVwb risk stratum | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| TNM stage (Substages) | I | II | III | IV | Total |

| I (IA/IB) | 116 (96/20) | 29 (4/25) | 0 (0/0) | 0 (0/0) | 145 (100/45) |

| II (IIA/IIB) | 11 (0/11) | 52 (29/23) | 28 (1/27) | 0 (0/0) | 91 (30/61) |

| III (IIIA/IIIB/IIIC) | 13 (11/2/0) | 39 (25/11/3) | 68 (20/35/13) | 56 (22/17/17) | 176 (78/65/33) |

| IV (IVA/IVB) | 10 (9/1) | 30 (22/8) | 54 (24/30) | 93 (37/56) | 187 (92/95) |

|

| |||||

| Total | 150 | 150 | 150 | 149 | 599 |

|

| |||||

| Validation cohort | MTVwb risk stratum | ||||

|

| |||||

| TNM stage (Substages) | I | II | III | IV | Total |

|

| |||||

| I (IA/IB) | 67 (59/8) | 15 (1/14) | 0 (0/0) | 0 (0/0) | 82 (60/22) |

| II (IIA/IIB) | 4 (0/4) | 24 (14/10) | 5 (0/5) | 0(0/0) | 33 (14/19) |

| III (IIIA/IIIB/IIIC) | 14 (11/3/0) | 40 (28/10/2) | 36 (12/15/9) | 25 (6/11/8) | 115 (57/39/19) |

| IV (IVA/IVB) | 6 (4/2) | 30 (18/12) | 30 (10/20) | 40 (13/27) | 106 (45/61) |

|

| |||||

| Total | 91 | 109 | 71 | 65 | 336 |

Note: The data is expressed as the number of patients in both of the TNM stage (rows) and MTVwb risk (columns) stratum, and in the parentheses are the number of patients in the TNM substage. Concordance between the TNM stage and the MTVwb risk stratum means the TNM stage and the MTVwb risk stratum are the same in the patients. For example, in TNM stage I of the modeling cohort, 116 patients (96 patients with stage IA and 20 patients with stage IB) had MTVwb risk stratum I, and 29 patients (4 patients with stage IA and 25 patients with stage IB) had MTVwb risk stratum II. Therefore in the TNM stage I, the TNM stage and MTVwb risk stratum were concordant in 116/145 patients (80.0%) and discordant in 29/145 patients (20%), which are equal to the concordance and discordance rates between the TNM substage and the MTVwb risk stratum as the TNM substages are included in their respective TNM stage. Of the 599 patients of modeling cohort, 270 patients (45.1 %) were discordant between TNM stage and MTVwb risk stratum, with a majority of these being within +/− one MTVwb risk stratum (36.2%). The discordance rate for deviations greater than +/− one MTVwb risk stratum in the modeling cohort was 8.8%. Of the 336 patients in the validation cohort, 167 patients (50.3%) were discordant with a majority of these being +/− one MTVwb risk stratum (35.4%). In the validation cohort, the discordance rate for deviations greater than +/− one MTVwb risk stratum was 14.9%.

Fig. 3.

Three-dimensional graphical representation of the concordance and discordance between the TNM stage and MTVwb risk stratum in both modeling (A) and validation Cohorts (B), using the data in Table 2. The horizontal-axis is the MTVwb risk stratum (I, II, III and IV), the depth-axis is the TNM stage [I (IA/IB), II (IIA/IIB), III (IIIA/IIIB/IIIC) and IV (IVA/IVB)], and the vertical-axis is number of patients. The bars along the diagonal, where TNM stage and MTVwb risk stratum are equal, show concordance. The remaining non-zero bars indicate the number of patients with discordant TNM stage and MTVwb risk stratum.

Prognostic value of the MTVwb risk stratification system

Univariate Cox regression analyses

In the modeling cohort, univariate Cox regression analyses (Table 3) demonstrated statistically significant associations of OS with MTVwb risk strata (p<0.0001) with HRs of 1.80, 2.80 and 5.49 for MTVwb risk stratum II, III, and IV relative to the MTVwb risk stratum I, respectively. Other variables that were significantly associated with OS included TNM stage, TNM substage, SUVmaxwb, gender, race, tumor histology type, treatment type and ECOG performance score. The GHCI of the MTVwb risk stratum (0.656) was not statistically significantly different from that of TNM stage (0.654, p=0.82) or TNM substage (0.673, p=0.09) or treatment type (0.644, p=0.28). The GHCI of the MTVwb risk stratum was significantly greater than that of other variables including SUVmaxwb, age, gender, race, smoking, tumor histology and ECOG performance score (all p<0.001).

Table 3.

Univariate Cox Regression Analyses

| Variables | Modeling Cohort | Validation Cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| 8th TNM stage | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| I | reference | reference | ||

| II | 1.40 (1.01–1.93) | 0.043 | 1.84 (1.04–3.26) | 0.037 |

| III | 3.01 (2.31–3.92) | <0.001 | 2.74 (1.80–4.17) | <0.001 |

| IV | 4.74 (3.64–6.17) | <0.001 | 4.56 (3.01–6.91) | <0.001 |

| 8th TNM substage | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| IA | reference | reference | ||

| IB | 1.36 (0.88–2.12) | 0.17 | 1.35 (0.62–2.93) | 0.45 |

| IIA | 1.68 (1.03–2.74) | 0.039 | 1.75 (0.78–3.64) | 0.18 |

| IIB | 1.48 (0.99–2.21) | 0.056 | 2.20 (1.06–4.55) | 0.033 |

| IIIA | 2.84 (2.00–4.03) | <0.001 | 2.42 (1.42–4.15) | 0.001 |

| IIIB | 4.01 (2.78–5.79) | <0.001 | 3.02 (1.69–5.41) | <0.001 |

| IIIC | 3.86 (2.46–6.05) | <0.001 | 5.45 (2.85–10.42) | <0.001 |

| IVA | 3.83 (2.72–5.39) | <0.001 | 3.73 (2.15–6.46) | <0.001 |

| IVB | 8.22 (5.83–11.58) | <0.001 | 6.05 (3.67–9.96) | <0.001 |

| MTVwb risk stratum | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| I | reference | reference | ||

| II | 1.80(1.37–2.37) | <0.001 | 2.40 (1.58–3.64) | <0.001 |

| III | 2.80 (2.14–3.67) | <0.001 | 3.98 (2.57–6.16) | <0.001 |

| IV | 5.49 (4.18–7.19) | <0.001 | 5.74 (3.71–8.89) | <0.001 |

| SUVmaxwb# | 1.65(1.46–1.87) | <0.0001 | 1.91 (1.55–2.36) | <0.0001 |

| Age (years) | 1.01 (1.0–1.02) | 0.0647 | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 0.0003 |

| Gender | 0.0019 | 0.88 | ||

| FEMALE | reference | reference | 0.88 | |

| MALE | 1.33 (1.11–1.59) | 0.002 | 1.02 (0.78–1.34) | |

| Race | 0.0006 | 0.36 | ||

| White | reference | reference | ||

| Black | 1.42 (1.18–172) | <0.001 | 1.23 (0.92–1.66) | 0.16 |

| Other | 1.68 (0.89–3.18) | 0.11 | 1.00 (0.59–1.71) | 0.10 |

| Smoking history | 0.0778 | 0.43 | ||

| Never | reference | reference | ||

| Current | 1.58 (1.59–2.34) | 0.025 | 1.32 (0.83–2.09) | 0.25 |

| Prior | 1.52 (1.03–2.25) | 0.034 | 1.31 (0.86–2.00) | 0.21 |

| Histology | <0.0001 | 0.0373 | ||

| Adeno | reference | reference | ||

| Squamous | 1.21 (0.97–1.50) | 0.086 | 1.12 (0.83–1.53) | 0.45 |

| Large cell | 0.81 (0.52–1.27) | 0.36 | 1.66 (0.81–3.41) | 0.17 |

| NSCLC | ||||

| (NOS) | 1.94 (1.54–2.43) | <0.001 | 1.52 (0.94–2.48) | 0.089 |

| other | 0.39 (0.17–0.88) | 0.025 | 0.27 (0.09–0.86) | 0.026 |

| Treatment | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Surg TX | reference | reference | ||

| Non-surg TX | 3.55 (2.87–4.39) | <0.001 | 3.66 (2.63–5.09) | <0.001 |

| No TX | 5.04 (3.69–6.88) | <0.001 | 6.31 (3.81–10.46) | <0.001 |

| ECOG PS* | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||

| 0 | reference | reference | ||

| 1 | 1.33 (1.04–1.69) | 0.021 | 1.66 (1.17–2.35) | 0.004 |

| 2 | 2.96 (2.04–4.29) | <0.001 | 2.01 (1.26–3.22) | 0.003 |

| 3 | 2.82 (1.80–4.42) | <0.001 | 3.88 (1.99–7.57) | <0.001 |

| 4 | 5.91 (1.85–18.87) | 0.003 | 4.94 (1.76–13.81) | 0.002 |

Notes: 95% CI=95% confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio. Other abbreviations are same as in Table 1. Natural log transformed # SUVmaxwb was used in the analysis.

only patients with known ECOG PS were included in the analysis (486 of 599 patients in the modeling cohort and 319 of 336 patients in validation cohort).

In the modeling cohort, Gonen and Heller’s concordance indices (GHCI) of the models (in the parenthesis) and their significance tests:

TNM stage (0.654) vs.TNM substage (0.673, p=0.003).

MTVwb risk stratum (0.656) vs.TNM stage (0.654, p=0.82).

MTVwb risk stratum vs.TNM substage (0.673, p=0.09).

MTVwb risk stratum vs. treatment (0.644, p=0.28).

MTVwb risk stratum vs. other variables including SUVmaxwb (0.596), age (0.526), gender (0.535), race (0.544), smoking(0.517), tumor histology (0.577) and ECOG performance score (0.577) (all p<0.001).

In the validation cohort, GHCI of the models in the parenthesis and their significance tests:

TNM stage (0.643) vs.TNM substage (0.658, p=0.058).

MTVwb risk stratum (0.658) vs.TNM substage (p=0.99).

MTVwb risk stratum vs.TNM stage (0.643, p=0.31).

MTVwb risk stratum vs. treatment (0.653, p=0.78).

MTVwb risk stratum vs. SUVmaxwb (0.618, p=0.021), age (0.571, p=0.002) and ECOG performance score (0.582, p=0.002) as well as other clinical variables including gender (0.503), race (0.522), smoking history (0.516), tumor histology (0.551) (all p<0.001).

In the validation cohort, univariate Cox regression analyses (Table 3) demonstrated statistically significant associations of OS and MTVwb risk strata (p<0.0001) with HRs of 2.40, 3.98 and 5.75 for MTVwb risk strata II, III, and IV relative to the MTVwb risk stratum I, respectively. Other variables that were significantly associated with OS included TNM stage, TNM substage, SUVmaxwb, age, tumor histology type, treatment type and ECOG performance score (all p<0.05). The GHCI of the MTVwb risk stratum (0.658) was not significantly different from that of TNM substage (0.658, p=0.99) or TNM stage (0.643, p=0.31) or treatment type (0.653, p=0.78). The MTVwb risk stratum had a significantly greater GHCI than SUVmaxwb (p=0.021), age (p=0.002) or ECOG performance score (p=0.02) as well as other variables including gender, race, smoking history, tumor histology (all p<0.001).

Multivariate Cox regression analyses

The following 5 multivariate models were used to compare the independent prognostic values of MTVwb risk stratum, TNM stage and TNM substages.

In the modeling cohort, TNM stage, TNM substage, and MTVwb risk stratum, SUVmaxwb, age, gender, race, smoking history, treatment type, and tumor histology were included in 3 multivariate models to evaluate their joint effect and the adjusted effect of TNM stage, TNM substage and MTVwb risk stratum on OS in models 1–3 (Table 4). In models 4 and 5, the effect of MTVwb risk stratum on OS was further evaluated with additional adjustment by TNM stage or TNM substage.

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox Regression Analyses

| Modeling cohort (n=599) | Validation cohort (n=319) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Models | Multivariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|

| ||||

| HR | p-value | HR | p-value | |

| Model 1 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||

| 8th TNM stage | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||

| I | reference | reference | ||

| II | 1.19 (0.84–1.67) | 0.32 | 1.50 (0.82–2.77) | 0.19 |

| III | 1.95 (1.41–2.69) | <0.001 | 1.97 (1.23–3.17) | 0.005 |

| IV | 3.25 (2.36–4.48) | <0.001 | 3.08 (1.86–5.08) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| 8th TNM substage | <0.0001 | 0.0008 | ||

| IA | reference | reference | ||

| IB | 1.14 (0.72–1.82) | 0.57 | 1.15 (0.52–2.57) | 0.73 |

| IIA | 1.32 (0.78–2.22) | 0.30 | 1.47 (0.64–3.41) | 0.36 |

| IIB | 1.29 (0.84–1.98) | 0.25 | 1.68 (0.76–3.69) | 0.20 |

| IIIA | 1.94 (1.28–2.94) | 0.002 | 2.20 (1.23–3.94) | 0.008 |

| IIIB | 2.86 (1.84–4.45) | <0.001 | 1.58 (0.81–3.10) | 0.18 |

| IIIC | 2.07 (1.20–3.56) | 0.009 | 2.86 (1.36–6.01) | 0.006 |

| IVA | 2.82 (1.89–4.21) | <0.001 | 2.61 (1.39–4.90) | 0.003 |

| IVB | 5.44 (3.50–8.45) | <0.001 | 3.93 (2.13–7.28) | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| MTVwb risk stratum | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| I | 1 | reference | ||

| II | 1.62 (1.18–2.22) | 0.003 | 1.89 (1.15–3.08) | 0.011 |

| III | 2.43 (1.71–3.46) | <0.001 | 3.23 (1.84–5.68) | <0.001 |

| IV | 4.21 (2.91–6.09) | <0.001 | 4.43 (2.46–7.98) | <0.001 |

| Model 4 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| MTVwb risk stratum | <0.0001 | 0.002 | ||

| I | reference | reference | ||

| II | 1.54 (1.06–2.24) | 0.023 | 1.61 (0.90–2.87) | 0.11 |

| III | 2.09 (1.36–3.20) | 0.001 | 2.40 (1.23–4.69) | 0.011 |

| IV | 3.17 (2.04–4.93) | <0.001 | 3.33 (1.67–6.62) | 0.001 |

| 8th TNM stage | <0.0001 | 0.087 | ||

| I | ||||

| II | 0.91 (0.60–1.36) | 0.64 | 1.14 (0.57–2.28) | 0.72 |

| III | 1.31 (0.89–1.92) | 0.16 | 1.31 (0.74–2.34) | 0.35 |

| IV | 2.11 (1.44–3.11) | <0.001 | 1.92 (1.04–3.55) | 0.037 |

| Model 5 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| MTVwb risk stratum | <0.0001 | 0.0044 | ||

| I | reference | reference | ||

| II | 1.49 (1.00–2.22) | 0.05 | 1.70 (0.84–3.42) | 0.14 |

| III | 1.88 (1.20–2.93) | 0.006 | 2.53 (1.19–5.37) | 0.015 |

| IV | 3.03 (1.91–4.81) | <0.001 | 3.47 (1.59–7.58) | 0.002 |

| 8th TNM substage | <0.0001 | 0.24 | ||

| IA | reference | reference | ||

| IB | 1.08 (0.66–1.77) | 0.76 | 0.83 (0.32–2.16) | 0.71 |

| IIA | 1.09 (0.59–2.02) | 0.80 | 0.99 (0.34–2.84) | 0.98 |

| IIB | 0.96 (0.57–1.60) | 0.86 | 1.08 (0.42–2.80) | 0.87 |

| IIIA | 1.27 (0.77–2.08) | 0.35 | 1.40 (0.63–3.09) | 0.41 |

| IIIB | 2.09 (1.23–3.52) | 0.006 | 0.87 (0.37–2.06) | 0.75 |

| IIIC | 1.30 (0.70–2.40) | 0.41 | 1.44 (0.56–3.74) | 0.45 |

| IVA | 1.94 (1.19–3.14) | 0.008 | 1.52 (0.65–3.55) | 0.34 |

| IVB | 3.16 (1.85–5.39) | <0.001 | 1.94 (0.83–4.54) | 0.13 |

Note: Both the modeling and the validation models controlled for age, gender, race, smoking history, treatment and tumor histology and SUVmaxwb. In the validation models, the ECOG performance score was also controlled for in 319 patients. The abbreviations are same in Tables 1 and 3.

In the modeling cohort, Gonen and Heller’s concordance indices (GHCI) of the models in the parenthesis and their significance tests:

Model 1 (0.707) vs. model 2 (0.715, p=0.042).

Model 1 vs. model 3 (0.708, p=0.89).

Model 2 vs. model 3 (p=0.39).

Model 4 (0.722) vs. model 5 (0.728, p=0.068).

In the validation cohort, GHCI of the models in the parenthesis and their significant tests:

Model 1 (0.733) vs. model 2 (0.735, p=0.58).

Model 1 vs. model 3 (0.742, p=0.22).

Model 2 vs. model 3 (p=0.44).

Model 4 (0.744) vs. model 5 (0.746, p=0.55).

In Models 1–3, TNM stage, TNM substage, and MTVwb risk stratum (considered separately) remained as statistically significant prognostic markers for survival (all p < 0.0001), after adjusting for SUVmaxwb, age, gender, race, smoking history, treatment type and tumor histology. The GHCIs for the models including the TNM stage, TNM substage, and MTVwb risk stratum were 0.707, 0.715, and 0.708, respectively. The GHCI of the model including TNM stage or TNM substage was not significantly different from that of MTVwb risk stratum (both p>0.05).

In Model 4 including TNM stage and MTVwb risk stratum, both of them remained as statistically significant prognostic markers for survival (both p<0.0001) after adjusting for the same variables in models 1–3. In Model 5 including TNM substage and MTVwb risk stratum, both of them remained as statistically significant prognostic markers for survival (both p<0.0001) after adjusting for the same variables in models 1–3. There was no statistically significant difference of the GHCIs for models 4 (0.722) and 5 (0.728) (p=0.068).

In the validation cohort, TNM stage, TNM substage, and MTVwb risk stratum, SUVmaxwb, age, gender, race, smoking history, treatment type, tumor histology and ECOG performance score were included in the multivariate models to evaluate their joint effect on OS (Table 4). In Models 1–3, TNM stage, TNM substage, and MTVwb risk stratum remained as statistically significant prognostic markers for survival (all p < 0.0001), after adjusting for SUVmaxwb, age, gender, race, smoking history, treatment type, tumor histology and ECOG performance score. The GHCIs for the models including the TNM stage, TNM substage, and MTVwb risk stratum were 0.733, 0.735, and 0.742, respectively and there were no statistically significant difference between them (all p>0.05).

In Model 4 including TNM stage and MTVwb risk stratum, MTVwb risk stratum remained as a statistically significant prognostic marker for survival after adjusting for the same variables used in the models 1–3 and TNM stage (p=0.0022). But the TNM stage was not statistically significantly associated with OS (p=0.087), after adjusting for the MTVwb risk stratum and other variables. In Model 5 including MTVwb risk stratum and TNM substage, MTVwb risk stratum remained as a statistically significant prognostic marker for survival (p=0.004) after adjusting for the same variables used in models 1–3 and TNM substage, but the TNM substage was not statistically significantly associated with OS (p=0.24) after adjusting for the same variables used in models 1–3 and MTVwb risk stratum. There was no statistically significant difference between the GHCIs of models 4 (0.744) and 5 (0.746) (p=0.55).

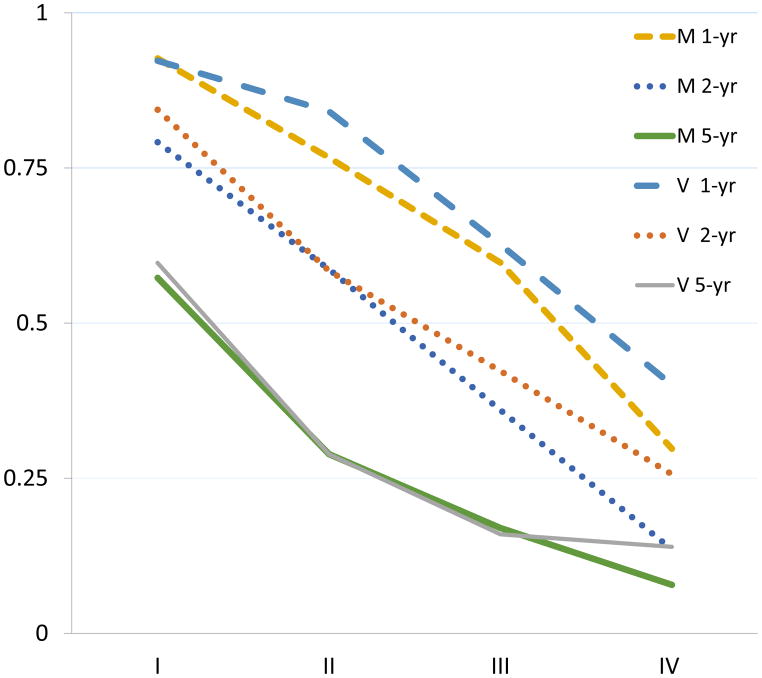

The Kaplan-Meier curves of OS of the MTVwb risk strata showed (Fig. 4A and Fig. 4B) higher MTVwb risk stratum was associated with worse overall survival in both modeling and validation cohorts (both p<0.0001). The 1-year, 2-year and 5-year survival rates of both modeling and validation cohorts were similar as demonstrated in Fig. 4C.

Fig 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival after baseline PET/CT grouped by MTVwb risk stratum (A) in the 599 NSCLC patients used for modeling, and the 336 patients for validation (B); showing that lower MTVwb risk stratum in both cohorts are associated with better overall survival; X 2(3)=189.4 (p<0.0001) and X 2(3)= 79.5 (p<0.0001) respectively. The comparison of 1-year, 2-year and 5-year survival rates of both modeling and validation cohorts (C) demonstrates a good agreement of the survival rates between the cohorts. M 1-yr, M 2-yr and M 5-yr are the overall survival rates of the modeling cohort at 1-year, 2-year and 5-years, respectively. V 1-yr, V 2-yr and V 5-yr are the overall survival rates of the validation cohort at 1-year, 2-year and 5-years, respectively. I, II, III and IV on the horizontal-axis represent MTVwb risk strata.

The univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses and Kaplan-Meier survival analyses showed that the MTVwb risk stratum had prognostic value independent of the TNM stage and other clinical prognostic factors in NSCLC in both randomized cohorts (Table S2 and S3 and Fig. S1 of the supplemental material).

The comparison of the prognostic values of MTVwb tertiles, quartiles (MTVwb risk stratum), and MTVwb quintiles demonstrated that those MTVwb classifications were individually significantly associated with OS (all p<0.0001) in both the modeling and validation cohorts. There is no statistically significant difference of prognostic power between the MTVwb quartiles and MTVwb quintiles (p=0.13 and p=0.43, respectively in modeling and validation cohorts). However, MTVwb tertiles had lower prognostic power than either MTVwb quartiles (p=0.007 in both cohorts) or MTVwb quintiles(p<0.001and p=0.009 respectively in modeling and validation cohorts) as measured by Cstatistics (Table S4 of the supplemental material).

Discussion

The current study used MTVwb quartiles of the modeling patient cohort to define the three cut-off values (10.0, 53.4 and 155 ml) of the MTVwb risk strata. Based on previous research that the logarithm of MTVwb is prognostic of OS in a linear fashion [2, 4, 5, 15], we hypothesized that the spread of MTVwb is a crucial measure of prognostic power and defined MTVwb risk strata (I to IV) as the quartiles of the MTVwb of modeling cohort, instead of direct use of the natural logarithmic transformed MTVwb to further remove the effect of outliers. Using MTVwb quartiles to define MTVwb risk strata allowed us to obtain an MTVwb risk stratum system comparable to the TNM staging system and to avoid small sample sizes in the two systems. Furthermore, our analyses showed that MTVwb risk stratum has similar prognostic value to the MTVwb quintiles and better prognostic value than the MTVwb tertiles of the modeling cohort, as measured by Cstatistics in both modeling and validation cohorts (Table S4 of Supplemental material). The MTVwb risk strata were then tested in both modeling and validation cohorts divided based on the PET/CT scanner types with Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier survival analyses which showed a statistically significant association of MTVwb risk stratum with OS, independent of the TNM stage and other clinical prognostic factors. The discriminatory power of MTVwb risk stratum as measured by GHCI was not significantly different from that of TNM stage or TNM substage in univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses. The above results were robust in the two, randomly divided patient cohorts, suggesting the approach may be generalizable to the general population. Our results also showed that the MTVwb risk stratum and TNM stage are metrics that describe different aspects of underlying tumor activity, as there were large variation of MTVwb within individual TNM substages (Fig. 2), and 45.1% discordance in the modeling cohort and a 50.3% discordance in the validation cohort between MTVwb risk stratum and TNM stage (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

A patient with a higher MTVwb risk stratum than the current TNM stage suggests that his/her prognosis is worse than that of a patient with concordant TNM stage and MTVwb risk stratum, and vice versa as demonstrated in this study (Fig. 4 and Tables 3 and 4). Hence, it seems that the treatment type chosen should be adjusted for this prognostic factor. Therefore our MTVwb risk stratification system provides an additional factor to consider when choosing treatment type.

There are several important clinical implications of the MTVwb risk stratification system in NSCLC patients. First, because treatment decision making is affected by the patient’s prognosis and MTVwb risk strata have been demonstrated to be discordant with TNM stages in more than 45% patients and to have prognostic value independent of TNM stage and other clinical prognostic variables, the inclusion of MTVwb risk strata should allow better treatment decision making in such patients. This is consistent with current oncological practice guideline that the choices of treatment modalities should incorporate the consideration of the visually estimated mediastinal tumor burden in patients with TNM stage III NSCLC [24]. If a patient has TNM stage IV and MTVwb stratum II, clinicians may surgically remove primary lung cancer and solitary metastasis. This is consistent with a systematic review of 49 retrospective studies of 2176 patients with stage IV NSCLC with oligo-metastatic state[25]. That study noted that surgical metastasectomy in such patients with limited tumor burden achieved highly variable but improved survival outcomes, with 5-year OS rates of 10–80%.

Second, the improved estimate of survival provided by using MTVwb risk stratum along with established prognostic variables may help patients in their future planning by weighing the cost and benefit of individualized treatment, and hence increase the treatments’ patient centeredness and satisfaction. Finally, the MTVwb risk stratum could be used in clinical trials to better define experimental and control patient populations by addressing the potential heterogeneity among patients. Refining the estimate of OS by using MTVwb risk stratum, after estimating OS using the clinically established variables including TNM stage, may lead to more effective and more efficient trials.

The FDG PET/CT scans of the modeling cohort and validation cohort were performed with different scanners from the same institution or different institutions in the current study as described in the methods section and the study cohorts for modeling and validation had significantly different MTVwb values, MTVwb risk strata, SUVmaxwb, race, smoking history, tumor histology type and ECOG performance score. Therefore, the FDG PET/CT scanners used in the study and clinical variables in the modeling and validation cohorts mimic real world situations, suggesting that the MTVwb risk stratification system developed and validated in this study may be generalizable to other centers. There are other reasons to expect that the MTVwb risk stratification system can be used in other centers and be practical in clinical use including: 1) measurement of MTVwb is practical with commercially available software, and semi-automatic tumor segmentation is as accurate as manual segmentation for primary NSCLC tumors [25]; 2) MTVwb estimates are relatively insensitive to different FDG PET/CT scanners and image-reconstruction algorithms [26]; 3) a number of studies have demonstrated consistently significant correlation between survival and MTVwb in NSCLC, in different parts of the world, and with different FDG PET/CT scanners[2–11, 13, 14, 27–31], 4) the variability of metabolic tumor volume in NSCLC primary tumors is less than that of SUV for NSCLC primary tumor in PET scans of 1-hour vs. 2-hour FDG uptake time [32]; and 5) MTVwb measurements are relatively immune to inter-observer variability[2, 5].

This study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective study and therefore the treatment of the patients was determined by the prevailing clinical protocols at the time of patient’s management. Second, the performance score was only included in the analyses of the validation cohort in the multivariate Cox models because in 18.9% (113/599) of patients the performance score was not available in the modeling cohort. Third, the cut-off values for the MTVwb risk strata are based on the sample from a single site. Although the distribution of the TNM stages in this sample appears similar to that of a national sample[33, 34], multi-center studies are needed to further validate the cut-off values for the MTVwb risk strata for the typical NSCLC patient population.

Conclusions

This study developed and validated a novel MTVwb risk stratification system, which has a prognostic value independent of the TNM stage and other clinical prognostic factors in NSCLC, suggesting it can be used for further NSCLC pretreatment assessment and for refining patient’s treatment decisions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding source: This work was supported in part by a grant (R21 CA181885) from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

Kristen Wroblewski, MS; Department of Public Health Sciences, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA for her statistical guidance.

Mark K. Ferguson, MD; Thoracic Surgery Service, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, for his constructive comments.

This work was supported in part by a grant (R21 CA181885) from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

Special thanks to our chest oncological team at the University of Chicago for taking care of our study patients.

The authors have not used writing assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure:

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions:

Guarantors of integrity of entire study: Yonglin Pu and James X. Zhang and Bill C. Penney.

Study concepts/study design or data acquisition or data analysis/interpretation: all authors.

Manuscript drafting or manuscript revision for important intellectual content: all authors.

Approval of final version of submitted manuscript: all authors.

Agrees to ensure any questions related to the work are appropriately resolved by all authors.

Literature research: Yonglin Pu and James X. Zhang.

Clinical studies: Daniel Appelbaum, Haiyan Liu and Yonglin Pu.

Statistical analysis: Yonglin Pu, Jianfeng Meng, and James X. Zhang.

Manuscript editing: all authors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board of the University of Chicago, which waived the requirement for informed consent and all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed Consent: The requirement for informed consent was waived.

Availability of data and materials: The data supporting the findings can be found in the corresponding author’s institution.

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Eberhardt WE, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liao S, Penney BC, Wroblewski K, Zhang H, Simon CA, Kampalath R, et al. Prognostic value of metabolic tumor burden on 18F-FDG PET in nonsurgical patients with non-small cell lung cancer. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2012;39:27–38. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1934-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao S, Penney BC, Zhang H, Suzuki K, Pu Y. Prognostic Value of the Quantitative Metabolic Volumetric Measurement on 18F-FDG PET/CT in Stage IV Nonsurgical Small-cell Lung Cancer. Academic Radiology. 2012;19:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang H, Wroblewski K, Appelbaum D, Pu Y. Independent prognostic value of whole-body metabolic tumor burden from FDG-PET in non-small cell lung cancer. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery. 2013;8:181–91. doi: 10.1007/s11548-012-0749-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang H, Wroblewski K, Liao S, Kampalath R, Penney BC, Zhang Y, et al. Prognostic value of metabolic tumor burden from (18)F-FDG PET in surgical patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Acad Radiol. 2013;20:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyun SH, Ahn HK, Ahn MJ, Ahn YC, Kim J, Shim YM, et al. Volume-based assessment with 18F-FDG PET/CT improves outcome prediction for patients with stage iiia-n2 non-small cell lung cancer. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2015;205:623–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Im HJ, Pak K, Cheon GJ, Kang KW, Kim SJ, Kim IJ, et al. Prognostic value of volumetric parameters of 18F-FDG PET in non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2014;42:241–51. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2903-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winther-Larsen A, Fledelius J, Sorensen BS, Meldgaard P. Metabolic tumor burden as marker of outcome in advanced EGFR wild-type NSCLC patients treated with erlotinib. Lung Cancer. 2016;94:81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung HW, Lee KY, Kim HJ, Kim WS, So Y. FDG PET/CT metabolic tumor volume and total lesion glycolysis predict prognosis in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2014;140:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1545-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohri N, Duan F, MacHtay M, Gorelick JJ, Snyder BS, Alavi A, et al. Pretreatment FDG-PET metrics in stage III non-small cell lung cancer: ACRIN 6668/RTOG 0235. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2015:107. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satoh Y, Onishi H, Nambu A, Araki T. Volume-based parameters measured by using FDG PET/CT in patients with stage i NSCLC treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy: Prognostic value. Radiology. 2014;270:275–81. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoo J, Choi JY, Lee KT, Heo JS, Park SB, Moon SH, et al. Prognostic Significance of Volume-based Metabolic Parameters by 18F-FDG PET/CT in Gallbladder Carcinoma. Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2012;46:201–6. doi: 10.1007/s13139-012-0147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abelson JA, Murphy JD, Trakul N, Bazan JG, Maxim PG, Graves EE, et al. Metabolic imaging metrics correlate with survival in early stage lung cancer treated with stereotactic ablative radiotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2012;78:219–24. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoo SW, Kim J, Chong A, Kwon SY, Min JJ, Song HC, et al. Metabolic tumor volume measured by F-18 FDG PET/CT can further stratify the prognosis of patients with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2012;46:286–93. doi: 10.1007/s13139-012-0165-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, Wroblewski K, Jiang Y, Penney BC, Appelbaum D, Simon CA, et al. A new PET/CT volumetric prognostic index for non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2015;89:43–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finkle JH, Jo SY, Ferguson MK, Liu HY, Zhang C, Zhu X, et al. Risk-stratifying capacity of PET/CT metabolic tumor volume in stage IIIA non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3659-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu X, Liao C, Penney BC, Li F, Ferguson MK, Simon CA, et al. Prognostic value of quantitative PET/CT in patients with a nonsmall cell lung cancer and another primary cancer. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 2017;38:185–92. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935–2014. 2017. Ancestry. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shankar LK, Hoffman JM, Bacharach S, Graham MM, Karp J, Lammertsma AA, et al. Consensus recommendations for the use of 18F-FDG PET as an indicator of therapeutic response in patients in National Cancer Institute Trials. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2006;47:1059–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C, Liao C, Penney BC, Appelbaum DE, Simon CA, Pu Y. Relationship between overall survival of patients with non-small cell lung cancer and whole-body metabolic tumor burden seen on postsurgical fluorodeoxyglucose PET images. Radiology. 2015;275:862–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14141398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner-Wasik M, Nelson AD, Choi W, Arai Y, Faulhaber PF, Kang P, et al. What is the best way to contour lung tumors on PET scans? Multiobserver validation of a gradient-based method using a NSCLC digital PET phantom. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:1164–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gönen M, Heller G. Concordance probability and discriminatory power in proportional hazards regression. Biometrika. 2005;92:965–70. doi: 10.1093/biomet/92.4.965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mooney CZ. Bootstrap statistical inference: Examples and evaluations for political science. American Journal of Political Science. 1996;40:570–602. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramnath N, Dilling TJ, Harris LJ, Kim AW, Michaud GC, Balekian AA, et al. Treatment of Stage III Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: Diagnosis and Management of Lung Cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e314S–e40S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obara PLH, Wroblewski K, Zhang CP, Hou P, Jiang Y, Chen P, Pu Y. Quantification of metabolic tumor activity and burden in patients with NSCLC: Is manual adjustment of semi-automatic gradient based measurements necessary? Nucl Med Commun. 2015;36:782–9. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werner-Wasik M, Nelson AD, Choi W, Arai Y, Faulhaber PF, Kang P, et al. What is the best way to contour lung tumors on PET scans? Multiobserver validation of a gradient-based method using a NSCLC digital PET phantom. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2012;82:1164–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee P, Weerasuriya DK, Lavori PW, Quon A, Hara W, Maxim PG, et al. {A figure is presented}Metabolic Tumor Burden Predicts for Disease Progression and Death in Lung Cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2007;69:328–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee P, Bazan JG, Lavori PW, Weerasuriya DK, Quon A, Le QT, et al. Metabolic tumor volume is an independent prognostic factor in patients treated definitively for nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Clinical Lung Cancer. 2012;13:52–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim K, Kim SJ, Kim IJ, Kim YS, Pak K, Kim H. Prognostic value of volumetric parameters measured by F-18 FDG PET/CT in surgically resected non-small-cell lung cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2012;33:613–20. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328351d4f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyun SH, Choi JY, Kim K, Kim J, Shim YM, Um SW, et al. Volume-based parameters of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography improve outcome prediction in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer after surgical resection. Annals of Surgery. 2013;257:364–70. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318262a6ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carvalho S, Leijenaar RTH, Velazquez ER, Oberije C, Parmar C, Van Elmpt W, et al. Prognostic value of metabolic metrics extracted from baseline positron emission tomography images in non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Oncologica. 2013;52:1398–404. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.812795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu H, Chen P, Wroblewski K, Hou P, Zhang C, Jiang Y, et al. Consistency of metabolic tumor volume of non-small-cell lung cancer primary tumor measured using 18F-FDG PET/CT at two different tracer uptake times. Nucl Med Commun. 2016;37:50–6. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Cancer Institute U. Distribution of lung cancer diagnoses by stage at diagnosis, 2004–2013. 2017. Last Updated January 2017 ed. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgensztern D, Ng SH, Gao F, Govindan R. Trends in Stage Distribution for Patients with Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: A National Cancer Database Survey. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2010;5:29–33. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c5920c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.