Abstract

Background

Prior studies of patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) have suggested racial/ethnic variation in end-of-life decision making. We sought to evaluate whether race/ethnicity modifies the implementation of comfort measures only status (CMOs) in patients with spontaneous, non-traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH).

Methods

We analyzed data from the Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study, a prospective cohort study specifically designed to enroll equal numbers of white, black and Hispanic subjects. ICH patients aged ≥18 years were enrolled in ERICH at 42 hospitals in the USA from 2010 to 2015. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were implemented to evaluate the association between race/ethnicity and CMOs after adjustment for potential confounders.

Results

2705 ICH cases (912 black, 893 Hispanic, 900 white) were included in this study (mean age 62 (SD 14), female sex 1119 [41%]). CMOs patients comprised 276 (10%) of the entire cohort; of these, 64 (7%) were black, 79 (9%) Hispanic and 133 (15%) white (univariate p<0.001). In multivariate analysis, compared to whites, blacks were half as likely to be made CMOs (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.75; p=0.001) and no statistically significant difference was observed for Hispanics. All three racial/ethnic groups had similar mortality rates at discharge (whites 12%, blacks 9% and Hispanics 10%; p=0.108). Other factors independently associated with CMOs included age (p<0.001), premorbid modified Rankin Scale (p<0.001), dementia (p=0.008), admission Glasgow Coma Scale (p=0.009), hematoma volume (p<0.001), intraventricular hematoma volume (p<0.001), lobar (p=0.032) and brainstem (p<0.001) location and endotracheal intubation (p<0.001).

Conclusions

In ICH, black patients are less likely than white patients to have CMOs. However, in-hospital mortality is similar across all racial/ethnic groups. Further investigation is warranted to better understand the causes and implications of racial disparities in CMO decisions.

Keywords: End-of-life care, Race and ethnicity, Intracerebral hemorrhage

INTRODUCTION

Surrogate decision-making is common in spontaneous, non-traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), a devastating stroke subtype with extremely elevated morbidity and mortality. Families and physicians may discuss transitioning care to comfort measures only status (CMOs) after ICH when the apparent prognosis is not consistent with the quality of life perceived to be acceptable to the patient. An important challenge when engaging in these discussions is to provide an accurate assessment of the likely prognosis of the specific patient. However, prognostic models for ICH are biased by withdrawal of care that leads to self-fulfilling prophecies.1 Clinical judgment of physicians and nurses, while subjective, more closely correlates with outcome than prognostic scales.2

In the context of uncertain neurological prognoses, families and physicians engage in shared decision-making to pursue treatment options that most closely align with the patient’s values and wishes.3 Factors that influence these decisions include pattern and severity of outcome, probability of outcomes, burden of treatment and other factors such as age, cultural and spiritual beliefs, preexisting comorbidity, caregiver burden and financial consequences.4 Erroneous prognostic estimates, method of communicating evidence, misunderstanding of patient values and expectations and undervaluing future patient health states further bias decisions towards overuse or underuse of aggressive treatment.

Unwarranted variation in goals of care decisions have life or death consequences. Overuse of aggressive treatment may cause patients to be kept alive in a state they would consider worse than death; underuse may lead to unwanted death when a meaningful outcome was possible. Here, we investigate in ICH the reported trend towards pursuing aggressive treatment at the end of life by non-whites in general ICU settings.5–11 We seek to clarify the association between race/ethnicity and CMOs in a large ICH cohort specifically designed to attain equal power across three different racial/ethnic groups. We hypothesize that CMOs is observed less frequently in blacks and Hispanics compared to whites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The ERICH study is a prospective, multi-center, observational study of spontaneous, non-traumatic ICH with an emphasis on recruitment of minority populations in the United States. The study is designed for equal power between racial/ethnic categories and seeks to examine epidemiological and genetic risk factors for ICH as well as functional outcomes in this condition. Institutional Review Board approval was required for each study site, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects or their legally authorized representatives.

Case ascertainment

The ERICH protocol has been previously reported.12 Briefly, one thousand non-Hispanic black, 1000 non-Hispanic white, and 1000 Hispanic patients with spontaneous ICH were enrolled at 42 sites across the United States from January 2010 through October 2015. All cases met the eligibility criteria of age ≥18 years and presence of ICH, defined as a spontaneous, non-traumatic abrupt onset of severe headache, altered level of consciousness or focal neurological deficit associated with a focal collection of blood within the brain parenchyma seen on neuroimaging (either CT or MRI). Hot-pursuit recruitment, used for ICH case identification for acute clinical trials, was implemented to reduce survival bias. Admission logs, emergency room logs, and neurology, neurosurgery, and neurointensive care unit logs were actively screened to recruit patients within 48 hours of admission.13 Study personnel received in-person and on-site training on effective ways to approach patients and families to facilitate inclusion of more severe cases.14

Outcome ascertainment

The primary outcome of this study was CMOs, defined as a formal withdrawal of aggressive treatment with CMO or hospice orders documented in the medical record.

Neuroimaging

A blinded, central neuroimaging core confirmed the diagnosis of ICH, determined hematoma location (deep, lobar, cerebellar and brainstem), and measured hematoma volume and intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) volume from serial CT and MRI scans. Measurements from the initial CT scans were used for this analysis. Hematoma and IVH volumes were measured by planimetric analysis using Alice software (Parexel Corporation, Waltham, MA).

Variable definition

Information on covariates were abstracted from medical records using standardized clinical research forms. Collected variables included age, sex, race, medical insurance coverage, highest level of education completed, premorbid Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score, history of hypertension and dementia, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score on admission, intubation at any time during hospitalization, orders for DNR, do-not-intubate (DNI) or CMO at any time during hospitalization, vital status at discharge, cause of death, and mRS at 30 days post-stroke or final discharge. DNR and DNI orders required documentation in the medical record to withhold resuscitative measures in the event of cardiopulmonary arrest or intubation, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as counts (percentages [%]) for discrete variables and median (interquartile range [IQR]) or mean (standard deviation [SD]) for continuous variables as appropriate. Univariate analysis of differences between racial/ethnic groups was performed using chi-square, t or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate.

Logistic regression analysis

Multivariate logistic regression models were built to determine the association between race/ethnicity and CMOs after adjusting for potential confounders. Covariates were selected a priori based on known predictors of ICH outcome as determined by the ICH score15 to predict 30-day mortality and FUNC score16 to predict functional independence, and included age, premorbid mRS, dementia, admission GCS, hematoma and IVH volume, ICH location, and intubation in addition to the demographic factors education and insurance status. We used the variance inflation factor, the factor by which variance is inflated by the existence of correlation among covariates, to evaluate for collinearity across variables included in our models. A variance inflation factor >10 is usually considered significant.

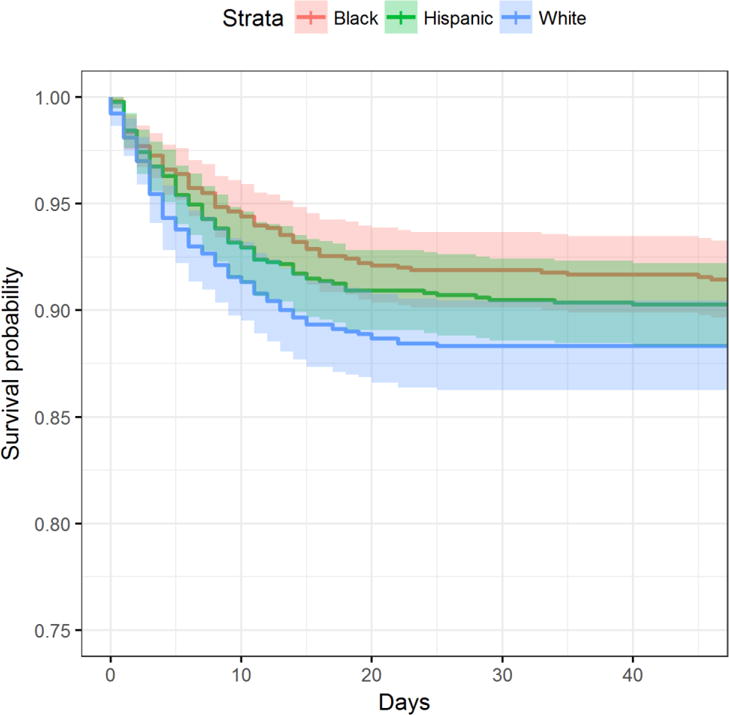

Survival curves

We used Kaplan-Meier survival curves, together with the log-rank test, to visually describe the unadjusted distribution of inpatient mortality across different racial/ethnic groups.

Missing data

To account for missing data, we performed random imputation with 20 imputed datasets. The imputation model included all the variables used in the final multivariate analysis.

A two-tailed test of significance was set at p<0.05 for all statistical analyses. Analyses were performed with SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

RESULTS

Of the 3000 cases in the cohort, 39 cases were excluded because CMOs was unknown. An additional 127 cases were excluded because of missing ICH scores, and 129 were excluded for missing data on past medical history, premorbid mRS, education or insurance status. We analyzed 2705 ICH cases with complete data, distributed equally across blacks (n=912), Hispanics (n=893), and whites (n=900). In the complete study population, 848 (31%) were lobar hemorrhages whereas 1857 (69%) were non-lobar hemorrhages. Hypertension, the most important risk factor for ICH, was present in 2287 (85%) of the overall study sample.

Patient population

Abundant heterogeneity was observed among black, Hispanic, and white patients in demographic and clinical variables (Table 1). Whites were older [mean 68 (SD 13)] than blacks [58 (12)] and Hispanics [59 (14)] (p<0.001). Baseline disability as measured by mRS score >1 was more common in whites (23%) than blacks (14%) and Hispanics (15%) (p<0.001). Lobar location was more common in whites (43%) than blacks (24%) and Hispanics (27%) (p<0.001). Hematoma volume was higher in whites [23 (27)] than blacks [17 (22)] and Hispanics [21 (25)] (p<0.001). Distribution of ICH scores did not vary by race/ethnicity (p=0.172), though mean ICH score was lower for blacks [1.2 (1.1)] than Hispanics [1.3 (1.2)] and whites [1.3 (1.2)] (p=0.031).

Table 1.

Population characteristics by race/ethnicity

| Covariate | Total (n=2705) | Black (n=912) | Hispanic (n=893) | White (n=900) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and Past Medical History | |||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 62 (14) | 58 (12) | 59 (14) | 68 (13) | <0.001 |

| Female, N (%) | 1119 (41) | 394 (43) | 336 (38) | 389 (43) | 0.021 |

| Education, N (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Less than high school | 721 (27) | 202 (22) | 425 (48) | 94 (10) | |

| High school or technical school | 883 (33) | 338 (37) | 269 (30) | 276 (31) | |

| Beyond high school | 1101 (41) | 372 (41) | 199 (22) | 530 (59) | |

| Covered by medical insurance, N (%) | 1997 (74) | 628 (69) | 563 (63) | 806 (90) | <0.001 |

| Premorbid mRS > 1, N (%) | 474 (18) | 131 (14) | 136 (15) | 207 (23) | <0.001 |

| Dementia, N (%) | 175 (7) | 47 (5) | 40 (5) | 88 (10) | <0.001 |

| History of hypertension, N (%) | 2287 (85) | 839 (92) | 733 (82) | 715 (79) | <0.001 |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||

| Admission GCS, mean (SD) | 13 (4) | 12 (4) | 13 (4) | 13 (3) | 0.001 |

| Location of bleed, N (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Deep | 1501 (56) | 569 (62) | 520 (58) | 412 (46) | |

| Lobar | 848 (31) | 218 (24) | 243 (27) | 387 (43) | |

| Brainstem | 146 (5) | 59 (7) | 51 (6) | 36 (4) | |

| Cerebellum | 210 (8) | 66 (7) | 79 (9) | 65 (7) | |

| Intubation, N (%) | 963 (36) | 350 (38) | 333 (37) | 280 (31) | 0.002 |

| ICH Score, mean (SD) | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.3 (1.2) | 0.031 |

| Radiological Characteristics | |||||

| Hematoma volume, mean (SD), mL | 20 (25) | 17 (22) | 21 (25) | 23 (27) | <0.001 |

| IVH volume, mean (SD), mL | 6 (16) | 7 (15) | 6 (15) | 6 (17) | 0.610 |

CMOs and race/ethnicity

We found significant differences in CMOs among analyzed race/ethnicity (Table 2). CMOs was conferred upon 276 patients (10%); of these 133 (15%) were white, 64 (7%) were black and 79 (9%) were Hispanic (p<0.001). In multivariate analysis, blacks were half as likely as whites to have CMOs (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.75; p=0.001) (Table 3). Hispanic patients showed a trend towards less CMOs, though this association did not hold in multivariate analysis (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.06; p=0.093). In addition to black race, independent predictors of CMOs included age (p<0.001), premorbid mRS (p<0.001), dementia (p=0.008), GCS on admission (p=0.009), hematoma volume (p<0.001), IVH volume (p<0.001), lobar (p=0.032) and brainstem (p<0.001) location, and intubation (p<0.001). Time from admission to CMOs was twice as long for black compared to white patients, an association that held after multivariate analysis (p=0.017).

Table 2.

Intensity of treatment and outcome by race/ethnicity

| Total (n=2705) | Black (n=912) | Hispanic (n=893) | White (n=900) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orders for limited care, N (%) | |||||

| DNR | 383 (14) | 91 (10) | 112 (13) | 180 (20) | <0.001 |

| DNI | 217 (8) | 47 (5) | 50 (6) | 120 (13) | <0.001 |

| CMO | 276 (10) | 64 (7) | 79 (9) | 133 (15) | <0.001 |

| Admission to CMOs, mean (SD), days | 7 (10) | 10 (12) | 9 (11) | 5 (7) | 0.001 |

| Timing of CMOs, N (%) | 0.002 | ||||

| Within 2 days of admission | 96 (35) | 17 (27) | 17 (22) | 62 (47) | |

| 3-7 days after admission | 80 (29) | 18 (29) | 26 (34) | 36 (27) | |

| Over 7 days from admission | 96 (35) | 28 (44) | 34 (44) | 34 (26) | |

| Mechanism of inpatient death, N (%) | 0.006 | ||||

| Brain death | 57 (21) | 19 (25) | 23 (26) | 15 (15) | |

| Withdrawal of care | 156 (58) | 37 (48) | 46 (51) | 73 (71) | |

| Cardiac arrest | 22 (8) | 8 (10) | 12 (13) | 2 (2) | |

| Other | 35 (13) | 13 (17) | 9 (10) | 13 (13) | |

| Length of stay, mean (SD), days | 13 (16) | 15 (18) | 14 (16) | 10 (12) | <0.001 |

| Inpatient mortality, N (%) | 277 (10) | 80 (9) | 91 (10) | 106 (12) | 0.108 |

| Discharge mRS, median (IQR) | 4 (3-4) | 4 (2-4) | 4 (2-4) | 4 (3-4) | 0.698 |

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for CMOs

| Covariate | Univariate analysis for CMOs | Multivariate analysis for CMOs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||

| Black | 0.44 (0.32-0.60) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.34-0.75) | 0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.56 (0.42-0.75) | <0.001 | 0.72 (0.49-1.06) | 0.093 |

| Age | 1.06 (1.05-1.07) | <0.001 | 1.06 (1.05-1.08) | <0.001 |

| Education level | 1.00 (0.86-1.17) | 0.986 | 1.04 (0.85-1.27) | 0.701 |

| Insured | 2.64 (1.83-3.80) | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.49-1.23) | 0.280 |

| Premorbid mRS | 1.56 (1.42-1.71) | <0.001 | 1.38 (1.22-1.57) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 4.49 (3.17-6.38) | <0.001 | 1.93 (1.19-3.13) | 0.008 |

| Admission GCS | 0.83 (0.80-0.85) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.91-0.99) | 0.009 |

| Hematoma Volume | 1.03 (1.02-1.03) | <0.001 | 1.02 (1.01-1.02) | <0.001 |

| IVH Volume | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | <0.001 | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | <0.001 |

| Location of bleed | ||||

| Deep | Reference | Reference | ||

| Lobar | 1.60 (1.22-2.11) | 0.001 | 0.65 (0.44-0.96) | 0.032 |

| Brainstem | 2.90 (1.86-4.51) | <0.001 | 5.15 (2.97-8.91) | <0.001 |

| Intubation | 6.64 (4.99-8.83) | <0.001 | 5.00 (3.39-7.36) | <0.001 |

Mortality

Despite the differences in CMOs across racial/ethnic groups mentioned above, survival distributions were not significantly different at hospital discharge (p=0.097) (Figure 1). Overall, 277 patients (10%) died by discharge; of these, 106 (12%) were white, 80 (9%) were black and 91 (10%) were Hispanic (p=0.108). Withdrawal of support after CMO orders was the mechanism of 156 (58%) inpatient deaths. As expected, white patients were significantly more likely than black and Hispanic patients to die by this mechanism. Overall hospital length of stay was shorter for whites [10 days (12)] than blacks [15 (18)] and Hispanics [14 (16)] (p<0.001).

Figure 1. Survival to discharge by race/ethnicity.

Despite different rates of implementation of CMOs, survival distributions at discharge did not differ by race/ethnicity (p=0.097).

DISCUSSION

In this study, CMOs was implemented less often in minority patients with ICH. Overall, 10% of patients were made CMO, distributed unequally between black (7%), Hispanic (9%), and white (15%) patients. Mortality at discharge did not differ by race/ethnicity, but among the 277 patients who died in this cohort, non-white patients were less likely to have CMOs. For Hispanics, lower rates of CMOs were largely explained by age, premorbid condition and clinical severity, but these covariates did not explain the association for blacks.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies that found limitations of care after ICH are implemented differently by race/ethnicity.17,18 Furthermore, our findings are in line with an analysis of Medicare decedents that found blacks and Hispanics incur significantly higher expenditures than whites at the end of life despite receiving fewer medical services and treatment-related spending overall.19 Our study adds to the body of literature by examining use of CMOs across equally represented black, white and Hispanic patients while adjusting for potential confounders. While we were unable to collect data to explain the marked difference in use of CMOs between white and black patients, several explanations have been suggested. Lower rates of palliative care use in black communities has been attributed to a loss of credibility in the healthcare system;20 spiritual and religious beliefs;21,22 and access, education and communication surrounding end-of-life care.23–25

Understanding the racial variation we report here has important implications for compassionate end-of-life care. Cultural competence training in medical education may improve the lower levels of satisfaction with physician communication and hospital support associated with end-of-life care reported by families of black decedents.26 Outreach programs to minority communities can help dispel misconceptions about palliative care and reduce decisional conflict for patient surrogates.27

This study has three main strengths. The first is the design for equal statistical power between black, Hispanic and white race/ethnicity. The second is the recruitment of a large number of patients from 42 sites across the United States. The third is the uniform diagnosis of ICH and the availability of variables including components of the ICH score and FUNC score to control for clinical severity and comorbid conditions that impact CMO decisions.28–30 Furthermore, demographic information including education level and insurance status were available to evaluate other influences on CMO decisions.

Some limitations to the study must also be acknowledged. Although survival bias was reduced using a hot-pursuit method, enrolled cases were more likely than non-enrolled cases to survive to discharge. This explains our low inpatient mortality rate of 10% compared to the 26% rate published from a national dataset.31 However, discharge to hospice did not differ between patients enrolled and not enrolled in ERICH. We addressed missing data in this cohort with random imputation and found similar conclusions for complete case and imputation analyses. Finally, our study did not collect variables to explain our findings, including advance directives, religiosity, goals of care discussions, and provider and hospital characteristics.

Our study demonstrates racial variability in goals of care decisions. Future studies should seek to understand the causes of this variation and ascertain if this bias leads to overuse or underuse of aggressive treatment.

SUMMARY.

We examined associations with the use of CMOs in a large, multicenter, multi-ethnic prospective study that used hot-pursuit methodology to reduce survival bias. Blacks and Hispanics were less likely than whites to have CMOs after ICH. For Hispanic patients, this association was largely explained by age, premorbid condition and severity assessed by components of the ICH and FUNC scores. After adjusting for these covariates, black patients were still half as likely as white patients to have CMOs. Further study is warranted to investigate reasons underlying this variation and implications in outcome.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS: U-01-NS069763). This report does not represent the official view of NINDS, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), or any part of the US Federal Government. No official support or endorsement of this article by NINDS or NIH is intended or should be inferred.

Dr. Falcone is supported by a Yale Pepper Scholar Award (P30AG021342) and the Neurocritical Care Society Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Conception and design of the study: CHO, GJF, DMM, KNS, DW. Acquisition and analysis of data: CHO, GJF, DMM, ACL, LCM, KNS, DW, CDL. Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures: CHO, GJF, SDJ, DMM, DYH, KNS, MLJ, FDT, KJB, DLT, DW.

Disclosures: The other authors have no disclosures.

Competing Interests: All authors report no competing interests relevant to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Becker KJ, Baxter AB, Cohen WA, et al. Withdrawal of support in intracerebral hemorrhage may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Neurology. 2001;56:766–72. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.6.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hwang DY, Dell CA, Sparks MJ, et al. Clinician judgment vs formal scales for predicting intracerebral hemorrhage outcomes. Neurology. 2016;86:126–33. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai X, Robinson J, Muehlschlegel S, et al. Patient Preferences and Surrogate Decision Making in Neuroscience Intensive Care Units. Neurocritical Care. 2015;23:131–41. doi: 10.1007/s12028-015-0149-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holloway RG, Benesch CG, Burgin WS, Zentner JB. Prognosis and decision making in severe stroke. JAMA. 2005;294:725–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper Z, Rivara FP, Wang J, MacKenzie EJ, Jurkovich GJ. Racial disparities in intensity of care at the end-of-life: are trauma patients the same as the rest? Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2012;23:857–74. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shepardson LB, Gordon HS, Ibrahim SA, Harper DL, Rosenthal GE. Racial variation in the use of do-not-resuscitate orders. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14:15–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bardach N, Zhao S, Pantilat S, Johnston SC. Adjustment for do-not-resuscitate orders reverses the apparent in-hospital mortality advantage for minorities. The American Journal of Medicine. 2005;118:400–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qureshi AI, Adil MM, Suri MF. Rate of use and determinants of withdrawal of care among patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage in the United States. World Neurosurgery. 2014;82:e579–84. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diringer MN, Edwards DF, Aiyagari V, Hollingsworth H. Factors associated with withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in a neurology/neurosurgery intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine. 2001;29:1792–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200109000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin MA, Dhar R, Diringer MN. Racial differences in withdrawal of mechanical ventilation do not alter mortality in neurologically injured patients. Journal of Critical Care. 2014;29:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi HA, Fernandez A, Jeon SB, et al. Ethnic disparities in end-of-life care after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocritical Care. 2015;22:423–8. doi: 10.1007/s12028-014-0073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woo D, Rosand J, Kidwell C, et al. The Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study protocol. Stroke. 2013;44:e120–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheth KN, Martini SR, Moomaw CJ, et al. Prophylactic Antiepileptic Drug Use and Outcome in the Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage Study. Stroke. 2015;46:3532–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siddiqui FM, Langefeld CD, Moomaw CJ, et al. Use of Statins and Outcomes in Intracerebral Hemorrhage Patients. Stroke. 2017;48:2098–104. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemphill JC, 3rd, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32:891–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rost NS, Smith EE, Chang Y, et al. Prediction of functional outcome in patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage: the FUNC score. Stroke. 2008;39:2304–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.512202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zurasky JA, Aiyagari V, Zazulia AR, Shackelford A, Diringer MN. Early mortality following spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2005;64:725–7. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152045.56837.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zahuranec DB, Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, et al. Ethnic differences in do-not-resuscitate orders after intracerebral hemorrhage. Critical Care Medicine. 2009;37:2807–11. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a56755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanchate A, Kronman AC, Young-Xu Y, Ash AS, Emanuel E. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life costs: why do minorities cost more than whites? Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169:493–501. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crawley L, Payne R, Bolden J, Payne T, Washington P, Williams S. Palliative and end-of-life care in the African American community. JAMA. 2000;284:2518–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhodes RL, Elwood B, Lee SC, Tiro JA, Halm EA, Skinner CS. The Desires of Their Hearts: The Multidisciplinary Perspectives of African Americans on End-of-Life Care in the African American Community. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2017;34:510–7. doi: 10.1177/1049909116631776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky JA. What explains racial differences in the use of advance directives and attitudes toward hospice care? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:1953–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01919.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhodes RL, Batchelor K, Lee SC, Halm EA. Barriers to end-of-life care for African Americans from the providers’ perspective: opportunity for intervention development. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2015;32:137–43. doi: 10.1177/1049909113507127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yancu CN, Farmer DF, Leahman D. Barriers to hospice use and palliative care services use by African American adults. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2010;27:248–53. doi: 10.1177/1049909109349942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noh H, Schroepfer TA. Terminally ill African American elders’ access to and use of hospice care. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2015;32:286–97. doi: 10.1177/1049909113518092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V. End-of-life care in black and white: race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:1145–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith-Howell ER, Hickman SE, Meghani SH, Perkins SM, Rawl SM. End-of-Life Decision Making and Communication of Bereaved Family Members of African Americans with Serious Illness. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2016;19:174–82. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faigle R, Marsh EB, Llinas RH, Urrutia VC, Gottesman RF. Race-Specific Predictors of Mortality in Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Differential Impacts of Intraventricular Hemorrhage and Age Among Blacks and Whites. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2016;5 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flaherty ML, Woo D, Haverbusch M, et al. Racial variations in location and risk of intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2005;36:934–7. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000160756.72109.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cruz-Flores S, Rabinstein A, Biller J, et al. Racial-ethnic disparities in stroke care: the American experience: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:2091–116. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182213e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.James ML, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Olson DM, et al. Insurance status and outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage: findings from Get With The Guidelines-stroke. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases: the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2014;23:283–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]