Abstract

There are varieties of surgical approaches reported for equine splenectomy and all of them were dealing with the most reachable situation of splenic hilus and easy handling of the spleen. The aim of this work was to establish the normal ultrasound parameters of spleen in donkeys (normal echogenicity, hilus situation, topographic location and correlation with neighboring organs) as a guide to select the best approach for total splenectomy in donkeys. Splenic ultrasound was carried out on six normal donkeys before experimental total splenectomy in the standing position. The splenic topographic location was recorded among 4 rows including 30 squares. These animals were divided into two groups according to the surgical approach of total splenectomy. Total splenectomy after left 16th and 17th ribs partial resection in standing position was carried out in group1 and group 2, respectively. Ultrasonographically, the spleen had homogenously echogenic pattern and appeared hyperechoic to the liver. Only one third of the spleen was located in front of the 16th rib where the hilus and splenic blood vessels were nearly under the 16th rib. The splenic artery and splenic vein were ultrasonographically visualized between the left 16th and 17th ribs 10–15 cm from dorsal midline. This area was the site of the important ligation during total splenectomy. In conclusion, ultrasonography guidance for total splenectomy in donkeys assisted the surgical findings and proved that technique following partial resection of the 17th rib at the standing position is the most convenient surgical approach for total splenectomy in donkeys.

Keywords: Intercostal spaces, Rib, Spleen, Splenomegaly, Ultrasound

1. Introduction

Donkeys (Equus asinus) have been reared as companions to humans for thousands of years and sequentially used worldwide as heavy working animals [1]. Over 38% of the global equine population (114 million) is donkeys and more than 97% are found in developing countries. In spite of their significant influence to the countrywide economy, the attention given to study the diseases of working donkeys is negligible [2].

The spleen is one of the hematopoietic and lymphoid organs. It is responsible for storing and eliminating erythrocytes from the blood, antigen surveillance of the blood and antibody creation. According to the authors’ knowledge, there is no available literature about the ultrasound scanning of the normal spleen in donkeys. Researches in horses recorded splenic lesions using ultrasonography either per rectum or through the left abdominal wall [3]. Ultrasonography can be useful in investigating splenic masses and splenic rapture [4]. The spleen is one of the more easily imaged organs in the horse and the splenic parenchyma is the most echogenic tissue in the abdomen [4], [5].

In equine practice, it is interesting that most of the authors have carried out splenectomy operation for splenomegaly or hypersplenism caused by the parasite Babesia equi [6], [7], [8], [9]. Other indications include neoplasia as lymphosarcoma, melanoma and hemangiosarcoma beside trauma, rupture and infarction [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16].

Reported surgical approaches of splenectomy included a left paralumbar fossa incision caudal to the 18th rib [9]; an incision between the last 2 ribs [17]; resection of the 16th rib [18], [19]; resection of the 17th rib [6], [8], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21] or resection of the 18th rib [19]. The challenges facing researchers to select the most suitable splenectomy technique are opening at the reachable site of the splenic hilus to easily ligate the main blood vessels in addition to other risk factors like opening of the diaphragm, narrow or far surgical field and easy handling of voluminous spleen without injuries.

The aim of this work was to establish the normal ultrasound parameters of the spleen in donkeys (normal echogenicity, hilus situation, topographic intra-abdominal location and correlation with neighboring organs) as a guide to select the best surgical approach of total splenectomy in standing donkeys.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals

Six healthy adult donkeys of both sexes aged from 2 to10 years were subjected to total splenectomy in standing position. The study was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), Cairo University (CU-II-F-87-18). The animals were equally divided into two main groups. Animals were injected with Diminazine aceturate (Berenil® Vet 7% RTU, MSD Animal Health, Egypt) at the dose rate of 3.5 mg/kg body weight by deep intramuscular route at multiple sites as a prophylaxis against babesiosis 2 weeks preoperative [22].

In group-1 (N = 3), total splenectomy after partial resection of the 16th rib in standing position was performed.

In group-2 (N = 3), total splenectomy after partial resection of the 17th rib in standing position was performed.

2.2. Ultrasound examination

All donkeys were subjected to ultrasound examination just before total splenectomy. The scanned area was identified with the following anatomical marks; flank region caudally, costal arch dorsally and up to 9th rib cranially. The area was divided into 4 rows and each row was 7 cm length which corresponded to the transducer length. These 4 rows were divided into 30 squares (intercostal spaces marked each of them).

The ultrasound examination of the spleen and splenic blood vessels was performed using a B-mode scan with a 3.5 MHz linear probe in longitudinal position. The ultrasound scanner was equipped with an auto-adaptive linear transducer (EXAGO, Echo Control Medical, France).

2.3. Preparation of animals for operation

All animals were fasted for 12 h before operation.

The left side of the thoracic wall was clipped and shaved from the 15th–18th rib, then washed with water and soap, greased with alcohol and finally touched with Povidone iodine. An intravenous catheter in the left jugular vein was adopted.

2.4. Anesthesia

Animals were sedated using Xylazine HCl (1.1 mg/kg b.wt, i.v.) then the site of operation was infiltrated in a linear manner at the intended line of incision using Xylocaine HCl [23], [24].

2.5. Surgical technique

Total splenectomy was performed according to Auer and Stick [25]. A skin incision was made at the intended site of incision [G-1 at the 16th rib and G-2 at the 17th rib] starting 10–15 cm from the dorsal midline. The subcutis and muscles were also incised. The periosteum was then incised and reflected using a periosteal elevator to free the rib from underlying tissues.

The rib was then cut using embryotomy saw, and reflected distally and fixed with the thoracic wall using towel clips. The abdominal cavity was then opened, the diaphragm was sutured to abdominal wall in continues manner to close chest cavity and the tail of spleen was exteriorized.

The renosplenic and phrenicosplenic ligaments were severed with scissors. Care was taken to avoid injury of the splenic vessels located between them. The left gastric epiploic and short gastric vessels were double ligated and the splenic vessels were also double ligated (Fig. 1). After ligating the vessels, a cut was made between the ligatures then the spleen was removed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Splenectomy in a donkey. (a) Left gastric epiploic, short gastric vessels (yellow arrow) and splenic blood vessels were double ligated. (b) One ligature (black arrow) was laid close to the stomach and the other was close to the spleen. (c) A cut was made between the ligatures. (d) The excised spleen. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Reposition of the severed rib to its normal site and then suture of abdominal muscles by continues fashion was done. Subcutaneous tissue and skin were closed routinely.

2.6. Post-operative management

Postoperatively, the animals were given a massive antibiotic course of Cefotaxime sodium (25 mg/Kg b.wt, i.v.) 3 times daily for 7 days and Metronidazole (15 mg/kg b.wt, orally) 3 times daily for 7 days and Phenylbutazone (1.1 mg/kg b.wt, i.v.) for 3 days. Generally, anti-tetanic serum was administered at a dose of 1500 IU for each donkey. The ordinary oral feeding was stopped for 3 days and replaced by the water of boiled barely and intravenous fluid therapy (6 L every 12 hs) composed of 2 L of Dextrose 5% and 4 L of Ringer’s solution. Daily dressing of the skin wound with Povidone iodine solution was also done. The skin sutures were removed at 7 days post operative.

3. Results

During splenic ultrasonography, the spleen was homogenously echogenic and appeared hyperechoic to the left kidney. Only one third of the spleen was located in front of left 16th rib where the hilus and splenic blood vessels were nearly under the left rib 16th. The splenic artery after originating from celiac artery and splenic vein before emptying into the portal vein were ultrasonographically visualized between the left 16th and 17th ribs 10–15 cm from the dorsal midline (square no. 8). This area was the site of the most important ligation during total splenectomy.

The splenic vein was visible in nearly all donkeys near the gastrosplenic space. The left kidney was visible deep to the spleen in the left paralumbar fossa and caudal intercostal spaces (15th–17th). The stomach was located dorsal to the spleen and ventral to the lung in the left 10th–15th intercostal spaces.

According to the ultrasound examination, the scanned area was divided into 4 rows and each row measured 7 cm in length. The first row started with the cranial pole of the left kidney at the left flank region and continued cranially with the splenic base which started from left18th rib and extended to 14th rib.

The second row contained a part of the left kidney. The splenic body began from 18th rib and extended to 13th rib. Splenic vessels demonstrated at the square 8 (Fig. 2) which located in the intercostal space between left 16th and 17th ribs.

Fig. 2.

(a) Topographical anatomy of the spleen in a donkey. (b) Ultrasongraphic findings of spleen in the scanned area.

In the third row, the flank region contained intestine. The spleen extended from 18th rib till 10th rib. The fourth row contained the apex of the spleen which located at the level of lower abdomen between left 16th and 15th ribs and extended to 10th rib.

By ultrasound examination, the diaphragm was detected under the intercostal muscles and above the spleen in all squares except squares numbers (1,6,12,13,21,22,23 and 24, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6).

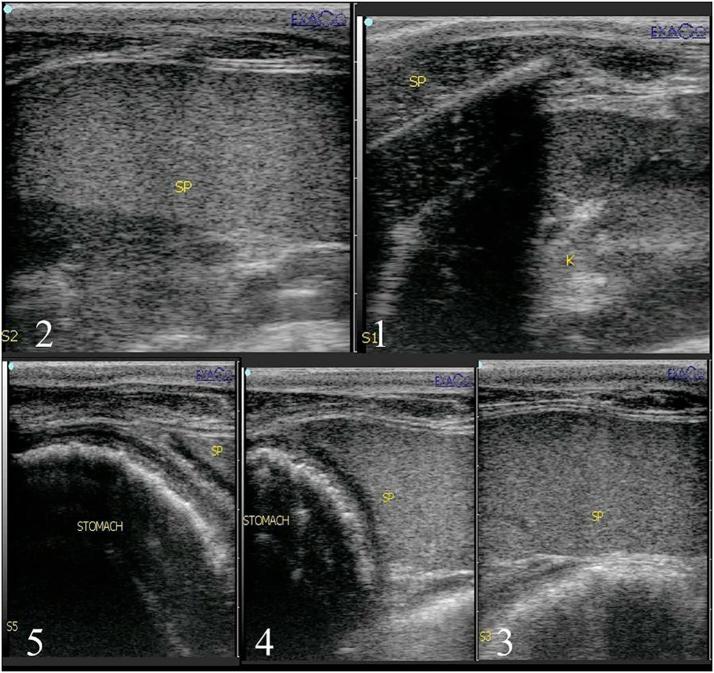

Fig. 3.

Ultrasonography at upper part of the left flank region showing left kidney and small part of spleen base (1), U/S between left 18th and 17th ribs showing part of splenic base (2), U/S between left 17th and 16th ribs showing part of splenic base (3), U/S between left 16th and 15th ribs showing small part of splenic base and stomach (4) and U/S between left 15th and 14th ribs showing small part of splenic base and stomach (5).

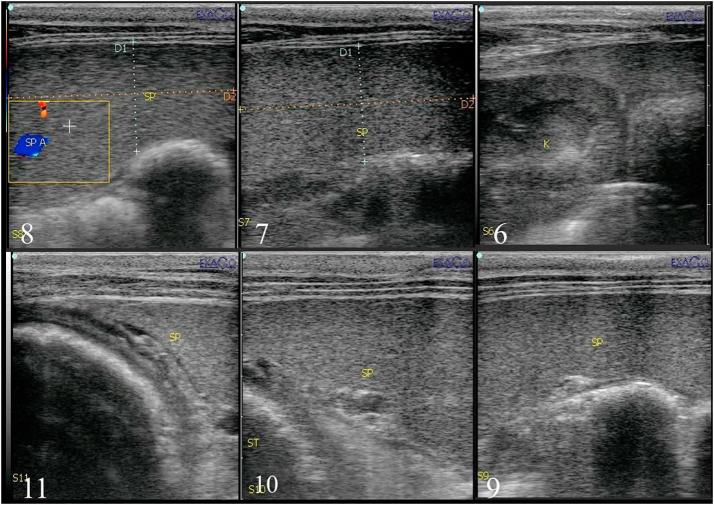

Fig. 4.

Splenic ultrasonography at the left flank region caudal to left 18th rib showing small part of spleen and left kidney (6), U/S between left 18th and 17th ribs showing part of splenic body (7), U/S between left 17th and 16th ribs showing spleen and splenic artery (8), U/S between left 16th and 15th ribs showing splenic body (9), U/S between left 15th and 14th ribs showing splenic body and stomach (10) and U/S between left 14th and 13th ribs showing small part of splenic body and stomach (11).

Fig. 5.

Ultrasonography in the middle part of left flank region showing intestine (12), U/S at the flank region under left 18th rib showing small part of spleen and intestine (13), U/S between left 17th and 16th ribs showing splenic body (14), U/S between left 16th and 15th ribs showing splenic body (15), U/S between left 17th and 16th ribs showing splenic body (16), U/S between left 14th and 13th ribs showing splenic body (17), U/S between left 13th and 12th ribs showing splenic body (18), U/S between left 12th and 11th ribs showing splenic body (19) and U/S between left 11th and 10th ribs showing splenic body (20).

Fig. 6.

Ultrasonography of the most lower part of left flank region showing intestine (21), (22), (23) and spleen appeared at the level of lower abdomen between left 16th and 15th ribs (24), U/S between left 15th and 14th ribs showing splenic apex (25), U/S between left 14th and 13th ribs showing splenic apex (26), U/S between left 13th and 12th ribs showing splenic apex (27), U/S between left 12th and 11th ribs showing splenic apex (28), U/S between left 11th and 10th ribs showing splenic apex (29) and U/S between left 10th and 9th ribs showing splenic apex (30).

During surgery, total splenectomy following resection of the left 17th rib in standing position appeared to be more accessible than that following resection of the left 16th rib in standing position.

4. Discussion

Different studies have been carried out to identify the most suitable surgical approach of total splenectomy in equine [3]. The risk factors were opening the diaphragm, narrow or far surgical field, and handling of voluminous spleen without injuries. Ultrasound is a noninvasive method to detect the location and extension of different soft organs within the body in addition to their architectures. The authors designed the present work to record the normal ultrasound parameters of the spleen in donkeys in order to select the best surgical approach for total splenectomy in donkeys depending on ultrasound topographic location of the spleen and its vasculature. To the authors’ knowledge, no available literature about the ultrasonography of the normal spleen in donkeys was reported.

The topographic location of the ultrasonographic examined donkey’s spleen was recorded in the present work among 4 rows which were divided into 30 squares; each of them was marked by the intercostal spaces. This area covered the whole spleen and his correlations with neighboring organs. From the obtained ultrasound findings, the spleen was homogenously echogenic and appeared hyperechoic to the left kidney. Similar findings were recorded in the horse [3], [4].

As regards the surgical techniques of total splenectomy, several authors have mentioned that the left paralumbar approach caudal to the 18th rib was the most preferable approach [9]. Others described splenectomy after resection of the left 16th, 17th and 18th ribs in recumbent position [8], [18], [20], [21] and after resection of the left 17th rib in standing position [19]. Moreover, Witzel and Mullenax [26] described splenectomy after resection of the last 3 ribs. Along the present study, partial resection of the left 16th and 17th ribs has been tried in the standing position.

From the obtained results of comparison between both approaches of total splenectomy, splenectomy following partial resection of the left 17th rib performed in standing position was similar to that described by Tantawy et al. [19]. This technique appeared to be better than that performed in recumbent position because of sinking of viscera in the abdominal cavity during standing position gives easy handling of the spleen and its vessels. This result is in agreement with that recorded by Said et al. [27]. Meanwhile this technique is also more convenient than that performed after partial resection of the left 16th rib in standing position. This may be due to sinking of the spleen in viscera leaving blood vessels behind the site of the incision. From our results, there is no difference in total splenectomy in horse and donkey and this is similar to that described by Roberts and Grondykt [17] and Rigg et al. [20].

5. Conclusions

From the ultrasound obtained results, the normal splenic parenchyma in donkeys was revealed homogenously echogenic which appeared more hyperechoic than left kidneys. Only one third of the spleen was located in front of the left 16th rib where the hilus and splenic blood vessels were nearly under the left 16th rib. The splenic vein was visible near the gastrosplenic space. The splenic artery after originating from celiac artery and the splenic vein before emptying into the portal vein were ultrasonographically visualized at square no. (8) which was located between the left 16th and 17th ribs 10–15 cm from the dorsal mid line. This area was the site of the most important ligation during total splenectomy. Ultrasonography guidance for total splenectomy in donkeys proved that technique following partial resection of the left 17th rib at the standing position was the most convenient surgical approach for total splenectomy in donkeys.

Competing interests

All authors declare no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University.

References

- 1.Sgorbini M., Bonelli F., Rota A., Baragli P., Marchetti V., Corazza M. Hematology and clinical chemistry in amiata donkey foals from birth to 2 months of age. J Equine Vet Sci. 2012;33:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Getachew A., Burden F., Wernery U. Common infectious diseases of working donkeys: their epidemiological and zoonotic role. J Equine Vet Sci. 2016;39:S107. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alsop E.J., Marr C., Barrelet A.B., Mcgladdery A.J. The use of transabdominal ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of splenic lesions in three horses. Equine Vet Educ. 2007;19:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reef V.B. WB Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 1998. Equine Diagnostic Ultrasound; pp. 273–363. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman S.L. Diagnostic ultrasonography of the mature equine abdomen. Equine Vet Educ. 2003;15:319–330. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy M.F., Lavoie J.P., Deschamps I., Laverty S. Splenic infarction and splenectomy in a jumping horse. Equine Vet J. 2000;32:174–176. doi: 10.2746/042516400777591516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortved K.F., Witte S., Fleming K., Nash J., Woolums A.R., Peroni J.F. Laparoscopic-assisted splenectomy in a horse with splenomegaly. Equine Vet Educ. 2008;20:357–361. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muurlink M.A., Walmsley J.F., Savage C.J., Whitton R.C. Splenectomy in a foal to control intra-abdominal haemorrhage caused by splenic rupture. Equine Vet Educ. 2008;20:362–366. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Seeber F., McAuliffe S.B., McGovern F., Defeo J. Splenic rupture and splenectomy in a foal. Equine Vet Educ. 2008;20:367–370. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steiner J.V. Splenic rupture in the horse. Equine Pract. 1981;3:37–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spier S., Arlson G.P., Nyland T.G., Snyder J.R., Fischer P.E. Splenic hematoma and abscesses a cause of chronic weight loss in a horse. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986;189:557–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaffin M.K., Schmitz D.G., Brumbaugh G.W. Ultrasonographic characteristics of splenic and hepatic lymphosarcoma in three horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1992;201:743–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanimoto T., Yamasaki S., Ohtsuki Y. Primary splenic lymphoma in a horse. J Vet Med Sci. 1994;56:767–769. doi: 10.1292/jvms.56.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGorum B.C., Young L.E., Milne E.M. Nonfatal subcapsular splenic hematoma in a horse. Equine Vet J. 1996;28:166–168. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1996.tb01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ringger N.C., Edens L., Bain P., Raskin R.E., Larock R. Acute myelogenous leukemia in a mare. Aust Vet J. 1997;75:329–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1997.tb15702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Southwood L.L., Schott H.C., Henry C.J., Kennedy F.A., Hines M.T., Geor R.J. Disseminated hemangiosarcoma in the horse: 35 cases. J Vet Intern Med. 2000;14:105–109. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2000)014<0105:dhithc>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts M.C., Grondykt S. Splenectomy in the horse. Aust Vet J. 1978;54:196–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1978.tb02450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dennig H.K., Brocklesby D.W. Splenectomy of horses and donkeys. Vet Rec. 1965;77:40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tantawy M., Bolbol A.E., Samy M.T. Comparative techniques for splenectomy in donkeys. Assiut Vet Med J. 1981;8:15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rigg D.L., Reinertson E.L., Buttrick M.L. A technique for elective splenectomy of Equidae using a transthoracic approach. Vet Surg. 1987;16:389–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1987.tb00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madron M.S., Caston S.S., Reinertson Ez, Tracey A.K., Hostetter J.M. Diagnosis and treatment of a primary splenic lymphoma in a mule. Equine Vet Educ. 2011;23:606–611. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Camacho A.T., Guitian F.J., Pallas E., Gestal J.J., Olmeda A.S., Habela M.A. Theileria (Babesia) equi and Babesia caballi infections in horses in Galicia, Spain. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2005;37:293–302. doi: 10.1007/s11250-005-5691-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knottenbelt D.C., editor. Equine Formulary. Saunders; 2006. pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dugdale A. John Wiley & sons; USA: 2011. Veterinary anesthesia principals to practice; pp. 247–278. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auer JA, Stick JA. Equine surgery. fourth edition. 2012, pp. 393-400.

- 26.Witzel D.A., Mullenax C.H. A simplified approach to splenectomy in the horse. Cornell Vet. 1964;54:628–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Said A.H., Mahfouz M.F., Youssef A.H. Splenectomy in the donkey. Egypt J Vet Sci. 1983;6:12–13. [Google Scholar]