Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to assess the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) and its determinants.

Methods

A cross-sectional questionnaire survey was conducted on 300 newly diagnosed patients with CRC in China’s Heilongjiang province, measuring HRQoL using the EuroQol five-dimension five-level (EQ-5D-5L). Kruskal-Wallis analyses were performed to identify the independent variables associated with the EQ-5D-5L utility scores. Predictors of the utility scores were confirmed using a Tobit regression model.

Results

The respondents had a mean EQ-5D-5L utility score of 0.617 (SD=0.371) and a median of 0.740 (range: −0.348 to 1.000). Pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression were major concerns of the respondents, with a prevalence of over 60% (all levels inclusive). The Kruskal-Wallis analyses found lower utility scores in those who were not married, worked as a farmer, enrolled with the new rural cooperative medical scheme and had lower household income (p<0.05). Those who were at a later stage of CRC, underwent surgical only therapy and had a stoma also had lower EQ-5D-5L scores than others (p<0.05). The Tobit regression model confirmed these predictors, except for occupation and marital status.

Conclusion

Patients with CRC have poor HRQoL, with pain/discomfort and depression/anxiety as the most frequently reported problems. The poor HRQoL is associated with the seriousness of the disease condition, as well as the low socioeconomic status of the patients.

Keywords: health-related quality of life, colorectal cancer, eq-5d-5l

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study estimated EuroQol five-dimension five-level utility scores for patients with colorectal cancer, which can be used for health economic evaluations.

Tobit regression model was established to determine the predictors of the utility scores derived from the censored data.

The cross-sectional design prevented us from drawing causal conclusions.

The study was conducted in three tertiary hospitals in one province, which may limit the generalisability of its findings.

The sample was likely to bias towards more patients with advanced cancer.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers in the world: the third in prevalence (after lung and breast cancer) and the fourth in mortality (after lung, liver and gastric cancer). It was estimated that 746 298 new cases of CRC were diagnosed in 2012 and 693 881 patients died from CRC worldwide.1 A higher incidence of CRC was found in developed nations (29.2 per 100 000 inhabitants in Europe, Northern America, Australia, New Zealand and Japan) compared with their less developed counterparts (11.7 per 100 000 inhabitants in Africa, Asia (excluding Japan), Latin America and the Caribbean, Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia).2 However, China has a level of CRC incidence almost on par with the developed nations, with 376 300 new cases being diagnosed alone in 2015 (27.4 per 100 000 inhabitants). Most patients with CRC live in China.3 CRC has become the fifth leading cause of cancer death in China (around 191 000 patients with CRC died in 2015: 13.9 per 100 000 inhabitants).3

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a patient-reported outcome, which has been increasingly used to support clinical and public health decisions.4 Assessing patient-reported outcomes is particularly important for cancer research because of the complexities of cancer events and cancer treatment. Cancer treatment is often very expensive with limited prospects of remission. Patient-reported outcomes present an alternative option of evidence for decision-making.5 6

However, the application of patient-reported outcomes has been compounded by its subjective nature. People’s preferences need to be considered in quantifying and interpreting the results of patient-reported outcomes. Some researchers argue that people with different experiences (such as those with and without cancer) may have different preferences in relation to the same health state.7 Nevertheless, the use of public preference to assess patient-reported outcomes has prevailed in health economic studies. This approach simplifies the preference scoring algorithm and justifies decisions from the perspective of a more representative population.

Several HRQoL instruments are available with a scoring system based on public preference, such as the EuroQol five-dimension (EQ-5D),8 the Health Utilities Index9 and the Short-Form Six-Dimension survey.10 Their scoring algorithms are all anchored on 1.0 (full health) and 0 (death), with a negative score representing a health state worse than death.

The EQ-5D is perhaps the most widely used instrument for assessing HRQoL based on public preference. It has been recommended by many researchers and governmental agencies.11 Extensive studies have been undertaken using the EQ-5D-3L for assessing HRQoL12–16 because a scoring algorithm based on the preference of the general public is available in many countries, such as Finland,12 Turkey,13 the UK14 and the Netherlands.16 These include some studies on patients with CRC.12–18 Although a few studies have been conducted in China investigating the HRQoL of patients with CRC,19 most have failed to generate a preference-based score simply because of the absence of a scoring algorithm.

The EQ-5D-5L was developed based on its predecessor EQ-5D-3L. It expanded the number of combined health states and is therefore believed to be more sensitive for detecting clinically important differences in HRQoL.20 Recently, a scoring algorithm for the EQ-5D-5L was developed from a representative sample of the adult general population in China.21 This study used the EQ-5D-5L to assess the HRQoL of patients with CRC.

Methods

Study subjects and data collection

A cross-sectional questionnaire survey was conducted in Heilongjiang province, Northeastern China, a province with a population of about 38 million. Heilongjiang ranks in the middle range in China in terms of its socioeconomic development, with US$6386 per capita gross domestic product in 2015.22

Three major centres for cancer treatment, located in the capital city of Heilongjiang province, participated in the study. They were affiliated to a medical university and provided specialist care to patients with cancer across the entire province.

Data were collected between December 2016 and April 2017. The newly diagnosed patients with CRC who received treatment in the three centres over the period were invited to enrol in this study. The participants had to have a confirmed diagnosis of primary CRC; have not received any treatment from other hospitals; be able to read, write and speak in Chinese; and be able to give informed consent. Those who were deemed incapable of completing the questionnaire due to physical or psychological difficulties were excluded from the study.

The survey was conducted while the participants stayed in the hospitals. A list of eligible participants was provided by the hospitals. But the survey was administered by trained interviewers, who had no servicing relationship with the patients. The interviewers were recruited from research students in a medical university.

Eight trained interviewers approached the eligible participants and explained the purpose of this study. Written informed consent was obtained prior to the survey. The questionnaires were completed through face-to-face interviews in a private office, unless the participants requested an interview in the ward. Respondents were encouraged to complete the questionnaire independently, with assistance from the interviewers being made available if requested. The interviewers collected and reviewed the questionnaires immediately once they were returned. The results will be fed back to the patient and asked him/her to complete missing items if needed.

A total of 346 eligible participants were confirmed by the interviewers. Of these eligible participants, 26 declined to participate (including 15 who were deemed incapable of completing the questionnaire due to physical and psychological difficulties); 10 were excluded because they were not made aware of their diagnoses; 10 were excluded due to missing critical information in relation to the EQ-5D-5L data and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the respondents. This resulted in a final sample size of 300. On average, the respondents completed the survey 26 days after diagnosis (SD=15 days; range: 2–61 days).

Patient and public involvement

This study used an existing survey instrument. Patients were not involved in the recruitment to and conduct of the study. The utility scores were estimated based on public preference and were not disseminated to the study participants. Publications of the results will be made open to the public. However, we are not able to disseminate the publications to the patient participants individually simply because we did not record the contact details of the patients.

Measurement

The survey consisted of the validated Chinese version of EQ-5D-5L, and the clinical features and socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents.

Dependent variable: EQ-5D-5L score

The HRQoL of the respondents was assessed by the EQ-5D-5L, which has been validated in patients with cancer.23 It measures problems in five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension was rated along a five-level scale: no problem, slight problem, moderate problem, severe problem and extreme problem.24 Responses to the five dimensions generated 3125 (55) combinations of HRQoL states, with ‘11111’ indicating ‘no problems at all’ and ‘55555’ indicating ‘extreme problems’ in all five dimensions. Each combination was then be given a single score using a scoring algorithm based on public preference. In health economics, this is usually called the ‘utility score’. In this study, we used the Chinese EQ-5D-5L value set21 to estimate the utility score for each respondent, which ranged from −0.391 to 1.000.

Independent variables

Independent variables that might be associated with the HRQoL of patients with CRC were determined with reference to several systematic reviews,25–27 including the clinical features and socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents. Data on the clinical features of the respondents were collected through a review of medical records, which included the stage of CRC (I, II, III, IV), therapeutic regimen (surgery, radiotherapy/chemotherapy, surgery followed by postoperative chemotherapy, chemotherapy followed by surgery) and the presence of a stoma (yes or no). The sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents were collected through the questionnaire survey, which included gender, age, religion, ethnicity, education, marital status, occupation, medical insurance and household income.

Statistical analysis

The EQ-5D-5L utility scores of respondents followed a non-normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p<0.05). We presented both mean (SD) and median (range) scores and applied Kruskal-Wallis analyses to determine the differences in the utility scores of the respondents with different characteristics.

We then established a Tobit regression model on the EQ-5D-5L utility scores, including all of the independent variables that showed statistical significance (p<0.05) in the Kruskal-Wallis analyses. The ceiling effect is common in HRQoL studies, in which a significant number of respondents report the highest score.28–30 This is particularly evident with the EQ-5D instruments,30 31 leading to some utility scores censored at 1.0. In this study, 16.7% of respondents scored the highest possible score 1.0. A general linear regression model is inappropriate for censored data because the values do not necessarily represent the exact values once they reach the censored threshold. For censored data, the Tobit regression model is advised.28–30 32 33

All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS V.18 and the STATA V.12.0. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered an indication of statistical significance.

Results

The respondents had a mean age of 59 years (ranging from 28 to 84 years). The majority was men (65%), married (90%), ethnic Han (96%) and had no religious belief (94%). About 17% of the respondents had obtained a university degree. All of the respondents were covered by social health insurance, although across three different schemes. Their household income was higher compared with the average level (¥27 830) in Heilongjiang. About half of the respondents were still in the paid workforce at the time of the survey. More than half (54%) of respondents had received surgical treatment, but only 16.33% had a stoma. Most patients were at stage II (37.0%) and stage III (38.0%) of CRC (table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of respondents

| Characteristic | N | % |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 195 | 65.00 |

| Female | 105 | 35.00 |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤40 | 50 | 16.67 |

| 50–59 | 92 | 30.67 |

| 60–69 | 105 | 35.00 |

| ≥70 | 53 | 17.66 |

| Religious belief | ||

| Yes | 18 | 6.00 |

| No | 282 | 94.00 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Han | 288 | 96.00 |

| Other | 12 | 4.00 |

| Level of education | ||

| Primary school or below | 64 | 21.33 |

| Junior high school | 103 | 34.34 |

| Senior high school | 82 | 27.33 |

| University | 51 | 17.00 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 270 | 90.00 |

| Other | 30 | 10.00 |

| Occupation | ||

| Public sector employee | 38 | 12.67 |

| Private sector employee | 36 | 12.00 |

| Self-employed or unemployed | 55 | 18.33 |

| Farmer | 63 | 21.00 |

| Retired | 108 | 36.00 |

| Health insurance | ||

| Basic medical insurance for urban employees | 154 | 51.33 |

| Basic medical insurance for urban residents | 62 | 20.67 |

| New rural cooperative medical scheme | 84 | 28.00 |

| Annual household income (¥) | ||

| <20 000 | 56 | 18.67 |

| 20 000–39 999 | 84 | 28.00 |

| 40 000–59 999 | 72 | 24.00 |

| 60 000–79 999 | 39 | 13.00 |

| >80 000 | 49 | 16.33 |

| Therapeutic regimen | ||

| Surgery | 163 | 54.33 |

| Radiotherapy/chemotherapy | 44 | 14.67 |

| Surgery followed by postoperative chemotherapy | 51 | 17.00 |

| Chemotherapy followed by surgery | 18 | 6.00 |

| Other | 24 | 8.00 |

| Stage of colorectal cancer | ||

| I | 40 | 13.33 |

| II | 111 | 37.00 |

| III | 114 | 38.00 |

| IV | 35 | 11.67 |

| Stoma | ||

| Yes | 49 | 16.33 |

| No | 251 | 83.67 |

| Total | 300 | 100 |

Problems in pain/discomfort were most frequently reported (60%, all levels inclusive), followed by anxiety/depression (59%, all levels inclusive), usual activities (53%, all levels inclusive), self-care (49%, all levels inclusive) and mobility (46%, all levels inclusive). About 16.7% of respondents reported no problems at all in all five dimensions (table 2).

Table 2.

Problems reported by respondents in the five dimensions of EuroQol five-dimension five-level

| Problems | Mobility (%) | Self-care (%) | Usual Activity (%) | Pain/discomfort (%) | Anxiety/depression (%) |

| No | 53.7 | 51.0 | 46.7 | 39.7 | 40.7 |

| Slight | 14.3 | 15.4 | 18.3 | 25.0 | 23.3 |

| Moderate | 11.3 | 12.0 | 13.3 | 25.3 | 24.3 |

| Severe | 10.0 | 11.3 | 12.0 | 7.0 | 9.3 |

| Extreme | 10.7 | 10.3 | 11.7 | 3.0 | 2.4 |

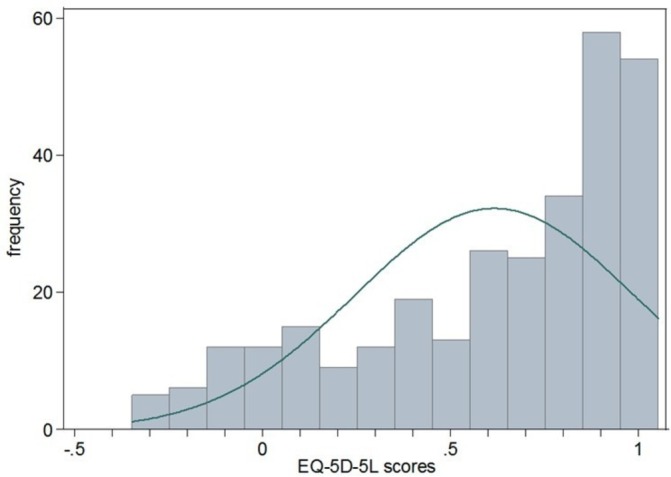

The respondents had an average utility score of 0.617 and a median of 0.740 (table 3). The distribution of the EQ-5D-5L utility scores skewed towards the right higher values (figure 1). No significant differences in the utility scores were found in those of a different age, gender, ethnicity, religious belief and level of education (p>0.10). The Kruskal-Wallis analyses found lower EQ-5D-5L utility scores in those who were not married, worked as a farmer, enrolled with the new rural cooperative medical scheme (NRCMS) and had lower income (p<0.05). The EQ-5D-5L utility scores also varied with clinical characteristics. Those who were at a later stage of CRC, had undergone surgical treatment only and had a stoma had lower utility scores compared with the others (p<0.05).

Table 3.

EuroQol five-dimension five-level index scores in respondents with different characteristics

| N | Mean±SD | Median (range) | P values | |

| Sex | 0.942 | |||

| Male | 195 | 0.614±0.378 | 0.731 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| Female | 105 | 0.621±0.361 | 0.751 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| Age | 0.330 | |||

| ≤49 | 50 | 0.561±0.398 | 0.670 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| 50–59 | 92 | 0.686±0.327 | 0.819 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| 60–69 | 105 | 0.592±0.373 | 0.687(−0.251–1.00) | |

| ≥70 | 53 | 0.598±0.407 | 0.782 (−0.265–1.00) | |

| Religious belief | 0.537 | |||

| Yes | 18 | 0.612±0.375 | 0.740 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| No | 282 | 0.683±0.302 | 0.772 (0.139–1.00) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.166 | |||

| Han | 288 | 0.620±0.374 | 0.749 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| Other | 12 | 0.541±0.307 | 0.618 (−0.044–0.89) | |

| Level of education | 0.180 | |||

| Primary school or below | 64 | 0.581±0.363 | 0.646 (−0.298–1.00) | |

| Junior high school | 103 | 0.583±0.376 | 0.661 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| Senior high school | 82 | 0.638±0.373 | 0.744 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| University | 51 | 0.696±0.365 | 0.833 (−0.201–1.00) | |

| Marital status | 0.026 | |||

| Married | 270 | 0.635±0.359 | 0.746 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| Other | 30 | 0.452±0.445 | 0.455 (−0.348–0.95) | |

| Occupation | 0.007 | |||

| Public sector employee | 38 | 0.734±0.341 | 0.895 (−0.201–1.00) | |

| Private sector employee | 36 | 0.706±0.328 | 0.833 (−0.184–1.00) | |

| Self-employed or unemployed | 55 | 0.603±0.359 | 0.659 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| Farmer | 63 | 0.500±0.411 | 0.600 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| Retired | 108 | 0.621±0.326 | 0.756 (−0.201–1.00) | |

| Health insurance | 0.001 | |||

| Basic medical insurance for urban employees | 154 | 0.674±0.352 | 0.825 (−0.251–1.00) | |

| Basic medical insurance for urban residents | 62 | 0.645±0.354 | 0.720 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| New rural cooperative medical scheme | 84 | 0.490±0.392 | 0.586 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| Annual household income (¥) | 0.002 | |||

| <20 000 | 56 | 0.505±0.419 | 0.586 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| 20 000–39 999 | 84 | 0.566±0.369 | 0.685 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| 40 000–59 999 | 72 | 0.625±0.375 | 0.763 (−0.251–1.00) | |

| 60 000–79 999 | 39 | 0.691±0.300 | 0.824 (−0.044–1.00) | |

| >80 000 | 49 | 0.759±0.315 | 0.882 (−0.201–1.00) | |

| Therapeutic regimen | 0.000 | |||

| Surgery | 163 | 0.517±0.389 | 0.600 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| Radiotherapy/chemotherapy | 44 | 0.757±0.271 | 0.830 (−0.071–1.00) | |

| Surgery followed by postoperative chemotherapy | 51 | 0.712±0.359 | 0.848 (−0.298–1.00) | |

| Chemotherapy followed by surgery | 18 | 0.734±0.320 | 0.847 (−0.005–1.00) | |

| Other | 24 | 0.748±0.274 | 0.854 (0.120–1.00) | |

| Stage of disease | 0.001 | |||

| I | 40 | 0.768±0.296 | 0.893 (0.025–1.00) | |

| II | 111 | 0.656±0.344 | 0.821 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| III | 114 | 0.562±0.394 | 0.698 (−0.265–1.00) | |

| IV | 35 | 0.495±0.395 | 0.637(−0.348–1.00) | |

| Stoma | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 49 | 0.408±0.397 | 0.409 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| No | 251 | 0.657±0.353 | 0.808 (−0.348–1.00) | |

| Total | 300 | 0.617±0.371 | 0.740 (−0.348–1.00) |

Figure 1.

Distribution of the EQ-5D-5L utility scores of patients with CRC. CRC, colorectal cancer; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol five-dimension five-level.

The Tobit regression model confirmed that low household income, membership of the NRCMS, a later stage of CRC, surgical only therapy and the presence of a stoma were significant predictors of low EQ-5D-5L utility scores. However, occupation and marital status became statistically insignificant in predicting utility scores after controlling for other factors (table 4).

Table 4.

Results of Tobit regression model on EuroQol five-dimension five-level index scores of respondents

| Variables | Regression coefficient | 95% CI | P values |

| Marital status (ref=other) | |||

| Married | 0.128 | −0.010 to 0.267 | 0.070 |

| Occupation (ref=retired) | |||

| Public sector employee | 0.069 | −0.073 to 0.210 | 0.340 |

| Private sector employee | 0.073 | −0.069 to 0.215 | 0.313 |

| Self-employed or unemployed | 0.011 | −0.139 to 0.163 | 0.879 |

| Farmer | 0.104 | −0.080 to 0.288 | 0.265 |

| Health insurance (ref=new rural cooperative medical scheme) | |||

| Urban employees basic medical insurance | 0.126 | −0.047 to 0.299 | 0.152 |

| Urban residents basic medical insurance | 0.157 | 0.001 to 0.313 | 0.049* |

| Stage of disease (ref=I) | |||

| II | −0.203 | −0.342 to −0.065 | 0.004** |

| III | −0.329 | −0.468 to −0.192 | 0.000*** |

| IV | −0.626 | −0.809 to −0.444 | 0.000*** |

| Annual household income(ref≥80 000) | |||

| <20 000 | −0.261 | −0.422 to −0.100 | 0.002** |

| 20 000–39 999 | −0.220 | −0.358 to −0.081 | 0.002** |

| 40 000–59 999 | −0.155 | −0.294 to −0.016 | 0.029* |

| 60 000–79 999 | −0.145 | −0.306 to −0.015 | 0.076 |

| Therapeutic regimen (ref=other) | |||

| Surgery | −0.261 | −0.423 to −0.098 | 0.002** |

| Radiotherapy/chemotherapy | 0.135 | −0.057 to 0.326 | 0.167 |

| Surgery followed by postoperative chemotherapy | 0.177 | −0.166 to 0.202 | 0.849 |

| Chemotherapy followed by surgery | 0.053 | −0.178 to 0.284 | 0.653 |

| Stoma (ref=no) | |||

| Yes | −0.224 | −0.337 to −0.111 | 0.000*** |

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Discussion

This study presents the utility scores for newly diagnosed patients with CRC measured by the EQ-5D-5L. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind in China. The results can be used for health economic evaluations of clinical and public health interventions on CRC. Previous attempts on cost–utility analyses of CRC interventions have been deterred by the lack of such utility scores.5 The findings of this study provide baseline health utility values for patients with CRC, which can be used by researchers in calculating quality-adjusted life years, an indicator essential for health economic evaluations, including cost–utility analyses. The study also revealed clinical and socioeconomic factors associated with the utility scores of patients with CRC, which can help clinical and policy decision-makers to better allocate resources.

This study found that patients with CRC live with significantly lower HRQoL than the local general public as measured by the EQ-5D utility scores (0.617 vs 0.959).30 This finding is consistent with previous studies.12 14 18 The CRC respondents of our study also appear to have lower utility scores than those from Finland (0.813)12 Japan (0.842–0.865)34 35 and the UK (0.79).15 However, the interpretation of such differences needs to be cautious because the utility scores of the local general population in China and those in Finland, Japan and the UK were derived from the EQ-5D-3L. Empirical evidence shows that the EQ-5D-5L has a lower ceiling effect and higher discriminatory power than the EQ-5D-3L.12 15 23 30 In addition, the clinical and socioeconomic characteristics of our patients with CRC may also differ from those of other studies. Our sample was drawn from three tertiary hospitals and these patients tend to have more advanced diseases.36 This study captured the utility scores of patients with CRC soon after their diagnoses (26 days on average), much earlier than those of the studies in Finland (6–8 months),12 Turkey (6 months after chemotherapy)13 and England (12–36 months).14

We found that pain/discomfort is the most frequently reported problem (60%, all levels inclusive) of respondents, similar to that reported by patients with CRC in the Netherlands and the UK.16 This study also revealed that 59% of patients with CRC experienced anxiety/depression. Indeed, anxiety/depression is perhaps the most common psychological problem among all patients with cancer.37 38 Further efforts should be made to improve the management of pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression.

There is some debate about the association between HRQoL and the stage of CRC. We found a decreasing trend in HRQoL with the progress of CRC, consistent with those reported in Australia and some European countries.26 39–41 However, CK Wong and colleagues reported worse HRQoL in patients with stage II CRC compared with those in stage III and IV.18

Patients with CRC undergoing surgical procedures often have lower HRQoL.26 42 Our study provides additional evidence for this conclusion. It is widely accepted that surgical procedures are usually associated with increased pain/discomfort, complications and inconvenience in daily activities. However, it is not clear why surgery in combination with other treatment measures can produce a higher utility score than surgery alone. The presence of a stoma is a clear indication of poor HRQoL. An HRQoL instrument (mCOH-QOL-Ostomy) has been developed specifically for patients with CRC with a stoma.43

Low socioeconomic status is a significant predictor of low HRQoL in patients with CRC. In this study, household income and social health insurance entitlements were found to be associated with the HRQoL of patients with CRC, consistent with findings of previous studies conducted in China19 and some other countries.39 40 Medical treatment for CRC is very expensive. A survey of 37 tertiary hospitals in 13 provinces in China revealed a high level of catastrophic expenditure for patients with CRC.44 This is a particular concern for those living with low income and those with limited insurance entitlements. Although China has achieved universal health insurance coverage, considerable disparities exist in terms of entitlements across the three government subsidised basic health insurance programmes covering rural residents, urban residents and urban employees, respectively.45 Rural patients in China are more likely to have lower household income, and are least protected by their health insurance coverage. The NRCMS, launched in 2003, is characterised by voluntary enrolment, low premium contribution (about US$20 per person in 2016) and fixed governmental subsidies (about US$60 per person in 2016). These led to high population coverage of insurance at the cost of limited benefits. The rural insured usually bear a higher proportion of out-of-pocket expenses than their urban counterparts.

This study has several limitations. As a cross-sectional survey, no causal relationships can be assumed. The study was conducted in three tertiary hospitals in one province, which is not a representative sample of China; hence, generalisation of the results needs to be cautious. It is also important to note that the sample was drawn from hospital settings and was biased towards more patients with advanced cancer.46

In conclusion, this study presents utility scores for patients with CRC measured by the EQ-5D-5L. Patients with CRC have poor HRQoL, with pain/discomfort and depression/anxiety as the most frequently reported problems. The low HRQoL of patients with CRC is associated with more advanced stages of CRC, the presence of a stoma and surgery only treatment. But low socioeconomic status, such as low levels of income and insurance entitlements, is also a predictor of low HRQoL.

Ethical statements and consent to participate

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are most grateful to the study participants.

Footnotes

WH and JY contributed equally.

Contributors: JY participated in the design of the study and the writing of the manuscript. WH designed the study, performed the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. GL and CL supervised and interpreted the statistical findings and wrote the manuscript. YL helped draft the manuscript. WF, LS and XZ conceived the study and participated in the design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (Grant No.71503062, 71673071), the Heilongjiang Postdoctoral Fund (Grant No. LBH-Z16137, LBH-Z16240), the China Postdoctoral Fund (Grant No. 2017M611402), the Key Lab of Health Technology Assessment, National Health and Family Planning Commission of China (Fudan University) (Grant No. FHTA2017-08).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Public Health College of Harbin Medical University (Code: HMUIRB2014012).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

- 1. Ferlay JSI, Ervik M, Dikshit R, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.1, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kuipers EJ, Grady WM, Lieberman D, et al. Colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015;1:15065 10.1038/nrdp.2015.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:115–32. 10.3322/caac.21338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ravens-Sieberer U. Measuring and monitoring quality-of-life in population surveys: Still a challenge for public health research. Sozial- und Präventivmedizin 2002;47:203–4. 10.1007/BF01326397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang W, Liu G, Zhang X, et al. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening protocols in urban Chinese populations. PLoS One 2014;9:e109150 10.1371/journal.pone.0109150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Drummond MF SM, Torrance GW, O’Brien B, et al. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 3rd ed New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greenberg D, Earle C, Fang CH, et al. When is cancer care cost-effective? A systematic overview of cost-utility analyses in oncology. Value in Health 2010;102:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996;37:53–72. 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feeny D, Furlong W, Boyle M, et al. Multi-attribute health status classification systems. Pharmacoeconomics 1995;7:490–502. 10.2165/00019053-199507060-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kharroubi SA, Brazier JE, Roberts J, et al. Modelling SF-6D health state preference data using a nonparametric Bayesian method. J Health Econ 2007;26:597–612. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Räsänen P, Roine E, Sintonen H, et al. Use of quality-adjusted life years for the estimation of effectiveness of health care: A systematic literature review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2006;22:235–41. 10.1017/S0266462306051051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Färkkilä N, Sintonen H, Saarto T, et al. Health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 2013;15:e215–e222. 10.1111/codi.12143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Polat U, Arpacı A, Demir S, et al. Evaluation of quality of life and anxiety and depression levels in patients receiving chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: impact of patient education before treatment initiation. J Gastrointest Oncol 2014;5:270–5. 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2014.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Downing A, Morris EJ, Richards M, et al. Health-related quality of life after colorectal cancer in England: a patient-reported outcomes study of individuals 12 to 36 months after diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:616–24. 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.6539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilson TR, Alexander DJ, Kind P. Measurement of health-related quality of life in the early follow-up of colon and rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2006;49:1692–702. 10.1007/s10350-006-0709-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stein D, Joulain F, Naoshy S, et al. Assessing health-state utility values in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a utility study in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014;29:1203–10. 10.1007/s00384-014-1980-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hornbrook MC, Wendel CS, Coons SJ, et al. Complications among colorectal cancer survivors. Med Care 2011;49:321–6. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820194c8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wong CK, Lam CL, Poon JT, et al. Clinical correlates of health preference and generic health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal neoplasms. PLoS One 2013;8:e58341 10.1371/journal.pone.0058341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang JW, Sun L, Ding N, et al. The association between comorbidities and the quality of life among colorectal cancer survivors in the people’s Republic of China. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:1071–7. 10.2147/PPA.S100873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Quality of Life Research 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luo N, Liu G, Li M, et al. Estimating an EQ-5D-5L value set for china. Value Health 2017;20:662–9. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. HPBo S. Heilongjiang Statistical Yearbook. Peking: China Statistics Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim SH, Kim HJ, Lee SI, et al. Comparing the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L in cancer patients in Korea. Qual Life Res 2012;21:1065–73. 10.1007/s11136-011-0018-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. EuroQol Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bours MJ, van der Linden BW, Winkels RM, et al. Candidate predictors of health-related quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors: A systematic review. Oncologist 2016;21:433–52. 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Der BWAL V. Predictors of health-related quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors: a systematic literature review, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hu X, Gong Y, Wang C, et al. The quality of life for patient with colorectal neoplasm and its influential factors. Tumor 2003:343–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan VH. EQ-5D Scores for diabetes-related comorbidities. Value Health 2016;19:1002–8. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan VH, Globe G, et al. Health-related quality of life associated with systemic corticosteroids. Qual Life Res 2017;26:1037–58. 10.1007/s11136-016-1435-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang W, Yu H, Liu C, et al. Assessing Health-Related Quality of Life of Chinese Adults in Heilongjiang Using EQ-5D-3L. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:224 10.3390/ijerph14030224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bharmal M, Thomas J, Tj R. Comparing the EQ-5D and the SF-6D descriptive systems to assess their ceiling effects in the US general population. Value Health 2006;9:262–71. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Twisk J, Rijmen F. Longitudinal tobit regression: a new approach to analyze outcome variables with floor or ceiling effects. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:953–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tran BX, Ohinmaa A, Nguyen LT. Quality of life profile and psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L in HIV/AIDS patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:132 10.1186/1477-7525-10-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hamashima C. Long-term quality of life of postoperative rectal cancer patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;17:571–6. 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02712.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kameyama H, Shimada Y, Yagi R, et al. [Quality of life of patients after colorectal cancer surgery as assessed using EQ-5D-5L scores]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 2017;44:1083–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gao K, Gan X. MEdical units distribution and influence factors on the selection of patients. Chinese Health Service Management 2014;31:516–7. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, et al. Emotional distress in cancer patients: The edinburgh cancer centre symptom study. Br J Cancer 2007;96:868–74. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. So WK, Marsh G, Ling WM, et al. Anxiety, depression and quality of life among Chinese breast cancer patients during adjuvant therapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2010;14:17–22. 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Paika V, Almyroudi A, Tomenson B, et al. Personality variables are associated with colorectal cancer patients' quality of life independent of psychological distress and disease severity. Psychooncology 2010;19:273–82. 10.1002/pon.1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sharma A, Sharp DM, Walker LG, et al. Predictors of early postoperative quality of life after elective resection for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:3435–42. 10.1245/s10434-007-9554-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rinaldis M, Pakenham KI, Lynch BM. Relationships between quality of life and finding benefits in a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Br J Psychol 2010;101:259–75. 10.1348/000712609X448676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chambers SK, Meng X, Youl P, et al. A five-year prospective study of quality of life after colorectal cancer. Qual Life Res 2012;21:1551–64. 10.1007/s11136-011-0067-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu L, Herrinton LJ, Hornbrook MC, et al. Early and late complications among long-term colorectal cancer survivors with ostomy or anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum 2010;53:200–12. 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181bdc408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huang H-Y, Shi J-F, Guo L-W, et al. Expenditure and financial burden for common cancers in China: a hospital-based multicentre cross-sectional study. The Lancet 2016;388:S10 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31937-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dong K. Medical insurance system evolution in China. China Economic Review 2009;20:591–7. 10.1016/j.chieco.2009.05.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yang SM, Li JY, Gale RP, et al. The mystery of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): Why is it absent in Asians and what does this tell us about etiology, pathogenesis and biology? Blood Rev 2015;29:205–13. 10.1016/j.blre.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.