Abstract

Objectives

Unrecognised malposition of the endotracheal tube can lead to severe complications in patients under general anaesthesia. The purpose of this study was to verify the feasibility of using ultrasound to measure the distance between the upper edge of saline-inflated cuff and the vocal cords.

Design

Prospective case-control study.

Setting

A tertiary hospital in Beijing, China.

Methods

In this prospective study, 105 adult patients who required general anaesthesia were enrolled. Prior to induction, ultrasound was used to identify the position of the vocal cords. After intubation, the endotracheal tube (ETT) was fixed at a depth of 23 cm at the upper incisors in men and 21 cm in women. The depth of intubation was verified by video-assisted laryngoscopy. The distance between the upper edge of the saline-inflated cuff and the vocal cords was measured by ultrasound; the ideal distance was considered to be 1.9–4.1 cm.

Results

Among the 105 cases, two cuffs were too close to the vocal cords and one too far away from the vocal cords. These diagnoses were made by ultrasound and were in agreement with results from direct laryngoscopy. The overall accuracy of ultrasound in identifying malposition of the cuff was 100.0% (95% CI: 96.6% to 100%). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of ultrasound were, respectively, 100% (95% CI: 96.5% to 100%), 100% (95% CI: 29.2% to 100%), 100% (95% CI: 96.5% to 100%) and 100% (95% CI: 29.2% to 100%).

Conclusion

Identification of the upper edge of the saline-inflated cuff and the vocal cords by ultrasound to assess the location of the ETT is a reliable method. It can be used to avoid malposition of the ETT cuff and reduce the incidence of vocal cords injury after intubation.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR-DDD-17011048.

Keywords: adult anaesthesia, intratracheal intubation, ultrasonography, vocal cord

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Previous studies on intubation depth were mainly focused on how to avoid too deep intubation.

The hazard of too shallow intubation was often neglected.

We found that the distance between the vocal cord and the upper edge of ETT cuff can be measured with the aid of ultrasonography.

This method might be useful to avoid malposition of the ETT cuff and reduce the incidence of vocal cords injury after intubation.

The technical limitations include the difficulty in fitting the ultrasound prove to the surface of prominent Adam’s apple and 5–8 min to complete the examination procedure.

Introduction

Tracheal intubation is a routine procedure of resuscitation and general anaesthesia. The appropriate depth of endotracheal intubation should be confirmed after intubation and during surgery because a malposition of endotracheal tube (ETT) can lead to serious complications. Placing the tube too deeply may stimulate the carina, and unrecognised endobronchial intubation may result in single-lung ventilation, hypoxaemia and atelectasis of the non-ventilated lung.1 On the other hand, if the ETT is placed too shallowly, the tube cuff’s impingement on the vocal cords may lead to vocal cords injury, compression of the recurrent laryngeal nerve and even accidental extubation.2

An optimal ETT placement should ensure sufficient distance (2–5 cm) between the tip of the ETT and the carina3 and sufficient distance (1.5–2.5 cm) between the proximal margin of the cuff to the vocal cords.2 4 Most ETTs for the adults have two black insertion guide marks at 2 and 4 cm above the cuff or one mark at 2–3 cm above the cuff.5 Alignment of the marks with the vocal cords helps to place the ETT at the correct depth.6 However, this technique relies on visualisation of the vocal cords with a laryngoscope (ie, grade I or II view). A large tongue, prominent teeth, a short neck or blood and secretions may make visualisation of the ETT’s position within the glottis difficult. Besides, under some circumstances, such as using blind intubation or a Shikani or Bonfil optical stylet to guide intubation, the depth markers cannot be observed.

Under such circumstances, intubation depth is commonly determined according to experience, usually 23 cm for male and 21 cm for female patients.7–9 After intubation, auscultation of breath sounds is routinely performed to confirm the location of the tube. If endobronchial intubation is suspected, the tube must be withdrawn until bilateral breath sound can be heard. However, auscultation of breath sounds can be unreliable,10 and blind withdrawal of the tube can be hazardous for patients with short tracheas. In some patients, the distance from the vocal cords to the carina is identical to or even shorter than the distance from the ETT tip to the insertion guide mark.6 This means that there would not be enough cuff free zone below the vocal cords when breath sounds can be heard from both sides in patients with short tracheas.

Cuff palpation has been suggested as a tactile method to estimate the position of the EET,11 12 but its accuracy is influenced by the thickness of the soft tissue of the anterior neck and the experience of the operator.13 Furthermore, a high-volume low-pressure cuff may not be palpable despite correct placement. One study has shown that cuff palpation has only a 26% specificity for indicating incorrect ETT placement.14 The development of ultrasonography has made it possible to identify the ETT cuff more accurately. In 1987, Raphael and Conard, for the first time, obtained a clear image of a saline-inflated cuff by ultrasound.15 Previous studies used ultrasonic images of saline-inflated cuffs at or above the suprasternal notch as indicators of appropriate ETT insertion depth.16 However, as in the case of auscultation, observing the cuff at or above the suprasternal notch can rule out too deep intubation but not too shallow intubation.

Since both the vocal cords and the ETT cuff can be visualised using ultrasound, a safe distance between the vocal cords and the ETT cuff can potentially be guaranteed by ultrasonography. We hypothesised that ultrasound can be used to estimate the distance between the upper edge of the ETT cuff and the vocal cords in adults so that the depth of the ETT can be adjusted accordingly. The purpose of this study was to review instances of endobronchial intubation and estimate the occurrence of too short a distance between the cuff and vocal cords in adult Chinese using the 23/21 rule and also to determine the feasibility of using ultrasound to measure the distance between the upper edge of saline-inflated cuff and the vocal cords.

Materials and methods

Study participants

Patients aged 18–70 years who were scheduled for elective cervical surgery under general anaesthesia from October 2016 to May 2017 were recruited in this prospective case-control study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The exclusion criteria included difficult airway (Mallampati classification 3 and 4, mouth opening <3 cm), abnormal airway or chest anatomy and a history of cervical trauma or cervical surgery.

Equipment and researchers

A reinforced ETT with a 7.0 or 8.0 mm inner diameter (ID) (Covidien Mallinckrodt, USA), with two insertion guide marks was used in the present study, which involved four investigators: an anaesthesiologist experienced in airway ultrasonography using a 38 mm 6–13 MHz linear ultrasound probe (Turbo SonoSite HFL, Bothell, Washington, USA), an anaesthesiologist experienced in fibreoptic bronchoscopy (FOB), a senior resident and an anaesthetic assistant. The two anaesthesiologists who performed the ultrasound and FOB examinations were blind to the results of laryngoscopy.

Ultrasound assessment of vocal cords

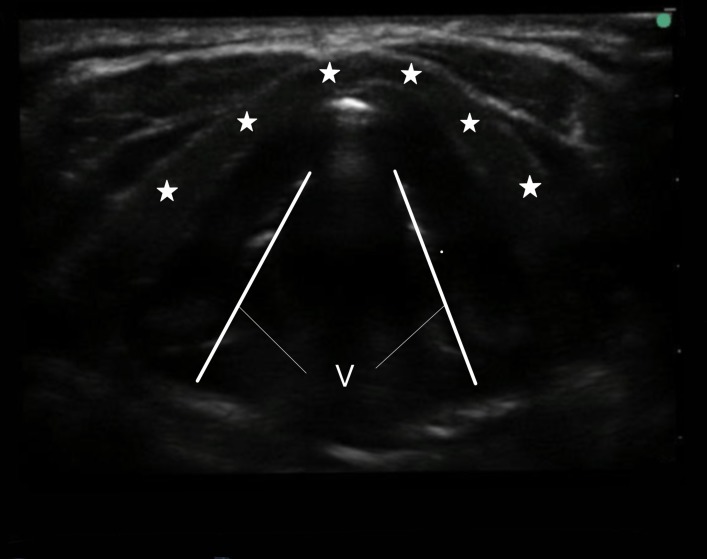

When the patient reached the operation room, routine monitors (pulse oximeter, non-invasive blood pressure cuff and ECG) were placed. The patient was in a neutral position. The ultrasound probe was placed transversely on the neck perpendicular to the skin. The probe was moved cranially or caudally until the true vocal cords could be identified (figure 1). Along the midpoints of the short axis of the probe, line A was drawn on the patient’s skin (figure 2) to mark the position of true vocal cords. If the vocal cords could not be clearly identified, the patient was excluded.

Figure 1.

Transverse scan over the glottis. Asterisks, thyroid cartilage; V, vocal cords.

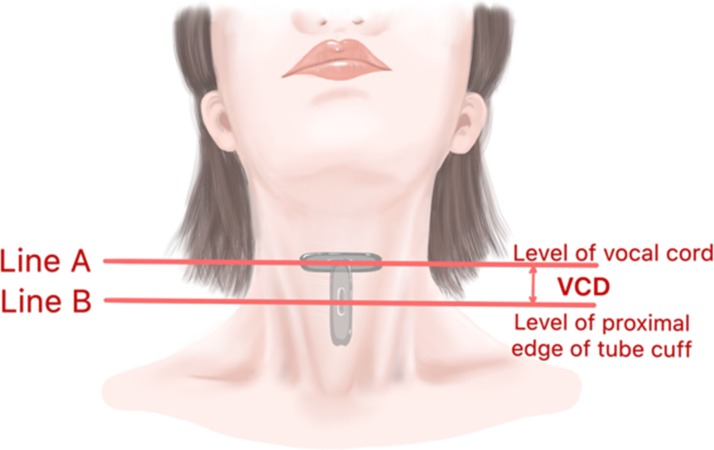

Figure 2.

Demonstration of probe placement. Line A, probe placed at the level of vocal cord; line B, probe placed at the level of proximal edge of tube cuff. VCD, vocal cords-cuff distance.

Intubation

Following the induction of anaesthesia, an ETT (7.0 mm ID for females, 8.0 mm ID for males) was inserted by the resident and the insertion depth was determined using the 23/21 cm rule (23 cm at the upper incisor teeth in men and 21 cm in women) using a video-assisted laryngoscope (Zhejiang UE Medical, Tai Zhou, China). The ETT was held in place by the assistant, then the position of the vocal cords relative to the depth markers was verified under video laryngoscopy. If the vocal cords could not be seen, the patient would be excluded. Once the vocal cords were seen, the ETT was connected to the ventilator for mechanical ventilation and anaesthesia was maintained with propofol 6–8 mg/kg/hour.

Measurements

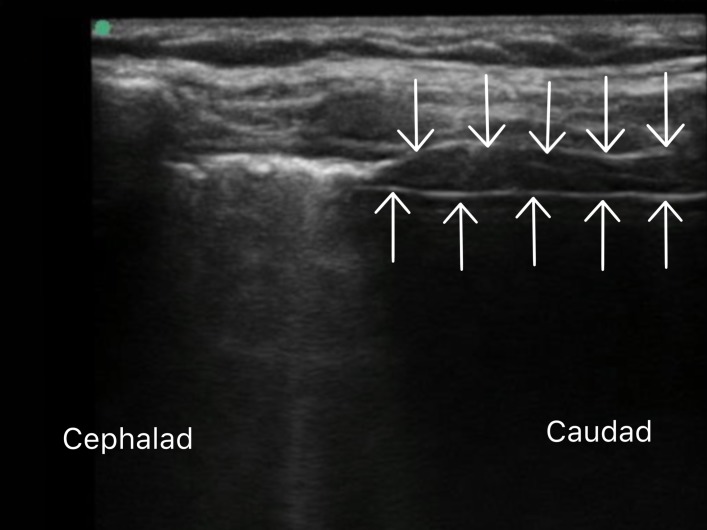

The ultrasound probe was placed sagittal on the neck, perpendicular to the skin and above the suprasternal notch. The ETT cuff was then inflated with 8 mL of saline. A pressure gauge was used to measure the cuff pressure; if the pressure exceeded 30 cmH2O, the patient would be excluded. After the injection of saline, two parallel hyperechogenic lines would appear on ultrasound screen, as shown in figure 3. The upper line represented the anterior wall of cuff, and the lower line represented the anterior wall of ETT. The junction of these two lines or the proximal starting point of the upper line represented the proximal margin of the cuff. Then the probe was moved along the midline of the neck until an image of the proximal margin of the cuff appeared at the centre of the screen. Line B (figure 2) was then drawn on the skin along the midpoints of the long axis of the probe. The distance between lines A and B (AB), representing the distance between the vocal cords and the proximal edge of the cuff (VCD), was measured. Then a towel was placed to cover the neck. With the ventilator disconnected, the tip-carina distance and the incisors-carina distances were measured17 by the an anaesthesiologist, who was blind to the marks on patient’s neck, using a 2.8 mm FOB (TIC-SD-I, Zhejiang UE Medical). For patients with suitable VCDs (1.9–4.1 cm), the saline was drawn out of the cuff and the cuff filled with the proper amount of air. Finally, the tube was secured with tape. For patients with unsuitable VCDs (<1.9 or >4.1 cm), the saline was drawn out of the cuff and the tube moved cephalad or caudally based on the calculated distance to get the desired VCD. Then the video-assisted laryngoscope was again used to confirm the relative position of the glottis and the two insertion guide marks.

Figure 3.

Longitudinal view of the intubated trachea, with the cuff of the endotracheal tube inflated with saline. Arrows pointing downwards—anterior wall of the cuff. Arrows pointing upwards—anterior wall of the endotracheal tube.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. Study reports will be disseminated to investigators and patients through this open-access publication.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was the accuracy of the ultrasound image confirming the proper depth of the ETT. The distance between the proximal margin of the cuff and the first and second insertion guide marks of the ETT was 2±0.1 and 4±0.1 cm, respectively. The depth by ultrasound was defined as correct (AB distance between 1.9 and 4.1 cm), too shallow (AB distance <1.9 cm) or too deep (AB distance >4.1 cm). The depth was also defined by video-assisted laryngoscopy as correct (vocal cords lying between the two insertion guide marks), too shallow (both marks above vocal cords) or too deep (both marks below vocal cords). Both too shallow and too deep placements were considered to be incorrect.

According to the results of preliminary tests, an accuracy of 90% was considered acceptable; to obtain an α error of 0.05 and a statistical power of 0.8, the calculated sample size was 102 patients using PASS V.11.0 (NCSS, Kaysville, Utah, USA) software. A total of 120 patients were recruited to provide for potential dropouts. SPSS V.20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for data management. The normality of data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were expressed as the mean±SD and compared between genders using Student’s t-test. Non-normally distributed variables were expressed as the median (range) and analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Ultrasound was compared with the gold standard of HC video-assisted laryngoscopy as a diagnostic test; accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated. The corresponding 95% CIs were calculated based on the Clopper-Pearson method in SAS V.9.4 (SAS, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Agreement between ultrasound and video-assisted laryngoscopy was evaluated by the kappa consistency test. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

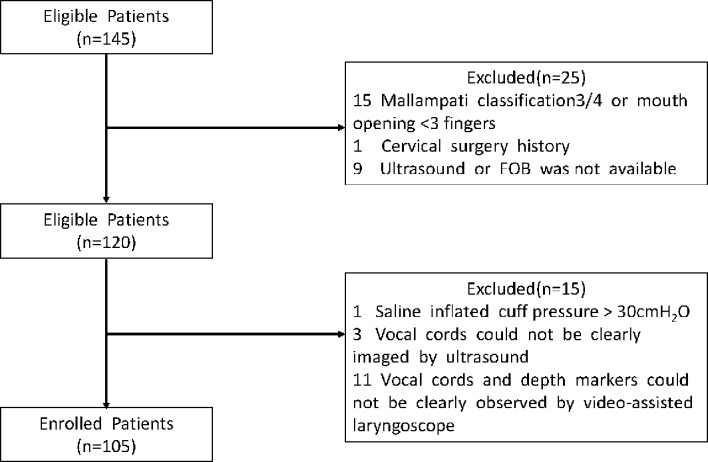

A total of 120 patients were initially enrolled in the study and 105 were included in the final analysis. Figure 4 presents the allocation process. The demographic data of the 105 patients who completed the trial are presented in table 1. The differences in height, weight and thyromental distance between males and females were statistically significant (p<0.05). There was no significant difference in VCD detected by ultrasound and the tip-carina distance detected by FOB between males and females (table 1).

Figure 4.

Allocation process. FOB, fibreoptic bronchoscopy.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Total (n=105) | Female (n=62) | Male (n=43) | P values (male vs female) | |

| Age (year) | 53 (20, 69) | 53 (20, 69) | 54 (20, 65) | 0.757 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.0±9.8 | 60. 6±8.9 | 68.9±8.7 | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 164.8±8.5 | 160.0±6.6 | 171.7±5.9 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 23.0 (17.0, 33.7) | 22.8 (18.8, 33.7) | 23.1 (17.0, 30.9) | 0.669 |

| VCD (cm) | 2.9±0.6 | 2.9±0.6 | 3.0±0.6 | 0.607 |

| TCD (cm) | 3.6 (1.3, 6.4) | 3.4 (1.3, 6.4) | 3.6 (1.9, 6.4) | 0.124 |

Variables are presented as mean±SD (range) or median (range).

BMI, body mass index; TCD, tip-carina distance; VCD, vocal cords-cuff distance.

It took about 30 s to 1 min to find the vocal cords and mark on the skin, and it took another 3–5 min to finish the rest of the procedure, from filling the cuff with saline to withdrawing FOB. The ventilator was stopped for no more the 20 s during FOB examination, and no change in SpO2 was found. The diagnoses of too shallow an intubation for one female and one male and too deep an intubation for one female made by ultrasound was in agreement with the diagnoses made by direct laryngoscopy. The data on these patients are shown in table 2. After inserting the tube forward for about 1.5 cm, the glottis in each of the two shallow intubation patients lay between the two depth makers as confirmed by video-assisted laryngoscopy. After pulling the tube up about 1 cm, the glottis position of the deep intubation patient was also corrected. The distances from the ETT tip to the carina measured by FOB were between 1.3 and 6.4 cm with no statistical difference between males and females. This distance was <2 cm for a total of one male and eight female patients. Except for the no. 3 patient in table 2, the tubes were not withdrawn. For these eight patients, fibreoptic bronchoscopy was performed during surgery to ensure no endobronchial intubation occurred.

Table 2.

Data of the three patients with incorrect insertion depth

| Patient | VCD (cm) | Sex | Age (year) | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | BMI (kg/m2) | TCD (cm) |

| 1 | 1.1 | M | 20 | 188 | 80 | 22.6 | 6.4 |

| 2 | 1.4 | F | 61 | 162 | 60 | 22.8 | 3.3 |

| 3 | 4.4 | F | 61 | 152 | 52 | 22.5 | 1.3 |

BMI, body mass index; TCD, tip-carina distance; VCD, vocal cords-cuff distance.

Using video-assisted laryngoscopy as the standard criterion (table 3), the overall accuracy of ultrasound was 100.0% (95% CI: 96.6% to 100%), with a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI: 96.5% to 100%), a specificity of 100% (95% CI: 29.2% to 100%), PPV 100% (95% CI: 96.5% to 100%) and NPV 100% (95% CI: 29.2% to 100%), and 100.0% (95% CI: 96.6% to 100%) in detecting the correct position of the ETT. Overall, the correct identification of tracheal versus bronchial intubation was 100.0% (95% C: 96.6% to 100%). The kappa value was 1.

Table 3.

Results of ultrasound vs video-assisted laryngoscope

| Video-assisted laryngoscope | ||

| Ultrasound | Positive | Negative |

| Correct | 102 | 0 |

| Incorrect | 0 | 3 |

Video-assisted laryngoscope: identifying the relationship of vocal cords and depth markers. Positive: vocal cords lied between two depth markers; otherwise it is negative. Ultrasound: identifying the distance between upper edge of cuff and the glottis. Correct: the distance between upper edge of cuff and glottis was in the range of 1.9–4.1 cm; otherwise it is incorrect.

Discussion

Among the 105 cases using the 23/21 rule, two cuffs were too close to the vocal cords and one too far away from the vocal cords. The diagnoses of too deep intubation and too shallow intubation made by ultrasound were in agreement with direct laryngoscopy. The distances measured by ultrasound had high accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV for identifying the position of ETT at the level of the glottis. It was also found that malposition of the ETT could be corrected based on the results of ultrasound.

Unlike previous studies, which were mainly focused on the avoidance of too deep an intubation, the safety of the vocal cords was concerned as a priority in our study. We believe that for most adults, ETT cuff impingement on the vocal cords or compression of the recurrent laryngeal nerve are more harmful—and more readily ignored—than endobronchial intubation.

In an early study, Cavo2 pointed out that the rigid thyroid lamina was lateral to the anterior branch of the recurrent laryngeal nerve; they suspected that the vulnerable point of the recurrent laryngeal nerve lay between 6 and 10 mm below the posterior end of the free edge of the vocal cord. Several studies have shown that extension of the neck and concomitant movement of the ETT was a risk factor for vocal cord injury owing to neck extension during withdrawal of the ETT from the trachea (1.9 cm in the study by Conrardy et al,3 1.7±0.8 cm in the study by Kim et al 18 and 0.9±0.9 cm in the study by Hartrey and Kestin5). Under external force, the withdrawal distance of the ETT is increased.19 Since the cuff-free area of 2–4 cm below the vocal cords can be guaranteed by observing the insertion guide marks, this criterion was adopted as the standard for correct ETT positioning in the present study.

Our study showed that in using 23/21 rule, the rate of correct ETT positioning was as high as 97.1%. In only one male patient and one female, the tube insertion was considered to be too deep. Some anaesthesiologists suggested that it would be safer to use a 22/20 rule for Asian people to avoid endobronchial intubation.9 20 However, if the 22/20 rule had been used in our study, the number of patients with a VCD <1.9 cm would have increased to 12, with a greater risk of harmful impingement of the cuff on the vocal cords.

In our study, the VCD was measured with ultrasound. Although some studies have used FOB to make sure that the ETT cuff was 2–3 cm below the vocal cords,21 22 we found it difficult to identify the cuff and the vocal cords via FOB when the ETT was already in place. We used direct video-assisted laryngoscopy to verify the position of the vocal cords with respect to the ETT cuff. Although a quantitative measurement could not be achieved with laryngoscopy, agreement on correct position of ETT using two these two methods can still be justified.

With the increasing popularity of ultrasound use in the field of anaesthesia, several studies have used ultrasound to help confirm the depth of intubation. McKay et al 23 observed an ultrasound image of tracheal ring undulation caused as the ETT was advanced and considered it as an indication of proper ETT depth. Actually, such an image can only be regarded as a sign of endotracheal intubation. Uya et al 24 defined adequate ETT placement as complete visualisation of the saline-injected ETT cuff at the suprasternal notch. Similarly, Tessaro et al 16 considered that ultrasonography of the saline-inflated cuff at the suprasternal notch represented correct ETT insertion depth. Some concern has been raised about how far above the suprasternal notch the cuff should be located.25–27

Our study was the first to use ultrasound to measure VCD. In awake patients, in the ultrasound transverse view, the hyperechoic vocal ligaments can easily be visualised. During phonation, the true cords move towards the midline. Surface projection of the vocal cords can then be marked on the skin after obtaining the optimal image of the true vocal cords. Surface projection of the proximal edge of the cuff can also be marked on the skin, as in the present study. Our results show that this is a reliable method for identifying incorrect intubation depth. Also, adjustment of insertion depth can be made based on the VCD obtained with this method. One can argue that it is needless to measure VCD in every patient intubated with the 23/21 rule. However, for patients whose necks are in extension during surgery, presurgery evaluation of the relative position of the vocal cords and cuff may be necessary. In the present study, although patients with Mallampati classification 3 and 4 and mouth opening less than three fingers were excluded, vocal cords could not be completely exposed using video-assisted laryngoscope on 11 of 120 patients. Measuring the VCD as shown in the present study may serve as an alternative under such circumstances.

Limitations of the study

There are several limitations to our study. First, the number of incorrect tube positions in our study was small. A larger sample size study may be needed to verify our results. Second, for some male patients with prominent Adam’s apples, the probe could not be fully attached to the skin and the vocal cords could not be completely seen. Three male patients were excluded from the study due to unsatisfactory ultrasound images of the glottis. Putting a specially designed water-filled pad or gel-like pad which fits the surface of the probe between the probe and the skin may increase the contact area and enhance ultrasound imaging. Third, although too shallow an intubation can be avoided using the present method, too deep intubation cannot. Using lung ultrasound technique, endobronchial intubation can be determined, and bronchial intubation avoided.21 For patients with extremely short airways, the proper choice is to select an ETT with a short distance from the catheter tip to the upper edge of the cuff. Lastly, although the ultrasound examination was done by experienced anaesthesiologists, it still took 5–8 min to complete the whole examination procedure. Training is needed for inexperienced anaesthesiologists but a study has shown that this technique can be easily learnt.24

Conclusion

Ultrasonography of the upper edge of a saline-inflated ETT cuff appears to be a simple and reliable method for identifying the distance between the vocal cords and the proximal edge of the ETT cuff, and malposition of the ETT can be corrected according to the results of the ultrasound. Confirmation of a safe distance from the upper margin of the cuff to the vocal cords may prevent injury to the vocal cords and recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

XC and WZ contributed equally.

Contributors: ML designed the study and revised the final manuscript as submitted. XC and WZ contributed equally to this paper, and they were both the first authors. XC, WZ, ZY and JG carried out all data collection. XC and WZ carried out data analyses and drafted the initial manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: The study was supported by Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Clinical Application Research and Achievement Program, grant numbers: Z161100000516036).

Disclaimer: The funders were not involved in the study design, data analysis or manuscript preparation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by Peking University Third Hospital Ethics Committee (IRB00006761-2016163).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: A full anonymised dataset is available from the corresponding author on request.

References

- 1. Owen RL, Cheney FW. Endobronchial intubation: a preventable complication. Anesthesiology 1987;67:255–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cavo JW. True vocal cord paralysis following intubation. Laryngoscope 1985;95:1352–9. 10.1288/00005537-198511000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Conrardy PA, Goodman LR, Lainge F, et al. . Alteration of endotracheal tube position. Flexion and extension of the neck. Crit Care Med 1976;4:8–12. 10.1097/00003246-197601000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mehta S. Intubation guide marks for correct tube placement. A clinical study. Anaesthesia 1991;46:306–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1991.tb11504.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hartrey R, Kestin IG. Movement of oral and nasal tracheal tubes as a result of changes in head and neck position. Anaesthesia 1995;50:682–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb06093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chong DY, Greenland KB, Tan ST, et al. . The clinical implication of the vocal cords-carina distance in anaesthetized Chinese adults during orotracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth 2006;97:489–95. 10.1093/bja/ael186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stone D, Gal T. Airway management Miller’s anesthesia. 6th edn Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, 2005:P1431–2. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dorsch J, Dorsch S. Tracheal tubes: understanding anesthesia equipment. 4th edn Baltimore: Williams and Wilki, 1999:589. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mitsuda S, Moriyama K, Yorozu T. Optimal insertion depth of endotracheal tube among Japanese. J Anesth 2014;28:477 10.1007/s00540-013-1739-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vezzani A, Manca T, Brusasco C, et al. . Diagnostic value of chest ultrasound after cardiac surgery: a comparison with chest X-ray and auscultation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2014;28:1527–32. 10.1053/j.jvca.2014.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pattnaik SK, Bodra R. Ballotability of cuff to confirm the correct intratracheal position of the endotracheal tube in the intensive care unit. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2000;17:587–90. 10.1097/00003643-200009000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pollard RJ, Lobato EB. Endotracheal tube location verified reliably by cuff palpation. Anesth Analg 1995;81:135–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McKay WP, Klonarakis J, Pelivanov V, et al. . Tracheal palpation to assess endotracheal tube depth: an exploratory study. Can J Anaesth 2014;61:229–34. 10.1007/s12630-013-0079-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ledrick D, Plewa M, Casey K, et al. . Evaluation of manual cuff palpation to confirm proper endotracheal tube depth. Prehosp Disaster Med 2008;23:270–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raphael DT, Conard FU. Ultrasound confirmation of endotracheal tube placement. J Clin Ultrasound 1987;15:459–62. 10.1002/jcu.1870150706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tessaro MO, Salant EP, Arroyo AC, et al. . Tracheal rapid ultrasound saline test (T.R.U.S.T.) for confirming correct endotracheal tube depth in children. Resuscitation 2015;89:8–12. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cherng CH, Wong CS, Hsu CH, et al. . Airway length in adults: estimation of the optimal endotracheal tube length for orotracheal intubation. J Clin Anesth 2002;14:271–4. 10.1016/S0952-8180(02)00355-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim JT, Kim HJ, Ahn W, et al. . Head rotation, flexion, and extension alter endotracheal tube position in adults and children. Can J Anaesth 2009;56:751–6. 10.1007/s12630-009-9158-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Buckley JC, Brown AP, Shin JS, et al. . A comparison of the haider tube-guard® endotracheal tube holder versus adhesive tape to determine if this novel device can reduce endotracheal tube movement and prevent unplanned extubation. Anesth Analg 2016;122:1439–43. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Falzone E, Hoffmann C, Pasquier P, et al. . Proper depth placement of oral endotracheal tubes in adults: 21/23 cm or 20/22 cm? J Clin Anesth 2012;24:165–6. author reply 66 10.1016/j.jclinane.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ramsingh D, Frank E, Haughton R, et al. . Auscultation versus point-of-care ultrasound to determine endotracheal versus bronchial intubation: a diagnostic accuracy study. Anesthesiology 2016;124:1012–20. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Salem MR. Verification of endotracheal tube position. Anesthesiol Clin North America 2001;19:813–39. 10.1016/S0889-8537(01)80012-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McKay WP, Wang A, Yip K, et al. . Tracheal ultrasound to assess endotracheal tube depth: an exploratory study. Can J Anaesth 2015;62:667–8. 10.1007/s12630-015-0313-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Uya A, Spear D, Patel K, et al. . Can novice sonographers accurately locate an endotracheal tube with a saline-filled cuff in a cadaver model? A pilot study. Acad Emerg Med 2012;19:361–4. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01306.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li Y, Wang J, Wei X. Confirmation of endotracheal tube depth using ultrasound in adults. Can J Anaesth 2015;62:832 10.1007/s12630-015-0359-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mckay WP, Wang A, Yip K, et al. . In reply: Confirmation of endotracheal tube depth using ultrasound in adults. Can J Anaesth 2015;62:833–4. 10.1007/s12630-015-0360-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li Y, Wang J, Wei X. Confirmation of the depth of the endotracheal tube: where should the cuff be? Resuscitation 2015;88:e7 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.