Abstract

Introduction

Patients with cancer often suffer from considerable distress. Life review is a process of recalling, evaluating and integrating life experiences to alleviate a sense of despair and achieve self-integrity. Empirical data have supported the fact that life review is an effective psychological intervention, but it is not always accessible to patients with cancer. There is little evidence of internet-based life review programmes tailored to patients with cancer. This study aims to develop a WeChat-based life review programme and evaluate its effectiveness on the psycho-spiritual well-being of patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy.

Methods and analysis

A single-centre randomised parallel group superiority design will be used. Patients with cancer will be randomised, to either a control group, or to an experimental group receiving a 6-week WeChat-based life review programme. The programme, which was mainly developed based on Erikson’s psycho-social development theory and Reed’s self-transcendence theory, provides synchronous and asynchronous communication modes for patients to review their life. The former is real-time communication, providing an e-life review interview guided by a facilitator online. The latter is not simultaneously dialogic and is used to interact with patients before and after a life review interview through Memory Prompts, Review Extraction, Mind Space and E-legacy products. The primary outcomes include anxiety, depression and self-transcendence, and the secondary outcomes are meaning in life and hope. These will be measured at baseline, and immediately, at 3 months, and at 6 months after the programme’s conclusion.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval has been obtained from the Biological and Medical Research Ethics Committee of the corresponding author’s university (IRB Ref No: 2016/00020). The trial results will be published in a peer-reviewed journal and presented at national and international conferences.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR-IOR-17011998.

Keywords: internet, life review, cancer, nursing, psychological intervention

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a pioneer study to develop and evaluate a theory-based WeChat-based life review programme tailored to patients with cancer with a randomised controlled trial.

This programme is likely unsuitable for people with poor literacy skills, because they may encounter difficulties in viewing the life review modules.

In this type of psychological research, it is not possible to blind all participants to the programme, which may lead to the Hawthorne effect.

This study is a single-centre randomised trial, and the findings may not be generalisable to all settings. Further research in a multi-centre, inter-disciplinary and transregional setting will be necessary.

Introduction

Cancer is a life-threatening disease. By 2025, the number of people dying from cancer each year is expected to increase to 11.4 million, up from the 2015 figure of 8.8 million.1 In China, cancer is the leading cause of death, accounting for 27% of deaths among patients with cancer worldwide.2 A previous study has shown that 27% of the cancer mortality risk is associated with psycho-spiritual distress.3 A meta-analysis has found a dose–response effect, indicating that higher levels of psychological distress are linked to a 41% increased risk of cancer death.4 Psycho-spiritual distress, such as anxiety, depression and hopelessness, is prevalent among patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy.5 Approximately 32.5% to 75.7% of patients with cancer experience psycho-spiritual distress, which is higher than in the population as a whole, as well as higher than in patients with other diseases.6–8 Psycho-spiritual distress may greatly prolong hospitalisation rates,9 interfere with cancer treatment,10 lower rehabilitation effectiveness3 and be related to cancer mortality.3 4

Life review is regarded as a psychological intervention in palliative care. It is defined as a process of recalling, evaluating and integrating life experiences to facilitate the achievement of ego integrity.11 Grounded in Erikson’s psycho-social development theory, life review is structured with guiding questions to assist participants in reviewing each life stage. Reviewing an entire life enables participants to revisit past experiences, retrieve happy feelings from positive memories and release negative emotions lingering from unpleasant events.12 13 It also helps them to reaffirm their contributions and accomplishments, reconcile their failures and disappointments and integrate their entire life into a more acceptable or meaningful whole.12 14 15 Previous studies have explored life review’s effectiveness on psychological distress (ie, anxiety, depression),16 17 spiritual well-being (ie, meaning of life, hope),18 19 and quality of life.20 21 Various reviews have been conducted to synthesise these results, including systematic reviews22 23 and meta-analysis.24 The meta-analysis presented the cumulative evidence from well-designed clinical trials of a life review’s effectiveness on patients with cancer. It suggests that in palliative care, doing a life review could potentially be beneficial and can be integrated into typical cancer care to enhance patients’ psycho-spiritual well-being. Compared with other psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and meaning-centred psychotherapy (MCP), a life review is more feasible for patients with cancer to do. First, reviewing one’s life is a naturally occurring, universal mental process among patients with cancer in the final life stage.25 However, patients are sometimes frustrated, and their feelings can be distorted by negative experiences. In a formal life review, a facilitator will guide patients to reconcile their disappointments. Second, CBT and MCP usually require participants who are capable, at some level, of participating in the activities of daily living. However, Ando et al found that patients with deteriorating health or low functionality can still participate in a life review, even when lying in bed.26

Traditional face-to-face life review is not always available for patients with cancer suffering from psycho-spiritual distress. A systematic review pointed out that life review is commonly undertaken in hospitals, palliative care units or other healthcare institutions. Patients in such settings may lose the opportunity to participate in a life review, due to time conflicts between the life review and medical treatment or nursing care.23 Furthermore, few patients dwelling in community can easily access a life review intervention, due to issues of geographic distance, traffic problems, and limited human resources.

E-health, a recent healthcare practice supported by electronic processes and communication, may be a potential means of overcoming the above-mentioned barriers.27 Research related to online life review has been reported, with two studies focusing on older adults28 29 and one study on patients with cancer.30 In 2009, an e-health system called the Butler Project was developed with the aim of facilitating optimal ageing.31 Using the Butler Project system, Preschl et al conducted life review therapy for depressed older adults with computer-aided supplements.28 The intervention consisted of a face-to-face life review and a computer component to induce positive emotions. This study was performed in a traditional face-to-face setting. Another study, focusing on adults, was a randomised controlled trial to test the effectiveness of life review as online-guided self-help.29 The life review intervention group members received a self-help book to review their lives, followed by an audio-CD that guided them to perform a well-being exercise. Study participants sought support from researchers via email. Although this approach addressed the issue of geographic distance, email contact was not immediate enough for the patients to receive a timely reply. Wise et al designed a life review for patients with cancer using online social networks.30 The intervention combined a telephone interview, a text-form life story and a self-directed website for patients to share their personal story and establish social networks. A randomised controlled trial was then performed to test the intervention’s effectiveness on distress and existential well-being among 68 patients with advanced cancer.32 The study explored patients’ satisfaction with the life review process, social networking use patterns and themes emerging from their life stories; however, the evidence to determine its efficacy was inconclusive. Additionally, telephone interviews did not allow the researchers to observe non-verbal cues, such as patients’ facial expressions and body language. To our knowledge, there is no life review programme tailored to patients with cancer that is completely internet-based, particularly in China.

WeChat is a multi-functional social networking application covering 90% of mobile phones in China. It is used in 200 countries with a capacity to handle more than 20 languages,33 providing the functions of synchronous and asynchronous communication. Synchronous communication is real-time communication between two or more individuals. Asynchronous communication permits a delay between sender and receiver. The sender can transmit data at any time, and the receiver can read it whenever he or she wants. WeChat users can interact asynchronously with each other through text messaging, voice messaging, video conferencing and so on, and they can obtain information and browse resources from all kinds of WeChat platforms at any time. Due to its synchronous and asynchronous communication functions, WeChat has increasingly been used in nursing education and continuous nursing, as well as in other areas.34 35Therefore, we aimed to develop a WeChat-based life review programme (WBLRP), and test the effectiveness of this programme on psycho-spiritual well-being among patients with cancer. We hypothesised that patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy who received the WBLRP would see a significant difference in their mean scores of anxiety, depression, self-transcendence, meaning of life and hope, compared with the control group.

Methods and analysis

Study design

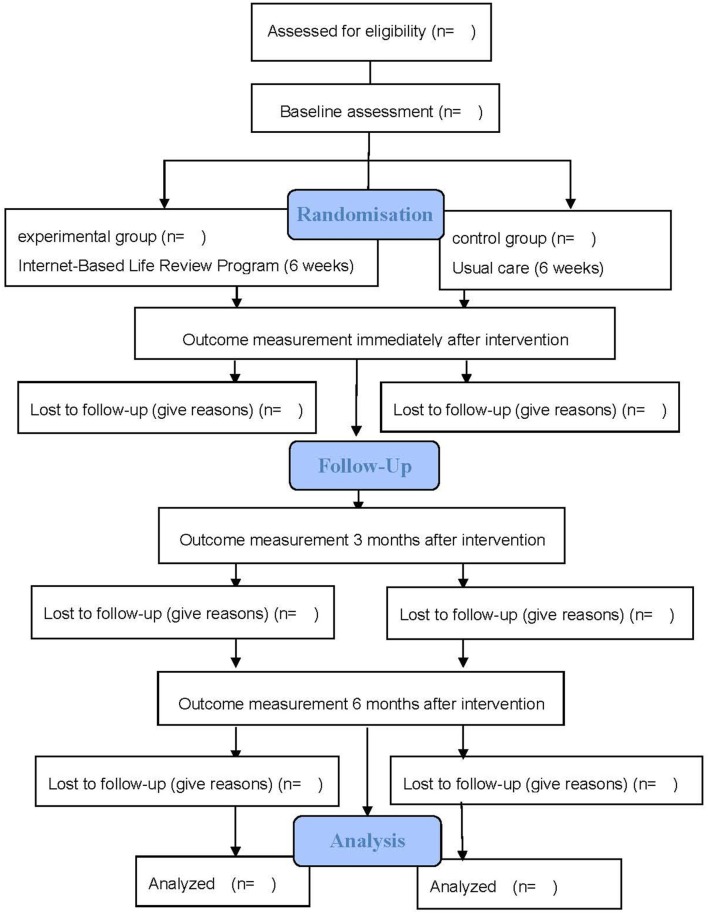

The study is a single-centre randomised parallel group superiority design, consistent with the guidelines of Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations For Interventional Trials.36 This study will follow the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow chart to show the flow of participants through each stage of a randomised controlled trial37(figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart based on Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Participants

Participants will be recruited from two oncology departments at a comprehensive medical university-affiliated hospital that has received a national service quality evaluation in Fujian, south-east China. Cancer types treated in the oncology departments include colorectal, gastric, breast, lung and others, with the exception of haematological and brain cancer, which are treated in other clinical departments. In the two oncology departments, an average of 244 patients with cancer per month receive chemotherapy, and approximately 82% of these patients have access to the internet at home. The inclusion criteria for the participants are: (1) diagnosed with stage III or IV cancer and currently undergoing chemotherapy; (2) aged 18 years or older; (3) aware of their diagnosis and treatment; and (4) able to access the internet via multiple devices, for example, a mobile phone. The exclusion criteria are: (1) currently taking anxiolytics or antidepressants; (2) receiving other psycho-therapeutic treatments; (3) experiencing verbal communication impairment or cognitive impairment, psychiatric disorders and indications of suicide; (4) severely disabled or the disease progressing rapidly (Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) < 40%).

Sample size determination

Sample size calculation is based on power analysis. Power analysis adopts a hypothesis-testing method to determine sample size according to a prespecified significance level and desired power level.38 Assuming a two-tailed alpha of 0.05, a probability of 0.02 for beta error (80% power) and an effect size of 0.42 after calculating anxiety according to the previous study,24 64 participants are required. For depression (effect size 0.52) and self-transcendence (effect size 0.39),24 39 the sample sizes are 30 and 76, respectively. In a larger sample size, 76 patients are needed. Assuming a 20% dropout rate in this study, the total sample size is 92 participants.

Randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding processes

This study will follow the process of randomisation. Before randomisation, a person who is not engaged in the subject recruitment and data collection will prepare a randomisation list with 46 sets of numbers, either 0 (control group) or 1 (experimental group), using the computer software Research Randomizer (http://www.randomizer.org/). These 46 sets of numbers will be printed separately and sealed in each envelope. After recruiting a participant, the facilitator will open an envelope in sequence. The number found in the envelope will represent the group that the particular participant belongs to. In this study, group assignments do not blind participants or the facilitator; instead, they blind data collectors in order to minimise measurement bias.

Intervention

WBLRP development

The WBLRP is an e-life review intervention for patients with cancer reviewing their life in synchronous and asynchronous communication modes. The former is an e-life review interview; the latter are four life review modules, including Memory Prompts, Review Extraction, Mind Space and E-legacy Products. Based on Erikson’s psycho-social development theory, an e-life review interview was developed to facilitate an online life review of each life stage. Erikson states that a healthily developing human should pass through eight developmental stages, from infancy to late adulthood.40 If individuals are able to overcome the developmental crisis at the final life stage, they will achieve ego integrity; otherwise, they will become preoccupied by despair, experience regrets and fear death. Butler’s life review interview is a systematic process that follows Erikson’s life span stages and promotes life integration by recalling, evaluating and integrating positive and negative life experiences.11 Thus, according to Erikson’s theory, the synchronous communication mode aims to guide patients in reviewing their entire life online, from childhood to the present.

Based on Reed’s self-transcendence theory, four life review modules, including Memory Prompts, Review Extraction, Mind Space and E-legacy Products, were designed in the asynchronous communication mode. Self-transcendence is described as the expansion of personal boundaries that is influential in finding meaning and purpose in life, including Outward, Inward, Spirituality and Temporal.41 It is an inherent quality in every human being, which can be a powerful coping strategy when one is faced with adversity.42 Indeed, reviewing a life involves every factor of self-transcendence. In our programme, the four life review modules are designed to enhance self-transcendence. For example, Mind Space is designed to further help patients reveal their innermost feelings, beliefs and what they believe is most meaningful in life, after the life review interview takes place. E-legacy products help patients integrate their past and present: their entire life as a whole.

Additionally, the guiding questions of the life review interview, and images and videos promoting patients’ memories, were drawn from our research team’s previous studies for the WBLRP.43 44

Validation of WBLRP

The WBLRP has been validated by a panel of experts with a two-round Delphi survey. The panellists consisted of three life review researchers, three palliative care nurse specialists, two clinical oncology professors, one social worker and one psychologist. All of them hold a bachelor’s degree or above, and have at least 5 years of work experience in their respective fields. The panellists evaluated the content’s appropriateness and relevance; the programme’s format, frequency and duration; and provided comments based on their experience and knowledge. The Content Validity Index was calculated by the percentage of items rated as ‘relevant’ or ‘very relevant’. It was 90.8% in the first round. According to the experts’ comments, eight guiding questions were adjusted, and two images were added. The Content Validity Index of the second round reached 100%. After the experts’ validation, two patients with cancer were recruited to test whether the WBLRP content was understandable and acceptable.

WBLRP components

E-life review interview is an individual face-to-face interview using the video-call function on WeChat. Four sections will be reviewed weekly over 6 weeks, including present life (cancer experience), adulthood, childhood and adolescence, and summary of life, ordered in a reserve sequence, starting with the present and working backwards. Each section has its corresponding guiding questions. The duration of each life review interview ranges from 40 to 60 min, depending on the patient’s physical condition and willingness to talk. The first author, a nursing postgraduate and registered nurse, who has received approximately 50 hours of life review training, will act as facilitator. Both facilitator and patients can arrange for the interview to be conducted at a convenient time, at any location with access to the internet.

Memory Prompts Module contains various resources, such as images, songs, videos, audio picture books and guiding questions related to the content of each section. These will be presented to patients ahead of the life review interviews in order to evoke their memories. For example, in the Childhood and Adolescence Section, an audio picture book titled, ‘On the Night You Were Born’ opens the prelude to the review. Images of home, studies, games, labour and food display the typical life scenes of that age, while songs about childhood trigger recollections of a person’s past. Patients are encouraged to supplement with other relevant resources (eg, images, songs) according to their individual circumstances. Guiding questions are used to stimulate memories and help patients recall the most important events of their life.

Review Extraction Module refers to a summary of meaningful events created by the facilitator after each section, where patients can review the content and leave their comments. After each life review interview, the facilitator will elicit significant events with relevant images, to help patients clarify the trajectory of each life stage and facilitate self-evaluation.

Mind Space Module provides patients with an opportunity to express their emotions, set down their wishes or reveal their true feelings to those who are important to them. For example, in the Adulthood Section, patients can express their gratitude and thanks to family members or friends. This module allows patients to look within, reconsider and reflect on their relationships with others, and establish a sense of connection with their surroundings beyond their personal boundaries.

E-legacy Products Module presents the products of a family tree, a timeline of life and an e-life review product, which can be preserved as spiritual memorials. The family tree and timeline of life are created by patients under the facilitator’s guidance, during the life review interview. The e-life review product will be created by the facilitator, who selects significant experiences, life views and words for loved ones, along with additional elements such as photos, songs or videos based on patients’ preferences. The e-life review product will be presented to patients to help them re-evaluate and integrate all of their life events and will ultimately serve as a legacy product. This module helps to promote patients’ recollections of their family history and life experiences, as well as to integrate their past, present and their life as a whole.

Intervention procedure and monitoring

Prior to the intervention, patients in the experimental group will be guided to install WeChat, register an account, launch a video call, browse the life review’s memory prompts and operate each module on the WeChat platform. Additionally, a brochure can be consulted. Before each session, patients can access the Memory Prompts Module to obtain an overview of the current session. Subsequently, an appointment for an e-life review interview is arranged. The patients and facilitator can communicate in a virtual face-to-face setting, with additional instant messaging methods available, such as text message, voice message and emotion icons. After the life review interview, patients can access the 24 hours open asynchronous communication modules to relive and integrate the reviewed content, express feelings and deliver e-legacy products, or supplement any content. Generally, each session follows the same process (for more details, please see table 1). When approaching the end of the intervention, the facilitator will create a timeline recording of the life review process that patients will participate in.

Table 1.

An overview of the WeChat-based life review programme

| Session | Section | Asynchronous communication (appreciate memory prompts before the interview) |

Synchronous communication (deliver the e-life review interview) |

Asynchronous communication (go through modules after the interview) |

| 1 | The present (from cancer diagnosis to present) |

|

|

|

| 2&3 | Adulthood (≥18 years old) |

|

|

|

| 4&5 | Childhood and adolescence (<18 years old) |

|

|

|

| 6 | Summary of Life |

|

|

|

During the WBLRP, there will be ongoing monitoring of participants’ physical condition, emotional status, response to life review guiding questions and compliance with the intervention as well as ongoing monitoring of the facilitator’s life review skills. If participants experience negative emotions, a follow-up by a clinical psychologist will be arranged. To protect patient privacy, the life review WeChat platform can only be accessed with a personal WeChat number, and patients can decide which modules may be read by other people.

Comparison

The patients in both the experimental and control groups will receive the usual care provided by the study hospital. Usual care involves personal care, medical care, health education and emotional support. The control group may freely use the internet to search for information. However, they will not have access to the WBLRP.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Anxiety will be measured using the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale.45 The 20-item self-report scale is rated on a four-point score from 1 (seldom) to 4 (most of the time). The total score ranges from 20 to 80, with a score of more than 50 indicating mild to moderate anxiety. The scale is widely used to quantify anxiety levels and has been proven to be reliable among patients with cancer in China (α=0.799).46

The Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale is useful for detecting depression levels.47 This four-point scale also consists of 20 items, with a total score of 80. Patients with a score of more than 53 can be rated as mildly depressed. Good reliability has been shown with Cronbach’s alpha 0.87.48

Self-transcendence will be measured by the Self-Transcendence Scale,41 a 15-item scale, with each item rated from ‘1=not at all’ to ‘4=almost always’. The total score ranges from 15 to 60, calculated by adding all of the individual items together. The Chinese version scale has been validated with high reliability (α=0.83 to 0.87).49

Secondary outcomes

Meaning in life will be measured by the Meaning in Life Questionnaire developed by Steger.50 It consists of 10 items measuring the presence of meaning and the search for meaning. Each item is rated on a seven-point Likert scale from ‘1=strongly disagree’ to ‘7=totally agree’. It has been shown to have good reliability, with internal consistency values between 0.79 to 0.93.51

The Herth Hope Scale will be used to assess the level of hope.52 This is a 12-item scale divided into three dimensions, including temporality and future, positive readiness and expectancy and interconnectedness. Good validity and reliability have been reported among patients with lung cancer, with Cronbach’s alpha value 0.87 and construct validity 0.85.53

Other data

Demographic data, including age, gender, race, marital status, level of education, level of income and cancer information, will be collected using a personal information form.

Patients’ physical function will be evaluated with KPS, which measures palliative care patients' progressive decline in terms of physical condition and exercise tolerance.54 It grades a patient’s general condition with an 11-point scoring system from 0 (death) to 100% (normal). A KPS of less than 40% means the patient is severely disabled, and his/her disease is progressing rapidly. Thus, this study includes patients with a KPS of more than 40%.

Patients’ psychiatric condition will be checked from their medical records, and patients with a psychiatric diagnosis will be excluded from study participation. The indications of suicide will be measured by the Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI).55 SSI was developed in 1979 by Beck, quantifying intensity in suicide ideation. Its Chinese version, this scale has been validated with good reliability (α=0.87).56 The scale has a total of 19 items, and the first five items are used to identify the level of suicidal desire. The five items are rated as follows: no suicidal desire, mild suicidal desire and strong suicidal desire. Patients who rate the fourth or fifth item as mild or strong suicidal desire will not participate in this study.

Data collection

Data will be collected by two research assistants at baseline, and immediately, 3 months, and 6 months after the programme. The research assistants, who are blinded to group assignments, collect patients’ demographic data, and primary and secondary outcome variables. During the investigation, the assistants will ensure the study’s confidential and voluntary nature, and then explain the requirements of each measure. Once patients encounter difficulties in completing the questionnaires, assistants will help them by reading each item aloud, repeating the item if required and recording the participant’s responses.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used for sample characteristics. Parametric or non-parametric tests will be conducted to compare the baseline characteristics of the two groups. If the data collected are normally distributed, the Student’s t-test or the Χ2 test will be performed. Otherwise, non-parametric tests, such as the Wilcoxon test and the Mann-Whitney U test, will be used. Repeated-measures analysis of variance will also be used to analyse the effectiveness of the life review programme. The missing data will be handled using the multiple imputation method.

Data monitoring and interim analyses

Owing to a single-centre trial design and short-term study duration, no data monitoring committee will be established and no interim analyses will be conducted.

Patient involvement

When designing the programme, a panel of experts and two patient advisers were invited to validate the WBLRP. During the programme, patients will be asked to review their life, and draw a family tree and a timeline of their life. After each session, they will be encouraged to involve in Content Extraction and Mind Space. At the end of the WBLRP, a life review product will be given to each patient, containing a record of the patient’s significant life events and experiences. There are no plans to disseminate the randomised controlled study results to study participants.

Ethics and dissemination

This study will adhere to ethical standards for the entire procedure. During participant recruitment, trained research assistants will visit potential participants and explain the study purpose, procedure, benefits and potential risk, and participants’ right to withdraw from the study at any point without negative consequences. Patients will have the opportunity to discuss relevant issues before signing the consent form. The data collected will be stored centrally and kept confidential and anonymous. The data analysis will be conducted by our research team. The investigators will have the capacity to request ancillary analyses 3 years after the trial completion. The data will be used exclusively for this research only.

Dissemination strategies may include a paper submission to a peer-reviewed journal, as well as a conference submission. The research findings will be used to propose a new idea for nursing care using the internet, and for psychological rehabilitation of patients with cancer.

Discussion

Patients with cancer often suffer considerable distress from the disease and from chemotherapy, but cannot always access effective psychological interventions, such as life review, due to geographic distance and traffic issues. Therefore, the proposed intervention protocol is to construct the WBLRP and test its effectiveness on patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy. This is expected to overcome these obstacles and benefit more patients, by improving patients’ psycho-spiritual well-being, and allowing them to achieve a state of self-integration.

The effectiveness of WBLRP may be attributed to its characteristics. First, WBLRP is a theory-based intervention tailored to patients with cancer. Second, it is easily accessible to patients with cancer. Third, five components of WBLRP play a vital role. E-life review interviews allow patients to select a familiar environment where they can review their life, and feel safe and comfortable while revealing intimate, and sometimes painful life experiences.57 Memory prompts may help to awaken patients’ memories and facilitate the life review process. Previous studies have found that memory prompts can trigger patients’ recollections.58 Review Extraction summarises meaningful events in each life stage, to help patients relive life events and promote self-evaluation after the life review interviews. Reliving life events on their own is part of the process of self-evaluation, which is important to the success of the life review.59 Mind Space is an internal process, where patients can look inside themselves, and clarify their personal values, priorities and life meaning.42 Our research team’s previous studies found that patients with cancer wish to reveal their true feelings, which they had not previously shared with others. This module provides an opportunity for patients to express themselves freely, reconsider their relationships with others and establish a sense of connection with their surroundings, beyond their personal boundaries. E-legacy products not only help patients to appreciate their entire life once again but also to leave a personal legacy for their loved ones. The individual e-product is vivid and convenient for patients to review and then pass down, as a legacy handed down from generation to generation. It may also play an important role in helping patients maintain positive emotions for a period of time.23

A number of limitations are acknowledged in this study. First, the programme is likely unsuitable for people with poor literacy skills, because they may encounter difficulties in reading the memory prompts and operating the life review modules. Second, e-life review interviews may lack human contact, compared with face-to-face interventions. Fortunately, texts, emotion icons and other non-verbal information on WeChat can be used to compensate for this shortcoming.60 Third, seen from the perspective of methodological limitations, one issue is a lack of blinding. When not blinded to psychological interventions, participants are prone to generate the Hawthorne effect, and the facilitator may have expectations of the intervention group. However, it is difficult to blind participants and facilitators to treatments in psychological research. Another issue is a potentially high dropout rate. Some patients will probably drop out of the study during the 6 month follow-up, due to the progression of the disease. Finally, this study is a single-centre randomised trial, and the findings may not be generalisable to all settings. Another study with a more rigorous design, with a multi-centre, inter-disciplinary and transregional setting, will be necessary in the future.

If the WBLRP is shown to be effective, it could be integrated into routine cancer care to enhance the psycho-spiritual well-being of patients with cancer. It may be an alternative approach for nurses to deliver a life review intervention to community-dwelling patients with cancer. Additionally, this study could provide a reference for nursing care using the internet, and put forward a new idea for psychological rehabilitation. To the best of the researchers’ knowledge, this is an innovative programme based on a theoretical framework to improve psycho-spiritual well-being among patients with cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the experts for their kind help and insightful advice, and thank the patient advisers in the validation of this program. We would also like to thank Fujian Provincial Nature Science and Fujian Provincial Health Commission for providing funding for this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: HMX undertook the conception of the study, conducted critical revision of the manuscript and obtained funding and supervision. XLZ mainly designed the study and drafted the manuscript. Both authors have reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This study is funded by Fujian Provincial National Nature Science [2017J01814] and Fujian Provincial Health Commission [2017-CX-35].

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Biological and Medical Research Ethics Committee of Fujian University (IRB Ref No: 2016/00020) in July 2017.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. World Health Organization sees cancer risk rising around the world. http://www.mcclatchydc.com/news/nation-world/world/article24760372.html.

- 2. Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:115–32. 10.3322/caac.21338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hamer M, Chida Y, Molloy GJ. Psychological distress and cancer mortality. J Psychosom Res 2009;66:255–8. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Russ TC, Stamatakis E, Hamer M, et al. Association between psychological distress and mortality: individual participant pooled analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2012;345:e4933 10.1136/bmj.e4933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee YP, Wu CH, Chiu TY, et al. The relationship between pain management and psychospiritual distress in patients with advanced cancer following admission to a palliative care unit. BMC Palliat Care 2015;14:69 10.1186/s12904-015-0067-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huang H, Huang JF. Survey of negative emotions among cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Chinese Journal of clinical rehabilitation 2006;10:69–70. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang LM, Zhao SQ, Huang WX. Influence of psychological nursing on cancer patients in chemotherapy. Modern Nursing 2007;13:1375–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lp L, Feng LJ. Evidence-based nursing in cancer the application of the correlation between depression patient care. Nursing Journal of Chinese People’s Liberation Army 2008;18:57–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Calderón J, Campla C, D’Aguzan N, et al. Prevalence of emotional symptoms in Chilean oncology patients before the start of chemotherapy: potential of the distress thermometer as an ultra-brief screening instrument. Ecancermedicalscience 2014;8:437 10.3332/ecancer.2014.437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Korte J, Bohlmeijer ET, Smit F. Prevention of depression and anxiety in later life: design of a randomized controlled trial for the clinical and economic evaluation of a life-review intervention. BMC Public Health 2009;9:250 10.1186/1471-2458-9-250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. BUTLER RN. The life review: an interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Psychiatry 1963;26:65–76. 10.1080/00332747.1963.11023339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Merriam SB. Butler’s life review: how universal is it? Int J Aging Hum Dev 1993;37:163–75. 10.2190/RTKY-8VUD-HBEG-12L8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lamme S, Baars J. Including social factors in the analysis of reminiscence in elderly individuals. Int J Aging Hum Dev 1993;37:297–311. 10.2190/P7AA-8G6M-2T3B-QRP0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kivnick HQ. Remembering and being remembered: the reciprocity of psychosocial legacy. Generations 1996;20:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Taboume CE. The life review program as an intervention for an older adult newly admitted to a nursing home facility: a case study. Therapeutic Recreation Journal 1995;29:228–36. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riepma I, Steunenberg B, Bree R. Power of the past: a randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of a life review therapy in depressed palliative cancer patients. Psycho Oncology 2011;20:219–20.20878845 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Esmaeily M. P8: Efficacy of Life Review Therapy with Emphasis on Islamic Ontology on Decreasing PTSD Symptoms. Neurosci J Shefaye Khatam 2014;2:58. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, et al. Efficacy of short-term life-review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;39:993–1002. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang YC. Effects on self-esteem and hope among cervical cancer patients with life review intervention. Today Nurse 2015;21:73–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xiao H, Kwong E, Pang S, et al. Effect of a life review program for Chinese patients with advanced cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Nurs 2013;36:274–83. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318268f7ba [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hanaoka H, Okamura H. Study on effects of life review activities on the quality of life of the elderly: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom 2004;73:302–11. 10.1159/000078847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Westerhof GJ, Bohlmeijer E, Webster JD. Reminiscence and mental health: a review of recent progress in theory, research and interventions. Ageing Soc 2010;30:697–721. 10.1017/S0144686X09990328 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang X, Xiao H, Chen Y. Effects of life review on mental health and well-being among cancer patients: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;74:138–48. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang CW, Chow AY, Chan CL. The effects of life review interventions on spiritual well-being, psychological distress, and quality of life in patients with terminal or advanced cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Palliat Med 2017;31:883–94. 10.1177/0269216317705101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jenko M, Gonzalez L, Seymour MJ. Life review with the terminally Ill. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing 2007;9:159–67. 10.1097/01.NJH.0000269995.98377.4d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ando M, Tsuda A, Morita T. Life review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2007;15:225–31. 10.1007/s00520-006-0121-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kane K. eHealth and nursing Informatics. Br J Community Nurs 2010;15:157 10.12968/bjcn.2010.15.4.47350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Preschl B, Maercker A, Wagner B, et al. Life-review therapy with computer supplements for depression in the elderly: a randomized controlled trial. Aging Ment Health 2012;16:964–74. 10.1080/13607863.2012.702726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lamers SM, Bohlmeijer ET, Korte J, et al. The efficacy of life-review as online-guided self-help for adults: a randomized trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2015;70:24–34. 10.1093/geronb/gbu030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wise M, Marchand L, Aeschlimann E, et al. Integrating a narrative medicine telephone interview with online life review education for cancer patients: lessons learned and future directions. J Soc Integr Oncol 2009;7:19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Botella C, Etchemendy E, Castilla D, et al. An e-health system for the elderly (Butler Project): a pilot study on acceptance and satisfaction. Cyberpsychol Behav 2009;12:255–62. 10.1089/cpb.2008.0325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wise M. Integrating a narrative medicine telephone interview with online life review resources for cancer patients. Journal of the Society for Integrative Oncology 2010;8:193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. WeChat user number statistics. Tech Business analysis. http://seonew.cn/yxzj/2016/0407/707.html (Available 7 Apr 2016).

- 34. Zhang MF. Application of obstetric practice based on WeChat among nursing students. Journal of Nurses Training 2015;30:624–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang SF, Ying JJ, Liiu ZM. Application of continuing care based on WeChat in guidance of PICC maintenance among cancer patients after discharge. Journal of Nursing Administration 2015;15:215–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moher D, Spirit CA. Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) Guidelines for Reporting Health Research: A User’s Manual: John Wiley & Sons, 2014:56–67. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:726–32. 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chow SC, Shao J, Wang H. Sample size calculation in clinical research. New York: Marcel Dekker, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen SH. Effectiveness of lire review in increasing self-transcendence, hope, and spiritual well-being of patients with cancer: Department of Nursing Fooying University, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Erikson E. Childhood and society. 1st edn New York: Norton, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reed PG. Self-transcendence and mental health in oldest-old adults. Nurs Res 1991;40:5–11. 10.1097/00006199-199101000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Teixeira ME. Self-transcendence: a concept analysis for nursing praxis. Holist Nurs Pract 2008;22:25–31. 10.1097/01.HNP.0000306325.49332.ed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Xiao H, Kwong E, Pang S, et al. Construction of life review intervention for patients with advanced cancer. Chinese Journal of Nursing 2010;45:631–3. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen Y, Xiao H, Lin X. Developing a mind map-based life review program to improve psychological well-being of cancer patients: a feasibility study. Psychooncology 2018;27:339–42. 10.1002/pon.4406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 1971;12:371–9. 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hu L, Cao J, Zhu ZH. Analysis of mental agility and anxiety and depression in cancer patients. Journal of Chinese behavioral medicine and brain science 2015;24:517–20. [Google Scholar]

- 47. ZUNG WW. A SELF-RATING DEPRESSION SCALE. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1965;12:63–70. 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wei H. Psychological Health Diathesis Assessment System: The Establishment of Chinese Adult Emotionality Scale. Studies of Psychology and Behavior 2012;10:262–8. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang J, Sun JP, Zhang L, et al. The reliability and validity of self-transcendence scale in Chinese elderly population. Chinese Journal of Gerontology 2014;34:1910–1. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, et al. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J Couns Psychol 2006;53:80–93. 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang MC, Dai XY. Chinese Meaning in Life Questionnaire Revised in College Students and Its Reliability and Validity Test. Chinese Journal of clinical psychology 2008;16:459–61. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Herth K. Development and refinement of an instrument to measure hope. Sch Inq Nurs Pract 1991;5:39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Xb L, Wu L. Correlation survey of social support and hope of patients with lung cancer. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation 2005;8:7894–5. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Karnofsky DA, Abelmann WH, Craver LF, et al. The use of the nitrogen mustards in the palliative treatment of carcinoma. Cancer 1948;1:634–56. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979;47:343–52. 10.1037/0022-006X.47.2.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang L, Shen Y, Liang Z, et al. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Beck suicide ideation scale in patients with depression. Chinese Journal of Health Psychology 2012;20:159–60. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Haight BK. Reminiscing: the state of the art as a basis for practice. Int J Aging Hum Dev 1991;33:1–32. 10.2190/F8YP-D4X5-MV9M-CGMH [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Taboume CE, McDonald JM. Life review: Memories and melodies of old age. Parks & Recreation 1986. 24 27. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Haight BK, Haight BS. The Handbook of Structured Life Review. 1st edn: Health Professions Press U.S, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wang W, Jia XM. Intervention skills of online counseling. Journal of Chinese Mental Health 2012;26:864–70. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.