Abstract

The scarcity of feed resources with the continuously increasing cost of usual animal feeds urgently demands searching some alternate feeds for ruminants. In this study, Barberi male kids were divided into 4 groups of 5 kids (body weight 17.5 ± 1.8 kg) in each group, and ad libitum fed lentil straw (Lens culinaris; LS), LS based total mixed ration (LSTMR), urea ammoniated LS (ALS) or ALS based total mixed ration (ALSTMR) for a period of 28 days. Results showed LS was a superior feed (CP, 9.2%) for kids, but having quite high crude fibre (CF; 39.6%) and Ca:P ratio (10:1). Urea ammoniation of LS was helpful for increasing the digestible crude protein (DCP) (P < 0.01), nitrogen-free extract (NFE) and total digestible nutrients (TDN) with reduction of CF content. Urea mmoniation also improved the digestibility of neutral and acid detergent fibre (P < 0.01), but its effect on CP digestibility was negative (P < 0.05). Dry matter (DM), DCP and TDN intakes (per kg W0.75) were also improved (P < 0.01) in the kids fed ALS. Negative growth rate and nitrogen (N) balance (−33.8 and −1.4 g/day, respectively) in kids fed LS became positive (46.9 and 2.0 g/day, respectively) when ALS was used in the diets of kids. Feeding of ALS also increased (P < 0.01) the total N and ammonia N content of strained rumen liquor (SRL). Use of straw (LS or ALS) in TMR increased the digestibility of DM, organic matter and NFE (P < 0.01), intake of energy, as well as total volatile fatty acids concentration (P < 0.01) in the SRL. The present study suggested that optimum performance of kids may be achieved using either ALS alone or TMR with LS or ALS.

Keywords: Kids, Lentil straw, Nutrient utilization, Rumen fermentation, Total mixed ration, Urea ammoniation

1. Introduction

In the present era of the fast-growing human population, ruminant species occupy an important niche in modern agriculture because of their unique ability to digest certain feedstuffs, especially roughages, efficiently. In future, the direct demands for grain by human beings will make efficient utilization of roughages increasingly important (Visser, 2005). Simultaneously, increasing demands for high-quality animal protein in the world show greater potential for development of sheep and goat production, whereas decreasing community grazing land and increasing cropping intensity have created a serious gap between demand and supply of concentrate feeds and fodder, which has made livestock feeding increasingly dependent on alternate feed resources. Effective utilization of available feed resources is the key to economical livestock rearing (Lardy et al., 2015, Beigh et al., 2017).

Lentil ranks the 5th among most important pulses in the world and is extremely important for diets of Near East and Indian (FAO, 2012). Its by-product lentil straw (LS, an unconventional feed) is a nutrient-dense feed stuff, due to its leguminous nature, LS has better ruminal degradation with whole tract digestibility as compared to routinely used cereal straws (Lopez et al., 2005, Singh et al., 2011, Lardy et al., 2015) and successful use of LS in the ration of large ruminants and sheep (Abbeddou et al., 2011a, Lardy et al., 2015) without having any side effect on the quality of animal products (Abbeddou et al., 2011b), which suggests its high acceptability and digestibility in livestock ration.

The limitation of using these by-products is the presence of the high amount of lignified fibre, which hinders the coupling of cellulose and hemicellulose with a nitrogen (N) source for optimum microbial protein synthesis. This unfavourable bonding of lignin with available carbohydrate may be broken down with the help of physical or chemical treatment of the straw. Among different available methods, urea ammoniation (Rath et al., 2001, Oji et al., 2007), supplementation of critical nutrients (Abebe et al., 2004, Pi et al., 2005) or their combination (Abebe et al., 2004, Pi et al., 2005) may be the most promising, practical and user friendly methods to support the use of lignified forages in ruminant's ration. Complete feed system or total mixed ration (TMR) is one of the latest developments to exploit the potential of animal feed resources in the best possible way. The complete feed system is helpful to prevent selective feeding and thus to meet the specific nutrient requirements (Beigh et al., 2017).

The scanty literature on the use of LS in goats inspired us to evaluate its feeding value for kids in different forms/combinations.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Experimental animals

With prior approval of college level Animal Ethical Committee, healthy growing Barberi male kids with a mean body weight of 17.5 ± 1.8 kg were divided into 4 groups of 5 each according to their body weights using completely randomized design. They were dewormed before the start of the experimental feeding and were housed in well-ventilated concrete floored rooms with individual watering and feeding facility.

2.2. Method of urea ammoniation

Urea ammoniated LS (ALS) was prepared by treating LS with 4% urea at 50% moisture level and incubated for 4 weeks (Walli et al., 1995) under airtight condition by covering tightly with polythene sheet (Sundstol et al., 1978). Before feeding, straw was exposed in air to remove the excess and evaporable ammonia.

2.3. Preparation of total mixed rations

Total mixed ration was prepared to utilize coarsely ground maize grains, which was mixed with either LS or ALS just before feeding, using 50% water level, for individual animals according to their requirements (Ranjhan, 1993).

2.4. Experimental feeding

An adaptation period of 15 days was provided to let animals get accustomed to the experimental feeds, during which gradual shifting to their respective feeds was carried out. Feeding diets included LS, LS based total mixed ration (LSTMR), ALS, ALS based total mixed ration (ALSTMR).

Experimental feeding was continued for a period of 28 days, including a 6-day metabolism trial at the end of the experiment. Goats were given amount of their respective rations in 2 identical meals at 09:00 and 17:00. Kids were weighed before the start and at the termination of the experimental feeding in the morning, before watering and feeding.

2.5. Metabolism trial

During the metabolism trial, a quantitative collection of faeces and urine as per standard procedure (Sastry et al., 1999) was carried out. Two days adaptation period was given to the animals in the metabolism cages prior to actual sampling. Feeds offered and residue left were weighed daily during the metabolism trial. Water was available to all animals ad libitum twice daily. Representative samples of feeds offered, residue left, urine and faeces voided during the metabolism trial were collected daily for 6 d, and polled for further chemical analysis.

2.6. Rumen liquor collection

Rumen liquor samples were collected at the termination of the experiment before watering and feeding for 3 consecutive days using stomach tube, strained through 4 layers of cheesecloth and individually pooled strained rumen liquor (SRL), and then preserved (−20 °C) for further analysis.

2.7. Analytical procedure

Straw offered, residue left and faeces voided were analysed for proximate constituents (AOAC, 2000), neutral detergent fibre (NDF) and acid detergent fibre (ADF) (Goering and Van Soest, 1970) and calcium (Ca) and phosphorus (P) contents (Talpatra et al., 1940). The SRL was analysed for pH, total N, total volatile fatty acids (TVFA) (Barnett and Reid, 1957) and ammonia N (Conway, 1962).

2.8. Data analysis

Data were analysed by the method described by Snedecor and Cochran (1989). Analysis of Variance was used to compare treatments, and Duncan's multiple range test was employed on the data where a significant difference (P < 0.05) was observed.

3. Results

3.1. Chemical composition of experimental feeds

Chemical composition of the experimental feeds (Table 1) indicated that nutritive value of LS (9.2% CP, 39.6% CF and 1.1% Ca) was further improved due to ammoniation, as well as fortification with energy source in the form of TMR (NFE: 51.3% to 53%).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of experimental feeds with nutrient digestibility.

| Item | LS | LSTMR | ALS | ALSTMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical composition, % on dry matter basis | ||||

| Organic matter | 91.6 | 93.5 | 91.6 | 93.4 |

| Crude protein | 9.2 | 9.2 | 14.1 | 12.8 |

| Ether extract | 3.0 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 3.7 |

| Crude fibre | 39.6 | 29.3 | 31.5 | 23.9 |

| Nitrogen free extract | 39.9 | 51.3 | 43.0 | 53.0 |

| Ca | 1.1 | 0.82 | 1.1 | 0.83 |

| P | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.18 |

| Digestibility coefficients, % | ||||

| Dry matter** | 55.7 ± 2.1a | 65.5 ± 2.6b | 56.7 ± 0.64a | 67.6 ± 2.2b |

| Organic matter** | 57.5 ± 2.1a | 67.4 ± 2.5b | 58.7 ± 0.73a | 68.1 ± 2.0b |

| Crude protein* | 59.6 ± 3.5b | 64.2 ± 2.7b | 51.4 ± 1.4a | 58.0 ± 3.1ab |

| Ether extract | 72.8 ± 2.3 | 72.5 ± 3.6 | 71.7 ± 3.9 | 72.5 ± 8.8 |

| Nitrogen free extract** | 61.3 ± 2.2a | 76.7 ± 1.9b | 67.9 ± 0.64a | 80.8 ± 1.8b |

| Neutral detergent fibre** | 37.0 ± 3.0a | 46.1 ± 3.7a | 54.6 ± 1.3b | 61.5 ± 2.7b |

| Acid detergent fibre** | 33.6 ± 2.9a | 34.2 ± 5.4a | 51.0 ± 1.0b | 55.5 ± 2.6b |

LS = lentil straw; LSTMR = LS based total mixed ration; ALS = ammoniated LS; ALSTMR = ALS based total mixed ration.

a,b Within a row, means without a common uppercase superscript differ. *: P < 0.05 or **: P < 0.01.

3.2. Nutrient digestibility

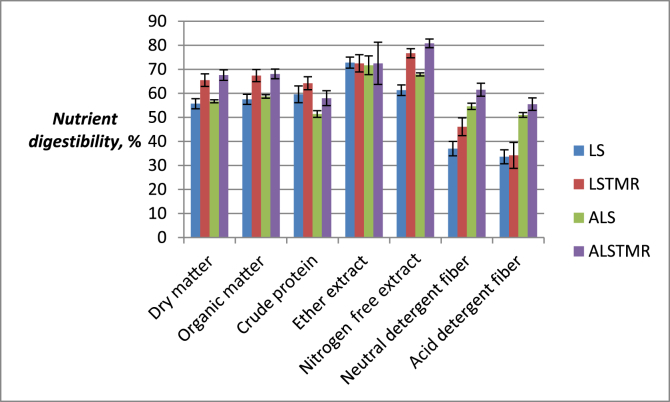

The TMR groups showed higher (P < 0.01) digestibility of DM, OM, and NFE as compared to their relative counterparts with untreated or ammoniated straws alone (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Digestibility of ether extract remained comparable (P < 0.05) among groups and within a narrow range (71.7% to 72.8%). Crude protein digestibility was lower (P < 0.05) in ALS group compared to either LS alone or LSTMR group. Digestibility of NDF and ADF in ALS groups remained higher (P < 0.01) compared to their untreated counterparts.

Fig. 1.

Nutrient digestibility in kids fed LS based rations. LS = lentil straw; LSTMR = LS based total mixed ration; ALS = ammoniated LS; ALSTMR = ALS based total mixed ration.

3.3. Dry matter, energy, and protein intake

Intakes of DM, digestible crude protein (DCP) and total digestible nutrients (TDN) are presented in Table 2. Dry matter intake (g/W0.75) was superior (P < 0.01) among all 3 treatment groups as compared to LS alone, with the highest intake in ALSTMR group.

Table 2.

Nutrient intake and nutritive values of lentil straw based rations fed to kids.

| Item | LS | LSTMR | ALS | ALSTMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrients intake, g/kg W0.75 | ||||

| Dry matter | 56.6 ± 4.7a | 80.3 ± 3.1b | 79.5 ± 4.2b | 90.6 ± 1.7b |

| Digestible crude protein | 3.1 ± 0.25a | 4.8 ± 0.18b | 5.8 ± 0.30c | 6.8 ± 0.12d |

| Total digestible nutrients | 31.4 ± 2.6a | 53.7 ± 2.1bc | 45.1 ± 2.4b | 62.1 ± 1.2c |

| Nutritive value, % | ||||

| Digestible crude protein | 5.5 ± 0.27a | 5.9 ± 0.25a | 7.3 ± 0.2b | 7.5 ± 0.4b |

| Total digestible nutrients | 55.5 ± 2.0a | 66.9 ± 2.4b | 56.8 ± 0.61a | 68.5 ± 1.8b |

LS = lentil straw; LSTMR = LS based total mixed ration; ALS = ammoniated LS; ALSTMR = ALS based total mixed ration.

a,b,c,d Within a row, means without a common uppercase superscript differ (P < 0.01).

Intake of DCP alone showed a similar pattern (P < 0.01) with the highest intake in ALSTMR group. Total digestible nutrient intake (g/W0.75) was higher in ALS group than that in its untreated counterpart (LS). Likewise, TMR groups showed higher (P < 0.01) TDN intakes as compared to their counterpart with LS or ALS.

3.4. Nutritive value of experimental diets

Nutritive value of different experimental diets in kids is presented in Table 2. Digestible crude protein value of diets remained higher (P < 0.01) in ALS group as compared to LS groups although LSTMR group had higher (5.9%) DCP value compared to LS group (5.5%), but was statistically comparable (P > 0.01). Energy (TDN) value of TMR diets remained higher (P < 0.01) as compared to their counterparts with LS or ALS.

3.5. Nutrient balance, body weight change and rumen fermentation pattern

The balance of different nutrients (g/day) like N, Ca, and P is presented in Table 3. Nitrogen balance remained comparable (P < 0.05) among different groups with exception of LS group, where it was negative (−1.4 g/day).

Table 3.

Nutrient balance, body weight change and rumen fermentation parameters in kids fed LS based rations.

| Item | LS | LSTMR | ALS | ALSTMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient balance, g/day | ||||

| Nitrogen | −1.4 ± 0.23 | 1.5 ± 0.34 | 2.0 ± 0.12 | 2.3 ± 0.25 |

| Calcium | 0.96 ± 0.16 | 1.4 ± 0.35 | 0.92 ± 0.43 | 1.9 ± 0.24 |

| Phosphorus** | 0.30 ± 0.05a | 0.79 ± 0.11b | 0.37 ± 0.05ab | 0.58 ± 0.05b |

| Body weight change | ||||

| Initial body weight, kg | 17.6 ± 2.1 | 17.0 ± 1.45 | 18.4 ± 1.4 | 17.0 ± 2.1 |

| Final body weight, kg | 16.7 ± 2.1 | 18.2 ± 1.4 | 19.7 ± 1.4 | 18.6 ± 2.1 |

| Growth rate**, g/day | −33.8 ± 6.0a | 40.0 ± 2.3b | 46.9 ± 4.8bc | 58.6 ± 2.4c |

| Rumen fermentation parameters, per 100 mL SRL | ||||

| pH* | 7.3 ± 0.25b | 6.9 ± 0.3ab | 7.2 ± 0.49b | 6.5 ± 0.37a |

| TVFA**, m.eq | 7.3 ± 0.97a | 9.5 ± 0.69b | 8.0 ± 1.1ab | 9.8 ± 1.6b |

| Total nitrogen**, mg | 68.8 ± 6.6a | 71.5 ± 4.6a | 92.8 ± 4.2b | 88.9 ± 1.4b |

| Ammonical nitrogen**, mg | 6.7 ± 0.39a | 7.8 ± 1.1ab | 10.1 ± 1.5c | 9.5 ± 0.78bc |

LS = lentil straw; LSTMR = LS based total mixed ration; ALS = ammoniated LS; ALSTMR = ALS based total mixed ration; SRL = strained rumen liquor; TVFA = total volatile fatty acids.

a,b,c Within a row, means without a common uppercase superscript differ. *: P < 0.05 or **: P < 0.01.

Calcium balance was though not statistically comparable (P > 0.05) among groups, but the lowest in ALS group and the highest in ALSTMR group, but P balance was higher (P < 0.01) in TMR groups as compared to their LS groups. Ammoniation of LS also improved P balance (0.37 vs. 0.30 g) as compared to LS group.

Body weight changes also showed similar trend (Table 3) to that of N balance and thus growth rate was negative in LS group (−33.8 g/day), ALSTMR group showed the highest (58.6 g/day) growth rate among different groups with significantly higher (P < 0.01) values as compared to LSTMR group.

Rumen fermentation parameters are represented in Table 3. Rumen liquor pH was lower in TMR group (P < 0.05) as compared to LS alone with the lowest pH in ALSTMR group (6.5). Similar to pH, total volatile fatty acids (TVFA) concentration also remained higher (P < 0.01) in TMR group with the lowest value in LS group (7.3 m. eq.). Rumen total N was higher (P < 0.01) in ALSTMR group as compared to LSTMR.

Rumen ammonical N also remained higher (P < 0.01) in ALS groups with the highest value in ALS group (10.1 mg/100 mL SRL) and the lowest in LS group (6.7 mg/100 mL SRL).

4. Discussion

4.1. Chemical composition of experimental feeds

Chemical composition indicated that LS was nutritionally superior to wheat straw in its protein, Ca and P contents, similar findings were also reported by Lardy et al. (2015). Haile et al. (2017) also interpreted in their studies that LS was superior in its CP and metabolisable energy content with lower NDF and ADF contents than the cereal crop residues.

Chemical composition of the LS highlighted imbalance of Ca:P ratio (10:1) and this imbalance may be a reason for cases of hypo-phosphatemia commonly observed in the areas where legume (lentil/g) straw fed alone as a basal diet for dairy animals (Jain et al., 2012), which needs a P supplementation and thus the ratio was quite narrow (4:1) in TMR groups.

Urea ammoniated LS was nutritionally superior to its untreated counterpart. Ammoniation increased the CP content due to the addition of non-protein nitrogen source. Increased soluble (NFE) and decreased insoluble carbohydrate (CF) fraction indicated solubilization of crude fibre. A similar type of observations was made by Arellano et al. (1993) and Walli et al. (1995). Use of TMR in other 2 groups showed increased NFE, but decreased fibre content and it was mainly due to the addition of maize grains in TMR being rich in soluble carbohydrates.

4.2. Nutrient digestibility

The digestibility of LS for most of its constituents was more than 50% (55% to 72%) except for fibre fraction. Fuller (2004) in his book also emphasized that LS with higher digestibility than most of other straw was used in feeding of ruminants. Likewise, Haile et al. (2017) also reported that LS has higher digestibility in vitro when compared with the cereal crop residues.

Urea ammoniation reduced CP digestibility of the straw. This may be attributed to either tightly bound nitrogen in the straw by urea ammoniation (Sundstol and Coxworth, 1984, Hvelplund, 1989) or increased N flow to the intestine owing to greater microbial protein synthesis in the rumen (Djajanegara and Doyle, 1989). This corroborated well with the findings of Cloete and Kritzinger (1984) and Gupta et al. (2002). Contrary, Borah et al. (1988) found that increased CP digestibility was found in animals fed ammoniated straw. It may be interpreted from the study that full ammonia cannot be utilized by ruminants when ammoniated straw alone was used. The reason behind inefficient N utilization might be the higher (10.1 mg/100 mL) level of rumen ammonia N as compared to its optimum range (5 to 8 mg/100 mL SRL; Maynard et al., 1979). Lacking available carbohydrate source (which may provide carbon chain for ruminal amino acid synthesis) may be a cause of impaired N utilization by rumen microbes and thus when the available carbohydrate source was incorporated in ALSTMR group, both N utilization as well as digestibility of CP were better.

Digestibility of DM, OM and NFE remained better in TMR groups which may be due to the use of highly digestible maize grains (Ranjhan, 1993) in their rations, but ammoniation alone was unable to affect their digestibility.

Improved fibre digestibility (NDF and ADF) attributed to ester linkages breaking role of ammonia. Improvement in the digestibility of fibre fractions has also been reported by Oji et al. (2007), whereas the use of TMR has no significant effect on fibre fractions.

4.3. Dry matter, energy and protein intake

Increased DMI in kids was reported when LS was either ammoniated or incorporated in TMR. The reason in the ammoniated group (ALS) might be the reduction in coarseness of straw by the alkaline nature of ammonia. Similar findings were also observed by Oji et al. (2007). Improved DMI in LSTMR group indicated increased palatability of ration due to the incorporation of the maize grain, but the insignificant effect of ALSTMR over ALS interprets higher palatability of ALS itself, which nullify the effect of maize incorporation. Similar findings were also reported by Abebe et al. (2004), and Beigh et al. (2017) also suggested that the complete feed with the use of fibrous crop residue is a noble way to increase the voluntary feed intake and animal's production performance.

Improvement reported in DCP intake in ALS group was attributed to improved DMI as well as higher CP content of the ALS. Enhanced DCP intake in TMR groups and energy intake in all treatment groups justified by increased DMI in their respective groups. Similar to the present findings, Puri and Gupta (2001) also reported improved DCP and TDN intake when ammoniated paddy straw diet was used, similarly Dutta et al. (2004) also found improved N intake in bucks fed ALS.

4.4. Nutritive value of experimental diets

Urea ammoniation increased the DCP value of the treated straw, whereas the effect on energy value was meagre. Incorporation of maize grains lead to a higher energy value in TMR. The nutritive value as well as higher DMI in ALS and TMR groups indicated their nutritional adequacy for feeding as a sole diet for growing goats, but the LS alone was not sufficient to fulfil the growth requirement of kids, due to their lower DCP as well as TDN values, which remained low against suggested (Ranjhan, 1993) for rowing kids.

4.5. Nutrient balance, body weight change and rumen fermentation pattern

Kids fed either ALS or TMR had a positive N balance as compared to those fed LS (having 5.5% DCP), indicated that ALS alone was nutritionally adequate and produced a good growth response in growing kids. Similar observations were made by Puri and Gupta (2001).

Shiriyan et al. (2011) in their studies reported improved growth performance of lambs when wheat straw was replaced with urea ammoniated wheat straw in TMR. Use of TMR also showed better growth response overfeeding of straw alone. Similar to present findings, Nissanks et al. (2010) also reported improved growth performance of Friesian heifers when TMR was compared to conventional feeding.

The rumen fermentation pattern indicated that addition of maize in the form of TMR had reduced the pH values of rumen liquor, but remained unaffected by ammoniation of the straw. Positive N balance was also reflected by an improvement in the rumen total and ammonia nitrogen levels in the ammoniated groups. Similar observations have been made by Abebe et al. (2004). Insignificant improvement in TVFA concentration due to feeding ALS diet indicated a slight improvement in the availability of total carbohydrates due to urea ammoniation, but in TMR group improvement was higher as the starch content of maize was capable to produce huge amounts of volatile fatty acids and thus the pH was significantly reduced. Similar finding was also reported by Smiko et al. (2009). Beigh et al. (2017) also concluded that use of complete feed system in ruminant animals enables continuous free choice availability of uniform feed mixture, resulting in more uniform load on the rumen and less fluctuation in the release of ammonia which supports more efficient utilization of ruminal non-protein nitrogen. Feeding complete diet stabilizes ruminal fermentation, thereby improves nutrient utilization. This feeding system allows expanded use of agro-industrial by-products, crop residues and nonconventional feeds in the ruminant ration for maximizing production and minimizing feeding cost, thus being increasingly appreciated.

5. Conclusions

On the basis of the present study, it may be concluded that untreated LS fed alone provides a sub-maintenance diet for kids, due to low nutritive value and DMI and also having inappropriate Ca:P ratio. It can, however, be ammoniated with urea or fed in a TMR for getting optimum performance in kids rearing.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Abbeddou S., Rihawi S., Hess H.D., Iniguez L., Mayer A.C., Kreuzer M. Nutritional composition of lentil straw, vetch hay, olive leaves, and saltbush leaves and their digestibility as measured in fat-tailed sheep. Small Rumin Res. 2011;96:126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Abbeddou S., Rischkowsky B., Hilali Mel-D., Hess H.D., Kreuzer M. Influence of feeding Mediterranean food industry by-products and forages to Awassi sheep on physicochemical properties of milk, yoghurt and cheese. J Dairy Res. 2011;78:426–435. doi: 10.1017/S0022029911000665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abebe G., Merkel R.C., Animut G., Sahlu T., Goetsch A.L. Effects of ammoniation of wheat straw and supplementation with soybean meal or broiler litter on feed intake and digestion in yearling Spanish goat weathers. Small Rumin Res. 2004;51:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . 17th ed. Association of Official Analytical Chemists; Arlington (VA): 2000. Official methods of analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano L., Carranco M., Perez-Gil F., Alonso M. Effect of urea treatment on the digestibility and nitrogen content of Amaranthus hypochondriacus straw. Small Rumin Res. 1993;11:239–245. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett A.J.G., Reid R.L. Studies on production of volatile fatty acids from grass by rumen liquor in artificial rumen, TVFA production from fresh grasses. J Agric Sci. 1957;48:315–321. [Google Scholar]

- Beigh Y.A., Ganai A.M., Ahmad H.A. Prospects of complete feed system in ruminant feeding: a review. Vet World. 2017 doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2017.424-437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borah H.P., Singh U.B., Mehra U.R. Ammoniated paddy straw as a maintenance ration for adult cattle. Indian J Anim Nutr. 1988;5:105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Cloete S.W.P., Kritzinger N.M. Urea ammoniation compared to urea supplementation as a method for improving the nutritive value of wheat straw. S Afr J Anim Sci. 1984;14:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Conway E.J. 5th ed. Crossby Lookwood and Sons Ltd; London, England: 1962. Micro diffusion analysis and volumetric errors. [Google Scholar]

- Djajanegara A., Doyle P.T. Urea supplementation compared with pre-treatment 1. The effects on intake, digestion and live weight changes by sheep fed on rice straw. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 1989;27:17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta N., Sharma K., Naulia U. Nutritional evaluation of lentil (lens culinaris) straw and urea treated wheat straw in goats and lactating buffaloes. Asian Aust J Anim Sci. 2004;17:1529–1534. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations . 2012. FAOSTAT. Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Roma, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller M.F. CABI publishing; Wallingford, UK: 2004. The encylopedia of farm animal nutrition. [Google Scholar]

- Goering H.K., Van Soest P.J. ARS USDA; Washington (DC): 1970. Forage fibre analysis (apparatus, reagents, procedure and some applications.) Agri. Hand book. No. 379. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P.K., Sharma S.D., Agrawal I.S. Optimization of urea treatment of wheat straw and effect of feeding urea treated paddy straw on intake and digestibility of nutrients. Indian J Anim Nutr. 2002;19:221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Haile E., Gicheha M., Njonge F.K., Asgedom G. Determining nutritive value of cereal crop residues and lentil (lens esculanta) straw for ruminants. Open J Anim Sci. 2017;7(1):19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hvelplund T. Elsevier Applied Science; London, England: 1989. Evaluation of straws in ruminant feeding. Protein evaluation of treated straws. [Google Scholar]

- Jain R.K., Saksule C.M., Dhakad R.K. Nutritional status and probable cause of haemoglobinuria in advanced pregnant buffaloes of Indore district of Madhya Pradesh. Buffalo Bull. 2012;31:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lardy G., Anderson V., Dahlen C. North Dakota State University; Fargo North Dakota 58108, USA: 2015. Alternative feeds for ruminants. AS-1182 (Revised) NDSU extension services. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez S., Davies D.R., Giraldez F.J., Dhanoa M.S., Dijkstra J., France J. Assessment of nutritive value of cereal and legume straws based on chemical composition and in vitro digestibility. J Sci Food Agric. 2005;85:1550–1557. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard L.A., Loosili J.K., Hintz H.F., Warner R.G. 7th ed. Tata McGraw Hill Publishing Company Limited; New Delhi, India: 1979. Animal nutrition. [Google Scholar]

- Nissanka N.P.C., Bandara R.M.A.S., Disnaka K.G.J.S. A comparative study on feeding of total mixed ration vs conventional feeding on weight gain in weaned Friesian heifers under tropical environment. J Agric Sci. 2010;5:42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Oji U.I., Etim H.E., Okoye F.C. Effects of urea and aqueous ammonia treatment on the composition and nutritive value of maize residues. Small Rumin Res. 2007;69:232–236. [Google Scholar]

- Pi Z.K., Klu Y.M., Liu J.X. Effect of pre-treatment and pelletization on nutritive value of rice straw based total mixed ration and growth performance and meat quality on growing boar goats fed on TMR. Small Rumin Res. 2005;56:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Puri J.P., Gupta B.N. Effect of feeding rice straw treated with two levels of urea and moisture on growth and nutrient utilization in crossbred calves. Indian J Anim Nutr. 2001;18:54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjhan S.K. 4th ed. Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd; New Delhi, India: 1993. Aniaml nutrition and feeding practices. [Google Scholar]

- Rath S.S., Verma A.K., Singh P., Dass R.S., Mehra U.R. Performance of growing lambs fed urea ammoniated and urea supplemented based diets. Asian Aust J Anim Sci. 2001;14:1078–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Sastry V.R.B., Kamra D.N., Pathak N.N. Indian Veterinary Research Institute; Izatnagar, UP, India: 1999. Laboratory manual of animal nutrition. [Google Scholar]

- Shiriyan S., Zamani F., Vatankhah M., Rahimi E. Effect of urea treated wheat straw in a pelleted total mixed ration on performance and carcass characteristics of Lori-Bakhtiari Ram lambs. Global Vet. 2011;7:456–459. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Kushwaha B.P., Nag S.K., Mishra A.K., Bhattacharya S., Gupta P.K., Singh A. In vitro methane emission from Indian dry roughages in relation to chemical composition. Curr Sci. 2011;101:57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Smiko M., Ceresnakova Z., Biro D., Juracek M., Galik B. The effect of wheat and maize meal on rumen fermentation and apparent nutrient digestibility in cattle. Slovak J Anim Sci. 2009;42:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor G.W., Cochran W.G. 7th ed. Oxford and IBH Publishing Co.; Calcutta, India: 1989. Statistical methods. [Google Scholar]

- Sundstol F., Coxworth E.M. Elsevier; Amsterdam (NY): 1984. Straw and other fibrous by-products as feed. [Google Scholar]

- Sundstol F., Coxworth E., Mowat D.N. Improving the nutritive quality of straw and other low quality roughages by treatment with ammonia. World Anim Rev. 1978;26:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Talpatra S.K., Ray S.C., Sen K.C. Analysis of mineral constituents of biological materials. Indian J Vet Sci Anim Husb. 1940;10:243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Visser D.P. 2005. Ruminant digestion.http://www.kzndard.gov.za/images/Documents/RESOURCE_CENTRE/GUIDELINE_DOCUMENTS/PRODUCTION_GUIDELINS/Dairying_in_KwaZulu-Natal/Ruminant%20Digestion.pdf [Accessed 20 February 2018] [Google Scholar]

- Walli T.K., Rao A.S., Singh M., Rangnakar D.V., Pradhan P.K., Singh R.B., Ibrahim M.N.M. Indian Council of Agricultural Research; New Delhi, India: 1995. Hand book of straw feeding systems. [Google Scholar]