Abstract

In the United States, there is widespread concern that state laws restricting rights for noncitizens may have spillover effects for Latino children in immigrant families. Studies into the laws’ effects on health care access have inconsistent findings, demonstrating gaps in our understanding of who is most affected, under what circumstances. Using comparative interrupted time series methods and a nationally-representative sample of US citizen, Latino children with noncitizen parents from the National Health Interview Survey (2005–2014, n=18,118), this study finds that living in counties with higher co-ethnic density placed children at greater risk of losing Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program coverage when their states passed restrictive state omnibus immigrant laws. This study is the first to demonstrate the importance of examining how the health impacts of immigration-related policies vary across local communities.

Keywords: United States, omnibus immigration-related laws, Latino children, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program, co-ethnic density

1. Introduction

Since the mid-1990s, a surge in punitive federal, state, and local immigration policies has criminalized immigrants, militarized borders, and intensified immigration enforcement throughout the United States (Hagan et al., 2015; Pedraza and Zhu, 2013). From 1996–2014, deportations from the US increased more than 800% (Hagan et al., 2015). Federal and state laws limited access to public benefits such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) for both documented and undocumented immigrants (Pedraza and Zhu, 2013); state laws restricted employment, driver’s licenses, and education for undocumented immigrants (Pedraza and Zhu, 2013; Philbin et al., 2017). Although immigration-related laws do not officially target Latin American immigrants, the accompanying political messaging, media attention, and enforcement focuses predominantly on Latino noncitizens (Hagan et al., 2015; Pedraza and Zhu, 2013). The laws’ target groups are typically undocumented immigrants. However, there are potential spillover effects: Latino US citizens and legal residents, whose rights are not directly restricted by the laws, may be impacted indirectly because they live in households or communities with undocumented members (Torres and Young, 2016). In particular, there may be negative effects for the 4.5 million US-born children of Latino immigrants (Urban Institute, 2018), with the potential to widen and entrench health, educational, and income disparities for Latino children across the life-course (Pedraza and Zhu, 2013; Torres and Young, 2016).

1.1. Literature review

Only the federal government can regulate who enters or stays in the US. State and local governments influence immigration indirectly through policies that make immigrants’ lives harder, to encourage them to leave the state (or pass laws to make immigrants’ lives easier and promote immigrant integration). I refer to these state laws as immigrant laws, to distinguish them from federal immigration laws that regulate who is legally present in the US (García, 2013).

The most restrictive state immigrant laws, called omnibus immigrant laws, combine three or more immigration-related measures in a single bill (Laglaron et al., 2008). Colorado, Indiana, Nebraska, and Oklahoma each passed one omnibus law between 2005–2014; Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Missouri, South Carolina, and Utah passed two or more (Appendix Table 1) (Allen & McNeely, 2017). In all 10 states, omnibus laws increased local enforcement of federal immigration law, restricted undocumented immigrants’ access to employment, and expanded restrictions on undocumented immigrants’ access to public benefits. At least 21 additional states considered, but did not pass, omnibus bills (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2018). Restrictive state immigrant laws pass partially in response to growth in the state’s foreign-born population (Monogan, 2013; Ybarra et al., 2016). With the exception of Arizona and Colorado, the states that passed omnibus laws were “new destination” states with relatively small, but rapidly increasing, Latino immigrant populations (Lichter and Johnson, 2009).

States faced many difficulties implementing omnibus laws, leading to slow and often incomplete implementation (Pham, 2008). However, service providers, community leaders, and Latino parents reported impacts on immigrant communities immediately after passage, with spillover effects for citizen children of immigrants. They reported intense fear among Latino families; anti-immigrant discrimination from government employees, health care providers, and the public; and declines in Latino children’s health care utilization and enrollment in schools and public benefits (Hardy et al., 2012; Koralek et al., 2009; Toomey et al., 2014; White et al., 2014b). In addition, the initial period after passage was characterized by fear, misinformation, and confusion among both parents and service providers, including confusion about whether citizen children with immigrant parents remained eligible for programs like Medicaid/CHIP (Hardy et al., 2012; Koralek et al., 2009; Toomey et al., 2014). Loss of public benefits has potential long-term consequences, as Medicaid/CHIP have health and economic benefits through adulthood (Howell and Kenney, 2012) and buffer against the developmental risks associated with parental undocumented status (Brabeck et al., 2015).

However, quantitative studies examining the laws’ effects on Latino children produced conflicting findings, demonstrating gaps in our understanding of who is most affected, under what circumstances, and for which outcomes. Some studies found decreased health care utilization (Beniflah et al., 2013; Toomey et al., 2014) and enrollment in public benefits (Toomey et al., 2014) among Latino children. Others found no decrease in health department visits (Koralek et al., 2009; White et al., 2014a) or enrollment in public benefits (Allen & McNeely, 2017; Koralek et al., 2009).

One possible explanation for the mixed findings is that omnibus laws may have differential effects based on local community characteristics (Philbin et al., 2017). These may arise because of differences in policy implementation (Hupe, 2014; Koralek et al., 2009) and/or differences among affected persons in the ability to navigate policy changes (Philbin et al., 2017; Wong and García, 2016). States are large and heterogeneous places. States that pass omnibus laws contain wide diversity in public support for these laws at the local level (Koralek et al., 2009; Pham, 2008). They also vary in the presence of resources for migrant populations (Bécares et al., 2012; Joassart-Marcelli, 2013; Menjívar, 1997). In some states, Medicaid/CHIP programs are highly decentralized and administered at the county level (Perreira et al., 2012); policies and procedures in county offices could exacerbate (or limit) the laws’ impacts.

Indeed, state and local context influenced undocumented immigrants’ decisions to apply for the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act legalization program (Hagan and Gonzales Baker, 1993) and the 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (Wong and García, 2016). However, to date, research evaluating immigration-related policy is largely silent on the relevance of this local variation for health outcomes.

1.2. Research question and hypotheses

This study examines the potential moderating role of county co-ethnic density, a contextual measure widely used in public health research as a protective feature of place (Bécares et al., 2012). Living near other people who share one’s language, national origin, or ethnicity is believed to promote immigrants’ health and economic integration (Bécares et al., 2012; Portes and Rumbaut, 2014). However, it may not be universally protective, particularly when the broader legal context is hostile toward immigrants (Ebert and Ovink, 2014; Menjívar, 1997). As a context in which families experience immigrant policies, co-ethnic density could function in multiple ways to either buffer or exacerbate policy impacts. I test competing hypotheses regarding how county Latino density moderates the effect of omnibus immigrant law passage on Medicaid/CHIP coverage for US citizen Latino children with noncitizen parents.

Hypothesis 1:

For Latino citizen children in immigrant families, living in a county with high Latino density is protective against the negative effects of omnibus law passage on Medicaid/CHIP coverage. This could occur via the presence of ethnic support networks (Bécares et al., 2012; Bécares, 2014; Bertrand et al., 2000) and ethnic community-based organizations (Joassart-Marcelli, 2013) that disseminate information about the laws and children’s continuing eligibility for benefits, provide instrumental support such as transportation, and provide information about how to successfully apply for benefits (Bécares et al., 2012; Bertrand et al., 2000). If these mechanisms predominate after passage of an omnibus law, children in higher percent Latino counties may be more likely than their peers in lower percent Latino counties to stay enrolled in Medicaid/CHIP, or may re-enroll more quickly after the initial period of fear and misinformation is dispelled.

Hypotheses 2:

On the other hand, living in an area of high co-ethnic density may exacerbate the negative effects of omnibus law passage. In the context of omnibus immigrant laws, high Latino density counties may expose families to greater anti-immigrant discrimination (Ebert and Ovink, 2014) and more intense immigration enforcement (Chand and Schreckhise, 2015; Pedraza and Zhu, 2013). In the absence of restrictive immigrant laws, Mexican-origin adults in counties with high co-ethnic density report less discrimination than their counterparts in other counties. However, in the presence of local restrictive immigrant ordinances, Mexican-origin adults in high co-ethnic density counties report greater discrimination (Ebert and Ovink, 2014). Both immigration enforcement and discrimination discourage parents from seeking public benefits and health care for their children (Pedraza and Zhu, 2013; Shavers et al., 2012), and parents reported both after omnibus law passage (Koralek et al., 2009; White et al., 2014b). In a sensitivity analysis (results not shown in the article), Watson (2014) reports that immigration enforcement has greater impacts on immigrant families’ Medicaid participation in cities with higher densities of noncitizens.

To test these hypotheses, I use a comparative interrupted time series (CITS) design and 15 years of data from the National Health Interview Survey. One of the strongest quasi-experimental designs for identifying causal effects in natural experiments (Shadish et al., 2002), CITS models change in level of Medicaid/CHIP enrollment at the time of law passage, change in trends over time, and whether effects persist long-term. CITS controls for pre-policy trends in states that passed omnibus laws and uses states that never passed omnibus laws as a comparison. This helps isolate policy effects from pre-existing trends (i.e., increasing Medicaid enrollment for Latino children nationwide) and from concurrent events occurring nationwide (e.g., the 2009 Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA)).

This study focuses on US citizen Latino children living in households with only noncitizen parents. NHIS does not measure legal status for noncitizens; the sample includes both undocumented parents and those with temporary or permanent legal status. There is debate about how to categorize households with mixed-status (one citizen and one noncitizen) parents (Oropesa et al., 2015). Health and health care access for children with mixed-status parents is better than children with noncitizen parents, but worse than those with citizen parents (Oropesa et al., 2015). In the face of restrictive immigrant laws, having one citizen parent may protect children’s access to benefits because the citizen parent may be more proficient in English; be more familiar with US bureaucratic processes in applying for benefits; and feel safer driving to program offices and completing enrollment paperwork and interviews (Burgos et al., 2005; Oropesa et al., 2015). However, applying for benefits may expose undocumented family members to detection by immigration authorities, or raise concerns among legal permanent resident parents that receiving benefits could jeopardize their eligibility to naturalize (Pedraza and Zhu, 2013; Perreira et al., 2012). Sensitivity analyses for mixed-status parents (though underpowered) are discussed below.

2. Methods

2.1. Data, Setting, and Sample

Individual-level data came from the 2005–2014 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), a nationally-representative survey of US households administered by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (National Center for Health Statistics, 2015). NHIS uses a complex sampling design, with county as the primary sampling unit. The same counties were followed for the 2006–2014 period, with a new cross-sectional sample of households each year (Parsons et al., 2014). The 2005 data included a different set of counties. I included 2005 to have multiple pre-policy time points for laws passed in 2006. Analyses excluding 2005 yielded similar results.

The sample was US citizen, Latino children, age 0–17, who had only noncitizen residential parents (NHIS does not collect information on nonresidential parents). The sample was limited to children who were either enrolled in Medicaid/CHIP or uninsured, in order to test whether law passage caused children to become uninsured (rather than moving to private insurance). Results including privately-insured children were similar. I excluded 299 children with missing data on any variable except family income, which was imputed (National Center for Health Statistics, 2014a). I limited the sample to children living in counties with at least 5% Latino because few children (n=491) lived in lower density counties. To ensure sufficient data support for the hypothesis tests, I limited the sample to the overlapping section of the percent Latino distribution between policy and non-policy states (5% – 57% Latino1). Ten non-policy states (AK, HI, ME, MT, NH, ND, OH, SD, VT, WV) were excluded because no sample children lived in counties ≥5% Latino. The final sample was 18,118 children.

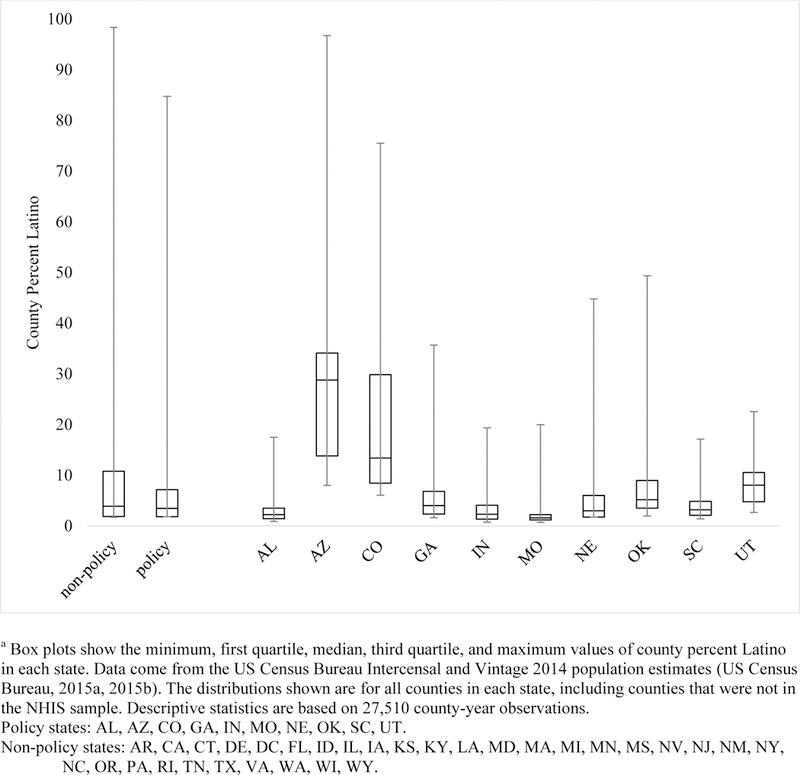

Because of disclosure risk, NCHS does not allow researchers to identify counties in the NHIS sample. Figure 1 shows the distribution of county percent Latino for all counties, including those not in the sample (US Census Bureau, 2015a, 2015b). Most counties in both policy and non-policy states have Latino densities less than 10%, but non-policy states have more, higher-density counties. Among policy states, Arizona and Colorado have higher Latino densities; the remaining policy states are new destination states with lower Latino densities.

Figure 1.

Distribution of county percent Latino for all counties in policy states, 2005—2014

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Individual-level variables

The outcome was a dichotomous variable indicating that the child was enrolled in either Medicaid or CHIP at the time of interview (vs. uninsured). Time was measured as the year and quarter-year when the interview occurred, beginning at 0 (January–March 2005) and counting each quarter through October–December 2014. Covariates included child’s age, gender, national origin, parent-rated health status, and health-related functional limitations; language of interview; which parents lived in the household; number of children in the family; highest education of either residential parent; and family income-to-poverty ratio.

2.2.2. Contextual variables

Information on omnibus immigrant laws came from the National Conference of State Legislatures (2018). The exposure was quarter-year of passage for the first omnibus law passed in each state (earliest: 2006 quarter 2; latest: 2011 quarter 2). I use law passage as the timing of exposure based on reports that fear, misinformation, and discrimination followed immediately after passage (Hardy et al., 2012; Koralek et al., 2009). Torche (2017) used Google analytics data to show that internet searches about Arizona’s 2010 omnibus law were highest immediately after passage; there was a corresponding worsening of birth outcomes for foreign-born Latinas who were pregnant at this time. I did not control for later omnibus laws because fewer children were exposed (n=940), but controlling for passage of a second law yielded similar results.

The percent of the county population who were Latino was a continuous, annual variable (range 5% – 57%) from US Census Bureau population estimates (US Census Bureau, 2015a, 2015b). There were no counties >40% Latino in policy states post-policy; these counties were only sampled pre-policy. Sensitivity analyses limited to 5% – 40% Latino produced similar results.

Annual county-level covariates included median income (US Census Bureau, 2015c); unemployment rate (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016); and rural/urban designation (National Center for Health Statistics, 2014b). Annual state-level covariates included percent change in the Latino population since the previous year and percent of the Latino population who were noncitizens (US Census Bureau, 2015b, 2015d), as well as 12 Medicaid/CHIP eligibility and enrollment policies (Appendix Table 2). Contextual variables were merged with NHIS based on quarter-year of interview and state/county of residence.

2.3. Analysis

Comparative interrupted time series (CITS) was used to estimate the effects of omnibus law passage on Medicaid/CHIP coverage, and to examine whether effects differed based on county percent Latino. CITS models preexisting trends in the outcome prior to law passage and estimates the effects of passage as the deviation from those trends. CITS includes a comparison group, states that did not pass an omnibus law.

The empirical model was:

Medicaid/CHIP = β0 + β1time + β2county percent Latino + β3omnibus law + β4(county percent Latino*omnibus law) + β5time after passage + β6(county percent Latino*time after passage) + βsstate + βiX + ε

Time is a linear time trend; sensitivity analyses indicated that a linear trend was appropriate. County percent Latino is a continuous measure of Latino density. Omnibus law is a dummy variable coded 1 if an omnibus law had passed in the child’s state before or during the quarter-year of interview. County percent Latino*omnibus law is an interaction between county percent Latino and the dummy indicator for law passage. Time after passage is a continuous variable counting the number of quarters since law passage, coded 0 prior to passage and beginning at 1 in the quarter after passage. County percent Latino*time after passage is an interaction between these variables. The model also includes time after passage squared and its interaction with county percent Latino (excluded from the equation above for simplicity). Omnibus law, time after passage, and their interactions with county percent Latino are coded 0 for all children in non-policy states. State is a series of state fixed effects, which adjust for unmeasured, time-invariant state characteristics. X includes all covariates.

β0 estimates Medicaid/CHIP coverage in January–March 2005 for children in 5% Latino counties. β1 estimates change in coverage over time in the absence of an omnibus law. β2 estimates the association between county percent Latino and Medicaid/CHIP coverage in the absence of an omnibus law.

The coefficients of interest are β3 – β6. β3 estimates the change in level of coverage at the time of law passage (e.g., a drop in Medicaid/CHIP enrollment upon passage) for children in 5% Latino counties. β4 allows this effect to differ by county percent Latino. β5 estimates a change in slope after passage (e.g., a leveling-off of the existing trend toward increasing enrollment over time) for children in 5% Latino counties. β6 allows this change in slope to differ based on county percent Latino.

Logistic regression models were estimated in Stata 14. To demonstrate the magnitude of the policy effects, predicted probabilities were calculated using nlcom commands, holding all covariates at their means. Analyses were weighted using person-level sampling poststratification weights; standard errors were adjusted using public-use stratum and PSU variables. Human subjects approval was obtained from the University of Wisconsin–Madison Institutional Review Board and NCHS Research Data Center Review Committee.

2.4. CITS assumptions and threats to validity

CITS assumes no unmeasured changes occurred in policy states around the same time as policy passage and impacted Medicaid/CHIP enrollment. To address this possible source of bias, I tested for policy effects on non-Latino White and Black children, who would be affected by events such as CHIPRA and the 2008–2009 recession, but should not be affected by omnibus law passage. The conditions that led to the passage of omnibus laws could also explain any observed policy effects, so I control for major predictors of state immigrant law passage, including state partisanship (a relatively time-invariant characteristic, captured by state fixed effects), Latino population growth, and economic conditions (Commins and Wills, 2017; Ybarra et al., 2016).

The analysis assumes that, in the absence of an omnibus law, policy and non-policy states would have followed similar trends in enrollment over the study period. Although this assumption cannot be tested, pre-policy trends in coverage were similar for both groups. The association between county percent Latino and Medicaid/CHIP enrollment did not vary over time or between policy and non-policy states.

An additional threat is that families may select into counties in a way that is correlated with both county percent Latino and the probability of having Medicaid/CHIP (e.g., if undocumented immigrants are less likely to enroll their children and more likely to settle in high percent Latino counties). I addressed this threat by controlling for county percent Latino (Bertrand et al., 2000). The main effect of county percent Latino may be biased by selection on unmeasured characteristics, but the interactions between county percent Latino and law passage should be unbiased unless selection varies over place and time.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Thirteen percent of the sample lived in policy states (Table 1). Compared to children in non-policy states, children in policy states were younger, more likely to be Mexican-origin, and more likely to have interviews in English. They were more likely to be in very good or excellent health but also more likely to have functional limitations. They were less likely to be enrolled in Medicaid/CHIP and, on average, lived in counties with lower percent Latino. For comparison of contextual variables, see Appendix Table 3.

Table 1:

Weighted descriptive statistics for key variables, Latino citizen children with only noncitizen parents (n=18,118), 2005—2014 National Health Interview Survey a

| States that did not pass an omnibus law b n=15,761 |

States that passed an omnibus law b n=2,357 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Child’s age | 7.0 (6.4)*** | 6.2 (5.8) |

| Child is male | 50.8% | 52.8% |

| Child’s national origin | ||

| Mexican | 78.4%*** | 89.9% |

| Central/South American | 15.8% | 7.4% |

| Other | 5.8% | 2.7% |

| Interview was conducted in English | 24.6%** | 30.8% |

| Family structure | ||

| Lives with both biological/adoptive parents | 67.7% | 67.3% |

| Lives with 1 biological/adoptive parent, one step parent | 2.7% | 4.4% |

| Lives with mother only | 24.3% | 22.6% |

| Lives with father only | 1.8% | 2.1% |

| Other | 3.4% | 3.6% |

| Number of children in family | 2.8 (1.7) | 2.8 (1.6) |

| Highest education level of either residential parent | ||

| Less than high school | 66.1% | 64.7% |

| High school diploma / GED | 28.1% | 28.8% |

| Associate’s degree | 2.9% | 3.9% |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 2.9% | 2.6% |

| Child’s parent-rated general health status | ||

| Fair or poor | 3.2%*** | 2.6% |

| Good | 28.9% | 19.8% |

| Very good | 27.8% | 35.3% |

| Excellent | 40.1% | 42.3% |

| Child has health-related functional limitations | 4.2%* | 5.5% |

| Family income-to-poverty ratio | 1.1 (0.9) | 1.0 (0.8) |

| Child is enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP | 85.6%*** | 78.6% |

| County percent Latino | 31.0 (18.7)*** | 18.9 (12.2) |

Mean (standard deviation) or proportion shown. Analyses were weighted using person-level sampling poststratification weights; standard errors were adjusted using NHIS public-use stratum and PSU variables. Unweighted sample sizes shown.

Policy states: AL, AZ, CO, GA, IN, MO, NE, OK, SC, UT.

Non-policy states: AR, CA, CT, DE, DC, FL, ID, IL, IA, KS, KY, LA, MD, MA, MI, MN, MS, NV, NJ, NM, NY, NC, OR, PA, RI, TN, TX, VA, WA, WI, WY.

p<.05,

p<.01

***p<.001

3.2. Multivariable results

Table 2 shows results for key variables from the fully-adjusted model; Appendix Table 4 shows full results. Medicaid/CHIP coverage increased over time (odds ratio (OR) 1.04 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.02–1.06)). In the absence of an omnibus law, there was a small, negative association between county percent Latino and Medicaid/CHIP enrollment; within the range of Latino density in the data, for every 10% increase in county percent Latino, the predicted probability of having coverage dropped by about two percentage points.

Table 2.

Effects of omnibus immigrant law passage on Medicaid/CHIP enrollment for Latino citizen children with only noncitizen parents (n=18,118), allowing effects to vary by county Latino density a

| OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Time (quarter-year) | 1.04 (1.02 – 1.06)*** |

| County percent Latino b | 0.99 (0.98 – 1.00)* |

| Main effects of omnibus law passage | |

| Omnibus law passage (change in level) | 1.34 (0.40 – 4.48) |

| Time after passage (change in slope) | 0.90 (0.79 – 1.01) |

| Time after passage squared (change in slope) | 1.00 (1.00 – 1.01) |

| Interactions between omnibus law passage and county percent Latino b | |

| (Omnibus law passage) * (County percent Latino) | 0.95 (0.90 – 0.99)* |

| (Time after passage) * (County percent Latino) | 1.00 (1.00 – 1.01) |

| (Time after passage squared) * (County percent Latino) | 1.00 (1.00 – 1.00) |

| Constant | 1.07 (0.04 – 25.10) |

| F-test | F (92, 387.0) = 14.39*** |

Results of comparative interrupted time series logistic regression models, adjusting for child’s age, gender, national origin, general health status, and health-related functional limitations; language of interview; which parents lived in the household; number of children in the family; highest education level of either residential parent; family income-to-poverty ratio; state percent of Latinos who were noncitizens; percent change in the state Latino population since the previous year; 12 state Medicaid/CHIP eligibility and enrollment policies; county median income; county unemployment rate; county NCHS rural/urban code; and state fixed effects. Analyses were weighted using person-level sampling poststratification weights; standard errors were adjusted using NHIS public-use stratum and PSU variables. Unweighted sample size = 18,118.

Policy states: AL, AZ, CO, GA, IN, MO, NE, OK, SC, UT.

Non-policy states: AR, CA, CT, DE, DC, FL, ID, IL, IA, KS, KY, LA, MD, MA, MI, MN, MS, NV, NJ, NM, NY, NC, OR, PA, RI, TN, TX, VA, WA, WI, WY.

Because the sample was limited to children in counties with at least 5% Latino, a value of 0 on county percent Latino here indicates 5% Latino.

OR = Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

At the time of omnibus law passage, children in 5% Latino counties experienced no significant change in either level or trend of Medicaid/CHIP coverage. However, there was a significant interaction between law passage and county percent Latino (OR on change in level*county percent Latino: 0.95 (95% CI 0.90 – 0.99)); as county percent Latino increased, omnibus law passage was associated with a drop in enrollment.

Table 3 and Figure 2 show this change in level for select values of county percent Latino. For children in 15% Latino counties, the effect of passage was negative but nonsignificant. In 25% Latino counties, passage resulted in a 10 percentage-point drop in the predicted probability of having coverage, from 90% in the quarter prior to passage to 80% in the quarter of passage. In 35% Latino counties, the predicted probability of having coverage decreased 21 percentage-points, from 88% to 67%. There was no significant interaction between county percent Latino and time after passage; the decrease in coverage at law passage persisted over time.

Table 3.

Effects of omnibus immigrant law passage on Medicaid/CHIP enrollment for Latino citizen children with only noncitizen parents (n=18,118) in counties at 5%, 15%, 25%, and 35% Latino a

| County percent Latino |

Change in level at passage OR (95% CI) |

Predicted probability of having coverage in the quarter prior to passage |

Predicted probability of having coverage in the quarter of passage |

Change in predicted probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5% Latino | 1.34 (0.40 – 4.48) | 91.5% | 93.8% | + 2.3% |

| 15% Latino | 0.78 (0.34 – 1.79) | 90.5% | 88.6% | − 2.0% |

| 25% Latino | 0.45 (0.24 – 0.83)* | 89.5% | 79.9% | − 9.6% |

| 35% Latino | 0.26 (0.13 – 0.53)*** | 88.4% | 67.2% | − 21.2% |

Odds ratios and predicted probabilities calculated from the multivariable model in Table 2 using nlcom estimation commands. Predicted probabilities calculated holding all variables except time, policy variables, and county percent Latino at their means. Odds ratios for change in slope (time after passage and time after passage squared) are not shown because all ORs were close to 1 and nonsignificant. Unweighted sample size = 18,118.

Policy states: AL, AZ, CO, GA, IN, MO, NE, OK, SC, UT.

Non-policy states: AR, CA, CT, DE, DC, FL, ID, IL, IA, KS, KY, LA, MD, MA, MI, MN, MS, NV, NJ, NM, NY, NC, OR, PA, RI, TN, TX, VA, WA, WI, WY.

OR=Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Figure 2.

Effects of omnibus immigrant law passage on the predicted probability of having Medicaid/CHIP coverage for Latino citizen children with only noncitizen parents (n=18,118) in counties at 5% and 35%Latino a

a For this figure, time is centered at policy passage (t); t−1 represents 1 year prior to passage, t+1 represents 1 year after passage, etc. Predicted probabilities were calculated from results in Table 2 using Stata nlcom commands, holding all variables except time, policy variables, and county percent Latino at their means. Unweighted sample size = 18,118.

Policy states: AL, AZ, CO, GA, IN, MO, NE, OK, SC, UT.

Non-policy states: AR, CA, CT, DE, DC, FL, ID, IL, IA, KS, KY, LA, MD, MA, MI, MN, MS, NV, NJ, NM, NY, NC, OR, PA, RI, TN, TX, VA, WA, WI, WY.

3.3. Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses tested the robustness of the findings to alternate samples and model specifications. First, I limited the sample to Mexican-origin children with only noncitizen parents (Appendix Table 5). Different Latino national origin groups have very different experiences before, during, and after migration (Bécares, 2014; Portes and Rumbaut, 2014); Mexican-origin children are the most likely to have undocumented parents (Pew Research Center, 2016), and thus are most likely to be impacted by omnibus laws. Results for Mexican-origin children (80% of the full sample) were similar to those for Latino children overall. Other national origin groups were too small to examine separately.

Second, I looked for spillover effects on children with only citizen parents or children with mixed-status parents (Appendix Table 6). There were no policy effects for children with only citizen parents, regardless of county percent Latino. The analysis for children with mixed-status parents (n=5,901) was underpowered. There was a nonsignificant trend toward decreased enrollment after law passage for children in high percent Latino counties. This trend was smaller than that for children with only noncitizen parents, but the estimate was not precise. When children with mixed-status parents were combined with only noncitizen parents as a single category, the results were similar to the main results for only noncitizen parents.

Third, to address the possibility that estimated policy effects were confounded by unmeasured, concurrent events that affected all children, I conducted analyses with US-citizen, non-Latino White and Black children (Appendix Table 7), who may have been affected by other contemporaneous events such as the recession but should not have been affected by omnibus law passage. There were no effects of law passage for these children.

Fourth, I allowed for a nonlinear effect of county percent Latino by treating it as a categorical variable with 10% increments (Appendix Table 8). Results were similar to the linear specification up to 35% Latino. The effect of law passage for the category 35–45% Latino was not significantly different from the effect at 5–15% Latino, likely because this category was small. A larger sample is needed to test various nonlinear specifications.

Fifth, I limited the comparison group to states adjacent to policy states in the West, Midwest, and Southeast (Appendix Table 9). If the observed policy effects were due to Medicaid-enrolled children moving from policy states to nearby states, the estimated effects should be larger when using nearby states as the comparison group (Orrenius and Zavodny, 2017). Estimated impacts were not significantly different from models using all non-policy states as the comparison.

Sixth, I excluded one state at a time and confirmed that no single state was driving the findings. Appendix Table 10 shows the models excluding Arizona and Colorado. Finally, I confirmed that the moderation effect of county percent Latino was not explained by county median income, poverty rate, or rural/urban status.

4. Discussion

In an atmosphere of increasingly restrictive immigration-related laws nationwide, there is growing interest in how local contexts buffer or exacerbate the negative impacts of these laws on health and health care access (Koralek et al., 2009; Philbin et al., 2017). This study is the first to address this question by asking whether county Latino density moderates the effect of omnibus immigrant law passage on Medicaid/CHIP coverage for Latino immigrant families.

In this nationally-representative sample of US citizen, Latino children with noncitizen parents, county percent Latino was negatively associated with Medicaid/CHIP enrollment in the absence of an omnibus law, perhaps capturing selection into counties based on unobserved characteristics (Bertrand et al., 2000). Omnibus immigrant law passage did not significantly affect Medicaid/CHIP enrollment in counties between 5% – 15% Latino; however, in counties above 15% Latino, passage resulted in a decrease in enrollment that persisted over time. This placed a significant number of children at risk of becoming uninsured. As of 2014, over 60% of Latinos in policy states (approximately 374,000 citizen children with noncitizen parents) lived in counties >15% Latino (Urban Institute, 2018; US Census Bureau, 2015a).

Children with mixed-status parents in high Latino density counties may experience smaller decreases in enrollment than children with noncitizen parents when their states pass omnibus laws. This is consistent with our understanding of health care access and barriers to care for mixed-status parents (Burgos et al., 2005; Oropesa et al., 2015), but this analysis was underpowered. Larger samples of children with mixed-status parents, as well as more detailed information on parent legal status, are needed to assess how policies affect different configurations of mixed-status families (Oropesa et al., 2015; Watson, 2014).

There were no spillover effects for Latino children with only citizen parents. Immigration enforcement and restrictive immigrant laws may harm physical and mental health for US-born Latinos (Novak et al., 2017; Philbin et al., 2017), but they do not appear to increase material hardship (Amuedo-Dorantes et al., 2016; Potochnick et al., 2016) or restrict access to public benefits and health care (Pedraza and Zhu, 2013; Quiroga et al., 2014; Watson, 2014) for Latinos when all family members are citizens.

4.1. Potential mechanisms and directions for future research

High Latino density counties are concentrated in Arizona and Colorado. Could the findings be attributed to differences in policy impacts across states rather than counties? Although sample sizes were too small to test for state-specific policy effects, this explanation is unlikely for a couple of reasons. First, the laws in Arizona and Colorado were not more restrictive than the other states; the severity of each state’s laws do not explain the findings. Second, results were robust to the exclusion of each state; the findings were not explained by a particularly punitive climate (or by other, concurrent changes) in one state with high Latino density. The laws likely impacted the most children in Arizona and Colorado, where more children live in high Latino density counties. However, even in the other policy states, a quarter of Latinos live in counties >15% Latino (US Census Bureau, 2015a).

Longitudinal data with additional individual and community measures are needed to explore why living in a high Latino density county exacerbated the negative effects of omnibus law passage, but the literature suggests possible explanations. First, Latino families in high Latino density counties may experience greater anti-immigrant discrimination after omnibus law passage, compared to their counterparts in lower density counties (Ebert and Ovink, 2014). Discrimination—particularly in health care and public benefits settings—reduces the likelihood that individuals will seek benefits and services (Shavers et al., 2012). Medicaid/CHIP are often administered at the county level (Perreira et al., 2012); organizational or staff practices in Medicaid/CHIP offices in high Latino density counties may have deterred noncitizen parents from enrolling their children (Koralek et al., 2009; White et al., 2014b). While a growing literature links discrimination to health care access and quality, more work is needed to understand how often anti-immigrant discrimination occurs in health care settings and to develop interventions to interrupt this pathway (Shavers et al., 2012).

Second, these findings may be explained if families in high Latino density counties are exposed to greater local immigration enforcement after omnibus law passage. Immigration enforcement is typically more intense in counties with higher Latino density (Chand and Schreckhise, 2015; Pedraza and Zhu, 2013), particularly in areas where immigration is a relatively new phenomenon, as is the case for most states with omnibus laws (Monogan, 2013). Immigration enforcement is associated with lower enrollment in public benefits for children of immigrants (Pedraza and Zhu, 2013; Vargas and Pirog, 2016; Watson, 2014). Future studies should incorporate measures of local enforcement to empirically test whether restrictive state and federal laws have more negative effects in areas with greater local enforcement.

Finally, the findings could be explained by outmigration of families most at-risk. Omnibus laws were designed to encourage undocumented immigrants to leave the state (Koralek et al., 2009). There is some evidence that restrictive state and local immigration laws lead to outmigration of immigrants and/or Latinos from the state (Bohn et al., 2014; Capps et al., 2011; Ellis et al., 2014; Orrenius and Zavodny, 2017; Watson, 2013; Wills and Commins, 2018). However, effects may be temporary (Sánchez, 2017), not all studies find significant outmigration in all states with restrictive laws (García, 2013; Orrenius and Zavodny, 2017), and there are conflicting findings about whether it is more-advantaged or less-advantaged Latinos who leave (Bohn et al., 2014; Ellis et al., 2014; Watson, 2014). Alternately, these families may have remained in the state but declined to participate in NHIS. In order to explain the findings, outmigration and/or nonresponse would need to occur differentially by county percent Latino. More evidence is needed to understand how restrictive immigrant laws affect migration and survey nonresponse, and whether some families or communities are disproportionately affected.

These findings, along with the existing body of work on the health impacts of state and local immigrant policies (Philbin et al., 2017), point to two additional gaps in the literature. First, in this study, I focused on effects at the time of law passage because evidence suggests the laws were salient as an environmental stressor as soon as they passed, before implementation (Koralek et al., 2009; Torche, 2017). Having an omnibus immigrant bill introduced and debated in the state legislature could also have chilling effects on public benefits enrollment, even if the bill does not pass. Future studies should examine whether there are effects when anti-immigrant bills are introduced in the state legislature and whether there are effects in states that consider, but do not pass, such bills.

Second, little is known about what might protect immigrant families against the harmful effects of restrictive immigration-related laws. Do local policies (e.g., sanctuary policies) and resources (e.g., funding for legal representation in immigration court) buffer the impacts of immigration enforcement and restrictive immigrant laws for children in immigrant families? Since 2011, the majority of state immigrant laws have expanded immigrants’ rights (Wills and Commins, 2018). Yet restrictive laws have received most attention, and few studies examine the health impacts of policies that expand rights for immigrants (Philbin et al., 2017). This is an important avenue for future research.

4.2. Limitations

This study has a few limitations. First, county Latino density is a relatively blunt measure of co-ethnic density, and different mechanisms may operate at different geographic levels (Bécares et al., 2012). Counties are important political units (Stone et al., 2015); both local immigration enforcement (Chand and Schreckhise, 2015) and provision of Medicaid/CHIP (Crosnoe et al., 2012; Perreira et al., 2012) often operate at the county level. However, protective ethnic network effects may emerge at smaller geographic scales (Pickett et al., 2009). In addition, the data do not include measures of segregation. The effects of law passage may differ in highly segregated, high Latino density counties, compared to more integrated counties (Bécares et al., 2012; Rocha and Espino, 2009). Future studies should include measures of segregation, as well as measures of ethnic density at smaller geographic levels.

Second, results could be biased if there was significant outmigration or nonresponse after law passage that occurred differentially based on county percent Latino; this could bias the estimates either upward or downward, depending on who left. Longitudinal data that tracks interstate migration could help address this question, but smaller sample sizes in existing longitudinal studies limit their utility for evaluating state policies.

Third, what I interpret as effects of omnibus law passage could be explained by unmeasured confounders. Although there were no effects on non-Latino White and Black children or Latino children with citizen parents, results could still be biased if some unmeasured change disproportionately affected Latino children with noncitizen parents.

Fourth, NHIS does not measure legal status for noncitizens. These results may underestimate policy effects for children of undocumented immigrants, who are most likely to be affected by laws targeting their undocumented parents. Finally, because of NHIS’s stratified sampling design, only a subset of counties was sampled. Very high percent Latino counties from policy states were not included; findings should not be extrapolated outside the range of Latino density in the data.

5. Implications for research and public health practice

This study is the first to demonstrate that state immigrant laws affect families differently based on local community characteristics. Living in a county with higher co-ethnic density placed Latino children in immigrant families at greater risk of losing Medicaid/CHIP when their state passed an omnibus immigrant law. Loss of coverage may place children at risk of poor health, education, and employment outcomes throughout life (Howell and Kenney, 2012).

Findings align with other research challenging the assumption that place-based co-ethnic density—as found in “ethnic enclaves”—is universally beneficial to health (Ebert and Ovink, 2014; Portes and Rumbaut, 2014). Though co-ethnic density may be protective in some domains, particularly with respect to resources generated within immigrant communities (Bécares, 2014; Bertrand et al., 2000; Joassart-Marcelli, 2013; Menjívar, 1997; Portes and Rumbaut, 2014), density may also trigger discrimination and policy responses that are harmful to migrant health (Chand and Schreckhise, 2015; Ebert and Ovink, 2014; Ybarra et al., 2016).

A growing literature demonstrates that the causes and consequences of state and local immigrant laws are complex and contingent. State economic, political, and demographic factors interact to spur state legislatures to pass either restrictive or expansive immigrant policies (Commins and Wills, 2017; Ybarra et al., 2016). These forces evolve over time; California passed the first restrictive state immigrant laws in the 1990s, but now has some of the most expansive immigrant laws in the nation (Colbern and Ramakrishnan, 2016). Similar to the present study, Watson (2014) and Ebert and Ovink (2014) find that the effects of immigration enforcement and local immigrant laws vary based on local contextual factors.

Together, these findings demonstrate the importance of evaluating how the effects of immigrant laws vary based on the contexts in which families live, to better target interventions for families and communities most likely to be impacted. Potential interventions, targeted toward counties with large Latino populations, could include educating health care providers, public benefits workers, and parents about the laws and citizen children’s continuing eligibility for benefits and services (Koralek et al., 2009); providing rides to program offices for immigrant parents afraid to drive (Hardy et al., 2012); and working with trusted community-based organizations to enroll children (Crosnoe et al., 2012). Findings have continued relevance: anti-sanctuary laws passed in North Carolina in 2015 and Texas in 2017 (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2018), as well as immigration policy proposals from the Trump administration, share many similarities with state omnibus immigrant laws.

Supplementary Material

Restrictive immigration laws may have spillover effects on US-born Latino children.

Evaluates the impact of state omnibus immigrant laws on Medicaid/CHIP enrollment.

Law passage reduced coverage for Latino citizen children with noncitizen parents.

Decreases in coverage were only observed in counties >15% Latino.

The health effects of immigrant laws are complex & vary across local communities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [grant number R36HS024248] and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) [grant number T32HD049302], and by an NICHD Center Grant to the Center for Demography and Ecology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison [grant number P2C HD047873]. The funding sources had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. This work was conducted while Dr. Allen was a Special Sworn Status researcher of the United States Census Bureau at the Center for Economic Studies. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, or the Census Bureau. Data files were created by Karon C. Lewis at the National Center for Health Statistics Research Data Center. This paper has been screened to ensure that no confidential data are revealed.

Footnotes

All ranges are approximate, as NHIS does not allow researchers to release ranges for variables.

Declarations of interest: none

References

- Allen CD, McNeely CA, 2017. Do restrictive omnibus immigration laws reduce enrollment in public health insurance by Latino citizen children? a comparative interrupted time series study. Soc. Sci. Med 191, 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- socscimed.2017.08.039. Amuedo-Dorantes C, Arenas-Arroyo E, Sevilla, A, 2016. Immigration enforcement and childhood poverty in the United States (IZA Discussion Papers No. 10030) Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Bécares L, 2014. Ethnic density effects on psychological distress among Latino ethnic groups: An examination of hypothesized pathways. Health Place 30, 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bécares L, Shaw R, Nazroo J, Stafford M, Albor C, Atkin K, Kiernan K, Wilkinson R, Pickett K, 2012. Ethnic density effects on physical morbidity, mortality, and health behaviors: A systematic review of the literature. Am. J. Public Health 102, e33–e66. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beniflah JD, Little WK, Simon HK, Sturm J, 2013. Effects of immigration enforcement legislation on Hispanic pediatric patient visits to the pediatric emergency department. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila.) 52, 1122–1126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922813493496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand M, Luttmer EFP, Mullainathan S, 2000. Network effects and welfare cultures. Q. J. Econ 115, 1019–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Bohn S, Lofstrom M, Raphael S, 2014. Did the 2007 Legal Arizona Workers Act reduce the state’s unauthorized immigrant population? Rev. Econ. Stat 96, 258–269. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00429 [Google Scholar]

- Brabeck KM, Sibley E, Taubin P, Murcia A, 2015. The influence of immigrant parent legal status on U.S.-born children’s academic abilities: The moderating effects of social service use. Appl. Dev. Sci. epub ahead of print https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2015.1114420

- Burgos AE, Schetzina KE, Dixon B, Mendoza FS, 2005. Importance of generational status in examining access to and utilization of health care services by Mexican American children. Pediatrics 115, e322–e330. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capps R, Rosenblum MR, Rodriguez C, Chishti M, 2011. Delegation and divergence: A study of 287(g) state and local immigration enforcement Migration Policy Institute, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Chand DE, Schreckhise WD, 2015. Secure communities and community values: Local context and discretionary immigration law enforcement. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud 41, 1621–1643. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.986441 [Google Scholar]

- Colbern A, Ramakrishnan K, 2016. State policies on immigrant integration: An examination of best practices and policy diffusion, UCR School of Public Policy Working Paper Series University of California Riverside, Riverside, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Commins MM, Wills JB, 2017. Reappraising and extending the predictors of states’ immigrant policies: Industry influences and the moderating effect of political ideology. Soc. Sci. Q 98, 212–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12283 [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, Pedroza JM, Purtell K, Fortuny K, Perreira KM, Ulvestad K, Weiland C, Yoshikawa J, Chaudry A, 2012. Promising practices for increasing immigrants’ access to health and human services, ASPE Issue Brief U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert K, Ovink SM, 2014. Anti-immigrant ordinances and discrimination in new and established destinations. Am. Behav. Sci 58, 1784–1804. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214537267 [Google Scholar]

- Ellis M, Wright R, Townley M, Copeland K, 2014. The migration response to the Legal Arizona Workers Act. Polit. Geogr 42, 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García A, 2013. Return to sender? A comparative analysis of immigrant communities in “attrition through enforcement” destinations. Ethn. Racial Stud 36, 1849–1870. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2012.692801 [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, Leal D, Rodriguez N, 2015. Deporting social capital: Implications for immigrant communities in the United States. Migr. Stud 3, 370–392. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnu054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan JM, Gonzales Baker S, 1993. Implementing the U.S. legalization program: The influence of immigrant communities and local agencies on immigration policy reform. Int. Migr. Rev 27, 513–536. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy LJ, Getrich CM, Quezada JC, Guay A, Michalowski RJ, Henley E, 2012. A call for further research on the impact of state-level immigration policies on public health. Am. J. Public Health 102, 1250–1254. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell EM, Kenney GM, 2012. The impact of Medicaid/CHIP expansions on children: A synthesis of the evidence. Med. Care Res. Rev 69, 372–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558712437245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupe P, 2014. What happens on the ground: Persistent issues in implementation research. Public Policy Adm 29, 164–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076713518339 [Google Scholar]

- Joassart-Marcelli P, 2013. Ethnic concentration and nonprofit organizations: The political and urban geography of immigrant services in Boston, Massachusetts. Int. Migr. Rev 47, 730–772. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12041 [Google Scholar]

- Koralek R, Pedroza J, Capps R, 2009. Untangling the Oklahoma Taxpayer and Citizen Protection Act: Consequences for children and families National Council of La Raza, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Laglaron L, Rodriguez C, Silver A, Thanasombat S, 2008. Regulating immigration at the state level: Highlights from the database of 2007 state immigration legislation and the methodology Migration Policy Institute, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Johnson KM, 2009. Immigrant gateways and Hispanic migration to new destinations. Int. Migr. Rev 43, 496–518. https://doi.org/0.111l/j.l747-7379.2009.00775.x [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar C, 1997. Immigrant kinship networks and the impact of the receiving context: Salvadorans in San Francisco in the early 1990s. Soc. Probl 44, 104–123. [Google Scholar]

- Monogan JE, 2013. The politics of immigrant policy in the 50 US states, 2005–2011. J. Public Policy 33, 35–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X12000189 [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics, 2015. National Health Interview Survey. Public-use data file and documentation National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics, 2014a. Multiple imputation of family income and personal earnings in the National Health Interview Survey: Methods and examples National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics, 2014b. NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties [WWW Document]. Data Access URL August 1, 2015

- National Conference of State Legislatures, 2018. State laws related to immigration and immigrants [WWW Document]. Res. Immigr URL http://www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/state-laws-related-to-immigration-and-immigrants.aspx (accessed 7.19.18).

- Novak NL, Geronimus AT, Martinez-Cardoso AM, 2017. Change in birth outcomes among infants born to Latina mothers after a major immigration raid. Int. J. Epidemiol. epub ahead of print https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oropesa RS, Landale NS, Hillemeier MM, 2015. Family legal status and health: Measurement dilemmas in studies of Mexican-origin children. Soc. Sci. Med 138, 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrenius PM, Zavodny M, 2017. Digital enforcement: Effects of E-Verify on unauthorized immigrant employment and population Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Dallas, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons VL, Moriarty C, Jonas K, Moore T., Davis KE, Tompkins L., 2014. Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 2006–2015. Vital Health Stat., Vital and Health Statistics 2, 1–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza FI, Zhu L, 2013. Immigration enforcement and the “chilling effect” on Latino Medicaid enrollment. Presented at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Annual Meeting of the Scholars in Health Policy Research, Princeton, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, Crosnoe R, Fortuny K, Pedroza J, Ulvestad K, Weiland C, Yoshikawa H, Chaudry A, 2012. Barriers to immigrants’ access to health and human services programs, ASPE Issue Brief U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center, 2016. Unauthorized immigrant population trends for states, birth countries and regions [WWW Document]. Pew Res. Hisp. Trends URL http://www.pewhispanic.org/interactives/unauthorized-trends/ (accessed 5.4.17).

- Pham H, 2008. Problems facing the first generation of local immigration laws. Hofstra Law Rev 36, 1303–1311. [Google Scholar]

- Philbin MM, Flake M, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hirsch JS, 2017. State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. epub ahead of print https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pickett KE, Shaw RJ, Atkin K, Kiernan KE, Wilkinson RG, 2009. Ethnic density effects on maternal and infant health in the Millennium Cohort Study. Soc. Sci. Med 69, 1476–1783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG, 2014. Immigrant America: A portrait, updated, and expanded, 4th ed. University of California Press, Oakland, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Potochnick S, Chen JH, Perreira K, 2016. Local-level immigration enforcement and food insecurity risk among Hispanic immigrant families with children: National-level evidence. J. Immigr. Minor. Health epub ahead of print, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0464-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Quiroga SS, Medina DM, Glick J, 2014. In the belly of the beast: Effects of anti-immigration policy on Latino community members. Am. Behav. Sci 58, 1723–1742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214537270 [Google Scholar]

- Rocha RR, Espino R, 2009. Racial threat, residential segregation, and the policy attitudes of Anglos. Polit. Res. Q 62, 415–426. https://doi.org/10,1177/106591290832093 [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez GE, 2017. The short-term response of the Hispanic noncitizen population to anti-illegal immigration legislation: The case of Arizona SB 1070. J. Econ. Finance Adm. Sci 22, 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEFAS-02-2017-0034 [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT, 2002. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference, 2nd ed. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, Fagan P, Jones D, Klein WMP, Boyington J, Moten C, Rorie E, 2012. The state of research on racial/ethnic discrimination in the receipt of health care. Am. J. Public Health 102, 953–966. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone LC, Boursaw B, Bettez SP, Marley TL, Waitzkin H, 2015. Place as a predictor of health insurance coverage: A multivariate analysis of counties in the United States. Health Place 34, 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Williams DR, Harvey-Mendoza E, Jahromi LB, Updegraff KA, 2014. Impact of Arizona’s SB 1070 immigration law on utilization of health care and public assistance among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers and their mother figures. Am. J. Public Health 104, S28–S34. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torche F, 2017. The effect of immigration policy on infant health: The Arizona SB1070 as a natural experiment. Presented at the Population Association of America 2017 Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Torres JM, Young MED, 2016. A life-course perspective on legal status stratification and health. SSM - Popul. Health 2, 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban Institute, 2018. The Urban Institute children of immigrants data tool [WWW Document] URL http://datatool.urban.org/charts/datatool/pages.cfm (accessed 1.12.18).

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016. Local Area Unemployment Statistics (LAUS) [WWW Document] US Bur. Labor Stat; URL http://www.bls.gov/lau/ (accessed 4.22.16). [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau, 2015a. County characteristics: Vintage 2014 [WWW Document]. Popul. Estim URL https://www.census.gov/popest/data/counties/asrh/2014/index.html (accessed 4.24.16).

- US Census Bureau, 2015b. Intercensal estimates (2000–2010) [WWW Document]. Popul. Estim URL https://www.census.gov/popest/data/intercensal/index.html (accessed 4.24.16).

- US Census Bureau, 2015c. Model-based Small Area Income & Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) for school districts, counties, and states [WWW Document]. Small Area Income Poverty Estim URL http://www.census.gov/did/www/saipe/ (accessed 7.9.15).

- US Census Bureau, 2015d. State characteristics: Vintage 2014 [WWW Document]. Popul. Estim URL https://www.census.gov/popest/data/state/asrh/2014/index.html (accessed 4.24.16).

- Vargas ED, Pirog MA, 2016. Mixed-status families and WIC uptake: The effects of risk of deportation on program use. Soc. Sci. Q 97, 555–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson T, 2014. Inside the refrigerator: Immigration enforcement and chilling effects in Medicaid participation. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 6, 313–338. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.6.3.313 [Google Scholar]

- Watson T, 2013. Enforcement and immigrant location choice (NBER Working Paper No. 19626) National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- White K, Blackburn J, Manzella B, Welty E, Menachemi N, 2014a. Changes in use of county public health services following implementation of Alabama’s immigration law. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 25, 1844–1852. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2014.0194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K, Yeager VA, Menachemi N, Scarinci IC, 2014b. Impact of Alabama’s immigration law on access to health care among Latina immigrants and children: Implications for national reform. Am. J. Public Health 104, 397–405. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301560) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills JB, Commins MM, 2018. Consequences of the American states’ legislative action on immigration. J. Int. Migr. Integr epub ahead of print https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-018-0588-7

- Wong TK, García AS, 2016. Does where I live affect whether I apply? The contextual determinants of applying for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. Int. Migr. Rev 50, 699–727. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12166 [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra VD, Sanchez LM, Sanchez GR, 2016. Anti-immigrant anxieties in state policy: The Great Recession and punitive immigration policy in the American states, 2005–2012. State Polit. Policy Q 16, 313–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532440015605815 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.