Abstract

Self-medication theory posits that some trauma survivors use alcohol to cope with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, but the role of negative posttraumatic cognitions in this relationship is not well defined. We examined associations among PTSD symptoms, posttraumatic cognitions, and alcohol intoxication frequency in 290 men who have sex with men (MSM), who reported a history of childhood sexual abuse (CSA). Using a bootstrap approach, we examined the indirect effects of PTSD symptoms on alcohol intoxication frequency through posttraumatic cognitions regarding the self, world, and self-blame. In separate regression models, higher levels of PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic cognitions were each associated with more frequent intoxication, accounting for 2.6% and 5.2% of the variance above demographics, respectively. When examined simultaneously, posttraumatic cognitions remained significantly correlated with intoxication frequency whereas PTSD symptoms did not. Men reporting elevated posttraumatic cognitions faced increased odds for current alcohol dependence, odds ratio (OR) = 2.19, 95% CI [1.13, 4.22], compared with men reporting low posttraumatic cognitions, independent of current PTSD diagnosis. A higher level of PTSD symptom severity was indirectly associated with more frequent alcohol intoxication through cognitions about the self and world; the indirect to total effect ratios were 0.74 and 0.35, respectively. Negative posttraumatic cognitions pertaining to individuals’ self-perceptions and appraisals of the world as dangerous may play a role in self-medication with alcohol among MSM with a history of CSA. Interventions targeting these cognitions may offer potential for reducing alcohol misuse in this population, with possible broader implications for HIV-infection risk.

The self-medication hypothesis (Khantzian, 1997), which posits that some trauma survivors may use alcohol in an attempt to relieve distressing posttraumatic symptoms, is well-supported in the scientific literature. Data from the National Comorbidity Study indicated that up to 52% of men and over 28% of women with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) meet criteria for lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence (Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995). This compares to a much lower prevalence of only 6.6% in adults in the general population (SAMHSA, 2014). In addition, numerous studies have described the positive association between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use (e.g., see Debell et al., 2014 for a review), and other reports have indicated that increases in PTSD symptoms are associated with increases in alcohol use (e.g., Bremner, Southwick, Darnell, & Charney, 1996). Regarding the directionality of this association, there is some evidence suggesting that posttraumatic symptoms develop prior to the onset of problematic alcohol use (Chilcoat & Breslau, 1998; McFarlane, 1998). Findings showing that alcohol use varies as a function of PTSD symptom severity are often interpreted within the context of the self-medication hypothesis and are done so across various populations, including women (Stewart, Conrod, Pihl, & Dongier, 1999), adolescents (Kilpatrick et al., 2003), individuals with severe mental illness (O’Hare & Sherrer, 2011), and veterans (Jakupcak et al., 2010).

Few studies, however, have examined the association between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use in men who have sex with men (MSM). This represents a gap in the literature because MSM are disproportionately affected by childhood sexual trauma as well as heavy alcohol use and alcohol-related problems (Paul, Catania, Pollack, & Stall, 2001; Stall et al., 2001). A large population-based study by Sweet and Welles (2012) showed that bisexual men were 12.8 times more likely than heterosexuals to have experienced childhood sexual abuse (CSA), and gay men were 9.5 times more likely to have experienced CSA. Other studies using smaller convenience samples have reported comparably high rates of CSA among MSM, with some reaching as high as 40% (Doll et al., 1992; Lenderking et al., 1997; Mimiaga et al., 2009); this compares with rates as low as 5.2% among men overall (Sweet & Welles, 2012).

Findings from some large studies have indicated that a history of CSA is associated with problematic alcohol use in MSM. Specifically, two large national studies by Mimiaga et al. (2009) and Stall et al. (2001) found that men with a history of CSA were significantly more likely to report heavy alcohol use than MSM without a history of CSA, odds ratio (OR) = 1.26 and OR = 1.6, respectively. More recently, data from a national 4-year longitudinal study by Marshall et al. (2015) showed that MSM with a CSA history followed more severe heavy-drinking trajectories than those without CSA. Although these studies offer evidence for an association between the experience of CSA and alcohol misuse in MSM, the extent to which alcohol use is associated with PTSD symptoms in this population remains unclear.

It is plausible that posttraumatic cognitions (PTCs; i.e., negative self-perceptions, negative beliefs about the world, and self-blaming thoughts) may also be associated with increased alcohol use among trauma survivors. Negative PTCs arise from rigid and excessively negative appraisals about the trauma and the sequelae of the trauma (i.e., PTSD symptoms) and often lead to distorted perceptions that the world is entirely dangerous and/or one’s self is entirely incompetent, vulnerable, and permanently changed for the worse (Foa, Ehlers, Clark, Tolin, & Orsillo, 1999). In turn, these maladaptive appraisals work to maintain a sense of current threat that manifests as persistent PTSD symptoms (e.g., avoidance, negative alterations to mood, hyperarousal and/or hypervigilance). Accordingly, researchers have repeatedly shown negative PTCs to be elevated among individuals who develop PTSD following sexual trauma and correlated with PTSD symptom severity (Dalgleish, 2004; Dunmore, Clark, & Ehlers, 2001; Ehlers & Clark, 2000).

Few studies have examined whether posttraumatic beliefs are associated with alcohol-related problems. In one study, Jayawickreme, Yasinski, Williams, and Foa (2012) found that negative PTCs were positively associated with alcohol cravings in men with comorbid PTSD and alcohol dependence. Najavits, Gotthardt, Weiss, and Epstein (2004) found higher levels of trauma-related cognitive distortions in women with comorbid PTSD and alcohol and/or substance use disorders than in those with PTSD alone. Most recently, Allwood, EspositoSmythers,Swenson,andSpirito(2014)reportedapositiveassociation between PTCs and symptoms of alcohol use disorders in psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. Additionally, the authors found that the association between PTSD diagnosis and symptoms of alcohol use disorders was stronger among individuals with more negative PTCs about one’s self. The authors interpreted this moderating effect within a self-medication context, raising the question of whether some individuals might use alcohol in part to relieve distressing negative PTCs. Collectively, these studies have provided evidence that PTCs may be an important correlate of alcohol-related problems; however, none of the studies measured alcohol use frequency, and only one included adult men.

Based on the literature reviewed thus far, we proposed a model in which PTCs mediate the positive association between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use. In other words, it may be reasonable to hypothesize that PTSD symptoms give rise to emotionally distressing PTCs and, in turn, individuals experiencing elevated PTCs may use alcohol to dampen or self-medicate against their resulting emotional distress rather than their PTSD symptoms per se. Indeed, fundamental models of PTSD posit that negative PTCs are paired with strong, poorly regulated negative emotional states that often motivate engagement in dysfunctional avoidance behaviors (e.g., substance abuse) to temporarily relieve emotional distress (Ehlers & Clark, 2000; Foa et al., 1999). Additionally, numerous experimental studies involving traumatized individuals have indicated that trauma cues and related negative emotional states appear to trigger alcohol cravings driven by motivations for relief of emotional distress (Coffey, Stasiewicz, Hughes, & Brimo, 2006; Hruska & Delahanty, 2012; Lehavot, Stappenbeck, Luterek, Kaysen, & Simpson, 2014; O’Hare & Sherrer, 2011). Thus, whereas Allwood et al. (2014) found support for their conceptualization of PTCs as a moderator of the PTSD–alcohol association, we propose that it is alternatively and simultaneously plausible that negative PTCs be appropriately conceptualized as a mediator.

Using baseline data from a randomized clinical trial, we undertook the current study to elucidate the role of negative PTCs within the association between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use in a sample of MSM with a history of CSA. First, we expected that PTSD symptom severity would be positively correlated with frequency of alcohol use to intoxication and that men with a current PTSD diagnosis would be more likely than those without PTSD to have a concurrent alcohol dependence diagnosis. Second, we hypothesized that higher levels of negative PTCs would be associated with more frequent alcohol intoxication after controlling for PTSD symptoms. Finally, we hypothesized that PTSD symptoms would be indirectly associated with more frequent use of alcohol to intoxication through negative PTCs.

Method

Participants

A total of 290 adult men were screened for participation in a multisite randomized clinical trial examining the effects of a psychological intervention on sexual risk behavior in sexually risky HIV-uninfected MSM with a history of CSA that occurred before the age of 17 years. The study sites were located in Boston, Massachusetts, and Miami, Florida. All participants were recruited via flyers and advertising placed at various community locations, including gay bars, clubs, and clinics, as well as through community outreach and online advertising (e.g., electronic dating applications commonly used by MSM). Participants completed a comprehensive diagnostic assessment involving both self-report questionnaires and interviews with trained clinicians. Demographic information for the overall sample is shown in Table 1. The sample was, on average, middle-aged (M = 38.0 years, SD = 11.7). By self-report, 70.0% of participants identified as Caucasian, 29.6% identified as ethnically Hispanic, and 68.6% identified as gay or homosexual. The majority of participants were well educated, from the middle class, and single.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total sample | 290 | 100 |

| Age (M and SD) | 37.95 | 11.68 |

| Race | ||

| Euro American | 203 | 70.0 |

| African American | 66 | 22.3 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 11 | 3.7 |

| Native American | 7 | 2.4 |

| Ethnicity (across all racial categories) | ||

| Latino | 87 | 29.6 |

| Income (USD) | ||

| < $10,000 per year | 88 | 30.3 |

| ≥$40,000 per year | 83 | 28.6 |

| Educational Attainment | ||

| Some high school | 14 | 4.8 |

| High school diploma | 59 | 20.4 |

| Some college | 106 | 36.7 |

| College graduate | 53 | 18.3 |

| Some graduate or above | 57 | 19.7 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay/homosexual | 199 | 68.6 |

| Bisexual | 64 | 22.1 |

| Heterosexual | 7 | 2.4 |

| Unsure/other | 20 | 6.9 |

| Relational Status | ||

| Partnered | 76 | 26.3 |

| Single | 213 | 73.7 |

| Current PTSD | 125 | 42.2 |

| Current alcohol dependence | 60 | 20.3 |

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Procedure

Trained clinical staff screened prospective participants over the phone using a brief structured questionnaire. Individuals who self-reported being an MSM with a CSA history and a recent unprotected sexual encounter were invited for a baseline evaluation. At baseline, participants provided informed consent, completed self-report computer- and paper-based psychosocial assessments, and underwent a CSA interview as well as a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation (Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview [MINI]; Sheehan et al., 1998) with a trained clinician. Sexual risk behavior was self-reported via a detailed computerized survey. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the present study were the same as for the parent study. Eligible participants were required to (a) be at least 18 years old; (b) identify as a biological man who has sex with men; (c) report sexual contact before the age 13 years with a person 5 years older, between the ages of 13 and 17 years with a person 10 years older (or any age with the threat of force or harm); (d) report more than one episode of unprotected anal or vaginal intercourse within the past 3 months; and (e) be HIV uninfected (confirmed with blood test). Participants were excluded for unmanaged severe mental illness (e.g., untreated severe mood disorders, psychotic disorders) or completion of cognitive processing therapy for PTSD within the past year. All procedures were approved by the institutional review board at each study site. A more detailed description of these procedures can be found elsewhere (Boroughs et al., 2015).

Measures

PTSD symptomology.

Trained clinicians administered the PTSD section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-IV; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997) to assess current PTSD diagnosis. Additionally, PTSD symptom severity was assessed via the total score of the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS; Davidson et al., 1997), which was administered as an interview by a trained clinician. The DTS is a 17-item measure based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV) PTSD symptom clusters. Each item is rated from 0 to 4 for both frequency (0 = not at all to 4 = every day) and severity (0 = not at all distressing to 4 = extremely distressing) during the past week. Items are summed for a total score with a possible range of 0 to 136. Scores of 40 or higher indicate likely PTSD. In our sample, the total score’s internal consistency was very good(Cronbach’s α= .88). Participants were instructed to respond based on their experience of PTSD symptoms specifically related to a specific instance of CSA.

Alcohol use frequency and alcohol dependence.

Frequency of current alcohol use to intoxication was assessed using a single item selected from the clinician-administered alcohol and substance use module of the Addiction Severity Index–Lite (ASI–Lite). Specifically, participants were asked to report the number of days out of the last 30 that they used alcohol to intoxication. The ASI–Lite, which is an abbreviated version of the Addiction Severity Index (Cacciola, Alterman, McLellan, Lin, & Lynch, 2007), is a semistructured interview that assesses seven psychosocial domains (medical, legal, family/social, alcohol, drug, employment, and psychiatric). It is a widely used instrument for assessing substance use problems and is recommended by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (Hartzler, Donovan, & Huang, 2011). Validity and reliability are well established (Cacciola et al., 2007). The ASI alcohol use scores have been validated against DSM alcohol use disorder-related symptomatology (Alterman et al., 1998). Participants’ current alcohol dependence was assessed via the clinician-administered MINI psychiatric interview (Sheehan et al., 1998), which has been validated against DSM-IV criteria.

Negative posttraumatic cognitions.

The Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI) (Foa et al., 1999) is a 36-item self-report instrument designed to assess negative PTSD-related thoughts and beliefs. The PTCI has high levels of internal consistency, test–retest reliability, criterion validity, and convergent validity. Respondents rate the degree to which they agree (1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree) with trauma-related thoughts and beliefs (total score range: 36–252). Individual items load on three empirically derived subscales: Negative Cognitions About Self (e.g., “If I think about the accident, I will not be able to handle it”), Negative Cognitions About the World (e.g., “The world is a dangerous place), and Self-Blame (e.g., “There is something about me that made the accident happen”). Higher scores indicate more endorsement of the negative PTC. In our sample, the internal consistency of the scales was generally excellent (total score, Cronbach’s α= .96; Negative Cognitions About Self subscale, Cronbach’s α= .96; Negative Cognitions About the World subscale, Cronbach’s α=.90;SelfBlame, Cronbach’s α= .80). Mean item scores were computed for each subscale to facilitate interpretation.

Data Analysis

We computed means and standard deviations for all continuous variables using SPSS software (Version 22). Prevalence rates of PTSD and alcohol dependence were generated through frequency counts and percentages. Data missing at random were deleted listwise (there were fewer than 10 cases per variable with missing data).

Covariates.

We selected the demographic variables of age, race (African American = 1, other = 0), ethnicity (Latino = 1, other=0),and educational attainment as covariates. These were chosen because the literature shows that they are each associated with substance use (Dolezal, Carballo-Diéguez, Nieves-Rosa, & Díaz, 2000; Marshall et al., 2015; Reisner et al., 2010) and because we wanted to stay consistent across other papers from the parent study (Boroughs et al., 2015).

Direct effects.

In a series of ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regression models adjusted for demographic covariates, we first tested whether PTSD symptom severity (i.e., DTS total score) was directly correlated with alcohol intoxication frequency. Next, in a separate model, we examined whether PTCs (i.e., PTCI total score) were associated with alcohol intoxication frequency. To assess the unique contribution of PTCs to the explained variance in alcohol intoxication frequency, we also tested this model with PTSD symptom severity included as an additional control variable. Of note, negative binomial regression is an alternative statistical approach for analyzing count data that may be overdispersed (e.g., alcohol intoxication frequency). In order to be thorough, we also conducted our primary analyses using negative binomial regression models to confirm the findings.

Odds ratios.

In order to make the results more clinically interpretable, we conducted a series of logistic regression analyses to examine the odds of meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000) for alcohol dependence. First, we compared men with a current PTSD diagnosis with those without PTSD (PTSD = 1, no PTSD = 0). Second, in a separate model, we compared men who reported total PTCI scores at or above the median value (i.e., PTCI total score ≥ 116) with men who reported PTCI scores below the median value (high PTCs = 1, low PTCs = 0), both with and without controlling for current PTSD diagnosis. Demographic covariates were included in each model.

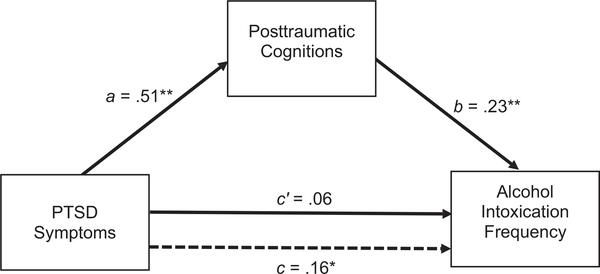

Indirect effects.

We used the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2012) to estimate the standardized OLS regression coefficient for the indirect path from PTSD symptom severity to alcohol intoxication frequency through total PTCs, while controlling for demographic covariates, with 5,000 bootstrapped samples. This coefficient was derived by calculating the product of the OLS regression coefficients estimating the paths from PTSD symptoms to total PTCs (a path), and from total PTCs to alcohol intoxication frequency (b path). A bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval for the product of the a and b paths that does not include zero indicates a significant indirect effect of PTSD symptoms on intoxication frequency through negative PTCs (Hayes, 2012; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). An illustration of this model is provided in the Results section (see Figure 1). We repeated this analysis for each of the three PTCI subscales.

Figure 1.

Path coefficients for indirect and direct paths from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms to alcohol intoxication frequency through total posttraumatic cognitions. The dotted line denotes the direct path from PTSD symptoms to alcohol intoxication frequency when posttraumatic cognitions are not included as a mediator. a, b, c, and c’ are standardized ordinary least squares regression coefficients. Demographic covariates were included but are not pictured here. *p < .01. **p < .001.

Results

As shown in Table 1, approximately 42% of participants met DSM-IV-TR criteria for current PTSD, and 20% met criteria for current alcohol dependence. For comparison, 38.2% of participants were at or above the cutoff score for PTSD based on the DTS. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for frequency of alcohol intoxication, DTS total scores, and PTCI total and sub-scale scores. On average, participants reported drinking to intoxication approximately 3 days in the past month (SD = 5.76). In the original paper that validated the PTCI (Foa et al., 1999), the authors reported that the median total score for individuals (a) without trauma exposure was 45.5, (b) with trauma exposure but no PTSD was 49, and (c) with both trauma exposure and PTSD was 133. In our sample, the median total PTCI score was 116. Thus, by comparison, the vast majority of participants in our sample fell between being trauma-exposed with no PTSD (96.6% scored ≥ 49) and having PTSD (39.3% scored ≥ 133). Results from zero-order Pearson correlation analyses among key variables are also displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Among Key Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Alcohol usea | — | −.13* | .12* | −.09 | −.12* | .17** | .22** | .17** | .02 | .20** |

| 2. | Age | — | −.05 | −.15** | .05 | .05 | .01 | .03 | .08 | .03 | |

| 3. | African American | — | −.20** | .17** | .02 | −.02 | .02 | −.07 | −.02 | ||

| 4. | Hispanic | — | .07 | −.04 | .13* | .22** | .08 | .16** | |||

| 5. | Education | — | .17** | −.09 | −.16** | .10 | −.10 | ||||

| 6. | PTSD symptoms | — | .53** | .39** | .18** | .51** | |||||

| 7. | PTCI-Self | — | .69** | .49** | .97** | ||||||

| 8. | PTCI- World | — | .36** | .81** | |||||||

| 9. | PTCI- Self-Blame | — | .61** | ||||||||

| 10. | PTCI-Total | — | |||||||||

| M | 3.10 | 37.95 | 34.55 | 2.99 | 4.28 | 3.42 | 119.86 | ||||

| SD | 5.76 | 11.68 | 26.21 | 1.32 | 1.52 | 1.44 | 43.22 |

Notes. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; PTCI = Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory.

Number of times in the past 30 days that participants drank to intoxication.

p < .05.

p < .01.

As shown in Table 3, alcohol intoxication frequency was regressed on PTSD symptom severity and total negative PTCs in five regression models that were adjusted for demographic covariates. Covariates alone accounted for 3.8% of the variance in intoxication frequency. When examined separately from PTCs, PTSD symptom severity was significantly associated with alcohol intoxication frequency (Model 1), β= .16, t(274) = 2.75, p = .006, R2= .064. When examined separately from PTSD symptoms, PTCs were significantly associated with alcohol intoxication frequency (Model 2), β = .23, t(276) = 3.94, p < .001, R2 = .090. Negative PTCs accounted for an additional 5.2% of the variance in alcohol use over covariates. When PTCs and total PTSD symptoms were examined simultaneously (Model 3), R2 = .092, total PTSD symptoms dropped to nonsignificance, β= .06, t(271) = 0.85, p = .395, whereas PTCs remained significant, β = .20, t(271) = 2.86, p = .005, in the model. Negative PTCs accounted for an additional 2.8% of the variance in intoxication frequency above and beyond PTSD symptoms and covariates, whereas PTSD symptoms only accounted for 0.2% of the variance above PTCs and covariates.

Table 3.

Alcohol Intoxication Frequency Regressed on Posttraumatic Cognitions and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Symptoms

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −.14* | −.15* | −.15* | −.15* | −.16** | −.15* |

| Race | .05 | .05 | .05 | .05 | .04 | .05* |

| Ethnicity | −.08 | −.12* | −.12 | −.11 | −.12 | −.08 |

| Education | −.06 | −.07 | −.06 | −.06 | −.05 | −.07 |

| PTSD symptoms | .16** | − | .06 | .04 | .11 | .16* |

| Total PTCI | − | .23** | .20** | − | − | − |

| PTCI-Self | − | − | − | .22** | − | − |

| PTCI-World | − | − | − | − | .14* | − |

| PTCI-Blame | − | − | − | − | − | .01 |

| Total R2 | .064 | .090 | .092 | .098 | .079 | .064 |

Notes. Standardized regression coefficients are presented for each model. The R2 for the base model (covariates only) was .038. PTCI = Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Our confirmatory analyses, using negative binomial regression, yielded consistent findings with those reported earlier in this article. In separate models that were adjusted for demographic covariates, PTSD symptom severity, b = 0.013, SE = .005, Wald χ2(1, N = 280) = 7.07, p = .008, and total PTCs, b = 0.012, SE = .003, Wald χ2(1, N = 282) = 16.02, p< .001, were each significantly associated with more frequent intoxication.

The OLS regression analyses described above were repeated for each subscale of the PTCI. Controlling for demographic covariates and PTSD symptoms, frequency of alcohol intoxication was significantly associated with PTCs regarding the self (Model 4), β= .22, t(271) = 3.18, p = .002, R2 = .098, and the world (Model 5), β = .14, t(271) = 2.09, p = .037, R2 = .079. Severity of PTSD symptoms was no longer significantly associated with intoxication frequency in either model. Self-blame PTCs were not significantly associated with intoxication frequency (Model 6), β= .01, t(271) = .18, p = .859, R2= .064.

A chi-square analysis revealed that 28.5% of participants with current PTSD met criteria for current alcohol dependence compared with 15.0% of participants without current PTSD,χ2(1, N = 283) = 7.63, p = .006. Similarly, 27.5% of participants with high PTCs met criteria for alcohol dependence compared with 14.9% of participants with low PTCs, χ2(1, N = 283) = 6.69, p = .010.

Controlling for demographic covariates, men with current PTSD were significantly more likely to meet criteria for current alcohol dependence than those without PTSD before, OR = 2.02, 95% CI [1.09, 3.75], but not after additional control for total PTCs, OR = 1.65, 95% CI [0.87, 3.14]. In a separate analysis, men with high PTCs were significantly more likely to meet criteria for current alcohol dependence than men with low PTCs both before, OR = 2.52, 95% CI [1.33, 4.76], and after controlling for PTSD diagnosis, OR= 2.19, 95% CI [1.13, 4.22]. Thus, men with high PTCs were significantly more likely to meet criteria for current alcohol dependence than those with low PTCs, even when controlling for PTSD diagnosis.

As previously noted, we used the PROCESS procedure (Hayes, 2012) to estimate standardized regression coefficients for each indirect path from PTSD symptom severity to alcohol intoxication frequency through PTCs (PTCI total score and each subscale score) while controlling for demographic covariates. The ratio of each indirect to total effect was also computed (Preacher & Kelley, 2011). These analyses revealed a significant indirect effect of PTSD symptom severity on alcohol intoxication frequency through total PTCs, β= .11, boot SE = .03, 95% CI [.05, .17]. This indirect effect accounted for 64% of the total effect. An illustration of this effect is provided in Figure 1. Regarding the subscales of the PTCI, results indicated a significant indirect effect of PTSD symptom severity on alcohol intoxication frequency through both PTCs about the self, β= .10, boot SE = .03, 95% CI [.05, .16], and the world, β= .05, boot SE = .02, 95% CI [.02, .09], which accounted for 74% and 35% of the total effect, respectively. No significant indirect effect was noted through PTCs related to self-blame, β= .01, boot SE = .01, 95% CI [−.01, .03], indirect-to-total effect ratio = 0.04.

The confirmatory analyses using negative binomial regression supported the mediation findings reported above. Following the Baron and Kenny (1986) approach to mediation, when both PTSD symptom severity and total PTCs were examined simultaneously, PTCs remained significantly related to intoxication frequency, b = 0.01, SE = .004, Wald χ2(1, N = 278) = 9.17, p = .002, whereas PTSD symptoms did not, b = 0.003, SE = .006, Wald χ2(1, N = 278) = 0.26, p = .611.

Discussion

The present study was among the first, to our knowledge, to directly examine PTSD symptom severity and PTCs as correlates of alcohol use in MSM who experienced sexual abuse as children or adolescents. Additionally, it was one of the first to examine the indirect effects of PTSD symptom severity on alcohol use through negative PTCs. Overall, the results supported the study hypotheses. A higher level of PTSD symptom severity was linked to more frequent consumption of alcohol to intoxication after we controlled for demographic covariates. In addition, a higher level of negative PTCs about one’s self and the world were each found to be associated with more frequent alcohol intoxication even after additional control for PTSD symptoms. In fact, men who reported elevated PTCs faced over two times the odds, OR = 2.19, of meeting criteria for current alcohol dependence compared with men reporting low PTCs even after accounting for current PTSD diagnosis. Furthermore, PTSD symptom severity was indirectly associated with more frequent alcohol intoxication behavior through two types of negative PTCs: those pertaining to one’s self and those pertaining to beliefs about the world.

Our finding that a higher level of PTSD symptom severity was associated with more frequent current alcohol intoxication adds to a large body of literature linking posttraumatic sequelae with alcohol use across non-MSM populations (e.g., Debell et al., 2014; Jakupcak et al., 2010; Stewart et al., 1999). However, given the paucity of empirical inquiries into this association among sexual minority men, the present report offers an important and necessary contribution to the literature. Furthermore, this finding compliments previous reports linking the experience of CSA with alcohol misuse in MSM (Marshall et al., 2015; Mimiaga et al., 2009; Stall et al., 2001). In particular, our findings raise the question of whether the development of PTSD symptoms and negative PTCs might help to explain why MSM with CSA histories are more likely to develop severe drinking trajectories than MSM without a history of CSA (Marshall et al., 2015).

Overall, the results of this study implicate negative PTCs about one’s self and the world as particularly important factors to alcohol use in sexually risky MSM with a CSA history, as they each contributed unique variance to intoxication behavior above PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, these cognitions provided indirect paths from higher levels of PTSD symptom severity to more frequent alcohol intoxication. These negative PTCs were also associated with clinical diagnosis such that the odds for meeting criteria for current alcohol dependence were over two times greater among men with elevated PTCs than those with low PTCs, both before, OR = 2.52, and after accounting for PTSD diagnosis, OR = 2.19. Altogether, these findings suggest that the association between PTSD and alcohol use, which has been well-documented in the literature, may operate, in part, through elevations in negative PTCs.

We could not find any prior studies in the trauma literature that examined negative PTCs as a correlate of alcohol use frequency; however, as noted earlier in this article, there have been a handful of reports linking PTCs with other alcohol-related variables. Jayawickreme and colleagues (2012) found that negative PTCs about one’s self, the world, and self-blame were each significantly associated with more intense alcohol cravings among men with comorbid PTSD and alcohol dependence; however, only PTCs about one’s self remained significant after controlling for PTSD symptoms. Allwood and colleagues (2014) reported that negative PTCs about one’s self moderated the positive association between PTSD diagnosis and alcohol use disorder symptoms in psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. Our findings are congruent with this sparse body of literature and indicate that negative PTCs involving an individual’s self-perception are a particularly important correlate of alcohol misuse in sexually abused MSM as well. Moreover, our findings also offer a novel contribution to the literature by demonstrating that cognitions reflecting an individual’s posttraumatic view of the world as dangerous and unforgiving are also relevant to understanding alcohol use behavior.

In contrast to the findings reported by Allwood et al. (2014), we found evidence for the conceptualization of PTCs as a mediator of the association between PTSD and alcohol use based on self-medication theory, although we acknowledge that longitudinalinvestigationisnecessarytodefinitivelytestformediation. In light of Allwood and colleagues’ (2014) findings and in order to be comprehensive, we ran a post hoc moderator analysis. We found that PTCs did not significantly moderate the association between PTSD symptom severity and alcohol intoxication: total PTCs interaction, b = 0.003, t(270) = 0.99, p = .324, ΔR2 interaction = .003; self PTCs interaction, b = 0.012, t(270) = 1.65, p = .101, R2 interaction = .009; world PTCs interaction, b = 0.011, t(270) = 1.53, p = .129, R2 interaction = .008. Thus, we did not find evidence for the conceptualization of PTCs as a moderator in our data. It is important to point out several differences between our study and the study by Allwood et al. (2014): the sample used in their study consisted of hospitalized adolescents whereas ours consisted of MSM with a CSA history, and they examined PTSD diagnosis rather than a continuous measure of PTSD symptomology and symptoms of alcohol use disorders rather than a measure of alcohol use frequency.

The indirect effects identified in the present study suggest it may be reasonable to hypothesize that individuals with elevated PTSD symptom severity develop more rigid, emotionally distressing negative PTCs about the self and world, and in turn, drink to intoxication more frequently to mollify their distress. As put forth by Foa et al. (1999), individuals who appraise their trauma as central to their identities and worldview, versus those who perceive it as an unfortunate and aberrant occurrence, are at elevated risk for developing persistent symptoms of PTSD. In turn, continued maladaptive appraisals of posttraumatic symptomology and the meaning of the trauma can further reinforce self-deprecating beliefs and distorted perceptions of the world. Our data support this notion and furthermore suggest that negative PTCs may seed the ground for self-medication behavior with alcohol. Specifically, negative PTCs are paired with intense, poorly regulated negative emotional states characterized by anxiety, shame, and/or anger (Foa et al., 1999). Consequently, individuals who develop elevated negative PTCs often respond with dysfunctional behaviors, such as frequent intoxication with alcohol, which may temporarily relieve emotional distress but impede the integration of disconfirmatory evidence against these negative reappraisals that is necessary for cognitive change (Ehlers & Clark, 2000).

Thus, it is possible that some individuals self-medicate with alcohol against negative emotional states inherently tethered to negative PTCs rather than the classic PTSD symptoms alone. Indeed, this interpretation of our data is supported by studies that have suggested individuals with PTSD crave or use alcohol in response to trauma-cued negative emotions (Coffey et al., 2006; O’Hare & Sherrer, 2011; Waldrop, Back, Verduin, & Brady, 2007), a finding that appears to be stronger in men than women (Chaplin, Hong, Bergquist, & Sinha, 2008; Hruska & Delahanty, 2012; Lehavot et al., 2014; Sonne, Back, Zuniga, Randall, & Brady, 2003). Alternatively, it may be that a third factor, common to the etiologies of both PTSD symptoms and PTCs, better accounts for alcohol use to intoxication. Examples include neuroendocrinological dysfunction, genetic predispositions, social factors, or socioeconomic vulnerabilities.

Our findings are consistent with the traditional self-medication hypothesis (Khantzian, 1997), which posits that traumatized individuals may consume alcohol to intoxication in an attempt to relieve distressing PTSD symptoms. Our findings offer a contribution to this model by emphasizing a role for emotionally distressing posttraumatic cognitive schema. Specifically, our data suggest that persistent, negatively valenced self-perceptions and beliefs about the safety of the world may be triggers for self-medication with alcohol. Negative PTCs have not typically been examined or specified within self-medication models of PTSD, likely because DSM-IV-TR (or older) criteria did not specify them within a PTSD symptom cluster (APA, 2000). Interestingly, the PTSD criteria were revised in the fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5; APA, 2014) to include negative alterations to cognitions and emotions as a new symptom cluster. Our findings support the addition of this new symptom cluster and suggest that it may be a particularly important target for self-medication with alcohol independent from the other clusters combined. On the other hand, our findings highlight the clinical importance of considering negative PTCs separately from the other symptoms when evaluating risk for self-medication with alcohol. The hypotheses for the present study were formulated based on the DSM-IV-TR criteria (the most updated at the time), which facilitated our conceptualization of them as a potential mediator of the association between PTSD and alcohol use because they were a separate construct from PTSD symptoms. Under the DSM-5 criteria, conceptualizing PTCs as part of a PTSD symptom cluster may discourage the examination of PTCs as a unique driver of self-medication or other maladaptive coping behaviors because they are less likely to be separated out in longitudinal analyses. Based on our data, we would expect future studies using a DSM-5 PTSD measure to find that total PTSD symptoms account for a larger proportion of variance in alcohol than they would if a DSM-IV-TR measure was used given its inclusion of negative PTCs. However, our data suggest that it may be beneficial for future studies to separately examine each symptom cluster in order to further elucidate their relative contributions to alcohol use behavior.

There are several broader implications of our findings. First, our findings suggest that MSM survivors of CSA with elevated PTCs are at elevated risk for experiencing clinical problems with alcohol; thus, it may be prudent for clinicians to look beyond PTSD (total symptoms or diagnosis) alone and carefully consider the extent of posttraumatic cognitions when assessing risk for problematic alcohol use in this population. This is especially important given that alcohol misuse is associated with negative health outcomes (Room, Babor, & Rehm, 2005) and may also interfere with PTSD treatment (Riggs, Rukstalis, Volpicelli, Kalmanson, & Foa, 2003). Second, evidence-based interventions specifically targeting negative PTCs, such as cognitive processing therapy (Resick & Schnicke, 1992) and cognitive behavioral therapies for PTSD (Foa & Rothbaum, 2001), may potentially have an impact upon alcohol intoxication behaviors in these trauma survivors.

The evidence presented in the current report of co-occurring elevations in PTSD symptom severity, negative PTCs, alcohol intoxication, and propensity for alcohol dependence among traumatized sexual minority men has implications for treatment development priorities. Trauma histories (O’Cleirigh & Safren, 2008; O’Cleirigh, Safren, & Mayer, 2012) and alcohol use disorders (see Green & Feinstein, 2012, for review) are each pathways to higher rates of sexual risk for HIV acquisition among gay and bisexual men, the group at highest risk for HIV domestically. The development of integrated treatment platforms with the flexibility to address the underlying trauma and alcohol use disturbances by targeting posttraumatic cognitions within the context of sexual health counseling may well reap the dual benefits of improving the mental health of gay and bisexual men but also offset new HIV infections in this vulnerable group.

Future longitudinal studies are needed to expand upon the present findings in order to determine whether changes in negative PTCs mediate the association between PTSD symptomology and the development of problematic alcohol use patterns. This may include investigating whether incorporating cognitive reappraisal components into tradition alcohol misuse treatment may support the maintenance of larger treatment effects. Future researchers may also seek to validate the relevance of negative PTCs to alcohol intoxication habits in larger, more diverse, nationally representative samples of individuals with traumatic histories. Finally, future investigators may seek to examine whether PTCs might play a role in non-alcohol-related substance use (e.g., methamphetamine and cocaine), which is also elevated among MSM (Stall et al., 2001).

The findings reported herein should be interpreted with a consideration of the limitations of the study design. Foremost, this study utilized a cross-sectional design, which prohibits drawing definitive conclusions about causality or the directionality of the association between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use frequency. For instance, it is possible that frequent alcohol intoxication contributed to the development of more elevated PTCs and PTSD symptoms, and reciprocal associations among these constructs should not be ruled out. It may be reasonable, however, to conclude that PTSD symptoms emerged prior to the development of intoxication behavior considering that all participantsexperiencedCSApriorto17yearsofage.Additionally, this study relied on self-reports of alcohol use frequency, PTSD symptomology, and PTCs; as such, the present findings are vulnerable to the biases associated with that methodology. Finally, we had an ethnically diverse but specialized sample composed exclusively of sexually risky MSM with a CSA history. Thus, our findings may not generalize to MSM without these characteristics. However, it is worth recalling that the occurrence of CSA is common and disproportionately high among MSM (Sweet & Welles, 2012). Additionally, although our findings may not generalize to the broader MSM population, our sample represents a group of MSM with a pronounced risk profile for both HIV seroconversion and alcohol misuse. Thus, despite their limited generalizability, our findings may be both relevant for a high proportion of MSM and have wide-ranging and meaningful clinical and public health implications.

This study was among the first to show that higher levels of negative posttraumatic cognitions (PTCs) about the self and the world were each uniquely associated with more frequent alcohol intoxication over and above PTSD symptoms and that these cognitions mediated the association between PTSD and alcohol use. Our sample comprised MSM with a CSA history, which is a population whose vulnerability to negative mental health outcomes is exacerbated by alcohol use (Irwin, Morgenstern, Parsons, Wainberg, & Labouvie, 2006; Kalichman, Simbayi, Kaufman, Cain, & Jooste, 2007; Koblin et al., 2006). Continued work in this area may have important public health implications by informing the development and application of treatments aimed at addressing the disproportionately high rates of trauma-related distress and alcohol use disorders among MSM. Furthermore, given that MSM with CSA histories (Mimiaga et al., 2009) or alcohol use disorders (Paul et al., 2001) are at elevated risk for HIV seroconversion under the influence of alcohol, this work may be fruitful in advancing primary prevention efforts to reduce rates of HIV.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH095624, PI: Dr. O’Cleirigh). Subcontract for Miami site (PI: Dr. G. Ironson). Some of the author time (Safren) was supported by the NIH (9K24DA040489). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Allwood MA, Esposito-Smythers C, Swenson LP, & Spirito A (2014). Negative cognitions as a moderator in the relationship between PTSD and substance use in a psychiatrically hospitalized adolescent sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27, 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alterman AI, McDermott PA, Cook TG, Metzger D, Rutherford MJ, Cacciola JS, & Brown LS Jr. (1998). New scales to assess change in the Addiction Severity Index for the opioid, cocaine, and alcohol dependent. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 12, 233–246. http://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.12.4.233 [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroughs MS, Valentine SE, Ironson GH, Shipherd JC, Safren SA, Taylor SW, . . . O’Cleirigh C (2015). Complexity of childhood sexual abuse: predictors of current post-traumatic stress disorder, mood disorders, substance use, and sexual risk behavior among adult men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 1891–1902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0546-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Darnell A, & Charney DS (1996). Chronic PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans: Course of illness and substance abuse. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 153, 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.153.3.369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Lin Y-T, & Lynch KG (2007). Initial evidence for the reliability and validity of a “Lite” version of the Addiction Severity Index. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 87, 297–302. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Hong K, Bergquist K, & Sinha R (2008). Gender differences in response to emotional stress: An assessment across subjective, behavioral, and physiological domains and relations to alcohol craving. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32, 1242–1250. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00679.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcoat HD, & Breslau N (1998). Investigations of causal pathways between PTSD and drug use disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 23, 827–840. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00069-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Stasiewicz PR, Hughes PM, & Brimo ML (2006). Trauma-focused imaginal exposure for individuals with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence: Revealing mechanisms of alcohol craving in a cue reactivity paradigm. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20, 425–435. http://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish T (2004). Cognitive approaches to posttraumatic stress disorder: The evolution of multirepresentational theorizing. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 228–260. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR, Book S, Colket J, Tupler L, Roth S, David D, . . . Smith R (1997). Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine, 27, 153–160. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291796004229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, Batt-Rawden S, Greenberg N, Wessely S, & Goodwin L (2014). A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49, 1401–1425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0855-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal C, Carballo-Dieguez A, Nieves-Rosa L, & Díaz F (2000). Substance use and sexual risk behavior: Understanding their association among four ethnic groups of Latino men who have sex with men. Journal of Substance Abuse, 11, 323–336. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00030-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll LS, Joy D, Bartholow BN, Harrison JS, Bolan G, Douglas JM, . . . Delgado W (1992). Self-reported childhood and adolescent sexual abuse among adult homosexual and bisexual men. Child Abuse and Neglect, 16, 855–864. http://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(92)90087-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunmore E, Clark DM, & Ehlers A (2001). A prospective investigation of the role of cognitive factors in persistent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after physical or sexual assault. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39, 1063–1084. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00088-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, & Clark DM (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 319–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams J (1997). Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-IV). New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, & Rothbaum BO (2001). Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Ehlers A, Clark DM, Tolin DF, & Orsillo SM (1999). The posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI): Development and validation. Psychological Assessment, 11, 303–314. http://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.11.3.303 [Google Scholar]

- Green KE, & Feinstein BA (2012). Substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: An update on empirical research and implications for treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 265–278. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0025424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzler B, Donovan DM, & Huang Z (2011). Rates and influences of alcohol use disorder comorbidity among primary stimulant misusing treatment-seekers: Meta-analytic findings across eight NIDA CTN trials. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse, 37, 460–471. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2011.602995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

- Hruska B, & Delahanty DL (2012). Application of the stressor vulnerability model to understanding posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcohol-related problems in an undergraduate population. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 734–746. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin TW, Morgenstern J, Parsons JT, Wainberg M, & Labouvie E (2006). Alcohol and sexual HIV risk behavior among problem drinking men who have sex with men: An event level analysis of timeline followback data. AIDS and Behavior, 10, 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-005-9045-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Tull MT, McDermott MJ, Kaysen D, Hunt S, & Simpson T (2010). PTSD symptom clusters in relationship to alcohol misuse among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans seeking post-deployment VA health care. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 840–843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayawickreme N, Yasinski C, Williams M, & Foa EB (2012). Gender-specific associations between trauma cognitions, alcohol cravings, and alcohol-related consequences in individuals with comorbid PTSD and alcohol dependence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, & Jooste S (2007). Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review of empirical findings. Prevention Science, 8, 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, & Nelson CB (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 1048–1060. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ (1997). The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4, 231–244. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229709030550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, & Best CL (2003). Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 692–700. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Husnik MJ, Colfax G, Huang Y, Madison M, Mayer K, . . . Buchbinder S (2006). Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS, 20, 731–739. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, Stappenbeck CA, Luterek JA, Kaysen D, & Simpson TL (2014). Gender differences in relationships among PTSD severity, drinking motives, and alcohol use in a comorbid alcohol dependence and PTSD sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28, 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenderking WR, Wold C, Mayer KH, Goldstein R, Losina E, & Seage GR (1997). Childhood sexual abuse among homosexual men. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 12, 250–253. Retrieved from http://www.jgim.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BL, Shoveller JA, Kahler CW, Koblin BA, Mayer KH, Mimiaga MJ, & . . . Operario D (2015). Heavy drinking trajectories among men who have sex with men: A longitudinal, group-based analysis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39, 380–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC (1998). Epidemiological evidence about the relationship between PTSD and alcohol abuse: The nature of the association. Addictive Behaviors, 23, 813–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00098-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Noonan E, Donnell D, Safren SA, Koenen KC, Gortmaker S, . . . Koblin BA (2009). Childhood sexual abuse is highly associated with HIV risk–taking behavior and infection among MSM in the EXPLORE study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 51, 340–348. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Gotthardt S, Weiss RD, & Epstein M (2004). Cognitive distortions in the dual diagnosis of PTSD and substance use disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28, 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:COTR.0000021537.18501.66 [Google Scholar]

- O’Cleirigh C, & Safren S (2008). Optimizing the effects of stress management interventions in HIV. Health Psychology, 27(3), 297–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Cleirigh C, Safren SA, & Mayer KH (2012). The pervasive effects of childhood sexual abuse: Challenges for improving HIV prevention and treatment interventions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 59, 331–334. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824aed80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hare T, & Sherrer M (2011). Drinking motives as mediators between PTSD symptom severity and alcohol consumption in persons with severe mental illnesses. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 465–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JP, Catania J, Pollack L, & Stall R (2001). Understanding childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of sexual risk-taking among men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health Study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25, 557–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00226-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ,&Kelley K(2011).Effectsizemeasuresformediationmodels: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods, 16, 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Bland S, Skeer M, Cranston K, Isenberg D, . . . Mayer KH (2010).Problematic alcohol use and HIV risk among Black men who have sex with men in Massachusetts. AIDS Care, 22, 577–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120903311482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, & Schnicke MK (1992). Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 748–756. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.60.5.748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DS, Rukstalis M, Volpicelli JR, Kalmanson D, & Foa EB (2003). Demographic and social adjustment characteristics of patients with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence: Potential pitfalls to PTSD treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 28, 1717–1730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R,Babor T,&Rehm J(2005).Alcoholandpublichealth.TheLancet, 365, 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17870-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, . . . Dunbar GC (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal Of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Suppl 20), 22–33. Retreived from http://www.psychiatrist.com/jcp/Pages/home.aspx [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonne SC, Back SE, Zuniga CD, Randall CL, & Brady KT (2003). Gender differences in individuals with comorbid alcohol dependence and post-traumatic stress disorder. The American Journal on Addictions, 12, 412–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550490390240783 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Paul JP, Greenwood G, Pollack LM, Bein E, Crosby GM, . . . Catania JA (2001). Alcohol use, drug use and alcohol-related problems among men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health Study. Addiction, 96, 1589–1601. https://doi.org/10.1080/09652140120080723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Conrod PJ, Pihl RO, & Dongier M (1999). Relations between posttraumatic stress symptom dimensions and substance dependence in a community-recruited sample of substance-abusing women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 13, 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893164X.13.2.78 [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014). Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Author; SDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4863. Retreived from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet T, & Welles SL (2012). Associations of sexual identity or samesex behaviors with history of childhood sexual abuse and HIV/STI risk in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 59, 400–408. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182400e75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop AE, Back SE, Verduin ML, & Brady KT (2007). Triggers for cocaine and alcohol use in the presence and absence of posttraumatic stress disorder. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 634–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]