Abstract

Objectives:

This work examines the clinical utility of the scoring system for the Lichtenberg Financial Decision-making Rating Scale (LFDRS) and its usefulness for decision making capacity and financial exploitation. Objective 1 was to examine the clinical utility of a person centered, empirically supported, financial decision making scale. Objective 2 was to determine whether the risk-scoring system created for this rating scale is sufficiently accurate for the use of cutoff scores in cases of decisional capacity and cases of suspected financial exploitation. Objective 3 was to examine whether cognitive decline and decisional impairment predicted suspected financial exploitation.

Methods:

Two hundred independently living, non-demented community-dwelling older adults comprised the sample. Participants completed the rating scale and other cognitive measures.

Results:

Receiver operating characteristic curves were in the good to excellent range for decisional capacity scoring, and in the fair to good range for financial exploitation.

Conclusions:

Analyses supported the conceptual link between decision making deficits and risk for exploitation, and supported the use of the risk-scoring system in a community-based population.

Clinical Implications:

This study adds to the empirical evidence supporting the use of the rating scale as a clinical tool assessing risk for financial decisional impairment and/or financial exploitation.

Keywords: Cognitive decline, financial decision making, financial exploitation, person centered

Introduction

Lichtenberg and colleagues (2017a) presented factor analysis and convergent validity data in providing empirical support for the person-centered Lichtenberg Financial Decision Rating Scale (LFDRS). The results supported the conceptual model for the scale; including contextual and intellectual factors. Further, the scale demonstrated convergent validity with measures of cognition and money management skills. The scale is a 68-item multiple-choice instrument with a combination of rater items and self-report items. A risk score is derived from the scale’s scoring system. How useful is this risk score in clinical settings? Core to the LFDRS are the 10 items also used in the screening scale, the Lichtenberg Financial Decision Screening Scale, which has been found to be clinically useful in cases of financial exploitation as determined by Adult Protective Services worker (Lichtenberg, Teresi, Ocepek-Welikson, & Eimick, 2017b). The screening scale, however, does not assess any contextual factors and thus gives limited information in understanding financial decision making. Specifically, the LFDRS allows the clinician to understand the personal context of the person making the decision. This includes financial awareness—how much financial strain and self-efficacy is the older adult experiencing as well as how much assistance she may be giving to others. Contextual variables include questions about psychological vulnerability around finances (e.g., loneliness, anxiety, and depression) and susceptibility such as conflict or strain with others around finances and expenditures. The purpose of this study is to investigate how well the risk scoring system can predict financial decision making incapacity and financial exploitation, and to ascertain whether cognitive decline interacts with decision making to make older adults even more vulnerable to exploitation.

Financial Capacity, Decision-making and Exploitation

The links between impaired financial decision-making and financial exploitation have been explored in three major ways. First, the impact of neurocognitive disorders on financial capacity across a variety of domains (including decision-making) has been examined (Marson, 2016), and clear evidence has been found for the profound impact of dementia on financial capacity (and by extension financial exploitation). Second, financial decision-making has been studied more explicitly; its links to neurocognitive tests and brain functioning have been detailed, along with the relationships between decision-making and a measure of scam susceptibility (Boyle, Wilson, Yu, Buchman, & Bennett, 2012; Han et al., 2015; Spreng, Karlawish, & Marson, 2016). Third, and more recently, the integration of psychological variables with cognitive variables has been described (Lichtenberg et al., 2017a; Lichtenberg, Stoltman, Ficker, Iris, & Mast, 2015; Spreng et al., 2016). Spreng and colleagues (2016) draw on normative aging and decision-making research to highlight the potential role of trust, positivity bias, and deception in financial exploitation. Their new model highlights the roles of social, psychological, neural, and financial management abilities in both decision-making and exploitation risk. The biggest change in this model is the incorporation of psychological and social phenomena from the normal aging literature. Thus, they argue that as a consequence of aging, older adults are more trusting, more easily deceived, and less attentive to the potential negative characteristics of others, all of which lead to a higher risk for exploitation.

In contrast, our research has drawn on clinical conditions and exaggerated vulnerabilities in incorporating psychological variables into our model. In two studies of the effects of psychological vulnerability and susceptibility on influence in cases of suspected financial exploitation (Lichtenberg, Stickney, & Paulson, 2013; Lichtenberg, Sugarman, Paulson, Ficker, & Rahman-Filipiak, 2016a), we focused on non-normative aging experiences (e.g., anxiety, depression, low sense of social status and sense of financial mastery and security) and found that more extreme psychological vulnerability led to higher rates of fraud victimization, in both cross-sectional and longitudinal samples.

Gaps in Financial Exploitation Research

As research on the financial exploitation of older adults expands, important areas of assessment are being identified. At the same time, however, gaps in our knowledge persist. For example, Wong and Waite (2017) found that financial mistreatment is related to later loneliness and decreased physical health in a 5-year follow-up of a random sample of 2,261 older adults in the National Social Life Health and Aging Project. Acierno, Hernandez-Tejada, Antetzberger, Loew, and Muzzy (2017) conducted an 8-year follow-up with 183 victims of elder mistreatment and 591 non-victims from the National Elder Mistreatment Study, and obtained results similar to those of Wong and Waite—until the mediating impact of social support was measured. Social support was highly protective of elder mistreatment victims, including against excess anxiety and poor health. Other recent research has focused on social contexts that influence exploitation. Quinn, Nerenberg, Navarro, and Wilber (2017) highlighted diverse ways in which vulnerabilities impact the risk for being unduly influenced, whereas Ruffman, Murray, Halberstadt, and Vater (2012) found that older adults are worse than younger adults in detecting lies, due to changes in emotion recognition. Finally, Spreng and colleagues (2016) have demonstrated the interaction of brain and cognition changes with social contexts and the assessment of financial skills (e.g., the Financial Capacity Inventory) and financial decision-making (e.g., the Assessing Competency in Everyday Decisions [ACED] Test); deficits in these areas are postulated to increase risk for financial exploitation. Even so, Spreng and colleagues concluded that a tremendous gap persists in our knowledge of how to identify exploitation risk in the real world, and especially in community samples. Further review of the financial exploitation and capacity literature can be found in (Acierno et al., 2017; Lichtenberg et al., 2015, 2016b, 2017a; and Spreng et al., 2016).

The Rush University research group (Boyle et al., 2012; Boyle, Wilson, Yu, Buchman, & Bennett, 2013; Han et al., 2015) has contributed greatly to the literature on financial decision-making and scam susceptibility, which is one form of financial exploitation. The studies cited above not only link financial decision-making declines to reduced cognition, even without dementia, but also link brain regions and decision-making findings to scam susceptibility. Nevertheless, without analyzing data for real-world decisions and/or suspected cases of actual scams or other forms of financial exploitation, we cannot determine how sensitive or specific the assessments would be in clinical practice.

Financial Decision-making, Cognition, and Capacity

Community-based research clearly shows the links between declining cognition and impaired financial capacity across a variety of real-world and experimental task domains. For instance, Belbase and Sanzenbacher (2017) provide support for a decline in financial capacity with the onset of dementia. Using data from a variety of sources, including the Health and Retirement Survey, they found that adults in their 70s and 80s are just as likely to be able to pay bills, manage debt, and maintain good credit as are those in their 50s and 60s. The authors note, however, the impact of cognitive impairment on these financial abilities: 95% of older adults with no cognitive impairment could manage their finances well, while only 82% of those with mild cognitive impairment— and a scant 20% of those with dementia—could do so. Marson (2016) reviewed his clinical model of financial capacity and its interaction with cognition across nearly 20 years of research using his Financial Capacity Instrument, and highlighted how even early symptoms of neurocognitive disorders affected financial capacity. Neither of these studies, however, examined financial exploitation, and both were based on minimal data on financial decision-making.

Boyle and colleagues in the Rush University Memory and Aging Project (Boyle et al., 2012, 2013; and Han et al., 2015) examined financial decision-making and cognition longitudinally and found, in a sample of more than 400 older adults (Boyle et al., 2012) that even modest cognitive decline (i.e., outside the range of actual cognitive impairment) is related to a decline in financial decision-making ability. The authors provide evidence that cognitive functioning and decision-making can be independent, though related, constructs. In a subsequent study, Boyle and colleagues (2013) found that older persons without dementia—but with decision-making deficits—experienced a fourfold increase in mortality across a 4-year follow-up. In addition, they found that reduced financial decision-making was related to increased susceptibility to scams. Han and colleagues (2015) tested the discrepancy between cognition and decision-making in a sample of 689 older adults and found that in 13% of cases, decision-making scores were more than 1 z score below cognition; in 11% of cases, cognition scores were lower than decision-making scores.

Lichtenberg Financial Decision-making Rating Scale

Using a concept-mapping method, we developed a new person-centered rating scale and accompanying conceptual model: the Lichtenberg Financial Decision-making Rating Scale (LFDRS; Lichtenberg, Ficker, & Rahman-Filipiak, 2016c; Lichtenberg et al., 2015). These studies also provided preliminary inter-rater reliability and convergent validity. More recently, in a sample of 200 independent community-dwelling adults, we used factor analysis to test the conceptual model and found support for three contextual factors and an intellectual factor (Lichtenberg et al., 2017a). The contextual factors used assess issues related to financial awareness (e.g. self-efficacy, strain, and knowledge); psychological vulnerability with regard to finances; and susceptibility to influence or exploitation due to social vulnerabilities. The intellectual factors used were identified 30 years ago by Appelbaum and Grisso (1988): communication of choice, understanding, appreciation, and reasoning.

The LFDRS is unique, in that it consists of multiple-choice questions and ratings that yield a quantified risk score. The score has been shown to be related to both financial management skills and neurocognitive variables, but is not redundant to either. In this study, we examine the clinical utility of cutoff scores for the LFDRS, as well as how useful they are for determining risk of impaired financial decision-making capacity and/or financial exploitation. Finally, we examine whether the combination of cognitive decline and impaired decisional abilities places older adults at increased risk for financial exploitation.

The Intersection of Financial Decision-making Abilities and Financial Exploitation

A man with early dementia is taken to the bank by his brother, and before he leaves the bank he pays the remainder of his brother’s home mortgage of more than $100,000. A successful retired businessman with executive dysfunction difficulties, alone and lonely, loses nearly $1 million in a scam in which he is convinced that a woman he has never met loves him, and that she needs to marry him and bring him to Italy in order to receive a $20 million inheritance. These two cases illustrate how financial decision-making and financial exploitation are linked. But what happens when we attempt to quantify risk for impaired financial decisional ability and financial exploitation? Is the linkage strong enough to be useful in real-life settings? In previous work, we investigated this question using cases of potential exploitation provided by Adult Protective Services and legal and financial advisors (Lichtenberg et al., 2016b). Both older adults with decisional incapacity and those with substantiated financial exploitation had higher risk scores on the Lichtenberg Financial Decision Screening Scale (LFDSS), a multiple-choice rating scale based on Appelbaum and Grisso (1988) model. These results provided support for the idea that financial decision-making abilities and risk for financial exploitation can be quantified. In our more recent study of the LFDSS (Lichtenberg et al., 2017b), using an expanded sample, we provided clinical utility data for the 10-item screening scale.

Two questions form the basis for this study: Does a similar pattern hold true for the more contextualized LFDRS? And is risk scoring useful in community-based, nonclinical samples?

Importance of Assessing Risk in Community-based Samples

In reviewing their own data and the related literature, Acierno and colleagues (2017) state that sampling from the community is important, since few cases of elder abuse are reported to the authorities, yet are acknowledged upon interview. Spreng and colleagues (2016) highlight the importance of finding ways to assess real-world decision-making in at-risk populations. Given the hidden nature of financial exploitation, it is important to assess financial decision-making and exploitation in a sample of non-demented, community-dwelling older adults with varying degrees of education and wealth. As Pillemer, Connolly, Breckman, Spreng, and Lachs (2015) stated during the White House Conference on Aging, it is vital that financial decision-making and exploitation be assessed in samples that include both older adults who have been exploited and those who have not.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the clinical utility of the LFDRS risk-scoring system, with the following hypotheses:

-

(1)

Participants rated as having financial decisional-ability impairments will have higher LFDRS risk scores, such that receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve values will be .80 or above.

-

(2)

Participants rated as having been financially exploited will have higher LFDRS risk scores, such that ROC curve values will be .80 or above.

-

(3)

Participants determined to have experienced possible cognitive decline and decisional ability impairment will be significantly more likely to have been financially exploited than those with no cognitive decline and/or intact decisional abilities.

Methods

Procedures for Developing the LFDRS

The LFDRS, which was created to offer an alternative measure for financial capacity assessment, measures decision-making based on actual financial decisions and/or transactions. More complete details on development of the model and scale can be found in Lichtenberg and colleagues (2015). Briefly, while we began with a decisional abilities framework, we used the concept-mapping method of brainstorming to expand the conceptual framework and finalize an initial set of items. Inter-rater reliability results for overall ratings on the scale were satisfactory; at that time, the complete rating scale contained 77 items. After preliminary analyses (Lichtenberg et al., 2016c), the scale was shortened to 68 items (56 items for all participants and 12 additional items with skip patterns).

Participant Recruitment Procedures

Inclusion criteria were being age 60 or older, living independently in the community, reporting the ability to be independent in independent activities of daily life and activities of daily life, being a native English speaker, and having the ability to do some basic word reading. After receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board, three methods were used to recruit participants. First, more than 100 participants were directly recruited from the Healthier Black Elders Participant Registry, which is part of the University of Michigan–Wayne State University NIA P30 Resource Center for Minority Aging Research. This required additional approval from the Healthier Black Elders Community Advisory Board (see Hall et al., 2016, for details on recruitment and retention of registry members). Second, the first author gave a number of presentations to groups of older adults across a wide variety of locations and settings (e.g., senior centers, churches, independent living centers), and participants were recruited at these events. And third, a snowballing technique was used.

When older adults were approached to participate in the study, either by phone or in person, they were asked to participate in an interview and testing session that would last approximately 2 hours. Financial decisions were considered significant if they fell into one of the following categories: (a) investment planning (retirement, insurance, portfolio balancing); (b) estate planning (changes in a will or beneficiaries, allowing someone access to a bank/investment account); (c) major purchase (home, car, renovations, etc.); or (d) giving a gift.

Participants

Two hundred independent, community-living adults age 60 and older comprised the sample. Fifty-two percent were African American, and 74% were women. The significant financial decisions being made were predominantly major purchases or sales and investment and estate planning.

Lichtenberg Financial Decision-making Rating Scale

Scores indicative of risk for decisional ability deficits are calculated for each item and for the total scale. Of the 68 total items, risk scores for 53 items are obtained directly from the older adult’s self-reported answers. These items include all of the contextual variables from the three subscales: Financial Situational Awareness, Psychological Vulnerability, and Susceptibility to Undue Influence and to Financial Exploitation. The fourth subscale, for the intellectual factor, is a rating scale that employs both self-report and rater responses: Participants give a self-reported answer to each question, and the rater marks the answer he or she believes to be most accurate; risk scores are accentuated when there is a discrepancy between the older adult’s report and the rater’s report. Risk scores for the contextual variables and each subscale are then added to the risk score for the intellectual factor.

Decisional Ability Impairment

Similar to the procedures employed to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease, we used a consensus conference to determine whether decisional ability deficits were present in individual participants. While all three coauthors had access to the LFDRS answers, no risk scores had been calculated before the consensus conference yielded a decision on each case. The decision-making process was based on instructions for the LFDRS, which state: “For the intellectual factor items, were there any discrepancies between the rater’s choice and the older adult’s response? Any discrepancies should raise concerns about the older adult’s decisional abilities. Did there appear to be a lot of psychological vulnerability and susceptibility or a high level of financial strain? These factors influence a final rating as well.” A final dichotomous rating of some/major concerns or no concerns was assigned (1 = decisional ability impairment, 2 = intact decisional abilities). The consensus conference added to the test administration by insuring that cases in which discrepancies were more likely due to a lack of understanding the question, or were of such a minor nature that decision making was intact, were recognized.

Suspected Financial Exploitation

Suspected financial exploitation was defined as the illegal or improper use of an elder’s funds, property, or assets by either someone known to the victim or a stranger (Conrad, Iris, Ridings, Langley, & Wilber, 2010), and included theft and scams. Questions on the LFDRS trigger responses that reveal financial exploitation, such as whether the person had recently made a financial decision they regretted or worried about, whether they were currently helping someone regularly with finances and how they felt about the situation, and whether they had ever lost money as a result of a financial decision. We used follow-up questions to learn the details of any concerns about financial exploitation and a consensus conference method to identify suspected financial exploitation. Examples of such cases included paying someone in advance for work that was never performed and giving family members access to a bank account to withdraw $400, who instead withdrew $5,000 and kept the money.

All three co-authors met and reviewed each item and the description of any money loss that might be related to suspected financial exploitation. An example of what was not considered financial exploitation was purchasing a home during an auction and having to pay recording or other fees they had not realized would be added to the base price. We then rated each person as having or not having experienced financial exploitation within the previous 18 months (1 = suspected financial exploitation, 2 = no financial exploitation). Similar to most studies of exploitation we were not able to investigate or substantiate instances of exploitation by examining bank records or canceled checks. The consensus conference helped insure that only serious matters of exploitation (those which would qualify for reporting to APS) were used in assigning exploitation to a case.

Cognitive Functioning

The neuropsychological measures described below were chosen because they (1) cover the broad areas of cognitive functioning and (2) have been widely used and well validated in older adult populations, including among African Americans.

Wide Range Achievement Test 4—Reading (WRAT4)

The WRAT4 (Wilkinson & Robinson, 2006) reading subtest has been found to be an excellent measure of quality (versus only quantity) of a person’s educational experience (Schneider & Lichtenberg, 2011). The test consists of 16 letters and 54 words that are read aloud. Higher scores are related to better reading abilities.

The Rey auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT)

This 15-item word-recall test (over five trials) measures immediate and delayed memory and a learning curve, and reveals learning strategies (Lezak, 1983; Schmidt, 1996).

Trailmaking Test (TMT)

The Trailmaking Test (Reitan & Wolfson, 1985) has two parts. In Part A, older adults are timed as they connect circles in order by number; this is a test of basic visuomotor attention. A mental flexibility component is added in Part B, in which the older adult connects the circles in order, but this time while alternating between numbers and letters. Raw scores were used in the analyses, with lower scores indicating better cognitive performance. Different normative data sets produce slightly differing standard scores. To reduce potential bias of these standard score data sets we used raw scores.

The Stroop Color-Word Test (Stroop)

This is a test of disinhibition and mental flexibility (Golden, 1978). In the first part, words for colors (e.g., red, blue, green), which are printed in black ink, are read as quickly as possible; in the second part, the colors of a series of XXX markings are stated; and in the third part, color words printed in ink of a different color (e.g., “blue” printed in red ink) are presented. The total score for each trial is the number of items correctly stated in 45 seconds. Higher scores indicate better cognitive performance.

Boston Naming Test (BNT)

The purpose of this 15-item test is to assess ability to name pictured objects (Kaplan, Goodglass, & Weintraub, 1983); it is particularly sensitive to word-finding difficulties. Higher scores are related to better functioning.

Animal Naming Test

This category-naming measure of verbal fluency is highly sensitive to cognitive changes in older adults, and measures verbal executive functioning and semantic fluency (MacNeill & Lichtenberg, 1999). Higher scores are related to better cognitive functioning.

Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT)

This verbal fluency task measures the ability to generate lists of words that begin with different letters over three 60-second trials (Benton, Hamsher, Varney, & Spreen, 1983). Higher scores are related to better cognitive functioning.

Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE)

This test is a brief screening measure of global cognitive status and covers orientation, attention, memory, language, and visuospatial abilities (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975).

Data Analysis

Hypothesis 1: Financial decision-making abilities

First, the means and standard deviations for demographic and LFDRS scores will be compared for those with decisional ability impairments and those with intact decisional abilities. Second, correlational analyses will be used to examine the strength of the relationships among LFDRS total score, subtests, suspected financial exploitation, and demographic variables. To obtain an optimal cutoff point for both scales, ROC curves were created. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (ppv), negative predictive value (npv), and overall correct classification were calculated at each potential cutoff point.

Hypothesis 2: Suspected financial exploitation

Similar to the data analyses in Hypothesis 1, comparisons will be made between those suspected to have been exploited and those who have not been. Correlations, cutoff scores, and ROC curves will also be presented.

Hypothesis 3: Likelihod of financial exploitation

Participants will be classified as showing signs of possible cognitive decline if four or more of their neuropsychological test scores are 1 SD or more below the sample mean. Since older adults may score low on some tests in a battery due simply to chance, we selected this cutoff to minimize this possibility. The following 13 scores will be counted toward the classification: WRAT4 total word reading score; RAVLT total words learned over trials, immediate recall, and delayed recall; TMT A and B completion times; Stroop total scores for each trial; BNT total words; Animal Naming test total words; COWAT total words; and MMSE total score. First, the means and standard deviations for demographics and neuropsychological test scores will be compared for those classified as exhibiting possible cognitive decline. We will conduct chi-square tests to determine whether participants with possible cognitive decline and those with impaired financial decisional capacities were more likely to also report a history of suspected financial exploitation. A chi-square test will then be conducted to examine the overlap between possible cognitive decline, impaired financial decisional abilities, and history of suspected financial exploitation.

Results

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and percentages for participants judged to have decisional ability deficits and those judged to have intact decisional abilities. Overall, 8% of the sample (n = 16) displayed decisional ability deficiencies. Table 1 reveals that those with decisional ability deficits were significantly older and less educated than those with intact decisional abilities. The groups did not differ in terms of gender or race. On the LFDRS, significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of scores for overall risk and risk for each of the four subscales. Those with decisional ability deficits had significantly higher risk scores on all of the LFDRS indices than those with intact decisional abilities.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of demographics and LFDRS Total and Subscale Scores by financial decisional ability.

| Variable | Total (N = 200) | No Concerns (n = 184) | Some/Major Concerns (n = 16) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

M (SD) or % |

M (SD) or % |

M (SD) or % |

||

| Age | 71.5 (7.4) | 71.1 (7.2) | 76.1 (8.2) | .008 |

| Education (years) | 15.3 (2.6) | 15.5 (2.6) | 13.8 (2.1) | .014 |

| Race | .162 | |||

| Caucasian | 48.0% | 49.5% | 31.3% | |

| African American | 52.0% | 50.5% | 68.7% | |

| Gender (female) | 74.0% | 73.3% | 81.3% | .491 |

| LFDRS Total Score | 16.0 (8.6) | 14.8 (7.2) | 29.8 (11.9) | <.001 |

| FSA | 7.2 (3.2) | 6.9 (3.0) | 10.3 (3.3) | <.001 |

| PV | 3.1 (2.8) | 2.9 (2.6) | 5.3 (4.2) | .040 |

| Susceptibility | 3.6 (3.8) | 3.2 (3.4) | 7.9 (5.8) | .005 |

| Intellectual | 2.3 (2.0) | 1.9 (1.4) | 6.3 (3.0) | <.001 |

Note: FDA = Financial decisional abilities; LFDRS = Lichtenberg Financial Decision Rating Scale; FSA = Financial Situational Awareness; PV = Psychological Vulnerability.

p-values are reported for t-tests or chi-square tests as appropriate.

Correlational analyses presented in Table 2 show a somewhat different set of associations. The total LFDRS risk score is unrelated to any demographic variable, although the intellectual factor subscale is significantly related to age (higher risk with increased age), and the psychological vulnerability subscale is significantly related to education (lower risk with higher education). The rating for financial decisional abilities is most highly related to the intellectual subscale score (r = .61; p < .001); the next highest is the LFDRS total score (r = .47; p < .001). The other contextual subscales are also all significantly related to the financial decisional ability rating. As will be examined in more detail below, the LFDRS total score was significantly related to suspected financial exploitation.

Table 2.

LFDRS Correlations with demographic and financial exploitation data.

| Variable | Age | Gender | Education | SFE | FDA | Total Score | FSA | PV | Susceptibility | Intellectual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | |||||||||

| Gender | .109 | 1 | ||||||||

| Education | −.009 | .102 | 1 | |||||||

| SFE | −.012 | −.129 | −.086 | 1 | ||||||

| FDA | .186** | −.049 | −.174* | .342*** | 1 | |||||

| LFDRS Total | .009 | −.073 | −.070 | .458*** | .471*** | 1 | ||||

| FSA | .025 | .049 | −.035 | .263*** | .287*** | .786*** | 1 | |||

| PV | −.039 | −.096 | −.197** | .279** | .231*** | .760*** | .548** | 1 | ||

| Susceptibility | −.058 | −.112 | .067 | .453*** | .341*** | .801*** | .418*** | .456*** | 1 | |

| Intellectual | .167* | −.045 | −.099 | .304*** | .606*** | .474*** | .239*** | .141* | .250*** | 1 |

Note: SFE = Suspected financial exploitation; FDA = Financial decisional abilities; LFDRS = Lichtenberg Financial Decision Rating Scale; FSA = Financial Situational Awareness; PV = Psychological Vulnerability.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

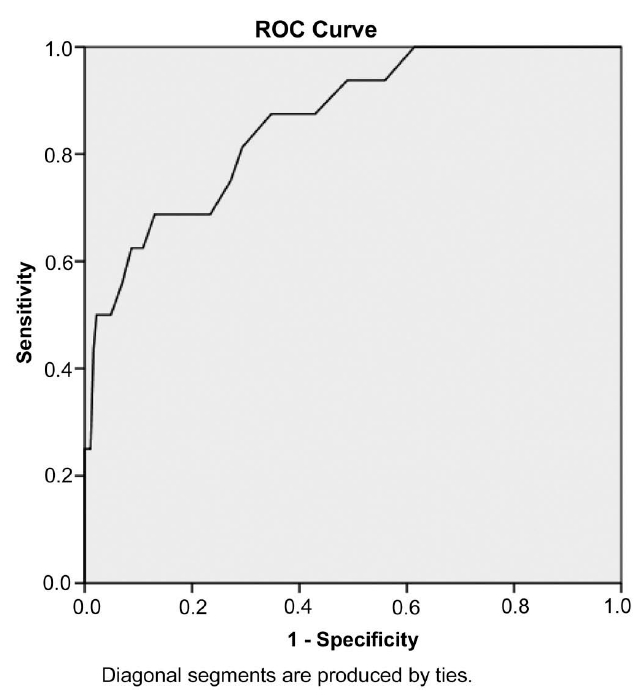

Clinical utility results for the LFDRS on decisional abilities can be found in Table 3 and Figure 1. Figure 1 first mention Overall, the ROC curve was in the good range (see Figure 1; area under the curve = .861). As can be seen in Table 3, a number of cutoff scores can be used, depending on whether one wants to emphasize sensitivity or specificity. A cutoff score of 18 or greater has a sensitivity of .81 and specificity of .71, very high negative predictive power (.97), and very low positive predictive power (.19) for an overall classification rate of 71%. A more conservative cutoff score of 26 or greater has an 89% overall classification rate, but sensitivity drops to 63% and specificity increases to 91%. Positive predictive power rises to 39%, while negative predictive power remains at 97%. These initial clinical utility figures support the use of cutoff scores, although much more data will need to be collected and analyzed to determine the robustness of cutoff scores.

Table 3.

LFDRS Total score predicting Some/Major Concerns about financial decisional abilities.

| Cutoff | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value | Overall Correct Classification |

| 13 or greater | 93.8 | 44.0 | 12.7 | 98.8 | 48.0 |

| 14 or greater | 93.8 | 51.1 | 14.3 | 98.9 | 54.5 |

| 15 or greater | 87.5 | 57.1 | 15.1 | 98.1 | 59.5 |

| 16 or greater | 87.5 | 60.9 | 16.3 | 98.2 | 63.0 |

| 17 or greater | 87.5 | 65.2 | 17.9 | 98.4 | 67.0 |

| 18 or greater | 81.3 | 70.7 | 19.4 | 97.7 | 71.5 |

| 19 or greater | 75.0 | 72.8 | 19.4 | 97.1 | 73.0 |

| 20 or greater | 68.8 | 76.6 | 20.4 | 96.6 | 76.0 |

| 21 or greater | 68.8 | 78.8 | 22.0 | 96.7 | 78.0 |

| 22 or greater | 68.8 | 81.0 | 23.9 | 96.8 | 80.0 |

| 23 or greater | 68.8 | 83.7 | 26.8 | 96.9 | 82.5 |

| 24 or greater | 68.8 | 87.0 | 31.4 | 97.0 | 85.5 |

| 25 or greater | 62.5 | 89.1 | 33.3 | 96.5 | 87.0 |

| 26 or greater | 62.5 | 91.3 | 38.5 | 96.6 | 89.0 |

| 27 or greater | 56.3 | 92.9 | 40.9 | 96.1 | 90.0 |

| 28 or greater | 50.0 | 95.1 | 47.1 | 95.6 | 91.5 |

| 29 or greater | 50.0 | 95.7 | 50.0 | 95.7 | 92.0 |

| 30 or greater | 50.0 | 96.2 | 53.3 | 95.7 | 92.5 |

Note: LFDRS = Lichtenberg Financial Decision-making Rating Scale.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve of LFDRS Total Score predicting Some/Major Concerns about financial decisional abilities.

AUC = .861

Overall, 18% (n = 36) were judged to have experienced suspected financial exploitation within the past 18 months. Table 4 presents comparisons between those with suspected financial exploitation and those without financial exploitation. None of the demographic variables was significantly related to suspected financial exploitation, although there was a trend for women to be more likely to have experienced suspected financial exploitation (p = .067). Those with suspected financial exploitation scored higher on the overall LFDRS risk score, as well as each of the four subscales. The correlations reported in Table 2 indicate that suspected financial exploitation was significantly correlated with the total LFDRS score, each subscale risk score, and overall financial decisional ability rating; those participants with financial decisional ability deficits were more likely to have suspected financial exploitation.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of demographics and LFDRS Total and Subscale Scores by suspected history of financial exploitation.

| Variable | Total (N = 200) | No SFE (n = 164) | SFE (n = 36) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

M (SD) or % |

M (SD) or % |

M (SD) or % |

||

| Age | 71.5 (7.4) | 71.5 (7.4) | 71.3 (7.4) | .868 |

| Education (years) | 15.3 (2.6) | 15.5 (2.6) | 14.9 (2.5) | .223 |

| Race | .115 | |||

| Caucasian | 48.0% | 50.6% | 36.1% | |

| African American | 52.0% | 49.4% | 63.9% | |

| Gender (female) | 74.0% | 71.3% | 86.1% | .067 |

| LFDRS Total | 16.0 (8.6) | 14.2 (6.8) | 24.4 (10.8) | <.001 |

| FSA | 7.2 (3.2) | 6.8 (3.1) | 8.9 (3.2) | <.001 |

| PV | 3.1 (2.8) | 2.7 (2.5) | 4.7 (3.4) | <.001 |

| Susceptibility | 3.6 (3.8) | 2.7 (2.7) | 7.2 (5.5) | <.001 |

| Intellectual | 2.3 (2.0) | 1.96 (1.6) | 3.5 (3.0) | .004 |

Note: SFE = Suspected financial exploitation; LFDRS = Lichtenberg Financial Decision Rating Scale; FSA = Financial Situational Awareness; PV = Psychological Vulnerability.

p-values are reported for t-tests or chi-square tests as appropriate.

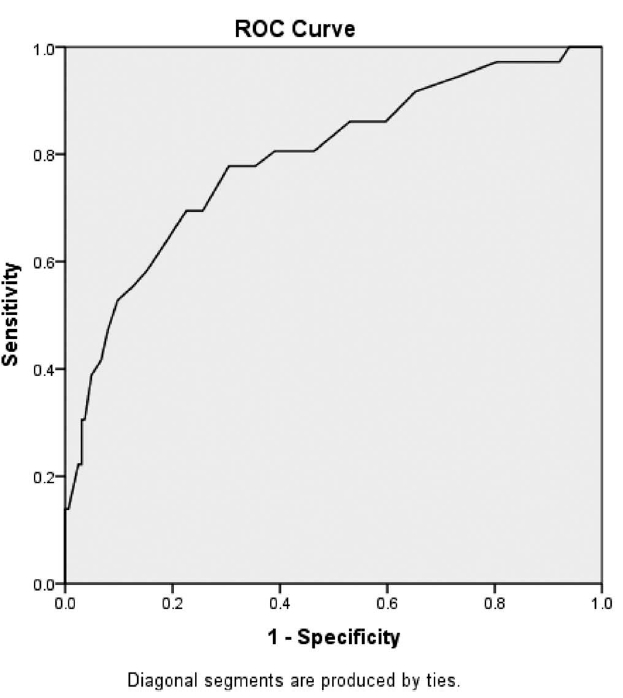

Results for the clinical utility of the LFDRS for suspected financial exploitation can be found in Table 5 and Figure 2. Overall, the ROC curve was in the fair to good range (area under the curve = .792). As can be seen in Table 5, a number of cutoff scores can be used to determine risk for financial exploitation. A cutoff score or 18 or greater had a sensitivity of 69%, specificity of 74%, a positive predictive power of 37% and a negative predictive power of 92% (overall 74% correct classification rate). The overall rate jumps to 84% at a cutoff score of 25 or greater, but sensitivity dips to 47%.

Table 5.

LFDRS—Total score predicting suspected financial exploitation.

| Cutoff | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value | Overall Correct Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 or greater | 97.2 | 19.5 | 21.0 | 97.0 | 33.5 |

| 10 or greater | 94.4 | 26.8 | 22.1 | 95.7 | 39.0 |

| 11 or greater | 91.7 | 34.8 | 23.6 | 95.0 | 45.0 |

| 12 or greater | 86.1 | 40.2 | 24.0 | 93.0 | 48.5 |

| 13 or greater | 86.1 | 47.0 | 26.3 | 93.9 | 54.0 |

| 14 or greater | 80.6 | 53.7 | 27.6 | 92.6 | 58.5 |

| 15 or greater | 80.6 | 61.0 | 31.2 | 93.5 | 64.5 |

| 16 or greater | 77.8 | 64.6 | 32.6 | 93.0 | 67.0 |

| 17 or greater | 77.8 | 69.5 | 35.9 | 93.4 | 71.0 |

| 18 or greater | 69.4 | 74.4 | 37.3 | 91.7 | 73.5 |

| 19 or greater | 69.4 | 77.4 | 40.3 | 92.0 | 76.0 |

| 20 or greater | 63.9 | 81.1 | 42.6 | 91.1 | 78.0 |

| 21 or greater | 61.1 | 82.9 | 44.0 | 90.7 | 79.0 |

| 22 or greater | 58.3 | 84.8 | 45.7 | 90.3 | 80.0 |

| 23 or greater | 55.6 | 87.2 | 48.8 | 89.9 | 81.5 |

| 24 or greater | 52.8 | 90.2 | 54.3 | 89.7 | 83.5 |

| 25 or greater | 47.2 | 92.1 | 56.7 | 88.8 | 84.0 |

| 26 or greater | 41.7 | 93.3 | 57.7 | 87.9 | 84.0 |

| 27 or greater | 38.9 | 95.1 | 63.6 | 87.6 | 85.0 |

| 28 or greater | 30.6 | 96.3 | 64.7 | 86.3 | 84.5 |

| 29 or greater | 30.6 | 97.0 | 68.8 | 86.4 | 85.0 |

Note: LFDRS = Lichtenberg Financial Decision-making Rating Scale.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve of LFDRS—Total Score predicting suspected financial exploitation.

AUC = .792

To examine the effects of possible cognitive decline and impaired decisional capacity on suspected financial exploitation (SFE; Hypothesis 3), we used a low-score classification procedure to identify 38 participants with possible cognitive decline (PCD). Low scores on neuropsychological tests are common in samples of healthy older adults (Binder, Iverson, & Brooks, 2009). Therefore, we selected a cutoff of 4 or more scores falling below 1 SD of our sample mean as the criteria for abnormally low performance in order to minimize false positives (Ingraham & Aiken, 1996). While many factors contribute to performance variability, our battery of tests was selected in large part to maximize the sensitivity to cognitive decline in older adult populations. Therefore, we believe it is appropriate to describe abnormally low performance on this battery as suggestive of cognitive decline.

We chose not to use established criteria for dementia screening with the MMSE to create groups based on cognitive status because we are less concerned about the presence of global impairment. Indeed, few participants scored below MMSE clinical cutoff scores.

We chose to use raw scores for our analyses rather than adjusted scores using clinical normative data. The applicability of demographic-based norms to our sample of older adult decision makers is uncertain because no normative data considers financial decision-making. It seems probable that our sample would differ substantially from their age-, education- and race-based normative peers, who may no longer manage their finances or make important personal financial decisions independently. We are more interested in the relative cognitive performance of our sample as it relates to decision making and risk for financial exploitation rather than their relative standing to the older adult population as a whole.

The demographic characteristics and neuropsychological test scores of participants who performed within normal limits (WNL; three or fewer low scores) and those with PCD (four or more low scores) are presented in Table 6. The PCD group was significantly older, had fewer years of formal education, and had a higher proportion of men, but there was no significant racial difference between groups. The PCD group performed significantly worse on all neuropsychological measures, and effect sizes were large—notably, greater than 1.5 for the TMT B, Stroop, and RAVLT Total Words.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics of demographics and neuropsychological test scores by cognitive performance.

| Variable | WNL [≤ 3 low scores] (n = 162) |

Possible Cognitive Decline [≥ 4 low scores] (n = 38) |

p-value* | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) or % | M (SD) or % | |||

| Age | 70.6 (6.6) | 75.3 (9.2) | .004 | |

| Education (years) | 15.7 (2.5) | 13.7 (2.3) | >.001 | |

| Race | .242 | |||

| Caucasian | 50.0% | 39.5% | ||

| African American | 50.0% | 60.5% | ||

| Gender (female) | 77.8% | 57.9% | .012 | |

| WRAT4 Word Reading | 59.1 (6.6) | 50.1 (9.8) | >.001 | 1.07 |

| Animal Naming | 20.4 (4.5) | 15.3 (4.9) | >.001 | 1.08 |

| COWAT | 41.0 (11.9) | 27.3 (10.4) | >.001 | 1.23 |

| BNT | 14.2 (1.1) | 12.8 (2.0) | >.001 | 0.87 |

| MMSE | 29.1 (1.2) | 26.1 (3.1) | >.001 | 1.28 |

| TMT Part A | 36.7 (11.0) | 59.4 (36.4) | >.001 | 0.84 |

| TMT Part B | 90.1 (31.2) | 186.9 (71.2) | >.001 | 1.76 |

| Stroop Word | 88.8 (12.9) | 71.5 (15.9) | >.001 | 1.19 |

| Stroop Color | 64.0 (9.9) | 47.1 (11.6) | >.001 | 1.57 |

| Stroop Color-Word | 33.2 (7.6) | 20.3 (8.1) | >.001 | 1.64 |

| RAVLT Total Words | 45.1 (8.0) | 31.8 (9.2) | >.001 | 1.54 |

| RAVLT Immediate Recall | 9.1 (2.9) | 5.5 (3.2) | >.001 | 1.18 |

| RAVLT Delayed Recall | 8.6 (3.4) | 4.7 (3.3) | >.001 | 1.16 |

Note: WNL = Within Normal Limits; WRAT4 = Wide Range Achievement Test 4; COWAT = Controlled Oral Word Association Test; BNT = Boston Naming Test; MMSE = Mini-Mental Status Examination; TMT = Trailmaking Test; RAVLT = Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

p-values are reported for t-tests or chi-square tests as appropriate.

Results of a chi-square test of the association between PCD and SFE are presented in Table 7. The rate of SFE among participants who performed within normal limits on neuropsychological tests was 14.3%, and the rate of SFE among the PCD group was double that of those with cognitive test scores within normal limits, 31.3%, which was significantly elevated (X2 = 5.86; p < .02).

Table 7.

Results of chi-square test and descriptive statistics for cognitive status by SFE.

| Cognitive Status | No SFE | SFE |

|---|---|---|

| WNL | 138 (85.7%) | 24 (14.3%) |

| PCD | 26 (68.4%) | 12 (31.6%) |

Note: X2 = 5.86, df = 1, p = .015. Numbers in parentheses indicate row percentages.

To examine the association between financial decisional abilities, PCD, and SFE, we conducted nested chi-square tests; results are presented in Table 8. It is striking that for those with no cognitive decline and intact decisional abilities, 14% were classified as having SFE. Forty percent of those with decisional impairment but no cognitive decline were rated as having SFE. Due to the small numbers of exploited individuals in each group, however, these differences were not significant. In the more cognitively vulnerable group (PCD group), 28.9% had impaired decisional ability (more than three times the base rate of 8%). When examining PCD by decisional impairment, almost 73% of those with decisional impairment also had SFE. In contrast, only 14.7% of those in the PCD group with intact decisional abilities had SFE. These differences were significant (X2 = 12.13; p < .001). These data imply that risk of financial exploitation increases with either decisional deficiencies or cognitive decline, but it particularly increases with a combination of both decisional impairment and PCD; this provides support for Hypothesis 3.

Table 8.

Results of chi-square test and descriptive statistics for cognitive status by FDA by SFE.

| Cognitive Status | FDA | No SFE | SFE |

|---|---|---|---|

| WNL1 | No Concerns | 135 (86%) | 22 (14%) |

| Some/Major Concerns | 3 (60%) | 2 (40%) | |

| Total | 138 | 24 | |

| PCD2 | No Concerns | 23 (85.2%) | 4 (14.8%) |

| Some/Major Concerns | 3 (27.3%) | 8 (72.7%) | |

| Total | 26 | 12 |

Note: FDA = Financial Decisional Abilities; SFE = Suspected financial exploitation; WNL = Within normal limits; PCD =Possible cognitive decline. Numbers in parentheses indicate row percentages within cognitive status group.

X2 = 2.59, df = 1, p = .107.

X2 = 12.132, df = 1, p < .001.

Discussion

This is the first in-depth study that examines financial decision-making, cognitive functioning, and the psychosocial aspects of financial experience and decision-making, and further, links these measures to ratings of financial capacity for real- world decisions and to actual cases of suspected financial exploitation. The link between financial decision-making deficits, psychosocial vulnerabilities related to financial matters, and financial exploitation is not only supported at the level of significance (p < .05), but also at the level of more stringent testing for clinical utility, with receiver operating characteristic curve values of .86 (decision-making) and .79 (suspected financial exploitation). The findings of this study have implications for conceptual models of financial decision-making and exploitation and for application to the practice of risk assessment with community-dwelling older adult populations.

The LFDRS takes a novel approach to the linkages between financial decision-making and financial exploitation. In contrast to Spreng and colleagues (2016), who postulate the interaction of cognitive skills and financial decision-making with normative aging experiences—such as positivity bias and age-related vulnerability to deception—our model also examines psychosocial vulnerabilities. The models thus differ in how psychosocial vulnerability is viewed. Building on five years of research since our finding that psychological vulnerability predicts significantly higher risk for being a victim of fraud, the LFDRS operationalizes psychological vulnerability in connection with financial experiences and decisions. In short, the LFDRS adapts clinical symptoms of anxiety, depression, loneliness, and poor self-efficacy to the domain of financial decision-making. Empirical support for the LFDRS’s conceptual model and items can be found in Lichtenberg and colleagues (2017a). This study provides additional support for the conceptual model and for the idea that vulnerability in both psychosocial areas and decision-making ability renders community-dwelling individuals more likely to be exploited.

The findings of this study also provide further support for the LFDRS. In particular, this study demonstrates that an LFDRS quantitative scoring system can be used to identify those at highest risk of financial decision-making incapacity and financial exploitation. This is the first instrument to demonstrate that financial decision-making incapacity for actual decisions made by an older adult is related to suspected actual financial exploitation. As a result, clinicians now have an instrument to assess older adults and make clinical judgments about risk for incapacity and exploitation.

Furthering the clinical utility of the LFDRS, our results also demonstrate the relationship between performance on a brief neuropsychological test battery, financial decisional abilities, and suspected financial exploitation. Impaired decisional abilities alone were associated with a greatly increased rate of suspected financial exploitation. We found that the rate of suspected financial exploitation was similar among participants who were rated as having no concerns about their decisional abilities, regardless of whether they scored low on neuropsychological tests. This finding suggests that neuropsychological performance that indicates possible cognitive decline among older adults does not necessarily increase susceptibility to financial exploitation; intact financial decisional abilities or other contextual factors may serve to protect, to some degree, those with declining cognitive abilities from exploitation. In contrast, people with average neuropsychological performance and, at the same time, concerns about their decisional abilities were not significantly more likely to report suspected financial exploitation, although there was a trend toward significance. Importantly, people with impaired decisional abilities and poor cognitive performance had the highest rate of suspected financial exploitation.

The study has several limitations. First, we used a community-based sample with a low base rate of incapacity (8%), and thus the clinical utility data presented here are based on a small number of cases. In samples from Adult Protective Services, however, measurement of financial decision-making ability using the LFDSS has been equally effective in higher-risk groups (Lichtenberg et al., 2017b). Second, cases of financial exploitation were identified by consensus conference and could not be substantiated. This is similar, however, to most research with community-based samples. The sample was nonrandom, and thus may be biased in unknown ways that could influence the results. Other limitations include that only English speaking older adults were tested, and the sample was mostly women. Despite these limitations, however, the study is an important step forward in the use of new tools to assess financial decision-making capacity and financial exploitation.

Clinical implications.

Clinically useful risk scoring system for both financial decision-making capacity and financial exploitation.

Multiple choice self-report and rater items produced cutoff scores that have an excellent balance of sensitivity and specificity.

Demonstrates that a person-centered tool that analyzes an individual’s financial decisions can produce clinically useful risk scores.

Builds on the empirical evidence from (Lichtenberg et al., 2017a) which demonstrated support for the scale’s reliability and validity; by introducing a clinically relevant scoring system.

Funding

National Institute of Justice (MU-CX-0001),The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice. National Institutes of Health P30 (AG015281), Michigan Center for Urban African American Aging Research; National Institutes of Health P30 (P30AG053760) Michigan Alzheimer’s Center Core grant American House Foundation and Retirement Research FoundationNational Institute on Aging [AG015281,P30AG053760];American House Foundation[0001];Retirement Research Foundation [RRF 2014–24];U.S. Department of Justice[MU-CX-0001]

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/wcli.

References

- Acierno R, Hernandez-Tejada MA, Antetzberger GJ, Loew D, & Muzzy W (2017). The National Elder Mistreatment Study: An 8-year longitudinal study of outcomes. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 29, 254–269. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2017.1365031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS, & Grisso T (1988). Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. New England Journal of Medicine, 319, 1635–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812223192504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belbase AB, & Sanzenbacher GT (2017). Cognitive aging and the capacity to manage money. Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, 17(1), 1–7. http://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/IB_17-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Hamsher K, Varney NR, & Spreen O (1983). Contributions to Neuropsychological Assessment. New York, United States: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Binder LM, Iverson GL, & Brooks BL (2009). “To err is human: “Abnormal” neuropsychological scores and variability are common in healthy adults. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 24, 31–46. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acn001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Yu LY, Buchman AS, & Bennett DA (2012). Poor decision making is a consequence of cognitive decline among older persons without Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment. PLOS One, 7(8), 1–5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Yu LY, Buchman AS, & Bennett DA (2013). Poor decision making is associated with an increased risk of mortality among community-dwelling older persons without dementia. Neuroepidemiology, 40(4), 247–252. doi: 10.1159/000342781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KJ, Iris M, Ridings JW, Langley K, & Wilber KH (2010). Self-report measure of financial exploitation of older adults. Gerontologist, 50, 758–773. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2011.584045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, & Hugh M (1975). “Mini mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12, 189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden JC (1978). Stroop Color and Word Test. Chicago, United States: Stoelting Co. [Google Scholar]

- Hall LN, Ficker LJ, Chadiha LA, Green CR, Jackson JS, & Lichtenberg PA (2016). Promoting retention: African American older adults in a research volunteer registry. Gerontology & GeriatricMedicine, 2(1–9). doi: 10.1177/2333721416677469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SD, Boyle PA, James BD, Yu LY, Barnes LL, & Bennett DA (2015). Discrepancies between cognition and decision making in older adults. Aging—Clinical and Experimental Research, 28, 99–108. doi: 10.1007/s40520-015-0375-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham LJ, & Aiken CB (1996). An empirical approach to determining criteria for abnormality in test batteries with multiple measures. Neuropsychology, 10(1), 120. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.10.1.120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan EF, Goodglass H, & Weintraub S (1983). The Boston Naming Test (2nd ed). Philadelphia, United States: Lea and Febiger. [Google Scholar]

- Lezak. (1983). Neuropsychological Assessment (3rd edition). New York, United States: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA, Ficker L, Rahman-Filipiak A, Tatro R, Farrell C, Speir JJ, & Jackman JD (2016b). The Lichtenberg Financial Decision Screening Scale: A new tool for assessing financial decision making and preventing financial exploitation. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 28, 134–151. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2016.1168333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA, Ficker LJ, & Rahman-Filipiak A (2016c). Financial decision-making abilities and financial exploitation in older African Americans: Preliminary validity evidence for the Lichtenberg Financial Decision Rating Scale (LFDRS). Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 28, 14–33. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2015.1078760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA, Ocepek-Welikson K, Ficker LJ, Gross E, Rahman-Filipiak A, & Teresi J (2017a). Conceptual and empirical approaches to financial decision making in older adults: Results from a financial decision-making rating scale. Clinical Gerontologist, 41, 42–65. PMC5766370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA, Stickney L, & Paulson D (2013). Is psychological vulnerability related to the experience of fraud in older adults? Clinical Gerontologist, 36, 132–146. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2012.749323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA, Stoltman J, Ficker LJ, Iris M, & Mast BT (2015). A person-centered approach to financial capacity assessment: Preliminary development of a new rating scale. Clinical Gerontologist, 38, 49–67. JGP.0b013e318157cb00 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA, Sugarman M, Paulson D, Ficker L, & Rahman-Filipiak A (2016a). Psychological and functional vulnerability predicts fraud cases in older adults: Results of a nationally representative longitudinal study. Clinical Gerontologist, 39(1), 48–63. PMC4824611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA, Teresi JA, Ocepek-Welikson K, & Eimick J (2017b). Reliability and validity of the Lichtenberg Financial Decision Screening Scale. Innovation in Aging, 1(1), 1–9. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igx003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeill SE, & Lichtenberg PA (1999). The MacNeill-Lichtenberg Decision Tree: A unique method of triaging mental health problems in older medical rehabilitation patients. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 81, 618–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marson D (2016). Conceptual models and guidelines for clinical assessment of financial capacity. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 31(6), 541–553. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acw052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Connolly M-T, Breckman R, Spreng RN, & Lachs MS (2015). Elder mistreatment: Priorities for consideration by the White House Conference on Aging. Gerontologist, 55, 320–327. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn MJ, Nerenberg L, Navarro AE, & Wilber KH (2017). Developing an undue influence screening tool for Adult Protective Services. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 29, 157–185. doi: 10.1080/089466566.2017.1314844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, & Wolfson D (1985). The Halstead–Reitan Neuropsycholgical Test Battery: Therapy and clinical interpretation. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychological Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruffman T, Murray J, Halberstadt J, & Vater T (2012). Age-related differences in deception. Psychology and Aging, 27, 543–549. doi: 10.1037/a0023380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M (1996). Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test: A Handbook. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BT, & Lichtenberg PA (2011). Influence of reading ability on neuropsychological performance in African American elders. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 26, 624–631. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acr062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreng RN, Karlawish J, & Marson DC (2016). Cognitive, social and neural determinants of diminished decision-making and financial exploitation risk in aging and dementia: A review and new model. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 28, 320–344. doi: 10.1080/o8946566.2016.1237918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS, & Robinson GJ (2006). Wide Range Achievement Test-IV: Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Wong JS, & Waite LJ (2017). Elder mistreatment predicts later physical and psychological health: Results from a national longitudinal study. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 29, 15–42. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2016.1235521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]