Abstract

Children with substantiated child maltreatment (CM) experience adverse health outcomes. However, it is unclear whether substantiation vs. an investigation not resulting in substantiation has a greater impact on subsequent adolescent health. Propensity scores were used to examine the effect of investigated reports on the subsequent health of 503 adolescent females. CM was categorized into three levels: 1) investigated and substantiated, 2) investigated but unsubstantiated, and 3) no investigation. Models using inverse propensity score weights estimated the effect of an investigation on subsequent teen motherhood, HIV-risk behaviors, drug use, and depressive symptoms. Females with any investigation, regardless of substantiation status, were more likely to become teen mothers, engage in HIV-risk behaviors, and use drugs compared to females with no investigated report. Substantiated CM was associated with depressive symptoms. Findings underscore the importance of maintaining case records, regardless of substantiation, to better serve adolescents at risk for deleterious outcomes. Prospective methods and propensity scores bolster causal inference and highlight how interventions implemented following investigation are an important prevention opportunity.

Keywords: Substantiation Status, Propensity Score, Adverse Health Outcomes

Child maltreatment (CM; i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect) is a highly prevalent public health concern (Sedlak et al., 2010) with substantial evidence of a sustained risk for many of the major causes of morbidity (Norman et al., 2012) and mortality (Felitti et al., 1998) in the U.S. For example, physical abuse in childhood is associated with high BMI scores in adulthood (Bentley & Widom, 2009). A meta-analysis of 37 studies representing more than 3 million participants reported a significant association between the experience of sexual abuse in childhood and later life diagnoses of anxiety disorder, depression, eating disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, sleep disorders, and suicide attempts (Chen et al., 2010). The use of reports where Child Protective Services (CPS) agencies investigate allegations and make determinations regarding substantiation has long been a strategy for creating experimental conditions in research examining the long-term impact of maltreatment (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2001; Runyan et al., 1998; Thornberry, Bjerregaard, & Miles, 1993; Trickett, Noll, & Putnam, 2011; Widom, Czaja, Bentley, & Johnson, 2012; Widom, Raphael, & DuMont, 2004). Although the process varies by state, it is common for suspected maltreatment cases to first be referred to a dedicated “hotline” maintained by the state or local child welfare agency. These initial calls are usually screened in a cursory manner and referred to the local child welfare agency for further consideration. Some local agencies conduct further screening prior to investigation. Once cases are referred for an investigation, a dispensation of “substantiated” or “unsubstantiated” is made based on the outcome of the investigation. Data show, however, that the majority of CM reports are not substantiated, often because they do not meet a threshold of CM defined in state law. Just over one third (37.4%) of all children in the U.S. are the subject of a CPS report prior to the age of eighteen (Kim, Wildeman, Jonson-Reid, & Drake, 2017), yet only 12.5% of allegations of maltreatment investigated by CPS are substantiated (Wildeman et al., 2014). The discrepancy between reports and substantiations raises the possibility that reports may indicate adversities that, although shy of a substantiation threshold, place children at risk for a host of problematic outcomes (Kohl, Jonson-Reid, & Drake, 2009). Examining health disparities between children who have substantiated reports of CM and those whose reports are investigated but unsubstantiated is an important first step in identifying sectors of the population that can benefit from early intervention to stave off deleterious outcomes.

A growing body of research has examined potential health disparities based on the substantiation status of a CPS investigation. Using data from the Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect (LONGSCAN), Hussey and colleagues (2005) examined 10 behavioral (i.e., internalizing, externalizing, adaptive) and developmental outcomes among 801 children 4–8 years old. There were no significant differences among children with at least one substantiated CM report and those with unsubstantiated reports. Drawing from state records, Leiter and colleagues (1994) compared academic and juvenile and delinquency outcomes of 2,228 random children with either a substantiated or unsubstantiated maltreatment report and 388 children without any child welfare involvement. There were no significant differences based on CM substantiation status; that is, children with a substantiated report were not significantly different from children with an unsubstantiated report. These studies use varied measures for maltreatment (i.e., self-report) and do not use rigorously matched controls. Yet, these studies suggest there may be few differences between children with and without a substantiated allegation of CM across multiple developmental and health outcomes, leading some to caution against distinguishing between substantiated or unsubstantiated cases in research (Drake, 1996). If accurate, this could have important implications for the prevention of adverse health outcomes in the CM population, where services could be provided for all allegations investigated by CPS, rather than only providing services when allegations are substantiated.

The use of causal inference methods, from prospective study designs to analytic propensity scores, to investigate potential health disparities for those with unsubstantiated allegations of CM would advance efforts in knowing whether, and for which health outcomes, preventive services can be recommended by CPS agencies. In the absence of randomization, potential differences in health disparities based on substantiation status is complicated by the presence of confounding variables. The use of propensity score methods, which attempt to mimic randomization by balancing measured confounders across exposure groups, is a well-established analytic approach to strengthening causal inference in observational research (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983) and is more efficient and less biased than traditional covariate-adjusted regression models (McCaffrey et al., 2013). By ensuring that the exposure groups (e.g., substantiated and unsubstantiated allegations of maltreatment) are balanced on the measured confounders, there is greater confidence that any differences are due to the exposure of interest and not the confounding variables. However, few studies have used this approach to assess the effect of CM on later health outcomes and, to our knowledge, propensity score methods have not been used to address the question of potential health disparities based on CPS substantiation status.

The current study advances prior research by using propensity score methods (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983) to examine health disparities based on variation in substantiation of allegations. The study sought to test a set of adolescent outcomes representing multiple domains of functioning (e.g., substance use, mental health, sexual health, and physical health), each of which has important public health implications for primary prevention efforts and long-term health. Specifically, the study examined the risk for teen motherhood, HIV risk, drug use, and depressive symptoms based on the substantiation status of CPS investigations. Substantiation status was categorized as: 1) investigation by CPS was substantiated; 2) investigation by CPS was unsubstantiated; or 3) no investigation by CPS. Two hypotheses were tested: 1) any CPS investigation would predict a greater risk for adverse health behaviors and outcomes when compared to those with no CPS investigation; and 2) a CPS investigation that was substantiated would predict a greater risk for adverse health behaviors and outcomes when compared to those whose allegations were investigated but unsubstantiated. By potentially enhancing causal inference, it may be possible to identify a sector of the population that could benefit from primary prevention services.

Method

Study Population

Data were from a prospective cohort study (2007–2011) aimed at examining the impact of CM on subsequent female health (R01-HD052533). The sample was drawn from the catchment area of a large urban children’s hospital located in the Midwest region of the U.S. Although this hospital mainly serves inner-city youth, the catchment area is relatively large and encompasses large rural counties. The original study included 514 nulliparous adolescent females aged 14–17 matched as case-control. A “case” was defined as having an investigated and substantiated maltreatment report (physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect) in the previous year (N = 273). Cases were referred directly from the local child protective service agency. The agency assigns a “primary” maltreatment type to each case depending on which type was used in the referral and/or which type was the most salient in the case. In many cases (i.e., 70%) there was more than one type of maltreatment documented in the case files, but the primary maltreatment type was used to categorize maltreatment (see below). Comparison females without CPS contact (N = 241) were matched on the following demographic characteristics: race, family income, age, and family structure (1- or 2-parent households). Participants completed annual study assessments for up to four years or until they reached age 19. The retention rate over the longitudinal age 19 follow-up was 97.5%. At the initial assessment, the sample had a mean age of 15.26 years (SD = 1.07), a median household income of $30,000–$39,000, a racial demographic of 43% Caucasian, 48% African-American, 8% Bi- or Multi-racial, 0.5% Hispanic, and 0.5% Native American, with 57% in single-parent households. During the five-year study, CPS records were continually examined to ensure that allegations of maltreatment were assessed and captured in both groups from birth to current age. The present (2018) analytic sample was reduced (final N = 503) to ensure that the temporal ordering of the CPS investigation on later health outcomes was maintained. For example, the nine subjects that reported engaging in drug use behavior prior to any allegation of CM investigated by CPS were excluded from the present analysis. All procedures were approved by the local institutional review board.

Measures

Substantiation status

A sequence of steps created an exclusive and exhaustive categorical variable reflecting a three-level variable of CM status: those who never had a CPS investigation (n = 188; coded as “0”), those whose CPS investigation was unsubstantiated (“1”; n = 136), and those whose CPS investigation was substantiated (“2”; n = 179). Among females who had a report to CPS investigated, the mean number of reports for the substantiated group was 3.0 (SD = 2.8) and the average age at first report was 8.7 (SD = 6.1). For the unsubstantiated group the mean number of reports was 4.6 (SD= 3.3) and the average age at first report was 5.7 (SD= 4.6).

Outcomes

Teen mother

Teen mother was first assessed via self-report at each annual assessment through age 19 using a single-item indicator, then verified via hospital labor and delivery records for those who indicated giving birth. A dummy-coded indicator variable (0 = “No, never a mother,” 1 = “Yes, ever a mother”) was used in analyses.

HIV-risk behaviors

HIV-risk was assessed by summing the responses to ever engaging in a series of 11 HIV-risk-related behaviors such as unprotected sex, condom failure during sex, sex with an intravenous drug user, intravenous drug use, and one-night stands. An index variable from 0 to 11 was created at the last annual assessment available for each participant. This variable was treated as a count variable in analyses (M= 2.9, SD = 2.2).

Drug use

Drug use was assessed by summing responses to questions measuring use of any drugs (i.e., tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, hallucinogens, crack, amphetamines, barbiturates/tranquilizers, heroin, sniffed glue, steroids, or “roofies”) in the past year. For each drug, response options included the following: 0 = 0 occasions, 1 = 1–2 occasions, 2 = 3–5 occasions, 3 = 6–9 occasions, 4 = 10–19 occasions, 5 = 20–39 occasions, and 6 = 40 or more occasions. Due to skewness, drug use was log transformed for the outcome analyses and presentation in the table; however, for the text, the estimate was back log transformed and presented as a percent increase for interpretability (M = 5.2, SD = 6.5).

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck, Steer, Ball, & Ranieri, 1996) by summing responses to 21 items assessing the presence and severity of depressive symptoms in the past two weeks. This variable was treated as continuous outcome (M = 10.1, SD= 9.9).

Confounders

Various adolescent and maternal demographic variables were included in the propensity scores. Adolescent’s age at baseline was continuous. Adolescent minority status was dichotomous and dummy coded (0 = White and 1 = all other race/ethnicities). Maternal education was coded 0 = Less than high school, 1 = High school graduate, and 2 = Some college. Maternal minority status was coded (0 = White and 1 = all other race/ethnicities). Maternal income was coded 0 = <$10,000, 1 = $10,000–$29,999, 2 = $30,000–$49,999, and 3 ≥ $50,000. Mother was a teen mother was calculated from the mother’s age and the date of birth of all children and coded (0 = No and 1 = Yes, teen mother). Father-figure present on a daily basis from birth to 5 years of age was dichotomous (0 = No and 1 = Yes).

Statistical Analysis

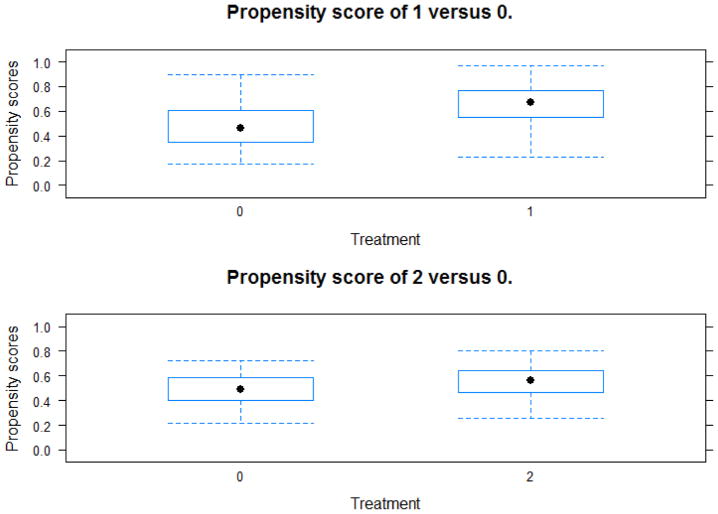

First, multinomial propensity scores were computed using generalized boosted modeling (GBM) to obtain the predicted probabilities of substantiation status (Lee, Lessler, & Stuart, 2009; McCaffrey, Ridgeway, & Morral, 2004). Briefly, GBM is a flexible estimation method that involves an iterative process with multiple regression trees to capture complex and nonlinear relationships between treatment assignment and the covariates without over-fitting the data (McCaffrey et al., 2004). Overlap of the propensity score distributions was identified using boxplots for each pairwise comparison with no known CPS investigation serving as the referent category (Harder, Stuart, & Anthony, 2010). While there is no specific rule about what constitutes sufficient overlap, the more the boxplots of the different groups overlap (mean and spread), the greater the confidence in that each adolescent could have been in any of the groups (similar to randomization in experimental studies). Further, although the mean propensity scores were different for each group, there was sufficient evidence of overlap to proceed with analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Boxplot showing the overlap in the distribution of the propensity scores between “investigated but unsubstantiated” and “no investigation” (1 vs. 0) and “investigated and substantiated” and “no investigation” (2 vs. 0).

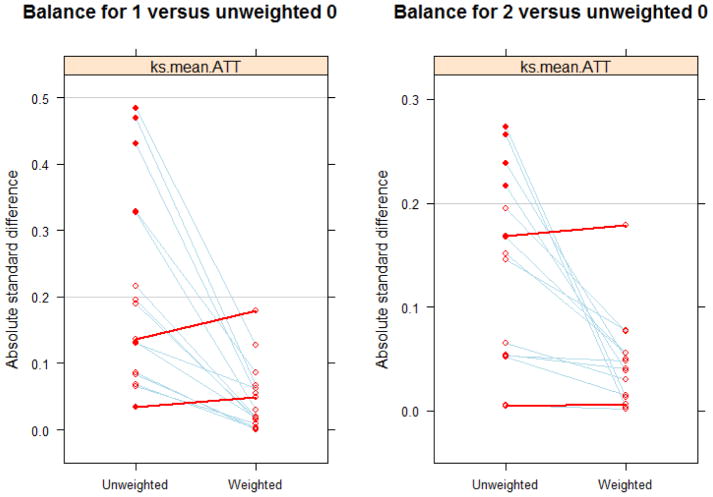

Next, inverse propensity weights (IPWs; Robins et al., 2000) were used to weight the data to ensure there was balance on the measured confounders across the pairwise exposure groups. The IPWs were calculated as the inverse of the estimated propensity score for one level of the exposure group and the inverse of one minus the estimated propensity score for the no investigation by CPS group. This was repeated for the other pairwise comparison of unsubstantiated investigation by CPS and no investigation by CPS. Balance was assessed by calculating standardized mean differences (Stuart, 2010) between each pairwise comparison for each of the confounders to ensure that the absolute standardized mean difference less than .20 (Cohen, 1988; Harder et al., 2010). Figure 2 shows that the standardized mean difference between exposure groups dramatically decreases once the IPW is applied. For example, the mean difference between group 2 vs. 0 on the covariate income was .36 in the unweighted model and .04 in the weighted model. Estimation of the propensity scores, calculation of the IPWs, and calculation of standardized mean differences were computed using the twang package in R (Burgette, McCaffrey, & Griffin, 2015; Ridgeway, McCaffrey, Morral, Burgette, & Griffin, 2013). All of the identified potential confounders were balanced (≤.20) across each of the pairwise comparisons once the data sets were weighted by the IPWs (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Standardized mean differences between “investigated but unsubstantiated” and “no investigation” (1 vs. 0) and “investigated and substantiated” and “no investigation” (2 vs. 0) for each confounder for the unadjusted and the propensity-score-adjusted data.

The causal effect of substantiation status on each of the outcomes was estimated with linear (depressive symptoms and drug use), logistic (teen mother), or Poisson regression (HIV-risk-related behaviors) using the IPWs.

Results

Table 1 shows the prevalence of each of the adolescent and maternal characteristics (i.e., covariates used in the propensity score models) and the adolescent behavioral and health outcomes, stratified by each investigation status group. Omnibus chi-square tests are shown in the table. There was a greater percentage of adolescents of minority race/ethnicity status in the substantiated group compared to the other groups and a greater percentage of adolescents who were a teen mother. Maternal characteristics such as more minority status, lower income, and less education were also associated with CPS investigations, regardless of substantiation. In terms of outcomes, adolescents that had an investigated report by CPS, regardless of substantiation status, engaged in HIV-risk behaviors and drug use in the past year. There was no significant difference across substantiation status groups for mean level of depressive symptoms.

Table 1.

Adolescent and Maternal Characteristics of Analytic Sample by Substantiation Status (N = 503)

| Propensity score variables Characteristic |

Total (N = 503) %, mean |

No investigation by CPS (n = 188) | Investigated but unsubstantiated (n = 136) | Investigated and substantiated (n = 179) | Chi-sq p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent characteristics | |||||

| Baseline average age (SD) | 15.8 (1.1) | 15.7 (1.1) | 15.8 (1.1) | 15.8 (1.1) | .50 |

| Minority race/ethnicity | 56.4% | 52.7% | 48.9% | 65.9% | .005 |

| Father figure around birth to 5 | 84.6% | 87.8% | 84.6% | 81.1% | .24 |

| Maternal characteristics | |||||

| Teen mother | 24.7% | 22.9% | 26.5% | 25.1% | .75 |

| Annual income | |||||

| <$10,000 | 23.2% | 18.3% | 29.2% | 23.9% | <.001 |

| $10,000–$29,999 | 31.3% | 26.3% | 36.9% | 32.4% | |

| $30,000–$49,999 | 22.4% | 24.7% | 21.5% | 20.5% | |

| $50,000 or more | 23.2% | 30.7% | 12.3% | 23.3% | |

| Minority race/ethnicity | 52.5% | 48.9% | 44.5% | 62.1% | .005 |

| Education level | |||||

| Some high school | 20.9% | 16.7% | 30.0% | 18.6% | .005 |

| High school graduate | 28.8% | 24.7% | 31.5% | 31.1% | |

| Some college or more | 50.3% | 38.6% | 38.5% | 50.3% | |

| Adolescent outcomes | |||||

| Teen mother | 15.9% | 8.5% | 21.3% | 19.6% | .002 |

| Average HIV risk behaviors (SD) [0–11] | 2.8 (2.2) | 2.3 (2.0) | 3.2 (2.3) | 3.0 (2.3) | .004 |

| Average drug use in past year (SD) [0–54] | 5.2 (6.5) | 4.1 (5.8) | 5.5 (6.4) | 6.0 (7.1) | .02 |

| Average Beck depression score, past 2 weeks (SD) | 10.1 (9.9) | 8.8 (8.4) | 11.1 (10.5) | 10.6 (10.8) | .08 |

The effect of CM status on subsequent risk behaviors and health outcomes is presented in Table 2. The results suggest that females with a CPS investigation, substantiated or not, had greater odds of becoming a teen mother, engaging in more HIV-risk behaviors, and using more drugs in the past year than did adolescent females without a CPS investigation. Females with a substantiated investigation were more likely to report depressive symptoms in the past two weeks compared to females without a CPS investigation. There were no differences, however, in rates of depressive symptoms for females in the unsubstantiated group as compared to females without a CPS investigation. Of note, as Table 1 shows, females in the unsubstantiated group reported the highest depressive symptoms scores of all three groups. However, there was significant variability within the unsubstantiated group, indicative of marked heterogeneity with respect to depressive symptoms such that mean-level group differences were not detected. This was not the case with the substantiated group, where there was lower variability and marked homogeneity such that mean differences were indeed detectable when compared to females without a CPS investigation. Finally, the unsubstantiated investigation and substantiated investigation groups were not significantly different from one another on all outcomes of interest.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios (and 95% Confidence Intervals) or Parameter Estimates (and Standard Errors) Estimating the Causal Effect of CPS Investigation of Child Maltreatment on Later Health Outcomes

| Outcome | Investigated but unsubstantiated (n = 136) | Investigated and substantiated (n = 179) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teen mother | 2.75 | (1.34, 5.62)** | 2.28 | (1.18, 4.41)* |

| HIV risk behaviors1 | 1.42 | (1.15, 1.74)*** | 1.30 | (1.09, 1.55)** |

| Drug use in past year2 | 0.38 | (.13)** | 0.41 | (.12)*** |

| Beck depression score3 | 1.96 | (±2.56) | 2.42 | (±1.08)* |

Note. Referent group is “no investigation by CPS”. There is no significant difference between unsubstantiated and substantiated groups on any outcome.

HIV risk behaviors is a count measure of risk, range 0–11

Drug use is a continuous variable that was log transformed, range 0–54

Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck et al., 1996) is a continuous measure, range 0–63

p < .05,

p < .01,

p <. 001

Having experienced a CPS investigation, regardless of substantiation, resulted in greater odds of becoming a mother (unsubstantiated OR = 2.75 [95% CI 1.34, 5.62]; substantiated OR= 2.28 [95% CI 1.18, 4.41]). Females with an unsubstantiated investigation engaged in 1.42 (95% CI 1.15, 1.74) more HIV risk-related behaviors than those who did not have a CPS investigation (p < .001), while females who had a substantiated investigation had 1.30 (95% CI 1.09, 1.55) more HIV-risk behaviors (p < .01).

Further, females who had an unsubstantiated investigation had 46% greater drug use score than females without a CPS investigation (p < .01), whereas females who had a substantiated investigation by CPS had a 51% greater drug use score (p < .01). There was an effect of substantiation status on depressive symptoms in the past two weeks, such that females with a substantiated investigation had 2.42 (± 1.08) more depressive symptoms compared to those with no investigated report (p < .05). Unsubstantiated investigations were not significantly associated with depressive symptoms when compared to either the substantiated group (p = .45) or the group with no investigation (p =.10). As outlined above, this lack of differences between the no investigation group is likely due to greater heterogeneity.

Discussion

The goal of the current analysis was to use propensity score methods to strengthen the causal inference of the effect of CM investigations and substantiations on later female adolescent risk behaviors and health outcomes. Females with any investigation, regardless of substantiation status, were more likely to become teen mothers, engage in HIV-risk behaviors, and use drugs compared to females with no investigated report. Substantiated CM was associated with depressive symptoms. The findings challenge the belief that only children who experience substantiated CPS investigations are at increased risk for negative health outcomes. Instead, these findings support the growing body of literature (Hussey et al., 2005; Leiter et al., 1994) that children who are the subject of a CPS investigation that goes unsubstantiated are at similar risk for negative health outcomes as compared to those with a substantiated CPS report. Group differences in depressive symptoms were only detected between the females with no investigated report and females with a substantiated investigation. However, the group with the highest mean for depressive symptoms is actually reported in the group of females with an unsubstantiated report. This group also showed the highest variability and heterogeneity, such that mean-level differences were not detectable. This demonstrates that there are likely many different types of females within the unsubstantiated group with respect to depressive symptoms—some that have few symptoms and some that have many. It may be that this group included subthreshold maltreatment that was relatively minor and some subthreshold maltreatment that was severe but where evidence was lacking such that the case was unable to be proven. Such variability in severity may explain why the heterogeneity in depressive symptoms is detected in these data. Taken together, however, these results demonstrate that being the subject of a CPS investigation signals an important opportunity for primary prevention of teen motherhood, HIV, and drug use—regardless of whether or not the investigation is ultimately substantiated—and for depressive symptoms particularly for those with substantiated reports.

Strengths

The use of prospective methods and causal inference statistical model to investigate the health disparities of CM survivors advances the literature in important ways. First, in order to assert temporal ordering, we prospectively followed adolescent females and modeled outcomes that occurred an average of 12 years subsequent to their CM experience. Second, using propensity score methods on data from observational studies is a means to strengthen causal inference when randomization is impossible or unethical (such as in studies of the impact of CM). Third, by ensuring that there was balance of potential confounders across exposure groups, propensity score approaches mimic randomization thereby providing greater confidence in the causal assertions of findings. As such, these methods serve to strengthen causal inference of the impact of CM on subsequent health outcomes and will aid in our collective ability to convince practitioners and policy makers that CM investigations and substantiations indeed constitute a “causal” pathway to several aspects of adolescent health that are of grave public health concern.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of the current findings, this study is not without limitations. First, it is assumed that there are no unmeasured confounders in the propensity score models. Although a vast improvement over the bulk of prior research that has not utilized propensity score methods, it is likely unmeasured confounders remain that were not included in our seven-variable propensity score model. Second, although this sample is relatively large for a longitudinal, observational study of CM, the sample included only females from a specific geographical area, and findings may not be generalizable to males or those from different areas of the county.

Conclusion

Conditions of grave public health concern including HIV-risk, teen motherhood, and drug use occur significantly more often among adolescents who experience an investigation of CM, regardless of whether or not the report is substantiated. If children who receive a CPS investigation are identified, and risk behaviors averted, there is the potential for significant cost savings and overall improvement in public health. For example, the cost of pregnancy and child birth among teens is estimated to exceed $9 billion (Hoffman, 2013) and treatment of STIs, including HIV, requires a lifetime commitment to therapies (Schackman et al., 2015). The annual cost related to substance use, including tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs, exceeds $740 billion (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2017). The findings of the present study make the case for an argument that a larger public investment in the child welfare system as a whole is warranted. Such an investment could result in the child welfare system being a place where at-risk children can be identified and funneled into primary prevention programs targeting sexual behaviors and substance use onset. Given that over one third of children are subject to a report of CM each year in the U.S. (Kim et al., 2017), this type of early identification will likely result in an overall decrease in national adolescent rates of HIV, motherhood, and substance abuse.

These results also underscore the need to adequately measure and assess CM to include both investigated as well as substantiated cases. To include only the latter may result in decreased effect sizes (Shenk, Noll, Peugh, Griffin, & Bensman, 2015) and an inadequate accounting of the impact of CM. Future research designs should consider methods that allow for the complete and comprehensive examination of CPS records whenever possible. Doing so will advance the field of CM studies and illuminate the true scope and gravity of CM and its related consequences. Further, recent CM legislation changes in many states (e.g., expanded definitions of mandated reporters, increased penalties for not reporting suspected abuse, etc.) have resulted in a substantial increase in the number of children reported to CPS across the county. This signals an opportunity to expand the number of children who may likewise benefit from sex education and substance use prevention efforts. However, there is also a concerning trend in some legislative jurisdictions that requires the expungement of identifying information related to unsubstantiated CPS cases. Such expunction disallows the opportunity to intervene with children who have experienced a CPS report and may handicap efforts to make full use of administrative data to target at-risk populations for preventive services. Expunction efforts should be reexamined with the results of the current study in mind. While the spirit of expunction statutes—to protect the identity of alleged perpetrators who have been exonerated—should indeed be upheld, policies should strike a careful balance with the need to identify, protect, and adequately serve vulnerable and at-risk children.

Acknowledgments

Funding acknowledgement: This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01-HD052533 (Noll), 5UL1TR001425 (Noll, Shenk, Beal), P50DA010075 (Kugler, Guastaferro), K01DA041620 (Beal), R03HD0797 (Kugler), T32DA0176 (Guastaferro). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The study sponsor had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;67:588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley T, Widom CS. A 30-year follow-up of the effects of child abuse and neglect on obesity in adulthood. Obesity. 2009;17(10):1900–1905. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgette LF, McCaffrey DF, Griffin BA. Propensity score estimation with boosted regression. In: Pan W, Haiyan B, editors. Propensity score fundamentals and developments. New York: Guilford Press; 2015. pp. 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chen LP, Murad MH, Paras ML, Colbenson KM, Sattler AL, Goranson EN, … Zirakzadeh A. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2010;85(7):618–629. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Diverse patterns of neuroendocrine activity in maltreated children. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(3):677–693. doi: 10.1017/S0954579401003145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. New York: Taylor & Francis; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Drake B. Unraveling “unsubstantiated. Child Maltreatment. 1996;1(3):261–271. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, … Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder VS, Stuart EA, Anthony JC. Propensity score techniques and the assessment of measured covariate balance to test causal associations in psychological research. Psychological Methods. 2010;15(3):234–49. doi: 10.1037/a0019623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman S. Counting it up: The public costs of teen childbearing. Washington, D.C: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Marshall JM, English DJ, Knight ED, Lau AS, Dubowitz H, Kotch JB. Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: Distinction without a difference? Child Abuse and Neglect. 2005;29(5 SPEC ISS):479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Wildeman C, Jonson-Reid M, Drake B. Lifetime prevalence of investigating child maltreatment among US children. American Journal of Public Health. 2017;107(2):274–280. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl PL, Jonson-Reid M, Drake B. Time to leave substantiation behind. Child Maltreatment. 2009;14(1):17–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559508326030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BK, Lessler J, Stuart EA. Improved propensity score weighting using machine learning. Statistics in Medicine. 2009;29(3):337–346. doi: 10.1002/sim.3782.Improving. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter J, Myers KA, Zingraff MT. Substantiated and unsubstantiated cases of child maltreatment: Do their consequences differ? Social Work Research. 1994;18(2):67–82. doi: 10.2307/42659209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey DF, Griffin BA, Almirall D, Slaughter ME, Ramchand R, Burgette LF. A tutorial on propensity score estimation for multiple treatments using generalized boosted models. Statistics in Medicine. 2013;32(9):3388–3414. doi: 10.1002/sim.5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey DF, Ridgeway G, Morral AR. Propensity score estimation with boosted regression for evaluating causal effects in observational studies. Psychological Methods. 2004;9(4):403–405. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Trends & statistics. 2017 Retrieved December 2, 2017, from https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics.

- Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway G, McCaffrey D, Morral A, Burgette L, Griffin BA. Toolkit for weighting and analysis of nonequivalent groups: A tutorial for the twang package. RAND. 2013:1–30. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/twang/vignettes/twang.pdf.

- Robins JM, Hernán MÁ, Brumback B, Robins JM, Herndn MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11(5):550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55. doi: 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan DK, Curtis PA, Hunter WM, Black MM, Kotch JB, Bangdiwala S, … Landsverk J. Longscan: A consortium for longitudinal studies of maltreatment and the life course of children. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1998;3(3):275–285. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(96)00027-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schackman BR, Fleishman JA, Su AE, Berkowitz BK, Moore RD, Walensky RP, … Losina E. The lifetime medical cost savings from preventing HIV in the United States. Medical Care. 2015;53(4):1. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Petta I, McPherson K, Greene A, Li S. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS – 4): Report to Congress. Washington, D.C: 2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shenk CE, Noll JG, Peugh JL, Griffin AM, Bensman HE. Contamination in the prospective study of child maltreatment and female adolescent health. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2015 Mar;41:37–45. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv017. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart EA. Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Statistical Science. 2010;25(1):1–21. doi: 10.1214/09-STS313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Bjerregaard B, Miles W. The consequences of respondent attrition in panel studies: A simulation based on the Rochester youth development study. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1993;9(2):127–158. doi: 10.1007/BF01071165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Noll JG, Putnam FW. The impact of sexual abuse on female development: Lessons from a multigenerational, longitudinal research study. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23(2):453–76. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Bentley T, Johnson MS. A prospective investigation of physical health outcomes in abused and neglected children: New findings from a 30-year follow-up. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(6):1135–1144. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Raphael KG, DuMont KA. The case for prospective longitudinal studies in child maltreatment research: Commentary on Dube, Williamson, Thompson, Felitti, and Anda (2004) Child Abuse and Neglect. 2004;28(7):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman C, Emanuel N, Leventhal JM, Putnam-Hornstein E, Waldfogel J, Lee H. The prevalence of confirmed maltreatment among U.S. children, 2004 to 2011. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014;168(8):706–713. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]