Summary

Clouds control much of the Earth's energy and water budgets. Aerosols, suspended in the atmosphere, interact with clouds and affect their properties. Recent studies have suggested that the aerosol effect on warm convective cloud systems evolve in time and eventually approach a steady state for which the overall effects of aerosols can be considered negligible. Using numerical simulations, it was estimated that the time needed for such cloud fields to approach this state is >24 hr. These results suggest that the typical cloud field lifetime is an important parameter in determining the total aerosol effect. Here, analyzing satellite observations and reanalysis data (with the aid of numerical simulations), we show that the characteristic timescale of warm convective cloud fields is less than 12 hr. Such a timescale implies that these clouds should be regarded as transient-state phenomena and therefore can be highly susceptible to changes in aerosol properties.

Subject Areas: Earth Sciences, Atmospheric Science, Atmosphere Modelling

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

The idea that cloud fields are mostly in equilibrium state is reexamined

-

•

In the equilibrium state no significant aerosol effect is expected

-

•

The field's lifetime is shorter than the time needed for reaching equilibrium state

-

•

Therefore, clouds can be highly susceptible to changes in aerosol properties

Earth Sciences; Atmospheric Science; Atmosphere Modelling

Introduction

Clouds play a fundamental role in the Earth's water and energy budgets (Trenberth et al., 2009). Despite extensive research conducted in the past few decades, clouds are still considered one of the largest sources of uncertainty in climate and climate change research (Boucher et al., 2013, Forster et al., 2007, Schneider et al., 2017). Warm shallow convective clouds pose a particular challenge in climate research as they are responsible for the largest uncertainty in tropical cloud feedback in climate models (Bony and Dufresne, 2005), and their properties often cannot be obtained from space (Platnick et al., 2003). These clouds are frequent over oceans (Norris, 1998), and they play an important role in the lower atmosphere's energy and moisture budgets and in the global circulation (Dagan and Chemke, 2016, Nuijens et al., 2017).

It has long been acknowledged that microphysical and optical properties of warm convective clouds are regulated by the combined effect of thermodynamic and dynamic environmental conditions and atmospheric aerosols; the former determine the magnitude and vertical location of the atmospheric instability and its dynamical states (for example, in terms of wind shear and subsidence) and the latter act as cloud condensation nuclei, and hence play a major role in warm cloud formation (Pruppacher et al., 1998). Changes in aerosol properties drive changes in many of the cloud's properties, such as onset and patterns of precipitation and cloud lifetime, size (Albrecht, 1989: Altaratz et al., 2014, Koren et al., 2014, Rosenfeld et al., 2008), and radiative properties (Twomey, 1977, Mülmenstädt and Feingold, 2018). The interactions among clouds, aerosols, and environmental thermodynamics and dynamics dictate how the cloud field will evolve with time (Dagan et al., 2016).

It was shown that aerosol concentration modulates the way by which clouds affect their environment (Dagan et al., 2016); i.e., in early stages of the cloud field development, polluted clouds act to increase the thermodynamic instability with time, whereas clean clouds consume it. In turn, the evolution of the field's thermodynamic properties affects the cloud properties; hence the total aerosol effect on warm convective clouds was shown to be time dependent (Dagan et al., 2017, Lee et al., 2012, Seifert et al., 2015). This highlights the importance of the cloud field lifetime when considering the average effect of aerosols on clouds. It has been recently suggested, based on theoretical arguments (Stevens and Feingold, 2009) and numerical simulations (Lee et al., 2012, Seifert et al., 2015), that given enough time for the cloud field (i.e., the system) to evolve, aerosol effects will be buffered, meaning that the series of feedback between thermodynamic and microphysical processes that regulates the atmospheric instability and precipitation will bring the system to an equilibrium state (ES) in which the system's albedo and total rain are determined by a larger scale balance (Seifert et al., 2015). In this ES, the dependence of the system's average properties (domain average properties and not necessarily per individual cloud), such as cloud albedo and total rain, on the initial aerosol loading is shown to be small (Seifert et al., 2015).

If the ES is indeed realistic (i.e., commonly occurred in nature), it would imply low climate sensitivity to cloud-aerosol interactions and therefore, low climate sensitivity to changes in natural and anthropogenic aerosol properties (Boucher et al., 2013). Before reaching an ES, the cloud field is in a transient state in which cloud-scale processes do not have enough time for significantly affecting the thermodynamic conditions in the field. In the transient state, cloud properties strongly depend on the aerosol properties. Many observational studies (e.g., Kaufman et al., 2005, Koren et al., 2014, Yuan et al., 2011) and numerical studies simulating warm convective cloud fields (with simulation times ≤16 hr, e.g., Dagan et al., 2018, Dagan et al., 2017, Jiang et al., 2006, Jiang and Feingold, 2006, Seigel, 2014, Xue and Feingold, 2006) have shown a significant aerosol effect on cloud properties.

The fact that aerosol effect on warm convective clouds is time dependent suggests that the overall effect would likely to be an average of the effects during the cloud field evolution. Therefore, the cloud field's lifetime, i.e., the relevant time for averaging, would be a critical factor. For example, for a cloud field to reach an ES in which aerosol effects are negligible, τf, the field's lifetime (i.e., the period for which the field retains its statistical properties), must be larger than τe, the time taken to evolve to an ES (with no apparent aerosol effect). The importance of the ES could be therefore examined by comparing the two characteristic timescales. If τf ≫ τe, then the field will reach the ES early in its lifetime and therefore statistically most of the aerosol effect should be regarded as buffered. If τe ≫ τf, then the system is in a transient state throughout its lifetime and aerosol effects should be considered. We note that in the case wherein the two timescales are comparable, the system might reach an ES but for a relatively short period, and therefore the transient stage should be considered and aerosol effects should not be neglected.

Large eddy simulations (LES) are regarded as a state-of-the-art method for simulating warm cloud fields (Schneider et al., 2017). The simulations are initiated by small perturbations that deviate from the initial conditions, letting the model evolve and create the clouds with time. The domain's properties are usually neglected during the initial 2–3 hr of run time (the spin-up time) before the cloud field is well established (as the simulated cloud field starts from a cloud-free condition (Heiblum et al., 2016, Jiang et al., 2006, Jiang and Feingold, 2006, Seigel, 2014, Xue and Feingold, 2006). Recent studies (Lee et al., 2012, Seifert et al., 2015) have analyzed the interplay between microphysical and dynamic processes for different aerosol concentrations. It was estimated that the aerosol effects on the mean cloud field properties vanish after τe > 24 hr (Seifert et al., 2015) (excluding the spin-up time). Specifically, it was shown that under constant large-scale forcing and sea surface temperature (SST), after ∼28 hr, a trade cumulus cloud field reaches an organized state of "subsidence radiative-convective equilibrium" under which the aerosol effect on the domain's total rain amount, cloud fraction (CF), and radiative forcing is negligible (Seifert et al., 2015). Before reaching ES, however, the aerosol concentration significantly affects the cloud field properties, and in some cases the aerosol effect on the cloud albedo was shown to increase during the transient stage (when compared with the initial difference) before reaching the ES (see Figure 10 in Seifert et al., 2015).

Transient or ES? We address this question by estimating the characteristic timescale (τf) of warm convective cloud fields from observations and reanalysis data. Comparison of the estimated τf to values of τe as estimated in the recent LES studies (Lee et al., 2012, Seifert et al., 2015) and supported by theoretical arguments (Stevens and Feingold, 2009) will reveal the typical state of cloud fields—transient or in equilibrium (buffered).

We focus our analysis on a region over the Atlantic (Figure 1A) and constrain the study to marine convective cloud fields. The marine surface conditions are more uniform in space than those of the continents and also change slower, therefore, this analysis should give the upper limit for the estimation of τf (rapid changes in surface properties, as often expected over land, are likely to drive changes in surface fluxes and atmospheric thermodynamic conditions and therefore influence the field's statistical properties, deviating the field from its average state and reducing the estimated τf). To bound the characteristic cloud field lifetime (τf), we use the best available satellite measurements, reanalysis data, radiosonde, and cloud-resolving models.

Figure 1.

A Map of the Region of Interest

(A) Green crosses represent the evolving location of the Lagrangian region of interest corresponding to a specific case study, which follows the air trajectory as calculated by the Hysplit trajectory tool (Stein et al., 2015) starting at our reference location (black square) at 00-00-00 UTC on March 1, 2008.

(B and C) (B) Local (Eulerian) and (C) Lagrangian vertical velocity [Pa/s] as a function of time and pressure level. The black box region of interest was used for the Eulerian diagnostics throughout the study.

(D–M) Time series of MSG-SEVIRI cloud top height (m) over the Atlantic Ocean. (D–H) The time series of cloud top height for the Eulerian diagnostics; (I–M) the same for the Lagrangian diagnostics. The time between two consecutive snapshots is 12 hr. Fields of trade cumulus clouds are characterized by low cloud coverage and low-level cloud tops (blue regions). A time series of MSG data with higher temporal resolution is presented in Figures S2 and S5.

Specifically, we use detailed cloud properties retrieved from MODIS (Level 3 1˚ × 1˚ data) measurements onboard the polar orbiting Terra and Aqua satellites (Platnick et al., 2003), cloud field properties measured by the SEVIRI instrument onboard the Meteosat Second Generation (MSG) geostationary satellite (Aminou, 2002), measurements of key thermodynamic properties from radiosondes, and reanalysis data of the environmental thermodynamic conditions from the ECMWF (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts) (Dee et al., 2011). Each of these independent datasets has advantages and limitations. For fields of relatively small clouds, satellite measurements can provide a relatively robust estimate of the CF and the cloud top temperature (CTT) (or its translation to cloud top height). Radiosonde measurements of atmospheric profiles of temperature and humidity are considered reliable data for cloud physics research; however, long records of radiosonde data are restricted to continents and are limited in their spatial representation. Reanalysis data do provide a suite of all of the important thermodynamic variables in the atmosphere. However, using models to smooth and interpolate the atmospheric variable values between measurements adds unavoidable inaccuracies to the calculated values (Dee et al., 2011).

Cloud properties are controlled by numerous atmospheric variables that dictate (among other properties) the instability level, availability of water vapor, wind, and turbulence along the atmospheric profiles. Most of the atmospheric variables are linked through dynamic, thermodynamic, microphysical, and radiative processes and are therefore not independent.

Results

To set the stage for our set of analyses, we merge satellite and reanalysis data in a case study manner in which we characterize the time-varying cloud properties and environmental conditions associated with an air mass that starts within a specific warm convective cloud field (Figure 1). The analysis is performed using two frameworks that provide complementary information on the cloud field and the environmental conditions associated with it: a Lagrangian framework that tracks the air mass as it is advected by the atmospheric circulation and a Eulerian framework that is fixed in space (Eastman et al., 2016).

Lagrangian diagnostics of the air mass that starts within a warm cloud field (observed on March 1, 2008, see Figure 1) reveals that the advection leads to dramatic changes in the environmental forcing that is acting on the air mass (expressed by changes in SST, subsidence, and surface fluxes; Bretherton et al., 1995, Eastman et al., 2016, Pincus et al., 1997, Sandu et al., 2010; see Figures 1C, S1, and S2). Furthermore, the Lagrangian diagnostics (Figure 1, lower panel line) shows that after a period of ∼1.5 days, the air mass that was initially associated with a field of warm convective clouds is located within a region that is distinctly associated with deep convective clouds (Figure 1L), which differ significantly in their characteristics. Similarly, the same time period (1.5 days) was shown, by Lagrangian analysis, to be sufficient for the marine boundary layer to evolve from stratocumulus layer to cumulus layer (Bretherton and Pincus, 1995).

The Eulerian approach also shows a significant change in time over a specific location, as air masses with different histories enter the region (Mauger and Norris, 2010) (Figures 1, S3, and S4), and the local meteorological conditions change with time (Figures 1B and S5).

Previous studies also reported on a short-lived and high variable trade cumulus clouds with a variety of organizational levels existing at the same time (Rauber et al., 2007). For example, in Nuijens et al., (2014) it was noted that:

Although the cloud field consists predominantly of shallow trade-wind cumuli, it has a rich character, reflecting variability in largescale meteorology, local heterogeneity and the degree of cloud organization. Within a couple of hours, fields of cumuli can look remarkably different, in terms of how numerous, deep and large they are, whether they are raining, and whether they are accompanied by a second stratiform-like mode of cloud.

Moving from an individual case study (Figure 1) to the statistics of many cases, we focus first on direct satellite measurements of cloud properties. The spatial and temporal autocorrelations of cloud properties were analyzed using the MODIS cloud data (Figures 2A and 2B) and MSG-SEVIRI geostationary data (which have higher temporal and lower spatial resolution—Figure 2C). We focus on cloud properties for which retrieval is simple and does not rely on plane-parallel assumptions (Platnick et al., 2003), namely, the CF and the average CTT (the decorrelation of the cloud optical thickness and cloud water path are presented in Figure S6). For the next set of analyses, we extend the used frameworks to include a spatial one (in addition to the Lagrangian and Eulerian ones), all at 1° resolution. In all frameworks, we estimate how fast (or within what distance) the field properties change. In the Eulerian framework, we compute how the autocorrelations change with time for a few selected reference points. The autocorrelation is calculated at each of the reference points for the selected cloud property over a 3-month (March–May 2008) period. During this period, our region of interest is less loaded with Saharan dust (i.e., Ben-Ami et al., 2012). The properties of the transported dust and its changes in time might affect the quality of the remote-sensing retrievals as well as the cloud fields' properties and hence would add another layer of complexity (to the analysis that estimates τf) that we want to avoid. In the spatial analysis, we compute the correlations between the 3-month time series of the selected cloud properties of each of the selected reference points with all of the other grid points over the northern tropical Atlantic (0–30°N 20–70°W). Then we calculate the average correlation per points with equal distance from the reference point (Figure 2A). A map of such a correlation is shown in Figure S7. The Lagrangian analysis was based on correlations along more than 12,500 trajectories calculated using the ECMWF dataset, starting from a box over the same area (15–25°N 25–35°W—see details in the Transparent Methods).

Figure 2.

Autocorrelation of Cloud Field Properties as Measured by MODIS-Aqua

(A) Spatial correlation of the cloud field properties as measured by MODIS-Aqua. The correlations are calculated compared to a single point at 20°N 30°W over three months (March–May 2008). Terra data show the same results (see Figure S7). The correlations of the mean values and standard deviations (SDs) of the CF and CTT are presented.

(B) Temporal correlation based on combined data of Terra and Aqua.

(C) Spatial correlation of CTT measured by MSG-SEVIRI for 60 hr at the beginning of March 2008. Red horizontal lines represent the e−1 threshold.

All the correlation calculations are performed for a few reference points over the mid subtropical Atlantic. The correlation curves do not show sensitivity to the location of the reference point. Here, as an example, we show the results for 20°N 30°W (Figure 2).

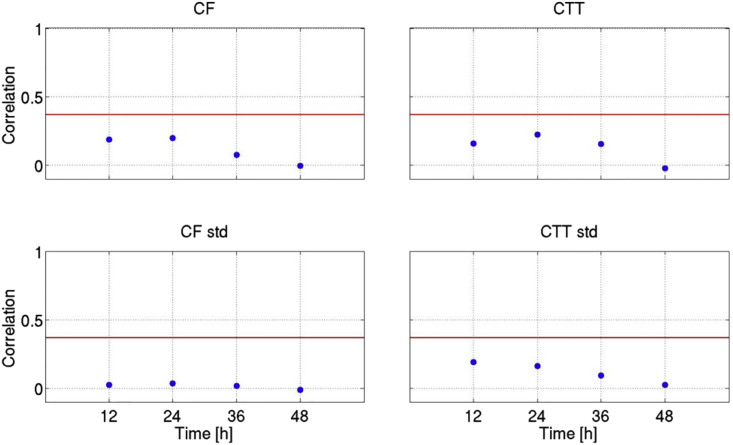

Figure 2A shows the spatial autocorrelation of the mean and variance of the cloud properties as measured by the MODIS instrument, demonstrating decay after a distance of 2° (≈200 km, the e-fold is used as a decorrelation threshold; Eastman et al., 2016). Moreover, the decay of the temporal autocorrelation (Figure 2B), based on combining data from Terra and Aqua is shown to be bounded between 3 and 9 hr, which are the available temporal differences between the MODIS measurements on the Terra and Aqua platforms (see details in the Transparent Methods). The mean correlation along many trajectories (Figure 3) decays significantly in less than 12 hr.

Figure 3.

Mean Lagrangian Autocorrelation of the Cloud Field Properties along Trajectories as Measured by MODIS

Red horizontal lines represent the e−1 threshold. Aqua data was used. Terra data show the same results (Figure S7).

When analyzing data from the geostationary satellite (measured every 15 min by the SEVIRI instrument; Aminou, 2002), the correlation of the cloud properties decays even faster, on a spatial scale of ∼1° (Figure 2C). The mean near-surface (1,000–900 hPa) wind speed over the examined location and time (7.0 ± 3.2 m/s) from the reanalysis dataset can be used to translate the spatial results to temporal ones. If one considers the upper bound of the spatial decorrelation length to be ∼2°, the τf is scaled to be bound by ∼8 hr, after which the cloud field will be advected, and will evolve into having significantly different properties (consistent with the Lagrangian analysis in Figure 3).

We note that Figure 2 suggests that some memory is present in the cloud properties (Eastman et al., 2016). Even if the decorrelation does not follow a perfect exponential decay, a decrease of the decorrelation to below e−1 represents a significant change in the observed property and hence can be used to constrain the cloud field lifetime.

In addition to the satellite results presented above, analysis of a 3-month dataset of radiosonde measurements from Puerto Rico (March–May 2008, Figure 4) also indicates that the convective cloud-related environmental conditions (convective available potential energy, level of free convection pressure, and equilibrium level pressure—see details in the Transparent Methods) decay significantly faster than 12 hr (which is the temporal resolution available for this type of data). We note that the decay of the auto-correlation as seen in Figures 2, 3, and 4 is monotonic, suggesting a continuous change rather than fluctuations around some reference state.

Figure 4.

Autocorrelation of Time Series

Autocorrelation of (A) convective available potential energy (CAPE), (B) level of free convection (LFC) pressure and (C) equilibrium level (EL) pressure calculated based on radiosonde data measured at the San Juan Puerto Rico station (18.4°N 66.0°W) in March–May 2008. The interval between sequential data points is 12 hr. Red horizontal lines represent the e−1 threshold.

To study the temporal variation of the thermodynamic factors that control cloud fields, we use the reanalysis database to estimate their rate of change (for a full calculation of their autocorrelation decay time and distance, see Autocorrelation of Meteorological Parameters Relevant for Shallow Clouds, Supplemental Information, Figures S8 and S9). From theoretical considerations, we chose to focus on two thermodynamic variables—temperature (T) and humidity (relative humidity [RH] or water-vapor mixing ratio [Qv]) (Houze, 1994), and on a dynamic variable—the air vertical velocity (Ω, pressure velocity) (Myers and Norris, 2013), all in the lower atmosphere. The measured changes in these selected variables (as estimated based on the reanalysis data) are plugged into cloud resolving numerical simulations to estimate the expected influence on clouds and cloud field properties.

We note that other environmental variables also have an impact on the clouds' properties, and that they may change differently with time. However, our numerical simulation results demonstrate that a change in each one of our selected variables alone (fixing all others) results in significant differences in the cloud's properties.

Figure 5 presents the mean magnitude of the changes in the selected environmental variables as a function of time for the lower atmosphere (mean value for seven levels between 700 and 1,000 hPa). We note that all the selected variables exhibit an increase in the mean differences with time (compared with a reference initial state) until saturation is reached. The temperature (Figure 5A) and humidity (RH and Qv, Figures 5B and 5C) reach saturation levels (∼2°C, ∼18%, and 1.6 g/kg, respectively) more slowly than the pressure velocity, which reaches saturation within one time step (of 6 hr). Within the first time step, the mean change in RH is 5.1% and the mean change in T is 0.57°C. How sensitive are clouds to such rapid changes in the selected variables?

Figure 5.

An Example of 3 Months' (March–May 2008) Mean Changes with Time of the Selected Thermodynamic Variables at Our Reference Point (20°N 30°W)

(A) temperature (T), (B) water-vapor mixing ratio (Qv), (C) relative humidity (RH), and (D) pressure velocity (Ω) for the lower atmosphere (mean over seven levels between 700 and 1,000 hPa).

(E) Vertical structure of the mean temperature change over 6 hr.

Using a single cloud model (Reisin et al., 1996, Tzivion et al., 1994) (see details in the Transparent Methods, Figure S10), we run three simulations of a warm convective cloud: (1) a reference simulation, (2) a simulation with drier initial profile based on the mean changes in RH during 6 hr (5.1% for all heights, maintaining the temperature profile fixed), and (3) a simulation with changes in the temperature profile (by a magnitude similar to that observed by the reanalysis data, including the vertical structure of the change; Figure 5E) maintaining a fixed Qv profile.

Figure 6 presents the temporal evolution of the total water mass and maximum vertical velocity in the cloud as a function of time for the three simulations. It demonstrates that changes in both T and RH at magnitudes similar to those observed during 6 hr can dramatically influence the cloud's properties. Decreasing the RH by the estimated magnitude of this one time step (6 hr) suppresses cloud development, whereas changes in T drive a reduction in the cloud's maximum total mass during the simulation to ∼1/3 of the reference simulation's value (the mean temperature change during 12 hr completely suppresses cloud development—not shown).

Figure 6.

Total Liquid Water Mass in the Domain (Total Mass, Upper Panel) and Maximum Vertical Velocity (Wmax, Lower Panel) as a Function of Time for the Three Simulations Conducted with the Single Cloud Model

Black lines represent the control simulation, whereas the blue and green lines represent the simulations with changes in the temperature (T) or humidity (RH) profile, respectively.

The possible effect of the observed changes in Ω on the clouds' properties is examined using the LES model (Khairoutdinov and Randall, 2003) (see details in the Transparent Methods). The prescribed Ω according to the large-scale forcing in the BOMEX case study, which describes a trade cumulus cloud field in the area of Barbados (Holland and Rasmusson, 1973, Siebesma et al., 2003), falls well within the range of observed Ω (Figure S11) in the region of interest over the Atlantic Ocean. Three LES are conducted: (1) a reference simulation with the standard BOMEX setup, (2) a simulation with double the prescribed subsidence (0.065 Pa/s above the inversion base height at 1,500 m), and (3) one with no subsidence (Ω = 0). As inferred from the averaged change analysis, such magnitudes of changes in Ω are frequently shown in the reanalysis dataset between each 6-hr time step (for which the mean magnitude of change is 0.044 Pa/s—Figures 5D and S11). The evolution of the domain-average properties of the LES runs (Figure 7) shows that when the subsidence is decreased from two times the prescribed BOMEX value to 0, the total water mass, and the mean liquid water path increase by an order of magnitude. In addition, the maximum vertical velocity (Wmax), the CF, and the COG (center of gravity—the domain vertical location of the liquid water mass COG; Koren et al., 2009) approximately double their values. A significant amount of rain is observed for the case of no Ω, whereas no rain is produced in the simulation with double the subsidence (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Properties of the Simulated Cloud Fields (as a Function of Time) for Three Different Simulations Differ by the Prescribed Large-Scale Vertical Velocity (Ω) Used in the Simulation

(A–F) (A) Total liquid water mass in the domain (Total mass), (B) mean (over domain) cloudy liquid water path (LWP calculated only over the cloudy columns), (C) maximum vertical velocity (Wmax), (D) mean surface rain rate, (E) mean liquid water center of gravity (COG), and, (F) cloud fraction (CF).

Discussion

In previous theoretical simulations in which the large-scale conditions were held constant, the internal adaptation toward an ES was shown to be linked to the clouds' effects on the environmental conditions (Lee et al., 2012, Seifert et al., 2015). Clean clouds that produce rain rapidly reach an ES, whereas polluted clouds have to go through significant deepening of the boundary layer before precipitation starts and then reach the ES (Seifert et al., 2015). Theoretically, if the environmental conditions would change at the same rate or slower than the field adapts toward the ES, then the system could reach the ES and stay near it. In this case, the observed cloud field properties would be expected to change approximately at the rate of the timescale of the environmental changes. However, our results show that the changes in the cloud field properties and in the environmental conditions are not marginal (in either rate or magnitude). Satellite measurements of CF and CTT are shown here to change significantly and relatively rapidly (faster than the time taken to reach the ES). The correlation decreases below e-fold, for both the average and the standard deviation, within a timescale of <12 hr or 1–2°. In a similar manner, the marine boundary layer's temperature, humidity, a measure of the lower troposphere subsidence, and a measure of the collective environmental conditions' state (based on a PCA analysis; see Autocorrelation of Meteorological Parameters Relevant for Shallow Clouds, Supplemental Information) all from reanalysis data, are shown to change considerably during this time frame so that the expected clouds and cloud fields will have significantly different properties. Analysis of radiosonde measurements over Puerto Rico also indicates that the autocorrelation of the convective-clouds-related environmental conditions reaches an e-fold decay at a faster rate than 12 hr.

All the presented results bound the characteristic timescale of warm convective cloud fields (τf) to an upper limit of ∼12 hr (as cited above, for example, Nuijens et al., (2014) noted that within a “couple of hours” the fields can “look remarkably different”). The fact that such an upper bound applies to all of the different datasets that are analyzed (using different approaches) increases the level of confidence in our τf estimation. This estimated timescale suggests that marine warm convective cloud fields are likely to be in a transient state and not in an ES. Hence, they are likely to be susceptible to changes in natural or anthropogenic aerosol properties and aerosol effects on cloud albedo and precipitation should be considered in global and regional climate models. Moreover, such a time frame should restrict the simulation time in numerical experiments that are aimed at evaluating aerosol effects on warm convective clouds and the derived climate effect.

It is possible that under some conditions a specific cloud field will exist long enough to reach an ES (i.e., τf > τe). However, here we show that in a statistical perspective this is not the case. Our results suggest that 2τf ∼ = τe, which implies that the transient stage is the dominant one. We note that even if considering doubling of the fields' lifetime such that τf ∼ τe, still most of the time the fields will be in a transient stage. We speculate that this will be the case for other types of convective clouds, but this needs to be examined in future work.

From a completely different perspective, such an approximation for τf can be supported by considering the link between the length scale of warm convective cloud fields and their lifetime. Such a link has been suggested to characterize any atmospheric dynamical entity (Cullen, 2007, Smagorinsky, 1974). The characteristic length scale of warm trade cumulus cloud fields is estimated to be around ∼100–200 km (Figure 2A). Accordingly, an atmospheric entity of 200 km indeed scales to a temporal range of 1–10 hr.

Limitations of Study

We note that a clear definition of a cloud field lifetime is challenging and depends on the available data. One can define cloud field by its collective cloud properties or by the thermodynamic conditions that allow the field to exist. No option is perfect. The cloud measurements are often limited, and the environmental properties are indirect. In this article, we explore both approaches. Driven by similar reasons the estimation of τe, is challenging as well. There is no clear general theory for estimating this measure. Here we based τe estimates on numerical studies that each of them had to use a specific set of environmental conditions. Therefore, in essence it does not span all possibilities of trade cumulus cloud fields. Despite this limitation we show that in several studies (that used few environmental conditions) the simulations did not reach an ES while running less than 16 hr, which further provides lower limit to τe. This study sets the stage for the comparison of the two characteristic time scales to estimate if warm convective cloud fields are transient in nature.

Moreover, in our analysis, we do not consider changes in aerosol properties in time (due to washout, large-scale advection, local sources, etc.). For a given cloud field (with a given initial aerosol concentration), considering this additional change in aerosol properties is likely to further restrict the field's lifetime (τf) as it can change the clouds microphysical and dynamic properties. Hence, considering a fixed aerosol loading conditions (as was done here and in Seifert et al., 2015) serves the purpose of estimating the upper bound of τf. The usage of marine surface conditions serves the same purpose as they are more uniform in space and change slower compared with those of land. In a similar manner, the diurnal cycle could act as another driver for shortening the field lifetime as it imposes changes in the thermodynamic conditions that control the cloud fields' properties (Matsui et al., 2006).

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by Scott Eric Jordan and Gina Valdez, the Bernard and Norton Wolf Family Foundation, and the Minerva Foundation (grant 712287). The authors gratefully acknowledge the NOAA Air Resources Laboratory (ARL) for the provision of the HYSPLIT transport and dispersion model and/or READY website (http://www.ready.noaa.gov) used in this publication. We thank the University of Wyoming, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, for the sounding data (downloaded from http://weather.uwyo.edu/upperair/sounding.html).

Author Contributions

G.D. carried out the analysis. G.D., I.K., O.A., and Y.L. conceived the basic ideas, discussed the results and wrote the paper.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: December 21, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Transparent Methods and 11 figures and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2018.11.032.

Supplemental Information

References

- Albrecht B.A. Aerosols, cloud microphysics, and fractional cloudiness. Science. 1989;245:1227–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.245.4923.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altaratz O., Koren I., Remer L., Hirsch E. Review: cloud invigoration by aerosols—coupling between microphysics and dynamics. Atmos. Res. 2014;140:38–60. [Google Scholar]

- Aminou, D.M. (2002). MSG's SEVIRI instrument. ESA Bulletin(0376–4265), 15-17.

- Ben-Ami Y., Koren I., Altaratz O., Kostinski A., Lehahn Y. Discernible rhythm in the spatio/temporal distributions of transatlantic dust. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012;12:2253–2262. [Google Scholar]

- Bony S., Dufresne J.L. Marine boundary layer clouds at the heart of tropical cloud feedback uncertainties in climate models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005;32 [Google Scholar]

- Boucher O., Randall D., Artaxo P., Bretherton C., Feingold G., Forster P., Kerminen V., Kondo Y., Liao H., Lohmann U. Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press; 2013. Clouds and aerosols; pp. 571–657. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton C.S., Austin P., Siems S.T. Cloudiness and marine boundary layer dynamics in the ASTEX Lagrangian experiments. Part II: cloudiness, drizzle, surface fluxes, and entrainment. J. Atmos. Sci. 1995;52:2724–2735. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton C.S., Pincus R. Cloudiness and marine boundary layer dynamics in the ASTEX Lagrangian experiments. Part I: synoptic setting and vertical structure. J. Atmos. Sci. 1995;52:2707–2723. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen M. Modelling atmospheric flows. Acta Numerica. 2007;16:67–154. [Google Scholar]

- Dagan G., Chemke R. The effect of subtropical aerosol loading on equatorial precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016;43 [Google Scholar]

- Dagan G., Koren I., Altaratz O., Heiblum R.H. Aerosol effect on the evolution of the thermodynamic properties of warm convective cloud fields. Scientific Rep. 2016;6:38769. doi: 10.1038/srep38769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagan G., Koren I., Altaratz O., Heiblum R.H. Time-dependent, non-monotonic response of warm convective cloud fields to changes in aerosol loading. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017;17:7435–7444. [Google Scholar]

- Dagan G., Koren I., Altaratz O. Quantifying the effect of aerosol on vertical velocity and effective terminal velocity in warm convective clouds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018;18(9):6761–6769. [Google Scholar]

- Dee D., Uppala S., Simmons A., Berrisford P., Poli P., Kobayashi S., Andrae U., Balmaseda M., Balsamo G., Bauer P. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: Configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2011;137:553–597. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman R., Wood R., Bretherton C.S. Timescales of clouds and cloud controlling variables in subtropical stratocumulus from a Lagrangian perspective. J. Atmos. Sci. 2016;73:3079–3091. [Google Scholar]

- Forster P., Ramaswamy V., Artaxo P., Berntsen T., Betts R., Fahey D.W., Haywood J., Lean J., Lowe D.C., Myhre G., editors. Changes in Atmospheric Constituents and in Radiative Forcing Chapter 2. Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 131–234. [Google Scholar]

- Heiblum R.H., Altaratz O., Koren I., Feingold G., Kostinski A.B., Khain A.P., Ovchinnikov M., Fredj E., Dagan G., Pinto L. Characterization of cumulus cloud fields using trajectories in the center-of-gravity vs. water mass phase space. Part II: aerosol effects on warm convective clouds. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2016;121:6356–6373. [Google Scholar]

- Holland J.Z., Rasmusson E.M. Measurements of the atmospheric mass, energy, and momentum budgets over a 500-kilometer square of tropical ocean. Monthly Weather Rev. 1973;101:44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Houze Jr., R.A. (1994). Cloud dynamics, Vol. 104 (Academic press). New Ser., vol. 4b, edited by G. Fischer, pp. 391–457, Springer, Berlin.

- Jiang H., Xue H., Teller A., Feingold G., Levin Z. Aerosol effects on the lifetime of shallow cumulus. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006;33 [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H.L., Feingold G. Effect of aerosol on warm convective clouds: aerosol-cloud-surface flux feedbacks in a new coupled large eddy model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2006;111 [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman Y.J., Koren I., Remer L.A., Rosenfeld D., Rudich Y. The effect of smoke, dust, and pollution aerosol on shallow cloud development over the Atlantic Ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2005;102:11207–11212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505191102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairoutdinov M.F., Randall D.A. Cloud resolving modeling of the ARM summer 1997 IOP: model formulation, results, uncertainties, and sensitivities. J. Atmos. Sci. 2003;60:607–625. [Google Scholar]

- Koren I., Altaratz O., Feingold G., Levin Z., Reisin T. Cloud's Center of Gravity - a compact approach to analyze convective cloud development. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009;9:155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Koren I., Dagan G., Altaratz O. From aerosol-limited to invigoration of warm convective clouds. Science. 2014;344:1143–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.1252595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.-S., Feingold G., Chuang P.Y. Effect of aerosol on cloud–environment interactions in trade cumulus. J. Atmos. Sci. 2012;69:3607–3632. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T., Masunaga H., Kreidenweis S.M., Pielke R.A., Tao W.K., Chin M., Kaufman Y.J. Satellite-based assessment of marine low cloud variability associated with aerosol, atmospheric stability, and the diurnal cycle. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2006;111 [Google Scholar]

- Mauger G.S., Norris J.R. Assessing the impact of meteorological history on subtropical cloud fraction. J. Clim. 2010;23:2926–2940. [Google Scholar]

- Mülmenstädt J., Feingold G. The radiative forcing of aerosol–cloud interactions in liquid clouds: wrestling and embracing uncertainty, Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2018;4(1):23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Myers T.A., Norris J.R. Observational evidence that enhanced subsidence reduces subtropical marine boundary layer cloudiness. J. Clim. 2013;26:7507–7524. [Google Scholar]

- Norris J.R. Low cloud type over the ocean from surface observations. Part II: Geographical and seasonal variations. J. Clim. 1998;11:383–403. [Google Scholar]

- Nuijens L., Emanuel K., Masunaga H., L’Ecuyer T. Implications of warm rain in shallow cumulus and congestus clouds for large-scale circulations. Surv. Geophys. 2017;38:1257–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Nuijens L., Serikov I., Hirsch L., Lonitz K., Stevens B. The distribution and variability of low-level cloud in the North Atlantic trades. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2014;140:2364–2374. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus R., Baker M.B., Bretherton C.S. What controls stratocumulus radiative properties? Lagrangian observations of cloud evolution. J. Atmos. Sci. 1997;54:2215–2236. [Google Scholar]

- Platnick S., King M.D., Ackerman S.A., Menzel W.P., Baum B.A., Riedi J.C., Frey R.A. The MODIS cloud products: algorithms and examples from Terra. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2003;41:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Pruppacher H.R., Klett J.D., Wang P.K. Science & Business Media; Springer: 2012. Microphysics of Clouds and Precipitation. [Google Scholar]

- Rauber R.M., Stevens B., Ochs H.T., III, Knight C., Albrecht B.A., Blyth A.M., Vali G. Rain in shallow cumulus over the ocean: the RICO campaign. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2007;88(12):1912–1928. [Google Scholar]

- Reisin T., Levin Z., Tzivion S. Rain production in convective clouds as simulated in an axisymmetric model with detailed microphysics. part I: description of the model. J. Atmos. Sci. 1996;53:497–519. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld D., Lohmann U., Raga G.B., O'Dowd C.D., Kulmala M., Fuzzi S., Reissell A., Andreae M.O. Flood or drought: how do aerosols affect precipitation? Science. 2008;321:1309–1313. doi: 10.1126/science.1160606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandu I., Stevens B., Pincus R. On the transitions in marine boundary layer cloudiness. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010;10:2377–2391. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T., Teixeira J., Bretherton C.S., Brient F., Pressel K.G., Schär C., Siebesma A.P. Climate goals and computing the future of clouds. Nat. Clim. Change. 2017;7:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert A., Heus T., Pincus R., Stevens B. Large-eddy simulation of the transient and near-equilibrium behavior of precipitating shallow convection. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2015;7:1918–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Seigel R.B. Shallow cumulus mixing and subcloud layer responses to variations in aerosol loading. J. Atmos. Sci. 2014;71:2581–2603. [Google Scholar]

- Siebesma A.P., Bretherton C.S., Brown A., Chlond A., Cuxart J., Duynkerke P.G., Jiang H., Khairoutdinov M., Lewellen D., Moeng C.-H. A large eddy simulation intercomparison study of shallow cumulus convection. J. Atmos. Sci. 2003;60:1201–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Smagorinsky J. Global atmospheric modeling and the numerical simulation of climate. Weather Clim. Modif. 1974:633–686. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens B., Feingold G. Untangling aerosol effects on clouds and precipitation in a buffered system. Nature. 2009;461:607–613. doi: 10.1038/nature08281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein A.F., Draxler R.R., Rolph G.D., Stunder B.J.B., Cohen M.D., Ngan F. NOAA’s HYSPLIT atmospheric transport and dispersion modeling system. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2015;96:2059–2077. [Google Scholar]

- Trenberth K.E., Fasullo J.T., Kiehl J. Earth’s global energy budget. Bull Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2009;90:311–323. [Google Scholar]

- Twomey S. The influence of pollution on the shortwave albedo of clouds. J. Atmos. Sci. 1977;34:1149–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Tzivion S., Reisin T., Levin Z. Numerical simulation of hygroscopic seeding in a convective cloud. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1994;33:252–267. [Google Scholar]

- Xue H.W., Feingold G. Large-eddy simulations of trade wind cumuli: Investigation of aerosol indirect effects. J. Atmos. Sci. 2006;63:1605–1622. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan T., Remer L.A., Yu H. Microphysical, macrophysical and radiative signatures of volcanic aerosols in trade wind cumulus observed by the A-Train. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011;11:7119–7132. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.